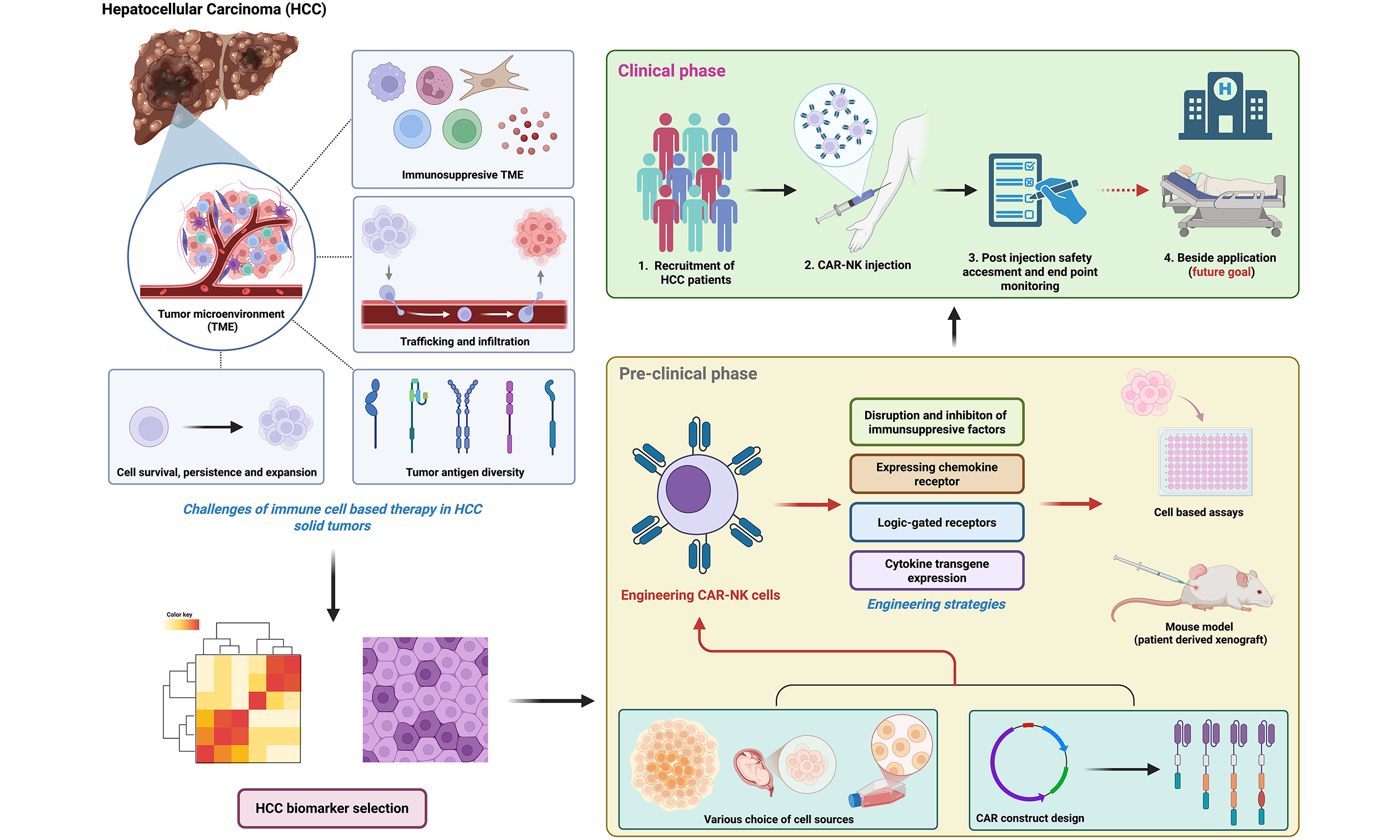

Emerging potential of CAR-NK cell therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: current advances and translational challenges

Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer (CAR-NK) therapy represents an emerging new direction in fighting against cancer. In recent years, it has attracted significant attention, largely due to its notable safety advantages over CAR-T cell therapy and its potential for reduced side effects. In this article, we will review the recent preclinical advances and translational challenges in CAR-NK therapy for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Several preclinical studies have successfully demonstrated that targeting HCC-associated tumor antigens such as glypican-3 and cluster of differentiation 147 (CD147) could exert a strong anti-tumor efficacy. However, only a few studies have entered the clinical stage, with none having progressed to late-phase trials. The clinical translation of CAR-NK in HCC is mainly hindered by significant challenges, including the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, inefficient tumor trafficking, tumor heterogeneity, and poor persistence of infused cells. To overcome these barriers, researchers have been exploring different innovative strategies such as disrupting the transforming growth factor-β signaling, engineering homing chemokine receptors, developing multi-specific CARs, and enhancing persistence with cytokine support (e.g., interleukin-15). Further ongoing research is important to optimize the CAR constructs and identify effective combination approaches to enhance the overall treatment efficacy.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer is among the most prevalent types of human cancer. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it was the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with an incidence of 860,000 and 760,000 deaths, respectively, in 2022[1]. Primary liver cancer (PLC) is classified into several subtypes, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and combined hepatocellular–intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, with HCC being the dominant subtype, accounting for more than 80% of all PLC cases[2]. The global incidence of HCC has been rising, particularly in regions with high rates of hepatitis B and C infections, which are regarded as the primary etiological factors[3]. Other risk factors contributing to the development of HCC include alcoholic liver diseases, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and exposure to aflatoxins, a type of toxin produced by mold that can contaminate food supplies[3]. The underlying pathophysiology often involves chronic liver inflammation and cirrhosis, which create an environment conducive to malignancy[4]. The current treatment options for HCC depend on the stage of the disease and the patient’s liver function. In the early stage, surgery and liver transplantation are the only preferred options, offering the potential for long-term survival[5]. In cases where curative treatment is no longer feasible, locoregional therapies such as radiofrequency ablation and transarterial chemoembolization are employed to control tumor growth[6]. For advanced-stage HCC, systemic therapies are required. Sorafenib and Lenvatinib are the most commonly used first-line targeted therapies, acting as multi-kinase inhibitors that block tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis and have demonstrated high efficacy. Both drugs mainly target vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)-related pathways, inhibiting signaling pathways such as rapidly accelerated fibroblast/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Raf/MEK/ERK) to further suppress tumor cell proliferation[7,8]. Regorafenib, a second-line oral multi-kinase inhibitor for HCC patients previously treated with sorafenib, has a similar mechanism of action, targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), TEK receptor tyrosine kinase (TIE2), and other kinases involved in tumor growth and angiogenesis[9]. Recent studies have emphasized immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as promising therapeutic strategies for HCC, harnessing the body’s immune system to fight cancer, particularly through targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. PD-1 inhibitors such as nivolumab enhance anti-tumor immune responses by blocking the PD-1 interaction with its ligands on T cells[10,11], while CTLA-4 inhibitors, such as ipilimumab, promote T cell activation by inhibiting the CTLA-4 checkpoint[12]. Investigations into the combined use of these inhibitors such as nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy have shown increased efficacy compared to monotherapy, as this dual blockade facilitates a more robust immune response, potentially improving tumor control and survival rates in HCC patients[13]. However, the limited survival benefits and associated side effects of these treatments underscore the urgent need for innovative strategies to enhance outcomes for HCC patients.

Cell-based immunotherapies have become a powerful new strategy to fight cancer more precisely. By genetically modifying a patient’s own T cells to detect and eliminate cancer, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy has shown impressive results in treating blood cancer. However, serious toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity, have made it difficult to treat solid tumors such as HCC[14]. These resulting physiological phenomena have inspired researchers to explore other types of immune cells that can serve as alternative choices. CAR-natural killer (NK) cell therapy is one of these that is receiving much attention for HCC. The innate anti-tumor capabilities of NK cells, which can identify and destroy aberrant cells without prior sensitization, are harnessed by CAR-NK cells. Since they are not linked to the severe CRS or neurotoxicity that frequently complicates CAR-T cell therapy, they have a significantly safer and superior profile, which is a significant advantage in the context of HCC[14]. Additionally, they may offer a more accessible treatment option because they can be used as an “off-the-shelf” product derived from healthy donors. Given this profile, the potential of CAR-NK cells to overcome the limitations of current HCC immunotherapies is becoming increasingly apparent.

