Heterogenized homogeneous catalysts for photoelectrochemical carbon dioxide reduction: a path toward ideal hybrid systems

Abstract

The development of technologies that convert solar or electrical energy into sustainable chemical fuels remains a central challenge in the field of energy research. Among various strategies, photoelectrochemical cells (PECs) that enable the direct conversion of carbon dioxide (CO2) into value-added fuels such as carbon monoxide (CO), formic acid (HCOOH), formaldehyde (HCHO), and methanol (CH3OH) using sunlight have gained considerable attention. While most PEC systems rely on heterogeneous catalysts, the emerging approach of heterogenizing homogeneous molecular catalysts onto electrode surfaces offers a promising pathway that combines the molecular-level tunability of homogeneous systems with the robustness and recyclability of heterogeneous platforms. Anchoring molecular catalysts onto conductive or semiconductive surfaces not only enhances charge transport efficiency from the substrate to the active site, enabling high current densities, but also facilitates integration into device-scale architectures. Among various immobilization strategies, covalent anchoring via functionalized ligands has proven particularly effective in ensuring strong surface binding. However, the impact of such covalent anchoring on the catalytic activity and long-term stability of molecular catalysts remains poorly understood. This review highlights recent advances in hybrid molecular PEC systems for selective CO2 reduction to CO and formate, focusing on the design of modular ligands with surface anchoring functionalities. We summarize current covalent immobilization techniques and discuss the mechanistic implications of catalyst-surface interactions. Finally, we outline key challenges and future directions toward the rational design of robust, selective, and scalable molecular-material hybrid catalysts for solar fuel production.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The efficient conversion of solar energy into storable chemical fuels represents one of the most ambitious goals in the pursuit of sustainable and carbon-neutral energy technologies[1-5]. With the escalating global energy demand and the progressive depletion of fossil fuel reserves, transitioning to renewable energy sources has become an urgent necessity to curb greenhouse gas emissions and address climate change[6,7]. Solar energy, with its vast abundance and global accessibility, offers a particularly attractive solution[1-14]. However, its inherently intermittent and diurnal nature imposes critical challenges for continuous energy supply[4,15,16]. Photovoltaic devices can efficiently convert sunlight into electricity, yet the direct storage of electrical energy remains technologically and economically constrained, particularly for large-scale applications[17,18]. This limitation underscores the urgent need for complementary strategies that can transform solar-derived electrons into high-energy-density, transportable, and versatile chemical fuels.

Photoelectrochemical (PEC) systems provide a promising platform for solar-to-chemical energy conversion by directly coupling light harvesting with fuel-forming redox reactions[19-25]. Mimicking natural photosynthesis, including light harvesting, catalytic water oxidation, CO2 reduction, and energy storage, requires materials that seamlessly integrate efficient photon capture, rapid charge transport, and robust catalytic activity[26-28]. PEC devices integrate semiconductor photoelectrodes and catalytic components to drive water oxidation and proton reduction, generating hydrogen under solar illumination[29-31]. The produced hydrogen can be further utilized for CO2 hydrogenation to value-added fuels, expanding the scope of solar-derived energy carriers[32-34]. PEC systems are essential for solar energy conversion, addressing critical energy and environmental issues[26-28]. Moreover, bio-hybrid PEC devices integrate the complementary advantages of both biocatalyst and abiotic components, providing opportunities for efficient catalysis under mild conditions with high selectivity and low overpotential[35].

Conventional PEC and photocatalytic systems are fundamentally limited by incomplete utilization of the solar spectrum and rapid recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, resulting in a narrowed redox potential window and low overall conversion efficiency[26-28,36]. Most semiconductor photocatalysts rely on band-gap excitation, but their insufficient visible-light absorption significantly restricts solar energy harvesting[37]. In addition, the use of heavy-metal-based semiconductors raises concerns regarding environmental impact and sustainability[26-28,36,37]. Even in hybrid or bio-hybrid PEC systems, practical applications are further constrained by inefficient interfacial charge transfer, limited biocatalyst stability, and scalability challenges[35]. Although molecular catalysts offer broader absorption profiles and tunable electronic structures, their effective integration with semiconductor photoelectrodes remains challenging[26-28,36,37]. Overcoming these intrinsic limitations of conventional photocatalysts is therefore critical for advancing efficient and durable solar-driven catalytic systems.

Central to the performance of PEC devices is the development of efficient, robust, and selective catalysts for key fuel-forming reactions[19-25]. Homogeneous transition metal complexes have long been recognized for their unparalleled tunability in terms of electronic properties[38-41], ligand design[42-48], and mechanistic control[49-54]. Despite offering well-defined active sites and mechanistic clarity, homogeneous catalytic systems remain fundamentally limited by catalyst separation, recyclability, and scalability issues that restrict their practical and industrial applicability[55-59]. On the other hand, heterogeneous catalysis often suffers from ill-defined and dynamically evolving active sites, coupled with mass and heat transfer limitations, which complicate structure-activity correlations and hinder precise control over selectivity and long-term stability[60]. As a result, immobilization of molecular catalysts onto solid surfaces, including conductive electrodes, semiconductor light absorbers, and nanostructured materials, offers a promising strategy to bridge the gap between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis[50,61-63]. By anchoring discrete molecular sites to a solid support, one can combine the well-defined active site structures of homogeneous systems with the operational durability and integration capabilities of heterogeneous platforms[50,61-63].

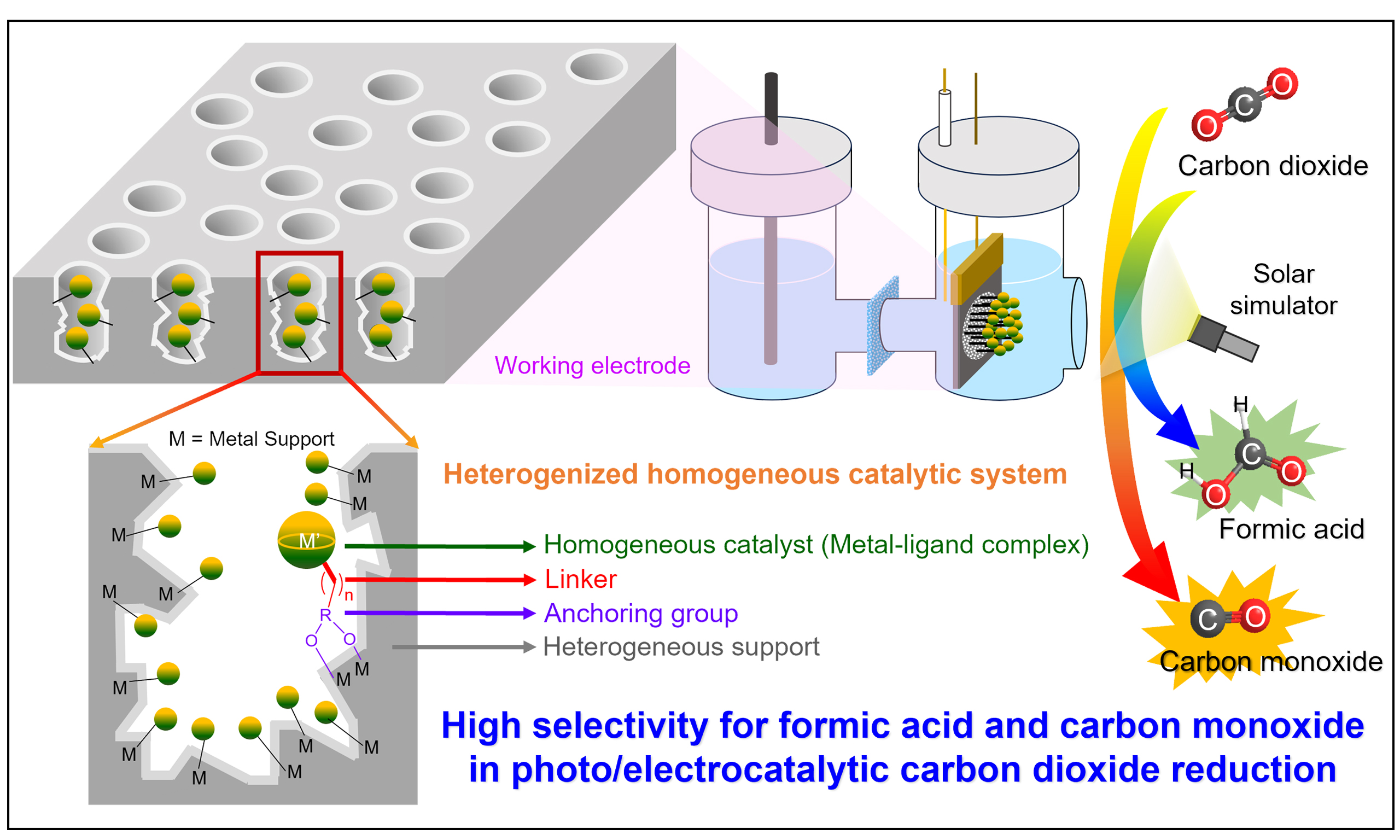

Effective immobilization of molecular catalysts on photoelectrode or particle surfaces requires the coordinated design of three interdependent components, such as the coordination complex, anchoring group, and linker, each tailored to the substrate and operating conditions to maintain high activity, stability, and selectivity [Figure 1][64]. The linker’s length, rigidity, and electronic characteristics, together with the bonding nature of the anchoring group, critically govern interfacial electron transfer kinetics and catalytic performance, necessitating structural modifications that preserve the steric and electronic integrity of the catalyst.

Figure 1. Illustration of a molecular catalyst immobilized on the surface of a support, including anchoring group, linker group, and catalyst group, indicating the key structural elements that facilitate efficient electronic communication between the catalyst and the substrate[64].

This hybrid approach offers several potential advantages: (i) optimized interfacial architecture that ensures efficient charge transfer while spatially arranging catalytic sites to facilitate cooperative or cascade reactions; (ii) enhanced structural and chemical stability by physically immobilizing the catalyst at the interface, preventing degradation and leaching; and (iii) high compatibility with device integration, enabling seamless incorporation into membrane electrode assemblies, tandem PEC cells, or flow electrolyzers[65-67]. In addition, immobilization can modulate the microenvironment around the active site, altering local hydrophobicity, proton availability, and substrate diffusion, thereby influencing both catalytic activity and selectivity[68-70].

A diverse toolbox of immobilization strategies has been developed, encompassing covalent attachment through ligand functionalization, coordination to surface-bound metal sites, electrostatic interactions, π-π stacking with carbon-based materials, and encapsulation in polymeric or supramolecular matrices[17,71-74]. Among these, covalent immobilization via functionalized ancillary ligands is particularly valued for its mechanical robustness and resistance to catalyst leaching under operational conditions[75,76]. This approach, however, often requires extensive synthetic modification of ligand frameworks, which can be synthetically demanding and time-intensive, particularly for complex polydentate scaffolds[77-81]. Furthermore, while many proof-of-concept systems have been reported, systematic structure-activity relationships correlating the nature of surface binding groups (e.g., phosphonates, carboxylates, silatranes, and thiols) with catalytic performance, stability, and interfacial electron transfer kinetics remain relatively underexplored[77-81].

In the heterogenized iridium water oxidation system reported by Materna et al., the anchoring-linker-catalyst triad is clearly delineated, with a silatrane moiety serving as the anchoring group, a phenylene-based linker, and an iridium molecular catalyst as the active center. The silatrane anchor enables robust covalent attachment to metal oxide surfaces, effectively suppressing metal leaching under electrochemical conditions. This work exemplifies a rational triad design that balances molecular precision with surface stability, while also revealing durability limitations associated with ligand degradation during prolonged catalysis[82-85]. Furthermore, a wide range of studies have employed ruthenium- and rhodium-based molecular catalysts as model systems, owing to their well-defined coordination environments and high catalytic activity, making them particularly suitable for probing structure-reactivity relationships in hybrid catalytic platforms[82-85].

Hybrid catalytic systems, while conceptually intended to bridge the molecular precision of homogeneous catalysts with the robustness and recyclability of heterogeneous platforms, often struggle to retain the intrinsic reactivity and well-defined coordination environments of their molecular counterparts[86]. In practice, immobilization and atomic dispersion strategies can introduce significant perturbations to the electronic structure of the active site, leading to diminished catalytic performance, ambiguous structure-activity relationships, and unintended changes in reaction pathways[86]. Consequently, persistent challenges such as active-site heterogeneity, metal leaching, sintering under operating conditions, and limited long-term durability continue to undermine the realization of truly synergistic hybrid catalytic systems.

In this review, we provide a comprehensive overview of recent advances in the design, synthesis, and implementation of molecular catalysts immobilized on solid supports for solar-driven fuel-forming reactions. We highlight fundamental principles of catalyst-support interactions, survey representative anchoring strategies, and critically discuss their implications for charge transfer, stability, and catalytic performance. Finally, we identify emerging trends and key challenges, emphasizing the need for integrated approaches that unite synthetic ligand design, interfacial chemistry, and device engineering toward efficient, durable, and scalable solar-to-fuel conversion technologies.

