Recent advances in spring-assisted triboelectric nanogenerators

Abstract

Spring-assisted triboelectric nanogenerators (S-TENGs) have emerged as effective energy harvesters of low-frequency, low-amplitude vibrations via resonance tuning, amplified relative motion, and enhanced contact force between triboelectric layers. Unlike conventional triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs), S-TENGs uniquely harness elastic resonance through integrated spring structures to efficiently harvest low-frequency and subtle mechanical vibrations that are otherwise difficult to convert into electricity, thereby enhancing overall energy conversion efficiency. Recent innovations in triboelectric materials, electrode designs, and structures have enabled the development of high-performance TENGs for sustainable green energy. This review highlights the pivotal role of spring elements in improving S-TENG performance and provides design insights for constructing robust, self-powered, and maintenance-free sensing platforms. Diverse architectures include linear and multi-degree-of-freedom systems, as well as cantilever, tower, helical, magnetic, and composite designs. Each is engineered to optimize vibration response and maximize output performance, enabling it to be used as an independent power source. Hybrid triboelectric-electromagnetic integration, negative-stiffness mechanisms, and mechanical frequency regulation further extend the adaptability of S-TENGs to real-world conditions. Industrial equipment monitoring, wireless carbon dioxide sensing, omnidirectional vibration harvesting, and motor fault detection in unmanned aerial vehicles demonstrate the versatility and practical impact of S-TENGs.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Rapid advancements in Internet of Things (IoT) technologies have increased interest in sustainable, independent energy solutions for powering distributed electronics and autonomous sensor networks[1-5]. Green energy harvesting systems, such as wind-, solar-, thermal-, and water-power plants, capture and convert ambient energy from the surrounding environment into useful electrical power for large-scale power sources; however, these systems are limited by environmental dependence, space requirements, and discontinuous operation[6-8]. In contrast, triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) offer a compact, adaptable platform that converts small-scale mechanical vibrations into electrical energy through the combined effects of triboelectrification and electrostatic induction. When two materials with distinct electron affinities come into contact and separate, charge transfer occurs, creating a potential difference that drives current through an external circuit[9-11]. This mechanism enables efficient energy harvesting from diverse mechanical sources such as vehicle-induced vibrations, water flow, human motion, and pipeline oscillations, making TENGs promising for distributed IoT power[12,13].

Fine vibrations are small, continuous mechanical oscillations that occur with low amplitude and often at low frequency, typically resulting from machinery, structures, or fluid flow. For example, fine vibrations from pipelines and industrial facilities exhibit amplitudes ranging from 20 µm to 4,000 µm over the 0-300 Hz frequency range[14,15]. Furthermore, spring-assisted vibration sensors have been integrated into unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to monitor motor vibration in real time and enable early-warning functions, offering high sensitivity and stability in a compact, low-cost form factor[16-18].

Low-frequency and low-amplitude vibrations pose challenges for energy harvesting devices owing to reduced input kinetic energy and contact force between triboelectric layers during energy harvesting under the contact-separation mode, reducing charge transfer and considerably reducing output power density[19,20]. To overcome the challenges associated with fine vibrations commonly present in practical environments, spring elements have been integrated into TENG architectures to tune resonance, amplify relative motion, and enhance contact forces under weak excitations[21-23]. Recent examples include hybrid spring-assisted nanogenerators that couple triboelectric and electromagnetic mechanisms to generate high-voltage and high-current simultaneously[24], and inertia-driven spring TENGs capable of powering wireless carbon dioxide (CO2) sensors under fine vibrations[25]. Multi-degree-of-freedom (DOF) spring systems have further expanded the operational frequency range by generating multiple resonant modes[26].

