Association between wearable device usage and obesity transition in children and adolescents: a nationwide longitudinal study

Abstract

Aim: Wearable devices have the potential to promote healthy behaviors, yet evidence on their effectiveness in pediatric populations remains scarce. This study aims to investigate the association between wearable device usage and the transition to obesity among Chinese children and adolescents, addressing critical gaps in evidence regarding optimal usage patterns and subgroup variations for obesity prevention.

Methods: Using longitudinal data from the 2019-2020 National Student Physical Health Survey (n = 5,006), this study examined associations between wearable device/mobile app usage frequency (categorized as frequent, sometimes, occasional, rare, or never use) and obesity transition among children and adolescents aged 9-18. Multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for demographics were employed, with subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, and residence.

Results: Compared to frequent users, rare/never users showed a tendency toward higher risks of transitioning to obesity [odds ratio (OR) = 1.50, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.04-2.18, P = 0.030]. Sometimes users had the lowest risk of physical inactivity (OR = 0.61, 95%CI: 0.51-0.73, P < 0.001), whereas never users demonstrated a higher risk of prolonged sedentary behavior (OR = 1.36, 95%CI: 1.11-1.67, P = 0.003). Subgroup analyses revealed stronger associations in rural areas (OR = 2.99, 95%CI: 1.23-7.25, P = 0.016 for overweight transition in occasional users) and boys (OR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.05-3.68, P = 0.035 for overweight transition in rarely users).

Conclusion: Moderate, rather than frequent, use of wearable devices may optimally mitigate obesity risk in children, potentially avoiding technology fatigue from overuse. Rural-urban and gender disparities highlight the need for context-specific interventions. Wearable device use may mitigate pediatric obesity risk primarily by reducing sedentary behavior and increasing physical activity time, with optimal benefits at moderate usage frequency. These findings emphasize prioritizing usage quality over device adoption rates in public health strategies.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, childhood and adolescent obesity (OB) has emerged as a critical global public health challenge. The prevalence of overweight (OW) and obesity among children and adolescents aged 5-19 years has increased nearly tenfold over the past four decades globally[1]. This trend is particularly pronounced in China, where the overweight and obesity rates among 7-18-year-olds reached 24.2% by 2019, reflecting a significant rise compared to data from the previous decade[2,3]. Obesity not only elevates the risk of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and other chronic conditions but also exerts profound impacts on mental health and social adaptation in adolescents[4,5,6]. Addressing this pressing issue necessitates the development of effective obesity intervention strategies, which remain a priority in public health research.

The rapid advancement of digital health technologies has introduced wearable devices as a novel approach to obesity prevention and control. Devices such as smartwatches and fitness trackers enable real-time monitoring of key health metrics, including physical activity, sleep quality, and heart rate, while promoting sustained health behaviors through data feedback mechanisms[7,8,9]. Existing studies demonstrate that wearable devices significantly enhance exercise adherence and weight management outcomes in adult populations[10,11]. However, research focusing on children and adolescents remains limited, with most evidence derived from small-scale studies or short-term interventions, lacking robust longitudinal data from nationally representative samples. This gap hinders a comprehensive understanding of the potential role of wearable devices in mitigating pediatric obesity.

Current research often relies on geographically restricted or homogeneous cohorts, limiting the generalizability of findings. Moreover, the predominance of cross-sectional designs impedes reliable causal inference. Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying the effects of wearable devices, such as whether they reduce obesity risk by increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary time, or improving sleep quality, remain inadequately explored. These knowledge gaps underscore the need for nationwide longitudinal studies to systematically evaluate the relationship between wearable device usage and obesity transition in children and adolescents, as well as its potential mediating pathways.

Leveraging large-scale data from the 2019-2020 Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH), this longitudinal study aims to investigate the dynamic association between wearable device usage and obesity development in children and adolescents. The study addresses three core questions: (1) whether obesity transition rates differ significantly among device users; (2) whether device usage influences obesity development through modifications in health behaviors, such as increased physical activity or reduced sedentary time; and (3) whether these associations vary by age, gender, or residential location (urban vs. rural). By addressing these questions, this research provides critical empirical evidence to advance the understanding of digital health technologies in pediatric health promotion.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This longitudinal analysis used baseline data (2019) from the CNSSCH[12]. A stratified random sampling approach selected eight provinces (Shanghai, Fujian, Shanxi, Henan, Hunan, Gansu, Chongqing, Guangxi) representing eastern, central, and western regions for follow-up assessment in November 2020. From the initial baseline cohort of 14,532 adolescents aged 9-18 years [Figure 1], 9,814 age-eligible participants were retained for descriptive statistics. Final analytical samples comprised 5,006 respondents meeting complete questionnaire criteria (aged 9-18 years), excluding younger children (6-8 years), lacking survey participation, and older participants with critical data deficiencies (e.g., physical activity metrics). The protocol received ethics committee approval from Peking University Health Science Center (IRB00001052-18002, IRB00001052-21001), with written informed consent obtained from all participants and legal guardians.