THE FOUNDATION OF CAR-NK CELL THERAPY

The biology of natural killer cells

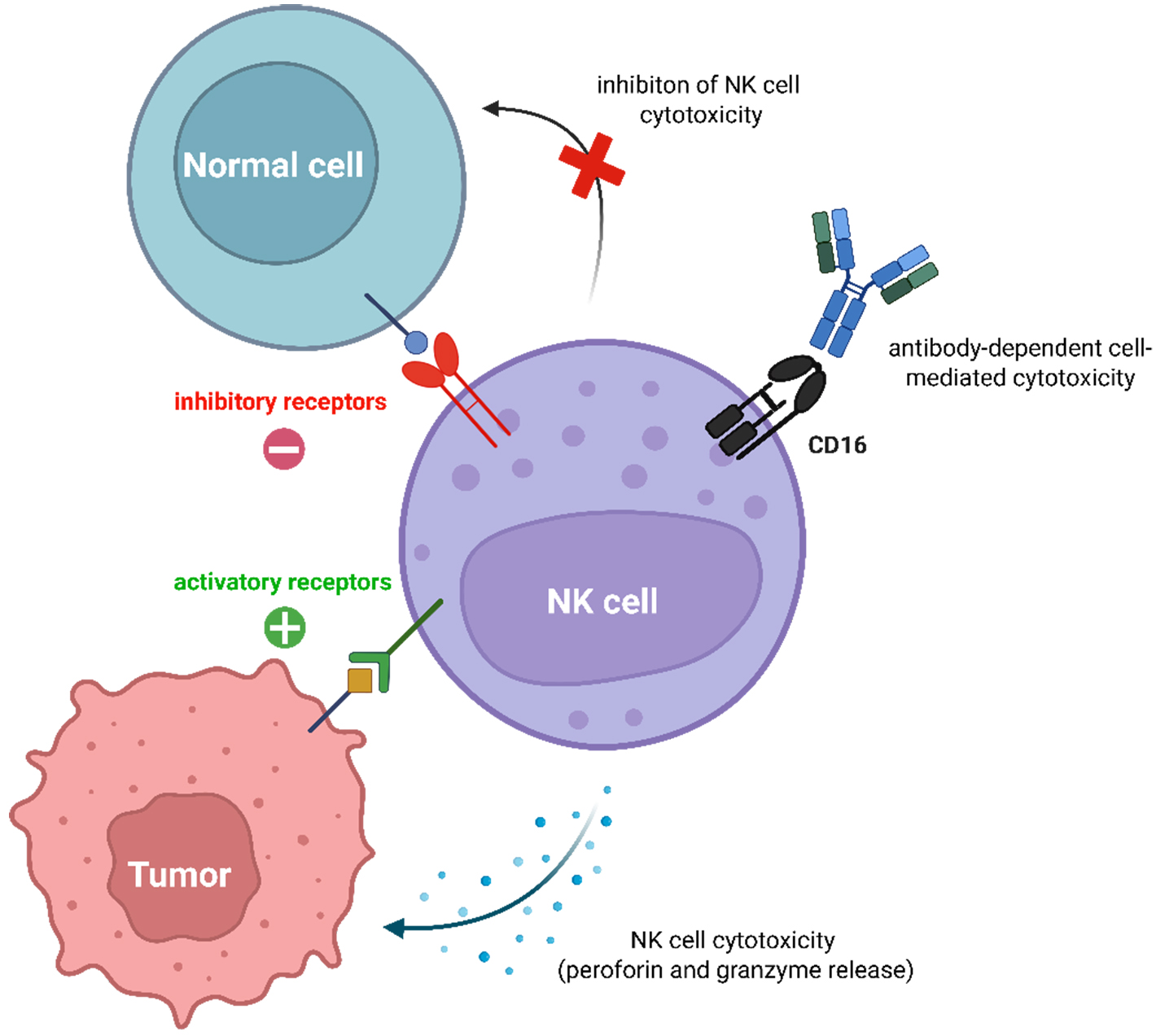

NK cells are large granular lymphocytes of the innate immune system that are primarily involved in antitumor immunity and host defense [Figure 1][15]. They are typically characterized by the expression of cluster of differentiation (CD)56 and CD16. These markers distinguish two major subsets: the CD56brightCD16+/- population, which specializes in releasing immunoregulatory cytokines such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and the more abundant CD56dimCD16high subset, which is highly cytotoxic and mediates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) via CD16, as shown in black [Figure 1][16,17]. Their clinical relevance, especially for “ready-to-use”, also known as “off-the-shelf” cell therapies from donors, comes from their ability to quickly remove cancer cells without prior sensitization. This function is controlled by a balance of signals from activating and inhibitory receptors[18,19]. Inhibitory receptors, indicated in red [Figure 1], such as natural killer cell receptor 2A (NKG2A), killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, two Ig domains and long cytoplasmic tail 1 (KIR2DL1), and CD96, recognize self-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules expressed on healthy cells and transmit an inhibitory “do not kill” signal[20-22]. Tumor or infected cells that downregulate MHC-I to evade T cells lose this inhibitory signal and become vulnerable to NK cell attack, a concept known as “missing-self” recognition[23]. Moreover, activating receptors such as natural killer group 2, member D (NKG2D), natural cytotoxicity triggering receptor (NKp)30, and NKp46, as indicated in green [Figure 1], bind to stress-induced ligands upregulated on target cells, delivering a positive signal that promotes NK-cell-mediated killing[24-26]. Furthermore, the primary mechanisms of NK cell cytotoxicity are the directed release of perforin and granzymes to induce cell death, and the secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α[27]. The critical role of these effector molecules is demonstrated by a study showing that Natural Killer Cell Engagers (NKCEs) depend on their function for anti-tumor efficacy[28]. NKp46 receptor engagement by NKCEs triggered perforin/granzyme-mediated apoptosis, which was suppressed by perforin inhibition. Such engagement potently stimulated IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion, which were found to be necessary for tumor clearance and establishing long-term protectivity[28].

NK cells are large granular lymphocytes of the innate immune system that are primarily involved in antitumor immunity and host defense [Figure 1][15]. They are typically characterized by the expression of cluster of differentiation (CD)56 and CD16. These markers distinguish two major subsets: the CD56brightCD16+/- population, which specializes in releasing immunoregulatory cytokines such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and the more abundant CD56dimCD16high subset, which is highly cytotoxic and mediates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) via CD16, as shown in black [Figure 1][16,17]. Their clinical relevance, especially for “ready-to-use”, also known as “off-the-shelf” cell therapies from donors, comes from their ability to quickly remove cancer cells without prior sensitization. This function is controlled by a balance of signals from activating and inhibitory receptors[18,19]. Inhibitory receptors, indicated in red [Figure 1], such as natural killer cell receptor 2A (NKG2A), killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, two Ig domains and long cytoplasmic tail 1 (KIR2DL1), and CD96, recognize self-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules expressed on healthy cells and transmit an inhibitory “do not kill” signal[20-22]. Tumor or infected cells that downregulate MHC-I to evade T cells lose this inhibitory signal and become vulnerable to NK cell attack, a concept known as “missing-self” recognition[23]. Moreover, activating receptors such as natural killer group 2, member D (NKG2D), natural cytotoxicity triggering receptor (NKp)30, and NKp46, as indicated in green [Figure 1], bind to stress-induced ligands upregulated on target cells, delivering a positive signal that promotes NK-cell-mediated killing[24-26]. Furthermore, the primary mechanisms of NK cell cytotoxicity are the directed release of perforin and granzymes to induce cell death, and the secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α[27]. The critical role of these effector molecules is demonstrated by a study showing that Natural Killer Cell Engagers (NKCEs) depend on their function for anti-tumor efficacy[28]. NKp46 receptor engagement by NKCEs triggered perforin/granzyme-mediated apoptosis, which was suppressed by perforin inhibition. Such engagement potently stimulated IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion, which were found to be necessary for tumor clearance and establishing long-term protectivity[28].

Figure 1. Mechanisms of NK cells on cell recognition. NK cell cytotoxicity is controlled by the balance of signals from activating and inhibitory receptors. Activating receptors recognize stress- or tumor-specific ligands on target cells, triggering the release of cytotoxic granules (perforin and granzymes). Inhibitory receptors engage with MHC class I molecules on healthy cells, delivering signals that prevent NK cell activation and thus protecting normal tissue from immune attack. Additionally, NK cells mediate ADCC by recognizing antibody-coated target cells via their CD16 receptor, which binds to the Fc portion of IgG antibodies, leading to potent activation and killing of the target cell. Created in BioRender. Tong, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/hcqmq9n. NK: Natural killer; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; ADCC: antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; CD16: cluster of differentiation 16; Fc: fragment crystallizable region; IgG: immunoglobulin G.

Safety issues of CAR-T cell therapy and the emergence of CAR-NK cells

CAR cell therapy is an innovative therapeutic strategy that involves engineering patients’ immune cells to kill tumors. CAR is an artificial receptor protein that has been modified to give the immune cell the ability to target cells with a specific antigen[14]. In this technology, T cells are the primary cell type used in therapy, which is often referred to as CAR-T cells. Currently, CAR-T and other CAR immune cell therapies are predominantly restricted to non-solid tumors, particularly hematologic malignancies. As of 2024, there are six U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved CAR-T cell therapies and all of them are designated for the treatment of blood cancers[29]. Notably, there remains a significant gap in the availability of FDA-approved CAR therapies for solid tumors, including HCC. The current developmental progress has been unexpectedly slow and appears to remain in the early discovery and preclinical phases, largely due to the complex environment and landscape in solid tumors compared to non-solid tumors. Numerous reports indicate that CAR-T cell therapies have led to a number of safety concerns, including significant side effects in patients. CRS is one of the most prominent concerns, a potentially life-threatening inflammatory response caused by the rapid release of cytokines that regulate immunity and inflammation[30]. CRS is primarily characterized by fever, fatigue, and respiratory insufficiency, alongside elevated serum cytokine levels[31]. Patients often exhibit unexpectedly high levels of cytokine release, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, due to excessive immune stimulation following CAR-T cell therapy, resulting in a cytokine storm[31]. This phenomenon occurs alongside increased recruitment of other immune cells, such as macrophages engaged through CD40-CD40L co-stimulation, which together promote cytokine release necessary for CRS induction and contribute to a severe inflammatory response[32]. In a 2020 review of 35 studies on hematologic malignancies, it was found that approximately 20% of the 1,000 patients treated with CD19 CAR-T cell therapy for leukemia experienced severe CRS[33]. The high incidence of CRS in patients is a significant concern, as it can result in life-threatening conditions and considerably diminish the overall efficacy of treatment. Another major challenge following CAR-T cell therapy is the induction of neurotoxicity, often manifesting as immune-cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), which is linked to CRS[34]. This neurological complication can occur after CAR-T treatment, leading to symptoms such as coma, seizures, and tremors due to excessive immune cell activation and inflammation within the central nervous system (CNS)[35]. Consequently, activated endothelial cells increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier, allowing cytokines to infiltrate and hijack the CNS. In a study of 800 patients, those with blood cancer had approximately a 20% incidence of neurotoxic effects after receiving CAR-T cell therapy[33]. In contrast, CAR-NK cells are considered a safer alternative. Crucially, they do not typically cause the aforementioned side effects, including severe CRS, neurotoxicity, or graft-versus-host disease (GvHD)[36]. They are a promising cellular platform for solid tumor immunotherapy due to their excellent safety profile, which stems from their innate immune biology, as well as the possibility of “off-the-shelf” allogeneic use from sources such as peripheral blood, umbilical cord blood, or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), making them more convenient and accessible compared to autologous T cells.

