Modulating multi-ion dynamics for high-performance iontronic systems

Abstract

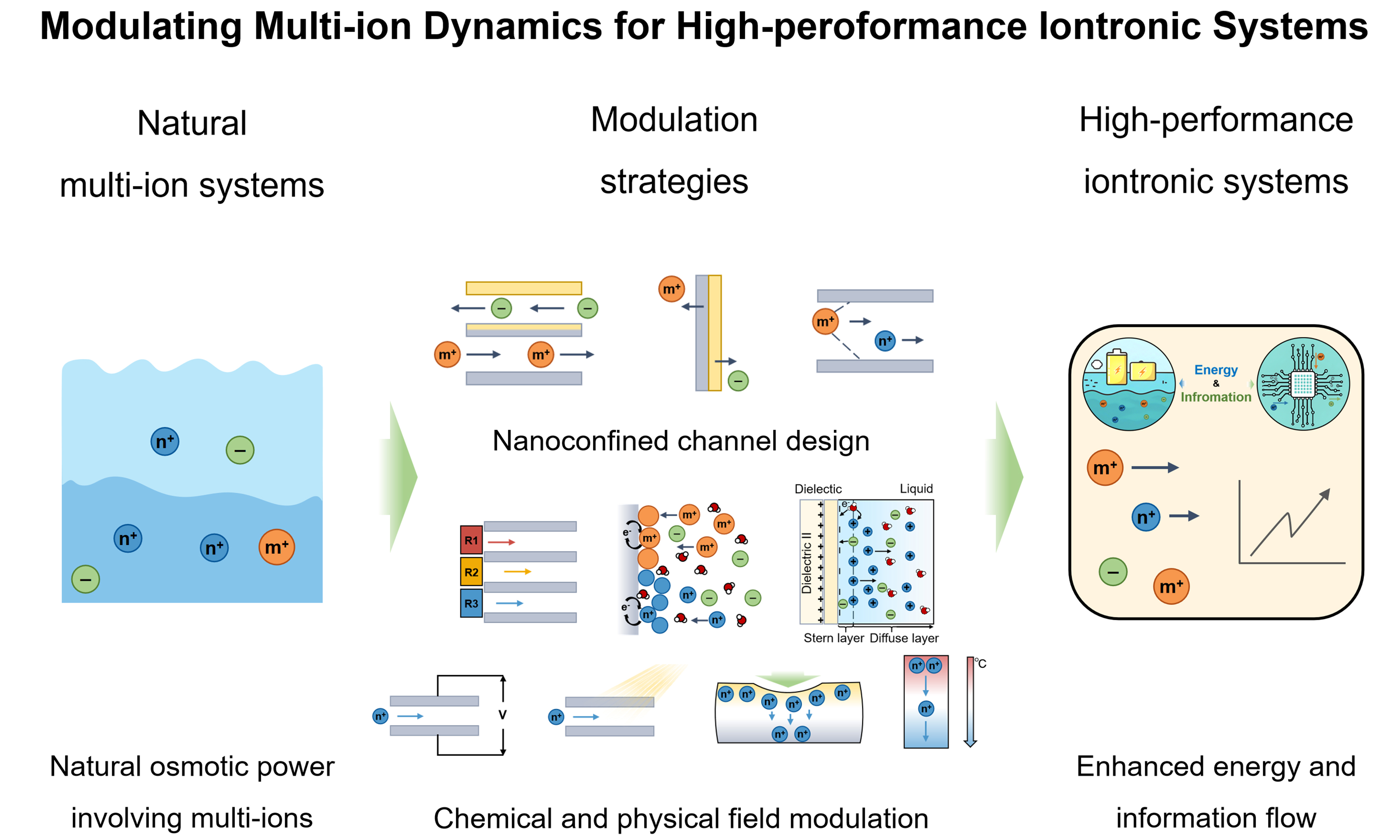

In nature, iontronic power generation often arises from complex mixtures of monovalent and multivalent ions, exemplified by osmotic power between seawater and river water. In contrast, most laboratory studies have relied on single-ion systems, overlooking the intricate interplay and additional free energy associated with multi-ion environments. Efficiently harvesting energy from such multi-ionic systems remains challenging due to strong ion-ion interactions, the inherent trade-off between ionic selectivity and permeability, and the limited efficiency of multi-ionic-electronic coupling at interfaces. Recent advances in iontronics offer new pathways to overcome these barriers by modulating multi-ionic dynamics through nanofluidic channel design, interface engineering, and external-field regulation. These approaches enable selective transport, cooperative migration, and dynamic coupling among diverse ions, thereby enhancing energy conversion efficiency and device stability. Looking ahead, the rational control of multi-ion interactions and transport dynamics may unlock a new generation of high-performance iontronic power sources rooted in natural multi-ionic systems.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Multi-ion dynamics are ubiquitous in both natural and artificial systems, underpinning a wide range of processes, including neural signal transmission[1,2], metabolic energy conversion[3,4], and ionic conduction in synthetic devices[5,6]. In biology, the orchestrated transport of multiple ion species ensures precise information coding and efficient energy utilization. For instance, in the nervous system, the propagation of nerve impulses relies on the coordinated influx of Na+ ions and efflux of K+ ions across neuronal membranes, enabling the continuous and stable transmission of action potentials along nerve fibers[7]. Upon reaching synaptic terminals, the arriving action potential activates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, inducing Ca2+ influx, which subsequently triggers the rapid release of neurotransmitters from synaptic vesicles into the synaptic cleft, thereby mediating information transfer between neurons[2]. Beyond neural signaling, ionic dynamics also underpin biological energy supply. In mitochondria, electrons derived from the oxidation of metabolic substrates - such as Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) generated during glucose metabolism - are transferred along the electron transport chain to drive proton pumps that transport H+ ions across the inner mitochondrial membrane, establishing a transmembrane proton gradient[8]. The subsequent passive transport of H+ ions back through ion channels (i.e., osmosis) converts the stored electrochemical potential into free energy that drives the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate. Similarly, mechanosensitive ion channels in skin tactile cells transduce external mechanical stimuli into Na+ influx, generating tactile action potentials[9,10]. In contrast, in visual systems, photon-induced conformational changes of rhodopsin in rod and cone cells initiate a cascade of receptor-mediated processes that ultimately produce ionic neural signals[11,12]. Collectively, these biological processes illustrate that ionic species and their electrochemical potentials serve as the fundamental physicochemical basis for signal encoding, transmission, and amplification, while being intrinsically coupled to metabolic energy input.

In contrast, many artificial iontronic systems have traditionally emphasized the transport of a single dominant ion while neglecting the coexistence, competition, and cooperative interactions among multiple ionic species[4,13]. This simplification has constrained both the efficiency and functionality of energy-harvesting technologies. For example, osmotic power generation from the ocean, commonly termed “blue energy”, inherently involves a complex mixture of ions, including Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl- and SO42-[14]. Nevertheless, most laboratory-scale studies have concentrated on harvesting the flux of individual ions, primarily due to the complexity of ion-ion interactions and the intrinsic trade-off between selectivity and permeability in ion-exchange membranes[15]. As a result, achieving simultaneous high selectivity and sufficient ionic flux across multiple ion species remains a formidable challenge, hindering the effective utilization of multivalent and coexisting ionic signals. In such a multi-ionic system, differences in ion valence, mobility, solvation structure, and interfacial affinity may lead to competitive or cooperative interactions that collectively determine ionic transport behavior, local electric-field distribution, and interfacial dynamics. In this context, iontronic systems offer an ideal platform to probe and exploit multi-ion dynamics[16,17]. Iontronic power refers to a class of energy harvesting and storage systems in which ionic dynamics are actively modulated through material, physical and chemical strategies, inducing efficient, directional ion transport and generating ionic current. By transcending the traditional focus on single-ion transport, the controlled modulation of multi-ion dynamics enables enhanced energy conversion efficiency, expanded device functionality, and seamless integration with biological and soft-matter systems.

Herein, we first underscore the fundamental significance of multi-ion systems in iontronic power technologies, detailing their critical roles in ionic-electronic energy transduction, including intrinsic ion properties, interionic interactions, and multi-ion-electronic coupling at interfaces. We then review recent strategies for regulating multi-ion dynamics through material design, interfacial chemistry, and external physical fields. Building on these advances, we outline potential approaches for achieving more precise control, including hierarchical channel architectures for selective ion transport and machine-learning (ML)-assisted external-field modulation. Looking forward, deliberate modulation of multi-ion dynamics promises not only to advance our understanding of iontronic processes but also to accelerate the development of next-generation energy, sensing, and bio-interfacing technologies.

HOW MULTI-ION INTERACTIONS GOVERN IONTRONIC POWER CONVERSION

In a typical iontronic device, ions are transported through ion-conductive media and are subsequently converted into electronic signals at electrochemical or electrode interfaces via redox reactions or electric double-layer (EDL) processes[18]. Specifically, ionic conductors such as aqueous or solid electrolytes, gel polymer electrolytes, and hydrogels primarily serve as ion-transport media, providing continuous pathways for ion migration, the formation of concentration gradients, and multi-ion modulation in soft or confined environments[19-21]. Nanostructured and nanoconfined materials, including layered oxides, graphene oxide (GO), and MXenes, further enable directional and selective ion transport by amplifying nanoconfined effects and interfacial interactions[22-24]. In contrast, electronic conductors and mixed ionic-electronic conductors, such as carbon-based electrodes, metals, metal oxides, and conducting polymers, play a dominant role at interfaces, where ionic signals are coupled to electronic currents through redox reactions or EDL charging[25,26]. It is the deliberate integration of these complementary material systems and the interfacial ionic-electronic coupling that underpins the operation of iontronic devices.

Therefore, the performance of iontronic power systems is closely related to the intrinsic properties of the transported ions. The differences of valence state, size, charged state and hydration energy of different ions not only determine their transport behavior in confined space and interface, but also deeply affect the charge distribution and energy conversion process of the system[13,27,28]. In the multi-ion system, the electrostatic effect, the shielding effect and the short-range interaction jointly regulate the dynamic behavior of ions. Competition and cooperative transport further determine the ionic selectivity and conductivity, while ionic-electronic coupling at the electrode interface would affect the efficiency of charge storage and transformation. These complex and coupled processes work together to determine the energy density, energy efficiency, and functional adaptability of ion power sources in different environments.

