Highly stable two-dimensional Fe3C18 monolayer and its bifunctional catalytic activity

Abstract

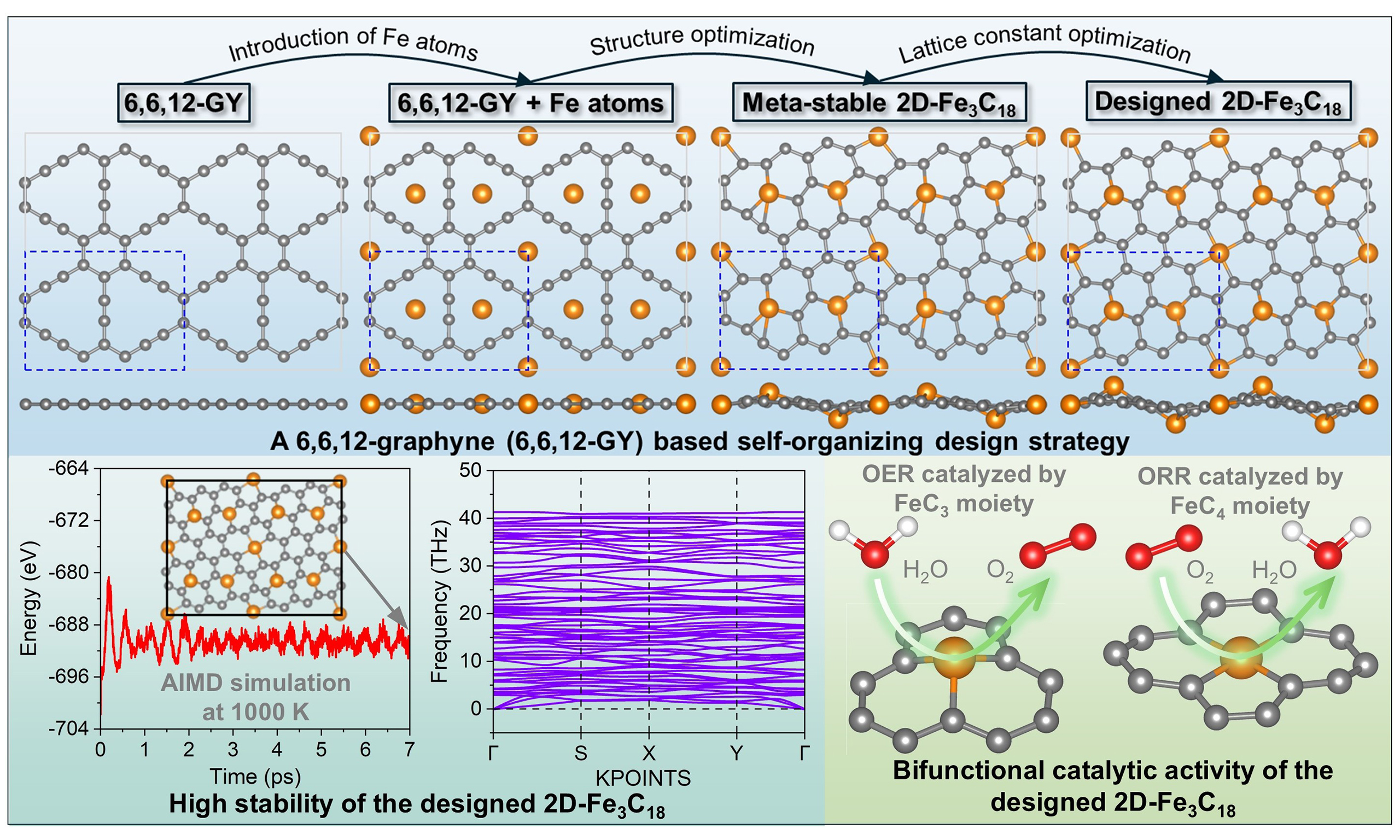

The incorporation of metal species into two-dimensional (2D) carbon materials has emerged as a predominant strategy for designing advanced catalytic systems. Nevertheless, conventional metal-carbon hybrid catalysts frequently suffer from limited metal loading capacity and poor structural stability, significantly constraining their practical applications. By first-principles calculations, we predict a novel type of highly stable 2D atomically thin iron-carbon crystal. The designed 2D crystal has a chemical composition Fe3C18 with both FeC3 and FeC4 moieties in one unit cell. We show that the 2D-Fe3C18 can possibly be fabricated from a self-organizing process upon anchoring Fe atoms on 6,6,12-graphyne. The unique structure of 2D-Fe3C18 boasts a high Fe loading of 43.7 wt%, and also leads to high stability of the material at a temperature up to 1,000 K. Owing to the different coordination environments, different Fe atoms in 2D-Fe3C18 exhibit distinct electrocatalytic properties. The FeC3 moiety is more active than FeC4 for oxygen evolution reaction while the FeC4 moiety is a better electrocatalyst than FeC3 towards oxygen reduction reaction. These studies pave the way for the future design of new functional 2D metal carbides with variable structures.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Developing high-performance catalysts is of considerable significance for advancing the sustainable development of human society[1-3]. The earliest catalysts that have attracted widespread study were metals and metal oxides, such as noble metal platinum (Pt)[4] and titanium dioxide (TiO2)[5]. The emergence of the concept of single-atom catalysis has propelled catalysis research to a new peak of development[6]. Loading the active centers (typically metals) onto a substrate is the most effective strategy for developing novel catalysts[7-9]. Compared with three-dimensional (3D) substrate materials, two-dimensional (2D) materials would be excellent substrates for hosting metal active centers due to their enormous specific surface area[9,10]. In the past decade, 2D metal-carbon systems, fabricated by doping metal species into graphene, have attracted significant research interest[7,11,12]. Modulating the interactions between metal species and the 2D carbon matrix has proven highly effective in tailoring the catalytic activity of metal sites, endowing these structures with considerable potential as single-atom catalysts (SACs)[8,9], dual-atom catalysts (DACs)[13,14], and single-cluster catalysts (SCCs)[15,16] for diverse chemical reactions.

Taking green and environmentally friendly electrocatalysis as an example, these novel 2D metal-carbon catalysts are expected to achieve performance comparable to that of metal and metal oxide catalysts, thereby jointly advancing the theoretical and applied research of electrocatalysis[17-20]. However, due to the inherently weak metal-carbon interaction, stabilizing the 2D metal-carbon structures often requires anchoring atoms (e.g., nitrogen) that exhibit strong interactions with both metal and carbon species[21,22]. Extensive studies have demonstrated that the catalytic performance of metal active sites is predominantly governed by their local coordination environment, and the commonly identified catalytic moieties in graphene-based metal-carbon systems present MCXN3-X and MCYN4-Y (X = 0, 1, 2, and 3; Y = 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4) local bonding conditions[7-9,23-25]. The introduction of anchoring atoms greatly disturbs the crystal structure of the 2D carbon support and, in general, makes the system highly disordered.

Recent studies have proposed alternative catalyst designs by directly embedding metal species into graphyne[26,27] and graphdiyne[28,29], which are two important series of 2D carbon allotropes, without introducing foreign dopants. However, these systems face challenges, including limited metal loading ratios and potential instability due to the aggregation of metal species. A promising development in this field is the recent proposal of 2D graphitic metal carbides (g-MCs), which exhibit exceptionally high metal-loading ratios and outstanding thermodynamic stability[30-32]. These materials can potentially be synthesized by anchoring individual metal atoms at each hollow site of γ-graphyne (γ-GY), thereby inducing a lattice reconstruction of the carbon framework[30]. This reconstruction process ultimately yields a periodic metal-carbon lattice with the chemical composition M2C12[30]. In 2D g-MCs, all metal atoms form bonds with their three nearest-neighbor carbon atoms, constituting the MC3 structural configuration[30,31]. The novel 2D

Inspired by the aforementioned graphene-based disordered metal-carbon configurations and γ-GY-based periodic g-MCs, it is natural to consider whether 2D metal carbides containing metal sites with various bonding conditions can be designed. In the reported 2D g-MCs, metal atoms are situated within the MC3 moiety, as the substrate, γ-GY, possesses only one type of hollow site suitable for anchoring metal atoms[30,31]. Another member of the graphyne family, known as 6,6,12-graphyne (6,6,12-GY), which features two types of hollow sites, may also serve as a possible substrate for the design of novel metal-carbon crystals[33,34]. Actually, 6,6,12-GY was theoretically proposed by Baughman et al. as early as 1987[35]; the experimental synthesis of large segments of 6,6,12-GY, however, was not achieved until 2019 through iterative acetylenic cross-coupling reactions[36]. Many theoretical and experimental works have confirmed the thermodynamic stability of 6,6,12-GY, but it has also been found that the phase stability of graphyne networks is relatively lower when compared with the graphene structure[34,36-39]. Thus, it can be preliminarily assumed that the lattice reconstruction of 6,6,12-GY carbon skeleton may be induced if a sufficiently strong external stimulus - for example, elevated temperature and strong adsorbate-support interaction - is applied to this 2D system[9,26,30]. The intrinsic presence of two types of anchoring sites in 6,6,12-GY holds the potential to facilitate the formation of novel 2D metal-carbon crystals with unique structural characteristics[33,38].

In this work, via state-of-the-art first-principles calculations, we propose a self-organizing design strategy based on 6,6,12-GY to produce a new atomically thin and highly stable 2D metal-carbon crystal, with its chemical composition of one unit cell being Fe3C18. The 2D-Fe3C18 crystal is made of periodic FeC3 and FeC4 moieties embedded in a 2D graphenic skeleton with a high metal loading ratio of 43.7 wt%. The unique atomic structure of 2D-Fe3C18 contributes to its high stability and special electronic properties. A key point to emphasize is that the FeC3 and FeC4 moieties in 2D-Fe3C18 have distinctly different catalytic activities, making it an intriguing bifunctional electrocatalyst towards oxygen reduction/evolution reaction (ORR/OER). This novel 2D-Fe3C18 derives its bifunctional electrocatalytic activity from the presence of two types of Fe active centers within the lattice, whereas conventional 2D metal-carbon configurations typically host only a single type of metal active center[7,27,30]. Our work paves the way for the rational design of a new class of functional 2D metal-carbon crystals.

