Spatial distance effect of bimetallic active sites for selective hydrogenation

Abstract

The primary challenge in hydrogenation reactions is the trade-off between selectivity and activity. Many factors including the nanoparticle geometry, chemical composition, metal-support interaction, and electronic interaction can significantly influence the catalytic properties of metal active sites. A novel strategy involving bimetallic active sites with different distances (spatially intimate and spatially isolated) has shown remarkable enhancements in both activity and selectivity for a wide range of selective hydrogenation. Advances in synthesis methodologies and characterization tools allow correlation at molecular/atom levels. In this review, the electronic and geometric structures will be discussed on bimetallic active sites with tightly intimated and spatially separated structures. Meanwhile, we will discuss in detail the construction methods, synergistic effects, and hydrogenation mechanisms of bimetallic active sites. Finally, this perspective illustrates the developments and challenges associated with bimetallic active sites in hydrogenation and provides valuable insights through successful cases to guide the design of highly efficient hydrogenation catalysts.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Catalytic hydrogenation is a central theme in modern industry and scientific research, accounting for approximately 25% of chemical transformations involving at least one hydrogenation step[1-8]. Selective hydrogenation of specific functional groups while preserving other reducible functional groups has extensive applications, particularly in petrochemicals, coal chemicals, and environmental chemical industries[9-15]. Furthermore, selective hydrogenation plays a crucial role in enhancing purity and quality of products. For instance, the selective hydrogenation of acetylene represents an effective method for eliminating impurities and purifying acetylene[16-18]. Therefore, it is highly desirable to achieve highly efficient selective hydrogenation through the innovative designs of heterogeneous catalysts[1,19,20].

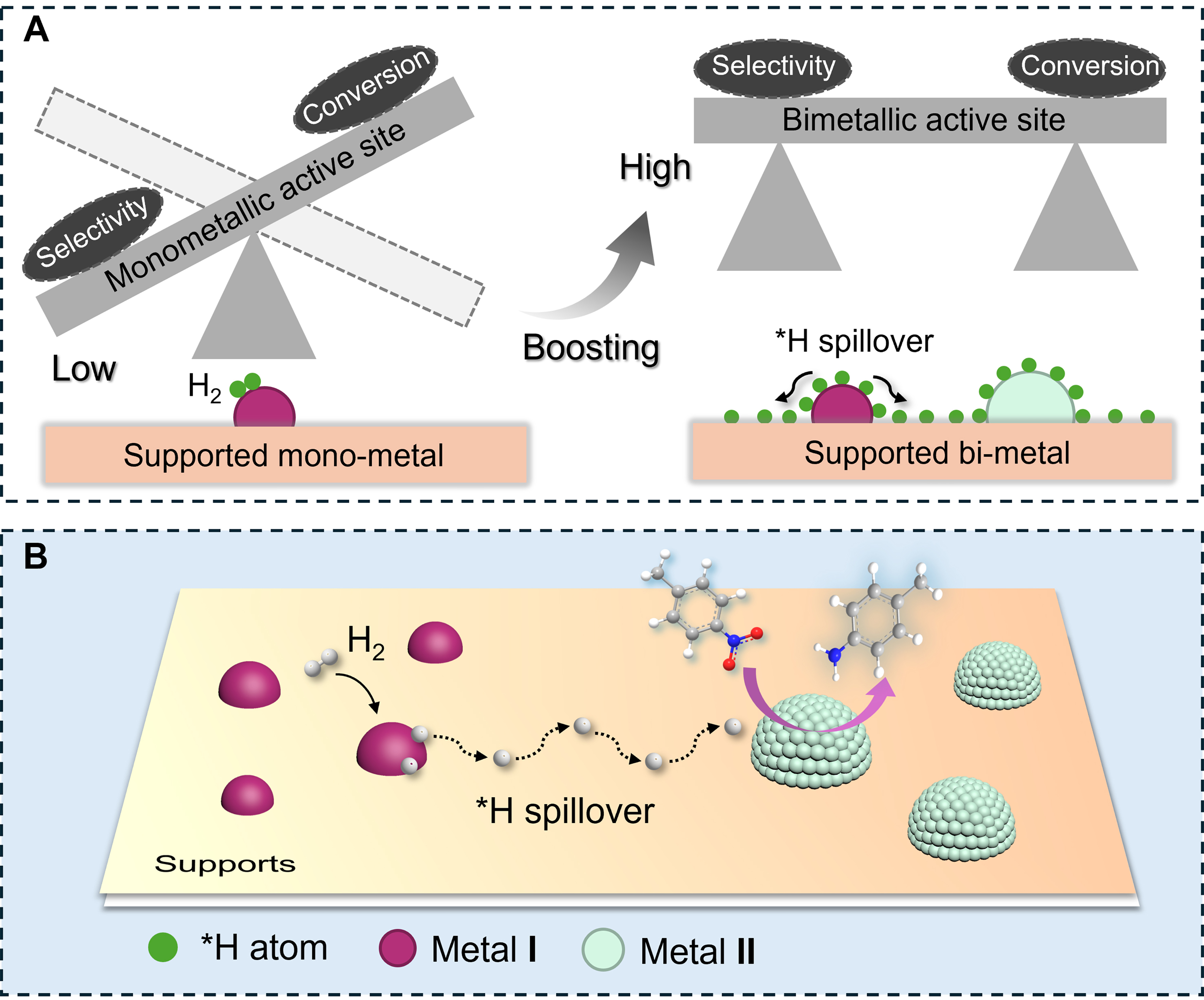

Currently, the predominant application in the industry involves supported catalysts that primarily utilize noble metals as primary active components[5,21-26]. Extensive efforts have been devoted to developing supported monometallic catalysts. However, fully meeting the demands of industrial production remains challenging. The primary obstacle is the existence of a linear scaling relationship among the adsorption energies of various reactants/intermediates[27-30], leading to a broad trade-off between activity and selectivity [Scheme 1A]. The metal-support interfaces have been identified as alternative sites to weaken the trade-off relationship[12,31-34]. However, these interfaces frequently undergo reconfiguration under reduction conditions, posing challenges in maintaining their catalytic performance[35-38].

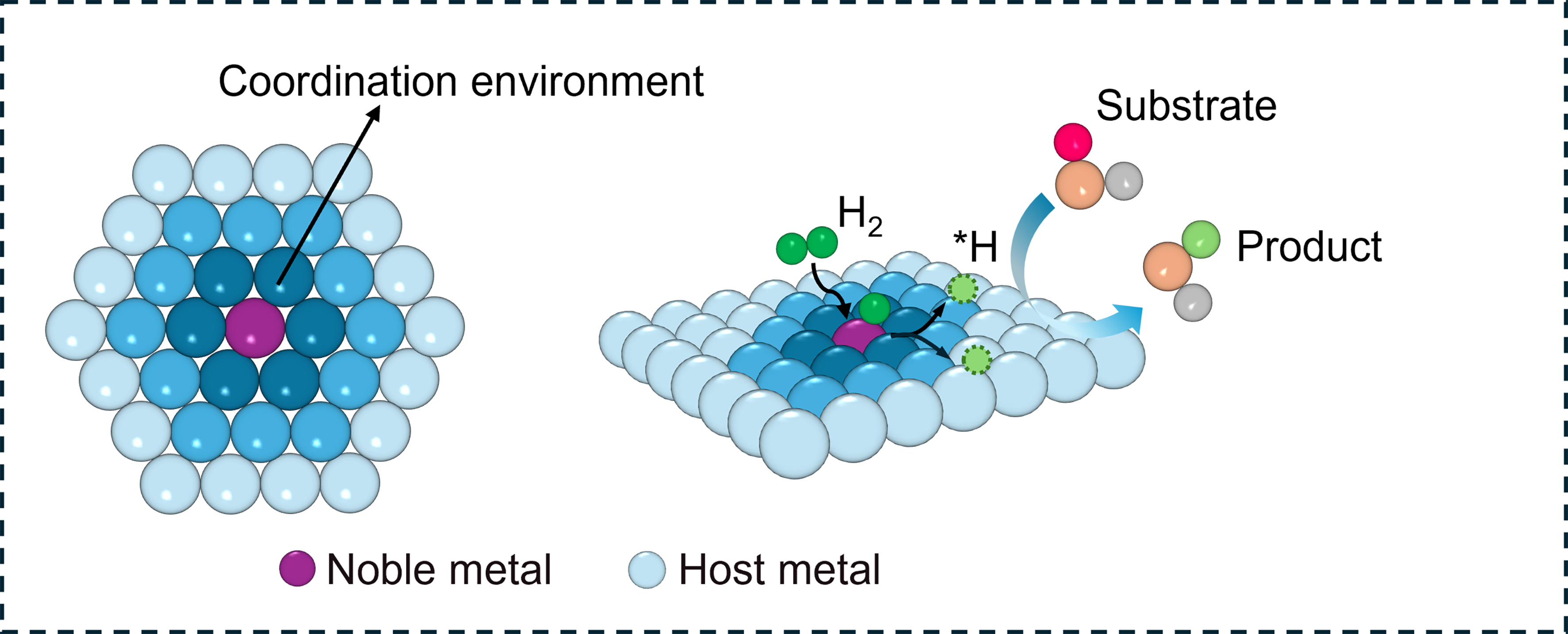

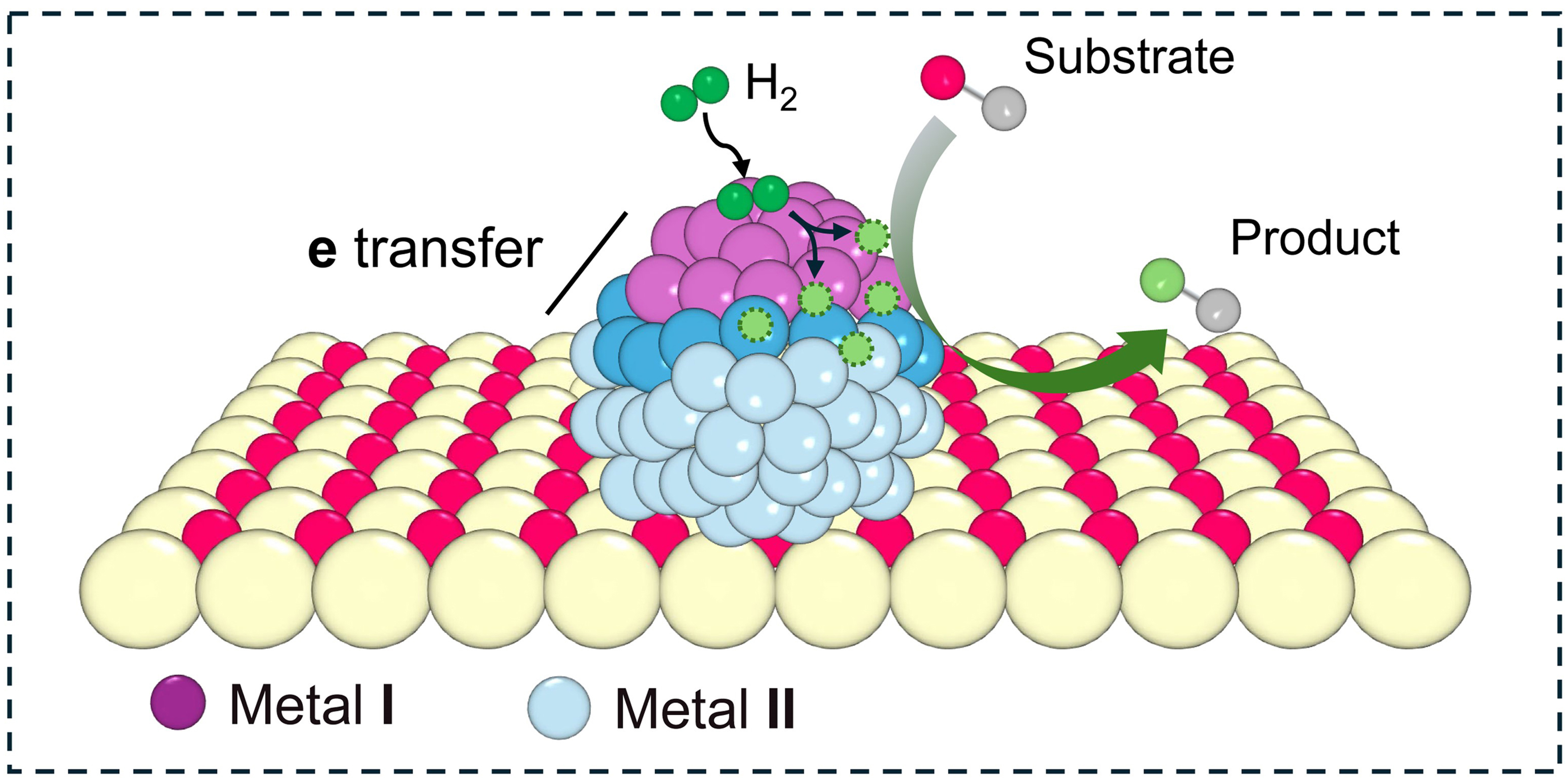

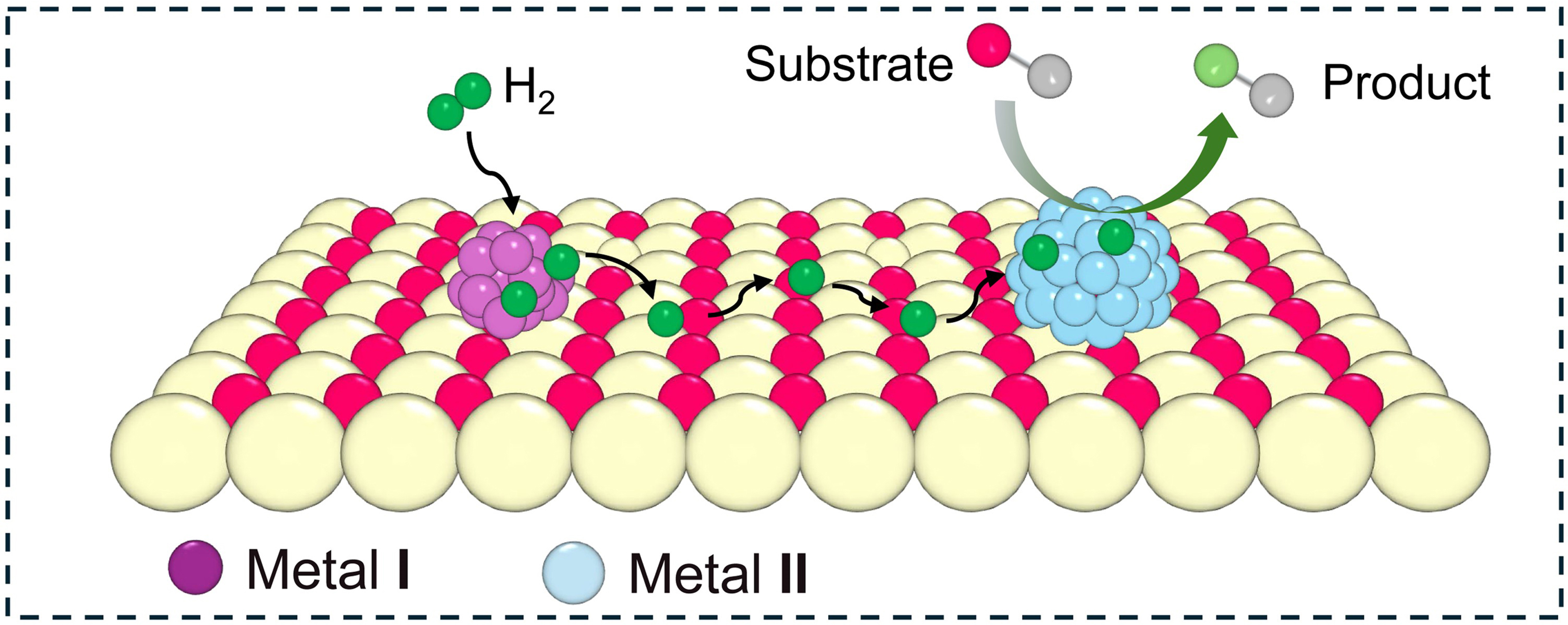

Scheme 1. (A) The “seesaw effect” of selectivity and activity for selective hydrogenation over monometallic and bimetallic active sites; (B) Schematic diagram of the hydrogenation process over bimetallic active sites. Note: Metal I sites are utilized to dissociate H2 to generate *H species. Metal II sites selectively adsorb the substrates. The migration of *H from Metal I to Metal II achieves selective hydrogenation of substrates.

