Recognizing Gaucher disease in the fifth decade and beyond: a retrospective case study in patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent

Abstract

Gaucher disease (GD) results in visceral, hematological, and skeletal manifestations. The Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) population has the highest prevalence due to a founder effect involving the glucocerebrosidase-1 (GBA1) p.N409S variant. Despite this high prevalence, diagnosis can be delayed. We present clinical findings from 20 patients of AJ descent diagnosed with GD type 1 (GD1) at ≥ 50 years of age. Sixty percent underwent bone marrow biopsy as part of their clinical

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Gaucher disease (GD) is an autosomal recessive lysosomal disease caused by enzymatic deficiency of glucocerebrosidase-1 (GBA1; EC 3.2.1.45), resulting in visceral, hematological, and skeletal manifestations[1]. Glucocerebrosidase-1 catalyzes the conversion of glucosylceramide into free ceramides and glucose in the lysosome. Cellular adaptations to glucocerebrosidase-1 deficiency include deacylation of glucosylceramide to glucosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb1)[2], a more soluble lipid that accumulates in dysfunctional lysosomes of engorged macrophages (Gaucher cells) in patients with GD and can be detected in blood and tissue[3-5]. Lyso-Gb1 has been shown to correlate with disease severity and is regarded as the most sensitive biomarker for diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring therapeutic response in GD[6-8].

The Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) population has the highest prevalence of GD, with an estimated incidence of 1/900[9] and a carrier frequency of ~1/15, which can be attributed to a founder effect and genetic bottleneck involving the GBA1 p.N409S variant[10], as well as a possible selective advantage of protection against tuberculosis conferred by GD heterozygosity[11]. Several other pathogenic variants are also significantly more common in AJ than in the general populations of their countries of residence[12]. Patients homozygous for the p.N409S variant, which is associated with GD type 1 (GD1), are clinically heterogenous, with most presenting in adulthood. A positive family history of GD and AJ ancestry have been reported as two major co-variables for GD1[13]; however, diagnosis can often be delayed in this population despite the high prevalence[14-16].

The median age at diagnosis of p.N409S homozygotes is 28 years according to registry data, with 32% diagnosed before age 20[17,18]; however, there is limited information on patients diagnosed after the fifth decade of life. Here, we present clinical and diagnostic findings from 20 patients of AJ descent diagnosed with GD1 at ≥ 50 years of age (median: 59 years; range: 50-71), categorized by what brought them to clinical attention. Twelve patients were symptomatic with persistent cytopenia, fatigue, or elevated ferritin, leading to a bone marrow biopsy that showed findings consistent with GD and prompted additional diagnostic testing. Four had a positive family history and were diagnosed through cascade familial testing. Three were diagnosed during Parkinson’s disease evaluation, and one was identified incidentally through carrier screening.

Presenting signs and symptoms included splenomegaly (18/20), osteopenia/osteoporosis (17/20), thrombocytopenia (17/20), anemia (13/20), bone/joint pain (14/20), lytic lesions/avascular necrosis/pathological fractures (9/20), pulmonary manifestations (1/20), and parkinsonism (3/20). All patients had elevated plasma lyso-Gb1 (median: 10.6 nmol/L; mean: 103.5 nmol/L; range: 2.8-557.2) at initial and subsequent evaluations. Fifteen patients were homozygous for p.N409S, three harbored p.N409S in trans with another pathogenic variant, and two were compound heterozygotes for pathogenic variants that did not include p.N409S.

Our findings demonstrate disease manifestations in a cohort of 20 AJ patients diagnosed at ≥ 50 years, with 15 patients eventually receiving treatment. This work underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion for GD and highlights the need for timely disease recognition.

METHODS

Medical records were reviewed for patients with GD followed at the Duke University Medical Center Metabolic Genetics Clinic (n = 86) and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (n > 200) to identify patients with GD1 of AJ descent diagnosed at ≥ 50 years of age. Patients were excluded if they had (1)

Study data were partially collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, web-based electronic data capture tool hosted at Duke University[23,24]. REDCap is designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless downloads to common statistical packages, and (4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

Plasma lyso-Gb1 analysis for samples collected from Duke patients was performed as part of a research study approved by the Duke IRB (Pro00088186). Testing was conducted using a previously published method[25] in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)/College of American Pathologists (CAP)-certified Duke Biochemical Genetics Laboratory. The normal reference range for lyso-Gb1 is ≤ 1.9 nmol/L. Plasma lyso-Gb1 analysis for samples collected from Mount Sinai School of Medicine (MSSM) patients was performed by either Sema4, DBA Mount Sinai Genomics Inc, or LabCorp - each a CLIA/CAP-certified laboratory - according to standard operating procedures. Results were reported in ng/mL, with a normal reference range of < 1.0 ng/mL (2.2 nmol/L). The normal reference range for this case report is defined as 2.05 nmol/L, or the combined average. Quantitative parameters were only available for the hematologic domain in this cohort; therefore, disease severity scoring systems, such as the Disease Severity Scoring System (DS3), which incorporate hematologic, visceral, and skeletal domains, could not be applied[26].