CALCULATION METHODS

Computational details

The spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations in this work were carried out using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)[40,41]. The projector augmented wave (PAW)[42] pseudopotentials and a plane wave basis set with a kinetic cutoff energy of 500 eV were employed for all calculations. Additionally, the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) format of the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) was used for the exchange-correlation functional[43]. A vacuum layer of at least 15 Å was imposed in the direction perpendicular to the atomic plane of the carbon skeleton to eliminate the interaction between the replicas of periodic images, and all the structures were fully relaxed without any symmetry constraints. The Brillouin zone was sampled by a 3 × 4 × 1 Γ-centered k-point grid in the Monkhorst-Pack scheme[44], and the convergence criteria for the total energy and the residual Hellmann-Feynman force were set to be less than 10-4 eV and 10-2 eV Å-1, respectively. All these parameters were tested for the calculations in this work.

Evaluation of the stability of 2D-Fe3C18

The stability of 2D-Fe3C18 was preliminarily evaluated with the cohesive energy

where

Chemical bonding features of 2D-Fe3C18

The chemical bonding analyses of 2D-Fe3C18 were conducted using the solid-state adaptive natural density partition (SSAdNDP) method, which is regarded as an extension of the periodic natural bonding orbital method (PNBO)[47-49]. Compared with the PNBO method, which can only be used to reveal the bonding structures in the periodic materials from the perspective of localized bonds, including one-center (1c) bond (or lone pair) and two-center (2c) bond, the SSAdNDP technique can also distinguish the multi-center delocalized bonds by projecting the delocalized plane wave output from the VASP code to a localized atomic basis set. In this study, the atomic natural orbital third-order Douglas-Kroll (ANO-DK3) basis set is employed to carry out the chemical bonding analyses of 2D-Fe3C18[50].

Gibbs free energy calculation

The adsorption energy (Eads) in this study is defined as

where

G = E + ZPE - TS + GU + GpH,

where E is the electronic energy obtained from the DFT calculations, ZPE is the zero-point energy, S is the entropy, and T is the temperature (T = 298.15 K). Additionally, GU is the contribution to G from the electrode potential (U). More specifically, GU = -neU, where n is the total number of transferred electrons to the corresponding elementary step. GpH is the contribution to G from the pH value of electrolyte and

Additionally, the entropy corrections for adsorbates are considered to be zero, herein[23]. VASPKIT code was used for the post-processing of data[52].

In this study, the chemical potential of a proton-electron pair is defined as half the chemical potential of a gaseous H2 (G(H+) + G(e-) = 1/2 G(H2)), which has been demonstrated in the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model[53,54]. The limiting potential (UL) is defined as

where ΔGmax is the maximum change of Gibbs free energy of the two adjacent elementary electrochemical steps of ORR and OER. The overpotential (η) is, therefore, defined as

η = UL + U0 for ORR and η = UL - U0 for OER,

where U0 is the equilibrium potential of ORR and OER. Under acidic and alkaline conditions, the values of U0 are 1.23 V and 0.404 V, respectively, vs. standard hydrogen electrode (SHE)[23,53,55].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structure and electronic properties of 6,6,12-GY

In this study, 6,6,12-GY, which intrinsically features triangular and rhombic pores, is employed as the substrate. The pristine 6,6,12-GY exhibits a zero-gap semiconducting behavior with a combination of sp- and sp2-hybridized carbon atoms[39,56]. Each vertex carbon adopts sp2 hybridization, bonding with three adjacent carbons to form two C-C σ bonds and one C=C σ bond, while the acetylenic linkages feature sp-hybridized carbons connected via C≡C σ bonds. Furthermore, the carbon framework sustains a highly delocalized π-conjugated system. Prior to discussing the design strategy for 2D-Fe3C18, we first reproduced the atomic structure and electronic band structures of 6,6,12-GY [Supplementary Figure 1]. The results reveal that the optimized lattice parameters of 6,6,12-GY are a = 9.431 Å, b = 6.901 Å, and α = 90°; the intrinsic 6,6,12-GY behaves as a semi-metal or zero-gap semiconductor; notably, the presence of two distorted Dirac cones near the Fermi level (EF) underscores its electronic versatility. These findings are in excellent agreement with previous studies[33,39,56,57].

Self-organizing design strategy based on 6,6,12-GY

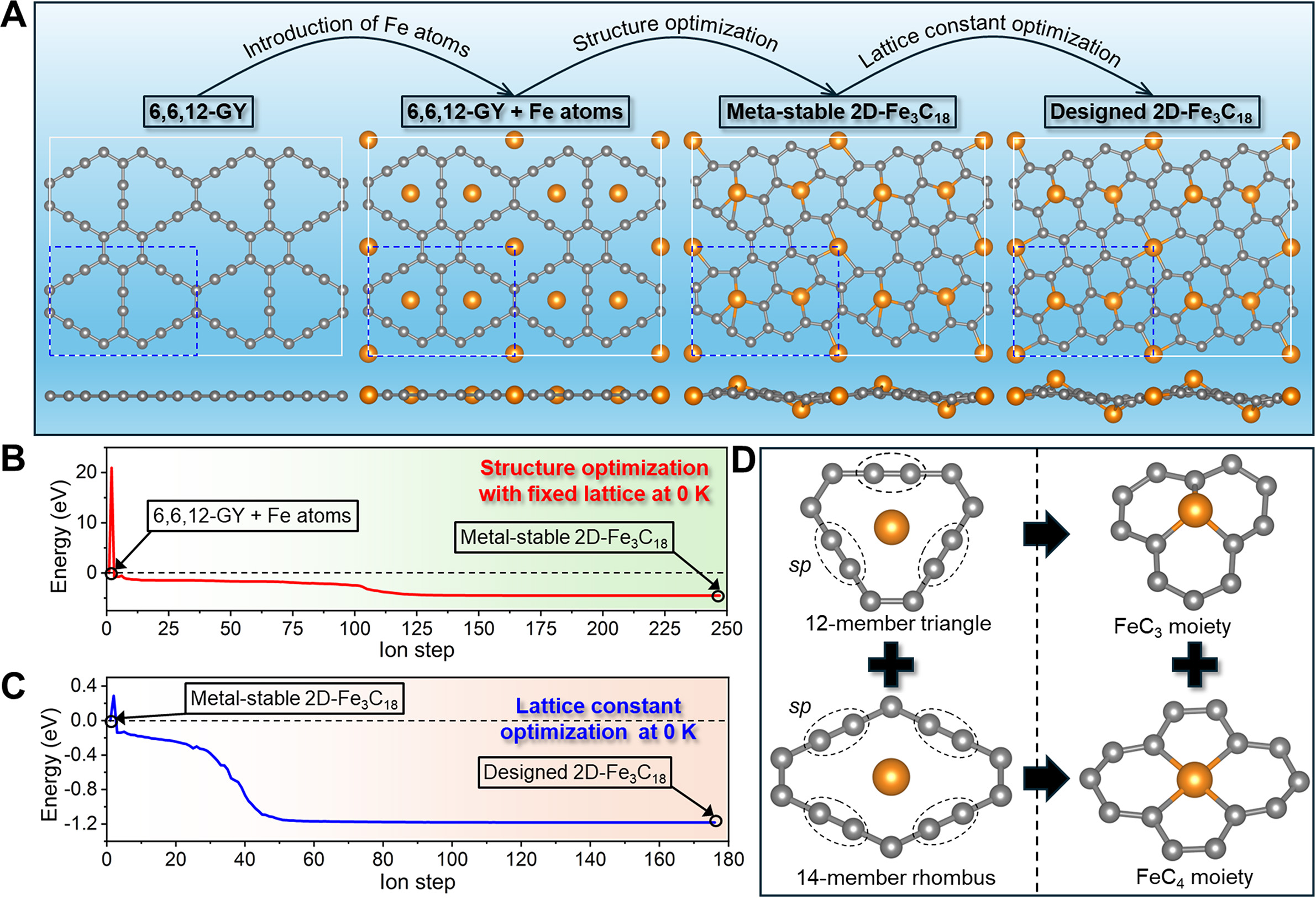

Based on the obtained 6,6,12-GY, a self-organizing design strategy is proposed for the prediction of the 2D-Fe3C18 lattice, which consists of three steps [Figure 1]. The first step is to introduce Fe atoms into the framework of 6,6,12-GY. The special structure of 6,6,12-GY makes it a promising substrate for anchoring metal species on its hollow sites. As shown in Figure 1A, three distinct types of hollow sites exist in 6,6,12-GY, namely, the centers of a six-member hexagon (6-MH), a 12-member triangle (12-MT), and a 14-member rhombus (14-MR). Previous studies have demonstrated that metal atoms adsorbed at the 6-MH site exhibit weak binding affinity, which may cause high mobility and eventual aggregation of metal atoms[58-60]. Consequently, this work focuses exclusively on anchoring single Fe atoms at the 12-MT and 14-MR sites in 6,6,12-GY, resulting in the “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms” configuration.

Figure 1. First-principles design of 2D-Fe3C18. (A) Schematic illustration of the 2D-Fe3C18 construction process, achieved by integrating Fe atoms with a 6,6,12-GY framework. The primitive cell is enclosed in blue dashed lines, with grey and orange balls representing C and Fe atoms, respectively. (B) Energy evolution during structure optimization (at 0 K) of “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms” configuration with fixed lattices, leading to the formation of meta-stable 2D-Fe3C18. (C) Energy evolution during lattice constant optimization (at 0 K) of meta-stable 2D-Fe3C18, resulting in the generation of designed 2D-Fe3C18. (D) Structural schematic showing the origin of FeC3 and FeC4 moieties within the skeleton of the designed 2D-Fe3C18.

The second step is to conduct structure optimization of the “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms” configuration under the conditions of fixed lattices and 0 K [Supplementary Video 1]. The energy evolution during the above process is given in Figure 1B, where significant energy reduction can be observed, and a meta-stable

The third step involves optimizing the lattice constants of meta-stable 2D-Fe3C18 [Supplementary Video 2]. Figure 1C illustrates the variation in total energy during this optimization process. Clearly, the final configuration (referred to as designed 2D-Fe3C18) exhibits a significantly lower energy compared to the meta-stable 2D-Fe3C18, with the lattices shrinking from a = 9.431 Å to a’ = 8.909 Å and b = 6.901 Å to

Compared with the previously reported 2D g-MCs[30,31], where all metal atoms present the same MC3 bonding configuration, it is worth mentioning that the designed 2D-Fe3C18 in this study shows both FeC3 and FeC4 moieties. The origin of the two different moieties can be attributed to the unique atomic structure of 6,6,12-GY. As shown in Figure 1D, the framework of 6,6,12-GY shows the combination of triangular (with three acetylenic linkages) and rhombic (with four acetylenic linkages) patterns. During the lattice reconstruction process (including the initial structure optimization and the subsequent lattice constant optimization), the originally sp-hybridized C atoms located in the acetylenic linkage undergo coordination with additional Fe atoms, with C≡C triple bonds converting to C=C double bonds, ultimately resulting in the formation of tri-coordinated FeC3 and tetra-coordinated FeC4 moieties. The integration of FeC3 and FeC4 moieties within the lattice of 2D-Fe3C18 is expected to yield distinctive properties and unlock novel applications. However, for the experimental synthesis of 2D-Fe3C18, the major challenge should be precisely dispersing individual Fe atoms into every pore of the 6,6,12-GY structure. It is expected that this theoretical work could inspire experimental researchers to explore methods for synthesizing this novel metal-carbon crystal.