Intrinsic properties of ions

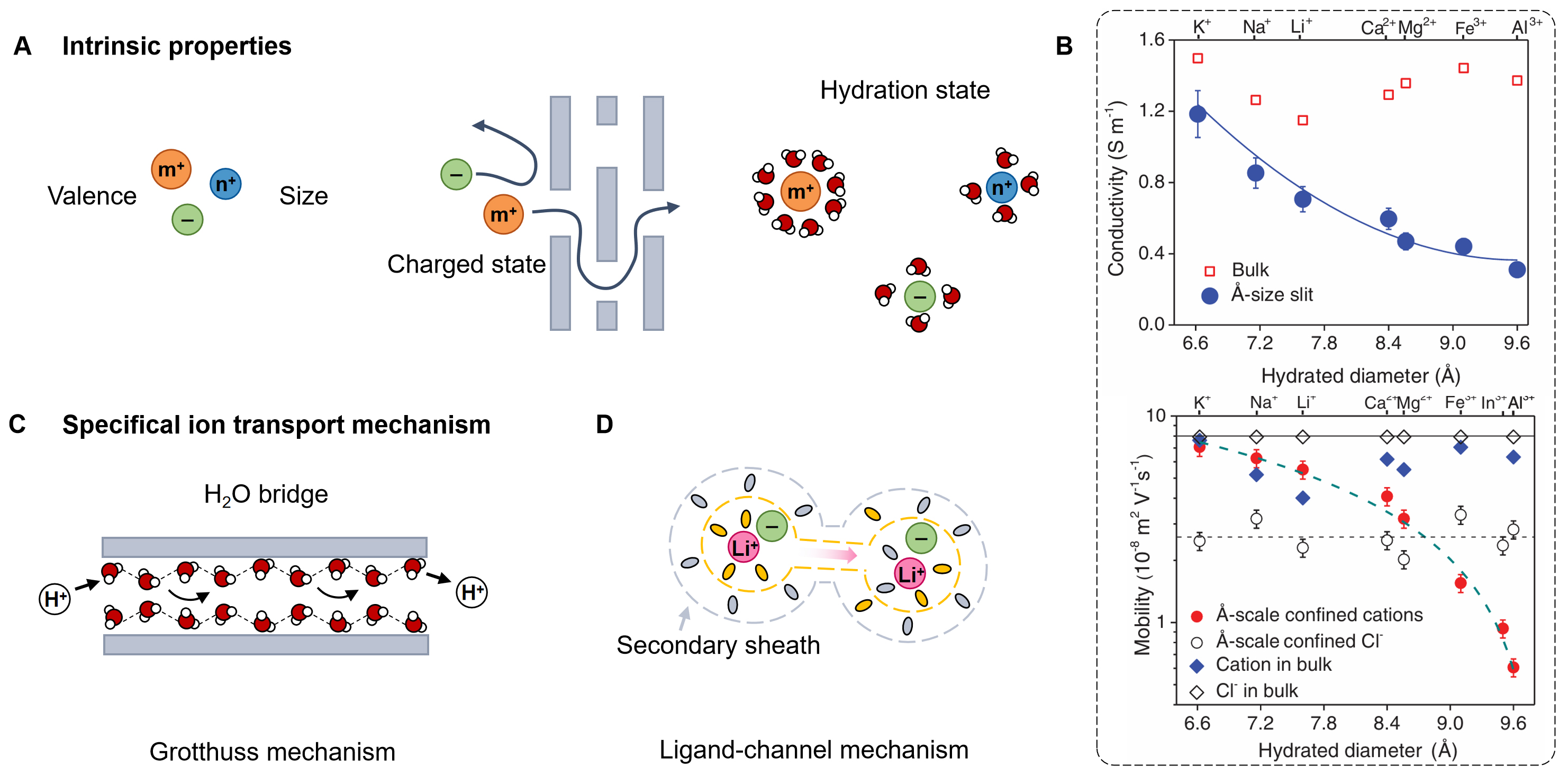

One of the key distinctions arises from their intrinsic physicochemical properties [Figure 1A], which dictate the charge-carrying capacity and mobility of ions, particularly within nanofluidic systems. As shown in Figure 1B, monovalent ions, such as Na+, K+, and Li+, usually migrate rapidly because they face smaller hydration barriers and weaker electrostatic binding[29]. This enables them to sustain high ionic flux and conductivity, although the charge density they deliver per ion remains relatively low. In contrast, multivalent ions such as Ca2+, Mg2+, or Al3+ can, in principle, contribute more charge per unit, but their ionic flux is lower[29]. Another intrinsic factor is electrostatic interaction based on charge state. Cations and anions interact asymmetrically with charged channel walls or electrode surfaces owing to the presence of EDLs, resulting in preferential ion transport behaviors[3]. For instance, cations are typically favored in negatively charged nanofluidic channels, while anions dominate in positively charged or suitably functionalized systems[30,31]. This charge-state-dependent selectivity profoundly influences the electrochemical potential gradient across the interface, thereby governing ionic selectivity and energy conversion efficiency. Moreover, ionic hydration energy and effective radius play pivotal roles in modulating ion transport dynamics[32,33]. The ability of ions to shed or reorganize their hydration shells dictates their accessibility to confined spaces and proximity to solid-liquid interfaces[29]. For instance, lithium ions possess high hydration energy and a large hydration shell, which substantially hinders their mobility within narrow pores (Figure 1B, bottom). In contrast, weakly hydrated ions such as K+ and Na+ can traverse confined pathways more readily. These hydration-dependent size effects underpin the intrinsic trade-off between ionic selectivity and permeability in nanofluidic membranes and channels[32]. In addition, ion mobility can be markedly enhanced by specialized transport mechanisms. Protons (H+) and hydroxide ions (OH-) exhibit exceptionally high mobility through the Grotthuss hopping mechanism [Figure 1C], in which charge is transmitted along a hydrogen-bonded network rather than by the physical diffusion of hydrated ions[34,35]. Recent studies have revealed that solvated Li+ ions can be extracted from their secondary solvation sheath through the use of tailored electrolytes, forming rapid ion-conduction ligand channels that significantly enhance ion transport[36] [Figure 1D]. This ligand-channel mechanism is broadly applicable and can be extended to other metal-ion battery electrolytes. Such unique transport behavior enables ultrafast ion conduction and supports higher power output than conventional hydrated-ion migration, offering distinct advantages for iontronic power sources.

Figure 1. Intrinsic factors of multi-type ions. (A) Schematic of the intrinsic ionic properties, including valence state, size, charge, and hydration state; (B) Conductivity of various 0.1 M electrolytes measured in a device with bulk graphite walls and single-layer angstrom-size slit MoS2 spacers (top). Ion mobility under confinement as a function of different hydrated diameters (bottom). This figure is quoted with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science[29]; (C) Schematic of the Grotthuss mechanism; (D) Schematic of the ligand-channel mechanism.

Interaction between ions

Interactions among ions play a decisive regulatory role in iontronic power systems, as they directly govern ion transport pathways, electric field distribution, and interfacial charge dynamics. These interactions originate from a combination of Coulombic forces, volume effects, and the structure and rearrangement of hydration shells, all of which become increasingly pronounced under nanoconfinement and interfacial coupling. Depending on the ionic composition, confinement geometry, and operating conditions, ion-ion interactions may manifest as either competitive or cooperative transport behaviors, thereby exerting opposite influences on ionic mobility, selectivity, and internal resistance.

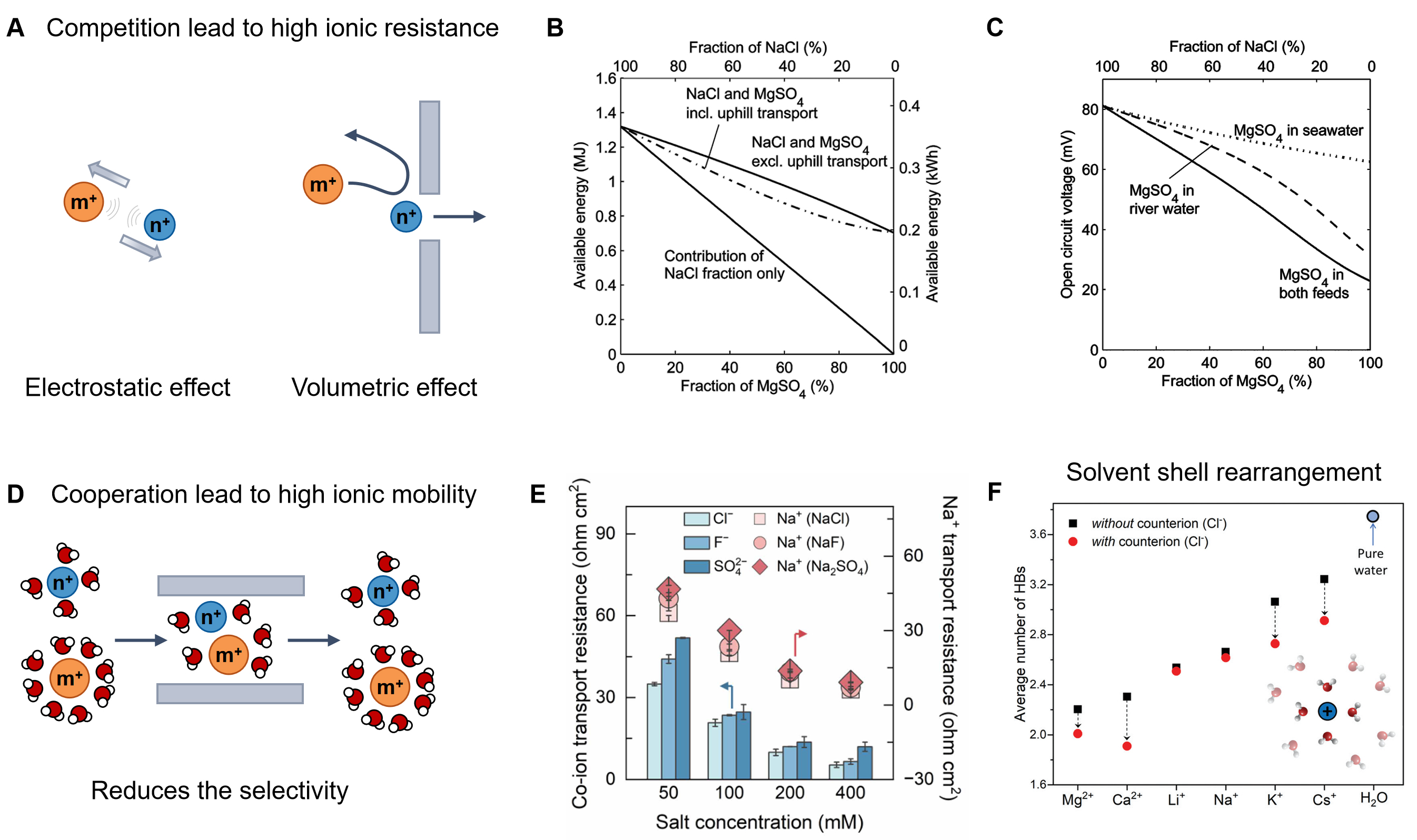

Competitive transport typically dominates when multiple ionic species simultaneously access limited transport channels or adsorption sites at confined interfaces [Figure 2A]. This scenario is most prevalent in strongly charged nanochannels or membranes under low-to-moderate ionic strength, where ions compete for energetically favorable pathways. Such competition reduces effective ion mobility and selectivity, leading to an increase in internal resistance during energy conversion. For example, the introduction of divalent ions (e.g., Mg2+) into osmotic power systems significantly increases membrane resistance, resulting in reduced open-circuit voltage and power density[13,28] [Figure 2B and C]. This behavior can be attributed to the stronger electrostatic interactions between divalent ions and negatively charged channel walls compared with monovalent ions such as Na+, which effectively hinders Na+ migration. Consequently, competitive ion-ion interactions suppress selective transport and degrade overall energy-harvesting efficiency.

Figure 2. Interactions between ions. (A) Schematic of the ion-ion competitive interactions; (B) The osmotic power and (C) Open circuit voltage in NaCl varies with the concentration of divalent Mg2+ salt. Those figures are quoted with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry[13]; (D) Schematic of the ion-ion cooperative interactions; (E) Ion transport resistance with increasing salt concentration. This figure is quoted with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science[38]; (F) Average number of hydrogen bonds (HBs) in the first hydration shell of metal ions with and without the counterions. This figure is quoted with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry[42].

Beyond competition, ions can also exhibit cooperative transport behavior under specific conditions. Cooperative interactions emerge from enhanced electrostatic correlations among ions, as well as between ions and channel walls[37,38], and are further facilitated by solvent-layer rearrangements within confined spaces[39] [Figure 2D]. To maintain electroneutrality, co-ion transport frequently occurs in systems such as bipolar membrane electrodialysis[40]. Notably, under high ionic strength or strong external electric fields, increasing salt concentration can reduce overall system resistance by promoting correlated co-ion motion, as illustrated in Figure 2E. While such cooperative transport stabilizes ionic flux and improves charge-transfer efficiency across membranes, it often occurs at the expense of reduced ionic selectivity[38].

In multicomponent ionic systems, the coexistence of different ions further induces continuous reorganization of solvation shells[41-43]. Each ionic species perturbs the local hydration environment, dynamically modifying the effective ionic size, interaction strength, and transport characteristics[42] [Figure 2F]. Depending on the ionic composition, these hydration rearrangements can either impede or facilitate channel permeation. In particular, cooperative hydration effects that weaken desolvation barriers can significantly enhance transport efficiency. For instance, stable metal ion-water networks formed through strong ion-ion interactions have been shown to promote proton transport, delivering superior rate performance in confined iontronic systems[44].

Overall, the dominance of competitive or cooperative ion-ion interactions is not intrinsic to a specific material or device architecture; rather, it emerges from the combined effects of ion valence, concentration, confinement scale, interfacial charge density, hydration structure, and external driving fields. Understanding and deliberately regulating this balance provides a powerful strategy for optimizing ion transport, selectivity, and energy conversion efficiency in advanced iontronic power systems.

