Accelerating materials discovery via AI-Agent integration of large language models and simulation tools

Abstract

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with materials science is driving a paradigm shift in how functional materials are discovered and designed. In this work, we present an AI-Agent platform that leverages large language model-driven reasoning to assist users in designing and executing computational workflows for materials research. Rather than relying on rigid pipelines, the Agent interprets natural language prompts, dynamically assembles task-specific workflows from existing simulation tools, and executes calculations accordingly. To illustrate its capabilities, we show two representative cases: (i) a goal-driven electronic structure calculation for periodic monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides, and (ii) an inverse design of battery electrolyte additives based on user-defined targets for molecular weight and frontier orbital energies. These examples illustrate the Agent’s capacity to translate high-level design intent into coordinated multi-tool operations, thereby streamlining complex workflows and lowering the entry barrier for non-expert users. As AI continues to advance, the Agent is poised to become an increasingly valuable partner in materials research, enhancing efficiency and improving design quality, and enabling broader access to materials discovery.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

With the exponential growth of computational power and continuous advancements in algorithmic models, computational materials science has evolved from a tool for interpreting experimental phenomena into a core engine for goal-driven materials design[1,2]. Leveraging quantum mechanics, molecular dynamics, and multiscale simulation methods, researchers are now able to probe the intricate relationships of material properties with atomic, molecular and crystal structures, as well as quantify the influence of processing techniques on microstructural evolution, thus overcoming the limitations of traditional trial-and-error approaches[3,4]. The integration of machine learning (ML) with high-throughput computing has further accelerated this transformation[5-7]. Intelligent predictive models that map structure-property-processing relationships, combined with multiscale simulations (ab initio → molecular dynamics → phase-field methods) and automated feedback loops, have enabled a paradigm shift from empirical screening to on-demand design[8-10]. This synergistic co-design of performance, processing, and structure, which may also integrate with manufacturing workflows, offers a seamless bridge from discovery to deployment, significantly reducing barriers to industrial application.

High-throughput virtual screening strategies, driven by the principles of Materials Genome Engineering (MGE), are already shortening development cycles and yielding disruptive materials for energy, electronics, and beyond[11-18]. Yet, according to the standard MGE paradigm, the design of new materials still requires researchers to manually integrate high-throughput simulation platforms, structure-property regression models, and inverse design tools, often guided by expert intuition and system-specific heuristics[19,20]. This process involves coordinating a diverse set of computational software, multiscale physical models, ML algorithms, and databases[21,22]. Such integration imposes steep learning curves and considerable development overhead, demanding interdisciplinary expertise and often resulting in rigid, non-transferable workflows that are tailored to some narrow domains.

This raises a critical question: Can we construct an intelligent system capable of autonomously designing workflow and dynamically composing tools to adapt to diverse material design tasks? Recent breakthroughs in large language models (LLMs), particularly those with advanced reasoning capabilities, have made such systems, artificial intelligence (AI) Agents. increasingly feasible[23-26]. The concept of an “Agent” was first introduced in 1973 by Hewitt et al. through the Actor Model, which formalized key characteristics such as autonomy, reactivity, and interactivity[27]. While long dormant, this concept has been revitalized with the emergence of LLMs in 2022[28]. Modern AI Agents leverage LLMs as cognitive engines, integrating modules for perception, memory, decision-making, planning, execution, and learning into a cohesive, closed-loop architecture: Understanding needs → Planning pathways → Invoking tools → Executing tasks → Evaluating results → Dynamic optimization[29-31]. Such Agents are capable of autonomously achieving complex goals, refining their workflows based on interaction history, and dynamically generating customized task sequences.

Recent advances across multiple scientific disciplines underscore the transformative potential of LLM-based AI Agents in automating complex, domain-specific workflows[32-38]. In spectral analysis, the SpeLL Agent (an Agent for Natural Language-Driven Intelligent Spectral Modeling) enables end-to-end modeling of near-infrared (NIR) spectra by generating domain-specific analytical scripts and using historical datasets to guide algorithm selection[32]. In computational biology, ProtChat integrates GPT-4 with protein-specific language models to automate tasks such as protein property prediction and protein-drug interaction analysis, significantly lowering the technical barrier for non-expert users[33]. In the chemical sciences, the dZiner Agent performs rational inverse molecular design by extracting domain knowledge from scientific literature and iteratively refining candidate compounds using surrogate models[34]. Similarly, symbolic regression frameworks have shown that LLM-based Agents can uncover interpretable material laws, such as descriptors for the glass-forming ability of metallic glasses[35]. For materials data extraction and synthesis planning, the Eunomia Agent uses zero-shot learning to convert unstructured scientific text into structured datasets, while the MOFsyn Agent accelerates experimental workflows by optimizing metal-organic framework (MOF) synthesis protocols through natural language interaction and mechanism-aware reasoning[36]. However, these agents are typically designed for defined application scenarios, with relatively linear workflows. In contrast, materials design often requires significantly more complex workflow planning, involving the integration of quantum chemistry, molecular dynamics, and high-throughput simulations under diverse constraints and objectives - posing greater challenges to the reasoning and orchestration capabilities of LLM-based systems. Moreover, the highly repetitive nature of constructing similar workflows across different systems underscores the need for agents that can generalize workflow design patterns and alleviate researchers from the burden of manually configuring routine processes. Realizing such capability would not only enhance automation and scalability but also allow domain experts to focus more on scientific insight and decision-making.

To address this, we present an LLM-based collaborative materials design Agent, empowered by sequential reasoning and the Reasoning and Action (ReAct) framework[39]. By seamlessly integrating LLMs with a suite of computational materials science tools and databases, the Agent constructs simulation workflows, dynamically refines task plans in response to intermediate results, and establishes a fully closed-loop research and development system. The Agent supports a broad spectrum of computational tools, including first-principles simulation engines, molecular design and screening platforms, and ML models, thereby enabling unified handling of both periodic crystalline systems and molecular compounds. Using Model Context Protocol (MCP)[40], the Agent can flexibly invoke the most appropriate tools based on task objectives, accuracy requirements, and computational constraints. Its modular and extensible architecture allows seamless adaptation to a wide range of materials design tasks, including band structure prediction, molecular property screening, structure generation, and multi-objective optimization. We validate the generality and effectiveness of the Agent through representative case studies in both inorganic and organic domains, such as the electronic structure evaluation of two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors and the inverse design of electrolyte additives targeting specific energy levels. These results demonstrate the Agent’s ability to make context-aware decisions, adapt its strategy through real-time feedback, and efficiently converge toward optimal solutions across diverse materials spaces. Taken together, this work proposes a scalable paradigm for intelligent materials design - reducing human intervention while enhancing adaptability, reusability, and design efficiency - and demonstrates its application in the design of 2D semiconductors and electrolyte additives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

