In situ engineering of pyrrolic-N-dominated solid electrolyte interphases for stable zinc metal anodes

Abstract

Metallic zinc anodes are promising candidates for aqueous batteries due to their high abundance, low cost, and environmental friendliness. However, challenges such as dendrite formation, hydrogen evolution side reactions, and irreversible corrosion hinder their practical application. In this study, we propose a pyrrolic nitrogen-enriched solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer to overcome these limitations and achieve a stable, dendrite-free zinc anode. By leveraging molecular functionalization, pyrrolic nitrogen facilitates uniform zinc deposition, suppresses unfavorable side reactions, and enhances the overall anode stability. Systematic experimental validation reveals that the engineered SEI achieves remarkable electrochemical performance, maintaining over 95% Coulombic efficiency and delivering long-term cycling stability beyond 500 cycles in an aqueous environment. Further computational simulations elucidate the synergistic interactions between pyrrolic nitrogen and zinc ions, offering deep insights into the underlying mechanisms of interphase stabilization. This work not only addresses the primary bottlenecks of zinc anodes but also establishes a scalable design framework for next-generation aqueous zinc batteries, enabling both improved durability and higher efficiency for real-world applications.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The depletion of fossil fuel resources, along with escalating environmental concerns, has significantly increased the demand for clean and sustainable energy solutions. Although renewable energy sources offer substantial promise, their intermittent and variable nature underscores the need for efficient energy storage and conversion technologies to ensure their reliable integration into large-scale power grids. Among various energy storage systems, lithium-ion batteries have become the dominant choice in consumer electronics and electric vehicles, leading the secondary battery market[1-3]. Despite their commercial success, lithium-ion batteries are plagued by high costs, limited safety, and constrained resource availability. These limitations have catalyzed interest in alternative energy storage technologies, with aqueous batteries emerging as strong contenders due to their high safety, low cost, excellent ionic conductivity, straightforward assembly, and compatibility with air-based manufacturing processes. As a result, aqueous batteries are regarded as one of the most promising candidates for large-scale grid energy storage applications[4-8].

Among various aqueous battery systems, zinc-ion batteries (ZIBs) have gained renewed attention as a viable option in recent years[9-12]. Zinc, as a negative electrode material, offers numerous advantages, including a high specific capacity of 820 mAh g-1, an impressive volumetric capacity of 5,854 mAh cm-3, a low redox potential [-0.762 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode (SHE)], a high hydrogen evolution overpotential, and reversible deposition/dissolution behavior[13]. These properties have established zinc as a cornerstone for water-based batteries since Alessandro Volta’s invention of the voltaic cell over two centuries ago. Various ZIB chemistries, such as Zn-MnO2[14], Zn-I2[15], and Zn-Br2[16], have been developed, with some achieving commercial success. Today, ZIBs continue to play a critical role in powering consumer electronics, accounting for approximately one-third of the global battery market. However, despite these advancements, significant challenges hinder the practical application of zinc anodes. Challenges such as dendrite formation, hydrogen evolution reactions (HER), and corrosion in acidic, neutral, and alkaline electrolytes hinder the capacity retention, safety, and lifespan of ZIBs[3]. These problems are exacerbated during the zinc plating/stripping process, where dendrite formation, interfacial parasitic reactions, and surface corrosion decrease Coulombic efficiency (CE) and lead to short cycle lives. Addressing these limitations requires innovative solutions to develop dendrite-free and stable zinc anodes for aqueous ZIBs.

To mitigate these challenges, a variety of strategies have been explored by researchers, including electrolyte additives[17,18], structural modifications of zinc electrodes, and protective coatings on zinc surfaces[19]. Various methods have been explored for stabilizing zinc anodes, including surface coating, alloying, and optimizing zinc structures such as artificial V2O5[20], ZnS[21], ZnMoO4[22], ZnSe[23], ZnO[24], and 3D Zn foil[25]. However, artificial coatings often suffer from poor compatibility with the zinc matrix, leading to their detachment during the stripping/plating process. In certain cases, the deposited Zn underneath the coating layer can weaken its adhesion to the zinc substrate, thereby diminishing its protective efficacy[26]. Given their compatibility with existing battery production technologies, electrolyte additives have emerged as one of the simplest and most effective strategies. To date, diverse additives have been developed, including inorganic additives [e.g., MnSO4[27], Zn3(PO4)2[28], trimethylethyl ammonium trifluoromethanesulfonate (Me3EtNOTF)[29], tetrasodium-ethylenediaminetetraacetate (Na4EDTA)[30]) and organic additives (e.g., dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)[31], poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO)[32], dimethylformamide (DMF)[33], polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)[34], bilirubin[35], hexaoxacyclooctadecane[36]]. Electrolyte additives generally contribute to dendrite suppression through mechanisms such as creating electrostatic shields, enhancing nucleation sites, reshaping zinc crystal orientations, and regulating solvation structures[17,37]. In addition, interface engineering has proven to be a crucial approach for enhancing the stability and performance of energy materials. Host-guest interactions are essential in directing the growth of inorganic nanostructures, allowing for the precise control of material morphology and electrochemical properties. Recent studies have demonstrated that engineering these interactions at the atomic level can significantly improve the efficiency of energy storage materials, such as Zn anodes in aqueous batteries. For instance, certain organic additives such as polyacrylamide can enhance the anode reversibility by modifying nucleation sites and overpotentials[38]. Cao et al.[31] reported DMSO, as an electrolyte additive, to form solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), which consists of Zn12(SO4)3Cl3(OH)15·5H2O. Wang et al.[39] introduced N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP) into the electrolyte in situ creating a contact N-rich SEI layer on Zn anodes. Huang et al.[40] demonstrated that trans-butenedioic acid (fumaric acid) improves the formation of favorable interfacial structures, enhancing Zn deposition and improving full cell cycling stability. However, these studies have yet to fully explore the atomic-level regulation of the SEI. While graphitic-N and pyridinic-N functionalities have been explored for Zn ion storage and SEI modification, their use still presents challenges such as weak interaction with Zn2+ and higher nucleation barriers[12,39]. In contrast, pyrrolic-N offers a more favorable binding energy with Zn2+, functioning as a stronger Lewis base, which not only lowers the nucleation barrier but also enables more uniform Zn deposition and prevents dendrite formation[41]. This aspect has not been extensively explored in previous studies, underscoring the need for this approach in the field of Zn anode protection. By enriching pyrrolic-N species within the SEI, our strategy delivers a unique interphase chemistry that couples strong Zn2+ binding, dendrite suppression, and corrosion resistance. This essential difference highlights the novelty of our approach and its potential to provide a scalable framework for SEI design in aqueous Zn batteries.

