fig7

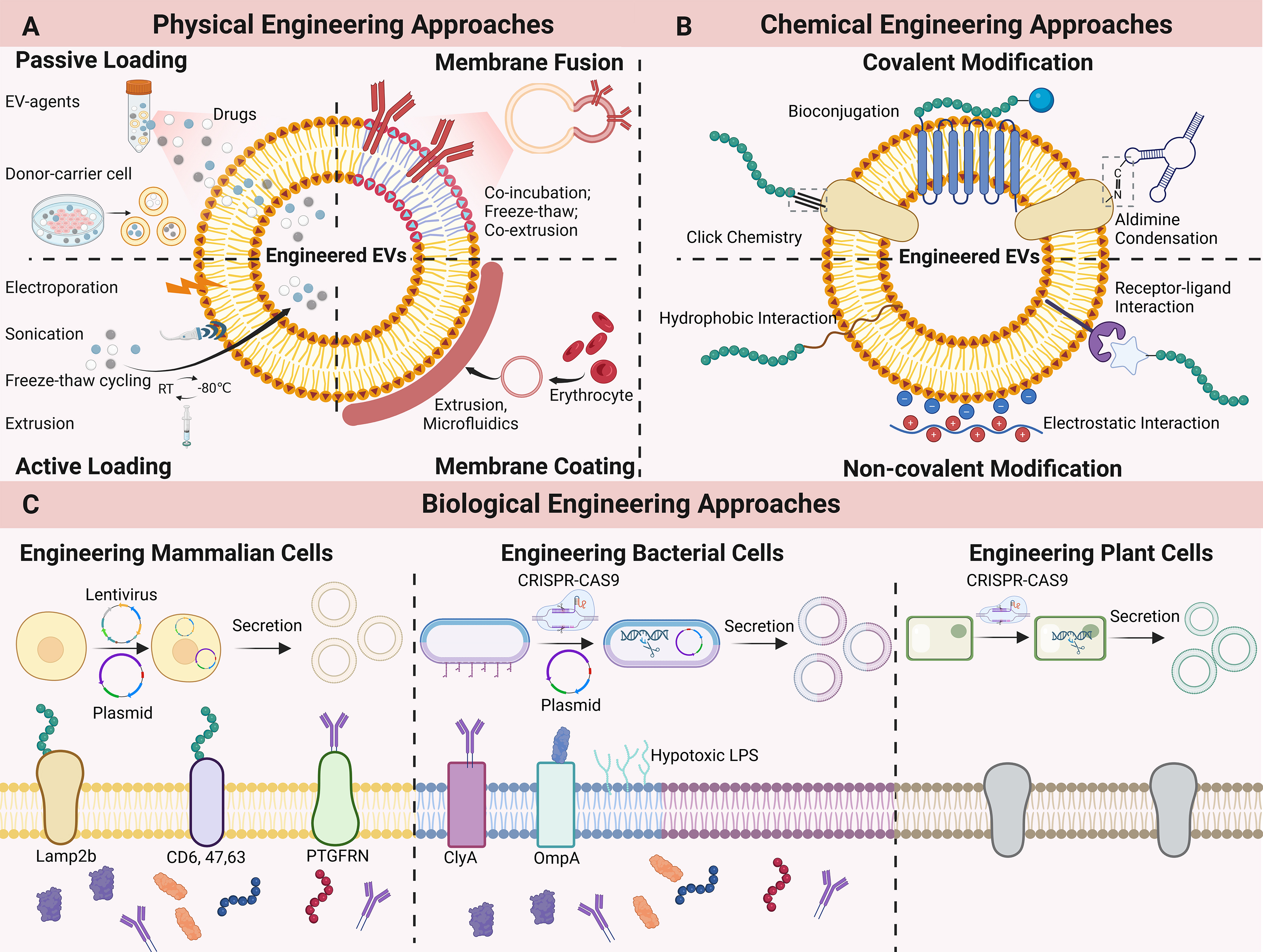

Figure 7. Representative Methods of EV Engineering. (A) Physical engineering of EVs. Physical methods enable therapeutic agent loading and membrane functionalization. Passive loading is achieved through co-incubation, while active loading employs techniques such as electroporation, sonication, extrusion, and freeze-thaw cycling. Membrane modification can be accomplished via membrane fusion (utilizing co-incubation, freeze-thaw, or extrusion) or membrane coating (via extrusion or microfluidics); (B) Chemical engineering of EVs. Chemical modification strategies are divided into covalent and non-covalent approaches. Covalent methods include click chemistry, bioconjugation, and aldehyde-amine condensation. Non-covalent modifications leverage hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions, or receptor-ligand binding; (C) Biological engineering of EVs. In mammalian cells, plasmid transfection or lentiviral infection enables the expression of fusion proteins, wherein targeting peptides or proteins are displayed on the EV membrane. Similarly, bacterial cells can be engineered with plasmids to overexpress surface fusion proteins. Additionally, the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be utilized to knock out genes associated with toxicity or immunogenicity, or to modify plant-derived EVs. EVs: Extracellular vesicles; RT: room temperature; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; CRISPR-CAS9: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-CRISPR associated protein 9; Lamp2b: lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2b; PTGFRN: prostaglandin F2 receptor negative regulator; ClyA: cytolysin A; OmpA: outer membrane protein A.