Ionic-electronic coupling interfaces

The essence of iontronic power conversion resides in ionic-electronic coupling at interfaces, which dictates both the efficiency and directionality of converting ionic energy into electronic signals[45]. In multi-ion systems, such interfaces are not passive charge-exchange boundaries but highly dynamic regions where ionic transport and electronic response are strongly interdependent. The local interfacial behavior is jointly governed by ion species, concentration distributions, migration dynamics, and solvation characteristics, while simultaneously being regulated by the electronic properties of the electrode. As a result, iontronic power generation emerges from a bidirectional feedback process rather than a unidirectional transduction pathway.

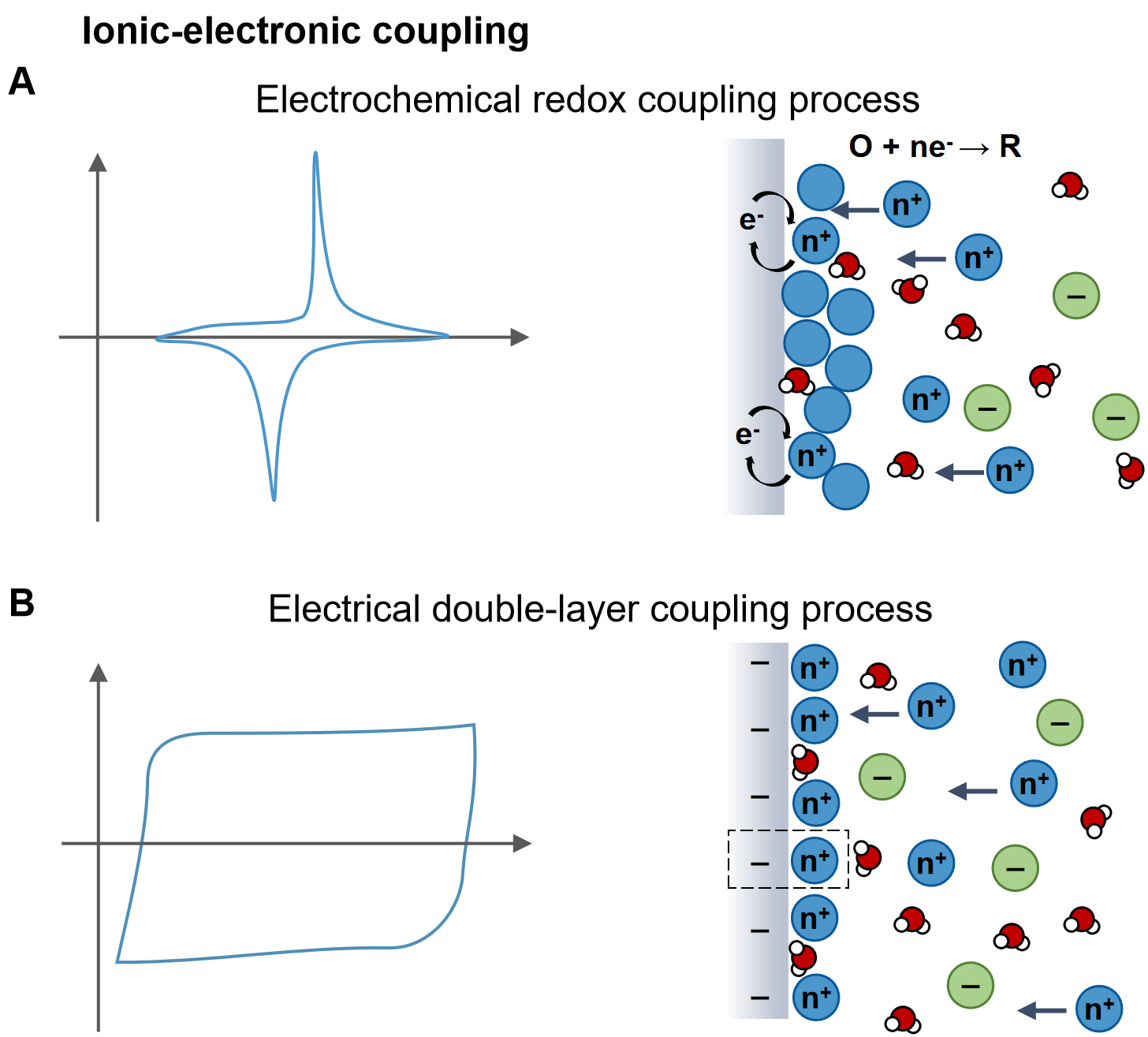

At electrochemical interfaces, ionic transport directly controls redox reaction kinetics by regulating the availability, identity, and local concentration of reactive species [Figure 3A]. Ions participating in redox reactions convert ionic free energy into electrical energy through electron transfer, with reaction reversibility and rate determined by the redox activity, reaction potential, and coordination environment of each ion. Redox-active species, such as protons (H+), hydroxide ions (OH-), and multivalent transition-metal ions (Zn2+, Cu2+, Co2+)[46], typically dominate interfacial charge-transfer processes due to their favorable energetics. In contrast, inert ions such as Na+ or K+ do not directly participate in electron transfer but instead modulate local electric fields, screen interfacial charges, and reshape reaction pathways. In multi-ion systems, competitive adsorption, cooperative accumulation, and differential migration of multiple ionic species collectively determine interfacial potential distributions and reaction barriers, thereby directly influencing energy conversion efficiency and power output[47]. Meanwhile, the electronic properties of the electrode, including work function alignment and density of states[48], could govern electron injection and extraction rates, feeding back to influence interfacial potential drops and ionic redistribution. This mutual constraint establishes a coupled kinetic bottleneck at the ionic-electronic interface.

Figure 3. Basic types of ionic-electronic coupling interfaces. Schematic of (A) Electrochemical redox processes and (B) Electrical double-layer processes.

Beyond Faradaic processes, ionic-electronic coupling also occurs through EDL dynamics, where ion adsorption, desorption, and rearrangement generate time-dependent interfacial electric fields that drive non-Faradaic energy conversion [Figure 3B]. In multi-ion environments, the structure and dynamics of the EDL are strongly ion-specific. Selective adsorption of cations and anions modulates surface potential, interfacial capacitance, and charging dynamics[49]. Multivalent ions often amplify interfacial electric fields and enhance energy-storage capacity, whereas small or strongly hydrated ions, such as H+ or K+, tend to retain stable solvation shells that limit direct interfacial charge exchange[50-52]. These microscopic ion-dependent processes collectively define interfacial capacitance, energy density, and response speed. Furthermore, short-range ion-ion interactions, including hydrogen bonding and ion pairing, together with solvent polarization effects, strongly influence EDL reconstruction, giving rise to nonlinear coupling between ionic transport and electronic response[53-55].

Overall, the ionic-electronic coupling interface in multi-ion systems constitutes a critical node where ionic transport dynamics and electronic response are continuously co-regulated, ultimately determining iontronic power performance. By engineering interfacial architectures, such as constructing heterointerfaces, introducing surface functional groups, or imposing nanoscale confinement, and by judiciously selecting ion species, including mixed-valence or multivalent ions, synergistic enhancement of both electrochemical reactions and EDL processes can be achieved. Recent studies further demonstrate selective ion transport and response by mimicking the target-recognition mechanisms of biological ion channels, exploiting intrinsic ionic properties to interact selectively with channels or material interfaces[56]. Such interfacial coupling not only underpins the performance of iontronic power sources and self-powered sensing systems, but also establishes the physicochemical foundation for next-generation iontronic devices capable of adaptive energy conversion and signal-responsive functionality[57].

Ionic dynamics in different confined systems

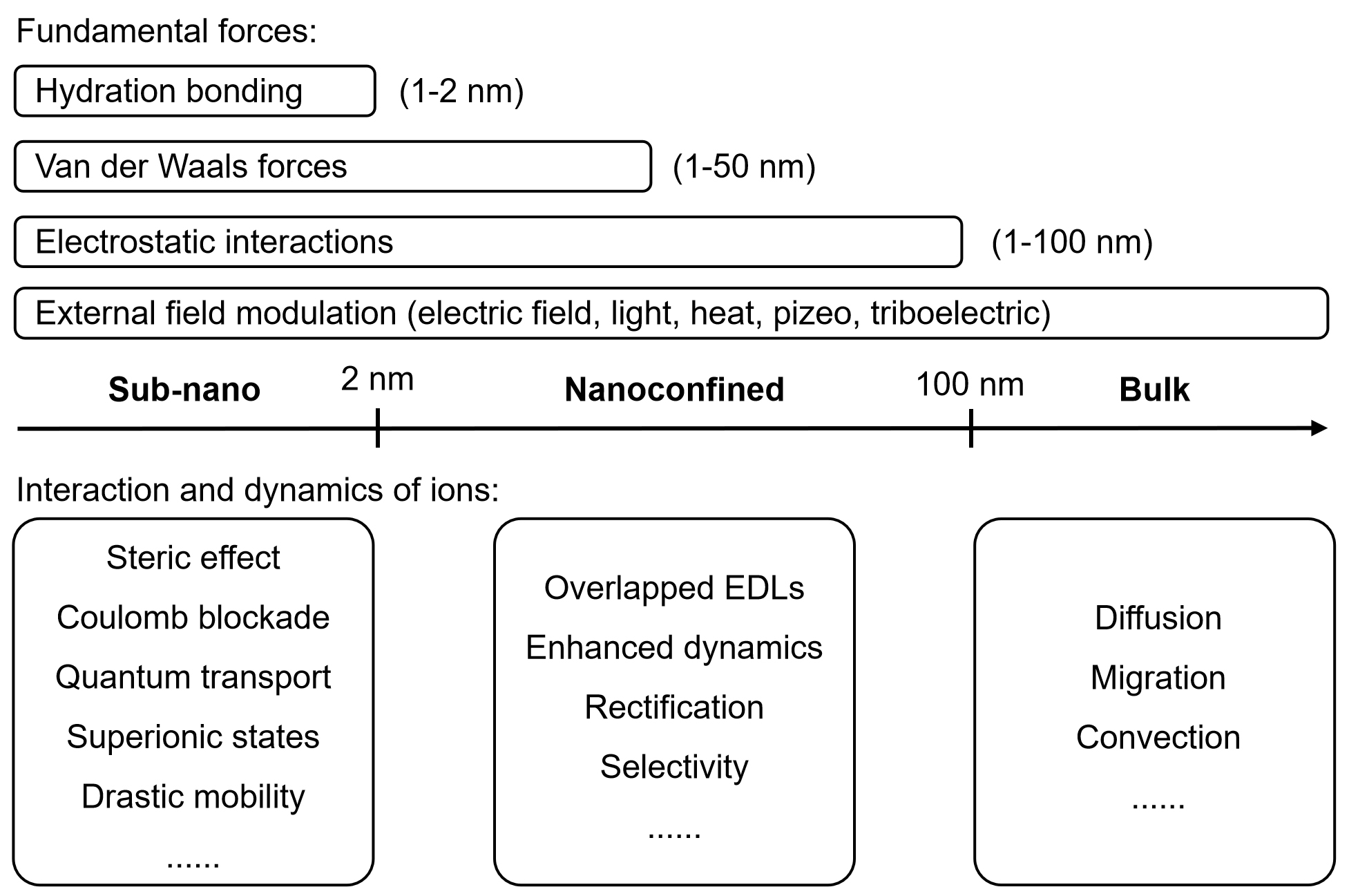

The ion dynamics in multi-ionic systems are fundamentally governed by the degree of spatial confinement, which determines how ions interact, transport, and couple with electronic processes at interfaces. Depending on the characteristic dimension of the confined environment, ionic behavior transitions from bulk diffusion to strongly correlated and quantized transport, profoundly affecting the energy conversion and storage performance of iontronic systems. Generally, three regimes can be distinguished: bulk systems (> 100 nm), nanoconfined systems (2-100 nm), and sub-nanoconfined systems (< 2 nm), each exhibiting distinct physicochemical characteristics and coupling mechanisms[58] [Figure 4].

Figure 4. Various length scales of fundamental forces and interaction of ions. EDL: Electric double-layer.

