Coping self-efficacy, social support, and mental health among transgender and gender diverse individuals seeking vaginoplasty and vulvoplasty

Abstract

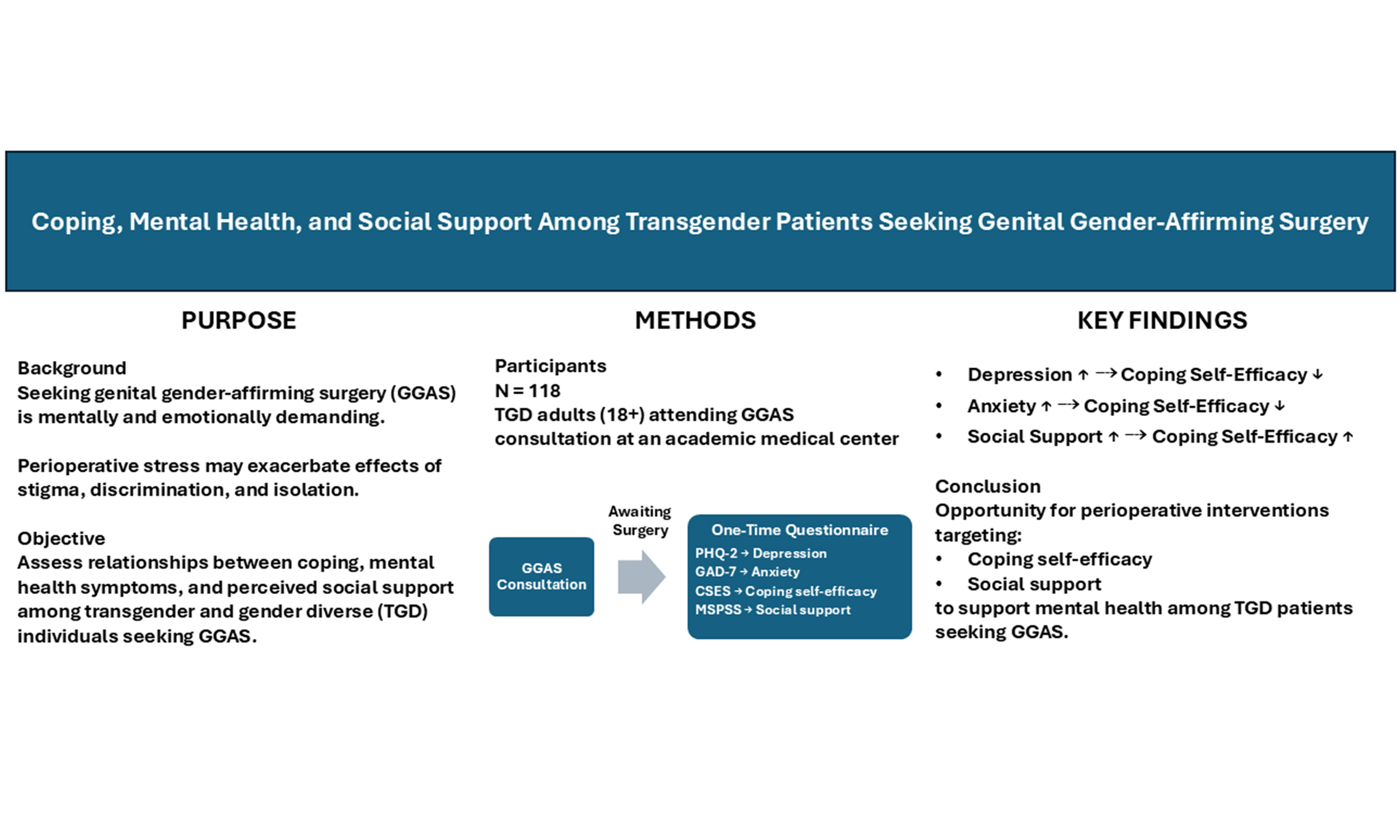

Aim: The process of seeking genital gender-affirming surgery (GGAS) can be mentally and emotionally taxing. Robust social support and effective coping strategies are essential for individuals pursuing GGAS, particularly during the perioperative period, when the complex demands of the healthcare system may exacerbate the adverse mental health effects of stigma, discrimination, and isolation experienced by transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people. To inform interventions aimed at enhancing the mental health of TGD individuals during the perioperative period, we assessed the relationships among coping, mental health, and perceived social support in TGD patients seeking GGAS (vaginoplasty and vulvoplasty) at an academic medical center.