A comprehensive understanding of hydrogenation mechanism is essential for the rational design of chemoselective catalysts[2,19,39-41]. Typically, heterogeneous hydrogenation involves two key steps: H2 dissociation and substrate hydrogenation, encompassing various reactants, intermediates, and products. The product selectivity directly depends on the adsorption strength and configuration of reactants/intermediates[42-45]. Nevertheless, the metal active sites with high selectivity often demonstrate limited capacity for H2 activation [Scheme 1A]. For instance, when single-atom sites are covered by substrates, H2 activation is hindered, leading to partial or complete sacrifice of activity[46-50]. Therefore, heterogeneous catalysts with bimetallic active sites have been investigated for selective hydrogenation

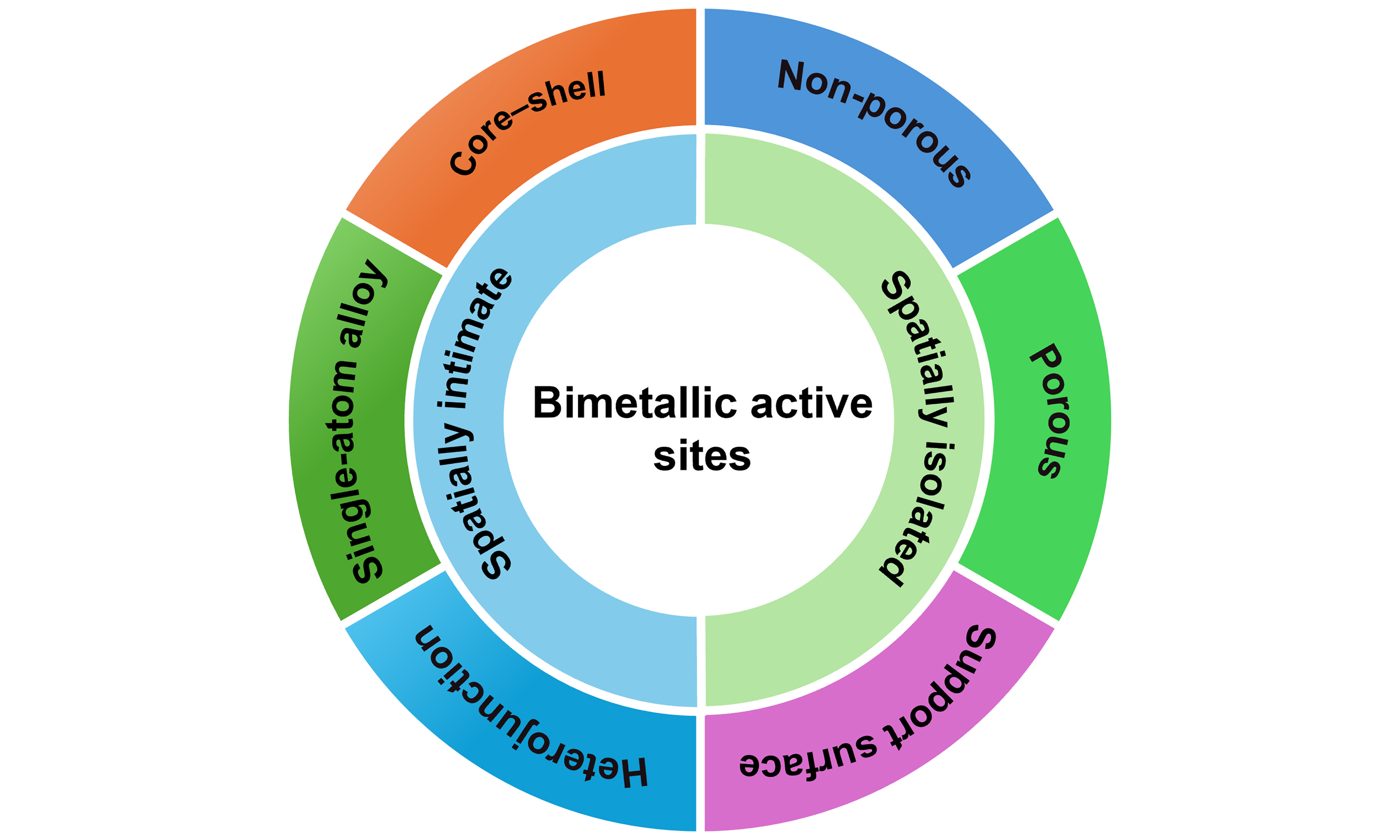

The key to achieving selective hydrogenation with bimetallic active sites lies in the precise spatial configuration of the two metal components. Currently, bimetallic catalysts are categorized into two types based on their spatial distance, aiming to create tightly intimated and spatially separated active sites for target reactions. To investigate the influence of spatial distance on selective hydrogenation, this perspective provides a comprehensive overview of recent advancements. We focus on two representative configurations that exhibit a range of synergistic effects arising from the bimetallic components, encompassing electronic, atomic, sub-nanoscale, nanoscale, and long-distance influences. At the end, we present an outlook on the challenges and opportunities in the field. Different from recent reviews and/or perspectives about selective hydrogenation[32,62-67] or bimetallic catalysts[39,68,69], this is a new perspective that focuses on the distance effects of bimetallic active sites. This compilation will serve as a valuable scholarly resource, fostering innovative ideas for development of highly efficient hydrogenation catalysts.

SPATIAL DISTANCE OF BIMETALLIC ACTIVE SITES

Classification of bimetallic site catalysts based on spatial distance

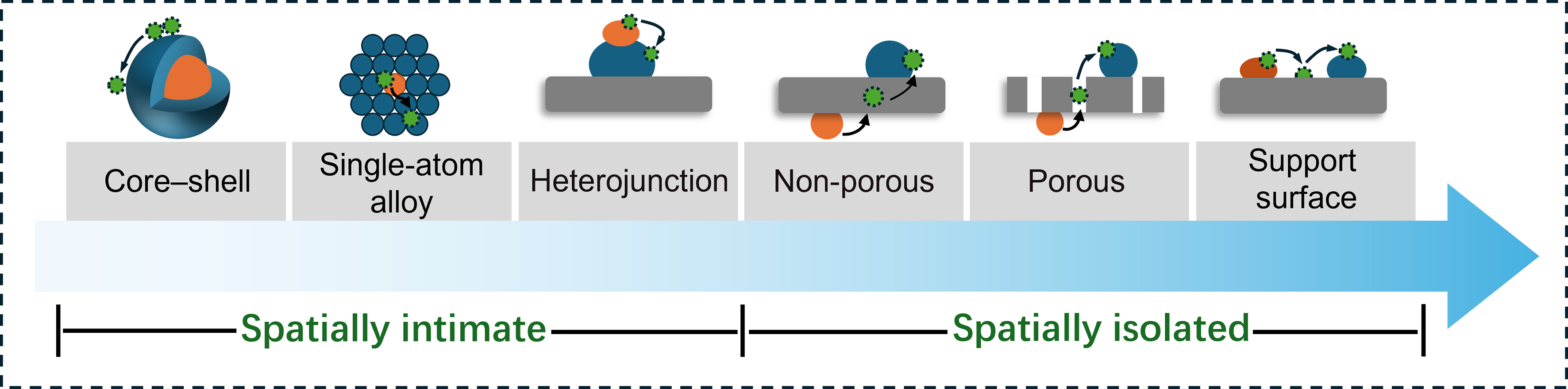

One crucial determinant influencing the activity and selectivity of bimetallic catalysts for selective hydrogenation is the spatial distance of bimetallic active sites[33,38,47]. The spatial distance refers to the degree of physical separation for the bimetallic active sites within the catalyst structure. For example, single-atom alloys (SAAs) can result in intimate mixing of two metal components at the atomic level, while core-shell structures or heterostructures can create distinct phases separated by a few nanometers[12,18]. Generally, this spatial distance can vary depending on a multitude of factors including but not limited to synthesis method, composition, and operating conditions. Meanwhile, the spatial distribution of metals can be affected by surface segregation, where one metal may migrate to the surface under reaction conditions, altering the spatial distance between bimetallic active sites[12,41,49]. As illustrated in Scheme 2, the initial structure of bimetallic catalysts can be classified into two distinct types: close proximity and spatial isolation. The bimetallic catalysts with close proximity are characterized by direct interaction of two metal active sites, encompassing core-shell structures, SAAs and heterojunction nanoparticles. The spatially separate bimetallic catalysts are achieved by isolating function supports, which can possess either porous or non-porous structures. The spatially separated active sites have also been demonstrated by anchoring two metal active sites on the support surface.

Scheme 2. Structure diagram of heterogeneous catalysts with bimetallic active sites. Typical spatial configurations encompass both the spatially intimate bimetallic active sites (including core-shell, single-atom alloy, and heterojunction) and the spatially isolated bimetallic active sites (including isolated by non-porous materials, isolated by porous materials and support surface).

The spatial distance of bimetallic catalysts exerts a significant influence on the mechanisms of selective hydrogenation. The characteristic features of bimetallic active sites with varying spatial distances are summarized in Table 1. For example, in the case of SAAs with close proximity, H2 molecules dissociate on individual metal active sites, while the substrate molecules selectively hydrogenate on host metal active sites through spilled H* species. Furthermore, the electronic interaction of the host metal can be modified by single-atom metals, altering their adsorption behavior toward the substrate. In contrast, when metals are separated by larger distances, interfaces between metal active sites and supports become more prominent. These interfaces can act as active sites for H2 activation and subsequent transfer to adsorbed reactants, resulting in unique reaction pathways. The electronic interactions across interfaces can modify the adsorption energies of reactants and intermediates, influencing the reaction kinetics and selectivity. The following sections will describe each bimetallic catalyst in detail.

Summary characteristic features of bimetallic active sites

| Classification | Advantages | Limitations | |

| Spatially intimate | Core-shell | · Modifying electronic properties of shell metal via core metal interactions[70,71] · Resistance to agglomeration and sintering of core metal[71,72] | · Difficulty in separating H2 activation and reactant hydrogenation[73] |

| Single-atom alloy | · Maximizing atomic utilization of noble metal[74,75] · Unique electronic structure of bimetallic interface[76] | · Synthesis challenge[74] · Localized structural regulation during hydrogenation[74] | |

| Heterojunction | · Improved catalyst stability[77] · Electron interaction[77] | · Difficulty of optimization and regulation[74] · Debate on the catalytic mechanism | |

| Spatially isolated | Isolated by non-porous materials | · Separating H2 activation and reactant hydrogenation[78] · Excellent stability[78] | · Low utilization of metal sites[79] · Limited mass transfer |

| Isolated by porous materials | · Separating H2 activation and reactant hydrogenation[80] · Improved mass transfer[80] | · Molecular diffusion resistance[61] · Complex preparation process | |

| Support surface | · High metal atom utilization[81,82] · Excellent mass transfer[83] | · Difficulty in eliminating physical contact · Difficulty in controlling spatial distance[49] | |

Characterization techniques for bimetallic active sites

Characterization techniques serve as a critical function for investigating structure-activity relationships. Various advanced techniques have been developed to deepen the understanding of bimetallic catalysts, from initial physicochemical properties to dynamic interactions[84-88]. In particular, the development of in situ techniques facilitates real-time monitoring of the interaction between intermediates and active sites, thereby enabling a more profound understanding of the catalytic mechanism for improved activity and selectivity on bimetallic active sites. Generally, advanced electron microscopy techniques [such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)] can directly observe the spatial distance for the bimetallic active sites and the dynamic changes during the reaction process[89,90]. Furthermore, in situ spectroscopy and energy spectroscopy play crucial roles in monitoring the adsorption behavior of substrate molecules and intermediate species on the bimetallic active sites.

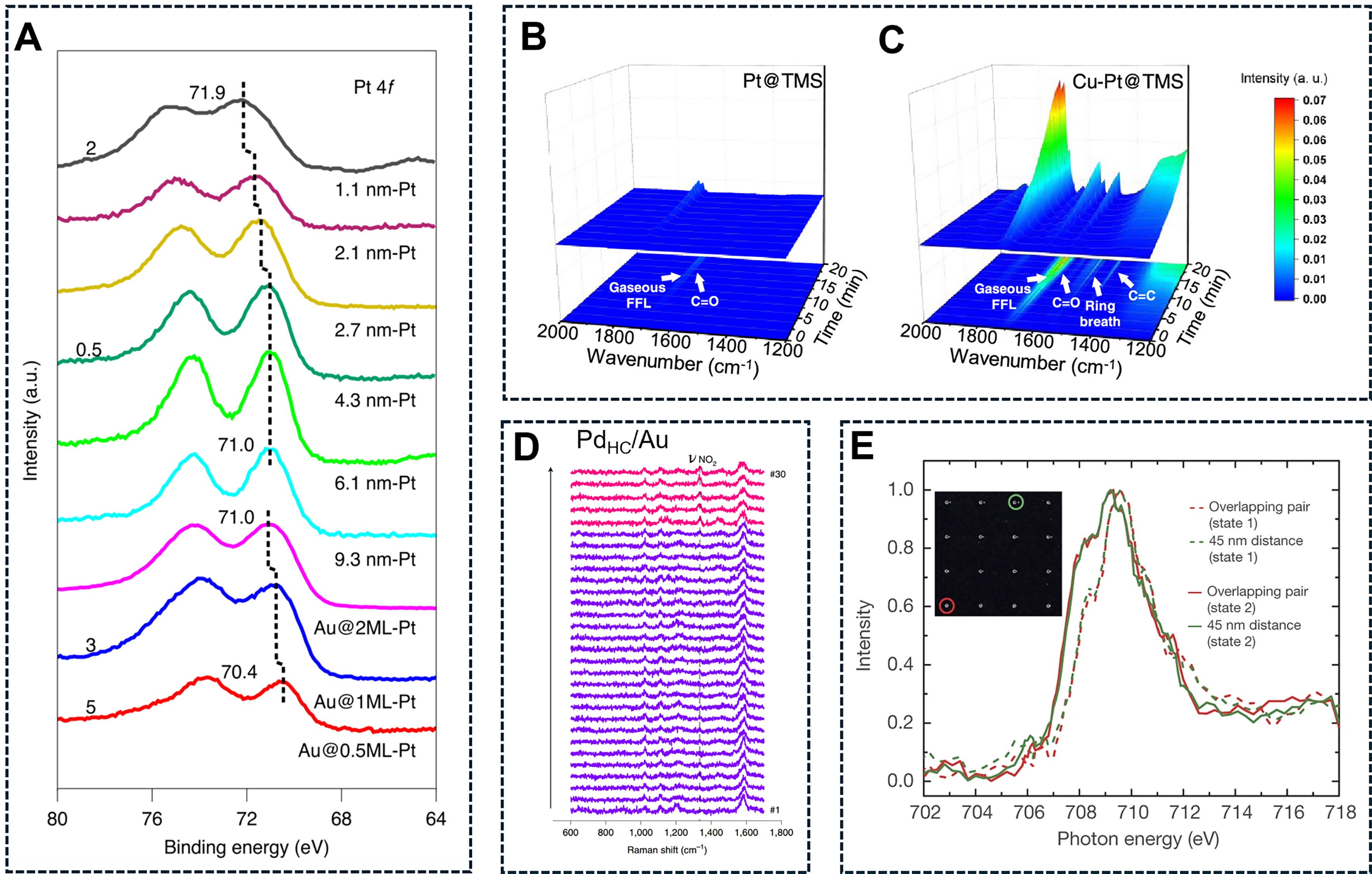

Typically, in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provides detailed information to identify the direct interaction between two metal active sites through surface electronic analysis[91]. As illustrated in Figure 1A, in situ XPS analysis showed that the binding energy of Pt 4f7/2 in the Au@Pt catalysts shifted to higher values compared to monometallic Pt particles. This shift indicated electron transfer from Au to the neighboring Pt atoms. Consequently, the enhanced selectivity of the Au@Pt core-shell catalysts could be attributed to the altered electronic density of Pt sites.

Figure 1. (A) In situ XPS analysis of Pt 4f core level spectra for the Pt and Au@Pt catalysts during reduction process. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[91]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature; In situ FT-IR spectra of FFL adsorption on (B) Pt@TMS and (C) Cu-Pt@TMS. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[92]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (D) TER spectra extracted from the TERS maps of CNBT SAMs on PdHC/Au, acquired along the regions in the STM images with a spectrum recorded every 10 nm. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[58]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature; (E) Fe L3 XAS spectra for the platinum and iron oxide on TiO2 with an interparticle distance of 45 nm and the overlapping pair. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[38]. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature. XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; FT-IR: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; FFL: fluoroformyl ligand; TMS: titanosilicate molecular sieve; TERS: tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy; TER: tip-enhanced Raman; SAM: self-assembled monolayer; STM: scanning tunneling microscopy; XAS: X-ray absorption spectroscopy; CNBT: 4-chloro-3-nitrobenzenethiol; PdHC: hydrogen-covered palladium cluster.

Meanwhile, in situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) techniques are predominantly utilized for characterizing bimetallic active sites in various hydrogenation reactions by monitoring the adsorption of reactants, intermediates, and/or products on the catalyst surface. For instance, Wang et al. investigated the selective adsorption of reactants on Cu-Pt@TS-1 zeolite@mesoporous (TMS) with bimetallic active sites of Cu and Pt[92]. Since the Pt sites were confined within TMS, furfural (FFL) molecules exhibited undetectable infrared signals on Pt@TMS surfaces [Figure 1B]. Upon introducing Cu active sites, characteristic peaks corresponding to C=O (1,720 cm-1), C=C (1,474 cm-1) and furan ring (1,578 cm-1) became evident on the Cu-Pt@TMS surface [Figure 1C]. These findings indicated that the selective adsorption of FFL molecules on Cu active sites enables their selective hydrogenation.

Yin et al. utilized tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) in conjunction with scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) to investigate the selective hydrogenation of chloronitrobenzenethiol (CNBT) over the Pd/Au catalysts[58]. The adsorption of CNBT on Au surface is relatively stable; however, CNBT hydrogenation remains minimal due to the weak dissociation of H2 on Au surface. Notably, when high-coverage Pd was electrodeposited on the Au surface to form the PdHC/Au bimetallic catalysts, the CNBT hydrogenation was significantly improved. Specifically, TERS maps of CNBT on PdHC/Au exhibited the disappearance of the characteristic peak (-NO2) at 1,336 cm-1 and a shift in the C=C stretching frequency

Additionally, Karim et al. reported an in situ X-ray adsorption spectroscopy to investigate the reduction of iron oxide nanoparticles[38]. As shown in Figure 1E, the Fe XAS spectra of separated Pt and iron oxide nanoparticles with varying distances were compared before and after the passage of H2. The in situ XAS spectra revealed that the reduction of iron oxide in bimetallic active sites of iron oxide and Pt with different distances was equal after hydrogenation at 343 K. These results further indicated that the occurrence of hydrogen spillover between the spatially separated Pt and FeOx sites.