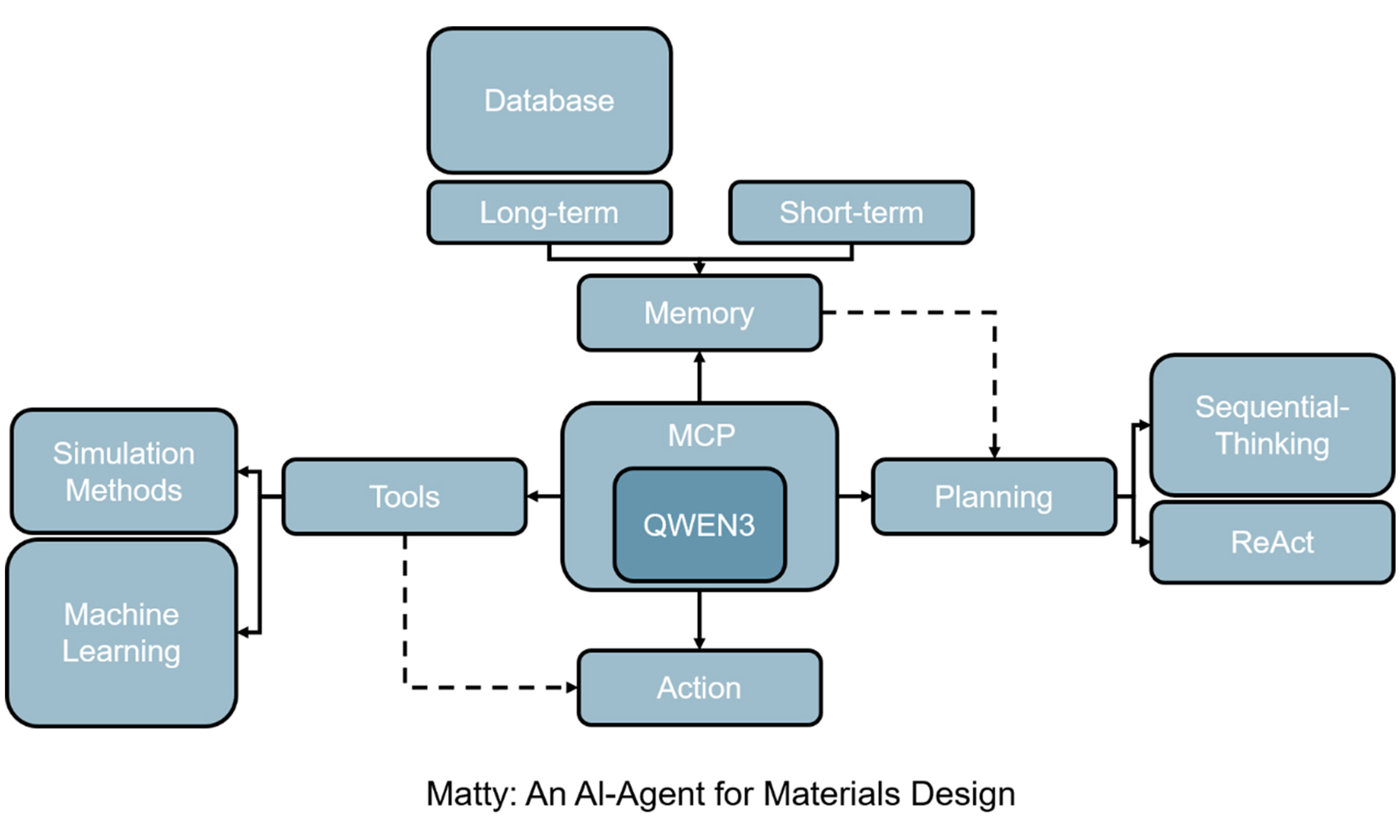

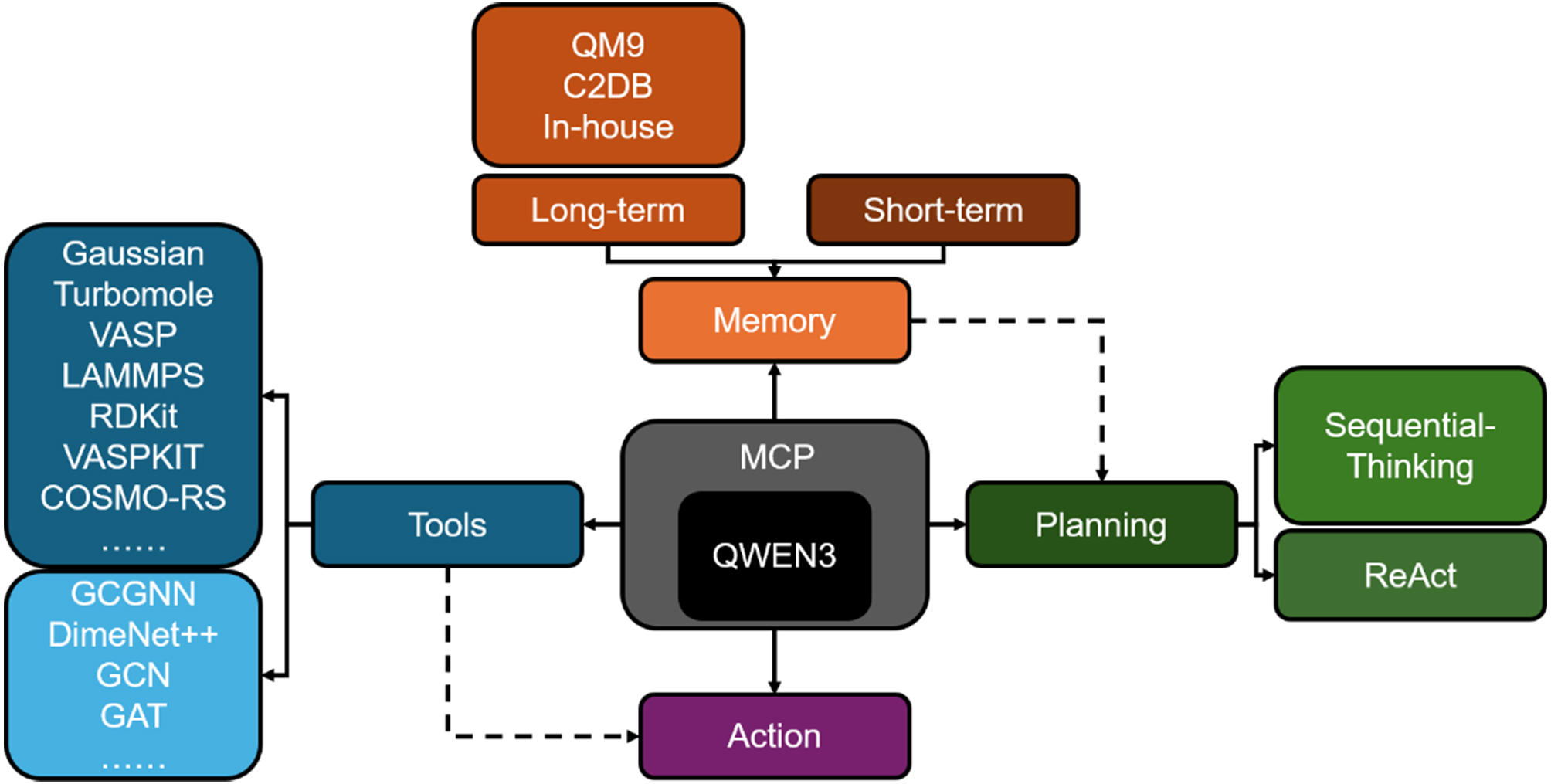

To support intelligent and adaptive materials design, we developed an AI-Agent system, Material Buddy (Matty), capable of autonomously constructing and executing complex simulation workflows. As illustrated in Figure 1, Matty is built upon LLM-driven architecture that tightly couples sequential reasoning with ReAct. At the core of the system is the Qwen3-235B-A22B-FP8[41] LLM, which serves as the cognitive engine for natural language understanding, task decomposition, and strategic planning. Matty also adopts the MCP, a standardized interface that facilitates seamless integration of diverse computational tools. Leveraging the MCP service, Matty can dynamically plan, invoke, and execute tasks in a stepwise fashion by autonomously translating high-level material design objectives into actionable workflows. Built on this LLM + MCP framework, Matty integrates a comprehensive suite of software tools spanning structure perception, data-driven memory, decision-making, simulation, and ML. These tools are organized into five functional modules - perception, memory, decision & planning, execution, and learning & optimization - forming a flexible and extensible platform capable of handling a wide range of design tasks across molecular and crystalline materials domains.

Figure 1. AI-Agent for material design. AI: Artificial Intelligence; QM9: Quantum Machine 9; C2DB: Computational 2D Materials Database; 2D: two-dimensional; VASP: Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package; LAMMPS: Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator; RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics Software Toolkit; VASPKIT: VASP Toolkit; COSMO-RS: Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents; GCGNN: Graph Convolutional Graph Neural Network; DimeNer++: Directional Message Passing Neural Network++; GCN: Graph Convolutional Networks; GAT: Graph Attention Networks; MCP: Model Context Protocol; QWEN3: Qwen3-235B-A22B-FP8 model.

As shown in Figure 1, our Agent system is developed with the Qwen3-235B-A22B-FP8 model as its core intelligence provider. The LLM model not only equips Agents with robust text comprehension and task planning capabilities, but also natively supports the MCP, enabling seamless integration with diverse external tools. This protocol offers standardized tool interfaces, allowing the model to drive structured reasoning workflows without requiring additional training. The Agent directly invokes the Sequential Thinking MCP service, enabling dynamic planning and step-by-step execution of complex tasks. Based on LLM + MCP framework, a series of tools are integrated into the Agent, and the information regarding the scope of application, precision, and cost is also provided for ReAct (see Table 1):

Main calculation tools supported by the Agent, with selected information included in tool metadata for ReAct

| Software/tool | System type | Typical system size (atoms) | Accuracy rating | Computational cost | Optimization time reference |

| Gaussian | Molecular | 50-200 |  | High | 0.5-2 h |

| Turbomole | Molecular | 50-500 |  | Medium | 0.3-1 h |

| XTB | Molecular/Periodic | 100-1,000 |  | Medium | 0.2-0.5 h |

| VASP | Periodic | 50-200 |  | High | > 2 h |

| LAMMPS | Molecular/periodic | 103-106 |   | Low | 1 s |

| DimeNet++ | Molecular | 50-100 |  | Medium | 1 min |

| CGCNN | Periodic crystal | 100-1,000 |  | Medium | Seconds for inference |

