Optimizing diffusion kinetics of two-dimensional structures via nano-assembling towards rapid oxygen reduction electrocatalysis

Abstract

In the realm of metal-air batteries (MABs) and fuel cells (FC), managing the thickly catalytic layer of metal-nitrogen-carbon (M-N-C) catalysts is pivotal, where the design of mass transport pathways in meso- and macro-scale is essential around the active metal sites. Such arrangements are crucial to achieving adequate three-phase boundaries and timely kinetic responses during oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). Yet, when it comes to materials with low-dimensional morphologies, such as nanolayers and nanosheets, the high aspect ratios render new challenges to structure maintenance during the pore formation, usually involving templating or etching, and against the pyrolysis collapse. Herein, we have developed an in-situ nano-assembling methodology to design hierarchical porosity in M-N-C catalysts pyrolytically derived from 2D materials. By controlling the solvothermal synthesis, the 2D nonporous precursors, fusiform ZIF-L nanolayers, are taken as a particular experimental model; they can scale down into secondary monomers and restack meso- and macro-porously. After pyrolysis, the derived Fe-N-C catalysts well inherit the hierarchical morphology and thus showcase calcined micro-pores along with a spectrum of meso- and macro-pores. Advanced characterization techniques such as the spherical aberration correction electron microscopy and X-ray absorption spectrum allow us to pinpoint atomically dispersed FeN4 motifs as the primary active sites. Notably, their upgraded accessibility exhibits a direct correlation to the performance parameters in half-cells and prototype zinc-air batteries (ZABs). This investigation heralds new pathways for the optimization of low-dimensional nanocatalysts, aiming to exploit their activity within catalytic layers to the fullest.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) electrocatalysis is crucial in metal-air batteries (MABs), fuel cells (FC), and various electrochemical synthesis and purification of organic chemicals[1-5], thus playing a significant role in optimizing the global carbon cycle. Currently, commercial platinum-based catalysts dominate ORR, accelerating the sluggish multiple electron transfer process and adjusting product selectivity. However, the heavy reliance on platinum, coupled with its rarity and uneven distribution, has raised growing concerns about the further industrialization and innovation of next-generation energy devices and techniques. Therefore, the search for high-performance platinum-group-metal (PGM)-free alternatives is urgent to ensure sustainable chemistry and energy security.

Atomically dispersed non-noble metal embedded in N-doped graphitic carbon matrices, referred to as metal-nitrogen-carbons (M-N-Cs), is considered a promising catalyst due to their low cost and atomic economy. This makes it possible to improve overall performance by facilely increasing the active species loading on electrodes to compensate for the inferior mass activity than PGM catalysts. Nevertheless, in terms of ORR, the stacking catalytic layer thickness, currently exceeding 150 nm[6], makes the access and long-term transport between oxygen species and the active sites a dominant factor in the activity of electrode assemblies[7], thereby raising urgent structural optimization issues for M-N-C catalysts.

In recent years, the hierarchical porosity has been extensively studied to enhance the diffusion kinetics of M-N-C ORR catalysts on electrodes[8-13]. Our group also pays increasing interest in upgrading advanced catalytic materials through pore engineering methods. In previous studies, we constructed efficient FC and MAB catalysts with optimal mass transfer channels using templates[14,15] or molten metal etching strategies[16]. As research continues, the removal of templates and chemical etching processes show their shortcomings. These methods are not only tedious but also detrimental to the pre-set hierarchical structure and graphitization of the products, resulting in the degradation of high-speed mass and electron transport paths, respectively, as well as durability. Especially, materials with low-dimensional morphology, which are significant in specific electrochemical applications owing to their unique aspect ratios, however, are more sensitive to damage during pyrolysis and the traditionally stepwise pore formation involving templating embedding or etching, thus presenting practical challenges in their structural engineering.

Recently, we reported a post-synthesis strategy employing extra, yet mild steps to construct mass transfer pathways through controllable stacking of preformed catalyst particle monomers. This method has taken the catalyst’s conductivity and stability into account by avoiding excessive graphitic defects[17]. In our present work, an upgraded and facile strategy is performed to overcome the aforementioned difficulties of pore formation on 2D materials. It is achieved through a one-step in-situ synthesis of hierarchical 2D metal-organic framework (MOF) precursors by controllable crystallization in an optimized solvothermal system, followed by pyrolysis to derive atomically dispersed metal active sites with ideal, electrochemically functional porosity.

