Sustainable clinical translation: development of implantable energy systems

Abstract

Advances in the Internet of Things and artificial intelligence have accelerated the clinical adoption of implantable electronic medical devices, expanding their applications in brain-computer interfaces, chronic disease management, and post-operative rehabilitation. However, the growing disparity between finite global energy resources and escalating clinical demands necessitates urgent breakthroughs in implantable energy systems. To address this challenge, implantable energy systems are evolving towards sustainability, miniaturisation, system-level integration and flexibility for better application in the human body. This review synthesizes the key design principles and requirements for an implantable energy system driven by clinical demands, then highlights recent progress in three key categories: energy storage systems, energy harvesting systems and environmental energy transfer systems. Notable advancements include biocompatible materials and enhanced integration strategies. Emerging energy systems, such as biofuel cells and nanogenerators, are also analyzed. Furthermore, we discuss their translational challenges and future directions, such as long-term biocompatibility, holistic energy solutions, closed-loop surveillance, and intelligent network architectures. Overall, this review bridges medical energy innovation with environmental sustainability, providing insights into sustainable closed-loop networks that integrate energy, medicine, and industry.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

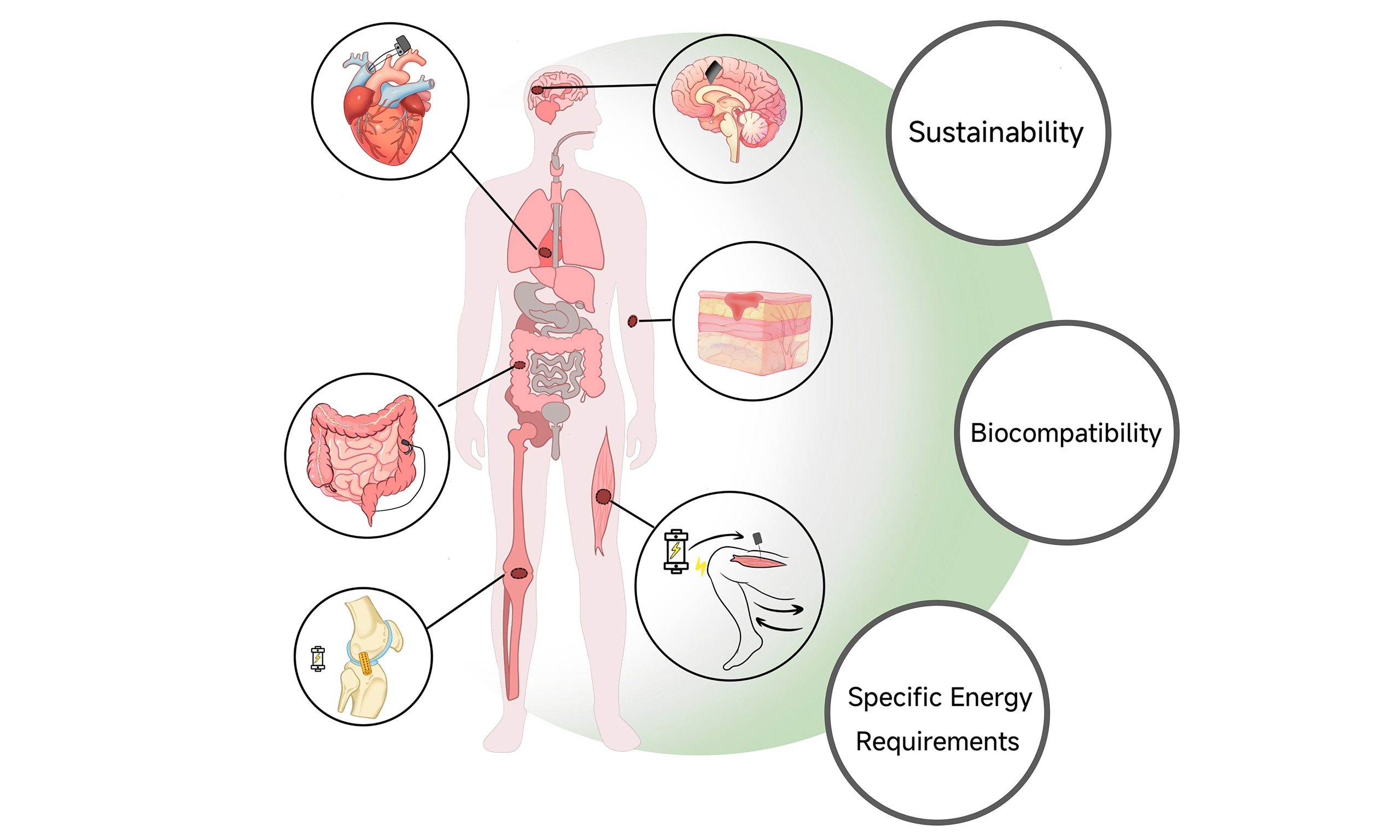

Implantable electronic medical devices have dramatically transformed clinical practice by offering continuous therapeutic support, brain-computer interfaces and real-time monitoring of physiological conditions[1-4]. However, the pursuit of enhanced intelligence and precision in therapeutic or diagnostic devices inherently escalates their power consumption, posing a critical challenge for energy-efficient healthcare technologies. As the dominant source of implantable power today, conventional lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are faced with three major limitations: (1) Poor biocompatibility: Rigid components mechanically mismatch with human tissues and torganic electrolyte leakage may trigger oxidative tissue necrosis; (2) Triple trade-off among size, energy density, and safety: High energy density requires thick electrodes or reactive materials, increasing risks of thermal runaway; (3) Ecological unsustainability: limited global lithium reserves and < 1% recycling efficiency for batteries exacerbate long-term ecotoxicity[5-7]. For example, clinical evidence shows that implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (e.g., Medtronic, Biotronik) have a variable median battery lifespan of 10.8 years, leading to frequent replacement with invasive risks such as infection[8]. Similarly, deep brain stimulators face challenges in reducing battery size and increasing energy output. These limitations limit the implantation depth of the device[9].

Driven by these limitations, implantable energy systems are evolving towards sustainability, miniaturisation, system-level integration and flexibility. Additionally, research into biodegradable materials, such as magnesium alloys, poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), Poly Lactic Acid (PLA) and silk fibroin, is opening up new possibilities for temporary, resorbable energy systems that eliminate the need for surgical extraction after their functional period[10,11]. These materials and technologies could revolutionize post-operative monitoring while minimizing medical waste generation through degradable components. These advances underscore the necessity of interdisciplinary efforts, in which rigorous preclinical testing, iterative design optimization, and close collaboration among clinicians, materials scientists, and regulatory bodies collectively drive the translation of laboratory efforts into clinical applications.

Emerging implantable energy systems can be broadly classified into three categories: energy storage systems, energy harvesting systems and environmental energy transfer systems. Energy storage systems encompass next-generation batteries and supercapacitors, which feature stable discharge profiles but necessitate periodic recharging or replacement[12]. Energy harvesting systems encompass biofuel cells (BFCs) and nanogenerators, which harness endogenous metabolic energy from biological processes[13,14]. Concurrently, environmental energy transfer systems leverage radio-frequency radiation, ultrasound, photovoltaic conversion, and magnetoelectric induction technologies to transfer ambient energy[15-18]. However, these systems face the challenge of intermittent power supply due to environmental variability and limited power output, necessitating hybrid designs that integrate multiple energy modalities for continuous operation. Such hybridization aligns with circular economy principles by enabling energy recycling and minimizing resource depletion. Despite growing clinical demand for sustainable implantable energy systems, comprehensive reviews synthesizing recent innovations in materials and technologies remain scarce. In this review, we bridge this critical knowledge gap by not only elucidating the basic requirements and cutting-edge advancements, but also discussing the development trends and possible challenges.

DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND REQUIREMENTS

Unlike external energy storage devices, implantable energy systems must adapt to the body's constrained space, tissue-specific physiological and mechanical environments, and daily movement dynamics. These principles and requirements, driven by clinical needs and energy conservation, influence both material selection and design approaches for next-generation implantable energy systems.

Sustainability

Sustainability is a critical pillar in the translation of implantable energy systems from bench to bedside. We suggest that assessing the sustainability of different energy systems should focus on the following three dimensions: (1) Manufacturing process: Material preparation and energy system assembly should be cost-effective and easily integrated with implantable medical devices such as sensors; (2) End-of-life management: Biodegradable systems must undergo long-term validation to ensure that degradation products can be safely metabolized by the human body; non-biodegradable systems must establish a comprehensive industrial recycling system to enable proper sorting and processing; (3) Adaptability to human health: Meet miniaturization and flexibility requirements, and operate stably under human body conditions such as temperature and humidity; possess electromagnetic compatibility to avoid interfering with normal physiological systems. For non-degradable energy systems, modifying their physicochemical properties to enhance environmental compatibility and establishing a closed-loop battery recycling system are critical strategies to minimize environmental impact and improve resource utilization efficiency. To mitigate the environmental impact of spent LIBs, innovative recycling methods are emerging as sustainable alternatives to conventional pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes, which suffer from high energy consumption and chemical waste[19]. Moreover, new materials to replace traditional LIBs are being tested. Zinc-based batteries are gaining attention as LIB alternatives because of their abundant reserves (210,000 kt zinc vs. 26,000 kt lithium) and established recycling networks (~30% global supply)[20].

Degradable materials offer an attractive alternative for temporary implants, especially in scenarios where complete absorption of the device is desired post-therapy. Polymer-based composites (e.g., PLGA, PLA) and naturally derived biomolecules (e.g., gelatin, cellulose) are widely investigated for implantable energy systems owing to their cost-effectiveness and controlled degradability[21,22]. The application of these materials not only circumvents secondary surgeries and alleviates patients' pain and economic burdens but also significantly eases waste disposal challenges, fostering synergies across healthcare and sustainability.

Biocompatibility

A key consideration in the design of implantable energy systems is biocompatibility. This requires the implanted material to be biologically inert (non-toxic and non-immunogenic), while simultaneously exhibiting tissue-matched mechanical properties to minimize physical irritation and tissue damage. Upon implantation, the host's multi-stage immune response is triggered by protein adsorption on the foreign material surface, and subsequently mediated through synergistic immune cell interactions[23]. Biocompatibility can be achieved either through surface modification of inherently incompatible materials or by replacing them with highly biocompatible alternatives.

Surface modification strategies can be implemented through three synergistic approaches: (1) physical modulation via micro-nano topological patterning or optimizing surface hydrophilicity and roughness to minimize pro-inflammatory response; (2) chemical modification via covalent grafting of polyethylene glycol or zwitterionic polymers to create an electro-neutral barrier that reduces serum protein adsorption; (3) biological camouflage using cell membrane-derived coatings (e.g., CD47-enriched erythrocyte membranes) to achieve immune-evading[24]. This approach is exemplified by the implantable wireless optoelectronic system described in Kim et al.[25]. The device integrates flexibly encapsulated inorganic micro-light-emitting diodes (μ-LEDs) and phototransistors within a multilayer polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)/SiO2/parylene C structure, achieving long-term biocompatibility and reduced mechanical stress at the tissue-device interface.