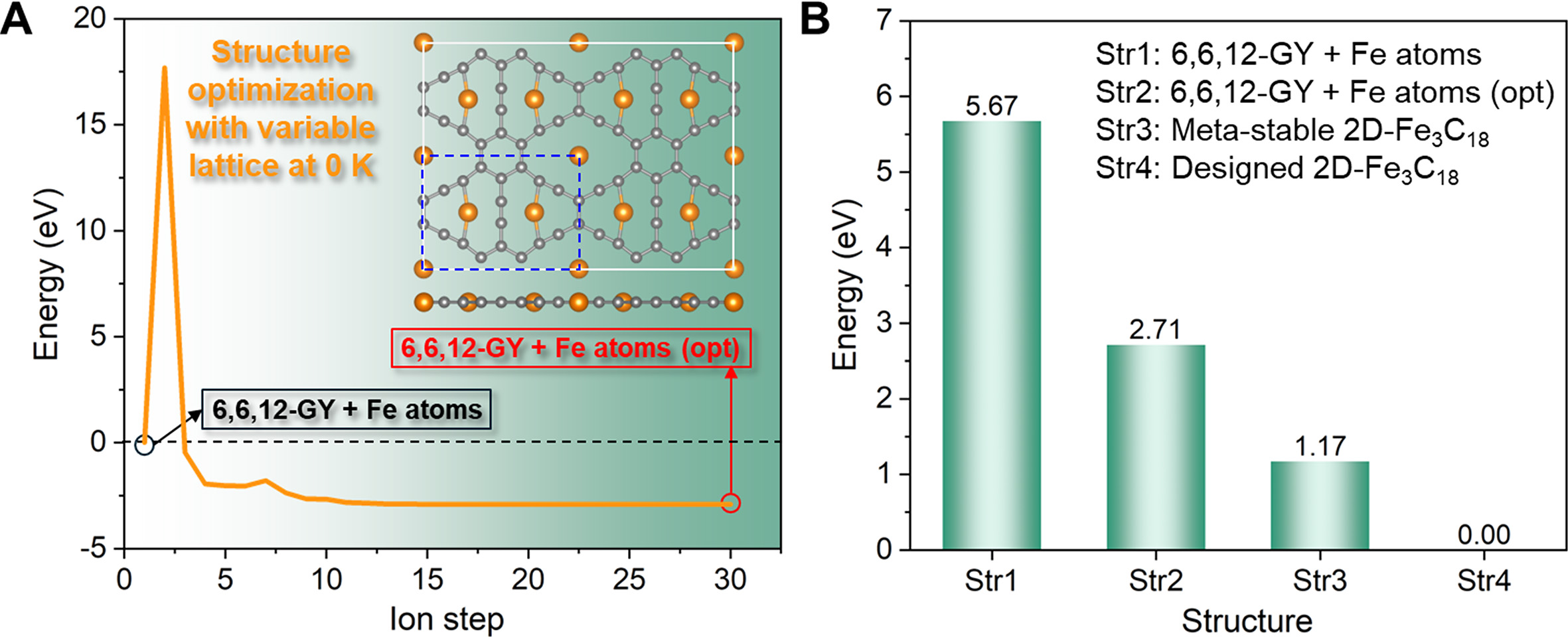

As outlined earlier, the proposed self-organizing design strategy involves the introduction of Fe atoms into 6,6,12-GY, followed by structure optimization of the “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms” configuration, and subsequent lattice constant optimization of the metastable 2D-Fe3C18. It is important to note that simultaneous optimization of both atomic coordinates and lattice parameters would lead to convergence towards a local minimum [Supplementary Video 3]. As evidenced in Figure 2A, a structure named “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms (opt)” is obtained after optimization, where the Fe atoms at the 12-MT sites are bonded with the two adjacent C atoms, whereas the Fe atoms at the 14-MR sites cannot form Fe-C σ bonds. Figure 2B displays the total energies of “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms”, “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms (opt)”, meta-stable 2D-Fe3C18, and designed 2D-Fe3C18. Obviously, the designed 2D-Fe3C18 is expected to be the most thermodynamically stable configuration.

Figure 2. Design results under variable-lattice structural optimization at 0 K. (A) Energy evolution during structure optimization of “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms” configuration, where the optimization finally converged to “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms (opt)”. The inset shows the atomic structure of “6,6,12-GY + Fe atoms (opt)”. (B) Energy comparison of different structures, where the energy of the designed 2D-Fe3C18 is set to 0 eV.

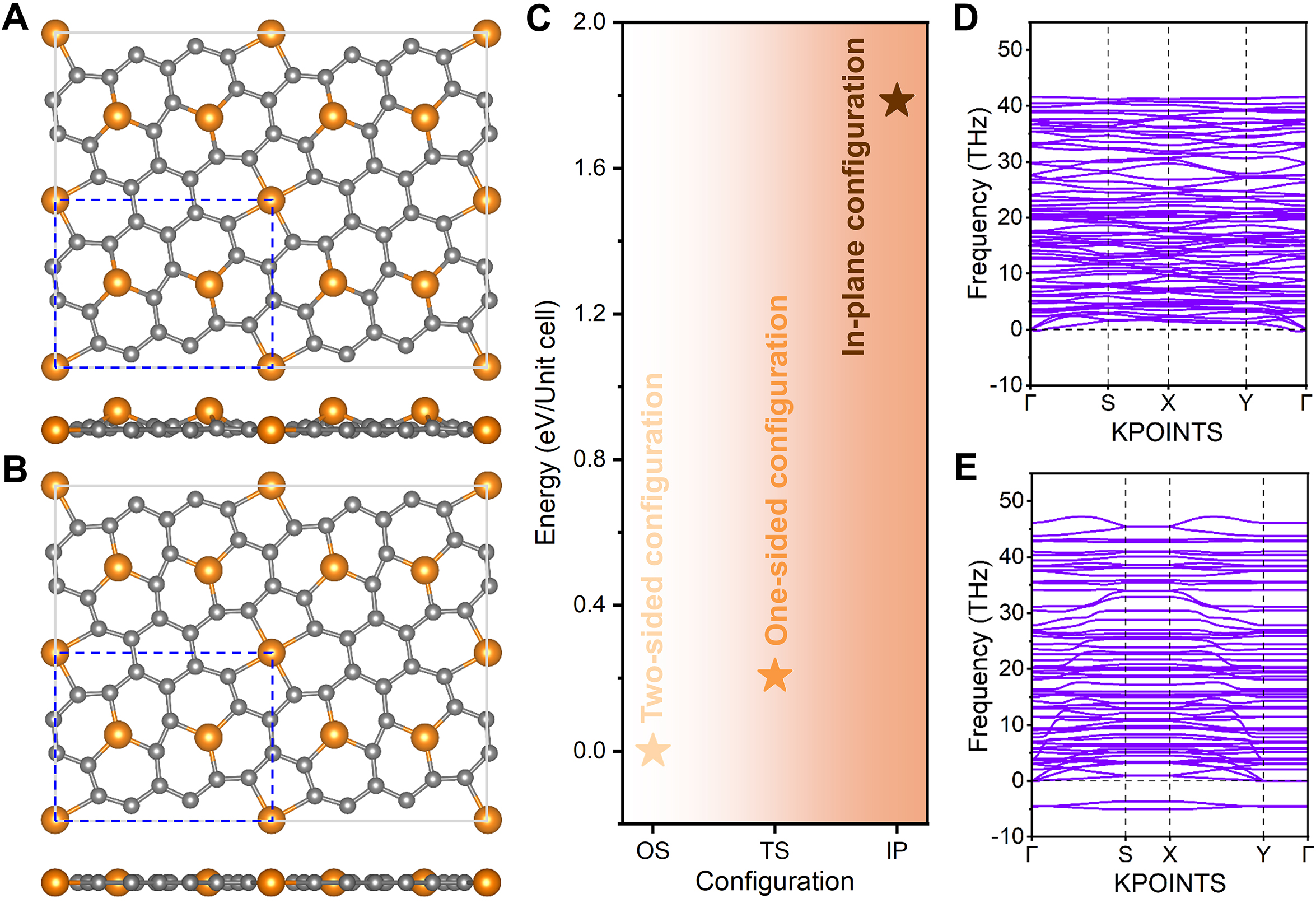

Ground-state configuration of 2D-Fe3C18

The designed 2D-Fe3C18 lattice possesses two types of Fe atoms, namely Fe3C and Fe4C. The relative positioning between Fe atoms and the carbon framework can be modulated to achieve distinct three configurations of the Fe-C lattice. The designed 2D-Fe3C18 is considered to be the two-sided configuration, as Fe3C atoms are alternately distributed on both sides of the carbon framework. The one-sided and in-plane configurations are displayed in Figure 3A and B, respectively. In Figure 3A, Fe3C atoms are exclusively localized on one side of the carbon framework, whereas in Figure 3B, Fe3C atoms are embedded within the interior of the carbon framework. By comparing the energies of the three configurations described above [Figure 3C], it can be concluded that the two-sided configuration has the lowest energy and represents the ground-state 2D-Fe3C18 structure. Therefore, the two-sided 2D-Fe3C18 would be the primary focus of the remainder of this study, with comprehensive discussions on its stability, electronic properties, and bifunctional catalytic activity. Prior to this, we still check the dynamic stability of the one-sided and in-plane configurations, and their phonon dispersion spectra are depicted in Figure 3D and E, respectively. The one-sided 2D-Fe3C18 should be dynamically stable, as all the vibrational modes are real in the entire Brillouin zone; however, prominent imaginary frequencies are observed in the case of the in-plane 2D-Fe3C18, indicating its dynamic instability. Hence, although this study primarily concentrates on the ground-state two-sided 2D-Fe3C18, the one-sided configuration also warrants further investigation in future research.