Methods: Patients aged 18 years and older who attended a consultation visit for GGAS completed a one-time questionnaire (N = 118). Depression, anxiety, coping skills, and perceived social support were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item scale (GAD-7), Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES), and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), respectively.

Results: Among respondents, greater depression symptoms (PHQ-2 ≥ 3) were associated with lower coping self-efficacy. Lower coping self-efficacy was associated with higher symptoms of anxiety. Higher coping self-efficacy was associated with higher perceived level of social support.

Conclusions: These findings identify an opportunity for perioperative interventions that address coping self-efficacy and social support for TGD individuals pursuing GGAS.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Vulvoplasty, a type of genital gender-affirming surgery (GGAS), involves the construction of vulvar anatomy from penile and scrotal tissue, whereas vaginoplasty additionally includes the creation of an internal vaginal canal. Vulvoplasty and vaginoplasty are among the most commonly desired GGAS procedures for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals[1,2]. However, accessing these surgeries requires navigating complex insurance authorization processes, assembling a multidisciplinary care team (including surgeons, hair removal specialists, and mental health providers), and establishing a robust social support network to support the intensive post-operative recovery period. These requirements may be particularly burdensome for TGD individuals, who are more likely than their cisgender counterparts to experience isolation and trauma in healthcare settings and to encounter systemic barriers when seeking care[3].

TGD individuals experience stigma, discrimination, and harassment at disproportionately higher rates than their cisgender peers, leading to significant negative physical and mental health disparities - particularly elevated rates of anxiety and depression[1,4]. For some, the process of seeking GGAS can intensify the psychological toll of stigma and isolation. The minority stress model, which links experiences of stigma and discrimination - referred to as “minority stress” - to increased rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation[5,6], suggests that strong social support can buffer these effects by fostering resilience and enhancing coping abilities in marginalized populations[7,8]. Indeed, adaptive coping strategies and social support have been associated with better clinical outcomes and quality of life in TGD populations[9-11]. However, few studies have specifically examined these protective factors in the context of preparing for and recovering from GGAS.

To address this gap, we conducted a survey to: (1) describe coping self-efficacy, perceived social support, and mental health among TGD individuals seeking vaginoplasty and vulvoplasty at our institution; and (2) assess the acceptability of the coping self-efficacy and perceived social support measures in this population. Findings from this research can inform clinician researchers, surgeons, and gender program administrators in identifying both risk and protective factors that impact mental health during the GGAS preparation and recovery process.

METHODS

An online survey was conducted to collect data between November and December 2022. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were aged 18 years or older and had completed a consultation for gender-affirming vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty at our institution between November 1, 2019, and October 31, 2022. Eligible participants were recruited via email, which included a description of the study, eligibility criteria, the anonymous nature of the survey, and the potential risks and benefits of participation. Informed consent was obtained through a consent statement displayed at the beginning of the questionnaire, and participants could access the survey only after indicating their agreement to participate. Participants were invited to provide their email address for a chance to win one of ten $50 gift cards. This study was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (IRB #: STUDY00025040).

Measures

The survey, designed by the study authors (GD, AP, and JD), covered demographics, healthcare utilization, and a range of mental health aspects. Depression and anxiety were screened using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2)[12] and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item (GAD-7)[13] scales, respectively. Coping self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s confidence in their ability to cope with life’s stressors, was measured using the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES)[14]. Social support was assessed using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)[15]. These comprehensive measures were employed to evaluate multiple facets of participants’ mental health and well-being.

