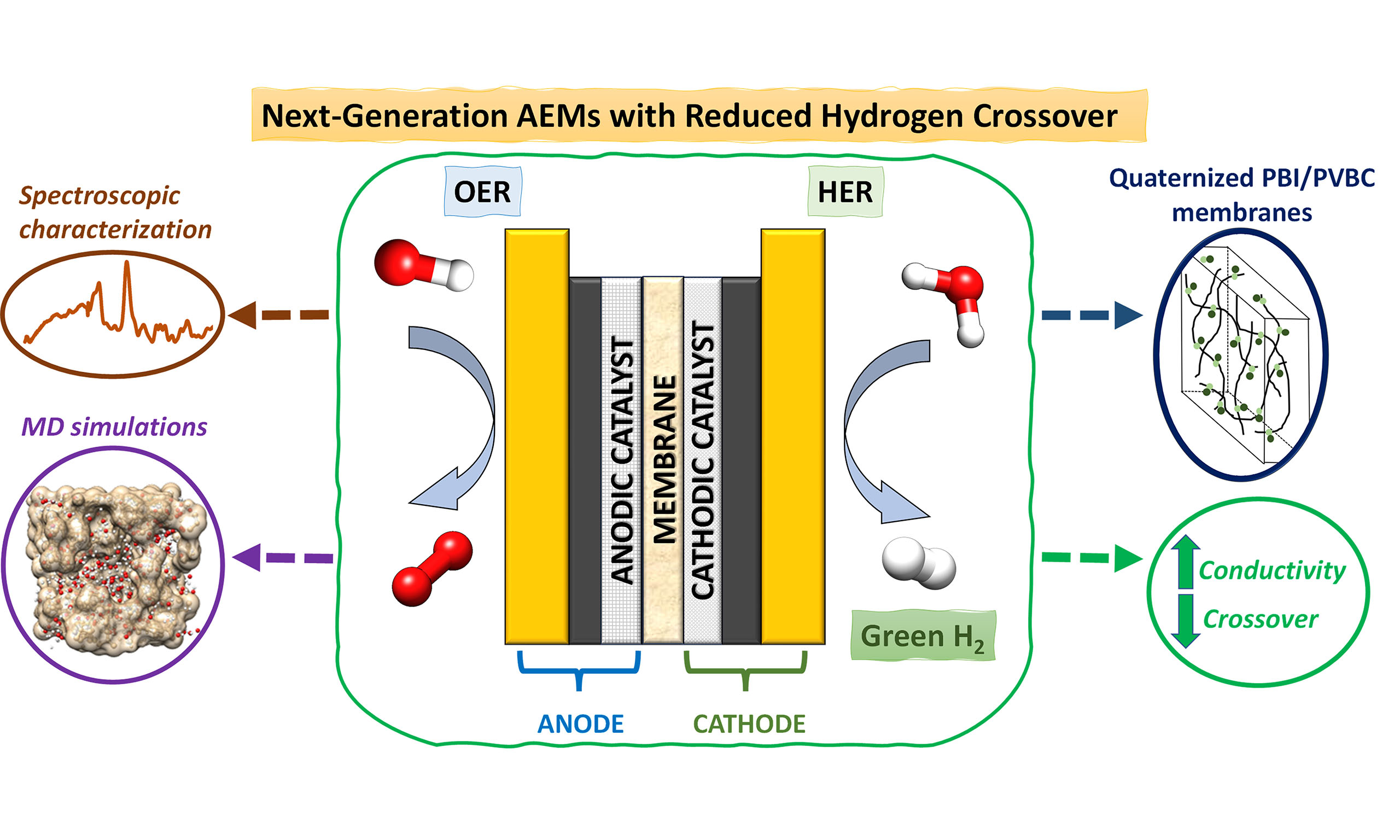

Advancing green hydrogen: next-generation AEMs with reduced hydrogen crossover

Abstract

This study reports the synthesis and characterization of anion exchange membranes (AEMs) tailored for application in alkaline water electrolysis for green hydrogen production. Novel membranes were developed by crosslinking polybenzimidazole (PBI) and poly(vinylbenzyl chloride) (PVBC) in a 1:2 ratio, followed by quaternization with either 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO) or 1-methylpyrrolidine (MPY). Their performance was benchmarked against commercial membranes, including Fumasep® FAA-3-50 and Dapozol M-40. The membranes were thoroughly characterized by scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, infrared and Raman spectroscopies, ionic conductivity, ion exchange capacity, water uptake and swelling measurements. Additionally, molecular dynamics simulations were performed to determine the diffusion coefficients of OH- and H2, providing further insight into ion transport and gas permeability at the molecular level. Electrochemical performance was evaluated in a flow-cell configuration under different pretreatment protocols. A key result of this work is the superior gas-barrier performance of the synthesized membranes. In stability electrolysis tests, both DABCO- and MPY-based membranes showed significantly reduced hydrogen crossover, 36% lower than FAA-3-50, decreasing from approximately 2.7% to just 1.7% H2 detected at the anode. This reduction in crossover is critical for enhancing efficiency and safety in hydrogen production. While FAA-3-50 delivered the best overall performance in short test activation conditions, the synthesized membranes demonstrated highly competitive performance and notable improvements in selectivity and stability. Dapozol M-40 was excluded from further analysis due to its poor electrochemical performance. These findings confirm the potential of tailored PBI/PVBC-based membranes for advanced alkaline electrolysis applications.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In light of the increasing evidence of climate change, there is an urgent imperative to transition toward a more environmentally responsible society, where the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants is paramount. Consequently, much of current research is focused on the development of cleaner, more sustainable energy sources grounded in the principles of the circular economy, progressively shifting from fossil fuels toward renewable alternatives[1,2]. In this context, hydrogen has emerged as a promising energy vector due to its versatility in both energy production and storage[3].

Among the prominent H2 technologies developed in recent years, alkaline water electrolysis (AWE) is of much importance for the production of high-purity hydrogen without emissions. When energy demand arises, this hydrogen can be fed into an H2/O2 fuel cell to generate electricity and water. The reactions in alkaline electrolyzers are as follows:[4]

Alkaline electrolyzers exist mainly in two configurations: conventional systems using porous diaphragms and anion exchange membrane water electrolyzers (AEMWE). Although proton exchange membrane electrolyzers (PEMWE) offer high conductivity and stability, their dependence on noble-metal catalysts such as iridium makes them costly[4,5]. AEMs, in contrast, enable the use of inexpensive catalysts such as nickel, stainless steel, and Ni-Fe alloys[6-9]. Recent approaches even employ lignin-assisted AEMWE to enhance hydrogen production[10]. Despite these advances, alkaline systems still operate at moderate efficiencies (~60%), lower than those of acidic or solid oxide electrolyzers (SOECs)[11]. Thus, current efforts focus on improving performance through emerging electrolysis, photoelectrochemical, and photocatalytic methods[12,13], as well as novel materials such as high-entropy oxides (HEOs) and high-current-density electrocatalysts (> 200 mA cm-2) that optimize charge transfer and surface reactivity for efficient water splitting[14,15].

Apart from the intense development of catalysts for AEMWE[4-6], anion exchange membranes (AEMs) are the other key component that has attracted great interest. Recent advances in AEMs have significantly enhanced the feasibility of polymer electrolyte alkaline water electrolysis (AEMWE). Considerable research efforts have focused on developing chemically stable cationic groups and robust polymer backbones to improve conductivity and durability under alkaline conditions. For instance, Xu et al. reported poly(m-terphenyl piperidinium) N-tethered with both nonionic hexyl chains and hexyl chains with terminal piperidinium cations AEMs with hydroxide conductivities exceeding 100 mS·cm-1 at 80 °C, achieving current densities above 0.75 A·cm-2 in AEMWE tests[7]. Similarly, Li and co-workers developed membranes based on PVBC-MPy and PSF, using bifunctional tertiary amines as crosslinking agents, which demonstrated high dimensional stability and supported current densities of 600 mA·cm-2 at 80 °C with excellent stability over time[8]. Recent advances in poly(aryl piperidinium) (PAP)-based AEMs have demonstrated significant potential for water electrolysis, achieving high ionic conductivities and improved stability. Caielli et al.[9] developed poly(biphenyl piperidinium) (PBP) membranes with a high hydroxide conductivity of

Commercial membranes have also been evaluated: Specifically, Fumasep® FAA-3-50 (FUMATECH BWT GmbH, Germany) has been widely applied as a benchmark, typically showing hydroxide conductivities in the range of 20-40 mS·cm-1 and current densities around 0.5-0.8 A·cm-2, but with limited chemical stability in long-term operation[15]. More recently, Sustainion® membranes (Dioxide Materials, Boca Raton, FL, USA) incorporating tethered imidazolium cations have demonstrated both high conductivity (> 80 mS·cm-1) and remarkable alkaline stability, with operation at 1 A·cm-2 and 1.85 V for over 10,000 h[16]. These examples highlight the rapid progress in AEM design and underscore the potential of polymer electrolyte alkaline electrolysis to provide efficient and durable hydrogen production under environmentally benign operating conditions.

In this work, the electrode configuration consisted of a Pt/C-coated carbon cloth anode and a compressed nickel foam cathode. Although Pt is not the most active catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) compared with Ir-, Ru-, or NiFe-based materials, it remains a well-established and stable benchmark electrode frequently used in alkaline and AEM water electrolysis studies for controlled electrochemical assessments[17]. Nickel foam, on the other hand, is widely recognized as an efficient cathode for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) in alkaline media due to its high conductivity, surface area, and mechanical robustness[18,19]. This electrode configuration provides a reliable and reproducible electrochemical platform to evaluate membrane performance without the additional complexity of catalyst optimization. Moreover, some studies have explored the use of Ni catalysts in AEM electrolysis systems. Coppola et al.[20] employed a Ni foam catalyst as both anode and cathode in an AEM water electrolyzer, achieving good catalytic activity and stability under alkaline conditions. This work highlights the promise of Ni-based catalysts as robust, noble-metal-free alternatives for alkaline AEM electrolysis.

The study of hydroxide (OH-) transport in AEMs involves both vehicular and Grotthuss (structural) diffusion mechanisms[21,22]. Vehicular diffusion describes the physical movement of OH- through the media, while Grotthuss diffusion involves a proton transfer via hydrogen bond rearrangements. Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with non-reactive force fields efficiently model large systems (≫104 atoms) but only capture vehicular diffusion, often underestimating OH- transport[23,24]. Ab initio MD (AIMD) provides an accurate description of proton transfer[25,26] but is limited to small systems (~102 atoms), making nanoscale simulations impractical.

To bridge this gap, reactive force fields such as reactive force field (ReaxFF)[27] offer a practical alternative, allowing the simultaneous description of chemical reactions, water dissociation, and structural migration of OH- and H3O+[28-30]. ReaxFF has been successfully applied to model transport in polymer membranes and other complex chemical systems[31], making it suitable for larger-scale simulations. In this work, reactive MD simulations using ReaxFF were employed to complement the experimental investigation of OH- transport in AEMs, providing molecular-level insight into ion mobility and its relation to macroscopic properties such as conductivity and gas crossover.

Building on this framework, we focus on the synthesis, characterization and testing of novel AEMs, specifically developed for application in alkaline water electrolysis. The synthesis consists of polymer crosslinking and solvent casting methods, approaches validated in numerous studies[32], followed by quaternization to introduce fixed quaternary ammonium groups, a widely adopted strategy in membrane preparation[33]. The synthesized membranes were then tested and characterized in alkaline electrolyzers alongside commercial counterparts. The membranes were prepared by blending polybenzimidazole (PBI) and poly(vinylbenzyl chloride) (PVBC) in a 1:2 ratio, followed by quaternization with either 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO) or 1-methylpyrrolidine (MPY). Their physicochemical and electrochemical properties were benchmarked against commercial membranes, specifically Fumasep® FAA-3-50 and Dapozol® M-40 (Danish Power Systems, Denmark). Characterization was conducted through a combination of scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX), infrared (IR), and Raman spectroscopies, ionic conductivity measurements, and flow-cell electrolysis tests under various pretreatment protocols. Particular attention was devoted to evaluating H2 crossover and gas composition in the anode and cathode, as these are critical for both efficiency and safety in green hydrogen production. In parallel, MD simulations were performed to investigate the diffusion processes of OH- and H2 within the DABCO- and MPY-based membranes at different temperatures. Since simulating the full electrolysis cell is not feasible at the molecular level, smaller and structurally relevant regions were selected to capture the key interactions. This computational analysis provided valuable insight into how the quaternary ammonium groups modulate the mobility of OH- and H2, directly linking molecular-scale transport with macroscopic properties such as ionic conductivity and H2 crossover. Taken together, the combined experimental and computational results highlight the potential of PBI/PVBC-based membranes to deliver competitive electrochemical performance while significantly improving selectivity and stability, positioning them as promising candidates for next-generation alkaline water electrolysis systems.