Figure 3. Other possible configurations of 2D-Fe3C18. Atomic structures of (A) one-sided and (B) in-plane 2D-Fe3C18 configurations. (C) Energy comparison of three configurations of 2D-Fe3C18, where the energy of the two-sided configuration (ground-state 2D-Fe3C18) is set to 0 eV. Phonon dispersion spectra of (D) one-sided and (E) in-plane 2D-Fe3C18 configurations.

Stability of ground-state 2D-Fe3C18

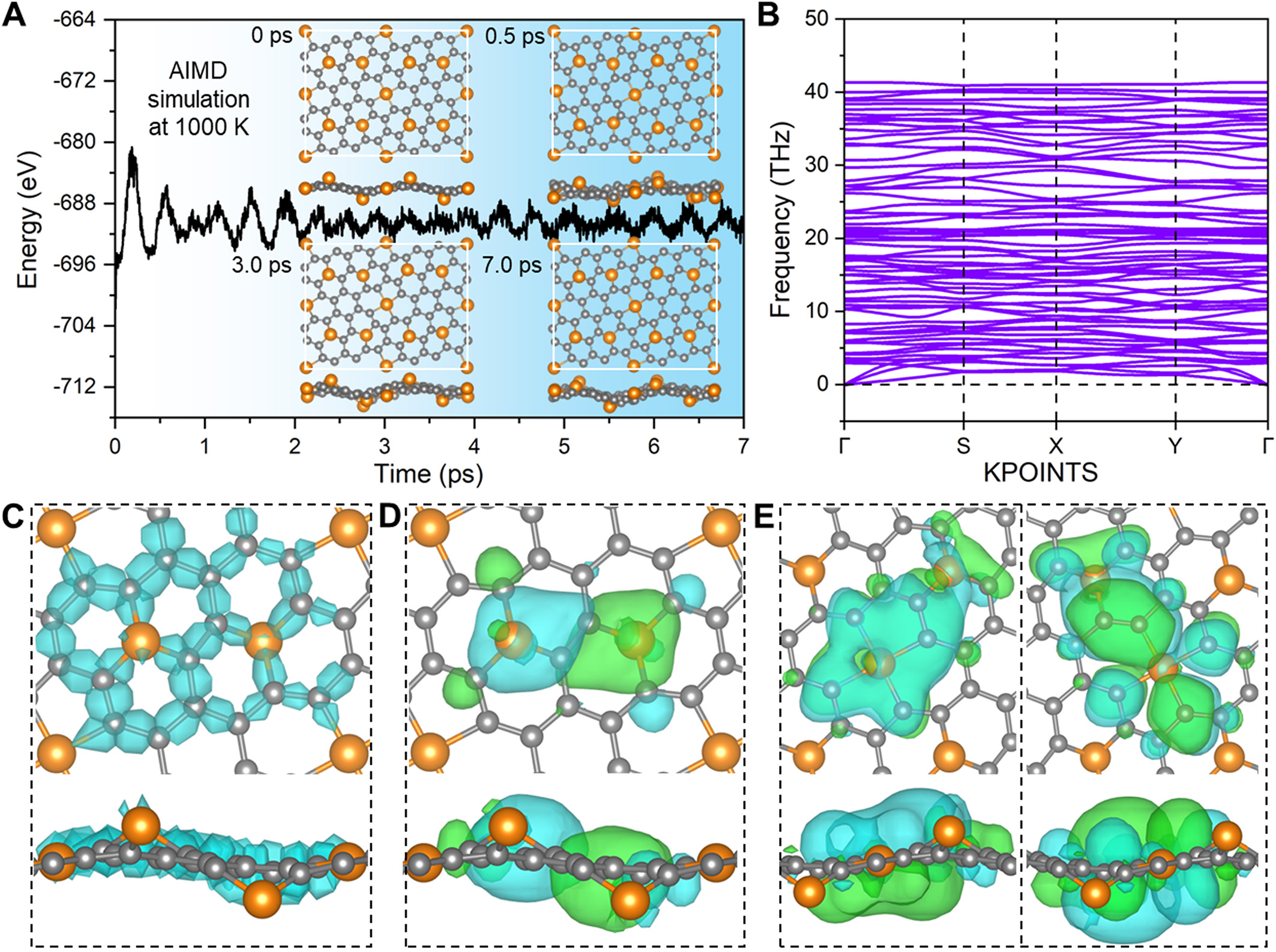

The stability of 2D materials has long been a critical challenge in materials design, primarily due to the absence of interatomic interactions along the out-of-plane direction[9]. To assess the stability of ground-state 2D-Fe3C18, we first examined its Ecoh and Erxn, the definitions of which are given in the computational details section. The calculated Ecoh of -6.78 eV/atom confirms that it is energetically preferred for Fe and C atoms to be incorporated into the 2D-Fe3C18 crystal structure rather than existing as isolated single atoms. Compared with the reported Ecoh of common 2D materials [Supplementary Figure 3], it is rational to infer that the stability of 2D-Fe3C18 should be at least comparable to graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), MoS2, silicene, and 2D-Cu2Si[30]. Additionally, the negative Erxn of -0.57 eV/atom suggests that the proposed synthesis pathway for 2D-Fe3C18 based on 6,6,12-GY is exothermic. To further evaluate its stability, we performed a spin-polarized AIMD simulation and phonon spectrum calculation. As illustrated in Figure 4A, the AIMD result at 1,000 K reveals that the structural integrity of 2D-Fe3C18 remains intact throughout the simulation lasting for 7 ps, as evidenced by the snapshots at different time intervals. Notably, the conventional FeC4@graphene and FeN4@graphene are not thermally stable at 1,000 K. As demonstrated in Supplementary Figures 4 and 5, Fe atoms would completely escape from the graphene plane in both cases. In addition, the phonon dispersion spectrum

Figure 4. Calculation results about the stability of the ground-state 2D-Fe3C18. (A) Energy variation during the ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation at 1,000 K, where the insets are the corresponding snapshots of the trajectories. (B) Phonon dispersion spectrum. (C) Thirty-two 2c σ bonds in the majority-spin channel. The minority-spin channel shares a similar bonding configuration. (D) One 8c bond in the majority-spin channel. (E) Two 9c bonds in the minority-spin channel.

Since the clustering of metal atoms is a primary factor responsible for performance degradation in traditional metal-doped graphene catalysts, we employed CI-NEB to examine the diffusion and aggregation of Fe atoms in 2D-Fe3C18. Based on the predicted crystal structure of 2D-Fe3C18, six possible diffusion paths of Fe atoms are considered in this study. The calculated initial states (IS), transition states (TS), and final states (FS) for these six diffusion paths are illustrated in Supplementary Figure 6A-F, respectively, and the corresponding energy profiles can be found in Supplementary Figure 7A-F. The first four paths

The exceptional stability of 2D-Fe3C18 can be attributed to its unique bonding characteristics. To elucidate its bonding nature, we employed the SSAdNDP method. A brief introduction to this method is given in the calculation methods section. Detailed chemical bonding analyses can be found in Supplementary Materials, where the bonding configurations are given in Supplementary Figures 8-13, and a summary of the numbers of various identified bonds is presented in Supplementary Table 1. On the one hand, the SSAdNDP reveals the presence of 32 two-center (2c) σ bonds, comprising 10 Fe-C and 22 C-C σ bonds (2c-2e bonds), in both the majority-spin and minority-spin channels of 2D-Fe3C18, as depicted in Figure 4C. These localized 2c σ bonds interconnect all atoms within the 2D network, significantly contributing to its structural stability. On the other hand, one eight-center (8c) bond (8c-1e) in the majority-spin channel and two nine-center (9c) bonds (9c-1e) in the minority-spin channel are identified, and their bonding configurations are presented in Figure 4D and E, respectively. Clearly, these delocalized multicenter bonds mediate long-range Fe-Fe interactions by bridging Fe atoms across FeC3 and FeC4 moieties via the carbon network. Notably, such long-range metal-metal interactions are absent in conventional metal-doped graphene systems[9,23]. The synergistic combination of Fe-C covalent bonding and extended Fe-Fe interactions enhances the remarkable stability of 2D-Fe3C18, thereby distinguishing it from previously reported 2D materials[7,23,31]. Additionally, it should be noted that when the functional material is applied to electrocatalysis, the stability under real electrocatalytic conditions also warrants consideration. However, actual electrocatalytic systems are highly complex, typically comprising the catalyst surface, the solution (including solvent and solutes), and the electrode potential, which makes theoretical investigations of catalyst stability during electrochemical processes extremely challenging. To our knowledge, there are currently two approaches that can provide insights into the stability of the catalyst under electrochemical conditions[9]. The first is conducting an AIMD simulation replicating a real electrocatalytic system. The second is constructing an electrode potential-pH diagram, which is also known as the Pourbaix diagram. Limited by the high complexity of electrocatalytic systems and the trade-offs between model fidelity and computational speed, these two approaches are still in rapid development. Most studies have yet to provide a comprehensive understanding of catalyst stability under electrocatalytic conditions[8,11,12,23]. Thus, the stability of 2D-Fe3C18 under electrocatalytic operation remains to be investigated.

