Photo-iontronics: mechanisms and manipulation for neuromorphic vision

Abstract

Biological visual systems utilize ions as information carriers and enable efficient, adaptive information processing at the retinal level via complex ion dynamic processes. This provides crucial inspiration for addressing the energy efficiency and latency bottlenecks inherent in von Neumann architecture-based visual systems. Further development of the photo-iontronics field relies on the in-depth understanding and systematic regulation of various photo-ion coupling mechanisms. Its core lies in revealing the inherent laws of interfacial ion dynamics and, on this basis, establishing rational design criteria for device performance. This research framework will facilitate the realization of functionally customizable ion devices, providing a new hardware foundation for processing complex visual information. In this context, this review systematically examines the transition from mimicking biological functions to a mechanism-driven design framework for photo-iontronic devices. We analyze their application potential in machine vision and bio-integrated neural interfaces, outline the key challenges and future directions.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Visual information constitutes over 80% of all sensory input that humans receive[1]. Biological visual systems rely on complex processing networks that involve various ion fluxes and dynamic transport processes, along with synergistic interactions with molecules such as neurotransmitters[2]. The impressive energy efficiency and intelligent performance of these biological systems in interpreting intricate dynamic scenes have long served as benchmarks for artificial vision systems[3-4].

From the initial phototransduction in photoreceptors, to the parallel pathways and lateral inhibition formed by bipolar and horizontal cells, and further to the global adaptive regulation mediated by neuromodulators, ions play a crucial role as messengers at every stage of visual information processing[5]. In contrast, mainstream artificial vision systems still rely on the conventional von Neumann architecture[6], where the information processing chain encompasses perception, encoding, transmission, decoding, storage, and computation. This creates a bottleneck, necessitating frequent data transfer between the sensor and processor and resulting in high latency and power consumption, which is prohibitive for real-time applications[7-8]. Furthermore, fundamental differences in signal carriers and physical mechanisms between solid-state electronic devices and biological neural systems restrict biocompatibility and signal fidelity in cross-interface applications, including brain-machine interfaces[9].

In response to these challenges, neuromorphic devices have emerged[4,10]. Among their various implementations, ion-based neuromorphic devices are notable for utilizing ions as information carriers, which provides inherent physicochemical compatibility with biological systems[11]. While significant progress has been made in emulating various bio-inspired visual functions within this field[12], current research often focuses primarily on functional demonstrations. A systematic understanding of the underlying physicochemical mechanisms, as well as their quantitative regulation, remains underdeveloped, thereby limiting the performance-driven design of devices and the optimal exploitation of their functional potential.

This review analyzes key ion-mediated processes in the biological visual system and outlines the operating principles of different classes of photoionic-coupled neuromorphic devices. We further explore the potential applications of such devices in areas such as retina-inspired intelligent perception chips and bio-integrated visual restoration interfaces. We anticipate that this mechanism-driven research approach can provide a critical pathway for advancing photo-iontronics technology from laboratory exploration to practical application.

IONIC FOUNDATIONS OF BIOLOGICAL VISION

Architecture of biological visual pathway

Biological visual systems exhibit a highly structured hierarchical framework for information processing[3]. Taking mammals as an example, at the heart of their visual system lies the retina, which consists of three cell layers forming an organized signal pathway: the photoreceptor layer (photoreceptors), the interneuron layer (bipolar, horizontal, and amacrine cells), and the output neuron layer (ganglion cells). Photons are captured by photoreceptors, and the resulting signals undergo intricate parallel processing and feature extraction within the interneuron layer. Ganglion cells then convert these signals into sequences of action potentials, which are then transmitted to higher-level visual centers via the optic nerve[13].