Perception: RDKit Toolkit[42], Python Materials Genomics (Pymatgen)[43], Materials Project Application Program Interface (MP API)[44], PubChem API[45];

Memory (Long-Term): Quantum Machine 9 (QM9)[46], Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB)[47] and in-house database with My Structured Query Language (MySQL)[48];

Decision & planning: Sequential-Thinking combined with ReAct framework[39];

Execution with tools:

Computational tools: Gaussian[49], Turbomole & Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents (COSMO-RS)[50], Extended Tight Binding (XTB)[51], Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)[52], Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS)[53], Multiwfn[54], etc.

Machine learning tools: Gaussian process regression with Scikit-learn[55,56], Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization with BoTorch[57], Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE)[58], Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)[59], Graph Attention Networks (GAT)[60], DimeNet/DimeNet++[61], Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNN)[62] with Torch[63] and Torch-geometric[64].

Learning & optimization: Auto update database and ML models.

Given the relatively simple workflow of material computational design, we implemented Agent construction using LangChain[65] and the MCP Python Software Development Kit[66]. The Agent adopted a hybrid local/remote deployment architecture: the decision core and lightweight tools (LangChain, RDKit, etc.) were hosted on a 32-core workstation, while computationally intensive tools (Gaussian, VASP, LAMMPS, etc.) were deployed remotely and connected via the Server-Sent Events protocol.

To ensure that dynamically assembled workflows are both methodologically valid and logically coherent, we implement a rigorous tool governance mechanism within Agent. Each tool is further encapsulated using the MCP, which provides explicit metadata for describing tool capabilities and applicability. As shown in Table 1, metadata defines input/output formats, applicable systems and execution rules of tools. Metadata acts as a prompt, allowing the Agent to understand the tool’s usage and assemble reasonable workflows. When a task is initiated, the Agent combines the user’s objective and tools’ metadata via the MCP interface to perform goal-oriented reasoning, translating natural language instructions into executable workflows. By combining structured constraints with descriptive prompts, the system ensures that each generated workflow is not only executable but also scientifically valid and reproducible.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To evaluate the generality, robustness, and cross-domain applicability of our Agent, we present two representative case studies encompassing both periodic and molecular material systems. The first case focuses on a fully autonomous electronic structure calculation of monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)[67], a prototypical 2D semiconductor, which highlights the Agent’s capacity to orchestrate end-to-end density functional theory (DFT) workflows for periodic materials. The second case addresses the generative design and multi-property evaluation of electrolyte additive molecules for lithium-ion batteries[68], demonstrating the integration of conditional generative models, quantum chemical calculations, and solvation theory within a closed-loop inverse design pipeline. Collectively, these case studies illustrate the Agent’s flexibility in addressing diverse materials design challenges, its ability to perform multi-step reasoning and decision-making.

