Ultralow thermal conductivity via weak interactions in PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure for thermoelectric design

Abstract

In this study, we systematically investigate the thermal and electronic transport properties of a two-dimensional (2D) PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure by combining first-principles calculations, Boltzmann transport theory, and machine learning methods. The heterostructure exhibits a unique honeycomb-like corrugated and asymmetric configuration, which significantly enhances phonon scattering. Moreover, the relatively weak interatomic interactions in PbSe/PbTe lead to the formation of antibonding states, resulting in strong anharmonicity and ultimately yielding ultralow lattice thermal conductivity

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Driven by the record-high global temperatures and the increased industry consumption, the global energy demand in 2024 rose by 2.2 %, according to Global Energy Review 2025 by the International Energy Agency[1]. This growth rate is considerably higher than the average annual increase of 1.3 % between 2013 and 2023. The emerging energy crisis has gained global attention and has intensified scientific pursuit of advanced materials capable of providing efficient and sustainable energy solutions. As the energy crisis intensifies, thermoelectric materials are receiving more attention than ever before due to their ability to convert waste heat into clean energy through the direct and reversible conversion between heat and electricity via the Seebeck and Peltier effects[2–6]. The conversion efficiency is typically evaluated using the dimensionless figure of merit (ZT)[7]:

where S is the Seebeck coefficient, σ is the electrical conductivity, T is the absolute temperature, and

In the field of thermoelectrics, two-dimensional (2D) materials exhibit unique advantages owing to quantum confinement effects and tunable interfacial phonon scattering. Their atomic-scale thickness can significantly suppress phonon transport while maintaining high carrier mobility[21,22]. Lee et al. demonstrated that in conventional bulk materials, electrical conductivity (σ) and electronic thermal conductivity (

Recently, the monolayers RbTe and RbSe with the same honeycomb-like wrinkled structures have been theoretically reported to show high ZT values of 1.55 and 1.33 at 900 K, respectively, based on the three-phonon scattering model[27,28]. In spite of the high thermoelectric performance of the individual monolayers, the structure and the thermoelectric properties of a heterostructure system consisting of monolayers RbTe and RbSe remain to be explored. Herein, we employ a combination of first-principles calculations, the Boltzmann transport equation (BTE), and machine learning algorithms to systematically investigate the crystal structure, electronic transport, phonon behavior, and thermoelectric performance of the wrinkled RbSe/RbTe monolayer heterostructure. Through detailed analysis of interatomic bonding characteristics and anharmonic vibrational effects, we reveal the underlying physical mechanisms responsible for the intrinsically low

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) were performed by using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) code[29,30], in which the projector augmented wave (PAW) approach was used for the accurate treatment of core valence interactions[31,32]. The exchange-correlation interactions within the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure were treated using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional in the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)[33], A plane-wave kinetic energy cutoff of 500 eV was employed, and the Brillouin zone was sampled with a 12 × 12 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid[34]. To eliminate spurious interactions between periodic images, a vacuum region of 20 Å was inserted along the out-of-plane direction. Convergence thresholds were set to 10-8 eV for total energy and 0.001 eV/Å for atomic forces. To accurately assess the electronic band structure, the Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof (HSE06) hybrid functional was used[35]. Thermal stability of the 2D PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure was verified through ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations as our recent studies[36,37]. Using a 4 × 4 × 1 supercell, the monolayer heterostructure was simulated at 300 and 700 K for a total duration of 10 ps with a time step of 1 fs, employing the canonical (NVT) ensemble. Additionally, crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) analysis was carried out using the Local Orbital Basis Suite Towards Electronic-Structure Reconstruction (LOBSTER) code[38]. The vdW interactions were corrected by Grimme's scheme[39,40].

Machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) family offers high precision in modeling atomic interactions and is particularly compatible with the moment tensor potential (MTP) approach. The definition of the MTP can be found in the section "DISCUSSION OF MTP POTENTIAL AND ACCURACY" of the Supplementary Materials.

To construct the MLIP, a MTP framework was adopted, where model fitting was carried out by minimizing a custom-designed loss function[41,42]:

This objective function aims to align MTP predictions with reference data obtained from AIMD, including total energies, atomic forces, and stress tensors. Specifically,

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Crystal structure, chemical bonding, and stability

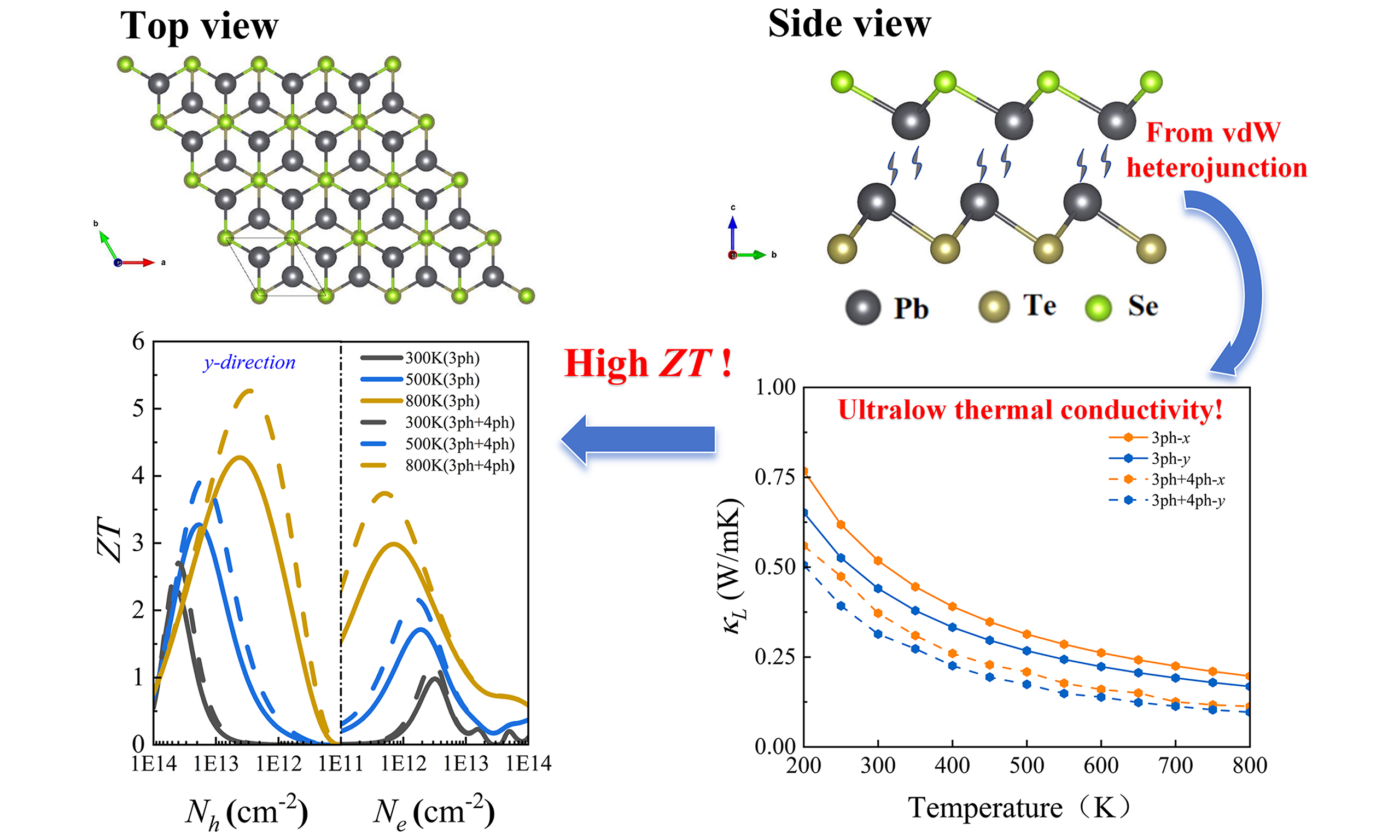

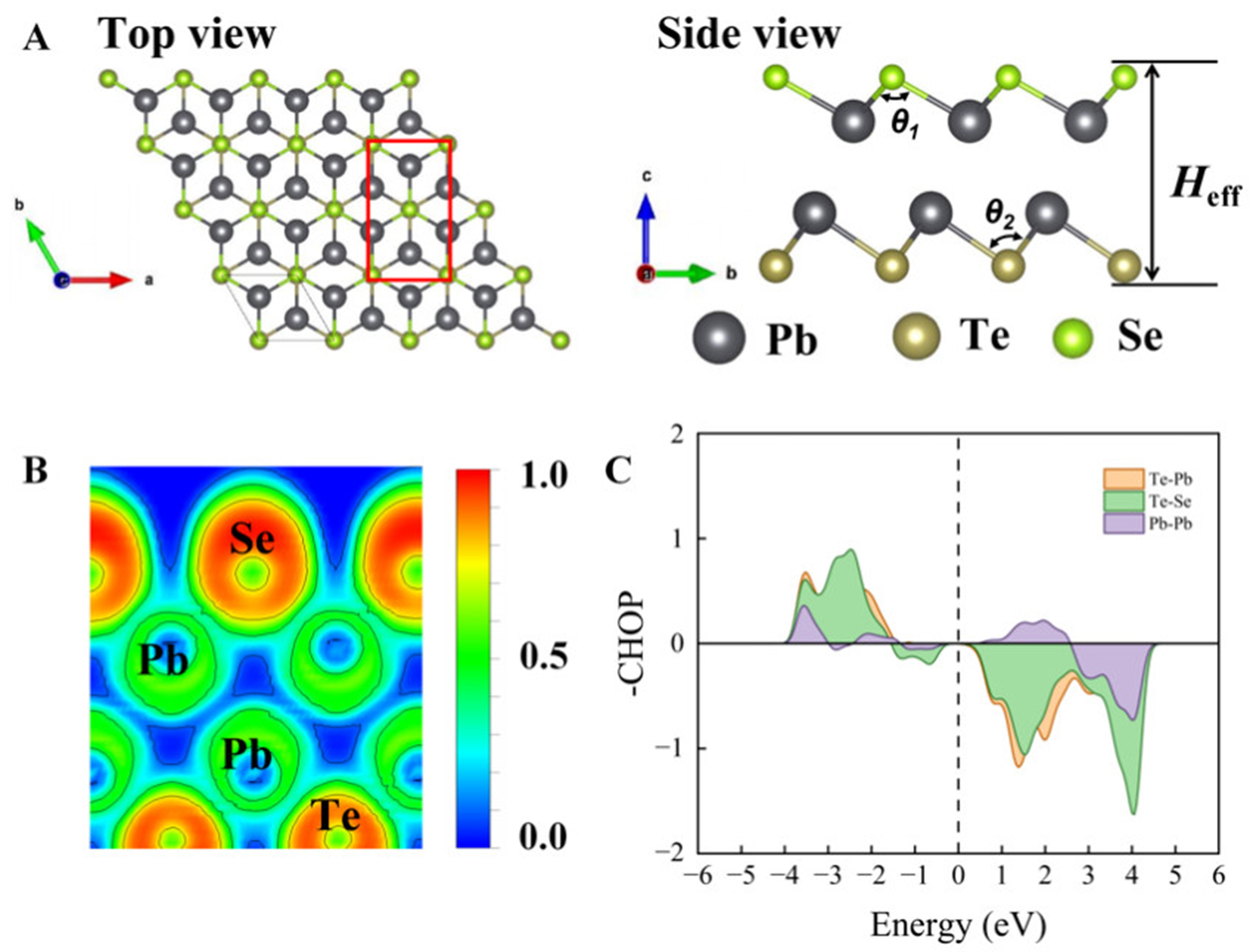

As illustrated in Figure 1A, the monolayer PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure exhibits a pronounced wrinkled morphology. The crystal structure consists of two Pb atomic layers sandwiched by alternately arranged Se and Te atoms, and belongs to the

Figure 1. Supercell structure of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure: (A) Top view and side view; (B) ELF; (C) -COHP analysis. ELF: Electron localization function.