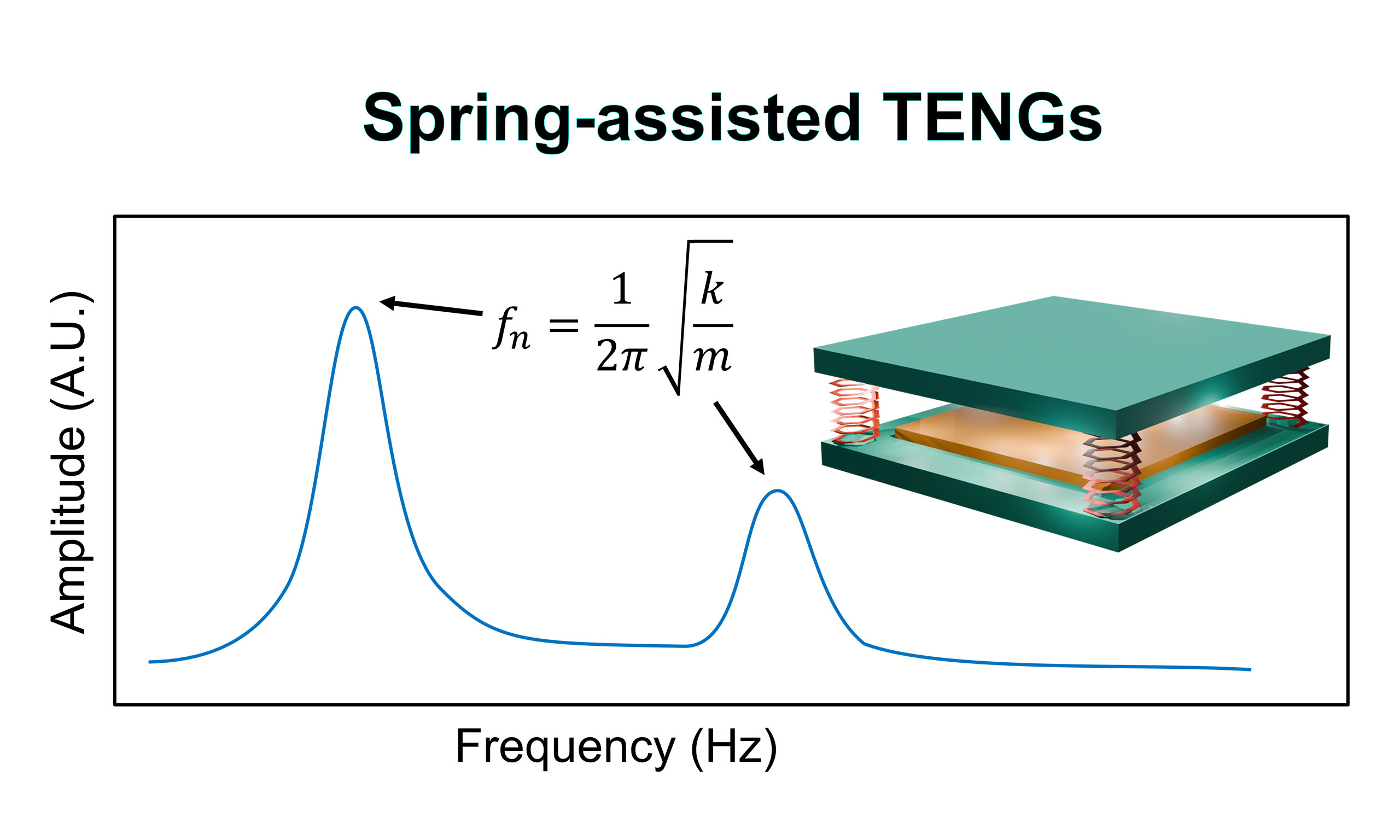

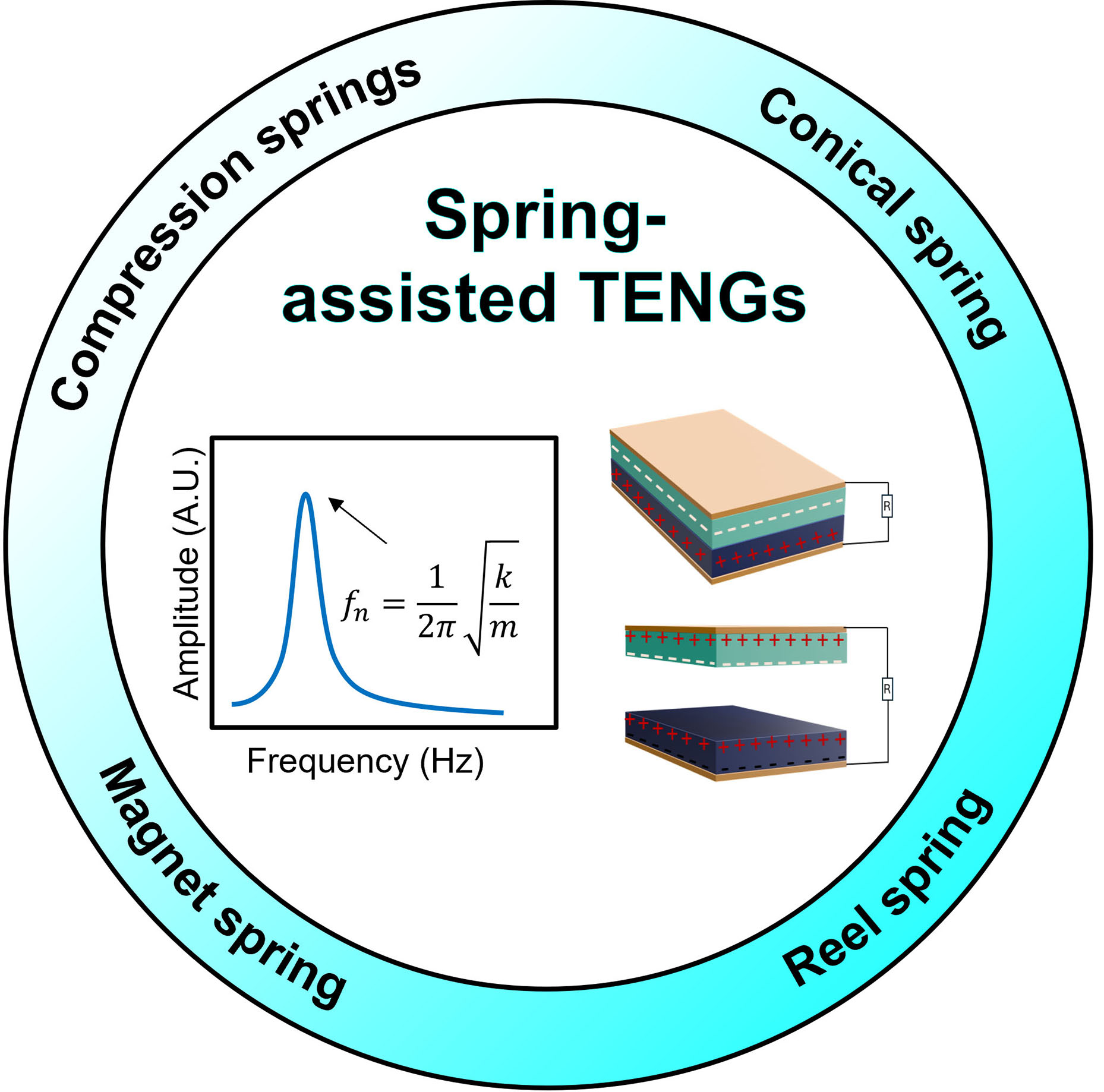

This review focuses on spring structures applicable to TENGs as a key strategy for recovering initial status after deformation and enhancing input kinetic energy, highlighting structural designs, resonance tuning mechanisms, performance improvements, and real-world applications [Figure 1]. Various studies have reported that integrating tuned spring mechanisms can amplify relative motion and optimize contact-separation cycles, enhancing electrical output and broadening operational bandwidth[27-29]. These advances present the crucial role of spring mechanisms in enhancing TENG performance, thereby expanding the application scope of TENGs. Specifically, spring-assisted TENGs (S-TENGs) demonstrate significant potential as independent energy solutions and offer pathways toward constructing robust, self-powered, and maintenance-free electronic platforms[30-34].

SPRING STRUCTURES AND RESONANT BEHAVIOR OF TENGS

Spring structures play a vital role in overcoming the limitations of low-frequency and low-amplitude vibrations in TENGs via resonance tuning and motion amplification[35]. In such systems, the spring-mass assembly stores mechanical energy during deformation and releases this energy to enhance relative motion between the triboelectric layers, improving contact force and displacement[36-38]. Resonance occurs when the excitation frequency matches the natural frequency (fn) of the system, allowing small external inputs to produce disproportionately large oscillations and considerably increasing energy conversion efficiency[39-42]. The fn of a simple spring-mass system is expressed as follows:

where k is the spring stiffness and m is the effective mass of the oscillating system. For multi-DOF, the spring constant and mass can be written in matrix form as follows[26]:

This relationship implies that the dynamic response of a S-TENG can be precisely tuned by adjusting the stiffness or the attached mass, allowing the resonant frequency to match environmental vibration frequencies. For example, reducing the spring stiffness or increasing the mass lowers the resonant frequency, enabling efficient energy harvesting from weak vibrations below. Conversely, higher stiffness or smaller mass increases the natural frequency. Achieving resonance maximizes the relative motion between triboelectric surfaces, especially under fine vibration conditions, to ensure minimum displacement. Multiple masses and springs in a single structure can facilitate multiple resonant frequencies.

