Microstructural engineering for temperature-stable piezoresponse in KNN-based lead-free piezoceramics: a comprehensive review

Abstract

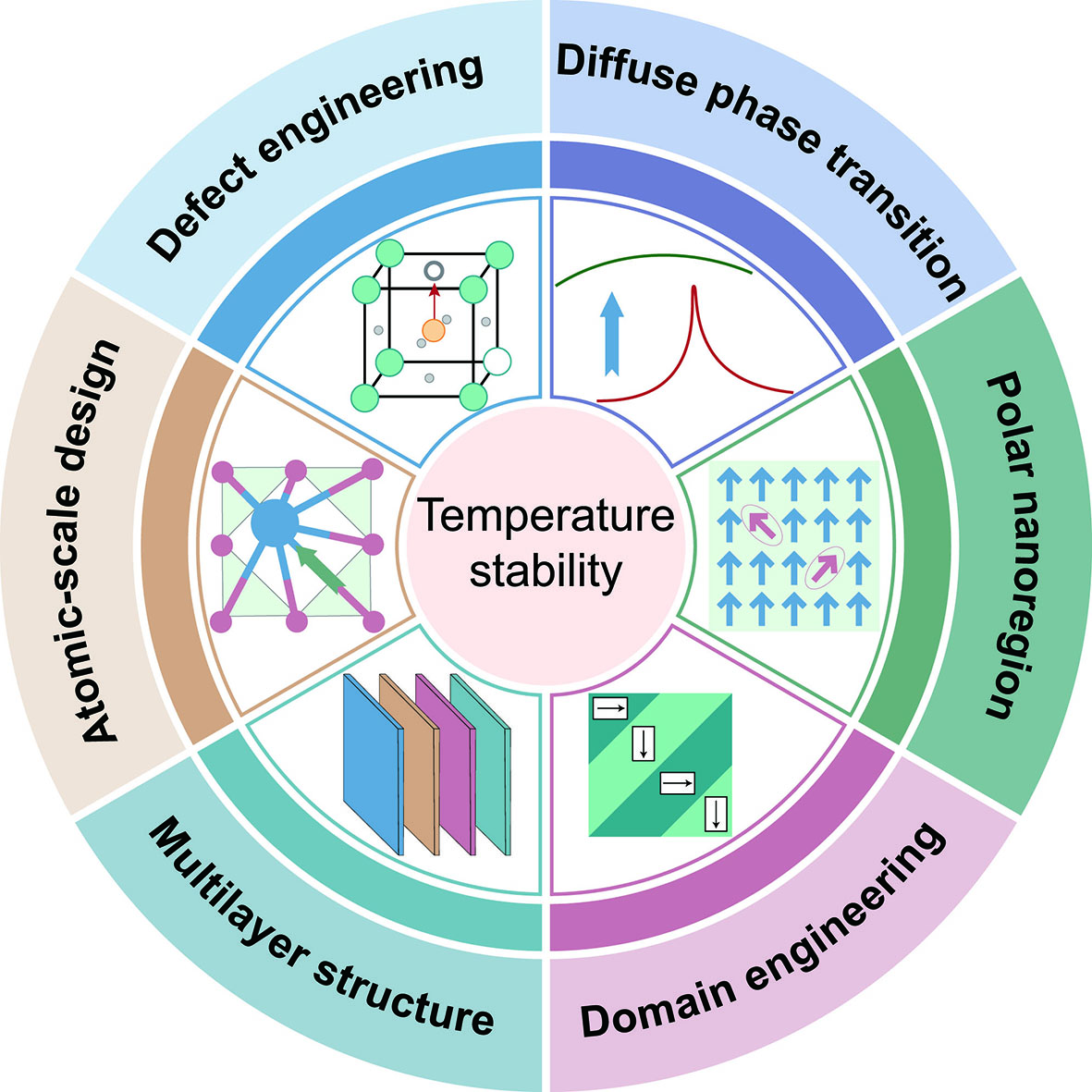

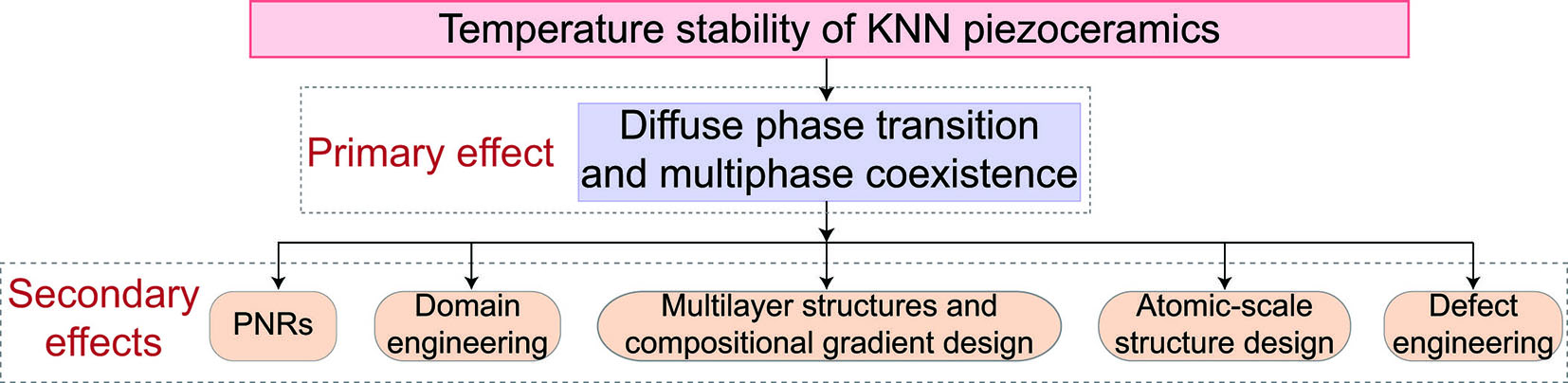

Potassium sodium niobate (KNN) lead-free piezoceramics are among the most promising candidates to replace lead-based counterparts. However, the limited temperature stability of KNN ceramics remains a critical challenge for practical application. This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in both the performance and temperature stability of KNN-based piezoceramics. Special emphasis is placed on the correlation between microstructure and temperature stability, with a systematic analysis of key strategies, including diffuse phase transition with multiphase coexistence, polar nanoregions, domain engineering, multilayer gradient doping structure, atomic-scale local ferroelectric state design, and defect engineering. Furthermore, an objective evaluation of these advances is provided to examine the potential mechanisms underlying these strategies. Beyond summarizing recent progress in improving the properties and temperature stability of KNN-based ceramics, this review highlights the intricate interplay between microstructure and piezoelectric performance, offering valuable insights to guide future research and the rational design of high-performance, temperature-stable KNN-based lead-free piezoceramics.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Piezoceramic materials are widely employed in actuators, transducers, sensors, and other applications due to their ability to convert mechanical signals to electrical signals[1-3]. Currently, the market is primarily dominated by lead-based ceramics, particularly Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 (PZT) ceramics[4], which exhibit excellent piezoelectric performances, high electromechanical coupling coefficients, and high mechanical quality factors, making them ideal for practical applications[5-7]. However, the environmental and health concerns associated with lead toxicity have driven an urgent need for the development of lead-free piezoceramic systems[8-11].

Among various lead-free candidates, (K,Na)NbO3 (KNN)-based piezoceramics are considered one of the most promising alternatives due to their high piezoelectric properties and high Curie temperature[12-14]. Researchers have developed KNN-based ceramics with high piezoelectric properties comparable to those of PZT ceramics through various strategies[15-17]. However, their practical applications, particularly in harsh environments, remain limited due to several inherent challenges, including a narrow sintering window, relatively low Curie temperature, and, most critically, poor temperature stability[18-21].

The electrical properties and temperature stability of KNN-based ceramics are intrinsically linked to their microstructure[20,22,23]. Temperature variations can induce significant changes in the crystal structure and domain configuration of these ceramics, thereby affecting their functional performance[24-27]. Recent research efforts have primarily focused on improving the temperature stability of KNN-based lead-free piezoceramics through various strategies, including phase boundary design[28-30], multilayer structure[31-34], and defect modulation[35-37]. These approaches fundamentally involve microstructural engineering, offering valuable insights for the development of KNN-based ceramics with both superior piezoelectric performance and improved temperature stability. Therefore, a comprehensive review of these advancements is essential for summarizing the underlying principles and outlining future directions for the design and optimization of KNN-based lead-free piezoceramics.

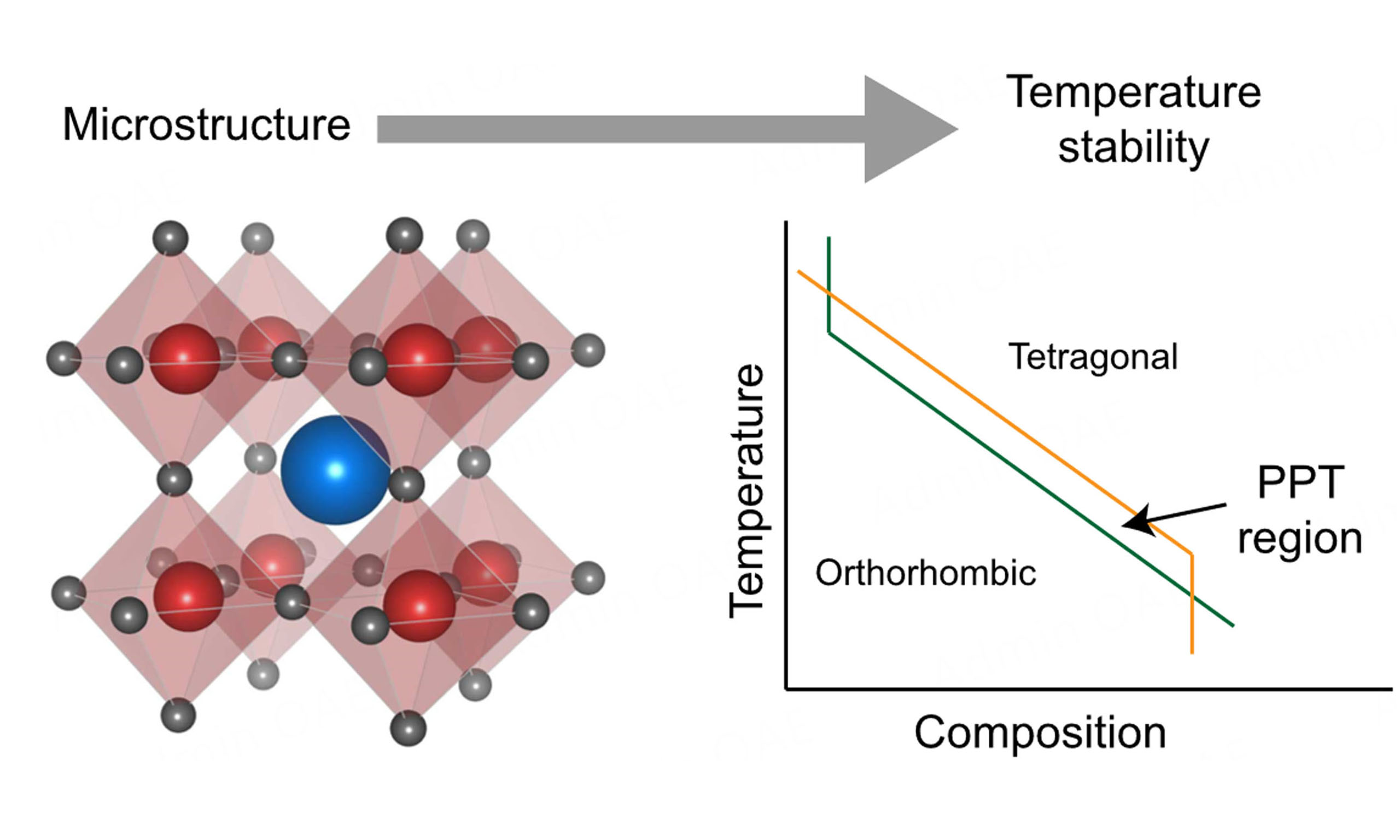

This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in enhancing the temperature stability of KNN-based piezoceramics through microstructural engineering, as illustrated in Figure 1. It systematically examines the effects of various strategies, including phase boundary design, multilayer structure, gradient doping, defect modulation, atomic-scale design, and domain engineering, on the electrical properties and temperature stability of KNN-based ceramics. The underlying mechanisms governing these approaches are analyzed, and their impact on material performance is discussed in detail. In addition, the limitations of these studies and the proposed mechanisms are further discussed and analyzed to provide deeper insight into the relationship between microstructure and temperature stability. Finally, the review highlights key challenges, future research directions, and potential opportunities for further advancements. By offering a deeper understanding of the interrelationship between microstructure, electrical properties, and temperature stability, this work aims to facilitate the development of high-performance KNN-based ceramics and guide the design of next-generation high-temperature piezoelectric devices.

