Timing of physical activity and cardiovascular and mortality risk in patients with type 2 diabetes: a UK biobank cohort study

Abstract

Aim: The study aims to explore the relationship between objectively measured physical

Methods: Data were obtained from the UK Biobank, a population-based prospective cohort study. From February 2013 to December 2015, the PA of the participants was objectively measured by continuously wearing an accelerometer for 7 days. CVD was defined through the International Classification of Diseases (10th Revision) codes by linking to national hospitalization data. Death data was obtained through the National Health Service Information Center. K-means cluster analysis was used to cluster patients with similar temporal activity patterns.

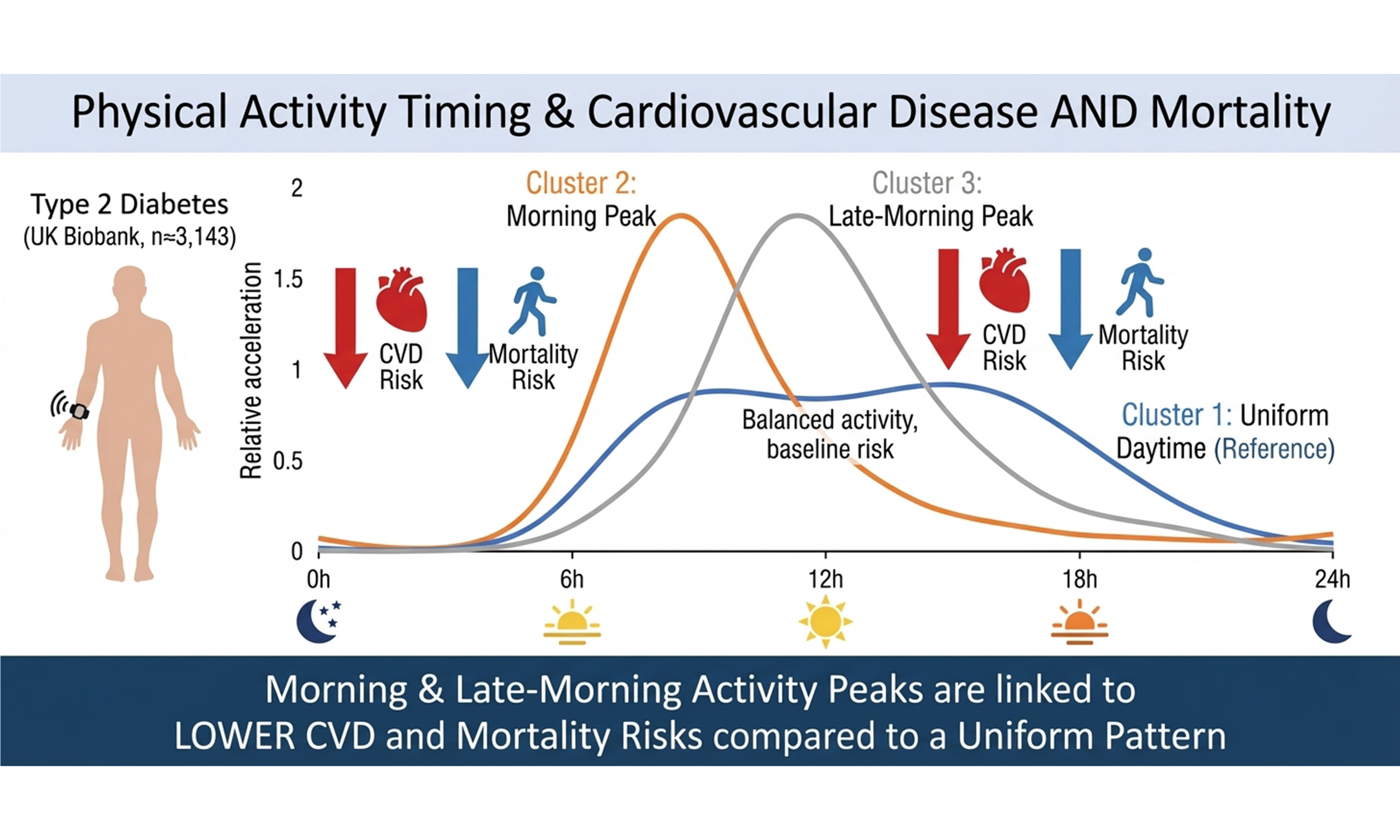

Results: Among 3,143 adults with T2DM (mean age 65.9 years; 62.0% men), followed for a median of 7.82 years, 13.91% developed CVD, 13.53% died from cardiovascular causes, and 9.61% died from any cause. A Cox proportional hazards regression model showed that higher hourly PA was associated with lower CVD and cardiovascular mortality risk, particularly for activity accumulated between 8 am and 4 pm. Lower ACM risk was observed for activity performed throughout the day and evening, whereas elevated early-morning activity, most notably around 3 am, was linked to higher CVD and mortality risk. Cluster analysis identified three PAtiming profiles. Compared with participants exhibiting evenly distributed daytime activity (Cluster 1), those with morning activity peaks at 8-9 am (Cluster 2) or 11-12 am (Cluster 3) had substantially reduced CVD incidence {hazard ratio (HR) 0.449 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.318-0.634] and 0.493 (95%CI: 0.363-0.670), respectively}. The ACM risk was similarly lower in clusters 2 [HR 0.625 (95%CI: 0.448-0.873)] and 3 [HR 0.548 (95%CI: 0.403-0.746)]. These associations were independent of overall PA intensity.