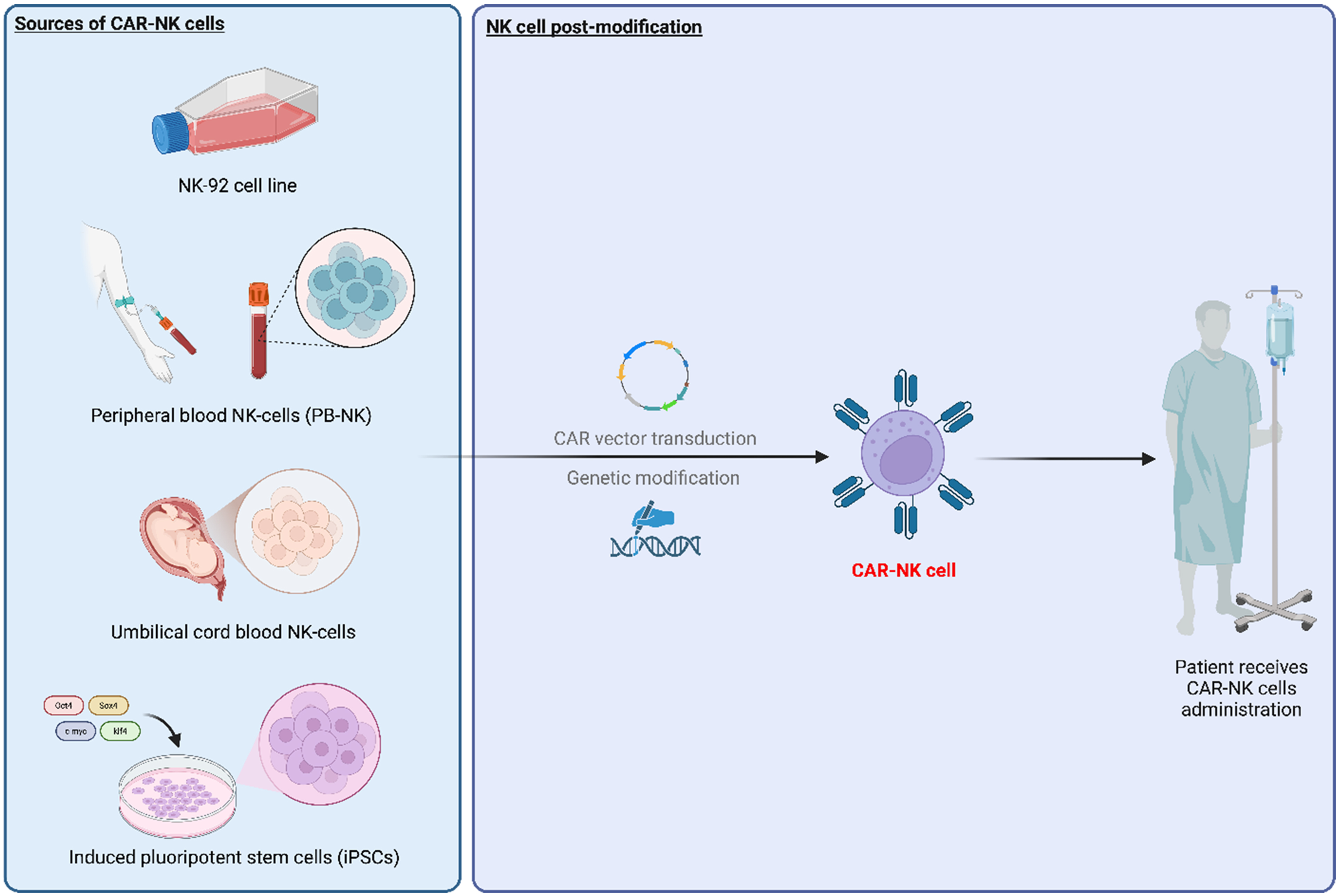

Sources of CAR-NK cells

In recent years, CAR-NK cells have emerged as a promising alternative to CAR-T cell therapy, mainly due to their remarkable advantages. Although not yet fully developed for clinical use, they are, in principle, considered a safer option compared to CAR-T cells[37]. Most importantly, CAR-NK cells do not exhibit CRS, neurotoxicity, or GvHD[37]. In research settings, various types of NK cells are used [Figure 2], with the NK-92 cell line being the most commonly used for NK cell research, particularly in cancer studies. NK-92 was originally extracted from the blood of a lymphoma patient in 1992, and this cell line is distinguished by its increased cytotoxicity, characterized by a high expression of activating receptors and notably low levels of inhibitory receptors[38]. However, since it was originally engrafted from cancer patients, irradiation was needed to ensure the safety, which simultaneously lowers their persistence and shortens their lifespan[39]. Furthermore, NK-92 cells lack antigen diversity, including the absence of the CD16 receptor for enhancing NK cell activity through ADCC[40]. Another commonly used source for producing CAR-NK cells is peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which include peripheral blood NK cells (PB-NK) as one of their subtypes. PB-NK cells are mainly characterized as CD56dim CD16+ cells and can be isolated from either healthy donors or the patients themselves[41]. Unlike T cells that could cause GvHD by hijacking and attacking the recipient due to the interaction with MHC proteins, NK cells primarily focus on balancing activation and inhibitory signals rather than recognizing specific antigens presented by MHC molecules, as they do not express MHC[42]. This makes PB-NK cells suitable for “off-the-shelf” preparation, ensuring they are always ready for CAR-NK cell production. Umbilical cord blood (UCB) also emerged as a source of CAR-NK cells. UCB is rich in immature, highly proliferative NK cells that can be efficiently expanded ex vivo. A key advantage of UCB is its naturally low T-cell content, which facilitates NK cell isolation and further minimizes the risk of contaminating T cells causing GvHD in an allogeneic setting[43]. These cell banks provide a readily available source for generating standardized, allogeneic CAR-NK products. Moreover, the use of iPSCs also serves as an alternative for CAR-NK cell treatment. iPSCs were initially generated in 2006 by making use of retroviruses to introduce four main transcription factors, octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4 (OCT3/4), SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2), kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) and myc proto-oncogene protein (c-MYC), into somatic cells, which enable the reprogramming of somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells[44]. The key benefit of iPSCs is their ability to proliferate indefinitely. This characteristic ensures a steady supply of uniform cells, making them an excellent option for large-scale, ready-to-use applications[45]. Furthermore, iPSCs represent a highly engineerable platform, from which a single iPSC line can be genetically modified to carry a CAR and other beneficial traits, such as cytokine expression or knockout of checkpoint genes, before being differentiated into large quantities of uniform, potent CAR-NK cells, ensuring batch-to-batch consistency that is challenging to achieve with donor-derived sources[46].

Figure 2. Key steps in creating “off-the-shelf” CAR-NK cells. The process initiates with the selection of a starting cell population based on different considerations, which can be an established NK cell line (NK-92), primary NK cells isolated from donor blood or umbilical cord blood, or NK cells differentiated from engineered iPSCs. These progenitor cells undergo a critical genetic modification phase where a CAR construct is introduced, enabling specific tumor antigen recognition. The engineering process often includes additional enhancements, for instance, the constitutive expression of IL-15 to support cell survival or the knockout of inhibitory receptors. Finally, in vitro and in vivo tests will be performed before entering the clinical phase to evaluate the therapy in patients. Created in BioRender. Tong, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/40bqe2r. CAR-NK: Chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer; NK: natural killer; CAR: chimeric antigen receptor; iPSCs: induced pluripotent stem cells; IL-15: interleukin-15.

