Information processing by digitalizing confined ion transport

Abstract

Ion transport under Ångström-scale confinement exhibits discontinuous and stochastic dynamics, inherently encoding information beyond merely transporting masses and charges. This capability has sparked growing interest in iontronics, a field aiming to harness ions as information carriers akin to biological systems. In contrast to electrons, which dominate modern electronics through high-speed switching at electron-volt energy scales, ions operate near the thermal energy scale (~ kBT). Their diverse sizes, solvation characteristics, and interaction with the channels promise low-energy processing by leveraging thermal fluctuations. Here we investigate digitalized ion flow (the ‘ionbit’) using molecular dynamics simulations of single-file transport through Ångström-scale single-walled carbon nanotubes. By shaping the free-energy landscape of ion transport, we functionalize nanotube entrances and interconnect them via nanoscale pockets that regulate kinetics through a hopping-and-diffusion mechanism. Specifically, ion accumulation, dissipation, and sorption processes in the pocket emulate synaptic integration, leakage, and firing events, while intrinsically embedding a memory function analogous to biological systems. Governed by kBT-level physics, this spiking neural network operates at ultralow energy cost, positioning iontronic circuits as a promising substrate for energy-efficient neuromorphic computation. We further discuss the key challenges that must be overcome to translate nanofluidic iontronic networks into scalable technologies, including precise assembly, robustness, and manufacturability.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The human brain performs complex computations with an estimated power consumption of only about 20 watts[1], an efficiency that vastly surpasses modern supercomputers. This efficiency arises from the precise regulation of ions, which act as the fundamental information carriers, through protein-based biological nanochannels[2-4]. In biological systems, neurons process and transmit information by spike trains with membrane potential-controlled movement of ions such as sodium[5], potassium[6], and calcium[7] across the cell membrane. An action potential (AP) arriving at the presynaptic terminal triggers the exocytosis of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft, which then bind to postsynaptic receptors and induce gating of ion channels, generating graded postsynaptic potentials (PSPs). The neuron integrates these PSPs via spatio-temporal summation. If the integrated potential at the axon hillock reaches the threshold, a new AP is fired, completing the signal transmission. The efficacy of this transmission is governed by synaptic weights. Biologically, this neural connectivity relies on structural wiring to establish reconfigurable pathways of information processing, while synaptic plasticity enables dynamic weight updates for learning. Inspired by this natural model of local learning rules, iontronics utilizes ions, rather than electrons, as signal carriers to develop devices for sensing[8], computing[9], and energy harvesting[10]. Operating at the thermal energy scale (~ kBT)[11], iontronics offers significant potential for biocompatibility, chemical sensing, and ultra-low power consumption[12]. Such systems could help integrate devices with biological organisms, potentially enhancing or even replacing traditional electronics that face significant challenges in biocompatibility and seamless ionic communication with biological tissues[13].

To emulate these biological principles in artificial systems, researchers primarily employ two neuromorphic computing algorithms. Artificial neural networks (ANNs)[14] operate through computationally intensive matrix multiplications of continuous-valued activations. Spiking neural networks (SNNs)[15] utilize discrete event-driven signaling to achieve superior energy efficiency. While iontronics provides a physical substrate compatible with this neuromorphic logic, practical implementation is currently impeded by the diffusive limits of ionic transport. Consequently, the field faces significant challenges[16] regarding low switching speeds[17], operational instability[18], and the complexities of high-density device integration[19].

Seminal progress in iontronics has heavily focused on emulating synaptic functions by constructing various memristors[20-23]. While these devices successfully demonstrate plasticity by modulating conductance[24], they fundamentally lack the capability for active neuronal signal transmission. Contemporary iontronic systems generally depend on external voltage modulation to induce ionic flux through interfacial electron-ion conversion. By lacking the capacity for intrinsic ionic spike generation, these systems decouple the physical mechanisms necessary for autonomous inter-device signaling. This reliance on external control precludes the development of functional iontronic networks with significant spatial or hierarchical complexity, largely confining existing research to isolated, single-layer demonstrations. Therefore, developing active iontronic units capable of all-or-none spiking remains the critical prerequisite for enabling true event-driven neuromorphic computing.

The stochastic dynamics inherent to ion transport within Ångström-scale confinement underpins the physical foundation for mimicking biological excitability. Building upon the structural elucidation of natural ion channels[25], pioneering molecular dynamics (MD) studies identified carbon nanotubes (CNTs) as powerful synthetic analogs for these physiological systems[26,27]. These tubular nanostructures offer atomically smooth hydrophobic interfaces that support nearly frictionless transport[28], while specific entrance functionalization permits the precise engineering of the local potential energy landscape. By creating discrete trapping wells, these functional groups effectively regulate the thermodynamics and kinetics of ion sorption[29]. Crucially, the interstitial junction bridging adjacent CNT units creates a confined pocket. This pocket instantiates the physical realization of a synthetic synaptic cleft where the local accumulation of ions dynamically modulates the effective coupling and signal propagation between devices.

Functionally, these devices operate by transducing external analog stimuli into discrete spike sequences, physically realized as single-file ion transport[30]. The resulting output spikes propagate with minimal decay along the CNT interior to downstream units. To formalize this transport process, we introduce the ionbit concept to bridge the gap between continuous nanofluidic physics and discrete neuromorphic computation. An ionbit is defined as a discrete quantum of information and charge, generated by the stochastic pumping of a single ion across an energy barrier within a functionalized CNT channel. Supported by experimental observations of discrete signaling[31,32], this framework digitizes ionic current into stochastic all-or-none events, directly mirroring the binary logic in SNN. It enables the physical realization of neuronal function with minimized energy consumption (theoretically approaching a few kBT per spike), as only one ion is pumped per event. Distinct from previous analog iontronics[33,34], the ionbit acts as a fundamental information carrier for neuronal integration and firing, exploiting thermally activated hopping as a computational framework.

Building upon the conceptual framework of the ionbit, we further contextualize its position by comparing it with other representative information technologies to highlight its distinct advantages [Supplementary Table 1]. Traditional electronics typically operate with an energy dissipation on the order of ~ fJ/bit[35] at room temperature. While single-electron transistors (SETs) significantly reduce this requirement to the eV/bit regime[36], their operational fidelity remains strictly tethered to cryogenic environments to suppress thermal fluctuations. Our single-ion bits (ionbits) achieve a significantly lower energy consumption of ~ kBT/bit to transport ions through a CNT channel. By employing a time-averaged frequency signal to ensure noise resilience, this approach not only reduces energy consumption by several orders of magnitude but also eliminates the need for cryogenic cooling. It enables ultra-low-power operation at room temperature, which plays as a game-changer for green computing.

Within the landscape of low‑power neuromorphic devices, this singular‑carrier mechanism drives its energy consumption toward the thermodynamic limit of ~ kBT per spike, markedly lower than the value of fJ-pJ per spike[37-39] in the devices relying on the movement of charge carriers [Supplementary Table 2]. Information is encoded in discrete firing frequency, making the ionbit inherently compatible with the event‑driven architecture of SNNs, in contrast to the continuous analog modulation employed in most ionic neuromorphic systems. This feature enables ultra-low-power operation near the physical limit, opening a distinct pathway for next‑generation energy‑efficient neuromorphic hardware.

The primary challenge in neuromorphic engineering is transitioning from abstract mathematical models to concrete, physical devices that can be manufactured and integrated into circuits. This paper introduces a theoretical approach aimed at addressing this challenge by exploring possibilities that extend beyond current experimental capabilities. We demonstrate, through extensive MD simulations, the physical realization of a complete leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neuron using the transport of ionbits through a functionalized, Ångström-scale CNT. Building on previous experimental and theoretical discoveries[32,40,41], we identify the interplay between hopping- and diffusion-dominated regimes[42] as the key to regulating ion transport. We deconstruct the physical processes within the device, demonstrating a one-to-one mapping [Supplementary Table 3] of ion accumulation and dissipation in the reservoir, as well as adsorption and desorption near the inlet of the CNT, to the integration and leakage dynamics of the LIF model and quantifying their characteristic timescales. Finally, we establish a logical framework for scaling this single-neuron concept into a functional SNN architecture, constructed by cascading CNT-based neurons via synaptic pockets into a structured grid with defined layer width and sequential depth. We validate its computational versatility through both chaotic time-series prediction[43] and handwritten digit recognition tasks[44], demonstrating the dual capacity for temporal feature extraction and spatial pattern classification. Furthermore, we quantify its robustness against device-to-device heterogeneity and discuss the physical realization of dynamic synaptic learning rules based on the ion ad(de)sorption kinetics, thereby laying the groundwork for adaptive neuromorphic architectures.

