Functional cure of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: current therapeutic regimens

Abstract

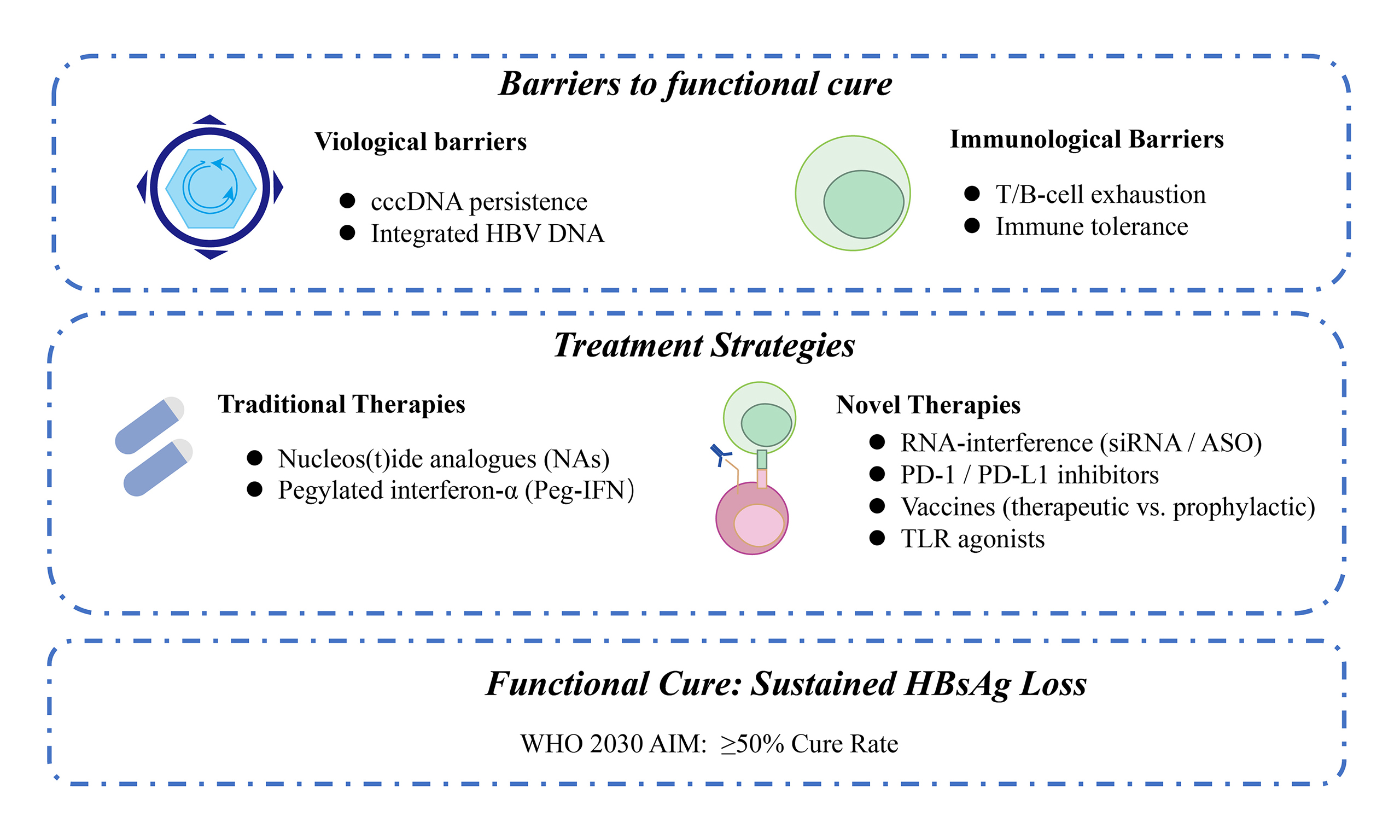

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It is estimated that 254 million people are chronically infected with HBV, with 1.1 million deaths projected in 2025. Functional cure, defined as sustained loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), is important for the prevention of HCC. While nucleos(t)ide analogs maintain viral suppression in over 95% of patients, HBsAg clearance is achieved in only 2%-11%. The functional cure rate with interferon therapy is highly variable in different populations, ranging from 2% to over 40%. Consequently, functional cure remains the primary focus of novel therapeutic development. Here, we analyze the virological and immunological barriers to functional cure and summarize current therapeutic methods. Among these, novel RNA-interference-based therapeutics reduce HBsAg to below 10% of baseline in most patients. However, monotherapy with these agents results in HBsAg loss in fewer than 10% of cases. However, sequential interferon or immunomodulatory agents raise the HBsAg loss to 15%-30%. To achieve the > 50% cure rate likely required for the World Health Organization’s 2030 elimination goals, we analyze promising strategies focused on multi-target combination approaches and precision-medicine frameworks.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains one of the most critical global public-health challenges. In 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 254 million individuals were chronically infected with HBV, resulting in approximately 1.1 million annual deaths due to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1]. The burden remains highly concentrated, with three-quarters of cases located in the Western Pacific (97 million), Africa (65 million) and South-East Asia (61 million)[2]. Universal infant vaccination has reduced early childhood HBV infections below 0.1%. Nevertheless, over 90% of existing chronic infections were acquired perinatally or in early childhood[3]. Without intervention, HBV-related mortality is projected to increase by 39% between 2015 and 2030[4]. In China, for example, 32% of chronically infected men and 9% of women are predicted to succumb to HCC before the age of 75 years[5].

Long-term suppression of HBV replication through antiviral therapy has been proven to significantly reduce the risk of HCC and liver-related mortality, serving as a critical tertiary prevention strategy. Recent studies demonstrated that nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) fail to eradicate the viral covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) and integrated HBV fragments[6-9]. Consequently, fewer than 5% of patients achieve hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss after stopping therapy[6-9]. This low rate represents a critical barrier to functional cure (sustained HBsAg seroclearance off-therapy), defined as sustained HBsAg loss [< 0.05 international units per milliliter (IU/mL)] and undetectable HBV DNA (< 10 IU/mL) for at least 24 weeks off-therapy[10-13]. Ultra-sensitive HBsAg assays (lower limit of detection ≤ 0.005 IU/mL) are increasingly needed to accurately measure profound antigen suppression and predict relapse[14]. Expert Consensus 2.0 outlines a two-stage curative paradigm. The first stage uses small interfering RNA (siRNA) or antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to suppress antigens and reverse immune tolerance. The second stage employs pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN), therapeutic vaccines, or programmed-death-1 (PD-1)/PD-ligand-1 (PD-L1) inhibitors to prime adaptive immunity. Phase II trials (NCT02981602, NCT04225715) of this sequential approach achieved HBsAg seroclearance rates of 15%-30%[15-17]. In this review, we summarize the virological and immunological barriers to functional cure, evaluate combination regimens [Table 1], and propose a framework to achieve ≥ 50% functional-cure rates, a threshold which is likely required to meet WHO 2030 targets.

Therapeutic landscape for CHB functional cure

| Therapeutic category | Mechanism of action | Specific regimen | Primary efficacy endpoints | Efficacy data | Key advantages | Major limitations | Ref. |

| I. Current standard of care | |||||||

| NAs | Competitively inhibit HBV DNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase, terminating viral DNA synthesis and replication | ETV, TDF, TAF | Viral suppression (undetectable HBV DNA), HBsAg clearance | Viral suppression in > 95% of patients; HBsAg clearance in < 5% | High efficacy in viral suppression, reduces HCC risk, improves liver histology | Does not eliminate cccDNA, frequent relapse after cessation, often requires lifelong therapy | [49-57] |

| Peg-IFN | Direct antiviral and immunomodulatory activity, epigenetically suppresses cccDNA transcription | Peg-IFNα, weekly injections | HBeAg loss/seroconversion, HBsAg clearance | HBeAg loss and undetectable HBV DNA in ~30% of HBeAg-positive patients. HBsAg clearance up to 40% in inactive carriers | Finite treatment duration, no lifelong treatment required, potential for sustained immune control | Subcutaneous injection, multiple adverse reactions (flu-like symptoms, depression, etc.) Efficacy depends on baseline HBsAg level and HBeAg status. Not suitable for decompensated cirrhotic patients | [37,62-66,69-72,76] |

| II. Traditional combination strategies | |||||||

| De novo combination (NA + Peg-IFN) | Combines viral suppression of NAs with immune-mediated clearance of Peg-IFN | Simultaneous initiation of NA and Peg-IFN | HBsAg clearance | - | - | No proven advantage over monotherapy or sequential approaches | [82-87] |

| Switch strategy (NAs → Peg-IFN) | Stops NAs and switches to Peg-IFN after virologic suppression to activate immunity | Discontinue NAs, initiate Peg-IFN | HBsAg clearance | HBsAg clearance rates of 8.5%-14% at week 48 in HBeAg-negative patients with baseline HBsAg < 100 IU/mL | Potential for HBsAg clearance | High risk of virologic relapse and clinical hepatitis flare (2%-4%) | [73-76] |

| Add-on strategy (NA + Peg-IFN) | Maintains NAs therapy while adding Peg-IFN for immunomodulation | Continue NAs, add Peg-IFN | HBeAg seroconversion, HBsAg clearance | HBsAg clearance rates of ~7% in HBeAg-positive patients, 20% in those with baseline HBsAg < 1,500 IU/mL | Lower risk of virologic relapse (9% vs. 26%) and hepatitis flare (1.2% vs. 6.8%) compared to switch strategy | Efficacy still depends on baseline HBsAg level. Injection-related side effects, requires monitoring | [77-81] |