Conclusion: Engaging in PA in the late morning or at noon is associated with a lower risk of CVD and ACM in patients with T2DM. Time-dependent PA interventions may constitute an additional benefit for managing cardiovascular and mortality risks in these patients.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is one of the most serious and common chronic diseases of our time, affecting about 1 in 10 adults worldwide and causing significant health and economic burdens[1]. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in patients with T2DM[2]. Relative to patients without T2DM, the risk of CVD in patients with T2DM is two to four times higher, and the risk of all-cause mortality (ACM) and cardiovascular mortality is 50% to 60% higher[3]. Adequate physical activity (PA), an important part of diabetes management, can reduce the risk of ACM, CVD, and cardiovascular mortality in patients with T2DM[4-6]. The American Diabetes Association guidelines recommend that patients with T2DM engage in at least 150 min of moderate- to high-intensity aerobic exercise spread over at least 3 days a week and do not remain inactive for more than 2 consecutive days[7].

Previous studies have mostly focused on the frequency, intensity, and duration of PA using self-reported PA measurements, which may not accurately reflect the population’s activity level[8]. Recent studies have suggested that the timing of PA during the day is related to cardiometabolic health[9,10]. A cross-sectional study showed that patients with T2DM who engaged in more moderate- to high-intensity PA at noon had the poorest cardiopulmonary health, while men who were most active in the morning had the best cardiopulmonary health, independently of the intensity and duration of PA[10]. Studies in experimental animals also suggest that the time of day for PA is a key factor affecting exercise capacity, skeletal-muscle metabolic pathways, and systemic energy homeostasis, indicating that the beneficial effects of PA may be mediated by endogenous circadian rhythms[11,12]. Several interventional studies have found that the timing of exercise can affect blood sugar control and cardiovascular function[13-15]. However, these studies included fewer than 12 patients, all of whom engaged in group exercise rather than independent PA. In addition, the health benefits of PA may originate from any form of activity during the day (e.g., work, commuting, housework).

While the relationship between the timing of PA and the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause death in the general population has been addressed in previous studies[16], research is lacking in patients with T2DM. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the prospective relationship between the distribution of independent PA during the day and cardiovascular and mortality outcomes in these patients. We used the UK Biobank, a large population-based, nationally representative prospective cohort study, to explore the relationship between objectively measured PA timing and the incidence of CVD, cardiovascular-specific mortality, and ACM in T2DM patients.

METHODS

Data source and study population

The study data was obtained from the UK Biobank, an ongoing population-based prospective cohort study. More than 500,000 participants aged between 37 and 73 years were recruited from March 2006 to October 2010. All participants underwent baseline assessment at 1 of 22 assessment centers in England, Wales, and Scotland, completing touch-screen questionnaires and providing physical measurements and blood and urine samples. The UK Biobank was approved by the North-West Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee (application number 92014). Each participant provided written informed consent.