EXPERIMENTAL

We investigated ion transport using MD simulations of a functionalized (9,9) CNT (d = 1.22 nm) connecting source and drain reservoirs with 1 mol/L KCl. The specific CNT diameter was selected to enforce single-file transport governed by a dehydration-induced energy barrier [Supplementary Figure 1]. To bridge the timescale discrepancy between atomistic simulations and experimental measurements, electric fields of 0.5-1.0 V/nm were applied as a computational accelerant. This strategy enhances the statistical sampling of rare stochastic hopping events while preserving the intrinsic transport mechanism. Detailed force field parameters and simulation protocols are provided in Supplementary Note 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characteristics of biomimetic iontronic neuron

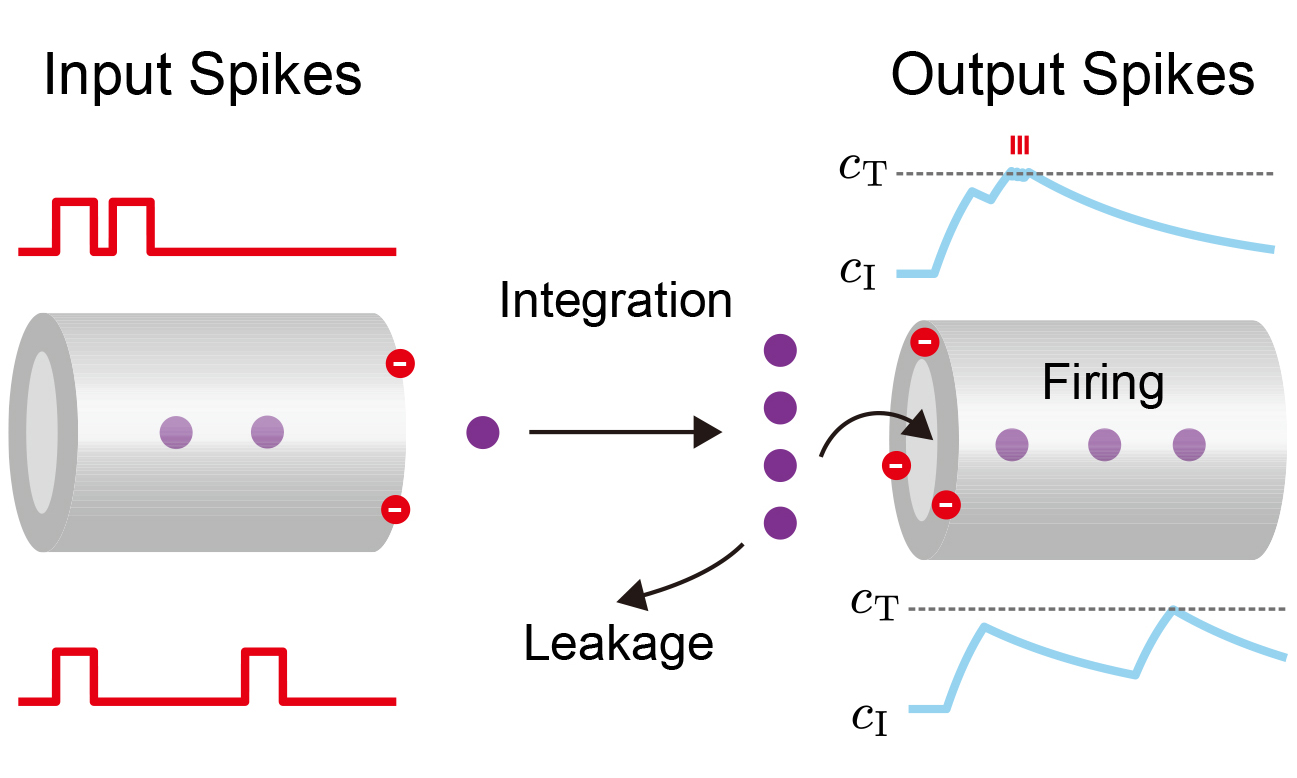

To establish a physical connection between biological and artificial intelligence, we draw a direct analogy at the component level [Figure 1A and B]. In biological systems, presynaptic spikes are weighted and integrated at the soma[45] to generate PSPs. When the accumulation of PSPs causes the membrane potential to exceed a specific threshold (Vthres), the postsynaptic neuron fires an AP that propagates to downstream units[46] [Figure 1A]. Our CNT-based iontronic system physically recapitulates this LIF dynamics, utilizing mass transport variables to membrane voltage operations.

Figure 1. Biomimetic iontronic architecture and ion transport mechanisms. (A) Schematic of a biological synapse and the signaling process. Pre-synaptic spikes are modulated by synaptic weights (W1, W2, W3) and integrated at the soma. The arrival of an AP triggers neurotransmitter release and subsequent Na+ influx, generating PSPs. When the PSPs rise from the resting potential (Vrst) and exceed a threshold (Vthres), the neuron fires a post-spike, transmitting information to downstream dendrites; (B) The CNT-based iontronic neurons and their operation based on the LIF model. Input spikes drive the accumulation of ions, increasing the local concentration (caccum) at the entrance. Without input, ions thermally dissipate, causing the concentration to decay toward the resting state (crst). When caccum exceeds the critical threshold (cthres), the system triggers a stochastic ion transport event, producing a discrete output ionbit; (C) The multi-stage physical process of ion transport. Hydrated ions are trapped by the functionalized entrance, corresponding to the energy well ΔGads. Then ions strip part of their hydration shell to overcome the primary energy barrier at the entrance (ΔGF = ΔGads + ΔGdeh). LIF: Leaky integrate-and-fire; AP: action potential; CNT: carbon nanotube; PSP: postsynaptic potential; ΔGF: the entrance energy barrier; ΔGads: the desorption energy barrier; ΔGdeh: the dehydration energy barrier.

The physical realization of this model relies on the specific energy landscape of ion transport at the Ångström scale. In our architecture [Figure 1B and C], presynaptic voltage pulses drive an ionic flux toward the functionalized CNT entrance. However, ions in the reservoir are thermodynamically stabilized by a hydration shell[47]. As ions approach the channel, the steric confinement imposed by the CNT’s narrow diameter necessitates the partial stripping of this solvation shell[48]. This dehydration requirement imposes a significant energy penalty, creating a dominant free energy barrier (ΔGF) at the entrance that is higher than the activation energy for bulk diffusion[49]. The high entrance barrier (ΔGF) forces ions to accumulate at the entrance, creating a local concentration (caccum) that serves as the physical proxy for the membrane potential. Simultaneously, thermal fluctuations drive the random desorption of ions back to the reservoir, physically representing the leakage term. A firing event occurs only when the accumulated concentration (caccum) surpasses a probabilistic threshold (cthres), sufficiently enhancing the probability of an ion overcoming the inlet energy barrier (ΔGF). This triggers a stochastic, single-file entry event governed by Poisson statistics[32]. Once inside the atomically smooth hydrophobic lumen, the ion experiences near-frictionless dynamics and ultra-fast transport[50]. The sharp contrast between the slow, barrier-limited entry and the ultra-fast transport within the channel is critical. It ensures that ions emerge as distinct ionbit spikes, effectively converting analog inputs into a binary temporal sequence. Ultimately, this deliberate nano-engineering of the energy landscape transforms the CNT from a passive conduit into a sophisticated computational element, capable of physically emulating the complex dynamics of a biological neuron.