ORIGIN OF POOR TEMPERATURE STABILITY IN KNN-BASED PIEZOCERAMICS

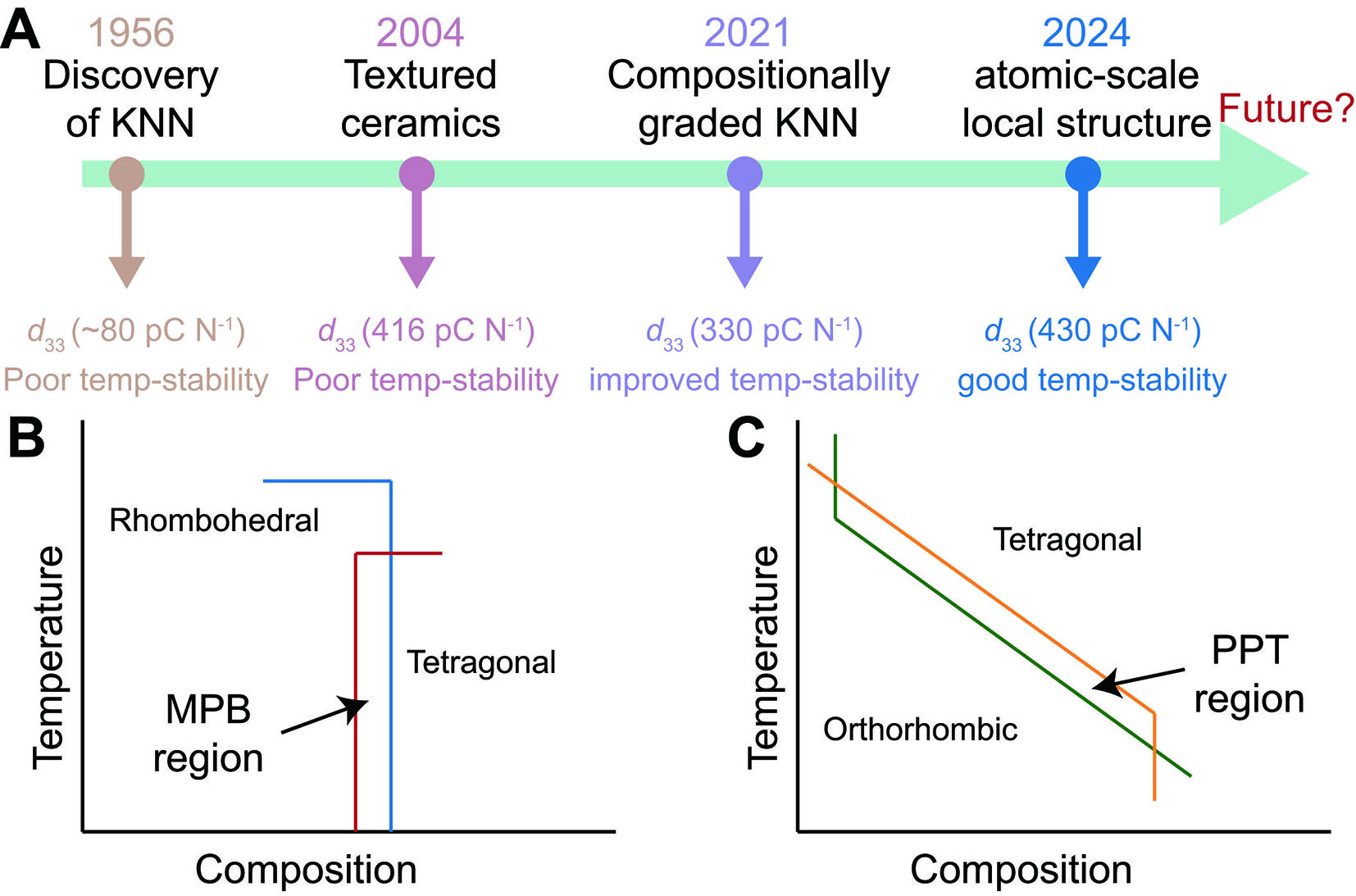

KNN-based lead-free piezoceramics have been investigated for over 60 years. As shown in Figure 2A, they were first discovered by L. Egerton and D.M. Dillon in 1959, exhibiting a piezoelectric coefficient (d33) of

Figure 2. Origin of poor temperature stability in KNN-based piezoceramics. (A) Evolution of the piezoelectric properties and temperature stability of KNN-based piezoceramics. Schematic illustrations of (B) the MPB and (C) the PPT.

The high piezoelectric performance of KNN-based piezoceramics originates from the polymorphic phase transition (PPT); however, this transition also results in poor temperature stability. This behavior contrasts with the morphotropic phase boundary (MPB) in PZT ceramics[41,42]. As shown in Figure 2B, when the Zr and Ti elements are near a 1:1 ratio, a phase boundary forms, where rhombohedral and tetragonal phases coexist. This phase coexistence facilitates ferroelectric domain switching, promotes domain wall motion, and minimizes the system’s free energy, thereby enhancing the piezoelectric performance of PZT ceramics[43-45].

Similarly, in the PPT region [Figure 2C], the coexistence of orthorhombic and tetragonal phases contributes to improved piezoelectric properties[46,47]. However, unlike MPB, which is solely composition-dependent and remains unchanged with temperature[48], PPT is influenced by both composition and temperature[49]. As the temperature varies, the phase boundary shifts beyond the PPT region, leading to performance degradation. This temperature-driven phase instability is the fundamental reason for the poor temperature stability of KNN-based piezoceramics[50-52].

STRATEGIES FOR IMPROVING THE TEMPERATURE STABILITY

Since the PPT shifts with temperature, minimizing or eliminating the temperature dependence of PPT has become a primary strategy for improving the temperature stability of KNN-based ceramics. One of the most common and effective approaches is to broaden the orthorhombic-tetragonal phase transition temperature range by introducing a diffuse phase transition. By transforming the phase transition point into a broader phase transition region, the PPT becomes less sensitive to temperature fluctuations, thereby ensuring stable performance over a wider temperature range[53-55].

Building on this concept, several effective methods have been proposed, which are based on the diffuse PPT region. For instance, multilayer structure and gradient doping combine individual layers with different phase transition temperatures, resulting in an overall broadened phase transition region[31,33]. Additionally, polar nanoregions can be utilized to design relaxor ferroelectrics, thereby creating diffuse phase transition regions near room temperature[56,57]. Moreover, atomic-scale structural design and the domain pinning effect induced by defect dipoles have also been shown to significantly enhance the temperature stability of KNN-based ceramics[37,40].

To ensure consistent performance evaluation of lead-free piezoelectric materials under elevated temperatures, it is critical to establish a standardized set of metrics. These include both intrinsic and extrinsic parameters such as the small-signal piezoelectric coefficient (d33), large-signal piezoelectric coefficient (d33*), electrostrain, Figure of Merit (FOM), electromechanical coupling coefficient (Kp), loss tangent, and mechanical quality factor (Qm). Each of these metrics reflects different aspects of the piezoelectric behavior and exhibits varying sensitivities to temperature-induced depolarization and domain wall pinning. Typically, small-signal d33 and Kp are dominated by intrinsic lattice responses and thus tend to provide more thermally stable indicators[58]. In contrast, FOM and electrostrain are strongly influenced by extrinsic domain wall contributions, making them more prone to degradation under high-temperature conditions[2]. Loss tangent and Qm reflect dielectric and mechanical losses, respectively, and offer valuable insights into energy dissipation mechanisms in thermally stressed environments[7]. The temperature sensitivity of these metrics should be carefully considered when selecting materials for specific application scenarios or functional devices.

Diffuse phase transition and multiphase coexistence

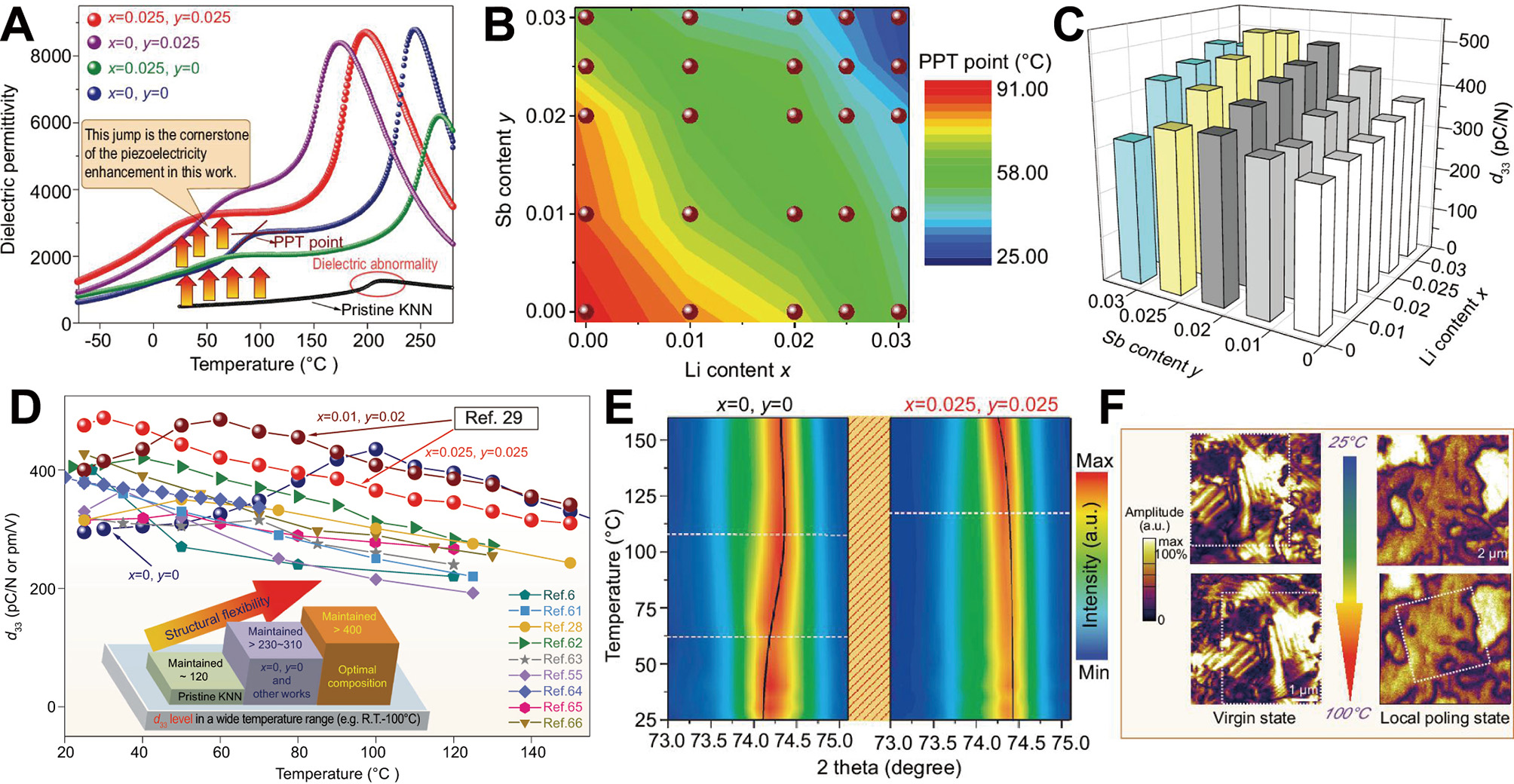

Stabilizing the PPT region over a broad temperature range through diffuse phase transitions and multiphase coexistence is a widely adopted strategy[54,59]. By constructing a diffuse phase transition region near room temperature, the temperature sensitivity of the PPT can be reduced, resulting in more stable piezoelectric performance over an extended temperature range[23,60]. Liu et al. designed the composition

Figure 3. Diffuse phase transition and composition-induced structural flexibility to enhance the temperature stability. (A) Dielectric-temperature curves of different compositions. (B) The PPT point of LxKNNSy-BZ-BNH-1Mn compositions. (C) The d33 of the LxKNNSy-BZ-BNH-1Mn composition at room temperature. (D) Variation of d33 with temperature. (E) In situ temperature neutron diffraction of the (002)PC reflection peak of the x = y = 0 and x = y = 0.025 samples. (F) PFM images of the x = y = 0.025 sample in both virgin state and local poling states at different temperatures. This figure quoted with permission[29]. Copyright 2020, Oxford University Press.

The in situ temperature stability of d33 for the compositions was assessed, as shown in Figure 3D[6,28,55,61-67]. As anticipated, all compositions reached their maximum d33 near the phase transition temperatures, followed by a monotonic decline as the temperature deviated from the phase transition region. In addition to the diffusion of the PPT, the author identified another key factor: composition-induced structural flexibility. Temperature stability is closely linked to the evolution of the phase structure[67]. In situ temperature neutron diffraction measurements were performed on compositions with x = y = 0 and x = y = 0.025. Figure 3E illustrates the (002)PC reflections across the temperature range of 20-160 °C. For the x = y = 0 sample, the (002)PC reflections exhibited noticeable changes with increasing temperature, whereas the x = y = 0.025 compositions showed minimal variation, remaining nearly unchanged between 20 and 100 °C. This phenomenon demonstrates the significant role of structural flexibility in enhancing temperature stability. It should be noted that, although structural flexibility may contribute to the improved temperature stability of KNN ceramics, its effect has not been quantitatively evaluated. The contribution of structural flexibility may be relatively limited, and the excellent temperature stability observed in the composition with x = y = 0.025 is likely still primarily attributed to the construction of a diffuse phase transition.

The piezoelectric properties are closely related to domain morphology[68]. Micro-scale domain structures were examined using the piezoelectric force microscope (PFM). In situ measurements of the domain morphology in both the virgin and locally poled states of the x = y = 0.025 composition were conducted at various temperatures. Figure 3F presents magnified domain images, revealing no significant changes within the temperature range of 25-100 °C.