SPATIALLY INTIMATE BIMETALLIC CATALYSTS

The spatially intimate bimetallic catalysts encompass the core-shell catalysts, SAAs, and heterojunction catalysts. A summary of representative bimetallic catalysts and their catalytic performance for selective hydrogenation is provided in Table 2. In this section, we will introduce the structural characteristics and catalytic properties of spatially intimate bimetallic catalysts in detail.

Summary of the spatially intimate bimetallic catalysts for selective hydrogenation

| Catalysts | Bimetallic active sites | Substrate | T (oC) | P (MPa) | Conv. (%) | Sel. (%) | Ref. |

| 20PdAu/SiO2 | Heterojunction | Benzaldehyde | 150 | 2 | 100 | 100 | [49] |

| [email protected] ML-Pd | Core-shell | Acetylene | 40 | - | 90 | 71 | [93] |

| Ni-Pd/C | Heterojunction | Nitrile | 80 | 0.6 | 99 | 99 | [94] |

| RuNi SAA | Single-atom alloy | 4-nitrostyrene | 60 | 1 | 100 | 99 | [95] |

| Au@1ML-Pt | Core-shell | Chloronitrobenzene | 65 | 0.3 | 99 | 99 | [91] |

| 10cGaAg@Pd/SiO2 | Core-shell | Acetylene | 80 | 0.1 | 95 | 92 | [96] |

| Pd1/Cu(100) | Single-atom alloy | Phenylacetylene | 30 | 0.1 | 100 | 96 | [17] |

| PtCu-SAA | Single-atom alloy | Glycerol | 200 | 2 | 99.6 | 99.2 | [97] |

| Pd1Ni SAA | Single-atom alloy | Benzonitrile | 80 | 0.6 | 100 | 90 | [98] |

Core-shell bimetallic catalysts

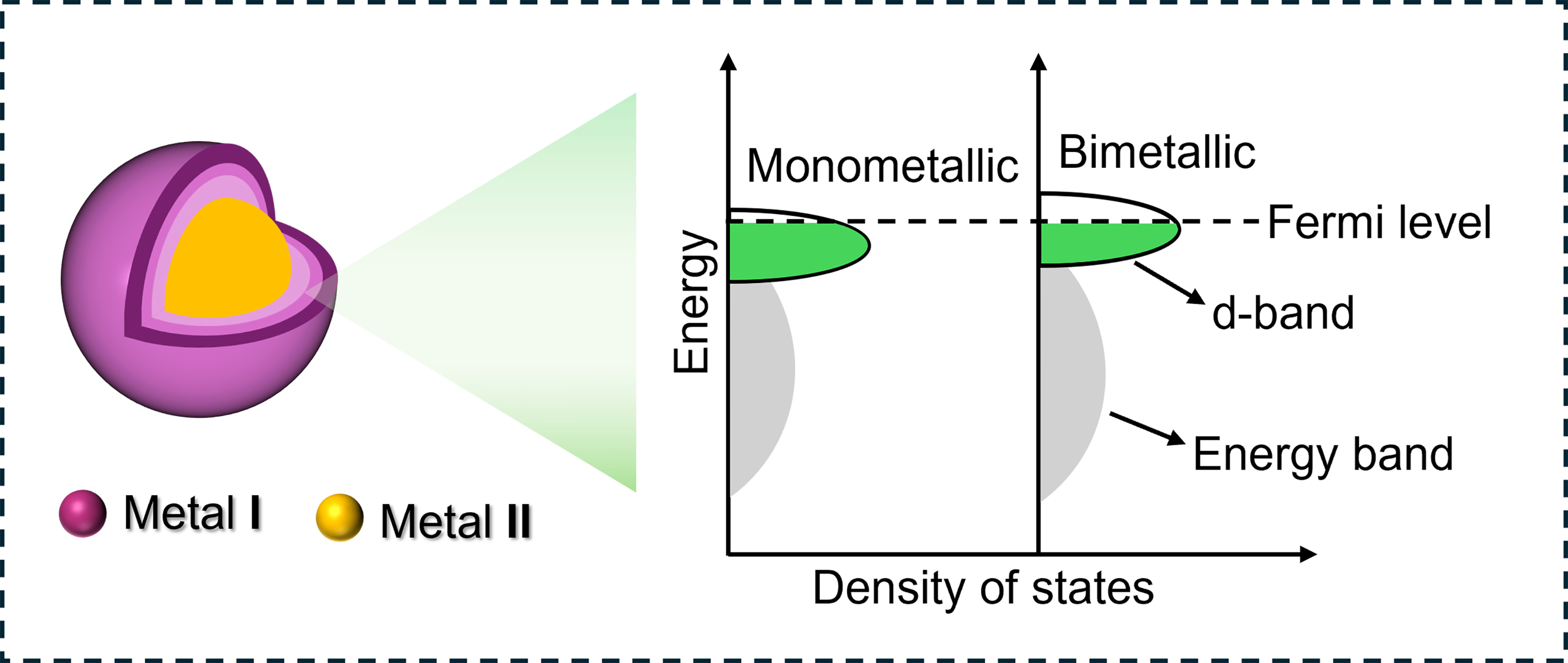

Bimetallic core-shell catalysts provide an alternative approach to modify electronic density of metal active sites[99,100]. As shown in Scheme 3, these catalysts comprise an inner core composed of one metal surrounded by a shell of another metal. Such core-shell structures can enhance stability against sintering or leaching of core metal active sites. Meanwhile, due to the presence of core metal, the lattice spacing of shell metal commonly undergoes contraction or expansion. As a result, the electronic density of the shell metal can be regulated through the electronic (ligand) and/or geometric (strain) effects, which shift the d-band center toward the Fermi energy level for promoting selective adsorption and activation of reactants. Therefore, core-shell bimetallic catalysts have demonstrated remarkable performance in various selective hydrogenation reactions, including the hydrogenation of alkenes, alkynes, nitroarenes, and carbonyl compounds.

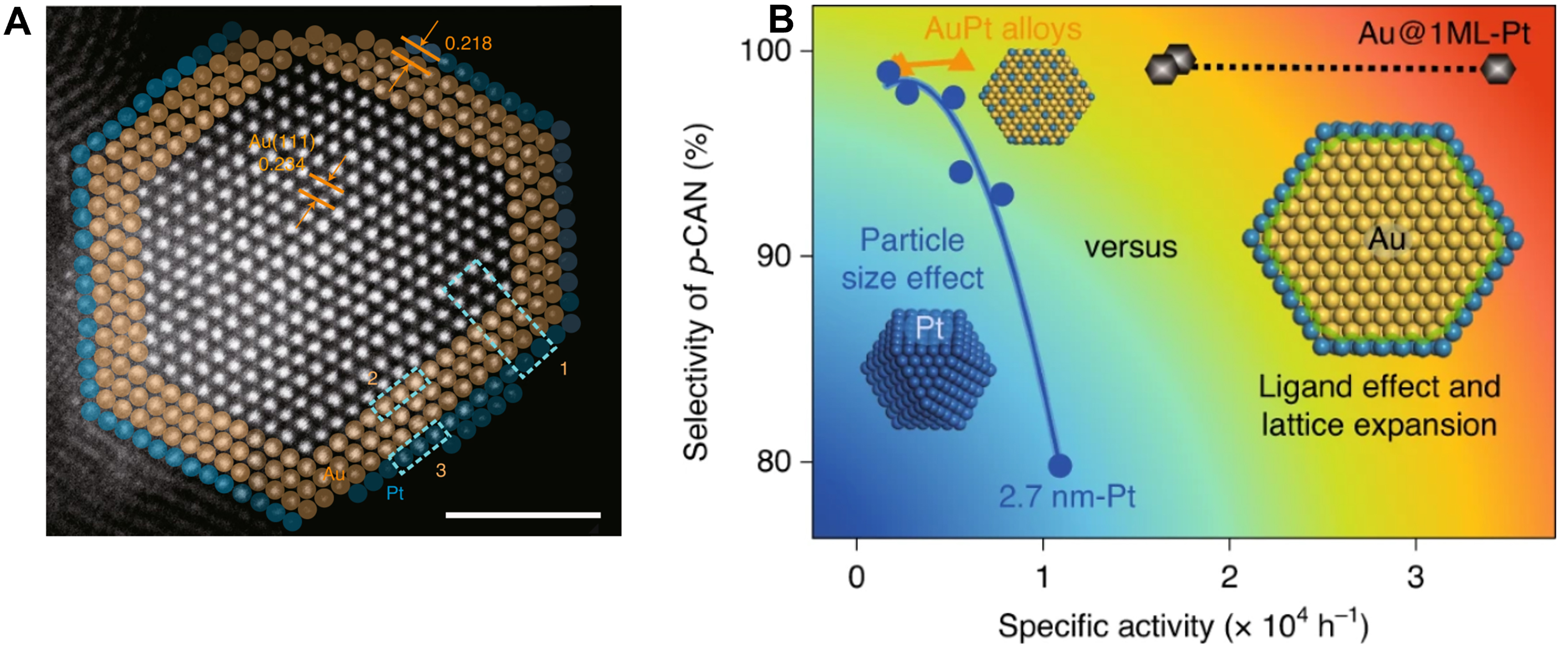

A typical type of core-shell bimetallic catalyst involves a core metal that cannot activate H2, yet significantly regulates the electronic structure of the shell metal[101-104]. For instance, Au@Pt core-shell catalysts were fabricated by Guan et al. through the precise deposition of Pt shell on the surface of Au

Figure 2. (A) HAADF-STEM image of Au@1ML-Pt; (B) The performance of Pt with different sizes, gold, AuPt alloy and Au@Pt for p-CNB hydrogenation. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[91]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. HAADF-STEM: High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy; p-CNB: para-chloronitrobenzene.

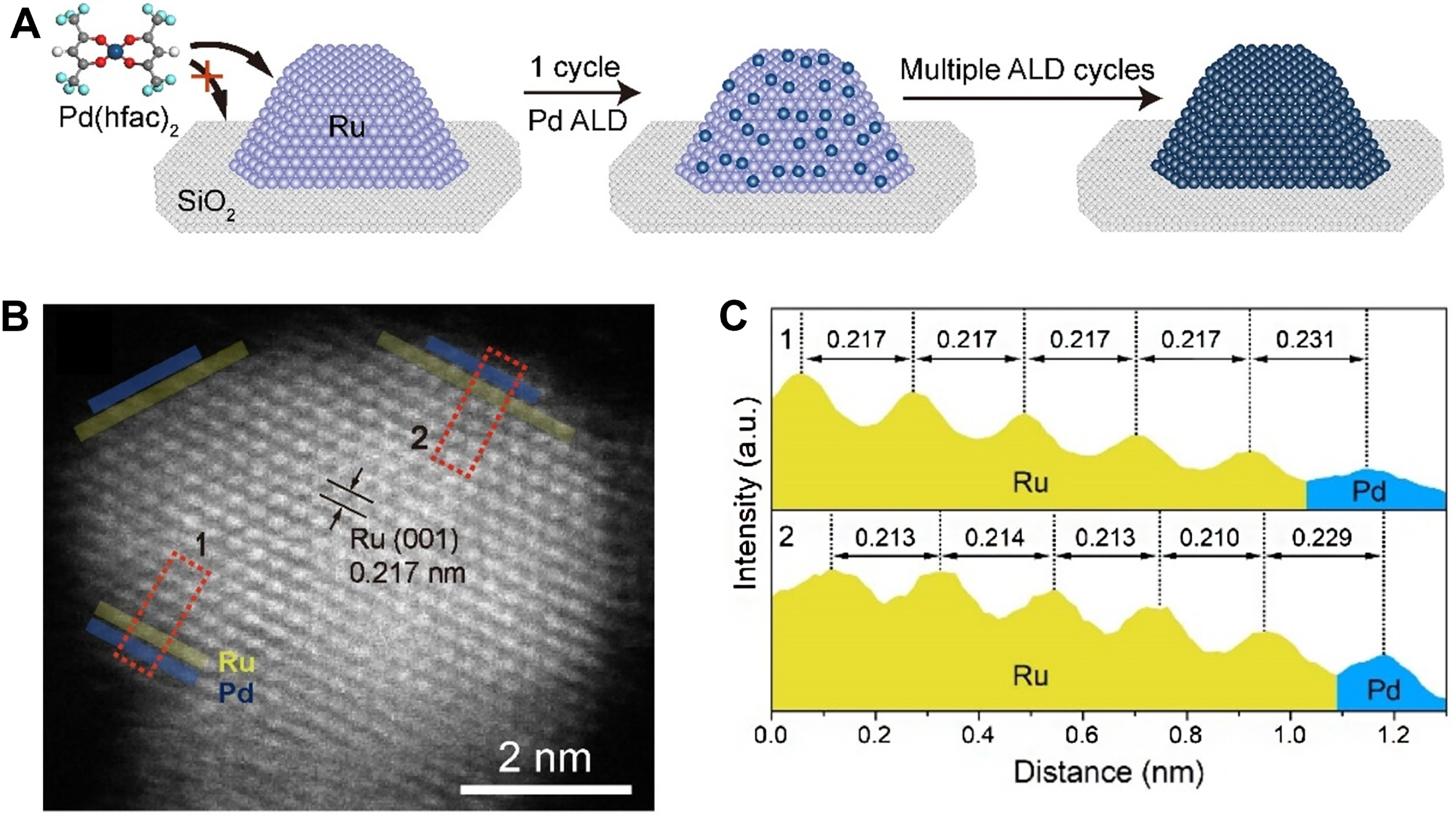

Another typical case is that both the core and shell metals possess exceptional capacity of H2 activation[105]. Zhu et al. constructed the Ru@Pd core-shell catalysts with a precisely controlled shell thickness of Pd on Ru nanoparticles using ALD technology[93] [Figure 3A and B]. Compared to Ru(5.1 nm)/SiO2, all Ru@xML-Pd (x: 0.7, 1.6, 2.3) catalysts displayed remarkable activity for the selective semi-hydrogenation of acetylene, achieving complete conversion of acetylene at approximately 50 °C [Figure 3C]. Furthermore, the

Figure 3. (A) Scheme of the preparation of Ru@Pd bimetallic catalysts; (B) HAADF-STEM image of Ru(5.1 nm)@0.7ML-Pd; (C) Lattice spacing along the direction of the dashed line of the numbered rectangle. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[93]. Copyright 2023, John Wiley and Sons. HAADF-STEM: High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy.

Single-atom alloy bimetallic catalysts

Since the discovery of excellent properties in semi-hydrogenation, SAAs have played an increasingly important role in selective hydrogenation[74,106-110]. Unlike metal alloys, SAAs are typically catalysts composed of bimetallic sites where small amounts of isolated metal atoms are present in the surface layer of a metal host[111-114]. Normally, noble metals (e.g., Pt, Pd, and Ru) with high capacity of H2 dissociation are atomically dispersed on relatively inert metals (e.g., Ag and Cu). As shown in Scheme 4, H2 dissociation occurs on isolated metal atoms while reactant activation takes place on host metals; the generated H* species migrate from isolated metal to host metal for reactant hydrogenation. Due to the unique geometry of SAAs, the decoupling between the location of the transition state and binding sites of reaction intermediates often facilitates reactant dissociation while maintaining weak intermediate binding. Therefore, SAA catalysts have demonstrated remarkable performance in selective hydrogenation, including alkenes and alkynes, aromatic rings, C=O bonds, nitro groups, and biomass.