Statistical analysis

Data were extracted from Qualtrics, and statistical analyses were conducted using R[16]. Descriptive statistics (counts and percentages) summarized participants’ demographic characteristics. Questionnaire scores were recoded into categorical variables based on standard scoring thresholds: PHQ-2 (< 3 vs. ≥ 3), GAD-7 (< 8 vs. ≥ 8), and MSPSS [low/medium (1.0-5.0) vs. high (5.1-7.0)]. Mean coping self-efficacy (CSES) scores (standard deviation, SD) were compared across these binary categories using two-sample t-tests. A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted with PHQ-2 as the outcome and CSES as the primary predictor. In a prior study of a coping-effectiveness training intervention among HIV-seropositive gay men, a 0.4-SD increase in CSES was associated with clinically significant improvements in anxiety and other mental health outcomes[14]. To assess whether this association was present in our sample, CSES was standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by 0.4 times the SD. Age, housing status, disability status, and insurance type were included in the model as covariates. Similar approaches were applied with GAD-7 and MSPSS as outcomes. Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Of the 472 individuals invited to participate in the survey, 118 completed it and were included in the analysis, yielding a response rate of 25%. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of TGD participants seeking GGAS at our institution (N = 118). Most respondents were aged 25-44 years (57%). Participants could select multiple options for self-reported race and ethnicity, with the majority identifying as White (81%) and 17% identifying as people of color. A notable proportion of respondents (35%) reported having a disability, and 14% reported housing instability. Most participants had health insurance (84.7%), primarily through private insurance (53.4%) or Medicaid (25.4%).

Demographic characteristics of the survey respondents

| Demographics | n (%) |

| n | 118 |

| Age, years | |

| 18-24 | 9 (7.6) |

| 25-34 | 41 (34.7) |

| 35-44 | 26 (22.0) |

| 45+ | 25 (21.2) |

| (Missing/no response) | 17 (14.4) |

| Race/ethnicity (more than one response allowed) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 (2.5) |

| Asian | 4 (3.4) |

| Black or African American | 3 (2.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino/a/x | 6 (5.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 4 (3.4) |

| White | 95 (80.5) |

| (Missing/no response) | 17 (14.4) |

| Identify as having a disability | |

| Yes | 41 (34.7) |

| No | 60 (50.8) |

| (Missing/no response) | 17 (14.4) |

| Wait times | |

| Less than 6 months ago | 23 (19.5) |

| 6 months to 1 year ago | 39 (33.1) |

| 1 to 2 years ago | 38 (32.2) |

| More than 2 years ago | 18 (15.3) |

| (Missing / no response) | 0 (0.0) |

| Living situation | |

| I have a steady place to live | 84 (71.2) |

| I do not have a steady place to live | 17 (14.4) |

| (Missing/no response) | 17 (14.4) |

| Covered by any kind of health insurance | |

| Yes | 100 (84.7) |

| No | 1 (0.8) |

| Unsure | 0 (0.0) |

| (Missing/no response) | 17 (14.4) |

| Insurance type | |

| Private insurance | 63 (53.4) |

| Medicaid | 30 (25.4) |

| Medicare | 4 (3.4) |

| VA, TRICARE, or other military health insurance | 1 (0.8) |

| (Missing/no response) | 20 (16.9) |

| Surgery currently planning to have | |

| Vaginoplasty | 99 (83.9) |

| Vulvoplasty | 19 (16.1) |

| (Missing/no response) | 0 (0.0) |

| Still planning on having this surgery at OHSU | |

| Yes | 108 (91.5) |

| No, I plan to have this surgery somewhere other than OHSU | 10 (8.5) |

| (Missing/no response) | 0 (0.0) |

The reported duration since consultation for GGAS was divided into four categories: less than 6 months (19.5%), 6 months to 1 year (33.1%), 1 to 2 years (32.2%), and over 2 years (15.3%). A large majority of respondents had a consultation for vaginoplasty (n = 99) rather than vulvoplasty (n = 19), the latter being a procedure focused on constructing external vulvar anatomy without creating an internal vaginal canal.