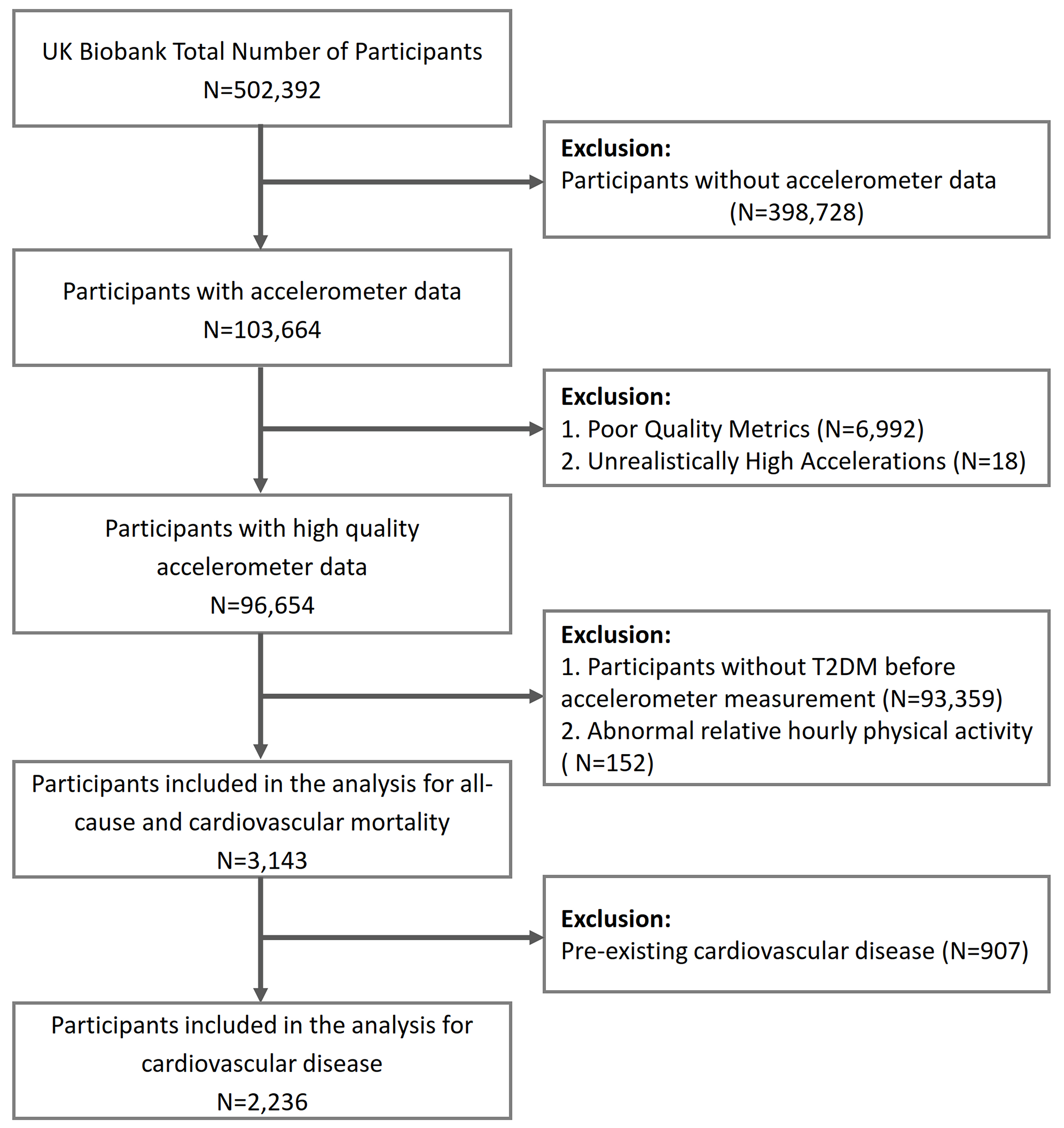

A total of 502,392 patients participated in the baseline survey, of whom 103,664 wore accelerometers. Those who wore the devices for fewer than 3 days (N = 6,992) or had abnormally high PA values [daily mean acceleration, ≥ 100 milligravity (mg) units; N = 18] were excluded. The T2DM diagnosis was either self-reported or identified in medical records through the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code E11. Participants without T2DM (N = 93,359) were excluded from the baseline survey, and 152 people were excluded during cluster analysis for abnormal average hourly relative acceleration [5 standard deviations (SD) above or below the average], leaving 3,143 patients for analysis. In addition, when analyzing the relationship between PA timing and CVD, 907 patients with CVD at baseline were excluded [Figure 1]. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) cohort study report guidelines[17].

Assessment of PA

To objectively measure independent PA, some baseline participants were invited via email to continuously wear accelerometers for PA measurement from February 2013 to December 2015. Those who agreed to participate were sent the Axivity AX3 wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer (Axivity Ltd., Newcastle, UK), which recorded data continuously for 7 days starting at 10:00 a.m. Raw triaxial acceleration data (100 Hz) were processed using the R package “accelerometry” and the UK Biobank expert working group protocol. Non-wear time was identified as periods of consecutive stillness (standard deviation across x, y, z < 13.0 mg) lasting ≥ 60 min[18]. These segments were imputed using the mean vector magnitude of similar time-of-day epochs on other valid days to correct for potential diurnal bias. Participants were required to have at least

Assessment of outcomes

The main outcome indicators were the incidence of CVD, cardiovascular death, and all-cause death. CVD was defined by ICD-10 codes by linking to national hospitalization data up to October 31, 2021, including codes for ischemic heart disease (codes I20 to 25), cardiac arrest (I46), heart failure (I50), and stroke (I60 to I64). Death data was obtained through the National Health Service (NHS) Information Center (England and Wales) or the NHS Central Register and National Records (Scotland) up to November 30, 2021.

Covariates

Patient baseline demographic characteristics and lifestyle habits (e.g., age, sex, race, qualification, family income, smoking, drinking, and sleep chronotype) were investigated using touch-screen questionnaires. Sleep chronotypes were categorized as early sleeper (definitely a “morning” person/more a “morning” than “evening” person) and late sleeper (definitely an “evening” person/more an “evening” than “morning” person) via one question: “Do you consider yourself to be… ?” Patient height and weight were measured using standard methods, and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated. According to World Health Organization standards, BMI has three categories: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), healthy (18.5-25 kg/m2), and overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) or obesity (≥ 30 kg/m2). Glycated hemoglobin levels were determined in baseline blood samples.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described using mean ± SD, and categorical variables using frequency (percentage). Group comparisons were made using analysis of variance or chi-square tests. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to explore the relationship between hourly mean PA (in SD units) and the risk of outcome occurrence. The relative acceleration was calculated by dividing hourly average acceleration by daily mean acceleration, adjusted for non-wear time bias to exclude overall PA intensity. K-means cluster analysis was used to cluster patients with similar temporal activity patterns. The number of clusters (K) was determined by the within-sum-of-squares (WSS) plot. The stability of the resulting cluster solution was assessed using bootstrap resampling (100 iterations) and quantified by the Jaccard similarity index. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to explore the relationship between clusters and cardiovascular and death risks. To account for potential competing events, competing risk analyses were additionally performed using the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model. For the outcome of incident CVD, all-cause death was considered as the competing event. For the outcome of CVD mortality, non-cardiovascular death was considered as the competing event. Subgroup analysis was performed according to sex (male, female), age (< 65 years, ≥ 65 years), BMI (< 30 kg/m2, ≥ 30 kg/m2), diabetes duration (< 5 years, ≥ 5 years), and baseline glycated hemoglobin levels [glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), ≤ 7%, > 7%]. Sensitivity analysis was further performed by excluding people who experienced outcome events in the first 2 years of follow-up.

RESULTS

A total of 3,143 patients with T2DM with an average age of 65.90 ± 6.65 years were included in the analysis, of which 1,949 (62.01%) were men. The baseline characteristics of the participants and the characteristics of the cluster groups are shown in Table 1. The baseline characteristics of the subcohort for the incident CVD analysis (n = 2,236) are provided in Supplementary Table 1. The median follow-up time was 7.82 years, with 13.91%, 13.53%, and 9.61% of patients experiencing CVD, cardiovascular-related death, and all-cause death, respectively.