At the same time, degradable materials must undergo thorough safety evaluations to ensure that their degradation products do not present systemic risks. PLA, an environmentally friendly material, has been explored as a component in the development of biodegradable batteries. However, some literature suggests that the degradation products of PLA may lead to chronic inflammation through metabolic reprogramming[26,27]. A composite design of the material combined with glycolysis inhibitors or other agents to reduce the pro-inflammatory response may be a safer approach. These evaluations are essential in confirming the long-term biocompatibility of degradable implants.

Specific energy requirements

Implantable energy systems typically require high energy density to achieve miniaturisation, with specific needs varying by clinical application. Recent advances in multifunctional material architectures, including metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and nanomaterial-based hybrid systems, have provided a fundamental basis for increasing the gravimetric and volumetric energy density of next-generation implantable energy systems through the rational design of electrode-electrolyte interfaces and scalable fabrication strategies[28-31]. These systems can be broadly classified into three categories: lifetime power, short-term degradable power, and dynamic response systems[32].

For devices requiring lifetime power such as cardiac pacemakers, the need for high energy density and extended operational lifespan is paramount. State-of-the-art pacemakers typically operate for 10-15 years, with some advanced prototypes aiming to exceed this duration. For short-term applications such as fracture monitoring and post-surgical tissue healing, the energy source must be degradable and synchronized with the healing process[32]. Degradable batteries based on Mg-Zn alloys, for example, exhibit controlled hydrogen evolution and high efficiency, making them promising for biodegradable batteries in medical implants[33]. However, the alignment of their degradation kinetics with tissue repair timelines remains to be validated experimentally.

Dynamic clinical applications, such as brain-machine interfaces and advanced neuro-modulation systems for epilepsy, demand an energy system capable of real-time response to fluctuating neural signals. Hybrid energy solutions that integrate nanogenerators with micro-batteries have demonstrated feasibility in preclinical studies, though long-term stability in vivo remains a challenge[34].

In conclusion, the clinical design principles and core requirements for implantable energy systems demand a multifaceted approach. This includes ensuring sustainability, stable energy supply, biocompatibility and safety validation. Such a comprehensive strategy is crucial to address the evolving challenges of modern medical applications while fostering interdisciplinary collaboration. Collectively, these demands will drive the advancement of next-generation implantable energy systems.

NEXT-GENERATION IMPLANTABLE ENERGY SYSTEMS

The rising energy demand highlights the critical need for sustainable energy supply solutions. The development of implantable energy systems is mainly manifested in three aspects: the refinement of mature lithium-based technologies, the emergence of sustainable alternatives, and the advancement of novel capacitive energy storage methods. These advances are not only transforming traditional fields, such as cardiology, neuroscience, and chronic disease management, but also expanding into emerging domains such as orthopedics, regenerative medicine, and gastrointestinal diagnostics. By combining the reliable performance of established technologies with the potential of emerging innovations, these systems are designed to be safer, more efficient, and better tailored to the specific clinical demands of diverse patient populations. This section offers a comprehensive overview of next-generation implantable energy systems, followed by a critical analysis of emerging systems and preclinical advancements [Table 1].

Implantable energy systems for implantable medical devices: multidimensional assessment and progress

| Implantable energy systems | Advantages | Scenario | Disadvantages | Research progress | Ref. |

| Batteries | High energy density and long-term stability | Devices that require long-term power supply, such as pacemakers and nerve stimulators | Triple trade-off among size, energy density, and safety | 1. Composite electrolyte 2. Multi-scale fabrication strategies 3. Metal-air batteries 4. Degradable batteries | [39-44] |

| Supercapacitors | Long cycle life; High power density | Transient biosignal monitoring devices | 1. Low energy density 2. Low voltage | 1. Biocompatible materials; material modification techniques; encapsulation technology 2. Asymmetric supercapacitors | [51,53,55] |

| Biofuel cells | Convert biologic substrate into electricity, function sustainably without external recharging | 1. Self-powered biosensors (e.g., glucose in diabetes); 2. Low-power therapeutic devices (e.g., insulin pumps) | 1. Limited operational lifetimes (typically months) 2. Enzymatic biofuel cells: Limited output power and poor operational stability 3. Microbial BFCs: rarely been used in humans due to their susceptibility to bacterial infections and exposure to bacterial toxins | 1. Miniature membrane-free biofuel cells 2. Enzymatic biofuel cells: Protein engineering, enzyme immobilization and multi-enzyme systems 3. Abiotic enzyme biofuel cells 4. Microbial biofuel cells: synthetic biology-based microbial engineering, and 3D-printed manufacturing | [60-62,69,72-75] |

| Nanogenerators | Harvest energy continuously from human activities (e.g., heartbeats, breathing, and walking) | 1. PENGs: Optimal for devices harnessing continuous micro-vibrations, such as cardiac pacemakers and peripheral nerve stimulators. 2. TENGs: Optimal for devices requiring high-voltage/high-current outputs (μW to mW level) powered by large-displacement mechanical motions, such as limb movement; 3. TEGs: Wearable devices for smart health monitoring | 1. PENGs: Restricted material diversity; output may attenuate under repetitive mechanical loading 2. TENGs:Highly sensitive to humidity and temperature; output attenuation under repetitive mechanical loading 3. TEGs: The power output exhibits instability | 1. PENGs: Mechanical annealing treatment for piezoelectric performance enhancement in materials. 2. TENGs: Conductive Triboelectric Layers 3. Devices capable of harvesting electricity from other physiological gradients within the human body, such as humidity gradients | [88] [89] [95] |

| Environmental energy transfer systems | Utilizing low-grade energy sources to power devices | Low-power implantable medical devices, such as pacemakers and smart pumps | 1. Magnetoelectric induction energy: Requiring precise alignment between external transmitter and implanted receiver coils; thermal damage risks 2. Radiofrequency energy: Attenuation caused by dielectric relaxation and conductive loss in biological tissues 3. Ultrasound energy: Energy reflection loss may occur at material-tissue interfaces 4. Light energy: Traditional silicon-based semiconductor materials exhibit high hardness and poor flexibility | 1. Magnetoelectric induction energy: Combined with energy storage systems; low-frequency magnetoelectric platform 2. Radiofrequency energy: Superoscillation-driven sub-λ beamforming in Huygens' Box 3. Ultrasound energy: Modifying biocompatible materials; designing flexible encapsulation; configuring adaptive structural geometry. 4. Light energy: Modifying biocompatible materials; designing system integration | [99,100,102,105,106,109,110] |

Energy storage systems

Energy Storage Systems encompass technologies that store and release electrical energy, mainly comprising batteries and supercapacitors. To address sustainability challenges, researchers have developed eco-friendly electrodes and electrolytes, while structural integration technologies enable miniaturized yet high-performance devices that balance power output with resource efficiency. Furthermore, innovations in the recycling of end-of-life devices and materials will further contribute to building a closed-loop circular economy.

Batteries

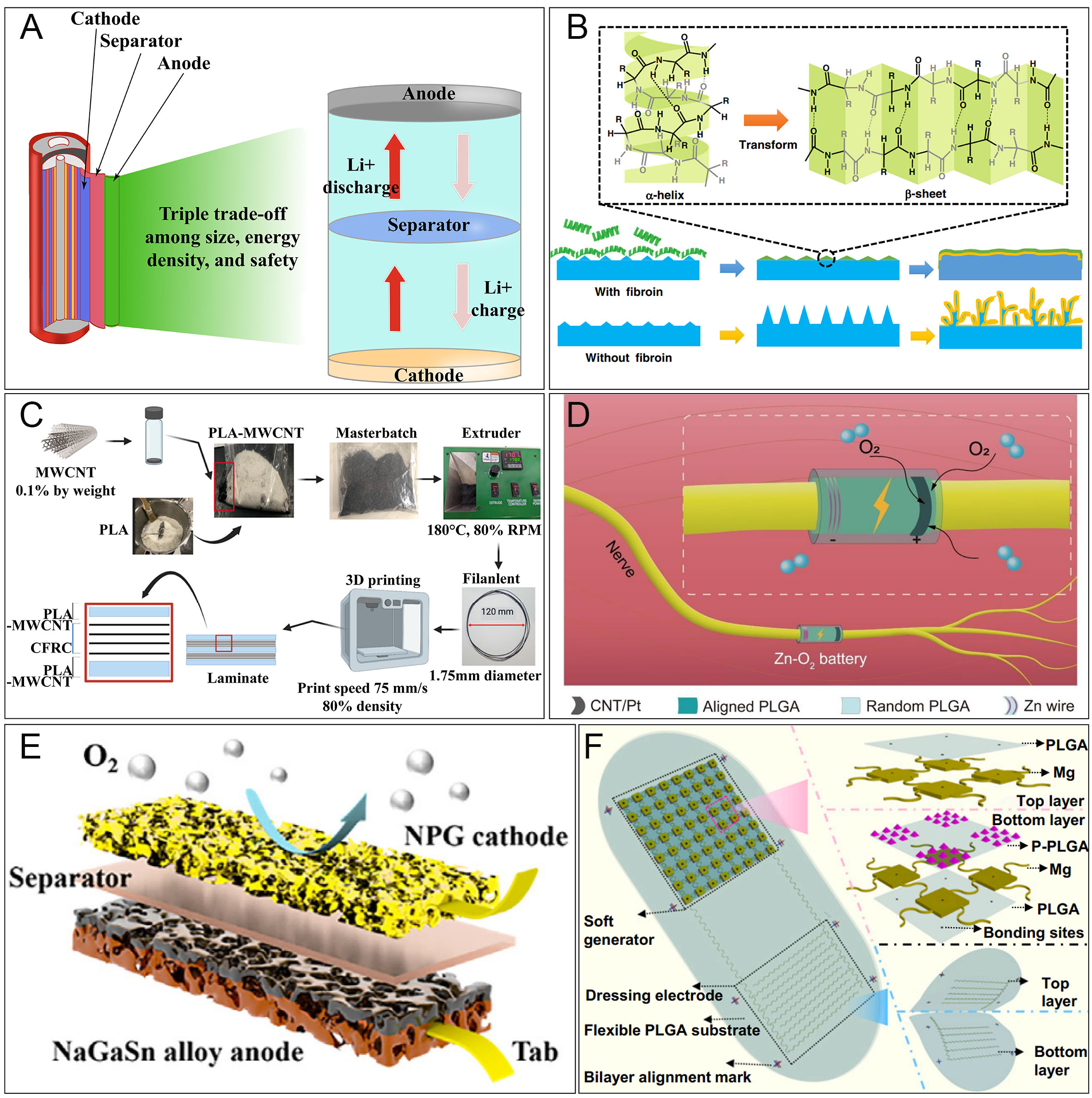

As the primary energy storage unit in implantable electronic medical devices, batteries provide sustained operation for pacemakers and neurostimulators through high energy density and long-term stability. The core mechanism of batteries operates on electrochemical principles: energy conversion occurs through electrode redox reactions and ion migration[35]. Take traditional LIBs as an example: the electrolyte fills between the electrodes, and the separator permits lithium ions to pass through while blocking electrons [Figure 1A]. During discharge, an oxidation reaction occurs at the negative electrode, causing lithium ions to deintercalate and release electrons. The ions migrate through the electrolyte to the positive electrode, while the electrons flow through the external circuit to power the device before reaching the positive electrode. At the positive electrode, a reduction reaction integrates lithium ions with electrons, converting chemical energy into electrical energy. Currently, implantable medical devices mainly use primary batteries, whose limited lifespan necessitates replacement through invasive surgery once depleted. The triple trade-off among size, energy density, and safety faced by batteries fundamentally stems from the conflict between material limits and electrochemical mechanisms: (1) Material limitations: Increasing energy density necessitates thick electrodes or highly active materials (e.g., silicon-based anodes, which can expand by 300%-400% upon full lithiation), but thick electrodes prolong ion diffusion paths and exacerbate polarization, while repeated material expansion compromises electrode integrity and may trigger thermal runaway; (2) Structural constraints: Safety protection structures occupy space, often requiring thinner separators or reduced electrolyte volumes. However, ultra-thin separators with insufficient mechanical strength risk penetration by lithium dendrites, and insufficient electrolyte diminishes thermal capacity and weakens heat dissipation[36,37].