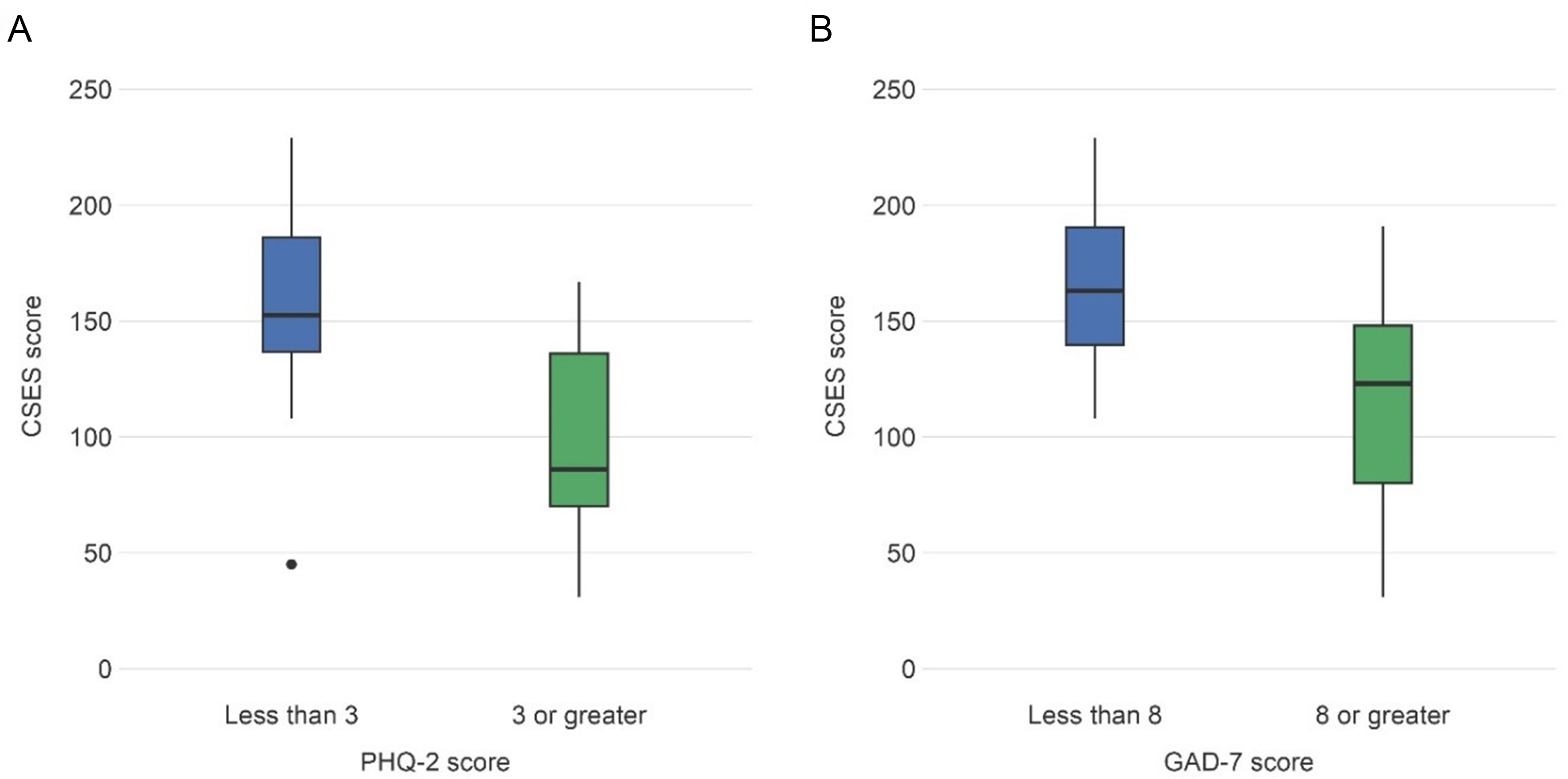

Higher coping self-efficacy was associated with a lower likelihood of depression and lower levels of anxiety, as measured by PHQ-2 [Figure 1A] and GAD-7 [Figure 1B] scores, respectively. Overall, 24% of respondents reported symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder (PHQ-2 ≥ 3), and 41% reported symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 8). Mean (SD) CSES scores for those with and without likely depressive symptoms were 99.4 (40.1) and 158.9 (33.9), respectively. The difference in mean CSES scores for participants with and without symptoms of anxiety was 49.8 [95% confidence interval (CI): 34.3-65.4].

Figure 1. CSES scores by Mental Health Screening Measures. (A) Box and whisker plots represent CSES scores [25th, 50th (median), and 75th percentiles] for respondents with PHQ-2 scores < 3 (minimal to no symptoms of depression) vs. PHQ-2 ≥ 3 (symptoms indicative of likely depression). Respondents with minimal symptoms of depression demonstrated significantly greater coping self-efficacy than those with symptoms indicative of likely depression (P < 0.001); (B) Box and whisker plots represent CSES scores for respondents with GAD-7 scores < 8 (minimal to no symptoms of anxiety) vs. GAD-7 ≥ 8 (symptoms indicative of anxiety). Respondents with minimal symptoms of anxiety demonstrated significantly greater coping self-efficacy than those with symptoms indicative of anxiety (P < 0.001). CSES: Coping Self-Efficacy Scale; PHQ-2: Patient Health Questionnaire-2; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7.