STRATEGIES FOR MOLECULAR CATALYST IMMOBILIZATION

The immobilization of molecular catalysts onto supports has emerged as a pivotal strategy to simultaneously achieve high selectivity and efficiency in PEC CO2 reduction. In PEC devices, a molecular catalyst must be stably anchored to the electrode surface while maintaining strong chemical adhesion, high electrochemical stability, efficient interfacial charge transfer, resistance to leaching, and unhindered substrate accessibility under reductive operating conditions[22,30,75,81]. In addition, the immobilization architecture must minimize catalyst-semiconductor charge recombination to preserve overall device efficiency[31,87-89]. Achieving this balance requires a tailored approach that accounts for the chemical nature of both the catalyst and the semiconductor substrate.

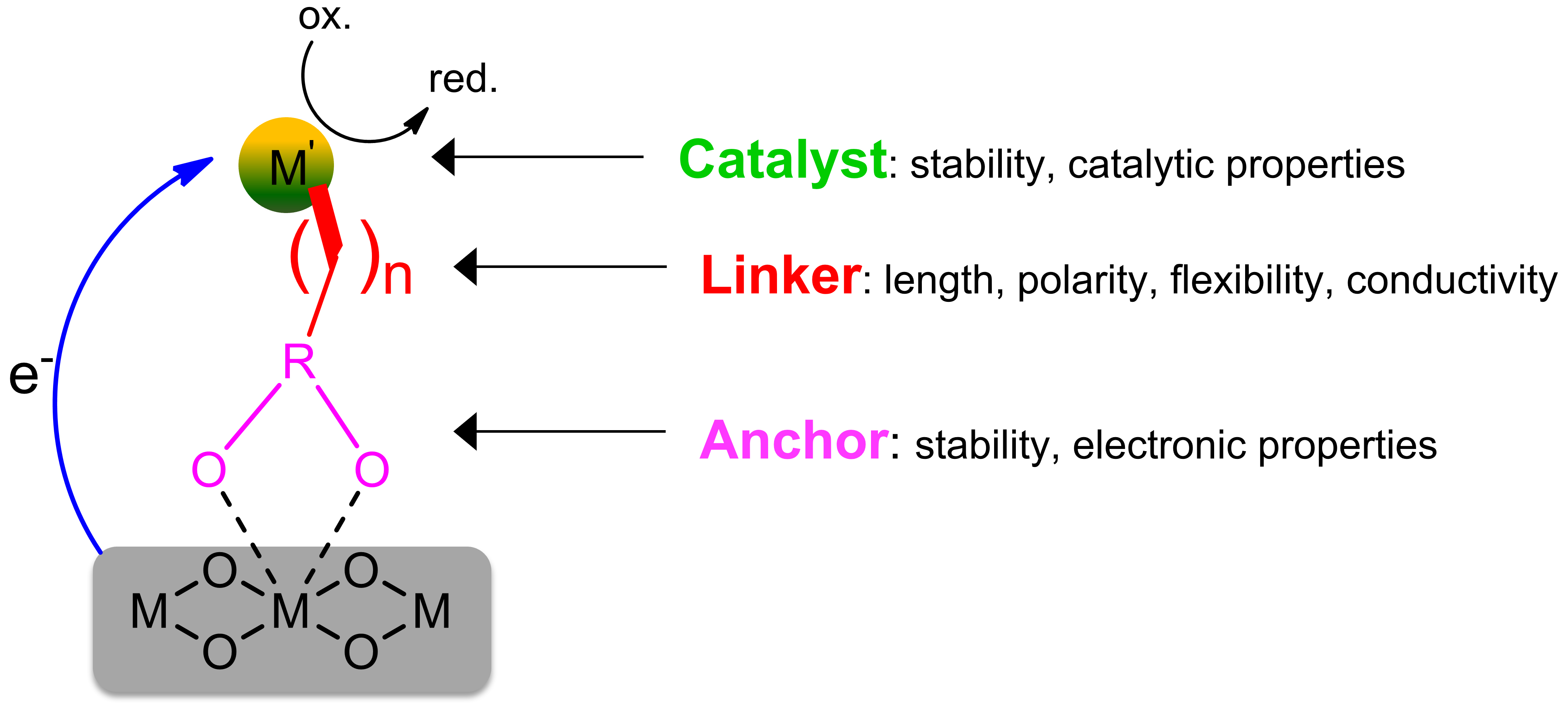

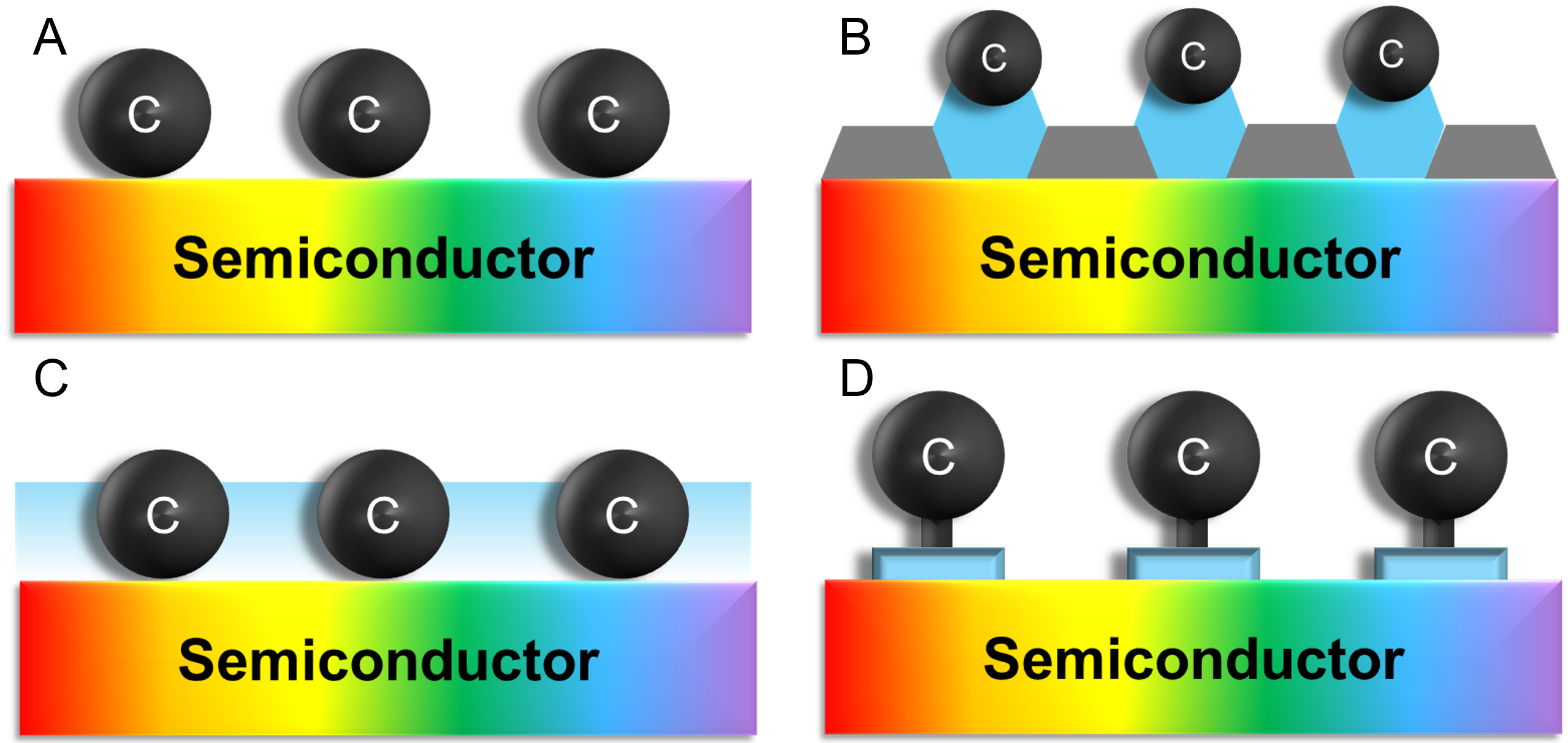

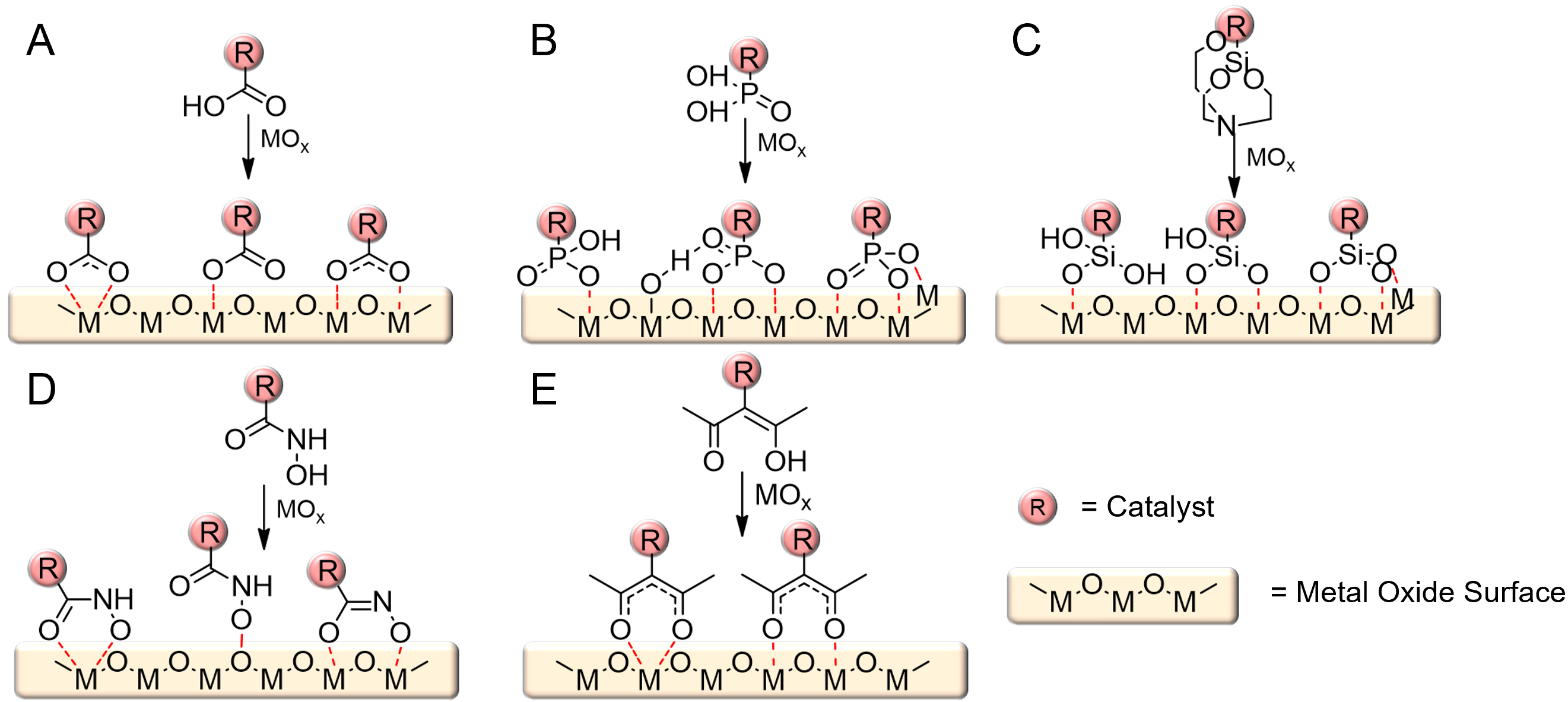

Existing immobilization strategies can be broadly categorized into four major classes [Figure 2][17,71-75]. The direct adsorption method relies on weak van der Waals or electrostatic interactions between the catalyst and the electrode surface [Figure 2A][71,90]. While experimentally simple, this approach suffers from poor long-term stability under operational conditions. The π-π stacking strategy exploits aromatic-aromatic interactions, particularly between polyaromatic ligands and carbon-based electrodes, to achieve stronger noncovalent binding [Figure 2B][71,90]. However, the aromatic framework can degrade under high potentials or oxidative environments, leading to gradual activity loss. The physical entrapment method embeds catalysts within polymer matrices or porous inorganic hosts. This approach can yield relatively stable films and enables selective retention of charged catalysts (e.g., cationic species in anionic hydrated channels) but may suffer from low catalyst loading and increased overpotentials in highly ion-conducting media [Figure 2C][71,90]. The most robust method is covalent binding, in which anchoring groups are introduced into the ligand framework to form strong chemical bonds with the semiconductor surface [Figure 2D][71,90]. Common anchors include carboxylic acids, phosphonic acids, hydroxamic acids, and silatranes, which undergo condensation with surface hydroxyl groups on metal oxides to generate stable linkages [Figure 3][71-77]. Each anchoring group has its own stability and electron-transfer ability. Carboxylic acid is stable under pH 4 and has 13 fs time constants for electron injection from the perylene to the TiO2 conduction band. Phosphonic acid is stable under pH 7 and has 28 fs time constants under the same conditions. Hydroxamic acid is stable under pH 2-10.25 and has 2.9 times more efficient electron injection in time-resolved picosecond terahertz spectroscopy compared to carboxylic acid[71]. Silatranes, in particular, exhibit strong binding to SiOx and TiO2 surfaces and can be attached under mild conditions (pH 2-11), making them attractive for a wide range of systems[71].

Figure 3. Different types of anchoring groups in covalent binding immobilization strategies[71]. (A) Carboxylate anchoring through chelating, unidentate, or bridging binding; (B) phosphonate anchoring through mono-, bi-, and tridentate binding; (C) silatrane anchoring through mono-, bi-, or tridentate binding; (D) hydroxamate anchoring through chelating, unidentate, and bridging binding; and (E) acetylacetonate anchoring through chelating and bridging binding. Reprinted with permission from Ref.[71]. Copyright © 2020, American Chemical Society.