ZIF-L (2D zeolitic imidazolate frameworks with a leaf-like morphology), a widely used 2D MOF precursor in catalytic materials with reportedly nonporous structure[18-22], is chosen as the experimental model. Subsequently, developed Fe-N-C catalysts are successfully prepared. The structure and performance optimization is clearly revealed, such as the maintained hierarchically porous morphology, the dispersed

EXPERIMENTAL

Synthesis of Fe-N-C NA

First, 400.0 mg dimethylimidazole was dissolved in 47 mL deionized water. Then, 3 mL deionized water containing 400.0 mg Zn(NO3)2·6H2O and 8 mg Fe(NO3)3·9H2O was added dropwise to the above solution and stirred at room temperature for 12 h. The obtained liquid was centrifugally washed three times, and the precipitate was freeze-dried to obtain the ZIF-L nano-assembly (NA) precursor. ZIF-L NA was annealed under the Ar flow at 950 °C for 2 h to harvest the black powder Fe-N-C NA. The synthesis of Fe-N-C bulk is the same as Fe-N-C NA except for the different amount of dimethylimidazole (656.8 mg in 20 mL deionized water), Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (148.7 mg in 10 mL deionized water), and Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (8 mg in 10 mL deionized water) and these three solutions were fast mixed.

Electrochemical quantification of the accessible FeN4 sites

The mass site density (MSD) of the accessible FeN4 sites is measured according to the references[23,24]. In brief, the cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans are performed in N2 saturated acetate buffer (pH = 5.2) before, during and after NaNO2 adsorption in the range containing the potential region of nitrite stripping. The MSD is calculated by Equation (1)[23,24]:

where Qstrip is the nitrosyl reduction charge (2.811 × 10-3 C) proportioned to the catalyst mass loading on the working electrode (0.185 mg); nstrip is the transferred electron number per nitrite reduction; F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol-1); NA is the Avogadro constant (6.022 × 1023). It should be noted that the CV plots used to calculate the Qstrip are harvested during the twice poisoning process according to the ref[24].

Electrochemical ORR tests

All half-cell electrochemical measurements were conducted on a CHI 760E workstation (Shanghai Chenhua Co.). A standard three-electrode system includes the glassy carbon rotating disk electrode (RDE) covered with the catalyst as the working electrode (diameter 5 mm, surface area 0.196 cm2), a graphite rod as the counter electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode. All the potentials in this study have been converted to values regarding the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) according to Equation (2)[25]:

First, 2 mg catalyst was mixed with 485 μL isopropanol and 15 μL 5.0 wt% perfluorinated sulfonate polymer solution (Nafion) and ultrasound for 30 min to obtain a uniform catalyst ink. Then, 40 μL ink was spread evenly on the working electrode and dried naturally for ORR tests. The working electrode for MSD tests was prepared with the same method except for the 0.185 mg loading amount.

The electrocatalytic ORR process was tested in a 0.1 M KOH electrolyte with CV and linear sweep voltammetry (LSV). Then, the K-L plots were derived from the LSV and the electron transfer number was calculated as per the ref[26]. CV scans were performed with a sweep speed of 50 mV·s-1 and a sensitivity of 10-3. The LSV scans were conducted at a sweep speed of 5 mV·s-1 and a sensitivity of 10-3 at 400, 625, 900, 1,225, 1,600, and 2,025 rpm. In nitrogen-saturated electrolytes, the LSV test was static. The chronoamperometry (i - t) curve was tested at 0.75 V vs. RHE at 900 rpm. For the measurement of hydrogen peroxide yield and electron transfer number, a rotating ring disk electrode (RRDE) was used and LSV was performed at

Electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) was calculated by CV at a non-faradaic potential range without polarization current. The double-layer capacitance C (F·g-1) was calculated based on the relationship between the current (I) and the catalyst mass (m) deposited on the electrode and the given scan rate (v) according to Equation (3)[28]:

ZAB tests

The Zn-air battery measurements were performed with homemade Zn-air battery equipment. Fe-N-C NA and Pt/C (20 wt%) were loaded on carbon fiber paper (9 cm2) with a gas-diffusion layer, which were taken as the air cathode to fabricate the catalyst layer with a catalyst loading of 1.1 mg·cm-2. A Zn plate was polished smoothly as the anode. The 6 M KOH solution was used as the electrolyte. Additionally, the detailed characterization and reagents used for this work are listed in the Supplementary Materials and Characterization.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structural design and analysis of pore engineering strategy via NA

