Soil organic matter mineralization rate and metal contamination of the main soil types in central part of Yamal region (West Siberia, Russia)

Abstract

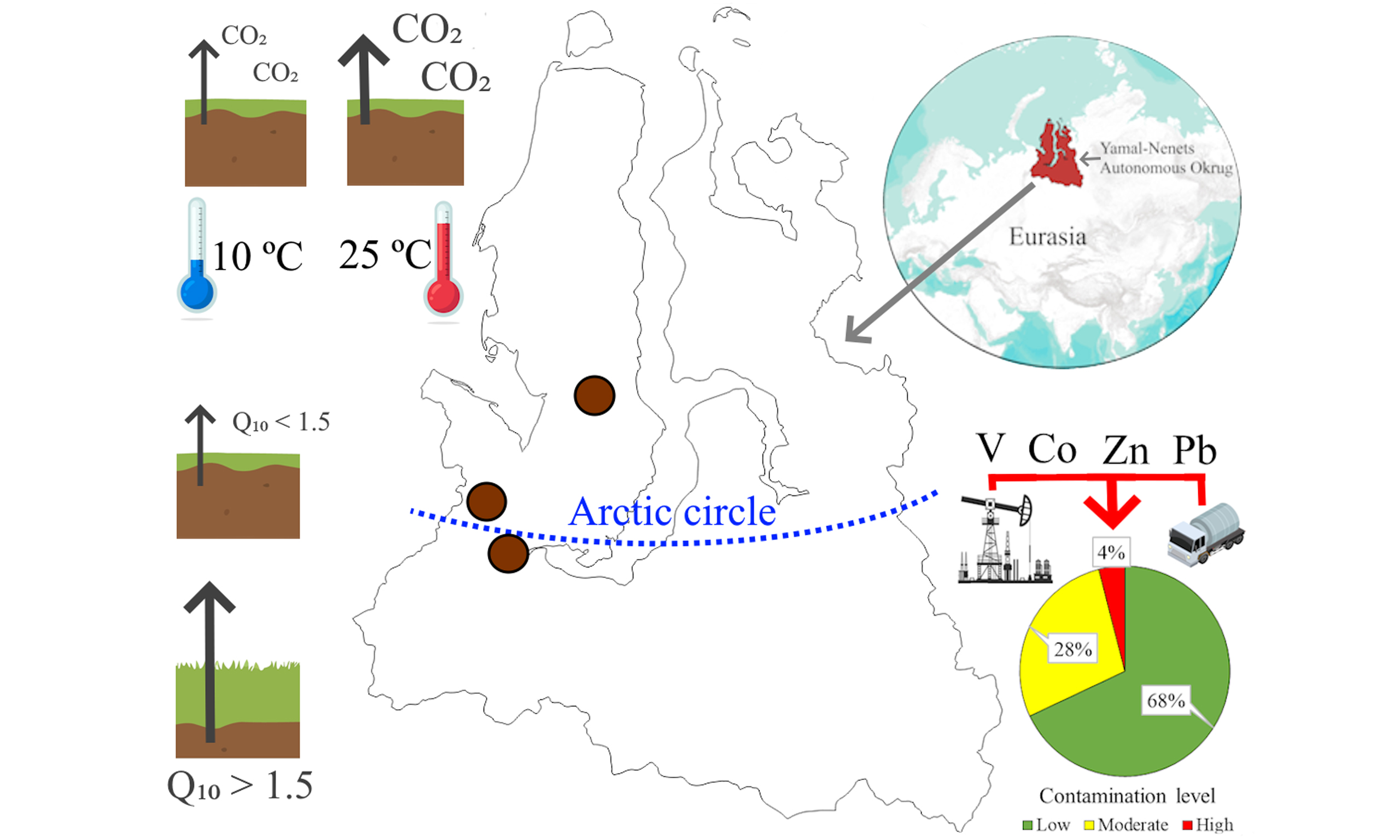

This study investigates soil organic matter (SOM) mineralization rates and ecotoxicological state of major soil types in the Yamal region of West Siberia, Russia. Soil samples were collected from three sites: Lower Ob Basin, Rai-Iz mountain massif (Polar Urals), and southern Yamal Peninsula. SOM mineralization was assessed through 90-day incubation experiments at 10 and 25 °C, determining potentially mineralizable organic carbon (PMC) and basal respiration rates. Ecotoxicological assessment included analyses of heavy metals (Sr, Pb, Zn, Co, Ni, Cr, V, As, MnO) and the calculation of the total soil pollution index (Zc). The content of PMC varied from 279.50 mg/kg to 37,254.15 mg/kg, constituting 11.59%-2.74% of total soil organic carbon at 25 °C. Maximum mineralization occurred in upper organogenic horizons of Histosols and Podzols, while mineral and cryoturbated horizons showed lower rates. Temperature dependence was evident, with higher mineralization rates at 25 °C in most samples, though some mineral horizons showed the opposite pattern. Regarding ecotoxicological state, 32 of 47 soil samples showed low (acceptable) contamination levels (Zc < 16), 13 samples demonstrated moderate (moderately hazardous) levels, and only 2 samples showed high (hazardous) contamination. Priority pollutants were lead (Pb), vanadium (V), and cobalt (Co), with spatial patterns indicating vehicle emissions as a major contamination source near transport arteries. The radial differentiation coefficient revealed distinct redistribution patterns of elements across soil profiles. Overall, the soil cover of northern Western Siberia exhibits generally low anthropogenic contamination, though moderate to high contamination levels were found in areas associated with oil and gas production facilities and roadside territories. The integrative analysis suggests that areas of high anthropogenic pressure coincide with significant carbon stocks, warranting further investigation into the interplay between pollution and carbon cycle feedbacks.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The soil organic matter (SOM) pool is the largest carbon reservoir in terrestrial ecosystems and plays a crucial role in the global carbon cycle. SOM is approximately 3.3 times larger than the atmospheric carbon pool and 4.5 times larger than the biomass carbon pool of terrestrial ecosystems[1]. Even minor changes in its dynamics can significantly influence the concentration of climate-active gases in the atmosphere. In Russia alone, the total annual CO2 emission into the atmosphere is estimated at approximately 2,500 million tons of CO2-equivalents[2], which corresponds to about 681 million tons of carbon (681 Mt C)[3].

The increasing concentration of climate-active gases in the atmosphere will further exacerbate climate warming. In turn, climate warming may promote the release of soil carbon, creating a positive feedback loop with global warming[4]. Thus, SOM distribution and transformation have a major impact on the global carbon balance and climate change. In this context, soils of the Polar Regions gain particular importance, as they contain immense stocks of organic carbon in a sequestered form. Occupying about 15% of the total land area, cryogenic soils contain, according to various estimates, 30-50% of global SOM stocks[5,6]. Arctic climates facilitated the long-term sequestration of organic matter. Soil carbon exists predominantly in an organic form as part of SOM, and partially in an inorganic form as carbonates, constituting a complex multifunctional system within the conglomerate of soil mineral particles[7]. SOM is a system ranging from coarse, solid organic particles 2-0.053 mm in size (Particulate Organic Matter, POM) to fine organic substances associated with minerals smaller than 0.053 mm (Mineral-Associated Organic Matter, MAOM)[8]. SOM stocks and resistance to biodegradation depend on the combination of external and internal factors, which determine not only its decomposition but also its stabilization[9]. The key factors influencing SOM stability are vegetation type and climate[10].

Currently, climate change in Polar Regions is exhibiting a faster warming trend than elsewhere in the world[11]. The rate of warming in the Arctic is 2-2.5 times higher than the global average[12]. Arctic temperature increases cause permafrost degradation, making large volumes of previously sequestered organic matter vulnerable to microbial decomposition[13]. This context places special emphasis on quantifying carbon stocks in permafrost soils and carbon emissions from them. Studies conducted on Arctic soils during freeze-thaw cycles show that CO2 emissions intensify after each thaw. For example, the ratio of the average CO2 production rate before freezing to the average CO2 production rate after thawing ranged from 0.85 to 0.89 for tundra soil, and the specific CO2-C production rate (CO2-C/SOM) was 0.16 in the study by Ludwig (2006)[14,15]. Thus, permafrost degradation accompanied by the mobilization of previously sequestered SOM can lead to its rapid mineralization and the release of climate-active gases[15]. Directly or indirectly related to the stocks and quality of SOM are soil resistance to external influences, the rate of biogenic element cycling and nutrient balance, the sorption capacity of the soil absorbing complex, and the efficiency of its remediation, the structure and biodiversity of the microbial communities[16]. The most sensitive characteristics of SOM are the kinetic parameters of its decomposition and mineralization[16]. Therefore, assessing SOM mineralization across different soil types in the polar regions and collecting data are crucial for improving forecasts of changes in biogeochemical cycles within polar ecosystems undergoing rapid transformation.

Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (YaNAO) encompasses a vast territory (over 750,000 km2), spanning subarctic and arctic landscapes, including tundra, forest-tundra, northern taiga, and mountain zones in the northern part of Western Siberia within the permafrost zone[17]. The Yamal region represents a critical study area for investigating SOM mineralization processes in the context of climate warming as it combines a diversity of cryogenic soil types (Histosols, Gleysols, Cryosols), climatic trends (intensive warming is observed in Western Siberia during spring: +0.78 °C per ten years)[18], and intensive anthropogenic impact (oil and gas industry). The latter also affects the ecotoxicological condition of the soils of the region. The intensification of anthropogenic pressure on YaNAO soils due to hydrocarbon extraction, mining and the development of associated infrastructure (ports, pipelines, roads, etc.) may lead to the accumulation of pollutants, including heavy metals, in the environment. In Arctic environments, permafrost governs cryogenic mass transfer and the accumulation of substances above permafrost[19], which is reflected in the vertical distribution of pollutants[20]. The area of the present study was previously investigated very little for background concentrations of chemical elements in soils; therefore, establishing background concentrations of chemical elements in soils is relevant for YaNAO[21].