Figure 1. Next-generation batteries. (A) Battery operating mechanism; (B) Silk protein molecules act as a protective layer to mitigate dendrite formation in lithium metal anodes[39]; (C) The 3D MOF-cellulose composite electrolyte enables high-performance solid-state LIBs[41]; (D) Implantable zinc-oxygen battery for neural regeneration[42]; (E) Implantable Na-oxygen battery[43]; (F) A self-powered implantable electrostimulation device for bone fracture healing[44]. Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature (B), MDPI (C), Wiley (D), Elsevier (E), National Academy of Sciences (F), respectively.

Relevant research addresses spatial constraints in battery structures by designing new composite electrolytes to improve lithium deposition and thermal stability[38]. For example, Wang et al. demonstrate that silk fibroin, released from an electrospun interlayer, through α-helix to β-sheet conformational transition upon preferential adsorption at lithium bud tips, redistributes local electric fields to suppress dendrite nucleation, providing a biomimetic solution for high-performance lithium-metal batteries[39] [Figure 1B]. In addition, solid-state LIBs demonstrate significantly higher energy density and extended service life compared to conventional liquid LIBs. Xu et al. innovatively constructed a composite solid polymer electrolyte containing a gelatin network-reinforced poly(vinylene carbonate-acrylonitrile) (PVN) matrix[40]. Adding an appropriate amount of gelatin to the PVN matrix forms a uniform three-dimensional Li+ conductive network, which not only reduces the crystallinity of the polymer and promotes the dissociation of lithium salts but also constructs new rapid ion transport channels, thereby enhancing the Li+ transference number

As promising green energy storage systems, metal-air batteries have attracted significant attention owing to their high specific capacity and energy density. Compared with traditional LIBs, metal-air batteries can use body fluids as electrolytes and ambient oxygen as active cathode materials. Their small size and high flexibility make them suitable for minimally invasive implantation, while providing higher energy density, better biocompatibility, and more flexible designs. Li et al. developed an implantable tubular Zn-O2 battery that integrates a nerve conduit to provide in situ electrical stimulation to effectively promote nerve regeneration[42] [Figure 1D]. Additionally, Lv et al. developed the implantable Na-O2 battery using a nanoporous gold cathode and NaGaSn alloy anode, combined with an ion-exchange membrane and biocompatible PLCL encapsulation[43] [Figure 1E]. Its unique oxygen-depleting function during discharge enables dual applications: powering bioelectronic implants and offering biotherapy potential for hypoxia-related diseases such as cancer, revolutionizing implantable battery design by merging energy storage with therapeutic capabilities. Recent years have witnessed transformative advances in degradable materials for transient implants. A paradigm-shifting innovation involves Mg-MoO₃ batteries for bone healing monitoring [Figure 1F]. Preclinical studies in rat models have shown that these implantable systems can degrade completely within 18 weeks, aligning with the natural timeline of bone regeneration, while producing negligible inflammatory responses[44]. This controlled degradation not only obviates the need for device retrieval but also minimizes adverse tissue reactions, thereby supporting the overall healing process.

Supercapacitors

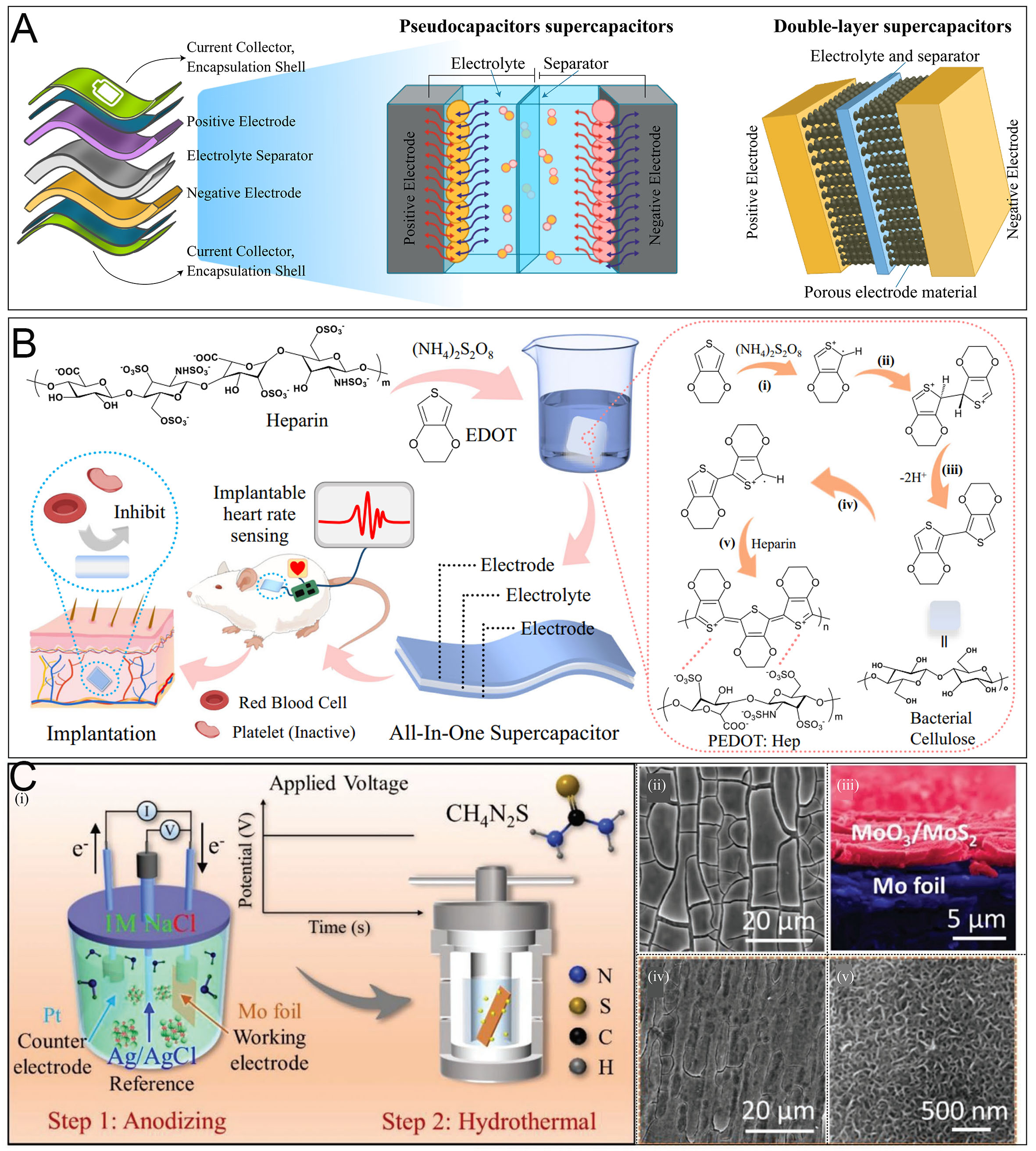

Supercapacitors are classified into two categories by charge storage mechanisms: Double-layer capacitors (DLCs): rely on reversible electrostatic adsorption/desorption of electrolyte ions at the electrode surface, involving no chemical reactions; Pseudocapacitors: achieve energy storage through surface or near-surface redox reactions of electrode materials[45] [Figure 2A]. During charging, positive and negative charges accumulate on respective electrodes, storing energy as electrostatic potential energy (DLCs) or electrochemical potential (pseudocapacitors); during discharging, electron flow through the external circuit releases energy, while ions desorb from electrodes and migrate back to the electrolyte bulk in DLCs, or participate in reverse redox reactions in pseudocapacitors, maintaining charge balance. Compared with LIBs, supercapacitors exhibit a longer cycle life, significantly reducing replacement frequency and alleviating resource scarcity pressures[46,47]. More crucially, their millisecond-level charge/discharge kinetics enable real-time power delivery for transient biosignal monitoring - a capability fundamentally constrained in battery-powered systems due to sluggish ion diffusion in bulk electrodes[48,49]. Conventional supercapacitors remain unsuitable for implantable applications, primarily due to the cytotoxicity of organic electrolytes and the chronic tissue inflammation induced by long-term implantation. Recent advancements in new materials, material modification techniques, and encapsulation technology have enabled the integration of supercapacitors into implantable biomedical devices[49,50]. For example, Wang et al. developed an anticoagulant composite electrode material by doping heparin (Hep), a natural anticoagulant macromolecule, into poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) via chemical oxidative polymerization[51] [Figure 2B]. This way can simultaneously enhance electrical conductivity and inhibit thrombin activity, demonstrating excellent hemocompatibility.

Figure 2. Next-generation supercapacitors. (A) Supercapacitors Operating Mechanism; (B) An anticoagulant supercapacitor for implantable applications[51]; (C) Heterostructured MoO3-MoS2 composites empower high-performance energy storage systems through interfacial charge redistribution[55]. Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature (B), Wiley (C).

Supercapacitors primarily rely on double-layer capacitance or surface-confined redox reactions, rather than bulk ion insertion. Compared to batteries, this surface-dominated charge storage mechanism inherently limits their charge storage capacity, resulting in lower energy density for supercapacitors[52]. Researchers are advancing supercapacitor energy density through innovative materials and structural optimizations.

The sustainable development of the supercapacitor can be promoted through the collaborative integration of novel material designs and self-powered systems, enabling self-powered solutions without external dependencies.

Biological energy harvesting systems

Alongside energy storage, energy harvesting strategies are actively investigated to extract energy directly from the human body. Biological energy harvesting systems convert naturally available energy, such as biologic substrate (e.g., glucose), mechanical motion, thermal gradients, or biochemical reactions, into electricity, thereby enabling self-powered medical device operation without external charging[13,14]. By integrating such systems with implantable electronic medical devices, these systems realize efficient energy recycling in the body. Researches in this area emphasize ongoing improvements in efficiency, durability, and overall system integration, which are essential for transitioning these technologies into clinical applications.