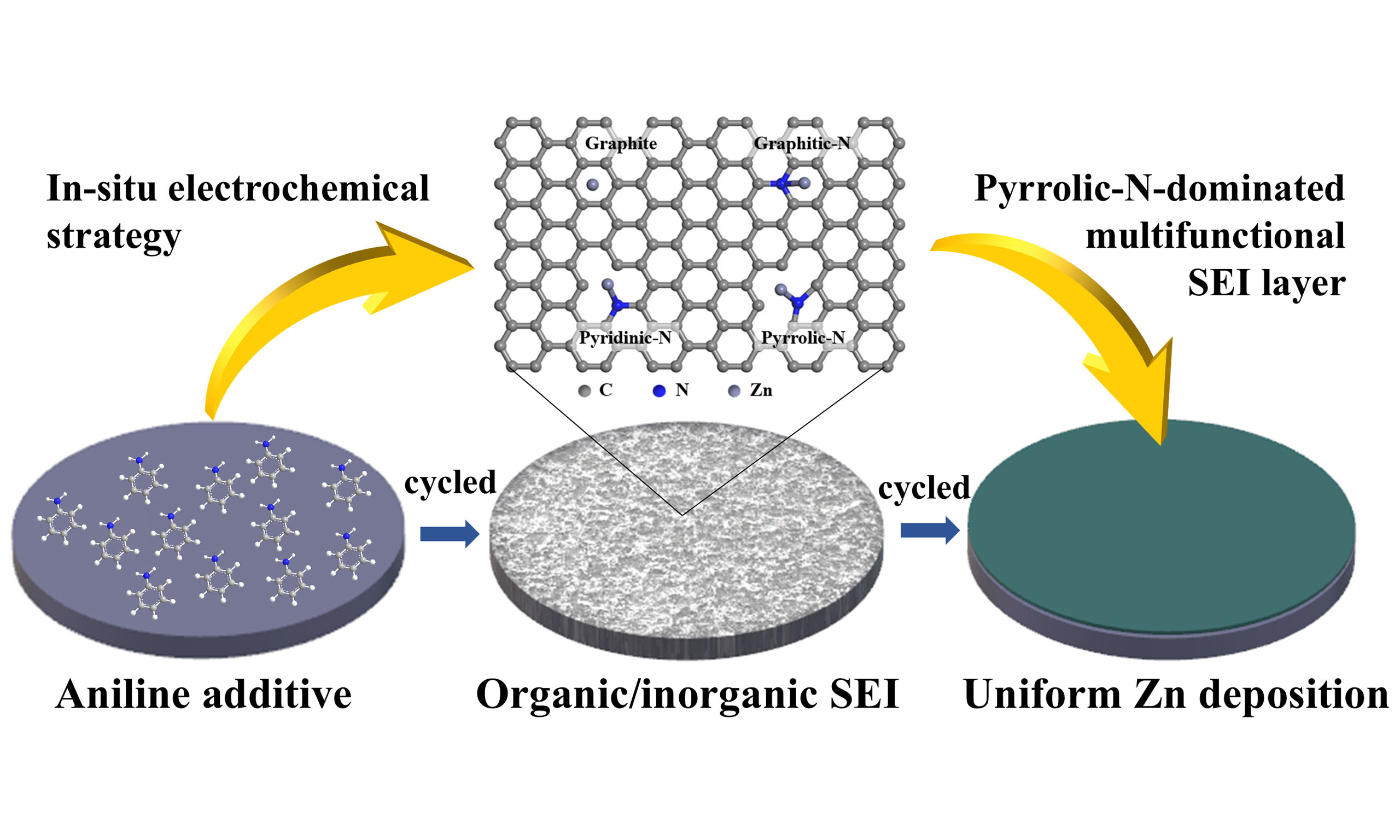

In this study, a pyrrolic-N-dominated organic/inorganic SEI was successfully developed on zinc anodes through an in situ electrochemical strategy during battery working. This multifunctional SEI acts as a protective barrier, preventing corrosion and electrolyte breakdown while maintaining excellent interfacial stability. By promoting uniform Zn2+ distribution and harmonized ion migration, the SEI facilitates

EXPERIMENTAL

Fabrication of NH4V4O10

NH4V4O10 (NHVO) powder was synthesized via a hydrothermal method. Initially, ammonium metavanadate and oxalic acid dihydrate were dissolved in deionized water at a certain ratio[42]. The solution was stirred at

Materials characterization

The crystal structure of the synthesized NHVO was analyzed by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) using a Bruker AXS D8 Advance diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). The morphology of the samples was observed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi S-4700; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The zinc plating process was visualized in situ using an optical microscope (Nikon, LV-LH50PC; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan)[43]. The wettability of bare Zn and Aniline-modified Zn was determined using a contact angle measurement system (ramé-hart Model 250; Ramé-Hart Instrument Co., Succasunna, NJ, USA). In addition, 3D surface height images were obtained using a 3D scanning confocal laser microscope (Keyence, VK-2000; Keyence, Osaka, Japan). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) tests were conducted on a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to characterize the interfacial structure of cycled Zn anodes. The Ar+ sputtering etch rate was ~0.24 nm s-1, allowing depth-resolved analysis of the SEI composition. Complementary time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS, nano TOF III; Ulvac-PHI, Chigasaki, Japan) was employed to resolve the depth distribution of organic and inorganic fragments within the SEI.

Electrochemical measurements

CR2032-type coin cells (20 mm diameter, 3.2 mm thickness) were assembled under ambient conditions, leveraging the stability of the Zn anodes. Zn||Ti half-cells were fabricated and tested, where Zn served as the anode and Ti foils were used as the working electrode. The assembled batteries were discharged at a constant current for 30 min and subsequently recharged to a cutoff voltage of 1.0 V. To evaluate the cycling stability of the zinc anode, Zn||Zn symmetric cells were subjected to constant current densities and areal capacities. For Zn||NHVO full batteries, cathodes were prepared using a mixture of NHVO (60 wt.%), carbon nanotubes (30 wt.%), and poly(vinylidene fluoride) (10 wt.%) with the mass loading ranging from 1.0 to 2.0 mg cm-2. Zinc foil (12 mm in diameter, 100 μm thick) and Ti foil (12 mm in diameter, 50 μm thick) were employed as the counter/reference electrodes and current collectors, respectively. A 2 M ZnSO4 aqueous solution was used as the electrolyte, while a glass fiber was adopted as the separator. To investigate the effect of aniline on the electrolyte, various concentrations of aniline (0.1, 0.6, and 2.0 mg mL-1) were added to the ZnSO4 solution. The assembled batteries were tested using a LANHE battery test system (CT-3001A, Wuhan, China) within a voltage range of 0.2-1.6 V (vs. Zn2+/Zn) at a given constant current density. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed within a potential window of 0.2 to 1.6 V, at a scan rate of 1-10 mV s-1. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted over a frequency range of 0.001 Hz to 105 Hz, with an applied alternating current (AC) voltage amplitude of 10 mV.

Theoretical calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) simulations were conducted using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) to investigate the electronic structure and interaction mechanisms of the system. The exchange-correlation interactions were modeled using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA), employing the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional to accurately describe the electronic properties. This computational approach enabled a detailed analysis of the material’s stability and reactivity at the atomic level, providing insights into its behavior in the context of the studied applications[44]. A five-layer 5 × 5 × 1 Zn (002) supercell with a 15 Å vacuum layer was constructed to model the Zn metal anodes. During the optimization process, the top two atomic layers were fully relaxed, while the bottom three layers were kept fixed to maintain the bulk structure. The adsorption energies (Eads) of aniline and H2O in the Zn model were obtained as Eads = EZn+X - EZn - EX, where EZn+X, EZn, and EX are the energies of the total system, Zn (002) surface, and aniline or H2O, respectively. The binding energy (Ebinding) between Zn2+, aniline, and H2O molecules was determined using the formula: Ebinding = Etotal - Ea - Eb, where Etotal represents the energy of the complete system, while Ea and Eb correspond to the energies of the individual components. This calculation allows for an

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The significant role of aniline in promoting stable zinc electrodeposition is highlighted in Supplementary Figure 1. In the absence of aniline, during the plating process in a bare ZnSO4 solution, Zn2+ ions exhibit random absorption on the zinc surface, followed by migration to the tips of nucleation sites, which results in dendrite formation. This phenomenon, as observed through scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