Although SOM mineralization and the ecotoxicological state of soils are often studied separately, they are intrinsically linked in the context of anthropogenic impacts on Arctic ecosystems. Heavy metals can significantly alter the structure and function of microbial communities[22,23], either stimulating or inhibiting their activity depending on the element and its concentration. Since microbial communities are the primary drivers of SOM decomposition[24], a combined assessment of both labile carbon pools and contaminant load is essential for a holistic understanding of the stability of the vast carbon stocks in permafrost-affected soils[25]. This study uniquely integrates these two aspects to investigate whether anthropogenic pollution in the Yamal region acts as an additional factor that could accelerate or decelerate the mobilization of soil carbon into the atmosphere. The research objectives are to: (1) assess the impact of temperature on SOM mineralization and carbon release in cryogenic soils under climate change scenario conditions; (2) evaluate the ecotoxicological status of soils in the Yamal region by determining levels of heavy metal contamination (Sr, Pb, Zn, Co, Ni, Cr, V, As, Mn) and calculating the soil pollution index (Zc); (3) investigate the vertical distribution of chemical elements in soil profiles to understand their redistribution processes; and (4) determine the kinetic parameters of SOM mineralization for biogeochemical modeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and study area description

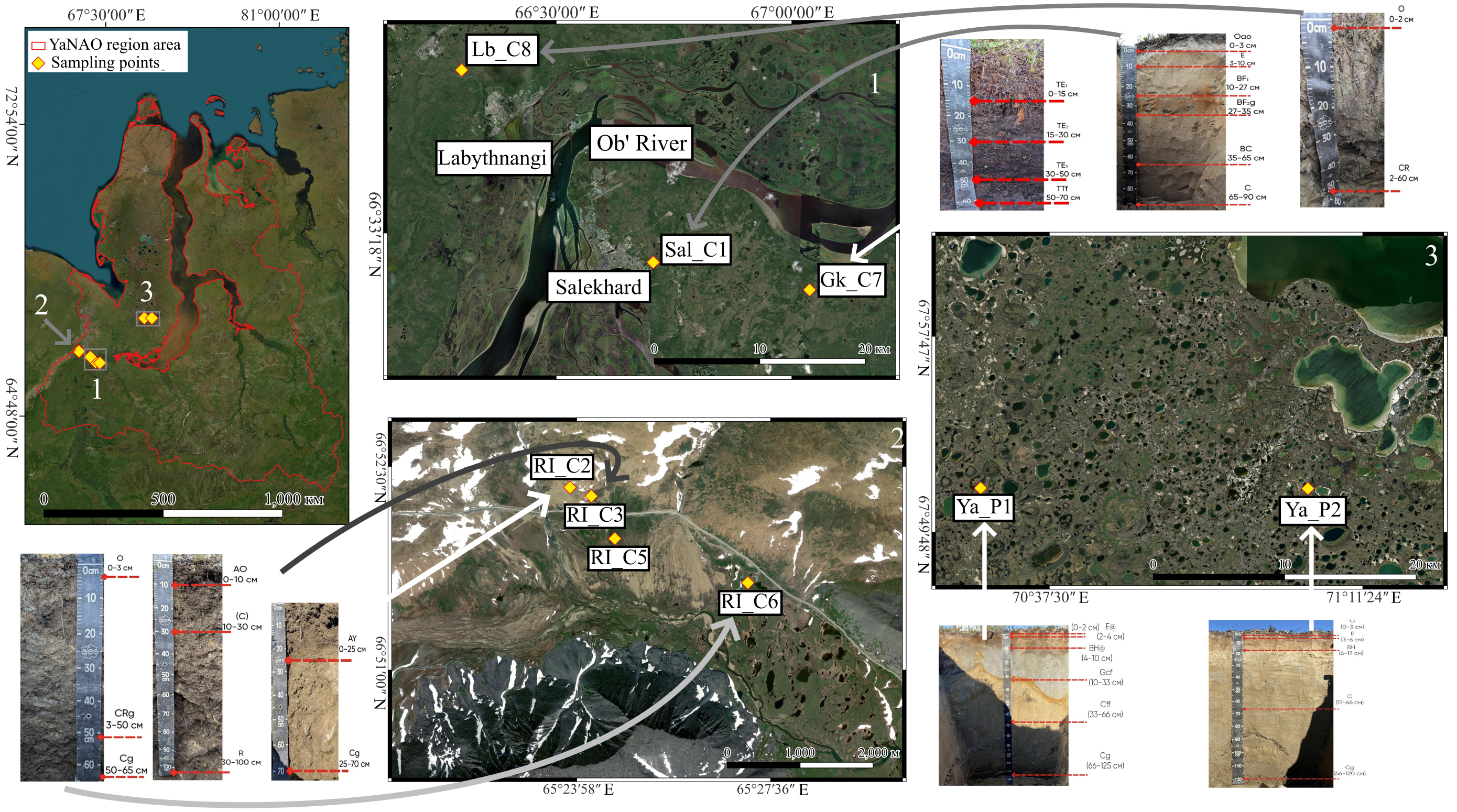

The research was conducted in the YaNAO at three sites: the Lower Ob Basin, the Rai-Iz mountain massif, and the southern part of the Yamal Peninsula [Figure 1]. The fieldwork was carried out in August 2024. Soil samples were taken from each sampling point at the fixed depths that correspond to specific soil layers in triplicate from different sides of the soil profile using a steel shovel, dried on site, and then transported to St. Petersburg in sterile sealed plastic bags for further analysis.

Figure 1. Location of the study areas and soil sampling sites. Satellite imagery source: Esri Satellite with radiometric calibration and atmospheric correction (Sentinel-2, resolution 10 m, acquisition date August 2025. https://browser.dataspace.copernicus.eu). The map border of the YaNAO region is taken from the National Atlas of Russia published by Roskartographia (Russian Cartography Service) in 2008 (https://nationalatlas.ru/tom3/)[26]. Satellite images were modified using QGIS 3.36.1 open-source software in order to create maps of the study areas and further merged with original images of soil profiles using Paint.NET 5.1.9 open-source software. YaNAO: Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug.

The first study site was located in the northern part of the Lower Ob Basin, near the cities of Salekhard and Labytnangi. The mean annual air temperature of the area is approximately -5.1 °C, and the average annual precipitation ranges from 500 mm. The parent materials are polygenetic and polydisperse Neopleistocene-Holocene sedimentary deposits. The vegetation cover is dominated by Betula nana, Vaccinium uliginosum, Andromeda polifolia, shrubs of the genus Salix, and lichens of the genera Cladonia and Cetraria. The first key site (Sal_C1) was located southwest of Salekhard in the area of a polygonal forest-tundra plain. On this site, Albic Podzol is formed. At the second key site (Gk_C7), eutrophic Cryic Histosol was identified, containing coal inclusions that indicate the involvement of pyrogenic processes in the formation of these soils. In the foothill forest-tundra near Labytnangi, on a microelevation within a wetland landscape, Histic Cryosol (Lb_C8) was identified on medium-loamy boulder and pebbly deposits[27]. The soils exhibit thixotropy, lacking distinct structural aggregates, while possessing a characteristic tangled-layered structure[28].

The second research site is located in the Rai-Iz mountain massif in the Polar Urals. According to data from the “Rai-Iz” meteorological station, the mean annual air temperature is -8.2 °C, and annual precipitation ranges from 700 mm to 1,000 mm. Lichens and dwarf shrubs (Betula nana, Andromeda polifolia) predominantly represent the ground cover. Among boulders and stones of bedrock, outcrops grow Dryas octopetala, Salix polaris and Salix arctica, as well as Silene acaulis, Dianthus repens and Saxifraga spinulosa. The first key site (RI_C5, RI_C6) was located on a gentle slope, where Skeletic Cryosol and Histic Cryosol develop. A high proportion of gravel material is observed, as well as large angular rock fragments. On slopes with a steeper gradient and increased accumulation of colluvium deposits, a Skeletic Leptosol (RI_C3) with an undifferentiated soil profile is formed. The fine earth is colored dark brown. The soil profile is permeated with plant roots down to a depth of 40 cm. The stoniness of the profile is 70%-80%, with a predominance of large, angular bedrock blocks. The next key site (RI_C2) is located at an altitude of 407 meters above sea level, where Skeletic Cambisol forms on rocky debris from ultramafic rocks. The soil profile is characterized by abundant boulders, with stoniness accounting for about 60%.

The third study site is located in the southern part of the Yamal Peninsula. The mean annual precipitation in the area ranges from 230 mm to 270 mm, and the average annual temperature is -10 °C[29]. The projective cover of the vegetation is predominantly composed of lichens of genera Cladonia and Cetraria, as well as dwarf shrubs Vaccinium uliginosum, Empetrum nigrum and Betula nana. The soils are formed on layered sandy gleyed deposits. The first key site (Ya_P1) is located in the subzone of southern hypoarctic tundra near lakes Ngevadyodato and Yakhadymalto, where Turbic Podzol is developing. The profile exhibits distinct signs of cryoturbation, which are represented by a whirl-like pattern and the protrusion of the lower C horizon into the upper gley horizon. The second key site (Ya_P2) is located next to the Yaroto lakes, where Entic Podzol is forming. All sampling locations are generalized in Table 1.

Characteristics of sampling landscapes and soil classification

| Site code | Coordinates | Landscape | Soil (WRB, 2022) |

| Sal_C1 | 66.530222, 66.705972 | Plain herb-moss- draft shrub forest-tundra | Albic Podzol |

| RI_C2 | 66.872411, 65.397275 | Mountain draft shrub-herb tundra | Skeletic Cambisol |

| RI_C3 | 66.871350, 65.403931 | Mountain lichen-shrub-herb tundra | Skeletic Leptosol |

| RI_C5 | 66.866138, 65.411269 | Intermountain moss-herb-shrub tundra | Skeletic Cryosol |

| RI_C6 | 66.860714, 65.452812 | Intermountain draft shrub-herb-moss tundra | Histic Cryosol |

| Gk_C7 | 66.506902, 67.037746 | Plain moss-draft shrub-shrub forest-tundra | Cryic Histosol |

| Lb_C8 | 66.692222, 66.299444 | Polygonal tundra | Histic Cryosol |

| Ya_P1 | 67.860090, 70.501160 | Plain polygonal dwarf shrub-lichen tundra | Turbic Podzol |

| Ya_P2 | 67.859780, 71.091050 | Plain polygonal dwarf shrub-lichen tundra | Entic Podzol |

Laboratory and data processing

Laboratory analyses included the determination of actual (pH H2O) and exchangeable (pH KCl) acidity by the potentiometric method[30,31]. Particle size distribution was defined by the method used by Kachinsky[32]. Total carbon content was measured by high-temperature dry combustion on a LECO TruSpec MICRO elemental analyzer (model 630-300-200; St. Joseph, MI, USA) at the “Chemical Analysis and Materials Research Center” of Saint Petersburg State University (SPbU) Research Park, according to the FAO methodology[33]. The studied soils contained no carbonates; therefore, the total carbon content was equated to the soil organic carbon (SOC). The results of the basic physicochemical analyses for all soil horizons are given in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Potentially mineralizable organic carbon (PMC) was determined in topsoil horizons only (mostly 0-10 cm), as they represent the most biologically active part of the soil profile, using the biokinetic fractionation method[34]. For this purpose, 10 g of air-dry soil were placed in 50 mL glass beakers and moistened to 25% moisture with distilled water. Subsequently, the samples were pre-incubated in slightly open plastic containers in a dark place at 10 and 25 °C for 7 days. These temperatures were chosen because 10 °C represents the mean air temperature in July at the YaNAO region, the most biologically productive month, while 25 °C represents peak temperatures that have occurred more frequently in recent years due to climate change[35,36]. After pre-incubation, a beaker with 10 mL of 0.1 mol/L NaOH was also placed inside the airtight plastic container to absorb the CO2 released during carbon mineralization. Three containers with NaOH solution without soil were used as blank samples. Thereafter, all samples were incubated at 25 and 10 °C for 90 days; these temperatures correspond to those of the ambient air during the summer months at the study areas and are also comparable to the duration of the frost-free period. During the incubation process, the NaOH solution was periodically changed at 12, 36, and 84 h, and then on days 6, 13, 20, 27, 34, 43, 50, 63, 77, and 91 from the start of incubation. A standardized 0.05 mol/L HCl solution was used to titrate the NaOH solution.