Biofuel cells

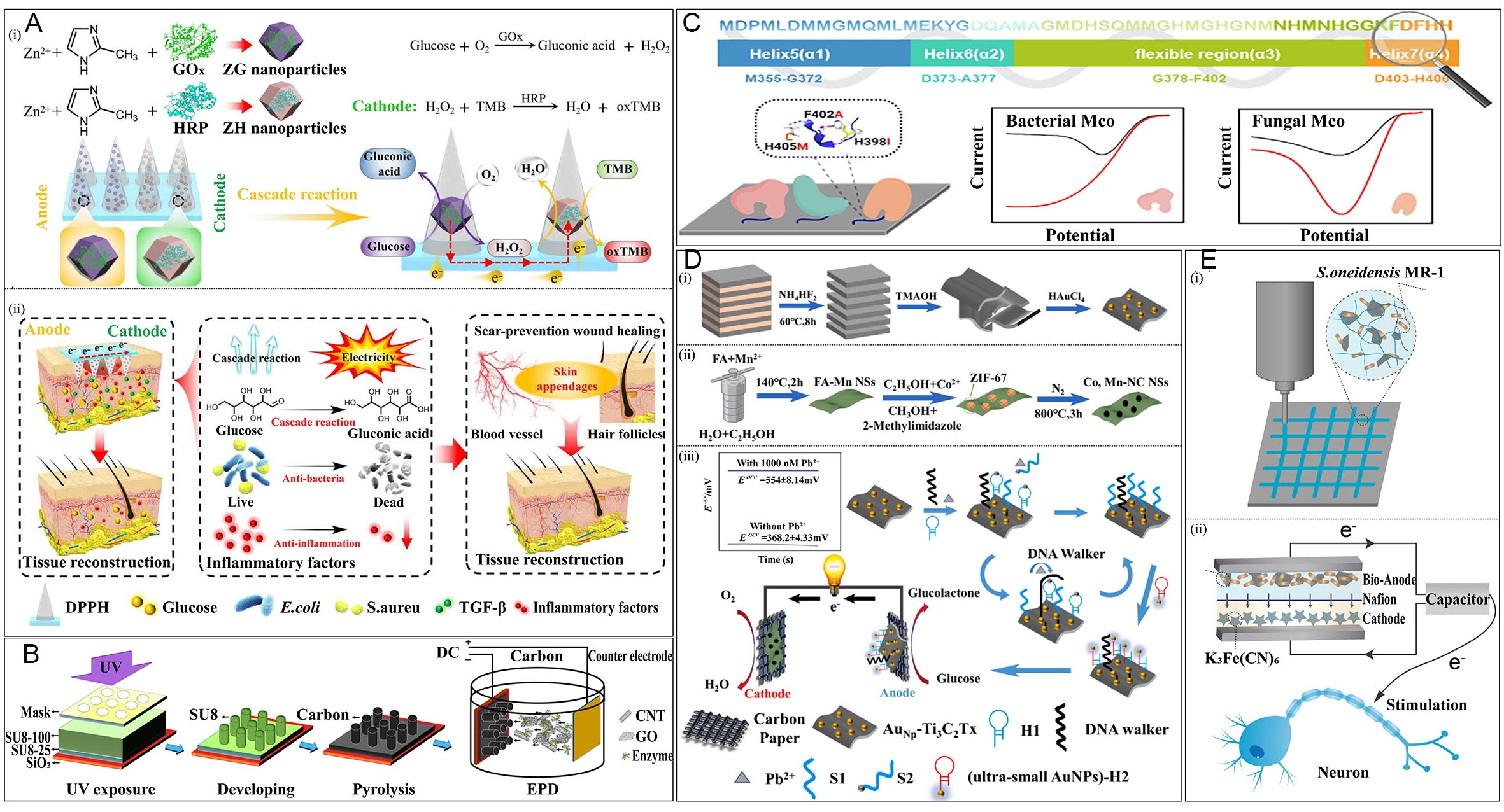

BFCs, a specialized category of fuel cells, utilize biocatalysts (such as microorganisms or enzymes) to oxidize biochemical substrates, generating electricity through electrochemical redox reactions[56,57]. The main substrates oxidized by BFCs are glucose and lactic acid, both of which are abundant in human biofluids such as blood, sweat, and tears[58]. Their natural replenishment through metabolic processes allows BFCs to function sustainably without external recharging or battery replacement. Moreover, BFCs generate voltage and current outputs that vary with substrate concentration. This dependence allows them to detect disease-related biomarkers (e.g., glucose in diabetes) at specific thresholds while simultaneously powering therapeutic devices (e.g., insulin pumps), achieving integrated detection and treatment. For example, BFCs are being actively researched to manage diabetes and related complications. Maity et al. developed a blood glucose therapy device in which a BFC is activated during hyperglycemia (blood glucose > 10 mmol/L), catalyzing glucose conversion to electricity[58]. The generated electrical output then stimulates engineered β-cells to release insulin, enabling real-time monitoring and autonomous closed-loop regulation of blood glucose levels. Zhang et al. designed and fabricated a self-powered enzyme-linked microneedle patch[59] [Figure 3A]. Through enzymatic cascade reactions, this patch not only reduces local hyperglycemia in diabetic wounds but also generates therapeutic microcurrents to accelerate tissue healing. As the high selectivity of the catalysts prevents cross-interference between the cathode and anode reactions, there is no need to physically separate the anode and cathode (e.g., by using a separator), enabling the development of miniature membrane-free BFCs[60,61]. By integrating this advantage with the carbon microelectromechanical systems technique, Song et al. fabricated micrometer-scale diameter micropillar arrays[62] [Figure 3B]. These structures enhanced the electrode’s effective surface area and integration compatibility, advancing low-power smart implantable medical device production.

Figure 3. Biofuel cells. (A) Self-powered enzyme-linked microneedle patch for scar-prevention healing of diabetic wounds[59]; (B) A membraneless high-power biofuel cell based on 3D reduced graphene oxide/carbon nanotube micro-arrays[62]; (C) Protein engineering for design binding peptides[69]; (D) Mxene-based capacitive enzyme-free biofuel cell self-powered sensor[74]; (E) 3D printable living hydrogels as portable bio-energy devices for neuron stimulation[75]. Reproduced with permission from American Association for the Advancement of Science (A), Springer Nature (B), American Chemical Society (C), Elsevier (D) and Wiley (E), respectively.

Depending on the type of catalyst, BFCs can be divided into three categories: abiotic, enzymatic and microbial[63]. Among them, enzymatic BFCs (EBFCs) are considered one of the most promising sustainable energy sources due to their high biocompatibility and mild operating conditions. However, the main challenges of EBFCs are limited output power and poor operational stability. This is mainly due to the susceptibility of catalytic enzymes to inactivation by environmental fluctuations[64,65]. Additionally, oxidative stress and biological fouling (e.g., protein adsorption and cell attachment) can further degrade the performance of implantable devices[66]. To address these issues, protein engineering can optimize enzyme structures to enhance intrinsic stability and catalytic efficiency, while enzyme immobilization improves operational stability by anchoring enzymes to solid supports[67,68]. Zhang et al. used protein engineering to design binding peptides to improve the oriented immobilization efficiency of multicopper oxidases on carbon nanotube electrodes, thereby enhancing the electron transfer rates and catalytic performance[69] [Figure 3C]. Besides, most EBFCs use only one or two oxidoreductases, which cannot achieve complete oxidation of the substrate, resulting in low energy conversion efficiency[70,71]. Therefore, multi-enzyme systems could be designed to completely oxidise the biofuel to improve overall energy efficiency[72]. However, enzyme cascades introduce challenges including increased complexity and enzyme compatibility issues. Specifically, variations in optimal temperature and pH among enzymes can disrupt the operational stability of EBFCs.

Compared to the complex production and purification conditions for enzyme catalysts, abiotic catalysts are relatively inexpensive, readily available, and more suitable for long-term storage and operation. These advantages make them easier to manufacture on a large scale. Maiti et al. successfully fabricated gold nanostructures with high catalytic activity through a multi-step amperometric electrodeposition method in two soft templates, demonstrating their potential as anode catalysts in abiotic BFCs[73]. Ji et al. developed an enzyme-free BFCs loaded with ultra-small gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) exhibiting glucose oxidase-like properties, and proposed a signal amplification mechanism synergistically integrating the capacitive anode (based on Au NPs-Ti3C2Tx heterostructures) and enzyme-free catalysis regulated by DNA walker technology[74] [Figure 3D].

Microbial BFCs use bacteria to break down organic substrates and generate electrons[63]. However, they have rarely been used in humans due to their susceptibility to bacterial infections and exposure to bacterial toxins. With advances in hydrogel-based biocompatible materials, synthetic biology-based microbial engineering, and 3D-printed manufacturing, significant breakthroughs have been made in developing implantable microbial BFCs. Wang et al. report a miniaturized and portable microbial BFC using living hydrogels containing conductive biofilms encapsulated in an alginate matrix for nerve stimulation[75] [Figure 3E]. This study utilizes rational genetic engineering techniques (e.g., plasmid transformation and biofilm optimization) to design microbial strains with enhanced metabolic activity and energy output efficiency, suggesting a promising direction for the development of microbial BFCs.

Current BFCs exhibit limited operational lifetimes (typically months), restricting their use in long-term implantable devices such as pacemakers. However, they have been applied to self-powered biosensors, drug pumps and low-power devices. Some researchers have attempted to interface BFCs with charge pumps and capacitors to boost their output voltage and extend operational duration[76]. Meanwhile, machine learning is accelerating progress in related fields by enabling rapid screening of engineered enzyme strains and optimizing synthetic biological circuits for energy conversion efficiency[77].

Nanogenerators

Nanogenerators are energy-harvesting systems that convert various forms of energy, such as thermal energy (from temperature gradients), bioelectric potential and biomechanical energy, into electrical energy[13,14]. Compared with BFCs, nanogenerators utilize a broader spectrum of energy sources and can harvest energy continuously from human activities (e.g., heartbeats, breathing, and walking), enabling stable operation in dynamic environments[78,79]. Furthermore, by avoiding the reliance on biologic substrates and catalysts, the materials for nanogenerators are more abundant, enabling the development of flexible energy supply systems. Besides, nanogenerators fabricated from biodegradable materials such as PLA, cellulose, and silk protein can be naturally degraded within the body while providing on-demand energy output. Due to these advantages, nanogenerators have a wider range of application scenarios.