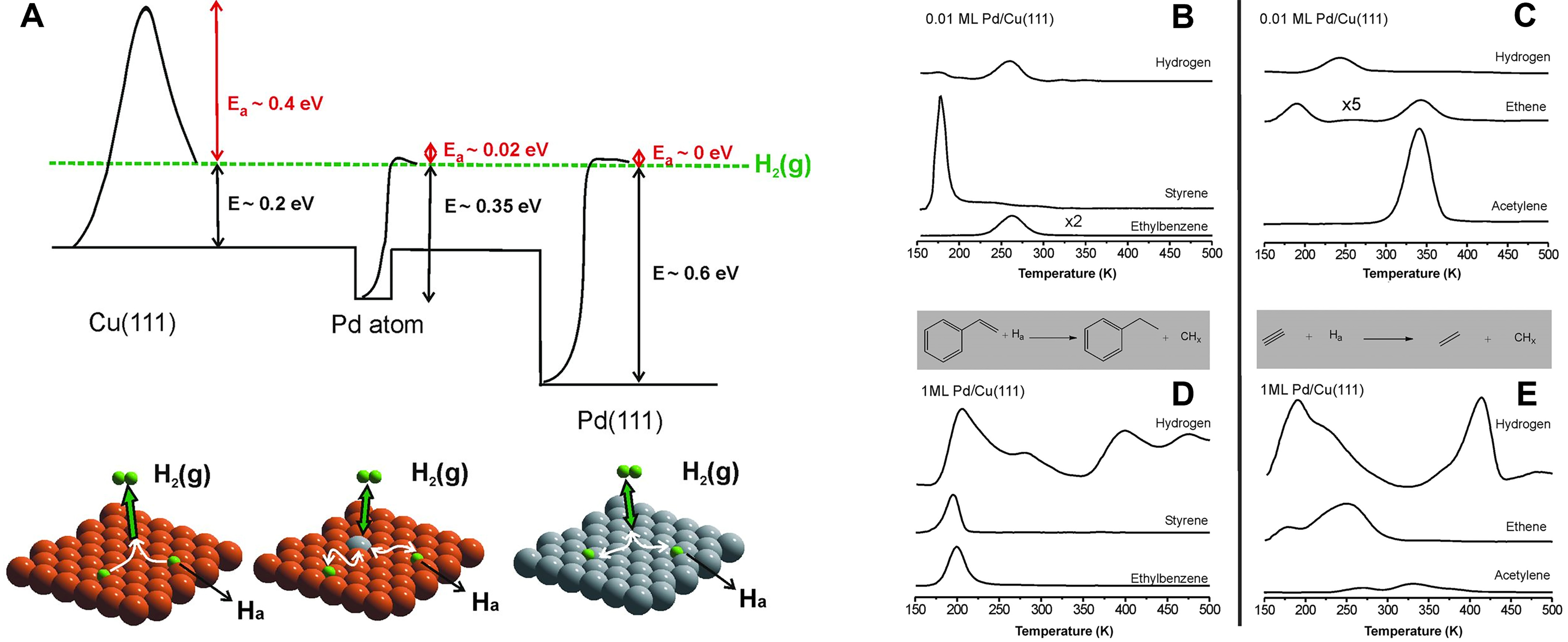

A representative example of SAAs involves the incorporation of individual Pd atoms onto the surface of Cu nanoparticles through electron beam evaporation in an ultra-high vacuum environment[107]. Notably, the purity of the Cu surface is crucial, particularly when doping Pd atoms exceeding 1 wt.%. The isolated Pd atoms can be stabilized on the surface Cu atoms under vacuum or diffused into the subsurface Cu layer at high temperature. The single-atom Pd/Cu alloys display an unconventional energetic landscape for H2 dissociation and chemisorption. The dissociative adsorption of H2 on Cu(111) is a highly activated process, while Pd(111) demonstrates a practically barrierless pathway for H2 dissociation. In the case of an isolated Pd atom, the dissociation barrier is low, and H* species are weakly bonded, thereby facilitating their migration onto the Cu(111) surface [Figure 4A].

Figure 4. (A) Potential energy diagram of pure Cu(111), pure Pd(111), and Pd SAA surfaces for H2 activation. Hydrogenation of (B) styrene and (C) acetylene on 0.01-ML Pd/Cu(111) alloy surface. Hydrogenation of (D) styrene and (E) acetylene on 1-ML Pd/Cu(111) alloy surface. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[107]. Copyright 2012, American Association for the Advancement of Science. SAA: Single-atom alloy.

The isolated active metal atom can substantially influence the catalytic performance of inert host metal atoms. For instance, the single-atom Pd1/Cu alloys can effectively achieve selective acetylene hydrogenation to ethylene. As illustrated in Figure 4B-E, temperature-programmed reaction (TPR) and STM experiments revealed that H* species can migrate from the Pd sites and populate the whole Cu(111) surface[107]. Acetylene reacts with pre-adsorbed H* species on Cu(111), resulting in a selectivity > 95%. In contrast, the large Pd islands on the Cu(111) surface can decompose acetylene and generate adsorbed CHx fragments on their surface that evolve H2, leading to considerably lower selectivity. Therefore, minority Pd atoms (1%) in a Cu surface to form single-atom Pd sites activate H2; the generated H* species spills over to bare Cu areas (99%) where it is weakly bound and effective for hydrogenation.

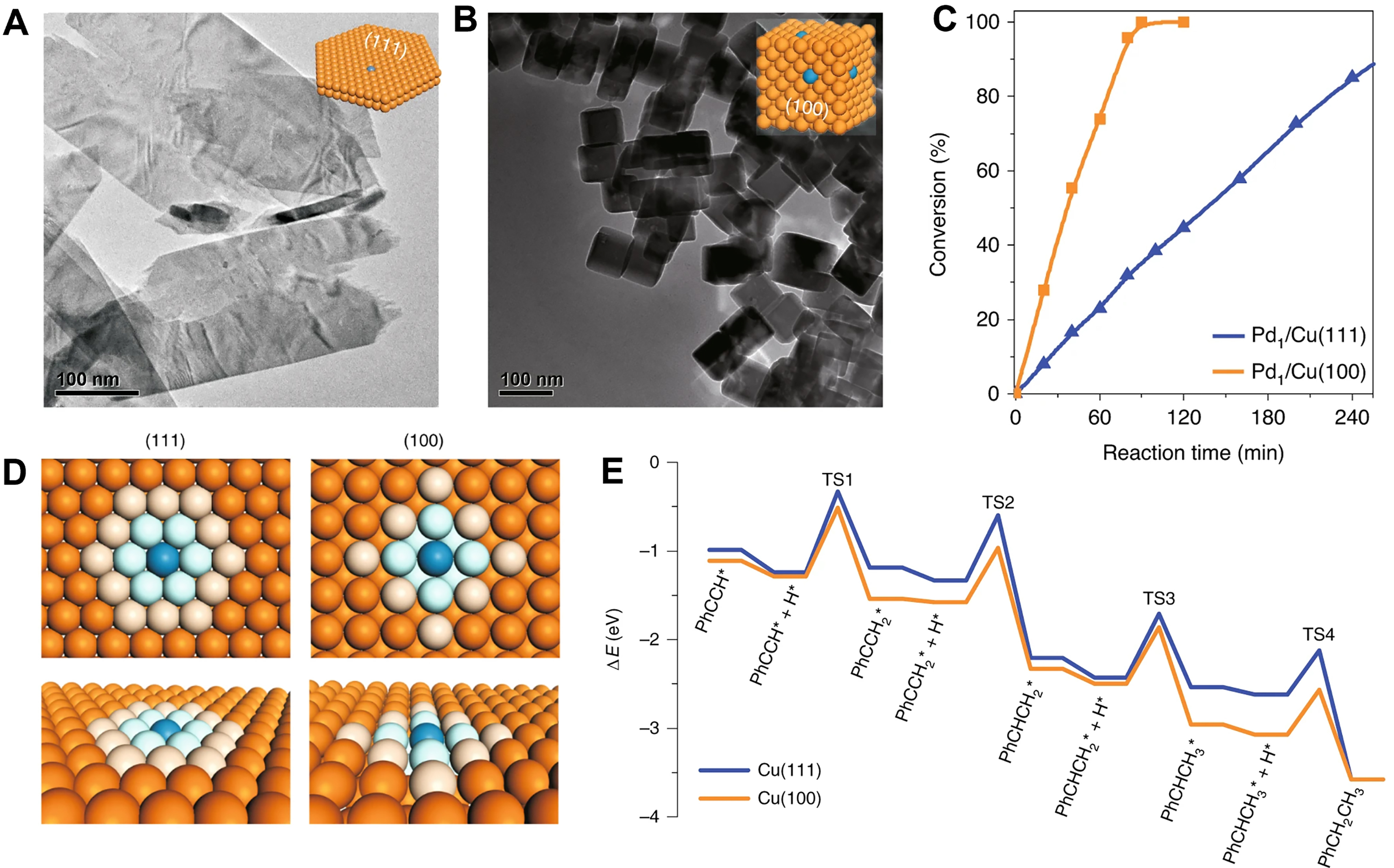

Notably, the capacity of H* migration on Pd1/Cu SAAs remains unaffected by the crystal face of the host Cu. Jiang et al. prepared the Pd1/Cu(111) and Pd1/Cu(100) catalysts by replacing Cu atoms with a small amount of Pd atoms on Cu nanosheets and Cu nanocubes, respectively, which exposed to (111) and (100) facets[17]

Figure 5. TEM images of (A) Pd1/Cu(111) and (B) Pd1/Cu(100). (C) Catalytic performance of Pd1/Cu(111) and Pd1/Cu(100) for the semi-hydrogenation of phenylacetylene. (D) and (E) Calculated barriers for stepwise hydrogenation of phenylacetylene on Cu surfaces with two low-Miller-index. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[17]. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature. TEM: Transmission electron microscopy.

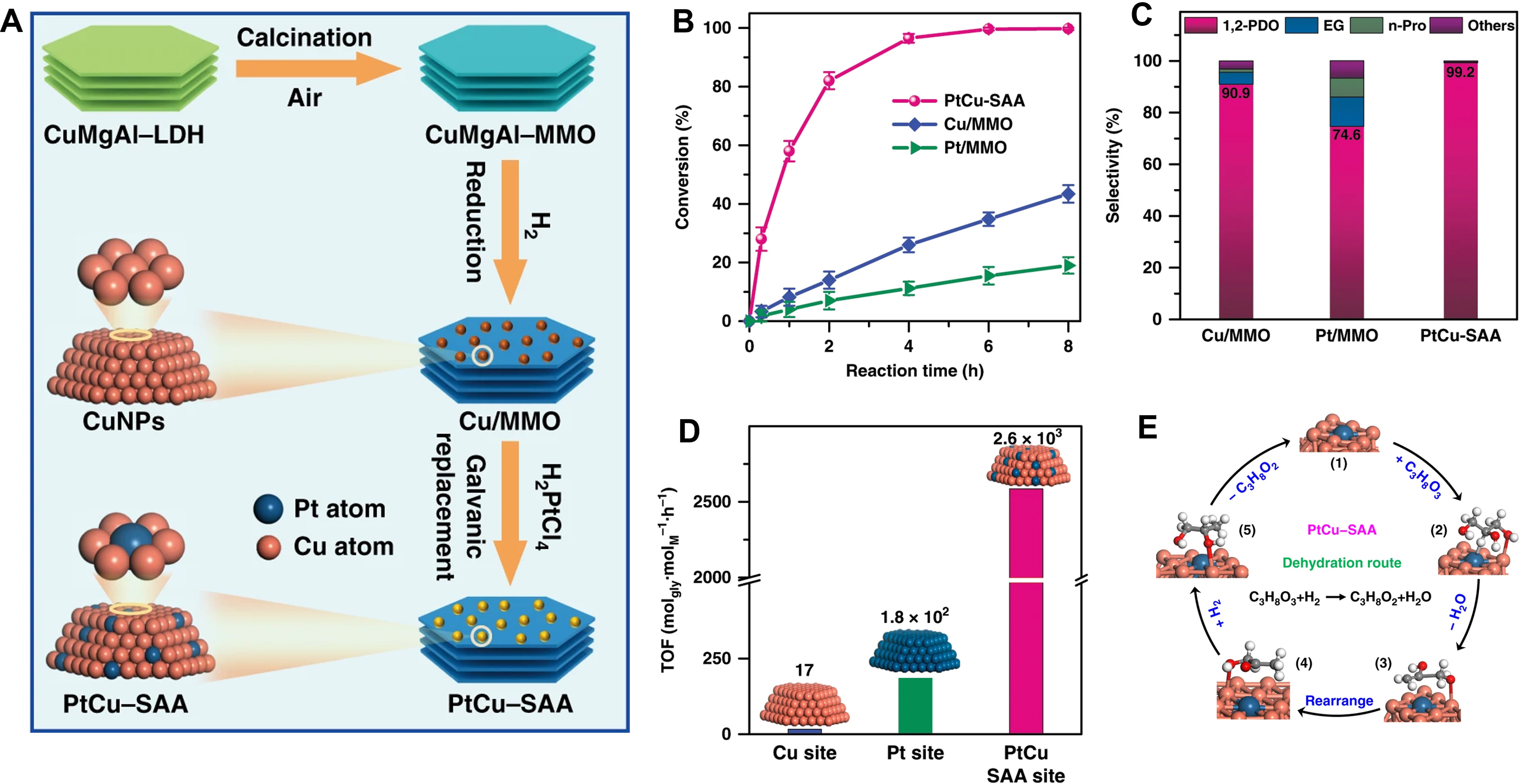

Additionally, the electrosynthesis process is also utilized for fabricating the SAA catalysts. For example, the Pt1Cu SAA catalysts were synthesized by Zhang et al., where Pt single-atoms were introduced onto the surface of Cu nanoclusters[97] [Figure 6A]. The Pt1Cu SAA catalysts demonstrated exceptional catalytic performance in the hydrogenation of glycerol, achieving a remarkable 99.2% selectivity for the target product of 1,2-propanediol at a glycerol conversion of 99.6%. In contrast, both Pt and Cu nanocatalysts exhibited poor conversion and significantly lower selectivities of 1,2-propanediol compared to Pt1Cu SAA

Figure 6. (A) Schematic illustration of the preparation of Pt1Cu SAA catalysts; (B) conversion versus reaction time, (C) product selectivity, and (D) TOF value towards glycerol hydrogenolysis to 1,2-PDO over the Pt1Cu SAA and monometallic catalysts (Pt/MMO and Cu/MMO); (E) Reaction mechanism of hydrogenolysis of glycerol to 1,2-PDO for the PtCu-SAA catalysts. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[97]. Copyright 2019, Springer Nature. SAA: Single-atom alloy; TOF: turnover frequency; PDO: propanediol; MMO: mesoporous metal oxide.

Heterojunction bimetallic catalysts

Heterojunction bimetallic catalysts offer another viable solution by combining two different metals within single nanoparticles, thereby creating synergistic effects that are not achievable with either metal alone [Scheme 5]. For instance, one metal facilitates the activation of H2, while the other promotes the adsorption of substrates, resulting in enhanced efficiency and selectivity of hydrogenation. Meanwhile, the heterojunction of these metals can induce alterations in the electronic density, consequently modifying adsorption energies of reactants and/or intermediates. Moreover, the presence of diverse metal domains creates unique surface sites and facets that enable multiple adsorption modes for reactants. By carefully adjusting the ratio of the two metals and selecting the appropriate supports, the electronic and geometric properties of the nanoparticles can be finely tuned to optimize performance for specific hydrogenation reactions.

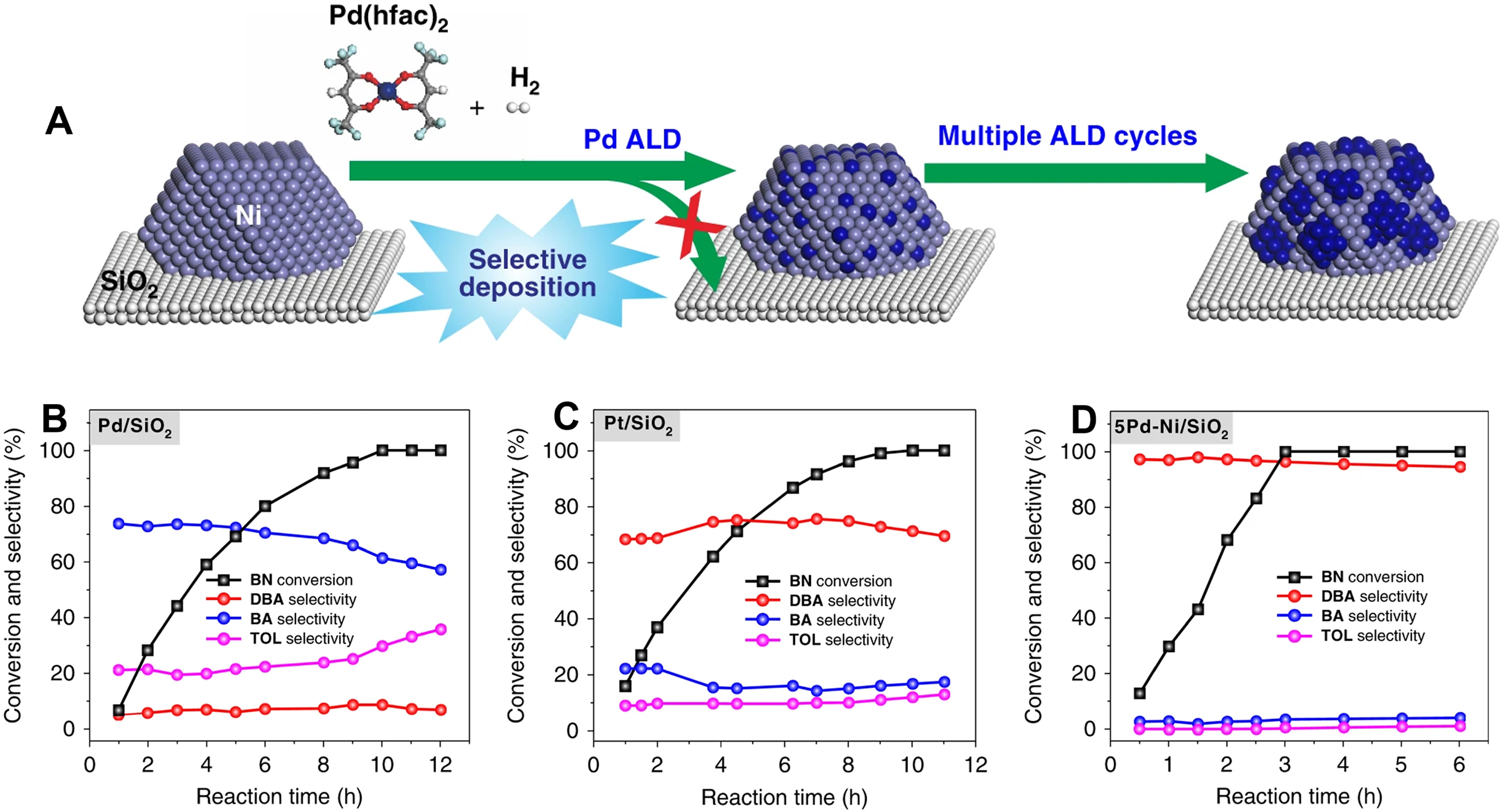

Zhang et al. utilized the ALD technology to selectively deposit Pd clusters onto the surface of Ni nanoparticles [Figure 7A], resulting in the formation of heterojunction 5Pd-Ni bimetallic nanoparticles on the SiO2 supports (5Pd-Ni/SiO2)[98]. Compared to Pd/SiO2, the dibenzylamine selectivity over 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 for benzonitrile hydrogenation significantly increased from approximately 5% to 97% [Figure 7B-D]. The synergistic effect between Pd clusters and Ni nanoparticles was found to prolong the adsorption of benzylamine intermediates, thereby forcing N-coupling reaction between benzylamine and benzylamine, and improving the selectivity of dibenzylamine. Additionally, the side reaction pathway involving deep hydrogenation of benzonitrile to toluene was effectively suppressed due to substantial consumption of benzylamine.