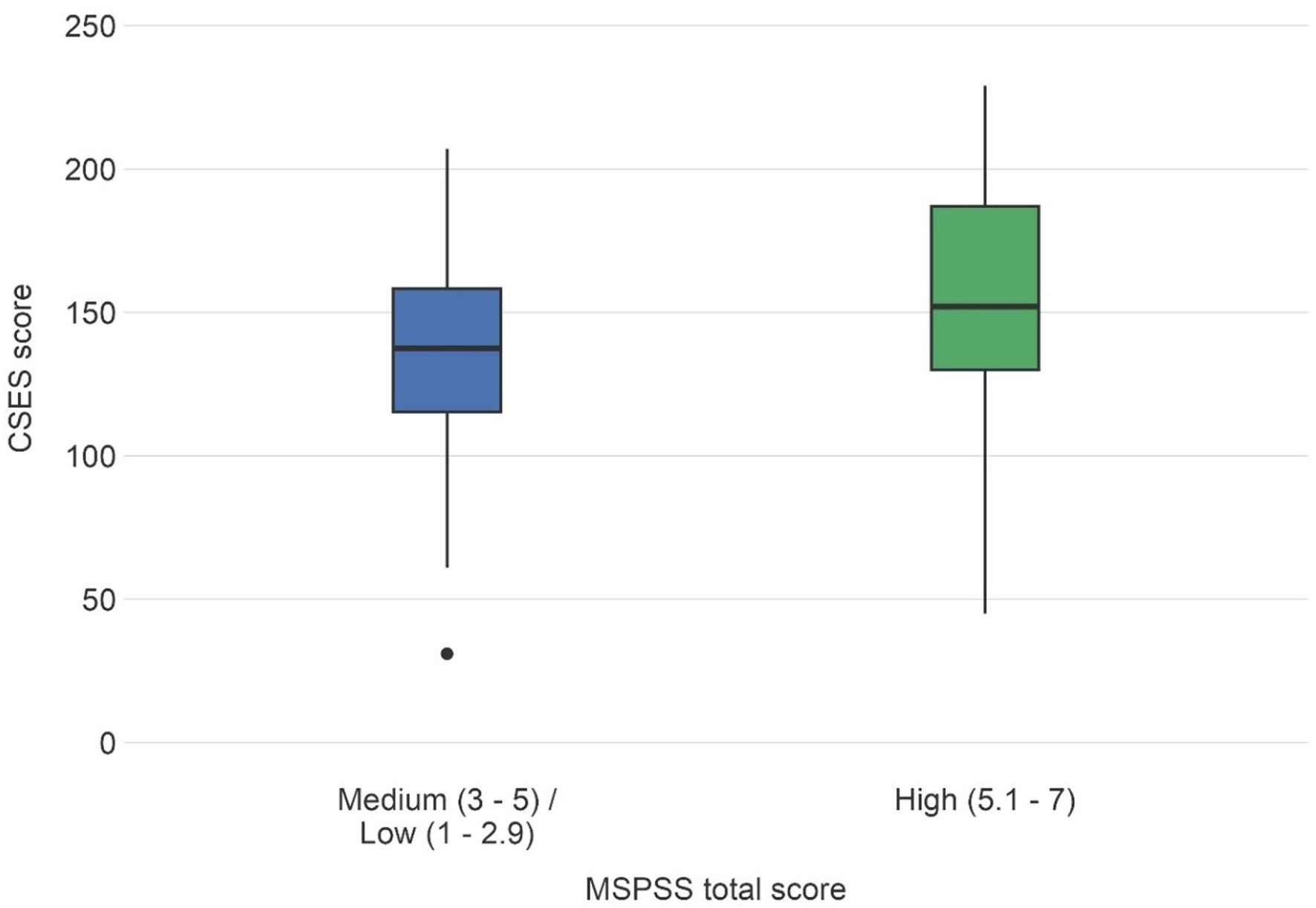

When categorized into two groups - medium/low versus high perceived social support - 44% of respondents reported medium or low support, while 56% reported high support. Individuals with high perceived social support demonstrated significantly greater coping self-efficacy than those with medium/low support [Figure 2].