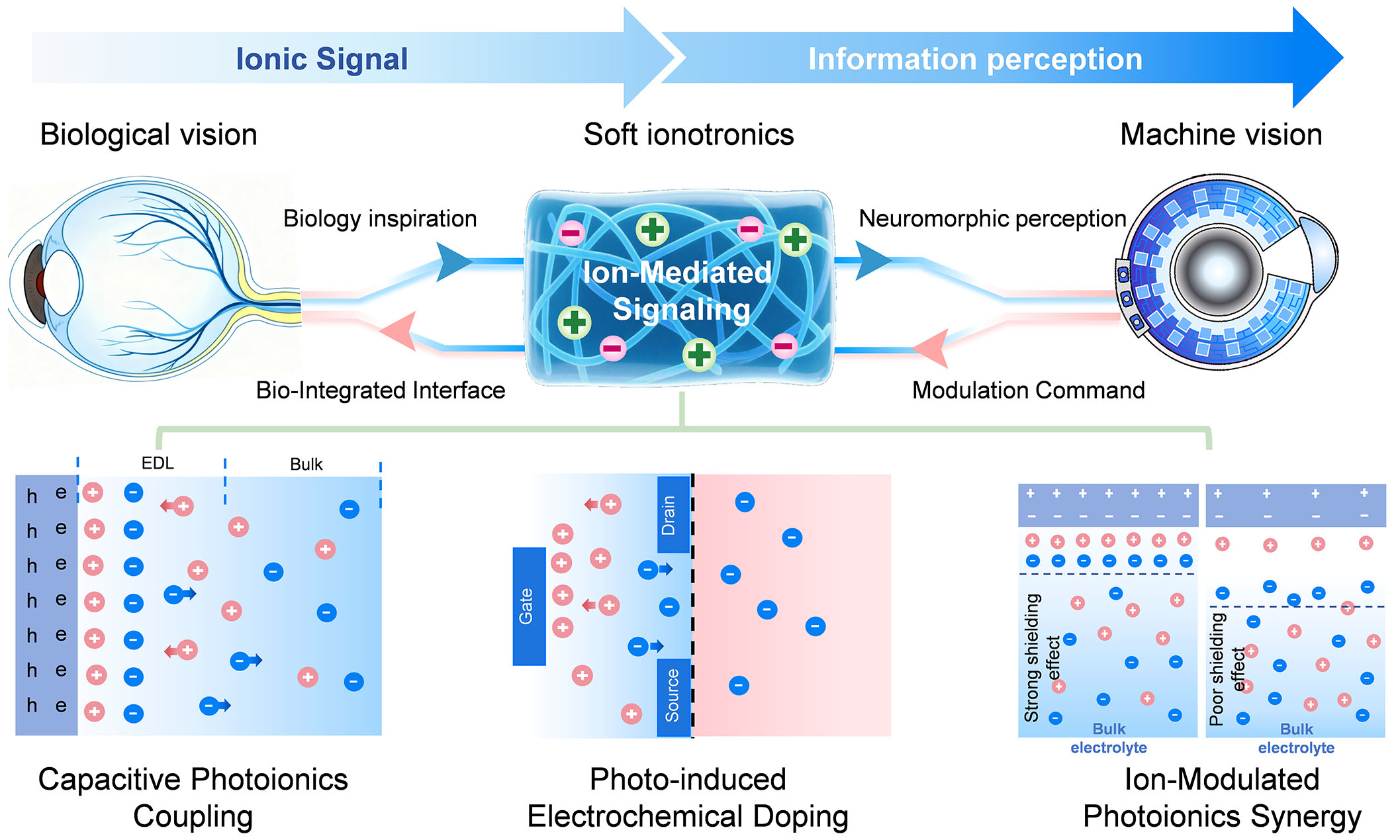

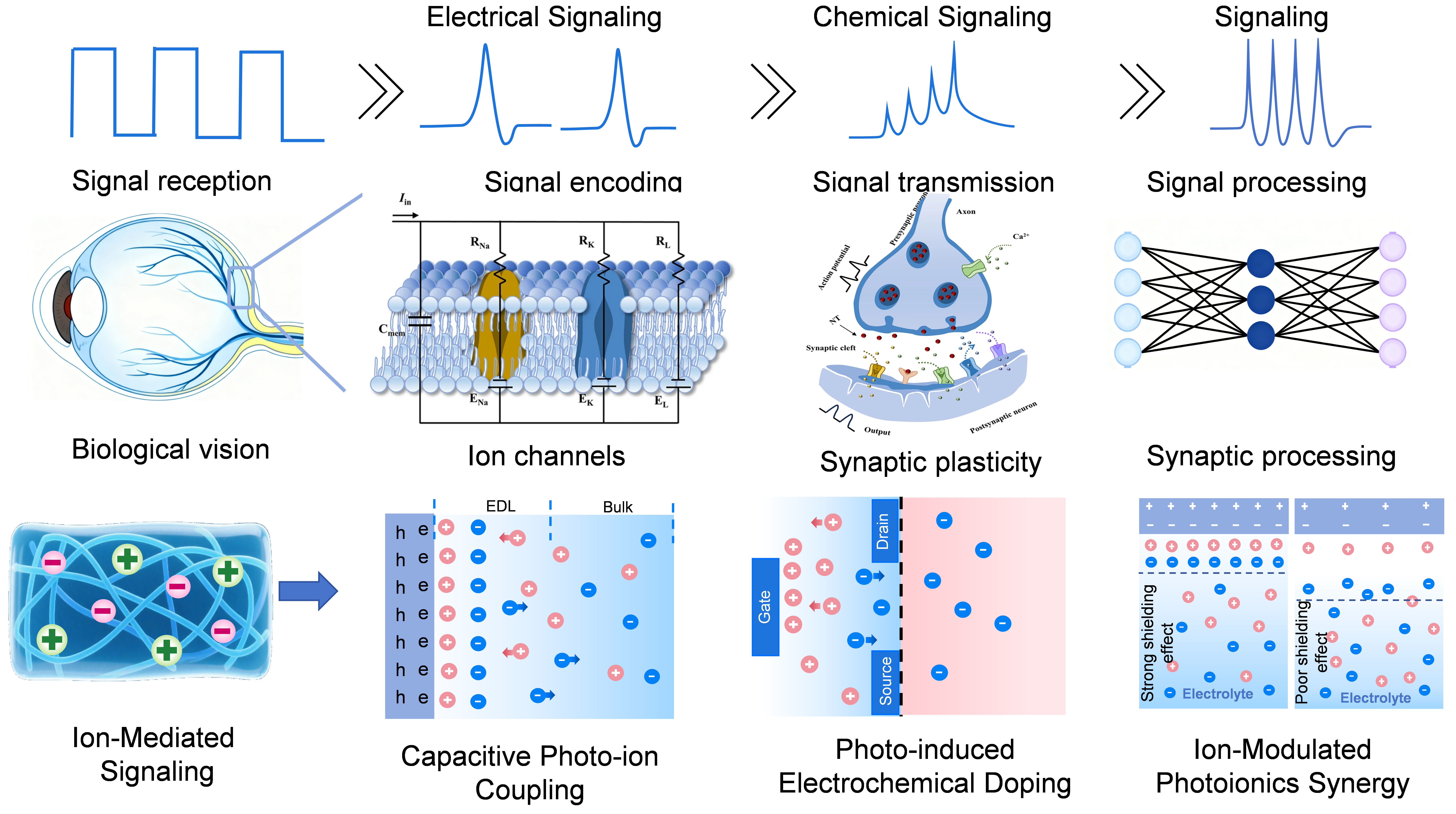

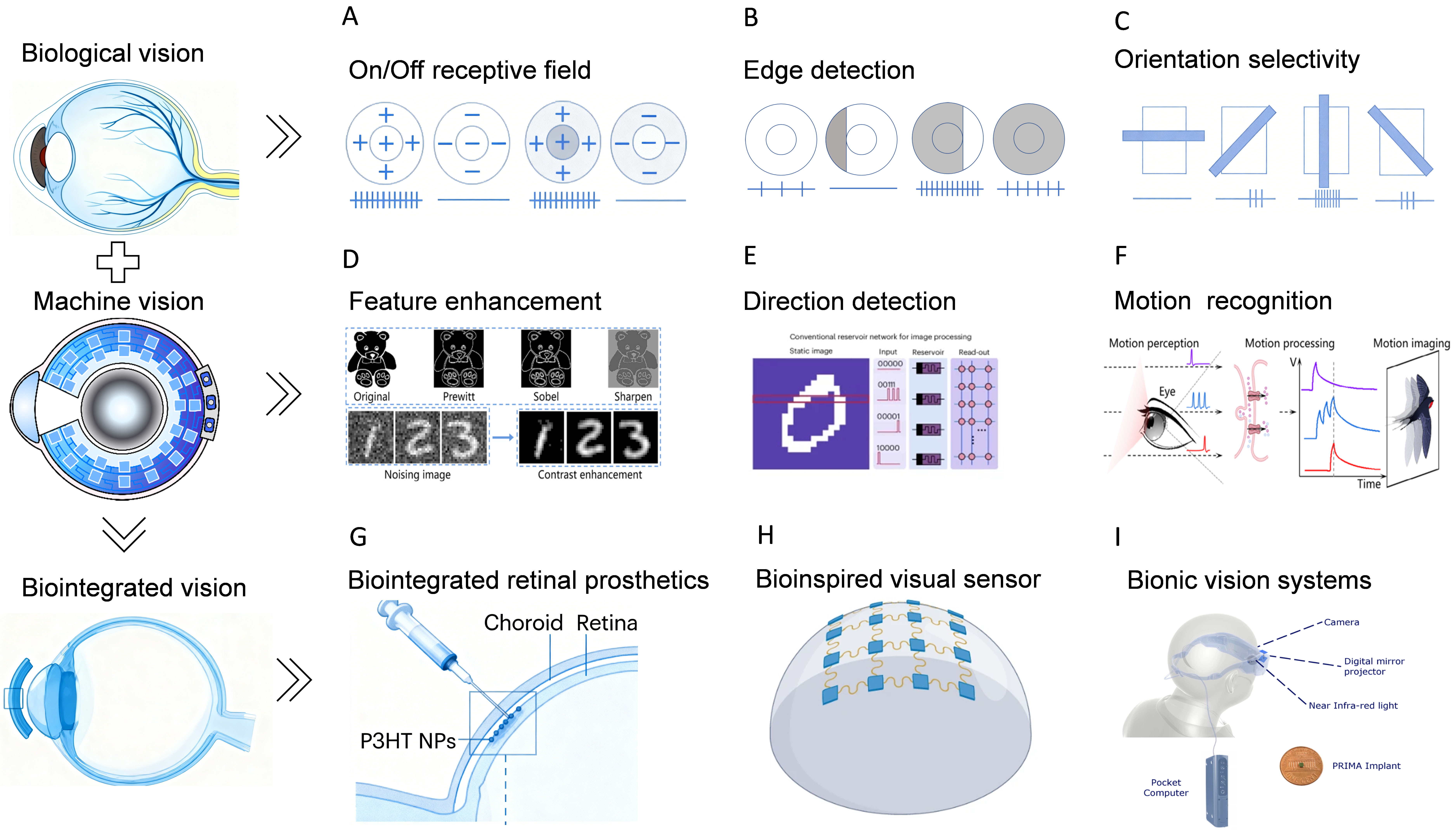

As illustrated in Figure 1, the multi-stage signaling pathway of biological vision corresponds to the biointegrated system’s ionic coupling mechanisms. The top section depicts the multistage signaling pathway in biological vision: from signal reception, encoding, and transmission to processing, involving key mechanisms such as ion channels, synaptic plasticity, and the synergy between electrical and chemical signaling. The bottom section presents the biointegrated vision system inspired by biological vision, whose core photoionic mechanisms include capacitive photo-iontronics, photoelectrochemical doping, and ion-modulated photoionic synergy, reflecting the translation of biological principles into engineering strategies.

Key ionic processes: phototransduction to neural encoding

Visual signal formation begins with the capture and conversion of photons by photoreceptor cells[14]. In dark conditions, a high concentration of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) keeps cGMP-gated cation channels on the cell membrane open, allowing a continuous influx of Na+ and Ca2+, which maintains the cell in a depolarized state. When exposed to light, the phototransduction cascade is initiated: photons activate visual pigments, which subsequently stimulate transducin to activate cGMP phosphodiesterase, leading to the hydrolysis of cGMP. This decrease in cGMP concentration results in the closure of cation channels, diminishing Na+ influx and shifting the membrane potential toward hyperpolarization, thus achieving the initial conversion of light signals into electrical signals[15]. This process exhibits remarkable rapidity, with rod photoresponse activation occurring within 100-200 ms and faster cone responses reaching completion in under 50 ms, enabling real-time tracking of dynamic visual scenes[16-17]. These signals are then transmitted to downstream neurons via chemical synapses. Throughout this process, Ca2+ plays a crucial role: the hyperpolarization of the presynaptic membrane influences the opening of voltage-gated calcium channels, which regulates Ca2+ influx and precisely controls the rate of neurotransmitter release[18]. Synaptic transmission at photoreceptor ribbon synapses is exceptionally fast, with vesicle release dynamics operating on a timescale of ms, ensuring minimal delay in signal relay to bipolar cells[19].

The parallel processing capability of the retina is enhanced by specialized ionic mechanisms. Horizontal cells release inhibitory neurotransmitters and modulate chloride ion (Cl-) conductance to create center-surround antagonistic receptive fields, which are essential for extracting spatial features[20]. Lateral inhibition mediated by horizontal cells operates with a time constant of tens to hundreds of ms, allowing for rapid spatial contrast enhancement. At the same time, bipolar cells express various types of glutamate receptors that divide the incoming signal into parallel ON and OFF pathways[21]. Specifically, metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR6) mediate depolarization in ON-type cells, while ionotropic receptors [Α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid receptor (AMPA)/kainate] mediate hyperpolarization in OFF-type cells, allowing for the separate processing of luminance information[22]. The segregation into ON and OFF pathways occurs almost instantaneously, with AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated responses in OFF bipolar cells being particularly fast, initiating within 2-5 ms of presynaptic glutamate release[23]. The neuromodulator system regulates ionic channel activity through G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), achieving global switching of retinal functional states[24]. For example, dopamine release increases in the light-adapted state, which activates adenylate cyclase through D1 dopamine receptors, promoting intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) elevation and regulating gap junction conductance, inhibiting signal coupling between horizontal cells, and simultaneously enhancing the temporal resolution of ganglion cells, switching the retina from dark-adapted mode to light-adapted mode[25].