Figure 7. (A) Scheme of preparation process for xPd-Ni/SiO2. Catalytic performances of (B) Pd/SiO2, (C) Pt/SiO2, and (D) 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 for the benzonitrile hydrogenation. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[98]. Copyright 2019, Springer Nature.

SPATIALLY ISOLATED BIMETALLIC CATALYSTS

The spatially isolated bimetallic active sites are achieved by non-porous materials, porous materials, or support surfaces. A summary of representative bimetallic catalysts with spatially isolated active sites and their catalytic performance for selective hydrogenation is provided in Table 3. In this section, we will introduce the structural characteristics and catalytic properties of spatially isolated bimetallic catalysts in detail. Prior to this, we will discuss the hydrogenation capacity of the spilled H* species.

Summary of the spatially isolated bimetallic catalysts for selective hydrogenation

| Catalysts | Bimetallic active sites | Substrate | T (oC) | P (MPa) | Conv. (%) | Sel. (%) | Ref. |

| Pt&Fe2O3/CNT | Support surface | 4-nitrostyrene | 60 | 0.1 | 100 | 100 | [115] |

| Pt/Fe-TiO2 | Support surface | C=O bonds | 40 | 2 | 99 | - | [116] |

| PdSA+C/g-C3N4 | Support surface | Cinnamaldehyde | 80 | 1 | 100 | 97.3 | [117] |

| Cu-Pt@TMS | Porous materials | Furfural | 110 | 1 | 98.4 | 99.6 | [92] |

| Pt-Au/TMSN | Porous materials | Phenylacetylene | 50 | 3 | 96 | 91 | [118] |

| Pt1-Fe1/ND | Support surface | Nitrochlorobenzene | 80 | 1 | 100 | 100 | [119] |

| Ir1+NPs/CMK | Support surface | Quinoline | 100 | 2 | 99 | 99 | [120] |

| Ru/Pd/MCMOS | Support surface | Nitrobenzene | 80 | 2.5 | 99.9 | 99.2 | [121] |

| Ir1Mo1/TiO2 | Support surface | 4-nitrostyrene | 120 | 2 | 100 | 96 | [122] |

| Pd1+NPs/TiO2 | Support surface | Ketone/aldehydes | 40 | 0.3 | 100 | 99 | [45] |

| CoOx/TiO2/Pt | Non-porous materials | Cinnamic aldehyde | 65 | 2 | 91.3 | 81.5 | [123] |

| Pt-TiO2-Au | Non-porous materials | Nitrothiophenol | 60 | - | - | - | [52] |

| Ru@MHCS@Co | Support surface | CO/H2 | - | - | 11.9 | 69.6 | [124] |

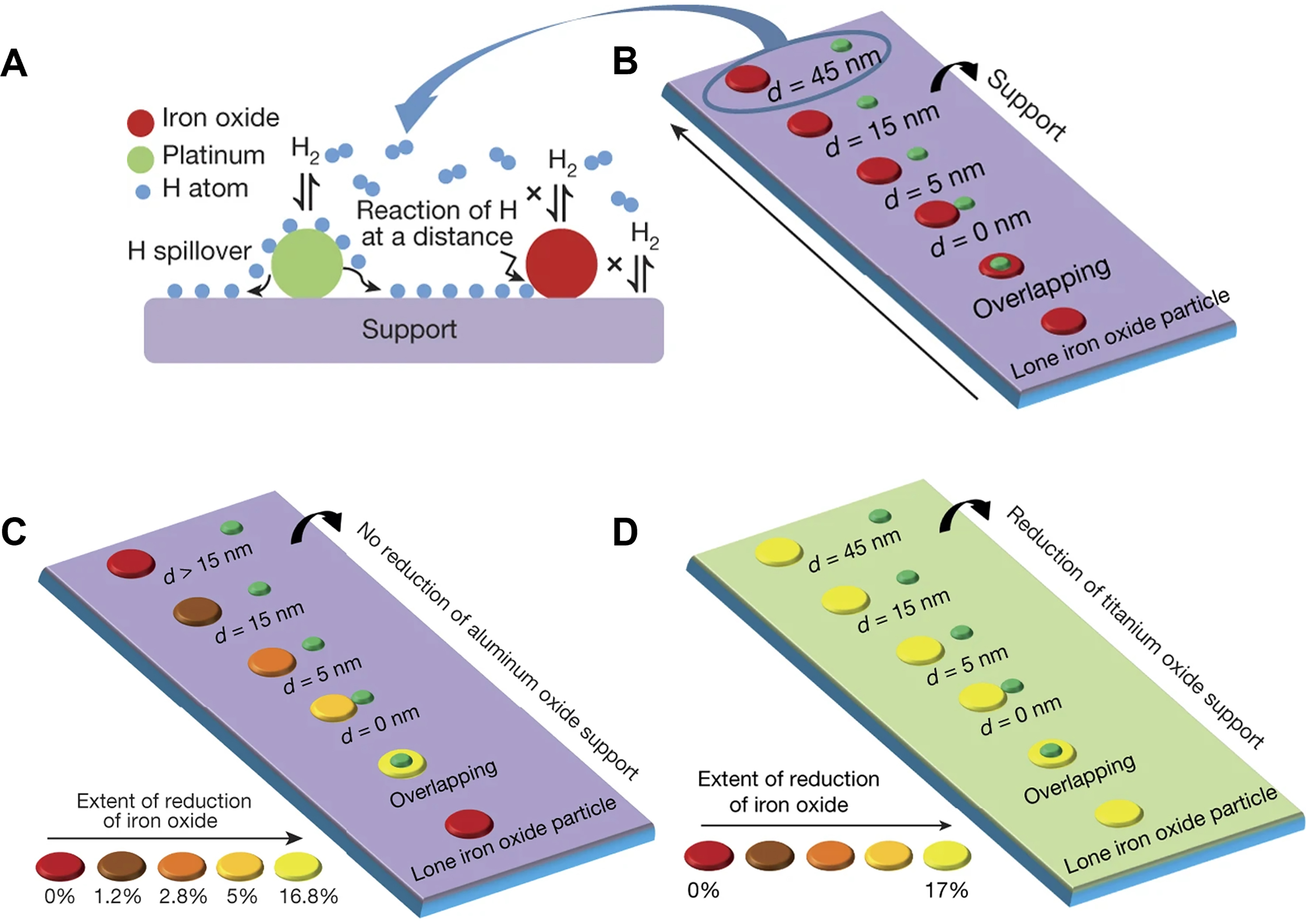

Hydrogen spillover, a well-known phenomenon in heterogeneous catalysis, involves H2 activation and cleavage at the metal sites, followed by migration of the generated H* species to the support surface[125-128]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the capability of reducible supports (TiO2, MoO3, CeO2, etc.) for H* spillover[92,123,129-133]. However, it remains uncertain whether this phenomenon occurs on non-reducible supports, such as silicon oxide, molecular sieve, porous silicon, etc[116,121,124,134-136]. Karim et al. prepared contamination-free, well-defined model systems using electron beam lithography (EBL)[38]. As shown in Figure 8A and B, the arrangement of Pt and Fe nanoparticles exhibits various distances on the support surface. In situ X-ray photoelectron microscopy revealed that hydrogen spillover occurs on both reducible TiO2 and non-reducible Al2O3. Specifically, the migration of H* species on the Al2O3

Figure 8. (A) Schematic illustration of H* spillover from the Pt surface to the iron oxide particles on TiO2 and Al2O3 surface. (B) The bimetallic site catalyst model consists of spatially separated Pt and iron oxide particles with various distances d. Platinum-iron oxide pairs with various distances d and a lone iron oxide particle on (C) TiO2 and (D) Al2O3. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[38]. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature.

Bimetallic catalysts isolated by non-porous materials

The bimetallic nanoparticles supported on reducible oxides typically form a heterojunction structure, with the reducible oxide walls serving as separators between two metal active sites [Scheme 6]. However, it is crucial to ensure that the wall thickness remains within an optimal range, as excessive thickness could impede hydrogen spillover and consequently lead to diminished activity or even complete inhibition of selective hydrogenation.

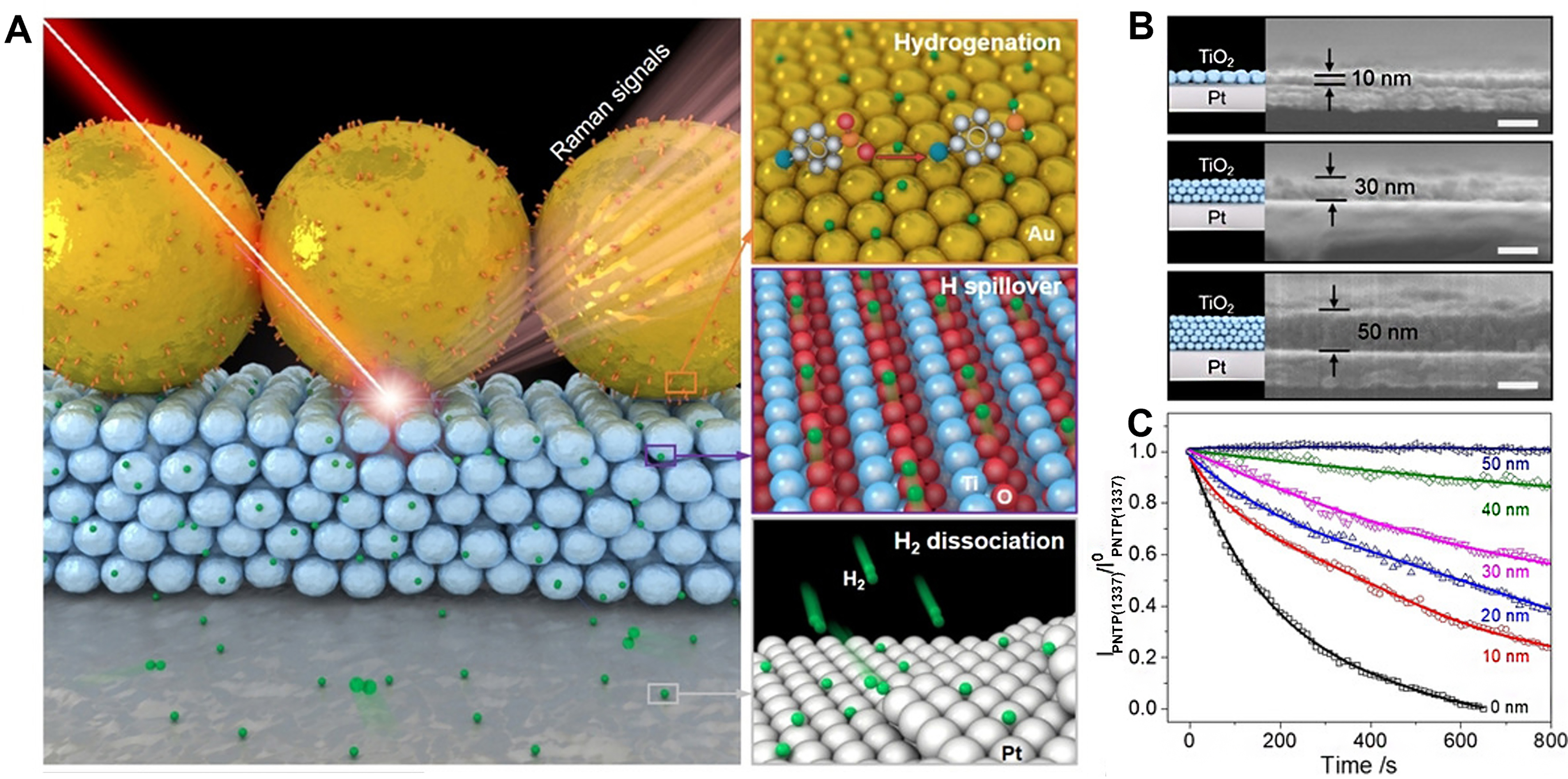

Wei et al. fabricated the Au/TiO2/Pt catalysts with sandwich interlayer structures[132]. The spatial separation of Au and Pt was achieved through precisely controlled thinness of TiO2 interlayers. Using in situ surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) [Figure 9A], the Au/TiO2/Pt catalysts exhibited significant activity of p-nitrothiophenol hydrogenation compared to the monometallic Au/TiO2 catalysts. Compared to the Au/SiO2/Pt catalysts with SiO2 as an interlayer, the enhanced activity of Au/TiO2/Pt could be attributed to the reducible TiO2 interlayer, which allows the migration of H* species from Pt to Au nanoparticles for p-nitrothiophenol hydrogenation. Furthermore, the hydrogenation activity of p-NTP exhibited a tendency to decrease with increasing distance, and was found to be inhibited at the distance of 50 nm [Figure 9B and C]. Therefore, rational regulation of the distance between two metals is the key to constructing bimetallic catalysts with sandwich structure.

Figure 9. (A) Scheme of hydrogen spillover on Au/TiO2/Pt; (B) Cross-sectional SEM images of TiO2/Pt; (C) Time-dependent intensity of the Raman band (at 1,337 cm-1) for the hydrogenation of p-NTP on Au/TiO2/Pt with different TiO2 layers. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[132]. Copyright 2020, John Wiley and Sons. SEM: Scanning electron microscopy; p-NTP: para-nitrothiophenol.

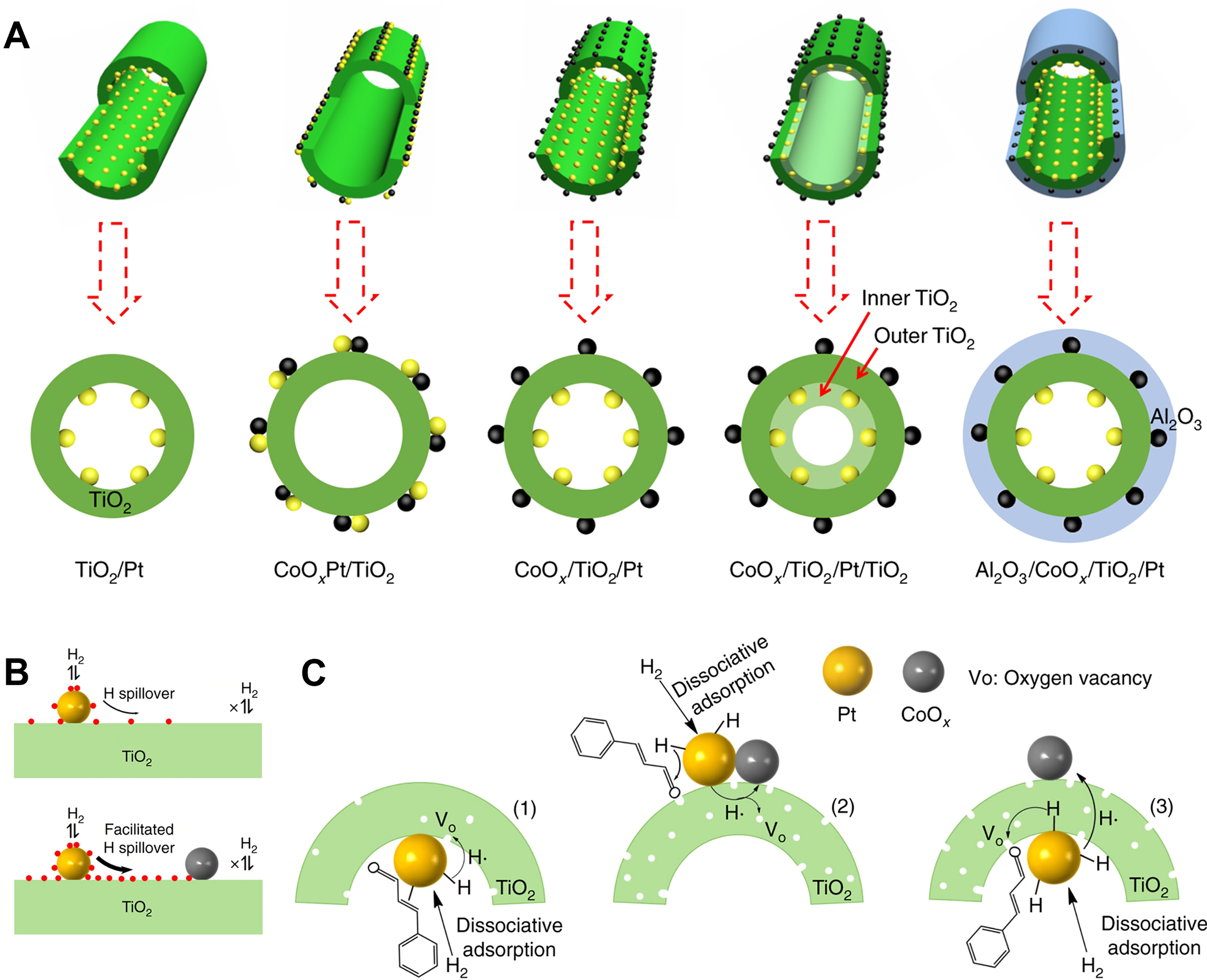

Due to the strong capacity of reducible supports for hydrogen spillover, the bimetallic catalysts featuring spatially separated metals occasionally demonstrated an equivalent synergistic effect compared to the closely contacted ones. Zhang et al. constructed both closely contacted CoOxPt/TiO2 and spatially separated CoOx/TiO2/Pt catalysts through ALD technology[123] [Figure 10A]. For selective hydrogenation of cinnamic aldehyde, similar to the closely contacted CoOxPt/TiO2 catalysts, the CoOx/TiO2/Pt catalysts also demonstrated enhanced selectivity toward cinnamyl alcohol, compared to TiO2/Pt or CoOx/TiO2. The interface of Pt and oxygen vacancies was identified as the active sites. As depicted in Figure 10B, hydrogen spillover is a reversible dynamic equilibrium process where the active H* species migrate across the TiO2 surface. The introduction of CoOx consumes a greater number H* species, thereby disrupting the original hydrogen spillover equilibrium. This new equilibrium facilitates the transfer of H* species to TiO2 supports, leading to higher concentrations of oxygen vacancies, providing abundant active sites for the C=O bond in cinnamic aldehyde for selective hydrogenation [Figure 10C].