| III. Novel antiviral agents | |||||||

| siRNA | Degrades viral mRNA via RNA-induced silencing complex, blocking translation of all HBV proteins | IR-2218 (elebsiran), Xalnesiran, Imdusiran | HBsAg reduction, HBsAg clearance | Monotherapy reduces HBsAg by > 1 log10, but HBsAg loss ≤ 10%, rebound common after cessation | Potent reduction of HBsAg and other viral antigens | Low HBsAg loss rate as monotherapy, antigen rebound | [88-94] |

| ASO | Hybridizes to HBV RNA and recruits RNase H1 to degrade viral transcripts, some have TLR8 agonist activity | Bepirovirsen, 300 mg weekly for 24 weeks | HBsAg clearance | HBsAg loss in 9%-10% of patients after 24 weeks. 16%-25% in those with baseline HBsAg ≤ 3 log IU/mL | Higher monotherapy clearance rate than siRNA. Finite-duration monotherapy can directly elicit functional cure. Effective for HBsAg expressed by integrated DNA | Limited efficacy in patients with high baseline HBsAg, rebound possible | [88,93-98] |

| CAMs | Disrupts HBV capsid assembly/disassembly, preventing pgRNA encapsidation and cccDNA replenishment | JNJ-56136379 | Viral load reduction, HBsAg reduction | Preclinical studies show marked viral load decline, monotherapy rarely achieves functional cure | Lower HBsAg, epigenetically silence cccDNA | Limited efficacy as monotherapy | [100,102] |

| Entry inhibitor | Competitively blocks NTCP receptor on hepatocytes, preventing HBV/HDV entry | Bulevirtide | HBsAg reduction | Modest HBsAg reduction as monotherapy, significant declines when combined with Peg-IFN in co-infected patients | Targets viral entry, valuable in combination | Limited effect on HBsAg alone | [104] |

| NAPs | Interferes with assembly/secretion of subviral HBsAg particles, directly reducing circulating HBsAg | REP 2139 | HBsAg seroconversion | In triple combination with Peg-IFN and tenofovir, HBsAg seroconversion rates ~60% | Potent HBsAg reduction | Limited clinical data, unproven long-term efficacy. Mechanism not fully elucidated | [108] |

| IV. Immunomodulatory therapies | |||||||

| Pattern recognition receptor agonists | Activates innate immune signaling (e.g., TLR pathways), driving type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines | Vesatolimod (TLR7 agonist), Ruzotolimod (TLR7 agonist), Selgantolimod (TLR8 agonist) | HBsAg reduction | Monotherapy yields modest HBsAg reductions or low seroconversion rates | Activates innate immunity and bridges to adaptive immunity | Insufficient to break deep tolerance under high antigen load | [106-109] |

| ICIs | Blocks PD-1/PD-L1 axis to reverse T-cell exhaustion and restore antiviral T-cell function | Envafolimab (anti-PD-L1), Nivolumab (anti-PD-1) | HBsAg clearance | Envafolimab: 21.1% HBsAg clearance in patients with baseline HBsAg < 100 IU/mL. Nivolumab: HBsAg reduction in 11/12 subjects, one HBsAg loss | Revives exhausted T cells, effective in low-antigen settings | Efficacy dependent on low antigen load, safety concerns in some populations | [106] |

| Therapeutic vaccines | Breaks immune tolerance, elicits robust HBV-specific T- and B-cell responses | BRII-179 (HBsAg + Pre-S1 + Pre-S2), VTP-300 (ChAdOx1/MVA vectors) | HBV-specific T-cell responses, HBsAg reduction | Induces HBV-specific CD4+/CD8+ T-cell responses and neutralizing antibodies. Larger HBsAg reduction when combined with siRNA/ICIs | Resets immune memory, designed for chronic infection | Limited efficacy as monotherapy, requires combination | [113,114] |

| Prophylactic vaccines | Prevents infection by inducing neutralizing antibodies | Recombinant HBV vaccines, 0-1-6 month schedule | Protective anti-HBs antibodies | In neonates of HBsAg+/HBeAg+ mothers, vaccine + HBIG reduces chronic carrier rate to 6% vs. 88% in controls | Highly efficacious and safe, primary prevention | Not curative, used for prophylaxis only | [115] |

| Monoclonal antibodies | Neutralizes HBV particles and enhances antigen presentation via Fc engineering | VIR-3434 (Fc-engineered human mAb) | HBsAg reduction | Single doses produce rapid HBsAg drops (~2 log10 IU/mL), but durability limited | Rapid antigen reduction, quickly reduces viral load | Short-lived effect, requires combination regimens | [116] |

| T-cell engineering therapies | Genetically engineers T cells with HBV-specific TCRs or CARs for precise cytotoxicity against infected hepatocytes | TCR-T (targeting HBV core antigen), CAR-T (targeting HBV surface antigen) | Viral replication control | Preclinical and early-phase studies show potential for eradicating viral reservoir | Potential to target and eliminate infected cells | Safety and persistence hurdles,early-stage development | [117,118] |

| V. Novel combination regimens | |||||||

| ASO + NAs combination | ASO lowers HBsAg and viral proteins, NAs suppress replication | Bepirovirsen + ETV/TDF | HBsAg decline or loss | Significant HBsAg reduction or clearance in some NA-experienced patients with acceptable safety | Dual action may reawaken exhausted immunity | Requires further validation in phase III trials | [97] |

| siRNA + Peg-IFN | siRNA depletes antigens, lifting immune suppression; Peg-IFN provides antiviral and immunostimulatory effects | VIR-2218/Xalnesiran + Peg-IFNα | HBsAg clearance | HBsAg loss rates of 15%-23% | Strong synergy, higher functional cure rates | Sequential therapy required | [126,127] |

| ASO → Peg-IFN sequential | ASO reduces antigen load, followed by Peg-IFN to consolidate response and reduce relapse | Bepirovirsen (24 weeks) → Peg-IFN | HBsAg clearance, reduced relapse | Reduces post-treatment relapse and consolidates HBsAg loss | Improves durability of response | Complex sequential regimen | [128] |

| siRNA + therapeutic vaccine | siRNA drives HBsAg to low levels, vaccine mimics acute infection to expand multispecific T and B cells | Imdusiran (AB-729) + VTP-300 | HBsAg clearance | Stronger HBV-specific CD4+/CD8+ T-cell response after siRNA pretreatment | Paradigm of “antigen-down, immunity-up” | Still in early development | [129,134] |

| siRNA + innate agonist | Simultaneously silences viral genes and activates innate immunity (e.g., TLR agonists) | Xalnesiran + Ruzotolimod (TLR7 agonist) | HBsAg decline | Synergistically reduces HBsAg, prolongs RNA silencing effect | Jointly breaks immune tolerance | Optimal dosing and sequencing under investigation | [127,130,131,135] |

| siRNA + ASO combination | Complementary mechanisms: siRNA degrades all viral transcripts, ASOs recruits RNase H1 to cleave HBV RNA | REP 2139-Mg (ASO) + ARB-1467 (siRNA) | HBsAg decline | Safe and well tolerated; induces deeper and more durable HBsAg declines | Complementary action enhances antigen reduction | Awaiting large, stringent RCTs | [125] |