Statistical analysis

Median biomarker levels were compared between the symptomatic and pre-symptomatic cohorts and between the treated and untreated cohorts using an unpaired Mann-Whitney U test. Data were presented as medians, and the error bars represent standard error. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data analyses were performed in RStudio (Version 2024.12.0 + 467).

RESULTS

Twenty white, non-Hispanic/Latino patients of AJ descent diagnosed at ≥ 50 years of age (median: 59) with GD1 were included in our study cohort [Table 1]. Twelve patients had signs of GD1, with bone marrow biopsy revealing Gaucher cells that prompted further diagnostic work-up via enzymatic and molecular analysis. Three patients were diagnosed with GD through GBA1 analysis as a part of their Parkinson’s disease work-up. Of the remaining five patients, four came to clinical attention due to a positive family history of GD, and one was diagnosed with GD through carrier screening in the reproductive setting. Fifteen patients in our cohort were homozygous c.1226A > G (p.N409S). Of the remaining patients, three harbored the p.N409S pathogenic variant in trans with the c.1297G > T (p.V433L), c.1604G > A (p.R535H), or c.115 + 1G > A, respectively. One patient was compound heterozygous for c.1604G > A (p.R535H)/c.115 + 1G > A pathogenic variants and one patient was compound heterozygous for c.1448T > C (p.L483P)/c.1604G > A (p.R535H).

Cohort clinical characteristics

| Signs and symptoms upon initial clinical evaluation after GD1 diagnosis | |||||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis | Age at publication | Sex | GBA1 variants | Reason for diagnosis | Thrombo-cytopenia | Pan-cytopenia | Splenomegaly | Pathologic fractures | Bone pain | Bone crisis | Osteopenia/ porosis | Treatment type | |

| P1 | 63 | 74 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Family historyꭞ | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | ERT |

| P2 | 55 | 65 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | Untreated |

| P3 | 63 | 70 | Female | p.N409S/p.N409S | Family historyꭞ | - | - | - | + | + | - | +* | Untreated |

| P4 | 67 | 78 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | ERT |

| P5 | 53 | 71 | Female | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | ERT to SRT |

| P6 | 64 | 68 | Female | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | ERT |

| P7 | 61 | 68 | Female | p.N409S/p.N409S | Parkinson’s disease | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | ERT |

| P8 | 56 | 81 | Female | p.N409S/p.R535H | Parkinson’s disease | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | Untreated |

| P9 | 57 | 77 | Male | p.R535H/c.115 + 1G > A | Symptomatic | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | ERT |

| P10 | 71 | 77 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | ERT |

| P11 | 54 | 66 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | ERT |

| P12 | 52 | 59 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Carrier screeningꭞ | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | Untreated |

| P13 | 50 | 83 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | ERT |

| P14 | 67 | 83 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | Untreated |

| P15 | 53 | 75 | Female | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | ERT |

| P16 | 60 | 69 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Symptomatic | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | ERT |

| P17 | 63 | 68 | Female | p.N409S/p.V433L | Parkinson’s disease | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | ERT to SRT |

| P18 | 52 | 77 | Female | p.N409S/c.115 + 1G > A | Symptomatic | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | SRT |

| P19 | 58 | 68 | Female | p.L483P/p.R535H | Family historyꭞ | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | ERT to SRT** |

| P20 | 63 | 66 | Male | p.N409S/p.N409S | Family historyꭞ | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | SRT |

Clinical features at baseline evaluation after diagnosis revealed that splenomegaly was present in 90% of patients, thrombocytopenia in 85%, and osteopenia/osteoporosis in 85%. Hyperferritinemia was observed in 80% of patients, anemia in 65%, bone or joint pain in 70%, pathologic fractures in 45%, and parkinsonism and leukopenia in 15%. Additionally, 10% of patients were being followed for myelodysplastic syndrome with clonal mutations: ASXL1, ZRSR2, EGFR, and STAG2 in Patient 4, and ASXL1, TET2, CBL, and U2AF1 in Patient 10 [Table 2]. Less common findings included pulmonary hypertension, lytic lesions, avascular necrosis, bone crises, and small lymphocytic lymphoma, the latter observed in one patient. Additional features of GD1, including peripheral neuropathy, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, and hepatocellular carcinoma, were not observed.