EXPERIMENTAL AND COMPUTATIONAL DETAILS

Reagents and synthesis procedure of the membranes

All chemical reagents were used as received without further purification. The membrane synthesis was carried out using commercial meta-PBI powder (Between Lizenz GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany;

The crosslinked membranes were synthesized via polymer solution blending followed by a controlled-temperature crosslinking and casting procedure. Initially, a 3.5 wt.% solution of PBI in DMAc was prepared. PVBC was added to this solution to achieve PBI-to-PVBC with molar ratios of 1:2. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 6 h in a sealed glass vial under dry conditions to promote crosslinking. The resulting homogeneous solution was cast into Petri dishes and placed in a vacuum oven (Memert VO200) at 40 °C and 100 mbar for 24 h to remove the solvent, yielding flexible crosslinked PBI/PVBC membranes.

Quaternization was performed using two different agents. For DABCO-functionalized membranes, the PBI/PVBC films were immersed in a 0.5 M solution of DABCO in ethanol and maintained at 60 °C for 72 h, resulting in membranes designated as “DABCO-based membranes”, with chloride as the counterion[34]. A scheme of the process is presented in Supplementary Figure 1. Alternatively, MPY quaternization was carried out using a 50% v/v aqueous solution of MPY, with membranes submerged for 16 h at 50 °C to obtain “MPY-based membranes”[35]. Membranes were stored in ultrapure water until use.

Membranes characterization

SEM/EDX and physico-chemical properties

Morphological characterization of the membrane surfaces was performed using a Hitachi S-3000N scanning electron microscope (SEM). To ensure adequate conductivity, samples were pre-coated with a thin gold layer using a Q150T-S Quorum sputter coater system (Quorum Technologies). The SEM operated under high vacuum conditions with an accelerating voltage of 20 keV and a working distance of 15.0 mm. Elemental composition analysis was conducted via energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) using an XFlash® 6130 detector (Bruker). Quantitative EDX analysis was performed using internal standards to ensure accuracy in elemental quantification.

The ion exchange capacity (IEC) of the membranes was determined through acid-base titration. In the same process, the water uptake (WU) and swelling of the membranes were obtained. Samples were first dried to constant weight (W0) in a vacuum oven at 40 °C and 100 mbar. The dried membranes were measured (length, width and thickness; L0, D0 and T0, respectively) and subsequently hydrated by immersion in ultrapure water for 24 h at room temperature. Then the membranes were weighed and measured again, obtaining the Wh, Lh, Dh and Th for the hydrated values. To ensure complete ion exchange of Cl- counterions to OH-, the hydrated membranes were treated with 1 M KOH aqueous solution under renewed cycles

where Ep is the endpoint (mL) of the titration, and W0 stands for the dry weight of the membrane sample (g).

The water uptake WU (%), volume swelling Volume swelling (%), and thickness swelling Thickness swelling (%) were calculated as follows:[34]

where Wh and W0 stand for the hydrated and dry weight of the sample.

where L0, D0 and T0 stand for length, width and thickness of the dried membranes and Lh, Dh and Th for the hydrated membranes.

where Th and T0 stand for the hydrated and dry thickness of the sample.

The through-plane ionic conductivity of the membranes was evaluated via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) across a temperature range of 30-90 °C. Prior to measurements, membrane samples were equilibrated by immersion in 1 M KOH aqueous solution for 24 h. Excess surface electrolyte was carefully removed using laboratory tissue paper. Impedance spectra were acquired using an Autolab PGSTAT 30N potentiostat/galvanostat equipped with a frequency response analyzer (FRA), employing a two-electrode configuration with stainless steel blocking contacts. The applied frequency range was 1 Hz to 100 kHz with a signal amplitude of 10 mV.

The ionic conductivity σ (in S·cm-1) was calculated using[34]

where L represents the membrane thickness (cm), R denotes the membrane resistance (Ω) derived from the high-frequency real-axis intercept of the Nyquist plot, and A is the electrode contact area (cm2). The activation energy (Ea) of the ionic conductivity was calculated from the dependence of ln(σ) vs. 1,000/T as described elsewhere[36].

Mechanical properties

The mechanical properties of the membranes (FAA-3-50, DABCO and MPY) were evaluated by stress-strain tests performed at room temperature (≈27 °C) using a Zwick Z010 universal testing machine (ZwickRoell, Ulm, Germany) equipped with a 200 N static load cell. Dumbbell-shaped specimens (Type 4) were prepared from each membrane in accordance with ISO 37:2011 (Rubber, vulcanized or thermoplastic - Determination of tensile stress-strain properties). The specimens featured a narrow section width of 2.8 ± 0.1 mm and an overall length of 35.0 ± 0.1 mm. At least five samples per membrane were tested at a crosshead speed of

IR spectroscopy and Raman microscopy

IR spectra were acquired using a PerkinElmer® Spectrum Two Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory. Spectra were recorded in absorbance mode over the wavenumber range of 4,000-450 cm-1, with a resolution of 4 cm-1 and 30-50 scans per sample.

For Raman analysis, a Renishaw inVia™ Reflex confocal Raman microscope (Renishaw plc, Wotton-under-Edge, UK) was employed. The system was equipped with two lasers - 532 nm (up to 100 mW) and 785 nm (up to 400 mW) - and a charge-coupled device (CCD) detector. The associated Leica microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) was fitted with 5×, 20×, and 50× objectives. For the samples, the 785 nm laser was used to minimize fluorescence interference, thereby yielding clearer Raman spectra. The acquisition parameters were: 10-20 accumulations (10-20 s each) and a laser power of 0.1%-1% (≈0.4-4 mW), using the 50× objective.

Flow cell set up, electrochemical measurements and product analysis

Electrochemical evaluation was performed using a commercial flow cell (ElectroChem, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA), featuring gold-plated current collectors and two graphite flow-field plates. A defined active area of 2.56 cm2

The anode was prepared via a spray-coating technique, depositing a catalytic ink containing 40 wt.% Pt on carbon (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA) onto a carbon cloth substrate (QUINTECH, Leonberg, Germany). The ink consisted of Pt/C dispersed in a 70% v/v isopropanol-water solution with Nafion® as a binder. A catalyst loading of 0.75 mg Pt·cm-2 was applied. For the cathode, nickel foam was compacted using a hydraulic press under a load of 2 tons for 1 min to ensure optimal contact. See Supplementary Figure 2.

A dual-channel peristaltic pump (Dinko Instruments, Barcelona, Spain) circulated 1 M KOH electrolyte at a constant temperature of 60 °C through both the anode and cathode compartments. Electrolysis experiments were conducted using an Autolab PGSTAT302N potentiostat/galvanostat (Metrohm Autolab B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands). The electrolyte flow rate was maintained at 23 mL·min-1 for all tests. A schematic illustration of the experimental setup is provided in Supplementary Figure 3.

Faradaic efficiencies (FEs) and H2/O2 ratios were calculated from the gas volumes captured at the anodic and cathodic sides, accounting for the H2 crossover discussed in the results section.

Gaseous products were sampled using a 5 mL gas-tight syringe (SGE Analytical Science, Ringwood, Australia) and analyzed via gas chromatography (GC; Varian 3900, Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with a Carboxen-1006 PLOT column. The GC system was coupled to a mass spectrometer (HiCube, Pfeiffer Vacuum GmbH, Asslar, Germany). The GC method utilized argon as the carrier gas with a temperature ramp from 35 °C to 245 °C at 30 °C·min-1 to achieve optimal separation. Detection of H2 in the anodic stream allowed for the calculation of H2 crossover, expressed as the volume percentage of H2 at the anode.

Computational methodology

We have performed MD simulations to investigate the diffusion processes of water, OH- and H2 in the presence of DABCO and MPY-based membranes, which ultimately play a role in explaining the conductivity and H2 crossover. Simulations were conducted using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS, Sandia National Laboratories, NM, USA)[37]. The Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF)[27,28] - a bond-order-based empirical reactive force field - was employed, utilizing the parameters developed by

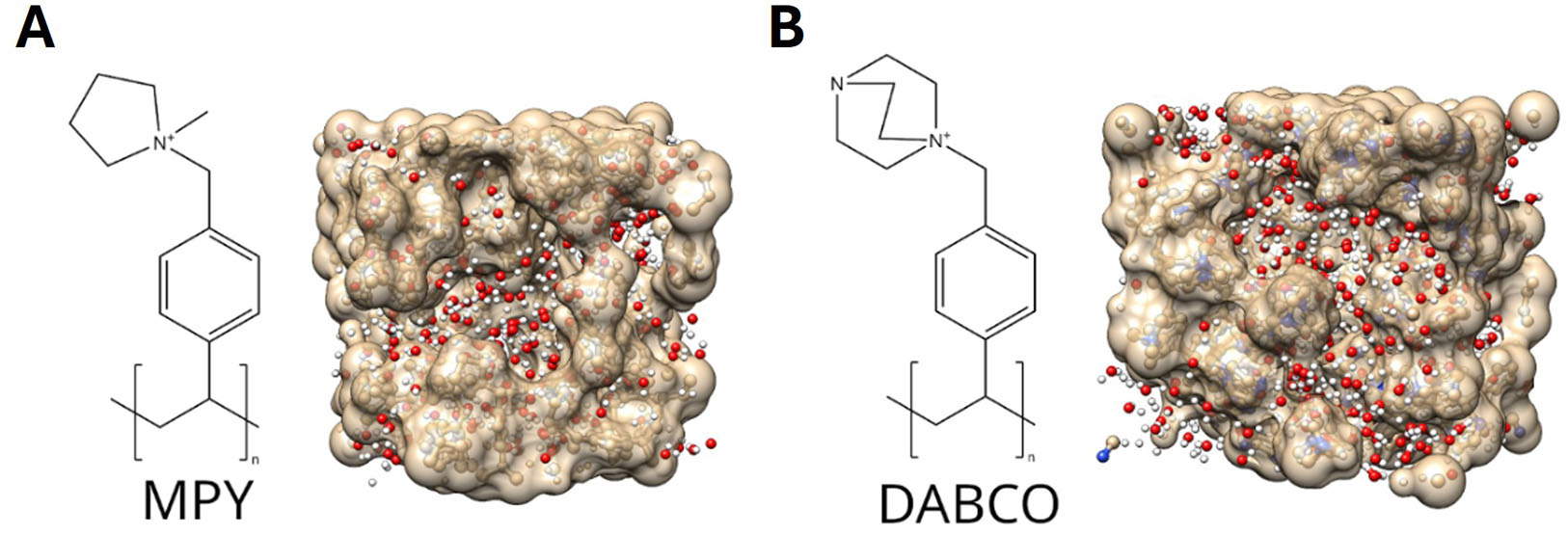

Simulation cells were constructed containing four polymer chains (either DABCO- or MPY-based), with each chain featuring eight quaternary ammonium groups. The initial configurations - comprising 266 water molecules, the four polymer chains, and 20 H2 molecules - were generated using PACKMOL (University of Campinas, Brazil)[39]. These systems were relaxed via eight annealing cycles, following the procedure described in Refs.[23,38], at a temperature of 60 °C. The chemical structures of both polymers and a representative frame of the equilibrated system are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of the repeating units and representative snapshots of the equilibrated systems for (A) MPY and (B) DABCO. In this study, each simulation cell contains four polymer chains (n = 8 repeating units per chain), with the snapshots captured following the annealing procedure.