BARRIERS TO FUNCTIONAL CURE

Virological barriers

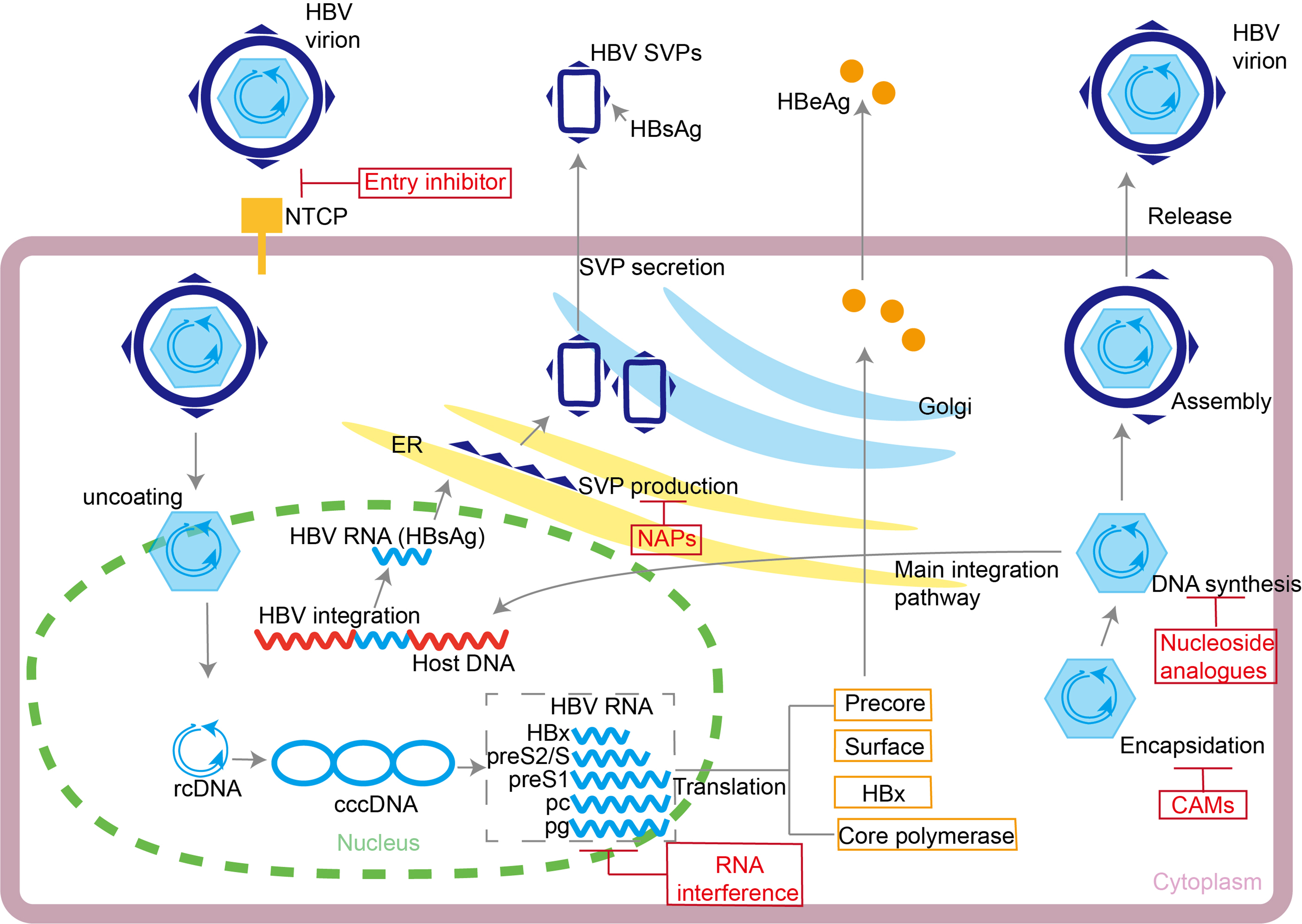

cccDNA serves as the key viral reservoir that sustains lifelong HBV infection. Organized as an epigenetic minichromosome complexed with histones and host factors, cccDNA resides in the hepatocyte nucleus and displays a half-life of weeks to years. Because NAs act only on the reverse transcription of pre-genomic RNA, they do not prevent intracellular recycling of relaxed-circular DNA that continuously replenishes the cccDNA pool[6,7,18-21]. Single-cell sequencing studies confirmed that a low level of transcriptionally active cccDNA persists in the liver under NAs therapy[22]. This persistence explains the high rate of virological relapse after treatment withdrawal. Additionally, the S region of the HBV genome can integrate into the host genome early in infection via non-homologous end joining. These integrated fragments can continuously express HBsAg and constitute one of the main sources of serum HBsAg in hepatitis B e antigen negative (HBeAg-negative) chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients[23-25]. During chronic infection, high levels of HBV DNA and HBsAg establish an antigen-tolerant environment, which impairs adaptive immune responses[26,27]. HBV also evades immune surveillance through genomic mutations. For instance, deletions in the pre-S/S regions can yield false-negative HBsAg tests or facilitate immune escape[28]. The coexistence of cccDNA and integrated DNA in hepatocytes poses a major obstacle to viral eradication, as current therapies do not effectively target both reservoirs[29-31]. To address the virological barriers, therapeutics precisely target multiple key steps of the HBV life cycle [Figure 1].

Figure 1. HBV life cycle. The HBV life cycle and the sites of action of entry inhibitors, NAs, RNAi therapeutic agents, CAMs, and NAPs are shown. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; NAs: nucleos(t)ide analog; RNAi: RNA interference; CAMs: capsid assembly modulators; NAPs: nucleic-acid polymers; NTCP: sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide; SVPs: subviral particles; HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg: hepatitis B e antigen; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; rcDNA: relaxed circular DNA; cccDNA: covalently closed circular DNA.

Immunological barriers

The liver is an immune-tolerant organ, providing a permissive environment for the persistence of HBV. HBV infection can suppress the interferon signaling pathway in hepatocytes, reducing the production of antiviral effector molecules[26,32]. In early infection, HBV barely induces type I or III interferon responses or the expression of interferon-stimulated genes[11,33]. Viral proteins further contribute to immune evasion through multiple mechanisms. For example, non-infectious HBsAg subviral particles can inhibit Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2/3/9 signaling in dendritic cells and monocytes/macrophages. This suppression reduces nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation and interferon (IFN)-α production. HBsAg can also block the NF-κB activation and IFN-α production[34]. Additionally, HBeAg can induce the expansion of intrahepatic regulatory T cells, fostering a local immunosuppressive microenvironment[35].

In CHB, sustained high-level HBsAg induces profound immune tolerance, impairing both humoral and cellular antiviral immunity. The failure to generate anti-HBs (hepatitis B surface antibody) is strongly associated with the inability to achieve functional cure[26,36,37]. Within the adaptive immune system, chronic HBV infection leads to profound exhaustion of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. These cells co-express multiple immune checkpoint molecules and have impaired effector functions[38-40]. Single-cell sequencing studies have revealed that these T cells adopt a terminally exhausted phenotype in the liver microenvironment, which positively correlates with the transcriptional activity of cccDNA[41]. Moreover, persistent high levels of HBsAg can induce thymic clonal deletion, significantly reducing the peripheral pool of HBsAg-specific CD8+ T cells[42]. In B cells, HBsAg-specific B cells exhibit an atypical memory B cell phenotype, which impairs their differentiation into plasma cells and diminishes their capacity to secrete antibodies[43-45]. This vicious cycle of viral persistence, sustained antigen burden, and immune exhaustion represents the major host barrier to achieving a functional cure[11,45-48].

CURRENT TREATMENT STRATEGIES

Mechanism and clinical efficacy of NAs

NAs serve as the first-line antiviral agents and the foundation of CHB management, capable of maintaining viral suppression in over 95% of adherent patients[49]. They competitively inhibit the HBV DNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase, thereby terminating viral DNA synthesis and replication[49,50]. By suppressing HBV DNA levels, NAs reduce HBV-related HCC development, which constitutes their primary therapeutic mechanism[51]. Current international guidelines recommend entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and tenofovir alafenamide as preferred first-line therapies for CHB, given their high and comparable efficacy. Combining ETV with other NAs may further enhance serum HBV DNA suppression[51,52].

Despite effectively suppressing viral replication and improving liver histology, NAs fail to eliminate cccDNA, leading to frequent relapse after cessation[6,8,53-57]. Most patients require lifelong NAs therapy, as virologic relapse is frequent following treatment cessation[58]. Patients with drug-resistant virologic breakthrough have a higher risk of developing HCC than those with sustained virologic response[59]. This indicates that uncontrolled HBV replication persists in some patients despite NAs therapy. The relative efficacy of different NAs in reducing HCC risk remains debated[51,60], while treatment adherence and duration are also critical factors. Therefore, NAs therapy is essentially a long-term, and often lifelong, viral suppression strategy. Its core clinical value lies in maintaining viral suppression to prevent or delay disease progression and to establish a stable baseline for future curative interventions.

Immunomodulatory effects of interferon therapy

Unlike NAs, interferons inhibit viral replication but also enhance host immune responses[47,61]. Peg-IFN exhibits both direct antiviral and immunomodulatory activity, and can epigenetically suppress cccDNA transcription[62-66]. Its longer half-life (80-90 h) and more stable pharmacokinetics compared with standard interferon have made Peg-IFN the preferred clinical formulation[7,37,67,68]. Given these properties, recent research has focused on identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from Peg-IFN therapy. In a cohort study of 190 patients, Peg-IFN treatment significantly reduced liver-related mortality in CHB and compensated cirrhosis, with the best long-term outcomes observed in those achieving HBsAg loss[69]. Peg-IFN induces HBeAg seroconversion and undetectable HBV DNA in approximately 30% of patients, with HBsAg clearance rates reaching up to 40% in inactive carriers[70,71]. One clinical trial enrolled HBeAg-negative patients who had achieved suppressed viremia on NAs therapy[37]. In patients with a low baseline HBsAg level (< 1,500 IU/mL), adding 48 weeks of Peg-IFN significantly increased the HBsAg clearance rate from 2% to 12%. Similarly, in treatment-naïve HBeAg-positive patients, a multicenter randomized trial study (NCT00877760) demonstrated that a sequential strategy of ETV followed by Peg-IFN achieved a higher HBeAg seroconversion rate (16%) than ETV monotherapy did (5%)[72]. However, not all combinations are successful. One clinical trial (NCT01532843) found that TDF plus Peg-IFN induced a greater HBsAg decline but no significant difference in HBsAg clearance at 72 weeks post-treatment compared with TDF monotherapy[73]. These findings underscore that baseline patient characteristics are key determinants of interferon efficacy.

Clinical evidence for combination strategies

To address the limitations of monotherapy, various combination strategies have been developed. These aim to integrate the potent viral suppression of NAs with the immune-mediated clearance induced by interferon. To overcome the limitations of monotherapy, various combination approaches have been explored to synergize the potent viral suppression of NAs with the immune-mediated clearance induced by interferon. The switching strategy entails a transition from NAs to Peg-IFN in patients who have achieved virologic suppression. In HBeAg-negative patients with baseline HBsAg levels below 100 IU/mL, this approach leads to HBsAg clearance rates of 8.5%-14% at week 48. However, the risk of virologic relapse and clinical hepatitis flare is high, especially in HBeAg-positive or advanced fibrosis patients[73-75]. Severe hepatitis flares occur in 2%-4% of cases, limiting broad application[76].

In contrast, the add-on strategy maintains NAs therapy while introducing Peg-IFN. In ETV-suppressed patients, the addition of Peg-IFN significantly increases HBeAg seroconversion and HBsAg decline. Among those with baseline HBsAg levels below 1,500 IU/mL, HBsAg clearance rates reach 20%[77]. In HBeAg-positive patients, the add-on strategy achieves HBsAg clearance rates of approximately 7% of cases. Despite this similar efficacy, the add-on strategy substantially reduced risk of virologic relapse (9% vs. 26%) and hepatitis flare (1.2% vs. 6.8%) compared to the switch strategy, establishing it as the preferred approach in this population[74,78-80]. De novo combination has not proven superior to sequential strategies and is not recommended by current guidelines[81-86].