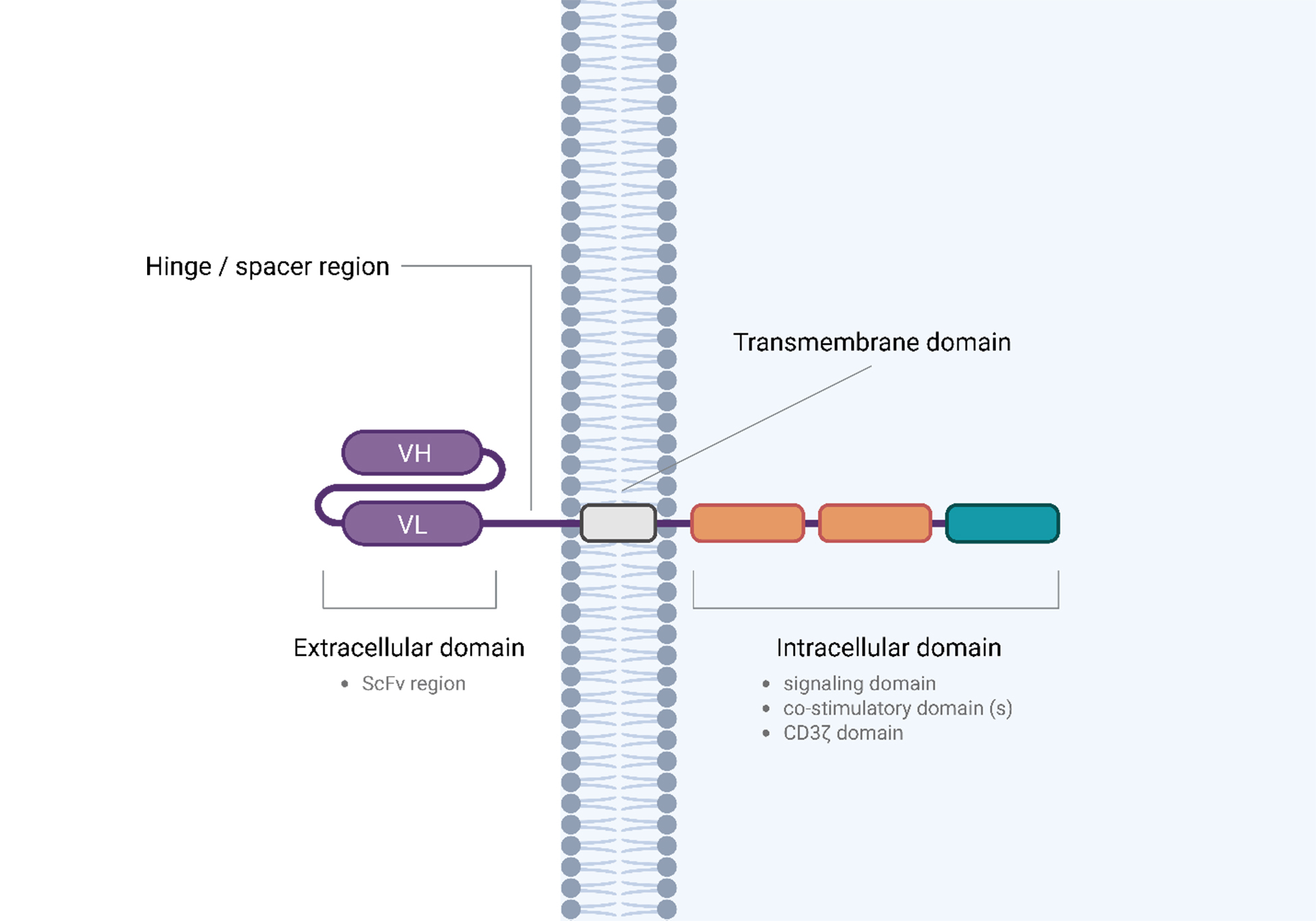

Structure and design of CAR-NK cells

CAR-NK cells adopt a design similar to that of CAR-T cells, using the same conceptual framework for the CAR construct, which mainly consists of the extracellular domain, hinge region, transmembrane domain and intracellular domain [Figure 3]. For the extracellular domain, a single-chain fragment variable (ScFv), derived from part of an antibody, targets the tumor antigen[47]. The hinge region links the extracellular domain to the transmembrane domain, as shown by the purple line in Figure 3; it provides the necessary flexibility and stability for CAR expression when the receptor interacts with tumor antigens[47]. The majority of CAR-NK cells use derivatives of CD8α to serve as the hinge domain, as it is one of the most popular choices[48]. Increasing evidence from CAR-T cell research indicates that CAR design and length may influence functional activity. A study comparing CD19 CAR-T cells with short versus long spacer domains in the hinge region revealed that the shorter spacer facilitates more effective tumor elimination and enhances overall in vivo efficacy[49]. This suggests that the spacer length significantly influences CAR cell performance. The transmembrane domain serves as an anchor, stabilizing the CAR structure within the cell membrane[47]. Common choices include the transmembrane regions of CD8α, CD28, or CD3ζ. The selection can influence CAR stability and expression levels. For instance, the CD28 transmembrane domain may enhance overall CAR surface expression compared to CD8α[49]. The intracellular domain is the most critical component, as it governs cell signaling events following CAR binding to tumor antigens. This domain contains both stimulatory and co-stimulatory domains, as illustrated in orange in Figure 3. The key distinction among the first to fifth generations of CAR cells lies in the varying combinations of subdomains that regulate the activation of these signaling pathways. Among all five generations [Figure 4], all of them contain the CD3ζ chain as the essential signaling domain[50]. In the first generation, the intracellular domain consists only of CD3ζ, shown in green in Figure 3, and contains immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs). These ITAMs are phosphorylated by the protein tyrosine kinase Lck, and the phosphorylated ITAMs then serve as docking sites for zeta-chain-associated protein kinase 70 (ZAP-70), initiating downstream signaling pathways that activate the cytotoxic functions of CAR-NK cells[51]. Building on the design of first-generation CARs, second-generation CARs incorporate an additional costimulatory signal in addition to the CD3ζ chain. The inclusion of domains such as CD28 or tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 9 (TNFSF9 or 4-1BB) provides crucial secondary activation signals that could enhance cellular proliferation, persistence, and cytokine production capacity[52]. The choice of costimulatory domain significantly influences the cell’s metabolic programming and functional profile. CD28 provides a potent, rapid effector response, while 4-1BB promotes oxidative metabolism and is associated with enhanced persistence and a memory-like phenotype, which may be particularly advantageous for solid tumors such as HCC[53]. Third-generation CARs were developed to further amplify activation signals by incorporating two costimulatory domains (e.g., CD28 and 4-1BB) in tandem with the CD3ζ signaling domain[54]. The rationale is that synergistic signaling from multiple costimulatory pathways could lead to superior NK cell activation, expansion, and persistence compared to second-generation constructs[54]. Preclinical studies have shown that third-generation CARs can indeed exhibit enhanced anti-tumor activity in some models[55]. However, a significant problem is that the increased signaling potency can also accelerate NK cell exhaustion and terminal differentiation, potentially limiting their long-term efficacy and increasing the risk of toxicity[56]. This has led to a more advanced approach towards their clinical development compared to second-generation designs. Fourth-generation CARs, also known as the “armored” CARs, represent a strategic shift from simply enhancing direct cytotoxicity to modifying the tumor microenvironment (TME)[57]. These cells are engineered to express transgenic immunomodulatory cytokines, such as IL-12, upon CAR activation, as depicted in red in Figure 4[57]. The localized, constitutive secretion of these cytokines serves a dual purpose: it enhances the persistence and function of the CAR immune cells themselves, and it recruits and activates endogenous immune cells - such as innate immune cells and T cells - to mount a coordinated anti-tumor response against antigen-negative cancer cells[58]. For example, IL-12 secretion has been shown to reverse TME immunosuppression by reprogramming macrophages and inhibiting regulatory T cells (Tregs), thereby creating a more favorable environment for CAR cells[59]. Finally, the fifth-generation CARs, also known as “universal cytokine-redirected” CARs, further refine the armored concept by incorporating an inducible cytokine signaling module to enhance downstream signaling activation. These constructs merge the activation signals from the CAR itself with those from a cytokine receptor, such as the IL-2 receptor β chain, which contains a signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-binding motif[60]. The construction was achieved through engineering a cytoplasmic domain of the IL-2Rβ chain fragment into the intracellular region of the CAR, alongside the CD3ζ and a costimulatory domain [Figure 4]. When CAR was engaged, the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway (JAK)-STAT signaling pathway was switched on[60]. This signaling not only amplifies the canonical CAR-driven cytotoxic and proliferative signals but also promotes a potent, sustained anti-tumor response and enhances the in vivo persistence and survival of the CAR cells, potentially reducing the dependency on exogenous cytokine support[60]. With this design, CAR cells are then able to create a self-sustaining, hyperactive cell population specifically within TME.

Figure 3. Structural components of a typical CAR construct. A CAR consists of four main domains: the extracellular single-chain variable fragment (scFv, shown in blue) for antigen recognition, the hinge/spacer region (purple line) for structural flexibility, the transmembrane domain (gray) anchoring the CAR in the cell membrane, and the intracellular signaling domain containing CD3ζ (green) and costimulatory domains (orange). Created in BioRender. Tong, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/1vze2a6. CAR: Chimeric antigen receptor; ScFv: single-chain fragment variable; CD: cluster of differentiation.

Figure 4. The structural evolution across the five generations of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) is defined by progressive enhancements to the intracellular signaling domain, which transitions from a solitary CD3ζ chain in the first generation to incorporate one or more costimulatory domains and finally to the fifth generation CAR, which contains the cytokine receptor signaling motifs, as detailed in the section “Structure and design of CAR-NK cell. Created in BioRender. Tong, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/oem97rz. CD: Cluster of differentiation; CAR-NK: chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer; IL: interleukin; JAK: Janus kinase; STAT: signal transducer and activator of transcription.

Current development status of CAR-NK cells in HCC

The translation of CAR-NK cell therapy from preclinical models to human clinical trials for HCC remains at an early stage. However, in recent years, the number of studies investigating CAR-NK cell therapy for HCC has been growing and shows significant potential to enter the clinical phase. As summarized in Table 1, most available studies are at the preclinical stage, with the majority targeting glypican-3 (GPC3). Additionally, other targets under investigation include CD147, mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (c-Met), and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), with multiple studies using different cell sources including iPSCs, cord blood and the NK-92 cell line. Regarding the current clinical status, two studies have entered early-phase (I/II) clinical trials, each involving small patient cohorts. Primarily, they focus on establishing safety and feasibility and determining the optimal therapeutic dose. The most recent study that has entered the clinical phase is an ongoing trial named the SNETI-301A (NCT06652243) for GPC3+ HCC. The trial incorporates pharmacokinetic endpoints to measure the in vivo persistence and expansion of these iPSC-derived, IL-15-enhanced cells[61-63]. However, the study is still at a very early stage, and no current data on patient outcomes are available. Another study (NCT02839954) has already completed a Phase I/II trial. The trial is a mucin-1 (MUC1)-targeting CAR-pNK cell, and the primary endpoint of this trial was to determine feasibility and safety, which was successfully met. Importantly, the treatment was reported to be well-tolerated, with no observed dose-limiting toxicities, severe Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS), neurotoxicity, or GvHD in the treated cohort. Another recent study that entered the clinical phase is an ongoing SENTI-301A trial (NCT06652243) for GPC3+ HCC.

Summary of clinical and preclinical studies of CAR-NK cells targeting HCC

| NCT number | Clinical status | Target(s) | CAR generation | Model system | Key findings/outcome | Antigen expression details | Primary study endpoints | Ref. |

| NCT06652243 | Clinical (Phase I), recruiting | GPC3 | Not specified | Patients (advanced HCC) | Preclinical experiments have validated the efficacy of the CAR-NK in tumor elimination. Currently proceeding to First-in-human trial (early phase I) to assess safety & feasibility of this allogeneic, off-the-shelf CAR-NK (SENTI-301A) | GPC3 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is overexpressed in HCC which is associated with poor prognosis | Primary outcome measurement focuses on dose-limiting toxicities (DLT) after the first infusion; Incidence and severity of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) related to safety and tolerability | [61-63] |

| NCT02839954 | Clinical (Phase II), completed | MUC1 | 2nd Generation (CD3ζ/4-1BB) | Patients (Advanced HCC) | Early trial demonstrating safety and preliminary anti-tumor activity of allogeneic CAR-pNK cells | MUC1 is a mucin protein that is aberrantly glycosylated in HCC | Primary outcome measurement focuses on adverse events attributed to the administration of the CAR-NK cell infusion by determining the toxicity profile with Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Effects (CTCAE) version 4.0 | [64] |

| NCT05845502 | Terminated before clinical phase I due to failure to recruit volunteers | Not specified | Not specified | Patients (advanced HCC) | Not specified | / | Primary outcome measurement focuses on the incidence rates and severity of AEs. | [65] |

| / | Preclinical | GPC3 | 3rd Generation (CD3ζ/4-1BB/CD28) | Xenograft Mouse Model | Potent, antigen-specific cytotoxicity and tumor growth inhibition in vivo | GPC3 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is overexpressed in HCC which is associated with poor prognosis | / | [66] |

| / | Preclinical | GPC3 | 2nd Generation | Xenograft Mouse Model | Combining radiotherapy enhanced CAR-NK cell recruitment (via CXCL10/11) and cytotoxicity | GPC3 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is overexpressed in HCC which is associated with poor prognosis | / | [67] |

| / | Preclinical | GPC3 | 2nd Generation | In vitro HCC Co-culture only | sPD-L1 in TME suppressed CAR-NK function; anti-PD-L1 antibody (L3C7c-Fc) restored cytotoxicity | GPC3 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is overexpressed in HCC which is associated with poor prognosis | / | [68] |

| / | Preclinical | GPC3 or AFP | 2nd Generation | Xenograft Mouse Model | TGF-β-rich TME inhibited CAR-NK cells; TGFBR2 knockout conferred resistance and enhanced tumor control | GPC3 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is overexpressed in HCC which is associated with poor prognosis | / | [69] |

| / | Preclinical | GPC3 and CD147 | 3rd Generation (SynNotch) | Xenograft Mouse Model | Logic-gated CAR system demonstrated enhanced specificity and potent anti-tumor activity against heterogeneous tumors | GPC3 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is overexpressed in HCC which is associated with poor prognosis | / | [70] |

| / | Preclinical | CD147 | 4th Generation (IL-15) | Transgenic Mouse Model (huCD147) | IL-15 secretion enhanced in vivo persistence and anti-tumor efficacy with minimal toxicity | GPC3 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is overexpressed in HCC, which is associated with poor prognosis. CD147 is a single-chain type I transmembrane glycoprotein that is encoded by the basigin gene. It is highly expressed in HCC, and correlates with poor prognosis | / | [71] |

| / | Preclinical | CD147 | 4th Generation (IL-15) | Transgenic Mouse Model (huCD147) | Combination with an mTOR agonist further improved persistence and cytotoxicity | CD147 is a single-chain type I transmembrane glycoprotein that is encoded by the basigin gene. It is highly expressed in HCC, and correlates with poor prognosis | / | [72] |

| / | Preclinical | c-met | 3rd Generation (CD3ζ/4-1BB/CD28) | Xenograft Mouse Model | Specific lysis of c-Met+ HCC cells and significant suppression of tumor growth in vivo | c-met is a receptor tyrosine kinase and is overexpressed in HCC | / | [73] |