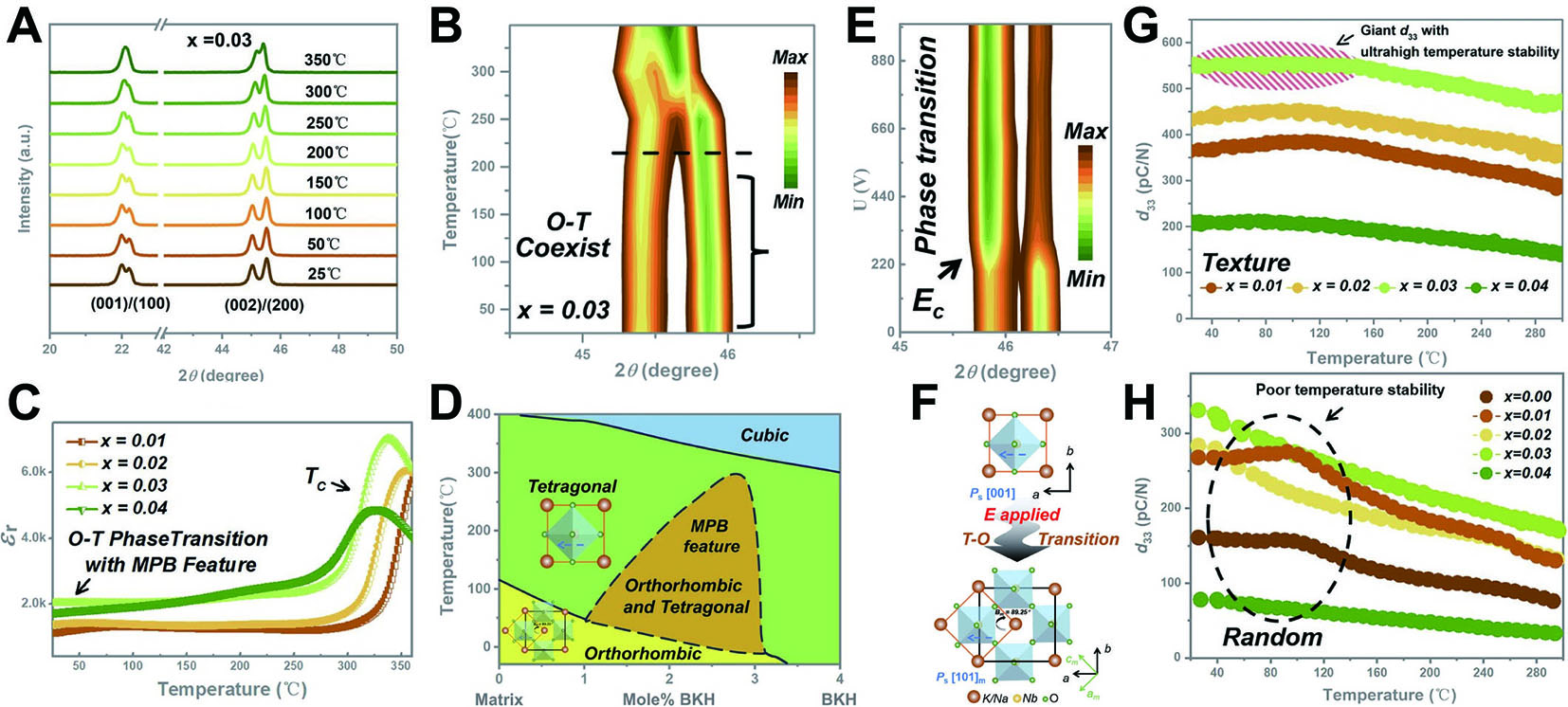

Enabling PPT to exhibit MPB-like features as a new phase boundary, making it temperature-insensitive, is an important objective. Texture engineering is widely employed to enhance the piezoelectric properties of ceramics, and the oriented structure contributes to the stability of the domain structure[69,70]. Therefore, the joint effect of temperature-insensitive PPT phase transition and texturing has been demonstrated by

As shown in Figure 4A and B, in the composition

Figure 4. Diffuse PPT phase transition and texturing engineering to enhance the piezoelectricity and temperature stability. (A and B) In situ temperature XRD of KNN-BNZ-3BKH. (C) Dielectric-temperature curves of different compositions. (D) Schematic diagram of the phase boundary. (E) In situ electric field XRD of KNN-BNZ-3BKH. (F) Schematic diagram of crystal structure transformation with and without an electric field. Temperature dependence of (G) random and (H) textured KNN-BNZ-3BKH ceramics. This figure quoted with permission[30]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature.

As shown in Figure 4D, by adjusting the appropriate content of BKH, a phase transition region similar to MPB can be constructed in KNN[72]. To evaluate the phase transition under an electric field, in situ electric field X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed on the KNN-BNZ-3BKH composition [Figure 4E]. Upon application of an electric field, the (002)/(200) diffraction peak is gradually shifted to a smaller angle, and KNN-BNZ-3BKH is gradually transformed from O-T coexistence to the O phase. The crystal structure with and without an electric field is shown in Figure 4F. The lattice distortion is reversible upon removal of the electric field, and this reversible lattice deformation is the origin of the superior piezoelectric properties[73].

Subsequently, the piezoelectric properties and temperature stability of KNN-BNZ-3BKH were further improved by texturing engineering. As shown in Figure 4G and H, texturing increased the d33 of KNN-BNZ-3BKH from 340 to 550 pC N-1 at room temperature. The stability of the textured ceramics was also significantly enhanced, with piezoelectricity decreasing by only 10% over the temperature range of

Polar nanoregions

The electrical properties of piezoelectric materials can be enhanced through doping, which leads to the formation of polar nanoregions (PNRs). These localized nanoregions, with randomly oriented polarization, exhibit low free energy states[74,75]. The presence of PNRs promotes a more relaxed ferroelectric state, which can also lead to a diffuse phase transition and improve temperature stability, although this may occasionally slightly reduce piezoelectric performance[76]. It is important to note that PNRs are different from the diffuse PPT in the intrinsic mechanisms. While a diffuse PPT arises from the broadening and diffusion of the phase transition region, the formation of PNRs is primarily driven by local polarization vector disorder.

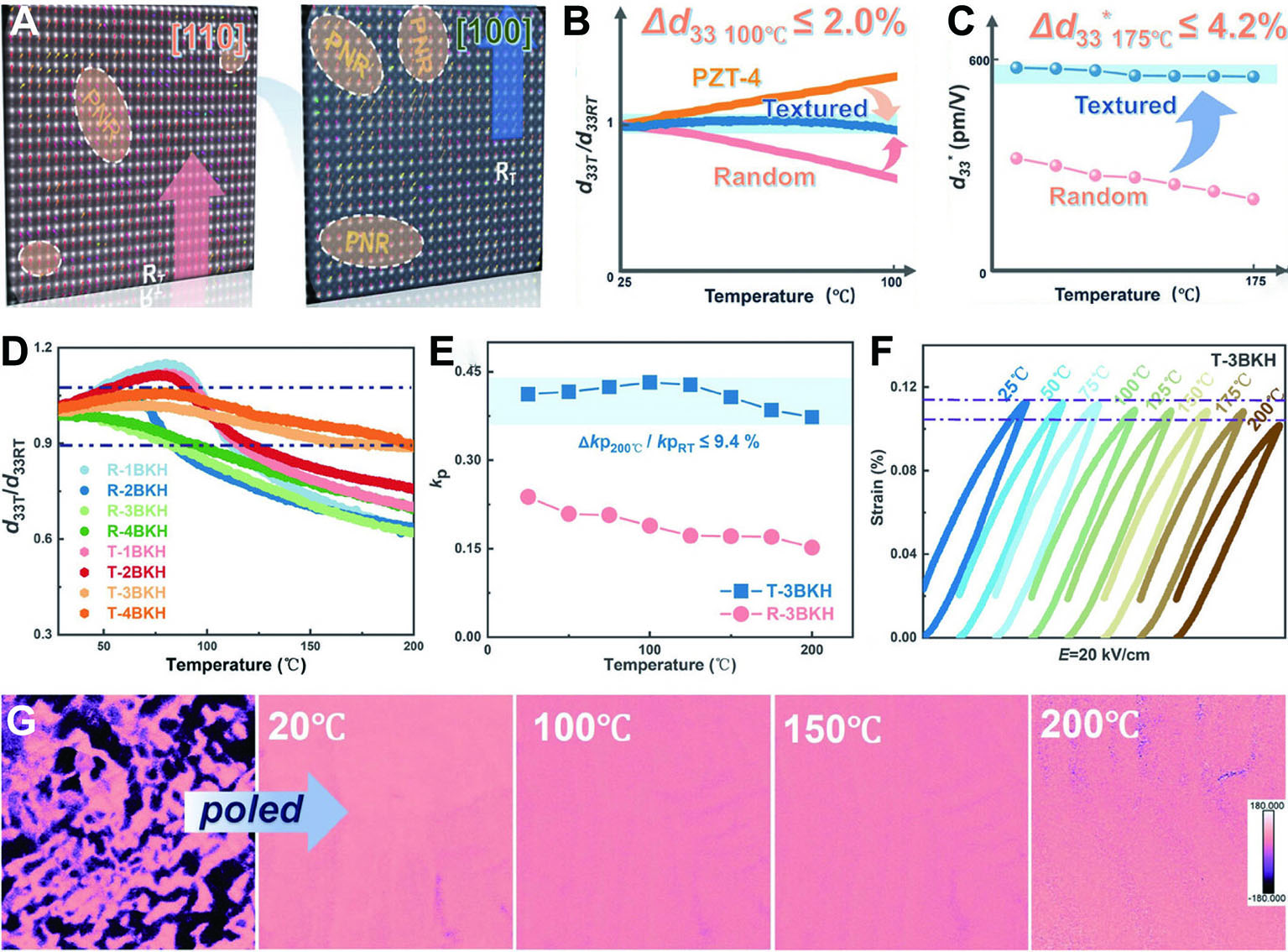

Hua et al. improved both the piezoelectric properties and temperature stability of KNN ceramics by combining PNRs with texturing engineering[56]. In their study, the base composition was 0.99[(K0.5Na0.5)(Nb0.98Ta0.02)O3]-0.01[Bi(Ni0.67Nb0.33)O3][77]. They then introduced (Bi0.5K0.5)HfO3 (BKH) into the KNN-based system to induce relaxation states and influence the phase transition temperature[78,79]. Additionally, texturing engineering was employed to enhance anisotropy and preserve piezoelectric performance. As shown in Figure 5A-C, the results indicate that the novel multi-scale structure enabled the 0.96((K0.5Na0.5)(Nb0.98Ta0.02)O3)-0.01(Bi(Ni0.67Nb0.33)O3)-0.03(Bi0.5K0.5)HfO3 ceramics to achieve both excellent piezoelectric performance and exceptional temperature stability.

Figure 5. Improvement of piezoelectric performance and thermal stability in KNN ceramics through PNRs and texturing. (A-C) Strategy for simultaneously enhancing piezoelectricity and thermal stability in KNN ceramics by constructing a single-phase structure and embedding PNRs. (D) In situ temperature dependence of d33 for random and textured xBKH-KNN ceramics. (E) In situ variable-temperature kp for 3BKH-KNN ceramics. (F) Electrostrains at different electric fields for T-3BKH-KNN ceramics. (G) In situ variable-temperature PFM phase images for T-3BKH-KNN ceramic. This figure quoted with permission[56]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH.

The temperature stability of the piezoelectric response was further compared between textured (T-xBKH) and random (R-xBKH) ceramics, as shown in Figure 5D. By constructing a single T-phase to prevent temperature-induced phase transitions, the temperature stability of R-xBKH ceramics was successfully achieved when x ≥ 3, with further improvement through texturing. Specifically, the d33 of T-3BKH ceramics fluctuated by only 2.0% from 25 to 100 °C and by 10.0% up to 200 °C. More importantly, the kp of the T-3BKH textured ceramics fluctuated by just 9.4% over the temperature range from 25 to 200 °C [Figure 5E]. As shown in Figure 5F, the large signal d33* of T-3BKH ceramics remains stable from 25 to 200 °C, indicating good temperature stability.

To investigate the mechanism of thermal stability from the domain morphology, PFM was employed to examine the temperature-dependent changes in the domains of poled T-3BKH ceramics, as shown in