The rate of С-СО2 release (μg C-CO2/g soil/h) during the exposure period was calculated according to[37]:

where SMR is the rate of С-СО2 release; CHCl is the concentration of the standard HCl solution used for titration (mol/L); V0 is the volume of HCl titrated in the blank sample (mL); V is the volume of HCl titrated in the flasks containing soil (mL); t is the incubation time (h); and m is the mass of the soil (g).

The cumulative C-CO2 production (mg C-CO2/g) was determined by summing the amount of carbon released at each measurement interval with the sum of the previous intervals. To calculate the potentially mineralizable organic carbon (PMC) content, the cumulative C-CO2 production curve over the entire incubation period was approximated using a single first-order kinetic model according to[34]:

where Ct is the cumulative content of С-СО2 (μg C-CO2/g soil) for the time t (days); C0 is the content of PMC of SOM (μg C-CO2/g soil); k is the constant for the rate of mineralization of the SOM (day-1);

The temperature sensitivity of soil respiration was quantified using the Q10 function[38], which describes the factor by which the respiration rate increases with a 10 °C rise in temperature. The Q10 values were calculated based on the cumulative carbon mineralized (C0) at 10 and 25 °C using[38]:

where R2 and R1 are the respiration rates (or in this case cumulative C mineralized) at temperatures T2

Samples from each soil horizon were analyzed for the total content of Sr, Pb, Zn, Co, Ni, Cr, V, As, and MnО by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy using a Spectroscan Max-G spectrometer as described before[39].

The assessment of soil pollution levels was conducted using the total soil pollution index (Zc, Saet index), as calculated using[40]:

where Kki = Ci/Cib (2), and Cib and Ci are the background and actual contents of the i-th element in the soil, respectively.

In the calculation of Zc, only accumulating elements were considered, and the boundary criterion Kk(crit) > 2 was applied[41], where Kk(crit) is the critical enrichment factor of the i-th element, defined as the ratio of the element’s concentration in soil to its background value at which pollution effects become significant. According to the soil pollution hazard assessment scale based on the total soil pollution index (Zc), contamination levels are classified as acceptable (Zc < 16), moderately hazardous (16 < Zc < 32), hazardous

As the background concentration of heavy metals, arsenic, and manganese oxide in the soils of northern Western Siberia, data from Bely Island and the vicinity of the settlements of Novy Port and Ust-Yuribey were used[44]. The calculation of Zc for soils from the Rai-Iz mountain massif (Polar Urals) was carried out excluding the concentration values of Zn, Ni, Co, MnO, and Cr. The exclusion of these elements and compounds was due to their abnormally high background concentrations, resulting from the rich mineralogical composition of ultramafic rocks, which are widespread in the Polar Urals[45].

The radial differentiation coefficient (R), proposed by Perelman and Kasimov[46], was used to study the profile heterogeneity of the chemical composition by comparing the concentrations of the substances in soil horizons with those in the parent material horizon. The coefficient was calculated using[45]:

where Chor indicates the concentration of the i element in the soil horizon, and Cpm represents its content in the parent material, where the influence of soil-forming processes on the chemical composition is conventionally considered negligible. A radial differentiation coefficient equal to one (R = 1) indicates that the element content in the horizon corresponds to its content in the parent material. An R value greater than 1 (R > 1) indicates accumulation of the element in that horizon. In contrast, a value less than 1 (R < 1) signifies its depletion from the horizon.

Data visualization and processing were performed using QGIS 3.36, Microsoft Excel, and OriginPro 2024.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

SOM mineralization and CO2 emission

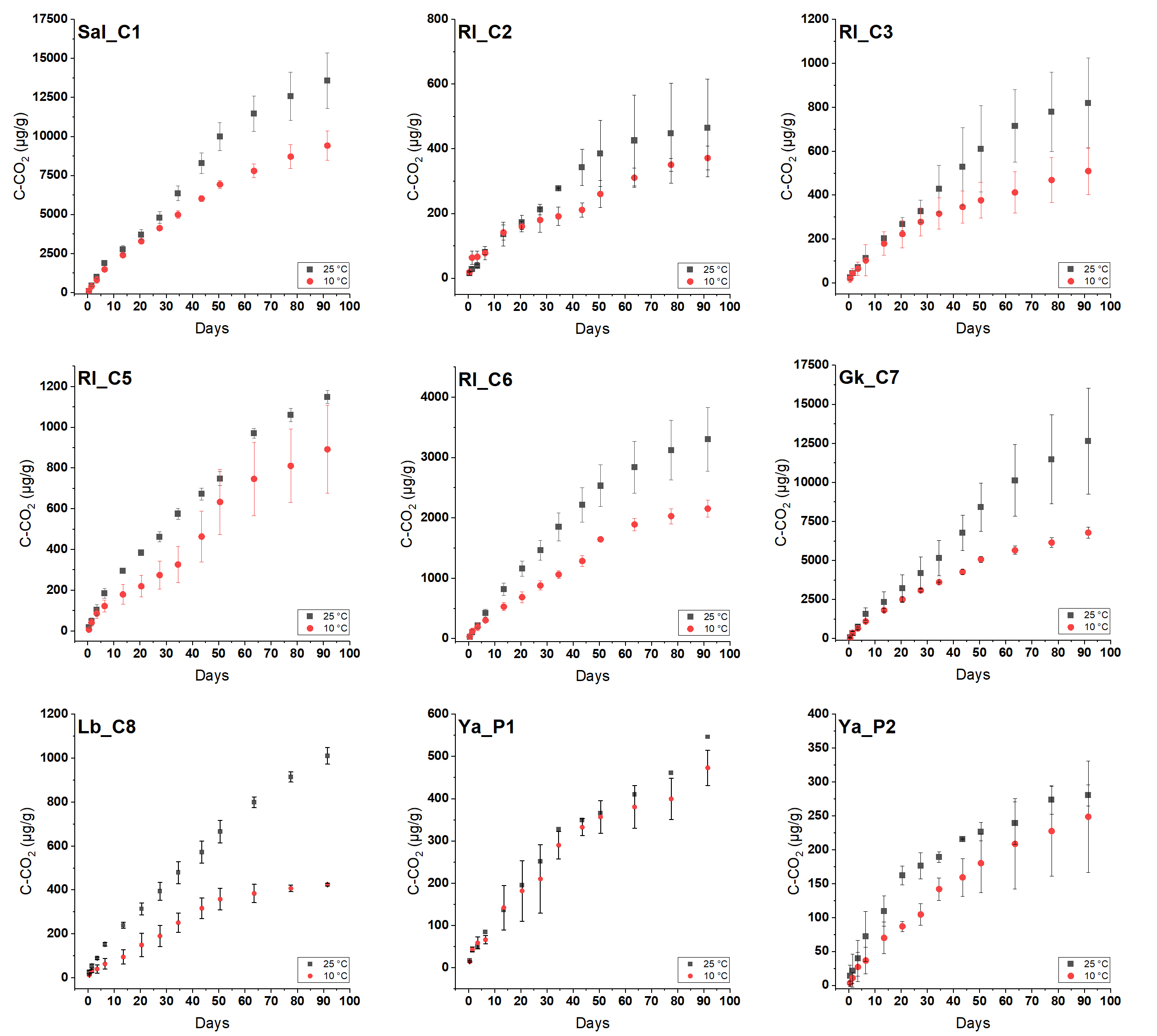

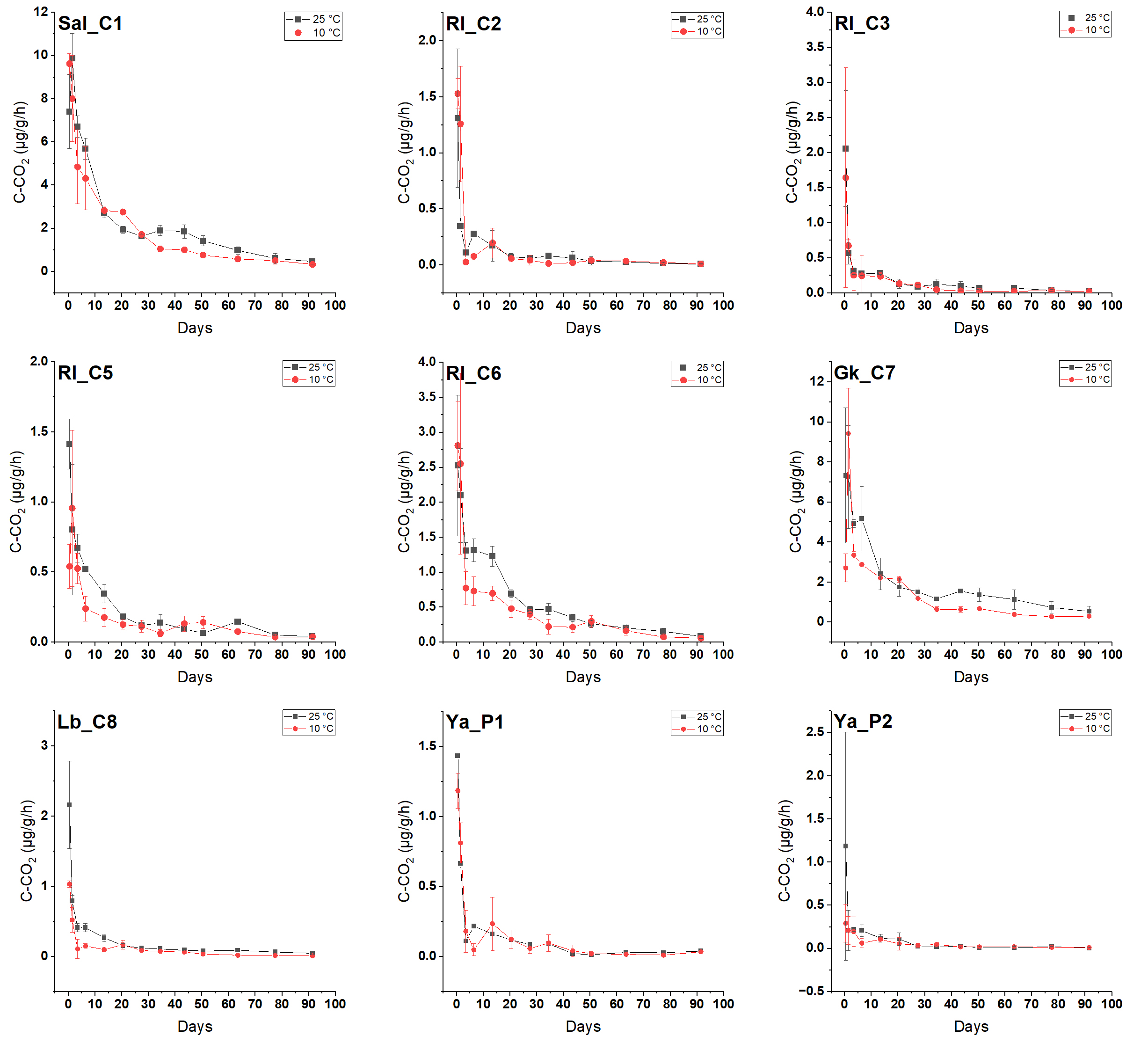

The PMC content in the studied soils ranged from 279.50 to 37,254.15 mg/kg, accounting for 11.59%-2.74% of the total SOC in the experimental variant with incubation at +25 °C [Figure 2]. Meanwhile, the variant with incubation at +10 °C results within a narrower range: 369.65-12,849.02 mg/kg PMC in the total soil mass, and 3.62%-4.82% of SOC. The cumulative mineralization curves are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Cumulative curves of SOM mineralization for the studied soils [mean ± SD (n = 3)]. Incubation temperatures of 25 and 10 °C. Ya_Р1, Ya_Р2 - soils of the southern hypoarctic tundras of the Yamal Peninsula. RI_С2-RI_С6 - soils of the mountain tundras of the Polar Urals. Sal_C1, Gk_С7, Lb_С8 - soils of the forest-tundra of the Lower Ob region (Figure was created using Origin Pro 2024 software). SOM: Soil organic matter; SD: Standard deviation.