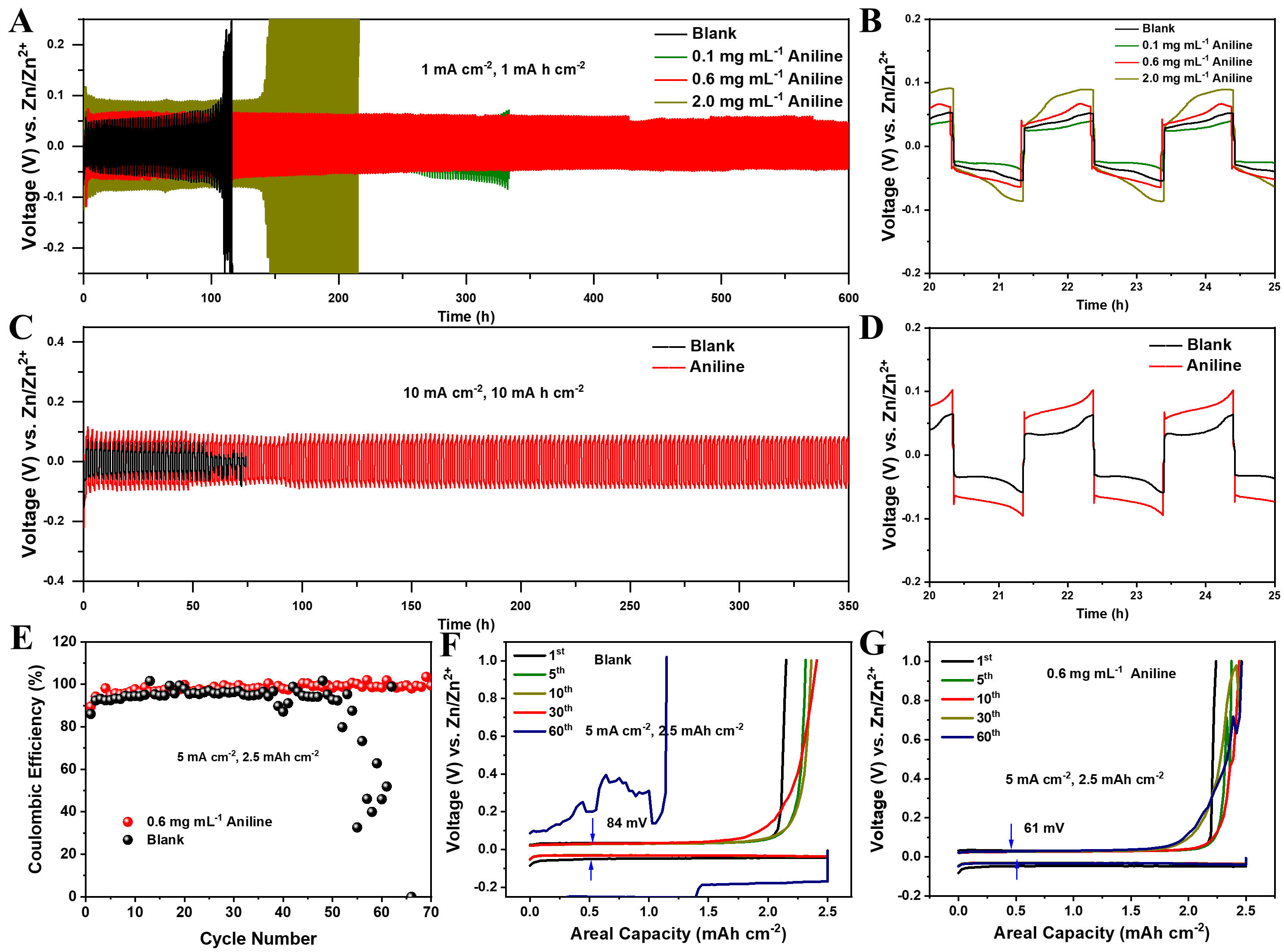

To evaluate the effectiveness of the aniline-derived organic-inorganic SEI in enhancing the electrochemical stability of Zn, long-term charge-discharge cycling tests were performed on Zn||Zn symmetric cells using the proposed electrolyte. The impact of aniline addition was also investigated. Under the current density of

Figure 1. Electrochemical performance of symmetric cells and half-cells. (A and B) Long-term cycling of symmetric cells in the baseline and proposed electrolytes at 1.0 mA cm-2 with 1.0 mA h cm-2; (C and D) Cycling performance at 10.0 mA cm-2 with 10.0 mA h cm-2; (E-G) CEs of Zn||Ti half cells and the corresponding charge-discharge voltage profiles during Zn plating/stripping at 5.0 mA cm-2 with 2.5 mA h cm-2.

The CEs of half-cells were evaluated in both the baseline and customized electrolytes [Figure 1E]. In the baseline electrolyte, the cell exhibited low and unstable CEs, averaging only 90.1%, primarily due to dendrite growth and side reactions. Over 50 cycles, the CE declined further, likely caused by competing hydrogen evolution during cycling. Conversely, the cell in the customized electrolyte showed significantly improved and stable performance, achieving an average CE of 99.5% over 70 cycles, with consistent voltage profiles throughout. The slightly reduced CE observed during the initial cycles was attributed to interfacial activation involving active Zn2+ species. These results demonstrate that the SEI facilitates uniform Zn plating/stripping, suppresses side reactions, and markedly enhances Zn utilization efficiency[23]. Furthermore, the half-cells without aniline display an overpotential of 84 mV [Figure 1F], whereas the cells with aniline show a markedly lower value of 61 mV [Figure 1G]. This reduction in overpotential directly indicates facilitated Zn nucleation, since the energy barrier for initial Zn2+ deposition is effectively lowered. The presence of pyrrolic-N species in the SEI provides abundant nucleation sites and enhances Zn2+ adsorption, thereby enabling uniform nucleation and subsequent dendrite-free growth.

