Round-the-clock photocatalytic hydrogen production enabled by an S-scheme Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy)/CdS heterojunction

Abstract

Round-the-clock photocatalytic hydrogen production is essential for overcoming the intermittency of solar energy and achieving continuous solar-to-hydrogen conversion. However, the development of efficient round-the-clock photocatalysts remains a considerable challenge due to limited light availability and inefficient charge utilization in the dark. In this work, a long-afterglow-based S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst, Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy)/CdS (referred to as SMSED/CdS), is constructed via a ball-milling strategy. The luminescence from Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy) (referred to as SMSED) is efficiently captured by CdS, thus serving as a built-in light source to drive dark catalytic reactions. Meanwhile, the unique electron transfer pathway in SMSED provides sufficiently long-lived electrons for the SMSED/CdS system. The S-scheme heterojunction formed between SMSED and CdS directs the photogenerated charge transfer, while maintaining the strong redox capability of SMSED/CdS. Consequently, the SMSED/CdS exhibits hydrogen production of 45.20 mmol g-1 under ultraviolet-visible light within 1 h and a dark activity of 4.37 mmol g-1 sustained over 3 h. The corresponding mechanism was comprehensively studied via analysis of physicochemical properties, band structure, ex-situ and in-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and density functional theory calculations. This study provides a significant breakthrough in developing round-the-clock photocatalysts.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Photocatalytic water splitting is a renewable energy production method with great potential[1,2]. The process has recently been significantly improved[3-5]. However, the heavy reliance on sunlight greatly limits its practical application on cloudy days or at night[6,7]. To address this issue, advancements in photocatalytic technology leverage long-afterglow phosphors to sustain photon utilization during dark reaction phases, aiming to enhance photocatalytic performance and facilitate the commercialization of the technology, particularly for round-the-clock hydrogen production.

Long-afterglow materials demonstrate significant potential for application in photocatalysis due to their excellent optical properties and good chemical stability[8,9]. Suitable luminescent wavelengths enable these materials to effectively absorb light and excite electrons, thereby driving photocatalytic reactions[10,11]. Taking Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy) (referred to as SMSED) as an example, it not only possesses the aforementioned advantages but also features appropriate afterglow brightness and duration, as well as excellent hydrolysis resistance[12,13], making it an important candidate for photocatalytic water splitting. In the pioneering study, Cui et al.[14] reported the application of Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+ in methanol photocatalytic reforming for round-the-clock hydrogen production, which resulted in an efficiency of converting solar energy to hydrogen of 5.18%. Pei et al.[15] utilized SMSED long-afterglow phosphor with rich oxygen vacancy for round-the-clock photocatalysis, and the selectivity of CO2 to CO was nearly 100%.

The luminescence and long afterglow mechanism of SMSED primarily involve the energy level transitions and trapping effects of Eu2+ and Dy3+[16,17]. Under light irradiation, the ground-state electrons (4f7) of Eu2+ absorb photon energy and transition to the excited state (4f65d1). Some of the excited electrons return to the 4f7 level via radiative transition, generating fluorescence emission, while others enter the conduction band (CB) and are captured by Dy3+ defect energy levels, forming trap states[18]. After the excitation source is removed, the trapped electrons can be thermally released back to the excited state of Eu2+, followed by radiative transitions to the ground state, generating long afterglow emission lasting for 4-5 h[19]. Notably, SMSED transmits blue fluorescence between 420 and 510 nm, which matches the absorption spectrum of semiconductors with a bandgap of 2.4-2.9 eV. Take the CdS semiconductor as an example [Supplementary Figure 1]: when the absorption spectrum of CdS semiconductor matches the luminescence spectrum of SMSED, SMSED is able to function as a built-in light source in the dark conditions, supplying energy for photocatalytic reactions without external illumination. Furthermore, the long afterglow properties of SMSED ensure the continuous operation of dark photocatalysis. Therefore, composite systems based on SMSED long-afterglow materials hold great promise for achieving round-the-clock photocatalysis.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have demonstrated the excellent photocatalytic performance of SMSED/semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts[20-28]. Examples include type Ⅱ heterojunctions (Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu2+,Dy3+)/g-C3N4, SMSED@CdS)[20,21], Z-scheme heterojunctions (Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+/Ag3PO4, Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+)/COF, BiFeO3/Ag/Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu2+,Dy3+)/Ag, Sr2MgSi2O7: (Eu2+,Dy3+)/g-C3N4@Ag)[22-25], S-scheme heterojunctions (ZnIn2S4/Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu2+,Dy3+), Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu2+,Dy3+)/ZnIn2S4/UiO-66-NH2[26,27], and ZnO/Pg-C3N4/Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu2+,Dy3+)[28]. The good photocatalytic performance of SMSED/semiconductors can be attributed to the following factors: (1) The long afterglow properties of SMSED provide continuous light in the dark environments, allowing semiconductors to sustain photocatalytic reactions even without external illumination; (2) The synergistic effect between SMSED and semiconductors broadens the spectral response range, which boosts the harvesting efficiency of photoinduced charge; (3) The constructed heterojunction effectively promotes charge separation and transfer, further enhancing photocatalytic activity. Notably, the long afterglow property of SMSED, combined with the advantages of the S-scheme heterojunction in promoting charge separation while maximizing the redox capacity[29,30], is the key to achieving round-the-clock photocatalysis.

In our previous research, a type II SMSED@CdS heterojunction was constructed via an in-situ solvothermal method[20]. However, the type-II mechanism led to a loss of redox potential. To overcome this issue, we modified the band structures of CdS and SMSED via ball milling, and further constructed an S-scheme SMSED/CdS heterojunction to achieve continuous hydrogen generation. The electron transfer in the SMSED/CdS system follows an S-scheme mechanism, which simultaneously facilitates charge separation dynamics and maximizes the redox capability. As a photocatalyst, SMSED provides a unique charge carrier migration pathway that generates abundant long-lived charges. After turning off the external light source, SMSED acts as an afterglow excitation source, activating CdS for sustained hydrogen production in the dark. The S-scheme SMSED/CdS heterojunction achieved a photocatalytic hydrogen production of

EXPERIMENTAL

Photocatalysts synthesis

First, 2.90 g of SrCO3, 0.40 g of MgO, 1.20 g of SiO2, 0.01 g of Eu2O3, 0.04 g of Dy2O3, 0.05 g of H3BO3, and 5.50 g of Nb2O5 are heated to 1,150 °C in the H2/Ar (10/90, v/v) gas flow and maintained for 2 h. The SMSED is obtained after cooling. Next, 0.18 g of CdCl2·2.5H2O is dissolved in 60 mL of diethylenetriamine (DETA), followed by the addition of 0.16 g of sulfur powder. Following solvothermal synthesis in a lined autoclave

Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were carried out on a D8 ADVANCE instrument (BRUKER AXS GmbH, Germany). Morphology features were collected using Quanta200 and JEM-2100 microscopes (JEOL, Japan), respectively. Ex/in situ irradiated XPS was conducted with an Escalab 250Xi spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded on an FLS980 spectrofluorometer (Edinburgh Instruments, UK). UV-visible (UV-vis) diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) were collected on a UV-2600 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan)[32].

Photocatalytic experiment

The photocatalytic experiment was conducted on a Labsolar-6A instrument (Beijing Perfectlight, China). A Xenon (Xe) lamp (300 W, full spectrum, 100 mW cm-2) served as the light source. The reaction solution was degassed before irradiation. In a typical process, 10 mg of photocatalyst was dispersed in 40 mL of

Electrochemical tests

The photocurrent response was measured using a potentiostat (CHI 660D, CH Instruments, USA). This measurement system was composed of a three-electrode configuration. The working electrode was a photocatalyst film. The area of a working electrode was 1 cm2. The reference electrode was a calomel electrode, and the counter electrode was a Pt wire. A 300 W Xe lamp served as the light source[34].

DFT calculation

All calculations were conducted within the framework of DFT using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method, as implemented in the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP). The Kohn-Sham one-electron states were represented using a plane-wave basis set with a cutoff energy of 450 eV. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional was utilized for the exchange-correlation energy. A vacuum region of 15 Å was included to separate the systems and examine the surface reaction mechanisms. The Brillouin zone was sampled using the Monkhorst-Pack scheme with a k-point grid of 2 × 3 × 1 for structural optimizations. During the geometry optimizations, the atomic forces were relaxed until the maximum force was less than 0.02 eV/Å, with a total energy convergence criterion of 1×10-4 eV[35-37].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