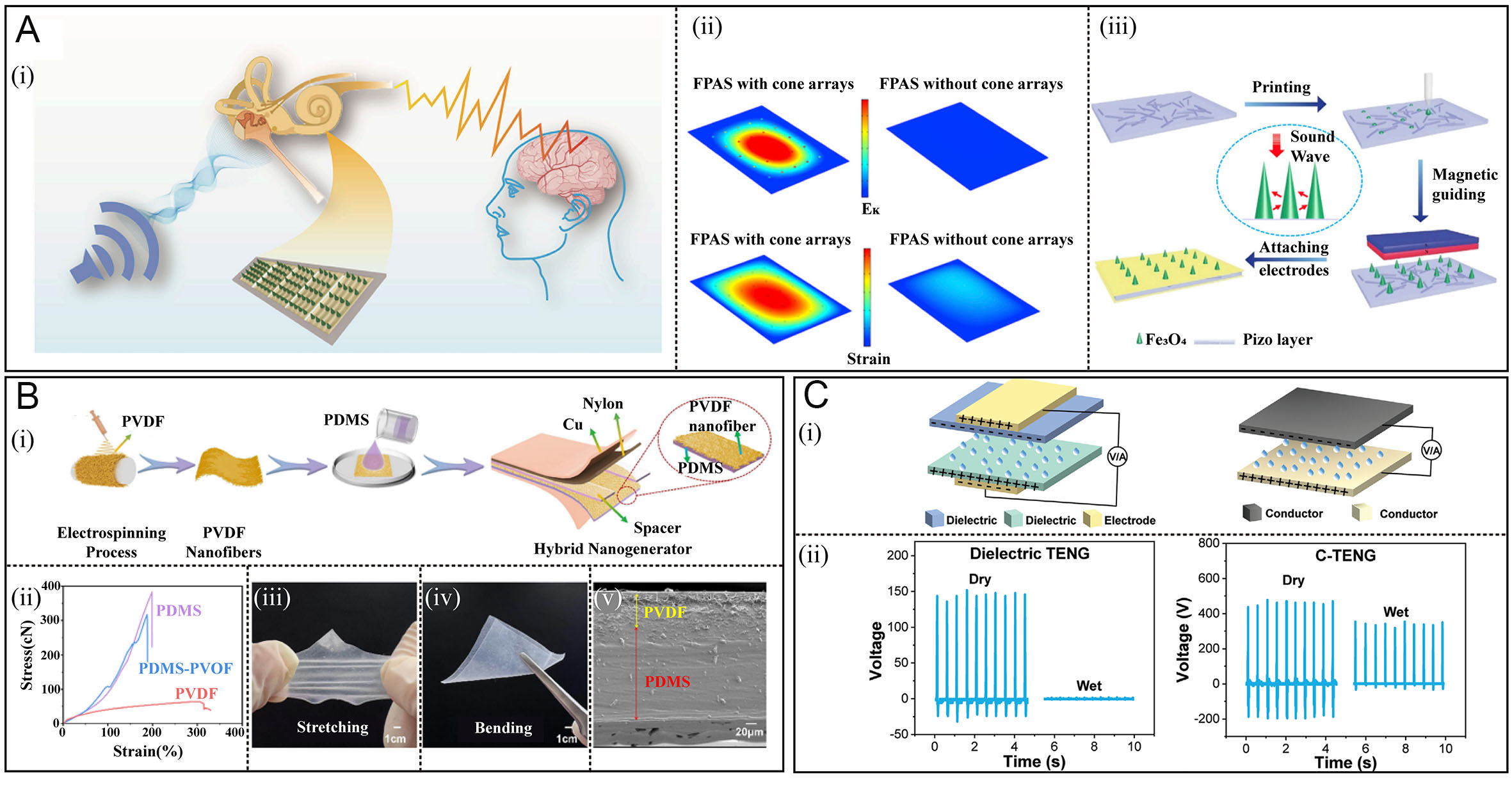

The core components of the piezoelectric nanogenerator (PENG) are piezoelectric materials, which have a typical non-centrosymmetric crystal structure[80,81]. When stress is applied to the piezoelectric material, the internal lattice is deformed, generating an electric dipole moment aligned with the stress direction and forming a potential difference[80,81]. On the other hand, the triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) is an energy harvesting technology based on the coupling of the triboelectric effect and electrostatic induction[82]. Its core consists of two materials with different electron affinities. Upon contact and subsequent separation, one material tends to gain electrons (becoming negatively charged), while the other loses electrons (positively charged). Repetitive mechanical movements (e.g., friction or vibration) drive this process, inducing periodic charge transfer through electrostatic induction, which ultimately generates current. Based on this energy harvesting method, PENG and TENG have been investigated for use in implantable medical devices such as cardiac pacemakers, cochlear implants, and cartilage repair scaffolds[83,84,86]. Xiang et al. developed a flexible piezoelectric acoustic sensor (FPAS) with microcone arrays using lead-free multicomponent perovskite rods through direct writing and magnetic-field-assisted methods, achieving audio recording, speech recognition, and human-computer interaction[83] [Figure 4A]. Although both can convert mechanical energy into electricity, PENG exhibits higher efficiency in harvesting high-frequency mechanical energy, whereas TENG is more suitable for low-frequency biomechanical energy[84,85]. Knee motion consists of low-frequency continuous compression and intermittent contact separation. To leverage these biomechanical properties, Chen et al. proposed a single-layer composite membrane by embedding electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) nanofibers into the PDMS surface[86] [Figure 4B]. The β-crystalline phase of the PVDF nanofibers exhibits spontaneous polarization. When subjected to pressure, the deformation of the fibers causes changes in the dipole moment, thereby generating piezoelectric charges. Concurrently, the nanofiber-induced rough surface synergizes with PDMS (tribo-negative material) to enhance triboelectrification. This approach eliminates structural complexity and integration bottlenecks, realizing a dual-functional integrated system for wearable self-powered sensing. This system utilizes rehabilitation training to generate self-sustaining electrical stimulation, significantly accelerating bone regeneration by activating Ca2+ dependent osteogenic signaling pathways (PI3K/AKT, WNT) and mechanosensitive channels (Piezo1/2). Currently, the primary limitations of PENG lie in their restricted material diversity. For instance, traditional high-performance inorganic options such as lead-based piezoelectric ceramics pose health risks due to lead toxicity, while emerging biodegradable materials, despite their high biocompatibility and degradability, exhibit low piezoelectric coefficients[87,88]. However, recent strategies such as mechanical annealing can significantly enhance their piezoelectric performance[88]. TENGs are highly sensitive to environmental conditions - humidity and temperature fluctuations can degrade their material properties, necessitating protective encapsulation. However, Sun et al. utilized poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) and copper/aluminum to construct a conductive TENG (C-TENG). In this device, PEDOT:PSS serves as the triboelectric layer, where the migration rate of charges within the material is significantly higher than the rate of leakage into the air[89] [Figure 4C]. Leveraging matched density of states, it maintains nearly full performance at 100% humidity and ~80% output with water droplets[90]. Furthermore, both PENGs and TENGs may suffer from output attenuation under repetitive mechanical loading.

Figure 4. Nanogenerators. (A) High-performance microcone-array flexible piezoelectric acoustic sensor based on multicomponent lead-free perovskite rods[83]; (B) Hybrid piezoelectric/triboelectric wearable nanogenerator based on stretchable PVDF-PDMS composite films[86]; (C) C-TENG maintains high output in humid or wet conditions[89]. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier (A), American Chemical Society (B), and Wiley (C).

Thermoelectric nanogenerators (TEGs) utilize the minute temperature difference between human skin and the environment to directly convert thermal energy into electrical energy via the Seebeck effect. The physical mechanism is as follows: in a circuit composed of two dissimilar conductors or semiconductors, a temperature gradient at the contact points drives charge carriers (electrons or holes) to diffuse from the high-temperature end to the low-temperature end[91]. This diffusion causes charge accumulation at the cold end, generating a potential difference. The process is sustained by the balance between the carrier diffusion flux and the internal electric field. TEGs increasingly power wearable devices for smart health monitoring[92,93]. The advancement of this technology has been driven by breakthroughs in flexible materials. However, due to the inherent variability of thermal energy harvested from the human body (e.g., fluctuations in skin temperature or ambient interference), the power output of TEGs may exhibit instability. In addition, current research explores various physiological gradients (e.g., thermal, ionic, or humidity gradients) within the human body for electricity generation[94,95]. For instance, Yan et al. developed a self-powered system by integrating a polyacrylamide/carboxymethyl chitosan (PAM/CMCS) organic ionic hydrogel (containing LiBr and ethylene glycol) as a water reservoir with a carbon nanotube-modified thermoplastic polyurethane (CNT-TPU) for moisture adsorption[95]. This system establishes a stable humidity gradient to harvest energy directly from wound exudate or ambient moisture. By combining the humidity-driven power generation with the synergistic effects of antibacterial activity and immune regulation, it provides an efficient closed-loop therapeutic strategy for chronic wound healing.

Recent studies show that researchers are developing new nanostructured materials and hybrid systems that increase energy conversion efficiency and stability[96,97]. These advancements are paving the way for widespread application in self-powered sensors, wearable electronics, and implantable biomedical devices. Furthermore, the integration of nanogenerator technology with the Internet of Things (IoT) is expected to drive innovations in distributed sensor networks and smart infrastructures.

Environmental energy transfer systems

Energy harvesting is a method to power implantable medical devices by utilizing low-grade energy sources, such as magnetoelectric induction, ultrasonic waves, optical wireless transmission, and radiofrequency energy[15-18]. Environmental energy transfer systems used in medical devices have functional limitations under specific physiological or environmental conditions.