Anthropometric overweight (OW) and obesity (OB) measurements and transition

Certified staff conducted anthropometric assessments using standardized protocols, with participants barefoot in light clothing. Height and weight were measured to 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg precision, respectively. The body mass index (BMI) derived from weight(kg)/height(m)2 informed obesity status classification according to China’s National Health Commission age- and gender-specific percentiles[13]: overweight (OW) ≥ 85th percentile, obesity (OB) ≥ 95th percentile. Overweight transition was operationalized as progression from baseline normal weight, thinness status, to OW during follow-up. Obesity transition was operationalized as progression from baseline normal weight, thinness, or OW status to OB during follow-up.

Wearable devices usage assessment

The frequency of wearable device usage was assessed through a structured question: “How often do you use wearable devices (e.g., smartwatches, fitness trackers)?” As the questionnaire aggregated these two modalities, they were analyzed together as a single exposure variable in the present study. Participants selected from five predefined response options: “Frequently”, “Sometimes”, “Occasionally”, “Rarely”, and “Never”. Responses were subsequently coded as an ordinal variable (1-5) for analytical purposes. These terms reflected perceived frequency rather than quantifiable usage. To ensure consistency, pilot testing confirmed participants’ clear understanding of both the device scope (limited to movement-sensing wearables) and temporal definitions before nationwide implementation. While both tools target physical activity monitoring, their behavioral mechanisms differ. Aggregating these two modalities in the exposure variable may dilute modality-specific effects.

Questionnaire survey

Certified field staff distributed structured paper questionnaires to participants aged 9-18 years during regular school hours. Utilizing a self-administered format with researcher oversight for clarification needs, the instrument systematically captured: Sociodemographic profiles: age, gender, residential location, grade level, singleton status, and parental educational attainment. Health-related behaviors: frequency of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, daily sleep patterns, and physical activity engagement. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines on Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents, which recommend that children and adolescents aged 5-17 years accumulate at least 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily. Our study used “≥ 1 h” to align with this guideline, as MVPA is the primary component of physical activity associated with obesity prevention. Based on the prior epidemiological studies using the 8-h threshold for sedentary time, which note that sedentary time exceeding 8 h per day is associated with an increased risk of obesity[8]. Psychometric evaluation confirmed moderate reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.76) for institutional-level measures within the survey framework[14].

Statistical analysis

Missing values were imputed using hot-deck imputation[15], where each missing case was matched to a donor with similar age, sex, and residential location. This method was selected due to the low proportion of missing data and the categorical nature of key covariates, which made multiple imputation less efficient and unnecessary for bias reduction in this context. Categorical variations by sex and residence were evaluated via χ² tests, whereas age-dependent trends were evaluated using Mantel-Haenszel linear trend analysis. Multilevel logistic regression models estimated adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for behavioral predictors of overweight/obesity incidence and transitions, incorporating province-level random intercepts to accommodate hierarchical data structures. Fixed effects adjustments included demographic (age, sex, urban/rural residence, singleton status), dietary (breakfast frequency, sugar-sweetened beverage consumption), and socioeconomic covariates (parental education), with multicollinearity excluded through variance inflation factor verification [all variance inflation factor (VIF) < 5]. Analyses were executed in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 26.0 and R 4.2.2 using two-tailed significance thresholds (α = 0.05). Sensitivity testing redefined OW/OB using International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) pediatric criteria[16], a global reference standard, to confirm findings consistency, and the relevant results are provided in the supplementary materials [Supplementary Figure 1].

RESULTS

Association between wearable device usage and risk of obesity transition during the follow-up

Table 1 presents the distribution of wearable device usage and characteristics of the study population stratified by gender groups in the 2019-2020 follow-up study. A total of 5,006 participants were included, with 2,501 boys and 2,505 girls. The incidence of overweight and obesity was higher in boys than in girls (overweight: 17.3% vs. 11.3%; obesity: 12.2% vs. 10.5%), with significant differences (P < 0.001). The transition to overweight and obesity also had gender-related variations, with higher proportions in boys. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes baseline and transition characteristics stratified by wearable device usage frequency. For wearable device usage, boys were more likely to use them frequently (13.6%) compared to girls (11.0%), while girls had a higher proportion of never using wearable devices (34.8% vs. 38.8% in boys), and these differences were significant (P < 0.001).

Distribution of wearable device usage and characteristics of the study population stratified by gender groups of the 2019-2020 follow-up study

| Variables | Total (n = 5,006) | Boys (n = 2,501) | Girls (n = 2,505) | P value |