Ganglion cells function as the output neurons of the retina, with their axons converging to form the optic nerve, which transmits visual information to the central nervous system. These cells exhibit diverse response patterns: some are sensitive to changes in light intensity (ON/OFF responses)[26], while others selectively encode complex visual features such as motion, direction, or edges. When integrated excitatory inputs from bipolar cells reach threshold, voltage-gated sodium channels (NaV1.6) open, triggering rapid action potentials. Ganglion cells can generate action potentials with a temporal precision in the millisecond range, with some specialized types (e.g., the primate parasol cell) achieving firing rates exceeding 200 spikes per second to accurately encode rapid temporal changes[27]. Repolarization is mediated by potassium efflux through voltage-gated potassium channels (Kv1.1/1.2)[28]. Myelinated axons facilitate saltatory conduction, significantly increasing propagation speed and energy efficiency[29]. Action potentials propagate along the optic nerve at high velocities, ranging from 5 to 40 m/s depending on axon diameter and myelination, ensuring prompt delivery of visual information to the brain[30]. At synaptic terminals, action potential-induced calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels (CaV2.1/2.2) triggers vesicle release, transmitting signals to the lateral geniculate nucleus. Additionally, optic nerve glial cells, including oligodendrocytes, help maintain extracellular potassium homeostasis via specific potassium channels, thereby ensuring stable signal conduction.

The lateral geniculate nucleus serves as a relay between the retina and cortex, where inhibitory interneurons refine retinal signals through spatial filtering and temporal optimization[31]. Synaptic processing in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) introduces minimal delay, with typical response latencies relative to retinal input being less than 2 ms, preserving the high temporal fidelity of the visual stream[32]. These processed signals are then projected to the primary visual cortex via the optic radiation[33]. In visual cortex area 1 (V1), neurons integrate inputs using specific ion channel combinations - simple cells, for instance, achieve orientation selectivity through N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated calcium influx, which activates downstream signaling molecules such as calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) to dynamically modulate synaptic strength[34-35]. The initial response of V1 neurons to visual stimuli can be as rapid as 30-50 ms post-stimulus onset, highlighting the efficiency of the subcortical visual pathway[36].

Higher visual areas process increasingly complex features: visual cortex area 4 (V4) neurons analyze color and shape through coordinated actions of voltage-gated potassium channels and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels, while MT neurons detect motion direction and speed by integrating multi-directional inputs[37]. This integration is facilitated by electrical coupling via gap junctions and rapid signaling through ionotropic glutamate receptors, ensuring efficient visual computation across cortical levels[38].

The mammalian visual system achieves remarkable performance (e.g., single-photon sensitivity[39], wide dynamic range[40], and low power consumption[41]) through finely regulated ionic mechanisms. The precise spatiotemporal orchestration of ionic fluxes constitutes the physicochemical blueprint for the retina’s exceptional performance. While most current devices in this area are based on electronic materials such as silicon complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) and use electrons as signal carriers, ions hold unique potential for constructing artificial systems that more closely emulate biological mechanisms. Iontronic neuromorphic devices not only replicate neuromorphic sensing capabilities such as adaptation and nonlinear responses, but their soft matter characteristics and ionic signaling mechanisms also grant them a distinctive ability to achieve seamless integration with biological tissues[9], both mechanically and informationally. For instance, devices fabricated from soft ionic materials such as hydrogels can form highly biocompatible and conformable interfaces with biological systems[11]. Furthermore, their operational principle, which relies on ionic transport and electrochemical dynamics, is inherently compatible with biological signal transduction pathways.