Demographics and characteristics of the participants in the total population and in relative acceleration pattern clusters

| Characteristics | Total population (N = 3,143) | Cluster 1 (N = 1,040) | Cluster 2 (N = 510) | Cluster 3 (N = 1,593) | P |

| Age (years) | 65.90 ± 6.65 | 65.71 ± 7.05 | 65.28 ± 6.97 | 66.23 ± 6.26 | 0.010 |

| Sex, male (%) | 1,949 (62.01) | 694 (66.73) | 304 (59.61) | 951 (59.70) | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 2,844 (90.49) | 913 (87.79) | 456 (89.41) | 1,475 (92.59) | 0.002 |

| Asian or Asian British | 101 (3.21) | 42 (4.04) | 19 (3.73) | 40 (2.51) | |

| Black or Black British | 47 (1.50) | 21 (2.02) | 12 (2.35) | 14 (0.88) | |

| Other | 151 (4.80) | 64 (6.15) | 23 (4.51) | 64 (4.02) | |

| Qualification | |||||

| College or University | 968 (30.80) | 332 (31.92) | 147 (28.82) | 489 (30.70) | 0.396 |

| A levels/AS levels or equivalent | 390 (12.41) | 119 (11.44) | 68 (13.33) | 203 (12.74) | |

| 0 levels/GCSEs or CSEs or equivalent | 994 (31.63) | 344 (33.08) | 154 (30.20) | 496 (31.14) | |

| NVQ or HND or HNC or equivalent | 256 (8.15) | 89 (8.56) | 42 (8.24) | 125 (7.85) | |

| None of above | 535 (17.02) | 156 (15.00) | 99 (19.41) | 280 (17.58) | |

| Household income | |||||

| < £18 K | 709 (22.56) | 188 (18.08) | 174 (34.12) | 347 (21.78) | < 0.001 |

| £18 K -< £52 K | 1,526 (48.55) | 531 (51.06) | 216 (42.35) | 779 (48.90) | |

| £52K -< £100 K | 449 (14.29) | 154 (14.81) | 57 (11.18) | 238 (14.94) | |

| ≥ £100 K | 85 (2.70) | 12 (2.35) | 40 (2.51) | ||

| Unclear | 374 (11.90) | 134 (12.88) | 51 (10.00) | 189 (11.86) | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Yes | 281 (8.94) | 74 (7.12) | 81 (15.88) | 126 (7.91) | < 0.001 |

| No | 2,851 (91.71) | 959 (92.21) | 429 (84.12) | 1,463 (91.84) | |

| Unclear | 11 (0.35) | 7 (0.67) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.25) | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| Yes | 2,813 (89.50) | 934 (89.81) | 427 (83.73) | 1,452 (91.15) | < 0.001 |

| No | 326 (10.37) | 105 (10.10) | 82 (16.08) | 139 (8.73) | |

| Unclear | 4 (0.13) | 1 (0.10) | 1 (0.20) | 2 (0.13) | |

| BMI | |||||

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 28 (0.89) | 7 (0.67) | 13 (2.55) | 8 (0.50) | < 0.001 |

| 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 | 325 (10.34) | 117 (11.25) | 23 (4.51) | 185 (11.61) | |

| 25-29.9 kg/m2 | 1,106 (35.19) | 372 (35.77) | 127 (24.90) | 607 (38.10) | |

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 1,684 (53.58) | 544 (52.31) | 347 (68.04) | 793 (49.78) | |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.68 ± 1.15 | 6.70 ± 1.15 | 6.88 ± 1.35 | 6.60 ± 1.06 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep chronotype | |||||

| Morning | 1,748 (55.62) | 754 (72.50) | 172 (33.73) | 822 (51.60) | < 0.001 |

| Evening | 1,069 (34.01) | 185 (17.79) | 286 (56.08) | 598 (37.54) | |

| Unclear | 326 (10.37) | 101 (9.71) | 52 (10.20) | 173 (10.86) | |

| Average acceleration (mg) | 22.66 ± 6.96 | 23.43 ± 6.94 | 18.00 ± 6.41 | 23.65 ± 6.55 | < 0.001 |