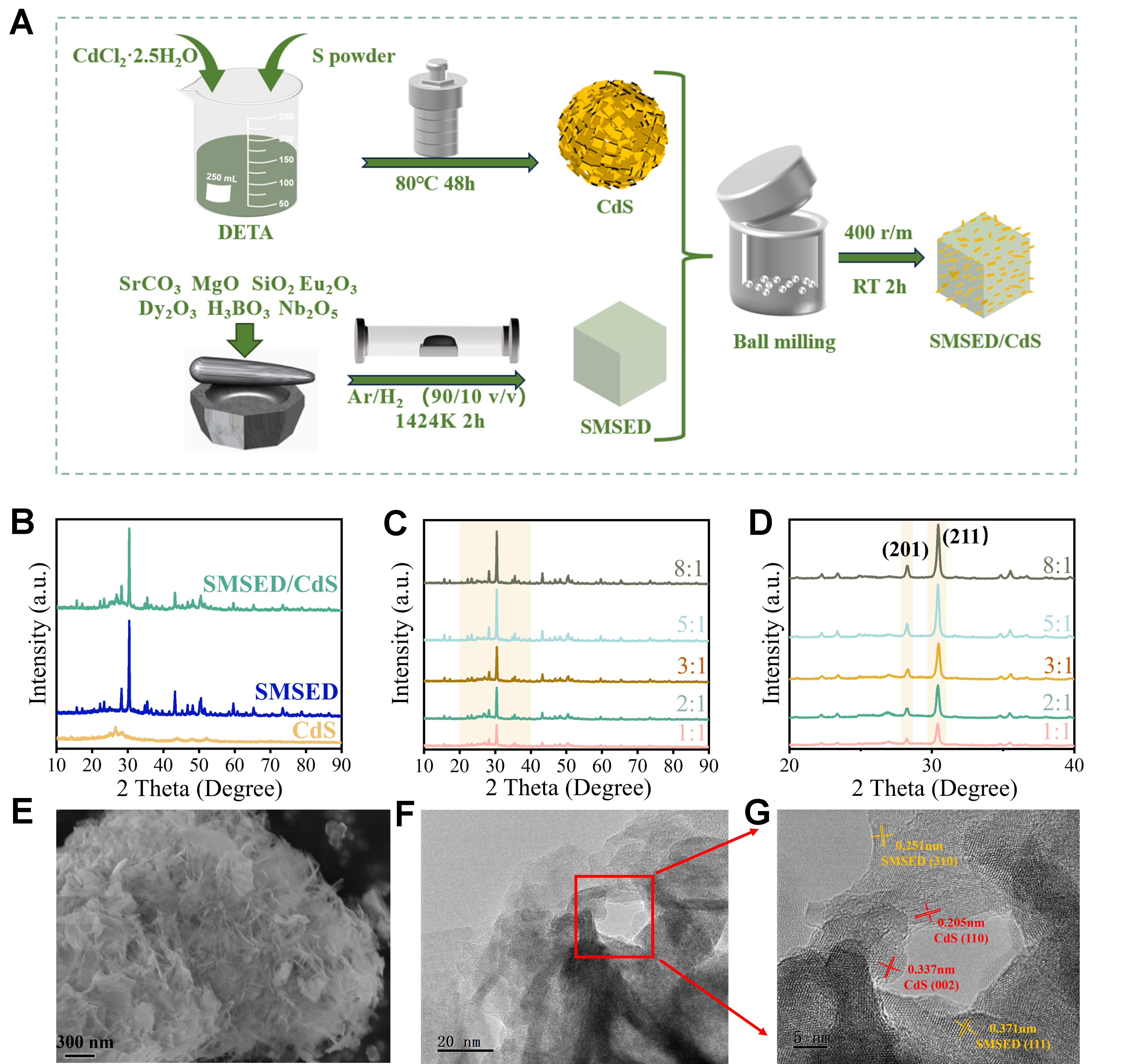

The SMSED/CdS is synthesized by a multi-step process, as shown in Figure 1A. First, CdS is synthesized via a solvothermal method. Second, SMSED is synthesized under a high-temperature solid-state condition. Finally, SMSED and CdS are combined using a ball-milling method to form the SMSED/CdS composite. Five distinct composites were synthesized by modulating the SMSED: CdS weight ratio (1:1, 2:1, 3:1, 5:1, 8:1). The SMSED/CdS (2:1) sample exhibits the highest photocatalytic activity under UV-vis light irradiation, so it is designated as the standard composite (SMSED/CdS) for subsequent studies unless stated otherwise.

Figure 1. (A) Schematic diagram of SMSED/CdS preparation; (B) XRD spectra of pristine CdS, SMSED/CdS, and SMSED; (C) Composition-dependent XRD profiles corresponding to SMSED: CdS mass ratios of 1:1, 2:1, 3:1, 5:1, and 8:1; (D) Enlarged XRD patterns of Figure 1B; (E) FESEM image of SMSED/CdS; (F) TEM micrograph of SMSED/CdS; (G) HRTEM micrograph of the red box in Figure 1F. SMSED: Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy); XRD: X-ray diffraction; DETA: diethylenetriamine; FESEM: field emission scanning electron microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; HRTEM: high-resolution transmission electron microscopy.

In Figure 1B, CdS exhibits a hexagonal phase structure, and the (002) and (101) planes are identified at 26.7° and 28.5°, respectively. This is indexed to Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) card no. 41-1049 [Supplementary Figure 2]. SMSED shows a tetragonal phase structure, and the highest diffraction peaks at 30.4°, 28.1°, and 43.2°, corresponding to the (211), (201), and (212) planes, respectively. This corresponds to the JCPDS card no. 75-1736 [Supplementary Figure 2]. SMSED/CdS shows coexisting SMSED and CdS. In addition, as the mass ratio of SMSED to CdS increases, the intensities of the (211) and (201) planes of SMSED increase, while the intensity of the (101) plane of CdS decreases [Figure 1C and D].

Besides, Supplementary Figure 3 shows the Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of CdS, SMSED/CdS, and SMSED. Broad absorption bands spanning 1,249-1,705 and 2,743-3,622 cm-1 regions are attributed to surface-adsorbed hydroxyl groups[38,39]. In the SMSED spectrum, characteristic vibrational modes appear in three distinct regions: Mg-O bond vibrations at 400-525 cm-1[40], Si-O stretching modes between 526-691 cm-1, and Si-O-Si stretching vibrations spanning 738-1,083 cm-1[41], respectively. For SMSED/CdS, peaks corresponding to SMSED and CdS are observed, with no new functional groups observed. In addition, the Raman spectra of CdS, SMSED, and SMSED/CdS are presented in Supplementary Figure 4. The bands at 901, 652, and 315 cm-1 are attributed to the symmetric stretching mode of SiO3 groups, Si-O-Si bridges and SiO3 groups[42,43]. The intense characteristic peak at ~300 cm-1 corresponds to the fundamental first-order longitudinal optical (1LO) phonon mode of the Cd-S lattice, while the weak characteristic peak at ~600 cm-1 is the second-order overtone (2LO) mode[44]. In the spectra of SMSED/CdS, the characteristic vibration peaks of both CdS and SMSED were observed simultaneously, along with a slight shift in the characteristic peaks. These results can further verify the structural integrity and interfacial interaction of the composite system.

The morphologies of CdS, SMSED/CdS, and SMSED were studied by Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) measurements. SMSED exhibits irregular block-like morphology [Supplementary Figure 5A]. CdS displays a porous structure assembled from sheets [Supplementary Figure 6A], which is mainly influenced by some factors, such as the solvent DETA, precursor solubility, reaction kinetics, and surface energy. CdCl2·2.5H2O and sulfur powders can be fully dissolved in DETA, providing Cd2+ and S2- ions, which facilitate the uniform nucleation of CdS. DETA acts as both a chelating agent and a structure-directing agent, regulating the growth mode of CdS and inhibiting isotropic growth, thereby promoting the formation of two-dimensional sheets. Additionally, the self-assembly of sheets may result from van der Waals forces, surface tension, and low surface energy effects, leading to the spontaneous stacking of sheets into a three-dimensional porous network. Besides, solvent evaporation or template effects may further enhance the formation of the porous structure.

However, the morphology of SMSED/CdS differs from CdS and SMSED [Figure 1E, Supplementary Figures 5B and 6B], which is primarily due to the enhancement of mechanical forces caused by ball-milling. The layered structure of CdS is further delaminated under shear and impact forces, making it easier to attach to the SMSED surface and resulting in uniform loading. Moreover, the ball-milling process improves the interfacial contact between SMSED and CdS, strengthens their bonding, and promotes the reorientation and distribution of CdS nanosheets, ultimately leading to a uniform coverage of CdS layered structures on the surface of SMSED. In addition, we also studied the effects of ball milling on SMSED and CdS. Supplementary Figures 5-9 indicate that the ball-milling method only changed their morphology without altering the crystal structure and optical properties. Figure 1F and G presents the TEM and High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM) images of SMSED/CdS. HRTEM in Figure 1G shows the interplanar distances of 0.251 and 0.371 nm indexing to the (310) and (111) planes in SMSED, as well as 0.205 and

