Adverse outcome pathway of ambient fine particulate matter-induced respiratory toxicity: role of non-coding RNAs

Abstract

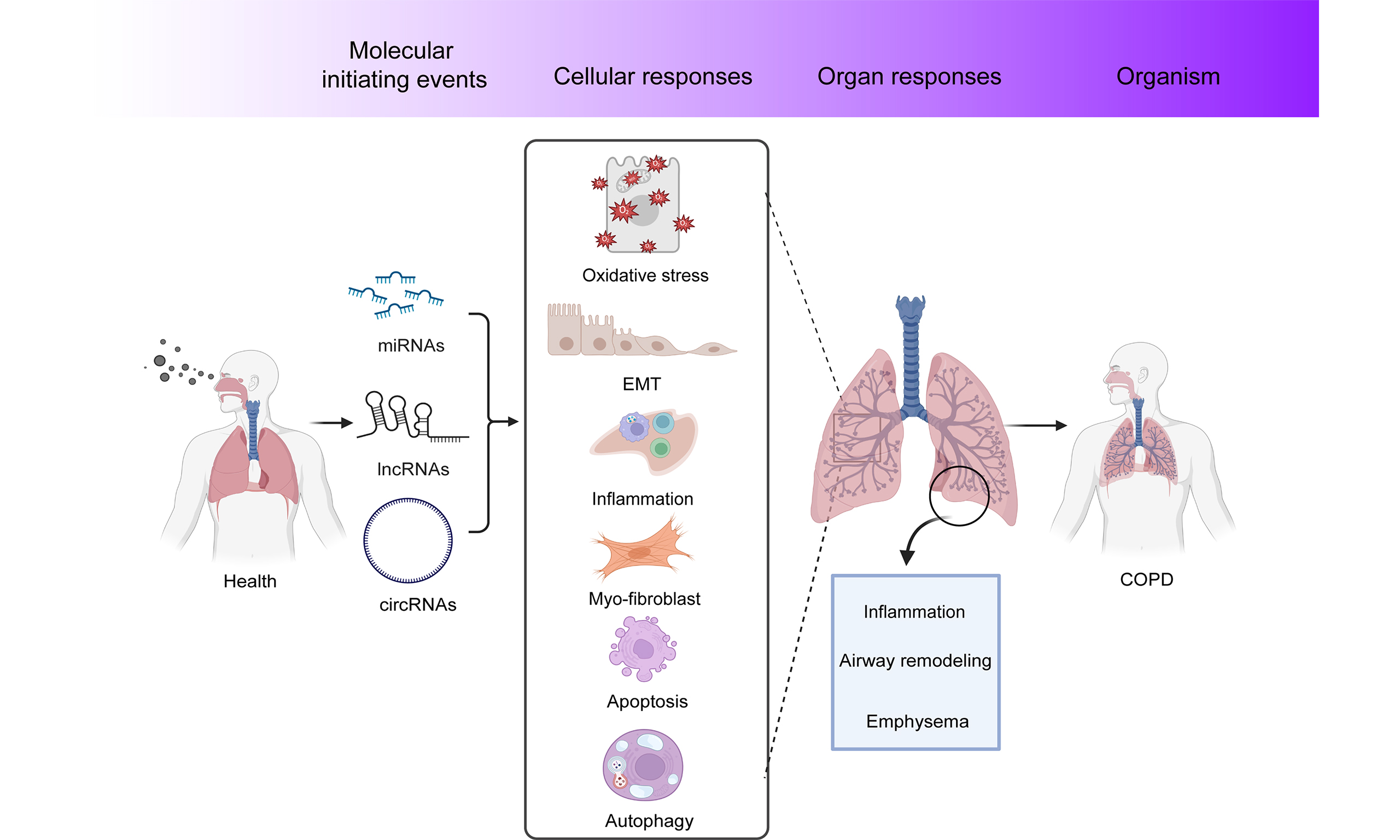

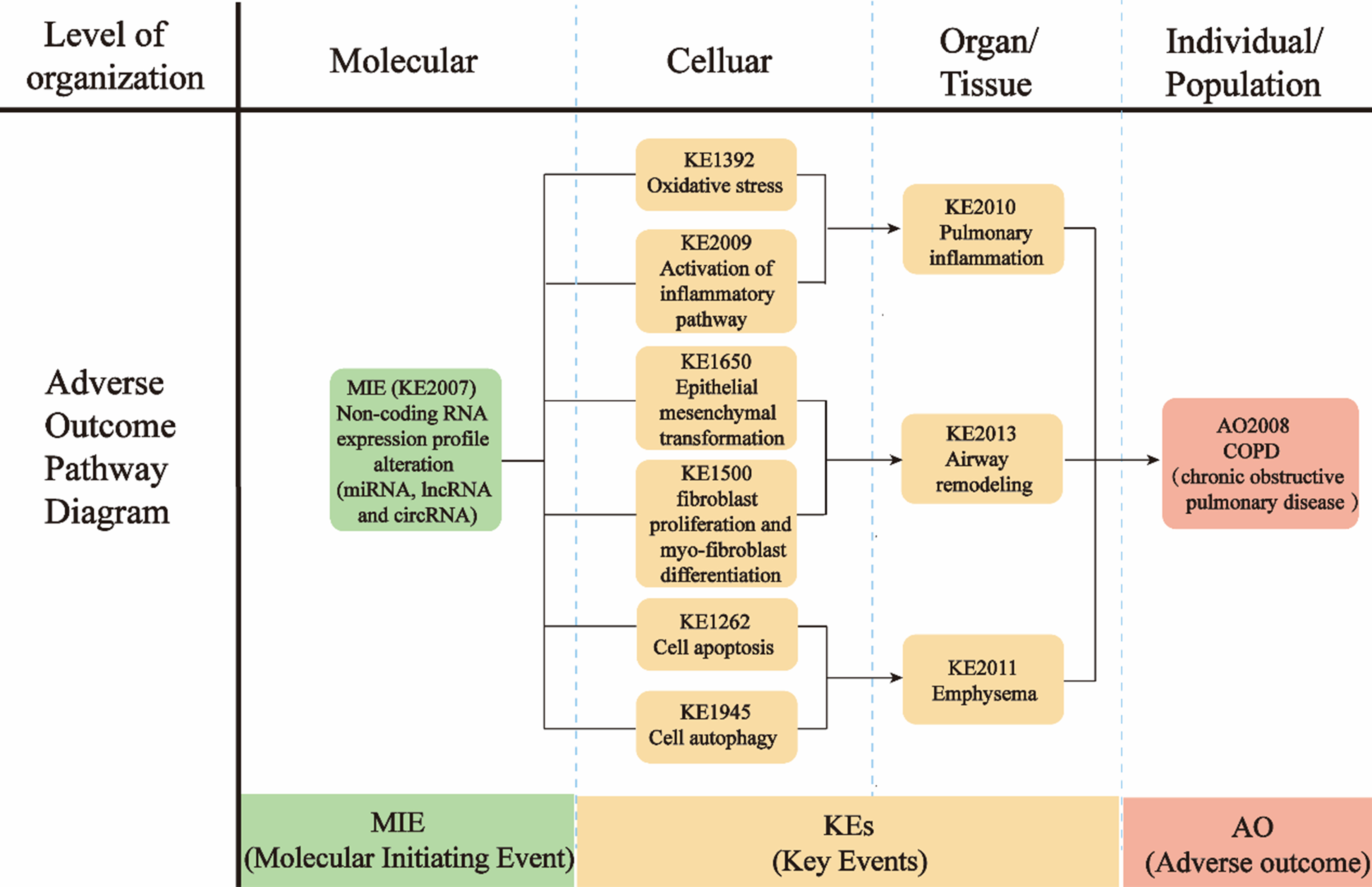

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure has been recognized as one of the risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). With increased PM2.5-related research, the mechanism of PM2.5-induced toxicity suggests the role of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) in this process; however, a comprehensive framework to link PM2.5 exposure with COPD remains vacant. The adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework integrates research from different models to achieve a systematic assessment of PM2.5 toxicity in the respiratory system. This review focused on PM2.5-related pathology of COPD at molecular, cellular, organic, individual and population levels using the AOP framework. Combined with our previous studies, the AOP-Wiki website, and other available evidence, we established an AOP framework in which the molecular initiating event is the alteration of ncRNA expression profiles. Subsequently, oxidative stress and activation of the inflammatory pathway induced pulmonary inflammation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, fibroblast proliferation, and myofibroblast differentiation, leading to airway remodeling, pulmonary epithelial cell apoptosis, and emphysema caused by autophagy. These were identified as key events. They collectively contribute to the pathogenesis of COPD by altering the structure and function of the airways and lung tissue, thus exacerbating respiratory symptoms and disease progression. This framework will provide a reference to identify biomarkers of PM2.5 exposure-triggered respiratory diseases.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) remains a major air pollutant and has been identified as the second most significant risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) prevalence in China[1-3]. Epidemiological evidence indicates that PM2.5 exposure is correlated with COPD morbidity[4], and even short-term exposure can increase hospitalizations and mortality related to the disease[5]. Despite progress in elucidating the underlying mechanisms, a comprehensive framework linking PM2.5 exposure to COPD pathology - including lung inflammation, emphysema, and small airway remodeling - remains incomplete. Key challenges include the complexity and diversity of molecular and cellular responses to PM2.5, which involve multiple pathways and targets, as well as the difficulty in integrating epidemiological, in vitro, and in vivo data to connect molecular initiation events with adverse outcomes (AOs). Additionally, the lack of integration between epidemiological, in vitro, and in vivo studies has made it difficult to establish a clear link between molecular initiation events and AOs. This integration is challenging due to: (i) the variability in homology of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) sequences across organisms (e.g., human, rodent, and nematode), making their expression levels difficult to verify at both the human and other model organism levels; (ii) the complexity of PM2.5 components across seasons and regions, which exerts varying effects on ncRNA profiles and leads to a wide array of molecular and cellular responses; (iii) the lack of standardization in ncRNA sequence platforms and analysis processes, making some results incomparable across studies.