| Residence | < 0.001 | |||

| Urban | 2,754 (55.0) | 1,321 (52.8) | 1,433 (57.2) | |

| Rural | 2,252 (45.0) | 1,180 (47.2) | 1,072 (42.8) | |

| Incidence | < 0.001 | |||

| Overweight | 723 (14.4) | 438 (17.5) | 285 (11.4) | |

| Obesity | 573 (11.4) | 309 (12.4) | 264 (10.5) | |

| Transition | < 0.001 | |||

| Overweight | 309 (6.2) | 172 (6.9) | 137 (5.5) | |

| Obesity | 508 (10.1) | 267 (10.7) | 241 (9.6) | |

| Wearable devices utilization | 0.183 | |||

| Frequently | 625 (12.5) | 345 (13.8) | 280 (11.2) | |

| Sometimes | 725 (14.5) | 337 (13.4) | 388 (15.5) | |

| Occasionally | 767 (15.3) | 371 (14.8) | 396 (15.8) | |

| Rarely | 1,019 (20.4) | 461 (18.5) | 558 (22.3) | |

| Never | 1,870 (37.3) | 987 (39.5) | 883 (35.2) | |

| PA time | 0.007 | |||

| < 1 h | 2,721 (54.4) | 1,301 (52.0) | 1,405 (56.2) | |

| ≥ 1 h | 2,285 (45.6) | 1,200 (48.0) | 1,100 (43.8) | |

| Sedentary behavior | 0.623 | |||

| < 8 h | 3,211 (64.1) | 1,597 (63.9) | 1,610 (64.3) | |

| ≥ 8 h | 1,795 (35.9) | 904 (36.1) | 895 (35.7) | |

| Weekday outdoor time (min), Mean ± SD | 208.31 ± 320.56 | 219.28 ± 346.34 | 197.31 ± 292.09 | 0.019 |

| Weekend outdoor time (min), Mean ± SD | 106.65 ± 147.19 | 115.54 ± 155.23 | 97.71 ± 138.10 | < 0.001 |

| Weekday sedentary time (min), Mean ± SD | 43.49 ± 20.56 | 43.47± 21.01 | 43.51 ± 20.11 | 0.805 |

| Weekend sedentary time (min), Mean ± SD | 22.06 ± 8.74 | 22.01 ± 8.63 | 22.02 ± 8.04 | 0.762 |

| Single-child status | < 0.001 | |||

| only child | 1,763 (35.2) | 970 (38.8) | 791 (31.6) | |

| Not only child | 3,243 (64.8) | 1,531 (61.2) | 1,714 (68.4) | |

| Breakfast frequency | 0.264 | |||

| Eat breakfast every day | 3,865 (77.2) | 1,947 (77.8) | 1,913 (76.4) | |

| Do not eat breakfast every day | 1,151 (22.8) | 554 (22.2) | 592 (23.6) | |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage intake | < 0.001 | |||

| Drink | 3,935 (78.6) | 2,031 (81.2) | 1,900 (75.8) | |

| Do not drink | 1,071 (21.4) | 470 (18.8) | 605 (24.2) | |

| Sleeping duration | 0.012 | |||

| ≥ 8 h | 3,200 (63.9) | 1,647 (65.9) | 1,562 (62.4) | |

| < 8 h | 1,806 (36.1) | 854 (34.1) | 943 (37.6) | |

| Maternal education level | 0.630 | |||

| Primary school | 746 (14.9) | 363 (14.5) | 386 (15.4) | |

| Junior or senior high school | 3,080 (61.5) | 1,548 (61.9) | 1,532 (61.2) | |

| College degree or above | 1,180 (23.6) | 590 (23.6) | 587 (23.4) | |

| Paternal education level | 0.603 | |||

| Primary school | 504 (10.1) | 251 (10.1) | 253 (10.1) | |

| Junior or senior high school | 3,201 (63.9) | 1,619 (64.7) | 1,582 (63.2) | |

| College degree or above | 1,301 (26.0) | 631 (25.2) | 670 (26.7) |

In crude models, compared to frequent users, occasional and sometimes users exhibited the lowest risks of transitioning to overweight and obesity, while both rare and never users showed elevated risks [Figure 2]. After adjusting for age, sex, urban/rural residence, and baseline BMI, the dose-response relationship became more pronounced: the adjusted OR for transitioning to overweight increased progressively with reduced usage frequency. Specifically, occasionally users (OR = 1.61, 95%CI: 1.00-2.58, P = 0.050), rare users (OR = 1.55, 95%CI: 0.95-2.51, P = 0.077), and never users (OR = 1.56, 95%CI: 0.99-2.46, P = 0.058) showed numerically elevated risks compared to frequent users, but these associations did not reach conventional statistical significance. Similarly, for transitioning to obesity, rarely users exhibited a significantly higher risk (OR = 1.50, 95%CI: 1.04-2.18, P = 0.030), while never users demonstrated a borderline trend (OR = 1.39, 95%CI: 0.98-1.98, P = 0.066) that was not statistically significant. Collectively, this trend indicates a nonlinear, U-shaped dose-response relationship, suggesting that moderate usage (sometimes/occasional) provides the most protective effect.

Figure 2. Association Between wearable devices usage and obesity transition in 2019-2020 follow-up study. Adjusted for age, sex, residence, single-child status, breakfast frequency, sugar-sweetened beverage intake, sleeping duration, and parental education level. OR: Odds ratios; CI: confidence interval.