Lattice constants, lattice angles, bond lengths (d), bond angles (θ), and effective thickness (

| Material | γ ( | |||||||

| PbSe/PbTe | 4.300 | 90 | 120 | 2.854 | 3.006 | 97.74 | 91.32 | 6.038 |

Bonding characteristics play a crucial role in determining the performance of thermoelectric materials. To gain deeper insight into the bonding behavior in the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure and its impact on

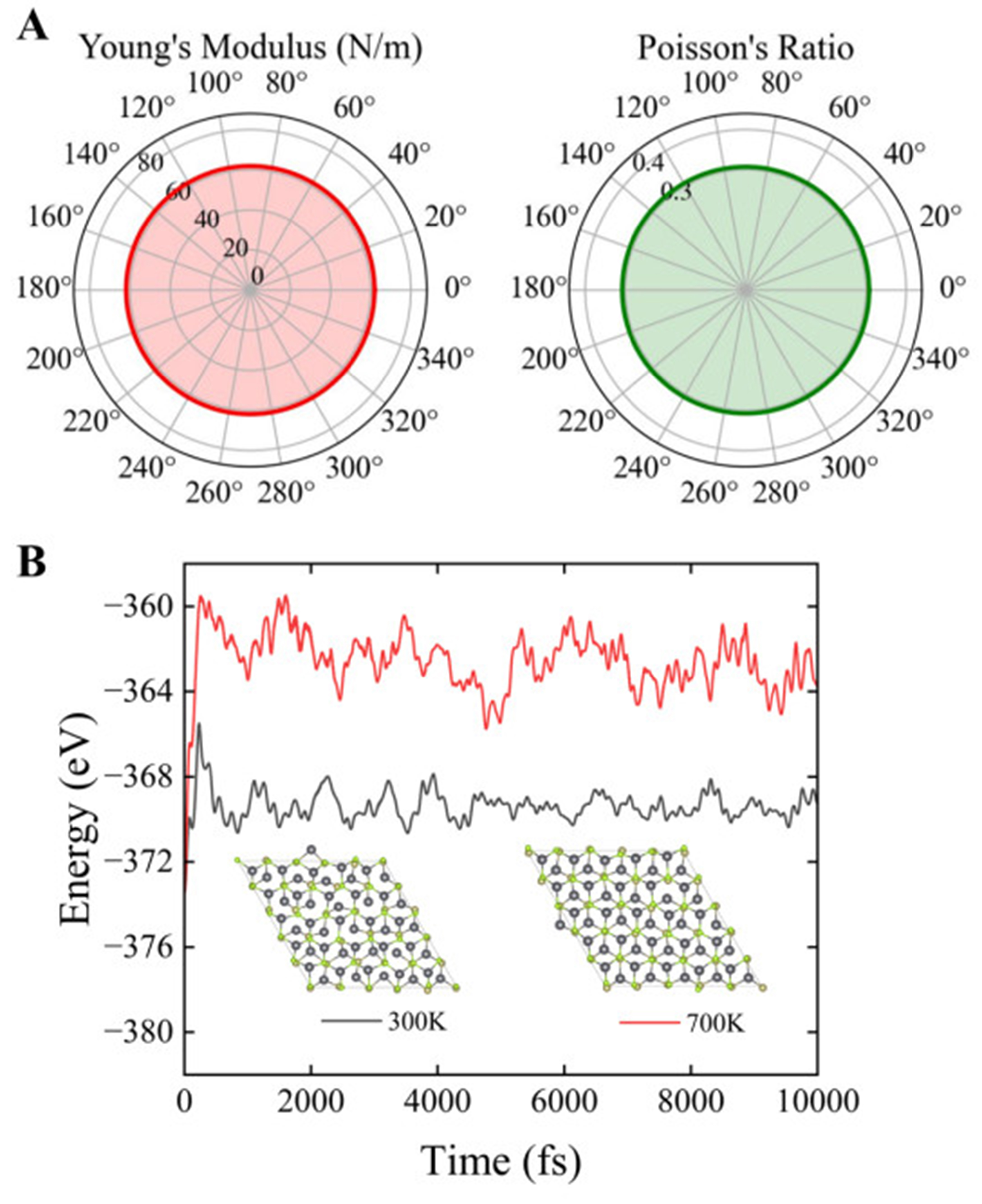

Good stability is essential for thermoelectric materials. Firstly, the elastic constants matrix of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure was calculated, as shown in Table 2. The PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure satisfies the Born-Huang criteria for mechanical stability, namely:

Elastic stiffness matrix (C), 2D Young's modulus (

| Material | ν | Θ (K) | |||||

| PbSe/PbTe | 9.208 | 2.849 | 9.202 | 3.174 | 61.94 | 0.307 | 43.9 |

where

Figure 2. (A) Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure;(B) AIMD results of the 4 × 4 × 1 supercell of PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure at 300 and 700 K. AIMD: Ab initio molecular dynamics.

To further assess the thermal stability of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure, AIMD simulations were performed in the NVT ensemble using a 4 × 4 × 1 supercell at 300 and 700 K, with a total simulation time of 10 ps and a time step of 1 fs. The results are presented in Figure 2B, indicating that the total energy remained relatively constant throughout the simulations, and the supercell crystal structure exhibited no distortion or disintegration. These findings confirm the structural stability of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure at both room temperature (300 K) and elevated temperature (700 K).

Phonon transport properties

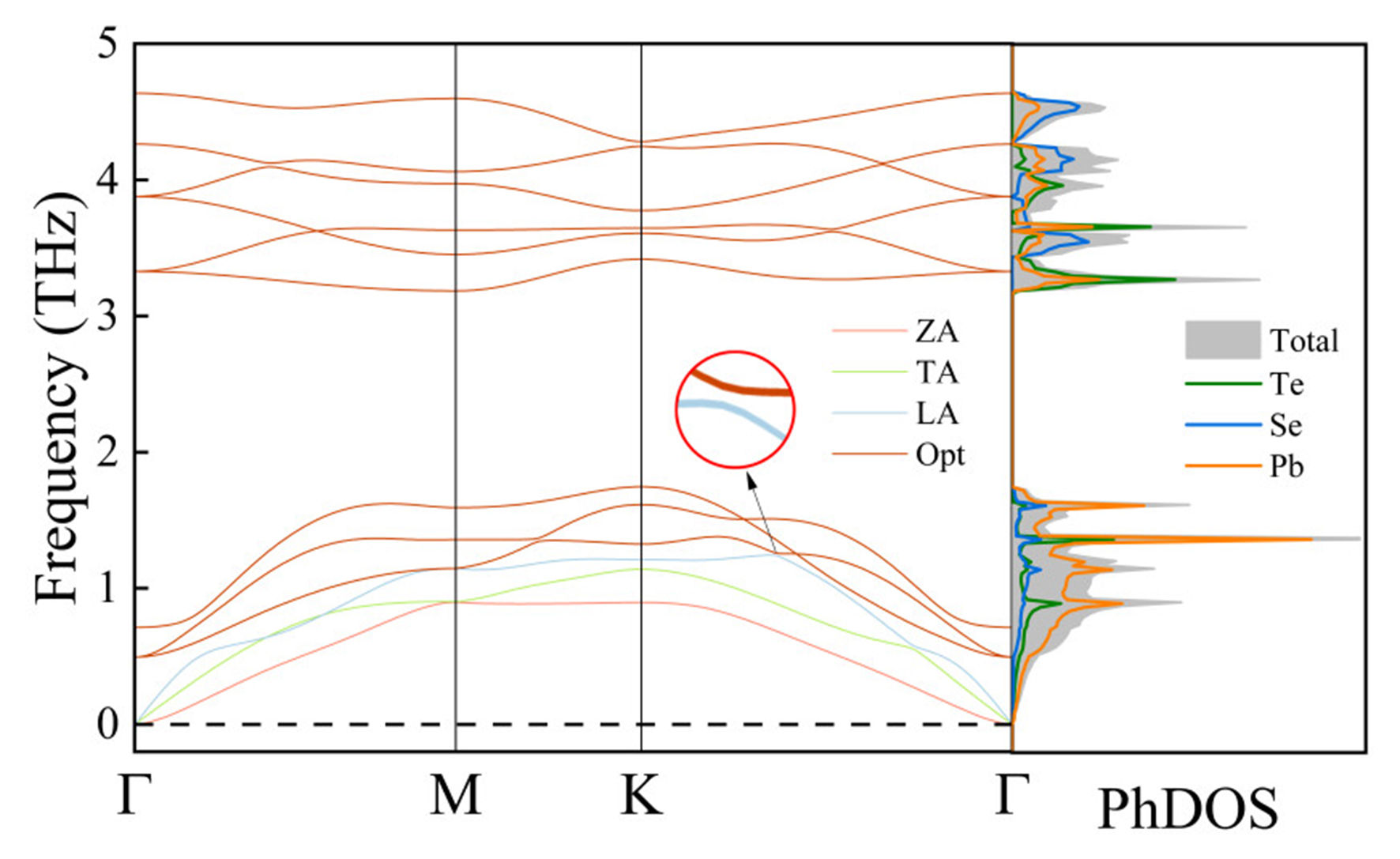

Based on the machine learning MTP method, we systematically evaluated the phonon dispersion characteristics of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure. This method achieves a favorable balance between computational accuracy and efficiency, and its effectiveness in thermoelectric materials research has been extensively validated by numerous studies. Moreover, our previous work has confirmed its applicability to similar systems[50,62]. Furthermore, as shown in Supplementary Figure 4, the phonon dispersion curves of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure unit cell calculated using the finite displacement method and the MTP potential exhibit excellent agreement, which fully validates the reliability of the MTP approach employed in predicting the phonon transport properties of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure. Figure 3 shows the phonon dispersion relations and corresponding phonon density of states (PhDOS) of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure along the high-symmetry path Γ-M-K-Γ. The system comprises three acoustic phonon branches, corresponding to the out-of-plane (ZA), transverse (TA), and longitudinal (LA) vibrational modes, while the remaining nine branches represent optical modes. No imaginary frequencies appear throughout the Brillouin zone, indicating dynamical stability of the structure. Further analysis of the phonon spectrum reveals that the highest phonon frequency of the material is 4.72 THz, significantly lower than typical thermoelectric materials such as ZnSe (~8 THz) and MoS2 (~14 THz)[63,64]. This low-frequency characteristic typically indicates a reduced

Figure 3. Phonon dispersion curves and PhDOS of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure. "Opt" represents the optical phonon modes. PhDOS: Phonon density of states.

In the phonon dispersion relations, we clearly observe an avoided crossing between the longitudinal acoustic (LA) branch and the low-energy optical branch along the