BIOLOGICAL BARRIERS OF CAR-NK CELLS IN THE HCC TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT AND THE RESPECTIVE ENGINEERING IMPROVEMENT STRATEGIES

The immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment

A major obstacle is the immunosuppressive microenvironment in the tumor, as illustrated in Figure 5. The TME represents a complex and dynamic ecosystem surrounding a tumor. Apart from cancer cells, it consists of a mixture of different cell types such as immune cells, fibroblast and endothelial cells, etc.[74]. The TME is supported by the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is a network of molecules and proteins providing structural support to regulate cellular behavior within the tumor. It also contains cytokines that are extracellular signaling molecules affecting tumor progression and immune response[74]. Within the TME, cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and Tregs exhibit immunosuppressive characteristics[74]. MDSCs express arginase-1 - an enzyme that depletes essential amino acids for T cell activity such as L-arginine. This depletion causes downregulation of the CD3-associated ζ chain, ultimately causing cell cycle arrest of T cells by inhibiting cyclin D3 and preventing progression into G1 phase, thereby leading to T cell inactivation[75,76]. Apart from T cells, MDSCs also inhibit NK cell activity. A study found that MDSCs inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity via engagement with NKp30 in HCC patients. In the analysis, both MDSCs and NK cells were isolated from the peripheral blood of HCC patients. The data show that MDSCs reduce NK cell IFN-γ release by approximately 50%, as verified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)[77]. Meanwhile, NK cells re-isolated from the MDSC co-cultures exhibited a reduced lytic function, with a 60% decrease compared to NK cells cultured alone, suggesting that MDSCs exert a suppressive effect on NK cells[77]. Furthermore, when anti-NKp30 was introduced, IFN-γ release and NK cell lytic function increased by 50% and 10%, respectively, under the MDSC-NK co-culture conditions[77]. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) also play an immunosuppressive role against NK cells. Wu et al. (2013) demonstrated that TAMs in HCC mediate NK cell dysfunction via CD48 binding, a receptor highly expressed in HCC tissues. This interaction induced NK cell exhaustion and apoptosis, which was significantly reversed by blocking the CD48 receptor, CD244 (2B4), on NK cells, further restoring cytokine production and reducing cell death, which highlights the CD48/2B4 axis in this immunosuppressive process[78]. In addition to immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are also immunosuppressive regulators. One study found that CAFs in HCC cause NK cell dysfunction, characterized by reduced cytotoxicity and impaired cytokine production. It was discovered that CAFs release prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which deactivate NK cells, thereby creating a favorable environment for tumor progression[79]. Moreover, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) has been shown to be a very important immunosuppressive factor within the TME[80]. The release of TGF-β counteracts the functions of T cells and NK cells. For the impact on CAR-T cell function, TGF-β signaling involves the activation of suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD)2/SMAD3 which further causes an accumulation of SMAD4 complex to regulate the expression of target genes to suppress T cell proliferation and activation[81]. Interestingly, a study on human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-targeting CAR-T has found that artificial expression of SMAD7 could downregulate TGF-β receptor through phosphorylation of receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs) and cause degradation of TGF-β receptor[80]. The resulting modification enhanced CAR-T cytotoxicity and persistence[81]. Furthermore, one study demonstrates that TGF-β significantly reduces IFN-γ production. The study showed that introducing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 inhibits downstream proteins of TGF-β signaling, including TGF-β RII and SMAD2/SMAD3. Under these conditions, IFN-γ release was reduced by 30%, clearly illustrating the inhibitory effect of TGF-β on IFN-γ[82]. Additionally, another study indicates that the TGF-β1 isoform downregulates the surface expression of NKG2D, along with NKp30, which, as previously mentioned, plays a role in MDSC-mediated inhibition of NK cell activity. The data show that TGF-β1 treatment causes an approximate 12-fold decrease in NKp30 transcript levels in a representative NK cell clone and a ~3-fold decrease in a polyclonal population, which correlates with a significant downregulation of this activating receptor[83]. This specific molecular impairment directly compromises the NK cell’s cytotoxic machinery, as the loss of NKp30 along with downregulated NKG2D impairs effective tumor cell killing[83]. This receptor downregulation further impairs NK function, as cytolytic assays show that TGF-β1-conditioned NK cells have significantly reduced killing of immature dendritic cells (iDCs), with residual cytotoxicity largely dependent on the diminished NKp30 pathway[83]. While specific tumor reduction percentages are not provided, this direct evidence of impaired cytotoxicity, alongside the quantification of receptor downregulation, mechanistically explains how TGF-β1-mediated suppression of activating receptors compromises the anti-tumor immunity[83].

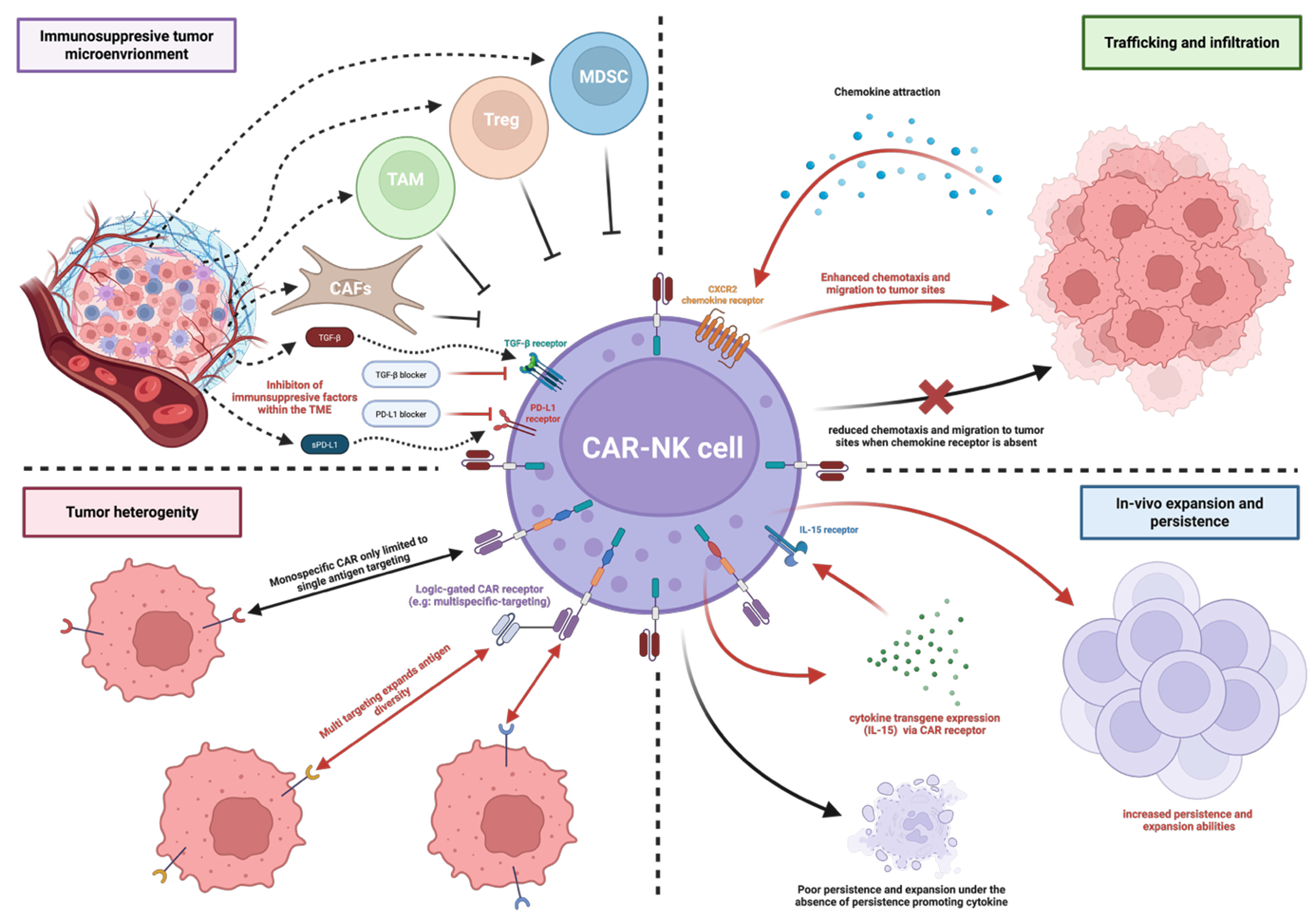

Figure 5. Key challenges and engineering strategies for CAR-NK cells in HCC. Schematic diagram illustrating four major barriers to CAR-NK cell efficacy (black arrows): immunosuppressive TME, inefficient tumor trafficking, tumor heterogeneity, and limited persistence, alongside their corresponding precision-engineered solutions (red arrows). Created in BioRender. Tong, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/wcom6k8. CAR-NK: Chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; TME: tumor microenvironment; MDSC: myeloid-derived suppressor cell; Treg: regulatory T cell; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; CAFs: cancer-associated fibroblasts; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; PD-L1: programmed death ligand-1; sPD-L1: soluble programmed death ligand-1; CXCR2: C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2; IL: interleukin.