PHOTO-IONTRONIC MECHANISMS: FROM PRINCIPLES TO DEVICES

Classification of photo-ion coupling mechanisms

The translation of biological ionic mechanisms into artificial device architectures is not simply an exercise in mimicry, but a search for fundamental design principles. To transcend mere biomimicry, we advocate for a mechanism-driven design framework centered on establishing quantitative structure-activity relationships for photo-iontronic devices. First, this requires the decoding of fundamental mechanisms such as interfacial ion migration, electrical double layer (EDL) dynamics, and Faradaic doping kinetics through advanced characterization and multi-scale simulation tools. Second, quantitative correlations must be established between these mechanistic descriptors and key macroscopic device metrics, including responsivity, memory retention, and energy efficiency. Finally, this knowledge must be translated into predictive design rules for materials and interfaces. The following sections analyze the primary photo-ion coupling mechanisms within this framework, mapping each to specific visual computing functions.

However, the precise design and optimization of device performance still require the systematic establishment of quantitative links between device functionality and the underlying physicochemical mechanisms. These mechanisms, including interfacial ion migration, dynamic evolution of the EDL, ion transport in confined spaces, and photoelectrochemical doping, collectively form the physical basis of device behaviors.

The focus of current research is gradually shifting from post hoc interpretation of experimental phenomena toward mechanism-guided design of materials and devices. By systematically correlating the microscopic interfacial properties of materials with the macroscopic performance of devices, it is anticipated that a predictable and invertible "material-to-function" mapping framework can ultimately be established. This approach will propel photo-iontronics devices toward programmable functionality.

Material and interface design for mechanism implementation

The photo-ion coupling mechanisms in neuromorphic vision devices can be categorized into three distinct classes based on their charge transfer nature, timescales, and reversibility: capacitive photoelectric ion coupling, photoelectrochemical doping, and ion-modulated photoelectric synergy. The boundaries between these mechanisms are defined by several key criteria: (1) whether charge transfer across the interface is Faradaic or non-Faradaic; (2) the dominant physical driving force (electric field, redox reaction, or pre-defined ionic gradient); (3) response speed and volatility; and (4) functional roles in emulating visual processing. The following subsections detail each mechanism, with their distinguishing features summarized in Table 1.

Comparison of key characteristics of three primary photo-ion coupling mechanisms for neuromorphic vision devices

| Mechanism | Charge transfer | Primary driver | Timescale | Reversibility & volatility | Key applications |

| Capacitive photoionic coupling[42] | Non-faradaic (EDL modulation) | Photogenerated electric field | µs ~ ms | Reversible, volatile | High-speed sensing, adaptive response |

| Photoelectrochemical doping[43] | Faradaic (redox/ion insertion) | Photon-assisted ion migration | s ~ h | Non-volatile, memory effect | Visual adaptation, synaptic plasticity |

| Ion-modulated photoelectric synergy[44] | Mixed/ion-gradient-driven | Ionic gradients, thermodiffusion | ms ~ s | Configurable (volatile/non-volatile) | Retinal preprocessing, multimodal fusion |

Capacitive photo-ion coupling

Capacitive photo-ion coupling operates through a non-Faradaic, gate-like mechanism where photogenerated carriers regulate the EDL at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface[42]. Under illumination, the absorption of photon energy generates electron-hole pairs in the semiconductor[45], and the behavior of these carriers at the interface directly influences the double-layer formation. In n-type semiconductors, for instance, photogenerated holes accumulate at the interface forming a positive charge layer, while in p-type semiconductors, electrons accumulate forming a negative layer. This light-induced redistribution of interfacial charge establishes a transient, capacitive potential that can modulate ion transport and downstream signals[46]. Photogenerated carriers dynamically modulate the EDL by altering interfacial charge density and capacitance, driving its evolution through a combination of electrostatic, solvation, and chemical interactions[47].

This capacitive coupling mechanism provides a direct pathway for optically interfacing with and modulating biological ionic systems. A key validation comes from organic semiconductor-based neural interfaces, where photoexcitation generates a transient photovoltage at the interface. This photovoltage capacitively couples to adjacent neuronal membranes, modulating transmembrane potential and eliciting neuronal activity without Faradaic charge injection[48-49]. This work crucially demonstrates the functional viability of using capacitive photo-ion coupling for bio-integrated, cell-photonic communication. This capacitive coupling mechanism provides a direct pathway for optically interfacing with and modulating biological ionic systems.

The capacitive photo-ion coupling mechanism exhibits rapid response times ranging from microseconds to milliseconds, which originates from the fast charging and discharging of the EDL[50] and the swift generation and recombination of photogenerated carriers[51]. This characteristic enables neuromorphic vision devices to mimic the initial rapid response of biological photoreceptors. Experimental studies on various material systems, including WS2-graphene heterostructures and MoSe2 phototransistors, have consistently demonstrated sub-millisecond photoresponse times and enhanced bandwidth, attributed to efficient ion modulation of interfacial charge transport[52]. In organic photoelectric stimulators, capacitive charging and discharging with millisecond-scale time constants exhibit complete charge cancellation between phases, demonstrating high reversibility. Unlike Faradaic processes, this capacitive mechanism is inherently reversible, enabling stable device performance over repeated light-dark cycles. The response speed and reversibility can be further optimized through electrolyte engineering, interface design, and modulation of optical or electrical parameters, making the approach particularly suitable for emulating adaptive visual processing.

Furthermore, light-stimulated neural interfaces based on ionic electrical double-layer capacitance utilize a photo-ion coupling mechanism to achieve precise neuronal modulation through non-Faradaic capacitive effects[48]. The underlying process begins with photoconversion, where illumination of semiconductor materials such as TiO2[53], organic semiconductors, or quantum dots generates electron-hole pairs that migrate to the semiconductor/electrolyte interface. These photogenerated carriers then alter the interfacial charge distribution, creating an electric field that drives the reversible adsorption of cations toward the neuronal membrane, forming a Helmholtz double-layer structure. This ionic redistribution subsequently induces transmembrane potential changes which, upon reaching threshold, trigger action potentials without direct faradaic reactions, avoiding the generation of harmful free radicals (e.g., ·OH) and ensuring enhanced stimulation safety[54].

Photoelectrochemical doping

The photoelectrochemical doping mechanism involves light-driven Faradaic processes, representing a distinct physicochemical pathway from capacitive mechanisms. In this process, photoexcitation not only generates charge carriers but also drives redox reactions at the interface, leading to ion insertion or extraction that induces nonvolatile changes in material conductivity[43]. The core principle lies in the photon energy overcoming ion migration barriers, enabling ion movement within the material lattice[55]. The process typically begins with photon absorption by the semiconductor, generating electron-hole pairs that migrate to the semiconductor/electrolyte interface where they participate in redox reactions. For instance, in n-type semiconductors, photogenerated holes oxidize ions in the electrolyte[56], while electrons may reduce interfacial species[57]. These reactions facilitate ion insertion or extraction, thereby modifying the electrical properties of the material.