While covalent anchoring provides superior mechanical and operational stability, the harsh electrochemical environment of CO2 reduction, which is characterized by high electron densities and reactive intermediates, demands that the ligand scaffold be intrinsically resistant to oxidative and reductive degradation[91]. Weak C-H bonds or reduction-sensitive functionalities should be avoided, and ligand backbones should be designed for maximal redox stability, which can increase synthetic complexity and cost. To address these limitations, strategies such as multisite anchoring and post-immobilization surface passivation with hydrophobic polymers or inorganic overlayers have been developed to shield the catalyst from deleterious conditions[80]. Such protective schemes can significantly extend catalyst lifetime under PEC operation.

The choice of anchoring chemistry must also be matched to the surface properties of the semiconductor. For example, TiO2 and SnO2 possess abundant surface hydroxyls conducive to condensation reactions with phosphonate or carboxylate anchors. In contrast, nitride semiconductors such as Ta3N5 exhibit lower surface reactivity and susceptibility to hydrolytic degradation, making conventional oxide-directed anchors less effective[92]. In such cases, surface pretreatment or alternative chemistries, such as silatrane grafting via native oxide layers, can be required[71].

SYNTHESIS OF EFFICIENT SUPPORT

Heterogeneous catalytic systems were developed to ensure robustness, recyclability, and operational stability under practical reaction conditions; however, their future advancement critically depends on improving active-site definition and achieving molecular-level control over catalyst structure and reactivity[60]. Beyond oxides, a variety of support materials have been explored for catalyst immobilization, each with specific anchoring considerations. Carbon-based electrodes [graphite, glassy carbon, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene] can be modified covalently via oxidative functionalization, diazonium coupling, cycloaddition, or azide click chemistry, or noncovalently through π-π interactions (e.g., pyrene derivatives) and hydrophobic polymer adsorption[93-97]. Noncovalent modification preserves the intrinsic conductivity and π-conjugation of carbon materials, while covalent modification offers stronger attachment at the cost of potential surface damage.

The choice of substrate plays a decisive role in determining the performance, stability, and integration of immobilized molecular catalysts in PEC devices. Among the most widely explored platforms, both carbon-based supports such as organic graphene layers enabling noncovalent immobilization of molecular catalysts[98], and metal oxides (MOx), such as TiO2, SnO2, Fe2O3, and WO3, offer high chemical stability and tunable bandgaps, with hydroxyl-rich surfaces that enable covalent catalyst attachment via condensation with anchoring groups, including phosphonates[99-101], carboxylates[99-103], organosilatranes/silazanes[100-103], hydroxamates[104-106], and acetylacetonates[71,78]. While carboxylates are synthetically accessible and effective in nonaqueous systems, their stability under neutral or basic aqueous conditions is limited. Phosphonates form stronger and more hydrolytically stable bonds, with multiple binding modes that can enhance interfacial electron transfer, whereas silatranes afford exceptional pH tolerance through robust Si-O-metal linkages[71]. Hydroxamates and acetylacetonates offer compact footprints, enabling dense monolayer formation and, in some cases, faster electron transfer kinetics[71]. In all cases, surface conditions containing hydroxyl concentration and Lewis acidity with functionalization protocols must be matched to the selected anchor to achieve high coverage and durability [Figure 3][71]. Moreover, hydroxyl-mediated covalent anchoring on metal oxides, π–π driven immobilization on conductive carbon supports has emerged as an effective alternative, enabling molecular level dispersion and strong electronic coupling that support high site utilization and durable catalytic performance under high current operation[107].

Nonoxide semiconductors, such as p-type Si, gallium phosphide (GaP), and metal chalcogenides containing cadmium sulfide (CdS), indium phosphide (InP), and gallium arsenide (GaAs), provide narrower bandgaps for enhanced visible-light absorption but often suffer from poor chemical stability in aqueous or aerobic environments, forming passivating oxide layers that hinder charge transfer[17,108-111]. Protective coatings, commonly TiO2 overlayers, are employed to prevent surface oxidation while retaining light-harvesting properties, enabling the use of conventional oxide-directed anchoring strategies. Among these, CdS has emerged as a prototypical visible-light-responsive material that combines a moderate band gap (~2.4 eV), high photoconductivity, and tunable surface chemistry[110]. Mechanistic studies using methyl viologen (MV2+) revealed that CdS enables direct electronic coupling between its conduction band and adsorbed redox species without requiring covalent linkers[110]. MV2+ adsorbs either through ligand exchange with surface Cd-oleate groups [association constant (Ka) ≈ 3.5 × 103 M-1] or by direct binding to S-terminated facets (Ka ≈

The emergence of organic polymer-based photocathodes, such as poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT)-C60 bulk heterojunctions, has opened new possibilities for integrating molecular catalysts onto flexible, tunable light absorbers[112,113]. Among organic supports, conjugated polymer photocathodes provide tunable band gaps (1.1-2.4 eV), strong visible-light absorption, and mechanical flexibility[112]. π-Conjugated polymers such as poly(p-phenylenevinylene) (PPV) and P3HT enable direct electronic coupling with immobilized catalysts through π-π interactions or covalent grafting, for example via aryldiazonium-derived C-C bonds[112]. These interfaces facilitate ultrafast charge transfer and adjustable highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)-lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) alignment through donor-acceptor tuning of the polymer backbone[113]. The catalytic performance depends critically on molecular ordering and interfacial passivation: well-ordered, regioregular films promote carrier mobility, while oxidation or structural disorder introduces trap states that degrade stability[113]. Overall, conjugated polymers offer lightweight, flexible, and electronically tunable platforms for hybrid molecular catalysts, though maintaining interfacial integrity remains essential for durable operation. While few examples currently combine organic photocathodes with immobilized molecular catalysts, the incorporation of chemically defined interlayers between the polymer and electrolyte interfaces may enable anchoring strategies similar to those used for inorganic substrates[114-116]. Such approaches could extend molecular catalyst integration to organic photovoltaic architectures for solar fuel production.