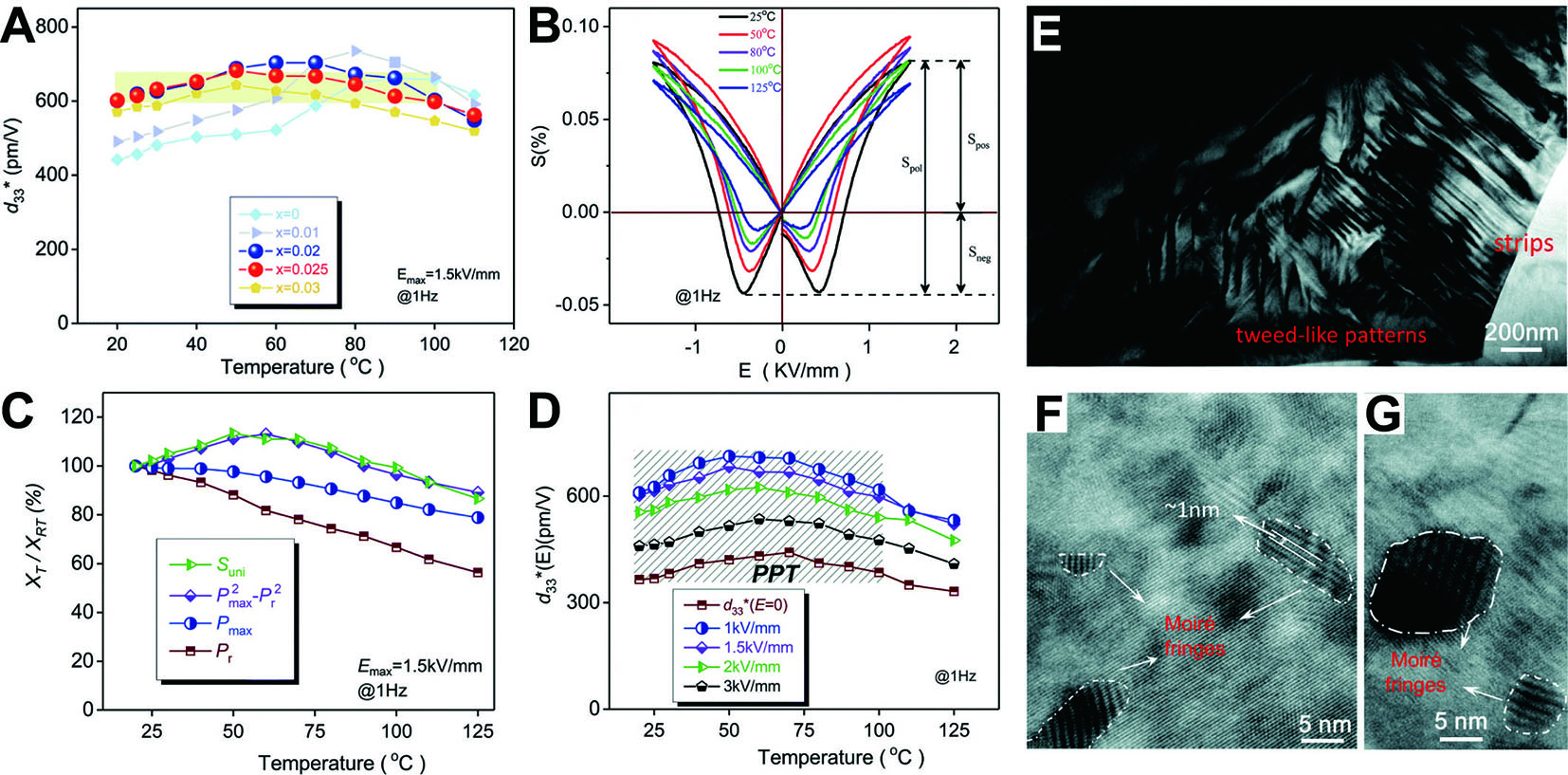

Similarly, Liu et al. constructed a rhombohedral-orthorhombic-tetragonal (R-O-T) phase transition to enhance thermal stability[57]. A diffuse phase transition with excellent temperature stability was achieved by introducing relaxation states via PNRs. Figure 6A presents the temperature-dependent d33* values measured across a range of temperatures (20-110 °C) for the compositions

Figure 6. Temperature stability of large-signal inverse piezoelectric coefficient through PNRs. (A) Temperature stability of d33*. (B) Bipolar electrostrain of the x = 0.025 composition. (C) Temperature dependence of Suni, Pr, Pmax and

Domain engineering

Electrostrain in piezoceramics primarily originates from the domain activity, making the temperature stability of electrostrain closely dependent on their ferroelectric domain structures[86]. This effect is particularly pronounced near the phase transition region, where enhanced domain dynamics contribute significantly to the macroscopic strain response[87,88]. Consequently, understanding the temperature-dependent evolution of domain structures and their corresponding piezoresponse is crucial for achieving stable piezoelectric performance.

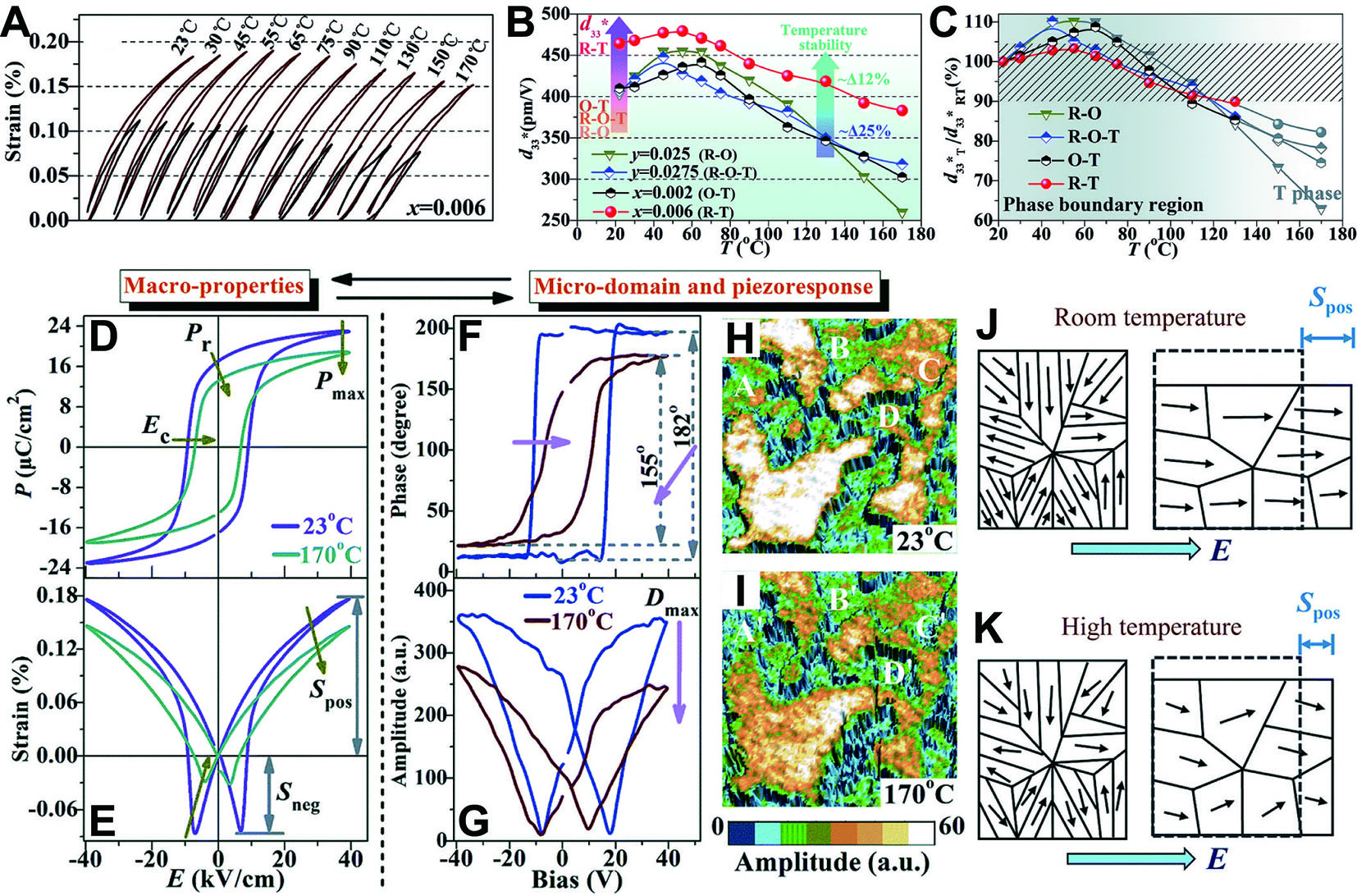

To address this, Zhao et al. proposed a strategy to achieve stable strain performance by leveraging the contributions of domain dynamics and polarization evolution at phase boundaries[89]. As shown in Figure 7A, the (1-x-y)K0.4Na0.6Nb0.955Sb0.045O3-xBiFeO3-yBi0.5Na0.5ZrO3 (KN0.6NS0.045-xBF-yBNZ) composition

Figure 7. Enhancing temperature stability through domain engineering. (A) Temperature-dependent Sneg for the composition with

The domain structure plays a crucial role in determining the piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties, as well as the temperature stability of piezoelectrics[90,91]. Domain switching and domain wall motion serve as the mesoscopic mechanisms underlying the P-E loops and S-E curves in these materials[92,93]. As temperature increases, thermal disturbances inevitably destabilize domains[94]. For instance, in the

Multilayer structures and compositional gradient design

In a homogeneous system (one-component ceramic), the phase transition temperature is typically well-defined, which can limit temperature stability. However, by stacking homogeneous single layers into a multilayer structure, the overall system can exhibit a diffuse phase transition region, significantly enhancing temperature stability. Multilayer structure with varying compositions holds great potential for achieving excellent temperature stability in bulk ceramics[32,34]. Zhao et al. demonstrated that the multilayer structural design in lead-free systems could maintain excellent temperature stability performance in the range of room temperature to 130 °C[95]. However, this strategy requires careful matching of single-layer compositions, making the rational design of multilayer ceramics for temperature stability both demanding and challenging. On the other hand, chemical diffusion between the single layers during high-temperature sintering will cause the composition to deviate from the designed stoichiometric ratio.

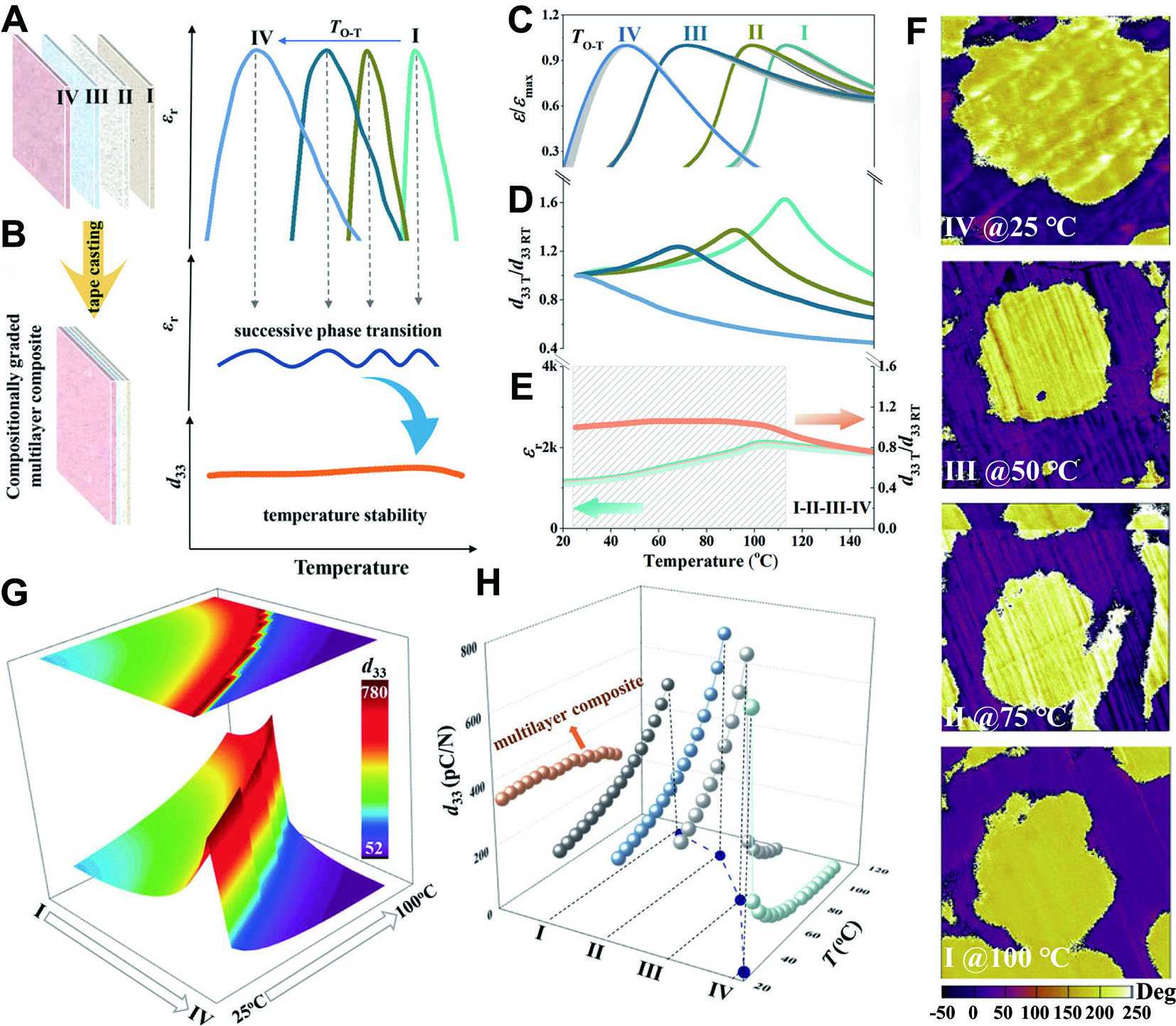

Building on this strategy, Zheng et al. further improved KNN ceramics by combining a multilayer structure with composition grading, enabling continuous phase transitions across layers and achieving enhanced temperature stability [Figure 8A and B][33]. The system (1-x)(K0.48Na0.52)(Nb0.955Sb0.045)O3-xBi0.5Na0.5ZrO3-0.2%Fe2O3 [(1-x)KNNS-xBNZ-Fe], which features varying phase transition temperatures through chemical composition modification [Figure 8A], was prepared using the tape casting method [Figure 8B]. Figure 8C illustrates the dielectric permittivity ε/εmax at different temperatures of each layer. By adjusting the BNZ content, different O-T transition temperatures are obtained, accompanied by a broadened O-T phase transition region. An increase in piezoelectric performance for the four compositions is also observed near the O-T transition, as demonstrated by the in situ temperature dependence of d33 [Figure 8D]. Figure 8E displays the dielectric-temperature curves of the multilayer structure, where diffuse O-T phase transitions occur over the range of 25-112 °C (indicated by the shaded region), resulting in minimal piezoelectric variation of less than 6%.

Figure 8. Multilayer structures and compositional gradient design. (A and B) Schematic diagrams for the mechanism of multilayer compositional gradients. Temperature dependence of (C) ε/εmax (D) d33T/d33RT, and (E) εr of each layer. (F) PFM images of the single layer near the O-T transition. (G) Phase-field simulation of the multilayer composite. (H) Temperature-dependent d33 of the single and multilayer composite, calculated from the simulation results. This figure quoted with permission[33]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH.