Association of wearable device usage with obesity transition across subgroups

We further explored the heterogeneity in the association between wearable device/mobile fitness app usage frequency and obesity transition risks through subgroup analyses [Figure 3]. Stratified by age, the ORs for transitioning to overweight or obesity across usage frequency categories showed no statistical significance in either the 9-12-year or 13-18-year age groups, though the OR trends aligned with the primary analysis, suggesting a potential link between low-frequency usage and elevated risk.

Figure 3. Association Between wearable devices usage and obesity transition in 2019-2020 follow-up study by subgroups. Adjusted for age, sex, residence, single-child status, breakfast frequency, sugar-sweetened beverage intake, sleeping duration, and parental education level. OR: Odds ratios; CI: confidence interval; NA: not available.

Sex-stratified analyses revealed that boys in the rare-use group had significantly higher risks of transitioning to overweight (OR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.05-3.68, P = 0.035) and obesity (OR = 1.62, 95%CI: 1.01-2.60, P = 0.045), whereas girls exhibited a significant association only in the occasional-use group for obesity transition (OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.00-3.38, P = 0.049).

Residence-stratified results demonstrated that rural participants in the occasional-use (OR = 2.99, 95%CI: 1.23-7.25, P = 0.016) and rare-use (OR = 2.55, 95%CI: 1.07-6.08, P = 0.034) groups had significantly elevated risks of transitioning to overweight compared to frequent users, while no significant associations were observed in urban areas. These findings indicate gender and residence-specific disparities in the relationship between wearable device usage frequency and obesity transition. While subgroup analyses suggest higher risks in rural children and boys when device usage is low, this does not imply that frequent use always confers greater benefit. Instead, it highlights stronger sensitivity to device engagement in these subgroups, potentially due to contextual factors such as limited access to alternative health resources or gender-related behavioral responses.

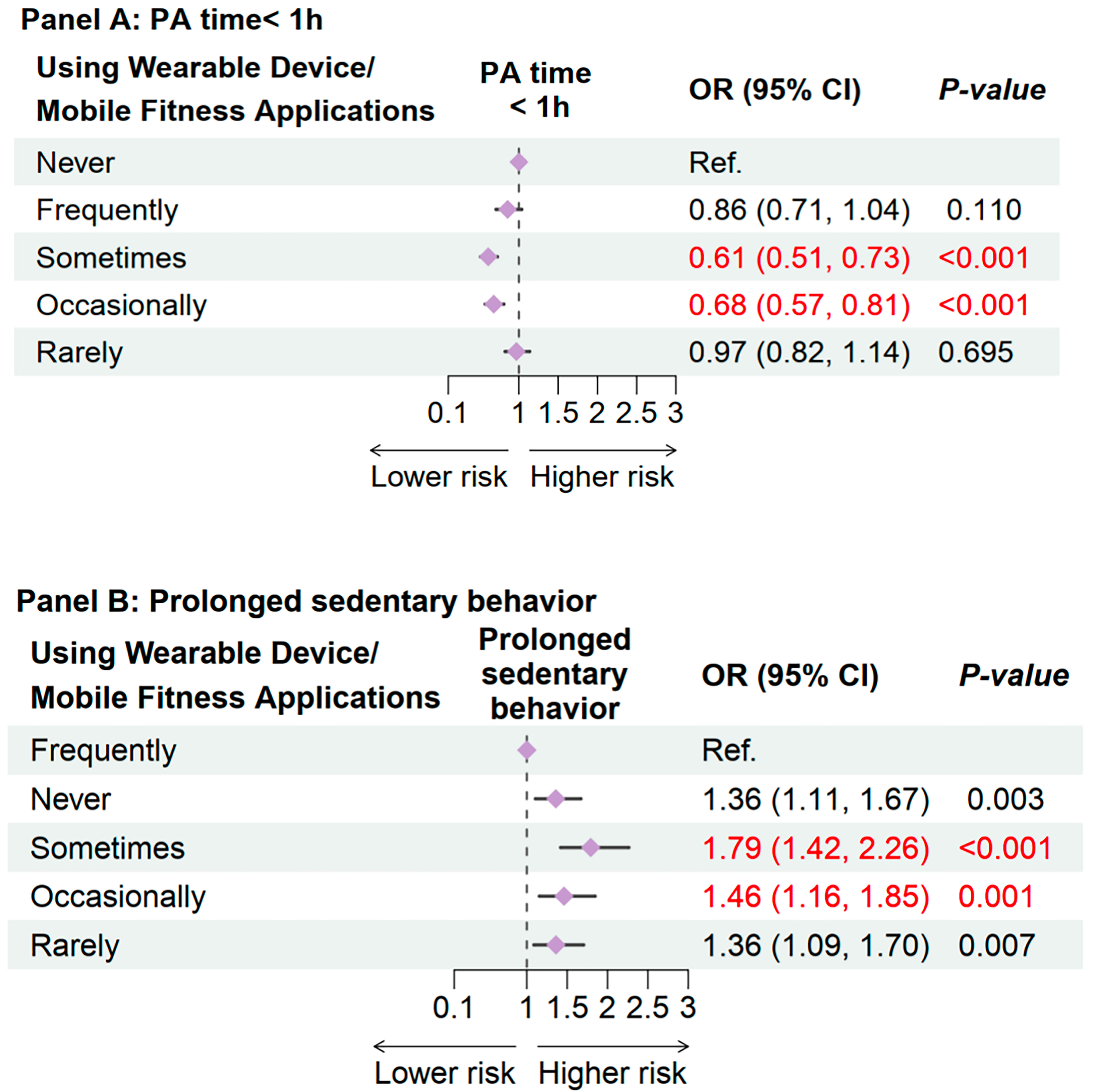

Association between wearable device usage and physical activity time, prolonged sedentary behavior