Figure 10. (A) Semi-sectional and cross-sectional of CoOx/TiO2/Pt catalysts, where yellow and black spheres represent Pt and CoOx, respectively; (B) Schematic representation of the mechanism of CoOx effect on H spillover on the surface of TiO2c; (C) The possible enhancement mechanism for CALD selective hydrogenation. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[123]. Copyright 2019, Springer Nature. CALD: Cinnamaldehyde.

Bimetallic catalysts isolated by porous materials

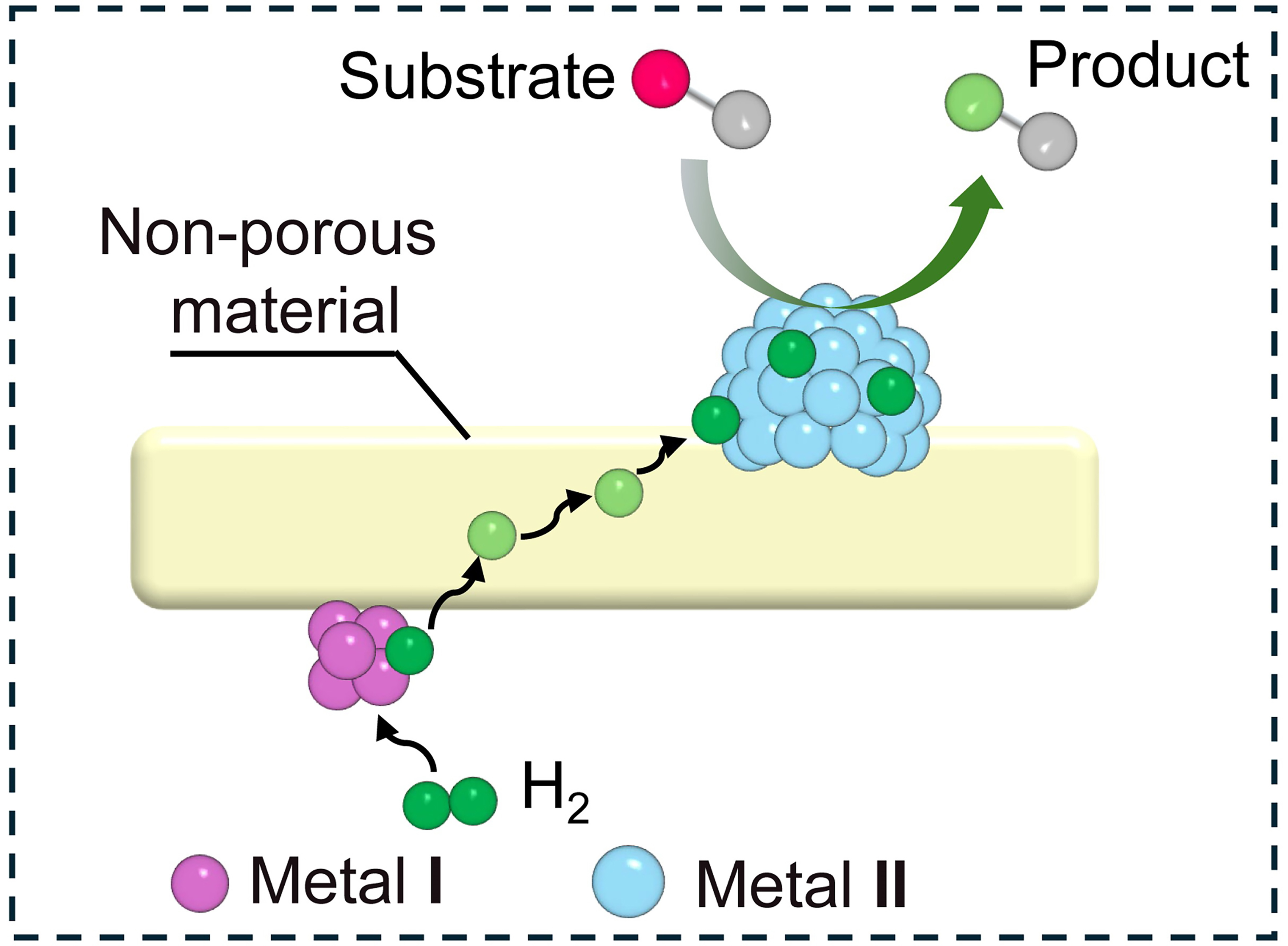

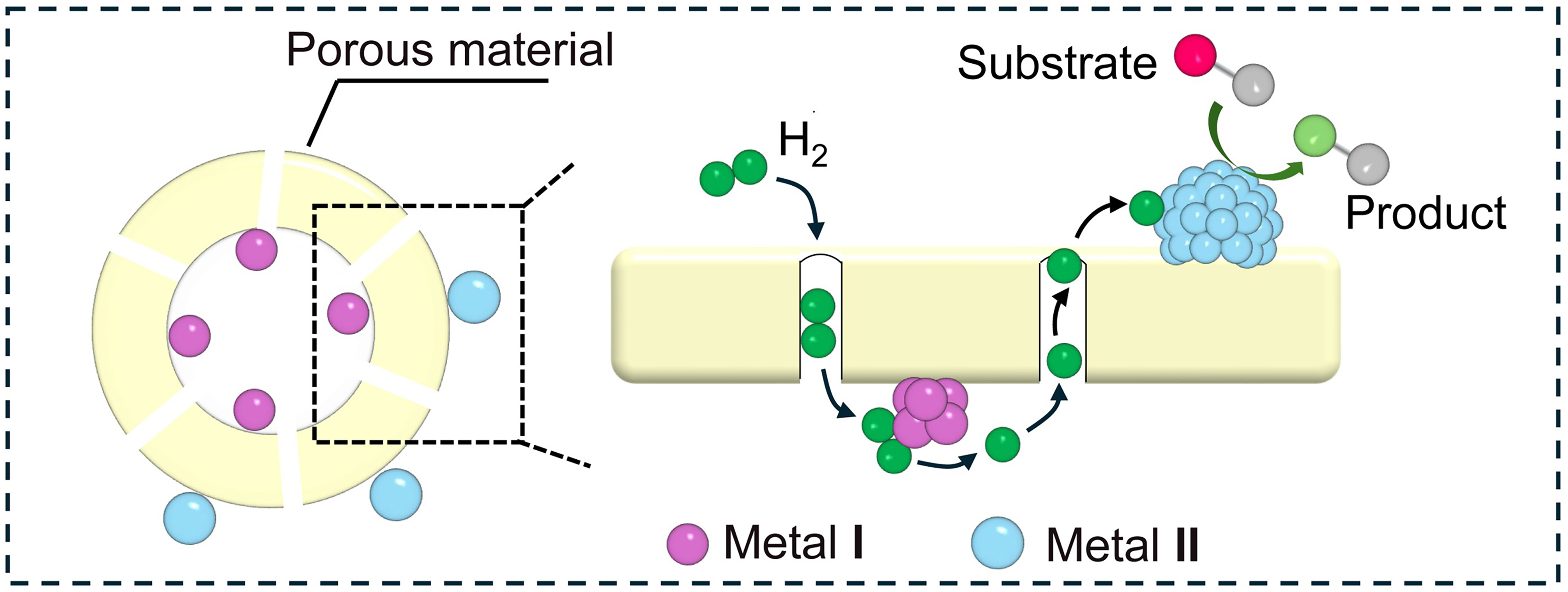

To eliminate the resistance of H2 diffusion, the spatial separation of bimetallic nanoparticles is typically accomplished by employing porous materials with a specific pore size. As shown in Scheme 7, the metal I nanoparticles are encapsulated in porous materials and the metal II active sites are anchored on the surface of porous isolation layers. The porous materials include graphitic carbon, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), zeolites, and oxides. Notably, it is crucial to precisely regulate the average pore size of these porous materials to facilitate H2 diffusion to metal I sites for activation, while blocking access to relatively large reactants. These reactants are absorbed onto metal II sites and hydrogenated via hydrogen spillover from metal I to metal II.

Scheme 7. Structure diagram of catalytic hydrogenation at spatially separated bimetallic site over shell-core model catalysts.

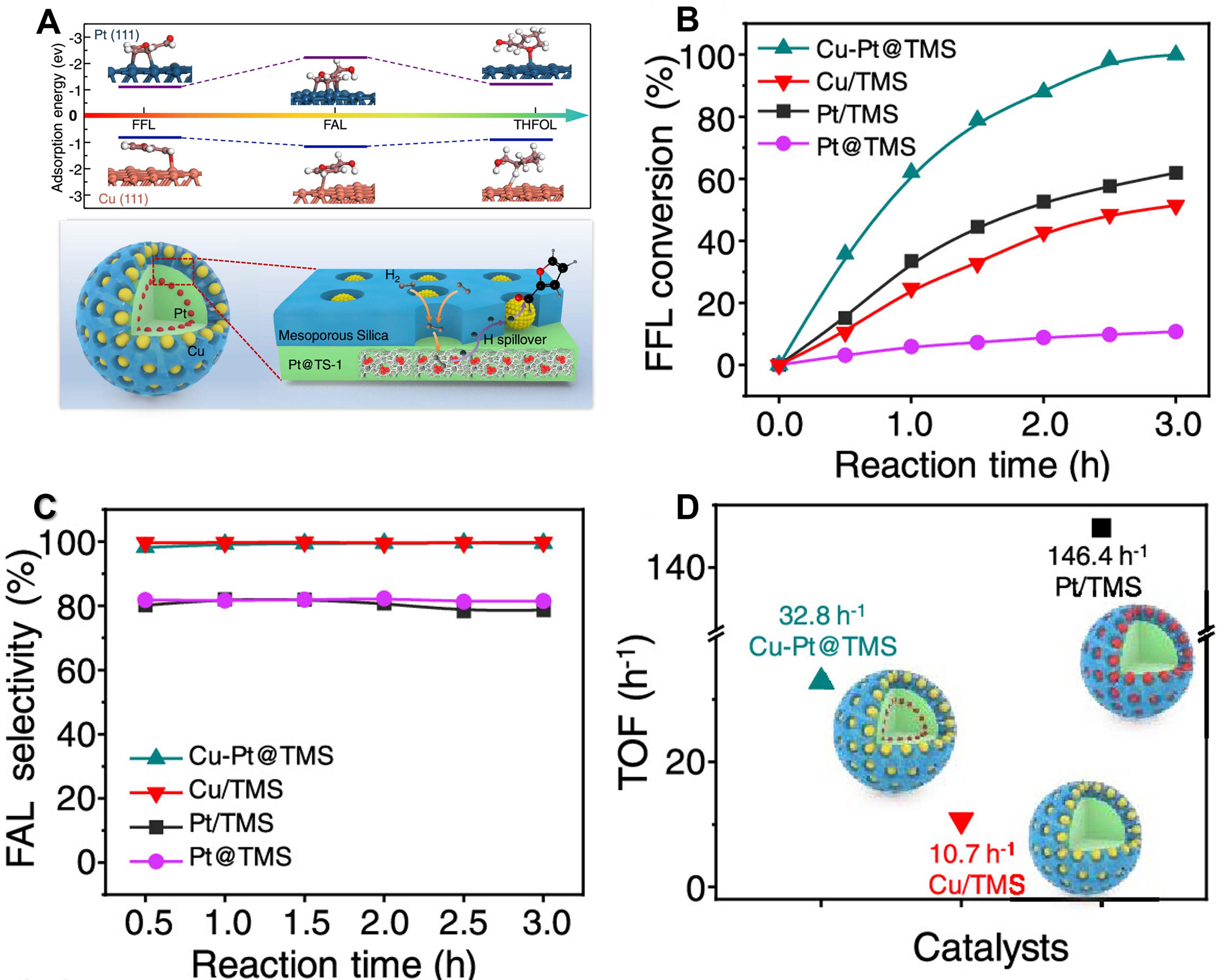

Typically, Wang et al. designed a modular bimetallic catalyst by synthesizing a core-shell structure of TMS, wherein Pt and Cu species are confined to micropores and mesopores, respectively[92]. Such a structure facilitates the facile dissociation of H2 at the Pt site, followed by migration of H* species to Cu nanoparticles for hydrogenation of adsorbed substrates [Figure 11A]. The synergistic interaction resulted in efficient FFL hydrogenation with a high turnover frequency (TOF) of 32.8 h-1 and remarkable furfuryl alcohol selectivity of > 99.6%, compared to the monometallic Cu/TMS and Pt@TMS catalysts [Figure 11B-D]. Furthermore, DFT calculations demonstrated the weaker adsorption of furfuryl alcohol on Cu(111) surface compared to Pt(111) surface, thereby suppressing its over-hydrogenation [Figure 11A].

Figure 11. (A) Adsorption behavior of Pt(111) and Cu(111) surfaces for FFL, FAL and THFOL; (B) FFL conversion; (C) FAL selectivity and (D) TOF value of Cu-Pt@TMS, Cu/TMS and Pt/TMS. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[92]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. FFL: Furfural; THFOL: tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol; FAL: furfuryl alcohol; TOF: turnover frequency; TMS: mesoporous silica.

Bimetallic nanoparticles on supports

In contrast to bimetallic catalysts with isolated layers, the precise control over the interparticle distance poses challenges when anchoring two distinct types of metal nanoparticles on functional supports. The complexity arises from the inherent differences in metal properties, the intricate nature of surface interactions, and the limitations of current synthesis methodologies. To date, there remains a conspicuous lack of an effective method capable of achieving accurate control over the spatial distance of bimetallic active sites. However, there are still successful cases in which the separated bimetallic active sites demonstrate significant advantages in selective hydrogenation[116,133-136]. As shown in Scheme 8, strategic positioning of metal nanoparticles enables the tailored electronic environment and optimization of synergistic effects of various metal sites, thereby unlocking unprecedented catalytic efficiency. Moreover, the separation of bimetallic sites allows for the fine-tuning of localized reaction environments, enabling the catalyst to discriminate between different reactants and intermediates.

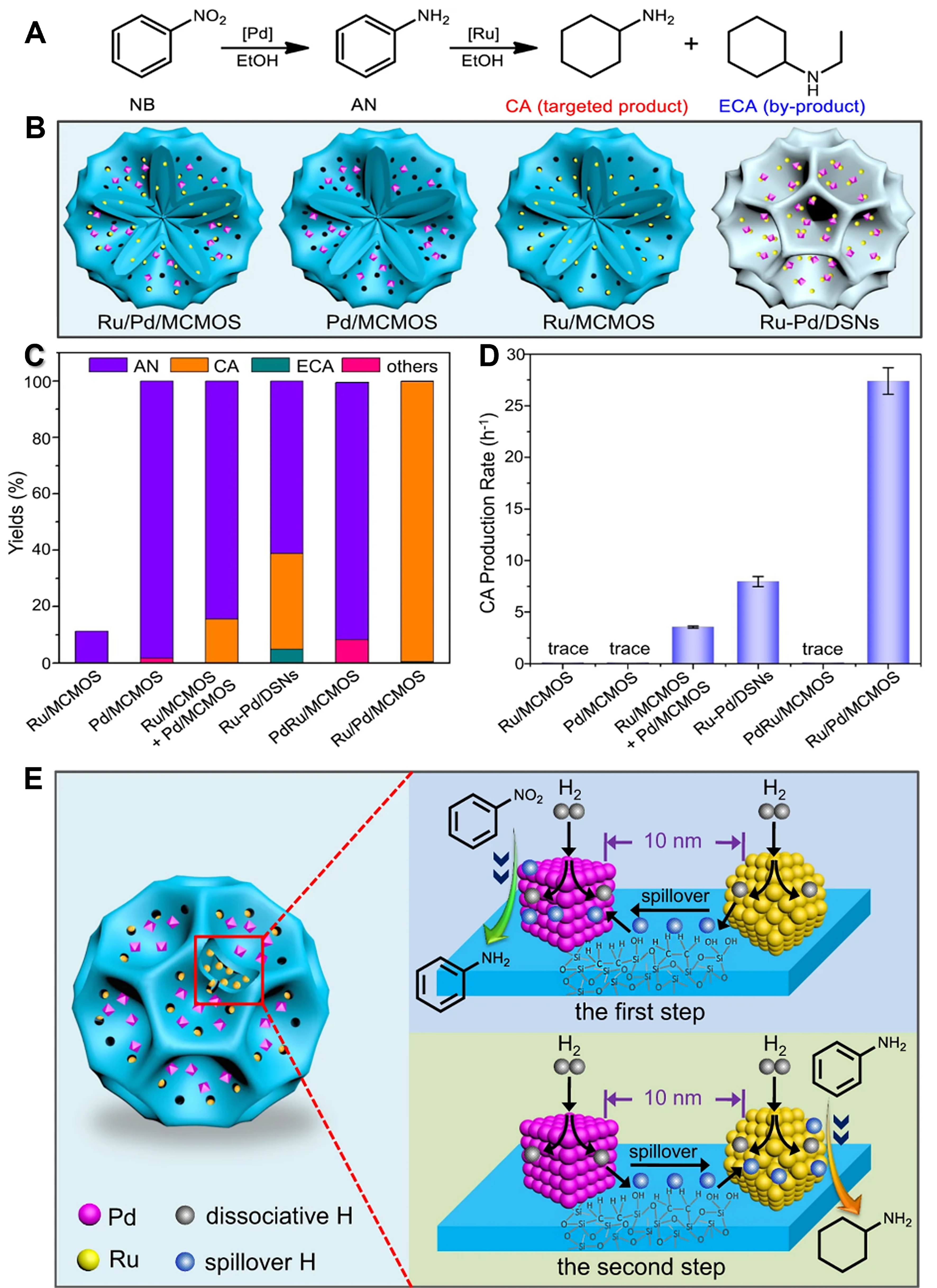

Zou et al. have reported a classic example[121]. Specifically, the Ru and Pd nanoparticles are successfully located in the internal nanocavity and surface groove of multi-compartment mesoporous silicone material (MCMOS), fabricating Ru/Pd/MCMOS bimetallic catalysts. For the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene (NB) to cyclohexylamine (CA) [Figure 12A-C], the Ru/Pd/MCMOS catalysts exhibited a 99.2% yield of CA after

Figure 12. (A) Reaction equation of nitrobenzene sequential hydrogenation; (B) Scheme of Ru/Pd/MCMOS, Pd/MCMOS, Ru/MCMOS and Ru-Pd/DSNs; (C) Product distributions of the nitrobenzene hydrogenation; (D) The cyclohexylamine production rates over various catalysts; (E) Scheme of nitrobenzene hydrogenation on the Ru/Pd/MCMOS catalysts. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[121]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. MCMOS: Mesoporous crystalline metal oxides; DSNs: dendritic silica nanoparticles.

