Autosomal dominant tibial muscular dystrophy in Estonia

Abstract

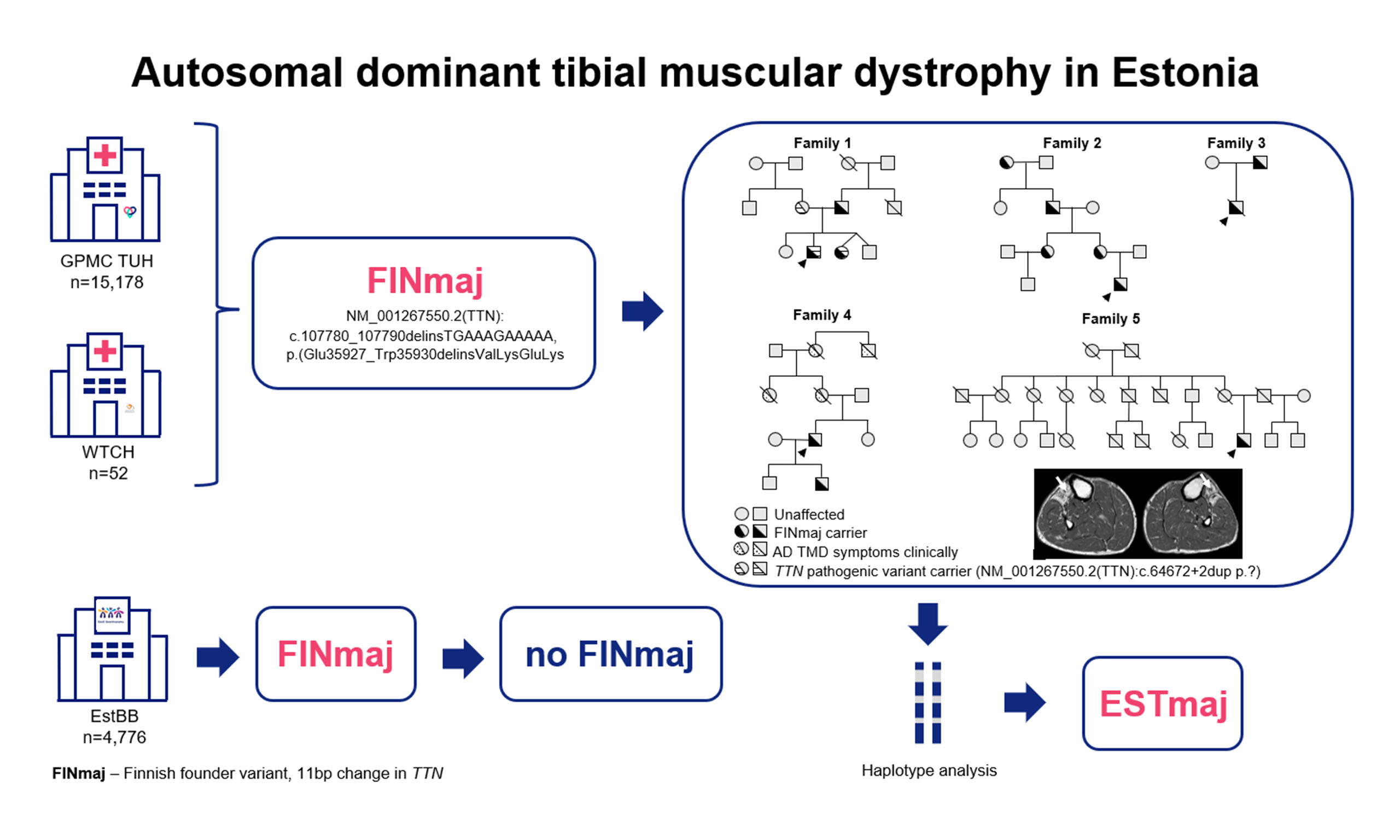

Aim: Tibial muscular dystrophy (TMD; MIM#600334, ORPHA:609) is an adult-onset, slowly progressive distal myopathy resulting from dominant variants in exon 364 of the TTN gene. The Finnish founder variant (FINmaj), characterized by an 11-bp insertion/deletion, causes autosomal dominant (AD) TMD in heterozygous individuals. Our aim was to assess the prevalence and origin of the FINmaj variant within the Estonian population.

Methods: We reanalyzed next-generation sequencing panels and whole-exome sequencing data from 2014 to 2025 to identify individuals carrying the FINmaj variant. The study included three cohorts: Tartu University Hospital (n = 15,178), West Tallinn Central Hospital (n = 52), and the Estonian Genome Center (n = 4,776). Most carriers of the FINmaj variant underwent muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and haplotype analysis.

Results: We identified 13 individuals from five families with the heterozygous FINmaj variant, including two individuals with autosomal recessive limb-girdle muscular dystrophy-10 and eleven with AD TMD. By the age of 50, all patients diagnosed with TMD showed symptoms of distal myopathy and characteristic MRI findings. The carrier frequency of the FINmaj variant in the Estonian cohort was one in 3,036, with no carriers in the Estonian Genome Center cohort. The average haplotype length was estimated to be ~4.1 Mb in Estonians, compared to

Conclusion: AD TMD is one of the most prevalent but underdiagnosed hereditary muscle diseases in the Estonian population. Since Estonian patients exhibit an estimated shorter haplotype length than Finnish patients, the FINmaj variant likely originated in Estonia before spreading to Finland.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Tibial muscular dystrophy (TMD; MIM#600334, ORPHA:609) is a rare autosomal dominant (AD) distal myopathy. AD TMD was first described by Hackman et al. in a large Finnish family with two distinct muscle disease phenotypes: a mild late-onset distal myopathy inherited in an AD pattern[1] and a severe limb-girdle muscular dystrophy-10 (LGMDR10) inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern[2,3]. The first muscle affected by AD TMD is the anterior tibial muscle. Clinically, it usually presents after age 35 as a weakness in ankle dorsiflexion and an inability to walk on heels, leading to a mild dropped foot 15-20 years after the onset of symptoms. Overall, the level of disability is mild, and patients typically remain mobile with the assistance of walking aids for the remainder of their lives[2,4]. Muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans reveal that the anterior tibial muscle in patients over 50 years of age has become atrophic and has been replaced by fat and connective tissue[4-9]. Muscle biopsy samples show progressive myopathic changes, including rimmed vacuoles in the early stages and the subsequent infiltration of muscle tissue with adipose tissue in the later stages of the disease[3,4].