Figure 4 shows the association between wearable device usage frequency and the risk of insufficient physical activity. Using never-users as the reference group, the analysis revealed that frequent users had a non-significant reduction in physical inactivity risk (OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.71-1.04, P = 0.110). In contrast, occasional users (OR = 0.61, 95%CI: 0.51-0.73, P < 0.001) and intermittent users (OR = 0.68, 95%CI: 0.57-0.81, P < 0.001) exhibited significantly lower risks of inadequate physical activity (PA), suggesting a higher likelihood of meeting the recommended daily PA guideline of ≥ 1 h. However, rare users showed no significant difference compared to never-users (OR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.82-1.14, P = 0.695). These results indicate a descriptive U-shaped trend in the associations: moderate device usage (i.e., occasional or intermittent use) was associated with the most substantial PA improvement, whereas both excessive (frequent use) and minimal (rare use) engagement failed to yield significant benefits. This pattern implies that periodic, rather than constant, device interaction may optimally motivate PA adherence in children and adolescents, potentially by balancing behavioral reinforcement with avoiding technology fatigue.

Figure 4. Association Between wearable devices usage and insufficient PA time, prolonged sedentary behavior. Adjusted for age, sex, residence, single-child status, breakfast frequency, sugar-sweetened beverage intake, sleeping duration, and parental education level. PA: Physical activity; OR: odds ratios; CI: confidence interval.

We also identified a significant inverse association between wearable device usage frequency and prolonged sedentary behavior risk [Figure 4]. Compared to frequent users, all lower-frequency user groups exhibited elevated sedentary risks: never-users had an OR of 1.36 (95%CI: 1.11-1.67, P = 0.003), while sometimes-users showed the highest risk (OR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.42-2.26, P < 0.001). Similarly, occasional users (OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.16-1.85, P = 0.001) and rare users (OR = 1.36, 95%CI: 1.09-1.70, P = 0.007) demonstrated significantly increased risks.

These results indicate a clear dose-response gradient: as device usage frequency decreased (from sometimes-use to never-use), sedentary risk escalated progressively, with the steepest rise observed in sometimes-users (OR = 1.79). This pattern suggests that intermittent use may fail to counteract sedentary habits due to insufficient sustained behavioral reinforcement. Notably, the findings align with the PA time analysis, collectively supporting a mechanistic pathway whereby wearable devices improve health behaviors through activity reminders and sedentary interruption.

The consistency across outcomes underscores that frequent device engagement may optimize behavioral regulation by balancing real-time feedback with habituation avoidance, whereas sporadic use limits sustained benefits. These insights advocate for integrating wearable devices into pediatric obesity interventions, emphasizing consistent but non-intrusive usage to maximize long-term adherence.

DISCUSSION

This nationwide longitudinal study provides the first robust evidence elucidating the nuanced relationships between wearable device usage frequency and obesity transition, PA time, and sedentary behavior in children and adolescents. Our findings partially align with adult studies demonstrating that device-mediated behavioral feedback can enhance health outcomes[17]. Moreover, we revealed a distinctive pediatric-specific pattern: moderate usage (occasional/sometimes use) emerged as the optimal frequency, associated with significantly longer PA time, lower sedentary risk, and reduced obesity transition compared to both frequent and rare/never use.

This inverted U-shaped dose-response relationship challenges the conventional assumption that “more frequent use yields better outcomes” and indicates the existence of a critical threshold in younger populations. Beyond this threshold, the efficacy of wearable devices diminishes. The observed discrepancy may be associated with developmental and behavioral psychological mechanisms: excessive reminders from frequent device use may induce habituation or reactance in children, thereby reducing long-term engagement[18]. In contrast, moderate use enables intermittent reinforcement, which sustains user motivation without imposing excessive burden. Furthermore, over-reliance on wearable devices may inadvertently undermine intrinsic motivation by prioritizing external metrics over the internal enjoyment derived from physical activity, and may even lead to technology habituation, burnout, and subsequent device abandonment[19,20]. Moderate use, by comparison, can strike a balance between enhancing effectiveness and avoiding user overload. Notably, our study did not collect neurocognitive or neuroimaging data. Thus, the aforementioned explanations only provide potential references for the observed inverted U-shaped relationship and should not be considered as definitive conclusions. Future studies should integrate psychological assessments or neurocognitive markers to empirically verify these potential pathways.