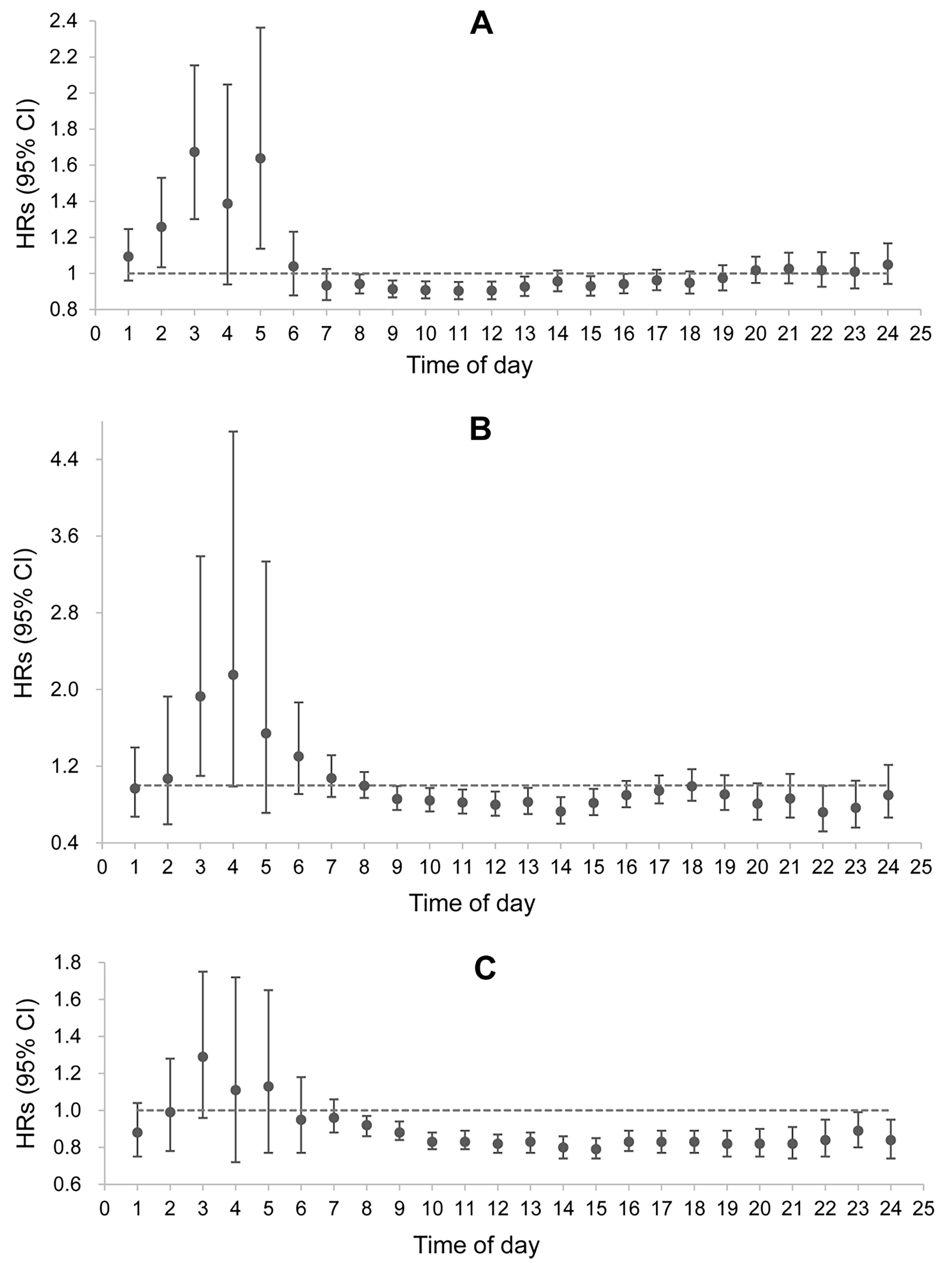

The results of the multifactorial Cox proportional hazards regression model showed that high hourly PA was associated with a low risk of CVD and cardiovascular-related death in patients with T2DM, mainly from

Figure 2. Association between hourly physical activity (in SD units) and cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality. (A) The risk on incident cardiovascular disease; (B) The risk of cardiovascular mortality; (C) The risk on all-cause mortality. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model was adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, qualification, household income, smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, sleep chronotype, and glycated hemoglobin A1c at baseline. Results should be interpreted with caution due to multiple comparisons. These analyses are exploratory and should not be interpreted as causal. HR: Hazard ratio; BMI: body mass index.