To address these gaps, the adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework offers a conceptual tool for organizing and evaluating the evidence linking environmental exposures to adverse health outcomes. First formally proposed in 2010[6], an AOP describes a structured sequence of events beginning with a molecular initiating event (MIE) and progressing through key biological processes to an AO at the individual or population level[7]. Since its introduction, the AOP approach has simplified chemical toxicity assessment, with over 500 AOPs now documented in the AOP-Wiki (https://www.aopwiki.org/). It has been successfully applied in chemical risk assessment - for instance, Da Silva et al. used an AOP to demonstrate how inhaled substances affect lung function via surfactant inhibition[8]. However, an AOP specific to PM2.5-induced COPD has not yet been established.

Many existing AOPs employ MIEs such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation[9] or receptor activation/inhibition[10,11]. However, these early events are often difficult to access or quantify, delaying the detection of AOs following pollutant exposure. In this context, ncRNAs - including microRNAs (miRNAs), long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs)[12] - offer distinct advantages as early biomarkers. Compared to proteins or mRNAs, ncRNAs have several benefits: they are upstream regulators of mRNAs and proteins, meaning they respond earlier in the biological process; they are highly stable in biofluids, tissue-specific, and rapidly responsive to environmental stressors. Additionally, ncRNAs can be quantified using standard techniques such as reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), making them ideal for non-invasive monitoring and early risk assessment[13,14]. These properties position ncRNAs as excellent candidates for early risk detection and non-invasive monitoring.

Therefore, we hypothesize that the alteration of ncRNA expression profiles serves as the crucial MIEs in PM2.5 exposure-induced respiratory toxicity. This review aims to establish a comprehensive AOP framework that systematically links PM2.5 exposure to COPD pathogenesis through ncRNA-mediated key events (KEs), integrating existing literature and our previous studies to identify potential biomarkers and mechanistic insights.

METHODS

Literature review and study selection

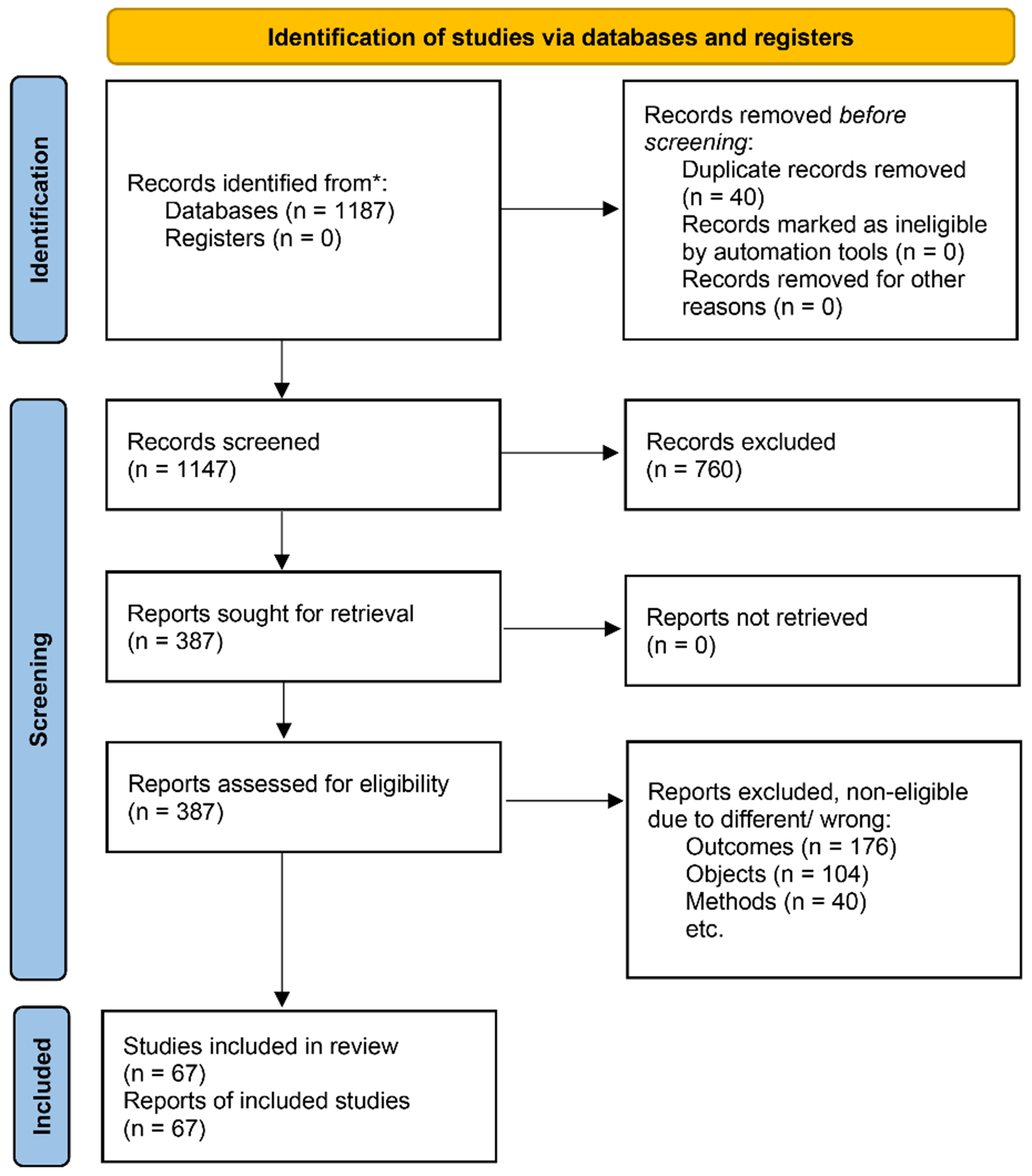

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases up to 2023. The search strategy combined keywords related to (“PM2.5” OR “particulate matter”) AND (“ncRNA” OR “miRNA” OR “lncRNA” OR “circRNA”) AND (“COPD” OR “pulmonary inflammation” OR “airway remodeling” OR “emphysema”). The retrieved articles were screened by title, abstract, and full text for relevance. The literature selection process is detailed in Figure 1.

AOP development and key event relationship evaluation

The AOP framework was constructed based on the OECD guidelines and integrated evidence from in vitro, in vivo, and epidemiological studies. KEs were identified from the literature, and key event relationships (KERs) were evaluated based on the Bradford-Hill considerations (biological plausibility, essentiality, and empirical evidence) as outlined in Table 1. The definitions of key terms and abbreviations used in AOP were shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Summary and evaluation of KERs from the AOP

| Upstream event | Relationship type | Downstream event | Weight of evidence | ||

| Biological plausibility | Essentiality | Empirical evidence | |||

| ncRNA expression profiles alterations | Adjacent | Oxidative stress | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| ncRNA expression profiles alterations | Adjacent | Activation of the inflammatory pathway | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| ncRNA expression profiles alterations | Adjacent | Epithelial mesenchymal transformation | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| ncRNA expression profiles alterations | Adjacent | Fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| ncRNA expression profiles alterations | Adjacent | Cellular apoptosis | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| ncRNA expression profiles alterations | Adjacent | Cellular autophagy | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| Oxidative stress | Adjacent | Pulmonary inflammation | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Activation of the inflammatory pathway | Adjacent | Pulmonary inflammation | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Epithelial mesenchymal transformation | Adjacent | Airway remodeling | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation | Adjacent | Airway remodeling | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Cellular apoptosis | Adjacent | Emphysema | Strong | moderate | Strong |

| Cellular autophagy | Adjacent | Emphysema | Strong | moderate | Strong |

| Pulmonary inflammation | Adjacent | COPD | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Airway remodeling | Adjacent | COPD | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Pulmonary dysfunction | Adjacent | COPD | Strong | Strong | Strong |

MIE TRIGGERED BY PM2.5 EXPOSURE: THE ALTERATION IN ncRNA EXPRESSION PROFILES (KE2007)

With the development of sequencing and bioinformatics technologies, the biological functions of ncRNAs have been gradually elucidated. To date, miRNAs have been proposed to bind the 3’-untranslated region (3’UTR) of messenger RNAs (mRNAs)[15]; lncRNAs and circRNAs act as miRNA sponges to regulate target gene expression[16]. Additionally, lncRNAs and circRNAs can act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) and establish protein-protein interaction networks[17]. ncRNAs are also involved in the epigenetic modification process, such as histone modification[18], and DNA or RNA methylation[19]. These ncRNAs play a crucial role in regulating mammalian gene expression, influencing development, and tissue homeostasis, and contributing to various human diseases[20].