A key characteristic of photoelectrochemical doping is its nonvolatile nature. Unlike capacitive mechanisms, Faradaic processes involve bond breaking and formation, creating memory effects that can persist for hours or even days[58]. Research on p-type layered InSe reveals light-induced copper intercalation, where copper photodeposition occurs on cleaved surfaces while copper becomes intercalated when the surface perpendicular to the cleavage plane contacts the electrolyte. This intercalated copper does not spontaneously deintercalate in the dark, confirming the nonvolatile character of the photoelectrochemical doping process[59]. The timescale and stability of doping are governed by ion migration barriers, which can be tuned through crystal structure, defect concentration, and chemical composition to precisely control conductance relaxation dynamics.

Furthermore, recent significant progress has been made in retinomorphic synapses and multisensory integration devices based on photoelectrochemical mechanisms. For example, Zheng et al. reported a photoelectrochemical retinomorphic synapse capable of mimicking visual adaptation and spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP)[60]. In the area of organic photoelectrochemical multisensory integration[60], Huang et al. demonstrated the fusion processing of optical, electrical, and ionic multimodal signals within a single device[61]. Additionally, an optoelectrochemical synapse based on a single-component n-type mixed conductor enables non-volatile conductance modulation through ion intercalation, providing a new approach for highly integrated neuromorphic vision systems[62]. These works further enrich the application pathways of photoelectrochemical mechanisms in bio-inspired vision and neuromorphic computing.

The diverse mechanisms outlined above highlight the complexity of achieving precise control over photoionic interactions. Translating this mechanistic understanding into programmable device functionalities presents several cross-cutting challenges.

Ion-modulated photoelectric synergy

The ion-modulated optoelectronic synergy mechanism represents a unique form of light-ion coupling in which the state of the interfacial ionic double layer dynamically regulates the optoelectronic response of a device. Central to this mechanism is the bidirectional coupling between ion distribution and optoelectronic processes: ion arrangement at the interface not only results from photoexcitation but also actively influences light absorption, carrier generation, and charge transport. This interaction gives rise to nonlinear optical properties and dynamic tunability. At the semiconductor/electrolyte interface, the formation of the EDL involves complex physicochemical processes, including electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, and specific chemical adsorption, which collectively establish a layered structure comprising an inner Helmholtz layer and an outer Gouy-Chapman diffusion layer[45]. Under illumination, photogenerated carriers alter the interfacial charge density, thereby modifying the double-layer structure, which in turn affects carrier dynamics, forming a feedback loop that controls photogenerated charge transport.

This synergistic mechanism exhibits photoconductance relaxation across multiple timescales, reflecting the kinetics of distinct physical processes. These include ultrafast carrier generation and recombination (picoseconds to nanoseconds), ion rearrangement within the double layer (nanoseconds to microseconds), bulk ion diffusion (microseconds to seconds), and slower structural evolution (seconds to minutes). In organic photostimulation devices, for instance, the transient photocurrent response varies with pulse duration, revealing the competition between capacitive and Faradaic processes over different timescales. Similarly, in perovskite systems, ion gel gating can reversibly modulate photoluminescence intensity by several orders of magnitude via ion migration-mediated trap passivation. Such multiscale dynamics are often coupled in practical devices, necessitating multiphysics models that integrate interfacial energy levels, voltage buildup, and ion-electron interactions to quantitatively predict device behavior under optical and electrical stimulation.

Photonic-ionic signal transduction can also be achieved through two principal mechanisms: photothermally driven ion transport and photochemical modulation of ionic conductivity. The photothermal pathway follows a sequential energy conversion from light to heat to ion migration, wherein photothermal materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), MXenes, or gold nanoparticles absorb optical energy to generate localized temperature gradients. These gradients drive directional ion transport via thermophoresis, Soret effects, or photothermal-photoelectric synergy[12]. CNTs achieve photothermal conversion efficiencies up to 88%, MXenes produce cross-channel diffusion potentials, and hydrogel-Fe3O4 nanocomposites enable reversible modulation of ionic conductivity[44]. The photochemical mechanism, on the other hand, encompasses photoinduced electrochemical doping, photoisomerization and conformational switching, and photoactivated redox reactions. These mechanisms find broad application in neuromorphic vision devices, including bioinspired retinas for edge detection, self-powered ionic gel-based artificial eyes for intensity pattern recognition, photonic synapses for red, green, and blue (RGB) color separation, and flexible prosthetic retinas providing charge injection with gold nanorods enabling near-infrared visual restoration[63]. Such devices not only exhibit enhanced biocompatibility due to their similarity to biological ionic signaling but also offer advantages such as non-contact operation, multiwavelength encoding, and low power consumption. Nevertheless, challenges remain in photonic-ionic conversion efficiency, long-term stability, and large-scale integration, calling for future efforts in material innovation, interface engineering, and system architecture to advance high-performance bio-inspired vision systems.

Implementation challenges and future directions

This hierarchical translation from biological principles to device design is illustrated in Figure 2, which provides a roadmap for developing functional ionic vision systems. A central challenge is the transition from mechanistic understanding to functional programming. This requires breakthroughs in three key areas: interface engineering, characterization methodologies, and system integration. At the core lies interface precision engineering, demanding atomic/molecular-scale control over the structure and composition of semiconductor/electrolyte interfaces[64]. This involves screening electrolyte systems with tailored ion migration energy barriers, designing semiconductor materials where ion intercalation dynamics are regulated through defect engineering, and constructing nanointerfaces with heterojunctions or gradient structures to guide directional ion transport[65]. To complement these material-level advancements, a deeper mechanistic understanding must be achieved by combining advanced characterization techniques, such as Kelvin probe force microscopy and in situ spectroscopy, with multi-scale simulation methods spanning from molecular dynamics to phase-field modeling. This integrated approach is essential to systematically unravel the dynamic coupling among photons, ions, and electrons at interfaces. Ultimately, it aims to establish quantitative predictive models that bridge microscopic mechanisms with macroscopic device responses. Furthermore, at the system level, innovative integration strategies must be developed to enable the synergistic combination of different response modes in three-dimensional architectures. For instance, vertically stacking capacitive fast-response units, electrochemical doping memory units, and ion-modulated processing units could allow the implementation of complex visual computing functions within a single device. Through concerted progress along these parallel paths, the development of ion-based vision devices with fully customizable functionalities becomes feasible. These advancements are poised to achieve breakthroughs in biomimetic vision simulation. More significantly, they may unlock novel information-processing paradigms capable of exceeding the biological visual system in tailored scenarios, such as ultra-dynamic range imaging or operation in extreme environments. However, realizing this potential necessitates a frank acknowledgment of current limitations, particularly the trade-offs between ionic switching speed and device stability, which demand innovative solutions in interface engineering.