In both cases, the maximum values were recorded in the upper organogenic soil horizons: the peat (TE) horizon of the cryogenic Cryic Histosol at key site C7 (plain moss-shrub-dwarf shrub forest-tundra) and the Oao horizon of the Albic Podzol at site C1 (plain herb-moss-dwarf shrub forest-tundra). This is related to the composition of the incoming plant litter from the herb-moss-dwarf shrub and moss-dwarf shrub-shrub plant cover, which is rich in lignin (primarily from the remains of shrubs and dwarf shrubs). The minimum values were recorded in the upper soil layer (0-10 cm), corresponding to the Spodic (BH) horizon characterized by lower SOC content compared to organogenic and organo-accumulative horizons, as observed in the Entic Podzol at site P2 (plain polygonal dwarf shrub-lichen tundra). The absence of a distinct organic horizon and, presumably, a lower intensity of incoming plant litter rich in lignin[47] at this site resulted in reduced mineralization. A similar pattern was observed in the topsoil of a Turbic Podzol at site P1. Among the upper organogenic and organo-mineral horizons, the minimum values were 678.97 mg/kg of PMC in the total soil mass (3.71% of SOC) and 427.85 mg/kg PMC in the total soil mass (2.34% of SOC) in the topsoil (AY) horizon of the Skeletic Cambisol at site C2 (mountain dwarf shrub-herb tundra) for the

The maximum and minimum mineralization intensity (MI) values were recorded in the same horizons as the extreme or near-extreme values of PMC: 10.23 (12.13)-228.25 and 5.30 (8.65)-190.65 in the treatments incubated at +25 and +10 °C, respectively [Table 2]. The values in parentheses are the minimum MI values for the upper organic horizons, and the values preceding them represent the absolute minimum values of this parameter among all the studied soils, in both cases corresponding to the mineral-rich topsoil. Alongside the influence of soil properties, a dependence of SOM mineralization on the thermal conditions during incubation was demonstrated. Almost all parameters, with the exception of PMC for the BH horizon of the Entic Podzol at the site P2 and the mineralization constants for some samples, were higher in the experiment with incubation at +25 °C, which is associated with the greater activity of microorganisms under temperatures close to the universal optimum range. However, under the actual conditions of Yamal, where average growing-season temperatures range from +8 °C to +12 °C, the pattern observed in the incubation experiment at +10 °C is more likely to occur.

Parameters of SOM mineralization at different temperatures

| Site | SOC, % | PMC, mg/kg | K × 10-2 | MI* | PMC from SOC, % |

| +10 °C | |||||

| Sal_C1 | 26.68 | 12,849.02 ± 2,542.37 | 1.53 ± 0.32 | 190.65 ± 5.63 | 4.82 ± 0.95 |

| RI_C2 | 1.83 | 427.85 ± 19.78 | 2.02 ± 0.23 | 8.65 ± 1.37 | 2.34 ± 0.11 |

| RI_C3 | 4.08 | 572.76 ± 149.58 | 2.60 ± 1.06 | 14.18 ± 5.39 | 1.40 ± 0.37 |

| RI_C5 | 4.32 | 2,845.72 ± 867.75 | 0.45 ± 0.14 | 12.42 ± 3.25 | 6.59 ± 2.01 |

| RI_C6 | 14.64 | 3,475.89 ± 964.55 | 1.25 ± 0.46 | 40.68 ± 4.01 | 2.37 ± 0.66 |

| Gk_C7 | 32.14 | 8,603.89 ± 580.99 | 1.67 ± 0.07 | 143.10 ± 3.90 | 2.68 ± 0.18 |

| Lb_C8 | 1.04 | 596.48 ± 134.80 | 1.78 ± 0.97 | 9.98 ± 3.41 | 5.74 ± 1.30 |

| Ya_P1 | 1.51 | 596.90 ± 261.98 | 2.46 ± 1.44 | 12.18 ± 3.46 | 5.19 ± 2.28 |

| Ya_P2 | 1.02 | 369.65 ± 205.61 | 1.85 ± 1.14 | 5.30 ± 0.61 | 3.62 ± 2.02 |

| +25 ºС | |||||

| Sal_C1 | 26.68 | 20,173.39 ± 217.16 | 1.13 ± 0.09 | 228.25 ± 19.86 | 7.56 ± 0.08 |

| RI_C2 | 1.83 | 678.97 ± 444.38 | 2.42 ± 1.95 | 12.13 ± 2.46 | 3.71 ± 2.43 |

| RI_C3 | 4.08 | 1,209.66 ± 401.48 | 1.36 ± 0.19 | 15.94 ± 3.17 | 2.96 ± 0.98 |

| RI_C5 | 4.32 | 1,765.06 ± 150.46 | 1.17 ± 0.10 | 20.61 ± 0.17 | 4.08 ± 0.35 |

| RI_C6 | 14.64 | 4,452.15 ± 918.96 | 1.59 ± 0.20 | 69.43 ± 6.92 | 3.04 ± 0.63 |

| Gk_C7 | 32.14 | 37,254.15 ± 2,093.11 | 0.53 ± 0.20 | 177.48 ± 30.66 | 11.59 ± 6.25 |

| Lb_C8 | 1.04 | 1,830.26 ± 479.77 | 1.01 ± 0.48 | 16.97 ± 2.80 | 17.60 ± 4.61 |

| Ya_P1 | 1.51 | 630.09 ± 0.00 | 1.85 ± 0.00 | 11.65 ± 0.00 | 5.48 ± 0.00 |

| Ya_P2 | 1.02 | 279.50 ± 21.51 | 3.67 ± 0.32 | 10.23 ± 0.10 | 2.74 ± 0.21 |

The soil material of the upper layer (0-10 cm) at the site P1, identified as the Albic and Spodic [E+BH] horizon of the Turbic Podzol, showed the least dependence of MI on thermal conditions. However, based on this, it cannot be concluded that soils with reduced organic carbon content are less sensitive to temperature changes in this process, since the BH horizon of the Entic Podzol at the site P2 exhibited the greatest change in MI with varying incubation thermal conditions. The greatest difference in PMC values was observed in the eutrophic peat sampled at the site C7 (plain moss-draft shrub-shrub forest-tundra); however, this cannot be extrapolated to other peats covering a significant area of Western Siberia. Since a smaller portion of peat soils are fen eutrophic (70% of all West Siberian peats are high-moor oligotrophic). And for another peat soil sample, the peat (T) horizon of a Histic Cryosol of an intermountain draft shrub-herb-moss tundra (site C6), no significant difference in this parameter was found, based on calculations from experimental data obtained during incubation experiments at various temperatures. The smallest differences in PMC values were recorded for the topsoil of the Turbic Podzol and the Entic Podzol from the sites P1 and P2, respectively.

An examination of changes in the basal respiration rate [Figure 3] revealed a specific dependence of this parameter and its dynamics on soil type. For organogenic and organo-mineral soils at the early stages of the experiment, insignificant differences in the values of this parameter (within 0.5 µg C-CO2/g per hour) were recorded under different thermal conditions. Less frequently, the CO2 production rate was higher at the higher temperature. A reverse pattern was observed for mineral and cryoturbated horizons: for the soils from sites C8, P1, and P2, the basal respiration rate was higher at 10 °C. Further into the experiment, the curves of the respiration rate under different temperature conditions leveled off and converged, demonstrating a decrease in the intensity of CO2 production, with values approaching zero by the end of the experiment.

Figure 3. Soil basal respiration rate (µg C-CO2/g per hour) at different stages of incubation at 25 and 10 °C [mean ± SD (n = 3)]. Ya_Р1, Ya_Р2 - soils of the southern hypoarctic tundras of the Yamal Peninsula. RI_С2-RI_С6 - soils of the mountain tundras of the Polar Urals. Sal_C1, Gk_С7, Lb_С8 - soils of the forest-tundra of the Lower Ob region (Figure was created using Origin Pro 2024 software). SD: Standard deviation.

Here, peats and the soil material of the Oao horizon of the Albic Podzol from site C1 showed the greatest sensitivity to temperature changes. The peats, starting from day 5 of the experiment, and the coarse humus litter-peat horizon, starting from day 30, demonstrated higher basal respiration rates under thermal conditions corresponding to the sampling region during the growing season (+10 °C). These samples also exhibited the highest basal respiration rates at the beginning of the experiment (up to 10 µg C-CO2/g per hour). This is presumably due to the prevalence of oligotrophic bogs in the studied territory, the cryolithozone, and the harsh climate of the polar latitudes, which together determine low soil biological activity[47,48]. Oligotrophic microbial groups predominate over copiotrophic ones; in other words, the low intensity of incoming nutrient flux in these soils prevents the survival of copiotrophic microorganisms, which are adapted to habitats with a high nutrient supply[49].

The variability in PMC and basal respiration rates across the studied soils can be attributed to differences in their physicochemical properties. As shown in Supplementary Tables 1-2, soils with the highest mineralization potentials (e.g., the Oao horizon of Sal_C1 and the TE horizon of Gk_C7) are characterized by a high SOC content and an acidic pH. The high SOC content provides a substantial substrate pool for microbial metabolism[50]. The acidic pH in these organic horizons may select for specialized microbial communities adapted to such conditions[51]. In contrast, mineral soils (e.g., Ya_P2) with lower SOC content, finer texture, and potentially higher clay content likely stabilize organic matter through organo-mineral associations, reducing the accessibility of substrates to microbes and resulting in lower PMC values and mineralization intensities[52]. Furthermore, the cryoturbated horizons showed distinct patterns, likely due to the physical disruption of soil aggregates and the incorporation of fresh organic material into deeper, colder layers, which aligns with the observed inverse temperature response in some samples[53].

The obtained results indicate a potential threat of increased emissions of major greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide and water vapor) from the upper organogenic and organo-mineral horizons of tundra soils under rising temperatures, which may occur in the context of global climate change and further exacerbate the problem. The study by Matyshak et al.[54], which examined the temperature sensitivity of CO2 emissions from the surface of peat soils in the cryolithozone (with elevated temperature simulated through transplantation of soil monoliths), confirms this phenomenon - namely, increased carbon dioxide production at higher temperatures - in natural settings. Comparison of the obtained results with other studies reveals a similar pattern of MI changes with increasing temperature in Histic Cryosols of the southern tundra and northern taiga, while the changes are less pronounced in underlying horizons[55].