Clinical features of Gaucher disease at the time of initial evaluation

| n (%) | |

| Hematological involvement | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 17 (85) |

| Hyperferritinemia | 16 (80) |

| Anemia | 13 (65) |

| Leukopenia | 3 (15) |

| Visceral involvement | |

| Mild splenomegaly | 16 (80) |

| Moderate splenomegaly | 1 (5) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (5) |

| Bone involvement | |

| Osteopenia | 11 (55) |

| Osteoporosis | 6 (30) |

| Bone or joint pain | 14 (70) |

| Pathological fractures | 9 (45) |

| Lytic lesions | 1 (5) |

| Avascular necrosis | 1 (5) |

| Bone crisis | 1 (5) |

| Neurological involvement | |

| Parkinsonism | 3 (15) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 0 (0) |

| Malignancy diagnosis | |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 2 (10) |

| Small lymphocytic lymphoma | 1 (5) |

| Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) | 0 (0) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0 (0) |

Upon initial and repeated evaluations, lyso-Gb1 levels were elevated in all patients [Table 3], whereas chitotriosidase (CHITO) levels were within the normal reference range in four patients, at least two of whom did not harbor the chitinase-1 (CHIT1) 24-base pair duplication. Mean and median platelet counts were within reference limits among pre-symptomatic patients.

Baseline biomarker statistics

| All Patients (n = 20) | Min | Median | Mean | Max |

| Lyso-Gb1 (nmol/L) | 2.8 | 10.6 | 103.5 | 557.2 |

| Chitotriosidase (nmol/hr/mL) | 34 | 1,146 | 1,651 | 5,530 |

| Platelet Count (109/L) | 45 | 124 | 136 | 234 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.5 | 13.1 | 13.2 | 16.6 |

| Symptomatic* (n = 15) | ||||

| Lyso-Gb1 (nmol/L) | 2.8 | 22.3 | 142.1 | 557.2 |

| Chitotriosidase (nmol/hr/mL) | 34 | 1,690 | 1,791 | 5,530 |

| Platelet Count (109/L) | 45 | 91 | 113 | 234 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.5 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 16.5 |

| Pre-symptomatic (n = 5) | ||||

| Lyso-Gb1 (nmol/L) | 6.1 | 10.6 | 47.5 | 34.8 |

| Chitotriosidase (nmol/hr/mL) | 62 | 572 | 1,229 | 4,363 |

| Platelet Count (109/L) | 128 | 190 | 187 | 224 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.8 | 13.7 | 14.2 | 16.6 |