AI-Agent-enabled autonomous workflow for periodic TMDs: a representative example

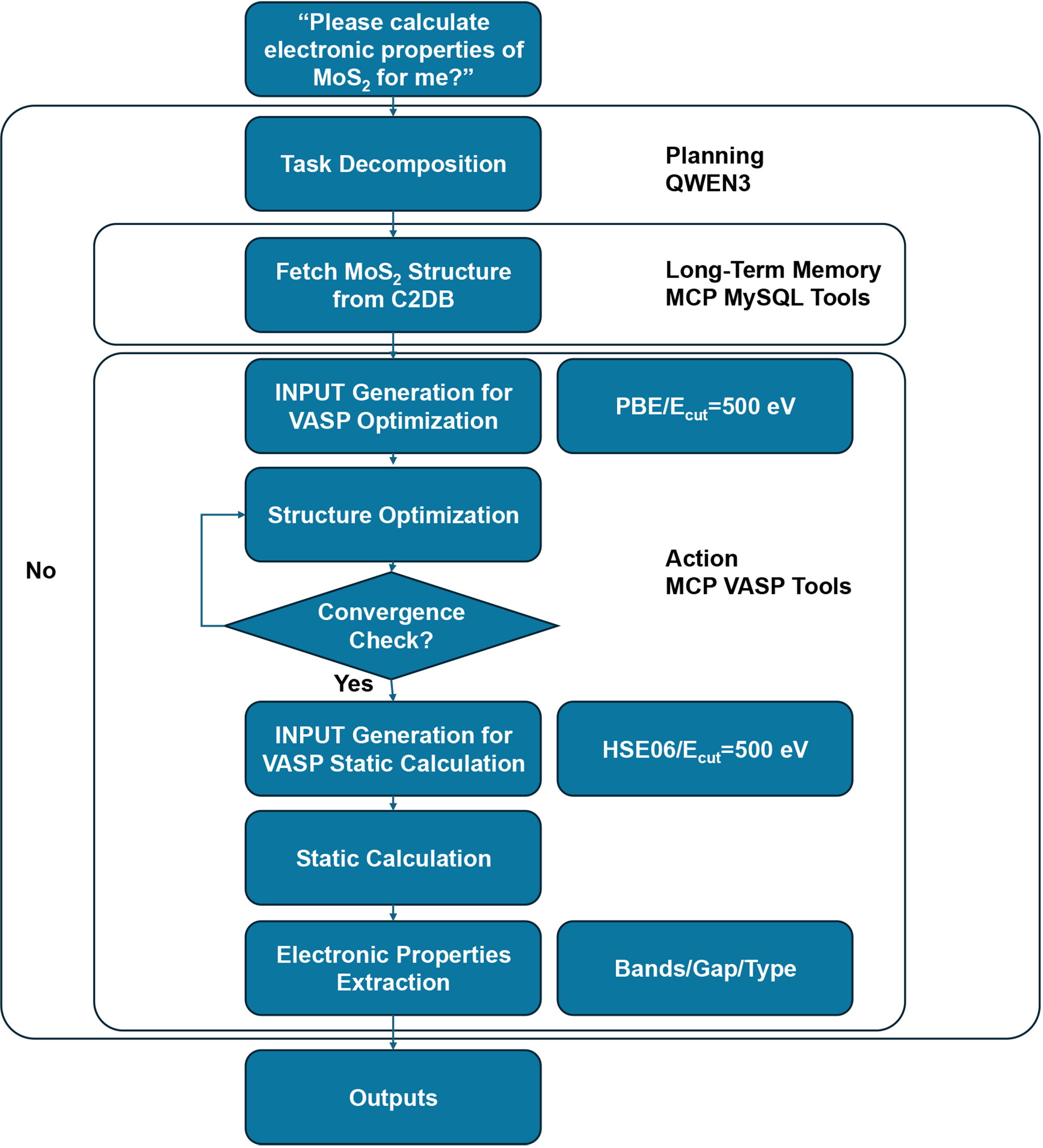

To evaluate the capabilities of the proposed AI-Agent, Matty can be invoked with a simple instruction, for example:

“Please calculate the electronic properties of MoS2 for me.”

Following that, Matty will comprehend this statement and break it down into the following task flow. As illustrated in Figure 2, Matty designed a reasonable workflow for this task. It is apparent that Matty successfully recognized that MoS2 is a periodic system, and selected VASP as the appropriate simulation tool accordingly. Matty retrieved the crystal structure from the C2DB database and initiated a geometry optimization using the PBE exchange-correlation functional[69] with a plane-wave cutoff of 500 eV. It then proceeds to a static electronic structure calculation, where the functional is upgraded to HSE06 (Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof screened hybrid functional)[70] to improve the accuracy of band gap prediction, a common and validated practice for 2D semiconductors.

Figure 2. A workflow for MoS2 electronic properties designed by Agent. C2DB: Computational 2D Materials Database; MCP: Model Context Protocol; MySQL: My Structured Query Language; VASP: Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package; HSE06: Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof screened hybrid functional; QWEN3: Qwen3-235B-A22B-FP8 model.

Once all computations are complete, Matty extracts key electronic properties such as the band structure, band gap, and its nature (direct or indirect), and compiles the results in a structured JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) format. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, for monolayer MoS2, the Agent predicts a direct band gap of 2.34 eV, which aligns well with experimental data and previous theoretical studies[71,72]. This case demonstrates Matty’s ability to autonomously construct and execute a complete DFT workflow, including structure acquisition, parameter selection, convergence handling, hybrid-functional switching, and result extraction, for periodic materials systems. The results not only validate the reliability of Matty’s decision-making but also underscore its potential to automate routine yet technically demanding simulations in materials science. In practice, the agent will also dynamically adjust its feedback based on computational conditions. For instance, when convergence fails, VASP’s calculation parameters will be optimized according to actual conditions.

Generative Agent-guided screening of electrolyte molecules

To further demonstrate the versatility of our Agent, we implemented a fully autonomous pipeline for the inverse design and evaluation of molecules. While molecular systems account for only a subset of the broader materials design landscape, including electrolyte additive[73,74], energetic materials[75,76], organic light-emitting diode (OLED) emitters[77,78], and deep eutectic solvents[79,80], the design of functional molecules remains pivotal in these domains. Importantly, the strategies developed for small molecules are readily extensible to polymeric materials and formulation optimization, further broadening their relevance. As the demand for high-performance batteries with increased voltage windows, enhanced cycle life, and superior safety continues to grow, the performance requirements for electrolytes - and in particular, electrolyte additives - have become increasingly stringent[81-85]. Rational design of such molecules often hinges on theoretical evaluation of key electronic and physicochemical descriptors, including highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels (indicative of oxidative/reductive stability), chemical hardness, and dipole moment[68,73]. These parameters offer a robust direction for assessing redox reactivity, solubility, and functional performance[86].