The results of the study on SOM mineralization in the mountain-tundra belt of the Khibiny Mountains, with incubation at an increased temperature (22 °C), revealed a higher content of PMC in organogenic horizons (5,139 ± 76 mg C/100 g, 16.1% PMC/SOC) and a greater MI [61.7 ± 2.5 mg C/(100 g·day)][56]. This can be related to the longer growing season duration (140-150 days), the content of biogenic elements, the C/N ratio, and differences in species composition, richness, and diversity of plant communities and microorganisms[57].

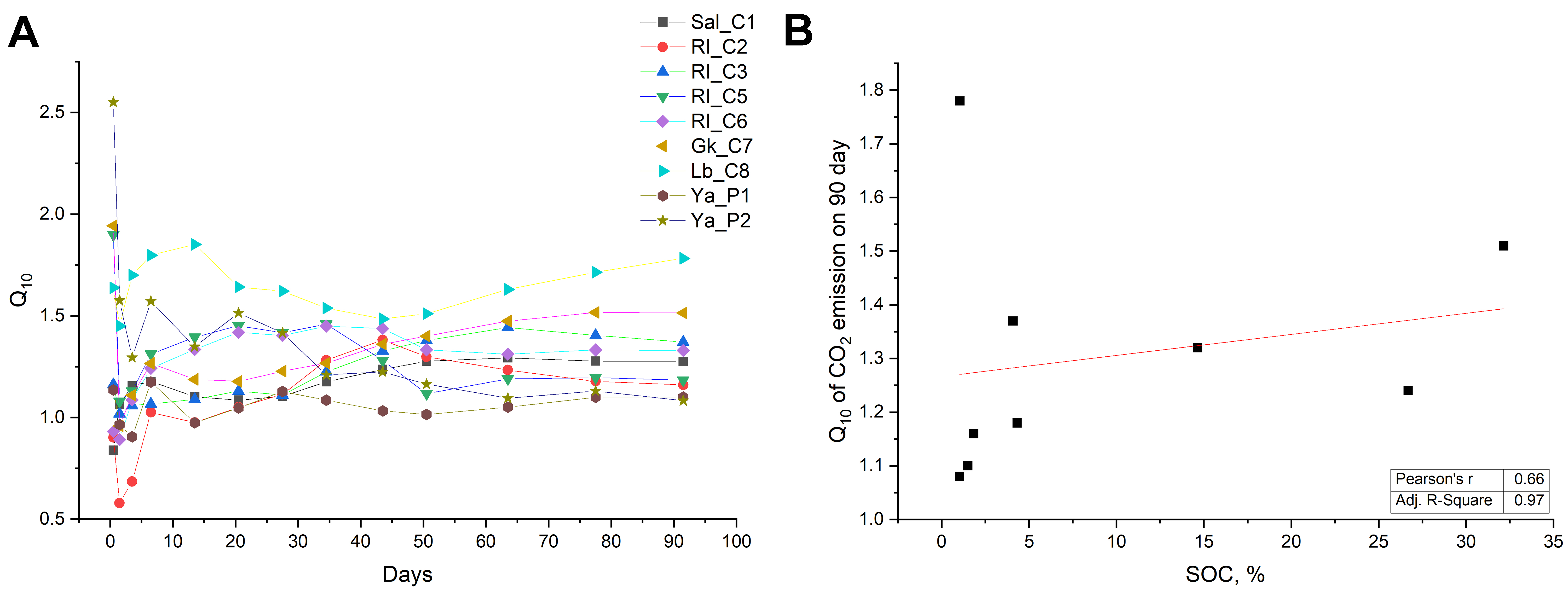

The calculated Q10 values for cumulative CO2 production at different times of incubation across the studied soils varied widely [Figure 4A]. At the initial stages of the experiment, Q10 values ranged from 0.5 to 2.5, but after 7 days of incubation, a steady increase was observed. This suggests that the microbial communities studied may be more cold-adapted, and warming above their thermal optimum could stress or alter the community, potentially slowing decomposition rates in the short term[58]. This aligns with our observed patterns of basal respiration, where some mineral horizons respired more at 10 °C than at 25 °C [Figure 3]. Notably, the highest Q10 values (greater than 1.5, for 90 days of incubation) were observed in soils with thick organogenic horizons and high SOC content (e.g., Histic Cryosols and Cryic Histosol), indicating that organic matter mineralization in these layers is highly sensitive to temperature increases[59,60]. Analysis of the obtained data showed a relationship between Q10 and SOC content [Figure 4B]; an increase in Q10 occurred in parallel with increasing SOC content in soils (Pearson’s r = 0.66, R2 = 0.97). This underscores the vulnerability of these carbon-rich pools to warming[61]. In contrast, mineral and cryoturbated topsoil horizons (Podzols and Cambisols) often exhibited Q10 values closer to or even below 1.5, indicating low or inverse temperature sensitivity over the long term. This divergence in Q10 across soils highlights the critical importance of considering soil heterogeneity when modeling the response of permafrost-affected ecosystems to climate change[62]. Areas with both high labile carbon content and high temperature sensitivity (Q10) represent the greatest potential for positive feedback to climate change[58].

Ecotoxicological state of soils and radial differentiation of metals

The studied area is characterized by high diversity and patchiness of the soil cover, while the level of heavy metal contamination in the soils is generally low. The highest concentrations of heavy metals were observed in soil samples with high SOC content and high clay and silt fractions. Soils of the southern hypoarctic tundras of the Yamal Peninsula contained Pb - 14 mg/kg, Co - 9 mg/kg, and V - 42 mg/kg. Soils of the mountain tundras of the Polar Urals contained Pb - 11 mg/kg and V - 87 mg/kg. Soils of the forest-tundra of the Lower Ob region contained Pb - 27 mg/kg, Co - 18 mg/kg, and V - 129 mg/kg, which is attributed to their high sorption capacity[45,63]. The level of soil contamination by heavy metals is influenced both by the functional load on the area and the physicochemical characteristics of soils[60]. Soil contamination with heavy metals is associated with areas of geological exploration, hydrocarbon production, roads, and settlements. Soils sampled in areas remote from major transport highways exhibit low (acceptable) contamination levels (Zc < 16), consistent with earlier studies[63].

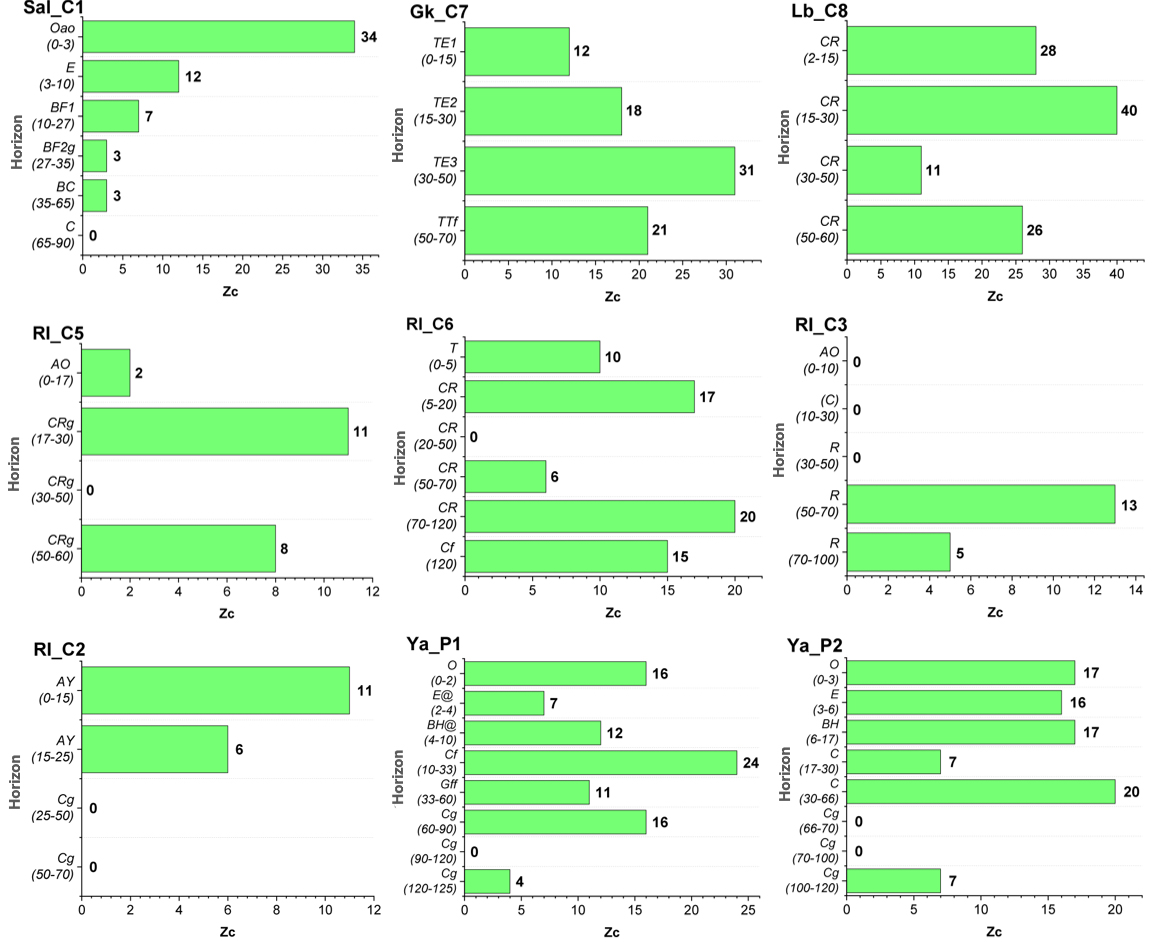

Based on the total heavy metal content in the soils, the values of Zc were calculated [Figure 5]. Analysis of the obtained data, considering territorial affiliation, revealed the following: Out of 16 soil samples collected on the Yamal Peninsula (Ya_P1, Ya_P2), 9 were characterized by low (acceptable) total contamination levels

Figure 5. Total soil pollution indexes (Zc) values: Ya_Р1, Ya_Р2 - soils of the southern hypoarctic tundras of the Yamal Peninsula, RI_С2-RI_С6 - soils of the mountain tundras of Polar Urals, Sal_C1, Gk_С7, Lb_С8 - soils of the forest-tundra of the Lower Ob region (Figure was created using Origin Pro 2024 software).

It was found that the majority (32 out of 47) of soil samples were characterized by a low (acceptable) level of total contamination (Zc < 16), 13 samples by a moderate (moderately hazardous) level (16 < Zc < 32), and only 2 by a high (hazardous) level (32 < Zc < 128). The priority pollutants were lead (Pb), vanadium (V), and cobalt (Co). Elevated concentrations of lead and vanadium indicate a significant contribution of vehicle emissions to heavy metal contamination of the soil cover. The spatial distribution of soils contaminated with lead and vanadium correlates with the location of roads[64], confirming the dominant role of vehicle emissions in the anthropogenic load on the environment of YaNAO and the ecotoxicological state of soils in the region[65,66].