The NA pore engineering strategy is illustrated in Figure 1A. Specifically, an elaborated solvothermal synthesis by feed-controlled nucleation and growth process (detailed in EXPERIMENTAL section) is employed to prepare ZIF-L microcrystalline nanolayers and self-assemble into ZIF-L NA precursors [Figure 1B] compared with the traditional synthesis method for ZIF-L bulks[29,30]. After pyrolysis, not only the fluffy structure is maintained but also channels in nano- and micro-scale form as new mass transfer pathways

Figure 1. Comparison of morphology and porosity of precursors and catalysts. (A) synthetic scheme; SEM images of (B) ZIF-L NA and (C) Fe-N-C NA; HAADF-STEM and EDS mapping images of (D) ZIF-L NA and (E) Fe-N-C NA; TEM and EDS mapping images of (F) ZIF-L bulk and (G) Fe-N-C bulk. SEM: Scanning electron microscope; NA: nano-assembly; HAADF-STEM: high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy; EDS: energy dispersive spectrometer; TEM: transmission electron microscopy.

The iron active species in catalysts are further investigated on the atomic scale [Figure 2]. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images in different resolutions [Figure 2A and B] reveal that only graphitic carbon fringes and corresponding diffraction rings [Figure 2B inset] are on the pore-rich edges of Fe-N-C NA. With spherical-aberration-corrected high-resolution high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (AC-HR-HAADF-STEM), dispersed spots at about the atom size are observed, which reveals abundant Fe SAs in Fe-N-C NA, implying high activity as references reported [Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure 3][31-35]. The microenvironment of Fe SAs is analyzed with X-ray absorption spectra [Figure 2D-F, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2]. The X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) of Fe-K edge

Figure 2. Analysis for the active sites in Fe-N-C NA. (A and B) HR-TEM images in low and high magnification, respectively. (B) the selected area electron diffraction. The d-spacings of the diffraction rings are 0.208 and 0.128 nm corresponding to graphite {101} and {110}, respectively; (C) AC-HR-HAADF-STEM image of Fe SA sites; (D) XANES of E space plots and (E) EXAFS of R space plots for Fe-K edge of Fe-N-C NA and Fe foil, FeO and Fe2O3 references; (F) R space fitting for Fe-K edge of Fe-N-C NA. NA: Nano-assembly; HR-TEM: high-resolution transmission electron microscopy; AC-HR-HAADF-STEM: aberration-corrected high-resolution high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy; SA: single atom; XANES: X-ray absorption near edge structure; EXAFS: extended X-ray absorption fine structure.

These characteristics above manifest the positive effects of our NA pore engineering strategy on building porosity, maintaining morphology and dispersing active species.

The catalyst and active site structures are also confirmed by comprehensive physical characteristics [Figure 3]. The porosity of the precursors and catalysts is investigated by the N2 adsorption and desorption isotherms [Figure 3A]. The negligible adsorption amounts at low relative pressure regions for the precursors correspond to the nonporous feature of ZIF-L[38]. It is worth noting that the obvious jump without adsorption restriction at the high relative pressure region above 0.9 (noted with the grey arrow “a”) emerges, which belongs to the H3- or H4-type hysteresis loops of the slits or stack pores in flakes[39]. These characteristics strongly confirm that the NA pore engineering strategy creates newly large (meso- or macro-) channels in NAs through the monomers stack. For the catalysts, the pyrolytic micropores are formed, which shows similar Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas of 1,056.99 and 982.79 m2·g-1 for Fe-N-C NA and Fe-N-C bulk, respectively. The difference is that the hysteresis loop (noted with the grey arrow “b”) and the jump at high pressure regions emerge on the Fe-N-C NA curve, implying the existence of meso- and macro-pores. In virtue of the pore size distribution [Supplementary Figure 4], a noticeably increasing ratio of pore volume is observed for ZIF-L NA (> 2 nm) and Fe-N-C NA (> 20 nm) than the bulk counterparts.

