The synergy of geometric tolerance factor and machine learning in discovering stable materials

Abstract

Assessing stability remains a fundamental prerequisite for deploying materials across a wide range of applications, including batteries, catalysts, and photovoltaics. However, first-principles stability checks such as phonon dispersion and energy above hull calculations typically require days to weeks of computing time per composition, creating a critical bottleneck for truly high-throughput discovery. In this Perspective, we highlight the underutilized potential of geometric tolerance factors (Tf) as lightweight yet informative indicators for rapid stability assessment. First, we review the Tf developed for representative materials systems, including perovskites, spinels, and garnets, and analyze recent cases where such indicators have been integrated into AI-driven materials discovery. Then, we identify key open challenges in designing Tf that are both accurate and generalizable, as well as in effectively incorporating them into AI frameworks. The potential solutions, including active learning for multi-composition structure, electron density profile-based learning for ionic radii estimation, and diffusion model for thermodynamic and kinetic stability, are proposed to address these challenges. The synergy between Tf-based heuristics and advanced AI models has the potential to triage vast compositional spaces before committing to expensive first-principles stability validation, thereby enabling broader innovations in materials design and deployment.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Predicting the thermodynamic stability remains one of the most fundamental challenges in materials science. Stability is not only a prerequisite for synthesizability but also a critical filter before exploring target properties such as conductivity, magnetism, or catalytic activity[1-3]. As generative models, including diffusion models and large language models, become increasingly central to materials discovery, the ability to generate stable candidates has emerged as a core design objective[4-6]. However, these approaches often lack simple, interpretable, and transferable criteria that can guide generation toward chemically and geometrically feasible regions of the compositional space.

This gap highlights the renewed relevance of tolerance factors (Tf), which provide a geometric measure of structural stability for a given composition. Initially formulated for perovskite materials[7,8], the concept has since been generalized to other families, such as spinels[9], garnets[10,11], and quaternary compounds[12,13], where packing efficiency and ionic size compatibility govern the formation and stability of crystal structures. Tf has the appeal of physical interpretability and computational efficiency, making it ideal for rapid screening. However, despite its simplicity and relevance, Tf has not been fully integrated into modern AI-driven materials pipelines. The challenge lies in how to embed such universal structural priors into generative or predictive models in a flexible way, leading to realizable materials. For example, generative models guided by geometric constraints or reinforced by structural stability feedback from density functional theory (DFT) or ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations can potentially learn to discover novel but stable geometries[14,15], extending the scope of materials far beyond canonical design spaces[16,17].

Despite the historical significance, Tf has received limited attention in the broader landscape of AI-driven materials discovery. To date, its application has been largely confined to a few prototypical systems, many other materials exhibiting similar geometric correlations remain underexplored. Here, we aim to fill this gap by summarizing the Tf frameworks used in representative systems, and demonstrating how Tf can be integrated into AI-based materials pipelines. Finally, we articulate key challenges that need to be addressed to generalize Tf across broader domains, and propose potential solutions. Together, these strategies suggest a promising route toward discovering stable materials more efficiently, with Tf serving as lightweight yet informative guide in the design space.

GEOMETRIC TOLERANCE FACTORS FOR REPRESENTATIVE MATERIALS SYSTEMS

The concept of the Tf originated from geometric considerations of ionic packing in perovskite structures[7,8]. The classical Goldschmidt Tf is defined as

where rA, rB, and rX are the ionic radii of the A-site, B-site, and X-site, respectively. This formulation is derived from the idealized cubic ABX3 perovskite, assuming hard-sphere models and corner-sharing BX6 octahedra. A Tf close to unity indicates a stable cubic or slightly distorted structure, while values outside this range often imply instabilities or transformations to non-perovskite phases. Over time, similar radius-based formulations have been generalized to other compound families, by adapting the geometric motif and coordination environments specific to each lattice type.