Figure 2. Hierarchical correspondence in visual information processing from biological principles to photoionic devices. Hierarchical correspondence in visual information processing from biological principles to photoionic devices. (A-C) Neural mechanisms in biological vision, including retinal On/Off receptive fields, edge detection, and orientation selectivity; (D-F) Design blueprint of photo-iontronics-based bionic artificial retinas inspired by biological mechanisms; (G-I) Biointegrated artificial visual devices enabled by photoionic technologies, such as retinal prostheses for vision restoration, retinal-function emulating sensors, and bionic systems for motion perception.

TOWARD FUNCTIONAL IONIC VISION SYSTEMS

Driven by growing mechanistic understanding of photo-ion coupling, the design of photo-iontronics devices is progressively shifting from functional demonstration toward performance-tunable and application-specific customization. The capacitive coupling mechanism, known for its microsecond-to-millisecond-scale photoresponse, offers a foundation for constructing high-speed visual sensing units. In parallel, photoelectrochemical doping, which induces nonvolatile conductance modulation through Faradaic processes such as Li+ or H+ intercalation[66-67], enables memory and adaptive functions that mimic visual adaptation and short-term plasticity. Furthermore, ion-modulated photoelectric synergy provides a physical pathway for implementing retinal preprocessing algorithms such as center-surround antagonism and ON/OFF pathway segregation in hardware.

These advances are guiding the development of such devices along two major trajectories with distinct application prospects: retina-inspired intelligent perception chips and bio-integrated visual restoration interfaces.

Retina-inspired perception chips

To construct ion-based visual neuromorphic devices, researchers typically employ a co-design strategy encompassing material selection, interface engineering, and device architecture. At the material level, ionic conductors such as ionic liquids, hydrogels, or polymer electrolytes serve as the medium for ion transport, while low-dimensional semiconductors such as two-dimensional thiophosphates or quantum dots provide efficient photoelectric conversion. Interface engineering focuses on constructing stable semiconductor/electrolyte heterojunctions through atomic-layer-deposited barrier layers or self-assembled molecular monolayers to enhance charge-ion coupling efficiency. In terms of device architecture, vertically integrated structures combining sensing, memory, and processing functions enable parallel in-sensor computing.

The realization of neuromorphic retinal devices necessitates a co-design philosophy that transcends individual material innovations. It requires the synergistic optimization of dynamic range, temporal fidelity, and energy efficiency at the system level - attributes directly inherited from the biological visual system. The primary objective, therefore, is to engineer ion-based devices that not only mimic specific retinal functions (e.g., edge detection) but also embody the retina’s core computational principle: parallel, in-sensor preprocessing to fundamentally circumvent the von Neumann bottleneck. This entails designing interfaces where ionic fluxes, triggered by light, can directly perform nonlinear operations - such as spatial contrast enhancement and temporal filtering - before any centralized digital processing occurs. The following exemplars highlight how different strategies in material and interface design are being leveraged to achieve this goal.

Building upon these device construction strategies, the primary objective of neuromorphic retinal devices is to fundamentally overcome the energy efficiency and latency limitations of the von Neumann architecture by enabling parallel information processing and preprocessing at the sensor level. In dynamic preprocessing and feature extraction, leveraging the rapid response characteristics of capacitive photoionic and spatially nonlinear interactions mediated by ions, researchers have developed neuromorphic vision sensors capable of direct edge enhancement at the device level. For instance, Zhang et al. used bilayer ionic hydrogels with CNT-doped upper layers for photothermal-driven ion transport, integrating inhibitory/excitatory synaptic arrays into convolutional kernels to suppress Gaussian noise in Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology (MNIST) images, boosting classification accuracy from 68.9% to 83%[12].

In the domain of multimodal fusion perception, ions serving as universal carriers for diverse physical signals offer unique advantages for cross-modal sensing in neuromorphic vision systems. Wu et al. developed a bio-inspired ionic hydrogel synapse that precisely regulates ion transport through piezoionic and ion-thermodiffusion effects[68]. This device achieved the fusion processing of tactile and visual signals within a single unit, pioneering a new path for constructing self-powered embodied intelligent perception systems. The ionic hydrogel exhibited a pressure sensitivity of 0.36 kPa and a thermal response time of 1.2 s, enabling simultaneous detection and processing of mechanical and optical stimuli61.

Bio-integrated visual restoration interfaces

While retina-inspired chips aim to revolutionize machine vision, the inherent biocompatibility of ionic devices unlocks equally transformative potential in biomedical applications, particularly for visual restoration. Current research on bio-integrated interfaces for visual restoration primarily focuses on two technical routes: electrode array-based electrical stimulation systems (e.g., Argus II) and optogenetic approaches[69]. The former achieves partial visual recovery through microelectrode arrays implanted in the retina while suffering from limited spatial resolution (~ 60 pixels), inevitable tissue damage during implantation, and chronic inflammatory responses caused by mechanical mismatch between rigid electrodes and soft neural tissues. Optogenetic methods, while enabling cell-type-specific stimulation, require viral-mediated gene modification and face challenges of limited light penetration depth in biological tissues, restricting their clinical applicability[70]. Common bottlenecks across existing technologies include inefficient interface coupling, signal crosstalk, and poor long-term stability - issues stemming from the fundamental mismatch between abiotic electronic materials and biological ionic systems.

Recent advances in ferroelectric bioelectronics and ionic conductive materials have shown promising improvements. For instance, Wang et al. developed neuron-inspired ferroelectric devices (FerroE) integrating polydopamine-coated barium titanate (PDA@BTO) nanoparticles and poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-trifluoroethylene [P(VDF-TrFE)] copolymer, which demonstrate 3.6 V photoresponse within 100 ms and maintain stability for 180 days in physiological environments[71]. Ji et al. designed ionic conductive hydrogels with urea-based ionic liquids that exhibit enhanced mechanical properties (340 kPa tensile strength, 1,075 % elongation) and antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), addressing biocompatibility concerns in prolonged implantation[72]. However, these approaches still rely on indirect signal conversion between electrons and ions, leading to inevitable energy loss and response delay.

Ion-based neuromorphic devices demonstrate distinctive advantages in the field of bio-integrated interfaces and visual restoration, owing to their physicochemical homology with biological visual systems. This shared foundation provides an ideal platform for constructing high-efficiency bio-electronic interfaces. Ions, serving as the native carriers of neural signals, align closely with transmembrane transport mechanisms of ions such as Na+ and K+ in neural tissues[73]. This “carrier consistency” enables the establishment of low-noise, highly biocompatible information transmission systems. Unlike conventional electronic interfaces, ion-based devices can achieve multi-physical field regulation (photo-thermal-ionic coupling) with millisecond-level response, as demonstrated by the FerroE’s wireless non-genetic modulation of neural activities. Furthermore, the integration of self-healing ionic hydrogels enables in-situ repair of interface damage, while intrinsic antibacterial properties reduce infection risks during long-term implantation[74]. Such features collectively address the core limitations of current visual restoration technologies, paving the way for next-generation bio-integrated interfaces with seamless neural communication and adaptive environmental responsiveness.