The significance of ncRNAs in the development of COPD upon PM2.5 exposure derives from their role as key regulators of epigenetic reprogramming. Environmental stress, such as PM2.5 exposure, exerts effects on organisms usually through a rapid epigenetic regulation. Numerous studies confirmed that PM2.5 exposure rapidly altered ncRNA expression by modifications at ncRNA gene loci[21,22]. This PM2.5-driven dysregulation of ncRNAs, including miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs, in turn orchestrates changes in the downstream target gene networks. The hallmarks of COPD - persistent inflammation, oxidative stress, and tissue remodeling - are driven by the altered expression of target genes. Thus, the alteration of ncRNA expression represents the critical molecular at early stage of PM2.5 exposure, bridging the gap between PM2.5 exposure and pulmonary pathology, emphasizing their roles as MIEs.

Increasing evidence suggests that ncRNA expression profiles are altered following exposure to environmental stresses, such as air pollutants[23]. These abnormally expressed ncRNAs disrupt homeostasis and participate in pathophysiological processes. Our previous research found that ncRNA expression profiles are altered and act as upstream drivers in PM2.5 exposure-induced injuries[24-27].

Despite the growing evidence, a systematic and causal framework linking specific PM2.5-induced ncRNA alterations to the downstream pathogenesis of COPD is still lacking. This review aims to address this critical gap by constructing an evidence-driven AOP, in which ncRNA dysregulation acts as the MIE.

THE CELLULAR LEVEL: EFFECTS OF PM2.5 EXPOSURE ON BRONCHIAL EPITHELIAL CELLS AND FIBROBLASTS

Key event (KE1392): oxidative stress

Intracellular metabolic processes and certain exogenous chemicals stimulate the production of ROS, which can be cleared by antioxidant enzymes[28]. When the balance between oxidation and antioxidation is disrupted, excessive ROS accumulates, leading to oxidative stress and further accelerating ROS accumulation[29]. Molecular pathways that are closely associated with PM2.5 exposure-induced oxidative stress include the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) - antioxidant response element (ARE) pathway[30-32], nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway[33-35], and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway[29,36].

Oxidative stress following miRNA alteration

miRNAs play a crucial role in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis, which can lead to oxidative damage and the development of diseases[37]. A randomized crossover study has found that miR-144 participated in PM-induced oxidative stress[38].

Multiple animal and cellular studies have further clarified the mechanisms by which oxidative stress is linked to changes in miRNA profiles. At the cellular levels, Eaves et al. found that 33 out of 59 miRNAs differentially expressed in PM2.5-treated human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells were associated with nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)-mediated oxidative stress pathways[39]. PM2.5 exposure was also shown to upregulate miRNAs such as miR-222, miR-210, miR-101, miR-34a, and miR-93, leading to ROS generation in pulmonary cells, while miR-486 downregulation caused oxidative stress in A549 cells[31,40]. Additionally, miR-217-5p reduces PM2.5-induced inflammation and oxidative stress in macrophages, reducing lung injury caused by PM2.5 exposure[41]. PM2.5-induced miR-760 upregulation reduced Heme Oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) expression, increasing ROS generation in human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells[42]. Crucially, experimental overexpression of miR-760 was shown to attenuate ROS generation, providing direct functional evidence of its causal role. At the animal level, Zhao et al. reported increased oxidative stress in rat lung tissues after two months of PM2.5 exposure, suggesting miRNA upregulation and 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 (OGG1) expression as potential mechanisms for PM2.5-induced lung injury[22].

Oxidative stress following lncRNA alteration

Reduced expression of long noncoding-interleukin-7 receptor (lnc-IL7R) in PM2.5-treated cells led to increased oxidative stress, which in turn induced the expression of p16INK4a and p21CIP1/WAF1[43]. This study demonstrated a causal link through knockdown experiments, where reducing lnc-IL7R expression exacerbated oxidative stress markers. Additionally, the upregulation of lncRNA loc146880 further aggravated oxidative stress in A549 cells[44]. In mouse alveolar epithelial cells, lncRNA Nqo1 antisense transcript 1 (Nqo1-AS1) was linked to cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress by stabilizing Nqo1 mRNA[45]. Furthermore, lncRNA metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) acts as a sponge for miR-145, activating Nrf2 protein and contributing to oxidative stress. In contrast, lncRNA Forkhead box D3 antisense RNA1 (FOXD3-AS1) exacerbates oxidative stress in lung epithelial cells by interacting with miRNA-150[46].

Oxidative stress following circRNA alteration

Several studies have shown that upregulation of circRNA expression, either independently or in combination with miRNA alterations, can mediate oxidative stress in cells and contribute to lung inflammation. For example, circ_0008553, hsa_circ_0006872, and circRNA oxysterol binding protein-like 2 (Circ-OSBPL2) mediated oxidative stress in human HBE cells following PM2.5 or smoke exposure[47-49]. CircRNA RNA binding motif single stranded interacting protein 1 (Circ-RBMS1) plays a crucial role in PM2.5-induced oxidative stress by targeting miR-197-3p and silencing circ-RBMS1 worsened oxidative stress by lowering superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels and increasing malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in HBE cells[50]. This interaction was validated functionally, as silencing circ-RBMS1 worsened oxidative stress, an effect that could be rescued by a miR-197-3p inhibitor.

In summary, PM2.5-induced alterations in ncRNAs disrupt redox homeostasis by altering key gene expression on antioxidant signaling pathways, most notably the Nrf2-ARE axis. The experimental evidence from gain- and loss-of-function studies strongly supports a causal role for specific miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs in regulating oxidative stress.

Key event (KE2009): activation of inflammatory pathway

Numerous studies have shown that PM2.5 exposure is positively correlated with the activation of inflammatory pathways. The endpoints of activated inflammatory pathways were excessive expression of inflammatory cytokines[26,51]. With the in-depth study, ncRNAs have been proven to facilitate or inhibit some inflammatory pathway activation following PM2.5 exposure, such as the NF-κB pathway.

Inflammatory pathway activation related to miRNAs

Solid epidemiological evidence supports that miRNA alterations contribute to lung inflammation[26,51]. For example, a randomized crossover study suggested that five miRNAs were down-regulated in young healthy adults, which modulated inflammatory cytokine expression[52]. On the contrary, studies found increased expression levels of let-7a, miR-146a-5p, and miR-155-5p in children[53], and miR-223-3p, miR-199a/b in older individuals[54], which were associated with an inflammatory response.

In laboratory studies, miR-466i-5p, miR-203-5p, and miR-7a-5p were correlated with inflammatory pathways in PM2.5-exposed mice using mRNA and miRNA sequencing analysis[55]. Additionally, miR-29b-3p was highly expressed in PM2.5-exposed HBE cells, promoting pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by inhibiting the AMPK pathway[56]. Furthermore, exposure to secondary organic aerosol (SOA), a key component of PM2.5, altered the expression of 31 miRNAs in BEAS-2B cells, with some involved in inflammation pathogenesis[39].

Our studies identified several miRNAs associated with inflammatory pathway activation and explored potential mechanisms at both animal and cellular levels[26,27]. We found that in PM2.5-induced lung inflammation, miR-297 inhibited NF-κB activating protein (NKAP) expression in a dose-dependent manner, promoting Notch pathway activation and the secretion of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)[26,27]. Overexpression of miR-382-5p in mice significantly inhibited C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) and matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) expression induced by PM2.5, alleviating inflammatory symptoms in lung tissue[27]. In summary, both epidemiological and animal evidence indicate that PM2.5 exposure leads to dysregulation of miRNAs linked to lung inflammation.

Inflammatory pathway activation related to lncRNAs

Traffic-related PM2.5 exposure enhanced the expression of lncRNA RP11-86H7.1, NF-κB pathway activation, and the secretion of inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α) as a ceRNA of miR-9-5p in HBE cells[57]. lncRNA uc001.dgp.1 played a role in PM2.5-induced inflammatory responses in BEAS-2B cells[58].

In animal models, PM2.5 intra-tracheal instillation resulted in 885 differentially expressed lncRNAs in murine lung tissues, with three lncRNAs associated with NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome upregulation and inflammation development[59]. High-throughput sequencing suggested that PM2.5 increased the expression of lncRNA AABR07005593.1, which regulated IL-6 secretion to promote pulmonary inflammation in rats[60].

Inflammatory pathway activation related to circRNAs

Several studies have observed that altered circRNA expression levels, in combination with miRNAs or lncRNAs, may trigger the secretion of immune factors and contribute to pulmonary inflammation pathogenesis. Decreased levels of circRNA CBT15_circR_1011 and mm9_circ_005915 were found in PM2.5 intra-tracheal instillation mouse models, which regulated inflammatory factor expression and participated in pulmonary inflammation[59].

Using human HBE cells, circ-RBMS1/miR-197-3p/F-box protein 11 (FBXO11) axis mediated IL-1β and TNF-α secretion, promoting PM2.5-triggered inflammation[50]; circ_406961 interacts with ILF2 protein, modulating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)/JNK pathway activation and participating in PM-induced inflammation[61]; long-term PM2.5 exposure induced circRNA104250 and lncRNA uc001.dgp.1, which acted as ceRNA for miR-3607-5p and regulated NF-κB pathway activation via the miR-3607-5p-IL1R1 axis[58]; circ-OSBPL2 facilitated IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α expression via miR-193a-5p/bromodomain protein 4 (BRD4) signaling, contributing to smoke-induced inflammation[48].

In summary, ncRNAs participated in inflammatory pathway activation, leading to the secretion of inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines can recruit macrophages and other immune cells, triggering a local inflammatory response that ultimately contributes to the development of pulmonary inflammation.