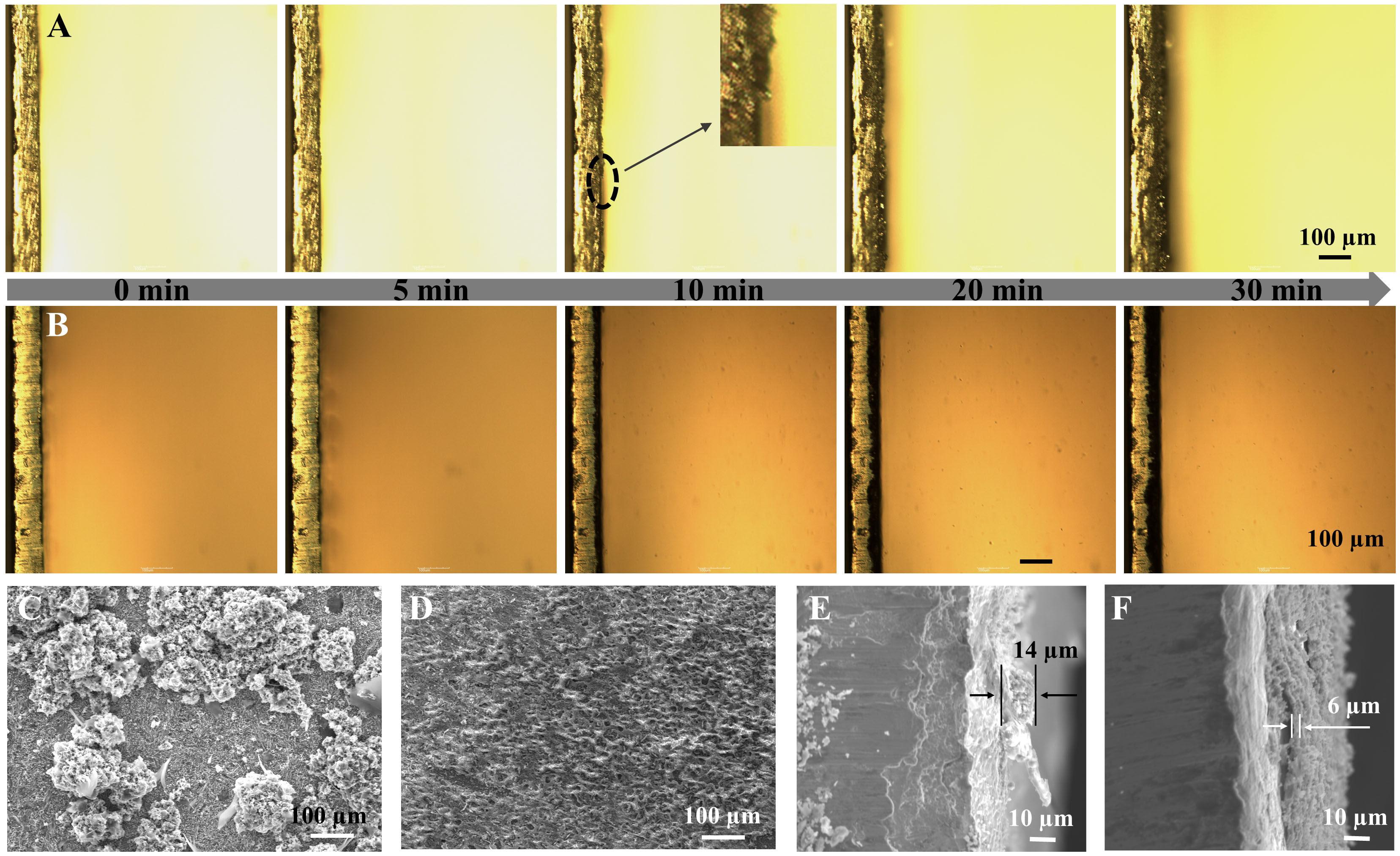

To visualize the behavior of Zn plating, we employed an optical microscope to track the in-situ evolution of surface morphology in Zn anodes within a sealed transparent cell at 10 mA cm-2. During the plating process for 0 min to 30 min [Figure 2A], the bare Zn anode displayed disordered and dendritic Zn growth. In contrast, the Aniline-Zn anode exhibited a dense and uniform plating surface, highlighting its ability to suppress dendrite formation and promote controlled Zn deposition [Figure 2B]. The absence of dendritic formations on the Aniline-Zn electrode even after 30 minutes indicates a significant improvement in Zn nucleation uniformity and the effective inhibition of dendrite growth by the aniline-derived SEI layer. The microstructural evolution of Zn electrodes following repeated cycling further highlights the advantages of the SEI coating. The baseline electrolyte behaved in chaotic dendritic clusters and thick layers of “dead” Zn, consistent with the polarization variations discussed earlier, indicating uncontrolled Zn deposition and persistent side reactions [Figure 2C][46]. In contrast, Zn electrodes cycled in the aniline-containing electrolyte exhibited a smooth and homogeneous surface characterized by a dense array of zinc flakes [Figure 2D]. These flakes were closely packed and aligned in a specific direction on the Zn electrode surface. Elemental analysis through energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) mapping [Supplementary Figure 5] showed a uniform distribution of C, N, O, S, and Zn, with calculated contents of 4.67%, 0.62%, 34.04%, 6.96%, and 53.72%, respectively (EDS spectrum in Supplementary Figure 6). Cross-sectional SEM images further illustrated the contrast in deposition morphology. Zn plated in the absence of aniline formed a thick and uneven layer of ~14 µm [Figure 2E], while the presence of aniline resulted in a compact and uniform Zn deposition layer with an average thickness of ~6 µm [Figure 2F]. This consistent nucleation and homogeneous Zn deposition morphology indicate an even flux of Zn2+ ions, demonstrating the effectiveness of the aniline-derived SEI layer in promoting stable and uniform Zn plating.

Figure 2. In situ optical microscopy images showing deposited Zn without (A) and with aniline (B) at 10 mA cm-2; Top-view and cross-section SEM of Zn anodes after 5 cycles without (C and E) and with (D and F) aniline at 10 mA cm-2. SEM: Scanning electron microscopy.

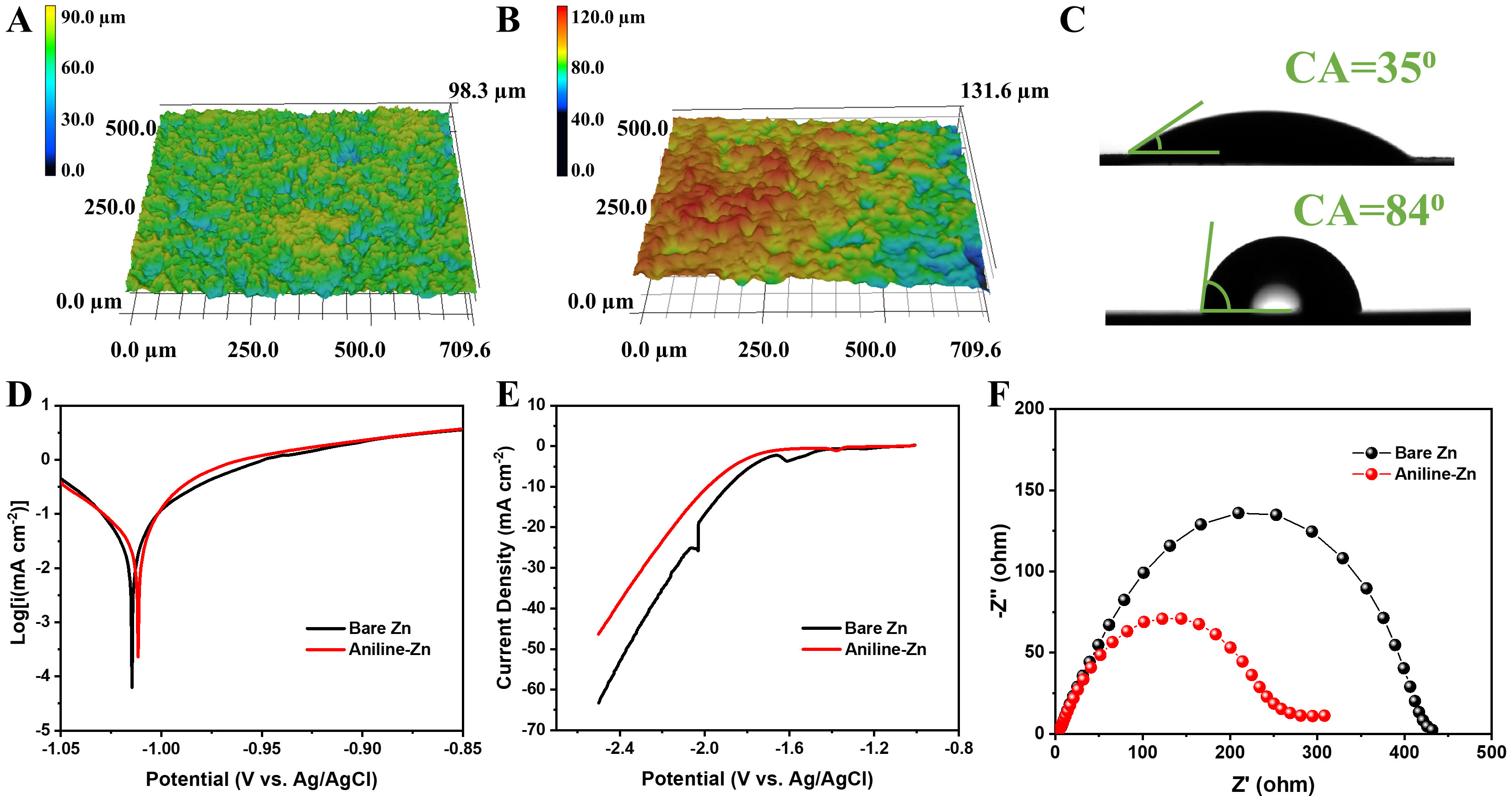

Three-dimensional laser microscopy images reveal that the Zn anode with aniline exhibits a height difference of 98.3 µm and a surface roughness of 7.2 µm [Figure 3A]. In comparison, the deposited Zn without aniline displays a significantly greater height difference of 131.6 µm and a surface roughness of 10.8 µm [Figure 3B]. These findings indicate that the Aniline-Zn anode achieves a notably smoother surface compared to the Zn without aniline. Furthermore, the hydrophobic nature of the Zn anode results in low wettability, as reflected by the high contact angle of 840 for the Zn anode without aniline [Figure 3C]. Conversely, the Aniline-Zn anode exhibits a substantially lower contact angle of 350, demonstrating enhanced wettability. The improved wettability, coupled with the in situ-formed SEI layer, significantly reduces interfacial energy barriers and ensures uniform Zn deposition. These results confirm that the Aniline-Zn anode outperforms the bare Zn anode in terms of surface smoothness and wettability. These enhancements, attributable to the in situ aniline layer, have the potential to significantly improve Zn plating performance and efficiency in aqueous systems[47].

Figure 3. 3D laser microscopy images of Zn anodes cycled with (A) and without (B) aniline additive; (C) Electrolyte Contact angle tests; (D) Tafel curves and (E) LSV curves; (F) EIS of the bare Zn and Aniline-Zn symmetric cells. EIS: Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy; LSV: linear sweep voltammetry; CA: contact angle.