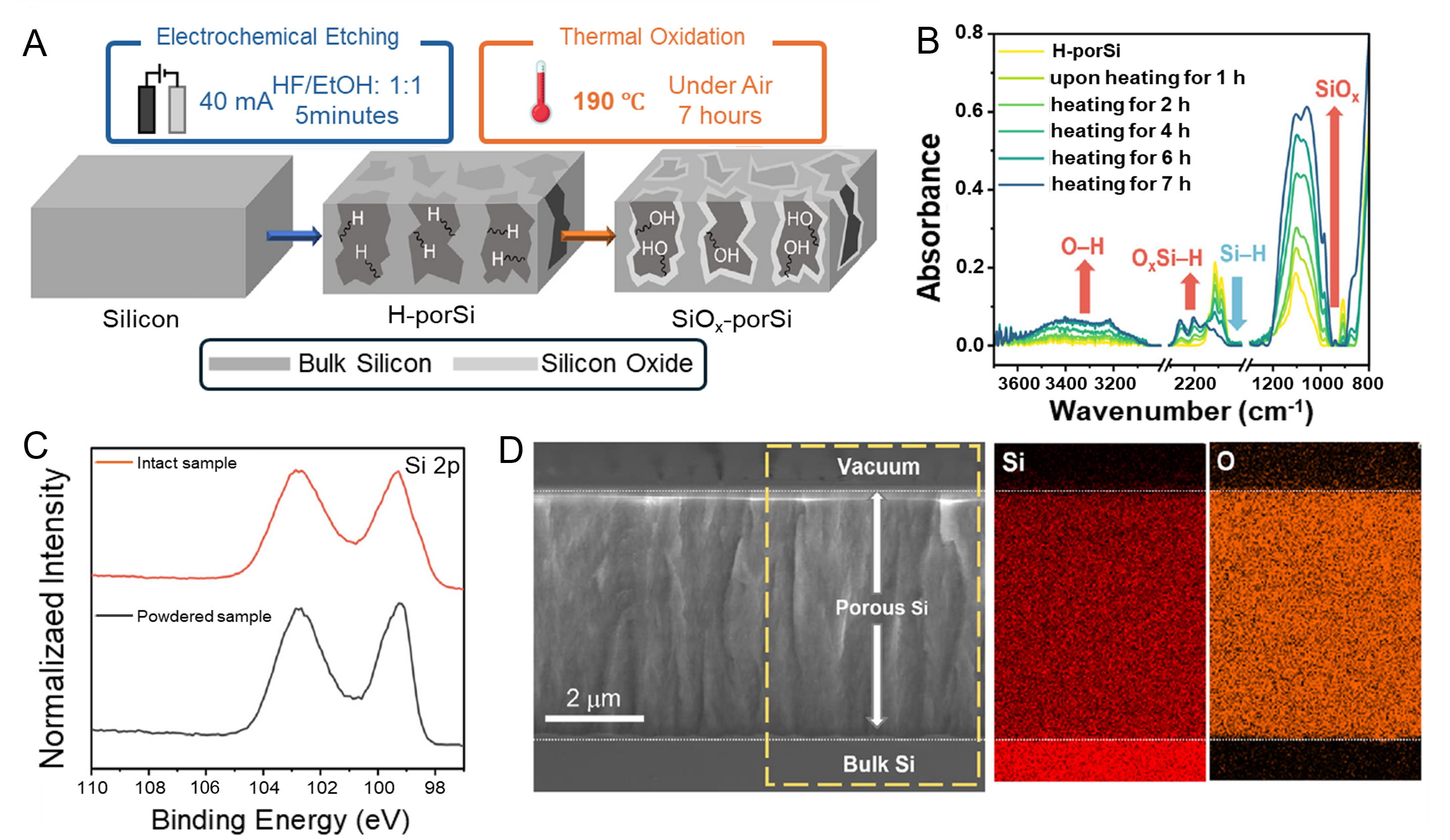

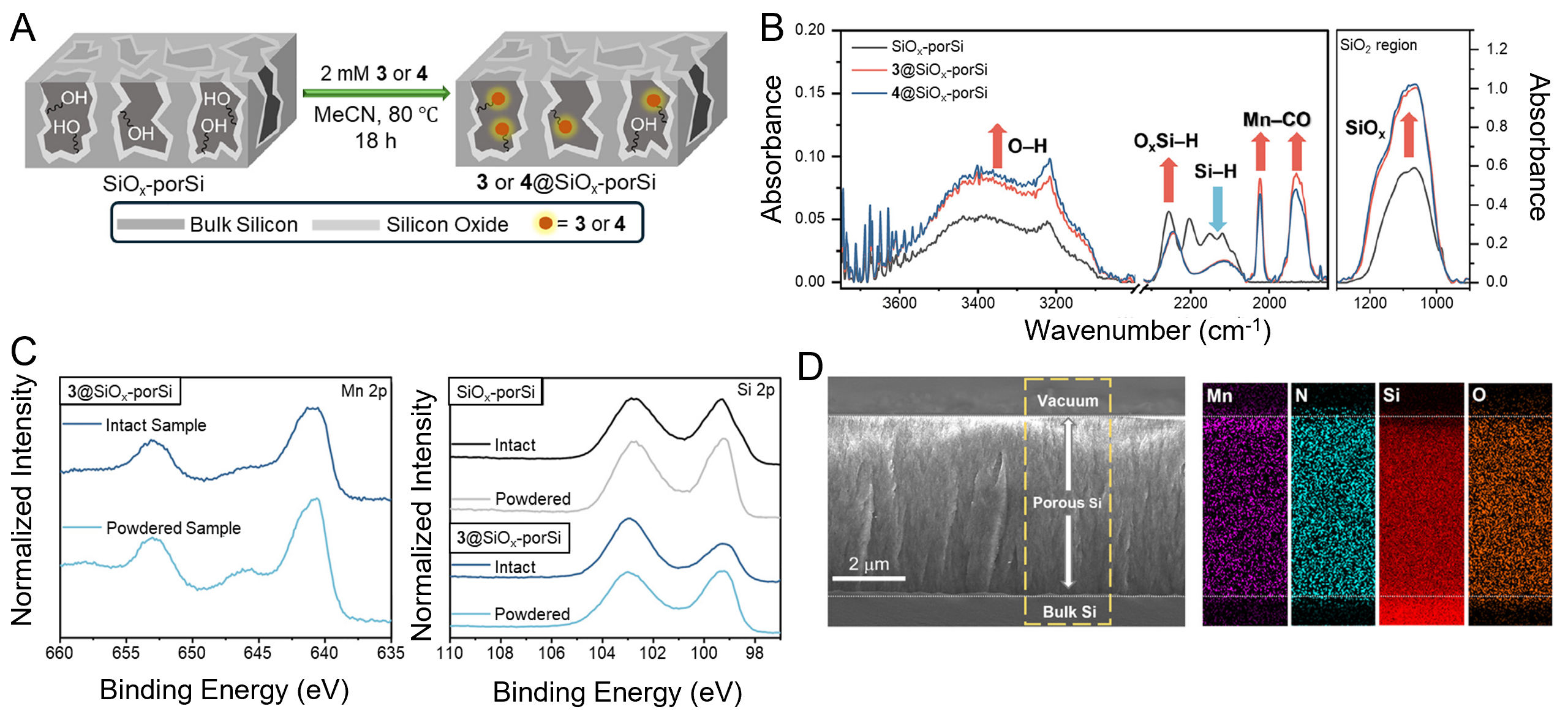

Porous silicon (porSi) has emerged as an attractive support for hybrid catalytic systems due to its high surface area, earth abundance, and compatibility with molecular catalyst immobilization[117-120]; however, its intrinsic limitations warrant careful consideration[121-125]. Electrochemical etching produces sponge-like porSi architectures with internal wall depths of several micrometers and surface areas exceeding 200 m2 g-1, enabling high catalyst loadings and efficient light absorption. In hydrogen-terminated porSi (H-porSi), the highly reactive Si-H surface allows direct covalent attachment of molecular catalysts via hydrosilylation[117]. Nevertheless, steric constraints prevent the formation of a complete catalyst monolayer, leaving residual Si-H sites that can undergo uncontrolled reactions[117]. These remaining Si-H functionalities may evolve H2 or even reduce CO2 stoichiometrically under reductive conditions, thereby complicating mechanistic interpretation of catalytic activity. Moreover, the elevated temperatures required for hydrosilylation, as well as electrochemical operating conditions, accelerate surface oxidation and induce structural restructuring, leading to time-dependent changes in surface chemistry, porosity, and electronic properties[121-125]. To mitigate these issues, thermally oxidized porSi (SiOx-porSi) has been proposed as a more chemically robust platform, in which a silicon oxide passivation layer suppresses parasitic surface reactivity and enables catalyst immobilization under milder conditions, such as silatrane hydrolysis. Low-temperature thermal oxidation (~190 °C for 7 h) produces an oxide layer estimated to be thinner than 5 nm; however, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy indicates that this oxide layer is not spatially uniform, highlighting an additional level of surface heterogeneity [Figure 4][126]. Cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirms that the overall porous morphology is largely preserved after oxidation, although the accessible surface area decreases to approximately 70 m2 g-1 [Figure 4][126]. While SiOx-porSi exhibits improved chemical stability relative to H-porSi and has successfully supported first-row transition-metal catalysts for PEC CO2-to-formate conversion[126]. However, SiOx-porSi includes limitations of the increased electronic resistance due to oxide thickening and non-uniform oxide growth, and gradual degradation during prolonged electrochemical operation due to porosity collapse and long-term charge transport limitations. These factors can substantially influence catalyst accessibility, electron transfer efficiency, and durability, underscoring the need for systematic stability studies.

Figure 4. Producing scheme and characterization of thermally oxidized porSi wafers (SiOx-porSi)[126]. (A) Scheme for synthesizing SiOx-porSi using electrochemical etching and thermal oxidation; (B) FTIR spectrum of conversion of H-porSi to SiOx-porSi according to heating time; (C) XPS spectra of intact and powdered SiOx-porSi samples in the Si 2p region; (D) Cross-sectional SEM image and EDS mapping for Si and O of SiOx-porSi. Reprinted with permission from Ref.[126]. Copyright © 2025, Elsevier. FTIR: Fourier transform infrared; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; EDS: energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.

Among the diverse substrates investigated for hybrid molecular catalysts, SiOx-porSi emerges as one of the most promising supports, combining high surface area, conductivity, tunable porosity, and chemical stability. Unlike conventional metal oxides or nonoxide semiconductors, SiOx-porSi provides a hydroxyl-rich yet electronically conductive interface that enables robust covalent anchoring while minimizing charge-transfer resistance. Its scalable fabrication, earth abundance, and compatibility with mild aqueous PEC conditions further highlight its potential as a next-generation platform for solar-driven CO2 conversion. Nevertheless, despite these advantages, current SiOx-porSi-based systems often lack a comprehensive critical analysis of degradation pathways, including oxide growth dynamics, porosity collapse, and long-term charge transport limitations. Addressing these unresolved challenges will require the rational design and synthesis of optimized substrate architectures, in which oxide thickness, interfacial uniformity, and electronic connectivity are deliberately controlled. Future efforts should therefore focus on developing new synthetic strategies for porSi-based supports that simultaneously preserve structural robustness, interfacial precision, and efficient charge transport, complemented by systematic stability tests and operando mechanistic studies. This direction is consistent with the comparative analysis summarized in Table 1, which highlights how substrate characteristics, anchoring motifs, and interfacial chemistry collectively dictate performance and limitations in hybrid PEC systems.

Comparison of substrate types regarding surface characteristics, common anchoring groups, and their resulting advantages and limitations for photoelectrochemical applications

| Substrate type | Surface characteristics | Common anchoring groups | Advantages | Limitations |

| Metal oxides[71,78,98,107] | High chemical stability; wide bandgap; tunable morphology | Carboxylates, phosphonates, organosilatranes/silazanes, hydroxamates, acetylacetonates | Abundant anchoring sites; strong covalent bonds; good aqueous stability | Some anchors are unstable at high pH; low electron transfer by thick overlayers; bandgap limits visible-light absorption |

| Nonoxide semiconductors[17,108-111] | Narrow bandgap; high visible-light absorption; chemically reactive surfaces | Thiols, carboxylates, phosphonates, amines; TiO2 overlayers enabling oxide-type anchoring | Efficient light harvesting; tunable bandgap; compatibility with protective coatings | Poor aqueous stability; low electron transfer by native oxides; typically low surface area |

| Organic photocathodes[112-116] | Flexible polymer surfaces; tunable energy levels; heterogeneous interface | Modified interlayers with carboxylates, phosphonates, silatranes; π-π interactions | Lightweight, flexible; molecular-level tunability; compatibility with solution processing | Limited examples with immobilized catalysts; stability issues under PEC conditions; anchoring strategies are less developed |

| Porous silicon[117-126] | High surface area; conductive; tunable porosity | Silatranes, phosphonates, carboxylates | Very high catalyst loading; low-cost and earth-abundant; oxide layer improves stability and anchoring versatility; visible-light absorbing | Residual Si-H bonds can cause H2 evolution (H-porSi); thick oxide layers can reduce electron transfer; the oxidation step must preserve porosity |

SELECTION OF EFFECTIVE TRANSITION METAL-BASED MOLECULAR CATALYSTS

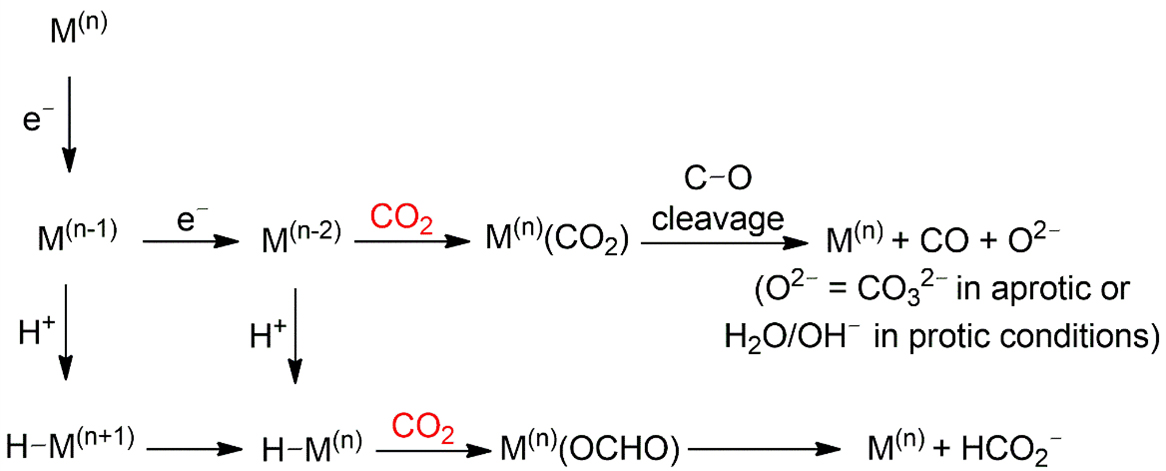

Homogeneous catalysis emerged to provide precise control over coordination environments and enable mechanistic insight; however, further progress requires overcoming limitations in catalyst recovery, stability, and scalability to extend their applicability beyond idealized reaction settings[59]. In molecular CO2 reduction, product selectivity is often dictated by the pathway of CO2 activation at the metal center, which typically proceeds either via insertion into a metal-hydride bond or coordination to a vacant site [Figure 5][18,33]. In the “normal” insertion pathway, electrostatic interactions between the polarized O-C and M-H bonds position the electrophilic carbon near the nucleophilic hydride, favoring HCOOH (formic acid/formate)

Figure 5. CO2 activation pathways at the metal center in the reaction of CO2 reduction[33]. In the above scheme, CO2 is activated by coordination to a vacant site of the metal center. In the scheme below, via insertion into the M(n)-H bond. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[33]. Copyright © 2018, American Chemical Society.

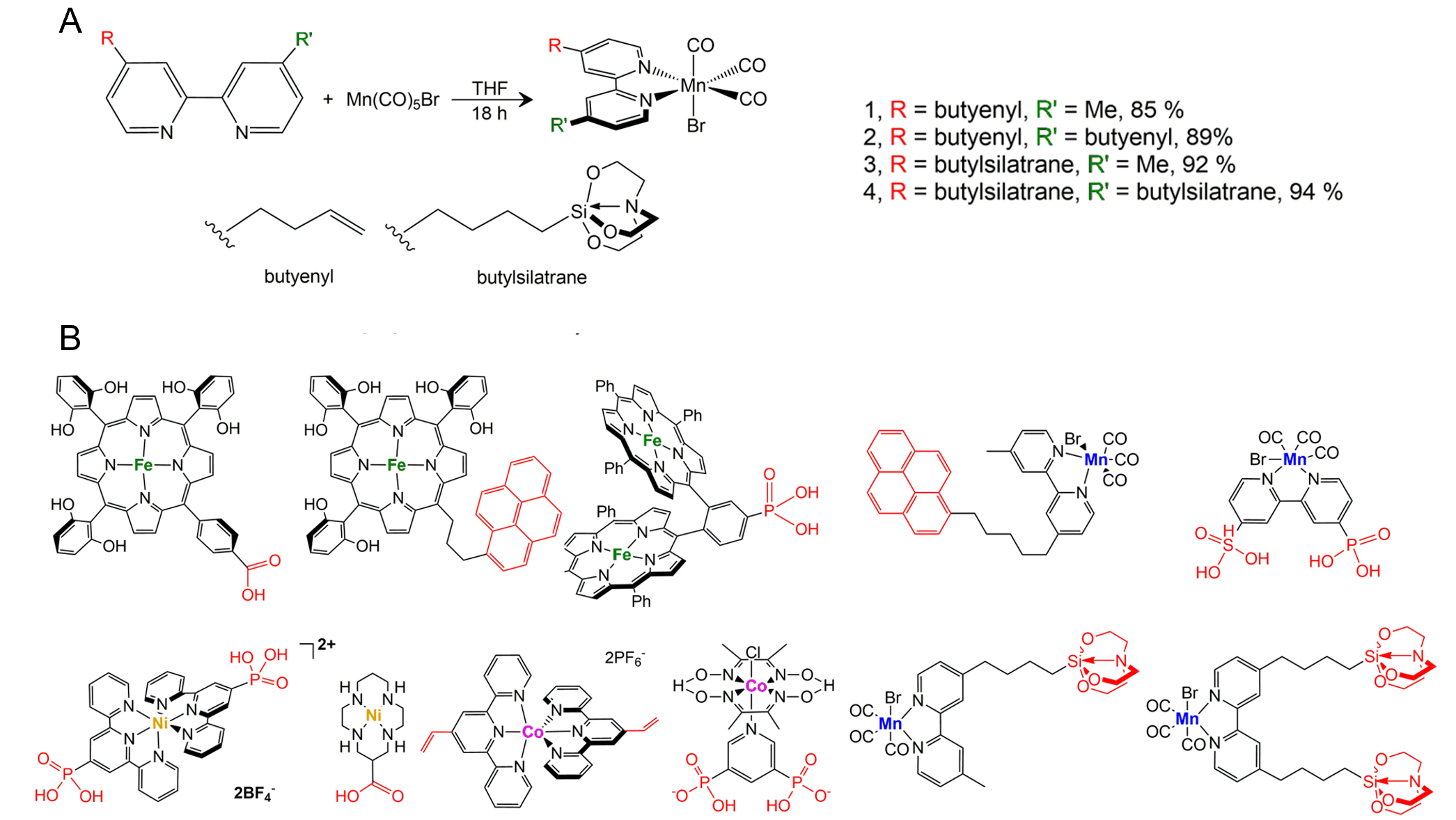

Manganese(I) bipyridine tricarbonyl complexes {fac-[MnBr(bpy-R)(CO)3]} constitute a well-studied class of CO2 reduction catalysts, typically showing high CO selectivity in the presence of a proton source such as water[131-134]. Their catalytic mechanism often involves one-electron reduction, halide dissociation, and either Mn-Mn dimer formation or direct generation of an anionic [Mn(bpy-R)(CO)3]- species, with subsequent CO2 activation occurring via a metallo-carboxylate intermediate[131-134]. Proton donors stabilize this intermediate, enabling CO formation, whereas C-coordination pathways can be suppressed by steric or electronic ligand modifications that inhibit dimerization. Strategies such as halide exchange to cyanide, the introduction of sterically bulky ligands, or the use of electron-rich donors [e.g., N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs), α-diimines] alter reduction potentials, intermediate stability, and catalytic onset, often impacting overpotentials and turnover numbers (TONs)[135-138].