The domain structure of ferroelectrics is highly sensitive to temperature, leading to performance variations under thermal treatment[6]. Given the critical role of domains in thermal stability, the evolution of the domain structure in each layer is shown in Figure 8F. In layer I, the oriented domains exhibit almost no back-switching due to the higher O-T transition temperature (≈ 112 °C), ensuring stable domain evolution. In contrast, the other three layers display significant back-switching when the temperature exceeds their respective O-T transition temperature. Consequently, in the multilayer composite, integrating layers with different phase transition temperatures allows the oriented domains to remain stable as long as the measurement temperature stays below the O-T transition temperature of each layer.

To gain deeper insight into this phenomenon, phase-field simulations were conducted to compare the temperature stability of d33 between the multilayer composite and the individual layers. Figure 8G presents the multivariate surface of composition, temperature, and d33, illustrating the variation in simulated d33 along the composition gradient. Figure 8H compares the temperature stability of d33 between the multilayer structure and the single-layer composition. Notably, in contrast to the abrupt changes in the piezoelectric coefficient observed in single-layer constituents, the phase-field simulation demonstrates stable performance across the temperature range of 25-100 °C for the multilayer composite. This result aligns well with the experimental data shown in Figure 8C-E.

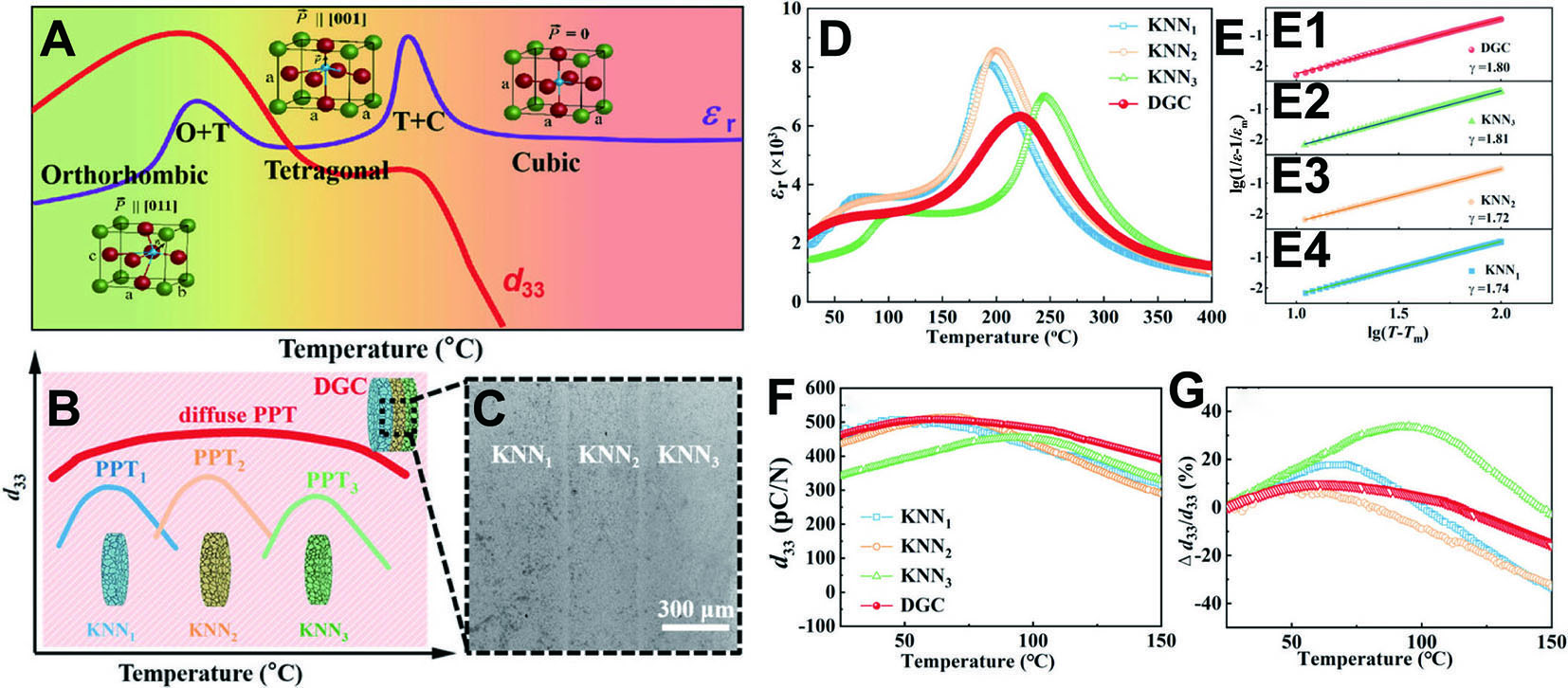

As previously discussed, the piezoelectric performance significantly deteriorates as the temperature deviates from the PPT region [Figure 9A]. Song et al. designed a dopant-graded ceramic (DGC) by combining three ceramic layers, labeled as KNN1, KNN2, and KNN3, each with distinct PPT temperatures [Figure 9B]. The DGC structure demonstrated a wide operating temperature range and achieved a high d33 value of

Figure 9. Dopant-graded strategy to enhance temperature stability. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the temperature-dependent piezoelectricity of KNN ceramics. (B) Schematic diagram of composition grading with diffuse PPT. (C) SEM image of the DGC with a multilayer structure. (D) Dielectric-temperature curves of the DGC and each individual layer. (E) Calculated γ using the modified Curie-Weiss law. (F and G) Temperature dependence of d33 for the DGC and each individual layer. This figure quoted with permission[31]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH.

The dielectric-temperature (εr-T) curves of the single-layer ceramics and the DGC were analyzed to understand their phase structures. The curves revealed two distinct peaks [Figure 9D], corresponding to the TO-T and the Tc, respectively. The phase transition temperatures for the KNN1, KNN2, and KNN3 layers were 50, 75, and 100 °C, respectively, which aligns with the initial design. In contrast, the DGC exhibited a broader and more diffuse PPT peak, spanning 25-150 °C [Figure 9D]. Additionally, the tetragonal-cubic phase transition in the εr-T curve of the DGC exhibited significant diffusion, with a dispersion coefficient γ of 1.80 [Figure 9D and E1][16]. This γ value surpassed the average values for the individual ceramics, which were 1.74, 1.72, and 1.81, respectively [Figure 9E2-E4]. The room-temperature d33 of the DGC is 463 pC N-1, exceeding the values for each individual layer (434, 394, and 344 pC N-1), as shown in Figure 9F. Notably, the

Atomic-scale structure design

In addition to the pronounced temperature dependence associated with PPT, the polarization configuration also plays a crucial role in determining the piezoelectric response and temperature stability of KNN ceramics. Zeng et al. proposed that embedding PNRs with large-angle polarization into long-range ordered tetragonal phases will significantly improve temperature stability[96]. This improvement is attributed to the dynamic equilibrium between the polarization configuration and the permittivity throughout the temperature variation. Therefore, both the average phase structure and microstructural features, such as polarization configurations, must be considered concurrently when evaluating the temperature stability of KNN-based ceramics. Multi-element doping not only influences the phase structure of solid solutions but also alters the local atomic structure[58]. These modifications impact the system energy barriers and polarization rotation, thereby affecting the performance of the piezoceramics[97,98]. As a result, the atomic-scale design of local structures and the ferroelectric state plays a crucial role in optimizing both the performance and stability of piezoceramics[99,100].

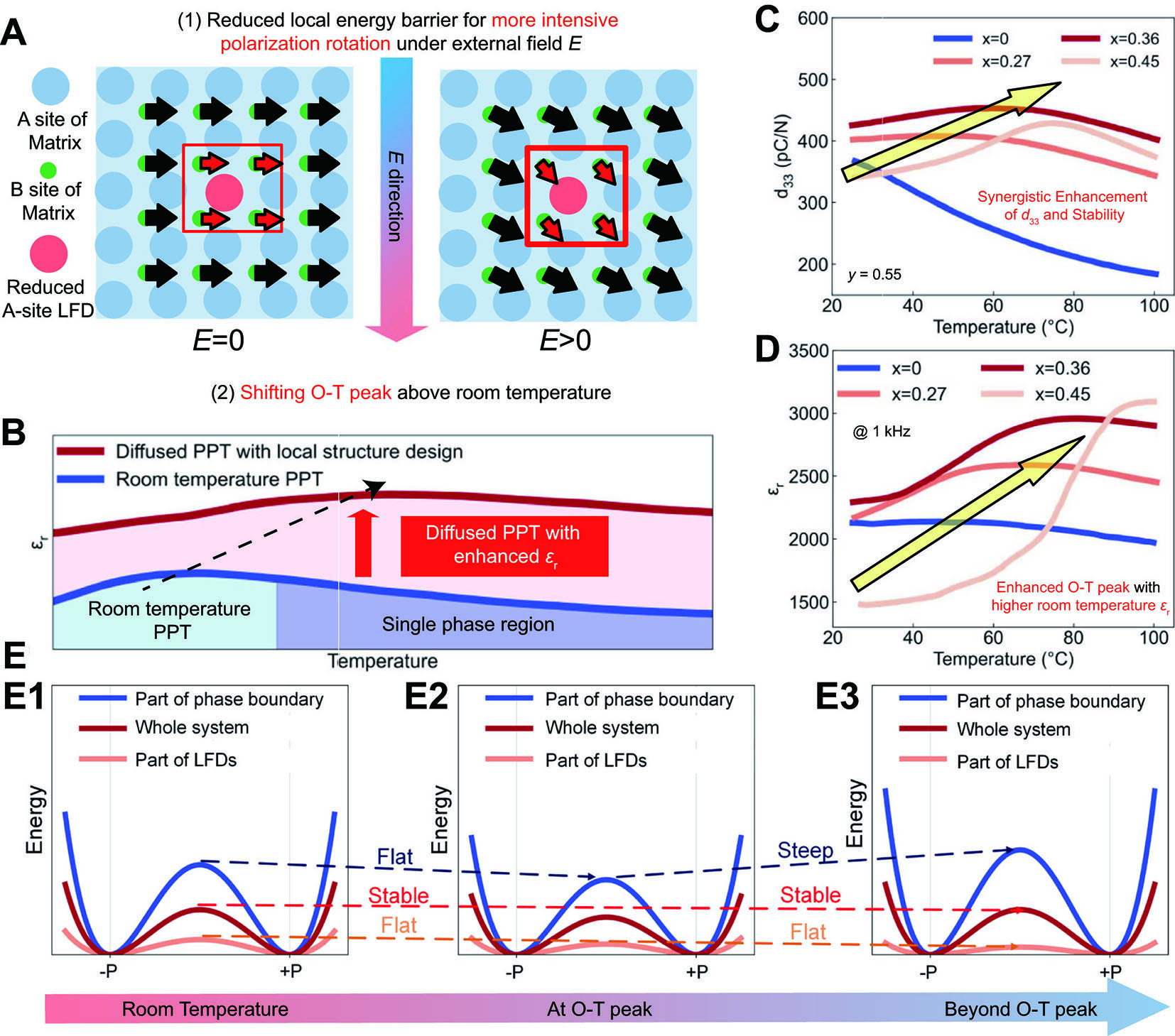

Zou et al. demonstrate a synergistic enhancement of piezoelectric properties and temperature stability in 0.945KNN-0.055(Bi0.5K0.5)1-xBaxZrO3 ceramics through atomic-scale ferroelectric structure design[40]. By modulating the localized Landau energy barrier at the doping site, temperature-induced fluctuations in d33 were effectively suppressed. The Local Ferroelectric Distortion (LFD) at dopant sites was defined by the difference between the two Nb-O bond lengths along the direction of spontaneous polarization. As stated above, the temperature instability of KNN ceramics arises from the PPT[101-103]. The authors aim to mitigate this instability by minimizing A-site LFD, thereby constructing a PPT region with a lower energy barrier at room temperature. First, comparisons between PbTiO3 and BaTiO3 have shown that a reduction in A-site ferroelectric distortion decreases the stability of the tetragonal phase[104]. Thus, by decreasing A-site LFD, the O-T phase transition temperature can be shifted upward, resulting in a more diffuse PPT region. Second, reducing A-site LFD creates numerous lower-energy-barrier regions, which promote polarization rotation [Figure 10A]. These regions help compensate for the reduction in εr [Figure 10B], thereby simultaneously enhancing both d33 and temperature stability.

Figure 10. Strategy schematic for synergistically enhancing d33 and temperature stability. (A) Reduced LFD in the matrix to promote polarization rotation. (B) Construction of a diffused PPT phase boundary by elevating the O-T transition temperature. (C) Temperature dependence of d33 for different KNN ceramic compositions. (D) Dielectric-temperature curves for different KNN ceramic compositions. (E) Schematic diagrams of the PEC at room temperature, the O-T transition, and above the O-T transition. This figure quoted with permission[40]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature.