Zinc anodes are prone to degradation due to Zn corrosion and H2 evolution processes. To evaluate the impact of the aniline-derived SEI on zinc corrosion, Tafel tests were conducted, as shown in Figure 3D. Compared to bare Zn, the aniline-coated Zn exhibited a slightly increased corrosion potential from -1.015 V to -1.011 V, indicating that the SEI layer effectively mitigates corrosion by acting as a protective barrier[28]. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was used to assess HER in a 1 M Na2SO4 solution, minimizing interference from zinc deposition. The addition of aniline increased the HER polarization, as evidenced by a decrease in the HER onset potential by approximately 80 mV, reflecting reduced water adsorption and suppressed HER activity [Figure 3E][48]. These findings illustrate the ability of the SEI layer to suppress HER and emphasize its protective role on the zinc surface. To further evaluate the stability enhancements provided by the SEI layer, EIS was conducted [Figure 3F]. The impedance of the cell without aniline was nearly double that of the aniline cell, underscoring the improved interfacial stability achieved with the SEI layer. Notably, the cell with aniline displayed a stable charge-transfer resistance of 260 Ω in the optimized electrolyte, with no significant increase in resistance observed at the initial state [Supplementary Figure 7]. CV analysis of half-cells revealed characteristic cathodic and anodic peaks. The aniline additive exhibited a shorter delay in the onset of the cathodic current, indicating a lower plating overpotential and a reduced Zn2+ deposition barrier [Supplementary Figure 8][49]. This suggests that the aniline-derived SEI layer not only minimizes unwanted side reactions but also significantly enhances interfacial stability and promotes efficient Zn plating/stripping.

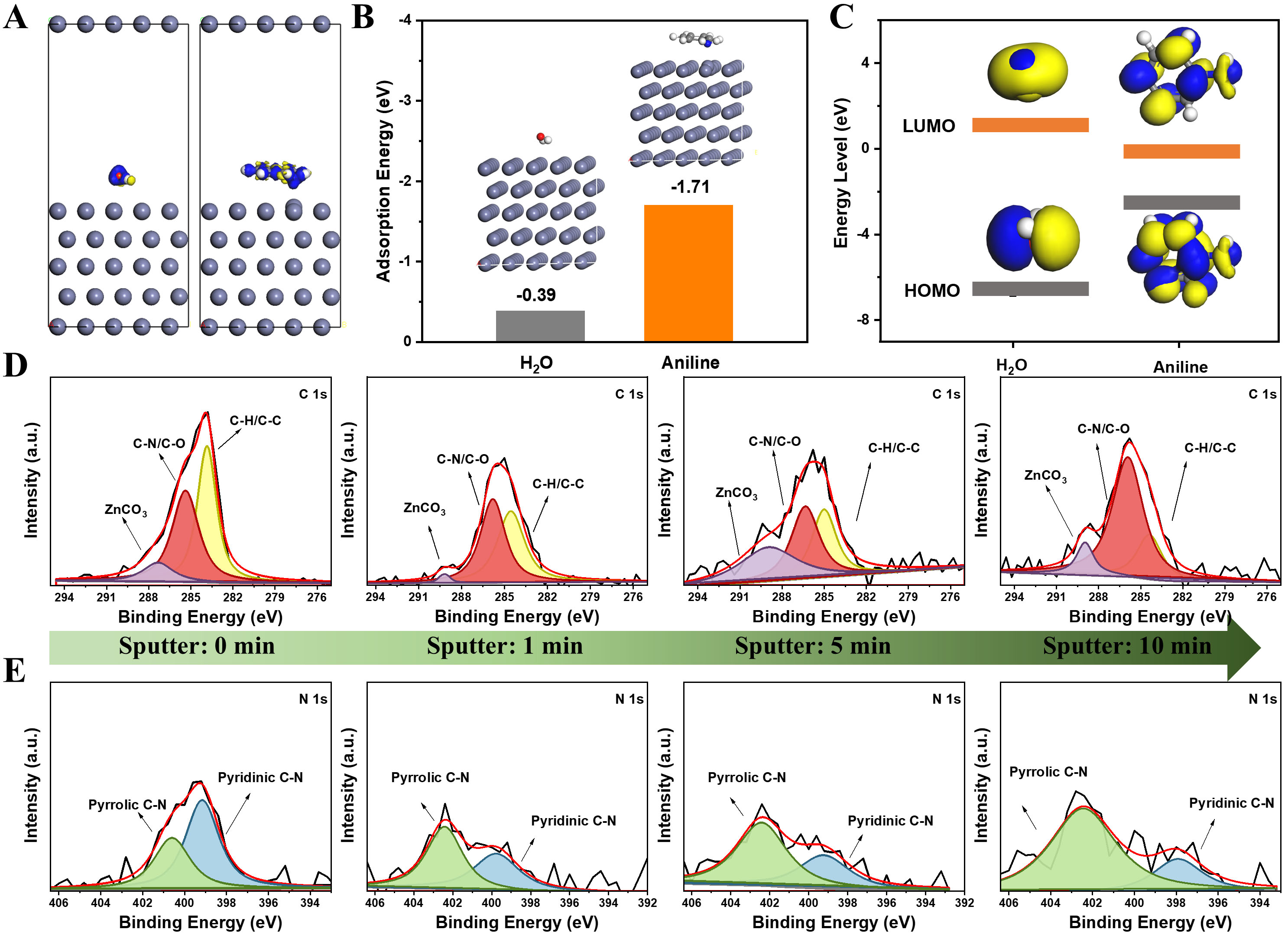

DFT calculations were performed to examine the interaction between Zn2+ and aniline. Electrostatic potential (ESP) mapping of aniline [Supplementary Figure 9] revealed a higher local electronegativity compared to H2O, suggesting that aniline is more likely to interact with Zn2+ in the solvation sheath. This observation aligns with the elemental electron densities presented in Supplementary Figure 10. A comparison of the binding energies for Zn-H2O and Zn-aniline interactions [Supplementary Figure 11] demonstrated that Zn2+ has a stronger affinity for aniline (-0.62 eV) than for H2O (-0.15 eV), confirming its preference for aniline. Charge transfer at the Zn-aniline interface is clearly illustrated in Figure 4A. Additionally, the adsorption energies of aniline on various Zn surface locations were computed, revealing that the interaction between Zn and aniline is consistently stronger than that between Zn and H2O, regardless of orientation (top, down, or parallel) [Supplementary Figure 12][50]. Notably, aniline adsorption energy reaches as high as -1.71 eV at a parallel site on the zinc surface [Figure 4B]. Detailed energy level calculations for the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) revealed that aniline exhibits a narrower electrochemical stability window (ESW) than H2O. This is demonstrated by its lower LUMO energy level of -0.25 eV, in contrast to the LUMO of H2O at 1.05 eV [Figure 4C][51-53]. To assess whether aniline decomposes on the Zn anode during cycling, comprehensive surface characterization of cycled electrodes will be necessary.

Figure 4. (A) Charge density difference distribution between Zn and aniline; (B) Adsorption energies on the Zn(002) crystal plane; (C) HOMO and LUMO energy levels; (D) In-depth high-resolution XPS of C 1s and (E) N 1s. HOMO: Highest occupied molecular orbital; LUMO: lowest unoccupied molecular orbital; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