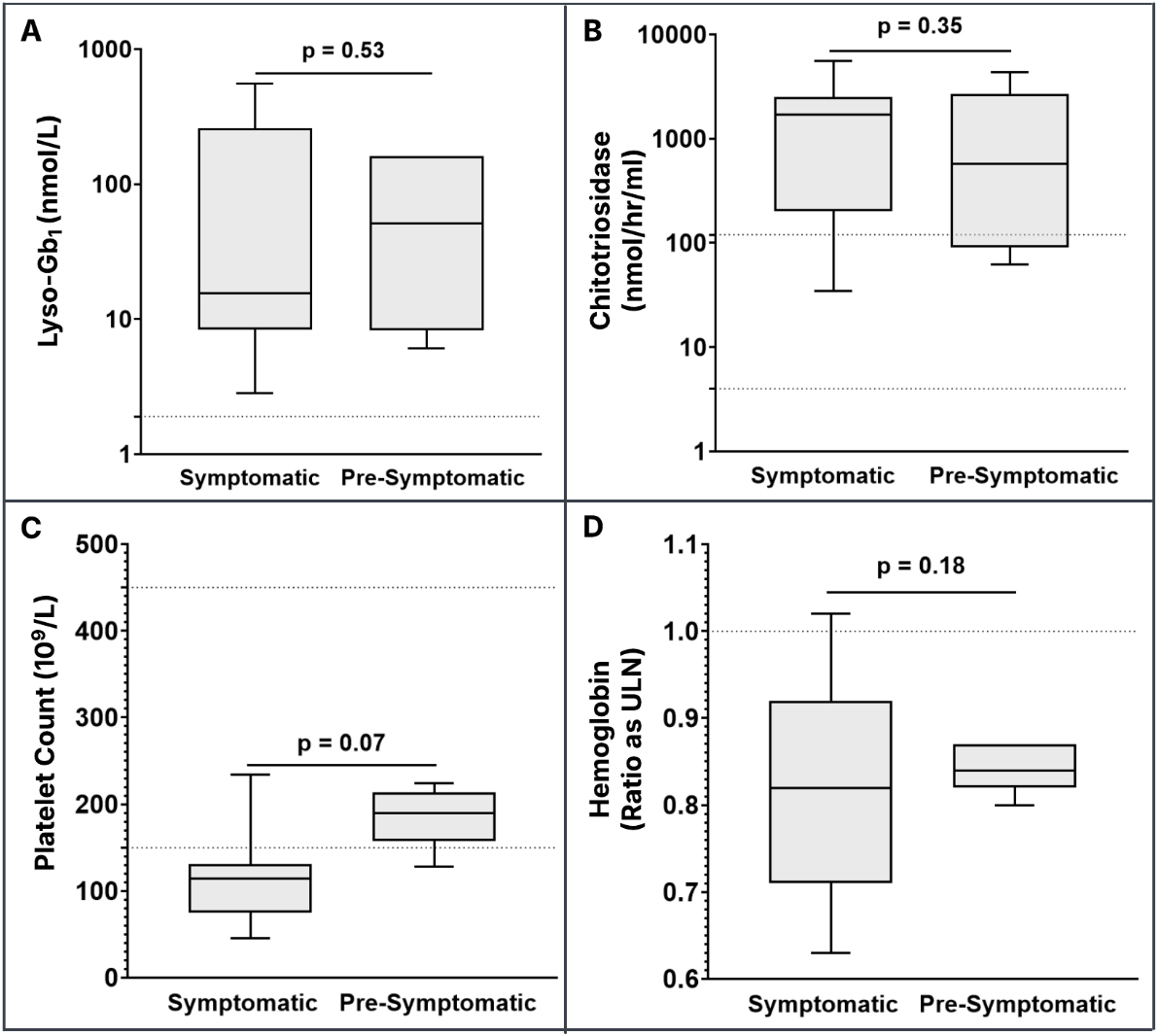

No statistically significant difference was observed in lyso-Gb1 level, CHITO activity, platelet counts, and hemoglobin between patients identified symptomatically - either through bone marrow biopsy or during Parkinson’s disease evaluation - and those identified pre-symptomatically through a positive family history or reproductive carrier screening [Figure 1A-D]. However, the difference in platelet counts between the two groups approached statistical significance (symptomatic group: range 45-234 × 109/L, mean: 116 × 109/L, median: 114 × 109/L; pre-symptomatic group: range 128-224 × 109/L, mean: 187 × 109/L, median:

Figure 1. Biomarker values in symptomatic and pre-symptomatic patients. The horizontal dashed line for lyso-Gb1 (A) denotes the upper limit of the normal reference range (≤ 2.05 nmol/L); The horizontal dashed lines for CHITO (4-120 nmol/hr/mL) (B) and platelet count (150-450 × 109/L) (C) denote the lower and upper limits of the normal reference range; The horizontal dashed line for hemoglobin values (D) denotes the ratio as the upper limit of normal (ULN) to account for age- and sex-specific reference ranges. The symptomatic group includes patients who presented with ongoing signs/symptoms and those with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lyso-Gb1: Glucosylsphingosine; CHITO: chitotriosidase.