Subgroup analyses highlighted significant heterogeneity, with stronger associations observed in rural areas and boys. Rural children, who often lack access to alternative health resources, may derive greater benefits from device usage as a compensatory intervention[21]. The heightened sensitivity to wearable device usage observed in rural areas emerges from complex interactions between structural disparities and psycho-social dynamics. Rural children’s increased responsiveness aligns with the resource substitution paradigm, wherein wearable devices disproportionately compensate for systemic healthcare deficits, rural areas exhibit fewer sports facilities and less frequent parental health supervision compared to urban centers[22,23]. This scarcity elevates devices from supplementary tools to primary behavioral regulators, magnifying their marginal utility. Moreover, beyond limited access to alternative health resources, parental companionship disparities, a defining feature of rural Chinese childhood, may further amplify the benefits of wearable devices in rural areas. In China, an estimated 61 million rural children are “left-behind” (parents migrate to urban areas for work), resulting in reduced in-person supervision of physical activity and health behaviors[24]. For these children, wearable devices may act as a “proxy supervisor”: real-time activity reminders compensate for absent parental guidance, while app-synced data allow remote parents to monitor and encourage activity. In contrast, urban children typically have more consistent parental companionship to prompt physical activity, making wearable devices a supplementary tool rather than a critical substitute. This “compensatory effect” of devices in rural settings explains why the association between usage frequency and obesity transition is stronger there. Thus, wearable devices may help mitigate rural-urban obesity disparities not only by increasing activity tracking but also by offsetting gaps in parental supervision. Nevertheless, the small number of cases in certain subgroups resulted in wide CIs, indicating less precise estimates. These findings should thus be interpreted with caution, and future studies with larger subgroup samples are needed to validate these patterns.

Gender disparities in device efficacy reflect gendered technosocialization processes. Boys’ stronger alignment with wearable interventions stems from congruence between device functionalities and masculine behavioral schemas, quantified goal-setting (higher likelihood than girls) and social competitiveness (greater engagement in ranking systems) synergize with performance-oriented device features[25,26]. Conversely, girls’ physical activities, such as dance or yoga, may exhibit lower motion-tracking accuracy, undermining perceived utility. These differences are compounded by intrinsic motivation patterns: boys demonstrate higher self-determination in technology adoption, whereas girls rely more on external accountability mechanisms that are less supported by current device designs[27].

Our findings elucidate two distinct behavioral pathways: a 39% reduced risk of physical inactivity (sometimes vs. never users: OR = 0.61) and a 79% elevated risk of sedentary behavior (sometimes vs. frequent users: OR = 1.79), collectively demonstrating the capacity of wearable devices to mitigate obesity risk through complementary mechanisms. For never-users initiating device engagement, real-time activity feedback disrupts sedentary patterns by prompting light-intensity movement, thereby accumulating beneficial physical activity duration[28]. Conversely, the sharp sedentary rebound among reduced-frequency users (frequent vs. sometimes) underscores devices’ role in maintaining baseline activity levels; withdrawal of regular feedback diminishes environmental cues that normally counteract prolonged sitting[29]. This bidirectional efficacy originates from two synergistic mechanisms: Device-generated alerts (vibration/visual) serve as external cues activating the prefrontal-striatal motivation circuit, triggering immediate PA initiation regardless of intensity[30]. Continuous usage establishes habitual “postural checks” (e.g., automatic 50-min sitting alerts), with neuroimaging evidence showing frequent users develop enhanced insula sensitivity to bodily inactivity signals[31]. Optimal obesity prevention occurs when devices sustain both PA reinforcement and sedentary disruption[32,33]. Our findings indicate a possible behavioral pathway through physical inactivity and sedentary behavior. However, this trend is exploratory and not based on formal mediation testing. Future studies collecting more detailed behavioral data will be necessary to statistically verify these mediating effects.

The generalizability of our findings to non-Chinese populations should be interpreted with caution, as China’s context differs in three key ways: (1) Device adoption: China has one of the highest pediatric wearable adoption rates globally[34], comparable to high-income countries such as the U.S., but higher than low-income countries. Our findings may apply to middle-and high-income countries with similar device access but not to low-income settings where wearable devices are scarce; (2) Health infrastructure: Rural China has fewer sports facilities and health resources than urban areas, making wearable devices a “compensatory tool” for activity monitoring[35,36]. In countries with more equitable rural-urban health infrastructure, the benefits of a wearable device may be less pronounced. These contextual differences could influence both usage behaviors and their health impacts. Therefore, while our study provides valuable evidence from a large, nationally representative Chinese cohort, replication in diverse international contexts is needed to confirm whether the observed U-shaped relationship between device use and obesity risk applies more broadly.