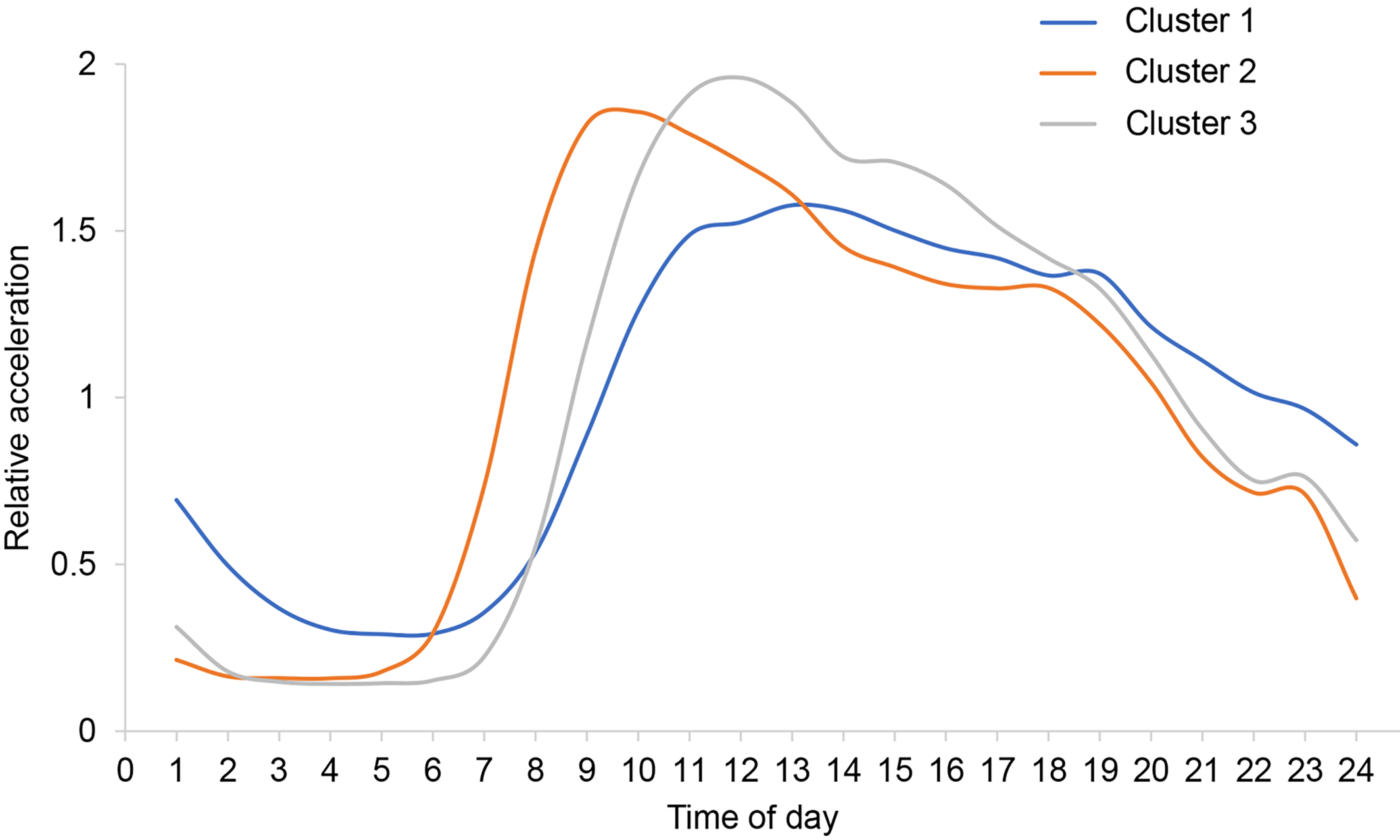

The WSS plot identified three clusters [Supplementary Figure 1]. The 3-cluster solution demonstrated excellent stability, with a mean Jaccard similarity index of 0.958 based on 100 bootstrap replicates, indicating highly replicable cluster assignments. Figure 3 shows the average relative acceleration distribution of each cluster throughout the day. Cluster 1 (N = 1,040) is characterized by a relatively even distribution of daytime PA. Cluster 2 (N = 510) shows a peak in PA around 8-9 am, and Cluster 3 (N = 1,593) shows a peak in PA around 11-12 am.

Figure 3. Clusters of relative acceleration patterns. The relative acceleration was calculated by dividing each hourly acceleration mean by each individual total day acceleration mean (adjusted for non-wear time bias). Cluster 1: A relatively uniform distribution of physical activity intensity during the day; Cluster 2: physical activity peak at around 8-9 a.m. daily; Cluster 3: physical activity peak at around 11-12 a.m. daily.

After adjusting for potential confounding factors, the risk of CVD occurrence was reduced in Cluster 2 and Cluster 3 compared with Cluster 1, with hazard ratios (HRs) of 0.449 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.318-0.634] and 0.493 (95%CI: 0.363-0.670), respectively; the risk of ACM was also reduced in both groups, with HRs of 0.625 (95%CI: 0.448-0.873) in Cluster 2 and 0.548 (95%CI: 0.403-0.746) in Cluster 3. There was no statistically significant change in the risk of CVD mortality in either group [Table 2]. No difference in the risk of CVD and mortality was found between Clusters 2 and 3 [Supplementary Table 2]. The results of Fine-Gray competing risk analyses were consistent with our primary analyses [Supplementary Table 3]. Sensitivity analyses that further adjusted for baseline insulin use and diabetes duration produced results consistent with the primary models [Supplementary Table 4], indicating that these factors did not substantially confound the observed associations.

Association between pattern clusters of relative acceleration and risk of cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality

| Crude HR (95%CI) | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||

| Cluster 1 | Ref | Ref |

| Cluster 2 | 0.482 (0.356-0.653) | 0.449 (0.318-0.634) |

| Cluster 3 | 0.511 (0.388-0.672) | 0.493 (0.363-0.670) |

| Cardiovascular mortality | ||

| Cluster 1 | Ref | Ref |

| Cluster 2 | 0.543 (0.265-1.112) | 0.772 (0.342-1.741) |

| Cluster 3 | 0.396 (0.197-0.795) | 0.590 (0.276-1.261) |

| All-cause mortality | ||

| Cluster 1 | Ref | Ref |

| Cluster 2 | 0.578 (0.429-0.778) | 0.625 (0.448-0.873) |

| Cluster 3 | 0.495 (0.374-0.656) | 0.548 (0.403-0.746) |

Subgroup analysis showed that the relationship between PA clusters and the risk of CVD and CVD mortality was similar across sex, age, BMI, diabetes duration, and baseline HbA1c groups and in the overall population. In patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, Clusters 2 and 3 were associated with a reduced risk of ACM compared with Cluster 1, while in those with a BMI < 30 kg/m2, this relationship was not observed. In male patients younger than 65 years, those who had T2DM for 5 years or more, and those with baseline HbA1c ≤ 7%, Cluster 3 was associated with a reduced risk of ACM compared with Cluster 1, while no difference was found with Cluster 2. Sensitivity analysis of only those who did not experience outcome events in the first

DISCUSSION

This prospective cohort study using data from the UK Biobank explored for the first time the relationship between the timing of PA and the risk of CVD and mortality in T2DM patients. In these patients, increased PA at around 8 am to 4 pm was associated with a reduced risk of CVD and cardiovascular mortality, while increased PA during the day and in the evening (but not in the early morning) was associated with a reduced risk of ACM. Increased PA in the early morning (especially around 3 am) was associated with an increased risk of CVD and death. This study identified three distinct groups according to their pattern of PA timing in patients with T2DM, characterized by either evenly distributed daytime activity, a peak in activity around

PA can improve blood sugar control in patients with T2DM and reduce cardiovascular risk factors[21,22]. An epidemiological study showed that patients with T2DM who exercise regularly have significantly reduced mortality risk[23]. Previous studies have mostly investigated the relationship between PA types, intensities, frequencies, and durations and the occurrence and development of chronic diseases such as T2DM[24]. For example, all types of PA [i.e., endurance, resistance, high-intensity interval training (HIIT), and stretching] have been found beneficial for blood sugar control and cardiovascular health in T2DM[25]. In this study we directed our attention to the timing of PA (i.e., when is the health benefit of PA the greatest?). The results suggest that the timing of PA may be an additional independent risk factor for CVD in patients with T2DM, adding a new dimension to the prevention of CVD and death in these patients.