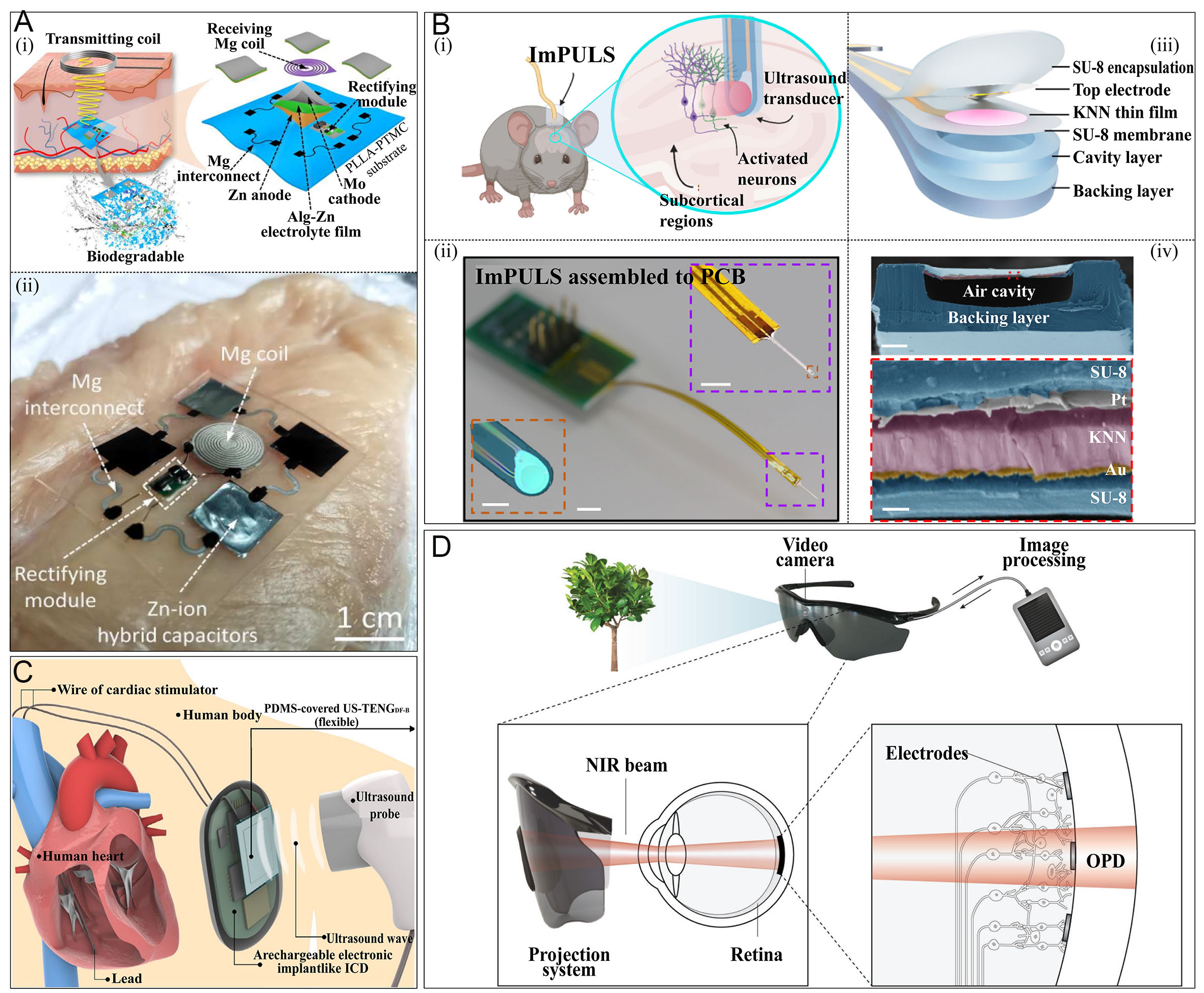

Magnetoelectric induction energy transfer technology operates on Faraday's law: an alternating current in the transmitter coil creates a changing magnetic field. When this field interacts with a nearby receiver coil, the changing magnetic flux induces an electromotive force, thereby forming a current and transmitting electrical energy. This technology achieves high efficiency at millimeter-scale distances, but requires precise alignment between external transmitter and implanted receiver coils. Additionally, electromagnetic fields may induce eddy currents in biological tissues, generating local heating that poses thermal damage risks. Furthermore, transmission is vulnerable to disruption by metallic objects or electromagnetic interference[16,98]. Sheng et al. developed a soft implantable energy system integrating laser-patterned magnesium coils for efficient wireless energy transfer and a biodegradable zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitor (MoS2/reduced graphene oxide (rGO) heterojunction cathode, ion-crosslinked zinc alginate gel (Alg-Zn) electrolyte) as an energy buffer[99] [Figure 5A]. The induced alternating current was rectified into direct current via a miniaturized circuit, while the supercapacitor suppressed heat generation during operation by stabilizing power output. Yu et al. report that groundbreaking advances in magnetoelectric effect research bridge theoretical and practical applications[100]. The use of a 250-kHz low-frequency magnetic field substantially reduces tissue-specific absorption rate, wirelessly delivering power at 30-mm depth. Via magneto-mechano-electrical conversion, this work presents a composite magnetoelectric transducer and the first magnetoelectrically powered micro-neurostimulator, which enables programmable neuromodulation. Combining magnetoelectric induction technology with energy storage systems can improve power stability, reduce the risk of thermal effects, and promote the use of biodegradable materials in efficient and safe implantable devices.

Figure 5. Environmental energy transfer systems. (A) A low-impedance magnesium coil for wireless energy harvesting[99]; (B) A wirelessly rechargeable implantable zinc-ion battery[105]; (C) Body-conforming ultrasound receiver enabling efficient and stable wireless charging in deep tissues[106]; (D) Near-infrared tandem organic photodiodes for future application in artificial retinal implants[109]. Reproduced with permission from American Association for the Advancement of Science (A), Springer Nature (B), and Wiley (C and D).

Radio frequency (RF) energy transfer technology utilizes high-frequency electromagnetic waves for wireless power transmission. A transmitter antenna array locates the target device and directs the RF energy towards it. The receiver captures this energy, rectifies it into direct current, and uses it for charging. While this technology can charge devices from a distance of several meters, it suffers from RF wave attenuation caused by dielectric relaxation and conductive loss in biological tissues. Its relatively low energy conversion efficiency limits its primary application to low-power medical implants[38,101]. Abdolrazzaghi et al. utilized superoscillation technology in a Huygens' Box cavity to achieve subwavelength focusing (0.35 λ)[102]. By compressing and dynamically steering RF energy, they overcame the limitations of traditional RF technology in resolution, efficiency, and safety. This approach delivers 1.8 V to 2.5 cm-deep implants while suppressing off-target tissue heating via field shielding, offering a breakthrough for implantable medical devices.

Ultrasound-driven nanogenerators offer a promising alternative for wireless charging of implantable medical devices, even in deep-tissue environments or under mechanical bending conditions[103,104]. However, energy reflection loss may occur at material-tissue interfaces due to acoustic impedance mismatch, particularly between piezoelectric materials and biological tissues[104]. Current research focuses on three synergistic strategies to ensure stable wireless energy transmission in deep tissues: (1) modifying biocompatible materials; (2) designing flexible encapsulation; and (3) configuring adaptive structural geometry. Hou et al. designed an implantable piezoelectric ultrasound stimulator (ImPULS) that directly addresses the acoustic impedance mismatch between piezoelectric materials and biological tissues through a flexible packaging design, optimization of biocompatible piezoelectric materials, and a direct implantation strategy for deep brain regions[105]. The device precisely activates neurons using localized ultrasonic pressure of 100 kPa and ensures long-term efficient energy transmission through durable packaging and thermal management [Figure 5B]. Imani et al. utilized an ultra-thin polyfluoroalkoxy (PFA)/polyurethane (PU) flexible friction layer to reduce interface reflection and enhanced charge density by introducing a polarized P(VDF-TrFE)/CaCu3Ti4O12 (CCTO) composite layer[106]. The device's adaptive curved surface structure could capture sound waves and withstand bending. A PDMS encapsulation layer was integrated to overcome acoustic impedance mismatch, enabling the device to output a stable voltage of 26 V at 35 mm depth in tissue, providing a wireless power solution for deeply implanted devices such as artificial hearts [Figure 5C].

The conversion of light energy into electrical energy is achieved through the photovoltaic effect in semiconductor materials. Traditional silicon-based semiconductor materials exhibit high hardness and poor flexibility, making them mechanically incompatible with soft biological tissues (e.g., the heart, nerves, or retina)[107,108]. Additionally, limitations include insufficient penetration depth (currently inadequate for deep-tissue organs) and potential thermal injury from prolonged light exposure. Simone et al. addressed the limitations of traditional silicon-based retinal implants in voltage, flexibility, and resolution by designing tandem organic photodiodes[109] [Figure 5D]. Their study validated the feasibility of efficient and safe neural stimulation under near-infrared light, paving the way for clinical applications of flexible high-resolution artificial retinas. Zhang et al. developed an implantable self-powered pacemaker utilizing magnesium/zinc-MoO3 electrodes, with energy supplied by body fluid electrolysis and control enabled by transcutaneous near-infrared light[110]. The device can be implanted up to 6 cm deep and degrades completely within 1 to 2.5 years post-surgery, eliminating the need for secondary device removal. These optoelectronic devices offer significant advantages, such as lower infection risk due to wireless operation and immunity to electromagnetic interference, making them ideal for shallow implants such as cardiac pacemakers, neural stimulators, and wearable monitors. Future advancements may involve multi-energy harvesting and adaptive light-control technologies to improve power output stability and safety.

In general, the output power of the environmental energy transfer system is inherently low and significantly influenced by environmental fluctuations. Therefore, such systems typically require energy storage units (e.g., supercapacitors or micro-batteries) to ensure stable operation.

TRANSLATIONAL CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Translating advanced implantable energy technologies from the laboratory to clinical application is a multifaceted challenge that spans standardized testing, scalable manufacturing and sustainability considerations. Addressing these challenges, however, requires not only technological innovation but also robust regulatory and ethical frameworks to ensure patient safety and environmental stewardship during implementation.

Long-term biocompatibility

One of the primary challenges in translating novel implantable devices to clinical implementation is ensuring long-term biocompatibility. To address this, there is a critical need for dynamic, real-time, and uniform testing protocols capable of simulating in vivo conditions. We suggest the entire long-term biocompatibility assessment process should be divided into three stages: (1) Pre-implantation phase: Materials must pass biocompatibility testing per the ISO 10993 series. Concurrently, energy systems must undergo accelerated aging tests to simulate electrochemical corrosion in body fluid environments and assess the cytotoxicity of released substances; (2) Preclinical trial phase: The energy system must be evaluated in large animal experiments to assess whether they induce immune rejection or autoimmune reactions (such as complement activation, abnormal lymphocyte proliferation), with regular monitoring of serum immunoglobulin levels and histopathological changes. Simultaneously assess the organ accumulation toxicity of material releases on liver and kidney function; if the material is biodegradable, clarify its degradation rate and the metabolic pathways of its degradation products; and (3) Clinical trial phase: Long-term safety must be tracked through imaging studies [magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/computed tomography (CT)], blood biochemistry, patient-reported outcomes, and analysis of potential failure causes of energy systems. These protocols must be tailored to account for the complex interactions between emerging materials and biological tissues over extended periods. Constructing organoids to evaluate the biocompatibility, toxicity, and physiological functionality of new materials may be a feasible solution[111].

Holistic energy solutions

The systematic integration of energy harvesting and storage remains a key challenge. Current research focuses on the co-design of flexible energy harvesting systems or environmental energy transmission systems with coupled energy storage technologies, leveraging their complementary advantages to achieve continuous energy supply - the harvesting/transmission systems are responsible for continuously capturing environmental energy, while the storage systems ensure the stable output of electricity to devices; Such multifunctional architectures overcome traditional limitations such as short lifespan and bulkiness, while customized material interfaces significantly boost energy conversion efficiency. To achieve sustainability goals, magnesium-based/zinc-based alloys, with their excellent corrosion resistance, high strength, and lightweight properties, are promising materials for constructing long-lasting, non-degradable power supply systems, while advancements in industrial waste recycling technology further ensure the sustainability and recyclability of material sources; On the other hand, natural biomaterials such as silk proteins and citrate salts can be controlled to degrade within the body through active metabolic processes such as enzymatic degradation and phagocytosis. Their degradation products (amino acids, peptides, sugars, and other small molecules) can be reabsorbed and utilized by the human body. With their excellent biocompatibility and controllable degradation, these materials represent a cutting-edge direction in the development of degradable energy systems.

Closed-loop surveillance

To accelerate the clinical adoption of sustainable energy systems, systematic cooperation between hospitals, enterprises, and regulatory authorities is essential. Hospitals can establish implantable energy clinical registries to enable real-time adverse reaction monitoring and secure clinical data sharing, while respecting patient privacy. Enterprises should leverage cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and 3D printing to reduce manufacturing costs. Furthermore, utilizing registry data, they could also address differentiated energy supply needs across age groups (e.g., adolescents and the elderly) and advance targeted innovations. For instance, scalable manufacturing such as the roll-to-roll dry coating process has demonstrated significant potential for scalable and cost-effective manufacturing of LIBs, particularly through precise control of electrode microstructure and elimination of toxic solvents[112]. This innovation in advanced materials science and manufacturing processes could enable sustainable energy system design, offering new pathways for future applications. Regulatory authorities can establish a priority approval channel for new materials (e.g., biodegradable devices), while mandating long-term biocompatibility data as prerequisites. Additionally, a surveillance system must trigger investigations if adverse events exceed safety thresholds, ensuring sustained reliability.