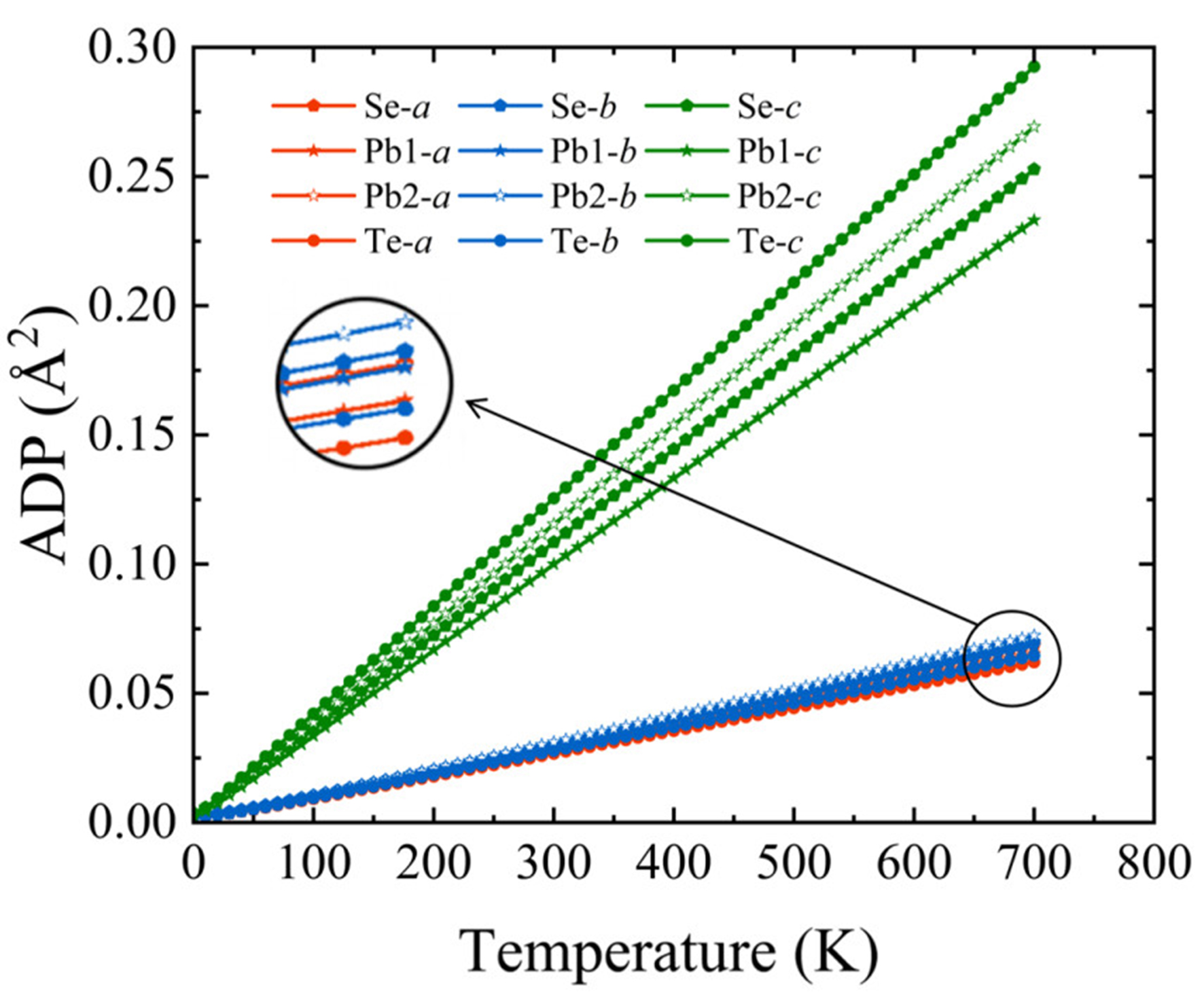

Intense atomic thermal vibrations are often closely related to strong anharmonicity in the crystal structure. To further quantify the degree of anharmonicity and characterize atomic vibrations in the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure, we computed the anisotropic displacement parameters (ADPs) of atoms along different crystallographic axes. The ADP not only reflects the intensity of atomic vibrations but also indirectly indicates the strength of atomic bonds. When the chemical bonds between atoms are stronger, the amplitude of atomic vibrations is smaller, leading to a lower ADP value. Conversely, when the bonds are weaker, the atomic vibrations are larger, resulting in a higher ADP value. The detailed calculation method of ADPs is provided in the Supplementary Materials. As shown in Figure 4. It is clearly observed that the ADPs along the c-axis are significantly larger than those along the a- and b-axes, indicating more intense thermal vibrations perpendicular to the plane. Specifically, Pb atoms in the top and bottom layers exhibit relatively smaller ADP than Te atoms, which is mainly attributed to their larger atomic mass[66], whereas the higher ADP values of Te atoms can be ascribed to the weaker bonding strength with surrounding atoms. This finding is consistent with the previous conclusions from ELF and –COHP analyses, indicating weak chemical bonding interactions between Pb and Te, which allows freer atomic thermal motion and thereby enhances the structural anharmonicity.

Figure 4. ADP of different atoms along various directions in the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure. ADP: Anisotropic displacement parameter.

Overall, the pronounced atomic vibration amplitudes along the c-axis, the local bonding strength heterogeneity, and the large ADP values in the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure collectively indicate strong anharmonicity of the system, which effectively enhances phonon scattering and consequently significantly reduces the

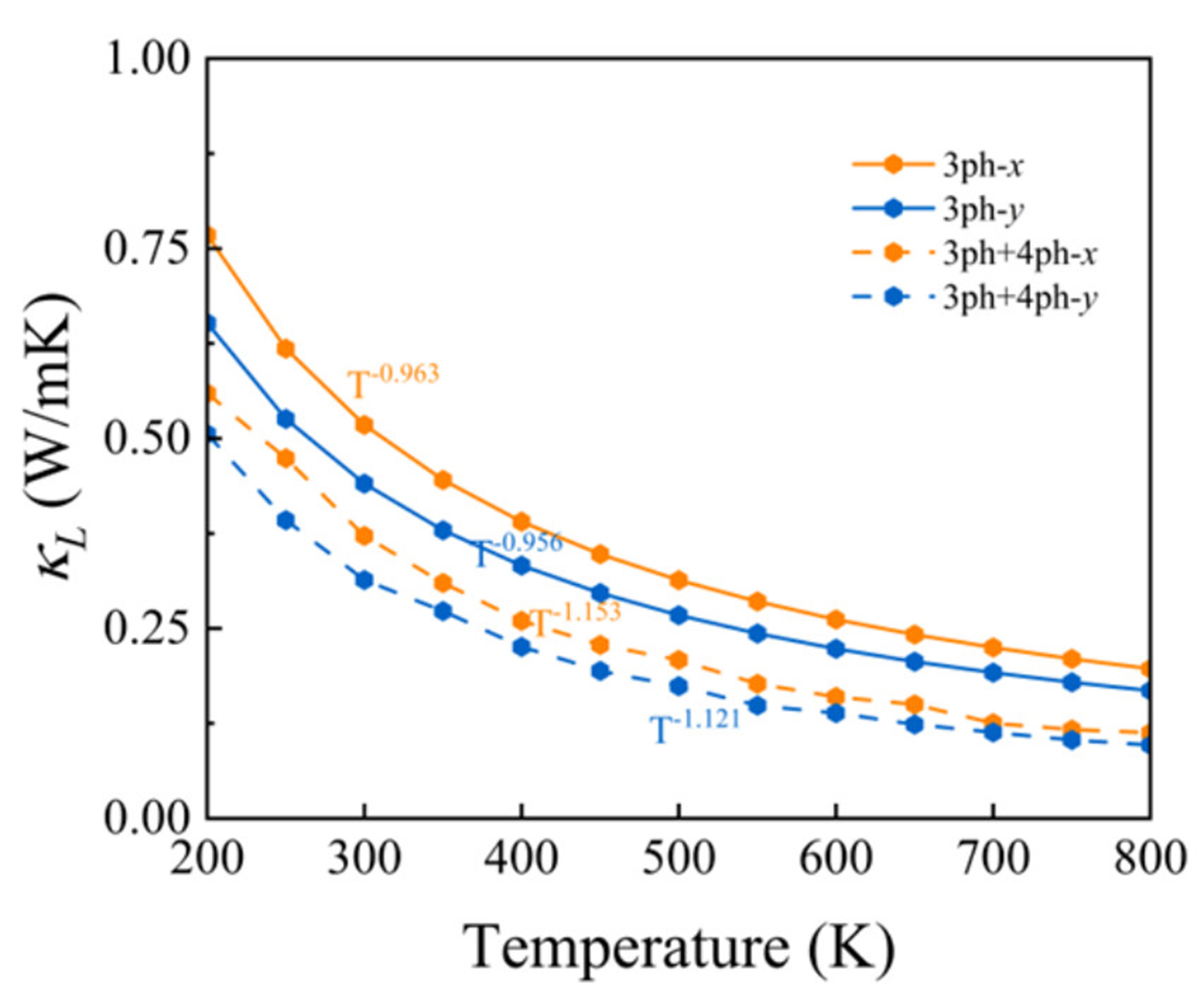

From the previous analyses, it is evident that the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure exhibits considerable anharmonicity, and we therefore predict that the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure will possess a low

Here,

Figure 5. Temperature dependence of

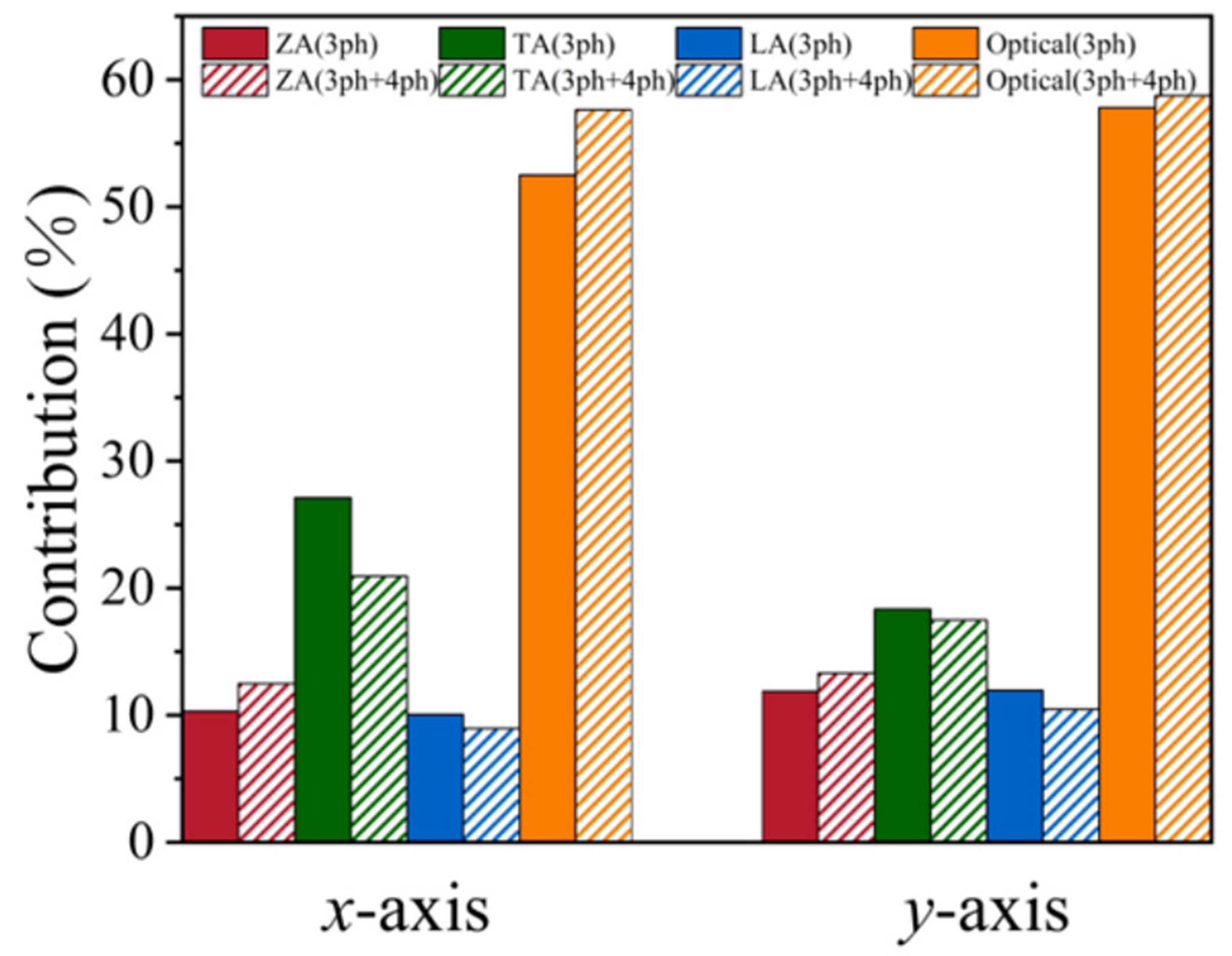

To further elucidate the phonon transport mechanisms in the monolayer PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure, we performed a detailed analysis of the contributions of different acoustic modes (ZA, TA, LA) and optical modes to the total

Figure 6. Contributions of different phonon modes (ZA, TA, LA, and Optical) to

To verify the validity of the phonon quasiparticle picture, we plotted the total phonon scattering rates from 400 to 800 K under the four-phonon scattering model, and included a reference red line corresponding to the breakdown threshold of the quasiparticle picture, defined as