Our study found that concentrating PA in the morning or at noon is beneficial for reducing the risk of ACM and CVD in patients with T2DM, a result supported by previous studies[12,16,26]. Sato et al. reported that PA at the beginning of the active phase in the morning has a stronger impact on metabolism and better enhances health benefits than PA at the beginning of the rest phase in the evening[12]. Another study found that PA at 10:30 am was more effective in reducing hyperglycemia and the risk of CVD or mortality than PA at

Some studies have reached inconsistent conclusions, with greater reductions in blood sugar with PA in the afternoon or evening[15,27], or no difference in glucose response between morning, afternoon, and evening PA[28]. In addition, a cross-sectional study on the adaptability of exercise training in patients with T2DM found that, compared with morning exercisers, those who exercised at noon had significantly improved HbA1c and cardiopulmonary function[29]. Brito et al. also showed that evening exercise was associated with better heart rate recovery and blood pressure reduction than morning exercise[30]. Furthermore, in men with T2DM, afternoon exercise was more effective at improving blood sugar than morning exercise. Savikj and colleagues also pointed out that morning exercise has an acute detrimental effect on blood sugar levels[15]. These studies show the harmful nature of morning exercise for patients with T2DM, which does not contradict our study, because the beneficial activity times we found are concentrated later than early morning (i.e., 8-9 am and 11-12 pm). These inconsistent conclusions may result from different measurement methods and definitions of PA, population heterogeneity, small sample sizes of related studies, and the choice of lifestyle adjustment variables. This study used accelerometer data on objective PA levels, which can accurately identify PA, and was conducted in a representative and objective large UK sample.

Several studies in experimental animals support our findings. For example, Sato et al.[12] found that in mice, the timing of exercise is a key factor in expanding the beneficial effects of exercise on skeletal muscle metabolic pathways and systemic energy homeostasis, which in turn is related to CVD occurrence[31]. They also found that in mice exercising in the early active phase, the transcription of glycolysis-related genes was enhanced, and a strong activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) pathway in skeletal muscle was reported. This pathway helps activate glycolysis rather than oxidative phosphorylation during exercise under low-oxygen conditions. In addition to metabolic effects, HIF1α also coordinates circadian rhythms, making this pathway one of the potential mechanisms of the positive effects of morning activity in humans. Several human studies have shown a link between morning PA and better cardiometabolic health[9,32-34]. In patients with T2DM, the impact of PA on hormone levels, metabolic products, and multi-tissue metabolic profiles/skeletal muscle proteome profiles may depend in part on circadian rhythms. For example, compared with afternoon HIIT, morning HIIT increases plasma carbohydrates through the pentose phosphate pathway and decreases skeletal muscle lipids and the abundance of mitochondrial complex III. Morning or evening exercise appears to have subtle but unique metabolic responses,[35] which may also explain our finding that increased PA around 3 am is associated with an increased risk of CVD and death.

This study has several strengths, including a large sample size and a nationally representative cohort. In addition, PA was objectively collected using accelerometers, and we used cluster methods to identify PA subgroups. This data-based method of grouping is more representative of the natural characteristics of this population than pre-set groupings. This study also has limitations. First, it is not possible to determine the nature and type of the PA. However, previous studies have shown that PA of any nature (leisure, exercise, or work) and type (endurance, resistance, HIIT, or stretching) confer health benefits[25]. Second, the baseline data measurement took place earlier than the accelerometer measurement, which may lead to misclassification when assessing PA. Third, only 7 days of accelerometer data were collected. However, previous studies have collected two sets of 7-day accelerometer measurement data separated by 2-3 years, and the results showed a high internal correlation between PA and sedentary behavior, indicating that a 7-day measurement cycle is representative[36]. Fourth, although we adjusted for many potential confounding factors, residual confounding effects may remain. Fifth, the definition of T2DM relied on registry and self-reported data without universal confirmation by glucose criteria or medication records. While this is a common approach in large cohort studies, it may lead to some non-differential misclassification. Sixth, we derived activity timing patterns from data averaged across all valid days, and did not separately analyze potential differences in patterns between weekdays and weekends, which may represent distinct behavioral contexts. Seventh, despite excluding events occurring within the first two years of follow-up in a sensitivity analysis, we cannot fully rule out reverse causality. Participants with subclinical or deteriorating health may have reduced or shifted their daily activity patterns before a clinical event was recorded, which could bias the observed associations. Such bias would likely attenuate the true protective effect of PA, meaning that the HRs we report might be conservative estimates. Eighth, while we identified clusters based on timing patterns, it remains unclear whether the observed differences in outcomes are driven primarily by activity timing or overall activity volume. Although we adjusted for daily average acceleration, residual confounding by total activity volume cannot be completely ruled out. Ninth, accelerometer-derived activity data cannot distinguish voluntary exercise (e.g., leisure-time PA) from activity driven by occupational demands or health-related factors (e.g., restlessness due to poor glycemic control). This limits our ability to infer whether the observed associations reflect the timing of intentional exercise or the timing of general daily movement. Furthermore, the identified clusters showed differences in baseline characteristics such as BMI, income, and sleep chronotype. While we adjusted for these factors in our models, residual confounding due to this heterogeneity remains a possibility. Finally, the observed association between early morning (2-5 am) activity and increased risk should be interpreted with caution. This activity may reflect non-typical sleep-wake patterns (e.g., shift work) or underlying sleep disorders rather than a harmful effect of activity per se.

In summary, our study suggests that for patients with T2DM, engaging in PA in the late morning or at noon is associated with a lower risk of CVD and ACM. Time-dependent PA interventions may constitute an additional benefit for managing cardiovascular and mortality risks in these patients. These findings require confirmation in randomized controlled trials or interventional studies.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Contributed equally to this work: Wang J, Zeng J

Conceived the idea for the paper: Xu S, Xing Y, Zeng J, Wang J

Acquired the data: Xu S

Prepared the data for analysis and analyzed the data: Zeng J, Wang J, Yang W

Interpreted the results: Xu S, Xing Y, Wang J, Zeng J, Yang W, Chen B, Fan M, Zhang Z

Wrote the first draft: Wang J, Zeng J, Xing Y

All authors critically revised the paper for intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

UK Biobank data can be requested by bona fide researchers for approved projects, including replication studies, through https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was partly supported by the Provincial Natural Science Fund Program (Key Project of Joint Fund) (No. 2023AFD031) and the Xi’an Science and Technology Plan Program (Innovation Capability Support Program, No. 23YXYJ0118).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The UK Biobank was approved by the North-West Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent. The present study was conducted using the UK-Biobank Resource (Application Number 92014).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Bommer C, Sagalova V, Heesemann E, et al. Global economic burden of diabetes in adults: projections from 2015 to 2030. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:963-70.