The TTN gene (NM_001267550.2) consists of 364 exons and encodes titin, the largest protein identified in humans. Titin is imperative for the structural integrity, development, mechanical function, and regulation of cardiac and skeletal muscle[10,11]. The TTN gene comprises eight domains with distinct functions and over 300 repeat regions. This enables titin to act as an elastic scaffold that can withstand and respond to mechanical forces[12]. The exact number of repeats can vary slightly due to alternative splicing, which produces isoforms with different domain structures[10,13]. An 11-bp insertion/deletion in the last exon of the TTN is known as the Finnish founder variant (FINmaj). This variant occurs in Finland at a frequency of one in 2,000 people, with approximately 1,000 individuals affected by late-onset AD TMD, making it the most prevalent inherited muscle disease in the country[3,14-17]. Other pathogenic dominant variants in the final exon of TTN have been described in patients with TMD in Belgium, France, and Spain[1,14,18-20]. However, the FINmaj variant had not been reported outside Finland until 2024, when we identified it in an affected Estonian family presenting with both early-onset LGMDR10 and late-onset TMD[21].

To gain insight into the origins of genetic variants, single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) haplotype analysis is crucial. Shared haplotypes enable us to trace the ancestry of variants, determine their age, and differentiate mutations from those inherited from a common ancestor. This helps us understand how variants spread within populations, how people migrate, and the origins of genetic diseases.

The discovery of the FINmaj variant in an Estonian family without known Finnish ancestry led to a retrospective analysis, which aimed to estimate the carrier frequency and explore the origin of this variant in Estonia. It offers new insights into the variant's regional distribution.

METHODS

Study cohorts

This research was carried out as part of the European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP-RD) project IDOLS-G. We formed three cohorts to identify individuals harboring the FINmaj variant in the Estonian population.

The first cohort comprises patients undergoing next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis at the Genetics and Personalized Medicine Clinic of Tartu University Hospital (GPMC TUH) from 2014 to 2025. The GPMC TUH is the primary medical facility in Estonia that offers genetic services and molecular testing for patients. Therefore, the GPMC TUH data provide a cross-section of most patients suspected of having a genetic disease in Estonia. In this cohort (n = 15,178), we reanalyzed all the NGS data. Since January 1, 2022, TUH has been a member of the European Reference Network for Neuromuscular Diseases (ERN EURO-NMD) following its online accreditation in 2021.

The second cohort was established in collaboration with the West Tallinn Central Hospital (WTCH) and comprised 121 patients with unresolved myopathy and/or neuropathy. The group included individuals suspected of having Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT, n = 85), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA, n = 15), and unspecified myopathy (n = 21). From this larger cohort, 52 patients who had not previously undergone gene panel or whole-exome sequencing (WES) were selected. Sanger sequencing was performed on all 52 individuals to assess the presence of the FINmaj variant.

The third cohort consisted of individuals from the general Estonian population who had voluntarily donated blood to the Estonian Genome Center of the University of Tartu (EGCUT) for scientific research purposes. We reanalyzed the NGS data of the patients for whom a WES or a whole genome sequencing (WGS) was performed at EGCUT (n = 4,776). We calculated the frequency of TMD by dividing the number of genetically confirmed TMD cases by the total number of individuals in the GPMC TUH cohort.

Patients

Individuals with the FINmaj variant were referred to a clinical geneticist for evaluation at an outpatient clinic. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating families. Comprehensive clinical data were gathered, including patient demographics such as gender, age, nationality, and medical and family history. We collected clinical information and blood samples from the 18 family members who consented to DNA analysis. However, some individuals declined to participate in further investigations, and some with characteristic symptoms had passed away. Patients were referred to neurological consultations, muscle MRI investigations, and, in some cases, nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG), along with manual muscle force measurements to identify the affected muscles. Importantly, all symptomatic patients were already under the care of a neurologist. The muscle MRI investigation protocol was implemented at TUH in 2023, with Prof. Bjarne Udd re-evaluating selected cases to provide expert opinion. None of the families had a known Finnish ancestry spanning many generations.

Methods

Reanalysis of NGS data

In the GPMC TUH cohort (n = 15,178), we conducted a retrospective analysis of targeted gene panels, including TruSight One (TSO, n = 4,813 genes), TruSight One Expanded (TSOE, n = 6,794 genes), and WES (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA), to identify individuals carrying the FINmaj variant. The sequencing reads were aligned to the reference genome GRCh37 using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA)[22]. Variants were called by Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) tools, employing either the BWA Enrichment v2.1 workflow or the Illumina DRAGEN v.4.1 pipeline, along with the Enrichment workflow for mapping and variant calling (Illumina Inc.). Variants from the Variant Call Format (VCF) files were annotated using our in-house variant annotation pipeline, which incorporated Annovar[23], SnpSift[24], Variant Effect Predictor (VEP)[25], and GATK[26]. Copy number variation (CNV) detection was carried out using CoNIFER software[27].

The EGCUT cohort consisted of a high-coverage sequencing dataset, encompassing 4,776 individuals, including WES (n = 2,356) and WGS (n = 2,420) data. This cohort was also examined to identify individuals carrying the FINmaj variant.

Sanger sequencing

In the WTCH cohort (n = 52), we conducted Sanger sequencing to identify the heterozygous FINmaj variant (NM_001267550.2(TTN):c.107780_107790delinsTGAAAGAAAAA, p.(Glu35927_Trp35930delinsValLysGluLys) in the TTN gene. Also, this 11-bp insertion/deletion was further validated by Sanger sequencing in affected individuals from the study cohort and at-risk family members (n = 18). Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood and subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR), with amplification performed using the primers TTN_ex364F:ACTGGTAGAGGTAGACAAGCCA and TTN_ex364R:AGTGTAGAGTATAAGGGCACAGG. The resulting 447 bp PCR product was visualized using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, sequenced on an ABI PRISM 3730XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and subsequently analyzed with ChromasPro and Alamut Visual v1.9 software.