Figure 3. Comprehensive physical characteristics for structural analysis. (A) the N2 adsorption/desorption isothermals of ZIF-L NA, ZIF-L bulk, Fe-N-C NA, and Fe-N-C bulk; (B) PXRD patterns of Fe-N-Cs; (C and D) Raman spectra of Fe-N-C NA and Fe-N-C bulk, respectively; (E and F) XPS spectra for N 1s orbits of Fe-N-C NA and Fe-N-C bulk, respectively. NA: Nano-assembly; PXRD: powder X-ray diffraction; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) of ZIF-L NA reveals consistent peak positions as simulation and similar intensities with that of ZIF-L bulk [Supplementary Figure 5], indicating that the synthesis of our strategy can successfully maintain a good degree of crystallization of ZIF-L during introducing porosity. The PXRD pattern of Fe-N-C NA [Figure 3B] only shows broad peaks of graphitic carbon. The lack of sharp peaks of crystalline metal species indicates that there are no severely aggregated iron species. The Raman spectra manifest a similar ID:IG value in the two catalysts but a higher area ratio of the D1 against G peak (AD1:AG) in Fe-N-C NA [Figure 3C and D]. This indicates that the engineered catalysts can maintain not only a comparable graphitization degree but also more graphitic defects which have been proven to be positive to the oxygen reduction activity[40,41]. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [Figure 3E and F] analysis of N 1s orbits reveals abundant N species in the two catalysts. The M-N peak at about 398.6 eV in the Fe-N-C NA curve corresponds to the Fe-N coordination in Fe SAs[14], which is consistent with the previous EXAFS analysis. With these comprehensive characteristics, the positive effects of our NA pore engineering strategy for catalyst and active site structure can be concluded as (a) introducing engineered meso- and macro-channels into the pyrolytic microporous 2D carbon materials; (b) coupling with abundant active motifs of distorted FeN4 SA sites and graphitic defects; and meanwhile (c) maintaining the intact morphology and comparable graphitization degree for supporting the electrochemical mass and charge transfer and stability during ORR.