Key event (KE1650): epithelial-mesenchymal transformation

Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) is a transformation process of epithelial to mesenchymal cells[62] and plays an essential role in ontogeny, tissue healing, organ fibrosis, and carcinogenesis[63]. In recent years, studies suggested that EMT plays an important role in the increased incidence of respiratory diseases[64,65]. ncRNAs have been proven to participate in EMT by regulating associated gene expressions[66,67].

miRNA expressions and EMT

Most laboratory studies revealed that PM2.5 exposure decreased several miRNA expression levels and promoted EMT development. Vimentin expression was upregulated in human lung cancer cells treated with PM2.5, regulated by miR-125a-3p, which plays a crucial role in the EMT process[68]. Chronic PM2.5 exposure decreased miR-139-5p expression, regulated Notch1 pathway activation, and contributed to EMT in HBE cells[69]. miR-122 regulated Notch pathway activation, promoting EMT development in A549 cells[70]. Decreased miR-26a expression promoted EMT and enhanced the invasion capacity of PM2.5-exposed A549 cells via the Lin-28 Homolog B (LIN28B)/IL-6/STAT3 axis[71].

lncRNA expressions and EMT

A study using PM2.5-exposed HBE cells confirmed increased lncRNA MALAT1 expression, promoting the EMT process through the ceRNA mechanism[72]. Besides ceRNAs, studies also showed that lncRNAs directly increased EMT-associated gene expressions. For instance, lncRNA loc146880 participated in PM2.5-induced EMT by up-regulating e-cadherin and vimentin expression in A549 cells[44]. lncRNA loc107985872 was induced in PM2.5 organic extract-treated A549 cells, increasing e-cadherin, n-cadherin, and vimentin expression via the Notch1 pathway, promoting tumor progression[66]. lncRNA Gm16410 plays a crucial role in the EMT process of pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells via the TGF-β1/SMAD family member 3 (Smad3)/Phospho SMAD family member 3 (p-Smad3) pathway[73]. Our research revealed that upregulation of lncRNA SRY-box transcription factor 2 overlapping transcript (SOX2-OT) significantly increased EGFR mRNA and protein levels, further promoting EMT after long-term PM2.5 exposure[24].

circRNA expression and EMT

To date, no circRNAs have been reported to mediate the PM2.5-induced EMT process. However, circRNAs do play a role in the EMT of pulmonary cells following exposure to environmental particles/aerosols. For example, elevated levels of e-cadherin, n-cadherin, and vimentin were positively associated with circ0061052 expression in cigarette smoke extract (CSE)-treated HBE cells. circ0061052 also plays a role in cigarette smoke-induced EMT and airway remodeling in COPD by regulating miR-515-5p through a forkhead box C1 (FoxC1)/Snail regulatory axis[74]. Hsa_circ_0058493 was highly expressed in silicosis patients, validated in medical research council cell strain-5 (MRC-5) cell models, involved in EMT, and influenced fibrotic molecule expression[75].

Taken together, ncRNAs were involved in EMT pathway activation and facilitated the expression of EMT-related proteins (e-cadherin, n-cadherin, and vimentin). Airway epithelial cells gradually transform into interstitial cells, causing excess mucus production and basement membrane thickening, finally leading to airway remodeling.

Key event (KE1500): fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation

Research has confirmed that long-term PM2.5 exposure triggered fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation, which eventually aggravated pulmonary fibrosis and airway remodeling[76]. In this section, we only discuss relevant miRNAs and lncRNAs because there are no reports about circRNAs.

Fibroblast proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation and miRNAs

Studies on miRNA expressions and pulmonary fibrosis found that the upregulation of miRNAs, such as miR-503[77], miR-29b[78], miRNA-34c-5p[79], and miR-125a-5p[80] in silica-induced mouse models significantly decreased α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), collagen 1, collagen 3, and extracellular matrix synthesis, reducing fibroblast migration and alleviating pulmonary fibrosis. For PM2.5 exposure, direct evidence of miRNA-associated fibrosis is limited; only miRNA-126[81] expression in circulation has been reported to be significantly inhibited following PM2.5 exposure. These findings emphasize the role of miRNAs in regulating PM2.5-induced pulmonary fibrosis.

Fibroblast proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation and lncRNAs

Similar to miRNAs, evidence of lncRNA-mediated pulmonary fibrosis has been collected from silicosis studies. lncRNA plasmacytomvariant translocation 1 (PVT1) was induced in PM2.5-exposed pulmonary cells and is recognized for promoting fibroblast proliferation and migration by acting as a ceRNA for miR-497-5p in mice lung tissue[82]. lncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 (SNHG1) was highly expressed in pulmonary fibrosis mouse models triggered by silica, where it combined with miR-326 to regulate the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition[83]. In addition, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 941 (LINC00941)/inhibit autophagy in pulmonary fibrogenesis (lncIAPF) accelerates pulmonary fibrosis by promoting fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation and myofibroblast proliferation and migration[84].

While the relationship between ncRNAs and PM2.5-induced fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation requires further exploration, silica, a major toxic component of PM2.5[85], strongly suggests that aberrant ncRNA expression can promote abnormal collagen fiber deposition and smooth muscle hypertrophy, fundamental pathological features of pulmonary fibrosis.

Key event (KE1262): cellular apoptosis

Available evidence suggested that PM2.5 inhalation caused cellular apoptosis[86], and an epigenetic study has shown that ncRNAs play a role in the pathogenesis of apoptosis caused by PM2.5 exposure.

Cellular apoptosis and miRNAs

Several in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that PM2.5 exposure downregulates miRNAs such as miR-486 and miR-194-3p[87], increasing apoptosis in A549 cells, bronchial epithelium cells[40], BEAS-2B cells[88], and HBE cells[42]. PM2.5 exposure also decreases let-7a expression, exacerbating cell apoptosis via the let-7a/Arginase 2 (ARG2) axis in BEAS-2B cells[88]. Heme-oxygenase 1 has been shown to protect cells from PM2.5-induced toxicity, with hsa-miR-760 upregulating Heme-oxygenase 1 and reducing apoptosis in HBE cells[42].

Our previous study demonstrated that PM2.5 treatment causes apoptosis through mitochondrial dysfunction in A549 cells, and miRNA microarray analysis revealed downregulation of miR-1228-5p, correlated with PM2.5-induced apoptosis[89]. We also found that miR-802 and miR-382-5p are associated with PM2.5-triggered cell apoptosis[27,90].

Cellular apoptosis and lncRNAs or circRNAs

Altered expression of lncRNA maternally expressed 3 (MEG3) in PM2.5-exposed pulmonary cells has been extensively reported. For instance, traffic-related PM2.5 treatment induced lncRNA MEG3, which inhibits apoptosis significantly through interaction with miR-149-3p via the NF-κB pathway[91]. lncRNA Sox2-OT was associated with PM2.5-induced mitochondria damage and apoptosis in A549 cells[92]. Additionally, lncRNA LINC00341 and lung cancer associated transcript 1 (LUCAT1) were upregulated in PM2.5-treated bronchial cells, promoting apoptosis[93,94]. Our study found that the expression level of lncRNA taurine up-regulated 1 (TUG1) was increased after PM exposure as ceRNA of miR-222-3p, mediated apoptosis, and ultimately caused airway hyper-reactivity[24].

One circRNA, circ_0038467, has been identified to promote cellular apoptosis in lung cells following PM2.5 exposure and acts as a sponge for miR-138-1-3p[95]. Apoptosis in PM2.5-exposed pulmonary cells is frequently linked to ncRNA dysregulation. miRNAs (e.g., miR-486), lncRNAs (e.g., MEG3), and circRNAs regulate apoptosis-related genes (e.g., caspase-3) directly or via ceRNA networks.

Key event (KE1945): cellular autophagy

Autophagy is a process by which cells degrade and recycle damaged or excess materials through lysosomes to maintain homeostasis in mammal cells. Our study reported that PM2.5 exposure dysregulated the process of autophagy and eventually contributed to the pathogenesis of COPD[96]. Autophagy-related genes, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF1A), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A), Bcl-2 associated athanogene 3 (BAG3), rythroblastic oncogene B (ERBB2), and autophagy related protein 16 like 1 (ATG16L1) may contribute to COPD pathogenesis and aid in developing targeted treatments[97-99]. Studies found that ncRNAs are correlated with the autophagy process in lung cells[100] and mouse models[101]. In this section, we only discuss relevant miRNAs and lncRNAs because circRNAs have not been reported yet.

Autophagy and miRNAs

Sufficient evidence from animal experiments to population studies has demonstrated that miRNA expression is widely involved in cellular autophagy processes. Quezada-Maldonado et al. observed 45 down-regulated miRNAs that influenced cell autophagy and cell cycle in lung epithelial cells exposed to PM2.5[102]. MiR-146a-5p was upregulated after PM2.5 exposure, modulating the expression of target genes interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), ultimately affecting cellular autophagy[103]. Our previous study also identified increased miR-4516 expression in A549 cells treated with PM2.5, which regulated the autophagy process[104]. In animal models, miR-338-3p acts as an autophagy inhibitor in rats of allergic rhinitis exacerbated by PM2.5 by directly targeting ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 Q1 (UBE2Q1) and affecting the protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (AKT/mTOR) pathway[105].