Linear spring-assisted structures

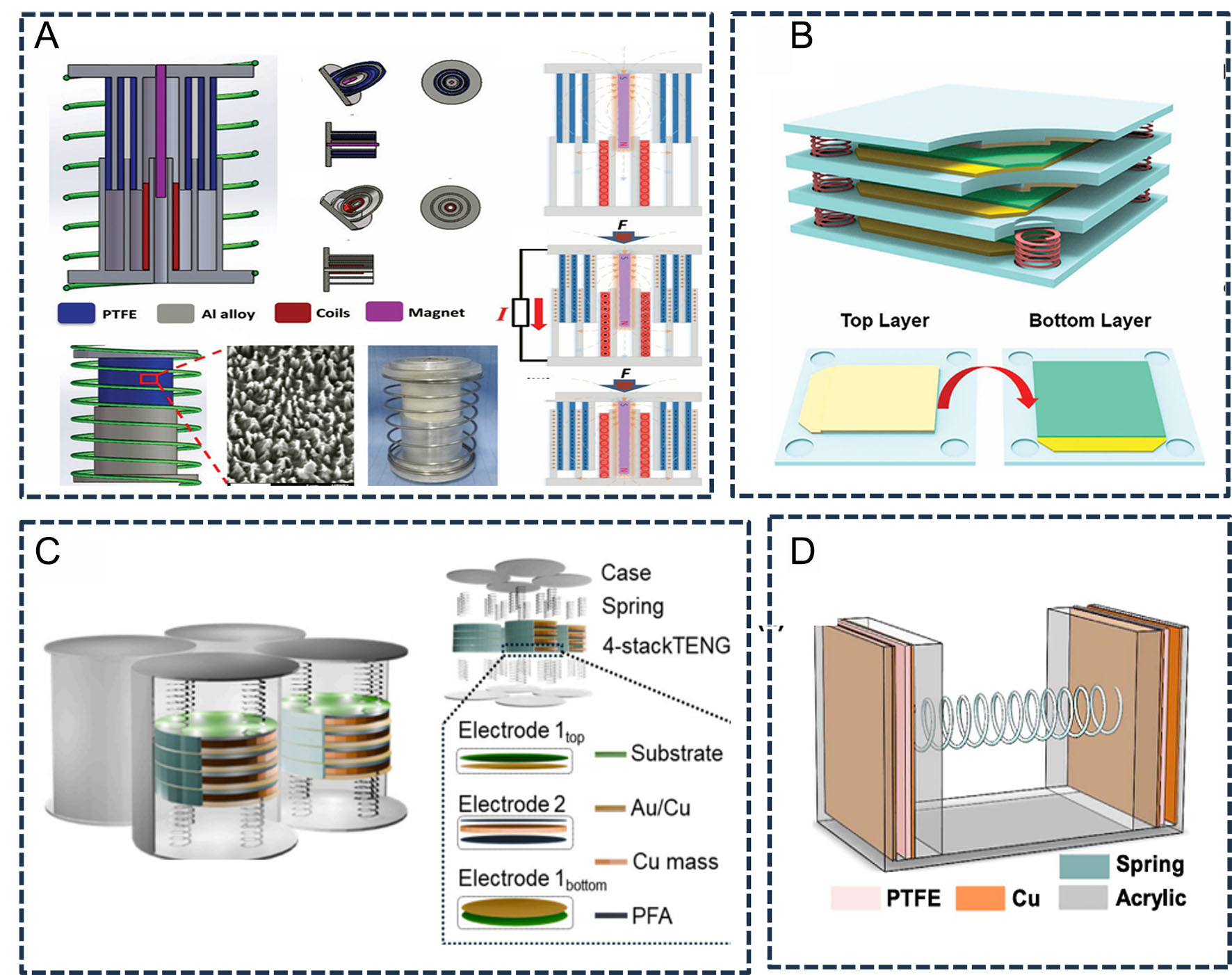

A spring-assisted hybrid nanogenerator (S-HNG), integrating a TENG and an electromagnetic generator (EMG), harvests low-frequency vibration energy to power small electronics and security systems[24]. The S-HNG employed a sliding-mode TENG with concentric polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and aluminum tubes, in which plasma-etched nanostructures on the PTFE surface enhanced charge generation, and a coaxial magnet-coil arrangement maximized magnetic flux variation during spring oscillation [Figure 2A]. The device used two aluminum cylinders with diameters of 5 cm and heights of 5.5 cm. Under 2 Hz operation, the TENG achieved an open-circuit voltage of 632 Vpeak and short-circuit current of 12.2 μApeak, delivering a power of 1.6 mWpeak under a 50 MΩ load. In contrast, the EMG generated 5.4 V and 36 mA, delivering a power of 57.6 mW under a 2 kΩ load. The spring structure supported fast recovery after compression, and a transformer matched the impedance between the TENG and EMG, enhancing the combined output and enabling rapid capacitor charging relative to those by the individual devices. The hybrid system continuously powered 40 light-emitting diodes (LEDs), a digital temperature-humidity meter, a liquid crystal display, and a wireless bicycle security alarm. Long-term cycling over 10,000 operations degraded the performance negligibly, and the electromagnetic damping effect inherent to the EMG coils additionally attenuated vibrations. This spring-assisted hybrid architecture offers a robust solution to achieve efficient low-frequency energy harvesting and self-powered sensing applications. Overall, this hybrid structure exhibits strong durability, impedance matching, and stable dual-mode energy conversion suitable for low-frequency vibration harvesting. However, its performance decreases under small vibration amplitudes, and full surface contact is difficult to maintain. Enhancing magnetic flux variation, increasing coil turns, and refining structural design are needed to further improve energy conversion efficiency and adaptability.

Figure 2. (A) S-HNG for powering small electronic devices. Used with permission[24]. Copyright 2009 Nanoscale. (B) Multi-DOF TENG with stacked layers and multiple resonant frequencies. Used with permission[26]. Copyright 2024 John Wiley and Sons. (C) Compact I-TENG for self-powered CO2 monitoring. Used with permission[25]. Copyright 2025 Elsevier. (D) S-TENG for efficient water-wave energy harvesting. Used with permission[43]. Copyright 2017 Elsevier.