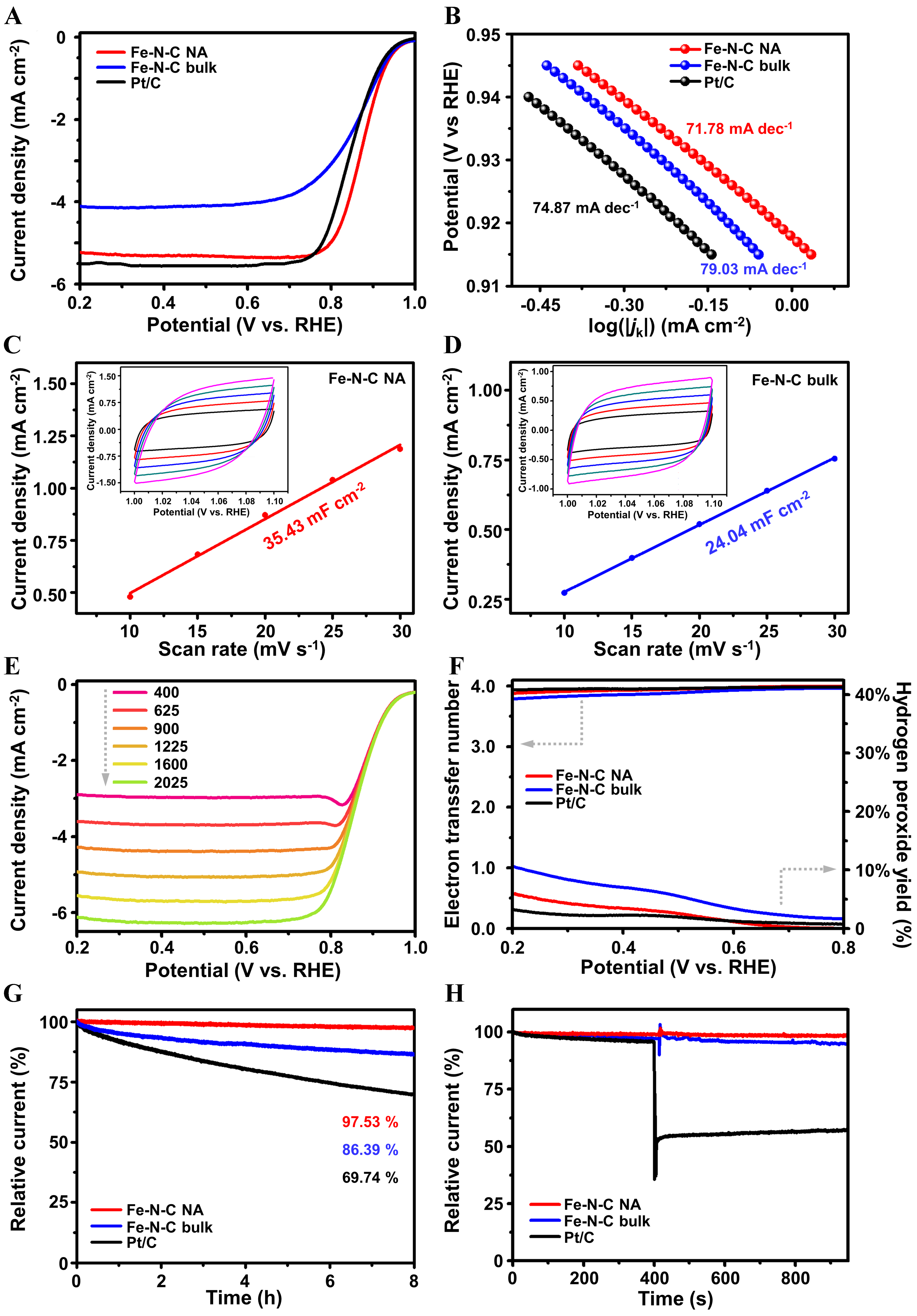

Correlations between hierarchical structure and ORR performance

We further verify the possible structure-based benefits in the electrocatalytic oxygen reduction process

Figure 4. Electrochemical oxygen reduction performance. (A) LSV curves of Fe-N-C NA, Fe-N-C bulk and Pt/C at 1,600 rpm and O2 saturated electrolyte; (B) the corresponding Tafel plots of Fe-N-C NA, Fe-N-C bulk and Pt/C derived from Jk; (C and D) the relationship between current density and scanning rate of (C) Fe-N-C NA and (D) Fe-N-C bulk, respectively, derived from the CV curves at N2 saturated electrolytes of Fe-N-C NA (inset C) and Fe-N-C bulk (inset D) under 10 (black), 15 (red), 20 (blue), 25 (cyan), 30 (magenta) mV·s-1; (E) ORR polarization curves of Fe-N-C NA at different rotation speeds; (F) average electron transfer number and H2O2 yield curves of Fe-N-C NA, Fe-N-C bulk and Pt/C; (G) i - t plots under 0.75 V vs. RHE and 900 rpm of Fe-N-C NA, Fe-N-C bulk and Pt/C; and (H) i - t plots of Fe-N-C NA, Fe-N-C bulk, and Pt/C before and after methanol poisoning. LSV: Linear sweep voltammetry; NA: nano-assembly; CV: cyclic voltammetry; ORR: oxygen reduction reaction; RHE: reversible hydrogen electrode.