To validate this approach, the system 0.945KNN-0.055(Bi0.5K0.5)1-xBaxZrO3 was chosen as a model. This system demonstrates an impressive d33 of approximately 360 pC N-1[105,106]. A room-temperature R-(O)-T phase boundary was established by adjusting the parameter y. At x = 0, a high d33 of about 360 pC N-1 was achieved. However, similar to other compositions with R-T phase boundaries at room temperature[55,61,107-110], a significant fluctuation of approximately 50% was observed within the range of 25-100 °C, with d33 decreasing to around 180 pC N-1 at 100 °C [Figure 10C]. To improve stability, the Ba element was introduced into the system to reduce the A-site LFD. As shown in Figure 10D, increasing the Ba content shifted the O-T transition temperature to a higher temperature while simultaneously enhancing the room-temperature d33. At x = 0.27, a stable d33 of approximately 400 pC N-1 was achieved at room temperature, with only ~13% fluctuation from 25 to 100 °C. Further increasing x to 0.36 resulted in a higher room-temperature d33 of

The potential energy curves (PEC) at different temperatures were analyzed to understand the effect of Ba doping on the phase boundary region. At room temperature, increasing the Ba content sharpens the PEC in the phase boundary region [Figure 10E1]. As the system approaches the O-T transition [Figure 10E2], the PEC becomes more moderate, which enhances d33. Beyond the O-T transition, but still in the vicinity

Defect engineering

The external contribution to large-signal piezoelectric coefficients arises mainly from domain switching[111]. Therefore, a key strategy to enhance the temperature stability of electrostrain performance is to minimize temperature-induced domain structure evolution. Defects and defect dipoles play a significant role in stabilizing ferroelectric domains by exerting a pinning effect on domain walls, thereby inhibiting domain wall motion. This stabilization helps maintain the integrity of ferroelectric domains, significantly improving the temperature stability of piezoelectric materials at elevated temperatures[112,113].

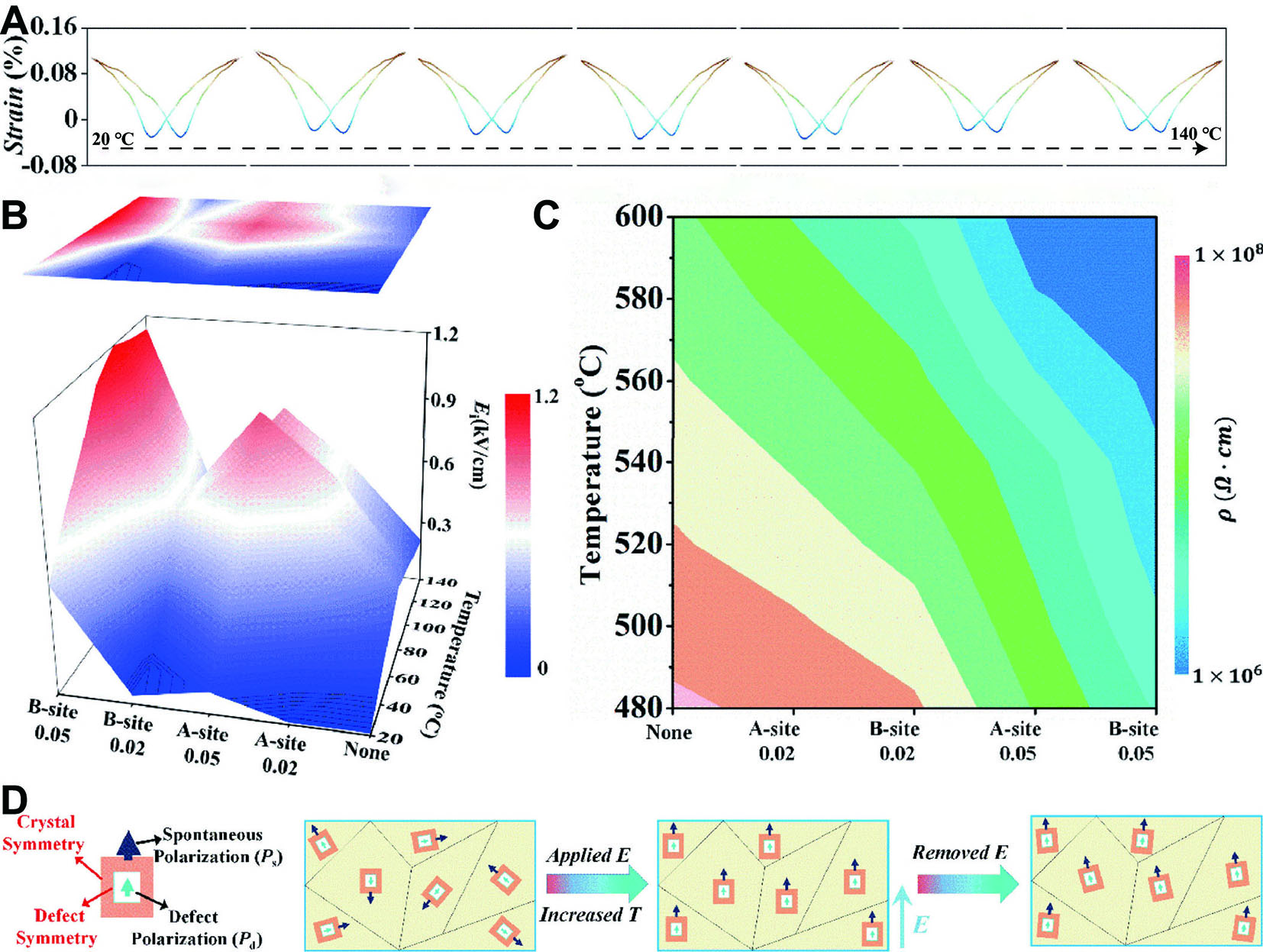

Li et al. introduced (

Figure 11. Effect of defect dipoles and space charges on the temperature stability of KNN ceramics. (A) Temperature-dependent bipolar strain of KNN-BNH-0.05Fe ceramics. (B) Variation of Ei for different dopants at different temperatures. (C) Temperature-dependent resistance comparison for different compositions at high temperatures. (D) Schematic diagrams of ferroelectric domain alignment and defect dipole behavior under an external electric field. This figure quoted with permission[35]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier Ltd.

Beyond space charge effects, the pinning effect of defect dipoles significantly influences temperature stability[37]. As shown in Figure 11D, when an external electric field is applied at high temperatures, ferroelectric domains and defect dipoles within the ceramics align with the field direction[115]. To maintain the system’s energy minimum state, these defect dipoles remain aligned with the ferroelectric domains, restricting their switching[116]. This alignment stabilizes the domain structure even after the removal of the external field, thereby contributing to the temperature stability of the ceramics.

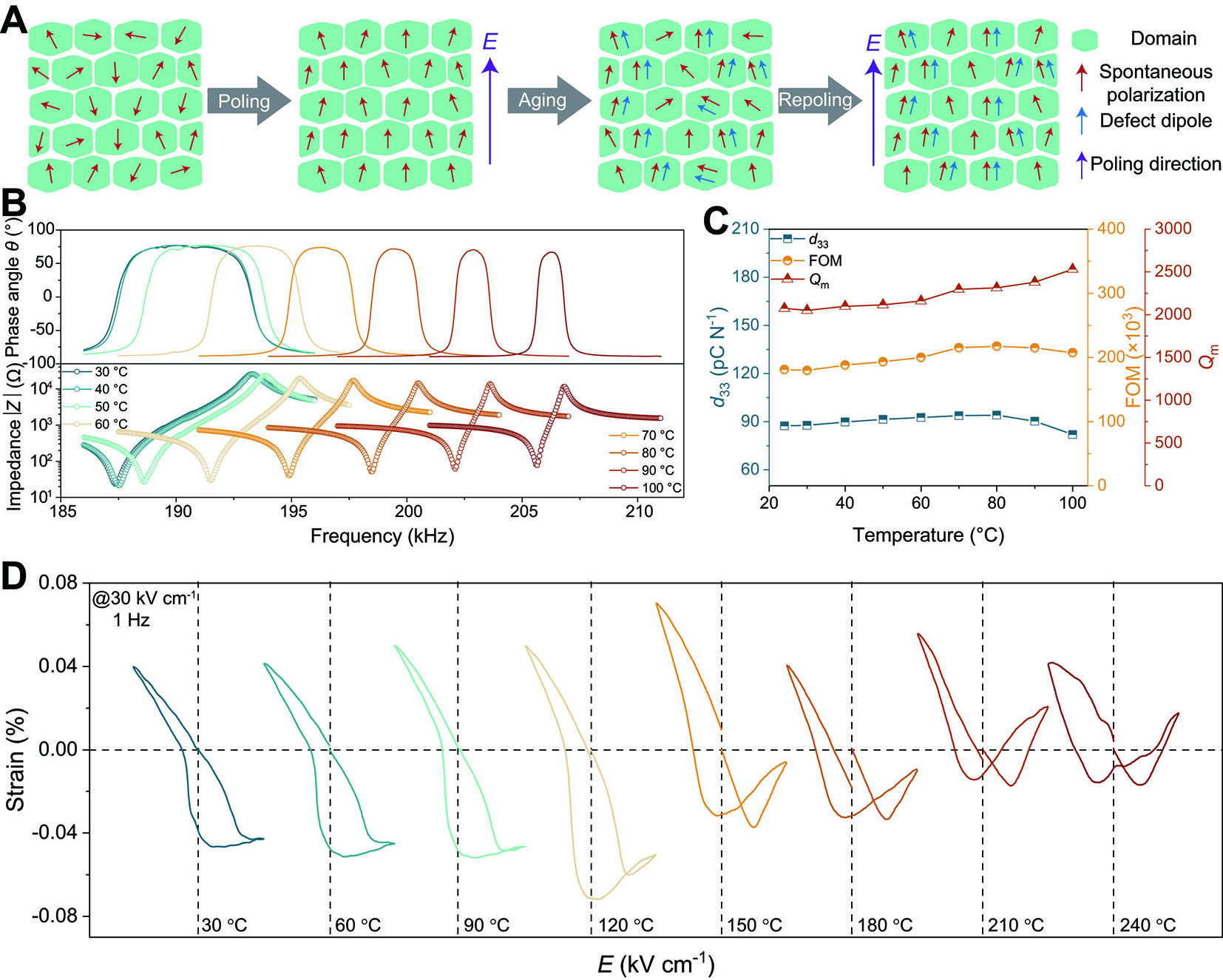

To maintain a strong pinning effect, Tian et al. proposed a poling-aging-repoling strategy to realign defect dipoles with the poling direction in the (K0.48Na0.52)0.94Li0.06Nb0.94Ta0.06O3-2%wt Cu (KNNLT-2Cu) ceramics[37]. As shown in Figure 12A, fresh piezoceramics contain almost no defect dipoles. After pre-poling, the ferroelectric domains align with the poling direction. However, during the subsequent aging process, some domains gradually deviate from the poling direction, accompanied by the formation of a large number of defect dipoles[112]. To counteract this, a repoling process is introduced to realign the ferroelectric domains and defect dipoles that have deviated from the poling direction. This realignment enhances the pinning effect, thereby improving temperature stability.

Figure 12. Poling-aging-repoing strategy to achieve strong pinning of defect dipoles. (A) Schematic illustration of the repoling process. (B) Impedance spectra of KNNLT-2Cu ceramics measured at different temperatures. (C) Calculated d33, Qm, and FOM at different temperatures. (D) Electrostrain behavior of KNNLT-2Cu after the repoling process, measured from 30 to 240 °C. This figure quoted with permission[37]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier Ltd.

Figure 12B shows the temperature dependence of the impedance spectra of KNNLT-2Cu ceramics. As the temperature increases, the phase angle remains almost constant, with only slight changes in the resonance and anti-resonance frequencies. The d33, Qm, and Figure of Merit (FOM = Qm*d33) at different temperatures are calculated and plotted in Figure 12C. The d33, Qm, and FOM remain virtually unchanged between room temperature and 100 °C, demonstrating excellent temperature stability. The high Qm values further indicate the potential of KNNLT-2Cu ceramics for high-temperature and high-power applications.

The temperature stability of electrostrain is also evaluated [Figure 12D]. Due to the strong pinning on the ferroelectric domains, asymmetric switching under different electric field directions leads to asymmetric strain curves at room temperature. While an increase in temperature does not significantly affect the strain values, it alters the symmetry of the strain curve, reflecting changes in the switching characteristics of the ferroelectric domains. Unfortunately, although KNNLT-2Cu has good temperature stability, it demonstrates a low large signal strain of 0.04%. Moreover, due to the asymmetry of the electrostrain curves, the direction of the electric field must be considered in practical applications.

PERSPECTIVES

The high performance of KNN-based lead-free piezoceramics arises from the PPT, analogous to the MPB in PZT ceramics. However, their temperature instability remains a key challenge preventing them from fully replacing lead-based counterparts. To address this challenge, several strategies have been explored. Diffuse phase transition and multiphase coexistence effectively broaden the PPT phase boundary, enhancing the piezoelectric properties and temperature stability. The introduction of PNRs increases system relaxation and expands the PPT region, further contributing to enhanced temperature stability. Engineered domain structures in the rhombohedral-tetragonal transition region enable both high piezoelectric response and enhanced stability by maintaining a relatively stable domain contribution. Meanwhile, multilayer-structured ceramics with composition-gradient doping achieve better temperature stability by averaging local variations. Lattice distortions and atomic-scale local ferroelectric state design provide additional means of modulating phase boundaries, reinforcing the interplay between structure and temperature stability. Furthermore, defect dipole engineering plays a crucial role in stabilizing ferroelectric domains by strongly pinning them and restricting domain wall motion, thereby improving temperature stability. These microstructural modifications underscore the intricate interplay between phase boundaries, domain structures, and defect chemistry in governing the temperature stability of KNN ceramics.

It should be noted that, although numerous strategies exist to enhance the temperature stability of KNN ceramics, all of them ultimately achieve this by broadening and diffusing the PPT region. Therefore, an objective evaluation is necessary to determine whether these strategies truly contribute to the excellent temperature stability or merely stem from diffuse phase transitions. Specifically, the limitations of these strategies should be carefully considered. Although defect engineering can effectively stabilize domain configurations and suppress extrinsic contributions at elevated temperatures, it often leads to increased coercive fields, which may hinder domain switching under practical electric field conditions. Multilayer architectures, while advantageous for enhancing poling efficiency and enabling the application of higher electric fields, are susceptible to poling fatigue and long-term reliability issues. In addition, relaxor-like behavior arising from PNRs can extend the operational temperature range; however, it is often accompanied by increased dielectric loss and a reduction in piezoelectric performance at room temperature. Given this, addressing the temperature dependence of PPT is fundamental to improving the temperature stability of KNN ceramics, the target that may not be achieved through a single strategy alone [Figure 13].