Physical basis of neural dynamics

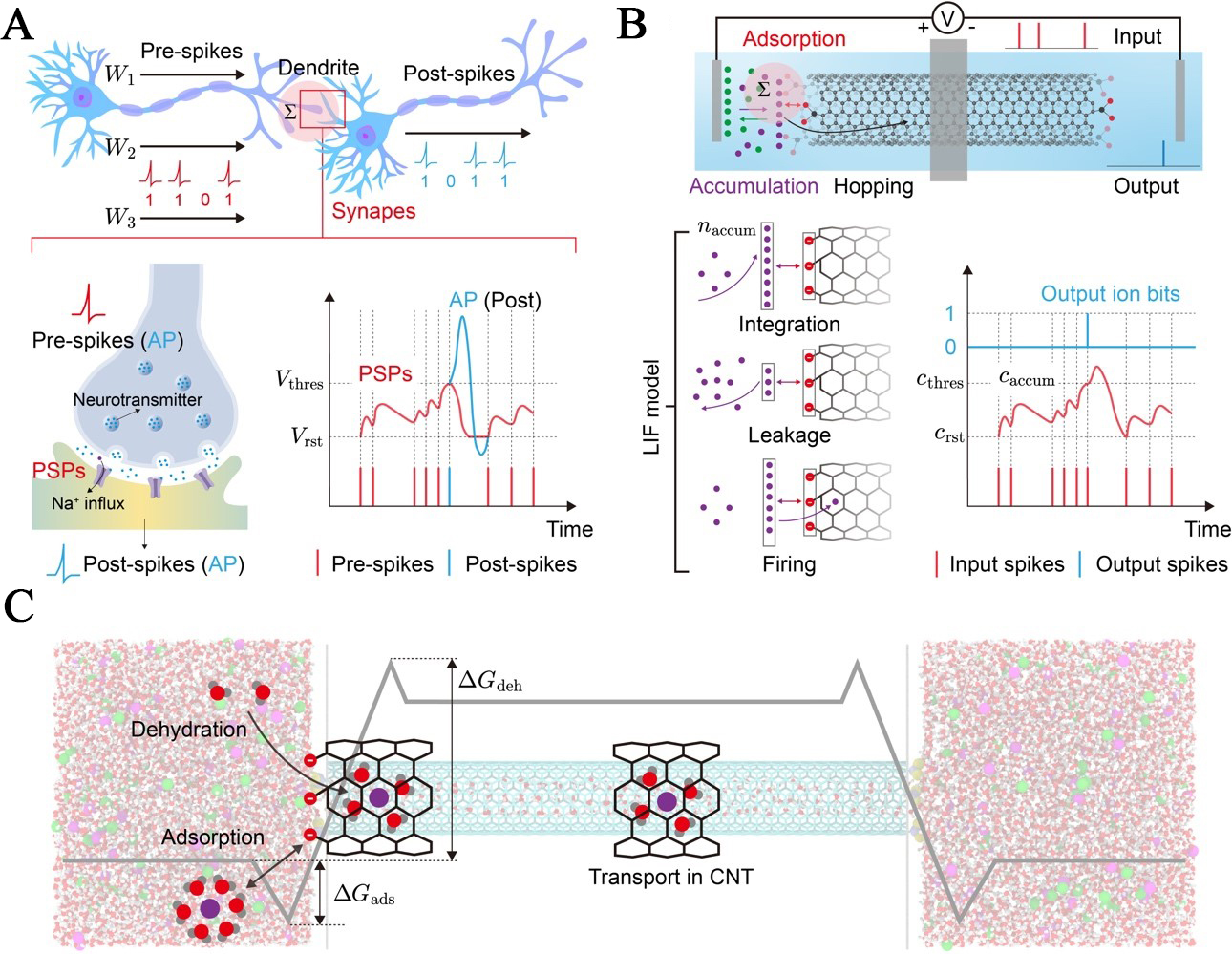

Having established the conceptual framework, we now dissect the physical mechanisms that correspond to the integrate, leak, and fire operations in the CNT-based LIF model without weight update. The fundamental unit of information in our system is the ionbit, defined as the discrete event corresponding to the translocation of a single ion through the CNT channel [Figure 2A]. Under a sustained external electric field (E), MD simulations reveal that the system produces a stochastic train of these ionbits [Figure 2B], the temporal evolution of which provides the physical basis for the LIF model. Specifically, the integrated process is physically substantiated by the field-driven accumulation of ions at the channel entrance. The leakage process is governed by the spontaneous desorption and diffusion of ions back into the bulk reservoir upon the removal of the field. Finally, firing is identified as a threshold-activated transport event, where the accumulated local concentration modulates the entrance energy barrier, triggering a probabilistic ion translocation. In the following sections, we detail the kinetics of these phases based on our MD simulation results and extract their representative parameters.

Figure 2. Physical basis of the integration and leakage dynamics in the iontronic neuron. (A) A (9,9) single-walled CNT with a diameter d(9,9) = 1.22 nm connects two reservoirs containing 1 mol/L KCl solution. An external electric field (E) is applied to drive ion transport, generating discrete ionbits; (B) The timeline is divided into three phases, including integration (ion accumulation without firing), firing (stochastic generation of ionbits under E), and leakage (ion dissipation after E is removed at t = 5 ns); (C) Driven by the field, ions migrate to the accumulation layer and become trapped in the Adsorption region due to the adsorption energy barrier (ΔGads). This process is analogous to charging a capacitor (q vs. t); (D) Probability density of ions near the entrance at different times, showing a clear build-up of concentration under an applied field; (E) Local ion concentration [c(t)] near the CNT entrance as a function of time, fitted to an exponential accumulation model (

The integration phase

When an external electric field is applied, it drives ions from the bulk solution in the reservoir towards the CNT entrance. As shown in Figure 2C, these ions do not immediately enter the nanotube but instead transiently reside in the interfacial pocket (P), which bridges the two neurons (N). This pocket is spatially defined by two distinct zones including a bulk accumulation region (B), where ions gather, and an adsorption region (A) at the entrance, where ions interact strongly with the surface functional groups.

This accumulation is the physical manifestation of the integration step in the LIF model, analogous to the charging of the membrane capacitor. The dynamics of this accumulation process are quantified in Figure 2D and E. The probability density of ions near the entrance shows a clear build-up over time, starting from a baseline at 0 ns and reaching a significantly higher concentration after applying an electric field for 1 ns. By tracking the local ion concentration (c) near the CNT entrance over time [Figure 2E], ions within 1 nm from the entrance, we observe a characteristic charging behavior for capacitors that can be fitted by an exponential function

where c(t) is the ion concentration near the CNT entrance at time t, cT is the ion concentration threshold for firing, and cI is the initial concentration of the pocket.

The fitting yields a characteristic accumulation timescale of τI = 0.15 ns, which is determined by the strength of the driving field, the bulk ion concentration, and the physical properties of the reservoir.

The leakage phase

In a biological neuron, the membrane potential does not hold its value indefinitely without continuous presynaptic signals but leaks away over time. Our iontronic neuron exhibits an analogous behavior. When the external electric field is turned off (at t = 5 ns in our simulation), the electrostatic driving force vanishes. The ions concentrated in the adsorption region are no longer held against the entrance and begin to dissipate back into the bulk solution due to diffusion and electrostatic repulsion [Figure 2F]. This dissipation process is the physical basis for the leakage component of the LIF model [Figure 2G and H]. The local ion concentration near the entrance decays over time [Figure 2G], following an exponential decay curve given by

where c0 is the ion concentration near the CNT entrance at the beginning of the leakage process. The fitting results using our MD simulation data show two leakage processes with different leakage time scales τL. The leakage begins with a fast process with τL, dis = 0.10 ns, which represents a capacitor-like ion dissipation process. Then, a much slower leakage process begins with τL, des = 0.45 ns, which corresponds to the desorption of ions from the adsorption with -COO-. The desorption is a thermally activated process across the energy barrier (ΔGads). Furthermore, we statistically analyzed the distribution of ion desorption times (tdes) from -COO- located at the entrance of the CNT [Figure 2H]. The value of tdes = 1/kdes is exponentially distributed, where the underlying desorption rate is defined by the Eyring-Polanyi expression[51]:

where kB is the Boltzmann constant; T is the temperature; h is the Planck's constant.

The fitting result suggests that the desorption energy barrier is ΔGads = 8.29 kBT.