Muscle magnetic resonance imaging

MRI was performed on axial sections of the lower limbs in six patients, and on the upper and lower limbs in two patients with 1.5T Philips Ingenia (vs 5.6.1) equipment using both T1-weighted and short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences. Fatty infiltration and muscle degeneration were graded using the five-point Mercuri system (Grade 0: normal muscle; Grade IV: complete fat replacement)[28].

Haplotype analysis

A SNP haplotype analysis was performed on eleven Estonian and 27 Finnish TMD patients in the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM) at the University of Helsinki. The Finnish samples were selected from those with the shortest estimated haplotype according to previously performed microsatellite analysis[29]. The SNP genotype data were generated with Illumina Global Screening Array-24 v3.0 + multi-disease beadchip, and the genotypes were called with GenomeStudio 2.0.3 software. The haplotype lengths were estimated from SNP data by comparing genotypes of heterozygous and homozygous FINmaj variant carriers.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the frequency of TMD by dividing the number of genetically confirmed TMD cases by the total number of individuals in the GPMC TUH cohort.

RESULTS

Molecular findings

In the GPMC TUH cohort, we conducted a retrospective analysis of NGS data from 15,178 individuals and identified four patients carrying the FINmaj variant. Within the WTCH cohort (n = 52), we found one patient who also harbored the FINmaj variant. However, in the EGCUT cohort (n = 4,776), no individuals were found to carry the FINmaj variant.

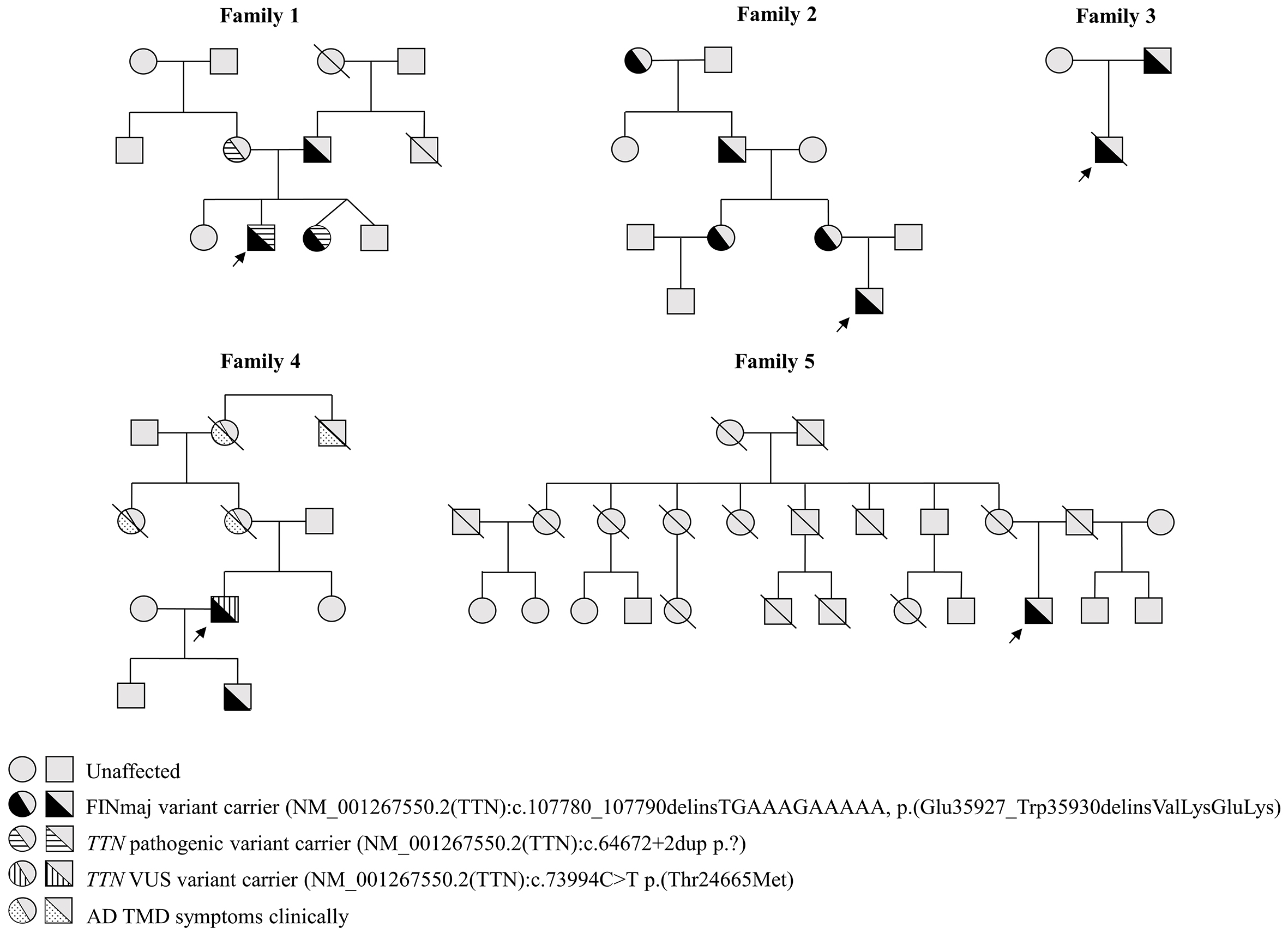

Among the 18 participating family members, the heterozygous FINmaj variant was molecularly confirmed in 13 individuals (nine males and four females) across five unrelated families [Figure 1]. One family and one member from another family refused to participate in further investigations. Additionally, some individuals with known symptoms had unfortunately passed away by the time of the survey. The carrier frequency of the FINmaj variant in the Estonian GPMC TUH cohort is one in 3,036. We identified two patients with AR LGMDR10 (MIM#608807, ORPHA:140922) and eleven with AD TMD. The two patients with LGMDR10 also harbor a second maternally inherited truncating TTN variant, NM_001267550.2:c.64672+2dup, in addition to the FINmaj variant [Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1][21].

Figure 1. Pedigrees of five families with a total of 13 individuals carrying the FINmaj variant. Arrows indicate index patients. Two individuals from Family 1 are diagnosed with autosomal recessive limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type R10 (AR LGMDR10; MIM #608807, ORPHA:140922), while eleven exhibit autosomal dominant tibial muscular dystrophy (AD TMD). In Family 1, affected individuals carry an additional maternally inherited truncating TTN variant. In Family 4, Individual 12 harbors a second TTN variant classified as a VUS.