Autophagy and lncRNAs

Many studies focused on the mechanism underlying lncRNA-regulated autophagy in pulmonary cells upon PM2.5 exposure. lncRNA loc146880 increased autophagy in PM2.5-exposed A549 cells by promoting ROS generation[44]. LINC00987 and MIR155HG acted as ceRNA for Let-7b-5p and miR-218-5p, respectively, to modulate the autophagy process in lungs with COPD-like lesions[106,107]. lncRNA MEG3 participated in HBE cell autophagy by directly down-regulating the expression of autophagy-related biomarkers[108].

Overall, ncRNAs are involved in regulating cellular autophagy via multiple autophagy pathways, where autophagy biomarkers are evaluated, further activating lysosomal activity, and inducing HBE cell autophagy. These studies also provided new therapeutic targets for COPD patients.

THE ORGAN/TISSUE LEVELS: PM2.5 AND PULMONARY INJURIES

Key event (KE 2010): PM2.5 and pulmonary inflammation

Pulmonary inflammation is the body’s defensive response to inhaled exogenous stimulation[109]. In this process, airway epithelial cells secrete inflammatory cytokines, which recruit inflammatory cells and induce mucus secretion[110]. Persistent acute inflammation can develop into chronic inflammation, exacerbating pulmonary inflammation, a major characteristic of COPD[111]. The recruitment level of inflammatory cells can be evaluated by inflammatory cell counts in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Increased numbers of inflammatory cells, including leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and secreted cytokines, were observed in BALF from mice exposed to PM2.5[112,113], indicating adverse pulmonary effects of PM2.5 exposure.

Alterations of miRNA expression and pulmonary inflammation

In-depth studies have explored the roles of miRNA expression and potential molecular mechanisms in the pathogenic process of pulmonary inflammation and immune response regulation. Prominent pulmonary inflammation was observed in mice exposed to PM2.5, with miRNA-seq analysis revealing that differentially expressed miRNAs were associated with B cell receptor signaling, promoting the development of pulmonary inflammation[55]. miRNAs also facilitate immune cell infiltration in the lungs; for instance, miRNA-149-5p is linked to macrophage, neutrophil, and lymphocyte infiltration in PM2.5-exposed mice[114]. Neutrophil infiltration has been associated with increased let-7 or decreased miR-6747-5p expression in lungs exposed to PM2.5[115,116]. We also observed inflammatory infiltration around PM2.5 deposition, obvious pulmonary hemorrhage, and significantly increased pathological score in murine lungs; however, overexpression of miR-382-5p inhibited CXCL12 and alleviated these inflammatory symptoms[27].

Alterations of lncRNA expression and pulmonary inflammation

Many studies have linked induced cytokine levels, especially IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, and IL-1β in PM2.5-exposed pulmonary cells, to altered lncRNA expression. For example, increased expression of lncRNA RP11‑86H7.1 in HBE cells[117], lncRNA AABR07005593.1 in rat lungs[60], and decreased lncRNA Gm16410 were associated with immune cell infiltration and increased cytokine secretion. lncRNA TUG1 was highly expressed in PM2.5-treated fibroblasts, enhancing the expression of IL-6 and TGF-β1, thereby exacerbating pulmonary inflammation[118]; meanwhile, in PM2.5-exposed murine lungs, lncRNA TUG1 aggravated inflammation infiltration as a sponge for miRNA-181b[119].

Alterations of circRNA expression and pulmonary inflammation

Several studies have found that circBbs9 in mouse lung tissue can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome after exposure to PM2.5[59,120]. PM2.5 treatment enhanced lymphocyte adhesion, with circRNA 406961 linked to the activation of STAT3/JNK pathways, regulating inflammatory responses[61]. Besides, thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) and circRNA 104250 promoted the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-8, in human HBE cells, contributing to PM-induced inflammation[58,121].

Overall, airway inflammation is a key characteristic of COPD, often accompanied by the infiltration of neutrophils, macrophages, B lymphocytes, and T lymphocytes, which are recruited by inflammatory cytokines regulated by ncRNAs.

Key event (KE2013): PM2.5 and airway remodeling

With the worsening of chronic airway inflammation, basement membrane thickening, glandular hypertrophy, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and other pathological changes in the airway epithelium are defined as airway remodeling[122]. In recent years, the pathogenesis of airway remodeling has been gradually clarified, with ncRNAs playing an indispensable role in this process, such as miR-192-5p[123]. Additionally, exogenous chemicals also induced airway remodeling via altered levels of ncRNA expression.

Alterations of miRNA expression and airway remodeling

A population study showed that biomass combustion-produced PM upregulated miR-34a levels in the serum of COPD patients, which were involved in airway remodeling[124]. Animal experiments revealed that PM2.5 exposure could aggravate collagen deposition and inflammation in asthma mice and promote airway remodeling in mouse models by downregulating miR-224, miR-155, or miR-21 levels[125-127].

Alterations of lncRNA expression and airway remodeling

As mentioned above, lncRNA TUG1 has been associated with massive biological processes and cellular phenotypes in response to PM2.5 exposure. As for airway remodeling, lncRNA TUG1 knockdown alleviated airway remodeling in CSE-exposed mice by inhibiting collagen deposition[118]. Similarly, lncRNA TUG1 participated in the underlying mechanism of airway remodeling as a target for miRNA-181b in asthmatic mice[119]. Our previous study also found that PM2.5 exposure induced the upregulation of lncRNA TUG1 in vivo and in vitro, which led to airway hyperactivity by the TUG1/mir-222-3p/CELF1/p53 network[25]. Therefore, the upregulation of lncRNA TUG1 contributes to pathological processes in airway remodeling.

Alterations of circRNA expression and airway remodeling

Till now, direct evidence showing that circRNA plays a role in PM2.5 exposure resulting in airway remodeling remains insufficient. Studies on environmental stressors such as cigarette smoke have linked circ0061052, circRNA casein kinase 1 epsilon (circ_CSNK1E), Circ-Osbpl2, circRNA ankyrin repeat domain (ANKRD) 11 (circANKRD11), and Circ-RBMS1 to airway remodeling; however, the expression of these circRNAs in pulmonary cells or lung tissues following PM2.5 exposure requires further validation[48,50,74,128,129].

Key event (KE2011): PM2.5 and emphysema

Emphysema is characterized by lung parenchymal damage and airflow limitation, which can be diagnosed through computed tomography (CT) imaging and pulmonary function (PF) tests. In a cohort study conducted in the USA, long-term PM2.5 exposure was correlated with increased morbidity of emphysema[130]. Here, we discuss the mechanism underlying ncRNAs in the process of emphysema induced by PM2.5 exposure.

Alterations of miRNA expression and emphysema

At individual level, Cong et al. reported that miR-644 levels in peripheral blood were associated with personal PM2.5 exposure levels, during which the PF was decreased[131]. A pilot study of young healthy adults exposed to PM2.5 indicated that decreased circulating miR-194-3p levels were statistically correlated with reduced PF, suggesting a role of miR-194-3p in PM2.5 exposure-associated COPD[40]. In a PM2.5-exposed cellular model, decreased miR-194-3p was shown to enhance death associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) expression and caspase 3 activities, promoting pulmonary cell apoptosis[87]. An animal study found that miR-146a expression levels influenced lung function indexes in mice, with micro-CT images showing lung tissue shrinkage and increased density after PM2.5 exposure[132].

Alterations of lncRNA expression and emphysema

Population-level studies have shown that PM2.5 exposure is associated with decreased levels of lnc-IL7R and the aggravation of emphysema in COPD patients[133]. In addition, lncRNA plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 (PVT1) and nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) are novel biomarkers to evaluate emphysema exacerbation risk in COPD patients[134,135]. Low expression levels of lnc-IL7R during PM2.5 exposure led to the aggravation of emphysema in COPD patients[133]. These studies all suggest potential roles in regulating emphysema. Beyond population studies, lncRNA major histocompatibility complex molecules (MHC)-R was upregulated in lung tissue from PM2.5-exposed mice, showing damage to lung parenchyma, distal alveolar enlargement, and pulmonary dysfunction[136].

Alterations of circRNA expression and emphysema

No studies have yet focused on circRNA, PM2.5, and emphysema. However, it is well-known that increased apoptosis in airway cells is a major cause of emphysema; theoretically, the miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs associated with apoptosis, as mentioned above, could potentially contribute to emphysema development during PM2.5 exposure.

To summarize, PM2.5-induced cellular changes gradually accumulate until they surpass the host’s compensatory mechanisms, leading to tissue/organ-level damage (pulmonary inflammation, airway remodeling, and emphysema), which are hallmarks of COPD. Given the role of ncRNAs in pulmonary changes, we believe that ncRNAs are key regulators of PM2.5-induced pulmonary injuries.

Adverse outcome (AO2008): COPD

COPD is a chronic bronchitis or emphysema characterized by airflow obstruction[137]. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) in 2022 pointed out that COPD is one of the top three causes of death in the world today. Ninety percent of the deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, which has become the main economic burden of chronic diseases in the future[138]. A national cross-sectional study reported that exposure to an annual mean PM2.5 of 50 μg/m3 or higher ranked as the second risk factor for COPD prevalence in China[1]. Prevention and early detection of COPD should be a public health priority in China to reduce COPD-related morbidity and mortality, which relies heavily on understanding underlying mechanisms and discovering novel biomarkers. Specific ncRNA expressions have been reported in response to PM2.5-induced lung diseases, with their circulating levels often reflecting changes in their pulmonary counterparts. Therefore, ncRNAs are sensitive, predictive, accessible, and quantifiable indicators of disease. This summary highlights potential ncRNAs linking PM2.5 exposure to COPD hallmarks, aiding in the understanding of the AOP of PM2.5-induced COPD with alterations in ncRNAs such as MIE.