This detailed analysis reveals a profound connection between the abstract parameters of the LIF model and the tangible, engineerable properties of our CNT-based device. The time constants, τI and τL, govern the integration and leakage of the LIF neuron. Crucially, the timescale τL, des is determined by the desorption energy barrier (ΔGads) and τI and τL, dis is determined by the diffusive dynamics within the pocket, which govern the local ion mobility.

The memory window of the neuron is defined by the interplay between the ion accumulation rate (τI) and the dissipation/desorption rate (τL, dis, τL, des) [Supplementary Table 4]. The slower thermal desorption process

This physical residue inherently leads to short-term plasticity (STP), biologically equivalent to paired-pulse facilitation (PPF). By modulating the sorption strength, the desorption-related leakage (τL, des) can be prolonged, effectively widening the memory window to capture slower temporal patterns.

The temporal resolution is intrinsically linked to these physical time constants. The integration time constant (τI) defines the minimum resolvable time step. A decrease in τI increases the sampling resolution by allowing the neuron to capture high-frequency fluctuations and rapid transients that would otherwise be lost to slower integration. An increase in the leakage constant (τL, des) expands the temporal depth resolution, enabling the system to resolve and integrate long-term dependencies within a widened memory window.

Stochastic firing of ionbits

The neuron’s firing threshold, Vthres, is physically realized as a critical number of accumulated ions, cT, required to create a global control such as ion concentrations or chemical controls that significantly lowers the effective energy barrier for translocation into the CNT, ΔGF. This transforms the LIF model from a purely descriptive tool into a predictive engineering blueprint for designing artificial neurons with specific, tailored computational properties.