Clinical findings

The youngest FINmaj variant carrier was diagnosed antenatally. In contrast, the oldest was diagnosed at 80 years of age, with the median age for the confirmed genetic diagnosis of AD TMD being 37 years. All individuals studied were of Estonian descent for at least three generations [Supplementary Table 1].

Among the FINmaj variant carriers, all patients over 50 years of age exhibited weakness and atrophy in the anterior compartment of the lower leg, particularly affecting the tibialis anterior muscle. In contrast, six carriers under the age of 50 reported no weakness or atrophy in the tibialis anterior muscle. However, five patients aged between 38 and 41 experienced leg pain after walking long distances or climbing to the fifth floor while carrying heavy bags. Additionally, two patients reported difficulty walking on their heels (Individuals 3 and 5, Supplementary Table 1).

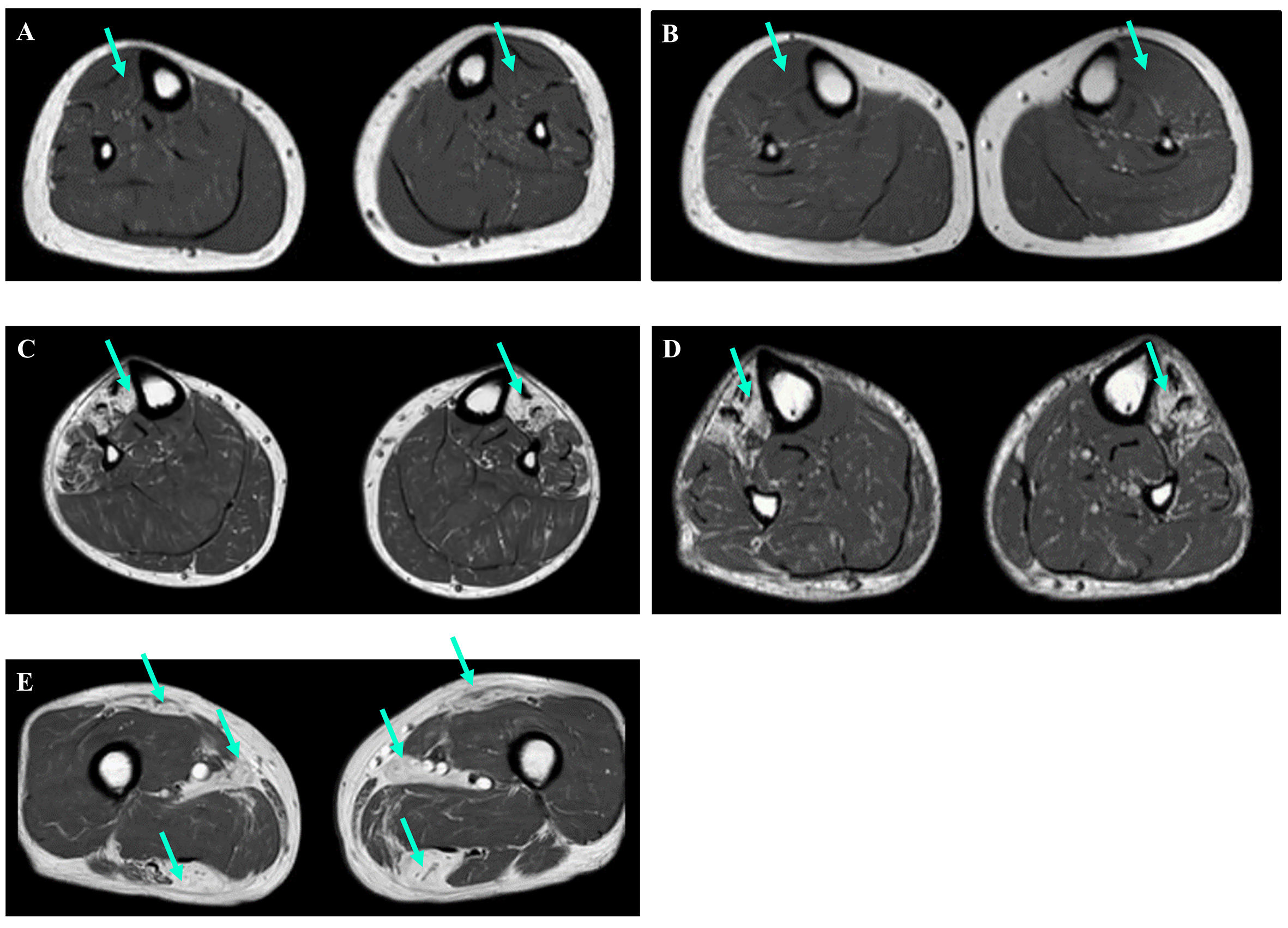

Eight FINmaj variant carriers underwent muscle MRI examinations [Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1]. Among them, three patients under the age of 50 exhibited no changes in the anterior muscles of the lower limb [Figure 2A and B]. In contrast, all patients over the age of 50 displayed signs of fatty degenerative changes. While the distribution of fatty replacement varied, a common finding was the involvement of the tibialis anterior muscle [Figure 2C and D]. Patients in the later stages of the disease, specifically those over 60 years of age, exhibited muscle atrophy and Mercuri grade IV fatty degeneration additionally in anterior and lateral distal leg muscles (extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, and fibularis longus muscles). The same changes were also noticed in the proximal hamstring muscles (biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus muscles) and minor gluteal muscles [Figure 2E]. Notably, the observations were asymmetric, with one side exhibiting more fatty degeneration than the other.

Figure 2. Muscle MRI images of the lower limbs (axial T1-weighted images). (A and B) Individuals 5 and 6, both under the age of 50, showed no signs of degeneration in their tibialis anterior muscles (green arrows). (C and D) In contrast, Individuals 7 and 12, both over the age of 50, displayed changes in their tibialis anterior muscles (green arrows). (E) Additionally, MRI results for Individual 12 revealed changes in the rectus femoris, adductor longus, and hamstring muscles (green arrows).