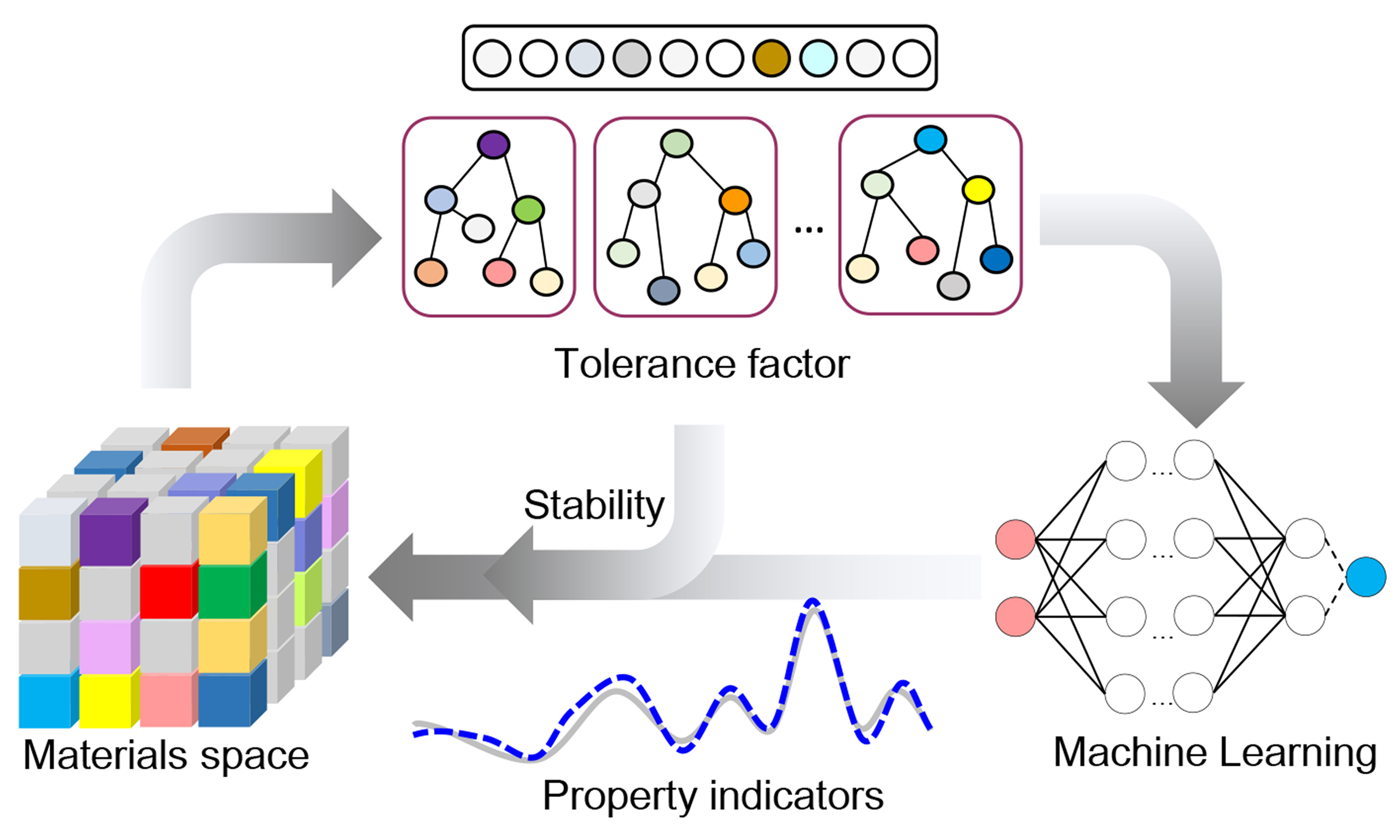

In this study, we curated geometric Tf expressions across eight major structural families [Figure 1], including simple perovskite (ABX3)[7,8], double perovskite (A2BB’X6)[18], spinel (AB2X4)[9], garnet

Figure 1. Geometric Tf across representative structural families. Different materials systems are distinguished by diverse colors, and the evaluation criteria of Tf and space groups corresponding to the structures are also provided.

T f serves as a simple yet powerful tool for pre-screening structural formability, guiding chemical substitution strategies. However, their effectiveness is often limited by the rigid assumptions underlying their derivation, such as fixed coordination environments, static ionic radii, and neglect of dynamic effects. These oversimplifications can lead to systematic biases. For instance, the exclusion of metastable phases that are kinetically accessible or thermodynamically competitive under synthesis conditions, or false negatives where functionally promising materials are prematurely discarded[24,25].