Multiple DOF TENGs can efficiently harvest vibration energy with a low amplitude and a broad frequency distribution to power battery-free wireless sensor systems [Figure 2B][26]. The DOF design increases the degrees of freedom, which creates multiple resonant frequencies in a single device, thereby enabling continuous and efficient energy harvesting, even when the ambient vibration frequency fluctuates. This device employs vertically stacked contact-separation TENG units supported by corner-mounted springs, with aluminum (Al) serving as the positive triboelectric layer and electrode and a perfluoroalkoxy alkane (PFA) film serving as the negative triboelectric material. Each weight layer (20 g) is coupled to springs with a stiffness of 82.712 N m-1, creating tunable vibration modes that generate multiple resonant frequencies, i.e., one for 1-DOF (20.47 Hz), two for 2-DOF (12.63 and 33.17 Hz), and three for 3-DOF (9.12, 25.55, and

Tiruneh et al. developed a highly compact inertia-driven TENG (ITENG) tailored to harvest fine vibrations from industrial pipelines, enabling self-powered wireless CO2 monitoring [Figure 2C][25]. The device featured a vertically stacked structure composed of four triboelectric layers, each integrating a freestanding copper (Cu) mass attached to a plasma-treated PFA film that generated friction against electroless nickel immersion gold (ENIG)-plated Cu electrodes in the vertical contact-separation mode. The device has a cylindrical housing with a diameter of 75 mm and a height of 65 mm, corresponding to an approximate volume of

Jiang et al. developed an S-TENG for efficient water wave energy harvesting by transforming low-frequency wave motion into high-frequency oscillations [Figure 2D][43]. The device comprised a box structure containing two Cu-PTFE-coated acrylic blocks connected by a spring and sliding between Cu electrodes fixed to opposite walls, generating electricity based on contact-separation. The integrated S-TENG device was encapsulated in an acrylic box with an outer dimension of 21.5 cm × 21.5 cm × 8.5 cm. Optimizing the spring parameters (a length of 4.5 cm and moderate stiffness) enabled effective storage of elastic potential energy, resulting in multiple oscillations per wave impact and improving overall charge generation. The spring-assisted design increased charge transfer by 113% and enhanced total electrical energy by 150% relative to the rigid-body configuration, with a measured resonant frequency of approximately 4.75 Hz. A single unit achieved 458 Vpeak, 45.8 μApeak, and 5.38 mWpeak at a matched resistance of 10 MΩ, whereas the integrated system of four optimized units packaged in a sealed acrylic enclosure achieved 562.8 Vpeak,

Cantilever, tower, and helical spring-based structures

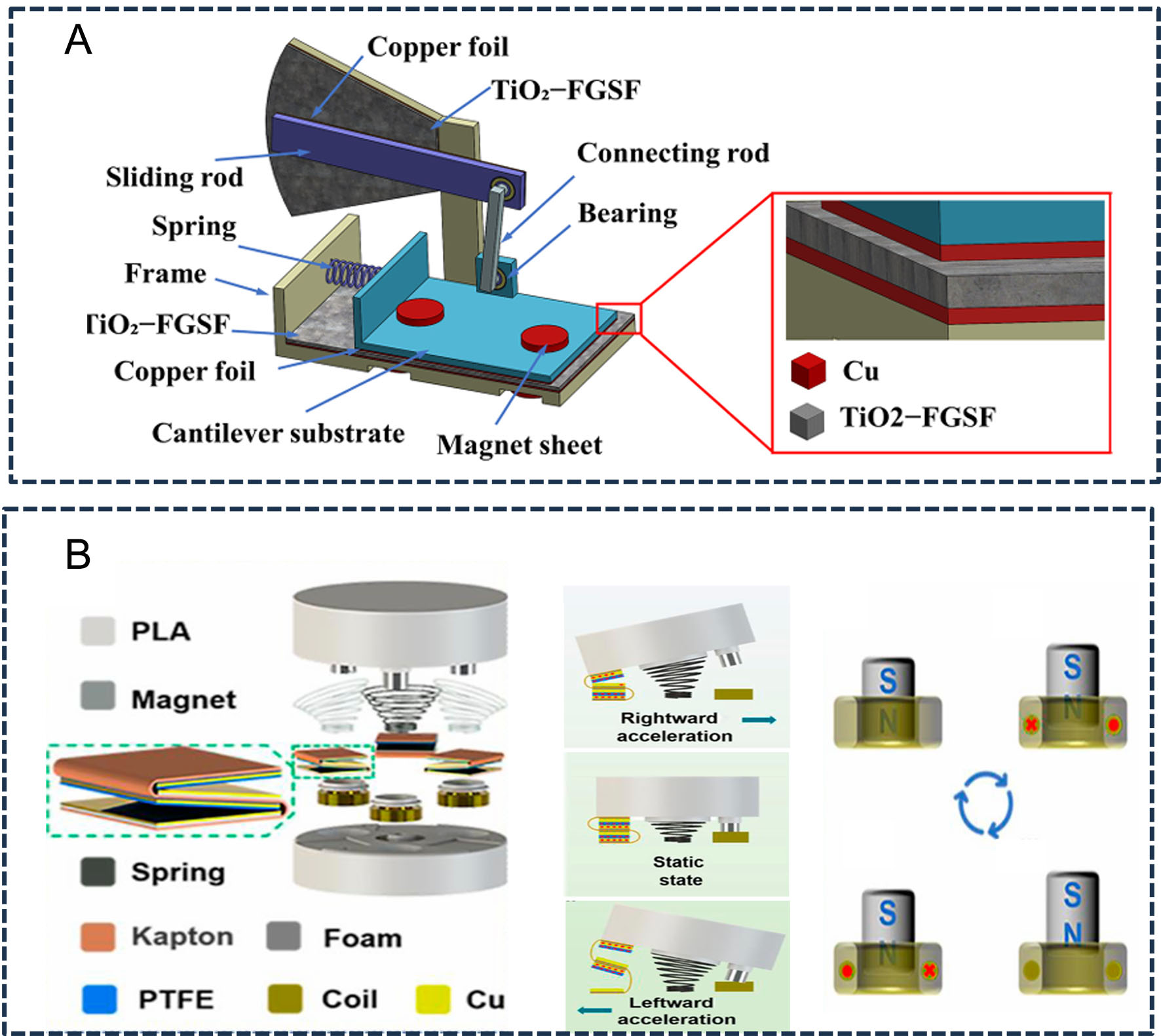

Wang et al. developed a TENG using a crank-rocker mechanism integrated with a spring cantilever structure (denoted as CRSC TENG) to efficiently harvest low-frequency, small-amplitude vibrations. Additionally, this structure was used to enable self-powered sensing applications primarily in the vertical direction transmitted through the spring cantilever and converted into rotational-sliding motion by the crank-rocker