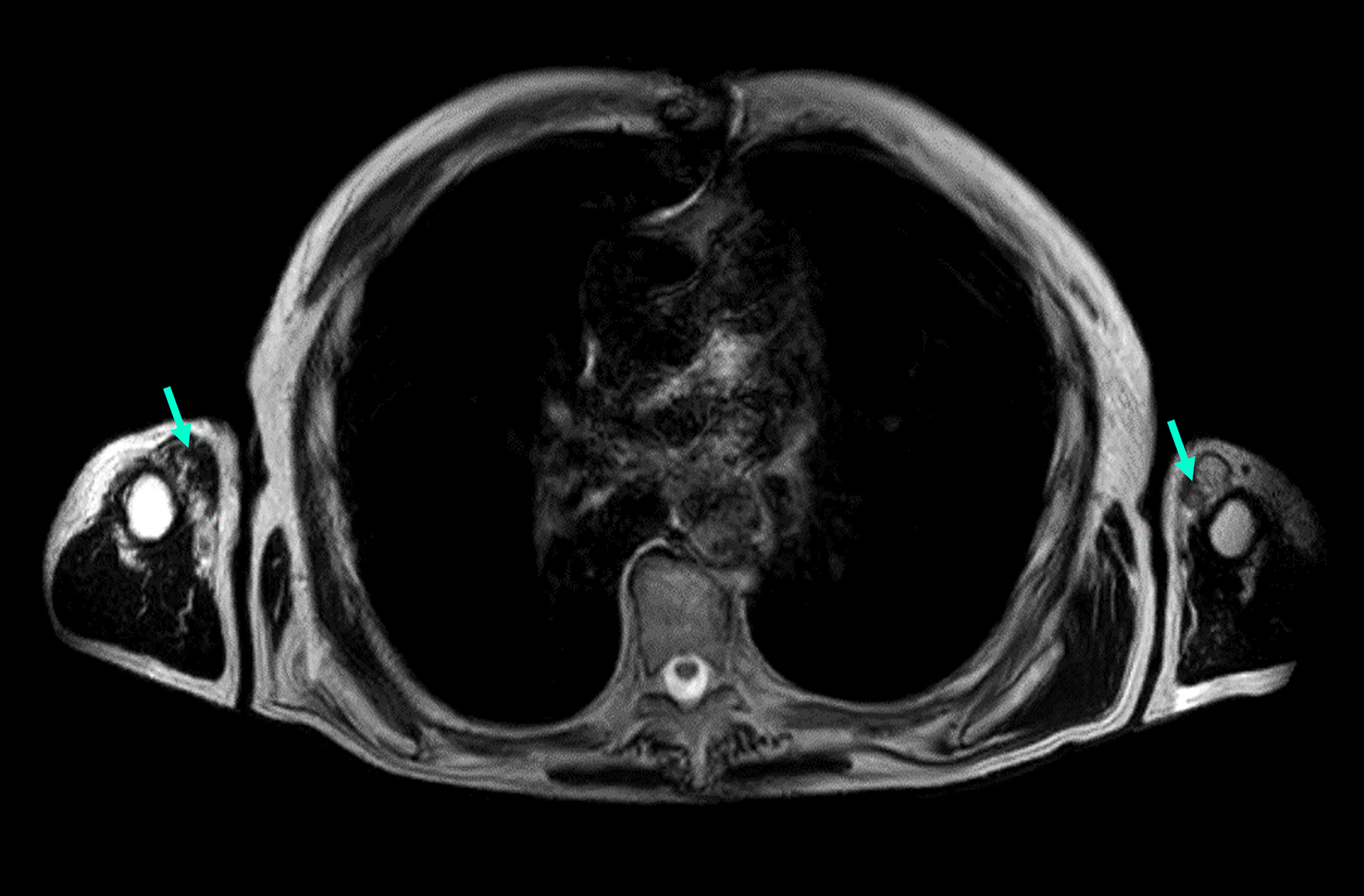

Individual 12 (currently in mid-70s) had a slowly progressive distal myopathy with disease onset in the fifth decade. On the last neurological examination, the patient had both waddling and steppage gait bilaterally

Figure 3. MRI image of an Individual 12 exhibiting proximal upper limb muscle involvement (axial T1-weighted images). The image demonstrates Mercuri grade IV fatty infiltration in the biceps (green arrows).

In addition to the FINmaj variant, Individual 12 also harbors a missense variant in TTN, specifically NM_001267550.2(TTN):c.73994C>T p.(Thr24665Met) [Supplementary Table 1]. Variant assessment tools that integrate data from multiple sources and utilize various algorithms, such as ClinVar[30], Varsome[31], and Franklin (Genoox, Tel Aviv, Israel)[32], have classified this variant as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS). Notably, it is not included in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) Pro[33]. In the general population, the variant is reported with a frequency of 0.0001 according to the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) (version 4.1.0)[34]. These programs yield differing assessments for the same genetic variant.