Using Ar+ sputtering in conjunction with XPS, the elemental composition at the surface of the Zn anode was analyzed after ten cycles. The C 1s spectra displayed a peak at 284.3 eV, which is attributed to sp2 C-C/C-H groups [Figure 4D]. After one minute of sputtering, inorganic ZnCO3 was detected at 291.9 eV[54]. These species remained in the spectra even after extended Ar+ sputtering, indicating the formation of a robust layer on the Zn anode. This layer implies that the organic molecules detected within the electrode are not simply surface-adsorbed, but rather arise from the electrochemical decomposition of aniline. The N 1s spectra of the Zn anode cycled in the electrolyte with the additive of aniline showed signals for pyrrolic C-N (402.9 eV) and pyridinic C-N (395.1 eV) prior to sputtering [Figure 4E]. These signals are likely attributable to the decomposition and/or adsorption of aniline. As sputtering progressed, the intensities of pyrrolic C-N and pyridinic C-N species shifted, with pyrrolic C-N predominantly localized in the outer layer, while pyridinic C-N persisted in the inner layer. This observation suggests a layered distribution of decomposition products, with pyridinic C-N being more stable in the electrode's inner regions. Additionally, the O 1s and S 2p spectra showed signals for -SO4/C-O (531.8 eV) and organic-S species (168.2 eV), primarily localized in the inner layer [Supplementary Figure 13]. These signals are attributed to the electrochemical reduction of ZnSO4 in the electrolyte[39]. Collectively, the findings demonstrate that the electrochemical reduction of both aniline and ZnSO4 occurs on the complex Zn anode surface cycled in the aniline-containing electrolyte. To gain deeper insight into the SEI composition, TOF-SIMS was employed. As shown in Supplementary Figure 14, surface analysis revealed ionic fragments of SEI components, while depth profiling demonstrated a gradual decrease of CH- intensity with increasing sputtering depth, accompanied by a corresponding increase in ZnS signals. These results indicate that inorganic species such as ZnO and ZnS are preferentially enriched in the inner layer, where they stabilize the Zn anode and regulate Zn2+ transport. In contrast, organic fragments such as CH- and CN- dominate the outer layer, forming a compact organic-rich matrix that reinforces the mechanical robustness of the SEI. These findings emphasize that the pyrrolic-N-dominated organic-inorganic SEI, formed through the electrochemical decomposition of aniline, significantly facilitates Zn plating/stripping. This SEI plays a crucial role in enhancing the stability and electrochemical performance of the Zn anode[55]. It should be noted, however, that aniline is a toxic compound with potential environmental concerns. In this work, only small amounts were employed as electrolyte additives, minimizing the associated risks. Nevertheless, future efforts should explore greener molecular precursors with similar functionalities to construct pyrrolic-N-rich SEI layers, thereby ensuring both electrochemical performance and environmental sustainability.

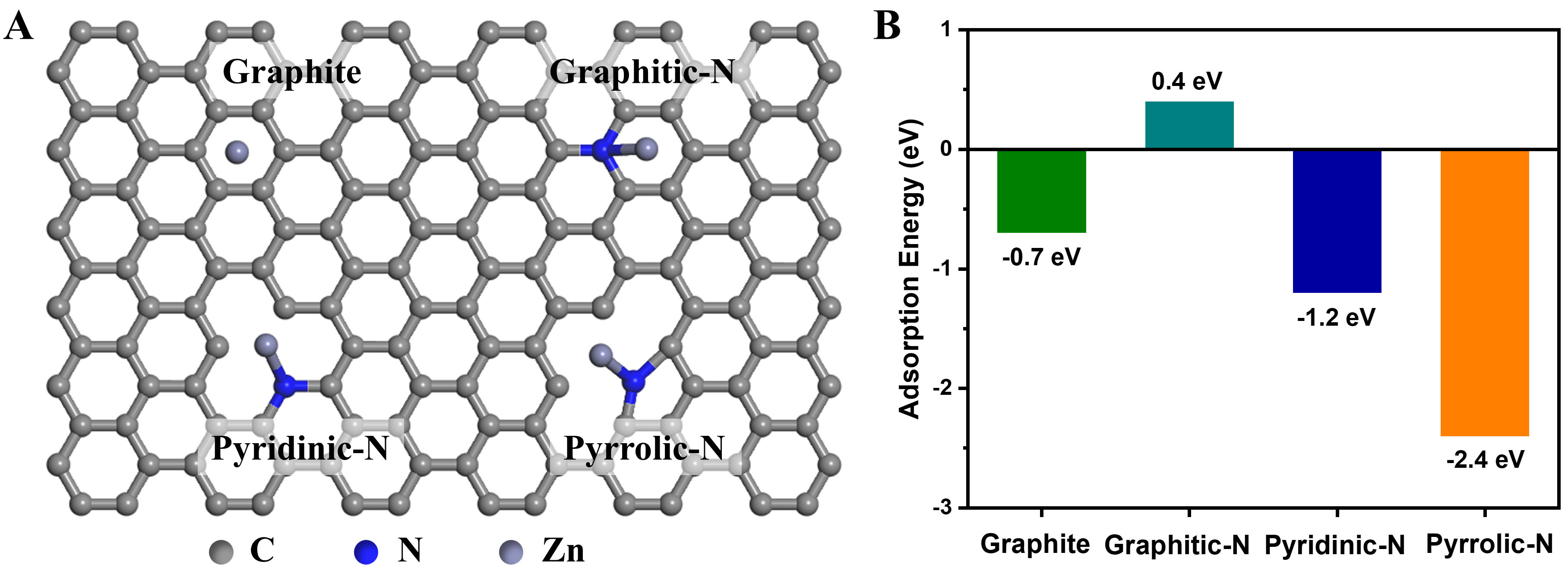

By analyzing the interaction between a single Zn atom and carbon atoms through DFT calculations, as shown in Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 15, intriguing insights into adsorption behaviors are revealed. The formation energy between a Zn atom and pristine carbon is relatively weak, measured at -0.7 eV [Figure 5B]. This can be attributed to the inherent stability of carbon atoms, which form six-membered rings with saturated electron orbitals [Supplementary Figure 15A], leaving no additional electrons available for Zn adsorption. Interestingly, the adsorption energy for graphitic-N exhibits a positive value of 0.40 eV. In this configuration, the graphitic-N atom connects to three carbon atoms within the stable six-membered ring [Supplementary Figure 15B]. The involvement of the N atom in π bond formation enhances local charge density and electrical conductivity. However, this increased interfacial energy and sizable nucleation barrier may lead to undesirable failure mechanisms. In contrast, the pyridinic-N atom, which is part of a

Figure 5. (A) Graphic of Zn site in graphite and different types of N-doped graphite structure: Graphite, Graphitic-N, Pyridinic-N, and Pyrrolic-N; (B) The formation energy of the Zn adsorption on four different structures.