The relaxed configuration reached after the annealing procedure at 60 °C is used as a starting point for the other two temperatures studied, 80 and 90 °C. In each case, 32 hydrogens are randomly removed from the water molecules to form OH- ions. This is done to avoid reactivity of the OH- with the quaternary ammonium during the annealing procedure. After that, we equilibrate the system to the final temperature with another 100 ps of isobaric-isothermal (NPT) simulation followed by 400 ps of canonical (NVT) propagation. Only the last 200 ps are used to compute the diffusion coefficients. Since ReaxFF is a reactive force field, we can get a complete picture of the OH- diffusion accounting for both Grotthuss and vehicular diffusion.

NPT and NVT simulations employ a Nosé-Hoover integrator with the recommended damping relaxation time of 100 timesteps with a timestep of 0.25 fs, which reasonably conserves the energy in NVE simulations.

The diffusion coefficients of water, OH- and H2 are computed through the mean squared displacement (MSD)[38] and averaged over 10 trajectories. Due to the Grotthuss diffusion mechanism of the OH-, it is necessary to track changes in the identity of the oxygen atom, which can alternate between belonging to a water molecule and to a hydroxide ion.

where MSD (𝜏) is the mean squared displacement for a lag time 𝜏 and r(t) denotes the position of the species at time t. The diffusion coefficient[38] is related to the slope of the MSD against the lag time.

where D is the diffusion coefficient, and s represents the slope of the MSD against the lag time.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and initial characterization of the membranes

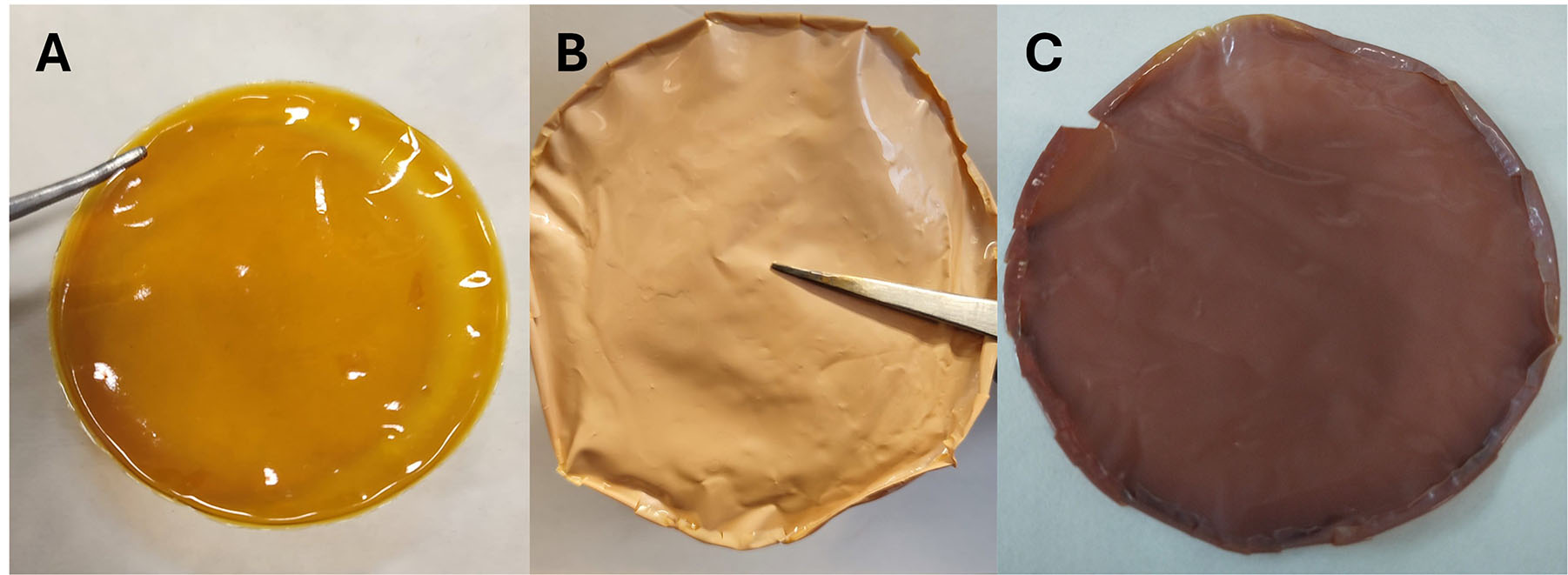

PBI/PVBC films were successfully prepared by the casting method, resulting in a flexible and translucent brown appearance, as observed in Figure 2A. After quaternization with DABCO or MPY, they retain their flexibility, but their appearance changes to opaque (lighter for DABCO and darker for MPY,

Figure 2. PBI/PVBC membranes (A) prior to quaternization, (B) quaternized with DABCO, and (C) quaternized with MPY.

All three samples [Figure 2A-C] display good macroscopic homogeneity, with smooth and continuous surfaces free from visible cracks or phase separation. Minor heterogeneities and structural defects, not apparent at the macroscopic scale, are more clearly observed in the SEM images (see Section "Structural and morphological characterization of the membranes"), confirming that microscopic morphology - rather than bulk uniformity - governs the fine structural features of these membranes.

The membranes were initially characterized by IEC, WU and ionic conductivity measurements to test their suitability for alkaline zero gap water electrolyser applications. For comparison purposes, commercial membranes of FAA-3-50 and Dapozol M-40 were also characterized and tested. FAA-3-50 is an AEM composed of bromide polysulfone with quaternary ammonium groups widely used for alkaline ion exchange electrolysis investigations[15,40],

Dapozol M-40 is not an ion-exchange membrane; it does not possess fixed charged functional groups in its structure. It is composed entirely of PBI, making it a suitable reference for membranes synthesized using PBI as a primary component.

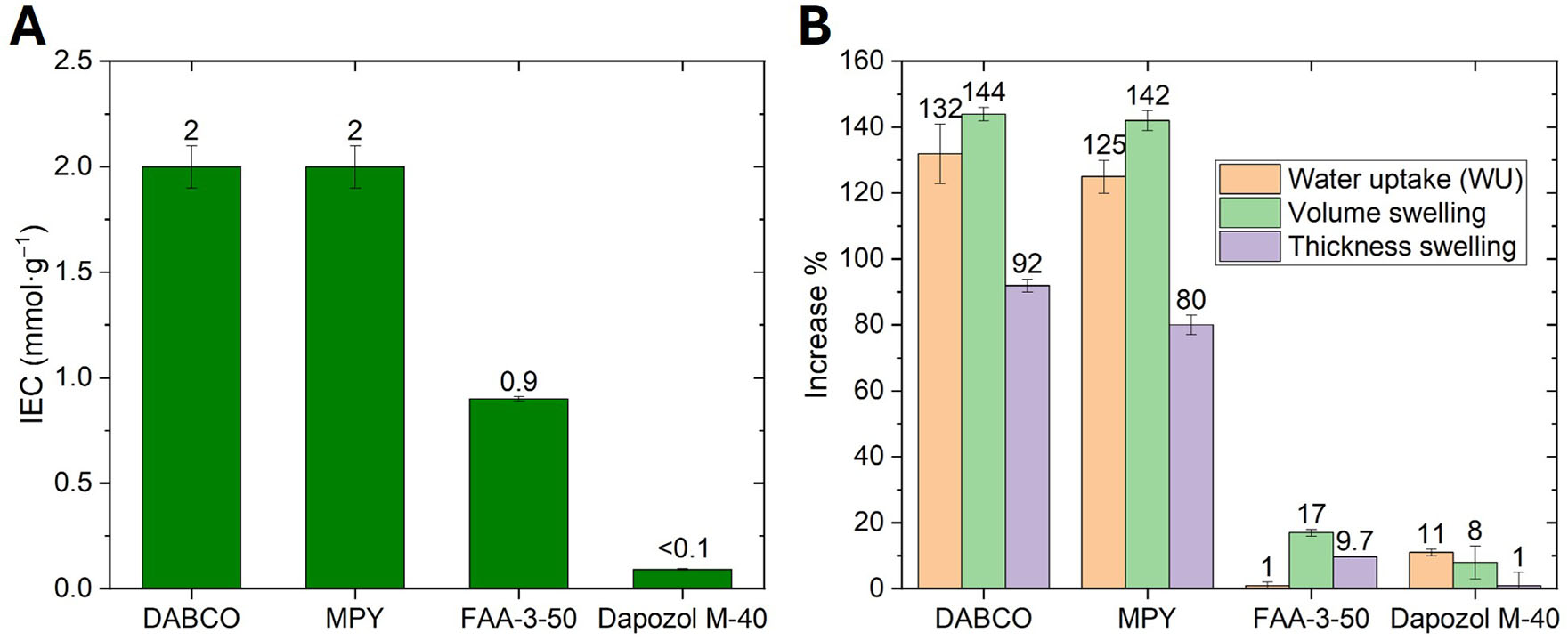

IEC and WU results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. (A) Ion exchange capacity (IEC) and (B) water uptake (WU) and swelling ratio values of the membranes.

The IEC values of the DABCO-based membrane are similar to those reported in the literature[34]. Results for the MPY membranes are comparable, which is consistent with the fact that both membranes derive from a similar structure; furthermore, the abundance of quaternization sites is expected to be the same.

The membrane composition was designed with a fixed PVBC-to-PBI molar ratio of 2:1. Under these conditions, crosslinking between PVBC and PBI was found to be partial rather than complete, as indicated by the IEC values obtained after quaternization [Figure 3]. The relatively high IEC values confirm that a fraction of the chloromethyl groups from PVBC did not react with PBI, providing reactive sites for subsequent quaternization with MPY or DABCO. This partial crosslinking is consistent with the synthetic conditions employed and is essential to preserving sufficient ionic functionality and hydroxide conductivity in the final membranes. Similar behavior has been reported for related systems, where controlled crosslinking between PVBC and PBI was used to balance mechanical integrity and ion-exchange performance[41-43].

The results of this study reveal certain relationships between the IEC, ionic conductivity, hydration, and barrier properties in the synthesized AEMs. Firstly, a positive correlation between IEC and ionic conductivity is generally expected, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. The MPY and DABCO-based membranes demonstrate consistent and high performance both in IEC and conductivity, indicating efficient ion transport pathways. Both membranes exhibit higher IEC (approximately 2.0 mmol·g-1) and conductivity than the commercial FAA-3-50 membrane (IEC ~ 1.0 mmol·g-1). Furthermore, all synthesized membranes show significantly higher WU, volume swelling, and thickness swelling compared to the FAA-3-50 benchmark, which is consistent with their higher hydrophilicity and IEC. Interestingly, this elevated hydration does not lead to increased hydrogen gas crossover; in fact, the crossover is lower. This apparent contradiction can be explained by the formation of a denser, more cross-linked morphology in our synthetic membranes. This structure allows for substantial water absorption to facilitate ion conduction while simultaneously presenting a more tortuous path for gas permeation, effectively decoupling the membrane's hydration properties from its gas barrier performance.