Figure 3. (A) CR-SC TENG for dual-mode energy harvesting and vibration sensing. Used with permission[44]. Copyright 2024 by the authors (CC BY 4.0). (B) OD-HNG combining multilayer TENGs and EMGs with a tower spring for broadband vibration harvesting. Used with permission[45]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

The omnidirectional-hybrid nanogenerator (OD-HNG) integrates three multilayered zigzag TENGs and three EMG units coupled through a tower-shaped conical spring to efficiently harvest low-frequency vibration energy from random directions [Figure 3B][45]. The tower spring (with a height of 25 mm) provides structural stability and a large swing angle; therefore, the device can respond to both horizontal and vertical excitations. Moreover, the zigzag polyimide (PI)-Cu/PTFE-based multilayer TENG units (PI and PTFE thickness: 50 μm) increased the effective contact area, and the EMG units (magnet size: 10 mm× 10 mm) enhanced high-current output via magnet-coil motion. Frequency tests demonstrated effective energy harvesting within a broadband frequency range (0.4-10 Hz), with the TENG output peaking at 6 Hz (65 µW at 100 MΩ) and the EMG output reaching 6.8 mW at 150 Ω. The hybrid design broadened the operational bandwidth and enabled efficient conversion of micro-vibrations from multiple directions into electricity through complementary operation. Moreover, the TENG units performed optimally at low frequencies, and the EMG units increased output with high frequencies. In practical use, the OD-HNG charged a 1 mF capacitor to 1.75 V in 20 s when mounted on a bicycle and successfully powered 35 LEDs, a temperature sensor for real-time environmental monitoring, and an electronic watch. These findings indicate that the swing-structured hybrid nanogenerator provides an efficient and stable energy harvesting strategy for low-frequency mechanical motion. However, its output performance is affected by swing amplitude and magnetic coupling strength, and further optimization of the mechanical structure and magnetic configuration is needed to enhance energy conversion efficiency.

Other spring structures

A self-powered vibration sensor (AV-TENG) with a magnetic spring structure enabled real-time monitoring and generated early warnings for UAVs[16]. This sensor employed a vertical contact-separation mode, in which a silicone film on the vibrating plate contacted and separated from a PI-Cu electrode on the base. Magnetic repulsion between permanent magnets replaced conventional mechanical springs, eliminating mechanical fatigue and improving stability for long-term UAV operation. The optimized structure

Tan et al. developed a magnetic tri-stable TENG (MT-TENG) that used a negative-stiffness mechanism induced by a magnetic spring configuration to efficiently harvest low-frequency vibration energy[46]. The design integrated a sliding-mode triboelectric structure composed of Cu and fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) films with a proof mass, dual springs, and three strategically arranged magnets, forming a tri-stable potential profile. This configuration enabled large-amplitude inter-well oscillations under small external excitations, considerably amplifying relative motion between the triboelectric layers and improving charge transfer. Experimental characterization showed a transition from small intra-well oscillation between

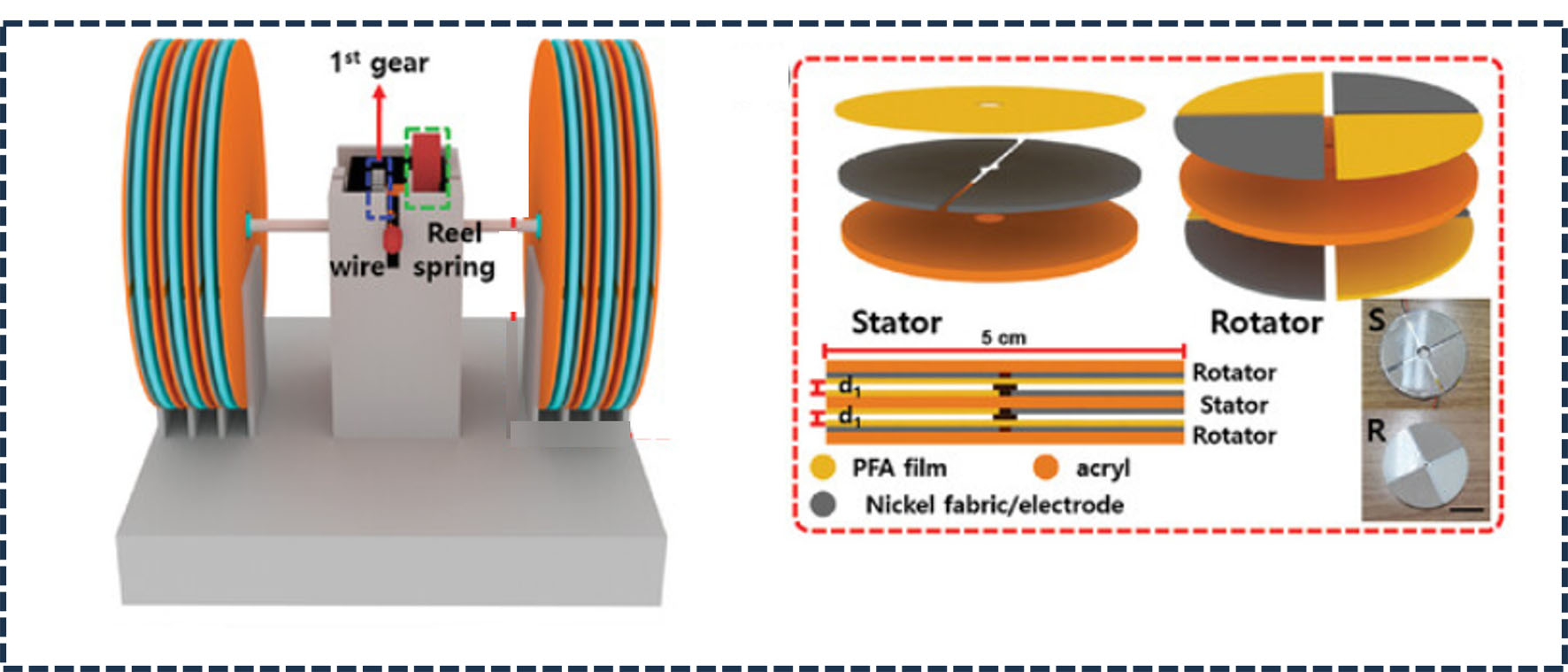

Hwang et al. developed an integrated power generation, conversion, and communication system (power generation, conversion, and communication system (PGCS)-temperature monitoring system (TMS)-passive near-field communication (pNFC)) based on TENGs for sustainable building energy applications [Figure 4][47]. The system comprised three subsystems. The first subsystem was a mechanical regulation system (MRS) that contained a reel spring, gear train, and automatic switch to convert low-frequency (1-2 Hz) inputs such as door opening and closing or bicycle motion into high-frequency (> 1 kHz) oscillations. The integrated PGCS-TMS-pNFC system features a mechanical regulation module (MRS) with overall dimensions of 80 mm × 80 mm ×