In the development of high-biocompatibility retinal prostheses, flexible ionic conductors, such as hydrogels and ionogels, exhibit mechanical properties similar to those of biological tissues. This similarity ensures mechanically conformal integration of the devices, significantly mitigating long-term physical damage to neural structures. Furthermore, ionic signal transduction mechanisms based on capacitive coupling or electrochemical doping offer a safer alternative to traditional Faradaic charge injection from metal electrodes. These ion-based approaches can directly modulate the states of ion channels on neuronal membranes to achieve neural stimulation. Luo et al. designed a hemispherical neuromorphic eye based on a soft ionogel heterostructure, which achieved perfect conformability to the curved ocular surface and transplantable functionality, thanks to the material’s high soft-elasticity and self-healing properties[75].

Looking toward more forward-looking approaches, chemical-signal-mediated intelligent neuromodulation represents a promising direction. Future devices may achieve “chemical dialogue” with biological visual circuits by sensing neuromodulators such as dopamine. For example, an intelligent retinal prosthesis could adaptively adjust its stimulation strategy based on ambient dopamine concentration changes, optimizing spatial resolution and sensitivity under bright and dark conditions, respectively. This capability would advance visual restoration beyond simple electrical stimulation toward an intelligent regulation stage, characterized by deep integration with biological systems.

Based on the analysis of the aforementioned application scenarios, neuromorphic vision technology grounded in photoionic mechanisms is progressively evolving in functionality, from mimicking retinal computational architectures to achieving bio-compatible interfaces, and further towards chemical-signal-level interactions. This developmental trajectory not only provides hardware solutions for constructing machine vision systems characterized by low power consumption and high parallelism, but also establishes a solid foundation for deep integration with biological visual pathways and the development of next-generation visual restoration technologies. As the mechanisms of ion regulation are further elucidated and device performance continues to be optimized, such technologies are poised to exert a more profound impact in fields including autonomous perception systems and neural medical engineering.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

This review articulates a mechanism-driven framework for photo-iontronics, translating principles of biological vision into device design through three core coupling mechanisms: capacitive, photoelectrochemical doping, and ion-modulated synergy. These mechanisms underpin the development of next-generation retina-inspired perception chips and bio-integrated visual restoration interfaces. To advance from conceptual promise to practical application, critical bottlenecks in interface engineering, mechanism quantification, and system integration must be addressed. Future concerted efforts in material innovation and multi-scale regulation will be pivotal in harnessing ionic intelligence for transformative applications in low-power machine vision and adaptive neural repair. Ultimately, by shifting the paradigm from functional mimicry to mechanistic programming, we can unlock the full potential of iontronic devices for truly intelligent and adaptive visual systems.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all colleagues for their valuable discussions and suggestions.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Zheng, L.; Xiao, K.

Investigation: Zheng, L.; Zhu, X.;

Writing - original draft: Zheng, L.;

Visualization: Zheng, L.;

Writing - review & editing: Zhu, X.; Xiao, K.

Validation: Zhu, X.

Supervision: Xiao, K.

Project administration: Xiao, K.

Funding acquisition: Xiao, K.

Data and Material Availability

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the following funding sources:

Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (B2401005)

National Natural Science Foundation of China (22275079, 22474053)

National Key Technologies R&D Program of China (2023YFC2415900)

Guangdong Innovative and Entrepreneurial Research Team Program (2023ZT10C027)

Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KQTD20221101093559017, JCYJ20230807093205011)

Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024A1515012600)

State Key Laboratory of New Textile Materials and Advanced Processing, Wuhan Textile University (FZ2025016)

Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Advanced Biomaterials (2022B1212010003)

Starting Grant from Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech)

Conflicts of interest

Xiao, K. is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Iontronics. Xiao, K. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Lee, M.; Lee, G. J.; Jang, H. J.; et al. An amphibious artificial vision system with a panoramic visual field. Nat. Electron. 2022, 5, 452-9.

2. Chen, W.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics for electronic-to-multi-ionic signal transmission. Science 2023, 382, 559-65.

3. Zhu, S.; Xie, T.; Lv, Z.; et al. Hierarchies in visual pathway: functions and inspired artificial vision. Adv. Mater. 2023, 36, 2301986.

5. Lee, A. G., Morgan, M. L., Palau, A. E. B., et al. Anatomy of the Optic Nerve and Visual Pathway. In Nerves and Nerve Injuries; Elsevier, 2015; pp 277-303. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-410390-0.00020-2.

6. Berco, D.; Shenp Ang, D. Recent progress in synaptic devices paving the way toward an artificial cogni-retina for bionic and machine vision. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2019, 1, 1900003.

7. Peric, I.; Andreazza, A.; Augustin, H.; et al. High-voltage CMOS active pixel sensor. IEEE. J. Solid-State. Circuits. 2021, 56, 2488-502.

8. Lv, Z.; Xing, X.; Huang, S.; et al. Self-assembling crystalline peptide microrod for neuromorphic function implementation. Matter 2021, 4, 1702-19.

9. Boufidis, D.; Garg, R.; Angelopoulos, E.; Cullen, D. K.; Vitale, F. Bio-inspired electronics: Soft, biohybrid, and “living” neural interfaces. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1861.

10. Shan, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, X.; et al. Plasmonic optoelectronic memristor enabling fully light-modulated synaptic plasticity for neuromorphic vision. Adv. Sci. 2021, 9, 2104632.

11. Tang, K.; Wang, J.; Pei, X.; et al. Flexible coatings based on hydrogel to enhance the biointerface of biomedical implants. Adv. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2025, 335, 103358.

12. Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Bio-inspired retina by regulating ion-confined transport in hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2500809.

14. Barrera, V.; Maccormick, I. J. C.; Czanner, G.; et al. Neurovascular sequestration in paediatric P. falciparum malaria is visible clinically in the retina. eLife 2018, 7, e32208.

16. García, M. C.; Urdapilleta, E. Dynamical differences in rod and cone photoresponses. Math. Biosci. 2025, 384, 109445.

17. Akula, J. D.; Lancos, A. M.; Alwattar, B. K.; De Bruyn, H.; Hansen, R. M.; Fulton, A. B. A simplified model of activation and deactivation of human rod phototransduction - an electroretinographic study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 36.

18. Dolphin, A. C.; Lee, A. Presynaptic calcium channels: specialized control of synaptic neurotransmitter release. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 213-29.

19. Thoreson, W. B. Transmission at rod and cone ribbon synapses in the retina. Pflugers. Arch. -. Eur. J. Physiol. 2021, 473, 1469-91.

20. Hirano, A. A.; Vuong, H. E.; Kornmann, H. L.; et al. Vesicular release of GABA by mammalian horizontal cells mediates inhibitory output to photoreceptors. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 600777.

21. Ichinose, T.; Habib, S. On and off signaling pathways in the retina and the visual system. Front. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2, 989002.

22. Borghuis, B. G.; Looger, L. L.; Tomita, S.; Demb, J. B. Kainate receptors mediate signaling in both transient and sustained OFF bipolar cell pathways in mouse retina. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 6128-39.

23. Snellman, J.; Nawy, S. Regulation of the retinal bipolar cell mGluR6 pathway by calcineurin. J. Neurophysiol. 2002, 88, 1088-96.

24. Rojas, A.; Dingledine, R. Ionotropic glutamate receptors: regulation by g-protein-coupled receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 83, 746-52.

25. Goel, M.; Mangel, S. C. Dopamine-mediated circadian and light/dark-adaptive modulation of chemical and electrical synapses in the outer retina. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 647541.