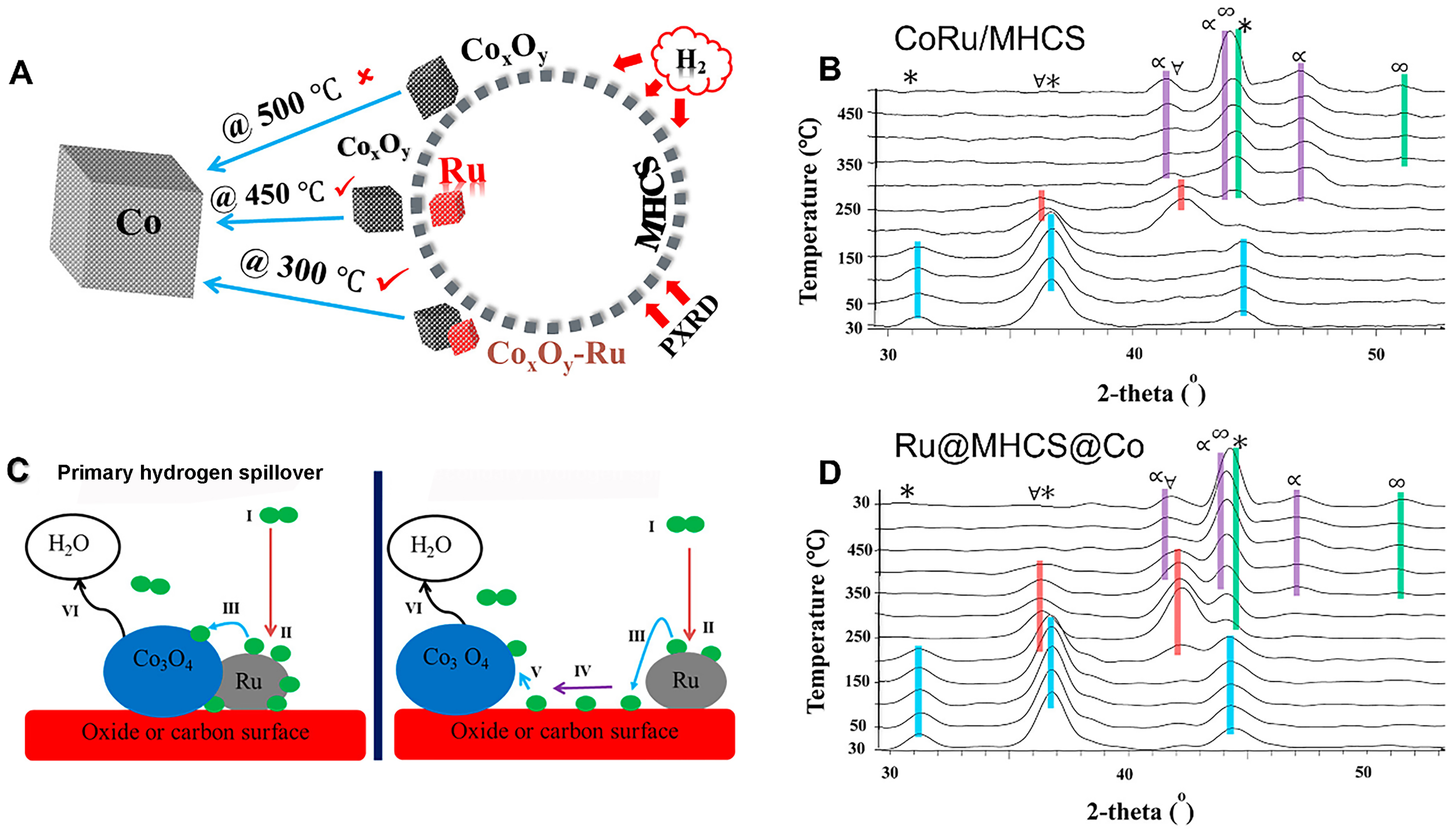

However, it should be noted that these successful cases do not necessarily imply universal applicability of bimetallic catalysts with the spatially separated active sites for all reactions. Phaahlamohlaka et al. loaded Ru and Co3O4 nanoparticles at different positions of porous carbon spheres [mesoporous hollow carbon spheres (MHCSs)] to prepare intimate CoRu/MHCS and separated Ru@MHCS@Co[124] [Figure 13A]. As depicted in Figure 13B, the primary hydrogen spillover occurs from Ru to Co metal active sites on CoRu/MHCS. In contrast, the Ru@MHCS@Co catalysts demonstrate a secondary hydrogen spillover where H* species transfer from Ru to Co through catalyst supports. In situ powder X-ray diffraction analysis revealed that the crystalline diffraction peaks of metallic Co emerged at 300 and 400 oC for CoRu/MHCS and Ru@MHCS@Co, respectively [Figure 13C and D]. This observation indicated the primary hydrogen spillover was more likely to reduce Co compared to the secondary hydrogen spillover. At 350 °C, the CoRu/MHCS catalysts, with primary spillover, yielded higher activity of Fischer-Tropsch synthesis than that of Ru@MHCS@Co with secondary hydrogen spillover. Therefore, this study provides novel insights into the role of spatial distance effect of bimetallic active sites.

Figure 13. (A) Temperature of CoxOy-Ru bimetallic intimacy for Co reduction. (B) The primary and secondary hydrogen spillover. In situ PXRD profiles of (C) CoRu/MHCS and (D) Ru@MHCS@Co under reduction conditions. [Co3O4 (*), CoO (∀), α-Co (∞), β-Co (α)]. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[124]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. PXRD: Powder X-ray diffraction; MHCS: mesoporous hollow carbon spheres.

CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOKS

The heterogeneous catalysts with bimetallic active sites have been demonstrated with impressive performance for selective hydrogenation. By precisely adjusting the spatial distance between bimetallic metal active sites, diverse synergistic effects arising from electronic and geometrical interactions can be achieved, resulting in the selective adsorption of reactants. Consequently, the bimetallic active sites exhibit enhanced selectivity for hydrogenation without compromising activity. Despite remarkable progress in constructing bimetallic active sites for selective hydrogenation, deficiencies at the atomic level and surface chemistry still exist. Potential research directions in this field may include the following areas:

(I) Atomic synthesis and regulation of bimetallic active sites. The crucial task is to spatially isolate bimetallic active sites to prevent mutual influence, while maintaining close proximity to minimize diffusion routes for intermediate products. Particularly, the precise construction of bimetallic active sites supported on the support surface remains a formidable challenge, necessitating the development of an effective and straightforward synthesis method. Methods such as ALD, colloidal synthesis, and molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) offer high levels of control but often require complex and costly equipment. Additionally, these methods need to be finely tuned to ensure reproducibility and scalability.

(II) Maintaining structural integrity. Ensuring the stability of bimetallic active sites during hydrogenation is challenging, especially under high temperatures and H2 pressures. The dynamic adsorption behaviors of intermediates lead to the migration or rearrangement of active sites, potentially disrupting the intended spatial separation and reducing catalytic efficiency. Therefore, it is imperative to select materials with high thermal and chemical stability. For instance, carbon materials, MOFs, or zeolites might serve as suitable supports; however, their selection depends on the specific reaction conditions and desired catalyst properties.

(III) Fine characterization of bimetallic active sites. To develop effective bimetallic catalysts, it is essential to characterize their structure at the atomic level. Sophisticated techniques such as X-ray absorption spectroscopy, high-resolution TEM and STM provide detailed information of structure and composition for bimetallic active sites. Meanwhile, revealing the microstructure of bimetallic catalysts in real-time reaction conditions is of paramount importance. In situ and operando characterization techniques, such as environmental TEM and operando spectra, allow researchers to observe catalyst structure in real time, providing valuable insights into the dynamic processes occurring during catalysis.

(IV) In-depth understanding of reaction mechanisms: Gaining a deep understanding of the reaction mechanisms for the catalysts with bimetallic active sites, including metal interactions, H2 dissociation and spillover of H*, and the adsorption and desorption of reactants, is crucial for optimizing catalyst structure and improving catalytic efficiency. Consequently, addressing the challenges associated with developing rational, efficient and stable catalysts featuring bimetallic active sites remains of utmost significance.

(V) Machine learning in the design of bimetallic active sites: Machine learning enables rapid screening of bimetallic catalyst combinations with potentially superior performance. By constructing machine learning models that incorporate key features such as adsorption energy, d-band center, and coordination number, it is possible to predict reactivity and selectivity. Through the application of those models, the structural design of catalysts can be systematically optimized, thereby enhancing their hydrogenation performance.

In summary, the catalytic performance of bimetallic catalysts for selective hydrogenation can be significantly enhanced by precise control over the spatial distance between bimetallic active sites. However, there are still numerous unexplored aspects, including precise compositional and structural control, atom-level characterization techniques, and a deeper understanding of the interactions and synergistic mechanisms. Overall, the bimetallic active sites provide a novel and promising approach towards highly effective selective hydrogenation. Future research endeavors are expected to focus on developing advanced synthetic methods, characterization techniques, and theoretical analysis to facilitate the design of more efficient and selective catalysts.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Manuscript preparation: Sun, Y.

Manuscript correction: Zhang, S.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022B1515020092) and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20220530161600002).

Conflict of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Zhang, L.; Zhou, M.; Wang, A.; Zhang, T. Selective hydrogenation over supported metal catalysts: from nanoparticles to single atoms. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 683-733.

2. Liu, L.; Corma, A. Metal catalysts for heterogeneous catalysis: from single atoms to nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4981-5079.

3. Alig, L.; Fritz, M.; Schneider, S. First-row transition metal (De)hydrogenation catalysis based on functional pincer ligands. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 2681-751.

4. Jing, W.; Shen, H.; Qin, R.; Wu, Q.; Liu, K.; Zheng, N. Surface and interface coordination chemistry learned from model heterogeneous metal nanocatalysts: from atomically dispersed catalysts to atomically precise clusters. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 5948-6002.

5. Meemken, F.; Baiker, A. Recent progress in heterogeneous asymmetric hydrogenation of C═O and C═C bonds on supported noble metal catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11522-69.

6. Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Ma, X.; Gong, J. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3703-27.

7. Xie, C.; Niu, Z.; Kim, D.; Li, M.; Yang, P. Surface and interface control in nanoparticle catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 1184-249.

8. Zhang, S.; Chang, C. R.; Huang, Z. Q.; et al. High catalytic activity and chemoselectivity of sub-nanometric Pd clusters on porous nanorods of CeO2 for hydrogenation of nitroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2629-37.

9. Li, M.; Sun, G.; Wang, Z.; et al. Structural design of single-atom catalysts for enhancing petrochemical catalytic reaction process. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2313661.

10. Friend, C. M.; Xu, B. Heterogeneous catalysis: a central science for a sustainable future. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 517-21.

11. Guo, J.; Chen, P. Interplay of alkali, transition metals, nitrogen, and hydrogen in ammonia synthesis and decomposition reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2434-44.

12. Luneau, M.; Lim, J. S.; Patel, D. A.; Sykes, E. C. H.; Friend, C. M.; Sautet, P. Guidelines to achieving high selectivity for the hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes with bimetallic and dilute alloy catalysts: a review. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12834-72.

13. Hu, J.; Cai, Y.; Xie, J.; Hou, D.; Yu, L.; Deng, D. Selectivity control in CO2 hydrogenation to one-carbon products. Chem 2024, 10, 1084-117.

14. Xu, M.; Hu, Z. Y.; Liang, X.; et al. Selective cleavage of α-olefins to produce acetylene and hydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 12850-6.

15. Lan, X.; Wang, T. Highly selective catalysts for the hydrogenation of unsaturated aldehydes: a review. ACS. Catal. 2020, 10, 2764-90.

16. Xue, F.; Li, Q.; Lv, M.; et al. Atomic three-dimensional investigations of Pd nanocatalysts for acetylene semi-hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 26728-35.

17. Jiang, L.; Liu, K.; Hung, S. F.; et al. Facet engineering accelerates spillover hydrogenation on highly diluted metal nanocatalysts. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 848-53.

18. Zhu, Q.; Lu, X.; Ji, S.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Z. Fully exposed cobalt nanoclusters anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon synthesized by a host-guest strategy for semi-hydrogenation of phenylacetylene. J. Catal. 2022, 405, 499-507.

19. Tao, F. F. Synthesis, catalysis, surface chemistry and structure of bimetallic nanocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7977-9.

20. Sudarsanam, P.; Zhong, R.; Van den Bosch, S.; Coman, S. M.; Parvulescu, V. I.; Sels, B. F. Functionalised heterogeneous catalysts for sustainable biomass valorisation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 8349-402.

21. Yamazaki, Y.; Miyaji, M.; Ishitani, O. Utilization of low-concentration CO2 with molecular catalysts assisted by CO2-capturing ability of catalysts, additives, or reaction media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 6640-60.

22. Lu, Z.; Li, T.; Mudshinge, S. R.; Xu, B.; Hammond, G. B. Optimization of catalysts and conditions in Gold(I) catalysis-counterion and additive effects.

23. Ferencz, Z.; Erdőhelyi, A.; Baán, K.; et al. Effects of support and Rh additive on Co-based catalysts in the ethanol steam reforming reaction. ACS. Catal. 2014, 4, 1205-18.

24. Liu, B.; Yao, H.; Song, W.; et al. Ligand-free noble metal nanocluster catalysts on carbon supports via “soft” nitriding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 4718-21.

25. Wang, S.; Yin, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. Glycerol hydrogenolysis to propylene glycol and ethylene glycol on zirconia supported noble metal catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2013, 3, 2112-21.

26. Shin, D.; Huang, R.; Jang, M. G.; et al. Role of an interface for hydrogen production reaction over size-controlled supported metal catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2022, 12, 8082-93.

27. Ferrin, P.; Simonetti, D.; Kandoi, S.; et al. Modeling ethanol decomposition on transition metals: a combined application of scaling and Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi relations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5809-15.

28. van Santen RA, Neurock M, Shetty SG. Reactivity theory of transition-metal surfaces: a Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi linear activation energy-free-energy analysis. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2005-48.

29. Cheng, Y. L.; Hsieh, C. T.; Ho, Y. S.; Shen, M. H.; Chao, T. H.; Cheng, M. J. Examination of the Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi relationship for the hydrogen evolution reaction on transition metals based on constant electrode potential density functional theory. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 2476-81.

30. Leduc, J.; Frank, M.; Jürgensen, L.; Graf, D.; Raauf, A.; Mathur, S. Chemistry of actinide centers in heterogeneous catalytic transformations of small molecules. ACS. Catal. 2019, 9, 4719-41.

31. Kattel, S.; Liu, P.; Chen, J. G. Tuning selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation reactions at the metal/oxide interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9739-54.

32. Zhang, S.; Xia, Z.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Qu, Y. Competitive adsorption on PtCo/CoBOx catalysts enables the selective hydrogen-reductive-imination of nitroarenes with aldehydes into imines. J. Catal. 2019, 374, 72-81.

33. Hess, F.; Smarsly, B. M.; Over, H. Catalytic stability studies employing dedicated model catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 380-9.

34. Su, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Theoretical approach to predict the stability of supported single-atom catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2019, 9, 3289-97.

35. Vilé, G.; Albani, D.; Almora‐barrios, N.; López, N.; Pérez‐ramírez, J. Advances in the design of nanostructured catalysts for selective hydrogenation. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 21-33.