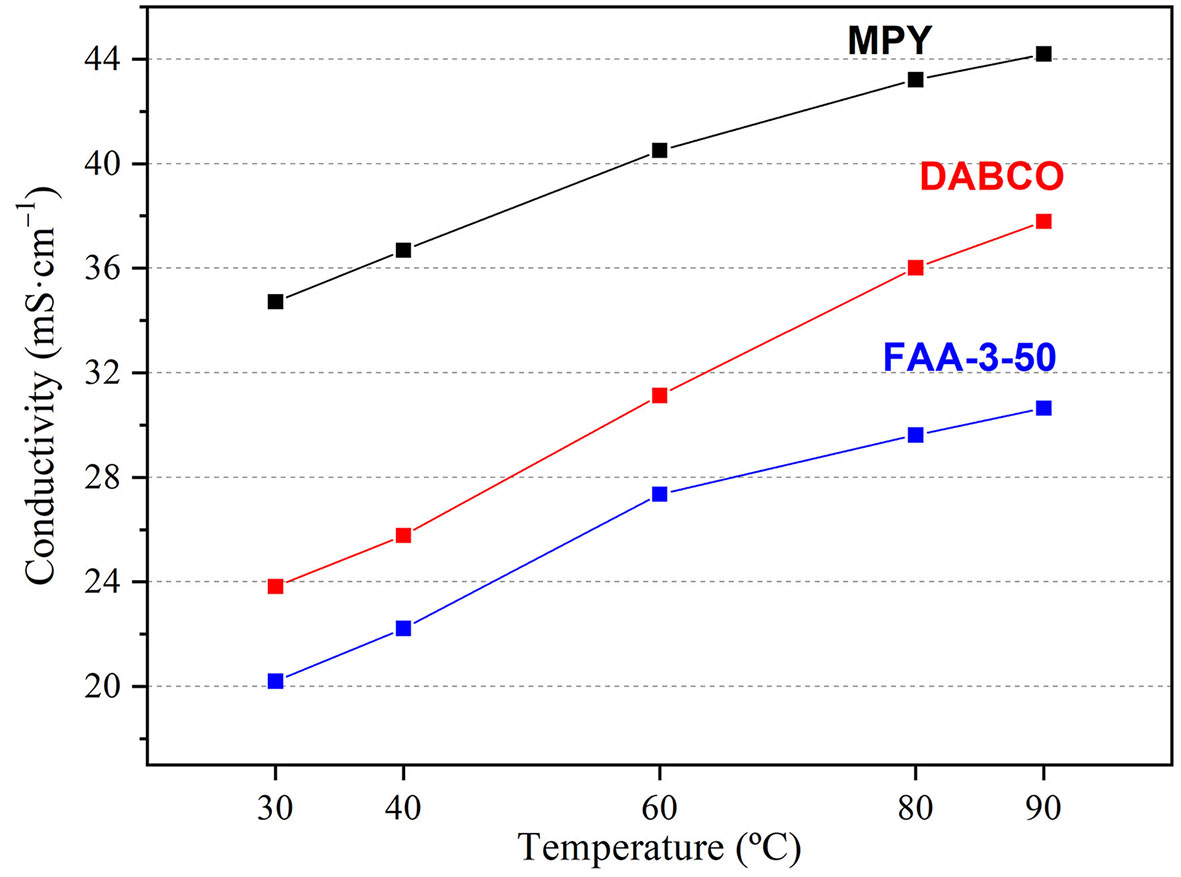

Figure 4. Ionic conductivity of the membranes at various temperatures after immersion in 1 M KOH for 1 day.

The difference in quaternizing agent and procedure does not appear to affect the IEC values obtained. FAA-3-50 values also correlate well with those previously reported[44]. Additionally, Dapozol M-40 has a negligible value, as expected, since it does not possess ion-exchange groups. The IEC values of PBI/PVBC-based and FAA-3-50 membranes are considered quite good for electrolyzer applications - high enough to facilitate OH- conductivity but not so high as to compromise membrane integrity. Regarding WU and swelling behavior, the higher values of the PBI/PVBC-based membranes are in accordance with their IECs and show that the structures are quite flexible and sponge-like compared to the commercial membranes. WU and volume swelling values are very similar between DABCO- and MPY-based membranes, but DABCO has a slightly higher thickness swelling. The values obtained are not particularly high, so the membranes are not expected to present problems, such as lower selectivity or deteriorated structural integrity, due to swelling in the electrolysis cell. FAA-3-50 shows a relatively small WU when compared to its volume swelling. This might be due to a relatively flexible structure that expands significantly when a small amount of water is added. On the other hand, Dapozol M-40 shows higher WU than FAA-3-50 but lower volume and thickness swelling. This could be explained by a more rigid structure that does not change significantly during hydration/dehydration but is porous and allows the inclusion of a significant amount of water.

Ionic conductivity results, measured in a custom-built ex situ cell, are presented in Figure 4.

The temperature-dependent OH- conductivity of the membranes is presented in Figure 4. All three membranes show a positive correlation between temperature and ionic conductivity, consistent with thermally activated ion transport. The low activation energy values - 7.2 kJ·mol-1, 3.7 kJ·mol-1 and 6.5 kJ·mol-1 for DABCO, MPY and FAA membranes, respectively (see Supplementary Figure 4) - correlate well with facilitated ion transport through well-hydrated membranes[36,45]. The MPY-based membrane exhibits the highest conductivity, reaching approximately 44 mS·cm-1 at 90 °C, followed by the DABCO-based membrane (~38 mS·cm-1 at 90 °C), while the commercial FAA-3-50 membrane shows the lowest values (~30 mS·cm-1 at 90 °C). These results reflect the combined effects of IEC, hydration, and membrane microstructure, with the synthetic membranes achieving higher conductivity due to their greater IEC and WU while maintaining a controlled crosslinked structure that limits excessive swelling.

In comparison with these state-of-the-art PAP-based AEMs, the hydroxide conductivity values of our synthesized membranes are moderate but fully consistent with those typically observed for crosslinked imidazolium- and quaternary ammonium-based systems. As shown in Figure 4, the commercial FAA-3-50 membrane exhibits a conductivity of 32 mS·cm-1 at 90 °C, while our DABCO- and MPY-functionalized membranes reach 38 mS·cm-1 and 43 mS·cm-1, respectively, under the same conditions. Although these conductivities are lower than the record values reported for poly(aryl piperidinium) membranes

Good mechanical properties are essential to maintain the dimensional stability of a membrane during its operational lifecycle and to prevent catastrophic failures due to sudden breaking. The mechanical properties of the prepared and commercial membranes are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 and

Considering the application in alkaline fuel cells or electrolyzers, where membranes must withstand mechanical stress and high hydration, this enhanced mechanical strength is a positive factor for long-term physical stability and integrity. However, the balance between rigidity (to resist swelling) and some ductility (to handle operational stresses) must be carefully considered for each specific application.

Membrane activation conditions

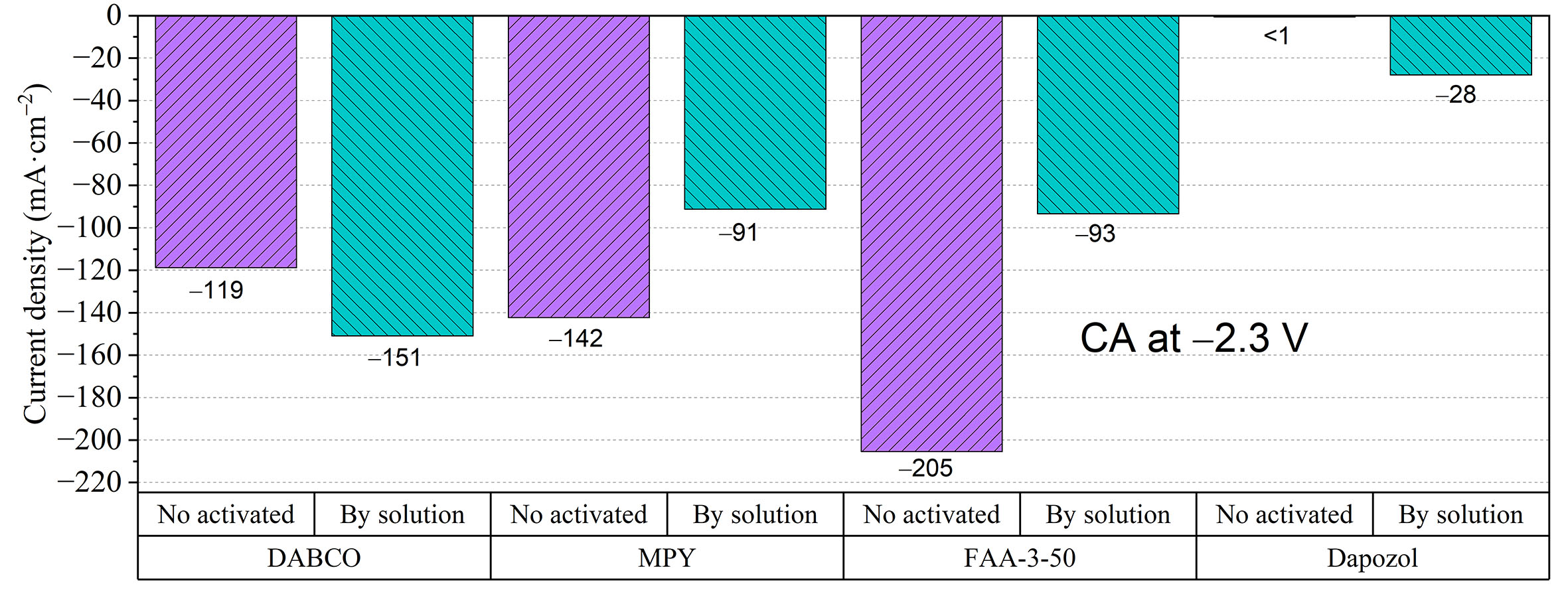

In order to optimize the operating conditions of the zero gap electrolyzer, the membranes were subjected to an activation process, consisting of immersion in KOH 1M solution for 18 h. Afterward, they were subjected to chronoamperometry at a potential of -2.3 V for 5 min. The current densities at the end of the chronoamperometries (CAs) were recorded. The results comparing the membranes with and without activation are presented in Figure 5 and examples of CAs are presented in Supplementary Figure 6. The results with the next activation methodology are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 5. Current densities obtained for the membranes, with (blue) and without activation (violet) by immersion in 1 M KOH, on the electrolyzer at CAs of E = -2.3 V for t = 5 min at a 23 mL·min-1 electrolyte flow rate.

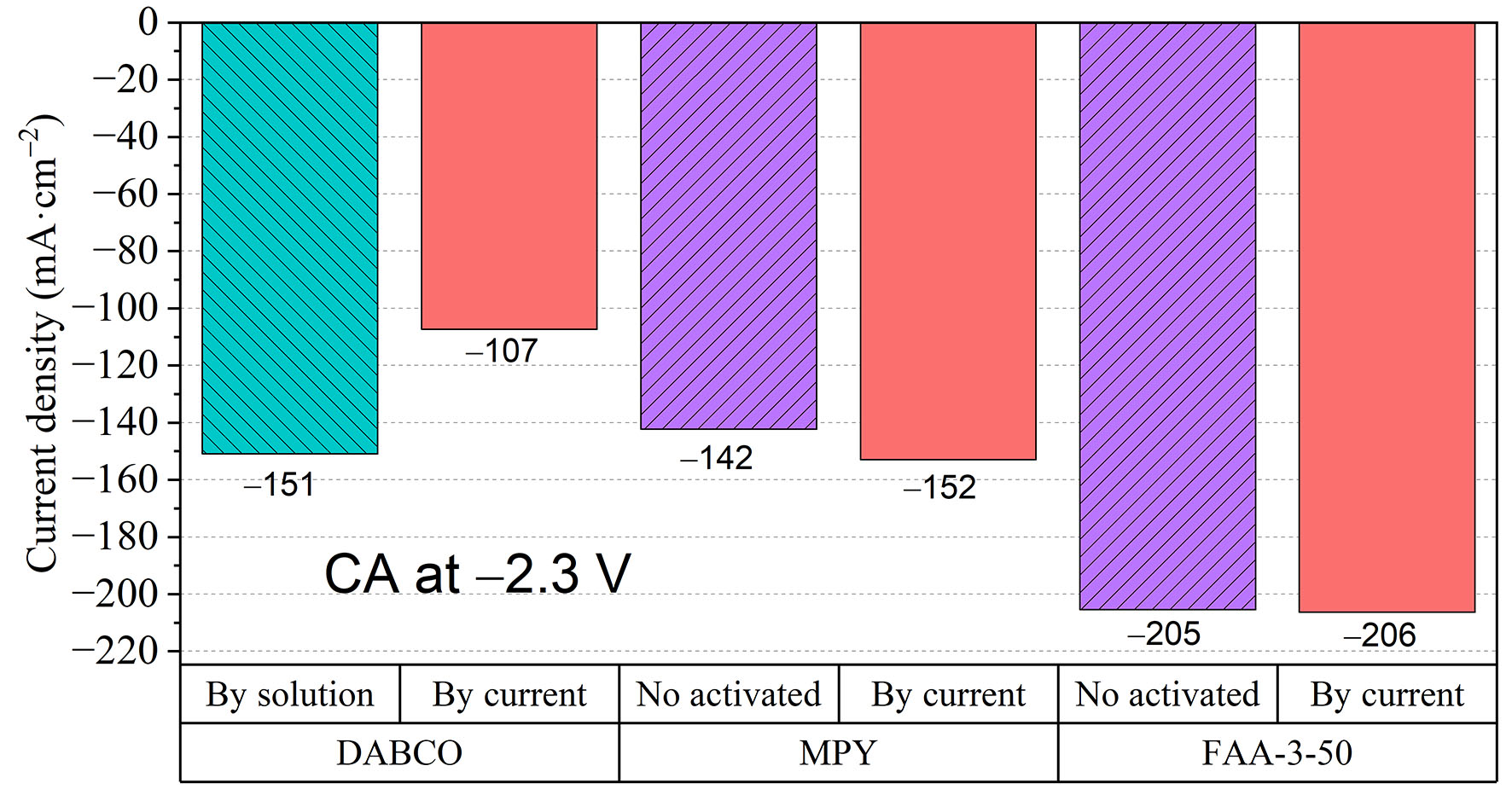

Figure 6. Current densities obtained for the membranes using their previously determined optimal activation methods, followed by constant current activation, on the electrolyzer at CAs of -2.3 V for 5 min and a 23 mL·min-1 electrolyte flow rate.