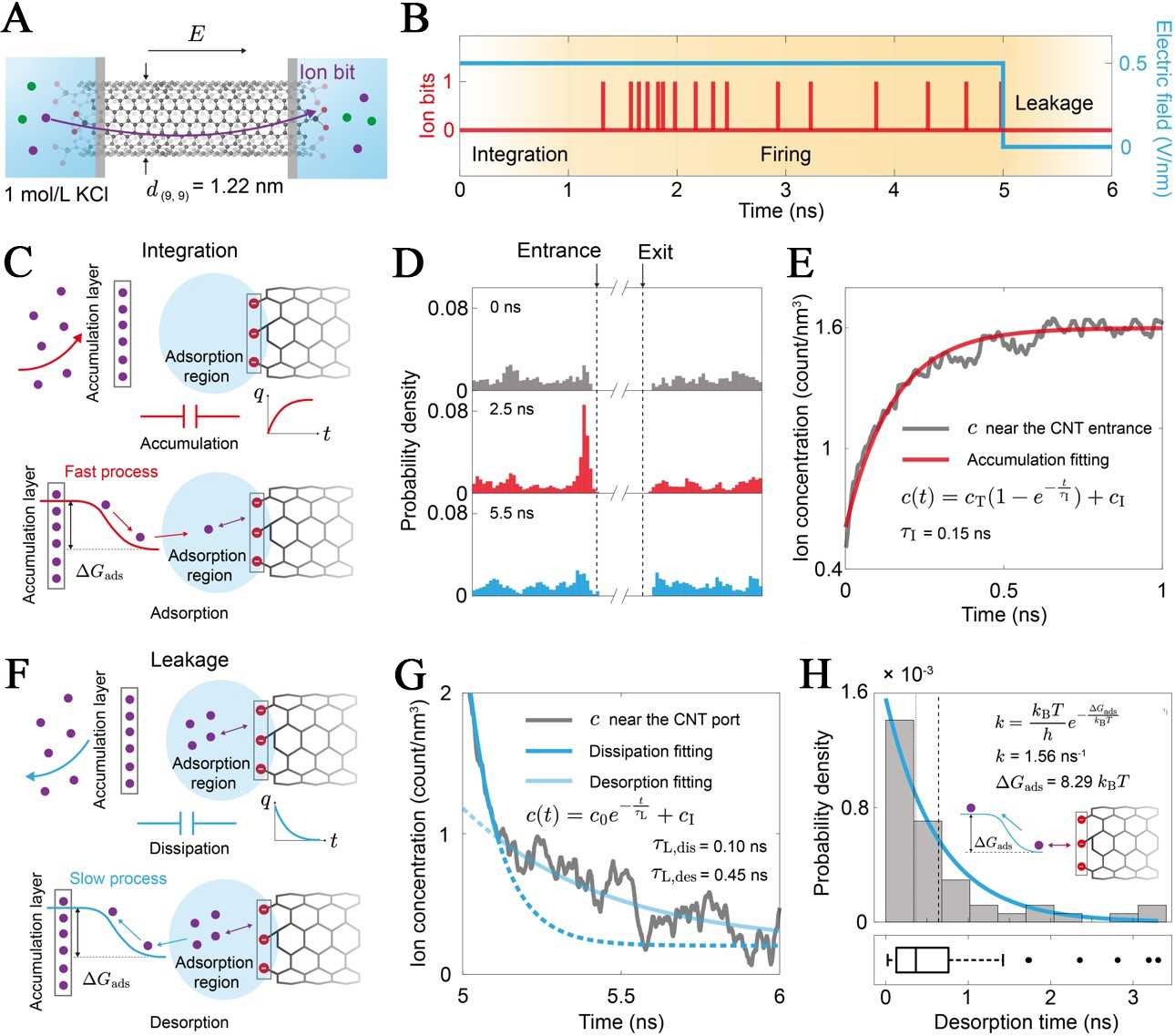

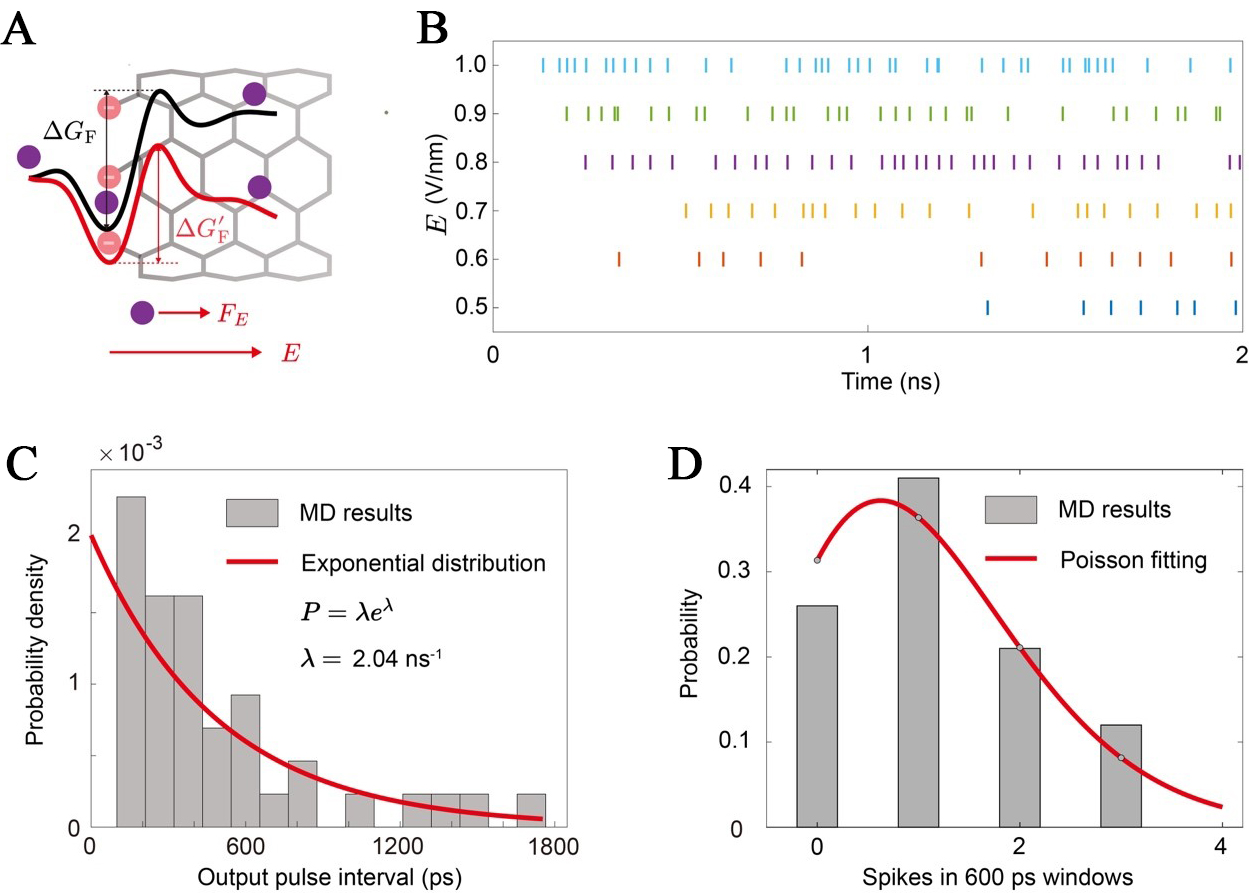

In our MD simulations, the firing process corresponds to the stochastic hopping of an accumulated ion over the primary energy barrier, ΔGF, and its subsequent rapid transport through the CNT. The external electric field applied in the simulations, E, plays a critical role in modulating this process. As depicted in Figure 3A, the applied field exerts a force, FE, on the ion, effectively tilting the energy landscape. This reduces the effective energy barrier that the ion must overcome from ΔGF to a lower value, ΔGF - Ed. A stronger electric field results in a greater reduction of the barrier, thereby increasing the probability of a successful hopping event per unit time. This direct modulation of the firing probability translates into control over the neuron’s firing rate. Figure 3B shows spike raster plots for the iontronic neuron under different electric field strengths. At a low field of E = 0.5 V/nm, the firing is sparse and infrequent. As the field strength increases, the firing becomes progressively more rapid and dense, demonstrating that the output firing rate is continuously tunable by the input stimulus (the external electric field).

Figure 3. Stochastic firing dynamics of iontronic neurons. (A) Schematic of the ion transport energy landscape. Under no external field (top), an ion must overcome the intrinsic firing energy barrier (ΔGF). An applied electric field, E, exerts a force (FE) that effectively tilts the landscape, reducing the barrier to ΔG’F (bottom), thereby increasing the probability of a firing event; (B) Spike raster plots showing output ionbits over a 2 ns window for different applied electric field strengths based on the MD results. As the field strength increases from 0.5 V/nm to 1.0 V/nm, the firing becomes more frequent and denser, demonstrating continuous rate modulation; (C) Probability density distribution of ISIs for electric fields of 0.5 V/nm. The distributions are well-fitted by exponential decay functions, a characteristic signature of a Poisson process; (D) Histogram of the number of spikes observed in 600 ps time windows for an applied field of 0.5 V/nm. The distribution of spike counts is accurately described by a Poisson fit (gray bars), further confirming the stochastic Poisson nature of the neuron’s output. MD: Molecular dynamics; ISI: inter-spike interval.

A hallmark of biological neural activity is its stochastic nature[52], which enhances the robustness of information transmission by allowing the system to encode signals through stable average firing rates rather than being susceptible to the noise of individual spike timing. Our iontronic neuron intrinsically reproduces this essential feature. The firing of an ionbit is a probabilistic event, governed by thermal fluctuations that allow the ion to overcome the energy barrier. To characterize this stochasticity, we analyze the statistics of the output spike train. The probability distribution of the inter-spike intervals (ISIs) [Figure 3C] can be well-described by an exponential decay function, which is the classic signature of a Poisson process[53]. To further confirm this finding, we analyze the distribution of spike counts. The histogram of the number of ionbits that occur within fixed 600 ps time windows for an applied field of 0.5 V/nm can be well fitted by a Poisson distribution [Figure 3D].

This finding is not merely a characterization of device noise but a demonstration of a fundamental computational capability with a kBT-level physics. The observed stochasticity is a functional feature that faithfully mimics the behavior of biological neurons[54]. Information is not encoded in the precise timing of single spikes but in the average firing rate of a neuron over a period of time. Our system provides a direct physical mechanism for this type of rate coding. The external electric field strength, E, acts as an analog input that controls the rate parameter (k) of the output Poisson process

where q is the ionic charge, E is the applied electric field and d is the length of the entrance energy barrier (ΔGF = ΔGads + ΔGdeh, ~ 10 kBT[55]). By engineering the energy barrier within the thermal activation range (~ kBT), the system leverages thermal fluctuations to assist ion hopping, thereby reducing the energy cost of signal transmission to the fundamental limit of a few kBT per spike.

This provides a clear and direct physical basis for implementing updatable synaptic weights in a network with a finite depth. The collective influence of pre-synaptic neurons could modulate the local electric field at the input of a postsynaptic CNT neuron.

Furthermore, the system supports multi-bit transmission (spikes comprising more than one ion), particularly in CNTs with large diameters and under conditions of strong presynaptic stimulation. Importantly, this multi-bit capability does not compromise key advantages of SNNs, including event-driven sparsity and low static power consumption.

Demonstration of SNN applications

By employing CNTs as stochastic spiking neurons and the inter-CNTs fluidic pockets as synaptic junctions, we construct a scalable nanofluidic dynamic device-based reservoir computing (RC). This architecture initiates with an input layer of M parallel CNT encoders that transduce analog stimuli into discrete ionbit sequences, which are projected via a sparse N × M matrix into a dynamic device-based reservoir layer comprising N independent neurons. Within this cascade topology, the performance of learning and prediction is determined by parameters in specific nanofluidic implementation (e.g., nanopores, nanoslits, hetero-gels). In the reservoir layer, the non-linear response and short-term memory are governed by the characteristic timescales of ion integration (τI) and leakage (τL), as well as the effective transport energy barrier (ΔGF). These quantities dictate the dynamics of instantaneous ion concentration accumulation and dissipation at the CNT entrance, optimizing feature extraction capability. In the readout layer, weight update is achieved by the kinetics of ion adsorption and desorption. The temporal correlation between pre- and postsynaptic spikes alters the population of trapped ions at the interface (representing the effective synaptic weight). This variation locally and electrostatically modulates the energy barrier to physically realize spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) for adaptive associative learning.

To achieve a learning framework that is both adaptable and stable, the system enforces a strict physical separation between synaptic weights and neuronal states. The synaptic weight W is encoded in the ion concentration within the adsorption region [cads(t)], which evolves slowly and establishes a quasi-static background conductance. By contrast, the neuronal state is determined by the transient ion concentration in the accumulation region [cacc(t)], which responds rapidly and relaxes through thermal dissipation.

In the proposed neuromorphic architecture, information-theoretic measures provide a rigorous quantitative framework for characterizing the signal processing pipeline from physical encoding to adaptive learning. The entropy rate is physically established at the input layer through the stochastic spike encoding process, where the thermal-fluctuation-driven generation of ionbits transforms continuous analog stimuli into a discrete probabilistic state space that defines the system’s dynamic information capacity. In the readout layer, the STDP rule effectively operates as an information-maximization mechanism that dynamically tunes synaptic weights via ion ad(de)sorption kinetics to maximize the mutual information between the high-dimensional reservoir representations and the target signal.

From nanoscale physics to a single spiking neuron model

Specifically, we construct a physically grounded realization of the LIF model at the single neuron level. We deconstruct ion transport through functionalized CNTs to the integration, leakage, and firing processes in LIF. Central to this, one-to-one mapping is the formalization of the ionbit, a discrete information unit compatible with the event-driven, spiking framework of neuromorphic computing. This concept digitizes the inherently analog process of ionic flow, which can be extended to multi-bit processes.

The integration function of the neuron is physically embodied by the transient accumulation of ions in an adsorption region near the CNT entrance, acting as a capacitor - a process with a measurable characteristic timescale, τI. The leakage function is realized by the thermal desorption of these accumulated ions back into the bulk solution, a process governed by ΔGads, and characterized by two leakage processes. The fast process is governed by the diffusion of accumulated ions, whereas the slow process is associated with the desorption of ions from functional groups at the CNT entrances. Finally, the firing event is the stochastic, thermal-activated hopping of an ion over the primary translocation barrier, ΔGF, a process whose rate is directly and continuously tunable by an applied electric field (E) or chemical potential. The output of this system is a Poisson-distributed train of ionbits, a statistical signature that mirrors the stochastic firing patterns of biological neurons.