Figure 2. CSES scores by Perceived Social Support. Box and whisker plots demonstrate CSES scores separated by MSPSS scores categorized as low/medium vs. high. Significantly higher CSES scores were observed among respondents with high levels of perceived social support compared to those reporting low and medium perceived social support (P < 0.001). CSES: Coping Self-Efficacy Scale; MSPSS: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

Odds of mental health and social support

Table 2 presents the results of three multivariable logistic regression models, with PHQ-2, GAD-7, and MSPSS as the dependent variables and CSES as the primary predictor. All models were adjusted for age, housing status, disability status, and insurance type.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression results for each outcome of interest

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| Outcome | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value |

| PHQ-2 | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.6) | < 0.001 | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) | < 0.001 |

| GAD-7 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) | < 0.001 | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) | < 0.001 |

| MSPSS | 0.8 (0.6 to 0.9) | 0.003 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) | < 0.001 |

Each moderate increase in coping self-efficacy (0.4 SD) was associated with a 50% lower odds of symptoms suggestive of major depression (PHQ-2 score ≥ 3; 95%CI: 0.3-0.7, P < 0.001). Similarly, each 0.4 SD increase in CSES corresponded to a 0.4-fold reduction in the odds of likely anxiety (GAD-7 score ≥ 8; 95%CI: 0.3-0.6, P < 0.001). The odds of medium/low perceived social support decreased by 0.7-fold per 0.4 SD increase in CSES (95%CI: 0.6-0.9, P < 0.001). Housing instability was significantly associated with PHQ-2 and GAD-7 scores in univariable models, but this association was not observed in the multivariable analyses. For full multivariable logistic regression results, please see Supplementary Tables 1-3.

Odds ratios and 95%CI indicate the change in odds of each outcome per 0.4 SD increase in CSES. All three multivariable models were adjusted for age, housing status, disability status, and insurance type.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to describe coping self-efficacy, perceived social support, and mental health among a sample of TGD patients pursuing GGAS (vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty) at our medical center. In this sample, the mean CSES score was 144 (SD 43), which is lower than figures reported in studies of cisgender individuals. For example, a population-based sample of cisgender adults in the UK (N = 182; 58 men, 121 women, 3 unknown) had a significantly higher mean CSES score of 159.62 (SD 41)[17]. Furthermore, participants with moderate to severe depressive symptoms (PHQ-2 ≥ 3) demonstrated substantially lower mean CSES scores (99, SD 40), indicating reduced coping self-efficacy in the context of potential depressive symptoms and challenging life events.

The minority stress model hypothesizes that members of stigmatized social groups are exposed to unique and additive stressors - such as social and family rejection, harassment, violence, housing and employment discrimination, and barriers to accessing healthcare - which can lead to internalized negative beliefs and contribute to psychological distress[6-8,18]. Our findings align with existing research linking discrimination and stigma to higher rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation[5,6], highlighting the disproportionate mental health challenges faced by TGD individuals. Among TGD people, minority stress has been associated with increased risk of self-injurious behavior and suicidal ideation[8,19,20]. Rates of likely depression (24.3%) and anxiety (40.6%) in our sample were substantially higher than those reported in the United States cisgender population, consistent with prior literature on mental health outcomes among TGD individuals[1,19,21].

Preparation for GGAS is inherently stressful for TGD individuals, who must navigate the healthcare system and meet pre-surgical criteria while experiencing minority stress. Social support is a key protective factor against these adverse outcomes. The minority stress model suggests that strong social connections can buffer stress, fostering resilience and coping abilities among marginalized communities[7-9]. Social and peer support, which creates safe and non-stigmatizing environments, promotes coping and resilience, mitigating the effects of minority stress[7,18,19,22]. Additionally, social support is associated with higher self-esteem and predicts quality of life, positive surgical outcomes, and psychological well-being following GGAS[23,24]. In comparing transgender and cisgender populations, Davey et al. (2014) reported that perceived social support (MSPSS) was markedly lower for transgender women than for cisgender men and women, as well as transgender men (assigned female at birth)[23]. Consistent with these findings, our results show that higher coping self-efficacy correlates with increased perceived social support among TGD individuals seeking GGAS, suggesting that interventions aimed at enhancing social support may improve health outcomes in this population.