In bulk systems, ions exist in a relatively homogeneous environment dominated by long-range electrostatic interactions screened by the solvent. The ionic transport follows classical diffusion and migration behaviors, governed by concentration gradients or external electric fields[59]. Consequently, energy conversion processes, such as redox reactions and EDL formation, are primarily controlled by ionic concentration and mobility. When the characteristic dimension is reduced to the nanoconfined range (2-100 nm), ionic dynamics become increasingly influenced by the surrounding interfaces and structural heterogeneity[17]. Here, the effective dielectric environment, surface charge density, and pore geometry induce partial EDL overlap, leading to ion-selective transport and enhanced coupling with surface potential fluctuations. These factors jointly redefine how ions interact with both their surrounding solvent molecules and the confining surfaces, leading to unconventional transport behaviors that underpin modern iontronic technologies. The spatial range of these interactions is primarily determined by surface proximity, such as pore dimensions or the reduction of interlayer spacing, and encompasses several fundamental forces. These include steric and hydration interactions acting over 1-2 nm, van der Waals forces extending roughly 1-50 nm, and electrostatic interactions dominating within 1-100 nm[58,60]. Specifically, hydration interactions, governed by hydrogen bonding, are typically repulsive; bringing two hydrophilic surfaces closer requires breaking the intervening hydrogen-bond network. Van der Waals forces, in contrast, originate from transient dipoles induced by fluctuations in local charge distributions. Electrostatic interactions, manifested through the formation of an EDL or characterized by the Debye screening length, generally span 1-100 nm depending on the ionic environment. Nanoconfined systems can induce both competitive and cooperative interactions among ions and solvent molecules, including preferential adsorption, selective migration, and electrostatic screening, which dynamically reshape the local potential landscape[22,61]. For example, previous studies have shown that different cations can exhibit a “fixing effect” on GO layers, effectively preventing the interlayer spacing from swelling[62]. This fixing effect results from cation adsorption at regions where oxygen-containing groups and aromatic domains coexist. As a consequence, the confined channel leads to enhanced ionic selectivity, efficiently blocking cations with larger hydration volumes.

The interplay between nanoconfined ion ordering and electrochemical reactivity could also result in improved charge storage efficiency and tunable redox kinetics[63,64]. At the extreme sub-nanoconfined scale (< 2 nm), ionic behavior deviates markedly from continuum theories and enters the regime of discrete and correlated transport. In these ultranarrow channels, ions experience strong steric hindrance, dehydration, and quantum-level electrostatic interactions[65,66]. The effective ion size, valence, and hydration structure dominate mobility and selectivity, while strong electrostatic correlations and ion-surface interactions induce phenomena such as Coulomb blockade[65], superionic states[67], and drastic changes in diffusion coefficients[68]. Sub-nanoconfinement could break charge symmetry and establish directional ion flows or rectification effects, significantly enhancing the energy transduction efficiency of iontronic devices. Moreover, the coupling between confined ion transport and interfacial electronic states can lead to emergent behaviors such as nonlinear conductance and memory-like response[69,70], offering new opportunities for multifunctional energy and neuromorphic applications. Nanoconfined systems therefore offer a powerful platform for coupling ionic and electronic processes with high precision, enabling efficient iontronic energy conversion and signal modulation.

Overall, the degree of nanoconfinement emerges as a key design parameter for regulating multi-ion dynamics and optimizing iontronic power systems. By rationally engineering confinement geometry, surface chemistry, and charge distribution, selective ion transport and synergistic coupling of electrochemical and capacitive processes can be achieved across multiple scales. This confinement-guided control of ionic dynamics offers a pathway toward high-performance, multifunctional iontronic devices, capable of delivering elevated energy density, enhanced conversion efficiency, and broad environmental adaptability.

STRATEGIES TO MODULATE MULTI-ION DYNAMICS

In multi-ion systems, ion migration is governed by a combination of factors, including charge, ionic size, hydration structure, and interionic interactions. Consequently, multi-dimensional strategies are required to effectively modulate ion dynamics. Current research approaches remain relatively limited, largely focusing on bidirectional transport kinetics of cations and anions[71,72], whereas strategies for simultaneously directing the transport of multiple ions in a single direction are scarce. Existing regulatory methods can be broadly categorized into three approaches: material design, chemical modulation, and physical field modulation. These strategies provide essential tools for probing and controlling the complex behavior of multi-ion systems. Nonetheless, achieving higher spatial resolution, stronger directionality, and programmable control of multi-ion transport remains a critical challenge for future research.

Material strategies

Material engineering offers a versatile and foundational strategy for regulating multi-ion dynamics by tailoring the physicochemical properties of ion transport pathways. To modulate multiple ion species, a common intrinsic feature may be the incorporation of multiregional designs within the material, where different regions possess distinct ion transport capabilities. In addition, selective interactions between ions and the channel wall - such as specific chemical affinity, coordination, or hydration-structure matching - can also be harnessed to achieve selective and multi-ionic regulation. By precisely designing channel architectures, surface chemistries, and internal microenvironments, materials design can realize selective, efficient, and directional ion transport, which is essential for high-performance iontronic power systems.

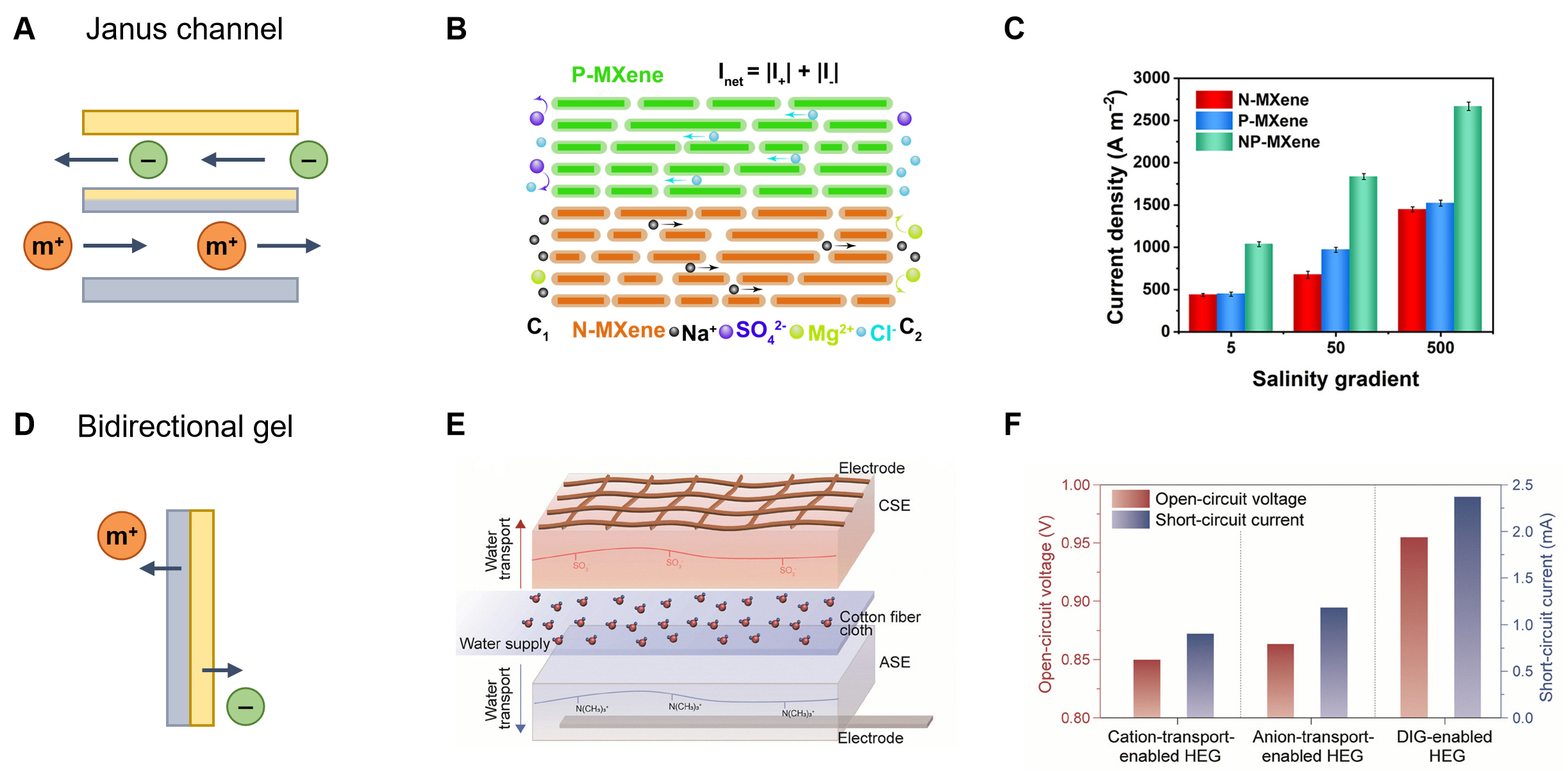

In nanoconfined channels, material engineering provides a classical yet powerful strategy by tuning channel dimensions, modulating surface charge distributions, and constructing Janus-type asymmetric

Figure 5. Material strategies to modulate multi-ion dynamics. (A) Schematics of the Janus channel; (B) Schematic of the ion diffusion in NP-MXene with the left side (C1) being a high concentration of MgCl2 and a low concentration of Na2SO4 solution and the right side (C2) being a high concentration of Na2SO4 and a low concentration of MgCl2 solution. This figure is quoted with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science[72]; (C) Comparison of osmotic current densities for different types of MXene. This figure is quoted with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science[72]; (D) Schematics of the bidirectional gel; (E) Schematic illustration of the DIG-enabled HEG structure. This figure is quoted with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry[73]; (F) Open-circuit voltage and short-circuit current of traditional HEGs and the DIG-enabled HEG. This figure is quoted with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry[73]. N-MXene: Negatively charged MXene; P-MXene: positively charged MXene; CSE: cation-selective electrolyte; ASE: anion-selective electrolyte; HEG: hydrovoltaic electricity generation; DIG: dual-interfacial gating.

Material engineering further enables the manipulation of multi-ion dynamics through chemical design, including heterogeneous or dipolar gel membranes and surface functionalization, which precisely tailor the solvation environment and transport pathways of ions[40,73-75] [Figure 5D]. By integrating regions of distinct polarity, charge density, or dielectric constants, these materials induce spatially varying solvation energies and electrostatic fields, leading to bidirectional or differential transport of cations and anions within a single system. For example, by establishing spatially segregated pathways for cation and anion migration, a dual-interfacial gating architecture was proposed, enabling simultaneous, bidirectional ion transport and significantly enhancing the utilization of ionic current to 1.48 mA cm-3[73] [Figure 5E and F]. Specifically, -SO3Na and -N(CH3)3Cl functional groups were introduced into the hydrogel polymer backbone to impart cation and anion selectivity, respectively, allowing Na+ and Cl- ions to be independently transported on opposite sides of the membrane. This design highlights a key feature of multi-ion systems, namely the coordinated regulation of different ionic species within a single device. Moreover, the ability of this system to directly interface with human skin and continuously harvest sweat ions for over 3 h further demonstrates its robustness in complex, real-world multi-ion conditions. Beyond Na+/C- systems, such an architecture is, in principle, extendable to more complex multi-ion environments, such as real seawater and river water, enabling the harvesting and regulation of multiple ions including Ca2+, Mg2+, Br- and I-. This performance originates from the establishment of independent ion-selective pathways in antagonistic hydrogels, effectively maximizing charge carrier utilization while ensuring precise ionic transport control. In addition, the incorporation of polar functional groups, such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, or amine moieties, further reconfigures local hydrogen-bonding networks and modifies ion-solvent coupling[74]. As a result, the solvation shells and re-solvation dynamics can be tailored to favor specific ionic species or transport directions[75].