While traditional database-driven screening approaches rely on rule-based filtering of existing chemical libraries such as PubChem, they are inherently constrained by the finite scope of known compounds[45]. To overcome this limitation, our Agent can design a workflow incorporating generative models, capable of autonomously exploring unexplored regions of chemical space beyond pre-existing databases. When we ask Matty:

“Please design an electrolyte additive molecule with a molecular weight around 100, HOMO around -6.5 eV, and LUMO around 0.3 eV”,

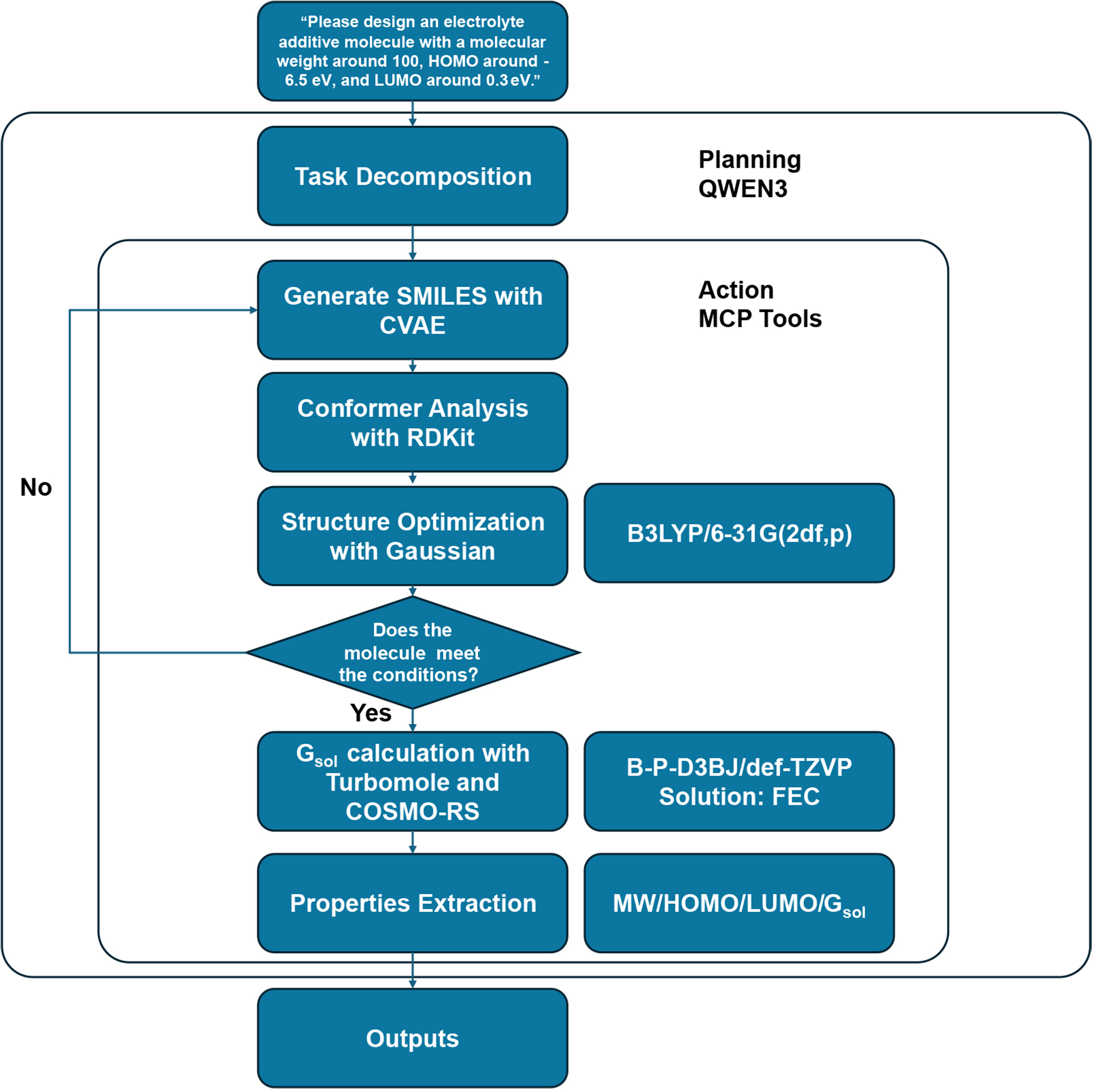

the task was reasonably interpreted and decomposed into several sub-tasks by Matty. It then autonomously constructed a modular simulation pipeline and executed each computational step, as illustrated in Figure 3. The resulting workflow demonstrates a higher level of complexity than that in Task 1 due to the involvement of a broader suite of computational tools, including the CVAE generative model, RDKit for conformer analysis, Gaussian for quantum chemical optimization, and Turbomole combined with COSMO-RS for solvation energy calculations. Notably, Matty correctly identified the problem as a molecular design task and selected a CVAE as the appropriate generative model based on user-specified constraints such as molecular weight (MW), HOMO, and LUMO energy levels. The CVAE model was trained using data from the QM9 dataset and an in-house database, enabling the generation of chemically valid candidate molecules represented as Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings. Each candidate molecule underwent 3D conformer generation using RDKit, followed by geometry optimization at the B3LYP/6-31G (2df, p)[87,88] level of theory using Gaussian. Molecules that satisfied the target electronic criteria were then subjected to solubility evaluation. The Agent selected Turbomole with the COSMO-RS solvation model to compute solvation free energy (Gsol) in a battery-relevant solvent environment [ethylene carbonate (EC)/dimethyl carbonate (DMC) = 1:1.5 molar ratio], using the B-P-D3BJ/def-TZVP level of theory[89-91]. Finally, Matty compiled all relevant properties, including MW, HOMO, LUMO, and Gsol, into structured JSON-format outputs. These newly evaluated structure-property pairs were subsequently reintegrated into the in-house database to iteratively refine the CVAE model. This feedback-driven loop not only improved the quality of candidate generation but also enhanced Matty’s generalizability over time, establishing a scalable and adaptive framework for data-efficient molecular discovery.

Figure 3. A workflow for electrolyte additive design created by Agent. SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System; HOMO: highest occupied molecular orbital; LUMO: lowest unoccupied molecular orbital; CVAE: Conditional Variational Autoencoder; RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics Software Toolkit; Gsol: solvation free energy; COSMO-RS: Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents; FEC: fluoroethylene carbonate; MW: molecular weight; QWEN3: Qwen3-235B-A22B-FP8 model; MCP: Model Context Protocol.