Coping skills are critical for individuals preparing for and recovering from GGAS, as these processes involve numerous stressors that may be beyond one’s control. Individuals with higher coping self-efficacy are likely better equipped to self-regulate and problem-solve when facing insurance challenges, surgical delays, or the task of assembling and engaging support networks, as well as managing post-operative complications ranging from minor wound separation to major life-threatening events. Our research examines the interplay between social support and coping self-efficacy in the context of GGAS for the TGD community. Given the important role of peer and social support in fostering coping skills, mental health, and positive outcomes among individuals undergoing life-changing surgeries, access to targeted interventions should be an integral part of the multidisciplinary care approach for TGD individuals with higher support needs. These findings underscore the necessity for further research and the development of interventions designed to strengthen coping capacity, particularly during the GGAS process.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. This was a single-center study using convenience sampling via a survey distributed to TGD patients seeking GGAS (vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty). While our sample included Medicaid enrollment rates consistent with the U.S. TGD population[25], generalizability is limited due to variability in GGAS coverage across state Medicaid programs and Oregon’s comprehensive Medicaid expansion following the Affordable Care Act in 2010[26]. Additionally, our sample does not reflect the broader racial and ethnic distribution of the TGD population: although racial/ethnic minority individuals comprise 34% of U.S. adults and an estimated 45% of trans-identified adults[27]. 81% of respondents in our study identified as White. This disproportion limits the applicability of our findings to racially and ethnically diverse TGD populations. Prior research indicates that stigma, discrimination, and barriers to healthcare have more pervasive effects on mental and physical health among TGD individuals with intersectional identities, including Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), people living with disabilities, and those experiencing housing instability or houselessness[1]. Future research on mental health, coping self-efficacy, and perceived social support among TGD populations seeking GGAS should prioritize inclusion of racially and ethnically diverse participants to ensure generalizability and appropriately assess intersectional impacts of race and gender diversity.

Consistent with other survey-based research, response bias must be considered when interpreting these results. Our response rate of 25% suggests that individuals with greater psychological well-being may have been more likely to participate, potentially skewing the findings. Respondents with inherently higher levels of social support and coping self-efficacy, coupled with lower rates of depression, may be overrepresented. Consequently, the overall level of social support in the broader patient population may be lower than our results suggest.

Because demographic data did not include specific information on gender identity, we were unable to disaggregate responses. This lack of granularity may obscure meaningful differences in social support, coping self-efficacy, and mental health outcomes among TGD individuals seeking feminizing procedures. Additionally, the cross-sectional design precludes assessment of temporal changes in mental health, coping, and perceived social support. To address confounding, we applied multivariable logistic regression, adjusting odds ratios for relevant covariables.

Despite these limitations, our study demonstrates that higher coping self-efficacy is associated with a lower likelihood of depression and anxiety among TGD individuals navigating the complex process of seeking GGAS.

Conclusion

Ongoing social marginalization, isolation, and stigma experienced by TGD individuals are compounded by the stress of preparing for and recovering from GGAS. Our findings highlight the interplay between mental health, coping self-efficacy, and social support among TGD populations seeking GGAS. Interventions that strengthen coping skills and enhance social support within peer networks may foster resilience, promote positive surgical outcomes, and improve overall mental health and quality of life. These benefits extend not only to TGD patients but also to gender care centers and healthcare systems more broadly.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Penkin A, Downing J, Dugi DD III, Gornick F

Investigation: Gornick F, Downing J, Dy GW

Formal analysis: Gornick F, Downing J, Dy GW, Latour E, Bassale S

Writing - original draft: Hart ER, Gornick F

Supervision: Dy GW

Writing - review and editing: Hart ER, Gornick F, Downing J, Latour E, Bassale S, Dugi DD III, Penkin A, Dy GW

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials. All original data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and qualified for exemption under 45 CFR 46, Exempt Category 2(iii) (IRB ID: STUDY00025040). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. Available from: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf. [Last accessed on 23 Jan 2026].