As expected from the previous characterization, the Dapozol M-40 membrane showed very poor performance without activation and was only slightly better when activated, likely due to being fully filled with the alkaline electrolyte. FAA-3-50 shows the best performance, but activation with an alkaline solution results in poorer performance than simply assembling the membrane directly. A similar effect is observed for the MPY membrane, while the DABCO membrane improves with activation, reaching current densities similar to the non-activated MPY membrane and not far from FAA-3-50. This different behavior likely stems from distinct internal structures. SEM images in Figure 7 show that the DABCO membrane is more porous/heterogeneous, which may require a larger amount of electrolyte to fill the structure and perform better when "activated". On the other hand, FAA-3-50 and MPY membranes are more dense/homogeneous; excessive electrolyte might increase their resistance or disrupt their structure, thus they work better when "non-activated". Conversely, the dense and homogeneous morphology of MPY and FAA-3-50 membranes [Figure 7B and C] appears to feature pre-established efficient conduction pathways. Excessive swelling from KOH immersion might disrupt these optimal structures, leading to a performance decrease. This hypothesis is further supported by the WU data [Figure 3], which shows a higher capacity for the DABCO membrane. From this point, the Dapozol M-40 membrane is discarded, and the following tests are performed only with the remaining membranes.

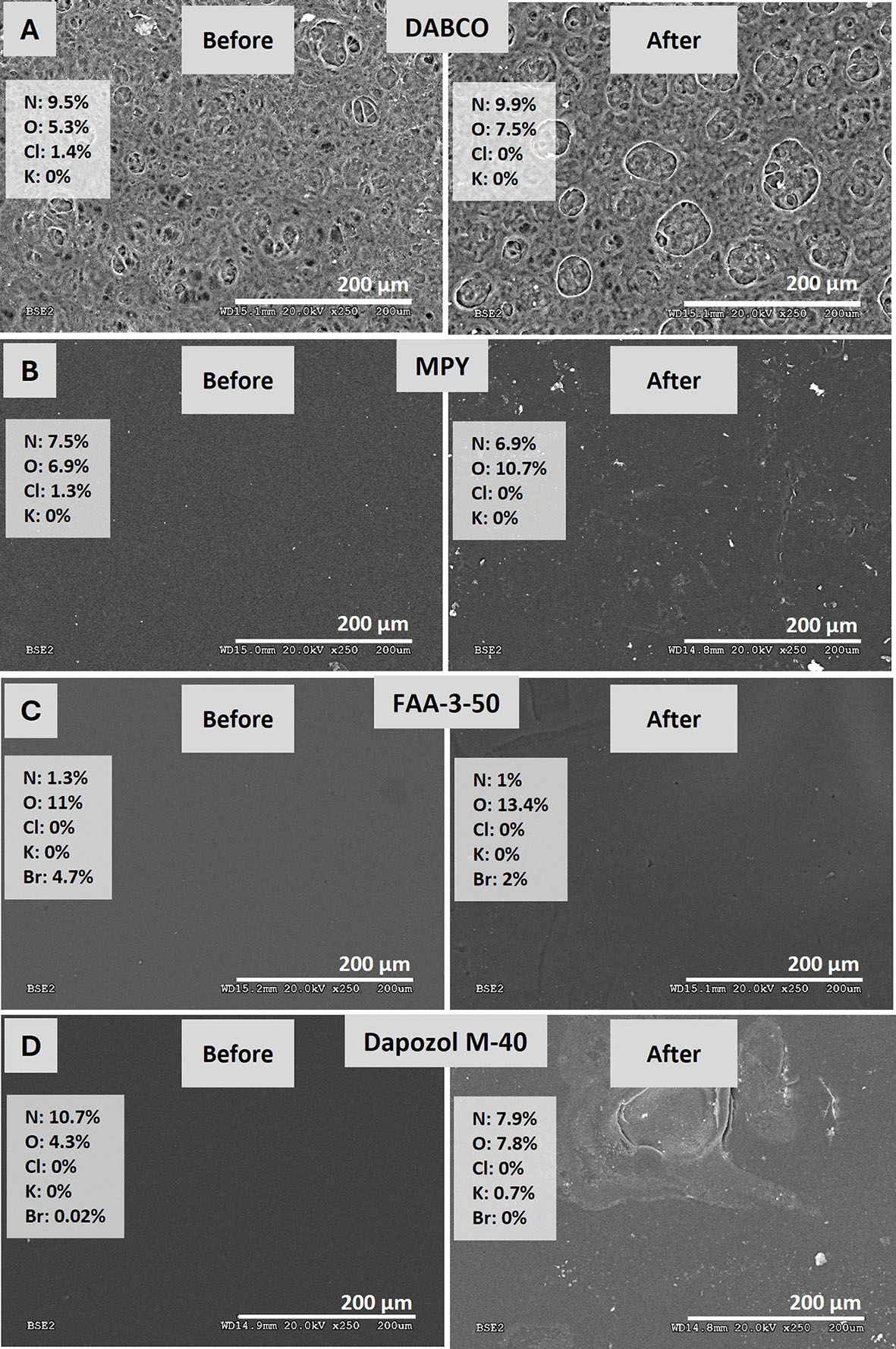

Figure 7. SEM images and EDX analysis of membranes (A) DABCO, (B) MPY, (C) FAA-3-50, and (D) Dapozol M-40, before and after a

In addition, another activation strategy (activation by current) was tested by means of chronopotentiometry (CP) at -50 mA·cm-2 in a zero-gap flow cell to see if this process improves the membrane’s performance. Testing was conducted under the previously optimized conditions for each membrane: the DABCO membrane was activated by solution, while the MPY and FAA-3-50 membranes were not. The results are presented in Figure 6.

Activation by current yields results similar to the previous ones for FAA-3-50 and shows a slight improvement in the MPY membranes. The DABCO membrane again presents the opposite behavior, resulting in lower performance. The improvement in the first two membranes is likely related to the optimization and stabilization of OH- transport pathways through the membrane under constant operating conditions. In contrast, for the DABCO membrane, the rearrangement of the transport pathways appears to hinder performance at these relatively low current densities.

The obtained gas volumes from anodic and cathodic sides allowed for the calculation of the FE, H2/O2 ratio and H2 production for each test; the results obtained are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The high FEs confirm the efficient conversion of current to H2 at the cathode and an almost perfectly stoichiometric amount of O2 at the anode; the latter is slightly lower, likely due to some corrosion of the graphite plates[46]. H2 production conforms to the current densities obtained in accordance with Faraday's laws. Moreover, Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) curves for FAA, DABCO, and MPY membranes under their optimal conditions (activated by current for FAA and MPY, and by solution for DABCO) are illustrated in Supplementary Figure 7. These results were obtained after the corresponding CA tests and reflect the similar behavior of DABCO and MPY, as well as the superior performance of the FAA membrane.

Structural and morphological characterization of the membranes

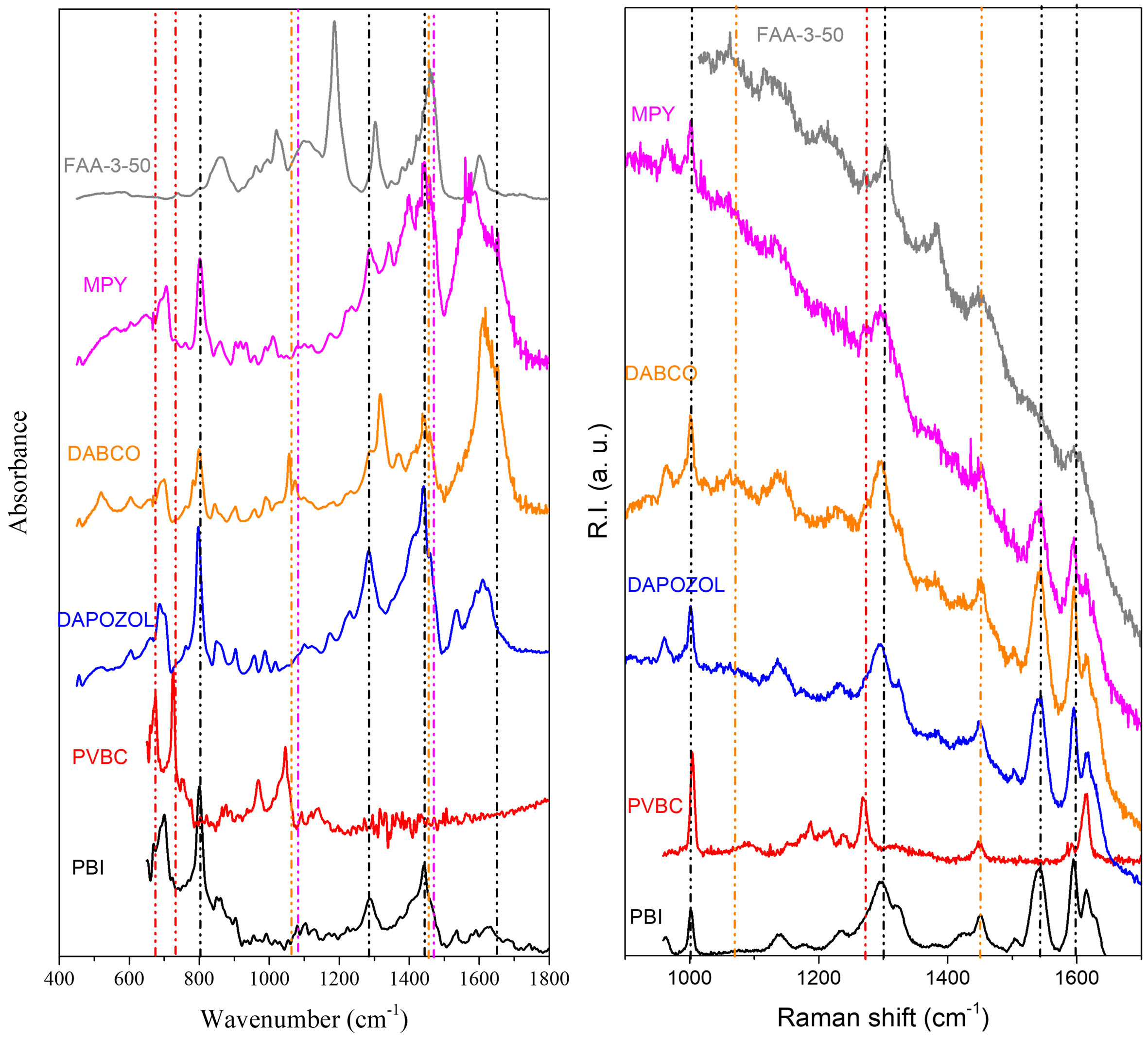

The membranes were characterized by SEM/EDX [Figure 7] and IR and Raman spectroscopy [Figure 8] before and after the electrolysis tests to gain information about possible transformations.