26. Chichilnisky, E. J.; Kalmar, R. S. Functional asymmetries in ON and OFF ganglion cells of primate retina. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 2737-47.

27. Mani, A.; Schwartz, G. W. Circuit mechanisms of a retinal ganglion cell with stimulus-dependent response latency and activation beyond its dendrites. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 471-82.

28. Hughes, S.; Foster, R. G.; Peirson, S. N.; Hankins, M. W. Expression and localisation of two-pore domain (K2P) background leak potassium ion channels in the mouse retina. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46085.

29. Rama, S.; Zbili, M.; Debanne, D. Signal propagation along the axon. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018, 51, 37-44.

30. Erskine, L.; Herrera, E. The retinal ganglion cell axon’s journey: insights into molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Dev. Biol. 2007, 308, 1-14.

31. Casanova, C.; Chalupa, L. M. The dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus and the pulvinar as essential partners for visual cortical functions. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1258393.

32. Freeman, S. A.; Desmazières, A.; Fricker, D.; Lubetzki, C.; Sol-foulon, N. Mechanisms of sodium channel clustering and its influence on axonal impulse conduction. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2015, 73, 723-35.

33. Leopold, D. A. Primary visual cortex: awareness and blindsight. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 91-109.

34. Hubel, D. H.; Wiesel, T. N. Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat's visual cortex. The. Journal. of. Physiology. 1962, 160, 106-54.

35. Bear, M. F.; Malenka, R. C. Synaptic plasticity: LTP and LTD. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1994, 4, 389-99.

36. Deng, K.; Schwendeman, P. S.; Guan, Y. Predicting single neuron responses of the primary visual cortex with deep learning model. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2305626.

37. Parker, A. J. Intermediate level cortical areas and the multiple roles of area V4. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 16, 61-7.

38. Cao, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, Y. Gap junctions regulate the development of neural circuits in the neocortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2023, 81, 102735.

39. Kilpeläinen, M.; Westö, J.; Tiihonen, J.; et al. Primate retina trades single-photon detection for high-fidelity contrast encoding. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4501.

40. Liao, F.; Zhou, Z.; Kim, B. J.; et al. Bioinspired in-sensor visual adaptation for accurate perception. Nat. Electron. 2022, 5, 84-91.

41. Dodda, A.; Jayachandran, D.; Subbulakshmi Radhakrishnan, S.; et al. Bioinspired and Low-power 2D machine vision with adaptive machine learning and forgetting. ACS. Nano. 2022, 16, 20010-20.

42. Li, X.; Wang, Z. L.; Wei, D. Scavenging energy and information through dynamically regulating the electrical double layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2405520.

43. Chen, K.; Hu, H.; Song, I.; et al. Organic optoelectronic synapse based on photon-modulated electrochemical doping. Nat. Photonics. 2023, 17, 629-37.

44. Tian, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. Optically modulated ionic conductivity in a hydrogel for emulating synaptic functions. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd6950.

45. Zheng, M.; Lin, S.; Tang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Z. L. Photovoltaic effect and tribovoltaic effect at liquid-semiconductor interface. Nano. Energy. 2021, 83, 105810.

46. Hu, X.; Jiang, H.; Lu, L. X.; et al. Revisiting the hetero-interface of electrolyte/2D materials in an electric double layer device. Small 2023, 19, 2301798.

47. Miyasaka, T.; Murakami, T. N. The photocapacitor: an efficient self-charging capacitor for direct storage of solar energy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 3932-4.

48. Abdullaeva, O. S.; Schulz, M.; Balzer, F.; et al. Photoelectrical stimulation of neuronal cells by an organic semiconductor-electrolyte interface. Langmuir 2016, 32, 8533-42.

49. Gautam, V.; Rand, D.; Hanein, Y.; Narayan, K. S. A polymer optoelectronic interface provides visual cues to a blind retina. Adv. Mater. 2013, 26, 1751-6.

50. Zhang, C.; Calegari Andrade, M. F.; Goldsmith, Z. K.; et al. Molecular-scale insights into the electrical double layer at oxide-electrolyte interfaces. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10270.

51. Li, L.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; et al. Adaptative machine vision with microsecond-level accurate perception beyond human retina. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6261.

52. Park, J.; Kim, M. S.; Kim, J.; et al. Avian eye-inspired perovskite artificial vision system for foveated and multispectral imaging. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadk6903.

53. Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37-8.

54. Jakešová, M.; Silverå Ejneby, M.; Đerek, V.; et al. Optoelectronic control of single cells using organic photocapacitors. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav5265.

58. Guan, L.; Yu, L.; Chen, G. Z. Capacitive and non-capacitive faradaic charge storage. Electrochim. Acta. 2016, 206, 464-78.

59. Li, M.; Lin, C. Y.; Yang, S. H.; et al. High Mobilities in Layered InSe Transistors with Indium‐Encapsulation‐Induced Surface Charge Doping. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1803690.

60. Hu, J.; Jing, M. J.; Huang, Y. T.; et al. A Photoelectrochemical Retinomorphic Synapse. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2405887.

61. Huang, Y. T.; Li, Z.; Yuan, C.; Zhu, Y. C.; Zhao, W. W.; Xu, J. J. Organic photoelectrochemical multisensory integration. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2503030.

62. Wang, Y.; Shan, W.; Li, H.; et al. An optoelectrochemical synapse based on a single-component n-type mixed conductor. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1615.

63. Chung, W. G.; Jang, J.; Cui, G.; et al. Liquid-metal-based three-dimensional microelectrode arrays integrated with implantable ultrathin retinal prosthesis for vision restoration. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 688-97.

64. Yang, J.; Pan, J.; Du, S. Understanding surface/interface-induced chemical and physical properties at atomic level by first principles investigations. WIREs. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 15, e70030.

65. Sotoudeh, M.; Groß, A. Computational screening and descriptors for the ion mobility in energy storage materials. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2024, 46, 101494.

66. Goodenough, J. B.; Park, K. The Li-ion rechargeable battery: a perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1167-76.

68. Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Chang, W.; et al. A biomimetic ionic hydrogel synapse for self-powered tactile-visual fusion perception. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2500048.

69. Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, C.; et al. Bioinspired and biointegrated vision for artificial sight convergence. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 3, 939-54.

70. Yu, N.; Huang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xue, T.; Chen, Z.; Han, G. Near-infrared-light activatable nanoparticles for deep-tissue-penetrating wireless optogenetics. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1801132.

71. Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.; Lu, Y.; Du, X. Neuron-inspired ferroelectric bioelectronics for adaptive biointerfacing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2416698.

72. Ji, R.; Yan, S.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Ureido-ionic liquid mediated conductive hydrogel: superior integrated properties for advanced biosensing applications. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2401869.

73. Keynes, R. D. The ionic channels in excitable membranes. In Ciba Foundation Symposium 31 ‐ Energy Transformation in Biological Systems; Wolstenholme, G. E. W., Fitzsimons, D. W., Eds.; Novartis Foundation Symposia, Vol. 31; Wiley, 2008; pp 191-203. DOI: 10.1002/9780470720134.ch11.

74. Li, Z.; Lu, J.; Ji, T.; et al. Self-healing hydrogel bioelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2306350.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].