2. Nolan IT, Kuhner CJ, Dy GW. Demographic and temporal trends in transgender identities and gender confirming surgery. Transl Androl Urol. 2019;8:184-90.

3. Wilson EC, Chen YH, Arayasirikul S, Wenzel C, Raymond HF. Connecting the dots: examining transgender women’s utilization of transition-related medical care and associations with mental health, substance use, and HIV. J Urban Health. 2015;92:182-92.

4. Downing JM, Przedworski JM. Health of transgender adults in the U.S., 2014-2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:336-44.

5. Jefferson K, Neilands TB, Sevelius J. Transgender women of color: discrimination and depression symptoms. Ethn Inequal Health Soc Care. 2013;6:121-36.

6. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674-97.

7. Kia H, MacKinnon KR, Abramovich A, Bonato S. Peer support as a protective factor against suicide in trans populations: a scoping review. Soc Sci Med. 2021;279:114026.

8. Trujillo MA, Perrin PB, Sutter M, Tabaac A, Benotsch EG. The buffering role of social support on the associations among discrimination, mental health, and suicidality in a transgender sample. Int J Transgend. 2017;18:39-52.

9. Heiden-Rootes K, Meyer D, Sledge R, et al. Seeking gender-affirming medical care: a phenomenological inquiry on skillful coping with transgender and non-binary adults in the United States Midwest. Qual Res Med Healthc. 2023;7:11485.

10. Oorthuys AOJ, Ross M, Kreukels BPC, Mullender MG, van de Grift TC. Identifying coping strategies used by transgender individuals in response to stressors during and after gender-affirming treatments-an explorative study. Healthcare. 2022;11:89.

11. Puckett JA, Matsuno E, Dyar C, Mustanski B, Newcomb ME. Mental health and resilience in transgender individuals: what type of support makes a difference? J Fam Psychol. 2019;33:954-64.

12. Staples LG, Dear BF, Gandy M, et al. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of brief measures of depression, anxiety, and general distress: The PHQ-2, GAD-2, and K-6. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;56:13-8.

13. Beard C, Björgvinsson T. Beyond generalized anxiety disorder: psychometric properties of the GAD-7 in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28:547-52.

14. Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:421-37.

15. Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:610-7.

16. Team RC. The R project for statistical computing. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/. [Last accessed on 23 Jan 2026].

17. Colodro H, Godoy-Izquierdo D, Godoy J. Coping self-efficacy in a community-based sample of women and men from the United Kingdom: the impact of sex and health status. Behav Med. 2010;36:12-23.

18. Meyer IH. Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2:209-13.

19. Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:943-51.

20. Kaufman EA, Meddaoui B, Seymour NE, Victor SE. The roles of minority stress and thwarted belongingness in suicidal ideation among cisgender and transgender/nonbinary LGBTQ+ individuals. Arch Suicide Res. 2023;27:1296-311.

21. Wanta JW, Niforatos JD, Durbak E, Viguera A, Altinay M. Mental health diagnoses among transgender patients in the clinical setting: an all-payer electronic health record study. Transgend Health. 2019;4:313-5.

22. Johnson AH, Rogers BA. “We’re the normal ones here”: community involvement, peer support, and transgender mental health. Sociological Inquiry. 2020;90:271-92.

23. Davey A, Bouman WP, Arcelus J, Meyer C. Social support and psychological well-being in gender dysphoria: a comparison of patients with matched controls. J Sex Med. 2014;11:2976-85.

24. Swan J, Phillips TM, Sanders T, Mullens AB, Debattista J, Brömdal A. Mental health and quality of life outcomes of gender-affirming surgery: a systematic literature review. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2023;27:2-45.

25. Mallory C, Tentindo W. Medicaid coverage for gender-affirming care. Available from: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Medicaid-Gender-Care-Dec-2022.pdf. [Last accessed on 23 Jan 2026].

26. Zaliznyak M, Bresee C, Garcia MM. Age at first experience of gender dysphoria among transgender adults seeking gender-affirming surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201236.

27. Flores AR, Brown TNT, Herman JL. Race and Ethnicity of Adults who Identify as Transgender in the United States. Available from: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Race-Ethnicity-Trans-Adults-US-Oct-2016.pdf. [Last accessed on 23 Jan 2026].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].