Scalable cascade architecture and signal propagation

To facilitate the transition from isolated CNT-based nanofluidic devices to a fully functional SNN, implementing a cascade architecture is a fundamental prerequisite. In this scalable array configuration, the ionic output generated by an upstream (pre-synaptic) CNT unit does not merely dissipate but serves as the requisite accumulation input for downstream (postsynaptic) units. This direct physical coupling mimics the synaptic connectivity of biological neural networks, allowing for the continuous propagation and processing of information across the system. The modulation of ion transport efficiency between these cascaded stages defines the synaptic weight W, which can be modulated by cads(t), providing the fundamental basis for network plasticity and learning.

The circuit operation is governed by two distinct driving mechanisms, selected according to performance requirements. Periodic electrode arrays may be incorporated to generate voltage-driven electrophoretic transport, enabling ultrafast signal propagation at the expense of reduced energy efficiency owing to power dissipation in externally applied electric fields[56]. Alternatively, to strictly adhere to a low-energy budget, the system can adopt a chemical control strategy analogous to biological neurotransmitter release[57]. In this regime, ion transport is mediated by concentration gradients and diffusion. Although this thermodynamic driving force (~ kBT) is weaker than the electrophoretic acceleration, it delivers markedly higher energy efficiency, closely approximating the metabolic economy of biological neural systems.

For large-scale networks, our CNT-based neuron also avoids signal attenuation and dissipative loss. Each CNT functions as a sub-nanometer conduit that strictly restricts ions to a one-dimensional (1D) transport regime. The atomically smooth graphitic lattice of the CNT walls creates a near-frictionless interface for hydrated ions[58]. This structural perfection facilitates barrier-free ionic transport with negligible dissipative loss, ensuring that ion translocation events occur with high fidelity even within large-scale network architectures.

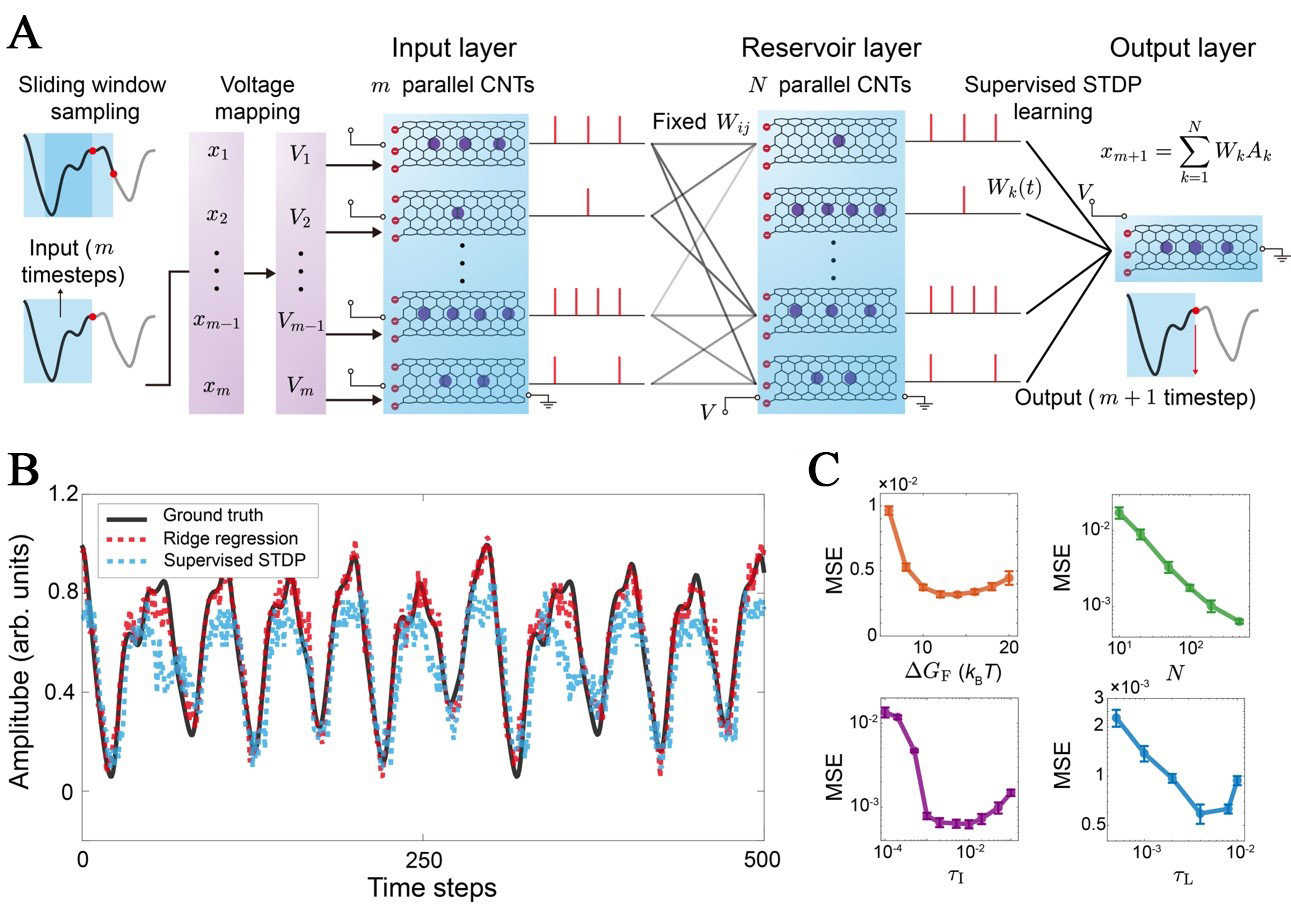

Physical reservoir computing architecture and applications

The dynamic device-based RC architecture[59] processes time-series data through three functional stages: a spike-encoding input layer, a physical reservoir layer, and a plastic output layer [Figure 4A, Supplementary Note 2]. The reservoir’s computational power stems directly from the intrinsic physics of the CNT neurons. The non-linear response and fading memory required for RC are naturally provided by the ion integration (τI) and leakage (τL) dynamics [Supplementary Figure 2], while the fixed synaptic weights within the reservoir are engineered through device geometry and entrance functionalization [Supplementary Figure 3]. In the readout layer, adaptive learning is achieved via a supervised STDP rule, physically governed by the synchronization of ion adsorption and desorption kinetics [Supplementary Figure 4]. Physically, the plasticity is physically governed by the spatiotemporal synchronization between pre-synaptic ion flux and postsynaptic activation, which directly modulates the concentration of adsorbed ions [cads, j(t)] at the entrance of the j-th CNT and thus the synaptic weight (Wj). In the potentiation regime (Δt > 0), the pre-synaptic ion pool temporally aligns with the exposure of postsynaptic functional groups (-COO-), triggering strong electrostatic capture that increases the trapped ion population and consequently enhances the synaptic weight. Conversely, depression arises during load-free activation (Δt < 0), where premature entrance relaxation and shielding prevent the capture of late-arriving ions. The resulting deficit in replenishment, together with continuous thermal desorption, yields a net loss of adsorbed ions, which macroscopically manifests as a reduction in synaptic efficacy.

Figure 4. CNT-based reservoir computing architecture and performance analysis of (A) The overall architecture comprises three layers, including the Input Layer (M parallel CNTs), the Reservoir Layer (N parallel CNTs), and the Output Layer (single CNT). The input layer employs a sliding window sampling strategy to map m historical time-steps (x1, …, xM) onto corresponding analog voltages (V1, …, VM). These voltages drive the CNT encoders to generate stochastic ionbit streams [Sin(t)]. The reservoir layer uses fixed, sparse weights (Wij) to project Sin(t) into an N-dimensional state space. The output layer features plastic weights (Wj) which are updated during training via a supervised STDP rule. The final output is the prediction of the target value (xM+1); (B) The time-series prediction performance for the Mackey-Glass task demonstrates that the physically supervised STDP method successfully tracks the complex periodic dynamics; (C) The MSE of prediction is analyzed and optimized with respect to key physical parameters, including the intrinsic barrier height (ΔGF), reservoir size (N), and the characteristic time constants of integration (τI) and leakage (τL). CNT: Carbon nanotube; STDP: spike-timing-dependent plasticity; MSE: mean-square error.