HIGH-THROUGHPUT MATERIALS SCREENING WITH TOLERANCE FACTORS

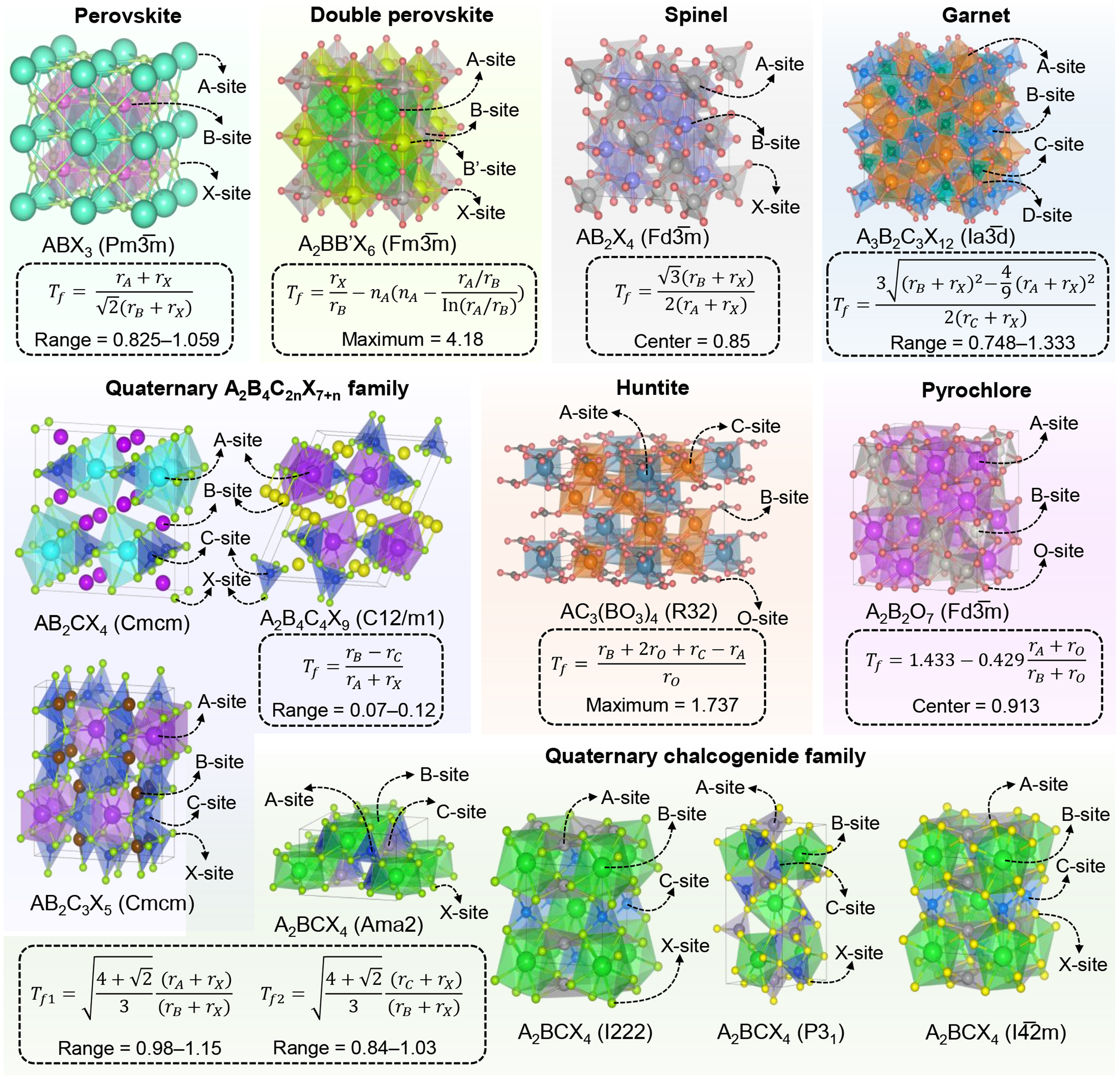

At this stage, modeling with Tf diverges slightly from typical methodologies [Figure 2A]. For instance, when employing Tf for high-throughput screening, researchers first define a specific system, to ensure that all investigated materials adhere to consistent atomic arrangement criteria. The next step involves constructing a dataset comprising site-specific elemental compositions and their associated properties. Leveraging the known combinations, researchers can generate unexplored derivative configurations for further investigation.

Figure 2. AI workflow and case studies with geometric tolerance factor. (A) General workflow incorporating geometric Tf for AI-driven materials discovery. Unlike standard approaches, this method eliminates the need for geometric optimization of unknown crystal structures prior to property prediction (the red dotted arrow); (B) Garnet discovery with Tf; (C) Chalcogenide discovery with Tf.