Secondary sphere effects provide an additional avenue for tuning activity and selectivity. Incorporation of intramolecular proton relays, such as phenol or resorcinol units covalently tethered to the 2,2’-bipyridine (bpy) framework, can enhance catalytic currents and lower overpotentials by facilitating proton transfer to CO2-bound intermediates. These functionalities can also open new mechanistic pathways, including hydride formation, which can shift product distributions toward formate or hydrogen under certain conditions. Lewis acids, notably Mg2+, have been shown to promote C-O bond cleavage in metallo-carboxylic acid intermediates via an oxide-acceptor mechanism, generating insoluble MgCO3 and mitigating carbonate inhibition, though often at the expense of catalytic current density[139].

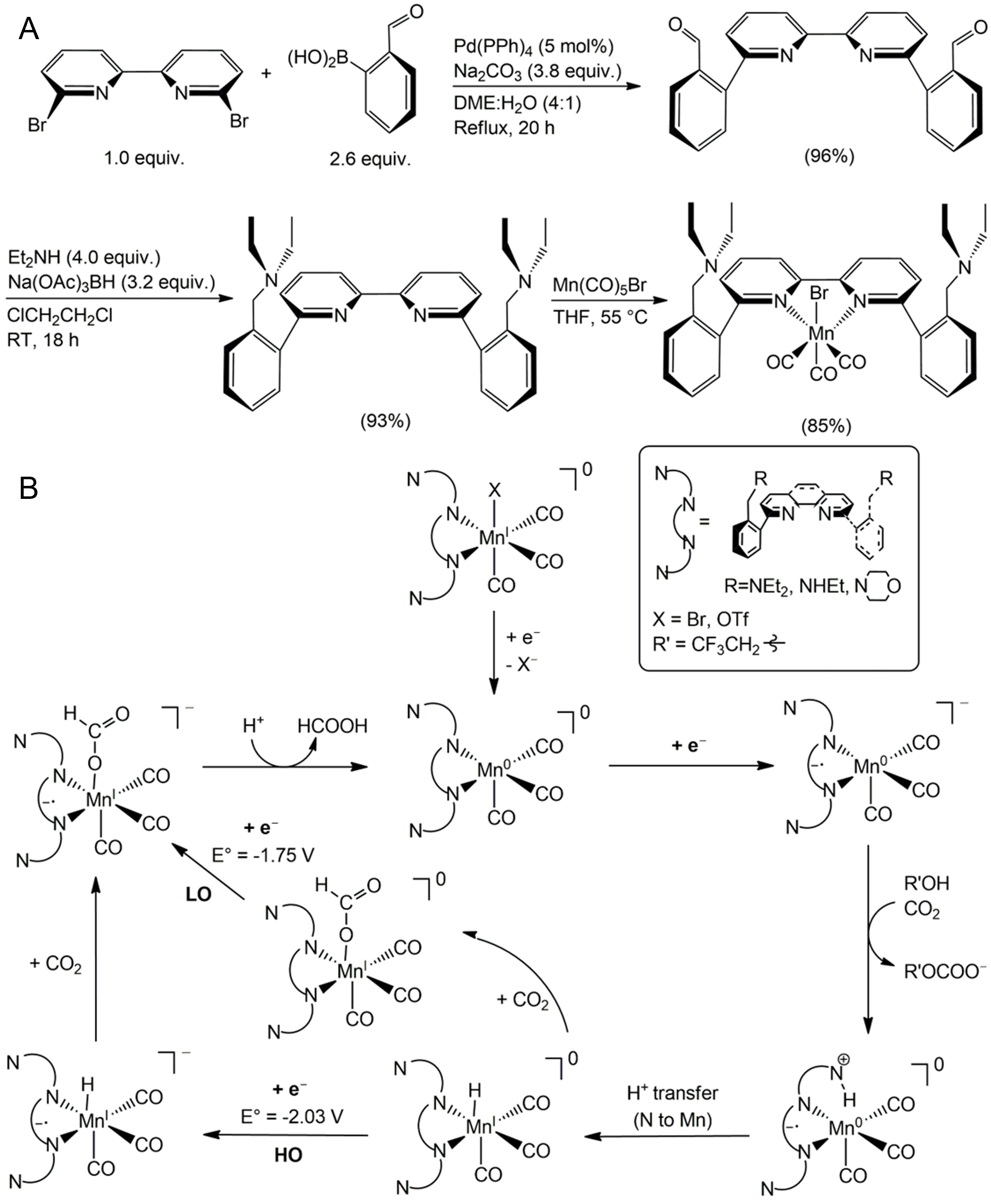

Manganese catalysts in Mn(bpy-R)(CO)3Br type have been extensively studied as molecular electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction. Modification of the bipyridine ligand with different substituents triggers alternative mechanistic pathways which can improve selectivity of products, enabling the preferential formation of formic acid (HCOOH) rather than carbon monoxide. Representative examples include the introduction of benzylic diethylamine, benzylic methanol, and benzylic ethane groups onto the bipyridine backbone [Figure 6A]. These functional groups act as Brønsted bases, shuttling protons to the Mn center under acidic conditions and enabling formation of HCOOH. Unlike unmodified parent complexes, which primarily generate CO, the functionalized ligands facilitate the formation of a Mn-H intermediate where CO2 can insert. Two distinct catalytic pathways have been proposed depending on the applied potential: at low overpotentials, CO2 insertion into the Mn-H bond occurs relatively slowly but with higher energy efficiency, whereas at high overpotentials, insertion proceeds rapidly albeit at the expense of energy efficiency [Figure 6B][140]. Despite variations in ligand structure and mechanistic details, many modified Mn-bipyridine systems retain the redox noninnocence of the bpy ligand, which contributes to selective CO2 activation over proton reduction through complementary σ- and π-interactions with CO2[141-143]. This electronic flexibility, combined with steric control and secondary sphere modulation, makes Mn(I) catalysts a highly versatile platform for designing selective CO2 reduction catalysts.

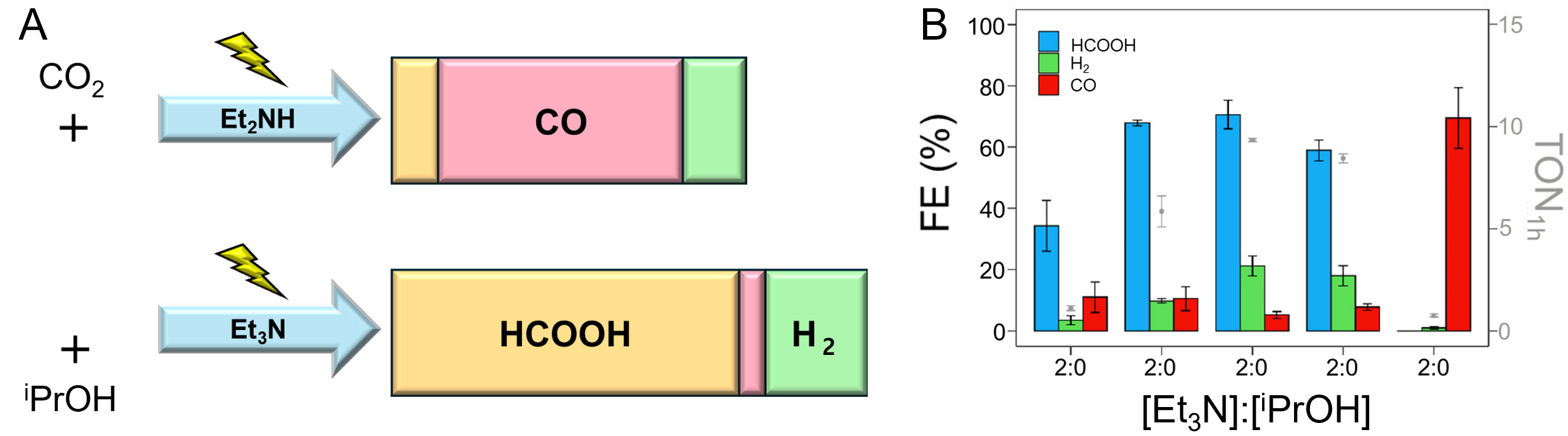

Regardless of ligand design or structural modifications, Mn-bipyridine catalysts can achieve comparable product selectivity using external additives. For instance, the addition of triethylamine (Et3N) serves as an effective proton shuttle [Figure 7]. Under acidic CO2-saturated conditions, Et3N facilitates proton transfer to the electrochemically reduced Mn(bpy)(CO)3Br complex, leading to the formation of a Mn-H intermediate. This pathway contrasts with diethylamine, which preferentially reacts with CO2 to generate carbamic acid rather than enabling hydride formation. Subsequent CO2 insertion into the Mn-H bond yields formate with high selectivity (up to 71%) at a relatively low overpotential (260 mV), distinguishing this mechanism from the conventional CO-forming route. Thus, the introduction of simple co-catalysts such as Et3N represents an attractive strategy to modulate product selectivity without the need for elaborate ligand synthesis or multi-step catalyst modification, instead allowing control over product distribution through judicious choice of external additives[144].

Figure 7. (A) Illustration for different methods for reducing CO2 using two types of additives such as Et2NH or Et3N, producing CO about 59% (above) or HCOOH about 73% (below), respectively; (B) Faraday Efficiency of formation of products such as HCOOH, H2, and CO using different ratios of Et3N and iPrOH[144]. Reprinted with permission from Ref.[144]. Copyright © 2021, American Chemical Society.

However, stability, overpotential requirements, and scalability remain critical challenges, particularly when translating homogeneous activity into immobilized or hybrid catalyst architectures. A variety of Manganese (I) bipyridine tricarbonyl complexes were synthesized to enable covalent immobilization onto either H-porSi via hydrosilylation (alkene-functionalized ligands) or SiOx-porSi via condensation with surface hydroxyls (silatrane functionalized ligands), providing robust hybrid photoelectrodes for CO2-to-CO or formate conversion[117,126]. Complexes bearing one or two alkene or silatrane groups were obtained in high yields (85%-94%) and fully characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), FTIR spectroscopy, ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy, high-resolution mass spectroscopy, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD)[126]. Electrochemical studies, including cyclic voltammetry (CV) and constant phase element (CPE) measurements, in acetonitrile (MeCN) revealed two reduction waves assigned to the Mn(I)/Mn(0) and Mn(0)/Mn(-I) processes, with significant catalytic current enhancement under CO2 in the presence of proton sources[126]. Controlled potential electrolysis demonstrated that in Et3N/iPrOH electrolyte, the immobilization-capable Mn complexes maintained high catalytic activity and selectivity for formate [Faradaic efficiency (FE) up to 82%], comparable to or exceeding the parent (bpy)Mn(CO)3Br system, indicating that anchoring group incorporation does not compromise catalytic performance[126].

Moreover, manganese(I) tricarbonyl CO2 reduction catalysts have also been investigated in photocatalytic systems, despite their propensity to release CO upon irradiation[145-150]. One of the manganese(I) complexes, such as Mn, absorbs partially in the visible region and can undergo CO loss or Mn-Mn dimer formation upon photoexcitation, with the resulting dimers and radicals displaying distinct reactivity[145-150]. In systems employing photosensitizers (PSs) with sacrificial electron and proton donors, initial PS-mediated reduction of manganese can generate Mn-dimers that photolyze to reactive radicals, favoring formate production via hydride pathways[145-150]. Related complexes such as nitrile-bound manganese(I) complexes, which do not dimerize, exhibit solvent-dependent product selectivity linked to the lifetime of singly reduced radicals, enhancing formate yields, and are shorter-lived in MeCN, favoring CO formation[151]. Ligand variation, as in phenanthroline-based manganese(I) complexes with organic dye, can shift selectivity toward CO, with high TONs and minimal H2 evolution[152]. These studies reveal that under photocatalytic conditions, manganese(I) CO2 reduction catalysts can access diverse mechanistic pathways via dimers, radicals, or hydride intermediates, offering tunable selectivity between CO and formate.