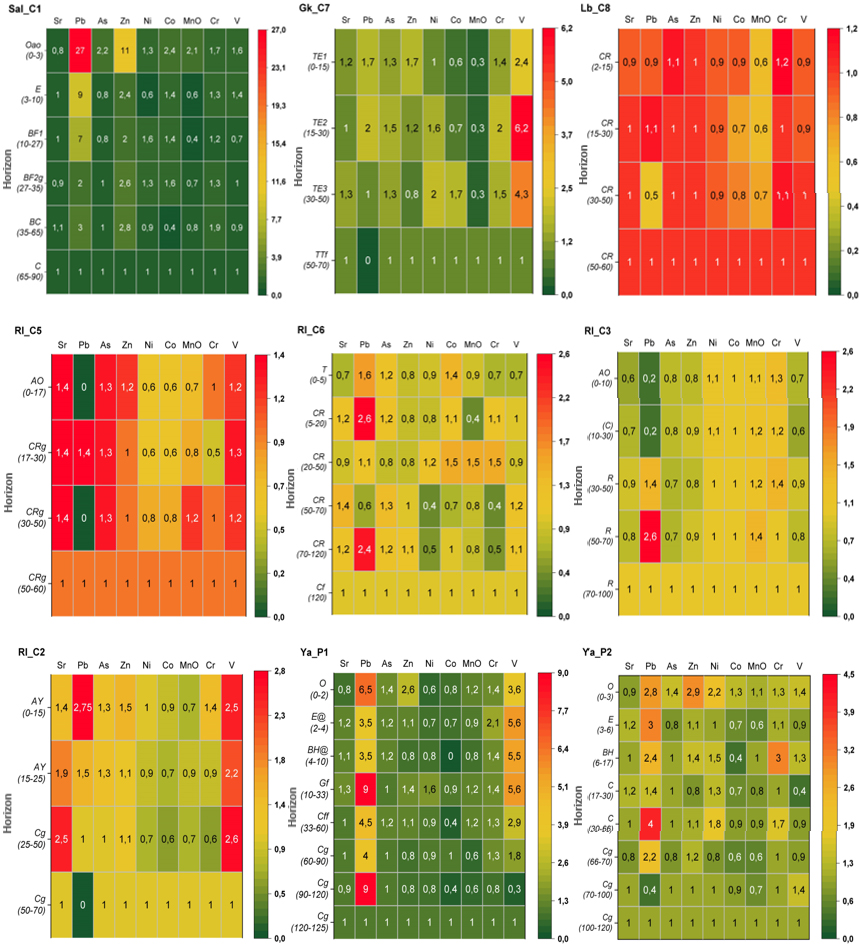

The application of the coefficient of radial differentiation (R) enabled a quantitative assessment of the influence of pedogenesis on the redistribution of individual chemical elements concentrations throughout the soil profile relative to the parent material. Values of the radial differentiation coefficient of chemical element concentrations in the soils of Yamal, Polar Urals and Lower Ob region exhibit distinct profile distribution patterns [Figure 6].

Figure 6. Coefficients of radial differentiation (R) of chemical elements in the studied soils: Ya_P1, Ya_P2 - soils of the southern hypoarctic tundras of the Yamal Peninsula; RI_C2–RI_C6 - soils of the mountain tundras of the Polar Urals; Sal_C1, Gk_C7, Lb_C8 - soils of the forest-tundra of the Lower Ob region. (Figure was created using Origin Pro 2024 software).

In Albic Podzol (Sal_C1), an accumulation of Pb, Zn, and Co was observed in the upper horizons, while the radial differentiation of other elements was insignificant. In Cryic Histosol (Gk_C7), V and Ni were leached into lower horizons, whereas Pb and Zn accumulated in the upper horizons. In Histic Cryosol, Cr accumulated in the upper horizon, while Ni, Co, and MnO leached into lower horizons. In Skeletic Cryosol at one site (RI_C5), Ni, Co, and MnO were leached and accumulated in the lower horizons, while Sr, As, and Zn accumulated in the upper horizons. At the second site (RI_C6), Pb accumulated throughout the soil profile; V, Zn, and partially Sr were leached downward, whereas Co was retained in the upper horizons. The arsenic (As) content remained practically uniform throughout the profile. In the Skeletic Leptosol (RI_C3), Pb accumulated in the lower horizons, Ni, Co, and MnO were distributed almost uniformly, and Sr, As, Zn, and V leached into the lower horizons. In Skeletic Cambisol (RI_C2), Pb primarily accumulated in the upper horizon, Sr migrated to lower horizons, and V and Zn were distributed throughout the profile. At the same time, Ni, Co, MnO, and Cr were leached downward. In Podzols of the Yamal Peninsula (Ya_P1, Ya_P2), Pb accumulated in two soil profiles; in Turbic Podzol, V and Cr accumulated, Sr and As showed no significant redistribution relative to the parent material, and Ni and Co leached from the upper horizons. In Entic Podzol, Zn, As, Co, MnO, Cr, V, and Ni accumulated in the topsoil.

The degree of radial differentiation of biophilic and geogenic elements inherited from the parent material may be associated with differences in parent material genesis, variations in soil pH and particle size distribution, and the nature and intensity of anthropogenic impacts. Moskovchenko et al. previously established that the radial distribution of Mn, Fe, Zn, and Pb in Gleysol profiles on Bely Island was of the eluvial-illuvial type, with the highest concentrations in surface organogenic and suprapermafrost horizons. In contrast, in the organogenic horizons of soils in the Nadym District of YaNAO (which experience moderate weathering and a leaching water regime), Ca, P, and S accumulated, while Co, Cr, and Ni were concentrated in mineral horizons. The radial geochemical structure of Cryosols combines eluvial-illuvial differentiation with biogenic accumulation, whereas in Podzols, element distribution is predominantly eluvial-illuvial, with minimum concentrations in the Albic horizon[67].

The radial differentiation of the studied elements was largely consistent with the results of the ecotoxicological assessment of soil quality. In the forest-tundra soils of the Lower Ob region, one of the highest total soil pollution index values (Zc = 34) was observed in Albic Podzol (Sal_C1), which is associated with high anthropogenic load, specifically intense road traffic. The radial differentiation coefficient indicated accumulation of Zn (R = 11) and Pb (R = 27) in the upper horizons, likely due to retention by organic matter. Along the profile, pH increased from 3.9 to 4.9. The highest Zc value (Zc = 40) was observed in Histic Cryosol, which had a neutral pH of 5.6-6.2, although radial differentiation was not pronounced. In acidic (pH 4.0-4.4) organogenic soils with Zc = 31, V accumulated in the middle of the profile, while other heavy metals showed minor accumulation in the upper horizons. Acidic (pH 4.0-5.4) sandy soils of the southern hypoarctic tundras were characterized by moderate total contamination (Zc ranging from 0 to 24; acceptable to moderately hazardous), with pronounced redistribution of Pb (R = 1.4-9) throughout the profile and accumulation of Zn (R = 2.6; 2.9) and V (R = 5.6; 1.4) in the upper horizons. In the mountain tundra soils of the Polar Urals, with varying particle size distributions, near-neutral pH (6.0-7.2), and low total contamination levels (Zc < 16), no significant radial redistribution of the studied elements (R = 0-2.75) was observed.

Interplay of SOM mineralization and metal content

The combined data on SOM mineralization kinetics and the Zc allow a preliminary assessment of potential interactions between soil contamination and carbon cycling in the studied soils. While a detailed statistical correlation analysis is beyond the primary scope of this manuscript, several noteworthy observations can be made. Soils with moderate to high contamination levels (e.g., Sal_C1, Gk_C7, Zc > 16) did not consistently show suppressed mineralization potential compared to less contaminated soils from similar landscape positions. For instance, the Cryic Histosol (Gk_C7) exhibited one of the highest PMC values despite its elevated Zc, suggesting that the organic-rich matrix in these soils may bind heavy metals, reducing their immediate bioavailability and toxicity to microbial decomposers[68].

It has been demonstrated that total heavy metal/metalloid concentrations in contaminated soils do not fully reflect toxicity, as bioavailability varies due to physico-chemical interactions with the soil matrix[69]. Previous studies indicate that soil contamination with heavy metals and metalloids can alter microbial communities: tolerant microorganisms may replace more susceptible ones and increase in abundance[69,70]. These microorganisms can immobilize heavy metals or convert them into less toxic forms[71]. Analyses of the Yamal soil microbiome revealed dominant phyla including Acidobacteria (> 10% of total microorganisms), Gemmatimonadetes (> 4%), and other bacterial groups[72]. Gemmatimonas are highly sensitive to Cd, Pb, Zn, and Hg, whereas Acidobacteria are highly tolerant to these metals[69]. This highlights SOM as a key factor influencing heavy metal bioavailability, which in turn affects microbial community structure.

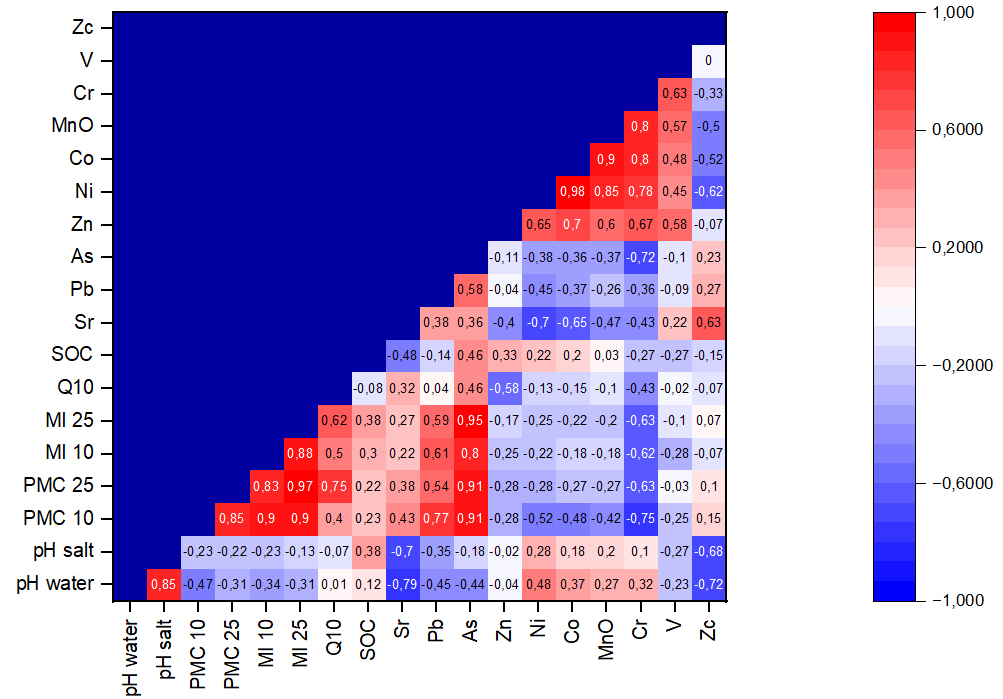

A weak linear relationship was observed between Zc and PMC values; however, a stronger correlation was observed under temperature conditions typical of the sampling region. For incubation at 25 °C, the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.24 (R2 = 0.06), whereas for incubation at 10 °C, it was 0.46 (R2 = 0.21). The correlation coefficient between Zc and Q10 was 0.28 (R2 = 0.28). The Spearman correlations of the studied parameters are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Spearman correlation matrix of the studied parameters: pH, PCM, MI, Q10, SOC, Zc, and heavy metals concentrations (Figure was created using Origin Pro 2024 software). PMC: Potentially mineralizable organic carbon; MI: mineralization intensity; SOC: soil organic carbon.