In systems characterized by a consistent atomic arrangement, descriptors for AI modeling can be constructed solely from elemental attributes. Composition-based descriptors generally fall into two categories: (1) hand-crafted descriptors derived from isolated elemental properties, such as electronegativity, first ionization energy, atomic number[26,27]. Mathematical operations can be applied to these features to capture variations; (2) learned embeddings obtained from pre-trained models (e.g., ElemNet[28], CrabNet[29]) that encode chemical compositions information. These representations can then be fine-tuned on task-specific datasets to improve performance and adaptability to the problem at hand.

Both approaches exhibit distinct advantages and limitations. The first method benefits from its minimal reliance on extensive feature parameters, as it primarily leverages domain expertise. Furthermore, the features are inherently interpretable. This transparency is particularly valuable for electronic structure-based insights. However, the manually designed features may lack comprehensiveness, failing to capture complex relationships. In contrast, the second method employs features derived from pre-trained models. These descriptors enable superior generalization to unexplored regions of chemical space[30,31]. It was also found that this method has at least 30% lower error in formation energy prediction than the first method, even though it takes 3-5 times longer to train[28]. Thus, in practical applications, the choice between these descriptors should be guided by critical factors such as dataset scale, elemental diversity, and the trade-off between interpretability and predictive power.

The next step involves leveraging AI to predict key materials properties, such as band gap and bulk modulus, based on combinations of elements at different crystallographic sites[32]. In the design of garnet-type electrolytes [Figure 2B], for example, researchers employed the Tf to preliminary assess the geometric stability of 29,008 candidate compositions[11], narrowing the pool to 7,067 viable structures. During validation, 47 out of 49 (95.92%) predicted garnets were successfully optimized, demonstrating the robustness of the Tf-driven workflow. Similarly, in the discovery of quaternary materials[13], Tf helped narrow down an initial dataset of 2,700 compounds to 380 promising candidates [Figure 2C]. Subsequent hierarchical clustering identified materials with superior optoelectronics performance, where Ag2BaTiSe4 was experimentally confirmed and achieved a power conversion efficiency of 20.08% in solar cell applications[33]. We note that rigorous AIMD simulations or experimental synthesis remain essential for the practical deployment of any newly identified materials.