Public health authorities should prioritize optimizing usage patterns rather than indiscriminate device distribution. Tailored strategies - such as establishing evidence-based “minimum effective frequency” guidelines for high-risk subgroups and integrating device education into school curricula - could promote sustainable behavior change. From a policy perspective, our findings suggest that interventions should not only focus on promoting the adoption of wearable devices among children and adolescents but also on guiding optimal patterns of use. The observed U-shaped association indicates that moderate engagement, rather than continuous or excessive reliance, may maximize benefits while reducing the risk of technology fatigue. Schools and community health programs could therefore integrate structured guidance on using devices effectively, for example, by incorporating device-assisted activity monitoring into physical education curricula in a balanced manner. For practical implementation, we recommend parents and educators guide children/adolescents to use wearable devices 3-5 times per week, with each session limited to 10-15 min. This frequency avoids daily overuse or long-term disuse. Educators can integrate device use into physical education classes to reinforce moderate, purposeful engagement. In addition, health education initiatives should raise awareness among parents and students about the potential downsides of overuse, such as dependence on external metrics or loss of intrinsic motivation, and encourage strategies that foster sustainable, self-regulated physical activity. These insights highlight the importance of prioritizing usage quality and balance over simple device penetration rates when designing pediatric digital health interventions.

Limitations

While our findings advance understanding of pediatric wearable interventions, several limitations warrant cautious interpretation. First, residual confounding from unmeasured socio-technological factors, such as familial eHealth literacy gradients and device functionality disparities, may influence observed associations. Second, reliance on self-reported data for wearable device usage frequency and physical activity duration introduces the risk of recall bias. Participants may have overestimated or underestimated their actual device use or physical activity levels (e.g., forgetting occasional device use or overreporting compliant physical activity), which could potentially distort the observed associations between wearable device usage and obesity transition. While the CNSSCH survey was pilot tested for comprehension, no formal validation study of this specific question has been conducted. Third, the survey item aggregated wearable devices and mobile fitness apps into a single exposure measure. While both aim to monitor and promote physical activity, their behavioral mechanisms may differ: fitness trackers provide continuous feedback through sensors, whereas mobile apps may offer more intermittent or self-initiated feedback. Combining these modalities could therefore dilute modality-specific effects and obscure nuanced differences in behavioral pathways. Future research should differentiate between device-based and app-based usage, ideally using objective log data, to better capture their distinct contributions to obesity prevention. Fourth, we were unable to apply formal nonlinear modeling techniques because wearable device usage was assessed as an ordinal categorical variable rather than a continuous measure. This limited our ability to fully characterize the shape of the dose-response curve beyond categorical comparisons. Future studies that collect continuous or log-based usage data from devices or apps would enable more robust nonlinear modeling and provide deeper insight into the precise turning points of the U-shaped relationship observed in this study. Finally, several important potential confounders, such as parental BMI, household income, overall diet quality, and daily screen time, were not available in the CNSSCH dataset. The omission of these variables may have introduced residual confounding, as family background, socioeconomic status, and lifestyle factors are closely associated with both wearable device usage and obesity risk. Although we adjusted for a wide range of demographic and behavioral covariates, the possibility of unmeasured confounding cannot be excluded. Moreover, given the low level of missingness, hot-deck imputation was used to preserve sample representativeness; However, future work could apply multiple imputation for sensitivity analyses. Therefore, our effect estimates should be interpreted with caution, and future studies incorporating more comprehensive measures are warranted.

Conclusions

Moderate use of wearable devices appears to offer an optimal reduction in obesity risk among children, while potentially mitigating technology-related fatigue associated with excessive usage. Disparities related to geographic setting (rural vs. urban) and gender underscore the importance of developing context-specific intervention strategies. The beneficial effect of wearable devices on pediatric obesity risk is primarily mediated through the reduction of sedentary behavior and the increase in time spent in physical activity, with the greatest benefits observed at moderate frequencies of use. These findings highlight the need for public health initiatives to prioritize the quality and pattern of device usage over mere adoption rates. Such an approach may enhance the effectiveness of technology-based interventions aimed at combating childhood obesity.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the schoolteachers and investigators for their assistance in data collection and all students and their guardians for participating in the study.

Authors’ contributions

Have full access to all the data in the study and take final responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis: Li J (Jing Li), Zhang Z, Song Y

Concept and design: Li J (Jing Li), Zhang Z, Song Y

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Sun Z, Yang Y, Zhong X, Dang J

Drafting of the manuscript: Sun Z, Liu Y, Cai S, Li J (Jiaxin Li), Huang T

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Zhang X, Xue M

Obtained funding: Zhang Z, Song Y

Administrative, technical, or material support: Song Y

Supervision: Yang Y

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy reasons, but are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Financial support and sponsorship

The present research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Nos. 2024YFC2707901, 2024YFC270790103) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42370116).

Conflicts of interest

Yang Y is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Metabolism and Target Organ Damage. Yang Y was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling and decision making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University Health Science Center (approval: IRB00001052-18002, IRB00001052-21001). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents, guardians, or next of kin for the participation of minors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, et al; GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13-27.

2. Wang S, Dong YH, Wang ZH, Zou ZY, Ma J. [Trends in overweight and obesity among Chinese children of 7-18 years old during 1985-2014]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2017;51:300-5.

3. Luo D, Song Y. Socio-economic inequalities in child growth: identifying orientation and forward-looking layout. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;21:100412.

4. Piché ME, Tchernof A, Després JP. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2020;126:1477-500.

5. Chandrasekaran P, Weiskirchen R. The role of obesity in type 2 diabetes mellitus-an overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:1882.