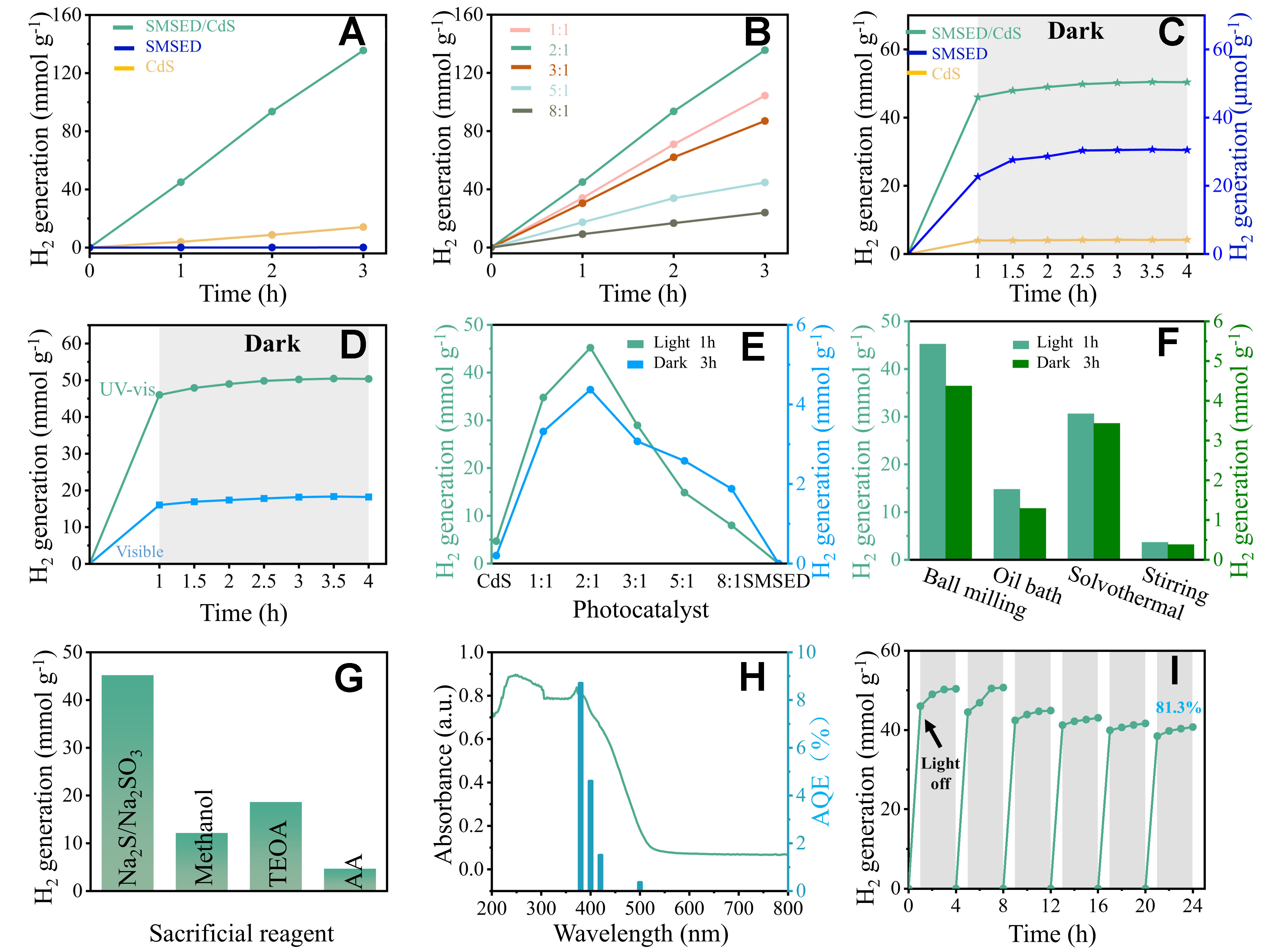

Hydrogen generation performance was measured using a Labsolar-6A instrument [Supplementary Figure 14]. As shown in Figure 2A, SMSED demonstrates insignificant activity after 3 h of UV-vis light irradiation. This is due to the rapid combination of photoinduced charge carriers in SMSED. For CdS, the hydrogen production reaches 14.08 mmol g-1 during the first 3 h, corresponding to a hydrogen production of

Figure 2. (A) H2 production activity under UV-vis light irradiation for CdS, SMSED/CdS, and SMSED (B) Mass ratio-dependent activity under UV-vis irradiation; (C) Dark catalytic H2 generation (after 1 h light pre-treatment); (D) H2 generation of SMSED/CdS under light irradiation/dark; (E) Relationship between photocatalytic and dark catalytic activities of different samples; (F) H2 generation of SMSED/CdS prepared by different methods; (G) H2 generation of SMSED/CdS measured in different sacrificial reagent systems; (H) AQE of SMSED/CdS related to light absorption; (I) Cyclic stability test. Each cycle consisting of 1 h of light exposure and 3 h of darkness, repeated for 6 cycles. SMSED: Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy); UV-vis: ultraviolet-visible; AQE: apparent quantum efficiency; TEOA: triethanolamine; AA: ascorbic acid.

To study the role of SMSED in photocatalytic reactions, the SMSED/CdS was illuminated under UV-vis light for 1 h, followed by evaluating catalytic hydrogen production in the dark. In Figure 2C, CdS has satisfactory photocatalytic activity, but it is inactive in the dark. This indicates that the hydrogen production of CdS is highly dependent on external light. In comparison, the hydrogen production of SMSED under both light and dark conditions is negligible. This is mainly because the photogenerated electron-hole pairs primarily contribute to the fluorescence process [Supplementary Figure 16] rather than the photocatalytic process. SMSED/CdS demonstrated hydrogen generation activity in light and dark environments. Interestingly, the hydrogen production of SMSED/CdS is 4.37 mmol g-1 during the dark environment for 3 h. For SMSED/CdS [Figure 2D], visible-light-driven hydrogen generation rate is 13.37 mmol g-1 h-1 and the dark catalytic rate is 0.71 mmol g-1 h-1.

The mass ratio will influence the photogenerated charge transfer efficiency, energy storage capacity, and hydrogen release rate during the dark reaction. Therefore, we observed the changing trend of photocatalytic and dark catalytic performance at different SMSED/CdS ratios. In Figure 2E, CdS shows high photocatalytic activity. A moderate amount of SMSED (1:1, and 2:1) is helpful to construct effective heterojunctions to enhance photocatalytic performance. Excessive SMSED (> 3:1) results in reduced light absorption capacity [Supplementary Figure 17], hindered charge-carrier separation and transfer [Supplementary Figures 18-20], and increased overpotential [Supplementary Figure 21], ultimately leading to a decrease in photocatalytic performance. SMSED has no catalytic activity, whereas CdS exhibits only photocatalytic activity. Only SMSED/CdS has both photocatalytic and dark catalytic activities. Because photocatalysis and continuous luminescence are competing processes, round-the-clock photocatalysis must balance them. Since SMSED mainly functions as a persistent luminescent material, excessive SMSED will reduce the overall hydrogen production due to its poor photocatalytic activity. Therefore, considering both photocatalytic and dark catalytic performance, SMSED/CdS (2:1) performs best for round-the-clock hydrogen generation.

Additionally, when maintaining a 2:1 mass ratio of SMSED to CdS, SMSED/CdS was prepared by in situ solvothermal, oil-bath, and mechanical-stirring methods. In Figure 2F, the order of photocatalytic hydrogen production activity of SMSED/CdS prepared by different methods is: ball milling (light: 45.20 mmol g-1 h-1; dark: 4.37 mmol g-1) > solvothermal method (light: 30.59 mmol g-1 h-1; dark: 3.43 mmol g-1) > oil bath method (light: 14.76 mmol g-1; dark: 1.29 mmol g-1) > mechanical stirring method (light: 3.64 mmol g-1 h-1; dark:

Figure 2G shows the photocatalytic activity of SMSED/CdS measured in varied sacrificial conditions (TEOA, methanol, AA, and Na2S/Na2SO3). The photocatalytic activity measured in the Na2S/Na2SO3 system is higher than that in the other three systems. This is mainly because Na2S/Na2SO3 not only effectively scavenges photogenerated holes and donates electrons but also prevents the oxidation of CdS[45]. The apparent quantum efficiency (AQE) of SMSED/CdS decreases with the reduction of light absorption [Figure 2H]. The maximum AQE of 8.7% at 380 nm, exceeding that of CdS alone [Supplementary Table 1]. In Figure 2I, the SMSED/CdS composite maintained 81.3% of its initial hydrogen production performance after six light/dark cycles, demonstrating excellent round-the-clock photocatalytic stability. We also obtained the XRD and FESEM data of SMSED/CdS after photocatalytic reaction [Supplementary Figures 22 and 23], indicating that the phase and morphology remain unchanged. These findings demonstrate that the SMSED/CdS possesses good phase structural and chemical stability.