ONGOING CHALLENGES AND POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

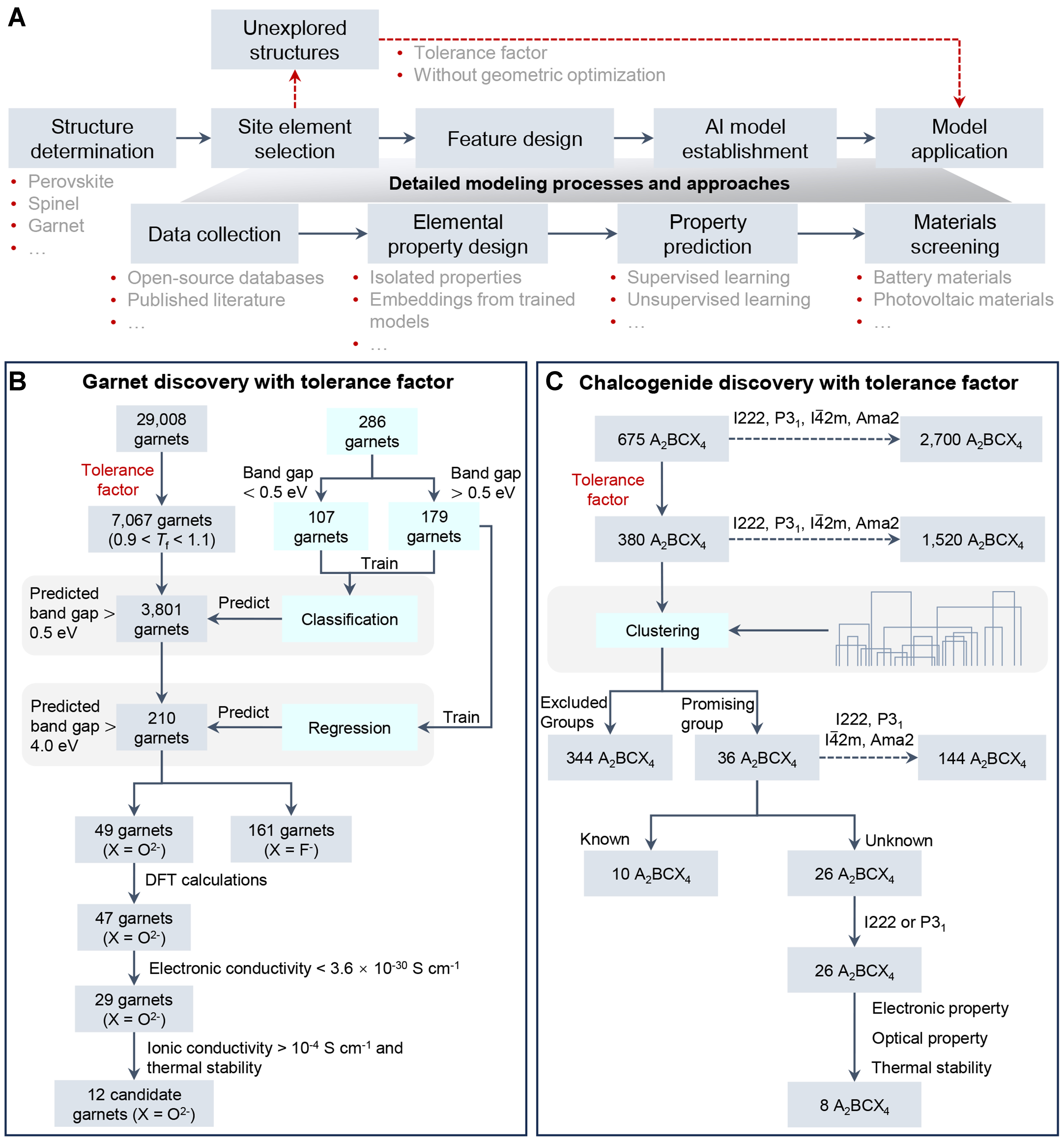

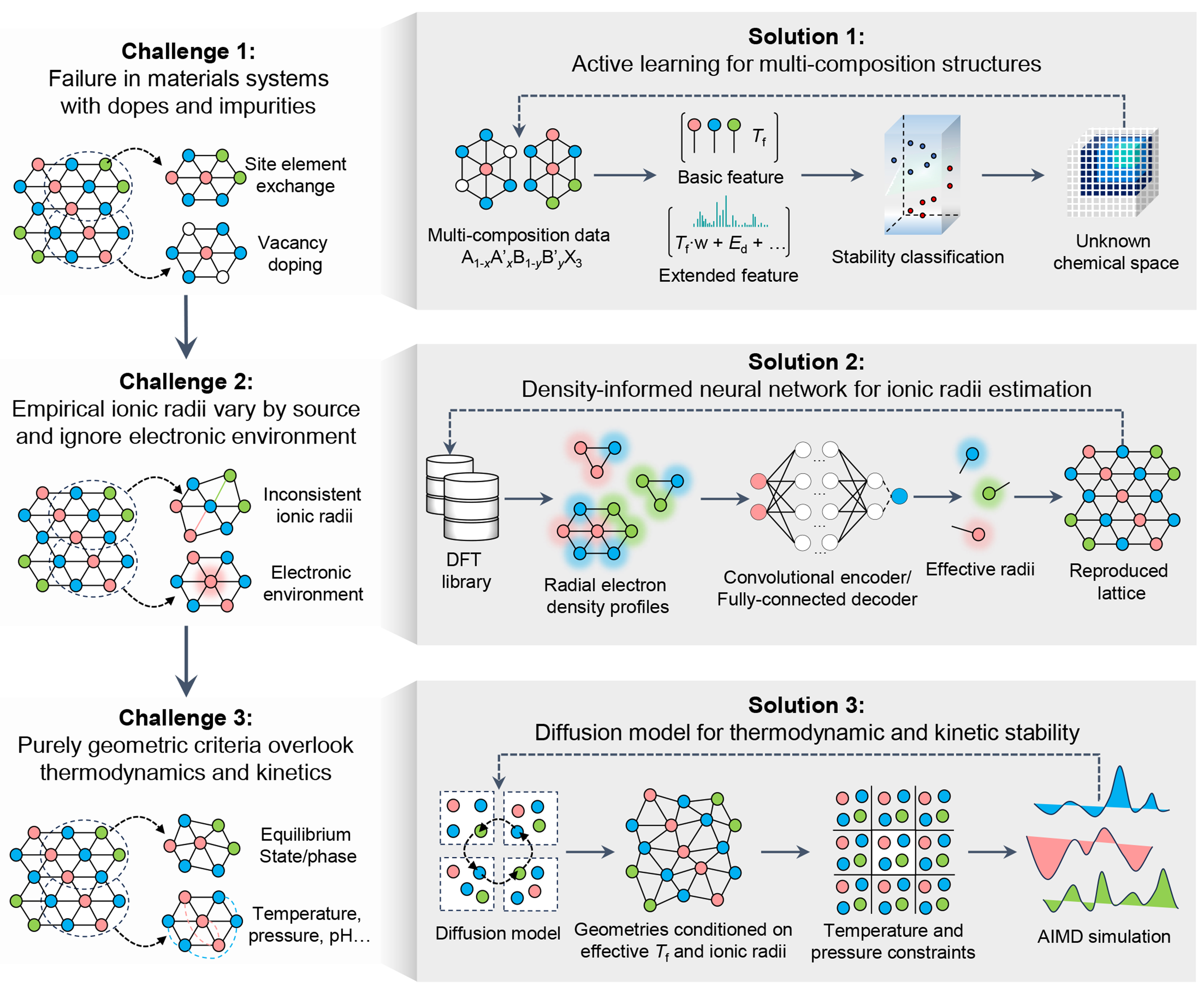

There are still many challenges to improve the versatility and accuracy of Tf. In this section, we propose three key challenges and corresponding solutions [Figure 3] to fully realize the important role of Tf in materials discovery.

Figure 3. Ongoing challenges and corresponding potential solutions. Three ongoing challenges and corresponding solutions in materials discovery with universal tolerance factor are proposed.

(1) Failure in materials systems with dopes and defects: Traditional Tf struggles to capture the effects of doping and defects, such as vacancies, substitutions, or interstitials, which can introduce local distortion and alter ionic radii. Substitutional doping may shift lattice parameters gradually, while intrinsic defects often cause more severe local distortions. These changes disrupt the fixed coordination assumptions of Tf, leading to unreliable stability assessments.

Solution: One solution to this challenge is to build an active learning model to mine the structural information of multiple components. Taking perovskite (ABX3) as an example, by collecting and establishing multi-component data (A1-xA’xB1-yB’yX3) using open-source databases (e.g., Materials Cloud[34], Automatic-Flow for Materials Discovery[35], and Novel Materials Discovery[36]), a weighted Tf is constructed according to the chemical ratio of the multiple components, and then a stability prediction model is constructed. In the unknown chemical space, high-precision DFT calculations are performed based on the uncertainty of the prediction results and fed back to the data set. This approach strikes a balance between efficiency and accuracy: instead of exhaustively running DFT for all configurations, active learning (AL) reduces the number of required DFT calculations, while achieving comparable or even better performance.