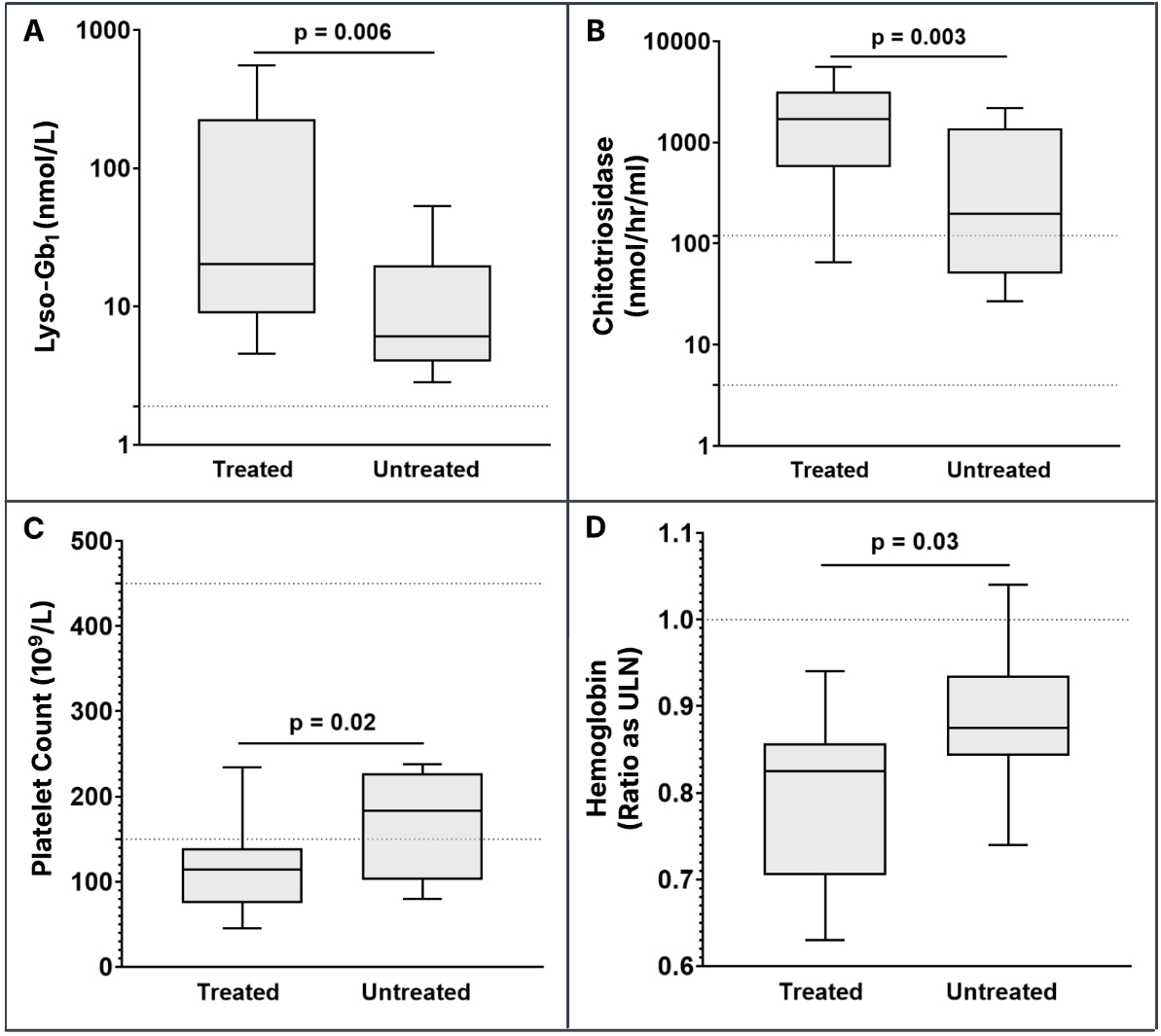

Treatment for GD was not recommended in four patients due to their mild phenotypes, including the absence of GD-related bone disease[27]. Among the 16 patients for whom treatment was recommended, only one male patient homozygous for p.N409S - who presented with thrombocytopenia and had documented splenomegaly, osteopenia, and persistently elevated biomarkers - deferred therapy. All remaining patients with active GD signs or symptoms initiated treatment, as did two patients presenting with Parkinson’s disease and three pre-symptomatic patients with a positive family history. Statistically significant differences were observed across all biomarkers when comparing baseline levels between treated and untreated patients [Figure 2A-D]. Lyso-Gb1 was elevated in all patients, with a mean of 126.3 nmol/L and a median of

Figure 2. Baseline treatment-naïve biomarker values in treated patients and naïve biomarker values in untreated patients. The horizontal dashed line for lyso-Gb1 (A) denotes the upper limit of the normal reference range (≤ 2.05 nmol/L). The horizontal dashed lines for chitotriosidase (4-120 nmol/hr/mL) (B) and platelet count (150-450 × 109/L) (C) denote the lower and upper limits of the normal reference range. The horizontal dashed line for hemoglobin values (D) denotes the ratio as the ULN to account for age- and

DISCUSSION

This is not the first study of GD1 in patients of AJ ethnicity who are largely homozygous for p.N409S; however, our findings challenge long-standing assumptions about the natural history and clinical burden of GD1 in this population, particularly among those diagnosed after the fifth decade of life. In 1992, a cohort of 53 patients with GD1 was described, including 39 AJ individuals, 15 of whom were ≥ 50 years at the time of evaluation[28]. Among these, 77% had either bone pain or radiographic evidence of bone involvement, despite the absence of skeletal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) imaging. This study contributed to the perception that GD was rarely a progressive disorder in middle-aged AJ patients.