Electronic properties of ground-state 2D-Fe3C18

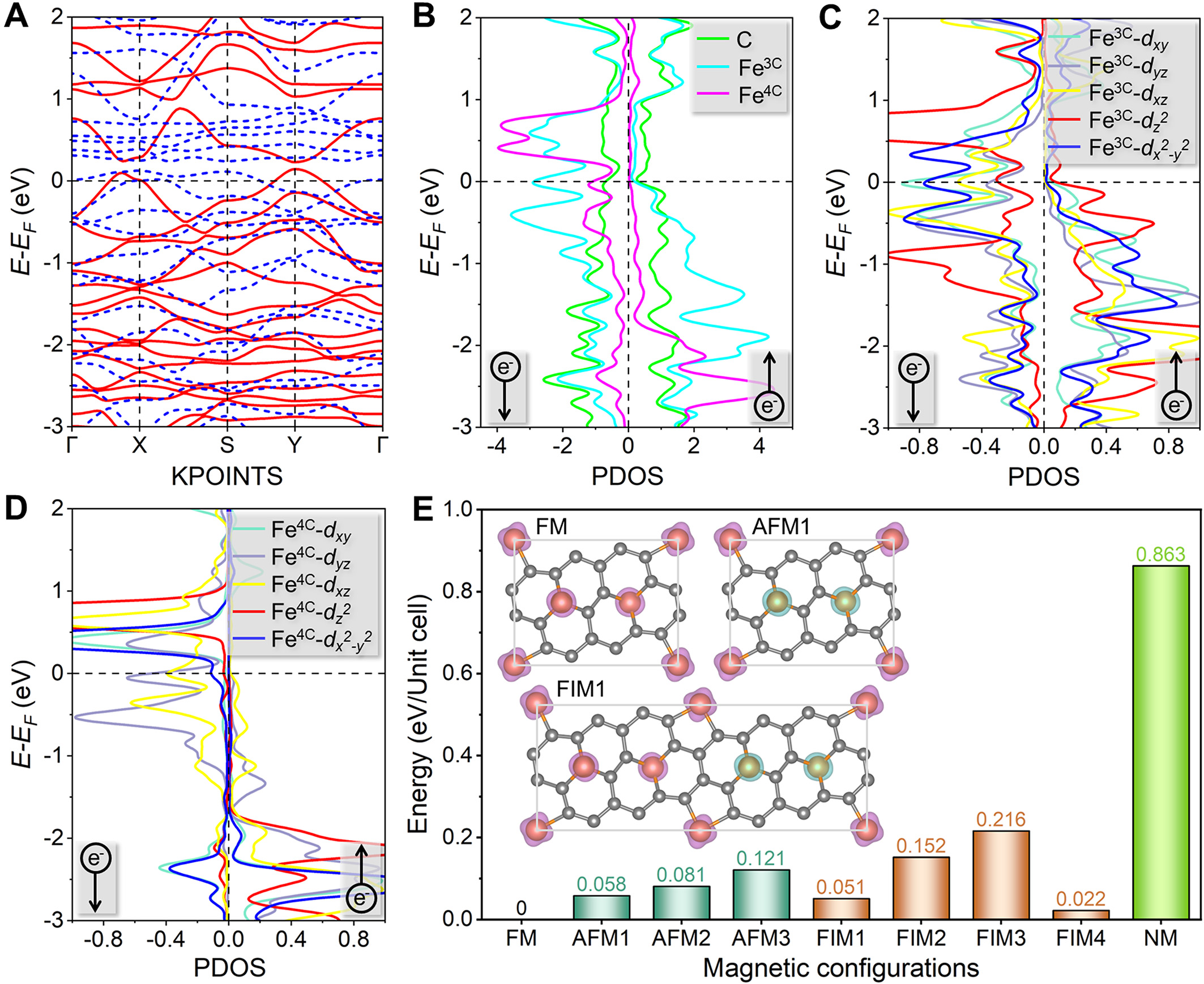

We next investigated the electronic properties of ground-state two-sided 2D-Fe3C18. As shown in Figure 5A, the calculated band structure reveals that 2D-Fe3C18 exhibits both metallic and magnetic characteristics. Since two types of Fe atoms (Fe3C and Fe4C) are included in the crystal 2D-Fe3C18, the projected density of states (PDOS) weighted band structure is plotted to understand the roles of Fe3C and Fe4C in its electronic structure. According to Supplementary Figure 14, it is demonstrated that near the EF, Fe3C atoms contribute substantially to electronic states in both spin channels, while Fe4C atoms contribute predominantly to the minority-spin channel. Based on the PDOS plots presented in Figure 5B-D and Supplementary Figure 15, further insights into the origins of the electronic states near the EF in 2D-Fe3C18 can be obtained. Clearly, in the majority-spin channel, the states derived from the pz orbitals of C atoms dominate near the EF

Figure 5. Calculation results about the electronic properties of the ground-state 2D-Fe3C18. (A) Band structure, where the red solid (blue dashed) line represents the majority-spin (minority-spin) channel. (B-D) Projected density of states (PDOS) plots. (E) Energy comparison of nine possible magnetic configurations, where the energy of the FM configuration is set to 0 eV/Unit cell. The insets show the FM, AFM1, and FIM1 configurations. Other magnetic coupling configurations are shown in the Supplementary Materials. The magenta (cyan) isosurface represents the spin-up (spin-down) density. The spin differential density (ρ↑-↓) is calculated as ρ↑-↓ = ρ↑ - ρ↓, where ρ↑ (ρ↓) denotes the spin-up (spin-down) density.

To determine the ground-state magnetic coupling configuration of 2D-Fe3C18, we systematically evaluated nine distinct magnetic configurations: ferromagnetic (FM), three antiferromagnetic (AFM1-AFM3), four ferrimagnetic (FIM1-FIM4), and non-magnetic (NM) states. These configurations are illustrated in

Bifunctional catalytic activity of ground-state 2D-Fe3C18

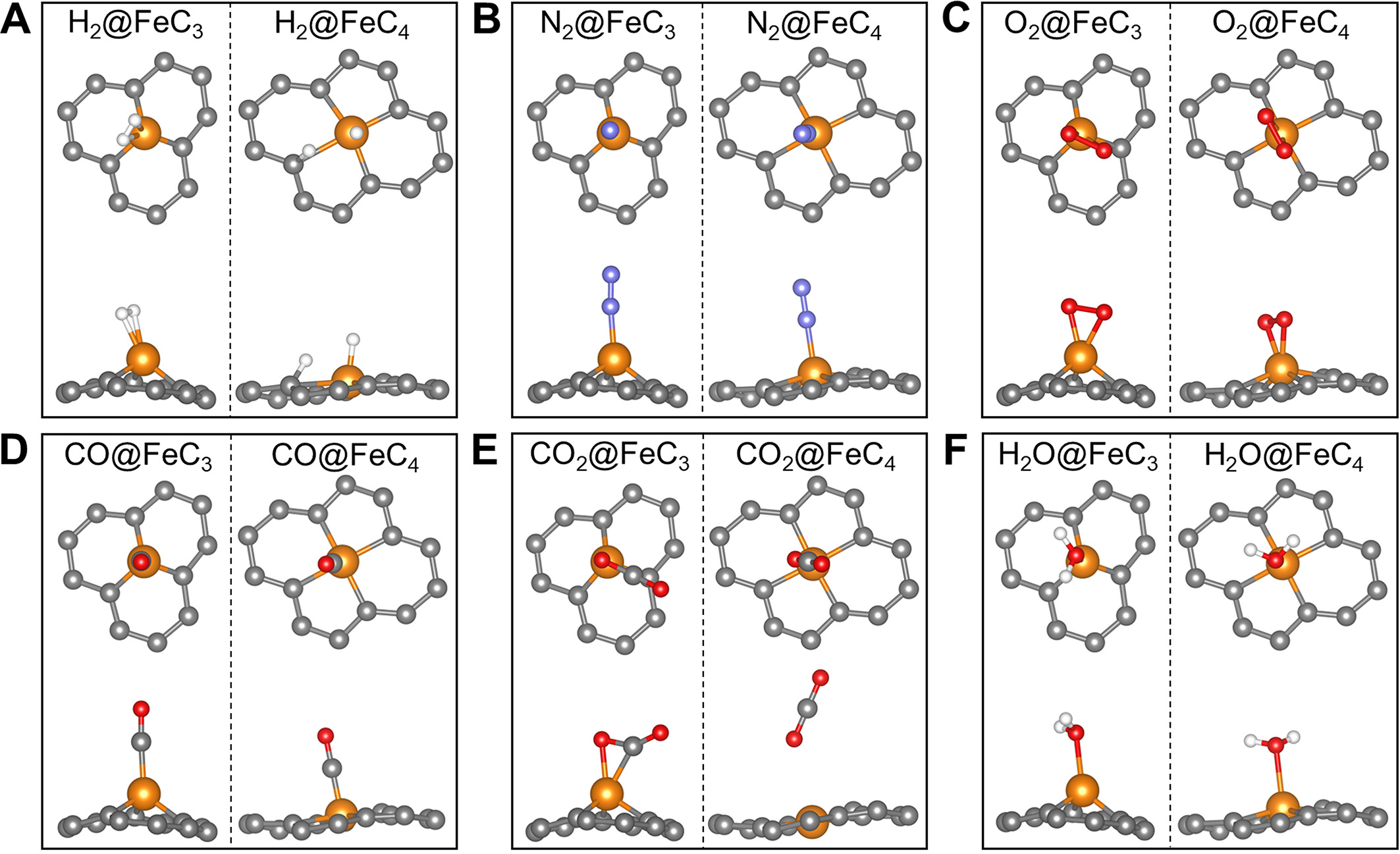

Before discussing the catalytic performances of the two-sided 2D-Fe3C18, we simultaneously examined the adsorption differences of common small molecules (including H2, N2, O2, CO, CO2, and H2O) on both FeC3 and FeC4 moieties. The most stable adsorption configurations of the aforementioned molecules are given in Figure 6A-F, and the corresponding adsorptions are summarized in Table 1. Comparative analysis reveals that the Fe3C site exhibits stronger binding with all adsorbates except H2. Notably, H2 undergoes dissociative adsorption exclusively on the Fe4C site. A particularly interesting observation concerns CO2 adsorption. While CO2 shows only weak physisorption on the Fe4C site (Eads = -0.015 eV), it undergoes significant chemisorption on the Fe3C site (Eads = -0.383 eV). These distinct adsorption behaviors suggest divergent catalytic functionalities for the two sites. The FeC3 moiety demonstrates potential as both a thermal catalyst for CO oxidation reaction (COOR) and water-gas shift reaction (WGSR) and an electrocatalyst for nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR), ORR/OER, and CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR). Meanwhile, the Fe4C site may serve as an active center for thermal COOR and WGSR, along with electrochemical ORR/OER. In this study, we employed electrochemical ORR/OER to evaluate the bifunctional electrocatalytic performance of 2D-Fe3C18.

Figure 6. Adsorption configurations of common molecules on FeC3 and FeC4 moieties, respectively. (A) H2, (B) N2, (C) O2, (D) CO,

Summary of the adsorbate molecules on FeC3 and FeC4 moieties

| Species | Eads (eV) | Most stable configuration | ||

| FeC3 | FeC4 | FeC3 | FeC4 | |

| H2 | -0.343 | -0.404 | Side-on | Side-on |

| N2 | -0.792 | -0.449 | Head-on | Head-on |

| O2 | -1.828 | -1.452 | Side-on | Side-on |

| CO | -1.416 | -1.348 | Head-on | Head-on |

| CO2 | -0.383 | -0.015 | Side-on | Head-on |

| H2O | -0.753 | -0.409 | Side-on | Side-on |

Both ORR and OER are fundamental processes for energy storage and conversion[61]. The electrochemical ORR serves as the critical cathode process in fuel cells and metal-air batteries, yet its inherently sluggish kinetics significantly constrain the overall energy conversion efficiency of these devices[23]. In an acidic medium, ORR can proceed via either a two-electron mechanism (yielding H2O2) or a four-electron mechanism (producing H2O)[7]. However, we exclusively consider the four-electron mechanism in this study, as adsorbed H2O2 spontaneously dissociates into two OH groups on both Fe3C and Fe4C sites. The three potential four-electron pathways are given below.