Bioinformatics

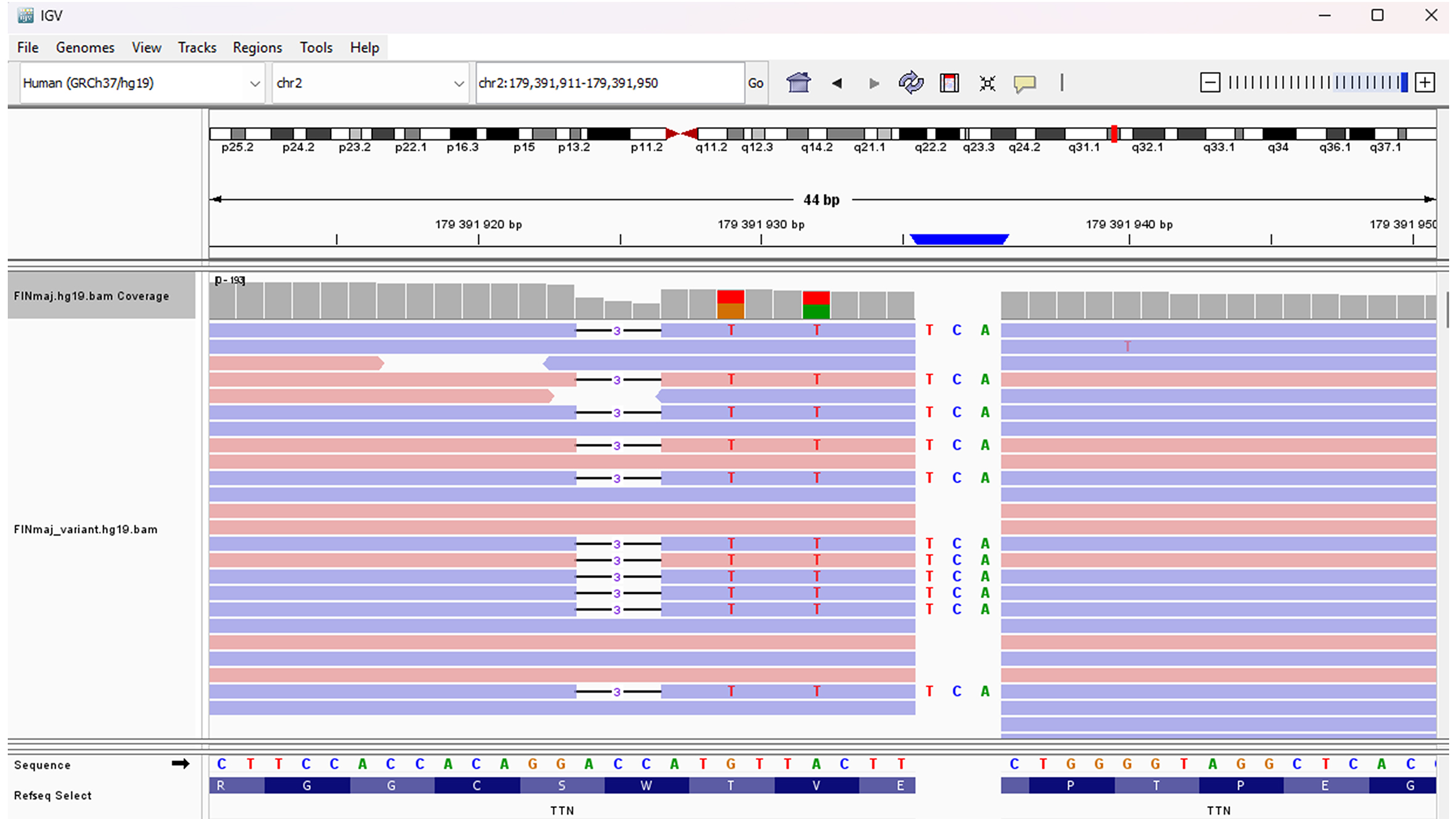

The FINmaj variant is an 11-bp insertion/deletion located at positions chr2:179,391,923-179,391,935 (GRCh37) within exon 364 of the TTN gene (2q31.2). The bioinformatics workflow, Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV), and gnomAD display the FINmaj variant as four sequence changes in TTN: a deletion, an insertion, and two missense variants [Table 1, Figure 4]. Although the FINmaj variant affects/involves four amino acids, it does not cause a frameshift or a stop codon. To date, 28 heterozygous carriers of the FINmaj variant have been documented in gnomAD v4.1.0[35].

Figure 4. Illustration of the FINmaj variant using IGV. The FINmaj variant is an 11-bp insertion/deletion at positions chr2:179,391,923-179,391,935 (GRCh37) in exon 364 of TTN (2q31.2) and is displayed as four different sequence changes.

Analysis of the FINmaj variant (GRCh37). The bioinformatics pipeline presents FINmaj as four distinct sequence alterations in TTN, which do not result in a frameshift or a stop codon

| TTN Position (GRCh37) | Ref. | Alt | Consequence | Impact | Clin-var | HGVS NM_001267550.2 | HGVSp NP_001254479.2 |

| 179,391,923 | GACC | G | Inframe deletion | moderate | - | c.107789_107791del | p.Trp35930del |

| 179,391,929 | G | T | missense | moderate | - | c.107786C>A | p.Thr35929Lys |

| 179,391,932 | A | T | missense | moderate | VUS | c.107783T>A | p.Val35928Glu |

| 179,391,935 | T | TTCA | Protein altering | moderate | - | c.107779_107780insTGA | p.Glu35927delinsValLys |

Haplotype analysis

SNP haplotype analysis revealed that Estonian patients (n = 11) have an estimated average haplotype length of ~4.1 Mb, while the Finnish patients (n = 27) selected from the shorter haplotype subset have an average length of ~5 Mb [Table 2].

Differences in haplotype length among TMD patients in Finland and Estonia

| Estimated average haplotype length (Mb) | Sample size | |

| Estonian patients | ~4.1 | 11 |

| Finnish patients* | ~5 | 27 |

DISCUSSION

For the first time, we provide an overview of patients with the FINmaj variant in the Estonian population. Haplotype analysis suggests that this variant may have originated in Estonia, located south of the Gulf of Finland. Previously, TTN variants identified in Estonia were primarily linked to cardiomyopathies and were the only variants routinely included in clinical diagnostics. The EJP-RD project IDOLS-G facilitated a broader investigation into TTN variants associated with skeletal muscle diseases. NGS has dramatically enhanced the detection of TTN variants related to neuromuscular disorders, overcoming previous challenges posed by the gene's size and complexity. Importantly, we have reported a case of early-onset titinopathy, specifically LGMDR10, attributed to compound heterozygosity involving the FINmaj and truncating TTN variants[21]. This underscores the clinical importance of incorporating the FINmaj variant into diagnostic workflows.

Four patients from the GPMC TUH cohort (n = 15,178) and one patient from the unsolved myopathy/neuropathy WCHT cohort (n = 52) harbored the FINmaj variant [Supplementary Table 1]. Based on the clinical cohort data, the estimated carrier frequency of the FINmaj variant in Estonia is one in 3,036. This figure is comparable to Finland, where the carrier frequency is estimated to be around 1 in 2,000, with over 1,000 patients in a population of 5.5 million[17]. However, it should be noted that this estimate may be somewhat inflated, as it encompasses patients with a wide variety of clinical indications, rather than reflecting the general population. In the EGCUT cohort, which represents the Estonian general population, the FINmaj variant was not detected, potentially due to the small sample size (n = 4,776). At the time of this study, EGCUT had a limited number of sequenced samples; however, as more sequence data from a population-based biobank becomes available, these frequency estimates could become more accurate. The gnomAD (v4.1.0) database, which reflects the general population, identifies 28 carriers of the FINmaj variant: 26 from the “European (Finnish)” group and two from the “Remaining” genetic ancestry group. However, current methods do not allow for proper labeling of these individuals[36]. Based on the estimated carrier frequency, it is anticipated that there are around 500 carriers in Estonia, with approximately 250 symptomatic TMD patients.