36. Wu, D.; Baaziz, W.; Gu, B.; et al. Surface molecular imprinting over supported metal catalysts for size-dependent selective hydrogenation reactions. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 595-606.

37. Ren, X.; Dai, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q. Development of efficient catalysts for selective hydrogenation through multi-site division. Chinese. Journal. of. Catalysis. 2024, 62, 108-23.

38. Karim, W.; Spreafico, C.; Kleibert, A.; et al. Catalyst support effects on hydrogen spillover. Nature 2017, 541, 68-71.

39. Beaumont, S. K.; Alayoglu, S.; Specht, C.; et al. Combining in situ NEXAFS spectroscopy and CO₂ methanation kinetics to study Pt and Co nanoparticle catalysts reveals key insights into the role of platinum in promoted cobalt catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9898-901.

40. Zhang, T.; Walsh, A. G.; Yu, J.; Zhang, P. Single-atom alloy catalysts: structural analysis, electronic properties and catalytic activities. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 569-88.

41. Miura, H.; Endo, K.; Ogawa, R.; Shishido, T. Supported palladium-gold alloy catalysts for efficient and selective hydrosilylation under mild conditions with isolated single palladium atoms in alloy nanoparticles as the main active site. ACS. Catal. 2017, 7, 1543-53.

42. Huang, C.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, X.; et al. Deformable metal-organic framework nanosheets for heterogeneous catalytic reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9408-14.

43. Zhao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Greeley, J.; Savoie, B. M. Deep reaction network exploration at a heterogeneous catalytic interface. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4860.

44. Yan, H.; Lv, H.; Yi, H.; et al. Understanding the underlying mechanism of improved selectivity in pd1 single-atom catalyzed hydrogenation reaction. J. Catal. 2018, 366, 70-9.

45. Kuai, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; et al. Titania supported synergistic palladium single atoms and nanoparticles for room temperature ketone and aldehydes hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 48.

46. Zhong, W.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Enhanced activity of C2N-supported single Co atom catalyst by single atom promoter. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 7009-14.

47. Zhang, S.; Xia, Z.; Li, W.; et al. In-situ reconstruction of single-atom Pt on Co3O4 for hydrogenation. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 6507-11.

48. Gao, W.; Liu, S.; Sun, G.; Zhang, C.; Pan, Y. Single-atom catalysts for hydrogen activation. Small 2023, 19, e2300956.

49. Lim, K. R. G.; Kaiser, S. K.; Wu, H.; et al. Nanoparticle proximity controls selectivity in benzaldehyde hydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 172-84.

50. Tan, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Hydrogen spillover assisted by oxygenate molecules over nonreducible oxides. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1457.

51. Xiong, M.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, P.; et al. In situ tuning of electronic structure of catalysts using controllable hydrogen spillover for enhanced selectivity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4773.

52. Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. G.; Wei, J.; et al. Revealing the role of interfacial properties on catalytic behaviors by in situ surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10339-46.

53. Wang, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, G.; et al. Confinement-induced indium oxide nanolayers formed on oxide support for enhanced CO2 hydrogenation reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 5523-31.

54. Liu, X.; Ren, Y.; Wang, M.; Ren, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q. Cooperation of Pt and TiOx in the hydrogenation of nitrobenzothiazole. ACS. Catal. 2022, 12, 11369-79.

55. Wang, X.; Xiao, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, F. Heterolytic hydrogenation and H- migration-assisted hydrodeoxygenation reaction under mild conditions over Pt/TiO2-D. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 13800-13.

56. Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Kottwitz, M.; et al. Identifying dynamic structural changes of active sites in Pt-Ni bimetallic catalysts using multimodal approaches. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 4120-31.

57. Liu, L.; Corma, A. Bimetallic sites for catalysis: from binuclear metal sites to bimetallic nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4855-933.

58. Yin, H.; Zheng, L.; Fang, W.; et al. Nanometre-scale spectroscopic visualization of catalytic sites during a hydrogenation reaction on a Pd/Au bimetallic catalyst. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 834-42.

60. Zhang, S.; Xia, Z.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qu, Y. Spatial intimacy of binary active-sites for selective sequential hydrogenation-condensation of nitriles into secondary imines. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3382.

61. Zhang, S.; Qu, Y. Spatially isolated dual-active sites enabling selective hydrogenation. Cell. Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 101793.

62. Chen, X.; Shi, C.; Liang, C. Highly selective catalysts for the hydrogenation of alkynols: a review. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 2105-21.

63. Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Guo, C.; et al. Solvent-free selective hydrogenation of nitroaromatics to azoxy compounds over Co single atoms decorated on Nb2O5 nanomeshes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3195.

64. Navarro-Jaén, S.; Virginie, M.; Bonin, J.; Robert, M.; Wojcieszak, R.; Khodakov, A. Y. Highlights and challenges in the selective reduction of carbon dioxide to methanol. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 564-79.

65. Ren, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wei, M. Recent advances on heterogeneous non-noble metal catalysts toward selective hydrogenation reactions. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 8902-24.

66. Wei, Z.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Datye, A. K.; Wang, Y. Bimetallic catalysts for hydrogen generation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7994-8008.

67. Sankar, M.; Dimitratos, N.; Miedziak, P. J.; Wells, P. P.; Kiely, C. J.; Hutchings, G. J. Designing bimetallic catalysts for a green and sustainable future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 8099-139.

68. Dong, C.; Mu, R.; Li, R.; et al. Disentangling local interfacial confinement and remote spillover effects in oxide-oxide interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 17056-65.

69. Calle-Vallejo, F.; Tymoczko, J.; Colic, V.; et al. Finding optimal surface sites on heterogeneous catalysts by counting nearest neighbors. Science 2015, 350, 185-9.

70. Jiao, F.; Guo, H.; Chai, Y.; Awala, H.; Mintova, S.; Liu, C. Synergy between a sulfur-tolerant Pt/Al2O3@sodalite core-shell catalyst and a CoMo/Al2O3 catalyst. J. Catal. 2018, 368, 89-97.

71. Zhang, Q.; Lee, I.; Joo, J. B.; Zaera, F.; Yin, Y. Core-shell nanostructured catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1816-24.

72. Choi, B.; Song, J.; Song, M.; et al. Core-shell engineering of Pd-Ag bimetallic catalysts for efficient hydrogen production from formic acid decomposition. ACS. Catal. 2019, 9, 819-26.

73. Pu, J.; Nishikado, K.; Wang, N.; Nguyen, T. T.; Maki, T.; Qian, E. W. Core-shell nickel catalysts for the steam reforming of acetic acid. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2018, 224, 69-79.

74. Hannagan, R. T.; Giannakakis, G.; Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M.; Sykes, E. C. H. Single-atom alloy catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12044-88.

75. Meng, G.; Sun, J.; Tao, L.; et al. Ru1Con single-atom alloy for enhancing fischer-tropsch synthesis. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 1886-96.

76. Feng, Q.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. Isolated single-atom pd sites in intermetallic nanostructures: high catalytic selectivity for semihydrogenation of alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7294-301.

77. Marcinkowski, M. D.; Darby, M. T.; Liu, J.; et al. Pt/Cu single-atom alloys as coke-resistant catalysts for efficient C-H activation. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 325-32.

78. Gao, Z.; Wang, G.; Lei, T.; et al. Enhanced hydrogen generation by reverse spillover effects over bicomponent catalysts. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 118.

79. Wang, M.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, B.; et al. Ultrathin coating of confined Pt nanocatalysts by atomic layer deposition for enhanced catalytic performance in hydrogenation reactions. Chemistry 2016, 22, 8438-43.

80. Zhang, S.; Gan, J.; Xia, Z.; et al. Dual-active-sites design of Co@C catalysts for ultrahigh selective hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes. Chem 2020, 6, 2994-3006.

81. Sun, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhang, S. Breaking the H2 pressure dependence in hydrogenation through interfacial *H reservoirs on Cu-WO3 catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2025, 15, 14331-40.

82. Zhang, Y.; Lewis, R. J.; Li, Z.; He, X.; Ji, H.; Hutchings, G. J. Direct synthesis of H2O2 by spatially separate hydrogen and oxygen activation sites on tailored Pt-Au catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2026, 65, e21118.

83. Sui, C.; Dong, W.; Wang, M.; et al. Fully exposed Cu clusters with Ru single atoms synergy for high-performance acetylene semihydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 19808-16.

84. Mu, C.; Lv, C.; Meng, X.; Sun, J.; Tong, Z.; Huang, K. In situ characterization techniques applied in photocatalysis: a review. Adv. Materials. Inter. 2023, 10, 2201842.

85. Li, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, B. In situ/operando techniques for characterization of single-atom catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2019, 9, 2521-31.

86. Tran, L.; Haase, M. F. Templating interfacial nanoparticle assemblies via in situ techniques. Langmuir 2019, 35, 8584-602.

87. Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Ji, R.; et al. In situ characterization techniques for electrochemical nitrogen reduction reaction. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 20934-56.

88. Song, X.; Xu, L.; Sun, X.; Han, B. In situ/operando characterization techniques for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Sci. China. Chem. 2023, 66, 315-23.

89. He, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, L. In‐situ transmission electron microscope techniques for heterogeneous catalysis. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 1853-72.

90. Li, X.; Sun, M.; Shan, C.; Chen, Q.; Wei, X. Mechanical properties of 2D materials studied by in situ microscopy techniques. Adv. Materials. Inter. 2018, 5, 1701246.

91. Guan, Q.; Zhu, C.; Lin, Y.; et al. Bimetallic monolayer catalyst breaks the activity-selectivity trade-off on metal particle size for efficient chemoselective hydrogenations. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 840-9.

92. Wang, S.; Lv, Y.; Ren, J.; et al. Ultrahigh selective hydrogenation of furfural enabled by modularizing hydrogen dissociation and substrate activation. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 8720-30.

93. Zhu, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, F.; Luo, J.; Lu, J.; Li, W. X. Molecule saturation boosts acetylene semihydrogenation activity and selectivity on a core-shell ruthenium@palladium catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202300110.

94. Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Lu, J. Ultra-thin nickel oxide overcoating of noble metal catalysts for directing selective hydrogenation of nitriles to secondary amines. Catalysis. Today. 2023, 410, 253-63.

95. Liu, W.; Feng, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Highly-efficient RuNi single-atom alloy catalysts toward chemoselective hydrogenation of nitroarenes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3188.

96. Liu, F.; Xia, Y.; Xu, W.; et al. Integration of bimetallic electronic synergy with oxide site isolation improves the selective hydrogenation of acetylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 19324-30.

97. Zhang, X.; Cui, G.; Feng, H.; et al. Platinum-copper single atom alloy catalysts with high performance towards glycerol hydrogenolysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5812.

98. Wang, H.; Luo, Q.; Liu, W.; et al. Quasi Pd1Ni single-atom surface alloy catalyst enables hydrogenation of nitriles to secondary amines. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4998.

99. Giulimondi, V.; Mitchell, S.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Challenges and opportunities in engineering the electronic structure of single-atom catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 2981-97.

100. van der Hoeven, J. E. S.; Jelic, J.; Olthof, L. A.; et al. Unlocking synergy in bimetallic catalysts by core-shell design. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 1216-20.

101. Zhang, X.; Sun, Z.; Jin, R.; et al. Conjugated dual size effect of core-shell particles synergizes bimetallic catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 530.

102. Das, S.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Gong, J.; et al. Core-shell structured catalysts for thermocatalytic, photocatalytic, and electrocatalytic conversion of CO2. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2937-3004.

103. Su, J.; Ji, Y.; Geng, S.; et al. Core-shell design of metastable phase catalyst enables highly-performance selective hydrogenation. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2308839.

104. Fang, J.; Liu, Q.; Kang, X.; Chen, S. Selective hydrogenation of 4-nitrostyrene to 4-nitroethylbenzene catalyzed by Pd@Ru core-shell nanocubes. Rare. Met. 2022, 41, 1189-94.

105. Wang, S.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Design of Pt@Sn core-shell nanocatalysts for highly selective hydrogenation of cinnamaldehyde to prepare cinnamyl alcohol. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 151019.

106. Islam, M. J.; Granollers, M. M.; Osatiashtiani, A.; et al. PdCu single atom alloys supported on alumina for the selective hydrogenation of furfural. Appl. Catal. B. 2021, 299, 120652.

107. Kyriakou, G.; Boucher, M. B.; Jewell, A. D.; et al. Isolated metal atom geometries as a strategy for selective heterogeneous hydrogenations. Science 2012, 335, 1209-12.

108. Yang, X. F.; Wang, A.; Qiao, B.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T. Single-atom catalysts: a new frontier in heterogeneous catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1740-8.

109. Boyes, E. D.; LaGrow, A. P.; Ward, M. R.; Mitchell, R. W.; Gai, P. L. Single atom dynamics in chemical reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 390-9.

110. Liu, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, J. Theoretical understanding of the stability of single-atom catalysts. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 638-41.

111. Aich, P.; Wei, H.; Basan, B.; et al. Single-atom alloy Pd-Ag catalyst for selective hydrogenation of acrolein. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015, 119, 18140-8.

112. Guan, S.; Yuan, Z.; Zhuang, Z.; et al. Why do single-atom alloys catalysts outperform both single-atom catalysts and nanocatalysts on MXene? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202316550.

113. Ngan, H. T.; Sautet, P. Tuning the hydrogenation selectivity of an unsaturated aldehyde via single-atom alloy catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 2556-67.

114. Zhou, C.; Zhao, J. Y.; Liu, P. F.; et al. Towards the object-oriented design of active hydrogen evolution catalysts on single-atom alloys. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 10634-42.

115. Qiao, M.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Selective hydrogenation catalysis enabled by nanoscale galvanic reactions. Chem 2024, 10, 3385-95.

116. Zhao, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; et al. Pt/Fe-TiO2-catalyzed selective carbonyl hydrogenation: Fe-promoted hydrogen spillover. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 4478-88.

117. Li, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Cao, D.; Cheng, D. Constructing a highly active Pd atomically dispersed catalyst for cinnamaldehyde hydrogenation: synergistic catalysis between Pd-N3 single atoms and fully exposed Pd clusters. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 2369-79.

118. Wang, S.; Lv, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Insights into the active sites of dual‐zone synergistic catalysts for semi‐hydrogenation under hydrogen spillover. AIChE. Journal. 2023, 69, e17886.

119. Deng, P.; Duan, J.; Liu, F.; et al. Atomic insights into synergistic nitroarene hydrogenation over nanodiamond-supported Pt1-Fe1 dual-single-atom catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202307853.

120. Shen, Q.; Jin, H.; Li, P.; et al. Breaking the activity limitation of iridium single-atom catalyst in hydrogenation of quinoline with synergistic nanoparticles catalysis. Nano. Res. 2022, 15, 5024-31.

121. Zou, H.; Dai, J.; Suo, J.; et al. Dual metal nanoparticles within multicompartmentalized mesoporous organosilicas for efficient sequential hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4968.

122. Fu, J.; Dong, J.; Si, R.; et al. Synergistic effects for enhanced catalysis in a dual single-atom catalyst. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 1952-61.

123. Zhang, J.; Gao, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Origin of synergistic effects in bicomponent cobalt oxide-platinum catalysts for selective hydrogenation reaction. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4166.

124. Phaahlamohlaka, T. N.; Kumi, D. O.; Dlamini, M. W.; et al. Effects of Co and Ru intimacy in Fischer-Tropsch catalysts using hollow carbon sphere supports: assessment of the hydrogen spillover processes. ACS. Catal. 2017, 7, 1568-78.

125. Conner, W. C.; Falconer, J. L. Spillover in heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 759-88.

126. Im, J.; Shin, H.; Jang, H.; Kim, H.; Choi, M. Maximizing the catalytic function of hydrogen spillover in platinum-encapsulated aluminosilicates with controlled nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3370.

127. Xiong, M.; Gao, Z.; Qin, Y. Spillover in heterogeneous catalysis: new insights and opportunities. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 3159-72.

128. Zhang, S.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, M.; et al. Boosting selective hydrogenation through hydrogen spillover on supported-metal catalysts at room temperature. Appl. Catal. B. 2021, 297, 120418.

129. Liu, K.; Yan, P.; Jiang, H.; et al. Silver initiated hydrogen spillover on anatase TiO2 creates active sites for selective hydrodeoxygenation of guaiacol. J. Catal. 2019, 369, 396-404.

130. Shun, K.; Mori, K.; Masuda, S.; et al. Revealing hydrogen spillover pathways in reducible metal oxides. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8137-47.

131. Sun, Y.; Du, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S. Hydrogen spillover-accelerated selective hydrogenation on WO3 with ppm-level Pd. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 20474-82.

132. Wei, J.; Qin, S. N.; Liu, J. L.; et al. In situ raman monitoring and manipulating of interfacial hydrogen spillover by precise fabrication of Au/TiO2/Pt sandwich structures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 10343-7.

133. Li, W.; Gan, J.; Liu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qu, Y. Platinum and frustrated lewis pairs on ceria as dual-active sites for efficient reverse water-gas shift reaction at low temperatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202305661.

134. Beaumont, S. K.; Alayoglu, S.; Specht, C.; Kruse, N.; Somorjai, G. A. A nanoscale demonstration of hydrogen atom spillover and surface diffusion across silica using the kinetics of CO2 methanation catalyzed on spatially separate Pt and Co nanoparticles. Nano. Lett. 2014, 14, 4792-6.

135. Wang, S.; Zhao, Z. J.; Chang, X.; et al. Activation and spillover of hydrogen on sub-1 nm palladium nanoclusters confined within sodalite zeolite for the semi-hydrogenation of alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 7668-72.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].