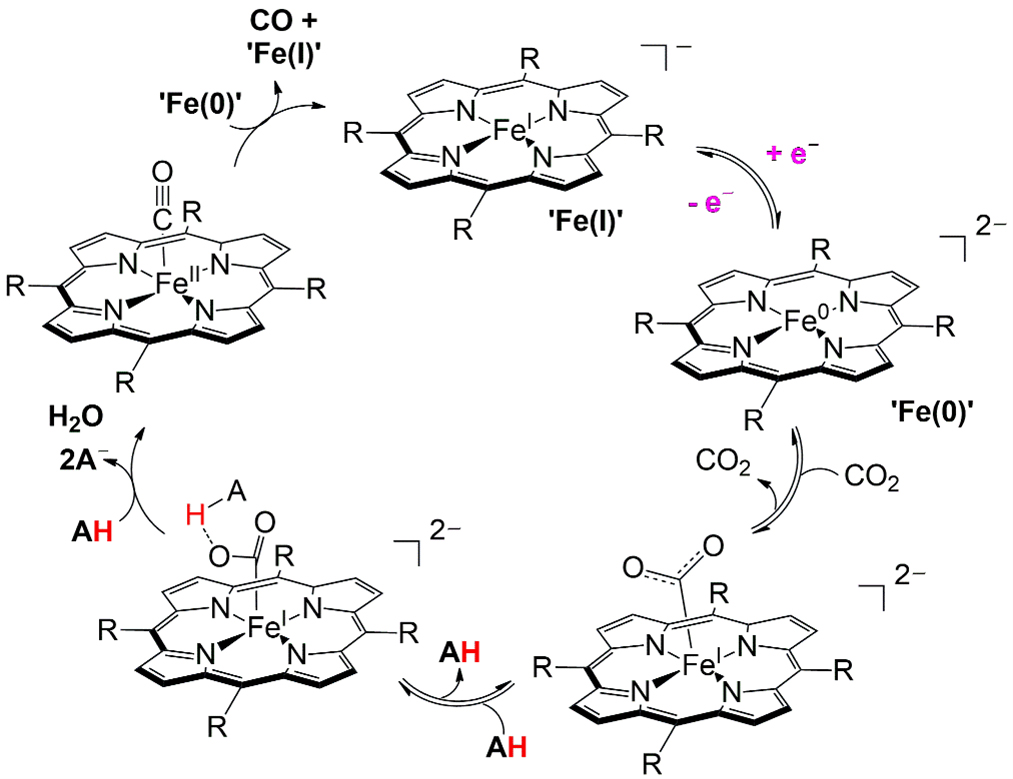

Iron-based CO2 reduction catalysts are among the most extensively studied, with iron porphyrin complexes [e.g., tetraphenylporphyrin (TPP)] representing a highly adaptable platform for tuning electronic properties and transition state stabilization. Most iron porphyrin CO2 reduction catalysts have been investigated in polar aprotic solvents such as N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and MeCN, where weak Brønsted acids [H2O, 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE), phenol] or Lewis acids (Mg2+, Ca2+) enhance catalytic performance[153-156]. These air-stable iron(III) species undergo three sequential reductions to generate an Fe(0) state, which spectroscopic and computational evidence suggest is better described as an Fe(II) ligand diradical, while still displaying metal-centered reactivity [Figure 8][157]. For the parent Fe-TPP complex, catalytic onset for CO2 reduction to CO occurs near the Fe+/Fe0 couple [-1.67 V vs. saturated calomel electrode (SCE) in DMF], with the mechanism involving formation of an Fe+-CO2•- adduct and a rate-determining step that couples the second electron transfer with protonation and C-O bond cleavage[157]. The cycle is closed by CO release from a product-inhibited Fe2+-CO adduct via reaction with another Fe0 species[157].

Figure 8. Catalytic CO2 reduction mechanism of Fe-porphyrin complexes, involving formation of an Fe-CO2•- adduct, stepwise reduction from Fe(II) to Fe(0)[157]. The rate-determining step is a concerted proton-coupled electron transfer with C-O bond cleavage, ultimately leading to CO release from an inhibited Fe-CO intermediate. Reprinted with permission from Ref.[157]. Copyright © 2013, American Chemical Society.

Beyond porphyrins, other aromatic iron catalysts for CO2 reduction have been developed with varying selectivities. For example, iron complexes, based on a qpy (2,2′:6′,2″:6″,2‴-quaterpyridine) scaffold, achieved 100% CO selectivity but only moderate FE of CO (FECO, 37%) in MeCN with phenol at -1.4 V vs. SCE, which improved to 70% under visible light irradiation (λ > 420 nm) by alleviating CO product inhibition[158,159]. A phenanthroline-derived iron complex exhibited low selectivity under diverse conditions in DMF or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), producing a mixture of CO, formate, oxalate, and H2 with only a slight bias toward formate[160]. These results highlight the importance of product release kinetics and ligand environment in controlling both efficiency and selectivity in non-porphyrinic aromatic iron CO2 reduction catalysts. Pyridine-imine complex iron complex stands out for its high selectivity toward formate, delivering FE of HCOOH (FEHCOOH, 75%-80%) in DMF at -1.25 V vs. SCE with no detectable CO or H2[129]. Density functional theory (DFT) studies suggest initial C-bound CO2 coordination, followed by isomerization to an O-bound intermediate due to insufficient Fe3+-π back-bonding into the CO2 π* orbitals for C-O bond cleavage, ultimately leading to HCOOH via O-bound pathways[129]. Notably, proton donors such as H2O or phenol do not affect performance, indicating that formate formation proceeds without classical metal-hydride intermediates typically implicated[129]. This mechanistic distinction underscores the diverse reactivity patterns accessible to iron-based CO2 reduction catalysts depending on ligand design.

Moreover, Fe-based CO2 reduction catalysts, particularly Fe-porphyrins, phthalocyanines, and corroles, exhibit strong UV-vis absorption, enabling them to function as both light absorbers and catalysts for photocatalytic CO2 reduction[161-165]. In the absence of PSs, direct UV irradiation of Fe-based CO2 reduction catalysts in the presence of sacrificial electron donors such as triethylamine can produce CO, though often with limited selectivity and accompanied by porphyrin degradation at high-energy wavelengths[162,163]. Incorporating PSs responsive to visible light significantly enhances activity, rate, and selectivity, allowing operation under λ > 400-460 nm and even in aqueous media[164]. Ligand variation (e.g., qpy, 1,10-phenanthroline, cyclopentadienone) further tunes performance, with some systems achieving exceptionally high CO TONs (TONCO > 3000) and high selectivity under precious-metal-free conditions[165]. These findings underscore the versatility of Fe-based CO2 reduction catalysts in photocatalysis, from selective CO production to deeper CO2 reduction into hydrocarbons.

Molecular cobalt CO2 reduction catalysts, typically featuring N4-donor or macrocyclic ligand scaffolds, operate predominantly through a Co+ active state, often with ligand noninnocence contributing to reactivity[166-171]. Early systems such as phthalocyanines and porphyrins displayed CO2 reduction in aqueous or mixed solvents, producing CO, H2, and HCOOH, while tetraazamacrocycles achieved higher CO selectivity via Co+(L•-) ligand-radical species that bind and activate CO2 through H-bonding[166-171]. Ligand architecture strongly influences selectivity and stability, forming Co0 as the active species, others exhibiting unusual side-on CO2 binding facilitated by coordinated halides, and pendant amines enabling highly selective HCOOH formation (FE = 98%) via internal proton relays and hydride-mediated nucleophilic attack[168,169]. In photocatalysis, product distribution and efficiency are likewise governed by PS choice, ligand design, and secondary sphere effects[170]. Early combinations of CoCl2 or macrocycles with Ru- or organic-based PSs yielded mixed CO and HCOOH products, with selectivity influenced by hydride pathways or direct CO2 binding to Co+(L•-) species[170]. Structural modifications, including pendant amines, halide ligands, and expanded macrocycles, have delivered TONCO values exceeding 2400 with > 95% CO selectivity, while corroles, porphyrins, and corrins exhibit distinct mechanistic profiles[170]. Notably, cooperative binuclear systems achieve exceptional performance (TONCO = 8448, 98% selectivity) via dual-site CO2 activation within a cryptand cavity, illustrating the potential of biomimetic multi-site designs[171]. Overall, both electro- and photocatalytic studies underscore the pivotal role of ligand architecture, secondary sphere interactions, axial coordination, and PS catalyst pairing in tuning the reactivity, selectivity, and mechanistic pathways of cobalt-based CO2 reduction catalysts.

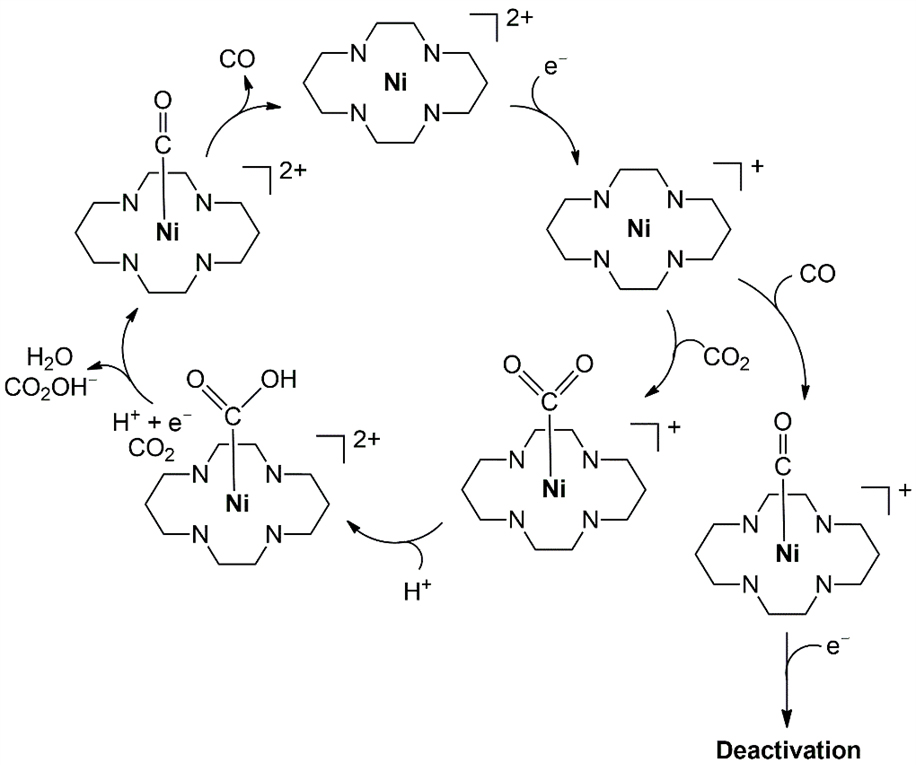

Early studies on electrocatalytic CO2 reduction with nickel complexes, often paralleling cobalt systems, primarily employed macrocyclic N4-donor ligands such as cyclam, which remains a benchmark catalyst, achieving TONCO = 8000 with no H2 formation in aqueous media[172]. [Ni(cyclam)]2+ and its derivatives have demonstrated exceptionally high turnover frequencies on Hg electrodes, thereby overcoming the inherent limitation of poor electrode reactivity commonly observed in first-row transition metal catalysts[172]. As shown in Figure 9, the reaction initiates with the one-electron reduction of the Ni catalyst. The catalytic cycle then proceeds through CO2 binding and protonation steps, followed by the release of H2O, formate, and CO. CO binding can lead to catalyst deactivation, also known as CO poisoning. Notably, Hg electrodes preferentially stabilize the trans-III conformer of [Ni(cyclam)]2+, which binds effectively and weakens the Ni-CO σ interaction, thereby mitigating CO poisoning[172].

Structural variations, including C-alkylation, carboxylate functionalization, and aryl substitution, modulate CO2 binding, CO inhibition, and performance, with subtle ligand changes dramatically altering catalytic outcomes[173-175]. While Ni complex generally favors CO in water, it can produce HCOOH in mixed solvents via O-bound intermediates. Beyond cyclams, Nickel-NHC complexes enable tuning of redox properties and product distributions, though stability and selectivity vary with ligand electronics and donor sets[173-175]. Multinuclear clusters introduce cooperative activation pathways, involving ligand-based reductions and CO2•- intermediates, enabling divergent selectivity toward CO or HCOOH depending on proton availability[173-175]. Across these systems, nickel catalysts demonstrate high activity and selectivity potential, with performance governed by ligand architecture, secondary sphere effects, CO management, and electrode-catalyst interactions.

Photocatalytic CO2 reduction with Ni-based molecular catalysts has been explored using various PSs and catalyst architectures to improve activity and selectivity[176-178]. Early studies with Ru-based PS in aqueous ascorbic acid demonstrated CO formation, though activity was low and often required repeated PS addition. Modification to a smaller-ring analogue enabled bidentate CO2 binding, producing both CO and HCOOH[177,178]. Dyad systems linking PS units to Ni-cyclam cores showed that C-linked designs significantly enhanced CO selectivity (up to 16-fold) and productivity (up to 4.5-fold), likely via reversible electron storage by pyridinium groups[177,178]. Binuclear cyclam complexes also improved performance, achieving 94% CO selectivity[177,178]. Beyond cyclams, in MeCN/Et3N exhibited exceptional TONCO values up to 98,000 under simulated solar light, though efficiency plateaued without PS replenishment[177,178]. These results highlight the potential of ligand engineering, dyad and binuclear strategies, and PS with catalyst matching to advance homogeneous Ni photocatalysts for selective CO2-to-CO conversion, although reliance on precious metal dyes remains a key limitation.

Such research is essential for advancing efficient CO2 reduction technologies, and we are currently conducting systematic studies on Mn-, Fe-, Co-, and Ni-based molecular catalysts bearing anchoring groups for integration into hybrid systems. As shown in Figure 10, these designs aim to promote robust surface attachment, efficient electron transfer, and long-term stability, ultimately enabling the identification and development of the most effective transition metal-based hybrid catalysts with superior activity and selectivity.

IMMOBILIZATION METHODS AND PHOTOELECTROCHEMICAL CO2 REDUCTION PERFORMANCE FOR HYBRID SYSTEM

Hybrid catalysts, in which a molecular catalyst is immobilized onto a heterogeneous support, are emerging as next-generation catalytic systems that combine the advantages of both components[179-182]. Hybrid catalysts can overcome several intrinsic drawbacks of both homogeneous and heterogeneous systems by integrating their respective advantages. Homogeneous catalysts typically exhibit excellent reactivity and selectivity; however, they often suffer from safety issues and challenges in separation and recycling. In contrast, heterogeneous catalysts provide improved stability and ease of separation, yet they generally exhibit lower activity and limited tunability of active sites. To address these issues, hybrid catalysts employ supports such as semiconducting metal oxides or modified silica, which can function as ligands and modulate the electronic properties of the central metal centers, thereby enhancing catalytic activity. While conventional homogeneous catalysts are randomly dispersed in solution, hybrid catalysts are uniformly anchored on well-defined single sites of the support. This configuration allows for a higher degree of structural control and tunability, leading to improved reactivity. Moreover, the stable anchoring of catalytic species prevents degradation or aggregation, resulting in enhanced stability and facile separation and recyclability. Such hybrid systems have demonstrated broad applicability across diverse transformations, including PEC CO2 reduction reactions[179-182]. PEC CO2 reduction, which couples light energy with electrochemical catalysis to produce high-value chemicals such as formate and CO, is attracting significant attention as a sustainable technology. Numerous studies have demonstrated the use of hybrid catalysts formed by immobilizing molecular CO2 reduction catalysts onto heterogeneous supports to evaluate and enhance PEC performance[179-182].