(2) Empirical ionic radii vary by source and ignore environment: The values of ionic radii currently come from multiple sources, and change with the ion coordination number. Sometimes, different combinations of cations will cause the ionic radii to change, making the calculated Tf uncertain. In addition, the ionic radii currently used are static and do not take into account their electronic environment, which may make the calculated Tf unreliable.

Solution: A solution to this challenge is to predict ionic radii from electron density profiles[37]. After geometric optimization, DFT computes ground-state electron densities for various crystals, from which reference ionic radii are derived (e.g., via Bader analysis or density isosurfaces[38,39]). These serve as high-fidelity training data. A hybrid model combining convolutional neural network (CNN) and multilayer perceptron (MLP)[40] is then used, with features expressed as radial functions or spherical harmonics. The predicted radii are further adjusted to align with experimental lattice parameters, enforcing geometric consistency through post-processing or constraint-based loss functions. Validation is performed on a hold-out test set of diverse structures not seen during training, and performance is benchmarked against traditional radius tables and structure-based heuristics. By learning directly from electron density, the method captures context-dependent ion sizes and generalizes beyond traditional tabulated radii.

(3) Purely geometric criteria overlook thermodynamics and kinetics: Tf fails to account for thermodynamic stability or kinetic formation barriers. For instance, some compositions may satisfy geometric Tf criteria yet remain unrealizable due to unfavorable formation energies. Similarly, metastable phases with promising properties might be overlooked because their synthesis requires non-equilibrium conditions that geometric parameters cannot predict.