NOVEL CURATIVE STRATEGIES AND DRUG ADVANCES

RNA-interference-based therapeutics (siRNAs and ASOs)

RNA interference (RNAi), primarily comprising siRNAs and ASOs, suppresses the expression of all HBV proteins by targeting viral messenger RNA (mRNA). Preclinical studies demonstrate their capacity for simultaneous suppression of replication, antigen expression and cccDNA transcriptional activity[87]. RNAi technology targets HBV mRNA and thus prevents synthesis of all viral proteins, including HBsAg, HBeAg and the polymerase[88]. As a potent antiviral approach, RNAi reduces HBsAg by more than 1 log10 IU/mL. However, monotherapy results in HBsAg loss in fewer than 10% of patients and is often followed by rebound[16,89-92].

ASOs degrade target mRNA through the Ribonuclease H1 (RNase H1) pathway. The pivotal phase IIb B-Clear trial (NCT03365947) revealed that 28%-29% of participants achieved HBsAg below the limit of detection at end-of-treatment, with comparable rates in both NA-treated and NA-naïve cohorts. However, only 9%-10% of participants achieved the primary endpoint of sustained HBsAg/DNA loss 24 weeks post-treatment. This result indicated that approximately two-thirds of initial responders experienced virologic rebound[93,94]. This rebound phenomenon underscores the fragility of ASO-induced functional cure without immune consolidation. Among patients with baseline HBsAg ≤ 3 log10 IU/mL, the sustained rate improved to 16%-25%, yet relapse remained dominant[95]. Bepirovirsen also possesses Toll-like receptor 8 (TLR8)-agonist activity that activates innate immunity and augments antiviral responses, providing an immunologic basis for functional cure in a subset of patients[96]. siRNAs and ASOs are both RNA-interference agents, yet their mechanisms diverge. siRNAs load into RNA-induced silencing complex to cleave viral mRNA and block translation of all HBV proteins[92,95], whereas ASOs form DNA–RNA heteroduplexes that recruit RNase H1 to degrade viral mRNA. Certain ASOs additionally stimulate immunity through TLR8[87].

RNAi therapies, including siRNAs and ASOs, potently suppress the HBV transcriptome, thereby reducing viral antigen production and establishing a virological foundation for breaking immune tolerance. Nevertheless, whether using siRNAs or ASOs, monotherapy achieves HBsAg loss in fewer than ten percent of patients, and antigen rebound is frequent after treatment cessation[90,96]. Future therapeutic strategies therefore pursue the combination of RNAi and immunomodulation. A priming phase employing siRNAs or ASOs to reduce HBsAg below 100 IU/mL is followed by Peg-IFN, therapeutic vaccines, or PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to reactivate host immunity and secure durable control, aiming for substantially higher rates of functional cure[16,97].

Nucleocapsid inhibitors

Nucleocapsid inhibitors are among the most representative direct-acting antivirals. They can be classified into two categories based on their mechanism of action: (1) core protein allosteric modulators that induce the formation of aberrant capsids and (2) assembly inhibitors that prevent capsid formation entirely. They disrupt HBV capsid assembly and disassembly, exerting dual inhibitory effects at multiple critical steps of the viral life cycle[98]. These agents act on two fronts: they prevent pre-genomic RNA from being packaged into capsids and block the subsequent reverse transcription step, curtailing the production of new virions. They also inhibit newly formed relaxed circular DNA from reaching the nucleus, thereby blocking replenishment of the cccDNA pool[99]. Beyond direct interference with capsid formation, select capsid assembly modulators (CAMs) promote viral clearance through non-cytopathic mechanisms. Allosteric modulation of core protein activates cellular stress pathways including apoptosis, facilitating selective elimination of the viral reservoir[98]. When combined with other lifecycle-targeting drugs, such as siRNAs or polymerase inhibitors, nucleocapsid inhibitors produce synergistic suppression[99]. Pre-clinical studies show marked viral-load declines, yet monotherapy rarely achieves a functional cure[100]. Multiple candidates have now entered clinical trials as key components of combination regimens[27]. Pairing with RNAi therapeutics or immunomodulators may yield more comprehensive antiviral activity[45]. Next-generation capsid inhibitors lower HBsAg and can epigenetically silence cccDNA[16,96,99].

Entry inhibitors and nucleic-acid polymers

Beyond strategies that directly target viral mRNA, agents that hit other lifecycle nodes - entry inhibitors and nucleic-acid polymers (NAPs) - offer additional avenues. The entry inhibitor Bulevirtide competitively blocks the sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) receptor on hepatocytes, preventing HBV/hepatitis D virus (HDV) entry. Bulevirtide monotherapy has only a modest effect on HBsAg. However, in HBV/HDV coinfection, adding bulevirtide to Peg-IFN drives significant HBsAg decline, highlighting its value in combination[101]. NAPs act later in the lifecycle. Their exact mechanism has not been fully elucidated; however, they appear to interfere with assembly and/or secretion of sub-viral surface-antigen particles, directly and robustly lowering circulating HBsAg. When combined with Peg-IFN and tenofovir in a triple regimen, clinical studies have reported HBsAg seroconversion rates of ~60%, illustrating the considerable promise of this class in curative combinations[102].

Immunomodulators

Pattern-recognition-receptor agonists

Pattern-recognition-receptor (PRR) agonists reshape adaptive immunity by triggering innate signaling cascades such as TLR pathways. TLR-8 agonists, for example, reduce the frequency of terminally exhausted HBV-specific CD8+ T cells and promote the activation of myeloid cells[103,104]. Intracellular sensors TLR-7 and TLR-8 recognize viral RNA motifs. This activates the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)-dependent signaling pathway. This triggers the production of type I IFN and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which not only initiate innate immune responses but also play a key role in bridging to adaptive immunity. In one clinical trial (NCT04225715), sequential administration after a PRR agonist enhanced immunological responses[99]. However, clinical data indicate that monotherapy with Vesatolimod (TLR-7 agonist), Ruzotolimod (TLR-7 agonist), and Selgantolimod (TLR-8 agonist) yields only modest HBsAg reductions or low seroconversion rates[105-107], indicating that innate-immune activation alone is insufficient to break deep tolerance under high antigen load. These agents are therefore considered adjuvant components within combination strategies.

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) reverse T-cell exhaustion by targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is central to the functional shutdown of HBV-specific T cells. Blocking this inhibitory signal reactivates antiviral T-cell function. Preclinical evidence suggests that combining ICIs with antioxidants or phenolic compounds can further restore the activity of HBV-specific CD8+ T-cell in vitro[104]. Early clinical data with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors alone have demonstrated potential efficacy. In a study of envafolimab (anti-PD-L1), 21.1% of patients (baseline HBsAg < 100 IU/mL) achieved HBsAg seroclearance, while an additional 21.0% achieved a significant HBsAg reduction of > 1 log10 IU/mL without clearance at the 24-week endpoint[108]. Another clinical trial of nivolumab (anti-PD-1) in HBeAg-negative, virally-suppressed CHB patients demonstrated acceptable safety, with 11 out of 12 subjects showing HBsAg reductions, including one instance of HBsAg loss accompanied by an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) flare[109]. By preventing PD-1 on T cells from engaging PD-L1 on antigen-presenting cells or hepatocytes, these inhibitors release the inhibitory signal and revive cytotoxicity. HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in chronic infection are terminally exhausted and exhibit high PD-1 expression. PD-1 inhibitors partially recover their interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) secretion and cytolytic capacity, especially when antigen load is first lowered by siRNAs[12,104,109]. These findings provide preliminary evidence that ICIs can contribute to functional cure, particularly in patients with low antigen levels.

Therapeutic and prophylactic vaccines

Therapeutic vaccines are designed to break tolerance and elicit HBV-specific T- and B-cell responses. Next-generation candidates incorporate multiple viral antigens to broaden immune recognition. For example, a virus-like particle-based therapeutic vaccine (BRII-179) contains HBsAg, Pre S1 antigen (Pre-S1), and Pre S2 antigen (Pre-S2), while a therapeutic vaccination (VTP-300) uses chimpanzee adenoviral vector (ChAdOx1)/modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vectors to deliver HBsAg, polymerase, and core antigens. Unlike prophylactic vaccines, they are designed to reset immune memory and are usually combined with ICIs or RNAi drugs[109,110]. When HBsAg has first been lowered, the combination of therapeutic vaccine plus ICI produces a significantly greater decline in HBsAg levels[111].

In the absence of a curative regimen, prophylactic vaccination remains the most effective intervention to reduce global disease burden, mother-to-child transmission, and HCC. Four decades of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and real-world data demonstrate that recombinant HBV vaccines are highly efficacious and safe. The first RCT involved HBsAg+/HBeAg+ mothers, who were randomized to receive either a plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine or a placebo[112]. The trial showed a reduction in the chronic carrier rate: 6% in the vaccine group vs. 88% in the placebo group, corresponding to a protective efficacy of 94%. A subsequent U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) multi-center RCT (NCT04465890) showed that a yeast-derived vaccine lowered the carrier rate to 4.8%, equivalent to plasma vaccine but with no difference in adverse events. This finding paved the way for recombinant vaccines[112]. Until curative therapies become widely available, expanding prophylactic vaccine coverage remains the most cost-effective and fastest route to achieving the WHO 2030 target of a 90% reduction in incident HBV infections.

Monoclonal antibodies and T-cell engineering

Beyond the critical goal of lowering antigen load, a parallel strategy focuses on reconstituting HBV-specific immunity. A prime example is an antibody (VIR-3434), a fragment crystallizable (Fc)-engineered human monoclonal antibody. It potently neutralizes all HBV particles and, via its optimized Fc, enhances antigen presentation to dendritic cells, potentially activating dormant HBV-specific T cells. Single doses produce rapid HBsAg drops (~2 log10 IU/mL)[113]. The therapeutic effect is often transient, necessitating use within combination regimens.