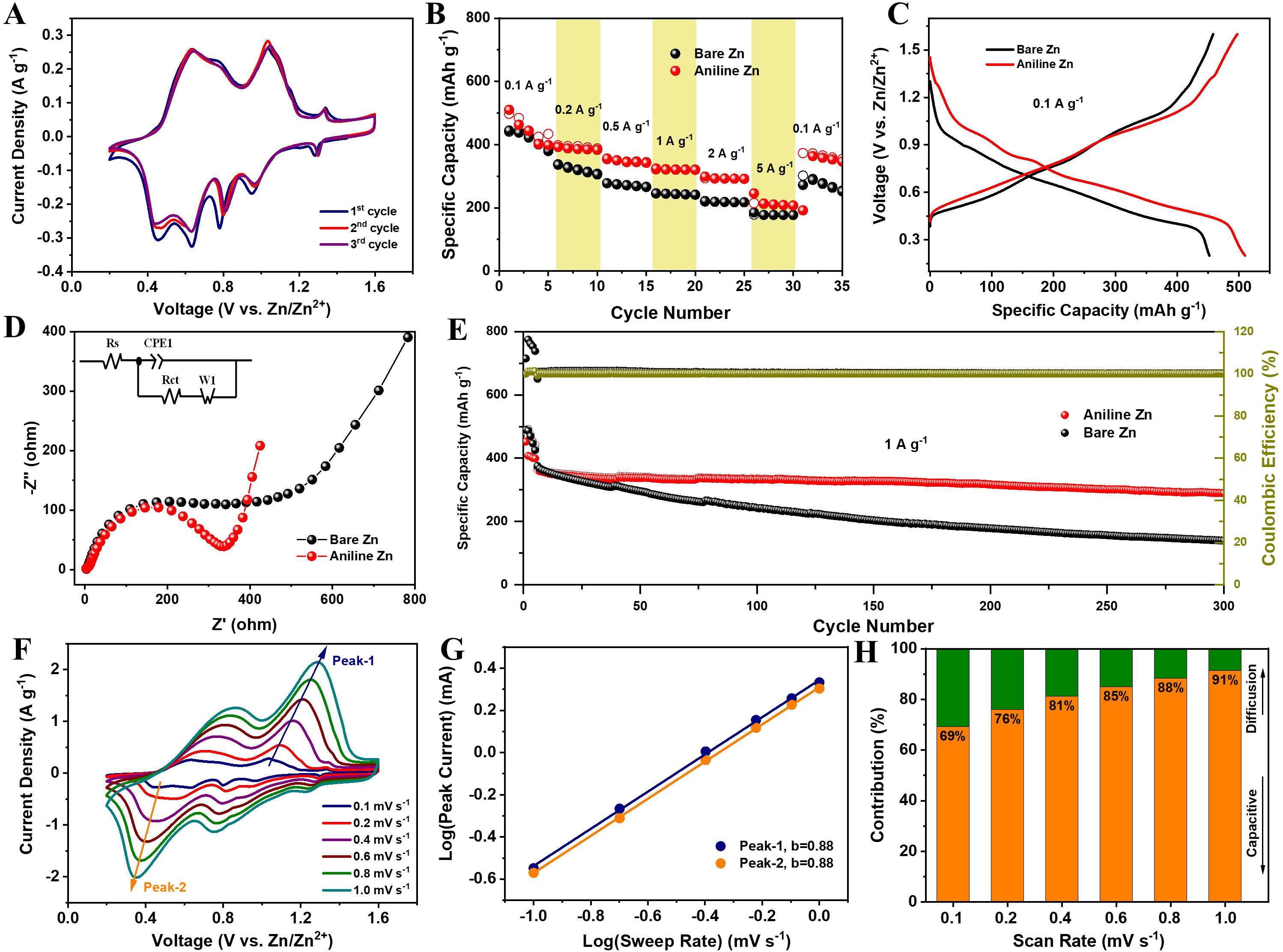

To explore the potential for alternative applications, we conducted a comprehensive electrochemical characterization of Zn||NHVO full batteries. The presence of micrometer-sized NHVO powder was confirmed via XRD [Supplementary Figure 16] and SEM [Supplementary Figure 17][58]. It should also be noted that NHVO serves as an efficient cathode owing to its layered crystal structure with open channels and large interlayer spacing, which can accommodate reversible Zn2+/H+ insertion and extraction. This structural feature not only contributes to the high capacity observed in the full cell but also synergizes with the

Figure 6. Electrochemical performance of Zn||NHVO full batteries. (A) CV measurement of full battery with aniline at 0.1 mV s-1; (B) Rate property; (C) Charge/discharge curves of full battery with aniline; (D) EIS; (E) Long-term cycling performance at a current density of

To elucidate the energy storage mechanism, CV curves at various scan rates were analyzed [Figure 6F]. Anodic and cathodic peak shifts, typical of pseudocapacitive behavior[61], were observed. The current response was fitted to the power law i = avb, where i is the peak current, v is the scan rate, a is a constant, and b = 0.5 indicates diffusion control (battery-like behavior) and b = 1.0 corresponds to surface capacitance (capacitor-like behavior). The b-values for peaks 1 and 2 in the protected Zn full cell were determined to be 0.88, suggesting a combination of ion diffusion and surface capacitance effects [Figure 6G]. The capacitive and diffusion contributions were quantified using i(V) = k1v + k2v1/2, where i(V) is the current response at a given potential V, v is the scan rate, and k1 and k2 reflect the respective capacitive and diffusion contributions. For instance, the capacitive contributions at 0.4 mV s-1 in the aniline-containing electrolyte [Supplementary Figure 18] represented 81% of the overall capacity, notably surpassing the 43% observed in the baseline electrolyte [Supplementary Figure 19]. Across other scan rates [Figure 6H], the capacitive contribution increased from 69% to 91% as the scan rate rose from 0.1 to 1.0 mV s-1, outperforming the baseline system. This improvement is attributed to reversible pseudocapacitive interactions between zinc ions and the negatively charged pyrrolic-N in the SEI layer, enabling rapid reaction kinetics and enhanced electrochemical performance[41].

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study presents a novel in situ electrochemical technique to construct a pyrrolic-N-dominated organic/inorganic SEI on zinc anodes, addressing critical challenges in aqueous ZIBs. The developed SEI exhibits exceptional multifunctionality, including enhanced hydrophilicity, superior Zn-ion conductivity, and robust adhesion properties. These features collectively suppress dendrite formation, reduce interfacial side reactions, and improve the overall stability of the zinc anode. Electrochemical evaluations reveal that the SEI-protected zinc anodes deliver outstanding performance. Depth-resolved XPS and TOF-SIMS analyses confirm a stratified SEI structure, where inorganic species (ZnO, ZnS) enrich the inner layer to stabilize Zn stripping/plating, while organic fragments (CH-, CN-) dominate the outer layer to form a compact and robust barrier. Complementary DFT calculations reveal that pyrrolic-N provides the most favorable adsorption energy among N-dopants, elucidating its crucial role in regulating Zn2+ flux and suppressing dendrite growth and parasitic hydrogen evolution. Beyond addressing immediate interfacial instability, this work highlights a mechanistic framework wherein molecularly engineered SEI chemistry, surface wettability, and interfacial adhesion are used to achieve durable Zn anodes. These insights provide guiding principles for rational SEI design and are expected to inspire future innovations toward stable interfaces in aqueous Zn-based batteries and related energy storage systems.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conception, and characterizations, and manuscript drafting: Bian, J.

Materials characterization: Yu, B.; Cao, H.; Lu, Q.

Review and editing: Bian, J.; Yu, B.; Cao, H.; Lu, Q.; Xiong, P.

Availability of data and materials

The data is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U2241257).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Ahuis, M.; Doose, S.; Vogt, D.; Michalowski, P.; Zellmer, S.; Kwade, A. Recycling of solid-state batteries. Nat. Energy. 2024, 9, 373-85.

2. Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Deep eutectic solvent additive induced inorganic SEI and an organic buffer layer synergistic protected Li anode for durable Li-CO2 batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2025, 15, 2405628.

3. Al-abbasi, M.; Zhao, Y.; He, H.; et al. Challenges and protective strategies on zinc anode toward practical aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Carbon. Neutral. 2024, 3, 108-41.

5. Luo, C.; Lei, H.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Recent development in addressing challenges and implementing strategies for manganese dioxide cathodes in aqueous zinc ion batteries. Energy. Mater. 2024, 4, 400036.

6. Li, Y.; Guan, Q.; Cheng, J.; Wang, B. Amorphous H0.82MoO3.26 cathodes based long cyclelife fiber-shaped Zn-ion battery for wearable sensors. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2022, 49, 227-35.

7. Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Guo, W.; Zha, C. Emerging strategies for the improvement of modifications in aqueous rechargeable zinc-iodine batteries: cathode, anode, separator, and electrolyte. Carbon. Neutral. 2024, 3, 918-49.

8. Guo, W.; Dun, C.; Yu, C.; et al. Mismatching integration-enabled strains and defects engineering in LDH microstructure for high-rate and long-life charge storage. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1409.

9. Lin, H.; Zeng, L.; Lin, C.; et al. Interfacial regulation via configuration screening of a disodium naphthalenedisulfonate additive enabled high-performance wide-pH Zn-based batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 1282-93.

10. Huang, S.; Zhang, P.; Lu, J.; et al. Molecularly engineered multifunctional imide derivatives for practical Zn metal full cells. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 7870-81.

11. Chen, M.; Zhang, S.; Zou, Z.; et al. Review of vanadium-based oxide cathodes as aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Rare. Metals. 2023, 42, 2868-905.

12. Han, W.; Liu, G.; Seo, W.; Lee, H.; Chu, H.; Yang, W. Nitrogen-doped chain-like carbon nanospheres with tunable interlayer distance for superior pseudocapacitance-dominated zinc- and potassium-ion storage. Carbon 2021, 184, 534-43.

13. Miao, L.; Guo, Z.; Jiao, L. Insights into the design of mildly acidic aqueous electrolytes for improved stability of Zn anode performance in zinc-ion batteries. Energy. Mater. 2023, 3, 300014.

14. Wang, K.; Baule, N.; Jin, H.; et al. Multifunctional zinc silicate coating layer for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500012.

15. Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Wan, J.; et al. Eutectic network synergy interface modification strategy to realize high-performance Zn-I2 batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2024, 14, 2402900.

16. Ballas, E.; Nimkar, A.; Bergman, G.; et al. Self-discharge in flowless Zn-Br2 batteries and its mitigation. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2024, 70, 103461.