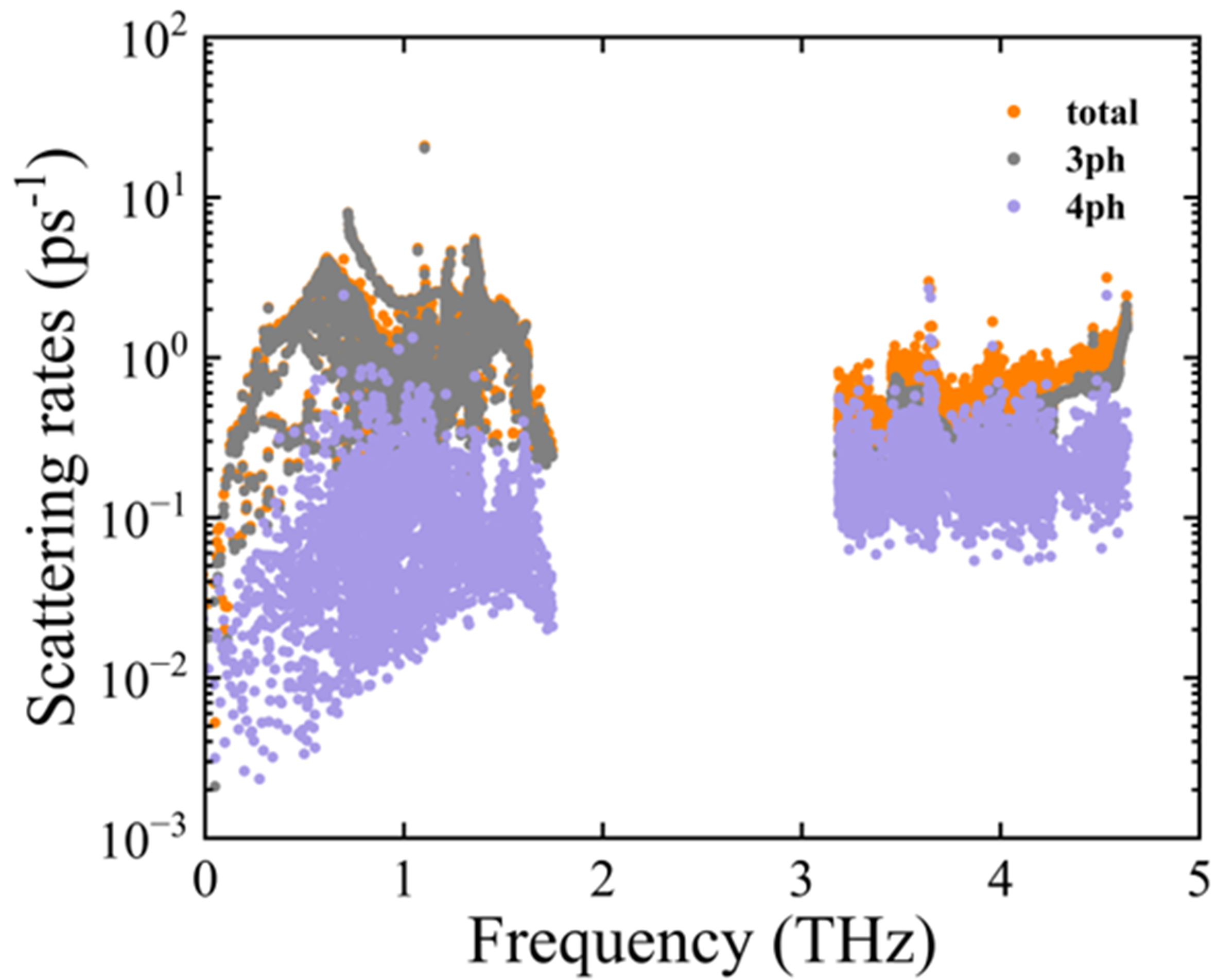

Figure 7. Frequency-dependent three-phonon and four-phonon scattering rates of PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure.

As the frequency increases, both three-phonon and four-phonon scattering rates exhibit a gradually increasing trend, reaching peaks in certain frequency ranges before stabilizing, with two distinct scattering peaks observed near approximately 0.5 and 1.5 THz, respectively. Based on PhDOS analysis, as shown in Figure 3, the scattering peak around 0.5 THz is primarily attributed to the low-frequency vibrational modes of Pb atoms, where strong coupling occurs between the lowest optical branch and acoustic branches, thereby facilitating enhanced phonon-phonon scattering processes. Although the magnitudes of three- and four-phonon scattering rates are comparable, the latter exhibits significant influence across multiple frequency ranges, indicating that four-phonon scattering is also a critical mechanism governing

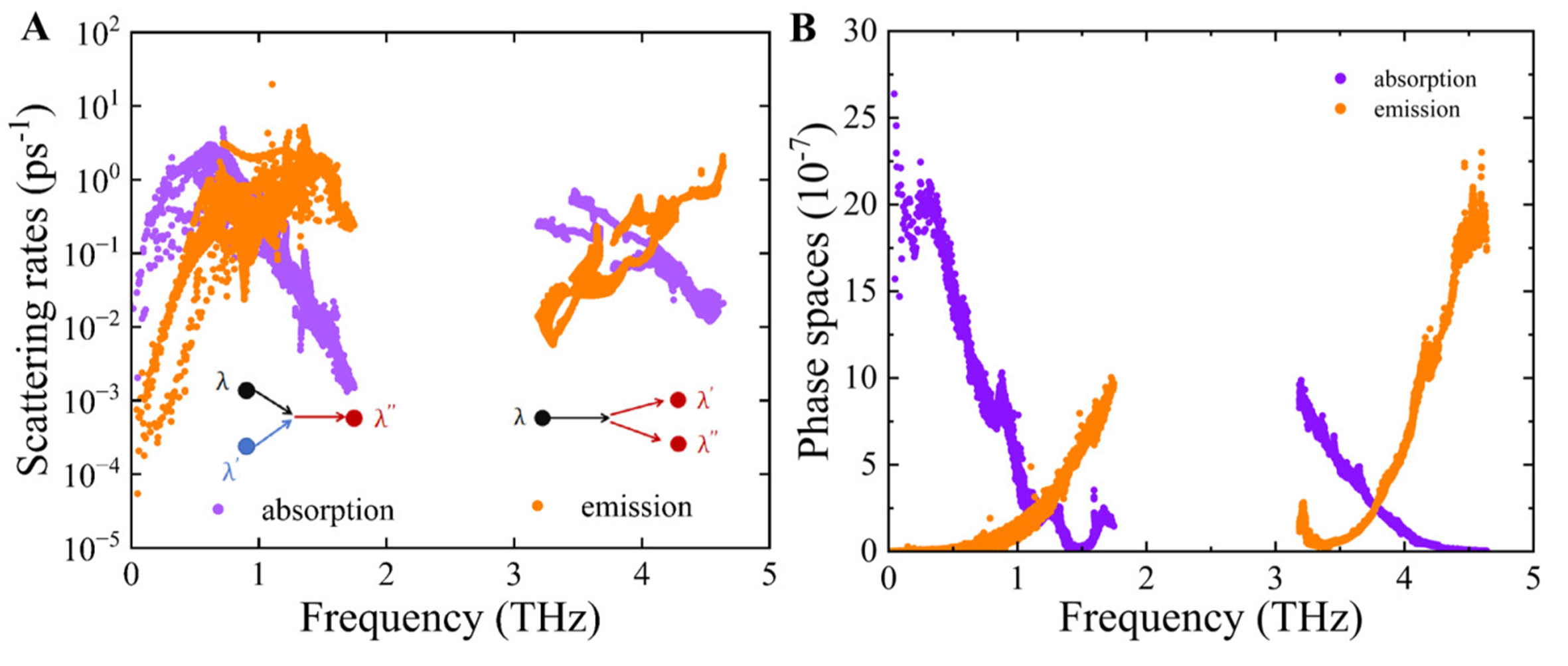

Figure 8. Absorption and emission processes under three-phonon scattering of PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure: (A) scattering rates; (B) phase space as a function of frequency.

To further understand the frequency dependence of these scattering channels, the three-phonon scattering phase space was computed and is presented in Figure 8B, separately for absorption and emission processes. It is evident that in the low-frequency range (0 to 1 THz), the absorption process possesses a broad scattering phase space, while a relatively large emission phase space exists in the high-frequency range (approximately 4 to 4.8 THz). As shown in Figure 3, PhDOS analysis indicates that the low-frequency region is mainly contributed by acoustic modes of Pb atoms, whereas the high-frequency region is dominated by optical vibrations primarily involving Pb and Se atoms. These results suggest that the optical branches involving Pb and Se atoms provide abundant three-phonon scattering channels at high frequencies, which enhances the density of scattering events and plays a critical role in reducing the thermal conductivity.

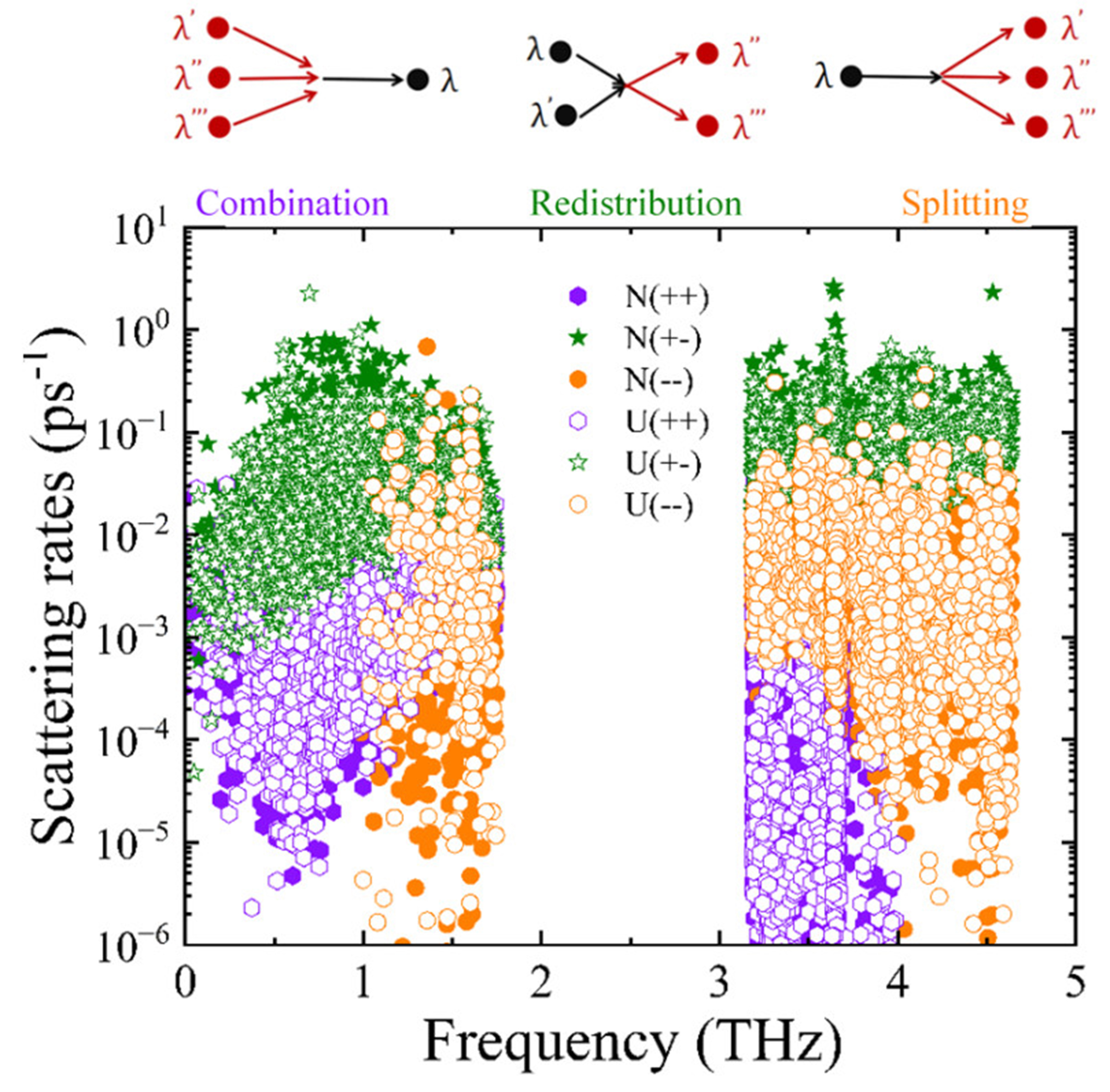

To gain deeper insight into four-phonon scattering mechanisms, we further investigated all possible scattering channels in the monolayer PbSe/PbTe heterostructure. As shown in Figure 9, the four-phonon scattering processes in the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure include both Umklapp and Normal types. These processes can be classified into three main scattering channels: combination (++ process,

Figure 9. Calculated four-phonon scattering rates of PbSe/PbTe heterostructure monolayer as a function of phonon frequency, including three scattering channels: combination (++), redistribution (+-), and splitting (- -). "U" denotes Umklapp processes, while "N" refers to the normal processes.