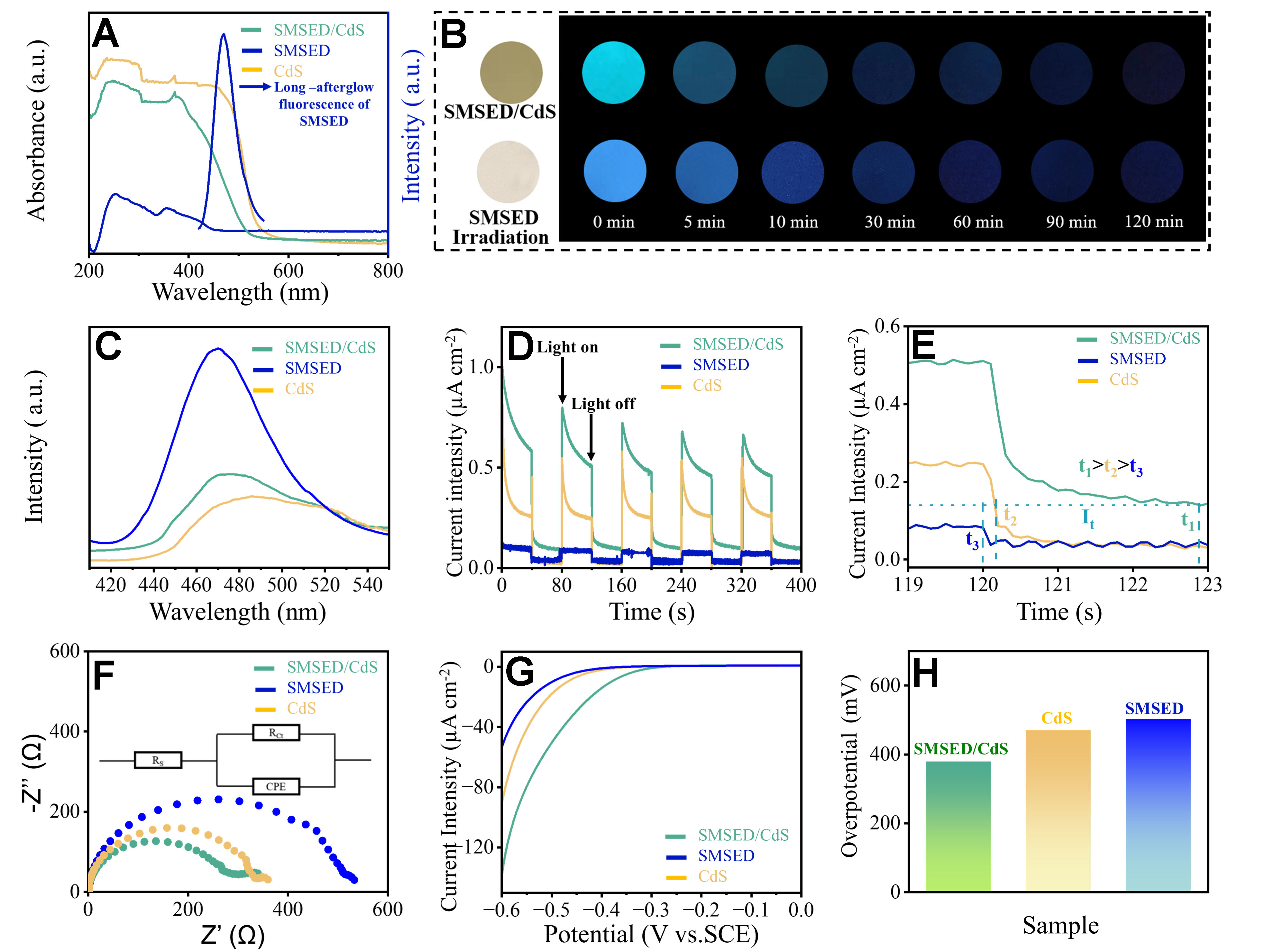

The enhancement mechanism of photocatalytic performance was investigated by analyzing photophysical and electrochemical properties. In Figure 3A, SMSED/CdS exhibits an absorption edge of 540 nm. Compared to CdS, SMSED/CdS has a narrower absorption edge and lower absorption intensity. However, compared to SMSED, the absorption edge of SMSED/CdS is extended and the absorption intensity is significantly enhanced. In addition, SMSED exhibits strong fluorescence emission in the range of

Figure 3. (A) UV-vis DRS of CdS, SMSED, and SMSED/CdS, as well as the long-afterglow spectra of SMSED under 380 nm excitation; (B) Photographs of SMSED/CdS and SMSED under light irradiation (left) and in the dark (right, black background); (C) Photoluminescence spectra; (D) Transient photocurrent responses obtained from chopped I-t curves; (E) Charge lifetime analysis derived from photocurrent decay kinetics, where t1 (SMSED/CdS), t2 (CdS), and t3 (SMSED) represent the time required to reach current density It after light interruption; (F) EIS and the equivalent Randle circuit; CPE accounts for the constant phase element, Rct is the charge transfer impedance at solid/liquid interface, and Rs is the bulk solution resistance; (G) Polarization curves; (H) Overpotential of CdS, SMSED, and SMSED/CdS. SMSED: Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy); UV-vis: ultraviolet-visible; DRS: diffuse reflectance spectra; EIS: electrochemical impedance spectroscopy; CPE: constant phase element; SCE: saturated calomel electrode.

To observe the long-afterglow phenomenon, SMSED/CdS and SMSED were first irradiated by an external light source and then continued to be placed in the dark [Figure 3B]. At the beginning, both SMSED/CdS and SMSED emit strong blue light. As the dark period extends, the blue light gradually weakens. After 2 h, a faint blue light is still visible. This indicates that SMSED/CdS exhibits long-afterglow properties similar to those of SMSED, which is essential for designing continuous photocatalysis under light/dark conditions. Together with the results from Figure 3A, it suggests that SMSED/CdS is suitable for a round-the-clock photocatalysis.

Figure 3C shows PL spectra. The ranking of PL intensity is SMSED > SMSED/CdS > CdS. A lower PL intensity often implies high charge separation rate[46]. CdS shows relatively low PL intensity due to its strong charge-separation capability. SMSED exhibits a high PL intensity due to its pronounced luminescent properties. For SMSED/CdS, incorporation of CdS effectively enhances charge separation in SMSED, resulting in a PL intensity lower than that of SMSED but higher than that of CdS.

Figure 3D shows the photocurrent response of CdS, SMSED, and SMSED/CdS. The photocurrent densities follow the order: SMSED/CdS > CdS > SMSED. This indicates that SMSED/CdS exhibits the best photoresponse, due to enhanced charge separation and transfer enabled by the heterojunction. The attenuation of photocurrent under illumination originates from the charge recombination or surface relaxation processes; whereas a sustained afterglow photocurrent is still shown in the SMSED/CdS system after the light source is turned off. This is attributed to CdS absorbing the long-afterglow fluorescence emitted by SMSED, which provides additional photon energy input for dark reactions, thereby extending the catalytic activity. Additionally, the charge lifetime can be analyzed based on the photocurrent response[47-49]. According to the photoresponse decay rate [Figure 3E], the decay of SMSED/CdS is the slowest, followed by CdS, while SMSED exhibits the fastest decay. A slower decay rate indicates a more efficient separation and transfer within the photocatalysts[50]. Figure 3E also presents the time required for the photocurrent density to decay from its initial value to time t, following the order of t1 (2.92 s) > t2 (0.25 s) > t3 (0.04 s). Therefore, the SMSED/CdS system exhibits the longest charge lifetime.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectra are illustrated in Figure 3F. The SMSED/CdS exhibits the smallest arc radius, indicating the lowest interfacial resistance and the highest charge-transfer efficiency. Figure 3G and H shows the polarization curves and overpotential values, respectively. SMSED/CdS shows a significantly lower overpotential compared with SMSED and CdS. SMSED/CdS requires only 379 mV of overpotential to achieve a current density of 10 μA cm-2, outperforming SMSED (471 mV) and CdS

The mass ratios of SMSED to CdS (8:1, 5:1, 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1) have an impact on the photophysical, electrochemical properties, and overpotential, as shown in Supplementary Figures 17-21. When the mass ratio is 2:1, SMSED/CdS exhibits the best light absorption [Supplementary Figure 17], the lowest PL intensity [Supplementary Figure 18], minimal EIS [Supplementary Figure 19 and Supplementary Table 2], higher photocurrent density [Supplementary Figure 20], and moderate overpotential [Supplementary Figure 21 and Supplementary Table 3]. This proves that SMSED/CdS has the most efficient charge separation and the fastest interfacial charge transfer, facilitating the synergy between the photo and dark reactions. In addition, based on the EIS Bode phase plots [Supplementary Figure 24], the carrier lifetime (τe) can be calculated using[52]:

where ωmax is the maximum angular frequency and fmax is the peak frequency at the maximum phase. The calculated τe values of CdS, SMSED, and SMSED/CdS are 0.19 ms, 0.23 and 0.62 ms [Supplementary Table 4], respectively. This suggests that the synergistic effect of SMSED and CdS effectively prolongs the lifetime of photo-generated electrons. Therefore, the superior photocatalytic activity originates from the synergistic effect of SMSED and CdS, especially the improved charge separation and transfer brought about by heterojunctions.