To assess the reliability of our AI-Agent in the workflow, we performed a series of internal validation tests across multiple task categories. For each task, the Agent was prompted with natural language instructions and tasked with constructing and executing the corresponding workflow. In our trials, the Agent achieved a high success rate, with all tested cases executing without observable errors. This high level of robustness is attributed to the MCP tool design with clearly defined functions and application scenarios, structured tool metadata, and the strong reasoning capabilities of the underlying LLM. As a representative demonstration, we conducted three conditional molecular generation tasks, each defined by distinct electronic and structural constraints. These case studies underscore Matty’s ability to flexibly translate user-defined objectives into coherent, multi-step workflows, showcasing both technical reliability and domain adaptability. Matty designs the molecules to satisfy the following performance specifications: high solubility in EC/DMC (1:1.5 mole ratio), a MW of approximately 100 Da, HOMO energy above -6.0 eV, and LUMO energy below 0.0 eV. For demonstration purposes, Matty is configured to perform only a single screening iteration. Two more design cases are further considered, with details provided in the Supporting Information (SI). A set of SMILES with the properties were outputs, and the results were summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

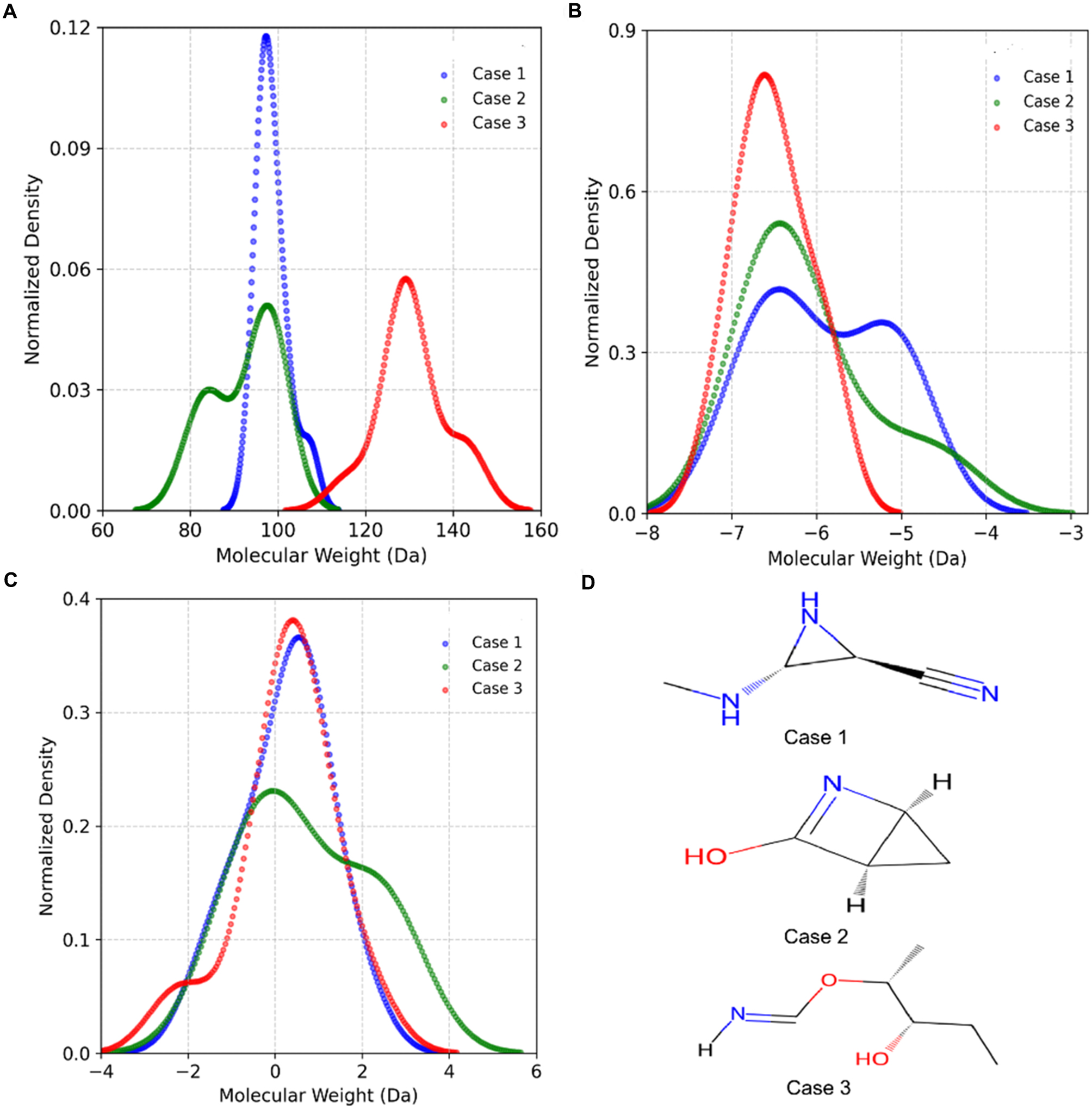

In Case 1, Matty generated 28 molecules, 17 of which matched entries in the QM9 dataset, while 11 were novel structures not previously recorded. Case 2 produced 25 molecules, including 17 known electrolyte-related species and 8 new candidates. Similarly, in Case 3, Matty proposed 28 molecules, of which 18 were present in QM9 and 10 were newly generated. As shown in Figure 4A-C and Supplementary Table 2, although the generated molecules do not exactly match the specified targets, their property distributions exhibit distinct shifts across the three design scenarios, demonstrating Matty’s ability to conditionally modulate generation behavior based on task-specific inputs. Representative molecules from each case, selected for proximity to the mean values of the target properties, are visualized in Figure 4D.

Figure 4. (A-C) Normalized density distributions of molecular weight, HOMO energy, and LUMO energy for Matty-generated molecules in Case 1, Case 2, and Case 3, demonstrating distinct property distributions tailored to each design objective; (D) Representative molecular structures selected for proximity to the mean property values of each case. HOMO: Highest occupied molecular orbital; LUMO: lowest unoccupied molecular orbital.

Furthermore, solubility-related metrics such as Gsol of the new candidates were computed, as reported in Supplementary Table 3. Importantly, Matty not only completed the inverse design task based on electronic and structural criteria but also recognized the electrolyte-relevant context and extended the workflow by selecting an appropriate solvent model for solubility evaluation. This highlights its capacity to autonomously incorporate domain-specific knowledge into property validation. However, due to the limited availability of curated datasets for electrolyte additives, especially those related to stability, compatibility with electrode interfaces, and degradation mechanisms, the current model has inherent limitations in capturing all chemically viable candidates. With the continuous expansion of domain-specific knowledge bases - not only in terms of high-quality data, but also expert-derived rules and computational modeling strategies - Matty is expected to evolve into an increasingly powerful system, capable of more accurate reasoning and broader applicability across complex materials design challenges.

CONCLUSIONS

This work demonstrates an early yet promising step toward integrating LLM-driven reasoning with domain-specific simulation tools for autonomous materials design. While the proposed AI-Agent system successfully interprets user intent and executes complex computational workflows, it currently remains a prototype with limitations in scalability, flexibility, and generalizability across diverse material classes. Transitioning from conceptual validation to practical utility requires resolving some critical challenges such as seamless interoperability between heterogeneous tools, improved robustness and transferability of generative models, and transparent decision-making mechanisms that support interpretability and trust. The convergence of LLM-based planning, generative modeling, and high-throughput simulations offers an opportunity to reshape the landscape of materials research. Rather than merely automating tasks, looking ahead, future AI-Agents may evolve into collaborative research partners, capable of proposing hypotheses, reasoning across multi-scale datasets, and autonomously navigating vast chemical and structural design spaces. Achieving this vision will depend on sustained progress in foundational AI models, standardized simulation interfaces, and curated domain knowledge bases encompassing both experimental and theoretical insights. With the advancement and maturation of these technologies, we anticipate that adaptive, self-improving agents will play an increasingly pivotal role in accelerating materials discovery, enhancing reproducibility, and enabling more intelligent, goal-driven materials design workflows.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: Yang, M.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, X.