In addition, chemical environment modifications within channels provide a highly tunable strategy to regulate ion binding energies and migration barriers. Incorporating polar functional groups, proton donor/acceptor sites, or coordination-active moieties within the confined spaces enables precise tailoring of the free-energy landscape for ion transport[76-78]. For example, coordinating ligands, such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), enable transient ion capture and release in the 2D metal-organic framework backbone, achieving reversible and selective transport of metal cations[77]. This approach allows selective discrimination based on ionic valence states. In mixed-salt systems, EDTA selectively chelates divalent cations (e.g., Mg2+), while monovalent ions (e.g., K+) are regulated through electrostatic interactions and selective transport. This ligand-mediated strategy allows selective discrimination among multiple ionic species based on valence state and coordination chemistry, demonstrating a fundamentally different multi-ion regulation mechanism compared to size- or charge-based exclusion. Similarly, proton-conductive sites such as sulfonic or amino groups facilitate Grotthuss-type hopping and enable ultrafast H+ conduction[2,7]. Moreover, engineering hydrophobic-hydrophilic microdomains allows dynamic control over dehydration and rehydration processes, optimizing both selectivity and transport rate[79]. Such chemical environment modification of nanoconfined channels transforms ion transport from a passive diffusion process into an actively tunable, stimuli-responsive behavior.

Chemical strategies

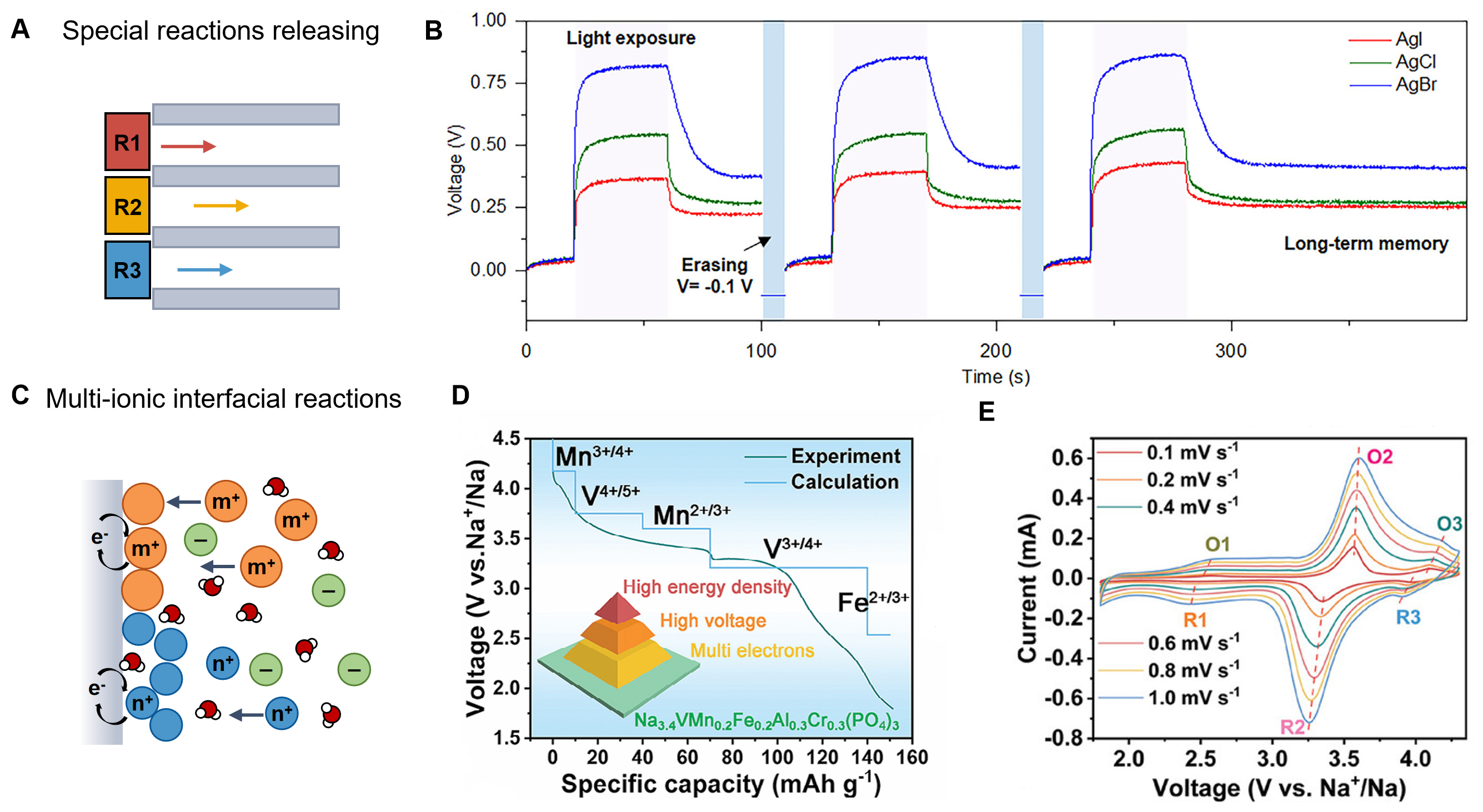

Chemical strategies provide powerful means to precisely regulate multi-ion dynamics in iontronic systems by tailoring interfacial reactions, local chemical environments, and ion-channel interactions. These strategies can generally be categorized into ordered and disordered approaches, depending on whether the ion transport is guided by well-defined pathways or governed by coupled chemical reactions at heterogeneous interfaces.

Through ordered chemical regulation, material engineering combines rationally designed redox-active interfaces with structurally defined nanoconfined ion channels to achieve selective, independent transport of multiple ions without mutual interference [Figure 6A]. For example, a photochemical iontronic system was developed that exploits controlled multi-ion transport within nanoconfined channels, coupled with precisely engineered photochemical redox reactions, to generate high-throughput iontronic signals[80]. By coupling the light-triggered silver halide (AgX, where X = Cl, Br, and I) redox reactions with anionic transport in positively charged nanoconfined channels of anodic aluminum oxide (AAO), specific photovoltages of about 0.88, 0.7, and 0.3 V can be detected at one pixel [Figure 6B]. The integration of redox-active moieties into well-defined nanochannels further allows modulation of the local potential and interfacial ion distribution, thereby achieving controlled ion migration with high selectivity and directionality. Such ordered chemical frameworks could be an effective way to improve both energy conversion efficiency and device stability in iontronic power systems.

Figure 6. Chemical strategies to modulate multi-ionic dynamics. (A) Schematics of the ordered redox-active interfaces and nanoconfined channels to modulate multi-ion dynamics; (B) Characteristic photovoltages of each iontronic with light writing (purple region) and voltage erasing (blue regions). This figure is quoted with permission from Elsevier inc.[80]; (C) Schematics of the disordered multi-ionic interfacial reactions to modulate ion dynamics; (D) The experimental and calculated voltage profiles of the cathode. This figure is quoted with permission from John Wiley and Sons[82]; (E) CV curves at different scan rates of the cathode. This figure is quoted with permission from John Wiley and Sons[82].

In contrast, disordered chemical regulation relies on the coexistence and coupling of multiple chemical reactions involving various ions at complex interfaces. These reactions include interfacial redox, coordination, and intercalation processes, where different ions directly participate in electron transfer, complex formation, or lattice insertion[81] [Figure 6C]. For example, a high-entropy Na alloy cathode was designed, where the entropy-driving stepwise Fe2+/Fe3+, V3+/V4+/V5+, Mn2+/Mn3+/Mn4+, and Cr3+/Cr4+ redox couples could trigger the multi-ion and electron transfer chemistry[82]. Consequently, it exhibits a high reversible capacity of 151.3 mAh g-1 with an admirable energy density of 520.5 Wh kg-1. The Na-insertion voltage platform of each ionic redox couple is verified by theoretical calculation and experimental discharge curve and cyclic voltammetry (CV) profiles [Figure 6D and E]. In this condition, redox reactions may proceed concurrently with ion coordination to surface functional groups or transition-metal sites, dynamically reshaping the interfacial charge distribution and ion migration pathways. Similarly, intercalation reactions within layered or amorphous materials can accommodate multiple ionic species with varying valence states, enabling adaptive charge storage and conversion[83]. Unlike ordered systems, these disordered processes often generate dynamic and self-regulating ionic environments, leading to emergent behaviors such as cooperative ion transport, fluctuating EDL structures, and nonlinear ionic-electronic coupling.

Overall, chemical regulation provides a versatile toolbox for controlling multi-ion dynamics across ordered and disordered regimes. By combining precise interfacial redox design with multi-reaction coupling, it becomes possible to synchronize ionic transport and electronic conduction, optimize reaction kinetics, and construct adaptive, multi-functional iontronic power systems capable of efficient energy transduction and self-regulated signal response.

Physical strategies

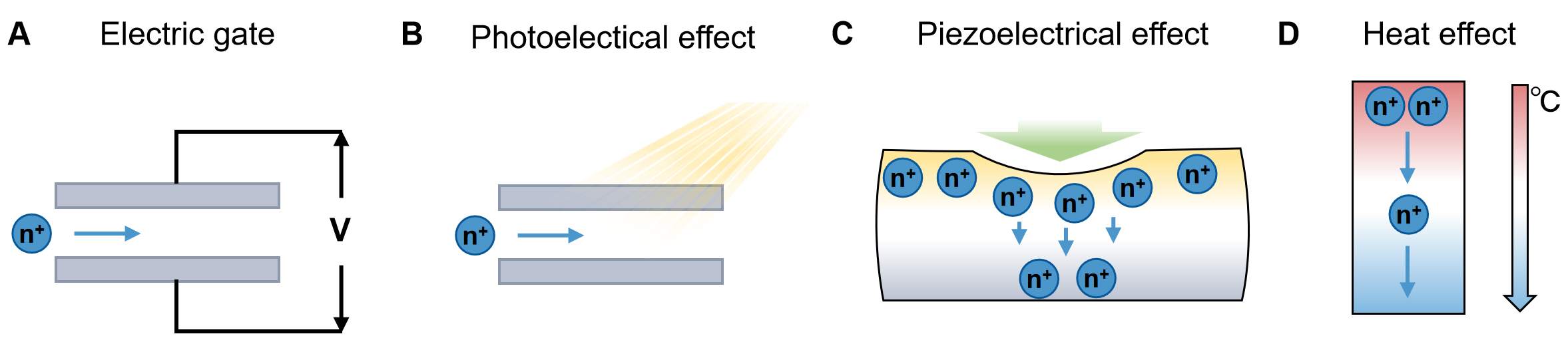

Physical fields provide a powerful and dynamic approach for actively regulating ion dynamics in iontronic systems. By applying external stimuli, such as electric, optical, thermal, piezoelectric, or triboelectric fields, it is possible to control ion transport, selectivity, solvation states, and interfacial adsorption with high efficiency[84,85]. While most studies to date have focused on single-ion modulation, the regulation of multi-ion dynamics under external fields remains largely unexplored. Given that multiple ionic species commonly coexist and interact in electrochemical, energy, and biological systems, understanding and controlling their competitive or cooperative transport under diverse physical fields is critical for the development of next-generation iontronic power devices.

Among physical stimuli, electric fields represent the most direct and widely employed approach for controlling ion transport[86, 87]. Steady or alternating electric potentials can induce directional ion migration and reconfigure interfacial charge distributions via the electric gate effect [Figure 7A]. Direct current (DC) fields predominantly affect ion mobility, whereas alternating current (AC) or pulsed fields can selectively modulate ions with distinct channel properties by adjusting frequency and amplitude[88-90]. However, in multi-ion systems, the electrical signals of different ions are very small due to their subtle Coulomb differences[65], limiting selectivity. A recent study has shown a cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics to achieve diverse electronic-to-multi-ionic signal transmission[86]. The cascade-heterogated property determined the transfer free energy barriers experienced by ions and ionic hydration-dehydration states under an electric potential field, fundamentally enhancing the distinction of cross-interface transmission between different ions by several orders of magnitude.

Figure 7. Physical strategies to modulate ionic dynamics. Schematics of the ion dynamics modulation by (A) electric gate; (B) Photoelectrical effect; (C) Piezoelectrical effect; (D) Heat effect.

Optical fields provide another versatile and non-contact means of ionic regulation. Light-induced energy input can modulate the local chemical and electrostatic environment through photoelectronic effects [Figure 7B]. For instance, an artificial light-driven ion pump was fabricated by carbon nitride nanotube and AAO for photoelectric energy conversion[91]. The surface charge of the carbon nitride is enhanced under illumination, resulting in selective regulation of ions and generating ionic energy. To realize multi-ion transport, a mesoporous carbon-titania/AAO is constructed with dual-functional cation selectivity and photo response[92]. It can achieve bidirectionally adjustable osmotic power and cation/anion transport by alternating the configurations of concentration gradients.