2. Morrish NJ, Wang SL, Stevens LK, Fuller JH, Keen H. Mortality and causes of death in the WHO Multinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44:S14-21.

3. Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Saydah S, et al. Trends in death rates among U.S. adults with and without diabetes between 1997 and 2006: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1252-7.

4. Balakumar P, Maung-U K, Jagadeesh G. Prevalence and prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113:600-9.

5. Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67-492.

6. Kodama S, Tanaka S, Heianza Y, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:471-9.

7. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:S60-82.

8. Weitzer J, Castaño-Vinyals G, Aragonés N, et al. Effect of time of day of recreational and household physical activity on prostate and breast cancer risk (MCC-Spain study). Int J Cancer. 2021;148:1360-71.

9. Chomistek AK, Shiroma EJ, Lee IM. The relationship between time of day of physical activity and obesity in older women. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:416-8.

10. Qian J, Walkup MP, Chen SH, et al; Look AHEAD Research Group. Association of objectively measured timing of physical activity bouts with cardiovascular health in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:1046-54.

11. Ezagouri S, Zwighaft Z, Sobel J, et al. Physiological and molecular dissection of daily variance in exercise capacity. Cell Metab. 2019;30:78-91.e4.

12. Sato S, Basse AL, Schönke M, et al. Time of exercise specifies the impact on muscle metabolic pathways and systemic energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2019;30:92-110.e4.

13. Scheer FA, Hu K, Evoniuk H, et al. Impact of the human circadian system, exercise, and their interaction on cardiovascular function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20541-6.

14. Qian J, Scheer FA, Hu K, Shea SA. The circadian system modulates the rate of recovery of systolic blood pressure after exercise in humans. Sleep. 2020;43:zsz253.

15. Savikj M, Gabriel BM, Alm PS, et al. Afternoon exercise is more efficacious than morning exercise at improving blood glucose levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomised crossover trial. Diabetologia. 2019;62:233-7.

16. Albalak G, Stijntjes M, van Bodegom D, et al. Setting your clock: associations between timing of objective physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk in the general population. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023;30:232-40.

17. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573-7.

18. Doherty A, Jackson D, Hammerla N, et al. Large scale population assessment of physical activity using wrist worn accelerometers: the UK biobank study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169649.

19. Feng H, Yang L, Liang YY, et al. Associations of timing of physical activity with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort study. Nat Commun. 2023;14:930.

20. Klimentidis YC, Raichlen DA, Bea J, et al. Genome-wide association study of habitual physical activity in over 377,000 UK Biobank participants identifies multiple variants including CADM2 and APOE. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1161-76.

21. Little JP, Gillen JB, Percival ME, et al. Low-volume high-intensity interval training reduces hyperglycemia and increases muscle mitochondrial capacity in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:1554-60.

22. Jelleyman C, Yates T, O’Donovan G, et al. The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:942-61.

23. Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Yardley JE, et al. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: a position statement of the american diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:2065-79.

24. Tipton CM. The history of “exercise is medicine” in ancient civilizations. Adv Physiol Educ. 2014;38:109-17.

25. Kanaley JA, Colberg SR, Corcoran MH, et al. Exercise/physical activity in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a consensus statement from the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022;54:353-68.

26. DiPietro L, Gribok A, Stevens MS, Hamm LF, Rumpler W. Three 15-min bouts of moderate postmeal walking significantly improves 24-h glycemic control in older people at risk for impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3262-8.

27. Moholdt T, Parr EB, Devlin BL, Debik J, Giskeødegård G, Hawley JA. The effect of morning vs evening exercise training on glycaemic control and serum metabolites in overweight/obese men: a randomised trial. Diabetologia. 2021;64:2061-76.

28. Munan M, Dyck RA, Houlder S, et al. Does exercise timing affect 24-hour glucose concentrations in adults with type 2 diabetes? A follow up to the exercise-physical activity and diabetes glucose monitoring study. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44:711-8.e1.

29. Hetherington-Rauth M, Magalhães JP, Rosa GB, et al. Morning versus afternoon physical activity and health-related outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:1172-5.

30. Brito LC, Peçanha T, Fecchio RY, et al. Comparison of morning versus evening aerobic-exercise training on heart rate recovery in treated hypertensive men: a randomized controlled trial. Blood Press Monit. 2021;26:388-92.

31. Hower IM, Harper SA, Buford TW. Circadian rhythms, exercise, and cardiovascular health. J Circadian Rhythms. 2018;16:7.

32. Albalak G, Stijntjes M, Wijsman CA, et al. Timing of objectively-collected physical activity in relation to body weight and metabolic health in sedentary older people: a cross-sectional and prospective analysis. Int J Obes. 2022;46:515-22.

33. Schumacher LM, Thomas JG, Raynor HA, Rhodes RE, Bond DS. Consistent morning exercise may be beneficial for individuals with obesity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2020;48:201-8.

34. Park S, Jastremski CA, Wallace JP. Time of day for exercise on blood pressure reduction in dipping and nondipping hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:597-605.

35. Savikj M, Stocks B, Sato S, et al. Exercise timing influences multi-tissue metabolome and skeletal muscle proteome profiles in type 2 diabetic patients - a randomized crossover trial. Metabolism. 2022;135:155268.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].