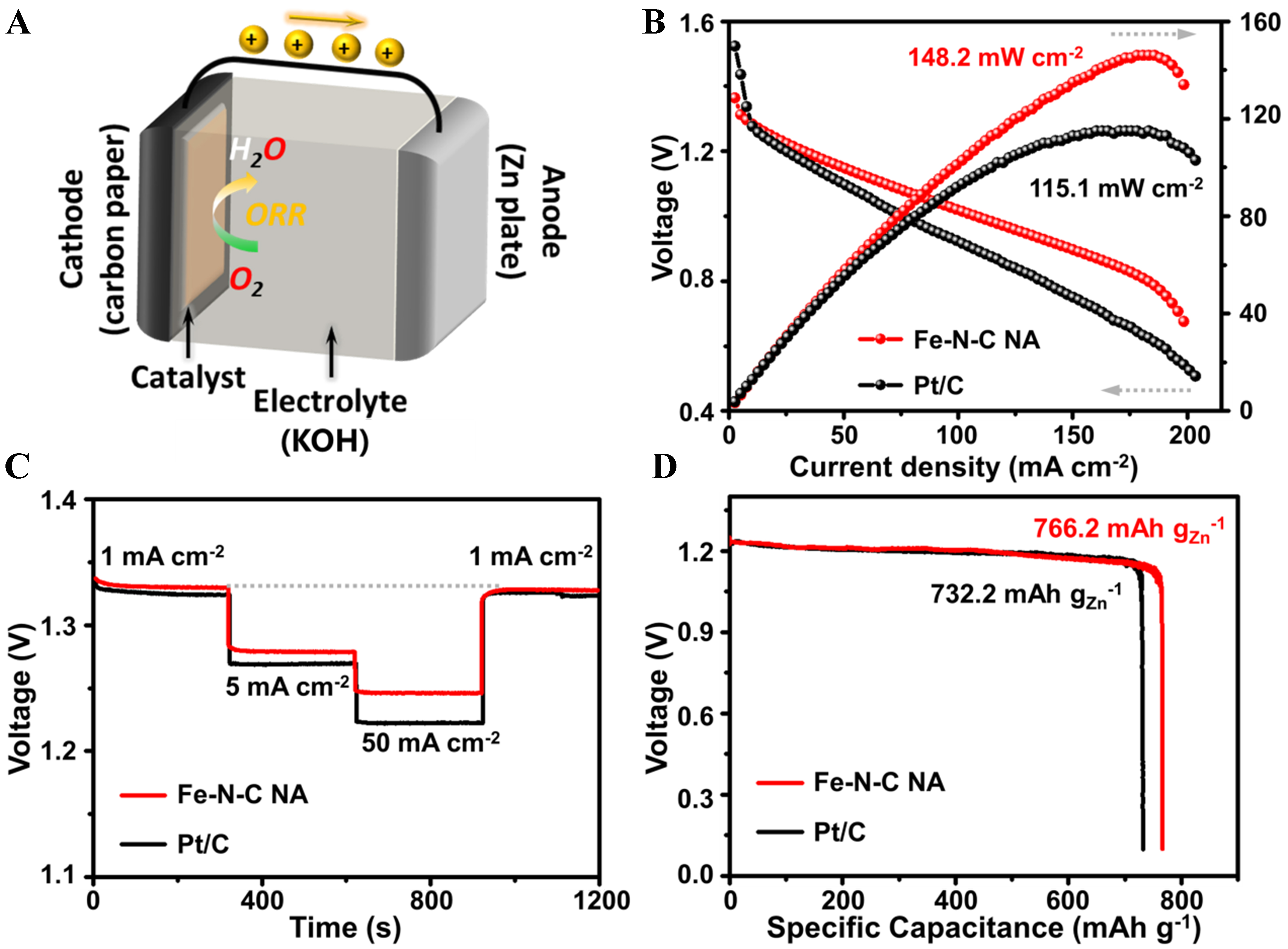

Enhanced performance on ZAB applications

The ZAB is a significant application of ORR towards the next-generation energy technique and device[44,45]. Thus, the promising ORR performance of Fe-N-C NA is further verified as the air-electrode catalyst [Figure 5] in a prototype ZAB according to the previous work[16], which is illustrated in Figure 5A. The open circuit voltage is first confirmed to be 1.45 V [Supplementary Figure 9], which is close to the theoretical value of the reaction. The power densities [Figure 5B] are further measured and that of Fe-N-C NA reaches

Figure 5. ZAB performance of Fe-N-C NA and the commercial Pt/C benchmark. (A) scheme of the prototype ZAB with Fe-N-C NA or Pt/C as cathodes; (B) discharge polarization and power density curves; (C) galvanostatic discharge curves at various current densities; (D) the discharge curves at a constant current density of 10 mA·cm-2. ZAB: Zinc-air battery; NA: nano-assembly.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we have successfully pioneered a NA pore engineering strategy to instill electrochemically functional porosity within two-dimensional materials. This approach has been evidenced by the concurrent optimization of porosity and structural morphology while maintaining the degree of graphitization. Furthermore, it facilitates the isolation of single atomic active sites amidst plentiful graphitic defects. Our ZIF-L paradigm catalysts have notably exhibited superior ORR performance, underlining their potential utility in ZABs. This research lays a solid foundation for future endeavors to harness non-noble single-atom sites more effectively in two-dimensional frameworks, through the lens of ingenious pore engineering techniques.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

Allocation of beamtime at 1W1B beamline, BSRF, Beijing, China, is gratefully acknowledged.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, Z.

Synthesis, characterization, and measurements: Wen, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.

Data analysis and original draft: Yuan, Y.; Wang, H.

Review and writing finalization: Yuan, Y.; Bai, Z.

Resources: Zhang, Q.; Bai, Z.

Availability of data and materials

All other relevant data supporting the findings of this study (the detailed materials and methods; SEM and TEM images of ZIF-L bulk and Fe-N-C bulk; AC-HR-HAADF-STEM images of Fe-N-C NA; pore size distribution of the precursors and catalysts; PXRD pattern of the ZIF-Ls; CV curves of the catalysts during ORR measurements; CV curves before, during, and after the nitrite poisoning; the K-L plots; the OCP of assembled ZABs; XPS and TEM results of the post morphology analysis of Fe-N-C NA; EXAFS fitting factors; XANES adsorption edge analysis) are available in Supplementary Materials.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52271176 and 52301270), the 111 Project (Grant No. D17007), Henan Center for Outstanding Overseas Scientists (Grant No. GZS2022017) and Henan Province Key Research and Development Project (Grant No. 231111520500).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Zhao, Y.; Adiyeri, S. D. P.; Huang, C.; et al. Oxygen evolution/reduction reaction catalysts: from in situ monitoring and reaction mechanisms to rational design. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6257-358.