This conclusion was further reinforced by a 2019 study of 80 untreated Israeli AJ patients homozygous for p.N409S, which reported no clinical bone disease, although 41% had osteopenia and 10% had osteoporosis[29]. The median age at diagnosis was 22 (range: 0-60) years; however, the number of patients

Taddei et al. offered a different perspective, reporting that 25% of 189 evaluable AJ p.N409S homozygotes were diagnosed after age 50[31]. Although specific signs and symptoms were not detailed, the study showed that asymptomatic individuals at age 50 progressed linearly to symptomatic status by age 75, primarily due to skeletal manifestations. Furthermore, in a series of 11 AJ p.N409S homozygotes, five were diagnosed with GD between ages 49-71 years, and four experienced osteonecrosis or pathological fractures[32]. Similarly, Balwani et al. found that nearly half of 37 AJ GD1 patients identified through prenatal screening had anemia or thrombocytopenia, and many had osteopenia or osteoporosis on DEXA or MRI, despite being younger than 40 years[10]. Finally, among 93 patients with GD1, the mean age at diagnosis was 49.9 years (range:

Our cohort of 20 AJ patients diagnosed with GD1 at ≥ 50 years adds to this evolving understanding. Only one patient was diagnosed incidentally through carrier screening; the remaining 19 were identified due to persistent signs or symptoms, Parkinson’s disease work-up, or a positive family history. This distribution underscores the importance of clinical vigilance and cascade testing in high-risk populations. The clinical burden in our cohort was substantial. At baseline, 90% had splenomegaly; 85% had thrombocytopenia and osteopenia/osteoporosis; 80% had hyperferritinemia; and 65% had anemia. Bone or joint pain was reported in 70%, and 45% had pathological fractures. Less common findings included pulmonary hypertension, avascular necrosis, and myelodysplastic syndrome. These results are consistent with prior reports from South Florida and New York, in which older AJ patients exhibited significant skeletal disease and often responded poorly to ERT[10,33].

Genotypic analysis revealed that 75% of patients were p.N409S homozygotes, while the remainder harbored p.N409S in trans with p.V433L, p.R535H, or c.115 + 1G> A. Two patients (P9 and P18) had splice-site variants in trans with p.R535H or p.N409S, respectively, and both exhibited significant disease burden. Patient 9, treated with ERT, reported persistent bone pain and fatigue despite therapy, whereas Patient 18, treated with substrate reduction therapy (SRT), showed improvements in platelet count, hemoglobin, and lyso-Gb1 levels. These cases highlight the phenotypic variability of GD1 as well as the variable response of ERT to skeletal complications.

Parkinsonism was observed in three patients, all of whom were diagnosed with GD1 during their PD

Biomarker analysis further supports the clinical significance of our findings. Elevated lyso-Gb1 levels were observed at all time points, and it is likely that levels would have been even higher in specimens naïve to treatment. In contrast, CHITO activity was within the normal reference range in four patients, reinforcing the clinical utility of lyso-Gb1 as a specific and sensitive biomarker for GD[6,8].

Despite the strengths of our study, several limitations must be acknowledged. The retrospective design introduces potential selection and information bias, and the small sample size limits generalizability. However, the sample size we examined is proportionate to those reported in other studies of delayed diagnosis in GD1, a phenomenon not restricted to AJ or p.N409S homozygotes, but also observed in Australia, New Zealand, Romania, and France, where the number of AJ and p.N409S/p.N409S GD patients is considerably lower than in the United States[39]. Additionally, the inability to apply the full DS3 due to limited skeletal and visceral data may underestimate disease burden. Our cohort, drawn from two academic centers, may also not reflect diagnostic practices in community settings.

Nonetheless, our findings contribute to a growing body of evidence that GD1 in AJ individuals - particularly those diagnosed at ≥ 50 years - is often underrecognized and undertreated. The consistent presence of hallmark features and elevated lyso-Gb1 levels underscores the need for heightened clinical suspicion and earlier intervention. We advocate for inclusion of lyso-Gb1 in diagnostic algorithms and for broader awareness of GD1 in older adults, especially those of AJ ancestry or with a family history of GD or PD.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the providers who cared for the patients and their families. This work was supported by Duke University Health Systems and an Investigator-Initiated Award from Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA.