Solution: A closed-loop diffusion framework can be developed to explore thermodynamically and kinetically stable compositions guided by geometric constraints. The diffusion model is conditioned on geometric priors and thermodynamic parameters (temperature and pressure), enabling the generation of compositions with structural feasibility. These candidates are filtered using AIMD simulations to assess kinetic stability. Feedback from AIMD trajectories, such as mean square displacements, can be incorporated to refine the diffusion model via reinforcement or reweighting, allowing the generation process to gradually shift toward kinetically robust chemical space. This iterative scheme bridges composition generation and atomistic validation, enabling efficient discovery of stable materials.

CONCLUSION

Recent progress in both Tf and AI has laid a solid groundwork for evaluating materials stability. Nevertheless, key obstacles persist, such as the lack of universally applicable and accurate tolerance descriptors. Addressing these limitations will require integrated strategies such as data-driven estimation of effective ionic radii, and the deployment of closed-loop AI models under realistic constraints. Furthermore, with the rise of non-ideal, disordered, and dynamically evolving systems, extending Tf to geodesic/probabilistic metrics open new frontiers for predictive modeling in 2D materials and flexible framework materials, where atomic deviations follow non-Euclidean pathways. With the continued convergence of AI methodologies, we foresee a transformative shift: Tf-informed AI frameworks will unlock new opportunities in diverse domains including energy storage, sustainable systems, and optoelectronics, paving the way toward accelerated discovery and design of stable, high-performance materials.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge members of the PEESE group for discussions related to the preparation of this work.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, visualization, data curation, writing - original draft: Wang, Z.

Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, resources, writing - original draft, review and editing: You, F.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This project is partially supported by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a program of Schmidt Sciences, LLC.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Merchant, A.; Batzner, S.; Schoenholz, S. S.; Aykol, M.; Cheon, G.; Cubuk, E. D. Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature 2023, 624, 80-5.

2. Zeni, C.; Pinsler, R.; Zügner, D.; et al. A generative model for inorganic materials design. Nature 2025, 639, 624-32.

3. Xu, P.; Ma, Y.; Lu, W.; Li, M.; Zhao, W.; Dai, Z. Multi-objective optimization in machine learning assisted materials design and discovery. J. Mater. Inf. 2025, 5, 26.

4. Westermayr, J.; Gilkes, J.; Barrett, R.; Maurer, R. J. High-throughput property-driven generative design of functional organic molecules. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 139-48.

5. Biyela, S.; Dihal, K.; Gero, K. I.; et al. Generative AI and science communication in the physical sciences. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2024, 6, 162-5.

6. Njirjak, M.; Žužić, L.; Babić, M.; et al. Reshaping the discovery of self-assembling peptides with generative AI guided by hybrid deep learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 1487-500.

7. Li, Z.; Yang, M.; Park, J.; Wei, S.; Berry, J. J.; Zhu, K. Stabilizing perovskite structures by tuning tolerance factor: formation of formamidinium and cesium lead iodide solid-state alloys. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 284-92.

8. Liu, X.; Luo, D.; Lu, Z. H.; et al. Stabilization of photoactive phases for perovskite photovoltaics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7, 462-79.

9. Song, Z.; Liu, Q. Tolerance factor and phase stability of the normal spinel structure. Cryst. Growth. Des. 2020, 20, 2014-8.

10. Song, Z.; Zhou, D.; Liu, Q. Tolerance factor and phase stability of the garnet structure. Acta. Crystallogr. C. Struct. Chem. 2019, 75, 1353-8.

11. Wang, Z.; Lin, X.; Han, Y.; et al. Harnessing artificial intelligence to holistic design and identification for solid electrolytes. Nano. Energy. 2021, 89, 106337.

12. Zhu, T.; Huhn, W. P.; Wessler, G. C.; et al. I2–II–IV–VI4 (I = Cu, Ag; II = Sr, Ba; IV = Ge, Sn; VI = S, Se): chalcogenides for thin-film photovoltaics. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7868-79.

13. Wang, Z.; Cai, J.; Wang, Q.; Wu, S.; Li, J. Unsupervised discovery of thin-film photovoltaic materials from unlabeled data. npj. Comput. Mater. 2021, 7, 596.

14. Curtarolo, S.; Hart, G. L.; Nardelli, M. B.; Mingo, N.; Sanvito, S.; Levy, O. The high-throughput highway to computational materials design. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 191-201.

15. Griesemer, S. D.; Xia, Y.; Wolverton, C. Accelerating the prediction of stable materials with machine learning. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 934-45.