T-cell engineering genetically modifies T cells to target HBV-infected hepatocytes. Autologous or allogeneic T cells are engineered ex vivo with HBV-specific T-cell receptors (TCR-Ts) or chimeric antigen receptors (CAR-Ts), granting precise cytotoxicity against infected hepatocytes. Unlike CAR-Ts that recognize only surface antigens, TCR-Ts can recognize both intracellular HBV-derived peptides presented via major histocompatibility complex class I molecules, offering a broader antigen spectrum and lower detection threshold. In HBV-related HCC, TCR-T therapy has demonstrated objective response rates of 17%-64% and a median overall survival of 33.5 months, significantly surpassing sorafenib (10.7 months)[114]. However, current research in TCR-T and CAR-T therapies for HBV remains in preclinical and early-phase trials. Major obstacles include ensuring safety and achieving durable persistence in vivo. Despite these hurdles, engineered T cells offer a promising strategy for viral reservoir eradication[115].

Novel adjuvant systems and small-molecule HBsAg secretion inhibitors

Next-generation adjuvants focus on enhancing antigen presentation and cytokine production. With natural killer T cells now recognized as key mediators of vaccine responsiveness, adjuvant design should engage both innate and adaptive immunity[116]. Many therapeutic HBV vaccines are protein-based and require adjuvants. While the mechanism of alum remains incompletely defined, it is believed to involve the induction of local inflammation and dendritic cell activation[117]. New approaches employ TLR agonists as pathogen-mimetic motifs, using whole yeast as a natural adjuvant. This strategy requires no external adjuvant, likely because the recombinant hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) carries nucleic acids that act as TLR-3 agonists[118]. Nano-delivery systems, such as polysaccharide emulsions, also provide potent immune stimulation[119,120]. Combinations of TLR agonists with nano-carriers are now being evaluated to optimize the spatiotemporal orchestration of immune activation.

A new class of HBsAg inhibitors has emerged with a different mechanism. a hepatitis B virus expression inhibitor GST-HG131 is a small-molecule di-hydroquinolizinone that functions as an HBsAg expression inhibitor through a host-targeted mechanism different from siRNAs or ASOs[121]. Rather than employing nucleic acids to directly bind HBV transcripts via sequence-specific hybridization, GST-HG131 selectively inhibits the host poly(A) polymerases domain containing 5 and 7. This inhibition prevents mRNA maturation, accelerating its degradation and consequently reducing HBsAg production.

CONVERGENCE OF NOVEL TECHNOLOGIES FOR HBV CURE

The functional cure of CHB necessitates combination therapies that simultaneously target viral replication and host immunity. Current evidence supports several rational combination strategies. Combining antivirals with complementary mechanisms can produce synergistic effects. siRNAs and ASOs both suppress viral transcripts but employ distinct pathways. Early-phase trials (NCT02233075, NCT02876419) indicate that this combination is feasible and can produce profound HBsAg reduction[122]. The combination of NAs and ASOs exerts a synergistic effect through concurrent suppression of viral replication and antigen production. This dual action may disrupt the foundation of immune tolerance. A phase-II RCT (NCT04676724) evaluating bepirovirsen added to ongoing NAs therapy demonstrated significant HBsAg decline or loss in a subset of patients with acceptable safety[97]. This evidence supports ASO-NAs combinations and informs the design of phase-III trials. Another sequential strategy of RNAi followed by immunomodulation has demonstrated strong synergy. This approach first employs siRNAs to deplete viral antigens, thereby alleviating immune suppression. Subsequently, Peg-IFN is administered to exert its dual antiviral and immunostimulatory effects. This approach has achieved HBsAg loss rates of 15%-23% in several clinical trials (NCT04778904)[123,124]. Similarly, sequential therapy with the ASOs bepirovirsen followed by Peg-IFN has been shown to reduce post-treatment relapse and consolidate HBsAg loss, thereby improving durability[125].

The combination of siRNAs and therapeutic vaccines represents a strategy of first reducing antigen load and then boosting immune responses. In this approach, siRNA agents first drive HBsAg to minimal levels. Subsequently, a vectored vaccine is administered to mimic acute-resolving infection[126]. This sequence facilitates the expansion of T and B cells, enabling targeted clearance of residual infected hepatocytes. Combining siRNAs with innate immune agonists, such as the TLR-7 agonist, represents another strategy. This approach simultaneously silences viral genes and activates plasmacytoid dendritic cells to create an interferon-rich microenvironment, jointly breaking immune tolerance[124]. The ability of RNAi-immunomodulator regimens to achieve rapid, deep HBsAg declines, sustain treatment effects, and curb viral rebound has prompted their investigation in multiple active trials (NCT04676724)[97,127,128].

However, emerging evidence underscores that not all combination strategies yield additive effects, and safety concerns warrant careful consideration. Certain combinations, such as pairing siRNAs with CAMs, demonstrated no additive benefit over monotherapy in reducing HBsAg[129]. These findings underscore that the novel therapeutic regimens must be carefully balanced based on mechanistic synergy. Management measures for hepatitis flares or significant adverse events should be established to ensure data validity. If the target population is extended to cirrhosis patients, the drug’s safety and overall benefit-risk in decompensated cirrhosis populations should be evaluated. A key safety concern for anti-HBV drugs is recurrent ALT elevation, which can be classified into three main types. The first type is mediated by the host immune response and is accompanied by decreases in HBV DNA and serological marker levels. The second type is driven by enhanced viral activity. The third type results from adverse drug reactions. Multi-target combination therapy for CHB has emerged as a consensus approach; however, emerging evidence challenges the assumption that all combinations are synergistic.

FUTURE STRATEGIES TOWARD FUNCTIONAL CURE

Despite progress in reducing HBsAg, true functional cure of HBV faces two obstacles: persistence of cccDNA and deep immune tolerance. Future therapeutic strategies must aim to silence or eliminate the cccDNA reservoir and systematically restore HBV-specific immunity. Although RNAi can significantly reduce viral antigens, it does not directly target cccDNA. Therefore, current research is actively exploring combination therapies that couple RNAi with epigenetic silencers or gene editors[130-133].

Personalized immunotherapy and timing will be critical. Evidence indicates that PD-1 inhibitors, TLR agonists, and therapeutic vaccines are most effective under low antigen load. This underscores the principle of reducing antigen to elevate immunity[99,112,114]. Yet optimal dose, sequence and duration remain undefined. Single-cell sequencing, immune-repertoire profiling and systems-immunology models are needed to build predictive algorithms for precision intervention.

As curative strategies evolve, tailoring therapeutic regimens to special populations will become clinical practice. In specific populations, such as those with low-level viraemia, inactive carriers, or patients in the grey zone, Peg-IFN therapy can still achieve HBsAg loss[22,134-139]. Furthermore, initiating treatment in children and adolescents maximizes the probability of a functional cure[140-142]. Those with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatosis liver disease require simultaneous metabolic control to prevent progression[143-150]. In contrast, cirrhotic or HCC patients should avoid Peg-IFN. Their management should emphasize long-term NAs maintenance and intensive surveillance[2,151-153]. Additionally, Peg-IFN-based regimens may be preferable in patients with renal impairment. In cases of HBV/hepatitis C virus (HCV) or HBV/HDV coinfection, management should prioritize HCV eradication while maintaining effective suppression[20,154-163].

Safety and global access pose major challenges. Early agents have been discontinued for toxicity[164], underscoring the need for rigorous long-term safety databases. Furthermore, delivering high-cost innovations to low- and middle-income countries is essential if WHO’s 2030 elimination target is to be met[165,166]. In summary, the era of functional cure has begun; however, actual cure will require multidisciplinary convergence of virology, immunology, gene engineering and public-health policy. With continued innovation and optimization, CHB is set to be transformed from controllable to curable in the coming decade.

CONCLUSION

Functional cure of CHB remains an unmet clinical goal. NAs suppress viral replication but require lifelong therapy. Even after treatment cessation, HBsAg loss occurs in only 2%-11% of patients. The functional cure rate with interferon therapy is highly variable across populations, ranging from 2% to over 40%. RNAi potently lowers HBsAg, yet durable responses are achieved in fewer than 10% of patients. These limitations indicate that antigen reduction alone cannot reverse profound immune exhaustion. Sequential combination strategies, using RNAi followed by immunotherapy, have achieved 15%-30% functional cure rates. Future progress depends on precision immunoprofiling, cccDNA-targeting gene editing, and multi-target drug development. However, approximately 75% of infected individuals live in low-income regions, making the delivery of affordable cures essential to meet WHO elimination targets.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

The work presented here was conducted collaboratively by all authors.

Developed the concept and designed the review: Shi YW, Pu R, Ding YB

Independently screened the full texts of eligible studies to confirm compliance with inclusion criteria, assess study quality, and extract data: Shi YW, Pu R, Ding YB, Liu WB, Li ZS, Zhao JY, Chen YF, Cao GW

Provided overall supervision and revision of the manuscript: Cao GW

All authors contributed to the manuscript drafting and revision, and approved the final version for submission.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the 2030 National Key Project of China (grant number 2023ZD0500100) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82204112).

Conflicts of interest

Cao GW is the Editor-in-Chief of Hepatoma Research, and Liu WB is a member of the Junior Editorial Board of Hepatoma Research. Cao GW and Liu WB were not involved in any stage of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. WHO. Hepatitis B fact sheet. 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. [Last accessed 30 Dec 2025].

2. Feng Y, Fang L, Cao G. Epidemiological characteristics and precise prophylaxis and control of HBV-associated primary liver cancer. Hepatoma Res. 2025;11:5.