(1) O2 dissociation pathway: * + O2 → *O2 → *O + *O → *OH + *O → *O + H2O → *OH + H2O → * + 2H2O

(2) OOH dissociation pathway: * + O2 → *O2 → *OOH → *O + H2O → *OH + H2O → * + 2H2O

(3) HOOH dissociation pathway: * + O2 → *O2 → *OOH → *OH + *OH → *OH + H2O → * + 2H2O.

Our calculations reveal that O2 undergoes chemical adsorption on both FeC3 and FeC4 moieties without dissociation [Figure 6C], thereby precluding the O2 dissociation pathway as a viable mechanism. Under alkaline conditions[8], ORR typically proceeds through the following four-electron pathway: * + O2 + 2H2O → *O2 + 2H2O → *OOH + OH- + H2O → *O + 2OH- + H2O → *OH + 3OH- → * + 4OH-.

The electrochemical OER represents a critical anodic process in both proton-exchange membrane water electrolyzers (PEMWEs) and anion-exchange membrane water electrolyzers (AEMWEs), serving as the key oxidative half-reaction in water-splitting technologies[62,63]. The reaction mechanisms of OER depend on the electrolyte environment[64]: * + 2H2O → *H2O + H2O → *OH + H2O → *O + H2O → *OOH → * + O2 (in an acidic medium) and * + 4OH- → *OH + 3OH- → *O + H2O + 2OH- → *OOH + H2O + OH-→ * + O2 + 2H2O (in an alkaline medium).

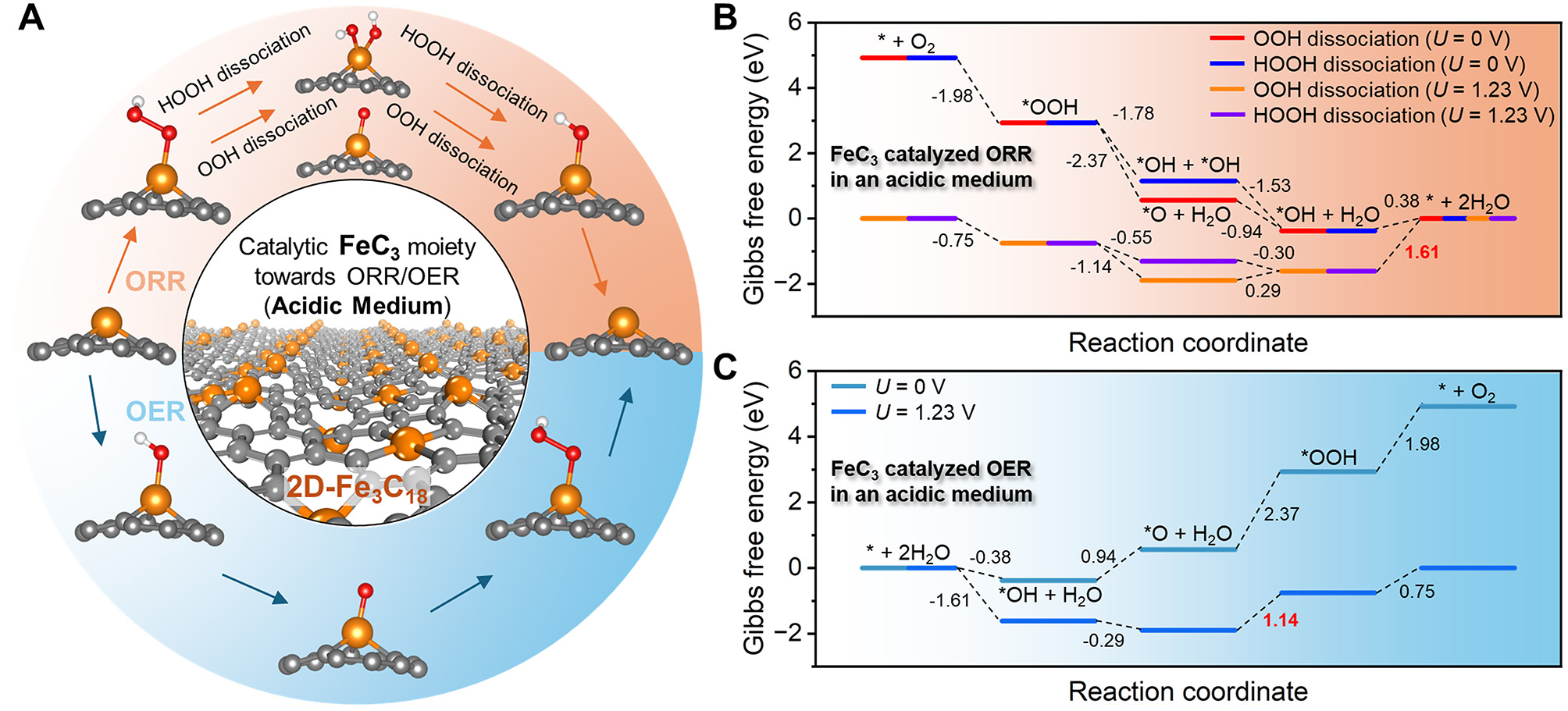

We first explored the electrocatalytic performance of the FeC3 moiety towards ORR and OER in an acidic medium. The reaction pathways are illustrated in Figure 7A, where the most stable adsorption configurations of O, OH, OOH, and 2OH can be found. The thermodynamic corrections required for Gibbs free energy calculations, including zero-point energy (ZPE) and entropy (TS), for the reactants, intermediate species, and products in the ORR and OER are provided in Supplementary Table 2. The adsorption free energies (ΔG*ads) and adsorption energies (Eads) of oxygen-containing intermediates on both FeC3 and FeC4 moieties are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Figure 7B shows the Gibbs free energy diagram of ORR catalyzed by the FeC3 moiety at U = 0 V and U = 1.23 V. Clearly, the final step, *OH + H+ + e- → * + H2O, emerges as the potential determining step (PDS) in both the OOH and HOOH dissociation pathways, and the overpotential, η, is estimated to be 1.61 V. The OER results catalyzed by the FeC3 moiety at U = 0 V and U = 1.23 V are displayed in Figure 7C. The corresponding PDS is the oxidation of *O to *OOH with the η of 1.14 V.

Figure 7. Catalytic performance of the FeC3 moiety towards oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) in an acidic medium. (A) Reaction pathways of ORR and OER catalyzed by the FeC3 moiety, where the most stable adsorption configurations of O, OH, OOH, and 2OH are given. Gibbs free energy diagrams of (B) ORR and (C) OER.

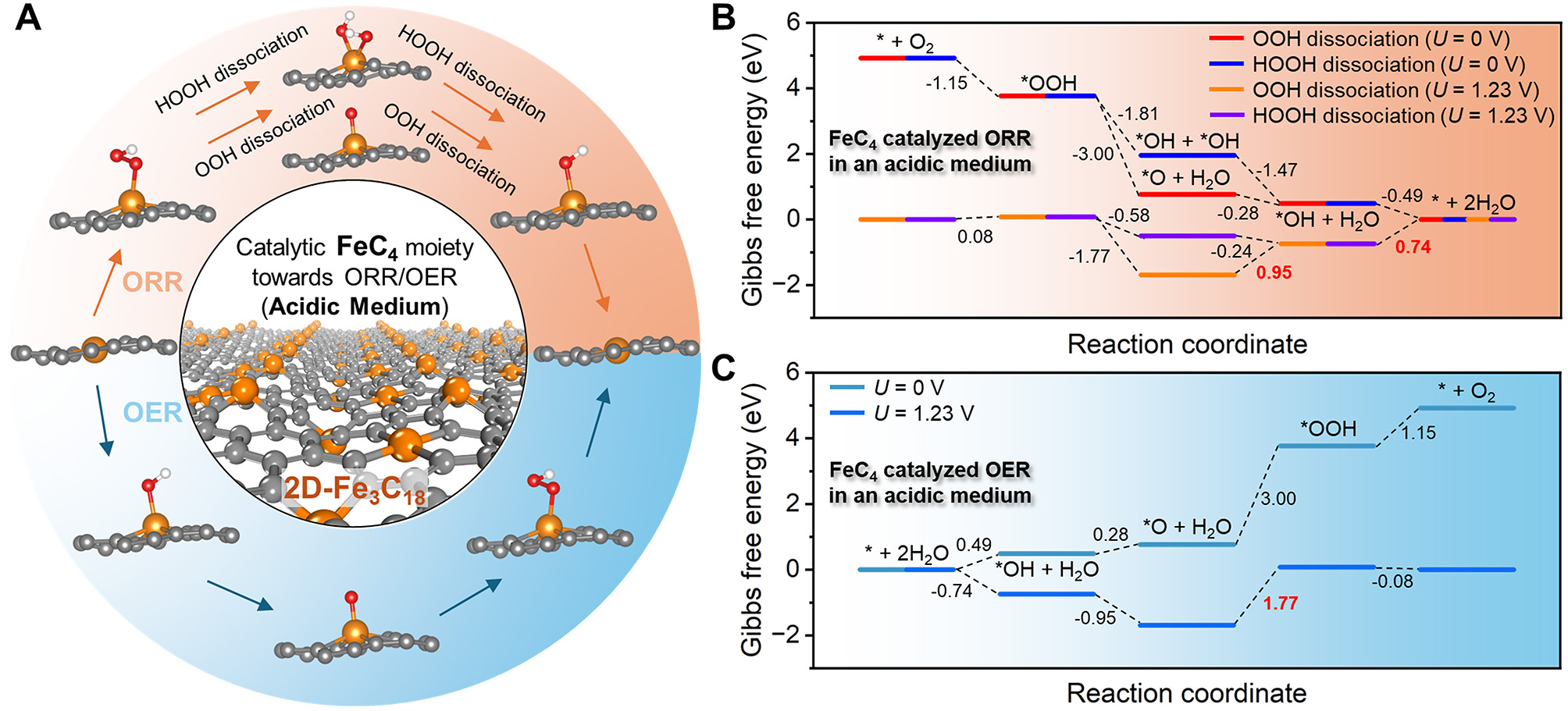

The reaction pathways of ORR and OER catalyzed by the FeC4 moiety in an acidic medium are depicted in Figure 8A. The calculated Gibbs free energy diagram of ORR is plotted in Figure 8B. Obviously, the HOOH dissociation pathway, where the *OH-to-H2O conversion is the PDS with the η of 0.74 V, is energetically preferred; while the PDS is found to be *O-to-*OH conversion and the η is 0.95 V in the OOH dissociation pathway. Regarding the OER process depicted in Figure 8C, the η reaches as high as 1.77 V during the conversion of *O-to-*OOH.