16. Wu, Z.; Zhang, O.; Wang, X.; et al. Leveraging language model for advanced multiproperty molecular optimization via prompt engineering. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 1359-69.

17. Jiang, X.; Wang, W.; Tian, S.; Wang, H.; Lookman, T.; Su, Y. Applications of natural language processing and large language models in materials discovery. npj. Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 1554.

18. Bartel, C. J.; Sutton, C.; Goldsmith, B. R.; et al. New tolerance factor to predict the stability of perovskite oxides and halides. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav0693.

19. Bassen, G.; Wilfong, B.; Bunstine, W.; Edmiston, N.; Siegler, M. A.; McQueen, T. M. Tolerance factor approach for the design of quaternary materials as applied to the A2Ln4Cu2nQ7+n homologous series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 25190-9.

20. Molokeev, M. S.; Kuznetsov, S. O. Tolerance factor for huntite-family compounds. Phys. Solid. State. 2020, 62, 2058-62.

21. Mouta, R.; Silva, R. X.; Paschoal, C. W. Tolerance factor for pyrochlores and related structures. Acta. Crystallogr. B. Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2013, 69, 439-45.

22. Smith, M.; Li, Z.; Landry, L.; Merz, K. M. Jr.; Li, P. Consequences of overfitting the van der Waals radii of ions. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2023, 19, 2064-74.

23. Marchenko, E. I.; Fateev, S. A.; Eremin, N. N.; Chen, Q.; Goodilin, E. A.; Tarasov, A. B. Crystal chemical insights on lead iodide perovskites doping from revised effective radii of metal ions. ACS. Materials. Lett. 2021, 3, 1377-84.

24. Turnley, J. W.; Agarwal, S.; Agrawal, R. Rethinking tolerance factor analysis for chalcogenide perovskites. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 4802-8.

25. Mondal, D.; Mahadevan, P. Structural distortions in hybrid perovskites revisited. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 4254-61.

26. Antoniuk, E. R.; Cheon, G.; Wang, G.; Bernstein, D.; Cai, W.; Reed, E. J. Predicting the synthesizability of crystalline inorganic materials from the data of known material compositions. npj. Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 1114.

27. Vasylenko, A.; Antypov, D.; Gusev, V. V.; Gaultois, M. W.; Dyer, M. S.; Rosseinsky, M. J. Element selection for functional materials discovery by integrated machine learning of elemental contributions to properties. npj. Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 1072.

28. Jha, D.; Ward, L.; Paul, A.; et al. ElemNet: deep learning the chemistry of materials from only elemental composition. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17593.

29. Hargreaves, C. J.; Gaultois, M. W.; Daniels, L. M.; et al. A database of experimentally measured lithium solid electrolyte conductivities evaluated with machine learning. npj. Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 951.

30. Kang, Y.; Kim, J. ChatMOF: an artificial intelligence system for predicting and generating metal-organic frameworks using large language models. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4705.

31. Zheng, Y.; Koh, H. Y.; Ju, J.; et al. Large language models for scientific discovery in molecular property prediction. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 437-47.

32. Butler, K. T.; Davies, D. W.; Cartwright, H.; Isayev, O.; Walsh, A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 2018, 559, 547-55.

33. Dass KT, Hossain MK, Marasamy L. Highly efficient emerging Ag2BaTiSe4 solar cells using a new class of alkaline earth metal-based chalcogenide buffers alternative to CdS. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1473.

34. Talirz, L.; Kumbhar, S.; Passaro, E.; et al. Materials Cloud, a platform for open computational science. Sci. Data. 2020, 7, 299.

35. Curtarolo, S.; Setyawan, W.; Hart, G. L.; et al. AFLOW: an automatic framework for high-throughput materials discovery. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2012, 58, 218-26.

36. Sbailò, L.; Fekete, Á.; Ghiringhelli, L. M.; Scheffler, M. The NOMAD Artificial-Intelligence Toolkit: turning materials-science data into knowledge and understanding. npj. Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 935.

37. Szymanski, N. J.; Smith, A.; Daoutidis, P.; Bartel, C. J. Topological descriptors for the electron density of inorganic solids. ACS. Materials. Lett. 2025, 7, 2158-64.

38. Hylton-Farrington, C. M.; Remsing, R. C. Dynamic local symmetry fluctuations of electron density in halide perovskites. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 9442-59.

39. Feng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, B. Efficient sampling for machine learning electron density and its response in real space. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2025, 21, 691-702.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].