Authors’ contributions

Data curation, methodology, original draft preparation, and visualization of figures and tables: Stiles AR

Data curation, methodology, reviewing and editing, and patient consent/ethics: Jung SH

Formal analysis, data curation, methodology, and reviewing and editing: Evard R, Stauffer C

Statistical analysis, reviewing and editing: Abar B

Data curation and visualization of figures and tables and reviewing and editing: Menkovic I

Formal analysis, reviewing and editing, and patient consent/ethics: Fierro L

Supervision, reviewing and editing, and conceptualization: Kishnani PS, Balwani M

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality and institutional restrictions but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, with appropriate Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by an Investigator-Initiated Award from Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA.

Conflicts of interest

Balwani M is a member of the International Collaborative Gaucher Group (ICGG) Scientific Advisory Board and has received honoraria from Sanofi (Cambridge, MA, USA). Kishnani PS has received research and grant support from Sanofi Genzyme (Cambridge, MA, USA) and Takeda (Cambridge, MA, USA), and has received consulting fees and honoraria from both companies. Kishnani PS is also a member of the Gaucher Disease Registry Advisory Board for Sanofi Genzyme and a member of the Advisory Board for Takeda. Stiles AR has served on an advisory board for type 1 diabetes newborn screening and has received consulting fees from Sanofi (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study involved a retrospective review of medical records from patients with Gaucher disease followed at Duke University Medical Center (Durham, NC, USA) and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, NY, USA). Duke University patients (n = 5) participated in a research study approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board (IRB# Pro00088186) and provided written informed consent. Data from Mount Sinai patients (n = 15) were obtained via retrospective chart review under an approved waiver of consent from the Program for the Protection of Human Subjects (STUDY-23-01469). All procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant institutional guidelines and ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Luettel DM, Terluk MR, Roh J, Weinreb NJ, Kartha RV. Emerging biomarkers in Gaucher disease. In: Makowski GS, Editor. Advances in clinical chemistry. Elsevier; 2025. pp. 1-56.

2. Eijk M, Ferraz MJ, Boot RG, Aerts JMFG. Lyso-glycosphingolipids: presence and consequences. Essays Biochem. 2020;64:565-78.

3. Nilsson O, Svennerholm L. Accumulation of glucosylceramide and glucosylsphingosine (psychosine) in cerebrum and cerebellum in infantile and juvenile Gaucher disease. J Neurochem. 1982;39:709-18.

4. Orvisky E, Park JK, LaMarca ME, et al. Glucosylsphingosine accumulation in tissues from patients with Gaucher disease: correlation with phenotype and genotype. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;76:262-70.

5. Dekker N, van Dussen L, Hollak CE, et al. Elevated plasma glucosylsphingosine in Gaucher disease: relation to phenotype, storage cell markers, and therapeutic response. Blood. 2011;118:e118-27.

6. Curado F, Rösner S, Zielke S, et al.; LYSO-PROOF Study Group. Insights into the value of Lyso-Gb1 as a predictive biomarker in treatment-naïve patients with Gaucher disease type 1 in the LYSO-PROOF study. Diagnostics. 2023;13:2812.

7. Rolfs A, Giese AK, Grittner U, et al. Glucosylsphingosine is a highly sensitive and specific biomarker for primary diagnostic and follow-up monitoring in Gaucher disease in a non-Jewish, Caucasian cohort of Gaucher disease patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79732.

8. Zimran A, Revel-Vilk S, Dinur T, et al. Evaluation of Lyso-Gb1 as a biomarker for Gaucher disease treatment outcomes using data from the Gaucher outcome survey. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2025;20:43.

9. Scott SA, Edelmann L, Liu L, Luo M, Desnick RJ, Kornreich R. Experience with carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for 16 Ashkenazi Jewish genetic diseases. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:1240-50.

10. Balwani M, Fuerstman L, Kornreich R, Edelmann L, Desnick RJ. Type 1 Gaucher disease: significant disease manifestations in “asymptomatic” homozygotes. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1463-9.

11. Fan J, Hale VL, Lelieveld LT, et al. Gaucher disease protects against tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:e2217673120.

12. Grabowski GA, Kishnani PS, Alcalay RN, et al. Challenges in Gaucher disease: perspectives from an expert panel. Mol Genet Metab. 2025;145:109074.