Figure 4. Integrated TENG-based PGCS-TMS-pNFC system for smart building energy and wireless sensing applications. Used with permission[47]. Copyright 2024 John Wiley and Sons.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVE

S-TENGs have been widely adopted to power autonomous electronic systems and construct battery-free sensing platforms in diverse real-world scenarios. They can effectively overcome the limitations of low-frequency and low-amplitude vibration energy harvesting [Table 1]. Spring mechanisms considerably enhance charge transfer and broaden operational bandwidth by enabling resonance tuning, amplifying relative displacement, and strengthening contact-separation cycles. Magnetic spring mechanisms offer unique benefits such as tunable stiffness, nonlinear response, fatigue-free operation, and long-term durability. Adjusting magnet spacing or geometry enables precise resonance matching, whereas negative-stiffness and tri-stable configurations broaden bandwidth and amplify oscillations under weak excitations. Structural designs including linear and cantilever systems, as well as tower, helical, and multi-DOF configurations, have demonstrated high power density and stability. Although spring structures are not essential, adding them can enhance TENG energy conversion efficiency. Many current S-TENG designs are optimized for laboratory-scale vibrations. In contrast, actual environmental sources often provide only low-amplitude excitations, making it difficult to sustain sufficient output for continuous IoT operation. This gap indicates that further structural optimization - such as enhancing displacement amplification, resonance tuning, or implementing multi-stable configurations - is essential to improve energy conversion efficiency under realistic vibration levels and to ensure reliable power delivery in practical deployments.

Comparison of TENGs based on their working mechanisms, operating modes, output voltages, materials, and resonance frequencies

| Spring type | Operating mode | Resonance frequency | Output voltage/power | Output voltage performance per unit device volume | Materials | Ref. |

| Linear spring | Sliding | 10.4 Hz | 632 Vpeak | 5.85 Vpeak/cm3 | PTFE, aluminum alloy | [24] |

| Linear spring | Contact/separation | 13 Hz | 16 mWpeak | 0.244 VRMS/cm3 | PFA, ENIG-plated copper | [25] |

| Linear spring | Contact/separation | 9.12, 25.55, and 36.87 Hz | - | - | PFA, Al | [26] |

| Linear spring | Contact/separation | 4.75 Hz | 562.8 VPEAK | 0.143 Vpeak/cm3 | PTFE, Cu | [43] |

| Cantilever and spring | Contact/separation, sliding | 35 Hz | 150 Vpeak | 62.2 W/m3 | TiO2-doped silicone, Cu | [44] |

| Tower or helical spring | Contact/separation | 6 Hz | 65 µWpeak | - | polyimide-Cu/PTFE | [45] |

| Magnet spring | Contact/separation | 43.6 Hz | 10.9 Vpeak | 0.346 Vpeak/cm3 | Polyimide, Cu, silicone | [16] |