3. GBD 2019 Hepatitis B Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of hepatitis B, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:796-829.

4. Hsu YC, Huang DQ, Nguyen MH. Global burden of hepatitis B virus: current status, missed opportunities and a call for action. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:524-37.

5. Chen Y, Lin J, Deng Y, et al. Association of human leukocyte antigen-DR-DQ-DP haplotypes with the risk of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res. 2022;8:8.

6. Tu T, Budzinska MA, Shackel NA, Urban S. HBV DNA integration: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Viruses. 2017;9:75.

7. Tang LSY, Covert E, Wilson E, Kottilil S. Chronic hepatitis B infection: a review. JAMA. 2018;319:1802-13.

8. Hirode G, Choi HSJ, Chen CH, et al.; RETRACT-B Study Group. Off-therapy response after nucleos(t)ide analogue withdrawal in patients with chronic hepatitis B: an international, multicenter, multiethnic cohort (RETRACT-B Study). Gastroenterology. 2022;162:757-71.e4.

9. Yip TC, Wong GL, Chan HL, et al. HBsAg seroclearance further reduces hepatocellular carcinoma risk after complete viral suppression with nucleos(t)ide analogues. J Hepatol. 2019;70:361-70.

10. Anderson RT, Choi HSJ, Lenz O, et al. Association between seroclearance of hepatitis B surface antigen and long-term clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:463-72.

11. Le Bert N, Gill US, Hong M, et al. Effects of hepatitis B surface antigen on virus-specific and global T cells in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:652-64.

12. Salimzadeh L, Le Bert N, Dutertre CA, et al. PD-1 blockade partially recovers dysfunctional virus-specific B cells in chronic hepatitis B infection. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:4573-87.

13. Farag MS, van Campenhout MJH, Sonneveld MJ, et al. Addition of PEG-interferon to long-term nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy enhances HBsAg decline and clearance in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B: multicentre randomized trial (PAS Study). J Viral Hepat. 2024;31:197-207.

14. Kusumoto S, Tanaka Y, Suzuki R, et al. Ultra-high sensitivity HBsAg assay can diagnose HBV reactivation following rituximab-based therapy in patients with lymphoma. J Hepatol. 2020;73:285-93.

15. Wu D, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, et al. Update on the treatment navigation for functional cure of chronic hepatitis B: Expert consensus 2.0. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:S134-64.

16. Yuen MF, Heo J, Jang JW, et al. Safety, tolerability and antiviral activity of the antisense oligonucleotide bepirovirsen in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:1725-34.

17. Hou J, Zhang W, Xie Q, et al.; Piranga Study Group. Xalnesiran with or without an immunomodulator in chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:2098-109.

19. Petersen J, Thompson AJ, Levrero M. Aiming for cure in HBV and HDV infection. J Hepatol. 2016;65:835-48.

20. Prescott NA, Biaco T, Mansisidor A, et al. A nucleosome switch primes hepatitis B virus infection. Cell. 2025;188:2111-26.e21.

22. Meier MA, Calabrese D, Suslov A, Terracciano LM, Heim MH, Wieland S. Ubiquitous expression of HBsAg from integrated HBV DNA in patients with low viral load. J Hepatol. 2021;75:840-7.

23. Wieland S, Thimme R, Purcell RH, Chisari FV. Genomic analysis of the host response to hepatitis B virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6669-74.

24. Lee BO, Tucker A, Frelin L, et al. Interaction of the hepatitis B core antigen and the innate immune system. J Immunol. 2009;182:6670-81.

25. Jiang M, Broering R, Trippler M, et al. Toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses are attenuated in the presence of high levels of hepatitis B virus surface antigen. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:860-72.

26. Wong GLH, Gane E, Lok ASF. How to achieve functional cure of HBV: stopping NUCs, adding interferon or new drug development? J Hepatol. 2022;76:1249-62.

27. Li J, Liu S, Zang Q, Yang R, Zhao Y, He Y. Current trends and advances in antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Chin Med J. 2024;137:2821-32.

28. Gu F, Zeng K, Lan X, et al. Measuring HBV pregenomic RNA may be a potential biomarker to determine HBV functional cure in HIV/HBV-co-infected patients with HBsAg loss. J Med Virol. 2024;96:e29762.

29. Real CI, Lu M, Liu J, et al. Hepatitis B virus genome replication triggers Toll-like receptor 3-dependent interferon responses in the absence of hepatitis B surface antigen. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24865.

30. Xu Y, Hu Y, Shi B, et al. HBsAg inhibits TLR9-mediated activation and IFN-alpha production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2640-6.

31. Deng F, Xu G, Cheng Z, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen suppresses the activation of nuclear factor kappa B pathway via interaction with the TAK1-TAB2 complex. Front Immunol. 2021;12:618196.

32. Zhang JW, Lai RM, Wang LF, et al. Varied immune responses of HBV-specific B cells in patients undergoing pegylated interferon-alpha treatment for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2024;81:960-70.

33. Fang Z, Li J, Yu X, et al. Polarization of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells by hepatitis B surface antigen is mediated via ERK/IL-6/STAT3 signaling feedback and restrains the activation of T cells in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Immunol. 2015;195:4873-83.

34. Qi R, Fu R, Lei X, et al. Therapeutic vaccine-induced plasma cell differentiation is defective in the presence of persistently high HBsAg levels. J Hepatol. 2024;80:714-29.

35. Thimme R, Bertoletti A, Iannacone M. Beyond exhaustion: the unique characteristics of CD8+ T cell dysfunction in chronic HBV infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24:775-6.

36. Xu H, Locarnini S, Wong D, et al. Role of anti-HBs in functional cure of HBeAg+ chronic hepatitis B patients infected with HBV genotype A. J Hepatol. 2022;76:34-45.

37. Huang D, Wu D, Wang P, et al. End-of-treatment HBcrAg and HBsAb levels identify durable functional cure after Peg-IFN-based therapy in patients with CHB. J Hepatol. 2022;77:42-54.

38. Costa JP, de Carvalho A, Paiva A, Borges O. Insights into immune exhaustion in chronic hepatitis B: a review of checkpoint receptor expression. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17:964.

39. Rehermann B, Nascimbeni M. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:215-29.

40. Maini MK, Peppa D. NK cells: a double-edged sword in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Front Immunol. 2013;4:57.

41. Fang Z, Zhang Y, Zhu Z, et al. Monocytic MDSCs homing to thymus contribute to age-related CD8+ T cell tolerance of HBV. J Exp Med. 2022;219:e20211838.

42. Tout I, Gomes M, Ainouze M, et al. Hepatitis B virus blocks the CRE/CREB complex and prevents TLR9 transcription and function in human B cells. J Immunol. 2018;201:2331-44.

43. Bénéchet AP, De Simone G, Di Lucia P, et al. Dynamics and genomic landscape of CD8+ T cells undergoing hepatic priming. Nature. 2019;574:200-5.

44. Zhang Z, Zhang JY, Wang LF, Wang FS. Immunopathogenesis and prognostic immune markers of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:223-30.

45. Fung S, Choi HSJ, Gehring A, Janssen HLA. Getting to HBV cure: the promising paths forward. Hepatology. 2022;76:233-50.

46. Cornberg M, Lok AS, Terrault NA, Zoulim F; 2019 EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference Faculty. Guidance for design and endpoints of clinical trials in chronic hepatitis B - Report from the 2019 EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference. Hepatology. 2019;71:1070-92.

47. Wieland SF, Eustaquio A, Whitten-Bauer C, Boyd B, Chisari FV. Interferon prevents formation of replication-competent hepatitis B virus RNA-containing nucleocapsids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9913-7.

48. Belloni L, Allweiss L, Guerrieri F, et al. IFN-α inhibits HBV transcription and replication in cell culture and in humanized mice by targeting the epigenetic regulation of the nuclear cccDNA minichromosome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:529-37.

49. Gupta N, Goyal M, Wu CH, Wu GY. The molecular and structural basis of HBV-resistance to nucleos(t)ide analogs. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:202-11.

50. De Clercq E, Holý A. Acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: a key class of antiviral drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:928-40.

51. Lim J, Choi J. Optimize nucleot(s)ide analogues’ to prevent hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a lesson from real-world evidence. Hepatoma Res. 2021;7:21.

52. Zheng S, Cao H, Zhang M, et al. A potent GalNAc-siRNA drug, RBD1016, leads to sustained HBsAg reduction and seroconversion in mouse models of HBV infection. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2025;36:102627.

53. Fung S, Kwan P, Fabri M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) vs. emtricitabine (FTC)/TDF in lamivudine resistant hepatitis B: a 5-year randomised study. J Hepatol. 2017;66:11-8.

54. Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-93.

55. Schiff ER, Lee SS, Chao YC, et al. Long-term treatment with entecavir induces reversal of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:274-6.

56. Jeng WJ, Chen YC, Chien RN, Sheen IS, Liaw YF. Incidence and predictors of hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance after cessation of nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2018;68:425-34.

57. Berg T, Simon KG, Mauss S, et al.; FINITE CHB study investigators [First investigation in stopping TDF treatment after long-term virological suppression in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B]. Long-term response after stopping tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in non-cirrhotic HBeAg-negative patients - FINITE study. J Hepatol. 2017;67:918-24.

58. Gara N, Tana MM, Kattapuram M, et al. Prospective study of withdrawal of antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B after prolonged virological response. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:1888-900.

59. Liaw YF. Impact of therapy on the long-term outcome of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;17:413-23.

60. Lin CL, Kao JH. Prevention of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res. 2021;7:9.

61. Li S, Yang M, Ye L, et al. Real-world effectiveness of initial antiviral regimens in children with chronic hepatitis B: an age-stratified cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2025;88:103478.