Overcoming the immunosuppressive TME

To overcome these obstacles, a recent study provides a direct, powerful strategy to counteract TGF-β-mediated suppression in CAR-NK therapy for HCC. Thangaraj et al. showed that human iPSC-derived NK cells, even those engineered with a CAR targeting GPC3 or AFP, were significantly inhibited by high levels of TGF-β present in HCC TME[69]. Primary data indicate that the cytotoxic effect of HCC cells dropped by approximately 50% after exposure to TGF-β (10 ng/mL) compared to the non-treated groups, also causing ~85%-90% reduction of IFN-γ and TNF-α production and significant downregulation [70%-80% decrease in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)] of key activating receptors such as NKG2D and DNAX Accessory Molecule-1 (DNAM-1). To address this, the researchers genetically engineered iPSC-derived CAR-NK cells to disrupt the TGF-β pathway through the knockout of the TGFBR2 gene[69]. The resulting TGFBR2-knockout CAR-NK cells exhibited dramatically enhanced anti-tumor activity in vitro and in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of HCC[69]. This modification rendered the NK cells completely resistant to TGF-β-mediated suppression[69]. The treatment of transforming growth factor beta receptor 2 (TGFBR2)-knockout CAR-NK cells also led to ~90%-95% reduction in tumor bioluminescent signal and inhibited the tumor growth by over 98% as compared to vehicle controls[69]. This enhanced efficacy directly translates into a significant survival benefit, with over 80% of treated mice surviving to day 35, the end of the study, compared to a 0% survival rate in the vehicle control group[69]. Importantly, these resistant cells showed improved persistence and infiltration within the TGF-β-rich tumor masses, with an approximately 3- to 5-fold increase in in vivo persistence within the TME, leading to sustained tumor control and significantly prolonged survival in mouse models[69]. Beyond TGF-β, another study found that HCC patients have significantly elevated levels of another immunosuppressive factor in the TME, soluble programmed death ligand-1 (sPD-L1)[68]. Serum sPD-L1 levels were significantly elevated in HCC patients compared with healthy individuals, as confirmed by ELISA[68]. sPD-L1 binds to the PD-1 receptor on immune cells, including CAR-NK cells. This interaction inhibits the cytotoxic function of these cells, thereby reducing their ability to attack cancer cells[68]. As data indicate, adding sPD-L1 significantly reduced GPC3-CAR-NK cell cytotoxicity against Huh7 cells by approximately 20%[68]. On the other hand, sPD-L1 also suppressed activation of NK cell degranulation as shown by a reduction in CD107a (degranulation marker) of approximately 5%-10%. Simultaneously, cytokine production was impaired, with IFN-γ and TNF-α release decreased by roughly 40%-45% and 35%-40%, respectively. When a sPD-L1 variant, L3C7c-Fc was introduced to block PD1/PD-L1 axis, promising result was observed as the L3C7c-Fc can reverse the immunosuppressive effect of sPD-L1, restoring cytotoxicity to the baseline levels which enhances CD107a expression by approximately 10% above the suppressed state and also partially restored the cytokine production, these data illustrate that the immune checkpoint blockage can enhance function of CAR-NK cells surviving within an immunosuppressive TME[68].

Inefficient trafficking and infiltration barriers

The success of CAR cell therapies in blood cancers can be largely attributed to their effective localization and infiltration at tumor sites, as they are less likely to encounter physical barriers[84]. CAR therapies for solid tumors encounter significant challenges due to various factors that hinder their ability to migrate to tumors[84]. Among these factors, chemokine dysregulation is one of them, and it is characterized by an increased production of chemokines in tumors that are related to immune-suppressing cell types. Chemokines are chemoattractant cytokines that cause immune cells to be chemotactically attracted and migrate towards one another[85]. In chemokine dysregulation, cancer cells either produce chemokines that attract immunosuppressive cells to the TME to exhibit a pro-tumor effect or cancer cells upregulate chemokines that are not recognized by anti-tumor immune cells without expressing their corresponding receptors[85]. For instance, a study has used RNA sequencing and revealed that CXCR2 ligands including CXCL1-3, CXCL5-6, and CXCL8, have shown a relatively high expression level in HCC cell lines and tumor tissues using xenograft models[86]. Correspondingly, human peripheral T cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in HCC lack the expression of the CXCR2 chemokine receptor, leading to improper cell targeting in tumor sites[86].

Enhancing trafficking and infiltration efficiency

A useful strategy to overcome this barrier involves modulating the TME itself to create a chemotactic gradient for immune cells. One study demonstrates that expression of chemokine receptor CXCR2 together with radiotherapy alters the chemokine profile of HCC tumors which enhances the recruitment and anti-tumor activity of GPC3-targeting CAR-NK cells[67]. To further bridge the linkage between CXCR2 and the TME, the study generated CXCR2-modified CAR-NK92 cells that specifically target GPC3, and the effectiveness of these cells in terms of cytotoxicity and their ability to migrate toward HCC cells was then assessed[67]. The results indicate a significant increase in migration efficiency, with the chemotaxis index rising approximately 2.5-fold compared to control CAR-NK cells when stimulated by HCC cell supernatant[67]. Furthermore, when CAR-NK cells were combined with radiotherapy, in vivo experiments showed promising results. Using a mouse model, a single high-dose radiation of 8 Grays (Gy), combined with CXCR2-armed CAR-NK-92 cells, caused a significant reduction in tumor bioluminescence flux and led to an approximately 80%-85% survival rate[67]. Additionally, the study also revealed that a sub-lethal dose of radiation causes a pro-inflammatory shift in the TME which further triggers the upregulation of NK cell attracting chemokines such as CXCL10 and CXCL11 by approximately 1- and 3-fold, respectively. Both chemokines are ligands for the CXCR3 receptor, which is expressed on NK cells[67]. The residual effects of radiation synergistically upregulate stress ligands such as MICA/B and ULBP1, enhancing recognition and cytotoxicity via the NKG2D receptor on CAR-NK cells. Through the creation of a strong chemokine gradient and the combination with radiotherapy, CAR-NK cells can enhance their infiltration to the tumor site to exhibit their anti-tumor effect against cancer cells[67].

Tumor heterogeneity and antigen escape

CAR-T therapy has shown notable clinical advantages by specifically targeting cancer cells through engineered receptors; however, its effectiveness can be hindered by various factors. One significant challenge is the heterogeneity within tumor populations, in which different cancer cells within the same tumor can express varying levels of target antigens or even downregulate them to evade immune detection[87]. This phenomenon, referred to as antigen escape, is a primary contributor to relapse in targeted immunotherapies and is especially prominent in solid tumors such as HCC owing to their considerable genomic instability and clonal diversity[88]. A study has shown that GPC3 can be shed from tumor cells, leading to increased serum levels, which were observed in 20% of HCC patients, with concentrations ranging from 15 to 65 ng/mL[89]. In vitro experiments indicate that the presence of sGPC3 reduced CAR-T cell cytotoxicity by approximately 20%-30% and caused an approximate 20%-60% decrease in the release of key cytokines such as IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ. In an NOD-scid IL-2Rγ null (NCG) mouse model, the presence of sGPC3 dramatically reduced the efficacy of CAR-T therapy, with only 20% of tumors achieving complete remission, compared to an 87% remission rate in the control group, thereby revealing how sGPC3 facilitates tumor antigen and immune escape[89].

Overcoming tumor heterogeneity through antigen diversity

One promising approach involves engineering CAR immune cells to simultaneously target multiple, non-overlapping tumor-associated antigens. In the context of CAR-T, a study developed an engineered bispecific targeting familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and GPC3 CAR cell, which exhibited significantly greater cytotoxicity compared to monospecific CAR-T targeting[90]. For instance, when treated against cells that co-express both antigens, the bispecific CAR-T cells demonstrated a stronger tumor-killing effect and secreted significantly higher levels of cytokines, including a nearly 2-fold increase in IFN-γ and Granzyme B, compared to single-target CAR-T cells[90]. When tested in vivo settings, bispecific CAR-T cells extended median survival in an aggressive SNU398 model from 25 days (with single-target CAR-T) to 41 days and reduced the tumor volume in mice with near-complete tumor elimination[90]. In addition to bispecific targeting, a study on CAR-NK cells highlighted the potential of using SynNotch logic-gated CAR designs to tackle tumor heterogeneity and enhance the tumor-specific properties of CAR cells[70]. Currently, logic-gated CAR-NK has not yet been comprehensively characterized in HCC, with only limited studies that have focused on CAR-T cells in the HCC landscape or on CAR-NK in other cancers. The study demonstrated the therapeutic potential of targeting CD147, a transmembrane glycoprotein highly expressed in HCC[70]. The findings revealed that anti-CD147 CAR-NK cells mediate potent in vitro cytotoxicity against HCC cell lines, with specific lysis above 80% at an effector-to-target cell ratio of 2.5:1, and significantly suppress tumor growth in PDX models, extending median survival from 42 days in control groups to 63 days in treated mice. The study also provided evidence of cytokine release, showing that CD147-CAR-NK cells produced higher levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ, with increases of roughly 50% and 150%, respectively, upon stimulation with HCC cells, compared to control CAR-NK cells[70]. Importantly, immunohistochemical analysis of clinical HCC specimens indicated a complementary, though not entirely overlapping, expression pattern between CD147 and the canonical HCC antigen GPC3[70]. This partial non-correlation provides a rationale for a combinatorial targeting strategy. Apart from the advantage of “on-target, off-tumor toxicity approach”, the implementation of a CAR-NK cell - capable of dual recognition of GPC3 and CD147 - would target a broader spectrum of the tumor cell population. This mitigates the risk of antigen escape and potentially improves therapeutic durability[70].