Figure 8. Catalytic performance of the FeC4 moiety towards oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) in an acidic medium. (A) Reaction pathways of ORR and OER catalyzed by the FeC4 moiety, where the most stable adsorption configurations of O, OH, OOH, and 2OH are given. Gibbs free energy diagrams of (B) ORR and (C) OER.

Table 2 summarizes the calculated results of ORR and OER catalyzed by the FeC3 and FeC4 moieties under acidic conditions. For ORR, the FeC4 moiety, with a lower η of 0.74 V, exhibits significantly superior electrocatalytic activity via the HOOH dissociation pathway, compared with the FeC3 moiety (η = 1.61 V); its ORR performance is comparable to the extensively studied FeN4@graphene system, which demonstrates an η of 0.81 V[23]. The different ORR activities of the FeC3 and FeC4 moieties can be attributed to variations in the adsorption strengths of O and OH species, which are widely recognized as critical descriptors for electrocatalytic ORR performance[8,11,23]. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, both ΔG*ads and Eads of O and OH are lower on the FeC3 moiety compared to those on the FeC4 moiety. These results indicates that O and OH are more strongly adsorbed on the Fe3C site, with a notably larger difference observed for the OH species. Consequently, the OH adsorbed on the FeC3 moiety would be more resistant to protonation, ultimately resulting in a higher overpotential relative to the FeC4 moiety. For OER, the FeC3 moiety shows better electrocatalytic activity (η = 1.14 V), compared with the FeC4 moiety (η = 1.77 V); its OER is comparable to that of the reported FeCoN3@graphene electrocatalyst[65]. The observed electrocatalytic behaviors of FeC3 and FeC4 moieties towards OER can be rationalized through the strong adsorption of O species[66-68]. Additionally, the electrocatalytic ORR and OER results under alkaline conditions are also presented in Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Figures 17 and 18 for FeC3 and FeC4 moieties, respectively). The key results are also summarized in Table 2. Based on these findings, the similar conclusion can be obtained. Therefore, due to the presence of FeC3 and FeC4 moieties within the predicted 2D-Fe3C18 lattice, this material exhibits potential as a bifunctional catalyst.

Electrocatalytic performance of the FeC3 and FeC4 moieties towards oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER)

| Reaction | Medium | Elementary steps | FeC3 moiety | FeC4 moiety | |||||

| ΔG (eV) | UL (V) | η (V) | ΔG (eV) | UL (V) | η (V) | ||||

| ORR | Acidic | OOH dissociation | Step 1: * + O2 + H+ + e- → *OOH | -1.98 | 0.38 | 1.61 | -1.15 | -0.28 | 0.95 |

| Step 2: *OOH + H+ + e- → *O + H2O | -2.37 | -3.00 | |||||||

| Step 3: *O + H2O + H+ + e- → *OH + H2O | -0.94 | -0.28 | |||||||

| Step 4: *OH + H2O + H+ + e- → * + 2H2O | 0.38 | -0.49 | |||||||

| HOOH dissociation | Step 1: * + O2 + H+ + e- → *OOH | -1.98 | 0.38 | 1.61 | -1.15 | -0.49 | 0.74 | ||

| Step 2: *OOH + H+ + e- → 2*OH | -1.78 | -1.81 | |||||||

| Step 3: 2*OH + H+ + e- → *OH + H2O | -1.53 | -1.47 | |||||||

| Step 4: *OH + H2O + H+ + e- → * + 2H2O | 0.38 | -0.49 | |||||||

| Alkaline | - | Step 1: * + O2 + H2O + e- → *OOH + OH- | -1.16 | 1.20 | 1.61 | -0.33 | 0.55 | 0.95 | |

| Step 2: *OOH + e- → *O + OH- | -1.55 | -2.17 | |||||||

| Step 3: *O + H2O + e- → *OH + OH- | -0.12 | 0.55 | |||||||

| Step 4: *OH + e- → * + OH- | 1.20 | 0.34 | |||||||

| OER | Acidic | - | Step 1: * + 2H2O → *OH + H2O + H+ + e- | -0.38 | 2.37 | 1.14 | 0.49 | 3.00 | 1.77 |

| Step 2: *OH + H2O → *O + H2O + H+ + e- | 0.94 | 0.28 | |||||||

| Step 3: *O + H2O → *OOH + H+ + e- | 2.37 | 3.00 | |||||||

| Step 4: *OOH → * + O2 + H+ + e- | 1.98 | 1.15 | |||||||

| Alkaline | - | Step 1: * + 4OH- → *OH + 3OH- + e- | -1.20 | 1.55 | 1.14 | -0.34 | 2.17 | 1.77 | |

| Step 2: *OH + 3OH- → *O + H2O + 2OH- + e- | 0.12 | -0.55 | |||||||

| Step 3: *O + H2O + 2OH- → *OOH + H2O + OH- + e- | 1.55 | 2.17 | |||||||

| Step 4: *OOH + H2O + OH- → * + 2H2O + O2 + e- | 1.16 | 0.33 | |||||||

In order to clarify the features of the bifunctional electrocatalysis exhibited by 2D-Fe3C18, its ORR and OER performances are compared with that reported for common 2D single- and dual-atom electrocatalysts. As shown in Supplementary Table 4, the ORR performance of 2D-Fe3C18 is comparable to or exceeds that of the majority of reported electrocatalysts. As for OER, the performance is acceptable but leaves substantial room for optimization. If compared with traditional noble-metal or noble-metal oxide catalysts such as Pt[69], Pt/C[70], IrO2[71], and RuO2[72], the electrocatalytic performance of 2D-Fe3C18 remains to be improved. Based on the above facts, future efforts should be directed towards the following aspects. First, by replacing Fe atoms with other metal atoms (M), 2D-M3C18 with higher performance is expected to be obtained. Second, both surface and interface engineering techniques can be considered, such as loading 2D-Fe3C18 onto a substrate or applying stress to 2D-Fe3C18, to explore approaches for further enhancing the performance of 2D-Fe3C18. Third, collaboration with experimental researchers should be conducted to explore the technical approaches for synthesizing 2D-Fe3C18. Overall, we hope that more functional 2D metal-carbon crystals could be designed, synthesized, and even applied in some significant fields following this work.

CONCLUSIONS

With state-of-the-art first-principles calculations, we predict in this work a new type of atomically thin 2D-Fe3C18 crystal with both FeC3 and FeC4 moieties included in one unit cell. By adopting 6,6,12-GY as the substrate, we suggest that the 2D-Fe3C18 crystal can be formed by a self-organizing process after anchoring Fe atoms in its hollow sites. The AIMD and phonon spectrum together indicate the thermodynamic stability of the two-sided 2D-Fe3C18. The natural bond analysis reveals that the high stability can be attributed to the long-range Fe-Fe interactions originating from its unique lattice structure, together with the localized Fe-C interactions. Notably, the highly stable 2D-Fe3C18 boasts a high Fe loading of 43.7 wt%. Owing to the different bonding conditions of Fe atoms in FeC3 and FeC4 moieties, the proposed 2D-Fe3C18 presents bifunctional electrocatalytic performance towards ORR and OER. The high stability and large metal loading ratio of the designed crystal together distinguish this study from the traditional metal-carbon hybrid nonperiodic catalysts. Following this work, more functional 2D metal-carbon crystals are expected to be designed.

ECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

Computations were performed using the High Performance Computing (HPC) facilities at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the National Supercomputing Centre (NSCC) in Singapore.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design of the work: Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.

Data acquisition and analysis: Zhang, Y.; Yam, K. M.; Yang, J.; Guo, N.

Data interpretation: Zhang, Y.; Yam, K. M.; Wang, H.

Manuscript writing and revising: Zhang, Y.; Yam, K. M.; Zhang, C.; Deng, H.

Supervision: Zhang, C.; Deng, H.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data supporting the findings of this study are available within this Article and its

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52450164 and 52505488), the NUS Academic Research Fund (A-8002944-00-00), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number 2025M771393, the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20250604144359081), the Key Research Program of the Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2024ZDZX1022), and the Shenzhen Engineering Research Center for Semiconductor-specific Equipment (XMHT20230111003).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

©The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Mitchell, S.; Qin, R.; Zheng, N.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Nanoscale engineering of catalytic materials for sustainable technologies. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 129-39.

2. Taseska, T.; Yu, W.; Wilsey, M. K.; et al. Analysis of the scale of global human needs and opportunities for sustainable catalytic technologies. Top. Catal. 2023, 66, 338-74.

3. Wei, D.; Shi, X.; Qu, R.; Junge, K.; Junge, H.; Beller, M. Toward a hydrogen economy: development of heterogeneous catalysts for chemical hydrogen storage and release reactions. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2022, 7, 3734-52.

4. Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Mao, S.; et al. Decoupling the electronic and geometric effects of Pt catalysts in selective hydrogenation reaction. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3561.

5. Zhang, H.; Sun, P.; Fei, X.; et al. Unusual facet and co-catalyst effects in TiO2-based photocatalytic coupling of methane. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4453.

6. Qiao, B.; Wang, A.; Yang, X.; et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 634-41.

7. Zhuo, H. Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, J. X.; Yu, Q.; Xiao, H.; Li, J. Theoretical understandings of graphene-based metal single-atom catalysts: stability and catalytic performance. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12315-41.

8. Xu, H.; Cheng, D.; Cao, D.; Zeng, X. C. Revisiting the universal principle for the rational design of single-atom electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 207-18.

9. Zhang, Y.; Yam, K.; Wang, H.; Guo, N.; Zhang, C. Recent progresses in two-dimensional carbon-metal composites for catalysis applications. WIREs. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 15, e70014.

10. Torres-Pinto, A.; Silva, C. G.; Faria, J. L.; Silva, A. M. T. Advances on graphyne-family members for superior photocatalytic behavior. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2003900.