62. Chen J, Li Y, Lai F, et al. Functional comparison of interferon-α subtypes reveals potent hepatitis B virus suppression by a concerted action of interferon-α and interferon-γ signaling. Hepatology. 2021;73:486-502.

63. Ye J, Chen J. Interferon and hepatitis B: current and future perspectives. Front Immunol. 2021;12:733364.

64. Zhang Y, Zhong X, Xi Z, Li Y, Xu H. Antiviral potential of the genus panax: an updated review on their effects and underlying mechanism of action. J Ginseng Res. 2023;47:183-92.

65. Xia Y, Stadler D, Lucifora J, et al. Interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α produced by T cells reduce the HBV persistence form, cccDNA, without cytolysis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:194-205.

66. Cheng J, Zhao Q, Zhou Y, et al. Interferon alpha induces multiple cellular proteins that coordinately suppress hepadnaviral covalently closed circular DNA transcription. J Virol. 2020;94:e00442-20.

67. Karabay O, Tuna N, Esen S; PEG-HBV Study Group. Comparative efficacy of pegylated interferons α-2a and 2b in the treatment of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1296-301.

68. Wong GL. Updated Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Chronic Hepatitis B-World Health Organization 2024 compared with China 2022 HBV Guidelines. J Viral Hepat. 2024;31 Suppl 2:13-22.

69. Lee SK, Kwon JH, Lee SW, et al. Sustained off therapy response after peglyated interferon favours functional cure and no disease progression in chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2021;41:288-94.

70. Song A, Lin X, Lu J, et al. Pegylated interferon treatment for the effective clearance of hepatitis B surface antigen in inactive HBsAg carriers: a meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:779347.

71. Wang J, Zhang Z, Zhu L, et al. Association of hepatitis B core antibody level and hepatitis B surface antigen clearance in HBeAg-negative patients with chronic hepatitis B. Virulence. 2024;15:2404965.

72. Brouwer WP, Xie Q, Sonneveld MJ, et al.; ARES Study Group. Adding pegylated interferon to entecavir for hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B: a multicenter randomized trial (ARES study). Hepatology. 2015;61:1512-22.

73. Chi H, Hansen BE, Guo S, et al. Pegylated interferon Alfa-2b add-on treatment in hepatitis B virus envelope antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients treated with nucleos(t)ide analogue: a randomized, controlled trial (PEGON). J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1085-93.

74. Li J, Qu L, Sun X, et al. Peg-interferon alpha add-on Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate achieved more HBsAg loss in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B naïve patients. J Viral Hepat. 2021;28:1381-91.

75. Hu C, Song Y, Tang C, et al. Effect of pegylated interferon plus tenofovir combination on higher hepatitis B surface antigen loss in treatment-naive patients with hepatitis B e antigen -positive chronic hepatitis B: a real-world experience. Clin Ther. 2021;43:572-81.e3.

76. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-98.

77. Lim SG, Yang WL, Ngu JH, et al. Switching to or add-on peginterferon in patients on nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B: the SWAP RCT. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:e228-50.

78. Bourlière M, Rabiega P, Ganne-Carrie N, et al.; ANRS HB06 PEGAN Study Group. Effect on HBs antigen clearance of addition of pegylated interferon alfa-2a to nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy versus nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy alone in patients with HBe antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B and sustained undetectable plasma hepatitis B virus DNA: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:177-88.

79. Matsumoto A, Nishiguchi S, Enomoto H, et al. Pilot study of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and pegylated interferon-alpha 2a add-on therapy in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:977-89.

80. Woo HY, Heo J, Tak WY, et al. Effect of switching from nucleos(t)ide maintenance therapy to PegIFN alfa-2a in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0270716.

81. Gill US, Kennedy PTF. Current therapeutic approaches for HBV infected patients. J Hepatol. 2017;67:412-4.

82. Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, et al.; Peginterferon Alfa-2a HBeAg-Negative Chronic Hepatitis B Study Group. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1206-17.

83. Janssen HL, van Zonneveld M, Senturk H, et al.; HBV 99-01 Study Group, Rotterdam Foundation for Liver Research. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:123-9.

84. Ahn SH, Marcellin P, Ma X, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen loss with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus peginterferon Alfa-2a: week 120 analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:3487-97.

85. Wang LJ, Li MW, Liu YN, et al. Natural history and disease progression of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Peking Univ. 2022;54:920-6.

86. Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1-98.

87. Iannacone M, Beccaria CG, Allweiss L, et al. Targeting HBV with RNA interference: paths to cure. Sci Transl Med. 2025;17:eadv3678.

88. Hui RW, Mak LY, Seto WK, Yuen MF. RNA interference as a novel treatment strategy for chronic hepatitis B infection. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:408-24.

89. Wang CC, Kao JH. The role of hepatitis B surface antigen in nucleos(t)ide analogue cessation among Asian chronic hepatitis B patients: friend or foe? Hepatology. 2019;69:1843.

90. Gane E, Lim YS, Kim JB, et al. Evaluation of RNAi therapeutics VIR-2218 and ALN-HBV for chronic hepatitis B: results from randomized clinical trials. J Hepatol. 2023;79:924-32.

91. Gane EJ, Kim W, Lim TH, et al. First-in-human randomized study of RNAi therapeutic RG6346 for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2023;79:1139-49.

92. Thi EP, Ye X, Snead NM, et al. Control of hepatitis B virus with imdusiran, a small interfering RNA therapeutic. ACS Infect Dis. 2024;10:3640-9.

93. Yuen MF, Locarnini S, Lim TH, et al. Combination treatments including the small-interfering RNA JNJ-3989 induce rapid and sometimes prolonged viral responses in patients with CHB. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1287-98.

94. Mak LY, Hui RW, Fung J, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Bepirovirsen (GSK3228836) in chronic hepatitis B infection: an evaluation of phase II progress. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2023;32:971-83.

95. Yuen MF, Lim SG, Plesniak R, et al.; B-Clear Study Group. Efficacy and safety of bepirovirsen in chronic hepatitis B infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1957-68.

96. Yuen MF, Heo J, Kumada H, et al. Phase IIa, randomised, double-blind study of GSK3389404 in patients with chronic hepatitis B on stable nucleos(t)ide therapy. J Hepatol. 2022;77:967-77.

97. Buti M, Heo J, Tanaka Y, et al. Sequential Peg-IFN after bepirovirsen may reduce post-treatment relapse in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2025;82:222-34.

98. Yang L, Gong Y, Liu F, et al. A novel phthalazinone derivative as a capsid assembly modulator inhibits hepatitis B virus expression. Antiviral Res. 2024;221:105763.

99. Phillips S, Jagatia R, Chokshi S. Novel therapeutic strategies for chronic hepatitis B. Virulence. 2022;13:1111-32.

101. Sulkowski MS, Agarwal K, Ma X, et al. Safety and efficacy of vebicorvir administered with entecavir in treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1265-75.

102. Asselah T, Chulanov V, Lampertico P, et al. Bulevirtide combined with pegylated interferon for chronic hepatitis D. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:133-43.

103. Suresh M, Li B, Huang X, et al. Agonistic activation of cytosolic DNA sensing receptors in woodchuck hepatocyte cultures and liver for inducing antiviral effects. Front Immunol. 2021;12:745802.

104. Rossi M, Vecchi A, Tiezzi C, et al. Phenotypic CD8 T cell profiling in chronic hepatitis B to predict HBV-specific CD8 T cell susceptibility to functional restoration in vitro. Gut. 2023;72:2123-37.

105. Wedemeyer H, Aleman S, Brunetto MR, et al.; MYR 301 Study Group. A phase 3, randomized trial of bulevirtide in chronic hepatitis D. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:22-32.

106. Bazinet M, Pântea V, Placinta G, et al. Safety and efficacy of 48 weeks REP 2139 or REP 2165, tenofovir disoproxil, and pegylated interferon Alfa-2a in patients with chronic HBV infection naïve to nucleos(t)ide therapy. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:2180-94.

107. Agarwal K, Ahn SH, Elkhashab M, et al. Safety and efficacy of vesatolimod (GS-9620) in patients with chronic hepatitis B who are not currently on antiviral treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25:1331-40.

108. Gane EJ, Dunbar PR, Brooks AE, et al. Safety and efficacy of the oral TLR8 agonist selgantolimod in individuals with chronic hepatitis B under viral suppression. J Hepatol. 2023;78:513-23.

109. Gane E, Verdon DJ, Brooks AE, et al. Anti-PD-1 blockade with nivolumab with and without therapeutic vaccination for virally suppressed chronic hepatitis B: a pilot study. J Hepatol. 2019;71:900-7.

110. Tak WY, Chuang WL, Chen CY, et al. Phase Ib/IIa randomized study of heterologous ChAdOx1-HBV/MVA-HBV therapeutic vaccination (VTP-300) as monotherapy and combined with low-dose nivolumab in virally-suppressed patients with CHB. J Hepatol. 2024;81:949-59.

111. Wang G, Cui Y, Hu G, et al. HBsAg loss in chronic hepatitis B patients after 24-week treatment with subcutaneously administered PD-L1 antibody ASC22 (Envafolimab): interim results from a phase IIb extension cohort. Hepatology. 2023;78:abs5052. Available from: https://www.ascletis.com/data/upload/ueditor/20211119/5052-C%20Guiqiang%20@%20AASLD%202023%20LB%20Poster%20final.pdf. [Last accessed 30 Dec 2025].

112. Qian J, Xie Y, Mao Q, et al. A randomized phase 2b study of subcutaneous PD-L1 antibody ASC22 in virally suppressed patients with chronic hepatitis B who are HBeAg-negative. Hepatology. 2025;81:1328-42.