Moreover, in the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure, the strong four-phonon scattering is intrinsically associated with the presence of an acoustic-optical phonon band gap, as shown in Figure 3. In the vicinity of the pronounced gap between the acoustic and optical branches (1.7 to 3.2 THz), the available phase space for three-phonon scattering processes is significantly reduced. As illustrated in Figure 8A and B, this leads to a notable suppression of both the three-phonon phase space and the corresponding scattering rates. Specifically, absorption-type three-phonon processes are largely prohibited due to the strict energy conservation constraints imposed by the gap. In contrast, four-phonon processes particularly redistribution and splitting channels remain active near the gap region, as demonstrated in Figure 9. These higher-order interactions are less constrained by energy selection rules and are capable of bridging the phonon band gap, thereby introducing additional anharmonic scattering pathways that are forbidden in the three-phonon regime. This mechanism is further supported by Figure 7, which shows that while the contribution of four-phonon processes is generally lower than that of three-phonon processes in the low-frequency region, a noticeable increase in four-phonon scattering occurs near the gap where three-phonon scattering is substantially weakened. This results in a comparable contribution from both scattering mechanisms in the gap region. These findings highlight the dual role of the phonon band gap: it suppresses conventional three-phonon scattering while simultaneously enhancing the importance of four-phonon interactions. Therefore, the increased activity of four-phonon processes plays a critical role in reducing the

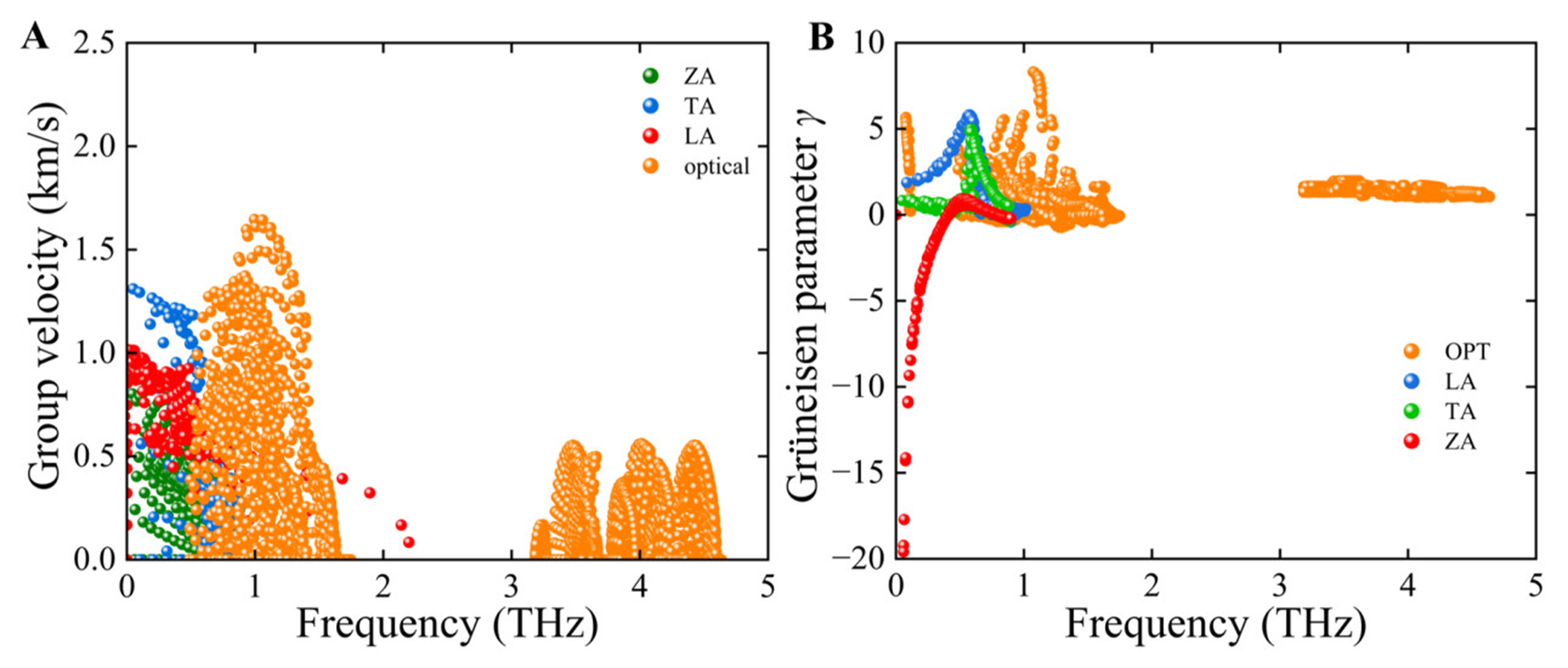

We further calculated the phonon group velocity of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure at 300 K based on the standard group velocity expression[67]:

where

Figure 10. (A) Phonon group velocity (

Here,

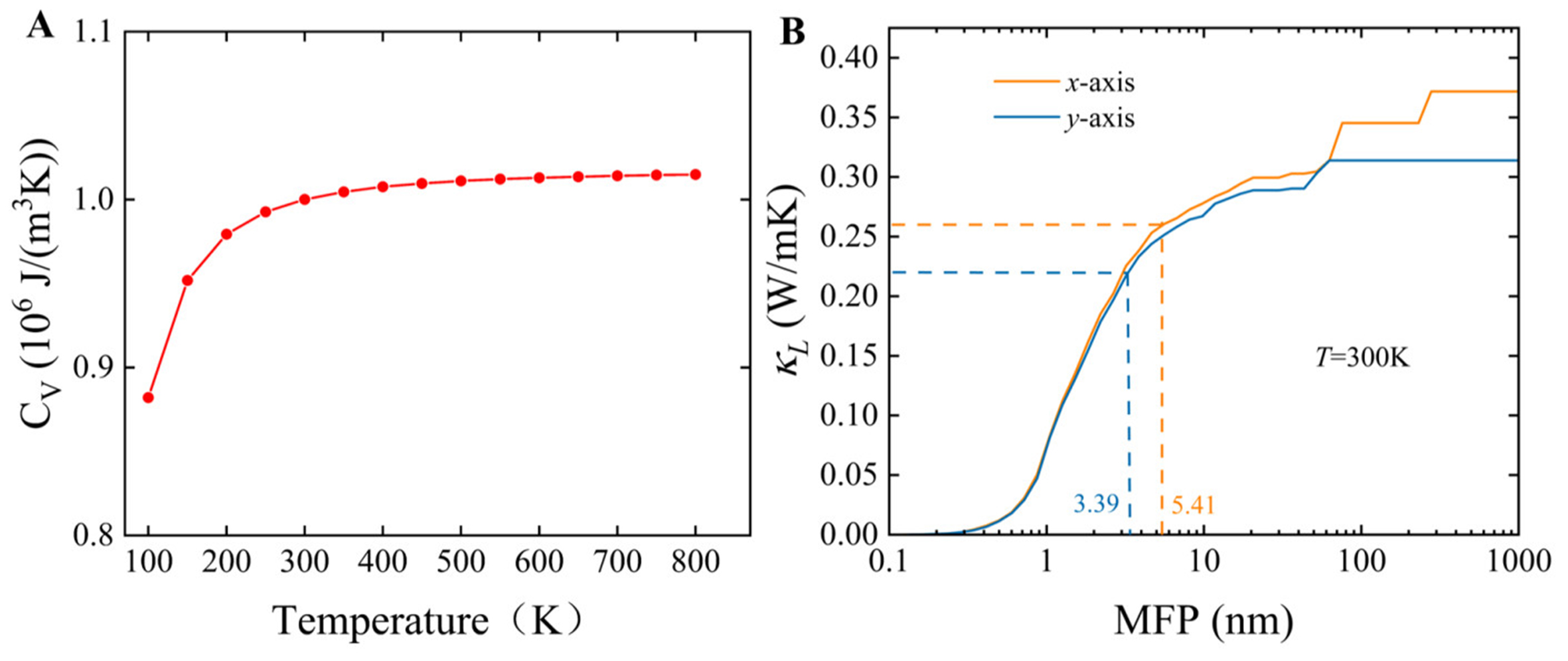

In addition, we evaluated the specific heat capacity

Figure 11. (A) Calculated volumetric heat capacity of PbSe/PbTe heterostructure monolayer as a function of temperature; (B)

As depicted in Figure 11B, the relationship between

Electronic transport properties

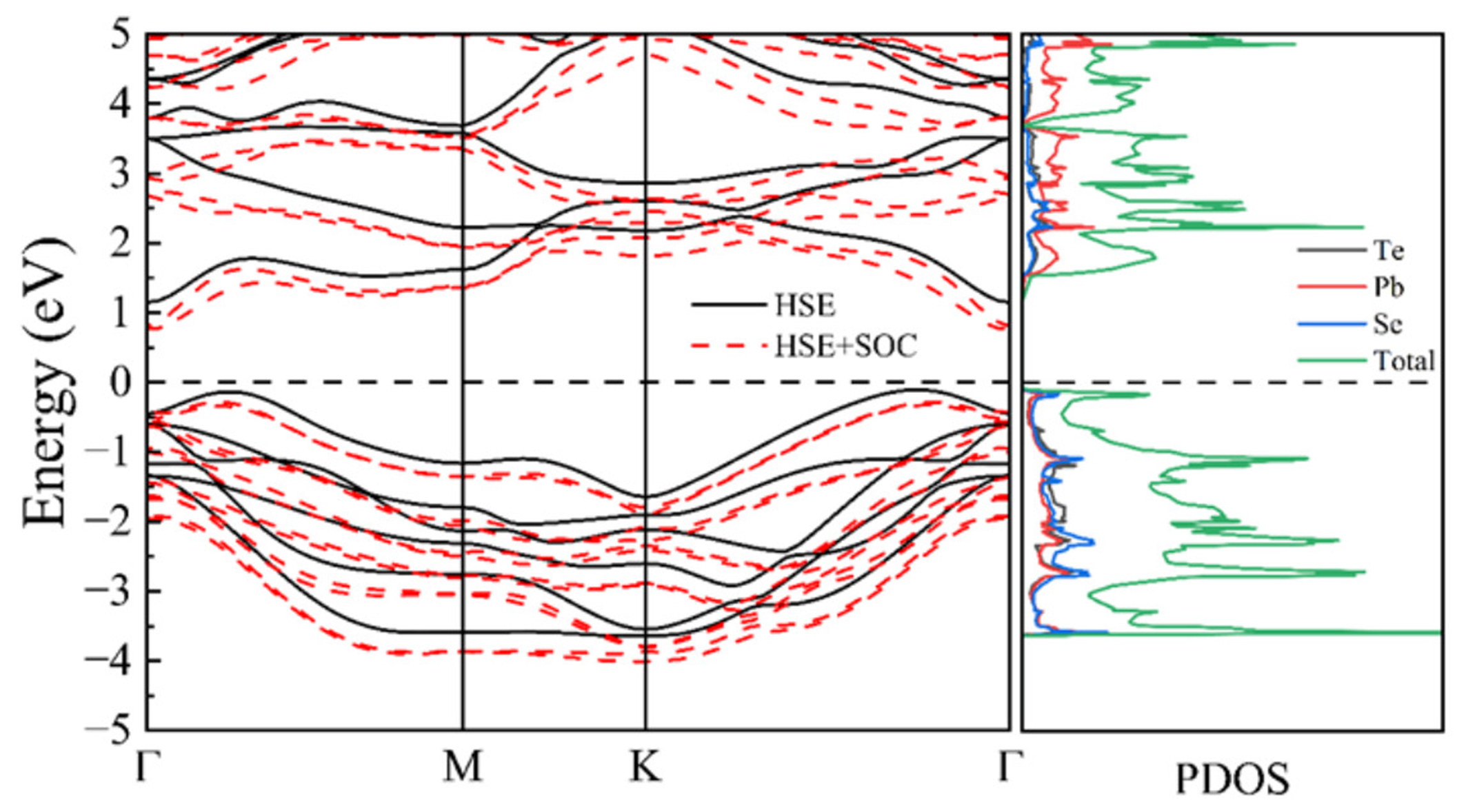

We next analyzed the electronic transport properties of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure. Initially, the electronic band structure was calculated using the PBE functional. As shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 8, the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure exhibits a band gap of 0.77 eV, indicating its semiconducting nature. However, it is well known that the PBE functional tends to significantly underestimate band gaps. To obtain more accurate electronic band characteristics, we further performed calculations using the hybrid HSE06 functional. The resulting band structure and DOS are presented in Figure 12. The PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure exhibits an indirect band gap, with the band gap value increasing to 1.25 eV, as listed in Supplementary Table 1. This increase is primarily attributed to the upward shift of the conduction band upon applying the HSE06 method.