17. Li, H.; Hao, J.; Qiao, S. Z. AI-driven electrolyte additive selection to boost aqueous Zn-ion batteries stability. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2411991.

18. Wu, C.; Sun, C.; Ren, K.; et al. 2-methyl imidazole electrolyte additive enabling ultra-stable Zn anode. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139465.

19. Xiong, P.; Lin, C.; Wei, Y.; et al. Charge-transfer complex-based artificial layers for stable and efficient Zn metal anodes. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2023, 8, 2718-27.

20. Song, B.; Lu, Q.; Wang, X.; Xiong, P. Promoted de-solvation effect and dendrite-free Zn deposition enabled by in-situ formed interphase layer for high-performance zinc-ion batteries. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500031.

21. Xiong, L.; Fu, H.; Han, W.; et al. Robust ZnS interphase for stable Zn metal anode of high-performance aqueous secondary batteries. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 1053-60.

22. Chen, A.; Zhao, C.; Guo, Z.; et al. Fast-growing multifunctional ZnMoO4 protection layer enable dendrite-free and hydrogen-suppressed Zn anode. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2022, 44, 353-9.

23. Han, W.; Xiong, L.; Wang, M.; et al. Interface engineering via in-situ electrochemical induced ZnSe for a stabilized zinc metal anode. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442, 136247.

24. Ren, Q.; Tang, X.; He, K.; et al. Long-cycling zinc metal anodes enabled by an in situ constructed ZnO coating layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2312220.

25. Wang, W.; Huang, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. Organic acid etching strategy for dendrite suppression in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2102797.

26. Tao, F.; Liu, Y.; Ren, X.; et al. Different surface modification methods and coating materials of zinc metal anode. J. Energy. Chem. 2022, 66, 397-412.

27. Pan, H.; Shao, Y.; Yan, P.; et al. Reversible aqueous zinc/manganese oxide energy storage from conversion reactions. Nat. Energy. 2016, 1, 16039.

28. Chu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, S.; Hu, Z.; Cui, G.; Luo, J. In situ built interphase with high interface energy and fast kinetics for high performance Zn metal anodes. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3609-20.

29. Cao, L.; Li, D.; Pollard, T.; et al. Fluorinated interphase enables reversible aqueous zinc battery chemistries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 902-10.

30. Zhang, S.; Hao, J.; Luo, D.; et al. Dual-function electrolyte additive for highly reversible Zn anode. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2021, 11, 2102010.

31. Cao, L.; Li, D.; Hu, E.; et al. Solvation structure design for aqueous Zn metal batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 21404-9.

32. Yan, M.; Xu, C.; Sun, Y.; Pan, H.; Li, H. Manipulating Zn anode reactions through salt anion involving hydrogen bonding network in aqueous electrolytes with PEO additive. Nano. Energy. 2021, 82, 105739.

33. Zhang, J.; Lin, C.; Zeng, L.; et al. A hydrogel electrolyte with high adaptability over a wide temperature range and mechanical stress for long-life flexible zinc-ion batteries. Small 2024, 20, e2312116.

34. Zhou, L.; Wu, C.; Yu, F.; et al. Dislocation effect boosting the electrochemical properties of prussian blue analogues for 2.6 V high-voltage aqueous zinc-based batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 47454-63.

35. Zhang, F.; Meng, Q.; Qian, J. W.; et al. Selective interface engineering with large π-conjugated molecules enables durable Zn anodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202425487.

36. Li, R.; Li, M.; Chao, Y.; et al. Hexaoxacyclooctadecane induced interfacial engineering to achieve dendrite-free Zn ion batteries. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2022, 46, 605-12.

37. Zhang, Y.; Ao, H.; Dong, Q.; et al. Electrolytes additives for Zn metal anodes: regulation mechanism and current perspectives. Rare. Metals. 2024, 43, 4162-97.

38. Zhang, Q.; Luan, J.; Fu, L.; et al. The three-dimensional dendrite-free zinc anode on a copper mesh with a zinc-oriented polyacrylamide electrolyte additive. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15841-7.

39. Wang, D.; Lv, D.; Liu, H.; et al. In situ formation of nitrogen-rich solid electrolyte interphase and simultaneous regulating solvation structures for advanced Zn metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202212839.

40. Huang, S.; Fu, H.; Kwon, H. M.; et al. Stereoisomerism of multi-functional electrolyte additives for initially anodeless aqueous zinc metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6117.

41. Guo, J.; Abbas, S. C.; Huang, H.; et al. Rational design of pyrrolic-N dominated carbon material derived from aminated lignin for Zn-ion supercapacitors. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2023, 641, 155-65.

42. Cui, F.; Hu, F.; Yu, X.; Guan, C.; Song, G.; Zhu, K. In-situ tuning the NH4+ extraction in (NH4)2V4O9 nanosheets towards high performance aqueous zinc ion batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2021, 492, 229629.

43. Han, W.; Lee, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Toward highly reversible aqueous zinc-ion batteries: nanoscale-regulated zinc nucleation via graphene quantum dots functionalized with multiple functional groups. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139090.

44. Hu, F.; Cui, Z.; Dong, Z.; et al. Zwitterionic gemini additive as interface engineers for long-life aqueous Zn/TEMPO flow batteries with enhanced areal capacity. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500078.

45. Hieu, L. T.; So, S.; Kim, I. T.; Hur, J. Zn anode with flexible β-PVDF coating for aqueous Zn-ion batteries with long cycle life. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 411, 128584.

46. Feng, H.; Zhou, W.; Chen, Z.; et al. Trace amounts of multifunctional electrolyte additives enhance cyclic stability of high-rate aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Small 2024, 20, e2407238.

47. Zhang, H.; Guo, R.; Li, S.; et al. Graphene quantum dots enable dendrite-free zinc ion battery. Nano. Energy. 2022, 92, 106752.

48. Chen, D.; Ma, X.; Xu, W.; et al. Disrupting hydrogen bond network connectivity with a double-site additive for long-life aqueous zinc metal batteries. Exploration 2025, 5, 20240007.

49. Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Xia, L.; et al. Bifunctional electrolyte addition for longer life and higher capacity of aqueous zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitors. Rare. Metals. 2024, 43, 5060-9.

50. Zhong, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Monosodium glutamate, an effective electrolyte additive to enhance cycling performance of Zn anode in aqueous battery. Nano. Energy. 2022, 98, 107220.

51. Zhao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Guo, B.; et al. Malic acid additive with a dual regulating mechanism for high-performances aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157431.

52. Zheng, X.; Han, B.; Sun, J.; et al. Polyetheramine nematic spatial effects reshape the inner/outer helmholtz planes for energetic zinc batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2420434.

53. Wang, L.; Yu, H.; Chen, D.; et al. Steric hindrance and orientation polarization by a zwitterionic additive to stabilize zinc metal anodes. Carbon. Neutral. 2024, 3, 996-1008.

54. Song, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; et al. A widely used nonionic surfactant with desired functional groups as aqueous electrolyte additives for stabilizing Zn anode. Rare. Metals. 2024, 43, 3692-701.

55. Zhang, S. J.; Hao, J.; Wu, H.; Chen, Q.; Ye, C.; Qiao, S. Z. Protein interfacial gelation toward shuttle-free and dendrite-free Zn-iodine batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2404011.

56. Wu, K.; Wang, Y.; Wan, Y.; et al. Nitrogen and oxygen Co-doped graphene quantum dots as a trace amphipathic additive for dendrite-free Zn anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2412027.

57. Yang, Z.; Lai, F.; Mao, Q.; et al. Reversing zincophobic/hydrophilic nature of metal-N-C via metal-coordination interaction for dendrite-free Zn anode with high depth-of-discharge. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2311637.

58. Deng, S.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. Zwitterion-separated ion pair dominated additive-electrolyte structure for ultra-stable aqueous zinc ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Materials. 2024, 34, 2408546.

59. Huang, C.; Liu, S.; Feng, J.; et al. Optimizing engineering of rechargeable aqueous zinc ion batteries to enhance the zinc ions storage properties of cathode material. J. Power. Sources. 2021, 490, 229528.

60. Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Bi-functional green additive anchoring interface enables stable zinc metal anodes for aqueous zinc-ions batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2410855.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].