11. Fei, H.; Dong, J.; Feng, Y.; et al. General synthesis and definitive structural identification of MN4C4 single-atom catalysts with tunable electrocatalytic activities. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 63-72.

12. Kattel, S.; Wang, G. Reaction pathway for oxygen reduction on FeN4 embedded graphene. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 452-6.

13. Fang, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Wan, W.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X. Synergy of dual-atom catalysts deviated from the scaling relationship for oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4449.

14. Zhao, T.; Chen, K.; Xu, X.; et al. Homonuclear dual-atom catalysts embedded on N-doped graphene for highly efficient nitrate reduction to ammonia: from theoretical prediction to experimental validation. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2023, 339, 123156.

15. Yam, K.; Guo, N.; Jiang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, C. Graphene-based heterogeneous catalysis: role of graphene. Catalysts 2020, 10, 53.

16. Zhou, M.; Zhang, A.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y. P. Greatly enhanced adsorption and catalytic activity of Au and Pt clusters on defective graphene. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 194704.

17. Lu, J.; Huang, K.; Lee, H.; et al. Reverse oriented dual-interface built-in electric fields of robust Pd1Mo1Ta2Oα bifunctional electrocatalysis for zinc-air batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2418211.

18. Pei, C.; Li, N.; Han, X.; et al. Edge-specific confined construction of an interfacial Re-O-Co bridge for enhanced trifunctional electrocatalysis. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 17674-85.

19. Wang, Y.; Lai, W.; Tao, H.; et al. CO2 electroreduction to multicarbon products over Cu2O@mesoporous SiO2 confined catalyst: relevance of the shell thickness. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2025, 15, 2404606.

20. Mahdavi-shakib, A.; Whittaker, T. N.; Yun, T. Y.; et al. The role of surface hydroxyls in the entropy-driven adsorption and spillover of H2 on Au/TiO2 catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 710-9.

21. Zhang, C.; Sha, J.; Fei, H.; et al. Single-atomic ruthenium catalytic sites on nitrogen-doped graphene for oxygen reduction reaction in acidic medium. ACS. Nano. 2017, 11, 6930-41.

22. Xiong, Y.; Dong, J.; Huang, Z. Q.; et al. Single-atom Rh/N-doped carbon electrocatalyst for formic acid oxidation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 390-7.

23. Yan, M.; Dai, Z.; Chen, S.; et al. Single-iron supported on defective graphene as efficient catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2020, 124, 13283-90.

24. Yang, W.; Xu, S.; Ma, K.; et al. Geometric structures, electronic characteristics, stabilities, catalytic activities, and descriptors of graphene-based single-atom catalysts. Nano. Mater. Sci. 2020, 2, 120-31.

25. Zhou, Y.; Gao, G.; Li, Y.; Chu, W.; Wang, L. W. Transition-metal single atoms in nitrogen-doped graphenes as efficient active centers for water splitting: a theoretical study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 3024-32.

26. Liu, T.; Xu, T.; Li, T.; Jing, Y. Selective CO2 reduction over γ-graphyne supported single-atom catalysts: crucial role of strain regulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 24133-40.

27. Kong, H.; Dong, N.; Zhang, W.; Jia, M.; Song, W. First-principles study of transition metal supported on graphyne as single atom electrocatalysts for nitric oxide reduction reaction. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2023, 1226, 114225.

28. Li, H.; Lim, J. H.; Lv, Y.; Li, N.; Kang, B.; Lee, J. Y. Graphynes and graphdiynes for energy storage and catalytic utilization: theoretical insights into recent advances. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4795-854.

29. Ren, M.; Guo, X.; Zhang, S.; Huang, S. Design of graphdiyne and holey graphyne-based single atom catalysts for CO2 reduction with interpretable machine learning. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213543.

30. Li, S.; Yam, K.; Guo, N.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C. Highly stable two-dimensional metal-carbon monolayer with interpenetrating honeycomb structures. NPJ. 2D. Mater. Appl. 2021, 5, 235.

31. Yam, K. M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, N.; Jiang, Z.; Deng, H.; Zhang, C. Two-dimensional graphitic metal carbides: structure, stability and electronic properties. Nanotechnology 2023, 34, 465706.

32. Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yam, K. M.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C. Layer-dependent electronic and magnetic properties of two-dimensional graphitic molybdenum carbide. Mater. Today. Electron. 2023, 6, 100073.

33. Perkgöz, N. K.; Sevik, C. Vibrational and thermodynamic properties of α-, β-, γ-, and 6, 6, 12-graphyne structures. Nanotechnology 2014, 25, 185701.

34. Gong, Y.; Shen, L.; Kang, Z.; et al. Progress in energy-related graphyne-based materials: advanced synthesis, functional mechanisms and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 21408-33.

35. Baughman, R. H.; Eckhardt, H.; Kertesz, M. Structure-property predictions for new planar forms of carbon: layered phases containing sp2 and sp atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 87, 6687-99.

36. Kilde, M. D.; Murray, A. H.; Andersen, C. L.; et al. Synthesis of radiaannulene oligomers to model the elusive carbon allotrope 6,6,12-graphyne. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3714.

37. Malko, D.; Neiss, C.; Viñes, F.; Görling, A. Competition for graphene: graphynes with direction-dependent Dirac cones. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 086804.

38. Wu, G.; Li, J.; Tang, C.; et al. A comparative investigation of metal (Li, Ca and Sc)-decorated 6,6,12-graphyne monolayers and 6,6,12-graphyne nanotubes for hydrogen storage. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 498, 143763.

39. Kang, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, J. Graphyne and its family: recent theoretical advances. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 2692-706.

40. Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter. 1993, 47, 558-61.

41. Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter. 1996, 54, 11169-86.

42. Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter. 1994, 50, 17953-79.

43. Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865-8.

44. Monkhorst, H. J.; Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B. 1976, 13, 5188-92.

45. Togo, A.; Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 2015, 108, 1-5.

46. Henkelman, G.; Uberuaga, B. P.; Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9901-4.

47. Dunnington, B. D.; Schmidt, J. R. Generalization of natural bond orbital analysis to periodic systems: applications to solids and surfaces via plane-wave density functional theory. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2012, 8, 1902-11.

48. Galeev, T. R.; Dunnington, B. D.; Schmidt, J. R.; Boldyrev, A. I. Solid state adaptive natural density partitioning: a tool for deciphering multi-center bonding in periodic systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 5022-9.

49. Yang, L. M.; Bačić, V.; Popov, I. A.; et al. Two-dimensional Cu2Si monolayer with planar hexacoordinate copper and silicon bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2757-62.

50. Pritchard, B. P.; Altarawy, D.; Didier, B.; Gibson, T. D.; Windus, T. L. New basis set exchange: an open, up-to-date resource for the molecular sciences community. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4814-20.

51. Sha, Y.; Yu, T. H.; Merinov, B. V.; Shirvanian, P.; Goddard, W. A. Oxygen hydration mechanism for the oxygen reduction reaction at Pt and Pd fuel cell catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 572-6.

52. Wang, V.; Xu, N.; Liu, J.; Tang, G.; Geng, W. VASPKIT: a user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 267, 108033.

53. Nørskov, J. K.; Rossmeisl, J.; Logadottir, A.; et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004, 108, 17886-92.

54. Nørskov, J. K.; Bligaard, T.; Logadottir, A.; et al. Trends in the exchange current for hydrogen evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, J23.

55. Talib, S. H.; Lu, Z.; Yu, X.; et al. Theoretical inspection of M1/PMA single-atom electrocatalyst: ultra-high performance for water splitting (HER/OER) and oxygen reduction reactions (OER). ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 8929-41.

56. Huang, H.; Duan, W.; Liu, Z. The existence/absence of Dirac cones in graphynes. New. J. Phys. 2013, 15, 023004.

57. Ding, H.; Bai, H.; Huang, Y. Electronic properties and carrier mobilities of 6,6,12-graphyne nanoribbons. AIP. Adv. 2015, 5, 077153.

58. Shi, H.; Xia, M.; Jia, L.; Hou, B.; Wang, Q.; Li, D. First-principles study on the adsorption and diffusion properties of non-noble (Fe, Co, Ni and Cu) and noble (Ru, Rh, Pt and Pd) metal single atom on graphyne. Chem. Phys. 2020, 536, 110783.

59. Gan, Y.; Sun, L.; Banhart, F. One- and two-dimensional diffusion of metal atoms in graphene. Small 2008, 4, 587-91.

60. Wu, P.; Du, P.; Zhang, H.; Cai, C. Graphyne-supported single Fe atom catalysts for CO oxidation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 1441-9.

61. Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; Peng, Y.; Jung, C.; Fisher, A.; Wang, X. Design of efficient bifunctional oxygen reduction/evolution electrocatalyst: recent advances and perspectives. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2017, 7, 1700544.

62. She, L.; Zhao, G.; Ma, T.; Chen, J.; Sun, W.; Pan, H. On the durability of iridium-based electrocatalysts toward the oxygen evolution reaction under acid environment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2108465.

63. Jiao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Davey, K.; Qiao, S. Activity origin and catalyst design principles for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution on heteroatom-doped graphene. Nat. Energy. 2016, 1, 16130.

64. Liang, Q.; Brocks, G.; Bieberle-Hütter, A. Oxygen evolution reaction (OER) mechanism under alkaline and acidic conditions. J. Phys. Energy. 2021, 3, 026001.

65. Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; et al. Itinerant ferromagnetic half metallic cobalt-iron couples: promising bifunctional electrocatalysts for ORR and OER. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 27175-85.

66. Zhang, J.; Yang, H. B.; Zhou, D.; Liu, B. Adsorption energy in oxygen electrocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 17028-72.

67. Zhang, K.; Zou, R. Advanced transition metal-based OER electrocatalysts: current status, opportunities, and challenges. Small 2021, 17, e2100129.

68. Man, I. C.; Su, H.; Calle-Vallejo, F.; et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 1159-65.

69. Lucchetti, L. E. B.; de, Almeida. J. M.; Siahrostami, S. Revolutionizing ORR catalyst design through computational methodologies and materials informatics. EES. Catal. 2024, 2, 1037-58.

70. Liu, J.; Jiao, M.; Mei, B.; et al. Carbon-supported divacancy-anchored platinum single-atom electrocatalysts with superhigh Pt utilization for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1163-7.

71. Zhao, S.; Liu, T.; Dai, Y.; et al. Pt/C as a bifunctional ORR/iodide oxidation reaction (IOR) catalyst for Zn-air batteries with unprecedentedly high energy efficiency of 76.5%. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2023, 320, 121992.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].