As shown in Figure 2, the AOP framework describes the development of COPD triggered by PM2.5 exposure. Alterations in ncRNA expressions are identified as the MIE, which triggers downstream signal pathway activation at cellular levels and pathological changes at the organ/tissue level, eventually resulting in the development of COPD at the individual /population level. The summary of MIE, KEs, and AO is listed in Table 2. The KERs, evaluated based on Bradford-Hill’s weight of evidence considerations, are shown in Table 1[139]. Tables 3-5 show the roles of ncRNAs in regulating KEs of PM2.5-induced respiratory toxicity and how PM2.5-altered ncRNAs target specific pathways or genes to contribute to the development of COPD. The detailed information of supportive evidence of KERs was summarized in Supplementary Tables 2-5. Each event will be elaborated in detail in the subsequent sections.

Figure 2. AOP diagram related to PM2.5 exposure-triggered respiratory toxicity. AOP: Adverse outcome pathway; PM2.5: fine particulate matter; miRNA: microRNA; lncRNA: long non-coding RNA; circRNA: circular RNA; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Summary of the AOP

| Sequence | Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

| 1 | MIE | 2007 | ncRNA expression profiles alterations | ncRNA expression alteration |

| 2 | KE | 1392 | Oxidative stress | Oxidative stress |

| 3 | KE | 2009 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Inflammation |

| 4 | KE | 1650 | Epithelial mesenchymal transformation | EMT |

| 5 | KE | 2012 | Fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation | Fibrosis |

| 6 | KE | 1262 | Cellular apoptosis | Apoptosis |

| 7 | KE | 1945 | Cellular autophagy | Autophagy |

| 8 | KE | 2010 | Pulmonary inflammation | Pulmonary inflammation |

| 9 | KE | 2013 | Airway remodeling | Airway remodeling |

| 10 | KE | 2011 | Emphysema | Emphysema |

| 11 | AO | 2008 | COPD | COPD |

Overview of miRNAs involved in respiratory toxicity: expression profiles, target pathways, and associated respiratory toxicity types

| Name | Cellular KE | Tissue KE | Expression | Target pathway/gene | Respiratory toxicity | Ref. |

| miR-140-5p | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway | Airway inflammation | [140] |

| miR-644 | Cellular apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | GAPDH, β-actin | Pulmonary inflammation | [131] |

| miR-135b | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | Adamts9, Bmper, Klf4, Cxcl12, and Rrbp1 | Pulmonary inflammation | [141] |

| miR-217-5p | Fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-217-5p/PTEN axis | Airway inflammation | [142] |

| miR-181a-2-3p | Cellular apoptosis | Pulmonary inflammation | Downregulated | MEG3 | Pulmonary inflammation | [143] |

| miR-195 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | PHLPP2, Akt signaling | Pulmonary inflammation | [144] |

| miR-338-5p | Fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | HIF-1α/Fhl-1 pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | [145] |

| miR-21 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | SATB1/S100A9/NF-κB axis | Airway inflammation | [146,147] |

| STAT3 | [148] | |||||

| miR-222-3p | Cellular apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | TUG1/miR-222-3p/CELF1/p53 network | Airway inflammation | [25] |

| miR-155 | Oxidative stress | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | miR-155/FOXO3a signaling pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | [127] |

| miR-29a-3p | Cellular autophagy | Pulmonary inflammation | Downregulated | Akt3/mTOR pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | [149] |

| miR-1228-5p | Cellular apoptosis | Pulmonary inflammation | Downregulated | NOL3 | Pulmonary inflammation | [89] |

| miR-6747e5p | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | NF-κB2 | Airway inflammation | [116] |

| miR-146a | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | NF-κB signaling pathway | Airway inflammation | [147,150] |

| let-7c | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | IL-6/STAT3 pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | [151] |

| miR-1246 | Cellular apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | NFAT1c | Airway inflammation | [152] |

| miR-34c-5p | Cellular apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | Fra-1 | Airway inflammation | [79] |

| miR-146a-5p | Cellular autophagy | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | IL-8, IRAK1 and TRAF6 | Pulmonary inflammation | [103] |

| miR-6515-5p | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, CSF3 | Pulmonary inflammation | [153] |

| miR-21-5p | Fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | Smad7 | Pulmonary inflammation | [154] |

| miR-212-5p | Cellular apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | ARAF, MEK/ERK signaling pathway | Airway inflammation | [155] |

| miR-93 | Cellular apoptosis | emphysema | Upregulated | DUSP2 | Pulmonary inflammation | [156] |

| miR-218 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Downregulated | TNFR1 | Airway inflammation | [157] |

| miR-297 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | NKAP | Pulmonary inflammation | [26] |

| miR-382-5p | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | CXCL12 | Pulmonary inflammation | [27] |

| miR-96 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Downregulated | FOXO3a | Pulmonary inflammation | [158] |

| miR-194-3p | Cellular apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | DAPK1 | Pulmonary inflammation | [40,87] |

| miR-150-5p | Oxidative stress | Pulmonary inflammation | Downregulated | IRE1α | Pulmonary inflammation | [159] |

| miR-22 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Emphysema | Upregulated | miR-22-HDAC4-DLCO axis | Pulmonary inflammation | [160] |

| miR-223 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [161] | |

| miR-143 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | Airway inflammation | [161] | |

| miR-145 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | Airway inflammation | [161] | |

| miR-199a | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | Airway inflammation | [161] | |

| miR-27a | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [162] | |

| let-7e | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | Airway inflammation | [162] | |

| let-7g | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | Airway inflammation | [162] | |

| miR-139 | Oxidative stress | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [163] | |

| miR-340 | Oxidative stress | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [163] | |

| miR-513a-5p | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [164] | ||

| miR-494 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [164] | ||

| miR-923 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [164] | ||

| miR-96 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Downregulated | Airway inflammation | [164] | ||

| miR-223-5p | Upregulated | [40] | ||||

| miR-495-3p | Upregulated | [40] |

Overview of circRNAs involved in respiratory toxicity: expression profiles, target pathways, and associated respiratory toxicity types

| Name | Cellular KE | Tissue KE | Expression | Target pathway/gene | Respiratory toxicity | Ref. |

| circ_406961 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | STAT3/JNK pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | [61] |

| circ_0008672 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Downregulated | circ_0008672/miR-1265/MAPK1 axis | Pulmonary inflammation | [165] |

| circ_0002854 | Cellular apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | MAPK signaling pathway | Airway inflammation | [166] |

| circ_0000157 | Oxidative stress | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-149-5p/BRD4 pathway | Airway inflammation | [167] |

| circ_0006872 | Cellular apoptosis | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | miR-145-5p/NF-κB pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | [49] |

| circ_0026344 | Cellular autophagy and apoptosis | Emphysema | Downregulated | miR-21, PTEN/ERK axis | Pulmonary inflammation | [57] |

| circ_002906 | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | SEPT10 | Airway inflammation | [168] | |

| circ_kif26b | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | miR-346-3p/p21 | Pulmonary inflammation | [169] |

| circ_104250 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-3607-5p | Airway inflammation | [58] |

| circ_0008553 | Oxidative stress | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [47] | |

| circ_1011 | Downregulated | Pulmonary inflammation | [59] | |||

| circ_005915 | Downregulated | Pulmonary inflammation | [59] | |||

| circBBS9 | Cellular apoptosis | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | miR-103a-3p/BCL2L13 axis | Pulmonary inflammation | [170] |

| Activation of inflammatory pathway | circBbs9-miR-30e-5p-Adar axis | [120] | ||||

| circRBMS1 | Cellular apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-197-3p/FBXO11 axis | Airway inflammation | [50] |

| circOSBPL2 | Cellular apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-193a-5p/BRD4 axis | Airway inflammation | [48] |

| circHACE1 | Cellular apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-485-3p | Airway inflammation | [171] |

| circFOXO3 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | miR-214-3p | Pulmonary inflammation | [172] |

Overview of lncRNAs involved in respiratory toxicity: expression profiles, target pathways, and associated respiratory toxicity types

| Name | Cellular KE | Tissue KE | Expression | Target pathway/gene | Respiratory toxicity | Ref. |

| lncRNA MIR155HG | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-128-5p/BRD4 axis | Airway inflammation | [107,173] |

| lncRNA MEG3 | Cellular autophagy and apoptosis | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | p53 | Airway inflammation | [108] |

| Cellular apoptosis and inflammation | miR-218 | [174] | ||||

| lncRNA AABR07005593.1 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | MCCC1 | Airway inflammation | [60] |

| lncRNA MALAT1 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-204/ZEB1 pathway | Airway inflammation | [72] |

| lncRNA NEAT1 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | miR-193a | Pulmonary inflammation | [134] |

| lncRNA SNHG4 | Cellular apoptosis and inflammation | Airway remodeling | Downregulated | miR-144-3p/EZH2 axis | Airway inflammation | [175] |

| lncRNA LOC101927514 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | STAT3 | Airway inflammation | [176] |

| lncRNA Gm16410 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | Downregulated | PI3K/AKT signaling pathway | Pulmonary inflammation | [73] |

| lncRNA RP11-86H7.1 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | NFκB1 | Airway inflammation | [57] |

| lncRNA uc001.dgp.1 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | miR-3607-5p | Airway inflammation | [58] |

| lncRNA MHC-R | Cellular apoptosis | Pulmonary inflammation | Upregulated | Pulmonary inflammation | [136] | |

| n405968 | Activation of inflammatory pathway | Airway remodeling | Upregulated | Airway inflammation | [177] |

miRNA expression in the pathogenesis of COPD

Though many miRNAs have been associated with PM2.5 exposure-induced COPD or the pathological alterations of COPD, it is notable that increased expression of miRNA let-7a, miR-199a-5p, miR-21, or decreased expression of miR-224 and miR-194-3p are consistently associated with COPD in cellular, animal models, or individuals exposed to PM2.5, which have been validated in multi-studies.

lncRNA and circRNA expression alteration in the pathogenesis of COPD

As for lncRNA, increased expression of SOX2-OT, TUG1, PVT1, NEAT1, MALAT1, and MEG3 has been consistently associated with COPD in cellular, animal models, and individuals following PM2.5 exposure. However, all these lncRNAs are intensively investigated in many biological processes, such as cancers. While several studies have explored the role of circRNAs in response to PM2.5-induced COPD, the evidence is insufficient to identify specific molecules as biomarkers. Up to now, many studies have already constructed disease prediction or prognosis models by using ncRNA clusters. For example, such models have been developed for diseases such as lung adenocarcinoma[178], cardiovascular disease[179], and ovarian cancer[180]. We thus proposed that a cluster of ncRNAs, but not single ncRNAs, should be combined to predict the development of COPD upon PM2.5 exposure.