SEM/EDX

Figure 7A shows that the DABCO-quaternized membrane exhibits high porosity and heterogeneity both before and after use, probably due to the ethanol employed as a solvent during quaternization. Its higher swelling capacity compared to the other membranes may enable greater OH- uptake upon immersion in the alkaline solution, consistent with the observed improvement in electrolyzer performance after solution activation. EDX analysis reveals a decrease in chlorine content, indicating effective Cl- - OH- exchange with the electrolyte.

In Figure 7B, the MPY-quaternized membrane displays greater homogeneity and lower porosity than the previous sample, which may explain the reduced electrolyzer performance after solution activation, as KOH permeation is hindered. After operation, slight surface marks appear, and the nitrogen content decreases by ~1%, suggesting minor degradation. The disappearance of chlorine by EDX confirms efficient interaction with the electrolyte.

The commercial FAA-3-50 membrane [Figure 7C] also maintains a homogeneous morphology after use, which explains its behavior similar to that of the MPY-quaternized membrane in both activation and electrolyzer performance. Bromine is present as the original counterion instead of chlorine, and its post-use decrease indicates a favorable electrolyte interaction.

Finally, the Dapozol M-40 membrane [Figure 7D] remains homogeneous prior to use, with only minor morphological changes afterwards. Its comparatively poor performance likely arises from lower ionic conductivity rather than significant structural degradation.

IR and Raman spectroscopy

To gain further insight into the composition of the membranes, spectroscopic analyses were carried out by IR spectroscopy and Raman microscopy. For the IR spectra shown in Figure 8, ATR and baseline corrections were applied. In the analysis, the individual spectra for PBI and PVBC are also plotted for clarity. A general feature observed in all membranes quaternized with DABCO, MPY, and Dapozol M-40 are the bands due to the presence of PBI and PVBC polymers as for example the bands at 675 cm-1 (CH2-Cl), 800 cm-1 (C=C and C=N), 1,265 cm-1 (Imidazole ring) and 2,923 cm-1 (aliphatic CH2), all of which are characteristic of the presence of PVBC polymer. Also, characteristic features of the PVB backbone can be found in the bands

Moving to the Raman spectra [Figure 8], baseline correction was not applied since, despite the evident fluorescence, the characteristic peaks are clearly visible and the information is not masked, thus avoiding potential distortions from such correction. For this technique, only the membranes prior to their use in the electrolyzer - without activation - were analyzed, as no significant differences were observed after operation, most likely due to the short operating time. Spectra recorded after the 5 min CA test confirmed the absence of relevant changes. In Figure 8, corresponding to the DABCO-quaternized membrane, a peak at 1,600 cm-1 stands out, assigned to the aromatic ring vibrations of the PBI backbone; this feature is also present in the MPY- and Dapozol M-40-based membranes, respectively, all composed of PBI.

In the synthesized membranes, a peak at 1,290 cm-1 is observed, corresponding to CH2 deformation upon substitution of chlorine with the cyclic tertiary amine DABCO in the first case, and with aromatic MPY in the second. This finding corroborates the successful quaternization of the membranes. In the case of the MPY-quaternized membrane, a peak at 1,050 cm-1 is also visible, corresponding to C-N vibrations of the pyrrolidine ring, further confirming quaternization with this agent. Regarding the commercial membrane FAA-3-50, a band in the 1,297-1,374 cm-1 region is observed, associated with the narrowing of the carbon chain backbone of the membrane. Several vibrational bands already identified in the IR spectra are also observed in the Raman spectra, such as 1,601 cm-1 (C=C), 1,460 (-CH2 δ), 1,303 (-CH3 δ), and 1,188 cm-1 (C-N). These bands confirm the hydrocarbon polymer composition of the membrane and the presence of quaternary ammonium groups as the ion exchange sites.

Finally, Supplementary Figures 8 and 9 and Supplementary Table 3 show the complete range (up to CH vibrations) IR and Raman spectra and a summary of the most relevant IR bands present in the synthesized membranes.

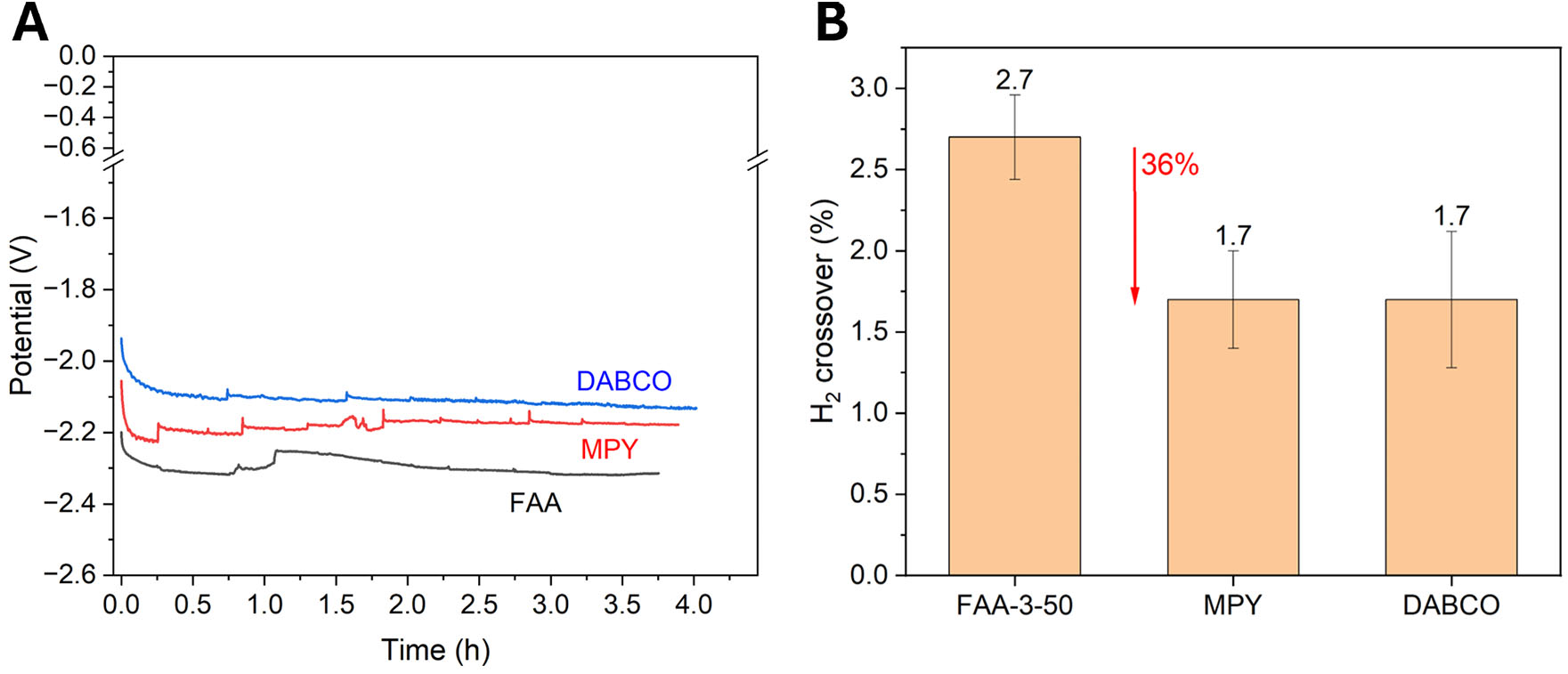

Stability electrolyzer tests

To evaluate the membranes under more demanding operating conditions, a stability test was performed for -100 mA·cm-2. During the test, gases produced at the anodic and cathodic sides were sampled periodically to investigate potential H2 crossover from cathode to anode. The results are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9. (A) Stability tests consisting of chronopotentiometry (CP) for 3.5 h at -100 mA·cm-2 and a 23 mL·min-1 electrolyte flow rate. (B) H2 crossover values, represented as the mean H2 vol.% present in the anodic gas composition during the stability tests.

As can be observed, the three tested membranes exhibit very stable and similar behavior in the stability test, with DABCO and MPY membranes obtaining slightly better potentials than their commercial counterpart, with very good potential values of -2.1 V and -2.2 V for DABCO and MPY membranes, respectively, requiring lower energy input. DABCO membrane improves substantially working at -100 mA·cm-2, compared to the activation at -50 mA· cm-2, suggesting a change in the transport paths, more beneficial for this membrane, with higher current densities. The obtained FEs, included in Supplementary Table 2, are very high, demonstrating efficient conversion of current to H2. The trends observed during the extended stability tests can be attributed to several common factors in AEM electrolysis, as previously discussed. While the excellent chemical stability of the membranes was confirmed by SEM-EDX and IR, the harsh anodic conditions are known to promote gradual corrosion of the graphite flow plates[46]. This parasitic corrosion reaction consumes a small fraction of the applied current, thereby reducing the overall FE. Additionally, operational factors such as minor flooding/drying events or trace impurity adsorption could also contribute to this effect over time. It is important to note that FE values remaining above 90% during stability operation are still considered excellent and are on par with the state-of-the-art for AEMWE systems reported in the literature[48]. The H2/O2 volume ratio also maintains values consistent with the previous experiments. The H2 production rate also shows excellent results, around 4.5 mmol·h-1, in accordance with the imposed current density. Moreover, the H2 crossover values obtained in the stability test [Figure 9] are very low, remaining 3%. PBI/PVBC-based membranes outperform the commercial FAA-3-50, showing a H2 crossover of around 1.7%, which is 36% lower than that of the FAA-3-50 membrane. This is an excellent result for electrolysis applications, as H2 purity is of high importance for both industrial standards and safety. The PBI/PVBC crosslinked membranes, even in the more porous case quaternized with DABCO, have proven to be superior barriers to H2 crossover while maintaining similar or even enhanced electrochemical performance. This combination of properties makes these membranes excellent candidates for further research and application in zero-gap alkaline water electrolyzers.

The H2 crossover to the anode in our AEM water electrolyzer remains below 2% when using MPY- and DABCO-functionalized membranes, demonstrating an excellent balance between gas separation and ionic transport. These values are comparable to, or lower than, those reported for other high-performance AEM systems in recent literature. Klinger et al. (2024) measured a H2 crossover of approximately 1.5% at 2 A cm-2 in a polyimidazolium AEMWE configuration[49]. Hager et al. (2025) reported values between 0.3% and 1.5% depending on current density[50]. In contrast, Kim et al. (2023) found crossover levels of around 5% in hydrated ion-exchange membranes, linking this behavior to the microstructure and connectivity of ion transport channels[51]. Moreno-González et al. (2023) demonstrated long-term AEMWE operation with H2 crossover below 0.5% at 70 °C and 1 M KOH, well within industrial safety limits[52].

Overall, the measured crossover is well aligned with state-of-the-art values for durable AEMs, confirming that the membrane architecture effectively suppresses gas permeation while preserving high hydroxide conductivity. These results reinforce the critical role of controlled crosslinking and optimized microstructure in achieving safe and efficient operation in AEM water electrolysis systems.

A comparison of this work with several state-of-the-art AEMWE configurations is presented in Table 1.