113. Ma H, Lim TH, Leerapun A, et al. Therapeutic vaccine BRII-179 restores HBV-specific immune responses in patients with chronic HBV in a phase Ib/IIa study. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100361.

114. Ma P, Jiang Y, Zhao G, et al. Toward a comprehensive solution for treating solid tumors using T-cell receptor therapy: a review. Eur J Cancer. 2024;209:114224.

115. Lugade AA, Bharali DJ, Pradhan V, Elkin G, Mousa SA, Thanavala Y. Single low-dose un-adjuvanted HBsAg nanoparticle vaccine elicits robust, durable immunity. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:923-34.

116. Ushach I, Zhu R, Rosler E, et al. Targeting TLR9 agonists to secondary lymphoid organs induces potent immune responses against HBV infection. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2022;27:1103-15.

117. De Gregorio E, Caproni E, Ulmer JB. Vaccine adjuvants: mode of action. Front Immunol. 2013;4:214.

118. Aguilar JC, Lobaina Y, Muzio V, et al. Development of a nasal vaccine for chronic hepatitis B infection that uses the ability of hepatitis B core antigen to stimulate a strong Th1 response against hepatitis B surface antigen. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:539-46.

119. Pan Y, Liu S, Zhao H, Yu Z, Qi Y, Huang Y. Multi-adjuvant emulsion system stabilized via mannosylated chitosan nanoparticles for subunit vaccine delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;310:143268.

120. Wusiman A, He J, Cai G, et al. Alhagi honey polysaccharides encapsulated into PLGA nanoparticle-based pickering emulsion as a novel adjuvant to induce strong and long-lasting immune responses. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;202:130-40.

121. Li X, Liu Y, Yao H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the novel hepatitis B virus expression inhibitor GST-HG131 in healthy Chinese subjects: a first-in-human single- and multiple-dose escalation trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66:e0009422.

122. Bazinet M, Pântea V, Cebotarescu V, et al. Safety and efficacy of REP 2139 and pegylated interferon alfa-2a for treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis D virus co-infection (REP 301 and REP 301-LTF): a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:877-89.

123. Krebs K, Böttinger N, Huang LR, et al. T cells expressing a chimeric antigen receptor that binds hepatitis B virus envelope proteins control virus replication in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:456-65.

124. Wong GLH, Yuen MF, Kennedy P, et al. LBP-020 Off-treatment antiviral efficacy and safety of repeat dosing of imdusiran followed by VTP-300 with or without nivolumab in virally-suppressed, non-cirrhotic subjects with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). J Hepatol. 2025;82:S79-80.

125. Yuen MF, Lim YS, Yoon KT, et al. VIR-2218 (elebsiran) plus pegylated interferon-alfa-2a in participants with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a phase 2 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:1121-32.

126. Wisskirchen K, Kah J, Malo A, et al. T cell receptor grafting allows virological control of Hepatitis B virus infection. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:2932-45.

127. Hui RW, Fung J, Seto WK, Yuen MF, Mak LY. Emerging therapies for HBsAg seroclearance: spotlight on novel combination strategies. Hepatol Int. 2025;19:704-19.

128. Hui RW, Mak LY, Fung J, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Prospect of emerging treatments for hepatitis B virus functional cure. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:S165-181.

129. Yuen MF, Asselah T, Jacobson IM, et al.; REEF-1 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the siRNA JNJ-73763989 and the capsid assembly modulator JNJ-56136379 (bersacapavir) with nucleos(t)ide analogues for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection (REEF-1): a multicentre, double-blind, active-controlled, randomised, phase 2b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:790-802.

130. Wang D, Chen L, Li C, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 delivery by NIR-responsive biomimetic nanoparticles for targeted HBV therapy. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20:27.

131. Wu K, He M, Mao B, et al. Enhanced delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 system based on biomimetic nanoparticles for hepatitis B virus therapy. J Control Release. 2024;374:293-311.

132. Gorsuch CL, Nemec P, Yu M, et al. Targeting the hepatitis B cccDNA with a sequence-specific ARCUS nuclease to eliminate hepatitis B virus in vivo. Mol Ther. 2022;30:2909-22.

133. Wang Y, Li Y, Zai W, et al. HBV covalently closed circular DNA minichromosomes in distinct epigenetic transcriptional states differ in their vulnerability to damage. Hepatology. 2022;75:1275-88.

134. Lampertico P, Brunetto MR, Craxì A, et al.; HERMES Study Group. Add-on peginterferon alfa-2a to nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy for Caucasian patients with hepatitis B 'e' antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B genotype D. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:118-25.

135. Koffas A, Kumar M, Gill US, Jindal A, Kennedy PTF, Sarin SK. Chronic hepatitis B: the demise of the 'inactive carrier' phase. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:290-300.

136. Cao Z, Liu Y, Ma L, et al. A potent hepatitis B surface antigen response in subjects with inactive hepatitis B surface antigen carrier treated with pegylated-interferon alpha. Hepatology. 2017;66:1058-66.

137. Wu F, Lu R, Liu Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of peginterferon alpha monotherapy in Chinese inactive chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. Liver Int. 2021;41:2032-45.

138. Erken R, Loukachov VV, de Niet A, et al. A prospective five-year follow-up after peg-interferon plus nucleotide analogue treatment or no treatment in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B patients. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12:735-44.

139. Kim JH, Sinn DH, Kang W, et al. Low-level viremia and the increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients receiving entecavir treatment. Hepatology. 2017;66:335-43.

140. Wen WH, Chang MH, Zhao LL, et al. Mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus infection: significance of maternal viral load and strategies for intervention. J Hepatol. 2013;59:24-30.

141. Indolfi G, Easterbrook P, Dusheiko G, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in children and adolescents. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:466-76.

142. Zhang M, Li J, Xu Z, et al. Functional cure is associated with younger age in children undergoing antiviral treatment for active chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2024;18:435-48.

143. Liu Z, Lin C, Mao X, et al. Changing prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in China between 1973 and 2021: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 3740 studies and 231 million people. Gut. 2023;72:2354-63.

144. Li J, Zou B, Yeo YH, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999-2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:389-98.

145. Wang MM, Wang GS, Shen F, Chen GY, Pan Q, Fan JG. Hepatic steatosis is highly prevalent in hepatitis B patients and negatively associated with virological factors. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2571-9.

146. Huang SC, Su TH, Tseng TC, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease facilitates hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance and seroconversion. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:581-90.e6.

147. Huang Y, Gan Q, Lai R, et al. Application of fatty liver inhibition of progression algorithm and steatosis, activity, and fibrosis score to assess the impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver on untreated chronic hepatitis B patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:733348.

148. Lee MH, Chen YT, Huang YH, et al. Chronic viral hepatitis B and C outweigh MASLD in the associated risk of cirrhosis and HCC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1275-85.e2.

149. Jin X, Chen YP, Yang YD, Li YM, Zheng L, Xu CQ. Association between hepatic steatosis and entecavir treatment failure in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34198.

150. Chen K, Qu C. Impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection and high-fat diet on hepatocellular carcinoma development. Hepatoma Res. 2024;10:38.

151. Chen YC, Jeng WJ, Hsu CW, Lin CY. Impact of hepatic steatosis on treatment response in nuclesos(t)ide analogue-treated HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:146.

152. Matsushita K, Hoshino T. Novel diagnosis and therapy for hepatoma targeting HBV-related carcinogenesis through alternative splicing of FIR (PUF60)/FIRΔexon2. Hepatoma Res. 2018;4:61.

153. Lani L, Zaccherini G, Giannini EG, Trevisani F. Surveillance for patients at risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: how to improve its cost-effectiveness and expand the role of multidisciplinary tumor board? Hepatoma Res. 2025;11:9.

154. Jang JW, Kim JS, Kim HS, et al. Persistence of intrahepatic hepatitis B virus DNA integration in patients developing hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27:207-18.

155. Mon HC, Lee PC, Hung YP, et al. Functional cure of hepatitis B in patients with cancer undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J Hepatol. 2025;82:51-61.

156. Lai KN, Li PK, Lui SF, et al. Membranous nephropathy related to hepatitis B virus in adults. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1457-63.

157. Fu B, Ji Y, Hu S, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-viral therapy for hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227532.

158. Peng MJ, Guo XQ, Zhang WL, et al. Effect of pegylated interferon-α2b add-on therapy on renal function in chronic hepatitis B patients: a real-world experience. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:980250.

159. Liu CJ, Chuang WL, Sheen IS, et al. Efficacy of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir treatment of HCV infection in patients coinfected with HBV. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:989-97.

160. Cheng PN, Liu CJ, Chen CY, et al. Entecavir prevents HBV reactivation during direct acting antivirals for HCV/HBV dual infection: a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:2800-8.

161. Urban S, Neumann-Haefelin C, Lampertico P. Hepatitis D virus in 2021: virology, immunology and new treatment approaches for a difficult-to-treat disease. Gut. 2021;70:1782-94.

162. Wang R, Guo H, Kou X, Chen R, Zhang R, Li J. The interaction effect between key autophagy-related biomarkers and HBV/HCV infections on the survival prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res. 2025;11:10.

163. Nevola R, Rinaldi L, Giordano M, Marrone A, Adinolfi LE. Mechanisms and clinical behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma in HBV and HCV infection and alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatoma Res. 2018;4:55.

164. Chang ML, Liaw YF. Emerging therapies for chronic hepatitis B and the potential for a functional cure. Drugs. 2023;83:367-88.

165. Cui F, Blach S, Manzengo Mingiedi C, et al. Global reporting of progress towards elimination of hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:332-42.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].