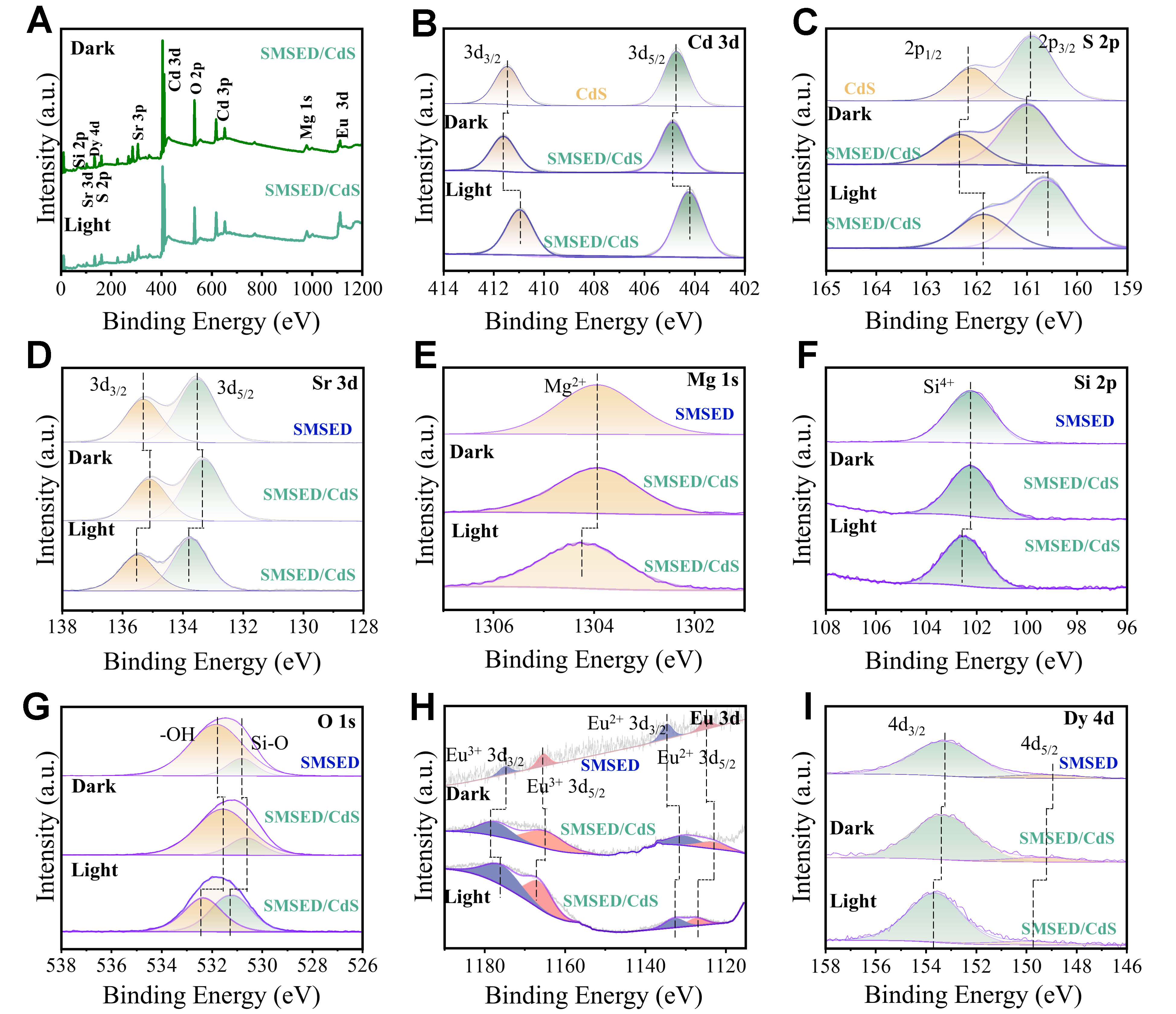

XPS spectra are shown in Figure 4. In Figure 4A, the full spectra reveal the existence of O, Si, Mg, Sr, S, and Cd elements. However, due to the low content of Eu and Dy in SMSED, the corresponding peaks are not prominent. Figure 4B and C shows the chemical states of S and Cd, including Cd 3d3/2 (411.5 eV) and Cd 3d5/2 (404.7 eV), S 2p1/2 (162.2 eV), and S 2p3/2 (160.9 eV), respectively[53-56]. In Figure 4D-F, the peaks are observed at Sr 3d3/2 (135.3eV), Sr 3d5/2 (133.2 eV), Mg 1s (1303.9 eV), and Si 2p (102.2 eV) in SMSED/CdS[57-59]. Figure 4G shows surface hydroxyl (531.8 eV) and Si-O (530.8 eV) in pristine SMSED[60,61]. In Figure 4H, the Eu 3d spectrum resolves four components at 1,124.9 eV (Eu2+ 3d5/2), 1,134.7 eV (Eu3+ 3d5/2), 1,165.5 eV (Eu2+ 3d3/2), and 1,174.9 eV (Eu3+ 3d3/2)[62,63]. In Figure 4I, the Dy 4d spectrum shows two peaks at 149.3 eV (Dy 4d5/2) and 153.3 (Dy 4d5/2) eV[64,65]. The excitation of Eu2+ 4f electrons to the 5d level, driven by thermal energy, leads to their transfer to the CB of Sr2MgSi2O7, oxidizing Eu2+ to Eu3+[66].

Figure 4. Ex-situ/in-situ irradiated XPS characterization. (A) Full spectra; (B and C) Cd 3d and S 2p, respectively; (D) Sr 3d; (E) Mg 1s; (F) Si 2p; (G) O 1s; (H) Eu 3d; (I) Dy 4d. SMSED: Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy); XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

A reduction in binding energy correlates with enhanced electron cloud density, while an increase in binding energy corresponds to a decrease in electron density[67]. In Figure 4, the electron density of CdS decreases while that of SMSED increases, indicating that electrons transfer from CdS to SMSED under dark conditions. Furthermore, under light illumination, the electron density of key elements (O 1s, Si 2p, Sr 3d, and Mg 1s) in the SMSED/CdS system decreases compared with those under dark conditions, while the electron density of the key elements (Cd 3d and S 2p) increases compared to those under dark conditions. This suggests that under illumination, photoinduced electrons migrate from SMSED toward CdS. Therefore, the ex-situ/in-situ irradiated XPS results provide strong evidence for the charge transfer pathway at the SMSED/CdS interface, further confirming that the electron migration from SMSED to CdS follows the S-scheme mechanism.

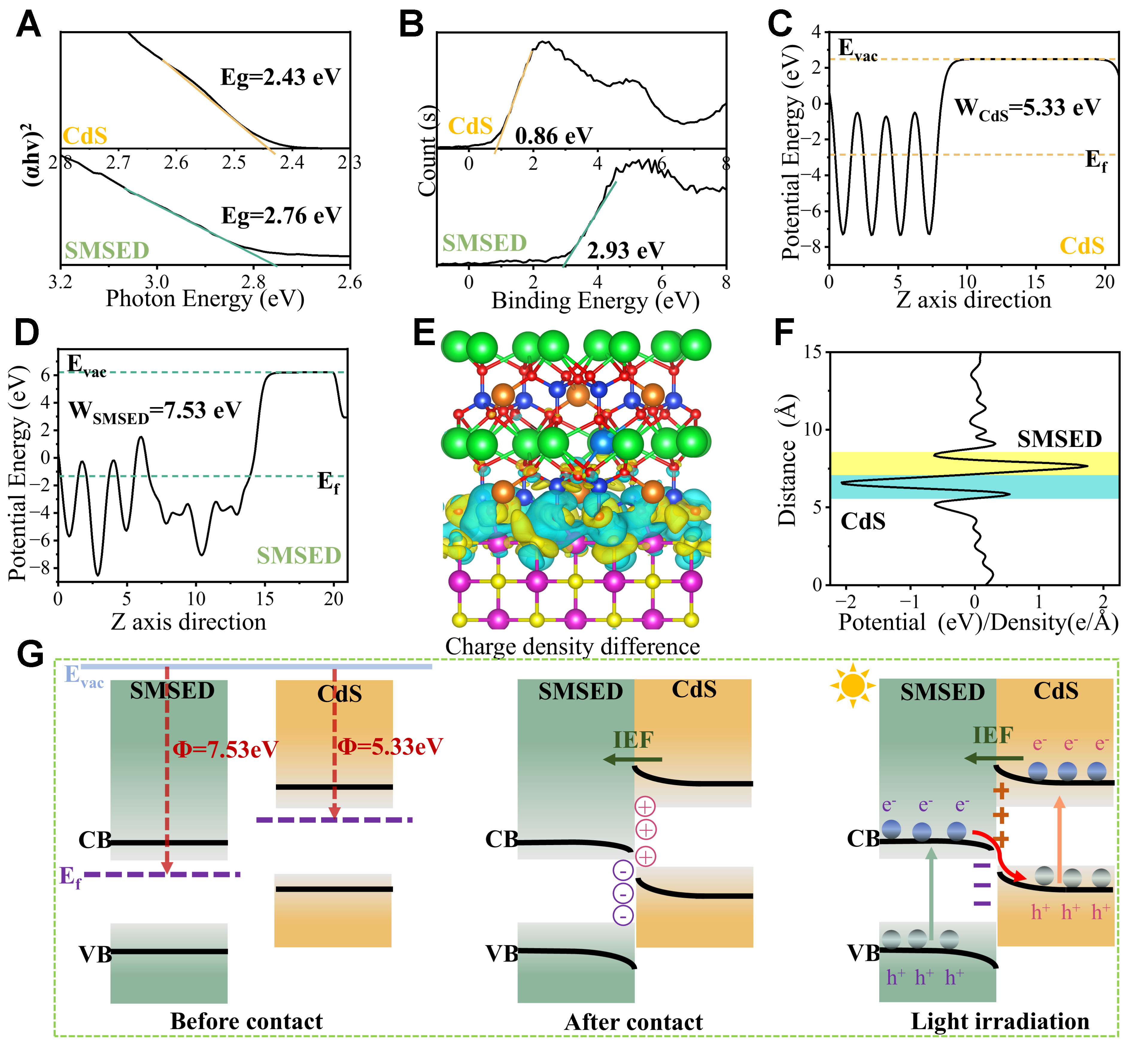

To determine the bandgap value (Eg) of photocatalysts, a Kubelka-Munk function versus incident photon energy plot was constructed. Figure 5A shows the Eg values of SMSED (2.76 eV) and CdS (2.43 eV). Figure 5B displays the valence band (VB) positions of SMSED (2.93 eV) and CdS (0.86 eV), which are quantified via VB-XPS analysis. Then, the maximum valence band (EVB, NHE) is calculated using[68]:

Figure 5. Proposed S-scheme heterojunction mechanism. (A) Bandgap plots; (B) VB-XPS spectra; (C and D) Work functions; (E) Differential charge density of SMSED/CdS. Cd, Dy, Eu, Si, O, Mg, Sr, and S atoms are denoted by pink, purple, light blue, blue, red, orange, green, and yellow balls, respectively. Electron-deficient zones are denoted by cyan, while electron-rich regions are marked in yellow; (F) Distribution of projected planar charge density difference aligned with the Z-direction; (G) Charge transfer mechanism. Evac: Vacuum level; Ef: fermi level; IEF: internal electric field; Φ: work function; SMSED: Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy); VB: valence band; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; CB: conduction band; Eg: bandgap value; WCdS: work function of CdS.