In general, hybrid catalysts are prepared by designing a molecular catalyst containing an anchoring group, followed by covalent attachment to the support surface through an overnight heating process under conditions suitable for the chosen coupling chemistry[82-85,126,183,184]. The immobilization strategy is tailored to the catalyst structure, support surface chemistry, and anchoring group; for instance, alkene-functionalized catalysts can undergo hydrosilylation with H-terminated porous Si (H-porSi) at elevated temperatures, while silatrane-functionalized catalysts can form robust Si-O bonds with SiOx-porSi under milder conditions [Figure 11][126,183]. After immobilization, the resulting hybrid materials are characterized using spectroscopic and microscopic techniques such as FTIR spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), SEM, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to confirm covalent attachment, structural integrity, and surface modifications[126,183]. Ultimately, hybrid catalysts represent a comprehensive system design that addresses not only catalytic activity but also stability, reproducibility, and long-term operational durability. Mn-based molecular catalysts covalently anchored to SiOx-porSi supports have been shown to selectively reduce CO2 to formate under simulated sunlight (1 sun) illumination, initiating catalysis at approximately -1.75 V vs. Ferrocenium/Ferrocene (Fc+/Fc)[126]. In these systems, formate was obtained as the major product with Faradaic efficiencies reaching up to 96% in the early stages, while the formation of competing products such as H2 or CO was negligible[126]. The catalysts maintained stable operation for over 7 h, with more than 90% of the immobilized metal complexes retained on the surface post-reaction[126]. Spectroscopic and microscopic analyses, including FTIR spectroscopy, XPS, SEM, and EDS mapping, confirmed minimal catalyst leaching and preservation of structural integrity, underscoring the robustness of the immobilization strategy[126]. Although a gradual decrease in current density and efficiency was observed over time, potentially due to conversion of surface-bound species into less active forms, the system exhibited superior selectivity, stability, and reproducibility compared with other immobilized catalyst platforms[126]. This observation contrasts with previous studies reporting a decline in catalytic activity when catalysts are anchored onto support surfaces[185]. Such deactivation is often attributed to ligand dissociation or exchange processes, which alter the electronic properties of the central metal center and consequently reduce catalytic performance[185]. For instance, a hydrogen ligand that typically acts as an electron donor can detach from the metal center upon surface anchoring, as the acidic protons on the support surface react with the hydrogen ligand, ultimately leading to catalyst deactivation[185]. To mitigate such deactivation pathways, future hybrid catalyst designs should emphasize anchoring strategies that preserve the primary coordination sphere of the metal center while electronically decoupling acidic surface functionalities through robust linkers or protective interfacial layers.

Figure 11. Preparation and characterization of Mn catalyst immobilized SiOx-porSi[126]. (A) Scheme of immobilizing Mn catalyst onto SiOx-porSi using thermal oxidation; (B) FTIR spectra showing the conversion of SiOx-porSi to Mn catalyst immobilized on SiOx-porSi; (C and D) XPS spectra of intact and powdered samples of Mn catalyst immobilized on SiOx-porSi in the Mn 2p and Si 2p region; (E) Cross-sectional SEM image and EDS mapping for Si and O of Mn catalyst immobilized on SiOx-porSi. Reprinted with permission from Ref.[126]. Copyright © 2025, Elsevier. FTIR: Fourier transform infrared; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; EDS: energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.

In addition, amino acid-modified Cu electrodes exhibit enhanced selectivity for the electrochemical reduction of CO2 to hydrocarbons, with catalysis initiated near -1.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl[186]. Amino acid-modified Cu electrodes were fabricated by immobilizing amino acid molecules onto Cu nanowire films to construct an organic-inorganic interface for CO2 electroreduction[186]. Cu nanowires were first synthesized via chemical oxidation of electropolished Cu foil in an alkaline NaOH/K2S2O8 solution, followed by electroreduction in 0.1 M KHCO3 to produce a clean metallic Cu surface[186]. Amino acids were then immobilized by drop-casting their aqueous solutions (0.1-10 mM) onto both sides of the Cu nanowire film and drying under N2 flow after a 15 min adsorption period[186]. The amino acids anchored through -COOH and -NH2 groups, forming a zwitterionic interfacial layer that served as a stable heterogeneous support and enabled selective CO2-to-hydrocarbon conversion under electrochemical conditions[186]. For example, glycine-modified Cu nanowires achieved total hydrocarbon FE of up to 34.1%, nearly double that of bare Cu electrodes (17.8%), with C2 products such as C2H4, C2H6 dominating, trace C3H6 formation, and strongly suppressed H2 evolution[186]. FEs of CO2 reduction products, including FECO, FEH2, and FEHCOOH, were systematically assessed alongside corresponding homogeneous modifiers, heterogeneous Cu supports, and operating conditions. At -1.9 V in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3, glycine modification reduced FEH2 from > 70% to < 55% and slightly increased FEHCOOH (10%), while hydrocarbon generation was maximized[186]. Stability tests confirmed robust performance for more than 6 h and selectivity for more than 12 h[186]. Structural and surface analyses indicated durable amino acid adsorption and preserved electrode integrity, while DFT revealed that zwitterionic glycine stabilizes the CHO* intermediate via -NH3+ interactions, providing a mechanistic rationale for enhanced hydrocarbon selectivity[186]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that amino acids are powerful molecular regulators for efficient and durable conversion from electrochemical CO2 to hydrocarbons.

Co tetraphenylporphyrin (CoTPP) was covalently bonded to carbon cloth via a phenylene linker through electroreduction, yielding enhanced activity. The CoTPP catalyst system was synthesized by covalently anchoring CoTPP onto a carbon cloth support through electrochemical reduction of in situ-generated diazonium intermediates[187-191]. The carbon cloth, serving as a conductive substrate, was pre-cleaned with concentrated HCl, trifluoroacetic acid, and deionized water[187]. The amine-functionalized porphyrin precursor (TPP-NH2) was diazotized in a cold H2O/trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) mixture at -5 °C using NaNO2 to form the corresponding diazonium salt[187]. Subsequent electroreduction at 0.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 1 min enabled covalent grafting of phenylene-linked porphyrin moieties onto the carbon surface[187]. Metallation with Co(OAc)2 (OAc = acetate group) in a DMF/CH3COOH (9:1) solution at 120 °C afforded the CoTPP-carbon cloth hybrid[192-194]. This covalent molecular wiring between the macrocyclic catalyst and the carbon support provided efficient electronic coupling and excellent stability under CO2 electroreduction conditions[187]. At -1.05 V vs. Normal Hydrogen Electrode (NHE) in a neutral aqueous electrolyte, CO formation occurs with a turnover frequency (TOF) of 8.3 s-1, which is higher than that of the noncovalent counterpart (4.5 s-1)[187]. The covalent linkage increased the surface density of electrochemically active species by a factor of 2.4, with the maximum FECO attained within 50 mV of the negative potential. The catalyst achieved a TON of 3.9 × 105 in 24 h, threefold higher than that of the drop-cast analogue. Product distribution revealed predominant CO formation (FECO = 67%-81%), while H2 was the major byproduct (FEH2 = 20%-30%), and formate generation was negligible (FEHCOOH < 1%)[187]. Comparative studies with other heterogeneous supports and corresponding homogeneous catalysts confirm that covalent bonding systems not only enhance TOF but also shift the potential required for maximum CO selectivity[195,196]. Furthermore, the electrodynamic analysis showed that the importance of efficient electron transfer to the porphyrin, with conductive linkages playing a pivotal role in the design of high-performance heterogeneous catalysts[197,198].

As another example, iron porphyrin pyridine (Fe-TPPy) catalysts were designed to electrocatalytically reduce CO2 to CH4 and CO in aqueous solution[199]. The Fe-TPPy catalyst system was prepared by immobilizing Fe-TPPy complexes onto multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) to create a conductive molecular-nanocarbon interface for CO2 electroreduction[199]. The porphyrin catalyst and MWCNTs were dispersed in DMF to form a uniform 1:1 suspension, and ~10 µL of the mixture was drop-cast onto a glassy carbon electrode[199]. Upon drying, the Fe-TPPy molecules were immobilized on the CNT walls through strong π-π stacking between the aromatic macrocycles and the sp2-carbon surface, as confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and XPS analysis[199]. This non-covalent anchoring ensured efficient charge transfer and high catalyst accessibility, yielding a stable hybrid electrode with significantly enhanced CO2-to-CO and CH4 conversion efficiencies compared to the homogeneous system[199]. Tuning Fe-TPPy with anisole substituents improved catalytic efficiency up to 76% with a current density of -1.3 mA/cm2 and a TOF of 1 s-1[199]. Under homogeneous conditions at -1.4 V vs. Reversible Hydrogen Electrode (RHE), product selectivity was dominated by CO (FE = 56%) and CH4 (FE = 20%), with H2 accounting for 20%-25% and HCOOH detected only in trace amounts < 5%[199]. Immobilization of Fe-TPPy onto CNTs further enhanced the FE to 92% with a current density of -30 mA/cm2 and a TOF of 4-5 s-1 at -0.6 V vs. RHE[199]. In the heterogeneous state, Fe-TPPy/CNT delivered CO (FE = 50%) and CH4 (FE = 41%) as the dominant products, with minimal H2

Amine-functionalized Pb electrodes were fabricated by electrochemical diazonium grafting of aryl-aliphatic amines onto Pb surfaces, enabling selective CO2-to-formate conversion in 1.0 M KHCO3 electrolyte[200]. Pb foils were first electropolished in a mixed acidic solution of H2O2, HNO3, acetic acid, and ethanol to remove surface oxides and ensure uniform activation[200]. Aromatic amines, including 4-aminobenzylamine (4-ABA), 3-aminobenzylamine (3-ABA), 4-(2-aminoethyl)aniline (AEA), and 4-nitrobenzylamine (NB), were then diazotized with sodium nitrite under acidic conditions to form reactive intermediates[200]. The resulting diazonium species were electrochemically reduced on the Pb surface, producing robust Pb-C covalent bonds and thin polyarylene films with coverages of ~107 mol cm-2[200]. This covalent anchoring created a stable, hydrophilic interface that electronically coupled the organic layer with the metallic substrate, providing a durable heterogeneous platform for CO2 electroreduction[200]. Product analysis revealed that only formate and H2 were detected, with no CO formation observed. The Pb/4-ABA system achieved a maximum FE of 94% for formate at -1.09 V vs. RHE, with the remaining FE (6%) corresponding to H2[200]. On the other hand, the bare Pb electrode produced only about 8%-10% FE for formate under the same conditions, with H2 being the dominant product (> 90%)[200]. Through electrolysis extended for 11 h, stable performance of FEHCOOH consistently above 90% and FEH2 below 10%, with no CO formation[200]. The Pb/4-ABA system also showed high activity, reaching a partial current density of 24 mA cm-2 at -1.29 V, alongside robust long-term stability[200]. SEM, XPS, and contact angle analysis confirmed the presence of polyarylene film

The electrochemical reduction of CO2 was investigated on Au surfaces functionalized with 2-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA), 4-pyridinylethanemercaptan (4-PEM), and cysteamine (CYS)[201]. Hybrid Au electrodes were fabricated by self-assembling thiol-terminated ligands onto polycrystalline Au surfaces[201]. Clean Au foils (99.99%) were rinsed with deionized water and immersed for 5-10 min in 20 mM ethanolic, aqueous, or methanolic solutions of MPA, 4-PEM, or CYS, respectively[201]. The sulfur headgroups formed strong Au-S covalent bonds, producing compact monolayers of the corresponding ligands[201]. After functionalization, the electrodes were rinsed thoroughly to remove loosely bound species[201]. This simple self-assembly process created well-defined organic-metal interfaces, where the functional groups (-COOH, pyridyl, or -NH2) mediated local proton transfer, while the Au substrate ensured high conductivity and catalytic stability during CO2 electroreduction[201]. The Au electrodes modified with 4-PEM exhibited a 2-fold increase in FE and a 3-fold increase in formate production compared to Au foil, resulting in a maximum FE of about 21% of formate (vs. 11% in bare Au), while inhibiting CO selectivity (20%) and shifting H2 evolution to a low potential[201]. In contrast, MPA-modified electrodes showed nearly 100% FE for hydrogen evolution, with CO and formate suppressed to below 20% and 5%, respectively[201]. CYS-modified electrodes exhibited 2-fold increases in both CO and H2 partial current densities, maintaining selectivities similar to bare Au (FECO = 40%, FEH2 = 50%, FEHCOOH = 10%)[201]. These results clearly demonstrated that the pKa of the tethered ligand governs product distribution via a proton-induced desorption mechanism. In this context, the molecular ligands act analogously to homogeneous catalysts, while the underlying Au surface provides the heterogeneous support for electron transfer. The reaction was conducted in a CO2-saturated 0.10 M KHCO3 electrolyte (pH ≈ 6.8) using polycrystalline Au foil electrodes functionalized with self-assembled thiol monolayers at applied potentials ranging from -0.5 to -1.1 V vs. RHE[201].