Intelligent network architectures

Driven by IoT and AI, implantable electronic medical devices establish deep interoperability with multi-source databases and intelligent terminals. This technological integration necessitates advanced energy management solutions, making the convergence of multi-source energy systems with AI a core trend in implantable devices. Using smart biosensors to collect real-time physiological parameters (e.g., electrocardiogram and neural signals) combined with machine learning algorithms, the system can predict energy demand peaks. For example, when patient activity causes a surge in pacemaker power demand, the energy system captures kinetic energy through a PENG while leveraging supercapacitors’ rapid response to meet instantaneous high-power needs. During resting states, only the nanogenerator sustains baseline power supply. Through this dual-mode operation, the system could significantly reduce overall energy consumption. Furthermore, by monitoring key parameters (e.g., power stability, charge/discharge depth, temperature), the system proactively alerts to potential failures, enhancing patient safety. Through integrated sensors and closed-loop feedback mechanisms, these devices provide accurate health monitoring and early disease detection by tracking multi-modal biometric parameters in real-time. Additionally, they enable patients to track their status via smartphone applications and automatically synchronize critical data with clinicians, thereby facilitating a hospital-community-home connected health management model.

In summary, while significant progress has been made in developing advanced implantable energy systems, the journey from the laboratory to clinical application is fraught with technical, regulatory, ethical, and environmental challenges. Overcoming these challenges requires a concerted effort that spans standardized testing, scalable manufacturing, robust clinician-engineer partnerships, and a commitment to sustainability and patient engagement. Recent advancements suggest a promising future for the clinical translation of these transformative technologies, which are poised to improve patient outcomes and foster a more sustainable healthcare ecosystem.

CONCLUSION

The field of implantable batteries is undergoing a transformative evolution, marked by the emergence of sustainable alternatives such as sodium and zinc, the use of degradable materials and radical innovations in other implantable energy systems for autonomous electricity generation. While lithium technologies remain indispensable for long-term devices such as pacemakers, their environmental and supply chain limitations have spurred exploration of sodium-ion and zinc-air batteries, which offer comparable performance with reduced ecological footprints. Emerging wireless and hybrid energy systems, though promising in enabling self-powered implants, must overcome challenges in energy reliability and patient compliance to achieve widespread adoption. Preclinical breakthroughs in degradable materials, particularly magnesium and zinc-based systems, herald a future where temporary implants harmonize with tissue regeneration and green healthcare mandates, eliminating surgical retrieval and promoting resource efficiency. Translating these advancements into clinical practice demands rigorous standardization of materials, scalable manufacturing techniques such as roll-to-roll printing, and ethical frameworks integrating real-time degradation monitoring for patient safety. Ultimately, the convergence of interdisciplinary collaboration-spanning materials science, clinical medicine, and regulatory innovation-will be pivotal in realizing implantable energy solutions that are not only technologically robust but also environmentally sustainable and patient-centric.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, and writing: Cao, W.; Wang, X.

Supervision: Feng, Y.; Lei, W.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by Shaanxi Provincial Key Research and Development Program (S2024-YF-ZDXM-SF-0256).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Friedman, P.; Murgatroyd, F.; Boersma, L. V. A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of an extravascular implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1292-302.

2. Bai, C.; Li, S.; Ji, K.; Wang, M.; Kong, D. Stretchable microbatteries and microsupercapacitors for next-generation wearable electronics. Energy. Mater. 2023, 3, 300041.

3. Buchman, C. A.; Gifford, R. H.; Haynes, D. S.; et al. Unilateral cochlear implants for severe, profound, or moderate sloping to profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review and consensus statements. JAMA. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck. Surg. 2020, 146, 942-53.

4. McGlynn, E.; Nabaei, V.; Ren, E.; et al. The future of neuroscience: flexible and wireless implantable neural electronics. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002693.

5. Yan, B.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, H. Tissue-matchable and implantable batteries toward biomedical applications. Small. Methods. 2023, 7, e2300501.

6. Zhao, T.; Traversy, M.; Choi, Y.; Ghahreman, A. A novel process for multi-stage continuous selective leaching of lithium from industrial-grade complicated lithium-ion battery waste. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 909, 168533.

7. Kim, Y.; Stepien, D.; Moon, H.; et al. Artificial interphase design employing inorganic-organic components for high-energy lithium-metal batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 20987-97.

8. Wang, S.; Cui, Q.; Abiri, P.; et al. A self-assembled implantable microtubular pacemaker for wireless cardiac electrotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadj0540.

9. Ahn, S. H.; Koh, C. S.; Park, M.; et al. Liquid crystal polymer-based miniaturized fully implantable deep brain stimulator. Polymers 2023, 15, 4439.

10. Lv, Q.; Chen, S.; Luo, D.; et al. An implantable and degradable silk sericin protein film energy harvester for next-generation cardiovascular electronic devices. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2413610.

11. Choi, Y. S.; Yin, R. T.; Pfenniger, A.; et al. Fully implantable and bioresorbable cardiac pacemakers without leads or batteries. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1228-38.

12. Basha, S. I.; Shah, S. S.; Ahmad, S.; Maslehuddin, M.; Al-Zahrani, M. M.; Aziz, M. A. Construction building materials as a potential for structural supercapacitor applications. Chem. Rec. 2022, 22, e202200134.

13. Kabir, M. H.; Marquez, E.; Djokoto, G.; et al. Energy harvesting by mesoporous reduced graphene oxide enhanced the mediator-free glucose-powered enzymatic biofuel cell for biomedical applications. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 24229-44.

14. Lv, Q.; Ma, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. Nanocellulose-based nanogenerators for sensor applications: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129268.

15. Bronner, H.; Doll-Nikutta, K.; Donath, S.; et al. A versatile two-light mode triggered system for highly localized sequential release of reactive oxygen species and conjugated drugs from mesoporous organosilica particles. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2025, 13, 3032-8.

16. Wang, H.; Zhu, C.; Jin, W.; et al. A linear-power-regulated wireless power transfer method for decreasing the heat dissipation of fully implantable microsystems. Sensors 2022, 22, 8765.

17. Imani, I. M.; Kim, H. S.; Shin, J.; et al. Advanced ultrasound energy transfer technologies using metamaterial structures. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2401494.

18. Long, H.; Qian, Y.; Gang, S.; et al. High-performance thermoelectric composite of Bi2Te3 nanosheets and carbon aerogel for harvesting of environmental electromagnetic energy. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 1819-31.

19. Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Electrochemical lithium recycling from spent batteries with electricity generation. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 287-96.

20. Innocenti, A.; Bresser, D.; Garche, J.; Passerini, S. A critical discussion of the current availability of lithium and zinc for use in batteries. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4068.

21. Tran, H. A.; Hoang, T. T.; Maraldo, A.; et al. Emerging silk fibroin materials and their applications: new functionality arising from innovations in silk crosslinking. Mater. Today. 2023, 65, 244-59.

22. Barri, K.; Zhang, Q.; Swink, I.; et al. Patient-specific self-powered metamaterial implants for detecting bone healing progress. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203533.

23. Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, J.; Zhang, P. Materials strategies to overcome the foreign body response. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2304478.

24. Zhou, X.; Hao, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. Covalently grafted human serum albumin coating mitigates the foreign body response against silicone implants in mice. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 34, 482-93.

25. Kim, K.; Min, I. S.; Kim, T. H.; et al. Fully implantable and battery-free wireless optoelectronic system for modulable cancer therapy and real-time monitoring. NPJ. Flex. Electron. 2023, 7, 276.

26. Maduka, C. V.; Schmitter-Sánchez, A. D.; Makela, A. V.; et al. Immunometabolic cues recompose and reprogram the microenvironment around implanted biomaterials. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 8, 1308-21.

27. Maduka, C. V.; Alhaj, M.; Ural, E.; et al. Polylactide degradation activates immune cells by metabolic reprogramming. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2304632.

28. Wu, Z.; Yi, Y.; Hai, F.; et al. A metal-organic framework based quasi-solid-state electrolyte enabling continuous ion transport for high-safety and high-energy-density lithium metal batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 22065-74.

29. Cai, G.; Chen, A. A.; Lin, S.; et al. Unravelling ultrafast Li ion transport in functionalized metal-organic framework-based battery electrolytes. Nano. Lett. 2023, 23, 7062-9.

30. Raza, A.; Wu, W. Metal-organic frameworks in oral drug delivery. Asian. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 19, 100951.

31. Yang, S. Y.; Sencadas, V.; You, S. S.; et al. Powering implantable and ingestible electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009289.

32. Wang, J.; Chu, J.; Song, J.; Li, Z. The application of impantable sensors in the musculoskeletal system: a review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1270237.

33. Xiao, B.; Cao, F.; Ying, T.; et al. Achieving ultrahigh anodic efficiency via single-phase design of Mg-Zn alloy anode for Mg-air batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 58737-45.

34. Bhaduri, A.; Ha, T. J. Biowaste-derived triboelectric nanogenerators for emerging bioelectronics. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2405666.

35. Lai, Y.; Xie, H.; Li, P.; et al. Ion-migration mechanism: an overall understanding of anionic redox activity in metal oxide cathodes of Li/Na-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2206039.

36. Feng, K.; Li, M.; Liu, W.; et al. Silicon-based anodes for lithium-ion batteries: from fundamentals to practical applications. Small 2018, 14, 1702737.

37. Heubner, C.; Langklotz, U.; Michaelis, A. Theoretical optimization of electrode design parameters of Si based anodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy. Storage. 2018, 15, 181-90.

38. Dou, Y.; Guo, J.; Shao, J.; et al. Bi-functional materials for sulfur cathode and lithium metal anode of lithium-sulfur batteries: status and challenges. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2407304.

39. Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Immunizing lithium metal anodes against dendrite growth using protein molecules to achieve high energy batteries. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5429.

40. Xu, T.; Huang, S.; Min, Y.; Xu, Q. Gelatin network reinforced poly (vinylene carbonate-acrylonitrile) based composite solid electrolyte for all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146409.

41. Paz-González, J. A.; Gochi-Ponce, Y.; Velasco-Santos, C.; et al. Enhancing polylactic acid/carbon fiber-reinforced biomedical composites (PLA/CFRCs) with multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) fillers: a comparative study on reinforcing techniques. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 167.

42. Li, L.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Implantable zinc-oxygen battery for in situ electrical stimulation-promoted neural regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2302997.

43. Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Implantable and bio-compatible Na-O2 battery. Chem 2024, 10, 1885-96.

44. Yao, G.; Kang, L.; Li, C.; et al. A self-powered implantable and bioresorbable electrostimulation device for biofeedback bone fracture healing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021, 118, e2100772118.

45. Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Meng, F.; Cao, Z. Dual storage mechanism of charge adsorption desorption and Faraday redox reaction enables aqueous symmetric supercapacitor with 1.4 V output voltage. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147906.

46. Worsley, E. A.; Margadonna, S.; Bertoncello, P. Application of graphene nanoplatelets in supercapacitor devices: a review of recent developments. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3600.

47. Chernysheva, D. V.; Smirnova, N. V.; Ananikov, V. P. Recent trends in supercapacitor research: sustainability in energy and materials. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301367.

48. Gopi CVV, Alzahmi S, Narayanaswamy V, Raghavendra KVG, Issa B, Obaidat IM. A review on electrode materials of supercapacitors used in wearable bioelectronics and implantable biomedical applications. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 4092-132.

49. Portenkirchner, E. Substantial Na-ion storage at high current rates: redox-pseudocapacitance through sodium oxide formation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4264.

50. Khan B, Haider F, Zhang T, Zahra S. Advances in graphene-transition metal selenides hybrid materials for high-performance supercapacitors: a review. Chem. Rec. 2025, 25, e202500037.

51. Wang, X.; Yu, M.; Kamal, Hadi. M.; et al. An anticoagulant supercapacitor for implantable applications. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10497.

52. Zhu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; et al. Production of a hybrid capacitive storage device via hydrogen gas and carbon electrodes coupling. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2805.

53. Xie, P.; Zhang, Y.; Man, Z.; et al. Wearable, recoverable, and implantable energy storage devices with heterostructure porous COF-5/Ti3C2Tx cathode for high-performance aqueous Zn-ion hybrid capacitor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2421517.

54. Jing, L.; Zhuo, K.; Sun, L.; et al. The mass-balancing between positive and negative electrodes for optimizing energy density of supercapacitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 14369-85.

55. Shao, M.; Sheng, H.; Lin, L.; et al. High-performance biodegradable energy storage devices enabled by heterostructured MoO3-MoS2 composites. Small 2023, 19, e2205529.

56. Gloeb-McDonald, R. G.; Fridman, G. Y. Glucose fuel cells: electricity from blood sugar. IEEE. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 18, 268-80.

57. Ge, J.; Mao, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, S. The fluorescent detection of glucose and lactic acid based on fluorescent iron nanoclusters. Sensors 2024, 24, 3447.

58. Maity, D.; Guha, Ray. P.; Buchmann, P.; Mansouri, M.; Fussenegger, M. Blood-glucose-powered metabolic fuel cell for self-sufficient bioelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2300890.

59. Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; et al. Self-powered enzyme-linked microneedle patch for scar-prevention healing of diabetic wounds. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh1415.

60. Rui, X.; Hua, R.; Ren, D.; et al. In situ polymerization facilitating practical high-safety quasi-solid-state batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2402401.

61. Huddleston, M.; Sun, Y. Biomass valorization via paired electrocatalysis. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402161.

62. Song, Y.; Wang, C. High-power biofuel cells based on three-dimensional reduced graphene oxide/carbon nanotube micro-arrays. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2019, 5, 46.

63. Buaki-Sogó, M.; García-Carmona, L.; Gil-Agustí, M.; Zubizarreta, L.; García-Pellicer, M.; Quijano-López, A. Enzymatic glucose-based bio-batteries: bioenergy to fuel next-generation devices. Top. Curr. Chem. 2020, 378, 49.

64. Wang, Y.; Tong, H.; Ni, S.; et al. Combining hard shell with soft core to enhance enzyme activity and resist external disturbances. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2411196.

65. Welsh, C. L.; Madan, L. K. Chapter Two - Protein tyrosine phosphatase regulation by reactive oxygen species. Adv. Cancer. Res. 2024, 162, 74.

66. Feliciano, A. J.; Soares, E.; Bosman, A. W.; et al. Complementary supramolecular functionalization enhances antifouling surfaces: a ureidopyrimidinone-functionalized phosphorylcholine polymer. ACS. Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 4619-31.

67. Xie, W. J.; Warshel, A. Harnessing generative AI to decode enzyme catalysis and evolution for enhanced engineering. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad331.

68. Chen, N.; Chang, B.; Shi, N.; Yan, W.; Lu, F.; Liu, F. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates immobilization: preparation, characterization, and applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2023, 43, 369-83.

69. Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; et al. Engineering a binding peptide for oriented immobilization and efficient bioelectrocatalytic oxygen reduction of multicopper oxidases. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2025, 17, 2355-64.

70. Cao, L.; Chen, J.; Pang, J.; Qu, H.; Liu, J.; Gao, J. Research progress in enzyme biofuel cells modified using nanomaterials and their implementation as self-powered sensors. Molecules 2024, 29, 257.

71. Khan, M.; Inamuddin,

72. Zhang, Y.; Selvarajan, V.; Shi, K.; Kim, C. J. Fabrication and characterization of glucose-oxidase-trehalase electrode based on nanomaterial-coated carbon paper. RSC. Adv. 2023, 13, 33918-28.

73. Maiti, T. K.; Liu, W.; Niyazi, A.; Squires, A. M.; Chattpoadhyay, S.; Di, Lorenzo. M. Soft-template-based manufacturing of gold nanostructures for energy and sensing applications. Biosensors 2024, 14, 289.

74. Ji, K.; Liang, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Ma, Q.; Su, X. Mxene-based capacitive enzyme-free biofuel cell self-powered sensor for lead ion detection in human plasma. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153598.

75. Wang, X.; Han, F.; Xiao, Z.; et al. 3-D printable living hydrogels as portable bio-energy devices (Adv. Mater. 18/2025). Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2570134.

76. Sode, K.; Yamazaki, T.; Lee, I.; Hanashi, T.; Tsugawa, W. BioCapacitor: a novel principle for biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 76, 20-8.

77. Upadhyay, V.; Boorla, V. S.; Maranas, C. D. Rank-ordering of known enzymes as starting points for re-engineering novel substrate activity using a convolutional neural network. Metab. Eng. 2023, 78, 171-82.

78. Liu, G.; Fan, B.; Qi, Y.; et al. Ultrahigh-current-density tribovoltaic nanogenerators based on hydrogen bond-activated flexible organic semiconductor textiles. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 6771-83.

79. Cui, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z. Implantable self-powered systems for electrical stimulation medical devices. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2412044.

80. Fan, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, H.; Liu, S. Origin and mechanism of piezoelectric and photovoltaic effects in (111) polar orientated NiO films. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2304637.

81. Park, D. S.; Hadad, M.; Riemer, L. M.; et al. Induced giant piezoelectricity in centrosymmetric oxides. Science 2022, 375, 653-7.

82. Xiang, H.; Peng, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Z. L.; Cao, X. Triboelectric nanogenerator for high-entropy energy, self-powered sensors, and popular education. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eads2291.

83. Xiang, Z.; Li, L.; Lu, Z.; et al. High-performance microcone-array flexible piezoelectric acoustic sensor based on multicomponent lead-free perovskite rods. Matter 2023, 6, 554-69.

84. Liu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Qu, X.; et al. A self-powered intracardiac pacemaker in swine model. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 507.

85. Jała, J.; Nowacki, B.; Toroń, B. Piezotronic antimony sulphoiodide/polyvinylidene composite for strain-sensing and energy-harvesting applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 7855.

86. Chen, Q.; Cao, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Hybrid piezoelectric/triboelectric wearable nanogenerator based on stretchable PVDF-PDMS composite films. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 6239-49.

87. Yang, F.; Li, J.; Long, Y.; et al. Wafer-scale heterostructured piezoelectric bio-organic thin films. Science 2021, 373, 337-42.

88. Cheng, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; et al. Boosting the piezoelectric sensitivity of amino acid crystals by mechanical annealing for the engineering of fully degradable force sensors. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2207269.

89. Sun, Q.; Liang, F.; Ren, G.; et al. Density-of-states matching-induced ultrahigh current density and high-humidity resistance in a simply structured triboelectric nanogenerator. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2210915.

90. Liu, Q.; Xue, Y.; He, J.; et al. Highly moisture-resistant flexible thin-film-based triboelectric nanogenerator for environmental energy harvesting and self-powered tactile sensing. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 38269-82.

91. Ding, D.; Wu, Q.; Li, Q.; et al. Novel thermoelectric fabric structure with switched thermal gradient direction toward wearable in-plane thermoelectric generators. Small 2024, 20, e2306830.

92. Liu, J. Z.; Jiang, W.; Zhuo, S.; et al. Large-area radiation-modulated thermoelectric fabrics for high-performance thermal management and electricity generation. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr2158.

93. Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Deng, L.; et al. Flexible thermoelectric generator and energy management electronics powered by body heat. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 106.

94. Li, X.; Li, R.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. L.; Wei, D. Triboiontronics with temporal control of electrical double layer formation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6182.

95. Yan, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Autonomous, moisture-driven flexible electrogenerative dressing for enhanced wound healing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2418074.

96. Rayegani, A.; Saberian, M.; Delshad, Z.; et al. Recent advances in self-powered wearable sensors based on piezoelectric and triboelectric nanogenerators. Biosensors 2022, 13, 37.

97. Delgado-Alvarado, E.; Martínez-Castillo, J.; Zamora-Peredo, L.; et al. Triboelectric and piezoelectric nanogenerators for self-powered healthcare monitoring devices: operating principles, challenges, and perspectives. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4403.

98. Omi, A. I.; Jiang, A.; Chatterjee, B. Efficient inductive link design: a systematic method for optimum biomedical wireless power transfer in area-constrained implants. IEEE. Trans. Biomed. Circuits. Syst. 2025, 19, 300-16.

99. Sheng, H.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Q.; et al. A soft implantable energy supply system that integrates wireless charging and biodegradable Zn-ion hybrid supercapacitors. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh8083.

100. Yu, Z.; Chen, J. C.; Alrashdan, F. T.; et al. MagNI: a magnetoelectrically powered and controlled wireless neurostimulating implant. IEEE. Trans. Biomed. Circuits. Syst. 2020, 14, 1244-55.

101. Ullah, M. A.; Keshavarz, R.; Abolhasan, M.; Lipman, J.; Esselle, K. P.; Shariati, N. A review on antenna technologies for ambient RF energy harvesting and wireless power transfer: designs, challenges and applications. IEEE. Access. 2022, 10, 17231-67.

102. Abdolrazzaghi, M.; Genov, R.; Eleftheriades, G. V. Subwavelength-scale focused wireless powering of implantable medical devices by superoscillations. IEEE. Trans. Microw. Theory. Technol. 2025, 73, 2101-10.

103. Hinchet, R.; Yoon, H. J.; Ryu, H.; et al. Transcutaneous ultrasound energy harvesting using capacitive triboelectric technology. Science 2019, 365, 491-4.

104. Zhu, K.; Ma, J.; Qi, X.; et al. Enhancement of ultrasonic transducer bandwidth by acoustic impedance gradient matching layer. Sensors 2022, 22, 8025.

105. Hou, J. F.; Nayeem, M. O. G.; Caplan, K. A.; et al. An implantable piezoelectric ultrasound stimulator (ImPULS) for deep brain activation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4601.