Here, the instrument work function is 4.20 eV, so the EVB, NHE values are determined as 2.69 eV for SMSED and 0.62 eV for CdS. Then, the ECB of the photocatalysts was calculated according to[69]:

where Eg, EVB, and ECB are the band gap, valence band position, and CB position, respectively. The ECB values for SMSED and CdS are measured at -0.07 eV and -1.81 eV, respectively. Notably, the 2.69 eV in SMSED corresponds to the intermediate energy level formed by the 4f7 ground state of the Eu2+ dopant. For the host material Sr2MgSi2O7, the experimental forbidden bandgap is 6.67 eV and the intrinsic valence band of

Furthermore, the work function (Φ) and differential charge distribution were used to quantify the interfacial carrier dynamics of the heterojunction. Φ is evaluated using[73]:

where Ef and Evac are the electrostatic potential of the Fermi level and vacuum level, respectively. Figure 5C and D reveals distinct work functions for SMSED (7.53 eV) and CdS (5.33 eV). CdS exhibits a higher Ef and a lower Φ relative to SMSED. Upon contact, electrons are transferred from CdS to SMSED at the interface, causing the Ef of SMSED to shift downward and that of CdS to shift upward until equilibrium is reached. This causes CdS to become positively charged and SMSED to become negatively charged. In Figure 5E, the differential charge distribution for the SMSED/CdS heterojunction shows that electrons are accumulated on SMSED and depleted on CdS, indicating the electrons transfer from CdS to SMSED. The planar charge density difference in Figure 5F further illustrates this phenomenon. At the heterojunction interface, the uneven charge distribution caused by charge carrier transfer gives rise to an interface polarization electric field. For SMSED/CdS, an internal electric field (IEF) is established orienting from CdS toward SMSED at their junction, which causes band bending near the heterojunction interface.

Based on the band structure, work function calculation and differential charge density simulation, the S-scheme charge transfer path in SMSED/CdS is confirmed, as shown in Figure 5G. SMSED has a lower Ef and a higher Φ than CdS. When they are in close contact, the following physical phenomena occur: (1) Band bending: Electrons migrate from CdS to SMSED, causing the SMSED band to bend downward and the CdS band to bend upward; (2) Charge distribution: An electron accumulation region and an electron depletion region are formed at the interface, resulting in a negative charge on SMSED and a positive charge on CdS; (3) IEF formation: Due to the uneven charge distribution, an IEF is formed pointing from CdS to SMSED, which helps accelerate charge separation and suppress recombination. When the SMSED/CdS heterojunction is irradiated, electrons in CdS and SMSED are excited from the VB to the CB, generating electron-hole pairs. Driven by the IEF, electrons in the CB of SMSED recombine with holes in the VB of CdS, and an S-scheme charge transfer pathway is formed. The ex-situ/in-situ irradiated XPS results [Figure 4B-I] also support the S-scheme charge transfer mechanism.

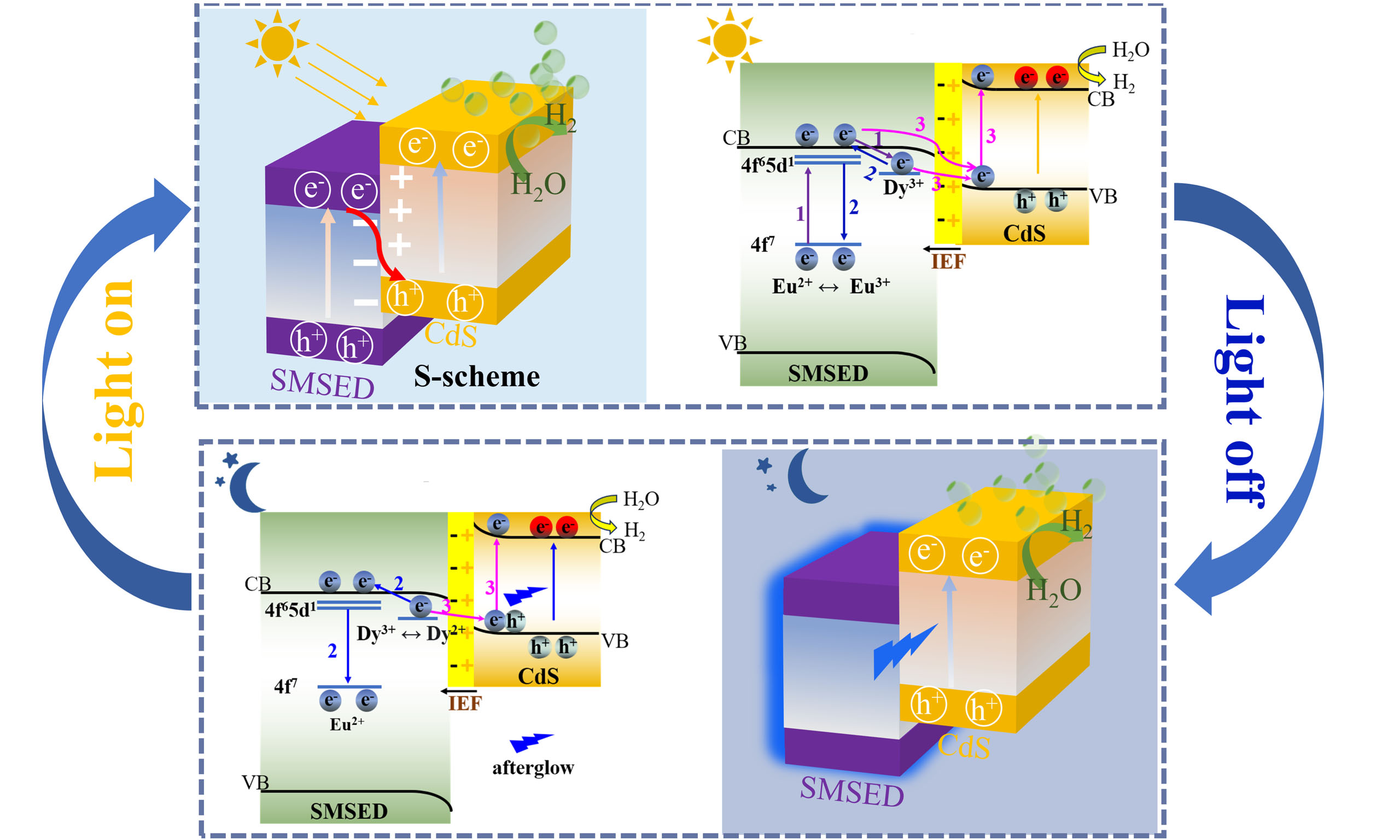

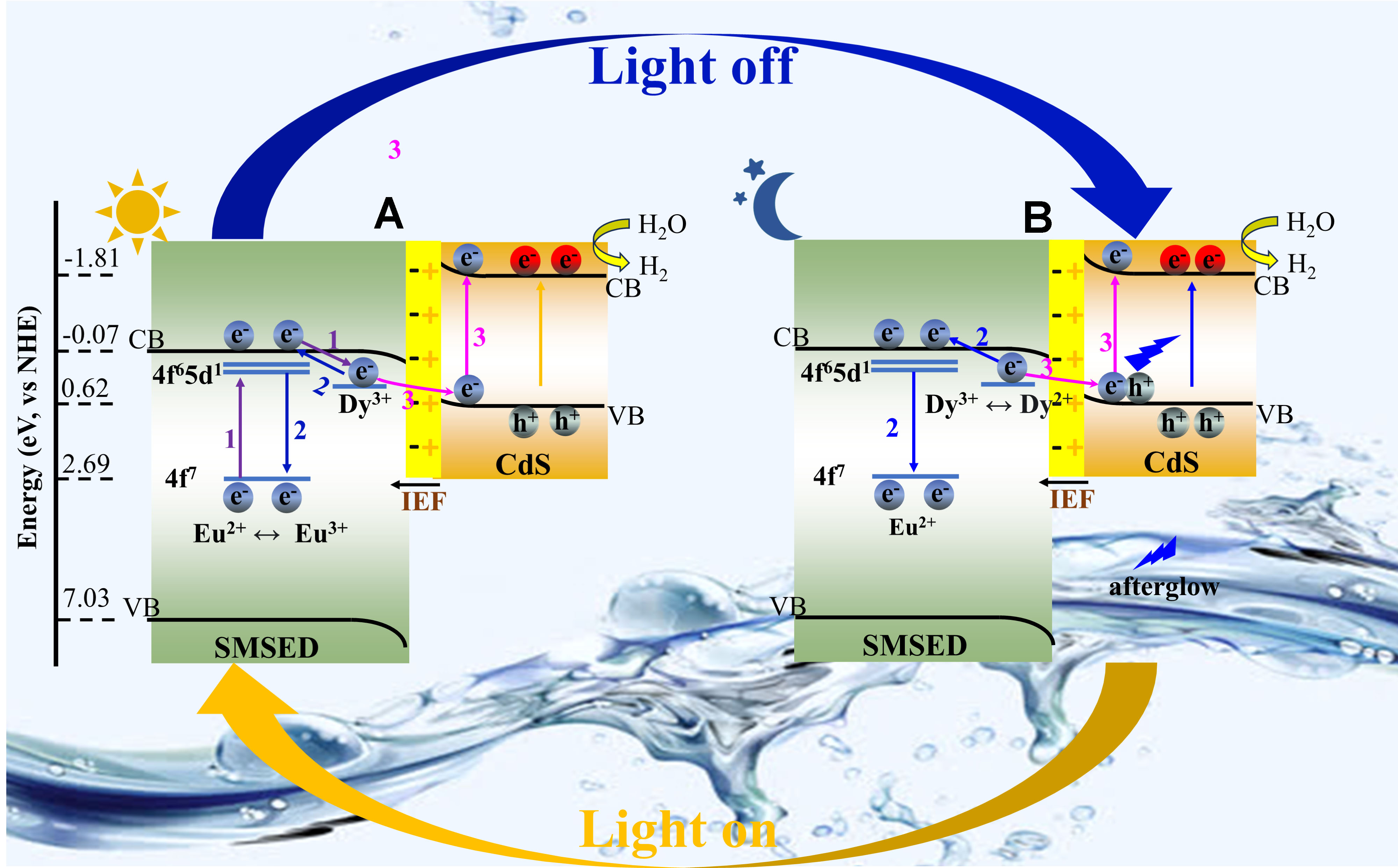

The mechanism of round-the-clock photocatalytic hydrogen production for S-scheme SMSED/CdS heterojunction is proposed in Figure 6. Firstly, SMSED, as a long afterglow material, has a unique charge transfer mechanism in the photocatalytic process. Under light irradiation [Figure 6A], electrons in the Eu2+ 4f7 energy level of SMSED are excited to the 4f65d1 energy level, and then enter the CB of the Sr2MgSi2O7 host material, generating free electrons and Eu3+. The free electrons transfer through two key pathways: (1) A portion of the electrons is captured and stored by Dy3+ traps (purple Path 1), and gradually released subsequently to form long-lived electrons (blue Path 2). Some of these long-lived electrons recombine with Eu3+ to produce long afterglow, thereby enhancing the light energy harvesting efficiency of CdS; (2) Other electrons, together with some long-lived electrons, follow the S-scheme mechanism and transfer to the VB of CdS driven by the IEF. They are further excited to the CB of CdS (pink Path 3) and participate in the photocatalytic water-reduction reaction together with the electrons generated by CdS itself.