Figure 12. Band structures and PDOS calculated using HSE and HSE + SOC methods. PDOS: Projected density of states; HSE: Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof; SOC: spin-orbit coupling.

Moreover, the electronic states near the valence band maximum (VBM) are relatively flat, resulting in a large effective mass that contributes to a high Seebeck coefficient. In contrast, the sharp and highly dispersive nature of the conduction band minimum (CBM) favors high carrier mobility. These intrinsic band characteristics are beneficial for achieving excellent thermoelectric (TE) performance. The projected density of states (PDOS) analysis shows that the CBM is primarily contributed by Pb atoms, while the VBM originates mainly from Se atoms. Additionally, the sharp increase in the DOS near the Fermi level is indicative of a potentially enhanced Seebeck coefficient.

Given the heavy atomic mass of Pb in the PbSe/PbTe heterostructure monolayer, we also considered the influence of spin-orbit coupling (SOC). Upon including SOC in HSE06 calculations, we observed an overall downward shift in the band structure shown in Figure 12. However, the bandgap remains at approximately 1.05 eV, showing no significant deviation from the value without SOC. Therefore, SOC effects can be reasonably neglected in subsequent calculations.

Based on the analysis of the band structure, we predict that the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure possesses promising electronic transport properties. To quantitatively evaluate this, we calculated the Seebeck coefficient (S) and electrical conductivity (σ) of the PbSe/PbTe heterojunction in the temperature range of 300 to 800 K using the semiclassical BTE as implemented in the BoltzTraP code[48].

In addition, the rigid band approximation (RBA) was employed to simulate the effect of carrier doping on the electronic performance. The RBA assumes that the overall band structure remains unchanged upon doping, while only the position of the Fermi level shifts accordingly to represent different doping concentrations. These electronic transport properties can be expressed as[48]:

Here, μ represents the chemical potential, e is the elementary charge of an electron, and f denotes the Fermi-Dirac distribution function of charge carriers. The function

Here, v represents the electron group velocity. The temperature-dependent relaxation time τ is determined based on the deformation potential theory. Considering the dominant role of acoustic phonon scattering, the 2D carrier mobility

Here,

where ρ is the uniaxial strain applied along the corresponding direction, and S is the cross-sectional area projected along the z-axis. The effective mass

Here, ε denotes the energy of the electronic band,

Calculated effective masses (

| Material | Direction | Carrier Type | E (eV) | τ ( | |||

| PbSe/PbTe | x | n-type | 34.37 | 6.620 | 0.122 | 1,126.8 | 7.81 |

| x | p-type | 34.37 | 4.134 | 0.627 | 118.87 | 4.23 | |

| y | n-type | 37.87 | 6.616 | 0.122 | 1,243.0 | 8.61 | |

| y | p-type | 37.87 | 3.312 | 0.531 | 240.95 | 7.27 |

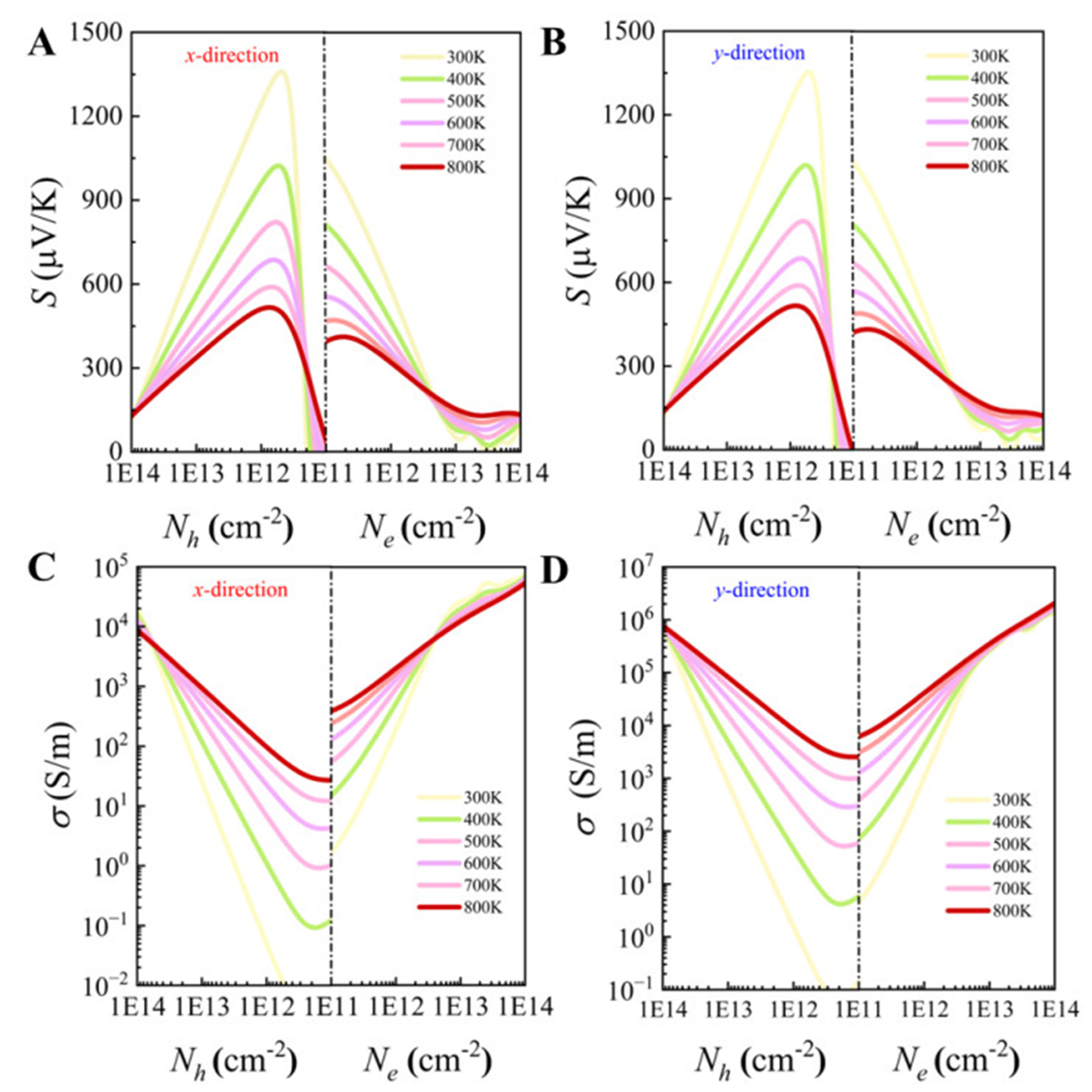

The Seebeck coefficients (S) of p-type and n-type PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructures are shown in Figure 13A and B. Clearly, S increases with rising temperature, and the S values for n-type doping are significantly lower than those for p-type doping, which is consistent with our previous analysis of the effective masses at the VBM and CBM. At 300 K, the maximum S values for p-type (n-type) doping along the x and y directions reach

Figure 13. Seebeck coefficient (S) vs. carrier concentration of PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure along x and y directions in the temperature range 300 to 800 K: (A) p-type; (B) n-type. Electrical conductivity (σ) vs. carrier concentration: (C) p-type; (D) n-type.

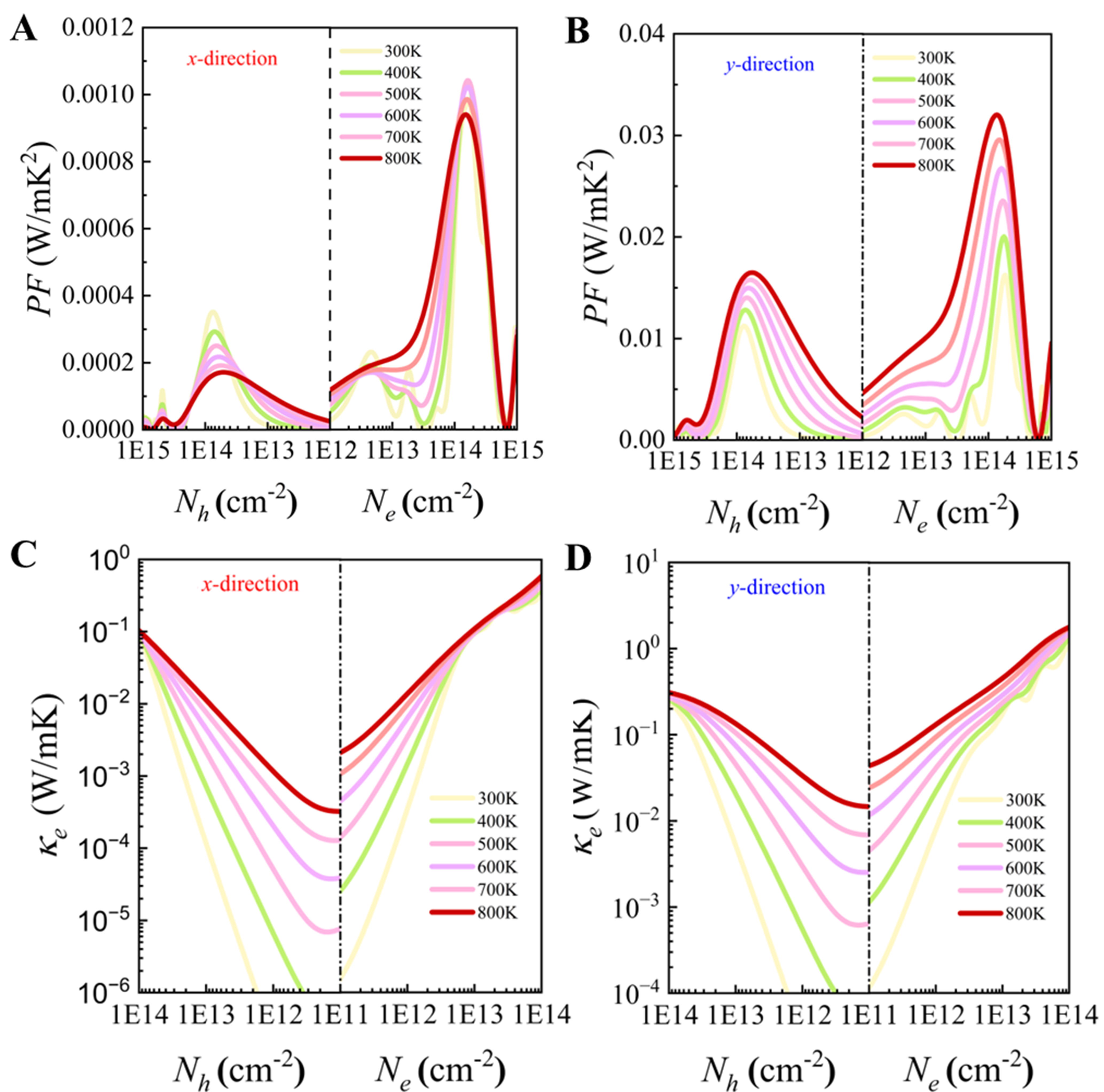

Next, the electronic transport performance of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure is evaluated using the power factor. As shown in Figure 14A and B, the values of power factors under n-type doping are significantly higher than those under p-type doping. Moreover, the power factors along the y-direction are evidently greater than those along the x-direction. Specifically, under n-type doping, the power factor in the y-direction reaches a maximum of 0.035 W · m−1 · K−2, which is much higher than that of common 2D thermoelectric materials such as ZrSn2N4 (3.13 mW · m−1 · K−2)[82] and PbTe (~5.861 mW · m−1 · K−2)[83], indicating the superior electronic transport properties of the PbSe/PbTe heterostructure monolayer along the y-direction. The observed asymmetry in power factor enhancement between n-type and p-type doping can be attributed to their distinct electronic structures, as previously discussed. The VBM exhibits a relatively flat dispersion, resulting in a larger effective mass for holes, which is favorable for achieving a high Seebeck coefficient. In contrast, the CBM is more dispersive and sharper, leading to a smaller effective mass for electrons and, consequently, higher carrier mobility. This fundamental difference in band curvature underlies the disparity in power factor between n-type and p-type doping. Moreover, the transport parameters listed in Table 3 quantitatively support this interpretation. The effective mass of n-type carriers is only 0.122 m0 in both directions, significantly lower than that of p-type carriers, which ranges from 0.531 m0 to 0.627 m0. As a result, the mobility of n-type carriers reaches 1,126.8 and 1,243.0 cm2 · V−1 · s−1 along the x and y directions, respectively - substantially exceeding the mobilities of p-type carriers (118.87 and 240.95 cm2 · V−1 · s−1). Additionally, the relaxation time (τ) of n-type carriers is generally longer, further enhancing their transport properties. Although the deformation potential constant (E) of n-type carriers is slightly higher, the advantages in effective mass and relaxation time compensate for this, yielding superior overall mobility. In summary, the lower effective mass, enhanced mobility, and longer relaxation time of n-type carriers collectively account for the more pronounced power factor enhancement observed under n-type doping.