13. Mehta A, Kuter DJ, Salek SS, et al. Presenting signs and patient co-variables in Gaucher disease: outcome of the Gaucher Earlier Diagnosis Consensus (GED-C) Delphi initiative. Intern Med J. 2019;49:578-91.

14. Castillon G, Chang SC, Moride Y. Global Incidence and prevalence of Gaucher disease: a targeted literature review. J Clin Med. 2022;12:85.

15. Mehta A, Belmatoug N, Bembi B, et al. Exploring the patient journey to diagnosis of Gaucher disease from the perspective of 212 patients with Gaucher disease and 16 Gaucher expert physicians. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;122:122-9.

16. Nishimura S, Ma C, Sidransky E, Ryan E. Obstacles to early diagnosis of Gaucher disease. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2025;21:93-101.

17. Fairley C, Zimran A, Phillips M, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of N370S homozygotes with type I Gaucher disease: an analysis of 798 patients from the ICGG Gaucher Registry. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:738-44.

18. Grabowski GKE, Weinreb N. Gaucher disease: phenotypic and genetic variation. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

19. Weinreb NJ, Aggio MC, Andersson HC, et al.; International Collaborative Gaucher Group (ICGG). Gaucher disease type 1: revised recommendations on evaluations and monitoring for adult patients. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:15-22.

20. Kaplan P, Baris H, De Meirleir L, et al. Revised recommendations for the management of Gaucher disease in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:447-58.

21. Charrow J, Andersson HC, Kaplan P, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy and monitoring for children with type 1 Gaucher disease: consensus recommendations. J Pediatr. 2004;144:112-20.

22. Baldellou A, Andria G, Campbell PE, et al. Paediatric non-neuronopathic Gaucher disease: recommendations for treatment and monitoring. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:67-75.

23. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-81.

24. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al.; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

25. Beasley J, McCaw P, Zhang H, Young SP, Stiles AR. Combined analysis of plasma or serum glucosylsphingosine and globotriaosylsphingosine by UPLC-MS/MS. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;511:132-7.

26. Weinreb NJ, Cappellini MD, Cox TM, et al. A validated disease severity scoring system for adults with type 1 Gaucher disease. Genet Med. 2010;12:44-51.

27. Kishnani PS, Al-Hertani W, Balwani M, et al. Screening, patient identification, evaluation, and treatment in patients with Gaucher disease: results from a Delphi consensus. Mol Genet Metab. 2022;135:154-62.

28. Zimran A, Kay A, Gelbart T, Garver P, Thurston D, Saven A, Beutler E. Gaucher disease. Clinical, laboratory, radiologic, and genetic features of 53 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1992;71:337-53.

29. Dinur T, Zimran A, Becker-Cohen M, et al. Long term follow-up of 103 untreated adult patients with type 1 Gaucher disease. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1662.

30. Yoldaş Çelik M, Canda E, Yazıcı H, et al. Insights into skeletal involvement in adult Gaucher disease: a single-center experience. J Bone Miner Metab. 2025;43:166-73.

31. Taddei TH, Kacena KA, Yang M, et al. The underrecognized progressive nature of N370S Gaucher disease and assessment of cancer risk in 403 patients. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:208-14.

32. Mistry PK, Sadan S, Yang R, Yee J, Yang M. Consequences of diagnostic delays in type 1 Gaucher disease: the need for greater awareness among hematologists-oncologists and an opportunity for early diagnosis and intervention. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:697-701.

33. Orenstein M, Barbouth D, Bodamer OA, Weinreb NJ. Patients with type 1 Gaucher disease in South Florida, USA: demographics, genotypes, disease severity and treatment outcomes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:45.

34. Marcucci G, Brandi ML. The diagnosis and therapy of osteoporosis in Gaucher disease. Calcif Tissue Int. 2025;116:31.

35. Di Rocco M, Di Fonzo A, Barbato A, et al. Parkinson’s disease in Gaucher disease patients: what’s changing in the counseling and management of patients and their relatives? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:262.

36. Rana HQ, Balwani M, Bier L, Alcalay RN. Age-specific Parkinson disease risk in GBA mutation carriers: information for genetic counseling. Genet Med. 2013;15:146-9.

37. Vieira SRL, Mezabrovschi R, Toffoli M, et al. Consensus guidance for genetic counseling in GBA1 variants: a focus on Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2024;39:2144-54.

38. Rossi M, Schaake S, Usnich T, et al. Classification and genotype-phenotype relationships of GBA1 variants: MDSGene systematic review. Mov Disord. 2025;40:605-18.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].