Moreover, mechanical and piezoelectric fields offer a direct coupling between mechanical deformation and ionic motion [Figure 7C]. Piezoelectric materials generate localized electric potentials under external stress, which can guide ion transport along preferential directions[93,94]. Simultaneously, mechanical deformation can modify nanochannel geometry and porosity, regulating ionic flux[95]. Although mechanical stress generally affects all ions similarly, spatial strain gradients or dynamic deformation can be designed to selectively modulate specific ion species through local variations in binding energy or diffusion barriers. Thermal fields influence ion transport via thermos-diffusion (Soret effect, Figure 7D)[96,97]. Temperature gradients can induce directional ion migration and modify interfacial kinetics, while elevated temperatures reduce solvation barriers and enhance ion mobility. Although intrinsic Soret coefficient differences among ions are typically small, these effects can be amplified using thermos-responsive ligands, phase-change materials, or pulsed photothermal heating to achieve selective, temperature-gated ion migration[97-99].

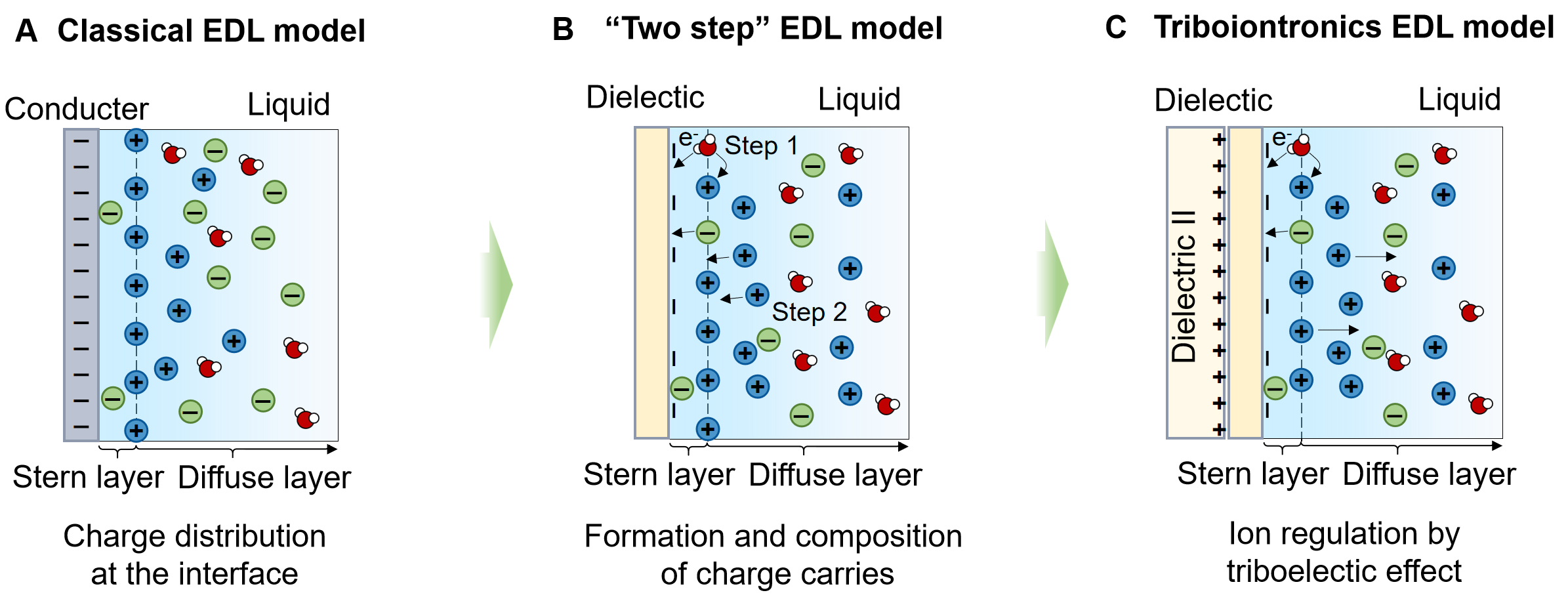

Notably, the triboiontronics effect provides a self-sustained approach to generating transient potential gradients through periodic contact and separation of materials [Figure 8]. The resulting electrostatic fields drive ion migration without the need for continuous external bias. By engineering the surface chemistry, polarity, and dielectric constant of frictional materials, it is possible to achieve selective migration of ions, offering a promising low-power mechanism for dynamic ion regulation. This progress is underpinned by the advancement of EDL models. While classical EDL theories successfully describe interfacial charge behavior at conduct-liquid interfaces and allow electrochemical tuning [Figure 8A], they fall short in capturing the complex charge dynamics at dielectric interfaces. To address this limitation, Wang et al. proposed a two-step EDL model in 2019, representing a key conceptual breakthrough[100] [Figure 8B]. In this model, thermal fluctuations and pressure-driven collisions between water molecules and ions promote electron cloud overlap at the dielectric surface, enabling interfacial electron transfer and forming a compact inner Helmholtz plane (IHP). Subsequently, oppositely charged ions migrate toward the surface to establish the outer Helmholtz plane (OHP), together constituting the Stern layer, with a diffuse layer extending into the bulk solution. This framework provided deeper insight into interfacial charge transfer mechanisms at dielectric interfaces. The triboiontronics EDL model was later introduced to real-time and reversible modulate EDL by utilizing triboelectric-induced polarization[101,102] [Figure 8C]. Through contact electrification (CE), the ionic charge density within the nanoconfined diffuse layer is regulated by CE-induced charges, enabling the realization of a DC triboiontronic nanogenerator (DC-TING) with an ultra-high peak power density of 126.40 W·m-2[101]. Such a strategy can also enable highly portable, interference-resistant underwater transmission systems by multi-type ions with minimal energy consumption, effectively addressing challenges of acoustic multipath interference, environmental noise, and severe signal attenuation.

Figure 8. Schematics of the EDL evaluation and triboiontronics effect. (A) Classical EDL model; (B) Two-step EDL model; (C) Triboiontronics effect. EDL: Electric double-layer.

Overall, physical-field-based strategies provide multi-dimensional, reversible, and real-time control over ionic dynamics. Compared with static structural or chemical modulation, field-based approaches offer superior spatial and temporal tunability, as well as non-invasive programmability. Nevertheless, achieving precise control in multi-ion systems remains challenging. Different physical fields often couple multiple processes, such as local heating, charge redistribution, and fluid motion, which can interfere with selective ion regulation. Furthermore, Coulombic interactions, electrostatic shielding, and cooperative ion migration add complexity to the system’s dynamic response. Future research should therefore emphasize synergistic multi-field coupling, such as photoelectric or piezo-thermal effects, alongside field-material co-design and multi-scale modeling integrated with in situ characterization to uncover the intrinsic mechanisms of multi-ion transport under external stimuli. By combining field modulation with advanced material engineering and spatial or frequency-resolved control, programmable, selective, and adaptive regulation of multi-ion dynamics can be achieved. Such advances will not only improve the efficiency and functionality of iontronic power sources but also enable intelligent, energy-adaptive iontronic systems for next-generation applications in energy, biointerfaces, and information processing.

CHALLENGES AND PERSPECTIVES FOR MODULATING MULTI-ION DYNAMICS

Achieving effective modulation of multi-ion dynamics is essential for advancing iontronic power generation and information processing; however, several fundamental and practical challenges remain unresolved. A key difficulty lies in developing general and straightforward methods for distinguishing among different ion species, as the electrical responses of various ions often differ only subtly, making selective recognition and separation highly challenging[65,103]. Moreover, in realistic environments, multiple ions coexist and interact through competition for transport channels, solvent molecules, or interfacial binding sites. Such interactions can induce nonlinear, collective behaviors, such as ionic polarization and Coulomb blockade, particularly within nanoconfined systems[31,60]. Establishing predictive models and experimental tools capable of capturing these effects is therefore essential for rational multi-ion transport design. In nanofluidic channels and membrane architectures, enhancing ionic selectivity typically compromises permeability[15,72], as spatial confinement and strong electrostatic interactions restrict overall ion flux, thereby limiting both energy conversion efficiency and device scalability. Creating structures that simultaneously discriminate between ions and sustain high transport rates remains a formidable challenge.

From the point of field modulation, although external fields provide real-time and reversible control over ion migration[84,85], establishing a quantitative correlation between field parameters and multi-ion transport behavior is still lacking. Because external stimuli affect ion motion through multiple coupled mechanisms, such as variations in field intensity, frequency, or wavelength, current studies fall short of providing a precise and predictive framework. Future efforts should therefore focus on constructing comprehensive field-ion dynamics mapping models, integrating theoretical simulations with in situ characterization to enable deterministic, programmable control over multi-ion transport.

In addition, a series of noncovalent recognition effects could be used for distinguishing different ion species through noncovalent interactions, including π-π interactions, ion-dipole and dipole-dipole interactions, hydration and steric interactions[104]. Based on this effect, the field of anion recognition and sensing has become one of the most important areas of supramolecular chemistry due to the important role that anions play in numerous biological and environmental processes[105].