From a technological perspective, several challenges persist in optimizing KNN-based ceramics for practical applications, including precise microstructural control, interfacial compatibility in multilayer and compositionally graded structures, long-term stability of defect engineering, and consistency in performance during scale-up production. Tackling these critical challenges demands a bold, integrative, multi-strategy approach. Dynamic defect engineering holds the potential for achieving intrinsic self-healing capabilities and ensuring the long-term stability of defect-modified ceramics under varying temperature conditions. Additionally, the transformative application of digital twin technologies offers opportunities for intelligent, real-time process optimization. Additionally, not only the small/large signal d33, Qm, kp, and dielectric loss, but also their key properties, require excellent stability for full commercialization, which should be a focus of future research.

Recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have shown great potential in accelerating the discovery and optimization of lead-free piezoceramics. By learning from large datasets of composition-property relationships, ML models can effectively predict optimal doping strategies, phase stability, and functional performance, thereby minimizing reliance on labor-intensive trial-and-error experimentation. In particular, the combination of high-throughput experimentation with AI-driven design has emerged as a powerful approach for the rapid identification of novel material systems with enhanced performance and thermal stability.

From a processing perspective, advanced manufacturing techniques such as flash sintering, cold sintering, and spark plasma sintering present promising avenues for tailoring the microstructure of lead-free ceramics. These methods facilitate low-temperature densification, precise grain size control, and shortened processing time, all of which are crucial for preserving the sensitive defect chemistries and ensuring reproducible performance in compositionally complex systems.

In parallel, multi-scale computational modeling provides critical insights into the fundamental mechanisms underlying structure-property relationships. First-principles calculations based on density functional theory enable atomic-scale understanding of defect formation, polarization behavior, and phase stability. Complementarily, phase-field simulations capture mesoscopic domain evolution and electromechanical responses under various thermal and electrical boundary conditions. The integration of experimental investigations with advanced modeling and data-driven approaches holds significant potential for the rational design of high-performance, temperature-stable lead-free piezoceramics.

Additionally, the development of advanced characterization techniques will be crucial. In situ TEM and synchrotron X-ray diffraction should be utilized to directly observe phase transition dynamics and local structural distortions under coupled electric field and temperature conditions. This approach will offer deeper insights into the mechanisms governing temperature stability. Future research should also focus on enhancing the environmental adaptability of KNN-based ceramics, particularly for extreme conditions such as deep space cryogenic environments or nuclear radiation exposure. By integrating state-of-the-art processing methods, theoretical modeling, and advanced characterization techniques, KNN-based lead-free piezoceramics can evolve from laboratory-scale innovations to industrial applications, ultimately offering a viable alternative to lead-based systems and contributing to both environmental sustainability and technological advancement.

CONCLUSIONS

This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in improving the piezoelectric performance and temperature stability of KNN-based lead-free ceramics through microstructural engineering [Table 1]. Core strategies, including diffuse phase transition with multiphase coexistence, polar nanoregions, engineered domain structures, multilayer and composition-graded architectures, atomic-scale structural design, and defect modulation, fundamentally function by stabilizing the polymorphic phase transition and mitigating temperature-driven structural fluctuations. Together, these approaches highlight the central role of phase evolution, domain behavior, and defect chemistry in governing temperature-dependent piezoresponse. Looking forward, continued progress will rely on integrating microstructural design with advanced characterization, modeling, and data-driven methods to guide the development of robust, practically viable KNN-based piezoceramics.

Summary of various compositional modifications and strategies for enhancing the performance and temperature stability of KNN-based ceramics

| Strategy | Composition | Temperature range | Room temperature d33/d33* | Fluctuation | Ref. |

| Diffuse phase transition | 0.93(Li0.025Na0.52K0.455)(Nb0.975,Sb0.025)O3-0.05BaZrO3-0.02(Bi0.5Na0.5)HfO3-0.01MnO2 | 20-100 °C | 510 pC N-1 | 23.5% | [29] |

| 0.94(Na0.56K0.44)NbO3-0.03Bi0.5Na0.5ZrO3-0.03(Bi0.5K0.5)HfO3 | 25-250 °C | 550 pC N-1 | 10.0% | [30] | |

| Multilayer | (1-x)(K0.48Na0.52)(Nb0.955Sb0.045)O3-xBi0.5Na0.5ZrO3-0.2%Fe2O3 (x = 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04) | 25-112 °C | 330 pC N-1 | 6.0% | [33] |

| (LixNa0.52K0.48-x)(Nb1-ySby)O3-BaZrO3-(Bi0.5Na0.5)HfO3-0.01MnO2 (x = y = 0.025, x = 0.01, y = 0.02, x =y = 0) | 25-150 °C | 508 pC N-1 | 13.0% | [31] | |

| Polar nanoregions | 0.96((K0.5Na0.5)(Nb0.98Ta0.02)O3)-0.01(Bi(Ni0.67Nb0.33)O3)-0.03(Bi0.5K0.5)HfO3 | 25-200 °C | 331 pC N-1 | 10.0% | [56] |

| 0.93(Na0.52, K0.48)(Nb0.975, Sb0.025)O3-0.05BaZrO3-0.02(Bi0.5, Na0.5)HfO3-1 wt% MnO2 | 25-100 °C | 600 pm V-1 | 1.7% | [57] | |

| Domain engineering | 0.964K0.4Na0.6Nb0.955Sb0.045O3-0.006BiFeO3-0.03Bi0.5Na0.5ZrO3 | 23-80 °C | 570 pm V-1 | 3% | [89] |

| Atomic-scale structure design | 0.945KNN-0.055(Bi0.5K0.5)0.64Ba0.36ZrO3 | 25-100 °C | 430 pC N-1 | 7% | [40] |

| Defect engineering | 0.95(K0.45Na0.55)NbO3-0.05Bi0.5Na0.5HfO3 (KNN-BNH)-0.05Fe | 20-140 °C | 300 pm V-1 | 15% | [35] |

| 0.94(K0.48Na0.52)NbO3-0.06LiTaO3-0.02Cu | 25-100 °C | 133 pm V-1 | 27.5% | [37] | |

| Lead-based | PZT-4 | 22-140 °C | 700 pm V-1 | 14.3% | [39] |

| PZT-5H | 25-80 °C | 730 pm V-1 | 12.3% | [117] |

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Original draft preparation, reviewing, and editing: Tian, S.; Zhao, Z.; Dai, Y.

Supervision, conceptualization, validation, project administration, funding acquisition: Zhao, Z.; Li, B.;

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA0716500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52172135, 52302214), the Youth Top Talent Project of the National Special Support Program (2021-527-07), the Leading Talent Project of the National Special Support Program (2022WRLJ003), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2252061), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (2022B1515020070 and 2021B1515020083), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20240813151421028), the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program for Ph.D Student by CAST.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Zhou, X.; Xue, G.; Luo, H.; Bowen, C. R.; Zhang, D. Phase structure and properties of sodium bismuth titanate lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 122, 100836.

2. Hao, J.; Li, W.; Zhai, J.; Chen, H. Progress in high-strain perovskite piezoelectric ceramics. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 2019, 135, 1-57.

3. Li, F.; Lin, D.; Chen, Z.; et al. Ultrahigh piezoelectricity in ferroelectric ceramics by design. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 349-54.

4. Wei, H.; Wang, H.; Xia, Y.; et al. An overview of lead-free piezoelectric materials and devices. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2018, 6, 12446-67.

5. Shrout, T. R.; Zhang, S. J. Lead-free piezoelectric ceramics: alternatives for PZT? J. Electroceram. 2007, 19, 113-26.

6. Zheng, T.; Wu, H.; Yuan, Y.; et al. The structural origin of enhanced piezoelectric performance and stability in lead free ceramics. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 528-37.

7. Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Qi, H.; Chen, J. High-electromechanical performance for high-power piezoelectric applications: Fundamental, progress, and perspective. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 127, 100944.

8. Maeder, M. D.; Damjanovic, D.; Setter, N. Lead free piezoelectric materials. J. Electroceram. 2004, 13, 385-92.

10. Xiao, D. Q.; Wu, J. G.; Wu, L.; et al. Investigation on the composition design and properties study of perovskite lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 5408-19.

11. Qin, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, X.; et al. Investigation of BiFeO3-BaTiO3 lead-free piezoelectric ceramics with nonstoichiometric bismuth. Microstructures 2023, 3, 2023235.

12. Wu, J.; Xiao, D.; Zhu, J. Potassium-sodium niobate lead-free piezoelectric materials: past, present, and future of phase boundaries. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2559-95.

13. Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Guo, W.; et al. Effect of A and B-site ion doping on the structure and properties of KNN-based ceramic coatings. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 37809-19.

14. Lv, X.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, X. Temperature stability and electrical properties in La-doped KNN-based ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101, 4084-94.

15. Liu, D.; Zhu, L. F.; Tang, T.; et al. Textured potassium sodium niobate lead-free ceramics with high d33 and Qm for meeting high-power applications. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 7444-52.

16. Liu, Y.; Thong, H.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, K. Defect-mediated domain-wall motion and enhanced electric-field-induced strain in hot-pressed K0.5Na0.5NbO3 lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. J. App. Phys. 2021, 129, 024102.

17. Lv, X.; Wu, J.; Xiao, D.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X. Structural evolution of the R-T phase boundary in KNN -based ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101, 1191-200.

18. Cen, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Feng, W.; et al. Improving piezoelectric properties and temperature stability for KNN-based ceramics sintered in a reducing atmosphere. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101, 4108-17.

19. Cheng, Y.; Xing, J.; Li, X.; et al. Meticulously tailoring phase boundary in KNN-based ceramics to enhance piezoelectricity and temperature stability. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 5213-21.

20. Cen, Z.; Bian, S.; Xu, Z.; et al. Simultaneously improving piezoelectric properties and temperature stability of Na0.5K0.5NbO3 (KNN)-based ceramics sintered in reducing atmosphere. J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 820-31.

21. Peng, Z.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, F.; et al. A new family of high temperature stability and ultra-fast charge-discharge KNN-based lead-free ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 9992-10002.

22. Qi, X.; Ren, P.; Tong, X.; Wang, X.; Zhuo, F. Enhanced piezoelectric properties of KNN-based ceramics by synergistic modulation of phase constitution, grain size and domain configurations. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 116874.

23. Gao, S.; Li, P.; Qu, J.; et al. Crystallographic texture and phase structure induced excellent piezoelectric performance in KNN-based ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 106, 3481-90.

24. Liu, Z.; Cai, W.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Dielectric and ferroelectric properties of knn ceramics fabricated by microwave sintering. J. Electron. Mater. 2024, 53, 7170-8.

25. Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Lv, X.; Wu, J. Multiscale understanding the effect of K/Na ratio on electrical properties of high-performance KNN-based ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 355-66.

26. Wang, C.; Fang, B.; Qu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ding, J. Preparation of KNN based lead-free piezoelectric ceramics via composition designing and two-step sintering. J. Alloys. Compd. 2020, 832, 153043.

27. Li, K.; Cong, S.; Bian, L.; et al. Simultaneous enhancement of piezoelectricity and temperature stability in Pb(Ni1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbZrO3-PbTiO3 piezoelectric ceramics via Sm-modification. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 1578-89.

28. Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Zhao, L.; et al. Niobate-based lead-free piezoceramics: a diffused phase transition boundary leading to temperature-insensitive high piezoelectric voltage coefficients. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2018, 6, 1116-25.

29. Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; et al. Practical high-performance lead-free piezoelectrics: structural flexibility beyond utilizing multiphase coexistence. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 355-65.

30. Xu, L.; Lin, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. Ultrahigh thermal stability and piezoelectricity of lead-free KNN-based texture piezoceramics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9018.

31. Song, A.; Liu, Y.; Feng, T.; et al. Simultaneous enhancement of piezoelectricity and temperature stability in KNN-based lead-free ceramics via layered distribution of dopants. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2204385.

32. Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zheng, T.; Wu, J. Simultaneous realization of good piezoelectric and strain temperature stability via the synergic contribution from multilayer design and rare earth doping. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2211439.

33. Zheng, T.; Yu, Y.; Lei, H.; et al. Compositionally graded KNN-based multilayer composite with excellent piezoelectric temperature stability. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2109175.

34. Li, P.; Gao, S.; Lu, G.; et al. Significantly enhanced piezoelectric temperature stability of KNN-based ceramics through multilayer textured thick films composite. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 3861-8.

35. Li, R.; Sun, X.; Lv, X.; Zheng, T.; Wu, J. Manipulating temperature stability in KNN-based ceramics via defect design. Acta. Materialia. 2021, 218, 117229.

36. Sun, X.; Li, R.; Zhao, C.; Lv, X.; Wu, J. One simple approach, two remarkable enhancements: manipulating defect dipoles and local stress of (K, Na)NbO3-based ceramics. Acta. Mater. 2021, 221, 117351.

37. Tian, S.; Xin, J.; Cheng, Y.; Lai, L.; Li, B.; Dai, Y. Strong pinning effect on domains in piezoelectrics. Acta. Mater. 2024, 280, 120344.

38. Egerton, L.; Dillon, D. M. Piezoelectric and dielectric properties of ceramics in the system potassium - sodium niobate. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1959, 42, 438-42.

40. Zou, J.; Song, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. Enhancing piezoelectric coefficient and thermal stability in lead-free piezoceramics: insights at the atomic-scale. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8591.