Performed data acquisition and provided administrative, technical, and material support: Xu, D. H.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, G.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Code for this demo is available at https://github.com/Yang-col-lab/Request-driven-workflow-automation-demo.

Financial support and sponsorship

Yang, M. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22173064). Wang, X. acknowledges the Advanced Materials National Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2025ZD0618403).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, X.; et al. Artificial intelligence: a powerful paradigm for scientific research. Innovation 2021, 2, 100179.

2. Maqsood, A.; Chen, C.; Jacobsson, T. J. The future of material scientists in an age of artificial intelligence. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2401401.

3. Wang W, Li J, Liu W, Liu Z. Integrated computational materials engineering for advanced materials: a brief review. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 158, 42-8.

4. Panchal, J. H.; Kalidindi, S. R.; Mcdowell, D. L. Key computational modeling issues in Integrated Computational Materials Engineering. Comput. Aided. Des. 2013, 45, 4-25.

5. Ong, S. P. Accelerating materials science with high-throughput computations and machine learning. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 161, 143-50.

6. Ren, F.; Ward, L.; Williams, T.; et al. Accelerated discovery of metallic glasses through iteration of machine learning and high-throughput experiments. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaaq1566.

7. Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Machine learning assisted identification of homobilayer sliding ferroelectrics with large out-of-plane polarization and low sliding energy barriers. Phys. Rev. B. 2025, 111.

8. van der Giessen, E.; Schultz, P. A.; Bertin, N.; et al. Roadmap on multiscale materials modeling. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 28, 043001.

9. Botifoll, M.; Pinto-Huguet, I.; Arbiol, J. Machine learning in electron microscopy for advanced nanocharacterization: current developments, available tools and future outlook. Nanoscale. Horiz. 2022, 7, 1427-77.

10. Paier, J.; Marsman, M.; Hummer, K.; Kresse, G.; Gerber, I. C.; Angyán, J. G. Screened hybrid density functionals applied to solids. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 154709.

11. Aykol, M.; Kim, S.; Hegde, V. I.; et al. High-throughput computational design of cathode coatings for Li-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13779.

12. Jang, S. H.; Tateyama, Y.; Jalem, R. High‐throughput data‐driven prediction of stable high‐performance Na‐ion sulfide solid electrolytes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2206036.

13. Benayad, A.; Diddens, D.; Heuer, A.; et al. High‐throughput experimentation and computational freeway lanes for accelerated battery electrolyte and interface development research. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2102678.

14. Boyd, P. G.; Lee, Y.; Smit, B. Computational development of the nanoporous materials genome. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, BFnatrevmats201737.

15. Lafferentz, L.; Eberhardt, V.; Dri, C.; et al. Controlling on-surface polymerization by hierarchical and substrate-directed growth. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 215-20.

16. Xu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Huo, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M. Advances in data‐assisted high‐throughput computations for material design. Mater. Genome. Eng. Adv. 2023, 1, e11.

17. Shu, Y.; Miao, N.; Li, R.; et al. Machine learning-enabled optoelectronic material discovery: a comprehensive review. J. Mater. Inf. 2025, 5, 36.

18. Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Shen, L. Data-driven discovery of high-performance heterobilayer transition metal dichalcogenide-based sliding ferroelectrics. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2025, 17, 7164-73.

19. Garrity, K. F.; Bennett, J. W.; Rabe, K. M.; Vanderbilt, D. Pseudopotentials for high-throughput DFT calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2014, 81, 446-52.

20. Jain, A.; Hautier, G.; Moore, C. J.; et al. A high-throughput infrastructure for density functional theory calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2011, 50, 2295-310.

21. Calderon, C. E.; Plata, J. J.; Toher, C.; et al. The AFLOW standard for high-throughput materials science calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2015, 108, 233-8.

22. Xu, Y.; Elcoro, L.; Song, Z. D.; et al. High-throughput calculations of magnetic topological materials. Nature 2020, 586, 702-7.

23. Naveed, H.; Khan, A. U.; Qiu, S.; et al. A comprehensive overview of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.06435. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.06435 (accessed 23 January 2026).

24. Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; et al. A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM. Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1-45.

25. Tian, S.; Jiang, X.; Wang, W.; et al. Steel design based on a large language model. Acta. Mater. 2025, 285, 120663.

26. Jiang, X.; Wang, W.; Tian, S.; Wang, H.; Lookman, T.; Su, Y. Applications of natural language processing and large language models in materials discovery. npj. Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 1554.

27. Hewitt, C.; Bishop, P.; Steiger, R. A universal modular ACTOR formalism for artificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the 3rd international joint conference on Artificial intelligence, Stanford, CA, USA, August 20-23, 1973; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1973; Vol. 3, pp 235-45. https://www.eighty-twenty.org/files/Hewitt,%20Bishop,%20Steiger%20-%201973%20-%20A%20universal%20modular%20ACTOR%20formalism%20for%20artificial%20intelligence.pdf (accessed 2026-01-23).

28. Zhao, W. X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.18223 (accessed 23 January 2026).

29. Sapkota, R.; Roumeliotis, K. I.; Karkee, M. AI Agents vs. Agentic AI: a conceptual taxonomy, applications and challenges. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.10468. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.10468 (accessed 23 January 2026).

30. Barua, S. Exploring autonomous agents through the lens of large language models: a review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.04442. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.04442 (accessed 23 January 2026).

31. Wu, J.; Or, C. K. Position paper: towards open complex Human-AI Agents Collaboration System for problem-solving and knowledge management. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.00018. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.00018 (accessed 23 January 2026).

32. Fu, J.; Liu, X.; Cai, W.; Fu, H.; Shao, X. SpeLL: an agent for natural language-driven intelligent spectral modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 7844-50.

33. Huang, H.; Shi, X.; Lei, H.; Hu, F.; Cai, Y. ProtChat: an AI multi-agent for automated protein analysis leveraging GPT-4 and protein language model. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 62-70.

34. Ansari, M.; Watchorn, J.; Brown, C. E.; Brown, J. S. dziner: rational inverse design of materials with AI Agents. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.03963. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.03963 (accessed 23 January 2026).

35. Hu, B.; Liu, S.; Ye, B.; Hao, Y.; Wen, T. A multi-agent framework for materials laws discovery. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.16416. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.16416 (accessed 23 January 2026).

36. Ansari, M.; Moosavi, S. M. Agent-based learning of materials datasets from the scientific literature. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 2607-17.

37. Bai, X.; Wang, H.; Xie, L.; et al. An integrated AI system for multi-objective screening of MOF materials. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 133939.

38. Ramos, M. C.; Collison, C. J.; White, A. D. A review of large language models and autonomous agents in chemistry. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 2514-72.

39. Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; et al. ReAct: synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, May 1-5, 2023; OpenReview.net: Alameda, CA, USA, 2023. https://par.nsf.gov/biblio/10451467 (accessed 2026-01-23).

40. Hou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H. Model context protocol (MCP): landscape, security threats, and future research directions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.23278. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.23278 (accessed 23 January 2026).

41. Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; et al. Qwen3 technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09388. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.09388 (accessed 23 January 2026).

42. Bento, A. P.; Hersey, A.; Félix, E.; et al. An open source chemical structure curation pipeline using RDKit. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 51.

43. Ong, S. P.; Richards, W. D.; Jain, A.; et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2013, 68, 314-9.

44. Jain, A.; Ong, S. P.; Hautier, G.; et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL. Mater. 2013, 1, 011002.

45. Kim, S.; Thiessen, P. A.; Bolton, E. E.; et al. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2016, 44, D1202-13.

46. Ramakrishnan, R.; Dral, P. O.; Rupp, M.; von, Lilienfeld. O. A. Quantum chemistry structures and properties of 134 kilo molecules. Sci. Data. 2014, 1, 140022.

47. Gjerding, M. N.; Taghizadeh, A.; Rasmussen, A.; et al. Recent progress of the Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB). 2D. Mater. 2021, 8, 044002.

48. Greenspan, J.; Bulger, B. MySQL/PHP database applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2001. ISBN: 9780130893874. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/558011 (accessed 2026-01-23).

49. Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016. https://gaussian.com/gaussian16/ (accessed 2026-01-23).

50. Furche, F.; Ahlrichs, R.; Hättig, C.; Klopper, W.; Sierka, M.; Weigend, F. Turbomole. WIREs. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2014, 4, 91-100.

51. Bannwarth, C.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S. GFN2-xTB - an accurate and broadly parametrized self-consistent tight-binding quantum chemical method with multipole electrostatics and density-dependent dispersion contributions. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2019, 15, 1652-71.

52. Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter. 1996, 54, 11169-86.

53. Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1-19.

54. Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580-92.

56. Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825-30. https://www.jmlr.org/papers/volume12/pedregosa11a/pedregosa11a.pdf?source=post_page (accessed 2026-01-23).

57. Balandat, M.; Karrer, B.; Jiang, D. R.; et al. BoTorch: a framework for efficient Monte Carlo Bayesian optimization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020), Virtual Format, December 6-12, 2020; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Vol. 33, pp 21524-38. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/hash/f5b1b89d98b7286673128a5fb112cb9a-Abstract.html (accessed 2026-01-23).

58. Sohn, K.; Lee, H.; Yan, X. Learning structured output representation using deep conditional generative models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28 (NIPS 2015), Montreal, Canada, December 7-12, 2015; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2015. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2015/hash/8d55a249e6baa5c06772297520da2051-Abstract.html (accessed 2026-01-23).

59. Kipf, T. N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1609.02907 (accessed 23 January 2026).

60. Velickovic, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.10903. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1710.10903 (accessed 23 January 2026).

61. Gasteiger, J.; Groß, J.; Günnemann, S. Directional message passing for molecular graphs. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.03123. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2003.03123 (accessed 23 January 2026).

62. Xie, T.; Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 145301.

63. Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; et al. PyTorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, Canada, December 8-14, 2019; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/hash/bdbca288fee7f92f2bfa9f7012727740-Abstract.html (accessed 2026-01-23).

64. Fey, M.; Lenssen, J. E. Fast graph representation learning with PyTorch Geometric. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.02428. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1903.02428 (accessed 23 January 2026).

65. Topsakal, O.; Akinci, T. C. Creating large language model applications utilizing LangChain: a primer on developing LLM Apps fast. ICAENS 2023, 1, 1050-6.

66. Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; et al. TensorFlow: large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous systems. 2015. https://www.tensorflow.org/ (accessed 2026-01-23).

67. Choi, W.; Choudhary, N.; Han, G. H.; Park, J.; Akinwande, D.; Lee, Y. H. Recent development of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides and their applications. Mater. Today. 2017, 20, 116-30.

68. Zhang, S. S. A review on electrolyte additives for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2006, 162, 1379-94.

69. Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865-8.

70. Heyd, J.; Scuseria, G. E.; Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 8207-15.

71. Ermolaev, G. A.; Stebunov, Y. V.; Vyshnevyy, A. A.; et al. Broadband optical properties of monolayer and bulk MoS2. npj. 2D. Mater. Appl. 2020, 4, 155.

72. Winther, K. T.; Thygesen, K. S. Band structure engineering in van der Waals heterostructures via dielectric screening: the GΔW method. 2D. Mater. 2017, 4, 025059.

73. Haregewoin, A. M.; Wotango, A. S.; Hwang, B. Electrolyte additives for lithium ion battery electrodes: progress and perspectives. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 1955-88.

74. Gu, Y.; Wu, X.; Gopalakrishna, T. Y.; Phan, H.; Wu, J. Graphene-like molecules with four zigzag edges. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 6541-5.

75. Fried, L. E.; Manaa, M. R.; Pagoria, P. F.; Simpson, R. L. Design and synthesis of energetic materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2001, 31, 291-321.

76. Göbel, M.; Klapötke, T. M. Development and testing of energetic materials: the concept of high densities based on the trinitroethyl functionality. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 347-65.

77. Hong, G.; Gan, X.; Leonhardt, C.; et al. A brief history of OLEDs-Emitter development and industry milestones. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2005630.

78. Santos PL, Stachelek P, Takeda Y, Pander P. Recent advances in highly-efficient near infrared OLED emitters. Mater. Chem. Front. 2024, 8, 1731-66.

79. Smith, E. L.; Abbott, A. P.; Ryder, K. S. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060-82.

80. Hansen, B. B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; et al. Deep eutectic solvents: a review of fundamentals and applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232-85.

81. Flamme, B.; Rodriguez, Garcia. G.; Weil, M.; et al. Guidelines to design organic electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries: environmental impact, physicochemical and electrochemical properties. Green. Chem. 2017, 19, 1828-49.

82. Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Lv, Y.; et al. Identification of potential electrolyte additives via density functional theory analysis. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202300098.

83. Fan, X.; Wang, C. High-voltage liquid electrolytes for Li batteries: progress and perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 10486-566.

84. Gao, P.; Andersen, A.; Sepulveda, J.; et al. SOMAS: a platform for data-driven material discovery in redox flow battery development. Sci. Data. 2022, 9, 740.

85. Spotte-Smith, E. W. C.; Blau, S. M.; Xie, X.; et al. Quantum chemical calculations of lithium-ion battery electrolyte and interphase species. Sci. Data. 2021, 8, 203.

86. Cheng, L.; Assary, R. S.; Qu, X.; et al. Accelerating electrolyte discovery for energy storage with high-throughput screening. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 283-91.

87. Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648-52.

88. Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J. S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650-4.

89. Perdew, J. P. Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter. 1986, 33, 8822-4.

90. Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456-65.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].