Patients with different COPD grades may exhibit distinct ncRNA expression profiles and downstream KEs, which can influence treatment strategies. For example, mild COPD (GOLD stages 1 and 2) may show early alterations in ncRNA expression that contribute to oxidative stress and inflammation, while moderate to severe COPD (GOLD stages 3 and 4) may involve more extensive changes, such as EMT, fibroblast proliferation, and myofibroblast differentiation, leading to airway remodeling and emphysema. By integrating COPD grading into our AOP framework, we aim to provide a more comprehensive view of the disease’s impact on patient care and public health strategies. This will help in the identification of stage-specific biomarkers and therapeutic targets, thereby improving the prevention and management of COPD, especially in areas with high PM2.5 exposure.

Suggested as functional and applicable biomarkers, a single ncRNA or a cluster of ncRNAs could be used to predict the development or aggravation of COPD. For example, the accuracy of hsa_circ_0005045 is around 70% to predict the aggravation of COPD upon PM2.5 exposure, combined with other characteristics (group of COPD, smoking, and age)[181]. For further clinical application, more studies should focus on the application of ncRNA panels to predict PM2.5 exposure-related COPD at the individual level. When combined with clinical parameters, their predictive accuracy is expected to be higher than that of the existing biomarkers. This validation is the essential next step towards translating mechanistic work into a clinically applicable strategy for prediction and personalized management of PM2.5-induced COPD.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study presents a comprehensive AOP framework that integrates current knowledge on PM2.5-induced COPD, with a unique focus on ncRNAs as the central MIE. A key strength is the integration of multi-level evidence from cellular, animal, and individual studies, evaluated using structured Bradford-Hill criteria. However, several limitations should be considered. Firstly, the majority of mechanistic evidence derives from in vitro or in vivo models, and the extrapolation to human pathophysiology may be limited by interspecies differences. Secondly, PM2.5 composition is highly variable geographically; ncRNA responses may differ depending on the toxic components, of which our framework does not fully discuss. Thirdly, while we propose numerous ncRNA-disease links, many are based on correlation rather than direct causal evidence from gain- or loss-of-function models. Future research should prioritize validating these pathways in human-relevant cohort studies.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this review establishes an AOP framework for PM2.5-induced respiratory toxicity, positioning the alteration of ncRNA expression profiles as the MIE. By integrating evidence from molecular, cellular, tissue, and population levels, we delineate a cascade of KEs - from cellular levels to tissue levels. This framework not only provides a mechanistic understanding of PM2.5 pathogenesis but also highlights a panel of ncRNAs as promising biomarkers for risk prediction. Future efforts to validate this AOP, through human studies and multi-ncRNA biomarker panels, will be crucial for translating these findings into public health strategies aimed at mitigating the burden of air pollution-related COPD.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The Graphical Abstract was created with BioRender.com [Created in BioRender. yibo, w. (2025) https://BioRender.com/badx42d].

Authors’ contributions

Qing Li: Writing - original draft: Li, Q.; Cui, J.

Methodology: Wang, J.

Writing - review and editing: Li, B.

Review and Editing: Relucenti, M.

Conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources: Li, X.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3708303), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82574129), and the High-level Talent in Public Health of Beijing (Discipline Leaders-03-29). Additionally, the Ateneo Sapienza 2021 funds (RM12117A860638CE) contributed to the study. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Wang, N.; Cong, S.; Fan, J.; et al. Geographical disparity and associated factors of COPD prevalence in China: a spatial analysis of national cross-sectional study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2020, 15, 367-77.

2. Peng, Z.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, S.; et al. PM2.5 constituents and hospitalizations of a wide spectrum of respiratory diseases: a nationwide case-crossover study in China. Environ. Health. 2025, 3, 952-62.

3. Ma, J.; Yao, Y.; Xie, Y.; et al. Omega‑3 modify the adverse effects of long-term exposure to ambient air pollution on the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence from a nationwide prospective cohort study. Environ. Health. 2025, 3, 787-94.

4. Xu, K.; Hao, H.; Zhang, D.; et al. Long-term exposure to smoke PM2.5 and COPD caused mortality for elderly people in the contiguous United States. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109513.

5. Li, M. H.; Fan, L. C.; Mao, B.; et al. Short-term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter increases hospitalizations and mortality in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2016, 149, 447-58.

6. Perkins, E.; Garcia-Reyero, N.; Edwards, S.; et al. The adverse outcome pathway: a conceptual framework to support toxicity testing in the twenty-first century. In Computational systems toxicology; Springer New York, 2015; pp. 1-26.

7. Allen, T. E.; Goodman, J. M.; Gutsell, S.; Russell, P. J. Defining molecular initiating events in the adverse outcome pathway framework for risk assessment. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 2100-12.

8. Da Silva, E.; Vogel, U.; Hougaard, K. S.; Pérez-Gil, J.; Zuo, Y.Y.; Sørli, J. B. An adverse outcome pathway for lung surfactant function inhibition leading to decreased lung function. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 2, 225-36.

9. Ding, R.; Ren, X.; Sun, Q.; Sun, Z.; Duan, J. An integral perspective of canonical cigarette and e-cigarette-related cardiovascular toxicity based on the adverse outcome pathway framework. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 48, 227-57.

10. Benoit, L.; Jornod, F.; Zgheib, E.; et al. Adverse outcome pathway from activation of the AhR to breast cancer-related death. Environ. Int. 2022, 165, 107323.

11. Waspe, J.; Beronius, A. Development of an adverse outcome pathway for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 3, 100065.

12. Zheng, Y.; Liu, L.; Shukla, G. C. A comprehensive review of web-based non-coding RNA resources for cancer research. Cancer. Lett. 2017, 407, 1-8.

13. Almaghrbi, H.; Giordo, R.; Pintus, G.; Zayed, H. Non-coding RNAs as biomarkers of myocardial infarction. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2023, 540, 117222.

14. Ma, J.; Lin, Y.; Zhan, M.; Mann, D. L.; Stass, S. A.; Jiang, F. Differential miRNA expressions in peripheral blood mononuclear cells for diagnosis of lung cancer. Lab. Invest. 2015, 95, 1197-206.

15. Guo, X.; Sun, Y.; Azad, T.; et al. Rox8 promotes microRNA-dependent yki messenger RNA decay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 30520-30.

16. Seelan, R. S.; Greene, R. M.; Pisano, M. M. Role of lncRNAs and circRNAs in orofacial clefts. Microrna 2023, 12, 171-6.

17. Pan, J.; Xie, X.; Sheng, J.; et al. Construction and identification of lncRNA/circRNA-coregulated ceRNA networks in gemcitabine-resistant bladder carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2023, 44, 847-58.

18. Jung, G.; Hernández-Illán, E.; Moreira, L.; Balaguer, F.; Goel, A. Epigenetics of colorectal cancer: biomarker and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 111-30.

19. Nombela, P.; Miguel-López, B.; Blanco, S. The role of m6A, m5C and Ψ RNA modifications in cancer: novel therapeutic opportunities. Mol. Cancer. 2021, 20, 18.

20. Mangiavacchi, A.; Morelli, G.; Orlando, V. Behind the scenes: how RNA orchestrates the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1123975.

21. Song, L.; Li, D.; Li, X.; et al. Exposure to PM2.5 induces aberrant activation of NF-κB in human airway epithelial cells by downregulating miR-331 expression. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 50, 192-9.

22. Zhao, L.; Zhang, M.; Bai, L.; et al. Real-world PM2.5 exposure induces pathological injury and DNA damage associated with miRNAs and DNA methylation alteration in rat lungs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 28788-803.

23. Furci, F.; Allegra, A.; Tonacci, A.; et al. Air pollution and microRNAs: the role of association in airway inflammation. Life 2023, 13, 1375.

24. Fu, Y.; Li, B.; Yun, J.; et al. lncRNA SOX2-OT ceRNA network enhances the malignancy of long-term PM2.5-exposed human bronchial epithelia. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 217, 112242.

25. Li, B.; Huang, N.; Wei, S.; et al. lncRNA TUG1 as a ceRNA promotes PM exposure-induced airway hyper-reactivity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125878.