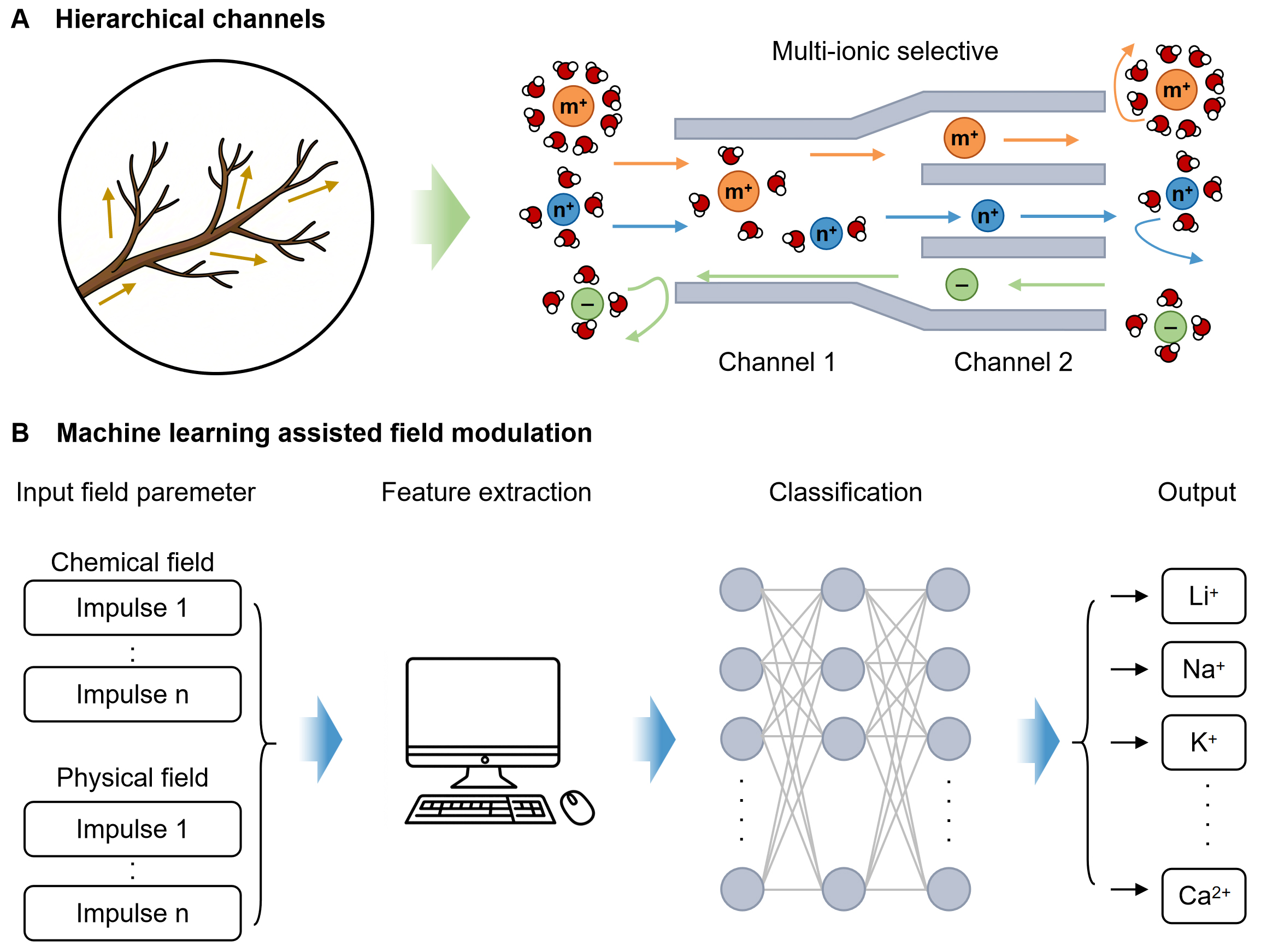

Overall, future advances in multi-ion dynamics modulation are likely to hinge on the synergistic integration of identification technologies, multiscale modeling, and high-resolution field control. For instance, hierarchical channel architectures can be engineered to achieve multistage ionic sieving within confined environments [Figure 9A]. In such systems, primary channels permit high-flux cation transport, while secondary subchannels provide refined discrimination among specific ionic species. This multilevel selection mechanism effectively overcomes the long-standing trade-off between permeability and selectivity in ion-selective membranes, enabling both efficient ion transport and precise ionic recognition. Hierarchically regulated ion migration may also promote cooperative transport behaviors in multi-ion systems, thereby advancing the development of next-generation iontronic interfaces. In parallel, ML-assisted external field modulation represents a powerful avenue for intelligent regulation of multi-ion dynamics [Figure 9B]. By establishing comprehensive databases correlating ion-specific characteristics with field parameters, ML can identify and classify subtle ionic signals and map them to optimized external stimuli. Such data-driven feedback control would enable real-time, adaptive, and programmable adjustment of field conditions, thereby enhancing ionic selectivity and transport efficiency for next-generation self-adaptive iontronic power and logic systems.

Figure 9. Potential multi-ion modulation strategies. (A) Schematic of the hierarchical channel design; (B) Schematic of the ML-assisted field modulation. ML: Machine-learning.

Finally, to realize the practical application of iontronics, it is important to note that the ion transport and response are generally slower than electronic conduction in bulk systems. In contrast, in biological systems, ionic signal transmission relies on rapid interfacial polarization and local electric field redistribution rather than long-range ion diffusion, enabling fast and efficient transport, as exemplified by action potential transmission. To overcome the intrinsic speed limitations of ion transport in artificial systems, nanoconfined channels can be engineered to suppress disordered diffusion and promote directional ion transport, thereby significantly accelerating ionic responses. In parallel, ionic-electronic coupling allows slow yet information-rich ionic signals to be seamlessly integrated with fast electronic signal transmission at the interfaces. Collectively, these strategies transform the apparent speed disadvantage of ionic systems into a complementary advantage, positioning iontronics as a promising platform for efficient energy-information coupling beyond conventional electronics.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

The modulation of multi-ion dynamics represents a critical frontier in advancing iontronic power sources and related technologies. Recent advances in materials design, interface engineering, and external-field modulation have enabled selective control of multi-type ions, cooperative flux regulation, and multi-ionic-electronic coupling at interfaces. These strategies collectively offer promising routes to enhance energy conversion efficiency, operational stability, and environmental adaptability in complex ionic systems. However, significant challenges still persist, including material stability, complex multi-ion interactions, and limited control of external fields, which hinder the practical application of multi-ionic iontronics.

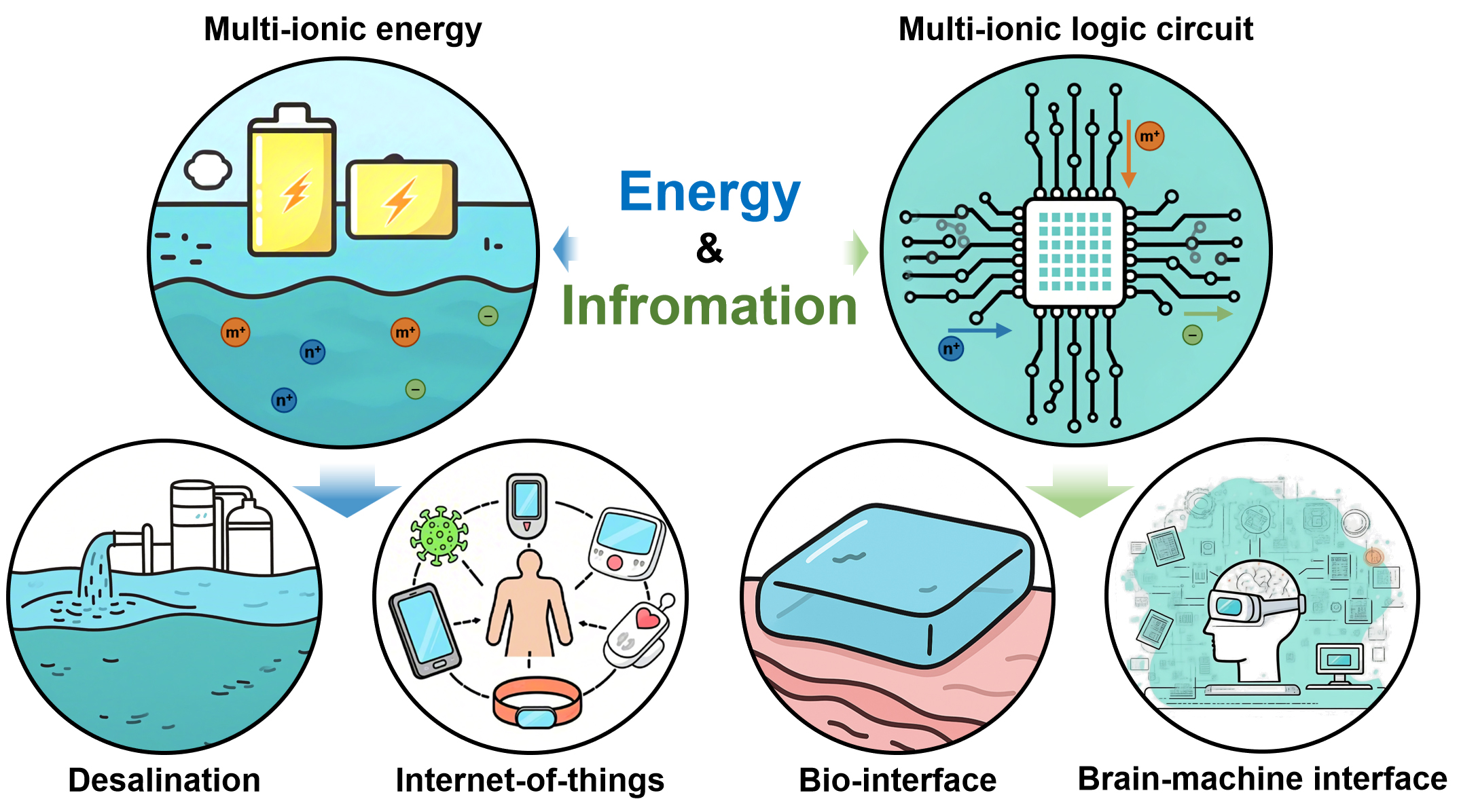

Looking ahead, the ability to finely manipulate multi-ion dynamics is expected to drive paradigm shifts across diverse fields ranging from energy to information systems, as conceptually illustrated in Figure 10. In sustainable energy harvesting, future iontronic platforms may exploit tailored multi-ion transport pathways to enhance ionic energy conversion efficiency, particularly by leveraging high-valence ions that can carry greater charge per carrier, thereby reshaping strategies for energy generation and storage. In seawater desalination, advanced multi-ionic regulation could enable simultaneous high-throughput transport and selective ion separation, overcoming the long-standing trade-off between permeability and selectivity. Likewise, in bio-integrated interfaces and brain-machine communication, precise multi-ionic modulation may serve as a general and biocompatible signaling language, enabling information encoding through ion-specific attributes. This is because the size, valence and charge state of different ions have the potential to be encoded to achieve multi-mode information storage. Collectively, these envisioned advances highlight the potential of multi-ion-enabled iontronics to evolve toward intelligent, adaptive, and sustainable technologies, in which energy and information are co-processed and interconverted through ionic dynamics.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of Prof. Wei’s group at the Beijing Institute of Nanoenergy and Nanosystems (Beijing, China) for their insightful discussions.

Authors’ contributions

Contributed to the discussion, analysis, and writing of the manuscript: Peng, P.; Wang, Z.; Wei, D.

Availability of data and materials

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (grant number 22479016).

Conflicts of interest

Wei, D. is Editor-in-Chief of the journal Iontronics. Wang, Z. is Honorary Editor-in-Chief of the journal. Wei, D. and Wang, Z. were not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. Peng, P. declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

2. Burgoyne, R. D. Neuronal calcium sensor proteins: generating diversity in neuronal Ca2+ signalling. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 182-93.

3. Xiao, K.; Jiang, L.; Antonietti, M. Ion transport in nanofluidic devices for energy Harvesting. Joule 2019, 3, 2364-80.

4. Zhang, Z.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Nanofluidics for osmotic energy conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 622-39.

5. Feiner, R.; Dvir, T. Tissue-electronics interfaces: from implantable devices to engineered tissues. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 3, 17076.

6. Zhao, S.; Tseng, P.; Grasman, J.; et al. Programmable hydrogel ionic circuits for biologically matched electronic interfaces. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1800598.

7. Devine, M. J.; Kittler, J. T. Mitochondria at the neuronal presynapse in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 63-80.

8. MITCHELL, P. Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature 1961, 191, 144-8.

9. Sun, Z.; Guo, S. S.; Fässler, R. Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. J. Cell. Biol. 2016, 215, 445-56.

10. Amoli, V.; Kim, J. S.; Jee, E.; et al. A bioinspired hydrogen bond-triggered ultrasensitive ionic mechanoreceptor skin. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4019.

12. Nassi, J. J.; Callaway, E. M. Parallel processing strategies of the primate visual system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 360-72.

13. Vermaas, D. A.; Veerman, J.; Saakes, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Influence of multivalent ions on renewable energy generation in reverse electrodialysis. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1434-45.

14. Huang, L.; Bao, D.; Jiang, Y.; Regenauer-Lieb, K.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S. Z. The utilization of ions in seawater for electrocatalysis. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf461.

15. Qian, H.; Peng, P.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. L.; Wei, D. Balancing selectivity and permeability in nanofluidic membranes for osmotic power generation. Prog. Energy. 2025, 7, 042001.

17. Emmerich, T.; Ronceray, N.; Agrawal, K. V.; et al. Nanofluidics. Nat. Rev. Methods. Primers. 2024, 4, 69.

18. Wan, C.; Xiao, K.; Angelin, A.; Antonietti, M.; Chen, X. The rise of bioinspired ionotronics. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2019, 1, 1900073.

19. Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y. Nanoconfined ionic liquids. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 6755-833.

20. Lee, J.; Lu, W. D. On-demand reconfiguration of nanomaterials: when electronics meets ionics. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30.

21. Park, J. M.; Lim, S.; Sun, J. Y. Materials development in stretchable iontronics. Soft. Matter. 2022, 18, 6487-510.

22. Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Dai, J.; Xiao, K. Nanoionics from biological to artificial systems: an alternative beyond nanoelectronics. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2022, 9, e2200534.

23. Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, S.; et al. Two-dimensional materials for next-generation computing technologies. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 545-57.

24. Sparreboom, W.; van den Berg, A.; Eijkel, J. C. Principles and applications of nanofluidic transport. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 713-20.

25. Wang, X.; Salari, M.; Jiang, D.; et al. Electrode material-ionic liquid coupling for electrochemical energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 787-808.

26. Choi, C.; Ashby, D. S.; Butts, D. M.; et al. Achieving high energy density and high power density with pseudocapacitive materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 5, 5-19.

27. Zhou, T.; Liu, T.; Huang, S.; et al. The influence of divalent ions on the osmotic energy conversion performance of 2D cation exchange membrane in reverse electrodialysis process. Desalination 2024, 591, 118036.