Figure 6. Possible mechanism of round-the-clock photocatalytic hydrogen production over the S-scheme SMSED/CdS heterojunction. (A) UV-visible-light-driven catalysis; (B) Dark catalysis. IEF: Internal electric field. Path 1: Electrons in SMSED transition from the ground state to an excited state, and then to the CB and enter traps; Path 2: Photoluminescence; Path 3: The path of photo-generated electrons in SMSED. SMSED: Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy); CB: conduction band; VB: valence band; UV: ultraviolet; NHE: normal hydrogen electrode.

Secondly, after turning off the external light source [Figure 6B], the electrons stored in Dy3+ traps are slowly released to form long-lived electrons, which also have two paths: (1) A portion of the electrons transition to the ground state and emit fluorescence (blue Path 2), endowing SMSED with long afterglow properties and making it an internal light source of the heterojunction; (2) The remaining electrons transfer to the VB of CdS driven by the IEF, and are excited to the CB of CdS by SMSED fluorescence (pink Path 3). Finally, these electrons participate in the reduction of water to hydrogen on the surface of CdS. Benefiting from SMSED’s long-afterglow property, this dark catalytic process can continue for several hours.

When the afterglow luminescence of SMSED fails to provide sufficient energy for CdS-mediated catalytic processes, external illumination can be applied to maintain photocatalytic activity. Conversely, when SMSED slowly releases enough light energy, the external light source can be turned off, allowing the system to enter a dark catalytic state. Through this alternating light/dark process, sustainable photocatalysis can be achieved. Compared with previous reports [Supplementary Tables 6 and 7], the S-scheme SMSED/CdS heterojunction system exhibits an outstanding round-the-clock photocatalytic hydrogen production performance. This is because the S-scheme SMSED/CdS heterojunction can fully exploit SMSED’s unique charge-transfer pathways, providing more long-lived charge carriers to participate in the photocatalytic reaction, unlike other long-afterglow photocatalysts.

CONCLUSIONS

We successfully prepared an S-scheme SMSED/CdS heterojunction via ball milling for round-the-clock photocatalytic hydrogen production. The hydrogen production of SMSED/CdS reached 45.20 mmol g-1 under UV-vis light within 1 h, while in the dark it reached 4.37 mmol g-1, sustaining for 3 h. The remarkable catalytic performance of SMSED/CdS can be attributed to three key factors: CdS effectively absorbs the fluorescence emitted by SMSED, allowing SMSED to serve as an internal light source; the S-scheme heterojunction drives directional charge transfer and maintains optimal redox capability; SMSED, as a long afterglow material, provides a unique charge transfer pathway that contributes to more long-lived electrons within the S-scheme SMSED/CdS heterojunction catalytic system. The mechanisms are also investigated through theoretical and experimental methods. This study offers important insights for the development and design of round-the-clock photocatalysts.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization and Investigation: Wang, J.; Zhang, K.

Writing-Review & editing: Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Sun, Z.

Methodology: Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Xu, X.; Shi, X.

Data curation: Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Shi, X.; Wang, C.; Fan, C.

Funding acquisition and supervision: Wang, J.; Yang, H. Y.; Wu, Y.

Availability of data and materials

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52372151).

Conflicts of interest

Wu, Y. the Editor-in-Chief of Energy Materials, was not involved in any stage of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Hisatomi, T.; Yamada, T.; Nishiyama, H.; Takata, T.; Domen, K. Materials and systems for large-scale photocatalytic water splitting. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2025, 10, 769-82.

2. Guo, L.; Li, R.; Liu, J.; Xi, Q.; Fan, C. Study on hydrogen evolution efficiency of semiconductor photocatalysts for solar water splitting. Prog. Chem. 2020, 32, 46-54.

3. Mohapatra, L.; Parida, K. A review of solar and visible light active oxo-bridged materials for energy and environment. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 2153-64.

4. Ni, M.; Leung, M. K.; Leung, D. Y.; Sumathy, K. A review and recent developments in photocatalytic water-splitting using TiO2 for hydrogen production. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2007, 11, 401-25.

5. Wang, S.; Hou, H.; Cao, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, W. Properties and modulation strategies of ZnIn2S4 for photoelectrochemical water splitting: opportunities and prospects. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500080.

6. Roda, D.; Trzciński, K.; Łapiński, M.; et al. The new method of ZnIn2S4 synthesis on the titania nanotubes substrate with enhanced stability and photoelectrochemical performance. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21263.

7. Liu, J.; Ma, N.; Wu, W.; He, Q. Recent progress on photocatalytic heterostructures with full solar spectral responses. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124719.

8. Huang, Z.; Chen, B.; Ren, B.; et al. Smart mechanoluminescent phosphors: a review of strontium-aluminate-based materials, properties, and their advanced application technologies. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2204925.

9. Liu, X.; Chu, H.; Li, J.; et al. Light converting phosphor-based photocatalytic composites. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 4727-40.

10. Bidwai, D.; Kumar Sahu, N.; Dhoble, S. J.; Mahajan, A.; Haranath, D.; Swati, G. Review on long afterglow nanophosphors, their mechanism and its application in round-the-clock working photocatalysis. Methods. Appl. Fluoresc. 2022, 10, 032001.

11. Sakar, M.; Nguyen, C. C.; Vu, M. H.; Do, T. O. Materials and mechanisms of photo-assisted chemical reactions under light and dark conditions: can day-night photocatalysis Be achieved? ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 809-20.

12. Fei, Q.; Chang, C.; Mao, D. Luminescent properties of Sr2MgSi2O7 and Ca2MgSi2O7 long lasting phosphors activated by Eu2+, Dy3+. J. Alloys. Compd. 2005, 390, 133-7.

13. Jiang, T.; Wang, H.; Xing, M.; Fu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Luo, X. Luminescence decay evaluation of long-afterglow phosphors. Physica. B. Condens. Matter. 2014, 450, 94-8.

14. Cui, G.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Round-the-clock photocatalytic hydrogen production with high efficiency by a long-afterglow material. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1340-4.

15. Pei, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhong, J.; et al. Oxygen vacancy‐rich Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+ long afterglow phosphor as a round‐the‐clock catalyst for selective reduction of CO2 to CO. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2208565.

16. Shi, C.; Fu, Y.; Liu, B.; et al. The roles of Eu2+ and Dy3+ in the blue long-lasting phosphor Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+. J. Lumin. 2007, 122-123, 11-3.

17. Wu, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X. Investigation of the trap state of Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+ phosphor and decay process. Radiat. Meas. 2011, 46, 591-4.

18. Lin, Y.; Nan, C.; Zhou, X.; et al. Preparation and characterization of long afterglow M2MgSi2O7-based (M: Ca, Sr, Ba) photoluminescent phosphors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003, 82, 860-3.

19. Durga Prasad, K. A. K.; Rakshita, M.; Sharma, A. A.; et al. Enhanced blue emission and afterglow properties of Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+ phosphors for flexible transparent labels. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 137, 045102.

20. Wang, J.; Pan, R.; Yuan, Z.; et al. Functionalized Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy)@CdS heterojunction photocatalyst for round-the-clock hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148296.

21. Yang, X.; Tang, B.; Cao, X.; Ding, Y.; Huang, M. Light-storing assisted photocatalytic composite g-C3N4/Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy) with sustained activity. J. Photoch. Photobio. A. Chem. 2021, 411, 113202.

22. Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Novel Z-scheme Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+/Ag3PO4 photocatalyst for round-the-clock efficient degradation of organic pollutants and hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 134773.

23. Xu, M.; Wu, J.; Zheng, M.; Wang, J. Fabrication of active Z-scheme Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+/COF photocatalyst for round-the-clock efficient removal of total Cr. Molecules 2024, 29, 4327.

24. Tang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Fabrication of loaded Ag sensitized round-the-clock highly active Z-scheme BiFeO3/Ag/Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+/Ag photocatalyst for metronidazole degradation and hydrogen production. J. Power. Sources. 2023, 580, 233433.

25. Bu, X.; Sun, T.; Liu, Y.; Mi, R.; Mei, L. Round-the-clock photocatalysis of plasmonic Ag-enhanced Z-scheme heterojunction material Sr2MgSi2O7:(Eu,Dy)/gC3N4@Ag under visible-light irradiation. Mol. Catal. 2024, 552, 113674.