Improving persistence and expansion

A primary challenge facing adoptive cell therapies is the limited in vivo persistence of infused cells, which can restrict long-term efficacy and facilitate disease recurrence[91]. This is particularly relevant for NK cells, which inherently possess a more limited lifespan compared to their T cell counterparts[91]. Consequently, a major research direction is to genetically augment CAR-NK cells to promote their sustained survival, expansion, and functional capacity within the host, without compromising safety. An innovative strategy is the genetic modification of CAR-NK cells to enable autocrine cytokine signaling to enhance cell proliferation and survival, including the incorporation of IL-15[92]. IL-15 is crucial for the growth, maintenance, and activation of NK cells, enhancing their survival, multiplication, and capacity to eliminate target cells such as cancer cells[93]. In a preclinical study, researchers developed an anti-CD147 CAR-NK cell targeting HCC, incorporating an IL-15 transgene into the CAR vector. The engineered cells can persist in the tumor tissue for up to two weeks, which was a week longer than their persistence in liver, lung and spleen tissue. Although the findings did not reach statistical significance, a trend was observed in which mice treated with IL-15-equipped CAR-NK cells exhibited a 50% short-term survival rate compared to 0% in the control group, along with a reduction in tumor volume[71]. Another study has explored a combination of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) agonist and CD147-targeting CARs equipped with an IL-15 transgene, which successfully demonstrated improved persistence[72]. Using this approach, researchers found that enabling CD147-IL15-CAR-NK cells to secrete IL-15 significantly boosts their abilities to target tumors. This enhancement is linked to increased activation of lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1, which is essential for establishing the cellular interaction sites necessary for effective immune responses[72]. This strategy has been successfully implemented and shown promise in a more recent study that has entered the clinical trial phase I. A company developed a CAR-NK cell named “SENTI-301A” - an off-the-shelf CAR-NK therapy designed to target GPC3-expressing tumors[61-63]. It is the latest CAR-NK therapy being evaluated in clinical trials for HCC. A key feature of SENTI-301A is its calibrated-release IL-15 (crIL-15)[61-63], which significantly enhances persistence and expansion. The crIL-15 is a unique technology in which IL-15 is released in a controlled manner via a protease expressed by the CAR-NK cell, allowing continuous maintenance of expansion and persistence[61-63]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that SENTI-301A significantly enhances persistence, expansion, and antitumor efficacy in HCC mouse models with Huh7 and HepG2 xenografts[61-63]. SENTI-301A treatment significantly extended median survival to 80 days and 52 days, respectively, compared to 49 days (P = 0.002) and 31 days (P = 0.0385) in vehicle controls, respectively. The release of effector molecules, including elevated levels of Granzyme B and IFN-γ during serial killing assays, supported the improved antitumor function[62]. Additionally, in several rounds of in vitro serial killing assays across various effector-to-target ratios, SENTI-301A showed strong and consistent cytotoxicity, successfully eliminating cancer cells[62].

TRANSLATION POTENTIAL OF CAR-NK CELLS FOR HCC

Translational bottlenecks

The main challenge in the field of CAR-NK research is the development of scalable and cost-effective Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) processes for allogeneic “off-the-shelf” CAR-NK products. Allogeneic products are typically designed for standardization, in contrast to autologous CAR-T therapies. However, this requires a high standard of genetic engineering techniques and cryopreservation of NK cells to make it a promising product under the GMP process[94]. Choosing a source for NK cells - whether it is the NK-92 cell line, peripheral blood, cord blood, or iPSCs - involves considering various factors. Each option has its own advantages and challenges related to how easily it can be produced at scale, how effective it is, and how safe it is for use. One of the main concerns and challenges for NK cells is cryopreservation. Cryopreservation tends to cause significant loss of viability and function of NK cells. For example, some studies have shown that a decline in viable cell recovery post-thaw, with viability dropping as low as 34% after 24 h, and the loss was not prevented by the addition of cytokines such as IL-2[95,96]. Furthermore, the cytotoxic activity of these cells is significantly impaired, with cytotoxicity dropping to very low levels within 24 h post-thaw[95,97]. Most importantly for treating solid tumors, cryopreservation severely impairs NK cell motility, causing a six-fold reduction in the number of cells capable of migrating through a 3D matrix and limiting their ability to infiltrate tumors[97]. The difference between pre-freeze cell counts and the actual viable, functional dose administered creates challenges for reliable dosing and predicting clinical efficacy[98]. Therefore, GMP processes are forced to integrate more labor-intensive and expensive post-thaw recovery steps, such as overnight rest with IL-2, to partially restore function, adding complexity and cost which makes the product harder to scale up[96,99]. Moreover, the “off-the-shelf” allogenic nature of most CAR-NK products falls under a new regulatory category, which poses challenges since many CAR-NK therapies for various cancers are considered pioneering studies. Regulatory agencies such as the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) have extensive experience with autologous cell therapies (e.g., CAR-T), some of which are already approved and available on the market. However, allogeneic products still present unique challenges due to their unprecedented nature[100,101]. Large-scale manufacturing requires a significant investment in the beginning. Most importantly, due to the lack of robust clinical data compared with autologous CAR-T therapies, regulatory oversight is currently more challenging[100]. Key concerns include the potential for allo-rejection, in which the recipient’s immune system may recognize and eliminate donor-derived cells, limiting their persistence[102]. Additionally, although the risk of GvHD is low with purified NK cells, long-term follow-up is still needed to ensure there are no hidden risks or unexpected issues. Establishing consistent quality standards for a living therapy grown and modified outside the body is also challenging. While challenges remain for CAR-NK cells, various strategies could mitigate their downsides. For example, allo-rejection could, in principle, be addressed by ablating HLA molecules and inducing NK cells to overexpress inhibitory ligands; however, more clinical data are needed to justify and validate this approach[102]. Efforts must be made to develop improved regulatory pathways to facilitate the transition of CAR-NK therapies into the clinical setting and ultimately to the market.

Clinical translation considerations

The success of CAR-NK cell therapy will depend on its effective translation from the laboratory to clinical settings. This process primarily requires careful consideration of three key aspects: patient selection, delivery methods, and biomarker-based efficacy monitoring. Given the tumor heterogeneity concerns of HCC, treatment decisions will need to be guided by an in-depth understanding of both the tumor and the patient’s overall condition[103]. Biomarker identification, such as detecting common target antigens - for example, GPC3 or CD147 - that are highly expressed in a tumor biopsy, is an important initial step to ensure the therapy effectively engages the targeted cells. Although initial trials typically enroll patients with advanced, treatment-resistant HCC, their severely immunosuppressed environments may limit the effectiveness of even engineered modified cells. Additionally, understanding a patient’s unique immune characteristics - for instance, the levels of immunosuppressive factors such as TGF-β in their blood - could help predict treatment response and allow for better personalization of therapy[104]. Apart from this, consideration should also be given to the stage of the disease and the liver’s residual function. Once the appropriate patients are selected, the next concern is determining the optimal method for delivering CAR-NK cells to the tumor site. The most commonly used delivery method for CAR therapy is intravenous (IV) infusion, which is employed by all currently FDA-approved CAR-T cell therapies targeting blood cancers[105]. In the most recent clinical trial of CAR-NK therapy targeting HCC, SN301A (NCT06652243) also employed IV infusion for delivery, with patients receiving repeated doses weekly for two consecutive weeks[61-63]. Although straightforward, this approach may result in a significant proportion of cells failing to reach the tumor site, particularly for solid tumors such as HCC, which have a more complex TME compared to hematologic malignancies. To enhance precision, more direct delivery routes tailored for liver cancer are currently under investigation, including “hepatic arterial infusion”. The hepatic artery is the closest and main artery for blood supply to the liver; therefore, the infusion method is believed to be more “direct targeting” compared to IV injection, potentially concentrating the engineered CAR cells at the tumor site while minimizing systemic exposure[106]. Early clinical studies with other cell therapies have demonstrated that this intra-arterial approach can significantly enhance tumor infiltration. For example, a study using GPC3-targeted CAR-T cells (NCT05652920) in HCC patients reported an overall response rate of 60%, with hepatic arterial infusion showing higher efficacy compared to intravenous administration[106]. Moreover, to assess therapeutic efficacy, CAR-NK cell tracking can be performed using sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques, such as quantitative PCR (qPCR), to detect the CAR transgene in the blood. This method is particularly useful to measure persistence of CAR-NK Cell within the blood after administration[107]. By extracting the patient’s blood and performing qPCR for the CAR gene, the proliferation and persistence of CAR-NK cells can be monitored from the time of sample collection until consecutive negative results are obtained, as observed in trials such as the CAR-T GPC3 study in HCC (NCT03146234)[108]. Building on this, treatment efficacy can also be assessed through biomarker-based monitoring after CAR-NK infusion, which may include quantification of tumor markers. For example, AFP levels can serve as an indicator of tumor cell death: patients who respond to therapy typically show reduced AFP levels, whereas non-responders exhibit stable or elevated AFP levels[109].