To rigorously validate the computational universality of the iontronic reservoir, we select two distinct benchmark tasks that challenge different aspects of neuromorphic hardware. The Mackey-Glass chaotic time-series prediction task[43] is employed to assess the system capacity for temporal processing and fading memory. To extend the validation beyond temporal domains, we incorporate the handwritten digit recognition task (UCI Machine Learning Repository)[44], which demands the extraction of features from static, high-dimensional spatial patterns. Detailed implementation protocols for both tasks are provided in Supplementary Notes 2 and 3.

Performance and physical parameter tuning

The prediction capability of the system is quantitatively demonstrated in Figure 4B. The system successfully tracks the chaotic Mackey-Glass dynamics, demonstrating effective feature extraction. A measurable performance gap nevertheless persists between the supervised-based readout [mean-square error (MSE): 0.0222] and the optimal ridge regression (ORR)[60] benchmark (MSE: 0.0039). This discrepancy highlights a fundamental trade-off. Although STDP affords biological plausibility and hardware locality, its discrete and stochastic weight updates limit the fine-grained convergence attainable with global, continuous optimization schemes such as ridge regression.

Complementing the temporal analysis, the system capacity for spatial pattern classification is evaluated. By successfully categorizing static handwritten digits, the reservoir demonstrates robust high-dimensional feature extraction capabilities. However, a distinct accuracy disparity is observed between the supervised STDP readout (86.7%) and the ORR benchmark (95.7%) [Supplementary Figure 5].

We further examine how key physical parameters influence the feature-extraction capability of the reservoir layer in the Mackey-Glass chaotic time-series prediction task, which could guide future experimental nanofluidic studies [Figure 4C]. We scan physical parameters in the ORR implementation, thereby eliminating additional precision loss associated with supervised STDP learning. Reservoir performance is found to depend critically on the alignment between device physics and computational demands. The firing energy barrier (ΔGF) exhibits a convex U-shaped error profile, reflecting a physical compromise between noise amplification at low barriers and information-poor sparsity at high barriers. By contrast, the prediction error decreases monotonically with increasing reservoir size (N), confirming that larger CNT networks provide the high-dimensional projection space required for improved feature separation. System performance further depends on tuning the characteristic time constants to balance physical responsiveness against temporal integration. An excessively small integration time τI yields inadequate temporal averaging, rendering the dynamics vulnerable to the intrinsic discreteness of ion transport. Conversely, an overly large τI slows the system response and smears salient temporal features. The leakage time τL sets the trade-off between memory retention and information renewal. Short τL values lead to rapid signal decay, whereas long τL values promote ion accumulation and saturation, ultimately suppressing effective state updates.

Collectively, these results highlight that minimizing prediction errors caused by rapid signal decay or memory aliasing requires aligning the physical transport timescales with the computational task through rational material engineering.

In practical nanofluidic implementations, device-to-device variations are inevitable due to the stochastic nature of CNT synthesis and functionalization. These variations manifest as fluctuations in physical parameters such as diameter, chirality, and entrance functionalization, which map directly to the computational variables of the SNN (see Supplementary Table 3 for the physical mapping).

To verify the system’s robustness against these manufacturing non-idealities, we conducted a comprehensive sensitivity analysis by introducing statistical heterogeneity into the network parameters [Supplementary Figure 6 and Supplementary Note 4]. We modeled diameter variations as Gaussian distributions in the firing energy barrier (ΔGF) and time constants (τI, τL, and τtrace) as log-normal distributions.

The results indicate that the system maintains high prediction accuracy even under significant parameter dispersion. While the supervised STDP learning rule shows some sensitivity to large spreads in the input and plasticity timescales (τI and τtrace), the leakage dynamics (τL) exhibit remarkable stability. Overall, the system resilience is attributed to the population coding mechanism. Unlike precise logic circuits, where a single component failure is catastrophic, our architecture encodes information in the collective spiking activity of the ensemble. Consequently, the statistical average of the population effectively filters out the heterogeneity of individual neurons, ensuring reliable system-level operation.

With such a physically grounded associative learning mechanism, the framework can be theoretically scaled from isolated devices to functional, large-scale networks. By implementing synaptic memory chemically through local ion accumulation, the system effectively collocates memory and computation, ensuring that energy consumption remains proportional to the sparsity of spike events, thereby maintaining the operation near the thermal energy limit (~ kBT per spike). However, realizing this high-efficiency computing requires a strict alignment between the device’s intrinsic physics and the algorithmic requirements. The characteristic timescales of ion integration and leakage (τI, τL) must match the temporal features of the input data. To achieve this parameter matching, we propose rational material engineering strategies. τL can be precisely tailored by varying the species and grafting density of the functional groups at the entrance, which modulate the local energy landscape. τI can be regulated by engineering the transport properties of the external reservoir. For example, substitute aqueous solutions with ionic gels to tune the ion mobility. These control methods provide the necessary flexibility to align the hardware physics with the optimized algorithmic windows.

Practical considerations and challenges.

A major practical challenge in assembling such systems lies in achieving the dense interlayer connectivity required for functional operation. The close spatial convergence of multiple presynaptic terminals onto a single postsynaptic element can induce synaptic crosstalk and diffusion overlap, compromising the independent tunability of synaptic weights that is essential for local learning. Addressing this constraint will require precise control over nanoscale geometry, spacing, and chemical selectivity.

Despite these challenges, the conceptual design establishes a strong correspondence between nanofluidic iontronic networks and practical neuromorphic computing architectures. The framework presented here provides a basis for realizing multilevel, parallel input-output pathways using a single neuron-like unit, enabling scalable information processing. Moreover, the underlying physical principles are readily extensible to a broader class of nanofluidic platforms, including nanopores, nanoslits, and heterogeneous gels, offering multiple routes toward more robust and scalable hardware implementations. These considerations are not restricted to SNN but are equally relevant to ANN architectures that rely on local learning rules.

Further progress will require systematic validation through well-controlled nanofluidic experiments and complementary atomistic simulations, which together can critically assess the feasibility, robustness, and scalability of iontronic computing at the hardware level.

CONCLUSION

In this work, we established a unified framework for a CNT-based stochastic neuron, introducing the ionbit to bridge nanofluidic physics with the event-driven SNN paradigm. MD simulations confirm that single-file ion transport naturally implements leaky LIF dynamics. We rigorously validated this architecture on both chaotic time-series prediction and handwritten digit recognition tasks, demonstrating its computational universality across temporal and spatial domains. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis confirms that the system exhibits remarkable robustness against device-to-device heterogeneity, leveraging population coding to mitigate manufacturing non-idealities. By exploiting single-ion transport as the fundamental carrier, the system operates near the thermodynamic limit (~kBT per spike). While this physics-driven stochasticity offers exceptional efficiency, establishing CNT-based iontronics as a viable hardware platform will require addressing the fundamental trade-offs between power, accuracy, and memory stability against thermal fluctuations in scalable integrated systems.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the concept: Xu, Z.

Performed the research: Zhai, L.

Analyzed the results and wrote the paper: Zhai, L.; Xu, Z.

Availability of data and materials

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12425201) and the Fundamental and Interdisciplinary Disciplines Breakthrough Plan of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. JYB2025XDXM205). Computations were performed on the Explorer 1000 cluster system at the Tsinghua National Laboratory for Information Science and Technology.

Conflicts of interest

Xu, Z. is an Associate Editor of the journal Iontronics. Xu, Z. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Mentink, J.; Rasing, T.; Kösters, D.; Rijk, I.; Hilgenkamp, H.; Smink, S.; Noheda, B.; Gaydadjiev, G.; Hamdioui, S.; Dolas, S. Neuromorphic Computing in the Netherlands: White Paper. 2024. https://www.ru.nl/sites/default/files/2024-11/whitepaper-neuromorphic-computing-final_pdf.pdf. (accessed 2026-2-10).

2. Eisenberg, B. Ionic channels in biological membranes: natural nanotubes. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998, 31, 117-23.