Moreover, NHC-functionalized Au nanoparticles (NPs) were investigated with heterogeneous electrocatalysts, and free carbene and molecular Au-carbene complexes had minimal CO2 reduction activity as homogeneous controls[202]. The hybrid catalyst was synthesized by decorating Au NPs with NHC ligands to create a molecularly tunable Au surface for CO2 electroreduction[202]. Oleylamine-capped Au NPs were first prepared through thermal reduction of Au acetate in 1-octadecene containing oleylamine, oleic acid, and 1,2-hexadecanediol under a N2 atmosphere at 200 °C[202]. Subsequent ligand exchange with 1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene (Cb) in anhydrous toluene afforded NHC-functionalized Au-Cb NPs[202]. The carbene ligands formed strong σ-donating Au-C bonds, yielding a stable organometallic interface that preserved the NP morphology (~7 nm) while tuning the surface electronic environment for efficient CO2 conversion[202]. Electrolysis was carried out in CO2-saturated 0.10 M KHCO3 at neutral pH[202]. For the carbene-functionalized Au NP, the FE for CO reached 83 % at an overpotential of 0.46 V, whereas the parent Au NP gave only 53 % under the same conditions. Concurrently, H2 evolution was suppressed to 13 % at -0.75 V, and HCOOH was detected only in trace amounts below 1%[202]. These results highlighted that molecular surface functionalization of Au NPs tuned the product distribution and reduced the energy requirements, providing a complementary strategy for the design of heterogeneous CO2 reduction catalysts[202].

Another representative hybrid catalyst, cobalt meso-tetraphenylporphyrin (CoTPP), was studied as a molecular catalyst for CO2 electroreduction[195]. The CoTPP system was prepared by immobilizing cobalt CoTPP onto CNTs through non-covalent π-π interactions. The suspension of CoTPP and CNTs in DMF was sonicated to achieve uniform dispersion, then drop-cast onto a glassy carbon electrode. After solvent evaporation, a porous and homogeneous CoTPP-CNT film was obtained with a surface loading of

Beyond conventional immobilization strategies, increasing attention has been devoted to surface modification, plasmonic enhancement, and hybrid interface engineering as effective means to regulate interfacial charge transfer, light-matter interactions, and catalytic stability[203-206]. Recent studies on noble metal NPs illustrate that functional organic layers can precisely define organic-inorganic interfaces, stabilizing colloidal systems while simultaneously tuning surface plasmon resonance and plasmon-enhanced optical responses, thereby actively governing interfacial energy and charge transfer rather than serving as passive capping agents[206]. Consistent with this perspective, recent reports demonstrate that deliberate control over metal-support interactions and hybrid interfaces. Ranging from geometrically defined molecular-solid coupling and redox-active hydrogel matrices to anchoring of single metal atoms, can profoundly alter catalytic activity, durability, and reaction pathways in water oxidation and electrolysis systems, underscoring the central role of interfacial engineering in next-generation hybrid catalytic platforms[203-205].

In addition, recent studies on mixed-metal oxides demonstrate that rationally engineered semiconductor heterostructures can substantially enhance charge-separation efficiency and overall catalytic activity. For example, NiO-ZnO nanocomposites synthesized via a sol-gel method form an efficient p-n heterojunction that promotes rapid electron-hole separation under UV irradiation[207]. Structural analyses reveal the coexistence of cubic NiO and hexagonal ZnO phases embedded within an interconnected mesoporous microstructure, while Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) measurements indicate a relatively high surface area that facilitates interfacial charge transfer[207]. Importantly, the reduced band gap of 2.95 eV and the presence of non-stoichiometric defect states further enhance light absorption and suppress charge recombination, collectively leading to markedly improved photocatalytic performance[207]. As a result, the material achieves up to 98% photocatalytic degradation efficiency toward crystal violet dye[207]. These results underscore how band alignment, defect engineering, and microstructural control act synergistically to regulate charge dynamics, providing valuable design principles for mixed-metal-oxide-based hybrid PEC CO2 reduction systems.

Table 2 summarizes the FEs of products generated from CO2 reduction reactions, along with the corresponding homogeneous catalysts, heterogeneous supports, and reaction conditions. Such hybrid catalyst systems, which merge the finely tunable reactivity of molecular catalysts with the physical stability of solid supports, are emerging as promising candidates for next-generation PEC CO2 reduction. They offer a versatile platform for achieving high selectivity and efficiency in complex multi-electron reactions, including CO2 reduction, H2 evolution, and N2 fixation. Future advances in hybrid catalyst development will rely on targeted incorporation of functional anchoring groups, diversification of support materials, precise control over porosity and morphology, integration of photoactive components, and rigorous quantitative characterization. Future development of hybrid catalysts should move beyond empirical optimization toward hypothesis-driven interfacial design. Anchoring groups and interlayers need to be regarded as electronic ligands that deliberately control band alignment, dipole moments, and inner-sphere electron transfer pathways rather than serving merely as mechanical linkers. To achieve long-term operational stability, advanced operando and spatially resolved techniques, such as X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy, or photoemission electron microscopy (PEEM), should be employed to identify degradation pathways, including ligand dissociation, trap formation, and surface reconstruction under realistic PEC conditions. Establishing standardized benchmarking protocols will enable quantitative comparison across different hybrid platforms such as SiOx-porSi, carbon-based materials, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), or two-dimensional (2D) semiconductor supports. In parallel, computational and experimental feedback loops should be implemented to predict optimal combinations of supports, catalysts, and anchoring groups for selective multi-electron CO2 conversion. Ultimately, the integration of hybrid catalysts with photoactive absorbers and redox mediators is expected to bridge molecular-level precision with device-level scalability, guiding the realization of efficient and durable solar fuel production systems. These strategies are expected to establish hybrid catalysts as a key enabling technology for solar fuel generation, CO2 valorization, and practical hydrogen production in the context of a sustainable, carbon-neutral energy economy. Hybrid catalytic systems are being pursued as a unifying strategy to integrate the molecular precision of homogeneous catalysts with the robustness of heterogeneous platforms, and their continued development will rely on preserving intrinsic molecular reactivity while enabling long-term stability, clear active-site definition, and scalable operation[86].

Faradaic efficiencies (FE), turnover frequencies (TOF), current densities JCO2, and overpotentials (η) of CO2 reduction products using various homogeneous catalysts and heterogeneous supports under specified reaction conditions. (FECO = faradaic efficiency of CO, FEHCOOH = faradaic efficiency of formic acid, FEH2 = faradaic efficiency of H2)

| Homogeneous catalysts | Heterogeneous supports | Reaction conditions | TOF | JCO2 | η | FE of products | Ref. |

| (Rbpy)Mn(CO)3Br (bpy = 2,2’-bipyridine) | SiOx-porSi (oxide-coated porous silicon) | -1.75 V vs. Fc+/Fc; sunlight (1 sun) illumination | 11-23 h-1 | ~0.6 mA cm-2 | ~280 mV | FECO = 0 % FEHCOOH = 96 % FEH2 = 0 % | [126] |

| Cu nanowire film electrode | Amino acid-modified copper electrodes | -1.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl; 0.10 M KHCO3 | - | - | - | FECO = 34.1% FEHCOOH = 10% FEH2 > 70%; < 55% | [170] |

| Co- tetraphenylpor-phyrin (CoTPP) | Carbon cloth | -1.05 V vs. NHE | 4.8-13 s-1 | ~1.5 mA cm-2 | ~500-550 mV | FECO = 67%-81% FEHCOOH < 1% FEH2 = 20-30% | [180] |

| Iron-porphyrin-pyridine (Fe-TPPy) | Carbon nanotube (CNT) | -0.6 V vs. RHE | 4-5 s-1 | ~30 mA cm-2 | - | FECO = 56% FEHCOOH < 2% FEH2 < 8% | [181] |

| Amines | Pb electrodes | -1.09 V vs. RHE; 1.0 M KHCO3 electrolyte | - | ~9.5-24 mA cm-2 | - | FECO = 0% FEHCOOH = 94% FEH2 = 6% | [182] |

| 2-mercaptopropionic acid, 4-pyridinylethanemercaptan, cysteamine | Au electrode | -0.5 to -1.1 V vs. RHE; CO2-saturated 0.10 M KHCO3 electrolyte (pH = 6.8) | - | partial J up to ~4 mA cm-2 | onset potentials (vs. RHE) | FECO ≤ 20% FEHCOOH = 21% | [183] |

| N-heterocyclic carbene | Au nanoparticle | 0.46 V vs. RHE | - | - | ~150 mV (onset), up to ~550 mV | FECO = 83% FEHCOOH < 1% FEH2 = 13% | [184] |

| CoTPP (Cobalt meso-tetraphenylporphyrin) | Carbon nanotubes | -1.35 V vs. SCE | 280 h-1 (max 2.75 s-1) | ~0.6-3.2 mA cm-2 | ~350-550 mV | FECO = 91% FEHCOOH = 0% FEH2 > 90% | [185] |

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

The integration of molecular catalysts with solid-state supports into hybrid PEC systems represents a powerful strategy for advancing CO2 reduction technologies toward practical solar fuel production[19-25,208]. In particular, the use of porSi, especially thermally oxidized SiOx-porSi, as a high surface area, conductive, and chemically versatile platform has enabled the immobilization of transition metal-based molecular catalysts with exceptional stability, selectivity, and reproducibility[126]. By combining the molecular-level tunability of homogeneous catalysts with the robustness, recyclability, and device integration capability of heterogeneous supports, hybrid systems overcome many limitations inherent to purely homogeneous or heterogeneous approaches[38-60,86]. Studies to date have demonstrated that careful selection of anchoring groups, optimization of linker length and electronic properties, and preservation of catalyst integrity during immobilization are critical for achieving high Faradaic efficiencies, low overpotentials, and prolonged operational lifetimes[50,61-64]. Mn-based catalysts, in particular, have shown near quantitative selectivity for formate production under mild PEC conditions, maintaining structural and functional stability over extended reaction times[126]. These findings underscore that covalent immobilization not only prevents catalyst leaching but can also positively influence the reaction microenvironment, enhancing both activity and selectivity.

Looking ahead, the development of hybrid catalysts should extend beyond SiOx-porSi to explore emerging support materials that can further enhance efficiency and operational durability[126]. Graphitic carbon nitride, MOFs, and 2D transition metal dichalcogenides represent particularly promising alternatives due to their strong visible light absorption, tunable band alignment, and high chemical stability in aqueous environments[209-215]. Early demonstrations of Mn- and Fe-based molecular catalysts immobilized on graphitic carbon nitride or MOF scaffolds have already shown markedly improved charge separation, reduced recombination losses, and enhanced product selectivity, providing a concrete experimental foundation for further study. Compared with SiOx-porSi, these supports also offer expanded synthetic tunability and compatibility with large-area or flexible device architectures. However, they often introduce new deactivation pathways arising from strong catalyst-support interactions, including ligand exchange and electronic perturbations that compromise molecular integrity. Addressing these challenges requires interface designs that preserve the primary coordination sphere of molecular catalysts while minimizing deleterious surface-induced effects, such that intrinsic molecular reactivity can be recovered without sacrificing the stability and reproducibility required for scalable hybrid catalysis.

Future research should prioritize systematic, quantitative comparisons of catalyst-support interfaces to elucidate the correlations among surface composition, charge-transfer kinetics, and catalytic selectivity. Operando spectroelectrochemical analyses, including transient absorption spectroscopy, XAS, and surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS), will be critical to reveal intermediate structures and reaction dynamics under working conditions. In parallel, computational co-design frameworks integrating DFT modeling with targeted synthesis can accelerate the discovery of optimal catalyst-support combinations. The implementation of multi-site anchoring, hydrophobic passivation layers, and tailored porous architectures should further enhance stability and suppress degradation pathways under continuous illumination and bias.

By integrating these complementary strategies, hybrid catalyst platforms can evolve into scalable, durable, and high-performance systems for solar-driven CO2 reduction and other multi-electron transformations such as water splitting and nitrogen fixation. Ultimately, advancing this field will require not only the design of robust molecular-material interfaces but also the convergence of synthetic chemistry, materials science, and device engineering to enable efficient, long-term, and economically viable solar-to-fuel conversion technologies.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Supervision, conceptualization, writing - original draft & review: Hong, Y. H.

Investigation, writing, formal analysis, visualization - editing & review: Lee, S.; Lee, D. H.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work at Sogang University was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) through the G-LAMP program funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Education, RS-2024-00441954). The study was also supported by the NRF Young Investigator Program (Seed Research) funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT, RS-2025-23524428). Additionally, this work received support from the Sogang University Research Grant of 2024 (202410026.01).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

2. Woolerton, T. W.; Sheard, S.; Chaudhary, Y. S.; Armstrong, F. A. Enzymes and bio-inspired electrocatalysts in solar fuel devices. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 7470.

3. Benson, E. E.; Kubiak, C. P.; Sathrum, A. J.; Smieja, J. M. Electrocatalytic and homogeneous approaches to conversion of CO2 to liquid fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 89-99.