2. Yan, L.; Li, P.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Atomically precise electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Chem 2023, 9, 280-342.

3. Wang, S.; Chu, Y.; Lan, C.; Liu, C.; Ge, J.; Xing, W. Metal–nitrogen–carbon catalysts towards acidic ORR in PEMFC: fundamentals, durability challenges, and improvement strategies. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 15.

4. Niu, Y.; Gong, S.; Liu, X.; et al. Engineering iron-group bimetallic nanotubes as efficient bifunctional oxygen electrocatalysts for flexible Zn–air batteries. eScience 2022, 2, 546-56.

5. Xu, C.; Niu, Y.; Ka-man, A. V.; et al. Recent progress of self-supported air electrodes for flexible Zn-air batteries. J. Energy. Chem. 2024, 89, 110-36.

6. Gottesfeld, S.; Dekel, D. R.; Page, M.; et al. Anion exchange membrane fuel cells: current status and remaining challenges. J. Power. Source. 2018, 375, 170-84.

7. Lee, S. H.; Kim, J.; Chung, D. Y.; et al. Design principle of Fe-N-C electrocatalysts: how to optimize multimodal porous structures? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2035-45.

8. Lu, X.; Yang, P.; Wan, Y.; et al. Active site engineering toward atomically dispersed M−N−C catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2023, 495, 215400.

9. Xu, C.; Zuo, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. Hierarchically structured Mo1–2C/Co-encased carbon nanotubes with multi-component synergy as bifunctional oxygen electrocatalyst for rechargeable Zn-air battery. J. Power. Source. 2024, 595, 234063.

10. Zhao, C. X.; Li, B. Q.; Liu, J. N.; Zhang, Q. Intrinsic electrocatalytic activity regulation of M-N-C single-atom catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 4448-63.

11. Song, W.; Xiao, C.; Ding, J.; et al. Review of carbon support coordination environments for single metal atom electrocatalysts (SACS). Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2301477.

12. Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Hierarchical porous yolk-shell Co-N-C nanocatalysts encaged ingraphene nanopockets for high-performance Zn-air battery. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 8893-901.

13. Luo, E.; Chu, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Pyrolyzed M–Nx catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction: progress and prospects. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 2158-85.

14. Fu, X.; Gao, R.; Jiang, G.; et al. Evolution of atomic-scale dispersion of FeNx in hierarchically porous 3D air electrode to boost the interfacial electrocatalysis of oxygen reduction in PEMFC. Nano. Energy. 2021, 83, 105734.

15. Fu, X.; Jiang, G.; Wen, G.; et al. Densely accessible Fe-Nx active sites decorated mesoporous-carbon-spheres for oxygen reduction towards high performance aluminum-air flow batteries. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2021, 293, 120176.

16. Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; et al. Optimizing oxygen redox kinetics of M-N-C electrocatalysts via an in-situ self-sacrifice template etching strategy. Chinese. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107807.

17. Zhang, Q.; Liu, P.; Fu, X.; et al. Hierarchical architecture of well-aligned nanotubes supported bimetallic catalysis for efficient oxygen redox. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2112805.

18. Huo, M.; Sun, T.; Wang, Y.; et al. A heteroepitaxially grown two-dimensional metal–organic framework and its derivative for the electrocatalytic oxygen reduction reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022, 10, 10408-16.

19. Wu, S.; Liu, H.; Lei, G.; et al. Single-atomic iron-nitrogen 2D MOF-originated hierarchically porous carbon catalysts for enhanced oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 441, 135849.

20. Li, C.; Yuan, M.; Liu, Y.; et al. Graphite-N modified single Fe atom sites embedded in hollow leaf-like nanosheets as air electrodes for liquid and flexible solid-state Zn-air batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 146988.

21. Lee, S.; Oh, S.; Oh, M. Atypical hybrid metal-organic frameworks (MOFs): a combinative process for MOF-on-MOF growth, etching, and structure transformation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 1327-33.