Performance comparison of various state-of-the-art membranes for AEMWE

| Membrane | Cathode//Anode | Electrolyte | T (°C) | Current density (mA·cm-2) | Voltage (V) | FE (%) | H2 production (mmol·h-1) | H2 crossover (%) | Ref. |

| Quaternized PP | Pt Ru/C//IrO2 | H2O | 80 | 150 | 1.80 | NR | NR | NR | [53] |

| PAP-TP-85 | Pt/C//FexNiyOOH-20F | 1 M KOH | 80 | 1,500 | 1.74 | NR | NR | NR | [54] |

| PPO24-BIM | Pt/C//IrO2 | 0.5 M KOH | 50 | 300 | 1.80 | NR | NR | NR | [55] |

| PBI-based AEM | Ni-Fe-Co//Ni-Fe-Ox | 1 M KOH | 60 | 1,000 | 2.08 | NR (74% voltage eff.) | NR | NR | [56] |

| PSEBS-CM-DABCO | NiFe2O4//NiCo2O4 | 10 wt% KOH | 40 | 120 | 2.0 | NR | NR | NR | [57] |

| PBI/PVBC-DABCO | Ni mesh//Pt/C | 1 M KOH | 60 | 100 | 2.1 | 93.2 | 4.5 | 1.7 | (This work) |

| PBI/PVBC-MPY | Ni mesh//Pt/C | 1 M KOH | 60 | 100 | 2.2 | 93.2 | 4.5 | 1.7 | (This work) |

| FAA-3-50 | Ni mesh//Pt/C | 1 M KOH | 60 | 100 | 2.3 | 97.4 | 4.7 | 2.7 | (This work) |

There is a wide variety of results regarding voltage and current densities. The studies of Xiao et al.[54] and Vincent et al.[56] report high current density values of 1,500 and 1,000 mA·cm-2 at relatively low voltages but using complex catalysts. Our results are comparable in current density and voltage to those reported by

While the present study focuses on our specific catalyst configuration, the consistently lower H2 crossover values observed for the synthetic membranes compared to the commercial FAA-3-50 suggest that their improved material properties represent a general trend. However, further validation using various commercial catalysts will be necessary to confirm the extent to which this behavior depends on catalyst loading, morphology, and electrochemical activity.

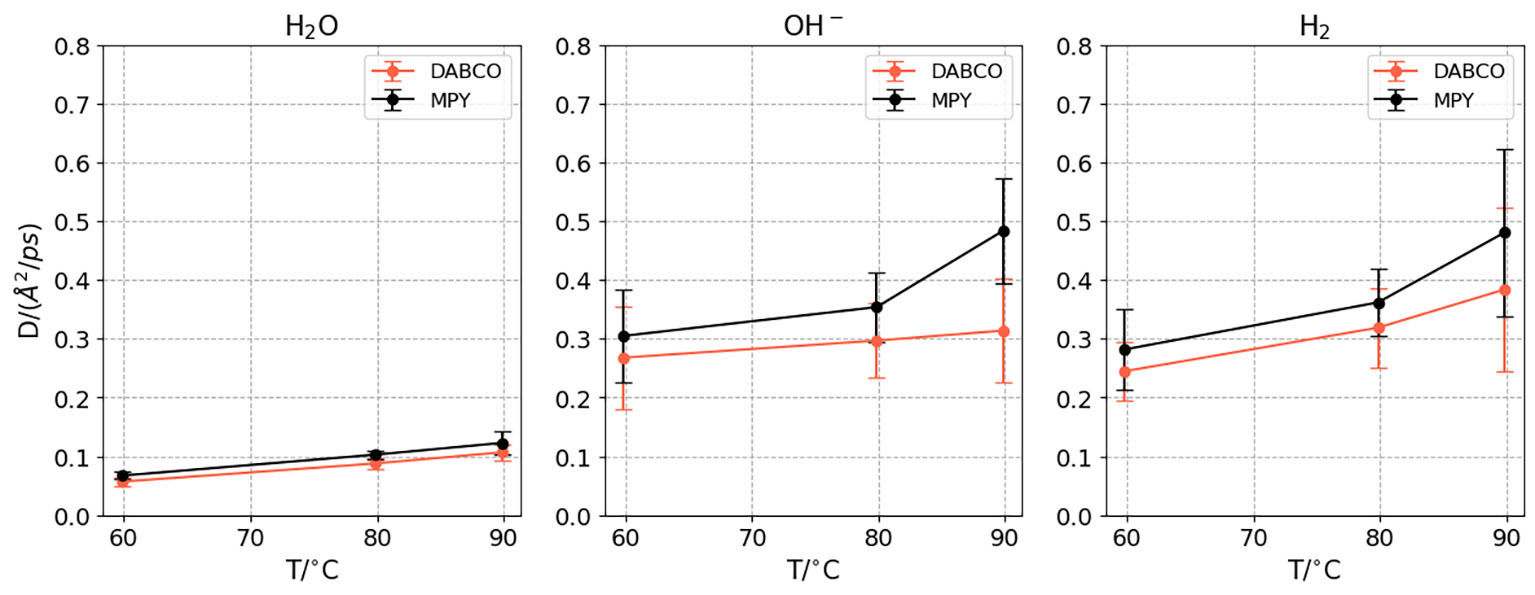

Computational results

The diffusion coefficients of the OH- and H2 species were computed in the presence of DABCO and MPY polymers to assess the overall effect of their interactions with the quaternary ammonium groups in the membrane and to examine how these results relate to the experimentally measured conductivity and H2 crossover.

In Figure 10, the diffusion coefficients for water, OH- and H2 species are presented as a function of temperature for both membranes, computed as the mean over 10 trajectories. The error bars are estimated as the standard deviation of the mean[58,59].

Figure 10. The diffusion coefficients of water, OH- and H2 molecules for the three temperatures studied in the presence of DABCO and MPY membranes.

The diffusion of water and OH- is mediated by the hydrogen bond structure of the media. In bulk water, a well-organized and compact structure allows proton diffusion to be about four to eight times larger than in hydrated membranes[60,61] due to proton transfer that leads to the Grotthuss mechanism. In Figure 10, we observe that water diffusion coefficients are almost equal in the presence of both membranes, suggesting that the water structure in both membranes is similar. While this does not have to be the case in general, the shared backbone structure of the two membranes allows for the formation of very similar channels through which the water can move.

While water diffusion is not significantly altered by the nature of the membrane, OH- diffusion shows substantial differences. We find that OH- diffusion is not uniquely determined by the structure of the water molecules, but also by interactions with the specific quaternary ammonium groups. In our simulations, diffusion is consistently higher in the MPY membrane compared to the DABCO membrane. This result qualitatively agrees with the experimental observation of higher conductivity in the MPY membrane, although the exact ratio cannot be directly reproduced from the diffusion coefficients. This discrepancy is expected, as the Nernst-Einstein relation between conductivity and the diffusion coefficient involves corrections related to the simulation volume[62], which varies between membranes to maintain consistent density. Furthermore, contributions from K+ or Na+ cations to the experimental conductivity were not included in the simulations. Overall, the calculated diffusion coefficient of OH- in the presence of the membrane serves as a reliable estimator of the final conductivity.

A second objective of the computational study is to identify whether the H2 crossover observed experimentally can be correlated with its diffusion coefficient within the membrane. This is a simplified approximation, as other phenomena such as electro-osmotic drag and phase-transfer effects may play significant roles. In AEMs, the hydroxide ion flux from cathode to anode drags water convectively toward the anode, enhancing the transport of dissolved H2 and potentially increasing crossover at higher current densities[49,63]. This is opposite to the trend typically observed in PEMs[64-66]. However, these convective effects are not included in our simulations, which are conducted under neutral conditions. From a modeling standpoint, classical MD captures only bulk diffusion and may underestimate these coupled effects, whereas more advanced methods - such as non-equilibrium MD (NEMD)[67] or the use of dedicated force fields for weak H2-polymer interactions - would provide a more realistic description of crossover behavior.

In Figure 10, the computed diffusion coefficients for H2 are presented. We find good qualitative agreement between the experimental H2 crossover observed at 60 °C and the diffusion coefficients calculated for both membranes, which exhibit similar behavior in this regard. This correspondence extends up to 80 °C; however, at higher temperatures, distinct differences emerge. In this specific case, the H2 diffusion coefficient appears to be a reliable indicator of crossover. Nevertheless, we cannot conclude that this correlation holds for all systems, given the molecular complexity of H2 mobility, and future work will be required to further assess this relationship.

CONCLUSIONS

This work demonstrates the successful design and development of novel PBI/PVBC-based AEMs for alkaline water electrolysis. The combination of experimental characterization and MD simulations has provided a comprehensive understanding of both the structural and transport properties of these membranes.

The incorporation of quaternary ammonium groups through DABCO or MPY quaternization yielded membranes with well-defined structural features and suitable ionic conductivity. Both membranes exhibited markedly improved gas-barrier properties, achieving a 30% decrease in H2 crossover compared to the commercial FAA-3-50 membrane, which is a critical parameter for safety and efficiency in green hydrogen production. MD simulations offered valuable insight into the diffusion behavior of OH-, directly linking the role of functional groups at the molecular scale with macroscopic properties such as conductivity and selectivity. In this study, the diffusion coefficient of H2 is also closely correlated to the experimental crossover, while more evidence is still needed to attest that diffusion is the limiting step in H2 crossover. Although FAA-3-50 delivered the best performance in short activation tests, the newly developed membranes provided highly competitive performance while significantly enhancing stability and considerably decreasing H2 crossover. Dapozol M-40, in contrast, was ruled out due to poor electrochemical behavior. The overall results position PBI/PVBC-based membranes as promising candidates for next-generation alkaline water electrolyzers, combining durability, safety, and efficiency.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. J. C. Pérez Flores (Renewable Energy Research Institute, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain) for performing the mechanical tensile tests on the membranes. The authors would also like to thank Dr. A. Sanchez Muzas and Dr. F. Gámez Márquez for their careful revision and polishing of the English language in this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Moreno, J. R. A.; del Mazo-Sevillano, P.; Herranz, D.

Data curation, methodology: Rodríguez, S.; Gijón, A.; del Mazo-Sevillano, P.; Herranz, D.

Formal analysis, investigation: Herranz, D.; Rodríguez, S.; Gijón, A.; del Mazo-Sevillano, P.; Herranz, D.

Writing - original draft preparation: Herranz, D.

Writing - review and editing: Ocón, P.; Moreno, J. R. A.; Herranz, D.; del Mazo-Sevillano, P.; Gijón, A.

Visualization: Rodríguez, S.; Ocón, P.; Moreno, J. R. A.; Herranz, D.; del Mazo-Sevillano, P.; Gijón, A.

Resources: Moreno, J. R. A.; del Mazo-Sevillano, P.; Herranz, D.; Gijón, A.; Ocón, P.

Supervision: del Mazo-Sevillano, P.; Herranz, D.; P.O.: Moreno, J. R. A.

Project administration, funding acquisition: Herranz, D.; del Mazo-Sevillano, P.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Some results supporting the study are presented in the Supplementary Materials. Other raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Madrid Regional Research Council (CAM) under project SI4/PJI/2024-00168 (Spain). The authors also thank the CCC-UAM (Graforr project) for the allocation of computer time.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Schmidt, J.; Gruber, K.; Klingler, M.; et al. A new perspective on global renewable energy systems: why trade in energy carriers matters. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 2022-9.

2. Zhang, C.; Hu, M.; Sprecher, B.; et al. Revealing the interplay between decarbonisation, circularity, and cost-effectiveness in building energy renovation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7153.

3. Norman, E.; Maestre, V.; Ortiz, A.; Ortiz, I. Steam electrolysis for green hydrogen generation. State of the art and research perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2024, 202, 114725.

4. Kim, J. H.; Jo, H. J.; Han, S. M.; Kim, Y. J.; Kim, S. Y. Recent advances in electrocatalysts for anion exchange membrane water electrolysis: design strategies and characterization approaches. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500099.

5. Chang, C.; Ting, Y.; Yen, F.; Li, G.; Lin, K.; Lu, S. High performance anion exchange membrane water electrolysis driven by atomic scale synergy of non-precious high entropy catalysts. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500117.

6. Kim, J.; Seo, J. H.; Lee, J. K.; Oh, M. H.; Jang, H. W. Challenges and strategies in catalysts design towards efficient and durable alkaline seawater electrolysis for green hydrogen production. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500076.

7. Xu, L.; Wang, H.; Min, L.; Xu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Anion exchange membranes based on poly(aryl piperidinium) containing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic side chains. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 14232-41.

8. Li, H.; Yu, N.; Gellrich, F.; et al. Diamine crosslinked anion exchange membranes based on poly(vinyl benzyl methylpyrrolidinium) for alkaline water electrolysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 633, 119418.

9. Caielli, T.; Ferrari, A. R.; Bonizzoni, S.; et al. Synthesis, characterization and water electrolyzer cell tests of poly(biphenyl piperidinium) Anion exchange membranes. J. Power. Sources. 2023, 557, 232532.