Future perspective and conclusion

HCC continues to be a major global health challenge with an urgent need for more effective and safer therapeutic strategies to improve patients’ survival benefit. With a strong cytotoxic mechanism against cancer cells and no risk of severe CRS, neurotoxicity, or GvHD, CAR-NK cell therapy has become an alternative to CAR-T cells. However, a suppressive TME, poor cell trafficking, tumor heterogeneity, and limited persistence remain the major challenges that CAR-NK cells encounter in solid tumors, hindering their translation from bench to bedside [Figure 5]. Therefore, the preclinical development becomes one of the foundations that determines the fate of CAR-NK cells on HCC in future clinical translation. Looking forward, the development in this field is expected to grow continuously beyond just employing conventional CAR construct designs while approaching towards designing a more sophisticated engineering strategy that could arm NK cells to overcome these obstacles. Apart from focusing on popular HCC markers such as GPC3, an important future direction with novelty could be directly targeting the root of tumor recurrence and therapeutic resistance - the liver cancer stem cell (LCSC) population. LCSCs are characterized by markers, such as CD133, which drive HCC initiation, metastasis, and relapse[110]. Although there are no current studies reporting on CAR-NK targeting LCSC, promising preclinical studies have already demonstrated the efficacy of targeting LCSC markers in the context of CAR-T cells. A study conducted by Wang et al. engineered a dual-targeting CAR-T cell (CoG133) against GPC3 and CD133, demonstrating a significantly enhanced ability to eliminate heterogeneous tumors and prevent relapse compared to single-target approaches targeting GPC3[111]. In vitro and in vivo data support the finding by showing that the CoG133 achieved nearly 90% complete lysis of Huh7 cells and induced complete tumor size reduction in around 40% of Huh7 xenograft mice[111]. CAR immune cells targeting LCSCs have also been investigated in clinical trials. One registered study (NCT02541370) for advanced HCC progressed to the clinical phase with 21 patients treated. The therapy yielded a median overall survival extension of 12 months and a median progression-free survival of 6.8 months, further demonstrating a promising outcome with improved anti-tumor efficacy[112]. Another future direction involves the development of multiplexed and adaptive CAR systems. As mentioned previously, the pioneering study by Tseng et al. established robust evidence for this approach in HCC, demonstrating that a SynNotch-inducible CAR system targeting CD147 can effectively direct cytotoxicity against HCC models while mitigating on-target/off-tumor toxicities[70]. However, building upon this design, future constructs could also consider employing this platform by expanding to more innovative logic gate circuits. For instance, the development of rarely reported strategies, such as trispecific, logic-gated CAR-NK products for HCC. This “all-in-one” multiplexed approach is a powerful strategy to maximize efficacy by simultaneously targeting multiple tumor-associated antigens, thereby addressing the critical issue of tumor heterogeneity. Clear evidence for such trispecific targeting was demonstrated in a preclinical study for blood cancer, where researchers developed a CD19-CD20-CD22–targeting duo CAR-T cell that effectively eliminated antigen-heterogeneous B cell tumors[113]. This work strongly supports the feasibility and potential of expanding this multi-antigen targeting concept to solid tumors such as HCC. Apart from combinatorial antigen recognition approaches, multiplexed CARs can also be equipped with different therapeutic payloads, such as matrix-degrading enzymes, as well as other combinations for TME remodeling. To put this concept into practice, one pioneering study directly enhanced CAR cell function by arming them with enzymes that degrade the tumor matrix[114]. In the study, researchers have developed an innovative “biorthogonal equipping” strategy where CAR-T cells were constructed with a chemical receptor N-azidoacetylmannosamine tetraacylated (Ac4ManNAz) on their cell surface[114]. This allowed for the subsequent covalent attachment of therapeutic payloads after the cells were infused, using a simple click chemistry reaction with another payload that is a dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO)-modified HAase, a chemical that is used to degrade ECM components[114]. The results showed that when both payloads were combined in the CAR-T cells, the cells could degrade tumor hyaluronic acid (HA) and disrupt the ECM, significantly enhancing tumor infiltration, as confirmed in both in vitro and in vivo experiments[114]. A crucial consideration for TME remodeling strategies is the choice of clinical models. Most current studies use xenograft models, which may not fully mimic the liver TME in HCC patients, representing a translational gap that remains unaddressed. Therefore, further studies should focus on more advanced models, such as orthotopic HCC models, which could enable a more comprehensive investigation of TME alterations, including immune evasion, after CAR-NK treatment. Furthermore, an important direction is to directly incorporate metabolic reprogramming into the CAR-NK construct to guarantee that these cells can survive the harsh metabolic environment of HCC. A key strategy involves enhancing mitochondrial fitness to support the sustained energy demands required for robust anti-tumor activity and persistence. This concept is strongly supported by a study showing that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α)-dependent mitochondrial adaptation is necessary to sustain IL-2/IL-15-induced activities in human NK cells[115]. IL-15 signaling, crucial for NK cell survival, drives a metabolic shift toward oxidative phosphorylation - a process dependent on the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α - which promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration[115]. Therefore, a possible future direction is to engineer CAR-NK cells to overexpress PGC-1α. Another approach could focus on preventing harmful lipid accumulation in the TME. For example, a study confirmed that the sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) pathway is significantly dysregulated in HCC tissues, and its alterations are associated with tumor progression and an unfavorable prognosis[116]. Following this logic, another study has shown that tumor-infiltrating NK cells accumulate lipid droplets and that inhibition of the central lipid metabolism regulator SREBP can prevent this accumulation and restore NK cell cytotoxicity[117]. This provides clear evidence that inhibiting SREBP through genetically reprogramming CAR-NKs could possibly resist the lipid-rich liver TME to enhance their overall function. These metabolic reprogramming strategies are promising, as demonstrated by preclinical data; however, a fundamental translational gap remains. The mechanisms governing long-term CAR-NK persistence are poorly understood, and it is still unclear whether a single genetic modification can stably ensure metabolic fitness throughout the entire lifespan of CAR-NK cells in a patient. Besides, combinational approaches with ICIs could also be explored as a future direction, as external factors within the TME can affect NK cell function through checkpoint inhibition. Recent research has demonstrated that serum exosomes from HCC patients carry CD155 and suppress NK cell immune function by regulating T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT)/CD155 pathway[118]. Interestingly, this study showed that blocking TIGIT with an antibody partially restored NK cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production that had been suppressed by HCC-derived CD155-loaded exosomes[118]. This provides a promising mechanistic rationale and critical insight for combining CAR-NK cells with TIGIT blockade and may explain the potential of combining other immune checkpoints with CAR-NK cells to achieve a synergistic effect.

While the clinical landscape for CAR-NK cells in HCC is still in an early stage and associated with uncertainties, it nonetheless holds promise as an ideal cell therapy candidate for CAR-based immunotherapy due to the inherent safety profile and biological properties of NK cells. Currently, ongoing early-phase trials and the rapid evolution of engineering strategies provide strong justification for optimism. At this stage, greater emphasis should continue to be placed on preclinical development to generate more robust evidence before advancing to clinical trials, while also beginning to plan clear protocols for clinical trial monitoring to facilitate bedside translation. With continued research focused on optimizing CAR design, integrating innovative engineering strategies, and identifying optimal combination approaches, CAR-NK cell therapy holds substantial potential to become a foundation for future immunotherapy development in HCC.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The Graphical Abstract was created in BioRender. Tong, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/sheb1al.

Authors’ contributions

Designed and coordinated the study, wrote the manuscript, and finalized the figures: Chu MKC, Tong M

Finalized the manuscript: Tong M

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by grants from Research Grants Council of Hong Kong – Collaborative Research Fund (C4057-24GF) and Theme-based Research Scheme (T12-705-24-R); The Chinese University of Hong Kong - Improvement on Competitiveness in Hiring New Faculties Funding Scheme, Lo Kwee-Seong Biomedical Research Fund (SBS-specific) – Start-up Fund, and Strategic Seed Funding for Collaborative Research Scheme (SSFCRS) 2024-25.

Conflicts of interest

Tong M is a Junior Editorial Board Member of the journal Hepatoma Research. Tong M was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. Liver and intrahepatic bile ducts fact sheet. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/11-liver-and-intrahepatic-bile-ducts-fact-sheet.pdf. [Last accessed on 5 Jan 2026].

2. Rumgay H, Ferlay J, de Martel C, et al. Global, regional and national burden of primary liver cancer by subtype. Eur J Cancer. 2022;161:108-18.

3. Singh SP, Madke T, Chand P. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2025;15:102446.

4. Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16018.

5. Tabori NE, Sivananthan G. Treatment options for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2020;37:448-55.

6. Podlasek A, Abdulla M, Broering D, Bzeizi K. Recent advances in locoregional therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2023;15:3347.

7. Liu L, Cao Y, Chen C, et al. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11851-8.

8. Matsuki M, Hoshi T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Lenvatinib inhibits angiogenesis and tumor fibroblast growth factor signaling pathways in human hepatocellular carcinoma models. Cancer Med. 2018;7:2641-53.

9. Kissel M, Berndt S, Fiebig L, et al. Antitumor effects of regorafenib and sorafenib in preclinical models of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:107096-108.

10. Li Q, Han J, Yang Y, Chen Y. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1070961.

11. Gaudel P, Mohyuddin GR, Fields-Meehan J. Nivolumab use for first-line management of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a real-world cohort of patients. Fed Pract. 2021;38:89-91.

12. El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492-502.

13. Melero I, Yau T, Kang YK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib: 5-year results from CheckMate 040. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:537-48.

14. Zugasti I, Espinosa-Aroca L, Fidyt K, et al. CAR-T cell therapy for cancer: current challenges and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:210.

15. Chen S, Zhu H, Jounaidi Y. Comprehensive snapshots of natural killer cells functions, signaling, molecular mechanisms and clinical utilization. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:302.

16. Nagler A, Lanier LL, Cwirla S, Phillips JH. Comparative studies of human FcRIII-positive and negative natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1989;143:3183-91.

17. Mandelboim O, Malik P, Davis DM, Jo CH, Boyson JE, Strominger JL. Human CD16 as a lysis receptor mediating direct natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5640-4.

18. Kärre K, Ljunggren HG, Piontek G, Kiessling R. Selective rejection of H-2-deficient lymphoma variants suggests alternative immune defence strategy. Nature. 1986;319:675-8.

19. Bern MD, Parikh BA, Yang L, Beckman DL, Poursine-Laurent J, Yokoyama WM. Inducible down-regulation of MHC class I results in natural killer cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2019;216:99-116.

20. Kamiya T, Seow SV, Wong D, Robinson M, Campana D. Blocking expression of inhibitory receptor NKG2A overcomes tumor resistance to NK cells. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:2094-106.

21. Xue TY, He YZ, Zhang JJ, et al. KIR2DL1-HLA signaling pathway: notable inhibition in the cytotoxicity of allo-NK cell against KG1A cell. Clin Lab. 2013;59:613-9.

22. Sun H, Huang Q, Huang M, et al. Human CD96 correlates to natural killer cell exhaustion and predicts the prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2019;70:168-83.

23. Yu Y. The function of NK cells in tumor metastasis and NK cell-based immunotherapy. Cancers. 2023;15:2323.

24. Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, et al. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999;285:727-9.

25. Sivori S, Pende D, Bottino C, et al. NKp46 is the major triggering receptor involved in the natural cytotoxicity of fresh or cultured human NK cells. Correlation between surface density of NKp46 and natural cytotoxicity against autologous, allogeneic or xenogeneic target cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1656-66.

26. Pende D, Parolini S, Pessino A, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of NKp30, a novel triggering receptor involved in natural cytotoxicity mediated by human natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1505-16.

27. Wang R, Jaw JJ, Stutzman NC, Zou Z, Sun PD. Natural killer cell-produced IFN-γ and TNF-α induce target cell cytolysis through up-regulation of ICAM-1. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91:299-309.

28. Gauthier L, Morel A, Anceriz N, et al. Multifunctional natural killer cell engagers targeting NKp46 trigger protective tumor immunity. Cell. 2019;177:1701-1713.e16.

29. Parums DV. A review of CAR T cells and adoptive T-cell therapies in lymphoid and solid organ malignancies. Med Sci Monit. 2025;31:e948125.

30. Frey N, Porter D. Cytokine release syndrome with chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:e123-7.

31. Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Gödel P, Subklewe M, et al. Cytokine release syndrome. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:56.

32. Giavridis T, van der Stegen SJC, Eyquem J, Hamieh M, Piersigilli A, Sadelain M. CAR T cell-induced cytokine release syndrome is mediated by macrophages and abated by IL-1 blockade. Nat Med. 2018;24:731-8.

33. Cao JX, Wang H, Gao WJ, You J, Wu LH, Wang ZX. The incidence of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity of CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy in the patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma. Cytotherapy. 2020;22:214-26.

34. Sterner RC, Sterner RM. Immune effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome in chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:879608.

35. Ursu R, Belin C, Cuzzubbo S, Carpentier AF. CAR T-cell-associated neurotoxicity: a comprehensive review. Rev Neurol. 2024;180:989-94.

36. Balkhi S, Zuccolotto G, Di Spirito A, Rosato A, Mortara L. CAR-NK cell therapy: promise and challenges in solid tumors. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1574742.

37. Liu E, Marin D, Banerjee P, et al. Use of CAR-transduced natural killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:545-53.