There was almost no correlation between pollutants such as lead, nickel, cobalt, manganese oxide, and vanadium, as well as Zc, and the mineralization parameter Q10, with low statistical significance (Spearman’s r ranging from -0.13 to 0.04, P = 0.70-0.91). For strontium and arsenic, weak and moderate positive correlations, respectively, were observed between their concentrations and Q10 (Spearman’s r = 0.32-0.46, P = 0.21-0.41), while zinc and chromium showed moderate negative correlations (Spearman’s r = -0.56 to -0.46, P = 0.10-0.24). All studied pollutants, as well as pH values, exerted a stronger influence on PMC10 than on PMC25, likely because PMC10 was measured under conditions closer to those in the study region.

The influence of soil physico-chemical factors on the MI, calculated from incubation experiments at 10 and 25 °C, was generally similar. The strongest positive correlations were observed with arsenic (Spearman’s r = 0.80-0.95, P < 0.01) and lead (Spearman’s r = 0.59-0.61, P = 0.07-0.08), possibly due to the high toxicity of these elements[68] and their suppressive effects on microbial activity affecting mineralization. Negative correlations were observed with chromium (Spearman’s r = -0.62 to -0.63, P = 0.07-0.08). Other pollutants exhibited weak negative correlations with MI (positive for strontium: Spearman’s r = 0.22-0.27, P > 0.49; others: r = -0.10 to -0.28, P > 0.46). Soil acidity showed weak to moderate negative correlations with all mineralization characteristics (Spearman’s r = -0.47 to -0.31, P = 0.20-0.42), except for Q10, which had a weak positive correlation (r = 0.07, P = 0.98).

One possible reason for the weak correlations between heavy metal pollution and mineralization characteristics is the prevalence of immobile, silicate-bound forms of toxicants that are not bioavailable to microorganisms, or microbial tolerance to these pollutants[73,74]. Conversely, in mineral soils with lower SOC content, a different relationship may occur, as metals could be more bioavailable. The complex interplay between soil properties (pH, SOC, texture), metal type, and bioavailability makes generalized predictions difficult. Future targeted research, including eco-toxicological assays on microbial communities, is needed to disentangle these effects. Nonetheless, establishing these baseline concurrent measurements is an important first step, revealing that areas of highest anthropogenic pressure also store large amounts of PMC, creating potential hotspots for interactions between pollution and climate-carbon feedbacks.

Limitations of the research

At this stage, soil contamination was assessed for nine heavy metals and their compounds; in the future, a broader list of pollutants could be included for a more comprehensive ecotoxicological assessment of the area. In addition, the ecotoxicological analysis focused on total heavy metal content in soils, which does not fully reflect their bioavailability. Finally, the laboratory incubation conditions used to study SOC mineralization differed from those in the field.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides comprehensive data on SOM mineralization dynamics and the ecotoxicological state across major soil types in the Yamal region of West Siberia. Significant spatial variability in PMC was observed, ranging from 279.50 mg/kg to 37,254.15 mg/kg (2.74%-11.59% of SOC), with the highest mineralization rates in the topsoil horizons. Temperature dependence was evident, with higher mineralization rates at 25 °C in most samples. However, some mineral horizons showed the opposite pattern, suggesting complex microbial responses to warming in cryogenic environments that require further investigation. The demonstrated temperature sensitivity of SOM mineralization, particularly in organogenic horizons, indicates that warming affects carbon emissions from these soils. The highest Q10 values (> 1.5 for 90-day incubation) occurred in soils with thick organogenic horizons and high SOC content (e.g., Cryic Histosol and Histic Cryosol), indicating that SOM mineralization in these layers is highly sensitive to increased temperatures. Kinetic parameters derived from the 90-day incubation experiments can be incorporated into biogeochemical models to refine projections of carbon-climate feedbacks in permafrost regions, though further validation is needed.

Regarding ecotoxicological state, 68% of analyzed soil samples (32 of 47) exhibited low (acceptable) contamination levels (Zc < 16), 28% (13 samples) showed moderate contamination, and 4% (2 samples) demonstrated high contamination levels. The primary ecotoxicological threat arises from oil and gas industry activities. Soils near production facilities and transport infrastructure exhibited substantially higher contamination levels, with Zc values reaching up to 40 in some cases. Radial differentiation analysis revealed distinct patterns of element redistribution across soil profiles, with Pb, Zn, and V showing strong accumulation in upper horizons of anthropogenically impacted sites. Temperature sensitivity (Q10) was highest in SOC rich soil horizons, indicating they are potential hotspots for carbon release under warming. Although a direct inhibitory effect of heavy metals on mineralization was not consistently observed, the spatial coincidence of elevated pollution levels and large labile carbon pools in soils near industrial infrastructure warrants further study. These areas should be prioritized for long-term monitoring, as potential changes in contaminant bioavailability or microbial community responses to warming could modulate the permafrost-carbon feedback.

These findings underscore the urgent need for integrated monitoring programs that track both carbon cycling and contaminant loads in Arctic soils. As development pressures increase in the Russian Arctic, maintaining the balance between economic activity and environmental protection will require science-based regulatory frameworks informed by comprehensive soil assessments. Future research should focus on long-term monitoring of SOM mineralization under natural field conditions and expanded ecotoxicological assessments across broader spatial scales to establish baseline conditions in this rapidly changing region.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the staff of the “Chemical Analysis and Materials Research Centre”, St. Petersburg University Research Park, for performing the elemental analysis of soil samples.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data acquisition, fieldwork: Abakumov, E.; Nizamutdinov, T.

Laboratory analyses: Artyukhov, E.; Nizamutdinov, T.; Dinkelaker, N.

Software, visualization, statistics: Kushnov, I.; Shvetsova, A.; Nizamutdinov, T.

Writing - original draft: Shvetsova, A.; Pokhodnya, E.; Vainberg, A.

Supervision, writing - review and editing: Dinkelaker, N.; Abakumov, E.

Availability of data and materials

The data and Supplementary Materials can be provided upon personal request to the corresponding author.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, grant № 24-44-00006, “Comparative Metagenomics Study of the Carbon Cycle Microbiome in Permafrost Regions on the Yamal Peninsula and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau”.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623-7.

2. Russian Federation. Seventh National Communication of the Russian Federation, Submitted in Accordance with Articles 4 and 12 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and Article 7 of the Kyoto Protocol; Moscow, 2017. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/2017%20ARR%20of%20Russia_complete.pdf (accessed 2026-01-26).

3. Ivanov, A. L.; Stolbovoy, V. S. The Initiative “4 per 1000” - a new global challenge for the soils of Russia. Dokuchaev. Soil. Bulletin. 2019, 98, 185-202.

4. Han, H.; Zeeshan, Z.; Talpur, B. A.; et al. Studying long term relationship between carbon emissions, soil, and climate change: insights from a global earth modeling framework. Int. J. Appl. Earth. Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 130, 103902.

5. Miner, K. R.; Turetsky, M. R.; Malina, E.; et al. Permafrost carbon emissions in a changing arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth. Environ. 2022, 3, 55-67.

6. Schuur, E. A.; Abbott, B. W.; Commane, R.; et al. Permafrost and climate change: carbon cycle feedbacks from the warming arctic. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 343-71.

7. Semenov, V. M.; Kogut, B. M.; Zinyakova, N. B.; et al. Biologically active organic matter in soils of European Russia. Eurasian. Soil. Sc. 2018, 51, 434-47.

8. Lavallee, J. M.; Soong, J. L.; Cotrufo, M. F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 26, 261-73.

9. Kurganova, I. N.; Semenov, V. M.; Kudejarov, V. N. Climate and land use as the key factors of organic matter stability in soils. Dokl. Earth. Sci. 2019, 489, 1481-5.

10. Song, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; et al. Spatial distribution, drivers, and future variation of soil organic carbon in China’s ecosystems: a meta-analysis and machine-learning assessment. Ecological. Indicators. 2025, 179, 114255.

11. Previdi, M.; Smith, K. L.; Polvani, L. M. Arctic amplification of climate change: a review of underlying mechanisms. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 093003.

12. Ivanov, A. L.; Savin, I. Y.; Stolbovoy, V. S.; Dukhanin, A. Y.; Kozlov, D. N.; Bamatov, I. M. Global climate and soil cover - implications for land use in Russia. Dokuchaev. Soil. Bull. 2021, 107, 5-32.

13. Feng, J.; Wang, C.; Lei, J.; et al. Warming-induced permafrost thaw exacerbates tundra soil carbon decomposition mediated by microbial community. Microbiome 2020, 8, 3.

14. Ludwig, B.; Teepe, R.; Lopes de Gerenyu, V.; Flessa, H. CO2 and N2O emissions from gleyic soils in the Russian tundra and a German forest during freeze-thaw periods-a microcosm study. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 3516-9.

15. Schaller, J.; Stimmler, P.; Göckede, M.; Augustin, J.; Lacroix, F.; Hoffmann, M. Arctic soil CO2 release during freeze-thaw cycles modulated by silicon and calcium. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 870, 161943.

16. Semenov, V. M.; Kravchenko, I. K.; Ivannikova, L. A.; et al. Experimental determination of the active organic matter content in some soils of natural and agricultural ecosystems. Eurasian. Soil. Sc. 2006, 39, 251-60.

17. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (Information Profile). https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/economic_diplomacy/vnesneekonomiceskie-svazi-sub-ektov-rossijskoj-federacii/2010555/ (accessed 2026-01-26).

18. Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring (Roshydromet). Report on Climate Features in the Territory of the Russian Federation for 2021; Moscow, 2022. https://cc.voeikovmgo.ru/images/sobytiya/2022/03/doklad_klimat2021.pdf (accessed 2026-01-26).

19. Vodyanitskii, Y. N. Standards for the contents of heavy metals and metalloids in soils. Eurasian. Soil. Sc. 2012, 45, 321-8.

20. Alekseev, I. I.; Dinkelaker, N. V.; Oripova, A. A.; et al. Assessment of ecotoxicological state of soils of the Polar Ural and Southern Yamal. Environ. Health. Habitat. 2017, 96, 941-5. https://innoscience.ru/0016-9900/article/view/640702 (accessed 2026-01-30).

21. Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Lv, Y.; et al. Effects of heavy metals/metalloids and soil properties on microbial communities in farmland in the vicinity of a metals smelter. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 707786.

22. Campillo-Cora, C.; Rodríguez-Seijo, A.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Fernández-Calviño, D.; Santás-Miguel, V. Effect of heavy metal pollution on soil microorganisms: influence of soil physicochemical properties. A systematic review. Eur. J. Soil. Biol. 2025, 124, 103706.

23. Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Microbial diversity and community assembly in heavy metal contaminated soils. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2025, 22, 12440.

24. Su, C.; Xie, R.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Liang, R. Ecological responses of soil microbial communities to heavy metal stress in a coal-based industrial region in China. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1392.

25. Chauhan, A.; Patzner, M. S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; et al. Interactions between iron and carbon in permafrost thaw ponds. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 946, 174321.

26. National Atlas of Russia. 2008. The Stages of Evolution of the Administrative-Territorial Structure, Vol. 3; Russia, Moscow: Roskartographia, 496. https://nationalatlas.ru/tom3/ (accessed 2026-01-26).