The GPMC TUH cohort is substantial; however, potential bias may arise due to its referral-based approach to patient inclusion. Patients are typically referred by clinical geneticists or other healthcare professionals for targeted NGS panels or WES, based on the presence of symptoms indicative of muscle disease, neurodevelopmental disorders, connective tissue disorders, metabolic syndromes, infertility, or other rare clinical phenotypes. The cohort also includes individuals with hereditary cancers and healthy family members. Despite its size, the proportion of individuals with myopathy and/or neuropathy is relatively small. Additionally, the study does not represent the entire population of myopathic patients in Estonia, as some patients may seek care at other institutions or pursue genetic testing through private laboratories, either domestically or internationally.

The WTCH is one of the leading adult neuromuscular disease care centers in Estonia. The hospital's clinical expertise and diagnostic capabilities position it as a key partner in advancing research on neuromuscular disorders. Patients from WTCH were selected for this study. The relatively small size of this cohort may be due to clinicians' limited awareness of the FINmaj variant and the difficulties associated with diagnosing rare and unfamiliar conditions.

Of 18 participating family members, 13 carry the FINmaj variant, leading to a relatively small patient cohort [Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1]. Individuals harboring the FINmaj variant may remain unidentified due to several challenges. Some individuals exhibit mild symptoms, such as an altered gait, and may not seek medical attention. Others may have passed away, or patients might have been unreachable or declined the follow-up appointments. Our research identified ten individuals who remain undiagnosed due to these challenges. This complicates our efforts to obtain an accurate prevalence estimate and suggests that TMD might be underdiagnosed, a concern previously noted already in Finland[17].

Similar to the Finnish data, all four patients over the age of 50 years exhibited progressive weakness of the tibialis anterior muscle, difficulties with foot dorsiflexion, and fatty replacement of the distal lower limb muscles. By the age of 70 years, they also demonstrated changes in their proximal leg muscles [Figure 2C-E, Supplementary Table 1].

One patient (Individual 12) in our cohort exhibited upper body involvement and weakness, a condition that has been documented in one Finnish AD TMD patient (unpublished). The reason for this patient's arm involvement remains unclear, but it may be attributed to another alteration in the TTN gene or a different gene altogether. To date, only one VUS variant has been identified (NM_001267550.2(TTN):c.73994C>T, p.(Thr24665Met), which has an unclear impact on the atypical phenotype [Supplementary Table 1].

The FINmaj variant has often been overlooked in standard molecular reporting workflows due to the complex alteration of 11 base pairs in the M-band domain of the large titin protein, which is encoded by exon 364 of the TTN gene [Table 1]. Since this variant does not cause a frameshift or introduce a stop codon, it poses significant challenges for detection using conventional bioinformatics and pathogenicity assessment tools. Currently, there is no straightforward method to identify the FINmaj variant during routine bioinformatics analyses, necessitating individual checks each time. This limitation likely contributes to its underdiagnosis in Estonia and other countries. However, the implementation of long-read genome sequencing is expected to improve the detection of this complex insertion/deletion variant[37,38]. Consequently, until long-read sequencing becomes widely available, it is essential for molecular geneticists to specifically screen for the FINmaj variant in individuals with suspected muscle disease.

SNP haplotype analysis in repeated regions is crucial for distinguishing between older, ancestral alleles and newer, expanded variants. This approach offers significant insights into genetic heritage, population migrations, and potential disease associations. Our study group was particularly interested in uncovering any common ancestry related to the FINmaj variant and determining whether this founder pathogenic variant originated in Estonia or Finland. The estimated average haplotype length for Estonians is around 4.1 Mb. In contrast, Finnish patients (n = 27) chosen from the shorter haplotype subset exhibit an average length of approximately 5 Mb. This suggests that the FINmaj variant may be a founder variant originating in Estonia. However, this finding requires further investigation with additional TMD samples from Estonia, given the small sample size.

As previously mentioned, this study encountered several limitations. The small population size and restricted cohort made it difficult to draw broader conclusions, and low awareness of the disease contributed to challenges in recruitment. Although most neuromuscular disorder patients in Estonia are evaluated at TUH, there is a possibility that some cases are not included in the GPMC TUH cohort. Furthermore, certain individuals opted not to participate in clinical or genetic studies, which further limited the data collected. It is also important to recognize that participation in biobanks such as EGCUT may be biased towards those who are more mobile and health-conscious. Consequently, symptomatic FINmaj carriers, particularly those with reduced mobility or complex health issues, may be underrepresented in the cohort. This potential selection bias further restricts the ability to draw definitive conclusions from the current dataset. Additionally, in the absence of automated detection, the FINmaj variant remains underdiagnosed in many cases. These factors were beyond the researchers' control and illustrate the common challenges associated with studying rare conditions in small populations.

In conclusion, distal titinopathy caused by the FINmaj variant is one of the most common hereditary muscle diseases in Estonia, alongside other prevalent conditions such as SMA, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and myotonic dystrophy. Due to its late onset, slow progression, and the challenges in bioinformatic detection of variants, we believe that titinopathy is underdiagnosed in Estonia. This work aims to raise awareness of titinopathy, particularly the FINmaj genetic variant, which has been identified as having originated in Estonia.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families for agreeing to be part of this study. LV and BU are members of the European Reference Network for Neuromuscular Diseases ERN-NMD - Project ID n°101156434.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: Sarv S, Väli L, Kahre T, Savarese M, Hackman P, Udd B, Õunap K.

Performed data acquisition, as well as provided administrative, technical, and material support: Reimand T, Õiglane-Shlik E, Puusepp S, Pajusalu S, Murumets Ü, Turku T, Põlluaas L, Mihkla L, Ütt S, Gross-Paju K.

Gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that any issues related to accuracy or integrity are properly investigated and resolved: Sarv S, Reimand T, Õiglane-Shlik E, Puusepp S, Pajusalu S, Murumets Ü, Turku T, Põlluaas L, Mihkla L, Ütt S, Gross-Paju K, Väli L, Kahre T, Savarese M, Hackman P, Udd B, Õunap K

Availability of data and materials

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was supported by the Estonian Research Council grants PRG471, PRG2040, and PSG774, and funding IDOLS-G from the Estonian Social Ministry and the Research Council of Finland as a part of the European Joint Program on Rare Diseases (EJP-RD). General funding for titinopathy research was provided by the Samfundet Folkhälsan Foundation and the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu (Certificates No. 327/T-3, 366/M-6, 371/M-13, and 374/M-8, 387/M-15, 399/M-12), and by the Research Ethics Committee of the HUS Helsinki University Hospital (HUS/16896/2022). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Hackman P, Vihola A, Haravuori H, et al. Tibial muscular dystrophy is a titinopathy caused by mutations in TTN, the gene encoding the giant skeletal-muscle protein titin. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:492-500.

2. Udd B, Kääriänen H, Somer H. Muscular dystrophy with separate clinical phenotypes in a large family. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14:1050-8.

3. Udd B, Partanen J, Halonen P, et al. Tibial muscular dystrophy. Late adult-onset distal myopathy in 66 finnish patients. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:604-8.

4. Haravuori H, Mäkelä-Bengs P, Udd B, et al. Assignment of the tibial muscular dystrophy locus to chromosome 2q31. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:620-6.

5. Udd B, Lamminen A, Somer H. Imaging methods reveal unexpected patchy lesions in late onset distal myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991;1:279-85.

6. Bugiardini E, Morrow JM, Shah S, et al. The diagnostic value of MRI Pattern recognition in distal myopathies. Front Neurol. 2018;9:456.

7. Udd B. Limb-girdle type muscular dystrophy in a large family with distal myopathy: homozygous manifestation of a dominant gene? J Med Genet. 1992;29:383-9.

8. Hayes LH, Neuhaus SB, Donkervoort S, et al. Taking on the Titin: muscle imaging as a diagnostic marker of biallelic TTN-related myopathy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2024;11:1211-20.

9. Gómez-Andrés D, Costa-Comellas L, Díaz-Manera J, et al. Different lower limb muscle MRI patterns in autosomal dominant titinopathies. Eur J Neurol. 2025;32:e70348.

10. Bang ML, Centner T, Fornoff F, et al. The complete gene sequence of titin, expression of an unusual approximately 700-kDa titin isoform, and its interaction with obscurin identify a novel Z-line to I-band linking system. Circ Res. 2001;89:1065-72.

11. Savarese M, Sarparanta J, Vihola A, et al. Panorama of the distal myopathies. Acta Myol. 2020;39:245-65.

13. Guo W, Bharmal SJ, Esbona K, Greaser ML. Titin diversity-alternative splicing gone wild. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:753675.

14. Hackman P, Marchand S, Sarparanta J, et al. Truncating mutations in C-terminal titin may cause more severe tibial muscular dystrophy (TMD). Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18:922-8.

15. Evilä A, Vihola A, Sarparanta J, et al. Atypical phenotypes in titinopathies explained by second titin mutations. Ann Neurol. 2014;75:230-40.

16. Savarese M, Vihola A, Oates EC, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in recessive titinopathies. Genet Med. 2020;22:2029-40.

17. Lillback V, Savarese M, Sandholm N, Hackman P, Udd B. Long-term favorable prognosis in late onset dominant distal titinopathy: Tibial muscular dystrophy. Eur J Neurol. 2023;30:1080-8.

18. Van den Bergh PY, Bouquiaux O, Verellen C, et al. Tibial muscular dystrophy in a Belgian family. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:248-51.

19. Pollazzon M, Suominen T, Penttilä S, et al. The first Italian family with tibial muscular dystrophy caused by a novel titin mutation. J Neurol. 2010;257:575-9.

20. Evilä A, Palmio J, Vihola A, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals novel TTN mutations causing recessive distal titinopathy. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:7212-23.

21. Õunap K, Reimand T, Õiglane-Shlik E, et al. TTN-related muscular dystrophies, LGMD, and TMD, in an estonian family caused by the finnish founder variant. Neurol Genet. 2024;10:e200199.

22. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754-60.

23. Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164.

24. Cingolani P, Patel VM, Coon M, et al. Using drosophila melanogaster as a model for genotoxic chemical mutational studies with a new program, SnpSift. Front Genet. 2012;3:35.

25. McLaren W, Gil L, Hunt SE, et al. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122.

26. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The genome analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297-303.

27. Krumm N, Sudmant PH, Ko A, et al. Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1525-32.

28. Mercuri E, Pichiecchio A, Allsop J, Messina S, Pane M, Muntoni F. Muscle MRI in inherited neuromuscular disorders: past, present, and future. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:433-40.

29. Lehtonen J, Sulonen AM, Almusa H, et al. Haplotype information of large neuromuscular disease genes provided by linked-read sequencing has a potential to increase diagnostic yield. Sci Rep. 2024;14:4306.

30. Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D980-5.

31. Kopanos C, Tsiolkas V, Kouris A, et al. VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:1978-80.

32. Franklin by Genoox. The Future of Genomic Medicine. Available from: https://franklin.genoox.com/clinical-db/home/ [Last accessed on 26 Nov 2025].

33. Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, et al. The human gene mutation database: towards a comprehensive repository of inherited mutation data for medical research, genetic diagnosis and next-generation sequencing studies. Hum Genet. 2017;136:665-77.

34. Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434-43.

35. FINmaj variant. chr2-178527195-178527209 | gnomAD v4.1.0 | gnomAD. Available from: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/region/2-178527195-178527209?dataset=gnomad_r4 [Last accessed on 26 Nov 2025].

36. Genetic Ancestry in gnomAD | gnomAD. Available from: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/help/ancestry [Last accessed on 26 Nov 2025].

37. Perrin A, Van Goethem C, Thèze C, et al. Long-reads sequencing strategy to localize variants in TTN repeated domains. J Mol Diagn. 2022;24:719-26.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].