10. Caielli, T.; Ferrari, A. R.; Stucchi, D.; et al. Poly(biphenyl-piperidinium)/poly(biphenyl-trifluoroacetophenone) random and block copolymers enabling highly stable anion exchange membranes for water electrolysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 160825.

11. Peng, Z.; Wei, T.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J. Fabrication and investigation of anion exchange membranes based on poly(terphenyl piperidonium) copolymers with dibenzothiophene or dibenzofuran units for water electrolysis. J. Power. Sources. 2025, 642, 236918.

12. Ziv, N.; Dekel, D. R. A practical method for measuring the true hydroxide conductivity of anion exchange membranes. Electrochem. Commun. 2018, 88, 109-13.

13. Wright, A. G.; Fan, J.; Britton, B.; et al. Hexamethyl-p-terphenyl poly(benzimidazolium): a universal hydroxide-conducting polymer for energy conversion devices. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2130-42.

14. Unlu, M.; Zhou, J.; Kohl, P. A. Publisher's note: anion exchange membrane fuel cells: experimental comparison of hydroxide and carbonate conductive ions [Electrochem. Solid-State Lett., 12, B27 (2009)]. Electrochem. Solid-State. Lett. 2009, 12, S7.

15. Min, K.; Lee, Y.; Choi, Y.; Kwon, O. J.; Kim, T. High-performance anion exchange membranes achieved by crosslinking two aryl ether-free polymers: poly(bibenzyl N-methyl piperidine) and SEBS. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 664, 121071.

16. Motealleh, B.; Liu, Z.; Masel, R. I.; Sculley, J. P.; Richard Ni, Z.; Meroueh, L. Next-generation anion exchange membrane water electrolyzers operating for commercially relevant lifetimes. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2021, 46, 3379-86.

17. Shi, G.; Tano, T.; Tryk, D. A.; et al. Nanostructured Pt-NiFe oxide catalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline electrolyte membrane water electrolyzers. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 9460-8.

18. Hu, X.; Tian, X.; Lin, Y. W.; Wang, Z. Nickel foam and stainless steel mesh as electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction, oxygen evolution reaction and overall water splitting in alkaline media. RSC. Adv. 2019, 9, 31563-71.

19. Podrojková, N.; Gubóová, A.; Streckova, M.; Kromka, F.; Oriňaková, R. Experimental and computational analysis of Ni-P and Fe-P metal foams for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline media. Sustain. Energy. Fuels. 2025, 9, 5044-56.

20. Coppola, R. E.; D'accorso, N. B.; Abuin, G. C. Synthesis, characterization and performance of new 1,4‐diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane derivatives in anion exchange membranes. Polym. Int. 2023, 73, 30-7.

21. Dong, D.; Zhang, W.; van Duin, A. C. T.; Bedrov, D. Grotthuss versus vehicular transport of hydroxide in anion-exchange membranes: insight from combined reactive and nonreactive molecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 825-9.

22. Merle, G.; Wessling, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Anion exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cells: a review. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 377, 1-35.

23. Merinov, B. V.; Goddard, W. A. Computational modeling of structure and OH-anion diffusion in quaternary ammonium polysulfone hydroxide - Polymer electrolyte for application in electrochemical devices. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 431, 79-85.

24. Han, K. W.; Ko, K. H.; Abu-hakmeh, K.; Bae, C.; Sohn, Y. J.; Jang, S. S. Molecular dynamics simulation study of a polysulfone-based anion exchange membrane in comparison with the proton exchange membrane. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014, 118, 12577-87.

25. Choe, Y.; Fujimoto, C.; Lee, K.; et al. Alkaline stability of benzyl trimethyl ammonium functionalized polyaromatics: a computational and experimental study. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 5675-82.

26. Si, Z.; Qiu, L.; Dong, H.; Gu, F.; Li, Y.; Yan, F. Effects of substituents and substitution positions on alkaline stability of imidazolium cations and their corresponding anion-exchange membranes. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014, 6, 4346-55.

27. Van Duin, A. C. T.; Dasgupta, S.; Lorant, F.; Goddard, W. A. ReaxFF: a reactive force field for hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001, 105, 9396-409.

28. Zhang, W.; van Duin, A. C. T. Second-generation ReaxFF water force field: improvements in the description of water density and OH-anion diffusion. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017, 121, 6021-32.

29. Van Duin, A. C. T., Zou, C., Joshi, K., Bryantsev, V., Goddard, W. A. A reaxff reactive force-field for proton transfer reactions in bulk water and its applications to heterogeneous catalysis. In Asthagiri, A.; Janik, M. J.; The royal society of chemistry, 2013; pp 223-43.

30. Achtyl, J. L.; Unocic, R. R.; Xu, L.; et al. Aqueous proton transfer across single-layer graphene. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6539.

31. Ouma, C. N. M.; Obodo, K. O.; Bessarabov, D. Computational approaches to alkaline anion-exchange membranes for fuel cell applications. Membranes 2022, 12, 1051.

32. Tee, S. Y.; Win, K. Y.; Teo, W. S.; et al. Recent progress in energy-driven water splitting. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1600337.

33. Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chhowalla, M.; Liu, B. Recent advances in design of electrocatalysts for high-current-density water splitting. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.07322.

34. Coppola, R.; Herranz, D.; Escudero-Cid, R.; et al. Polybenzimidazole-crosslinked-poly(vinyl benzyl chloride) as anion exchange membrane for alkaline electrolyzers. Renew. Energy. 2020, 157, 71-82.

35. Gonçalves Biancolli, A. L.; Herranz, D.; Wang, L.; et al. ETFE-based anion-exchange membrane ionomer powders for alkaline membrane fuel cells: a first performance comparison of head-group chemistry. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018, 6, 24330-41.

36. Wang, Z.; Sun, G.; Lewis, N. H. C.; et al. Water-mediated ion transport in an anion exchange membrane. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1099.

37. Thompson, A. P.; Aktulga, H. M.; Berger, R.; et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 271, 108171.

38. Zhang, W.; Van Duin, A. C. T. ReaxFF reactive molecular dynamics simulation of functionalized poly(phenylene oxide) anion exchange membrane. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015, 119, 27727-36.

39. Martínez, L.; Andrade, R.; Birgin, E. G.; Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2157-64.

40. Lim, H.; Jeong, I.; Choi, J.; et al. Anion exchange membranes and ionomer properties of a polyfluorene-based polymer with alkyl spacers for water electrolysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 610, 155601.

41. Herranz, D.; Coppola, R. E.; Escudero-Cid, R.; et al. Application of crosslinked polybenzimidazole-poly(vinyl benzyl chloride) anion exchange membranes in direct ethanol fuel cells. Membranes 2020, 10, 349.

42. Hao, J.; Gao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, F.; Shao, Z.; Yi, B. Fabrication of N1-butyl substituted 4,5-dimethyl-imidazole based crosslinked anion exchange membranes for fuel cells. RSC. Adv. 2017, 7, 52812-21.

43. Arslan, F.; Chuluunbandi, K.; Freiberg, A. T. S.; et al. Performance of quaternized polybenzimidazole-cross-linked poly(vinylbenzyl chloride) membranes in HT-PEMFCs. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 56584-96.

44. Salmeron-Sanchez, I.; Asenjo-Pascual, J.; Avilés-Moreno, J.; Pérez-Flores, J.; Mauleón, P.; Ocón, P. Chemical physics insight of PPy-based modified ion exchange membranes: a fundamental approach. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 643, 120020.

45. Wang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, R.; et al. Highly conductive and dimensionally stable anion exchange membranes enabled by rigid poly(arylene alkylene) backbones. Synth. Met. 2023, 296, 117385.

46. Bussetti, G.; Campione, M.; Bossi, A.; et al. In situ atomic force microscopy: the case study of graphite immersed in aqueous NaOH electrolyte. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2020, 135, 329.

47. Cordes, M.; Walter, J. Infrared and Raman studies of heterocyclic compounds - II Infrared spectra and normal vibrations of benzimidazole and bis-(benzimidazolato)-metal complexes. Spectrochim. Acta. Part. A. 1968, 24, 1421-35.

48. Mulk, W. U.; Aziz, A. R. A.; Ismael, M. A.; et al. Electrochemical hydrogen production through anion exchange membrane water electrolysis (AEMWE): recent progress and associated challenges in hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2024, 94, 1174-211.

49. Klinger, A.; Strobl, O.; Michaels, H.; et al. Transport of hydrogen through anion exchange membranes in water electrolysis. Adv. Materials. Inter. 2024, 12, 2400515.

50. Hager, L.; Schrodt, M.; Hegelheimer, M.; et al. Cationic groups in polystyrene/O-PBI blends influence performance and hydrogen crossover in AEMWE. Chem. Commun. 2024, 61, 149-52.

51. Kim, S.; Song, J.; Duy Nguyen, B. T.; et al. Acquiring reliable hydrogen crossover data of hydrated ion exchange membranes to elucidate the ion conducting channel morphology. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144696.

52. Moreno-González, M.; Mardle, P.; Zhu, S.; et al. One year operation of an anion exchange membrane water electrolyzer utilizing Aemion+® membrane: minimal degradation, low H2 crossover and high efficiency. J. Power. Sources. Adv. 2023, 19, 100109.

53. Li, D.; Matanovic, I.; Lee, A. S.; et al. Phenyl oxidation impacts the durability of alkaline membrane water electrolyzer. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 9696-701.

54. Xiao, J.; Oliveira, A. M.; Wang, L.; et al. Water-fed hydroxide exchange membrane electrolyzer enabled by a fluoride-incorporated nickel-iron oxyhydroxide oxygen evolution electrode. ACS. Catal. 2020, 11, 264-70.

55. Marinkas, A.; Struźyńska-Piron, I.; Lee, Y.; et al. Anion-conductive membranes based on 2-mesityl-benzimidazolium functionalised poly(2,6-dimethyl-1,4-phenylene oxide) and their use in alkaline water electrolysis. Polymer 2018, 145, 242-51.

56. Vincent, I.; Lee, E. C.; Kim, H. M. Highly cost-effective platinum-free anion exchange membrane electrolysis for large scale energy storage and hydrogen production. RSC. Adv. 2020, 10, 37429-38.

57. Hnát, J.; Plevová, M.; Žitka, J.; Paidar, M.; Bouzek, K. Anion-selective materials with 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane functional groups for advanced alkaline water electrolysis. Electrochim. Acta. 2017, 248, 547-55.

58. Grossfield, A.; Patrone, P. N.; Roe, D. R.; Schultz, A. J.; Siderius, D. W.; Zuckerman, D. M. Best practices for quantification of uncertainty and sampling quality in molecular simulations [Article v1.0]. Living. J. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 1, 5067.

59. Gijón Gijón, A. Classical and quantum molecular dynamics simulations of condensed aqueous systems. Doctoral Thesis, 2021. Available from: https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/700171. [Last accessed on 15 Jan 2026].

60. Paddison, S. Proton conduction mechanisms at low degrees of hydration in sulfonic acid-based polymer electrolyte membranes. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2003, 33, 289-319.

61. Jang, S. S.; Goddard, W. A. Structures and transport properties of hydrated water-soluble dendrimer-grafted polymer membranes for application to polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells: classical molecular dynamics approach. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007, 111, 2759-69.

62. France-Lanord, A.; Grossman, J. C. Correlations from ion pairing and the nernst-einstein equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 136001.

63. Liu, L.; Ma, H.; Khan, M.; Hsiao, B. S. Recent advances and challenges in anion exchange membranes development/application for water electrolysis: a review. Membranes 2024, 14, 85.

64. Bernt, M.; Schröter, J.; Möckl, M.; Gasteiger, H. A. Analysis of gas permeation phenomena in a PEM water electrolyzer operated at high pressure and high current density. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 124502.

65. Fahr, S.; Engel, F. K.; Rehfeldt, S.; Peschel, A.; Klein, H. Overview and evaluation of crossover phenomena and mitigation measures in proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2024, 68, 705-21.

66. Martin, A.; Trinke, P.; Bensmann, B.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R. Hydrogen crossover in PEM water electrolysis at current densities up to 10 A cm-2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 094507.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].