4. Levitan, I. B. Signaling protein complexes associated with neuronal ion channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 305-10.

5. Drummond, H. A.; Gebremedhin, D.; Harder, D. R. Degenerin/epithelial Na+ channel proteins: components of a vascular mechanosensor. Hypertension 2004, 44, 643-8.

6. Bernèche, S.; Roux, B. Energetics of ion conduction through the K+ channel. Nature 2001, 414, 73-7.

7. Berkefeld, H.; Fakler, B.; Schulte, U. Ca2+-activated K+ channels: from protein complexes to function. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 1437-59.

8. Ro, Y. G.; Na, S.; Kim, J.; et al. Iontronics: neuromorphic sensing and energy harvesting. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 24425-507.

10. Liu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Versatile ion-gel fibrous membrane for energy-harvesting iontronic skin. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2303723.

12. Zhou, N.; Cui, T.; Lei, Z.; Wu, P. Bioinspired learning and memory in ionogels through fast response and slow relaxation dynamics of ions. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4573.

13. Lin, S.; Jiang, J.; Huang, K.; et al. Advanced electrode technologies for noninvasive brain-computer interfaces. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 24487-513.

14. Yegnanarayana, B. Artificial neural networks; PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd., 2009.

15. Yamazaki, K.; Vo-Ho, V. K.; Bulsara, D.; Le, N. Spiking neural networks and their applications: a review. Brain. Sci. 2022, 12, 863.

16. Duan, X.; Cao, Z.; Gao, K.; et al. Memristor-based neuromorphic chips. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2310704.

17. Rivnay, J.; Inal, S.; Salleo, A.; Owens, R. M.; Berggren, M.; Malliaras, G. G. Organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 17086.

18. Li, Y.; Bai, N.; Chang, Y.; et al. Flexible iontronic sensing. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 4651-700.

19. Han, S. H.; Oh, M.; Chung, T. D. Iontronics: aqueous ion-based engineering for bioinspired functionalities and applications. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2022, 3, 031302.

20. Xu, G.; Zhang, M.; Mei, T.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Xiao, K. Nanofluidic ionic memristors. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 19423-42.

21. Xia, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Z.; et al. Organic iontronic memristors for artificial synapses and bionic neuromorphic computing. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 1471-89.

22. Li, L.; Chen, W.; Kong, X.; Wen, L. Nanofluidic neuromorphic iontronics: a nexus for biological signal transduction. Iontronics 2026, 2, 4.

23. Zhu, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, Z. Bio-inspired heterointerfacial ion-gating and iontronic neuromorphics. Iontronics 2025, 1, 4.

24. Han, S. H.; Kim, S. I.; Oh, M. A.; Chung, T. D. Iontronic analog of synaptic plasticity: Hydrogel-based ionic diode with chemical precipitation and dissolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2211442120.

26. Hummer, G.; Rasaiah, J. C.; Noworyta, J. P. Water conduction through the hydrophobic channel of a carbon nanotube. Nature 2001, 414, 188-90.

27. Berezhkovskii, A.; Hummer, G. Single-file transport of water molecules through a carbon nanotube. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 064503.

28. Majumder, M.; Chopra, N.; Hinds, B. J. Mass transport through carbon nanotube membranes in three different regimes: ionic diffusion and gas and liquid flow. ACS. Nano. 2011, 5, 3867-77.

29. Samoylova, O. N.; Calixte, E. I.; Shuford, K. L. Selective ion transport in functionalized carbon nanotubes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 423, 154-9.

30. Lee, C. Y.; Choi, W.; Han, J. H.; Strano, M. S. Coherence resonance in a single-walled carbon nanotube ion channel. Science 2010, 329, 1320-4.

31. Min, H.; Kim, Y. T.; Moon, S. M.; Han, J. H.; Yum, K.; Lee, C. Y. High-yield fabrication, activation, and characterization of carbon nanotube ion channels by repeated voltage-ramping of membrane-capillary assembly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1900421.

32. Choi, W.; Ulissi, Z. W.; Shimizu, S. F.; Bellisario, D. O.; Ellison, M. D.; Strano, M. S. Diameter-dependent ion transport through the interior of isolated single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2397.

33. Li, C.; Xiong, T.; Yu, P.; Fei, J.; Mao, L. Synaptic iontronic devices for brain-mimicking functions: fundamentals and applications. ACS. Appl. Bio. Mater. 2021, 4, 71-84.

34. Han, S. H.; Kim, S. I.; Lee, H. R.; et al. Hydrogel-based iontronics on a polydimethylsiloxane microchip. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 6606-14.

35. Maram, R.; Howe, J. V.; Kong, D.; et al. Frequency-domain ultrafast passive logic: NOT and XNOR gates. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5839.

37. Yang, J. J.; Strukov, D. B.; Stewart, D. R. Memristive devices for computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 13-24.

38. van de Burgt, Y.; Lubberman, E.; Fuller, E. J.; et al. A non-volatile organic electrochemical device as a low-voltage artificial synapse for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 414-8.

39. Dai, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Emerging iontronic neural devices for neuromorphic sensory computing. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2300329.

40. Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Aydin, F.; et al. Water-ion permselectivity of narrow-diameter carbon nanotubes. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6.

42. Zhou, K.; Xu, Z. Ion permeability and selectivity in composite nanochannels: engineering through the end effects. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2020, 124, 4890-8.

43. Zhang, P.; Ma, X.; Dong, Y.; et al. An energy efficient reservoir computing system based on HZO memcapacitive devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 123, 122104.

44. Alpaydin, E.; Kaynak, C. Optical recognition of handwritten digits. Repository, U. M. L., Ed.; University of California, School of Information and Computer Sciences: Irvine, CA, 1998. https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Optical+Recognition+of+Handwritten+Digits. (accessed 2026-2-10).

45. Caporale, N.; Dan, Y. Spike timing-dependent plasticity: a Hebbian learning rule. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 31, 25-46.

46. Squire, L. R.; Berg, D.; Bloom, F. E.; du Lac, S.; Ghosh, A.; Spitzer, N. C. Fundamental Neuroscience. 4th ed. Elsevier, 2012.

47. Paschek, D.; Ludwig, R. Specific ion effects on water structure and dynamics beyond the first hydration shell. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 352-3.

48. Richards, L. A.; Schäfer, A. I.; Richards, B. S.; Corry, B. The importance of dehydration in determining ion transport in narrow pores. Small 2012, 8, 1701-9.

49. Robinson, R. A.; Stokes, R. H. Electrolyte solutions. Courier Corporation, 2002.

50. Tunuguntla, R.; Allen, F.; Kim, K.; Belliveau, A.; Noy, A. Ultra-fast proton transport in sub-1-nm diameter carbon nanotube porins. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 338a.

51. Bukola, S.; Creager, S. E. A charge-transfer resistance model and Arrhenius activation analysis for hydrogen ion transmission across single-layer graphene. Electrochim. Acta. 2019, 296, 1-7.

52. Holden, A. V. Models of the stochastic activity of neurones, Vol. 12. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

53. Consul, P. C.; Jain, G. C. A generalization of the Poisson distribution. Technometrics 1973, 15, 791-9.

54. Gerstner, W.; Kistler, W. M.; Naud, R.; Paninski, L. Neuronal dynamics: from single neurons to networks and models of cognition. Cambridge University Press, 2014; pp 417-20.

55. Samoylova, O. N.; Calixte, E. I.; Shuford, K. L. Molecular dynamics simulations of ion transport in carbon nanotube channels. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015, 119, 1659-66.

56. Cui, G.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Siria, A.; Ma, M. Coupling between ion transport and electronic properties in individual carbon nanotubes. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadu7410.

57. Xiao, K.; Jiang, L.; Antonietti, M. Ion transport in nanofluidic devices for energy harvesting. Joule 2019, 3, 2364-80.

58. Holt, J. K.; Park, H. G.; Wang, Y.; et al. Fast mass transport through sub-2-nanometer carbon nanotubes. Science 2006, 312, 1034-7.

59. Liang, X.; Tang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, B.; Qian, H.; Wu, H. Physical reservoir computing with emerging electronics. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 193-206.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].