26. Zhang, H.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; et al. High performance long-afterglow phosphor-based ZnIn2S4/Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+ photocatalyst capable of dark state long-term application for photocatalytic sterilization. J. Alloys. Compd. 2025, 1010, 176711.

27. Ma, X.; He, S.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, Z. Fabrication of double S-scheme Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+/ZnIn2S4/UiO-66-NH2 heterojunctions with photon storage effect for enhanced round-the-clock photocatalysis. J. Alloys. Compd. 2025, 1010, 176993.

28. Yang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, G.; Tang, J.; Liu, J. Sustainable photocatalytic process using non-silver agent ZnO/P-g-C3N4/Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+ for antibacterial activity. J. Alloys. Compd. 2024, 1005, 176017.

29. Ruan, X.; Xu, M.; Ding, C.; et al. Cd single atom as an electron mediator in an S‐scheme heterojunction for artificial photosynthesis of H2O2. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2025, 15, 2405478.

30. Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; García, H. Charge-transfer dynamics in S-scheme photocatalyst. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2025, 9, 328-42.

31. Deng, J.; Xu, X.; Su, B.; et al. Structural amine-induced interfacial electrical double layers for efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 5702-9.

32. Tang, G.; Zhang, J.; Bie, C.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, C.; Yu, J. In situ soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy investigation on charge transfer mechanism in COF/CdS S-scheme photocatalyst. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e14576.

33. Hu, L.; Liu, X.; Dai, R.; Lai, H.; Li, J. Enhancing photocatalytic H2 evolution of Cd0.5Zn0.5S with the synergism of amorphous CoS cocatalysts and surface S2- adsorption. Fuel 2025, 382, 133737.

34. Zhou, G.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G.; et al. Enhanced CO2 photoreduction in pure water systems by surface-reconstructed asymmetric Mn-Cu sites. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2025, 361, 124617.

37. He, H.; Canning, G. A.; Nguyen, A.; et al. Active-site isolation in intermetallics enables precise identification of elementary reaction kinetics during olefin hydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 596-605.

38. Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Cui, W.; et al. Reactant activation and photocatalysis mechanisms on Bi-metal@Bi2GeO5 with oxygen vacancies: a combined experimental and theoretical investigation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 370, 1366-75.

39. Sun, L.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X.; et al. An internal electric field and interfacial S-C bonds jointly accelerate S-scheme charge transfer achieving efficient sunlight-driven photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022, 10, 25279-94.

40. Zhang, Y.; Su, Q.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z. Surface Modification of Mg-Al hydrotalcite mixed oxides with potassium. Acta. Phys. Chim. Sin. 2010, 26, 921-6.

41. Yu, Q.; Yan, C.; Deng, Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, B. Effect of Fe2O3 on non-isothermal crystallization of CaO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2 glass. Trans. Nonferrous. Met. Soc. China. 2015, 25, 2279-84.

42. Quynh Lien, N. T.; Hong, T. T.; Van Do, P.; Van Tuyen, H. Influence of dopant concentration on Raman spectra and Judd-Ofelt intensity parameters of red-emitting Eu3+-doped Sr2MgSi2O7. Opt. Mater. 2025, 160, 116754.

43. Hanuza, J.; Ptak, M.; Mączka, M.; Hermanowicz, K.; Lorenc, J.; Kaminskii, A. Polarized IR and Raman spectra of Ca2MgSi2O7, Ca2ZnSi2O7 and Sr2MgSi2O7 single crystals: temperature-dependent studies of commensurate to incommensurate and incommensurate to normal phase transitions. J. Solid. State. Chem. 2012, 191, 90-101.

44. Chougale, A. S.; Wagh, S. S.; Waghmare, A. D.; Jadkar, S. R.; Shinde, D. R.; Pathan, H. M. Boosting photoelectrochemical water splitting activity of zinc oxide by fabrication of ZnO/CdS heterostructure for hydrogen production. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 2024, 7, 1023.

45. Dan, M.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, S.; Prakash, A.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y. Noble-metal-free MnS/In2S3 composite as highly efficient visible light driven photocatalyst for H2 production from H2S. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2017, 217, 530-9.

46. Dai, B.; Fang, J.; Yu, Y.; et al. Construction of infrared-light-responsive photoinduced carriers driver for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1906361.

47. Boolakee, T.; Heide, C.; Garzón-Ramírez, A.; Weber, H. B.; Franco, I.; Hommelhoff, P. Light-field control of real and virtual charge carriers. Nature 2022, 605, 251-5.

48. Wang, K.; Li, Q.; Liu, B.; Cheng, B.; Ho, W.; Yu, J. Sulfur-doped g-C3N4 with enhanced photocatalytic CO2-reduction performance. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2015, 176-177, 44-52.

49. Wang, J.; Niu, X.; Wang, R.; et al. High-entropy alloy-enhanced ZnCdS nanostructure photocatalysts for hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2025, 362, 124763.

50. Sun, H.; Mei, L.; Liang, J.; et al. Three-dimensional holey-graphene/niobia composite architectures for ultrahigh-rate energy storage. Science 2017, 356, 599-604.

51. Yang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Yan, C.; Xue, Z.; Mu, T. The pivot to achieve high current density for biomass electrooxidation: accelerating the reduction of Ni3+ to Ni2+. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2023, 330, 122590.

52. Mu, J.; Miao, H.; Liu, E.; et al. Enhanced light trapping and high charge transmission capacities of novel structures for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 11881-93.

53. Hu, T.; Dai, K.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S. Noble-metal-free Ni2P modified step-scheme SnNb2O6/CdS-diethylenetriamine for photocatalytic hydrogen production under broadband light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2020, 269, 118844.

54. Hu, Y.; Hao, X.; Cui, Z.; et al. Enhanced photocarrier separation in conjugated polymer engineered CdS for direct Z-scheme photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2020, 260, 118131.

55. Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Guo, X.; Jin, Z. Flowered molybdenum base trimetallic oxide decorated by CdS nanorod construct S-scheme heterojunctions for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 196, 112-24.

56. Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, B.; Yu, J.; Fan, J. Step-scheme CdS/TiO2 nanocomposite hollow microsphere with enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction activity. J. Mater. Scie. Technol. 2020, 56, 143-50.

57. Chen, W.; Zhao, N.; Hu, M.; Liu, X.; Deng, B. Strengthened removal of tetracycline by a Bi/Ni Co-doped SrTiO3/TiO2 composite under visible light. Catalysts 2024, 14, 539.

58. Gatou, M. A.; Bovali, N.; Lagopati, N.; Pavlatou, E. A. MgO nanoparticles as a promising photocatalyst towards rhodamine B and rhodamine 6G degradation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4299.

59. Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Low-temperature catalytic CO2 dry reforming of methane on Ni-Si/ZrO2 catalyst. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 6495-506.

60. Yu, M.; Ong, J.; Tran, D.; et al. Low temperature Cu/SiO2 hybrid bonding via <1 1 1>-oriented nanotwinned Cu with Ar plasma surface modification. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 636, 157854.

61. Chen, M.; Yang, T.; Zhao, L.; et al. Manganese oxide on activated carbon with peroxymonosulfate activation for enhanced ciprofloxacin degradation: activation mechanism and degradation pathway. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 645, 158835.

62. Bezkrovnyi, O. S.; Blaumeiser, D.; Vorokhta, M.; et al. NAP-XPS and in situ DRIFTS of the interaction of CO with Au nanoparticles supported by Ce1-xEuxO2 nanocubes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2020, 124, 5647-56.

63. Khataee, A.; Karimi, A.; Zarei, M.; Joo, S. W. Eu-doped ZnO nanoparticles: Sonochemical synthesis, characterization, and sonocatalytic application. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 67, 102822.

64. Wu, H.; Xu, M.; Chang, C. Modulating the valence of Eu2+/Eu3+ in Sr2MgSi2O7 for white luminescence. J. Alloys. Compd. 2024, 1002, 175430.

65. Yao, Z.; Zheng, G.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, L. Synthesis of the Dy:SrMoO4 with high photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 32, e4412.

66. Yang, X.; Tang, B.; Cao, X. The roles of dopant concentration and defect states in the optical properties of Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,Dy3+. J. Alloys. Compd. 2023, 949, 169841.

67. Jin, Z.; Wu, Y. Novel preparation strategy of graphdiyne (CnH2n-2): one-pot conjugation and S-Scheme heterojunctions formed with MoP characterized with in situ XPS for efficiently photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2023, 327, 122461.

68. Qiu, P.; Xu, C.; Chen, H.; et al. One step synthesis of oxygen doped porous graphitic carbon nitride with remarkable improvement of photo-oxidation activity: Role of oxygen on visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2017, 206, 319-27.

69. Ruan, X.; Cui, X.; Cui, Y.; et al. Favorable energy band alignment of TiO2 anatase/rutile heterophase homojunctions yields photocatalytic hydrogen evolution with quantum efficiency exceeding 45.6%. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2200298.

70. Dorenbos, P. Mechanism of persistent luminescence in Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+;Dy3+. Phys. Stat. Sol. (b). 2005, 242.

71. Hölsä, J.; Kirm, M.; Laamanen, T.; Lastusaari, M.; Niittykoski, J.; Novák, P. Electronic structure of the Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+ persistent luminescence material. J. Lumin. 2009, 129, 1560-3.

72. Aitasalo, T.; Hassinen, J.; Hölsä, J.; et al. Synchrotron radiation investigations of the Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+,R3+ persistent luminescence materials. J. Rare. Earths. 2009, 27, 529-38.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].