Figure 14. Power factor vs. carrier concentration of PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure along x and y directions in the temperature range 300 to 800 K: (A) p-type; (B) n-type. Electronic thermal conductivity (

The electronic thermal conductivity (

where L is the Lorenz number, σ is the electrical conductivity, and T is the temperature. As an important component of the total thermal conductivity,

Thermoelectric figure of merit

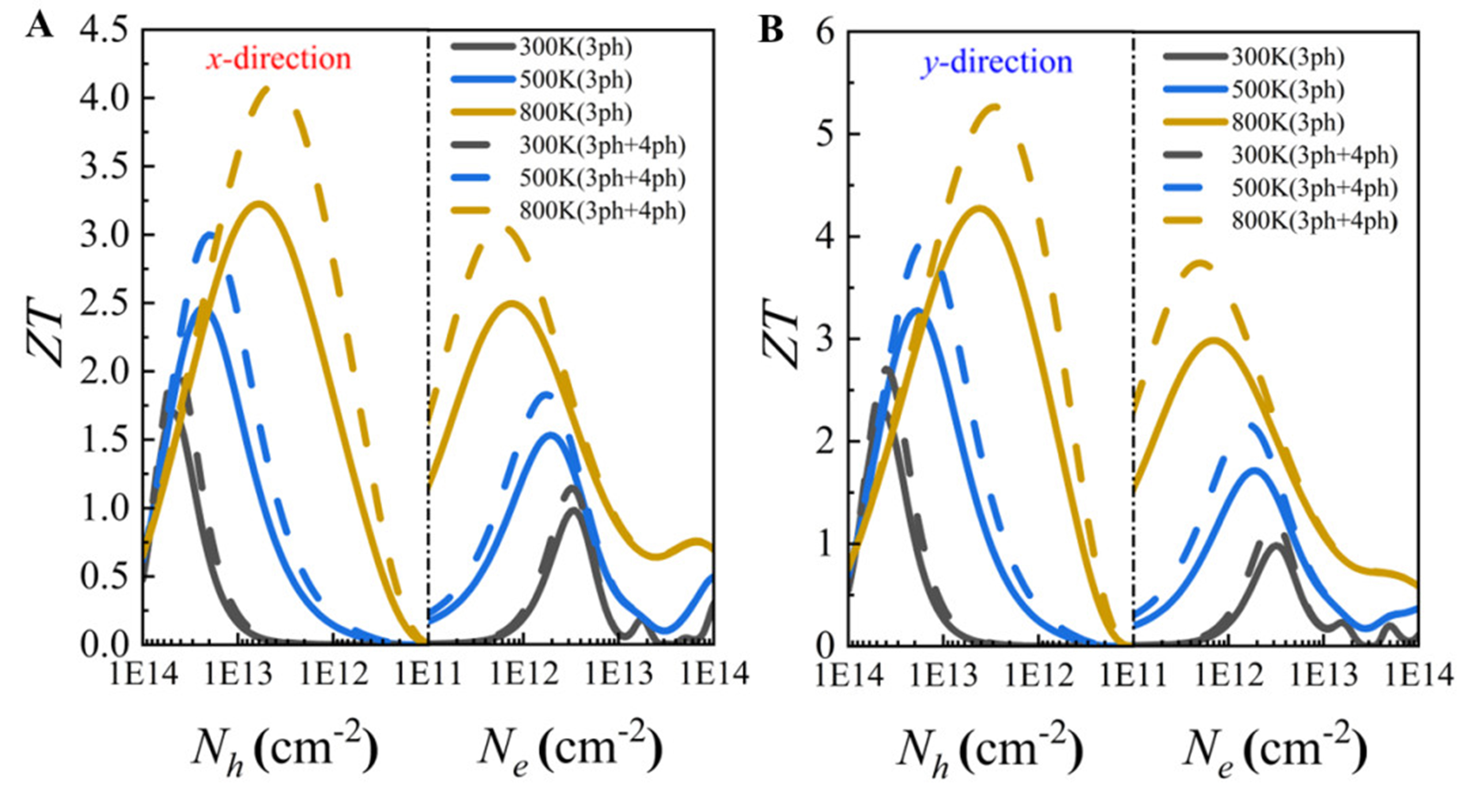

Combining its ultralow

Figure 15. Thermoelectric figure of merit (

The results reveal pronounced anisotropic thermoelectric transport behavior, with the ZT values under p-type doping significantly higher than those under n-type doping. This is primarily attributed to the increased electronic thermal conductivity under n-type conditions, which suppresses the enhancement of ZT. Moreover, the inclusion of four-phonon scattering mechanisms improves the accuracy of the calculated thermoelectric performance. At 800 K, the maximum ZT values along the x and y directions under p-type doping reach 4.1 and 5.3, respectively - an increase of approximately 23 % compared to the values considering only three-phonon scattering (3.2 and 4.3). For n-type doping, the ZT values also increase from 2.5 (x direction) and 2.9 (y direction) to 3.1 and 3.7, respectively, further confirming the critical role of four-phonon scattering in accurately evaluating thermoelectric performance.

Notably, the optimal ZT value of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure is 5.3, occurring at 800 K under p-type doping along the y-direction, which is significantly higher than the corresponding values for pure monolayer PbTe (1.55) and PbSe (1.3), highlighting the effectiveness of heterostructure design in substantially enhancing thermoelectric performance. Overall, the PbSe/PbTe heterostructure monolayer exhibits outstanding thermoelectric properties at high temperatures, achieving the maximum ZT within the carrier concentration range of 1012 cm−2 to 1013 cm−2, demonstrating good experimental feasibility and practical application potential.

Moreover, due to the weak interlayer interactions in the PbSe/PbTe monolayer vdW heterostructure, previous studies have indicated the potential for tuning its electronic structure via cross-plane compressive strain. It has been reported that such strain may modify the band structure and band alignment, thereby influencing carrier effective masses and transport properties[85,86]. Although this work does not directly investigate the effects of cross-plane compressive strain, based on these studies, we believe this tuning mechanism holds promise for optimizing the electronic performance of PbSe/PbTe heterostructures and warrants further exploration in future research.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on first-principles calculations, Boltzmann transport theory, and a four-phonon scattering model assisted by machine-learning interatomic potentials, this work systematically investigates the crystal structural stability, thermal transport, electronic transport, and thermoelectric performance of the 2D PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure. The mechanical, dynamical, and thermodynamical stabilities of the heterostructure are verified through calculations of the elastic modulus, phonon dispersion relations, and ab initio molecular dynamics simulations.

The PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure exhibits an excellent power factor with a peak value reaching 0.035 W · m−1 · K−2. In terms of thermal transport, owing to the pronounced anharmonicity of the material (Grüneisen parameter

Furthermore, unlike conventional materials where thermal conductivity is mainly dominated by acoustic phonons, optical phonons contribute more than 50 % to

In summary, this study not only reveals the outstanding thermoelectric performance and underlying microscopic mechanisms of the PbSe/PbTe monolayer heterostructure, highlighting the critical role of higher-order anharmonic scattering in regulating thermal transport, but also provides theoretical guidance and design strategies for enhancing thermoelectric performance via heterostructure engineering.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

Fang, Y. W. acknowledges the support from the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).

Authors' contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: Tan, R.; Zhang, K.; Fang, Y. W.

Performed the calculations: Tan, R.

All authors contribute to the interpretations and writing.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the findings can be found within the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

Fang, Y. W. is supported by the Extraordinary Grant of Spanish National Research Council (No. 2025ICT122).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. International Energy Agency. Global Energy Review 2025. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025. (accessed 9 Dec 2025).

2. Qin, B.; Kanatzidis, M. G.; Zhao, L. D. The development and impact of tin selenide on thermoelectrics. Science. 2024, 386, eadp2444.

3. Liu, S.; Bai, S.; Wen, Y.; et al. Quadruple-band synglisis enables high thermoelectric efficiency in earth-abundant tin sulfide crystals. Science. 2025, 387, 202-8.

4. Hu, L.; Luo, Y.; Fang, Y. W.; et al. High thermoelectric performance through crystal symmetry enhancement in triply doped diamondoid compound Cu2SnSe3. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2021, 11, 2100661.

5. Hu, L.; Fang, Y. W.; Qin, F.; et al. High thermoelectric performance enabled by convergence of nested conduction bands in Pb7Bi4Se13 with low thermal conductivity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4793.

6. Wang, Y.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. Machine learning for predictive design and optimization of high-performance thermoelectric materials: a review. J. Mater. Inf. 2025, 5, 41.

7. Sharma, S.; Kumar, S.; Schwingenschlögl, U. Arsenene and antimonene: two-dimensional materials with high thermoelectric figures of merit. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2017, 8, 044013.

8. Zhao, L. D.; Tan, G.; Hao, S.; et al. Ultrahigh power factor and thermoelectric performance in hole-doped single-crystal SnSe. Science. 2016, 351, 141-4.

9. Xiao, Y.; Wu, H.; Cui, J.; et al. Realizing high performance n-type PbTe by synergistically optimizing effective mass and carrier mobility and suppressing bipolar thermal conductivity. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 2486-95.

10. Zheng, Y.; Slade, T. J.; Hu, L.; et al. Defect engineering in thermoelectric materials: what have we learned? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 9022-54.

11. Wu, C.; Shi, X. L.; Wang, L.; et al. Defect engineering advances thermoelectric materials. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 31660-712.

12. Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Singh, S.; et al. Defect-engineering-stabilized AgSbTe2 with high thermoelectric performance. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2208994.

13. Fu, C. L.; Cheng, M.; Hung, N. T.; et al. AI-driven defect engineering for advanced thermoelectric materials. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2505642.

14. Moshwan, R.; Shi, X. L.; Liu, W. D.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z. G. Entropy engineering: an innovative strategy for designing high-performance thermoelectric materials and devices. Nano. Today. 2024, 58, 102475.

15. Wu, H.; Shi, X. L.; Li, M.; et al. Sandwich engineering advances ductile thermoelectrics. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2503020.

16. Su, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, S.; et al. High thermoelectric performance realized through manipulating layered phonon-electron decoupling. Science. 2022, 375, 1385-9.

17. Wang, S. J.; Panhans, M.; Lashkov, I.; et al. Highly efficient modulation doping: a path toward superior organic thermoelectric devices. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl9264.

18. Qin, F.; Hu, L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Integrating abnormal thermal expansion and ultralow thermal conductivity into (Cd,Ni)2Re2O7 via synergy of local structure distortion and soft acoustic phonons. Acta. Mater. 2024, 264, 119544.