27. Konyushkov, D. E.; Ananko, T. V.; Gerasimova, M. I.; Lebedeva, I. I. Actualization of the contents of the soil map of Russian Federation (1 : 2.5 M scale) in the format of the classification system of Russian soils for the development of the new digital map of Russia. Dokuchaev. Soil. Bulletin. 2020, 102, 21-48.

28. Zhangurov, E. V.; Kaverin, D. A.; Dymov, A. A.; Startsev, V. V. Permafrost-affected gleyzems of the Subpolar Urals: morphology, cryogenic structure, temperature regime, and physicochemical properties. Eurasian. Soil. Sc. 2025, 58, 107.

29. Kislov, A. V.; Alyautdinov, A. R.; Baranskaya, A. V.; et al. Projection of climate change and the intensity of exogenous processes on the territory of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District. Dokl. Earth. Sc. 2023, 510, 487-93.

30. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Standard operating procedure for soil pH determination. FAO: Rome; 2021; 23. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/6ad6862a-eadc-437c-b359-ef14cb687222/content (accessed 2026-01-26).

32. Dembovetsky, A. V.; Tyugai, Z. N.; Shein, E. V. The granulometric composition of soils: history, development of methods, current state, and prospects. Moscow. Univ. Soil. Sci. Bull. 2024, 79, 387-92.

33. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). SOP Dumas dry combustion method; FAO: Rome, 2020. https://www.fao.org/global-soil-partnership/glosolan-old/soil-analysis/sops/volume-2-2/en/ (accessed 2026-01-30).

34. Semenov, V. M.; Lebedeva, T. N.; Lopes de Gerenuy, V. O.; Ovsepyan, L. A.; Semenov, M. V.; Kurganova, I. N. Pools and fractions of organic carbon in soil: structure, functions and methods of determination. J. Soils. Environ. 2023, 6, e199. https://soils-journal.ru/index.php/POS/article/view/199 (accessed 2026-01-30).

35. Tong, D.; Li, Z.; Xiao, H.; Nie, X.; Liu, C.; Zhou, M. How do soil microbes exert impact on soil respiration and its temperature sensitivity? Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 3048-58.

36. Matveeva, T.; Sidorchuk, A. Modelling of surface runoff on the Yamal Peninsula, Russia, using ERA5 reanalysis. Water 2020, 12, 2099.

37. Cheng, B.; Dai, H. Y.; Liu, T. J.; et al. Mineralization characteristics of soil organic carbon under different herbaceous plant mosaics in semi-arid grasslands. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22196.

38. Meyer, N.; Welp, G.; Amelung, W. The temperature sensitivity (Q10) of soil respiration: controlling factors and spatial prediction at regional scale based on environmental soil classes. Global. Biogeochemical. Cycles. 2018, 32, 306-23.

39. Khelifi, F.; Batool, S.; Kechiched, R.; Padoan, E.; Ncibi, K.; Hamed, Y. Abundance, distribution, and ecological/environmental risks of critical rare earth elements (REE) in phosphate ore, soil, tailings, and sediments: application of spectroscopic fingerprinting. J. Soils. Sediments. 2024, 24, 2099-118.

40. Vodyanitskii, Y. Standards for the contents of heavy metals in soils of some states. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2016, 14, 257-63.

41. Faurat, A.; Azhayev, G.; Shupshibayev, K.; Akhmetov, K.; Boribay, E.; Abylkhassanov, T. Assessment of heavy metal contamination and health risks in “snow cover-soil cover-vegetation system” of urban and rural gardens of an industrial city in Kazakhstan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2024, 21, 1002.

43. SanPiN 1.2.3685-21; Hygienic Standards and Requirements for Ensuring the Safety and (or) Harmlessness of Environmental Factors for Humans*; Sanitary Rules and Norms of the Russian Federation; Federal Agency on Technical Regulating and Metrology (GOST R): Moscow, Russia, 2021. https://fsvps.gov.ru/files/postanovlenie-glavnogo-gosudarstve-3/ (accessed 2025-01-30).

44. Tomashunos, V. M.; Abakumov, E. V. The content of heavy metals in soils of the Yamal peninsula and the Bely Island. Hyg. Sanit. 2015, 93, 26-31. (in Russian with English abstract). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281832818_The_content_of_heavy_metals_in_soils_of_the_Yamal_Peninsula_and_thE_Bely_Island (accessed 2025-01-26).

45. Kostrov, N. P.; Ivanov, K. S. Gravitationally-geological model of the Polar Urals transect. Lithosphere 2024, 24, 587-608.

46. Perel’man, A. I.; Kasimov, N. S. Geochemistry of the Landscape; Astreya: Moscow, 1999. https://www.geokniga.org/books/3161 (accessed 2025-01-26).

47. Nizamutdinov, T.; Bolshiianova, O.; Morgun, E.; Abakumov, E. Molecular composition of humic acids and soil organic matter stabilization rate of the first arctic carbon measurement supersite “seven larches”. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6673.

48. Tulina, A. S.; Semenov, V. M.; Rozanova, L. N.; Kuznetsova, T. V.; Semenova, N. A. Influence of moisture on the stability of soil organic matter and plant residues. Eurasian. Soil. Sci. 2009, 42, 1241-8.

49. Polyudova, T. V.; Antipieva, M. V. Microbial Ecology: Textbook; Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, Perm State Agro-Technological University named after academician D.N. Pryanishnikov; IPC “Prokrost”: Perm, 2024. https://www.cnshb.ru/content/2025/04455134.pdf (accessed 2025-01-26).

50. Ding, J.; Yu, S. Integrating soil physicochemical properties and microbial functional prediction to assess land-use impacts in a cold-region wetland ecosystem. Life. 2025, 15, 972.

51. Zhang, S.; Zheng, Q.; Noll, L.; Hu, Y.; Wanek, W. Environmental effects on soil microbial nitrogen use efficiency are controlled by allocation of organic nitrogen to microbial growth and regulate gross N mineralization. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 304-315.

52. Carvalho, M. L.; Maciel, V. F.; Bordonal, R. D. O.; et al. Stabilization of organic matter in soils: drivers, mechanisms, and analytical tools - a literature review. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo. 2023, 47, e0230130.

53. Gurkova, E. A.; Sokolov, D. A. Influence of texture on humus accumulation in soils of dry steppes of Tuva. Eurasian. Soil. Sc. 2022, 55, 90-101. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134/S1064229322010069 (accessed 2026-01-30).

54. Matyshak, G. V.; Tarkhov, M. O.; Ryzhova, I. M. et al. Temperature sensitivity of СO2 efflux from the surface of palsa peatlands in Northwestern Siberia as assessed by transplantation method. Eurasian. Soil. Sc. 2021, 54, 1028-37.

55. Tarkhov, M. O.; Matyshak, G. V.; Ryzhova, I. M.; et al. Temperature Sensitivity of peatland soils respiration across different terrestrial ecosystems. Eurasian. Soil. Sc. 2024, 57, 1616-27.

56. Maslov, M. N.; Maslova, O. A.; Kopeina, E. I. Biochemical stability of water-soluble organic matter in tundra soils of the Khibiny Mountains during postfire succession. Eurasian. Soil. Sc. 2021, 54, 316-24.

57. Buzin, I. S.; Makarov, M. I.; Malysheva, T. I.; Kadulin, M. S.; Koroleva, N. E.; Maslov, M. N. Transformation of nitrogen compounds in soils of mountain tundra ecosystems in the Khibiny. Eurasian. Soil. Sci. 2019, 52, 518-25.

58. Ali, R. S.; Poll, C.; Kandeler, E. Dynamics of soil respiration and microbial communities: Interactive controls of temperature and substrate quality. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 60-70.

59. Kim, D.; Park, H. J.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.; Hong, S. G.; Kim, E.; Lee, H. Temperature sensitivity of Antarctic soil-humic substance degradation by cold-adapted bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 265-75.

60. Bracho, R.; Natali, S.; Pegoraro, E.; et al. Temperature sensitivity of organic matter decomposition of permafrost-region soils during laboratory incubations. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2016, 97, 1-14.

61. Gentsch, N.; Wild, B.; Mikutta, R.; et al. Temperature response of permafrost soil carbon is attenuated by mineral protection. Glob. Change. Biol. 2018, 24, 3401-15.

62. Ren, S.; Ding, J.; Yan, Z.; et al. Higher temperature sensitivity of soil C release to atmosphere from northern permafrost soils as indicated by a meta-analysis. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2020, 34, e2020GB006688.

63. Alekseev, I. I.; Abakumov, E. V.; Shamilishvili, G. A.; Lodygin, E. D. Heavy metals and hydrocarbons content in soils of settlements of the Yamal-Nenets autonomous region. Gigiena. i. Sanitaria. 2016, 95, 818-21. https://colab.ws/articles/10.18821/0016-9900-2016-95-9-818-821 (accessed 2026-01-30).

64. Zharikova, E. A. Assessment of heavy metals content and environmental risk in urban soils. Bull. Tomsk. Polytech. Univ. Geo. Assets. Eng. 2021, 332, 164-173.

65. Moskovchenko, D. V. Biogeochemical properties of the soils of Messoyakha River basin (Tazovsky district of Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Area). Tyumen. State. Univ. Her. Nat. Resour. Use. Ecol. 2016, 2, 8-21.

66. Bechina, I. N.; Popova, L. F.; Vasilyeva, A. I.; Korobitsina, Y. S. Accumulation and redistribution of heavy metals in soils of Novodvinsk City. Nauchnyi. Dialog. 2013, 3, 8-23. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/nakoplenie-i-pereraspredelenie-tyazhelyh-metallov-v-pochvah-g-novodvinska (accessed 2026-01-26).

67. Moskovchenko, D. V.; Romanenko, E. A. Biogeochemical features of landscapes of the Nadym region of YANAO. Bull. Nizhnevartovsk. State. Univ. 2022, 4, 122-36. https://vestnik.nvsu.ru/en/nauka/article/112314/view (accessed 2026-01-30).

68. Sazykin, I.; Khmelevtsova, L.; Azhogina, T.; Sazykina, M. Heavy metals influence on the bacterial community of soils: a review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 653.

69. Guo, H.; Nasir, M.; Lv, J.; Dai, Y.; Gao, J. Understanding the variation of microbial community in heavy metals contaminated soil using high throughput sequencing. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 144, 300-306.

70. Li, S.; Zhao, B.; Jin, M.; Hu, L.; Zhong, H.; He, Z. A comprehensive survey on the horizontal and vertical distribution of heavy metals and microorganisms in soils of a Pb/Zn smelter. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123255.

71. Abakumov, E.; Kimeklis, A.; Gladkov, G.; et al. Microbiome of abandoned soils of former agricultural cryogenic ecosystems of central part of Yamal Region. Czech. Polar. Rep. 2022, 12, 232-45.

72. Trifonova, T. A.; Kurochkin, I. N.; Kurbatov, Y. N. Heavy metals in soils of various functional zones of urbanized territories: assessment of the content and environmental risk. Theor. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 2, 38-46.

73. Golubeva, O. Y.; Alikina, Y. A.; Brazovskaya, E. Y.; Vasilenko, N. M. Hemolytic activity and cytotoxicity of synthetic nanoclays with montmorillonite structure for medical applications. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1470.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].