22. Ma, F. X.; Liu, Z. Q.; Zhang, G.; et al. Isolating Fe atoms in N-doped carbon hollow nanorods through a ZIF-phase-transition strategy for efficient oxygen reduction. Small 2022, 18, e2205033.

23. Malko, D.; Kucernak, A.; Lopes, T. In situ electrochemical quantification of active sites in Fe-N/C non-precious metal catalysts. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13285.

24. Gong, M.; Mehmood, A.; Ali, B.; Nam, K. W.; Kucernak, A. Oxygen reduction reaction activity in non-precious single-atom (M-N/C) catalysts-contribution of metal and carbon/nitrogen framework-based sites. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 6661-74.

25. Jerkiewicz, G. Standard and reversible hydrogen electrodes: theory, design, operation, and applications. ACS. Catal. 2020, 10, 8409-17.

26. Jahan, M.; Bao, Q.; Loh, K. P. Electrocatalytically active graphene-porphyrin MOF composite for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6707-13.

27. Wang, J.; Hu, C.; Wang, L.; et al. Suppressing thermal migration by fine-tuned metal-support interaction of iron single-atom catalyst for efficient ORR. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2304277.

28. Wei, C.; Sun, S.; Mandler, D.; Wang, X.; Qiao, S. Z.; Xu, Z. J. Approaches for measuring the surface areas of metal oxide electrocatalysts for determining their intrinsic electrocatalytic activity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2518-34.

29. Pérez-miana, M.; Reséndiz-ordóñez, J. U.; Coronas, J. Solventless synthesis of ZIF-L and ZIF-8 with hydraulic press and high temperature. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2021, 328, 111487.

30. Bai, W.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Fu, Y. Transformation of ZIF-67 nanocubes to ZIF-L nanoframes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 79-83.

31. Liu, K.; Fu, J.; Lin, Y.; et al. Insights into the activity of single-atom Fe-N-C catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2075.

32. Chen, G.; An, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Highly accessible and dense surface single metal FeN4 active sites for promoting the oxygen reduction reaction. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2619-28.

33. Wei, Y. S.; Sun, L.; Wang, M.; et al. Fabricating dual-atom iron catalysts for efficient oxygen evolution reaction: a heteroatom modulator approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 16013-22.

34. Zeng, Y.; Li, C.; Li, B.; et al. Tuning the thermal activation atmosphere breaks the activity–stability trade-off of Fe–N–C oxygen reduction fuel cell catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 1215-27.

35. Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, L.; et al. Facet strain strategy of atomically dispersed Fe–N–C catalyst for efficient oxygen electrocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2206081.

36. Yang, H. B.; Hung, S.; Liu, S.; et al. Atomically dispersed Ni(I) as the active site for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Nat. Energy. 2018, 3, 140-7.

37. Jia, Q.; Ramaswamy, N.; Hafiz, H.; et al. Experimental observation of redox-induced Fe-N switching behavior as a determinant role for oxygen reduction activity. ACS. Nano. 2015, 9, 12496-505.

38. Khan, I. U.; Othman, M. H. D.; Ismail, A.; et al. Structural transition from two-dimensional ZIF-L to three-dimensional ZIF-8 nanoparticles in aqueous room temperature synthesis with improved CO2 adsorption. Mater. Charact. 2018, 136, 407-16.

39. Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure. Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051-69.

40. Tian, H.; Song, A.; Zhang, P.; et al. High durability of Fe-N-C single-atom catalysts with carbon vacancies toward the oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline media. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2210714.

41. Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, G.; et al. Ordered mesoporous Fe2Nx electrocatalysts with regulated nitrogen vacancy for oxygen reduction reaction and Zn-air battery. Nano. Energy. 2023, 115, 108672.

42. Luo, M.; Guo, S. Multimetallic electrocatalyst stabilized by atomic ordering. Joule 2019, 3, 9-10.

43. Ma, Q.; Jin, H.; Zhu, J.; et al. Stabilizing Fe-N-C catalysts as model for oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2102209.

44. Gao, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Design principles and mechanistic understandings of non-noble-metal bifunctional electrocatalysts for zinc-air batteries. Nanomicro. Lett. 2024, 16, 162.

45. Karthikeyan, S.; Sidra, S.; Ramakrishnan, S.; et al. Heterostructured NiO/IrO2 synergistic pair as durable trifunctional electrocatalysts towards water splitting and rechargeable zinc-air batteries: an experimental and theoretical study. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2024, 355, 124196.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].