| Magnet spring | Sliding | 6 Hz | 240 Vpeak | - | FEP, Cu | [46] |

| Reel spring | Sliding | - | 423 VRMS | 0.96 VRMS/cm3 | PFA, Ni | [47] |

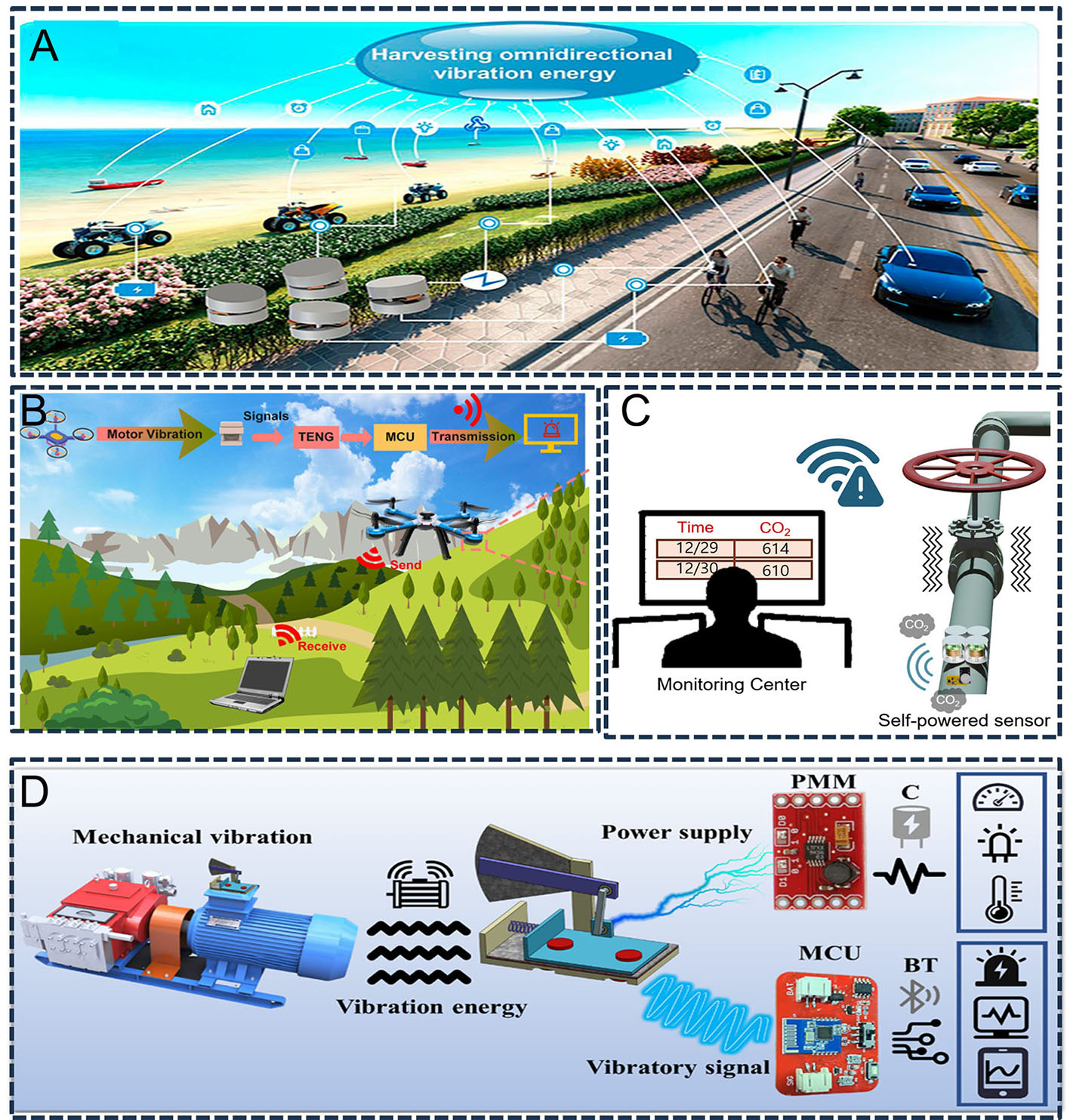

Several studies have demonstrated that S-TENGs facilitate self-powered electronics for future applications [Figure 5][16,25,44,45]. One such application involved powering portable electronics, environmental sensors, and multiple LEDs in mobile platforms such as bicycles and vehicles. In another application, fine mechanical vibrations from industrial pipelines drove a wireless carbon dioxide monitoring system, enabling periodic indoor air quality reporting via Bluetooth communication without requiring external power supplies or battery replacement. Another application involved industrial equipment monitoring, in which low-frequency vibrations from air compressors were harvested to generate electrical energy to power monitoring modules under real-time vibration sensing for predictive maintenance and fault diagnosis. These applications demonstrate that S-TENGs can effectively convert weak or broadband vibrations into usable electrical energy, supporting sustainable, maintenance-free operation of distributed sensing networks and autonomous electronic devices. Future progress will depend on structural innovations that maximize energy generation under weak vibrations, especially using spring architectures that can amplify displacement and maintain resonance at low frequencies. The use of magnetic spring configurations, owing to their tunable stiffness and multi-stable dynamics, can be distinguished as a central strategy for achieving high output performance and advancing TENGs for application in practical, durable, and self-powered systems. Furthermore, incorporating a spring structure amplifies vibration-induced deformation, and pre-formed microstructures on the triboelectric layer surfaces further enhance deformation concentration, maximizing charge transfer and improving energy conversion efficiency. Also, magnetic composite materials, nanofiber structures, and corona charge injection methods can facilitate additional magnetic resonance behaviors[48-51].

Figure 5. Application demonstrations of S-TENGs. (A) Omnidirectional hybrid energy harvesting for portable electronics. Used with permission[45]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. (B) UAV vibration sensing and early warning generation. Used with permission[16]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier. (C) Pipeline-driven wireless carbon dioxide monitoring. Used with permission[25]. Copyright 2025 Elsevier. (D) Industrial equipment monitoring with predictive maintenance. Used with permission[44]. Copyright 2024 by the authors (CC BY 4.0).

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Writing, review & editing: Tiruneh, D. M.; Ryu, H.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was supported by the Korean Fund for Regenerative Medicine (KFRM) grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Health & Welfare). (KFRM 25A0105L1).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Roselli, L.; Borges, Carvalho. N.; Alimenti, F.; et al. Smart surfaces: large area electronics systems for internet of things enabled by energy harvesting. Proc. IEEE. 2014, 102, 1723-46.

2. Zahid Kausar, A.; Reza, A. W.; Saleh, M. U.; Ramiah, H. Energizing wireless sensor networks by energy harvesting systems: scopes, challenges and approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2014, 38, 973-89.

3. Kansal, A.; Hsu, J.; Srivastava, M.; Raghunathan, V. Harvesting aware power management for sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference on Design Automation - DAC ’06. New York: ACM Press, 2006; p. 651.

4. Ali, A.; Shaukat, H.; Elahi, H.; et al. Advancements in energy harvesting techniques for sustainable IoT devices. Results. Eng. 2025, 26, 104820.

5. Vahidhosseini, S. M.; Rashidi, S.; Ehsani, M. H. Enhancing sustainable energy harvesting with triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs): advanced materials and performance enhancement strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2025, 216, 115663.

6. Muzafar, S. Energy harvesting models and techniques for green IoT: a review. In: Ponnusamy V, Zaman N, Jung LT, Amin AHM, editors. Role of IoT in green energy systems. IGI Global; 2021. pp. 117-43.

7. Lu, M.; Fu, G.; Osman, N. B.; Konbr, U. Green energy harvesting strategies on edge-based urban computing in sustainable internet of things. Sustain. Cities. Soc. 2021, 75, 103349.

8. Lewis, N. S.; Nocera, D. G. Powering the planet: chemical challenges in solar energy utilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006, 103, 15729-35.

9. Cheng, T.; Shao, J.; Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Rev. Methods. Primers. 2023, 3, 220.

10. Wu, C.; Wang, A. C.; Ding, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerator: a foundation of the energy for the new era. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2019, 9, 1802906.

11. Park, H.; Cho, Y.; Yoon, H.; Ryu, H. Highly compact rotational triboelectric nanogenerator for self-powered BLE operation and self-rechargeable system. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 164941.

12. Zhu, G.; Peng, B.; Chen, J.; Jing, Q.; Lin, Wang. Z. Triboelectric nanogenerators as a new energy technology: from fundamentals, devices, to applications. Nano. Energy. 2015, 14, 126-38.

13. Tian, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z. L. Environmental energy harvesting based on triboelectric nanogenerators. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 242001.

14. Kaneko, S.; Nakamura, T.; Inada, F.; et al. Chapter 5 - Vibration induced by pressure waves in piping. In: Flow-induced Vibrations. Elsevier; 2014. pp. 197-275.

15. Bamidele, O. E.; Ahmed, W. H.; Hassan, M. Two-phase flow induced vibration of piping structure with flow restricting orifices. Int. J. Multiphas. Flow. 2019, 113, 59-70.

16. Wang, K.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Self-powered system for real-time wireless monitoring and early warning of UAV motor vibration based on triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano. Energy. 2024, 129, 110012.

17. Almardi, J. M.; Bo, X.; Shi, J.; Firdous, I.; Daoud, W. A. Drone rotational triboelectric nanogenerator for supplemental power generation and RPM sensing. Nano. Energy. 2025, 135, 110614.