6. Migueles JH, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Lubans DR, et al. Effects of an exercise program on cardiometabolic and mental health in children with overweight or obesity: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2324839.

7. Ocagli H, Agarinis R, Azzolina D, et al. Physical activity assessment with wearable devices in rheumatic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2023;62:1031-46.

8. Smith L, López Sánchez GF, Rahmati M, et al. Association between sedentary behavior and dynapenic abdominal obesity among older adults from low- and middle-income countries. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2024;36:109.

9. Pellegrini M, Lannin NA, Mychasiuk R, Graco M, Kramer SF, Giummarra MJ. Measuring sleep quality in the hospital environment with wearable and non-wearable devices in adults with stroke undergoing inpatient rehabilitation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:3984.

10. Spring B, Pfammatter AF, Scanlan L, et al. An adaptive behavioral intervention for weight loss management: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;332:21-30.

11. Li H, Sang D, Gong L, et al. Improving physical and mental health in women with breast cancer undergoing anthracycline-based chemotherapy through wearable device-based aerobic exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1451101.

12. Song Y, Ma J, Wang HJ, Wang Z, Lau PW, Agardh A. Age at spermarche: 15-year trend and its association with body mass index in Chinese school-aged boys. Pediatr Obes. 2016;11:369-74.

13. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Screening for Overweight and Obesity among School-Age Children and Adolescents. Available from: https://www.nhc.gov.cn/ewebeditor/uploadfile/2018/03/20180330094031236.pdf. [Last accessed on 17 Dec 2025].

14. Dong Y, Chen M, Chen L, et al. Individual-, family-, and school-level ecological correlates with physical fitness among chinese school-aged children and adolescents: a national cross-sectional survey in 2014. Front Nutr. 2021;8:684286.

15. Xiao H, Shen X, Li J, Yang X. A method for filling traffic data based on feature-based combination prediction model. Sci Rep. 2025;15:8441.

16. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240-3.

17. Babu M, Lautman Z, Lin X, Sobota MHB, Snyder MP. Wearable devices: implications for precision medicine and the future of health care. Annu Rev Med. 2024;75:401-15.

18. Caldwell JA, Caldwell JL, Thompson LA, Lieberman HR. Fatigue and its management in the workplace. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;96:272-89.

19. van Merriënboer JJ, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory in health professional education: design principles and strategies. Med Educ. 2010;44:85-93.

20. Schembre SM, Liao Y, Robertson MC, et al. Just-in-time feedback in diet and physical activity interventions: systematic review and practical design framework. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e106.

21. Basu J. Research on disparities in primary health care in rural versus urban areas: select perspectives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:7110.

22. Wang X, Zhang Y. Intergenerational care and rural childhood obesity in the digital era: based on screen exposure perspective. SSM Popul Health. 2024;27:101694.

23. Zhou M, Bian B, Zhu W, Huang L. The impact of parental migration on multidimensional health of children in rural China: the moderating effect of mobile phone addiction. Children. 2022;10:44.

24. Liu W, Wang W, Xia L, Lin S, Wang Y. Left-behind children's subtypes of antisocial behavior: a qualitative study in China. Behav Sci. 2022;12:349.

25. Tønnessen E, Svendsen IS, Olsen IC, Guttormsen A, Haugen T. Performance development in adolescent track and field athletes according to age, sex and sport discipline. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129014.

26. Balafoutas L, Fornwagner H, Sutter M. Closing the gender gap in competitiveness through priming. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4359.

27. Alarcón G, Morgan JK, Allen NB, Sheeber L, Silk JS, Forbes EE. Adolescent gender differences in neural reactivity to a friend’s positive affect and real-world positive experiences in social contexts. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2020;43:100779.

28. Veerubhotla A, Krantz A, Ibironke O, Pilkar R. Wearable devices for tracking physical activity in the community after an acquired brain injury: a systematic review. PM R. 2022;14:1207-18.

29. Strain T, Wijndaele K, Dempsey PC, et al. Wearable-device-measured physical activity and future health risk. Nat Med. 2020;26:1385-91.

30. Wang W, Cheng J, Song W, Shen Y. The effectiveness of wearable devices as physical activity interventions for preventing and treating obesity in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10:e32435.

31. Conger SA, Toth LP, Cretsinger C, et al. Time trends in physical activity using wearable devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies from 1995 to 2017. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022;54:288-98.

32. Cai S, Wang H, Zhang YH, et al. Could physical activity promote indicators of physical and psychological health among children and adolescents? An umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. World J Pediatr. 2025;21:159-73.

33. Leung AKC, Wong AHC, Hon KL. Childhood obesity: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2024;20:2-26.

34. Zhang Z, Xia E, Huang J. Impact of the moderating effect of national culture on adoption intention in wearable health care devices: meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10:e30960.

35. Xing Y, Ma Q, Cui M, et al. Overview and methods for chinese national surveillance on students’ common diseases and risk factors, 2022. Future. 2025;3:12.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].