19. Liu, D.; Qin, B.; Zhao, L. D. SnSe/SnS: multifunctions beyond thermoelectricity. Mater. Lab. 2022, 1, 220006.

20. Tang, S.; Ai, P.; Bai, S.; et al. Weak interatomic interactions induced low lattice thermal conductivity in 2D/2D PbSe/SnSe vdW heterostructure. Mater. Today. Phys. 2024, 43, 101398.

21. Gao, Z.; Liu, G.; Ren, J. High thermoelectric performance in two-dimensional tellurium: an ab initio study. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018, 10, 40702-9.

22. Patel, A.; Singh, D.; Sonvane, Y.; Thakor, P. B.; Ahuja, R. High thermoelectric performance in two-dimensional Janus monolayer material WS-X (X = Se and Te). ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020, 12, 46212-9.

23. Lee, M. J.; Ahn, J. H.; Sung, J. H.; et al. Thermoelectric materials by using two-dimensional materials with negative correlation between electrical and thermal conductivity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12011.

24. Sidike, A.; Zhang, B.; Dong, J.; Guo, G.; Duan, H.; Long, M. Realization of high thermoelectric performance of black phosphorus/black arsenic hybrid heterojunction nanoscale devices by interface engineering. Phys. B. Condens. Matter. 2024, 673, 415357.

25. Zhou, Y.; Wang, H. Enhanced in-plane thermoelectric properties achieved through the vertical van der Waals stacking of black phosphorus and Ti2C. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2023, 217, 124670.

26. Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Large enhancement of thermoelectric performance in MoS2/h-BN heterostructure due to vacancy-induced band hybridization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 13929-36.

27. Tang, S.; Bai, S.; Wu, M.; et al. Honeycomb-like puckered PbSe with wide bandgap as promising thermoelectric material: a first-principles prediction. Mater. Today. Energy. 2022, 23, 100914.

28. Tang, S.; Wu, M.; Bai, S.; Luo, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S. Honeycomb-like puckered PbTe monolayer: a promising n-type thermoelectric material with ultralow lattice thermal conductivity. J. Alloys. Compd. 2022, 907, 164439.

29. Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 1996, 54, 11169.

30. Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15-50.

32. Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1999, 59, 1758.

33. Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865.

34. Monkhorst, H. J.; Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B. 1976, 13, 5188.

35. Heyd, J.; Scuseria, G. E.; Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 8207-15.

36. Wang, R. Q.; Cao, T.; Lei, T. M.; Zhang, X.; Fang, Y. W. Control of magnetic transition, metal-semiconductor transition, and magnetic anisotropy in noncentrosymmetric monolayer Cr2Ge2Se3Te3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 127, 092402.

37. Cerqueira, T. F. T.; Fang, Y. W.; Errea, I.; Sanna, A.; Marques, M. A. L. Searching materials space for hydride superconductors at ambient pressure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2404043.

38. Deringer, V. L.; Tchougréeff, A. L.; Dronskowski, R. Crystal Orbital Hamilton Population (COHP) analysis as projected from plane-wave basis sets. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2011, 115, 5461-6.

39. Pöhls, J. H.; Luo, Z.; Aydemir, U.; et al. First-principles calculations and experimental studies of XYZ2 thermoelectric compounds: detailed analysis of van der Waals interactions. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018, 6, 19502-19.

40. Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104.

41. Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: a class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multiscale. Model. Simul. 2016, 14, 1153-73.

42. Novikov, I. S.; Gubaev, K.; Podryabinkin, E. V.; Shapeev, A. V. The MLIP package: moment tensor potentials with MPI and active learning. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2020, 2, 025002.

43. Togo, A.; Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 2015, 108, 1-5.

44. Han, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Feng, T.; Ruan, X. FourPhonon: an extension module to ShengBTE for computing four-phonon scattering rates and thermal conductivity. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 270, 108179.

45. Mortazavi, B.; Podryabinkin, E. V.; Novikov, I. S.; Rabczuk, T.; Zhuang, X.; Shapeev, A. V. Accelerating first-principles estimation of thermal conductivity by machine-learning interatomic potentials: a MTP/ShengBTE solution. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 258, 107583.

46. Li, W.; Carrete, J.; Katcho, N. A.; Mingo, N. ShengBTE: a solver of the Boltzmann transport equation for phonons. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 1747-58.

47. Chen, X. K.; Zhang, E. M.; Wu, D.; Chen, K. Q. Strain-induced medium-temperature thermoelectric performance of Cu4TiSe4: the role of four-phonon scattering. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 19, 044052.

48. Madsen, G. K. H;. Singh. D. J. BoltzTraP. A code for calculating band-structure dependent quantities. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2006, 175, 67-71.

49. Qian, G. L.; Xie, Q.; Liang, Q.; Luo, X. Y.; Wang, Y. X. Electronic properties and photocatalytic water splitting with high solar-to-hydrogen efficiency in a hBNC/Janus WSSe heterojunction: first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 2023, 107, 155306.

50. Lü, J.; Xu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Mo, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Tao, X. Four-phonon enhanced the thermoelectric properties of ScSX (X = Cl, Br, and I) monolayers. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 24734-47.

51. Savin, A.; Jepsen, O.; Flad, J.; Andersen, O. K.; Preuss, H.; von Schnering, H. G. Electron localization in solid-state structures of the elements: the diamond structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1992, 31, 187-8.

52. Becke, A. D.; Edgecombe, K. E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5397-403.

53. Burdett, J. K.; McCormick, T. A. Electron localization in molecules and solids: the meaning of ELF. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998, 102, 6366-72.

54. Fang, Y. W.; Chen, H. Design of a multifunctional polar metal via first-principles high-throughput structure screening. Commun. Mater. 2020, 1, 1.

55. Fang, Y. W.; Fisher, C. A. J.; Kuwabara, A.; et al. Lattice dynamics and ferroelectric properties of the nitride perovskite LaWN3. Phys. Rev. B. 2017, 95, 014111.

56. Alizadeh, Z.; Fang, Y. W.; Errea, I.; Mohammadizadeh, M. R. From superconductivity to non-superconductivity in LiPdH: a first principles approach. Phys. Rev. B. 2025, 112, 104308.

57. Li, Y.; Li, J.; Tian, J.; Liu, H.; Shi, J. A first-principles study of 2D Bi-based BiOClBr, BiOClI, and BiOBrI monolayers with ultralow lattice thermal conductivities for thermoelectric application. ACS. Appl. Nano. Mater. 2024, 7, 15086-95.

58. Lajevardipour, A.; Neek-Amal, M.; Peeters, F. M. Thermomechanical properties of graphene: valence force field model approach. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2012, 24, 175303.

59. Hess, P. Relationships between the elastic and fracture properties of boronitrene and molybdenum disulfide and those of graphene. Nanotechnology. 2017, 28, 064002.

60. Jain, A.; McGaughey, A. J. H. Strongly anisotropic in-plane thermal transport in single-layer black phosphorene. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8501.

61. Hossain, M. T.; Rahman, M. A. A first principle study of the structural, electronic, and temperature-dependent thermodynamic properties of graphene/MoS2 heterostructure. J. Mol. Model. 2020, 26, 40.

62. Xiang, F.; Tan, R.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, K. High performance photocatalytic water splitting in two-dimensional BN/Janus SnSSe heterojunctions: ab initio study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 7965-74.

63. Ding, J.; Liu, C.; Xi, L.; Xi, J.; Yang, J. Thermoelectric transport properties in chalcogenides ZnX (X=S, Se): from the role of electron-phonon couplings. J. Materiomics. 2021, 7, 310-9.

64. Chaudhuri, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Das, A. K.; Das, G. P.; Dev, B. N. Understanding the role of four-phonon scattering in the lattice thermal transport of monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B. 2024, 109, 235424.

65. Christensen, M.; Abrahamsen, A. B.; Christensen, N. B.; et al. Avoided crossing of rattler modes in thermoelectric materials. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 811-5.

66. Hu, J.; Zhu, J.; Dong, X.; et al. Breaking the minimum limit of thermal conductivity of Mg3Sb2 thermoelectric mediated by chemical alloying induced lattice instability. Small. 2023, 19, 2301382.

67. Xie, Q. Y.; Ma, J. J.; Liu, Q. Y.; et al. Low thermal conductivity and high performance anisotropic thermoelectric properties of XSe (X = Cu, Ag, Au) monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 7303-10.

68. Zhu, Y.; Ye, T.; Wen, H.; et al. Quasi-2D phonon transport in diamond nanosheet. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2407333.

69. Lindsay, L.; Broido, D. A.; Reinecke, T. L. Ab initio thermal transport in compound semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2013, 87, 165201.

70. Xie, Q. Y.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, K. W.; Wang, B. T. Anharmonic phonon self-energy and anomalous thermal transport in the quaternary compound BaAg2SnSe4. Phys. Rev. B. 2024, 110, 045203.

71. Jian, M.; Feng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, G.; Singh, D. J. Ultralow lattice thermal conductivity induced by anharmonic cation rattling and significant role of intrinsic point defects in TlBiS2. Phys. Rev. B. 2023, 107, 245201.

72. Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ni, J.; Meng, S.; Dai, Z. Phonon hardening and the effect of phonon transport in cubic antiperovskites A3FB (A = Li, Na; B = Se, Te) induced by quartic anharmonicity. Mater. Today. Commun. 2023, 35, 105450.

73. Minhas, H.; Das, S.; Pathak, B. Importance of four-phonon interactions in lattice thermal conductivity and thermoelectrics: a case study. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2023, 6, 7305-16.

74. Feng, Z.; Fu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Singh, D. J. Zintl chemistry leading to ultralow thermal conductivity, semiconducting behavior, and high thermoelectric performance of hexagonal KBaBi. Phys. Rev. B. 2021, 103, 224101.

75. Yue, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ni, J.; Meng, S.; Dai, Z. Strong quartic anharmonicity, ultralow thermal conductivity, high band degeneracy and good thermoelectric performance in Na2TlSb. npj. Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 17.

76. Bai, S.; Zhang, J.; Wu, M.; et al. Theoretical prediction of thermoelectric performance for layered LaAgOX (X = S, Se) materials in consideration of the four-phonon and multiple carrier scattering processes. Small. Methods. 2023, 7, 2201368.

77. Feng, T.; Lindsay, L.; Ruan, X. Four-phonon scattering significantly reduces intrinsic thermal conductivity of solids. Phys. Rev. B. 2017, 96, 161201.

78. Gao, Z.; Lv, M.; Liu, M.; et al. Novel layered As2Ge with a pentagonal structure for potential thermoelectrics. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2025, 13, 5762-70.

79. Peng, R.; Ma, Y.; He, Z.; Huang, B.; Kou, L.; Dai, Y. Single-layer Ag2S: a two-dimensional bidirectional auxetic semiconductor. Nano. Lett. 2019, 19, 1227-33.

80. Ganose, A. M.; Park, J.; Faghaninia, A.; Woods-Robinson, R.; Persson, K. A.; Jain, A. Efficient calculation of carrier scattering rates from first principles. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2222.

81. Nautiyal, H.; Scardi, P. Thermoelectric properties and thermal transport in two-dimensional GaInSe3 and GaInTe3 monolayers: a first-principles study. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 135, 174301.

82. Feng, S.; Qi, H.; Hu, W.; Zu, X.; Xiao, H. A theoretical prediction of thermoelectrical properties for novel two-dimensional monolayer ZrSn2N4. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 13474-87.

83. Pandit, A.; Hamad, B. Thermoelectric and lattice dynamics properties of layered MX (M = Sn, Pb; X = S, Te) compounds. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 538, 147911.

84. Stojanovic, N.; Maithripala, D. H. S.; Berg, J. M.; Holtz, M. Thermal conductivity in metallic nanostructures at high temperature: electrons, phonons, and the Wiedemann-Franz law. Phys. Rev. B. 2010, 82, 075418.

85. Zhou, W. X.; Wu, C. W.; Cao, H. R.; Zeng, Y. J.; Xie, G.; Zhang, G. Abnormal thermal conductivity increase in β-Ga2O3 by an unconventional bonding mechanism using machine-learning potential. Mater. Today. Phys. 2025, 52, 101677.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].