18. Guan, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, K.; et al. Wireless online rotation monitoring system for UAV motors based on a soft-contact triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 46516.

19. Sun, R.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, L. Ultra-low frequency vibration energy harvesting: mechanisms, enhancement techniques, and scaling laws. Energy. Convers. Manag. 2023, 276, 116585.

20. Ashraf, K.; Khir, M. H. M.; Dennis, J. Energy harvesting in a low frequency environment. In 2011 National Postgraduate Conference; 2011, pp. 1-5.

21. Yang, X.; Lai, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Ding, H. On a spring-assisted multi-stable hybrid-integrated vibration energy harvester for ultra-low-frequency excitations. Energy 2022, 252, 124028.

22. Xu, M.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. A soft and robust spring based triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting arbitrary directional vibration energy and self‐powered vibration sensing. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2018, 8, 1702432.

23. Wu, C.; Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Zi, Y.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z. L. A spring-based resonance coupling for hugely enhancing the performance of triboelectric nanogenerators for harvesting low-frequency vibration energy. Nano. Energy. 2017, 32, 287-93.

24. Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Zheng, H.; et al. A spring-assisted hybrid triboelectric-electromagnetic nanogenerator for harvesting low-frequency vibration energy and creating a self-powered security system. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 14747-54.

25. Tiruneh, D. M.; Jang, G.; Kwon, K.; Ryu, H. Highly compact inertia-driven triboelectric nanogenerator for self-powered wireless CO2 monitoring via fine-vibration harvesting. Nano. Energy. 2025, 138, 110872.

26. Kim, J.; Lee, D.; Ryu, H.; et al. Triboelectric nanogenerators for battery‐free wireless sensor system using multi‐degree of freedom vibration. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2301427.

27. Chen, J.; Zhu, G.; Yang, W.; et al. Harmonic-resonator-based triboelectric nanogenerator as a sustainable power source and a self-powered active vibration sensor. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6094-9.

28. Ozen, A.; Ozel, F.; Kınas, Z.; Karabiber, A.; Polat, S. Spring assisted triboelectric nanogenerator based on sepiolite doped polyacrylonitrile nanofibers. Sustain. Energy. Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101492.

29. Wang, X.; Yin, G.; Sun, T.; Xu, X.; Rasool, G.; Abbas, K. Mechanical vibration energy harvesting and vibration monitoring based on triboelectric nanogenerators. Energy. Technol. 2024, 12, 2300931.

30. Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Xie, X.; Wu, J.; Shi, Q. Self-powered sensing and wireless communication synergic systems enabled by triboelectric nanogenerators. Nanoenergy. Adv. 2024, 4, 367-98.

31. Xu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Cai, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Du, C. Performance enhancement of triboelectric nanogenerators using contact-separation mode in conjunction with the sliding mode and multifunctional application for motion monitoring. Nano. Energy. 2022, 102, 107719.

32. Liu, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. L. Recent advances in high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 11698-717.

33. Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as self-powered active sensors. Nano. Energy. 2015, 11, 436-62.

34. Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Niu, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z. L. Freestanding triboelectric-layer-based nanogenerators for harvesting energy from a moving object or human motion in contact and non-contact modes. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2818-24.

35. Yuan, M.; Yu, W.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Triboelectric nanogenerator metamaterials for joint structural vibration mitigation and self-powered structure monitoring. Nano. Energy. 2022, 103, 107773.

36. Choi, D.; Lee, Y.; Lin, Z. H.; et al. Recent advances in triboelectric nanogenerators: from technological progress to commercial applications. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 11087-219.

37. Liang, X.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Y.; et al. Spherical triboelectric nanogenerator based on spring-assisted swing structure for effective water wave energy harvesting. Nano. Energy. 2021, 83, 105836.

38. Wang, Z. L. From contact electrification to triboelectric nanogenerators. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2021, 84, 096502.

39. Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as new energy technology and self-powered sensors - principles, problems and perspectives. Faraday. Discuss. 2014, 176, 447-58.

40. Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Deng, L.; et al. Efficient electrical energy conversion strategies from triboelectric nanogenerators to practical applications: a review. Nano. Energy. 2024, 132, 110383.

41. Zhang, C.; He, L.; Zhou, L.; et al. Active resonance triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting omnidirectional water-wave energy. Joule 2021, 5, 1613-23.

42. Yu, J.; Kim, W.; Oh, S.; Bhatia, D.; Kim, J.; Choi, D. Toward optimizing resonance for enhanced triboelectrification of oscillating triboelectric nanogenerators. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green. Technol. 2023, 10, 409-19.

43. Jiang, T.; Yao, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, T.; Wang, Z. L. Spring-assisted triboelectric nanogenerator for efficiently harvesting water wave energy. Nano. Energy. 2017, 31, 560-7.

44. Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Sun, T.; Yin, G. A triboelectric nanogenerator utilizing a crank-rocker mechanism combined with a spring cantilever structure for efficient energy harvesting and self-powered sensing applications. Electronics 2024, 13, 5032.

45. Cao, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Han, C.; et al. Hybrid triboelectric-electromagnetic nanogenerator based on a tower spring for harvesting omnidirectional vibration energy. ACS. Appl. Nano. Mater. 2022, 5, 11577-85.

46. Tan, D.; Ou, X.; Zhou, J.; et al. Magnetic tri-stable triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting energy from low-frequency vibration. Renew. Energy. 2025, 243, 122517.

47. Hwang, H. J.; Kwon, D.; Kwon, H.; Shim, M.; Baik, J. M.; Choi, D. Integrated system of mechanical regulator and electrical circuitry on triboelectric energy harvesting with near‐field communication for low power consumption. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2025, 15, 2400481.

48. Wang, D.; Zhang, D.; Li, P.; Yang, z.; Mi, Q.; Yu, L. Electrospinning of flexible poly(vinyl alcohol)/MXene nanofiber-based humidity sensor self-powered by monolayer molybdenum diselenide piezoelectric nanogenerator. Nano-Micro. Lett. 2021, 13, 57.

49. Yi, N.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; et al. Multi‐functional Ti3C2Tx‐Silver@Silk nanofiber composites with multi‐dimensional heterogeneous structure for versatile wearable electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2412307.

50. Chen, J.; Wu, K.; Gong, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Guo, H. A magnetic-multiplier-enabled hybrid generator with frequency division operation and high energy utilization efficiency. Research 2023, 6, 0168.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].