41. Dai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, G. Phase transitional behavior in K0.5Na0.5NbO3-LiTaO3 ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 262903.

42. Du, X.; Zheng, J.; Belegundu, U.; Uchino, K. Crystal orientation dependence of piezoelectric properties of lead zirconate titanate near the morphotropic phase boundary. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 72, 2421-3.

43. Randall, C. A.; Kim, N.; Kucera, J.; Cao, W.; Shrout, T. R. Intrinsic and extrinsic size effects in fine-grained morphotropic-phase-boundary lead zirconate titanate ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1998, 81, 677-88.

44. Ahart, M.; Somayazulu, M.; Cohen, R. E.; et al. Origin of morphotropic phase boundaries in ferroelectrics. Nature 2008, 451, 545-8.

45. Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, F. Morphotropic phase boundary-like properties in a ferroelectric-paraelectric nanocomposite. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 126, 124102.

46. Feng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Enhanced electrocaloric effect in KNN-based ceramic via polymorphic phase transition. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 1788-94.

47. Huan, Y.; Wei, T.; Wang, Z.; Lei, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, X. Polarization switching and rotation in KNN-based lead-free piezoelectric ceramics near the polymorphic phase boundary. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 1002-10.

48. Liu, G.; Kong, L.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, S. Diffused morphotropic phase boundary in relaxor-PbTiO3 crystals: high piezoelectricity with improved thermal stability. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2020, 7, 021405.

49. Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Shen, B.; Zhai, J. Effect of orthorhombic-tetragonal phase transition on structure and piezoelectric properties of KNN-based lead-free ceramics. Dalton. Trans. 2015, 44, 7797-802.

50. Zhao, C.; Yin, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J. Polymorphic characteristics challenging electrical properties in lead-free piezoceramics. Dalton. Trans. 2019, 48, 11250-8.

51. Li, B.; Xiong, C.; Cao, X.; Wei, X.; Qiu, Y.; Gao, D. Temperature stability of multilayer symmetric KNN-based ceramics with continuous phase transitions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 031901.

52. Zhai, Y.; Du, J.; Chen, C.; et al. Temperature stability and electrical properties of Tm2O3 doped KNN-based ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 4716-25.

53. Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Lv, X.; et al. Understanding the piezoelectricity of high-performance potassium sodium niobate ceramics from diffused multi-phase coexistence and domain feature. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 16803-11.

54. Yao, F.; Wang, K.; Jo, W.; et al. Diffused phase transition boosts thermal stability of high-performance lead-free piezoelectrics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 1217-24.

55. Wang, K.; Yao, F.; Jo, W.; et al. Temperature-insensitive (K,Na)NbO3-based lead-free piezoactuator ceramics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 4079-86.

56. Hua, Y.; Qian, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. Broad temperature plateau for high piezoelectric coefficient by embedding PNRs in singe-phase KNN-based ceramics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2414348.

57. Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; et al. High-performance lead-free piezoelectrics with local structural heterogeneity. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 3531-9.

58. Zheng, T.; Wu, J.; Xiao, D.; Zhu, J. Recent development in lead-free perovskite piezoelectric bulk materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 98, 552-624.

59. Wang, K.; Li, J. (K, Na)NbO3-based lead-free piezoceramics: phase transition, sintering and property enhancement. J. Adv. Ceram. 2012, 1, 24-37.

60. Hou, J.; Dai, Z.; Liu, C.; Yasui, S.; Cong, Y.; Gu, S. Enhanced photoelectric properties for BiZn0.5Zr0.5O3 modified KNN-based lead-free ceramics. J. Alloys. Compd. 2023, 960, 170639.

61. Wang, R.; Wang, K.; Yao, F.; et al. Temperature stability of lead-free niobate piezoceramics with engineered morphotropic phase boundary. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 98, 2177-82.

62. Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Simultaneous enhancement of piezoelectricity and temperature stability in (K,Na)NbO3-based lead-free piezoceramics by incorporating perovskite zirconates. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2018, 6, 10618-27.

63. Zhang, M. H.; Wang, K.; Du, Y. J.; et al. High and Temperature-Insensitive Piezoelectric Strain in Alkali Niobate Lead-free Perovskite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3889-95.

64. Qin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yao, W.; Lu, C.; Zhang, S. Domain configuration and thermal stability of (K0.48Na0.52)(Nb0.96Sb0.04)O3-Bi0.50(Na0.82K0.18)0.50ZrO3Piezoceramics with High d33 coefficient. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016, 8, 7257-65.

65. Liu, B.; Li, P.; Shen, B.; et al. Simultaneously enhanced piezoelectric response and piezoelectric voltage coefficient in textured KNN-based ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101, 265-73.

66. Zhou, J.; Wang, K.; Yao, F.; et al. Multi-scale thermal stability of niobate-based lead-free piezoceramics with large piezoelectricity. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2015, 3, 8780-7.

67. Guan, S.; Yang, H.; Cheng, S.; et al. Phase structure, domain structure, thermal stability, and high-temperature piezoelectric response of BiFeO3-BaTiO3 lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 384-93.

68. Shvartsman, V. V.; Kholkin, A. L.; Orlova, A.; Kiselev, D.; Bogomolov, A. A.; Sternberg, A. Polar nanodomains and local ferroelectric phenomena in relaxor lead lanthanum zirconate titanate ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 202907.

69. Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, P.; et al. Simultaneous achievement of large strain, low hysteresis, and high-temperature stability in textured BT-based piezoelectric ceramics. J. Adv. Ceram. 2025, 14, 9221025.

70. Li, P.; Zhai, J.; Shen, B.; et al. Ultrahigh piezoelectric properties in textured (K,Na)NbO3 -based lead-free ceramics. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705171.

71. Jia, P.; Zheng, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y. The achieving enhanced piezoelectric performance of KNN-based ceramics: decisive role of multi-phase coexistence induced by lattice distortion. J. Alloys. Compd. 2023, 930, 167416.

72. Li, T.; Liu, C.; Ke, X.; et al. High electrostrictive strain in lead-free relaxors near the morphotropic phase boundary. Acta. Mater. 2020, 182, 39-46.

73. Sun, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, L.; et al. Role of tetragonal distortion on domain switching and lattice strain of piezoelectrics by in-situ synchrotron diffraction. Scr. Mater. 2021, 194, 113627.

74. Xu, G.; Wen, J.; Stock, C.; Gehring, P. M. Phase instability induced by polar nanoregions in a relaxor ferroelectric system. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 562-6.

75. Roukos, R.; Zaiter, N.; Chaumont, D. Relaxor behaviour and phase transition of perovskite ferroelectrics-type complex oxides

76. Qian, J.; Yu, Z.; Ge, G.; et al. Topological vortex domain engineering for high dielectric energy storage performance. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2024, 14, 2303409.

77. Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, R.; et al. Tailoring micro-structure of eco-friendly temperature-insensitive transparent ceramics achieving superior piezoelectricity. Acta. Mater. 2022, 235, 118061.

78. Zhao, L.; Gao, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, J. F. Silver niobate lead-free antiferroelectric ceramics: enhancing energy storage density by B-site doping. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018, 10, 819-26.

79. Lin, L.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Bai, W.; Li, W.; Zhai, J. Boosting capacitive performance of lead-free relaxor ferroelectrics by introducing a linear dielectric. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 829-37.

80. Rossetti, G. A.; Khachaturyan, A. G.; Akcay, G.; Ni, Y. Ferroelectric solid solutions with morphotropic boundaries: vanishing polarization anisotropy, adaptive, polar glass, and two-phase states. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 114113.

81. Sluka, T.; Tagantsev, A. K.; Damjanovic, D.; Gureev, M.; Setter, N. Enhanced electromechanical response of ferroelectrics due to charged domain walls. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 748.

82. Catalan, G.; Seidel, J.; Ramesh, R.; Scott, J. F. Domain wall nanoelectronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 119-56.

83. Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Yang, T.; et al. The origin of ultrahigh piezoelectricity in relaxor-ferroelectric solid solution crystals. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13807.

84. Westphal, V.; Kleemann, W.; Glinchuk, M. Diffuse phase transitions and random-field-induced domain states of the ‘‘relaxor’’ferroelectric PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 847.

85. Zheng, T.; Wu, J. Electric field compensation effect driven strain temperature stability enhancement in potassium sodium niobate ceramics. Acta. Mater. 2020, 182, 1-9.

86. Luo, B.; Feng, W.; Dai, S.; Song, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. Stabilizing oxygen vacancies and promoting electrostrain in lead-free potassium niobate-based piezoelectrics over wide temperature ranges. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 1965-73.

87. Gao, J.; Xue, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Microstructure basis for strong piezoelectricity in Pb-free Ba(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3-(Ba0.7Ca0.3)TiO3 ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 092901.

88. Xu, K.; Li, J.; Lv, X.; et al. Superior piezoelectric properties in potassium-sodium niobate lead-free ceramics. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 8519-23.

89. Zhao, C.; Wu, B.; Wang, K.; et al. Practical high strain with superior temperature stability in lead-free piezoceramics through domain engineering. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018, 6, 23736-45.

90. Lv, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J. Nano-domains in lead-free piezoceramics: a review. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 10026-73.

91. Zhao, C.; Gao, S.; Yang, T.; et al. Precipitation hardening in ferroelectric ceramics. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2102421.

92. Damjanovic, D. Contributions to the piezoelectric effect in ferroelectric single crystals and ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2005, 88, 2663-76.

93. Zhang, W.; Bhattacharya, K. A computational model of ferroelectric domains. Part I: model formulation and domain switching. Acta. Mater. 2005, 53, 185-98.

94. Nagarajan, V.; Roytburd, A.; Stanishevsky, A.; et al. Dynamics of ferroelastic domains in ferroelectric thin films. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 43-7.

95. Zhao, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X. A rational designed multi-layered structure to improve the temperature stability of Li modified (K,Na)NbO3 piezoceramics. J. Alloys. Compd. 2018, 731, 39-43.

96. Zeng, S.; Zou, J.; Song, M.; et al. The mechanism for the enhanced piezoelectricity, dielectric property and thermal stability in (K,Na)NbO3 ceramics. Acta. Mater. 2025, 287, 120801.

97. Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Bowen, C. Piezoelectric effects and electromechanical theories at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 13314-27.

98. Fulton C, Gao H. Effect of local polarization switching on piezoelectric fracture. J. Mechan. Phys. Solids. 2001, 49, 927-52.

99. Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Damjanovic, D.; Chen, L.; Shrout, T. R. Local structural heterogeneity and electromechanical responses of ferroelectrics: learning from relaxor ferroelectrics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1801504.

100. Zhang, Y.; Qi, H.; Sun, S.; et al. Ultrahigh piezoelectric performance benefiting from quasi-isotropic local polarization distribution in complex lead-based perovskite. Nano. Energy. 2022, 104, 107910.

101. Rödel, J.; Webber, K. G.; Dittmer, R.; Jo, W.; Kimura, M.; Damjanovic, D. Transferring lead-free piezoelectric ceramics into application. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 1659-81.

102. Lv, X.; Zhu, J.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, X. X.; Wu, J. Emerging new phase boundary in potassium sodium-niobate based ceramics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 671-707.

103. Zhang, S.; Xia, R.; Shrout, T. R.; Zang, G.; Wang, J. Piezoelectric properties in perovskite 0.948(K0.5Na0.5)NbO3-0.052LiSbO3 lead-free ceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100, 104108.

105. Wang, Z.; Xiao, D.; Wu, J.; et al. New lead-free (1-x)(K0.5Na0.5)NbO3-x(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3 ceramics with high piezoelectricity. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 97, 688-90.

106. Batra, K.; Sinha, N.; Kumar, B. Lead-free 0.95(K0.6Na0.4)NbO3-0.05(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3 ceramic for high temperature dielectric, ferroelectric and piezoelectric applications. J. Alloys. Compd. 2020, 818, 152874.

107. Lv, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X. Reduced degree of phase coexistence in KNN-Based ceramics by competing additives. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 2945-53.

108. Yao, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, C.; Liu, D.; Su, W. Giant piezoelectricity, rhombohedral-orthorhombic-tetragonal phase coexistence and domain configurations of (K,Na)(Nb,Sb)O3-BiFeO3-(Bi, Na)ZrO3 ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 1223-31.

109. Li, P.; Fu, Z.; Wang, F.; et al. High piezoelectricity and stable output in BaHfO3 and (Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3 modified

110. Liu, Q.; Pan, E.; Liu, F.; Li, J. (K,Na)NbO3-based lead-free ceramics with enhanced temperature-stable piezoelectricity and efficient red luminescence. J. Adv. Ceram. 2023, 12, 373-85.

111. Tian, S.; Li, B.; Dai, Y. Distinguishing electrotensile strain and electrobending strain. J. Adv. Ceram. 2025, 14, 9221048.

112. Ren, X. Large electric-field-induced strain in ferroelectric crystals by point-defect-mediated reversible domain switching. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 91-4.

113. Huang, Y.; Tian, S.; Feng, M.; et al. The unipolarity formed in the CuO-doped (K0.48Na0.52)0.96Li0.04Nb0.95Ta0.05O3 ceramics. Mater. Lett. 2021, 283, 128825.

114. Tian, S.; Li, B.; Dai, Y. Defect dipole asymmetry response induces electrobending deformation in thin piezoceramics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 186802.

115. Liao, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, Q.; Lin, D. Modulation of defects and electrical behaviors of Cu-doped KNN ceramics by fluorine-oxygen substitution. Dalton. Trans. 2020, 49, 1311-8.

116. Hong, Z.; Ke, X.; Wang, D.; Yang, S.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y. Role of point defects in the formation of relaxor ferroelectrics. Acta. Mater. 2022, 225, 117558.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].