28. Avci, A. H.; Sarkar, P.; Tufa, R. A.; et al. Effect of Mg2+ ions on energy generation by reverse electrodialysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 520, 499-506.

29. Esfandiar, A.; Radha, B.; Wang, F. C.; et al. Size effect in ion transport through angstrom-scale slits. Science 2017, 358, 511-3.

30. Shao, J. J.; Raidongia, K.; Koltonow, A. R.; Huang, J. Self-assembled two-dimensional nanofluidic proton channels with high thermal stability. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7602.

31. Shen, J.; Liu, G.; Han, Y.; Jin, W. Artificial channels for confined mass transport at the sub-nanometre scale. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 294-312.

32. Wang, M.; Hou, Y.; Yu, L.; Hou, X. Anomalies of ionic/molecular transport in nano and sub-nano confinement. Nano. Lett. 2020, 20, 6937-46.

33. Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Liu, F.; et al. Ultrafast ion sieving using nanoporous polymeric membranes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 569.

34. Lei, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Z. High-performance solid-state proton gating membranes based on two-dimensional hydrogen-bonded organic framework composites. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 754.

35. Guo, R.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Interlayer confinement toward short hydrogen bond network construction for fast hydroxide transport. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr5374.

36. Lu, D.; Li, R.; Rahman, M. M.; et al. Ligand-channel-enabled ultrafast Li-ion conduction. Nature 2024, 627, 101-7.

37. Dong, Z.; Chen, Q.; Ma, X.; et al. The role of co-ion transport in selectrodialysis for mono/divalent anion separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 736, 124660.

38. Guo, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Deciphering co-ion and counterion transport in polyamide desalination membranes reveals ion selectivity mechanisms. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadu8302.

39. Tielrooij, K. J.; Garcia-Araez, N.; Bonn, M.; Bakker, H. J. Cooperativity in ion hydration. Science 2010, 328, 1006-9.

40. Yan, J.; Jiang, C.; Zeng, X.; et al. Synthesis of deuterated acids and bases using bipolar membranes. Nature 2025, 643, 961-6.

41. Baskin, A.; Prendergast, D. Ion solvation engineering: how to manipulate the multiplicity of the coordination environment of multivalent ions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 9336-43.

42. Wang, X.; Toroz, D.; Kim, S.; Clegg, S. L.; Park, G. S.; Di Tommaso, D. Density functional theory based molecular dynamics study of solution composition effects on the solvation shell of metal ions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 16301-13.

43. Schienbein, P.; Schwaab, G.; Forbert, H.; Havenith, M.; Marx, D. Correlations in the solute-solvent dynamics reach beyond the first hydration shell of ions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 2373-80.

44. Xu, T.; Cui, Z.; Yao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, L. Multi-ion coordinated water network in dilute acid electrolytes for ultralow-temperature (≤ -80 °C) proton energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202510830.

45. Yang, F.; Peng, P.; Yan, Z.; et al. Vertical iontronic energy storage based on osmotic effects and electrode redox reactions. Nat. Energy. 2024, 9, 263-71.

46. Zhu, Y. H.; Cui, Y. F.; Xie, Z. L.; Zhuang, Z. B.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X. B. Decoupled aqueous batteries using pH-decoupling electrolytes. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 505-17.

47. Bockris, J. O. M.; Reddy, A. K.; Gamboa-Aldeco, M. Modern Electrochemistry 2A; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002.

48. Huang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Yang, C.; et al. Interface-mediated hygroelectric generator with an output voltage approaching 1.5 volts. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4166.

49. Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yan, X. Ion regulation of ionic liquid electrolytes for supercapacitors. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 2859-82.

50. Zhu, Y. H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. B. Hydronium ion batteries: a sustainable energy storage solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 6378-80.

51. Li, M.; Lu, J.; Ji, X.; et al. Design strategies for nonaqueous multivalent-ion and monovalent-ion battery anodes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 276-94.

52. Eftekhari, A.; Jian, Z.; Ji, X. Potassium secondary batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017, 9, 4404-19.

53. Pohlmann, S.; Kühnel, R. S.; Centeno, T. A.; Balducci, A. The influence of anion-cation combinations on the physicochemical properties of advanced electrolytes for supercapacitors and the capacitance of activated carbons. ChemElectroChem 2014, 1, 1301-11.

54. Surendralal, S.; Todorova, M.; Neugebauer, J. Impact of water coadsorption on the electrode potential of H-Pt(1 1 1)-liquid water interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 166802.

55. Li, P.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Y.; et al. Hydrogen bond network connectivity in the electric double layer dominates the kinetic pH effect in hydrogen electrocatalysis on Pt. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 900-11.

56. Rohaizad, N.; Mayorga-Martinez, C. C.; Fojtů, M.; Latiff, N. M.; Pumera, M. Two-dimensional materials in biomedical, biosensing and sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 619-57.

57. Peng, P.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Wei, D. Integratable paper-based iontronic power source for all-in-one disposable electronics. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2302360.

58. Bocquet, L.; Charlaix, E. Nanofluidics, from bulk to interfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1073-95.

59. Bard, A. J.; Faulkner, L. R.; White, H. S. Electrochemical methods: fundamentals and applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2001. https://eva.fcien.udelar.edu.uy/pluginfile.php/144317/mod_resource/content/3/Electrochemical%20Methods%20Bard%20Faulkner%20Cap1-4.pdf (accessed 2026-1-20).

61. Zhong, J.; Alibakhshi, M. A.; Xie, Q.; et al. Exploring anomalous fluid behavior at the nanoscale: direct visualization and quantification via nanofluidic devices. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 347-57.

62. Chen, L.; Shi, G.; Shen, J.; et al. Ion sieving in graphene oxide membranes via cationic control of interlayer spacing. Nature 2017, 550, 380-3.

63. Hu, Y.; Wu, M.; Chi, F.; et al. Ultralow-resistance electrochemical capacitor for integrable line filtering. Nature 2023, 624, 74-9.

64. Wu, M.; Chi, F.; Geng, H.; et al. Arbitrary waveform AC line filtering applicable to hundreds of volts based on aqueous electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2855.

65. Feng, J.; Liu, K.; Graf, M.; et al. Observation of ionic Coulomb blockade in nanopores. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 850-5.

66. Tian, Y.; Song, Y.; Xia, Y.; et al. Nanoscale one-dimensional close packing of interfacial alkali ions driven by water-mediated attraction. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 479-84.

67. Kondrat, S.; Wu, P.; Qiao, R.; Kornyshev, A. A. Accelerating charging dynamics in subnanometre pores. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 387-93.

68. Kim, S.; Choi, S.; Lee, H. G.; et al. Neuromorphic van der Waals crystals for substantial energy generation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 47.

70. Sangwan, V. K.; Hersam, M. C. Neuromorphic nanoelectronic materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 517-28.

71. Xiao, K.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. A tunable ionic diode based on a biomimetic structure-tailorable nanochannel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 8168-72.

72. Qian, H.; Fan, H.; Peng, P.; et al. Biomimetic Janus MXene membrane with bidirectional ion permselectivity for enhanced osmotic effects and iontronic logic control. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx1184.

73. Li, L.; Yang, Y.; He, N.; et al. Dual-interfacial gating unlocks bidirectional ionic flux for high-efficiency hydrovoltaic energy harvesting. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 8209-19.

74. Simons, R. Strong electric field effects on proton transfer between membrane-bound amines and water. Nature 1979, 280, 824-6.

75. Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Epsztein, R.; et al. Intrapore energy barriers govern ion transport and selectivity of desalination membranes. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6.

76. Hong, X.; Ma, X.; He, L.; et al. Regulating lattice-water-adsorbed ions to optimize intercalation potential in 3D Prussian blue based multi-ion microbattery. Small 2021, 17, e2007791.

77. Zhen, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, S.; et al. Efficient ion separation in multi-ion coexisting scenarios via two-dimensional metal-organic framework membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163496.

78. Xu, R.; Yu, H.; Ren, J.; et al. Regulate ion transport in subnanochannel membranes by ion-pairing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 17144-51.

79. Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Xiao, S.; et al. Ultrafast diameter-dependent water evaporation from nanopores. ACS. Nano. 2019, 13, 3363-72.

80. Peng, P.; Shen, P.; Qian, H.; et al. Photochemical iontronics with multitype ionic signal transmission at single pixel for self-driven color and tridimensional vision. Device 2025, 3, 100574.

81. Zhang, Y.; Wu, P.; Chen, C.; et al. Electrochemical power sources enabled by multi-ion carriers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 9685-806.

82. Jin, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; et al. Entropy driving “Quasi‐Zero Strain” stepwise multicationic redox chemistry toward a high-performance NASICON-cathode for Na-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2422101.

83. Wang, S.; Jiao, S.; Tian, D.; et al. A novel ultrafast rechargeable multi-ions battery. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29.

84. Peng, P.; Qian, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wei, D. Bioinspired ionic control for energy and information flow. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2024, 15, 198-221.

85. Liu, P.; Kong, X. Y.; Jiang, L.; Wen, L. Ion transport in nanofluidics under external fields. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2972-3001.

86. Chen, W.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics for electronic-to-multi-ionic signal transmission. Science 2023, 382, 559-65.

87. Zhao, Y.; Yan, X.; Xia, L.; et al. Enabling an ultraefficient lithium-selective construction through electric field-assisted ion control. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv6646.

88. Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Kang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Simon, G. P.; Wang, H. Voltage-gated ion transport in two-dimensional sub-1 nm nanofluidic channels. ACS. Nano. 2019, 13, 11793-9.

89. Liu, W.; Mei, T.; Cao, Z.; et al. Bioinspired carbon nanotube-based nanofluidic ionic transistor with ultrahigh switching capabilities for logic circuits. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj7867.

90. He, Z.; Zhou, J.; Lu, X.; Corry, B. Bioinspired graphene nanopores with voltage-tunable ion selectivity for Na+ and K+. ACS. Nano. 2013, 7, 10148-57.

91. Xiao, K.; Chen, L.; Chen, R.; et al. Artificial light-driven ion pump for photoelectric energy conversion. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 74.

92. Zhou, S.; Zhang, X.; Xie, L.; et al. Dual-functional super-assembled mesoporous carbon-titania/AAO hetero-channels for bidirectionally photo-regulated ion transport. Small 2023, 19, e2301038.

93. Jin, M. L.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.; et al. An ultrasensitive, visco-poroelastic artificial mechanotransducer skin inspired by Piezo2 protein in mammalian Merkel cells. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605973.

94. Yang, R.; Dutta, A.; Li, B.; et al. Iontronic pressure sensor with high sensitivity over ultra-broad linear range enabled by laser-induced gradient micro-pyramids. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2907.

95. Xu, T.; Jin, L.; Ao, Y.; et al. All-polymer piezo-ionic-electric electronics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10876.

96. Han, C. G.; Qian, X.; Li, Q.; et al. Giant thermopower of ionic gelatin near room temperature. Science 2020, 368, 1091-8.

97. Zhao, D.; Fabiano, S.; Berggren, M.; Crispin, X. Ionic thermoelectric gating organic transistors. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14214.

98. Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Song, Z.; et al. Efficient solar energy conversion via bionic sunlight-driven ion transport boosted by synergistic photo-electric/thermal effects. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 3146-57.

99. Li, W.; Li, X.; He, J.; Zhai, J.; Fan, X. Solar-enhanced blue energy conversion via photo-electric/thermal in GO/MoS2/CNC nanofluidic membranes. Small 2025, 21, e06667.

100. Lin, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z. L. Contact electrification at the liquid-solid interface. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5209-32.

101. Li, X.; Li, S.; Guo, X.; Shao, J.; Wang, Z. L.; Wei, D. Triboiontronics for efficient energy and information flow. Matter 2023, 6, 3912-26.

102. Zhang, L.; Wang, D. Triboiontronics based on dynamic electric double layer regulation. Matter 2023, 6, 3698-9.

103. Kavokine, N.; Marbach, S.; Siria, A.; Bocquet, L. Ionic coulomb blockade as a fractional Wien effect. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 573-8.

104. Molina, P.; Zapata, F.; Caballero, A. Anion recognition strategies based on combined noncovalent interactions. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9907-72.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].