26. Yun, J.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; et al. Up-regulation of miR-297 mediates aluminum oxide nanoparticle-induced lung inflammation through activation of Notch pathway. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113839.

27. Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Q.; et al. MicroRNA-382-5p is involved in pulmonary inflammation induced by fine particulate matter exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114278.

28. Valavanidis, A.; Vlachogianni, T.; Fiotakis, K.; Loridas, S. Pulmonary oxidative stress, inflammation and cancer: respirable particulate matter, fibrous dusts and ozone as major causes of lung carcinogenesis through reactive oxygen species mechanisms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2013, 10, 3886-907.

29. Yang, C. M.; Yang, C. C.; Hsiao, L. D.; et al. Upregulation of COX-2 and PGE2 induced by TNF-α mediated through TNFR1/MitoROS/PKCα/P38 MAPK, JNK1/2/FoxO1 cascade in human cardiac fibroblasts. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 2807-24.

30. Shaw, P.; Chattopadhyay, A. Nrf2-ARE signaling in cellular protection: mechanism of action and the regulatory mechanisms. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 3119-30.

31. Veerappan, I.; Sankareswaran, S. K.; Palanisamy, R. Morin protects human respiratory cells from PM2.5 induced genotoxicity by mitigating ROS and reverting altered miRNA expression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2019, 16, 2389.

32. Wang, H.; Pan, L.; Xu, R.; Si, L.; Zhang, X. The molecular mechanism of Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in the antioxidant defense response induced by BaP in the scallop Chlamys farreri. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2019, 92, 489-99.

33. Bhargava, A.; Shukla, A.; Bunkar, N.; et al. Exposure to ultrafine particulate matter induces NF-κβ mediated epigenetic modifications. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 39-50.

34. Ilchovska, D. D.; Barrow, D. M. An overview of the NF-κB mechanism of pathophysiology in rheumatoid arthritis, investigation of the NF-κB ligand RANKL and related nutritional interventions. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102741.

35. Zinatizadeh, M. R.; Schock, B.; Chalbatani, G. M.; Zarandi, P. K.; Jalali, S. A.; Miri, S. R. The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling in cancer development and immune diseases. Genes. Dis. 2021, 8, 287-97.

36. Wan, Q.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y. Puerarin inhibits vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation induced by fine particulate matter via suppressing of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. BMC. Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 146.

37. Banerjee, J.; Khanna, S.; Bhattacharya, A. MicroRNA regulation of oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 2872156.

38. Yamamoto, M.; Singh, A.; Sava, F.; Pui, M.; Tebbutt, S. J.; Carlsten, C. MicroRNA expression in response to controlled exposure to diesel exhaust: attenuation by the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine in a randomized crossover study. Environ. Health. Perspect. 2013, 121, 670-5.

39. Eaves, L. A.; Smeester, L.; Hartwell, H. J.; et al. Isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol induces the expression of microRNAs associated with inflammatory/oxidative stress response in lung cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 381-7.

40. Zhou, T.; Yu, Q.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, G. A pilot study of blood microRNAs and lung function in young healthy adults with fine particulate matter exposure. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 7073-80.

41. Xie, J.; Li, S.; Ma, X.; et al. MiR-217-5p inhibits smog (PM2.5)-induced inflammation and oxidative stress response of mouse lung tissues and macrophages through targeting STAT1. Aging 2022, 14, 6796-808.

42. Xu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Li, D.; et al. MicroRNA-760 resists ambient PM2.5-induced apoptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells through elevating heme-oxygenase 1 expression. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117213.

43. Lee, K. Y.; Ho, S. C.; Sun, W. L.; et al. Lnc-IL7R alleviates PM2.5-mediated cellular senescence and apoptosis through EZH2 recruitment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cell. Biol. Toxicol. 2022, 38, 1097-120.

44. Deng, X.; Feng, N.; Zheng, M.; et al. PM2.5 exposure-induced autophagy is mediated by lncRNA loc146880 which also promotes the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 112-25.

45. Zhang, H.; Guan, R.; Zhang, Z.; et al. lncRNA Nqo1-AS1 attenuates cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress by upregulating its natural antisense transcript Nqo1. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 729062.

46. Wang, X.; Shen, C.; Zhu, J.; Shen, G.; Li, Z.; Dong, J. Long noncoding RNAs in the regulation of oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1318795.

47. Wang, J.; Jia, J.; Wang, D.; et al. Zn2+ loading as a critical contributor to the circ_0008553-mediated oxidative stress and inflammation in response to PM2.5 exposures. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 451-61.

48. Zheng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Duan, Y.; Mu, Q.; Wang, X. Circ-OSBPL2 contributes to smoke-related chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by targeting miR-193a-5p/BRD4 axis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2021, 16, 919-31.

49. Xue, M.; Peng, N.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, H. Hsa_circ_0006872 promotes cigarette smoke-induced apoptosis, inflammation and oxidative stress in HPMECs and BEAS-2B cells through the miR-145-5p/NF-κB axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 534, 553-60.

50. Qiao, D.; Hu, C.; Li, Q.; Fan, J. Circ-RBMS1 knockdown alleviates CSE-induced apoptosis, inflammation and oxidative stress via up-regulating FBXO11 through miR-197-3p in 16HBE cells. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2021, 16, 2105-18.

51. Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; et al. Ambient PM toxicity is correlated with expression levels of specific microRNAs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 10227-36.

52. Chen, R.; Li, H.; Cai, J.; et al. Fine particulate air pollution and the expression of microRNAs and circulating cytokines relevant to inflammation, coagulation, and vasoconstriction. Environ. Health. Perspect. 2018, 126, 017007.

53. Li, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; et al. Particulate matter air pollution and the expression of microRNAs and pro-inflammatory genes: association and mediation among children in Jinan, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 121843.

54. Rodosthenous, R. S.; Kloog, I.; Colicino, E.; et al. Extracellular vesicle-enriched microRNAs interact in the association between long-term particulate matter and blood pressure in elderly men. Environ. Res. 2018, 167, 640-9.

55. Dai, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Guo, T.; Li, W. Assessment on the lung injury of mice posed by airborne PM2.5 collected from developing area in China and associated molecular mechanisms by integrated analysis of mRNA-seq and miRNA-seq. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 224, 112661.

56. Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Ye, L.; Chen, C.; She, J.; Song, Y. MiR-29b-3p promotes particulate matter-induced inflammatory responses by regulating the C1QTNF6/AMPK pathway. Aging 2020, 12, 1141-58.

57. Zhao, J.; Xia, H.; Wu, Y.; et al. CircRNA_0026344 via miR-21 is involved in cigarette smoke-induced autophagy and apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells in emphysema. Cell. Biol. Toxicol. 2023, 39, 929-44.

58. Li, X.; Jia, Y.; Nan, A.; et al. CircRNA104250 and lncRNAuc001.dgp.1 promote the PM2.5-induced inflammatory response by co-targeting miR-3607-5p in BEAS-2B cells. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113749.

59. Zhong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Identification of long non-coding RNA and circular RNA in mice after intra-tracheal instillation with fine particulate matter. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 519-26.

60. Liao, F.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. lncRNA AABR07005593.1 potentiates PM2.5-induced interleukin-6 expression by targeting MCCC1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 226, 112834.

61. Jia, Y.; Li, X.; Nan, A.; et al. Circular RNA 406961 interacts with ILF2 to regulate PM2.5-induced inflammatory responses in human bronchial epithelial cells via activation of STAT3/JNK pathways. Environ. Int. 2020, 141, 105755.

62. Savagner, P. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenomenon. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21 Suppl 7, vii89-92.

63. Marconi, G. D.; Fonticoli, L.; Rajan, T. S.; et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT): the type-2 EMT in wound healing, tissue regeneration and organ fibrosis. Cells 2021, 10, 1587.

64. Bontinck, A.; Maes, T.; Joos, G. Asthma and air pollution: recent insights in pathogenesis and clinical implications. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 10-9.

65. Brewster, L. M.; Lichty, D.; Broznitsky, N.; Ainslie, P. N. CardioRespiratory Effects of Wildfire Suppression (CREWS) study: an experimental overview. Front. Public. Health. 2025, 13, 1578582.

66. Guo, H.; Feng, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Luo, F.; Wang, Y. A novel lncRNA, loc107985872, promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression via the notch1 signaling pathway with exposure to traffic-originated PM2.5 organic extract. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115307.

67. Wang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Sun, K.; Fan, Y.; Liao, J.; Wang, G. Identification of exosome miRNAs in bronchial epithelial cells after PM2.5 chronic exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 215, 112127.

68. Liu, L. Z.; Wang, M.; Xin, Q.; Wang, B.; Chen, G. G.; Li, M. Y. The permissive role of TCTP in PM2.5/NNK-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cells. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 66.

69. Wang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liao, J.; Wang, G. PM2.5 downregulates microRNA-139-5p and induces EMT in bronchiolar epithelium cells by targeting Notch1. J. Cancer. 2020, 11, 5758-67.

70. Huang, R.; Bai, C.; Liu, X.; et al. The p53/RMRP/miR122 signaling loop promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during the development of silica-induced lung fibrosis by activating the notch pathway. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128133.

71. Lu, Y. Y.; Lin, Y.; Ding, D. X.; et al. MiR-26a functions as a tumor suppressor in ambient particulate matter-bound metal-triggered lung cancer cell metastasis by targeting LIN28B-IL6-STAT3 axis. Arch. Toxicol. 2018, 92, 1023-35.

72. Luo, F.; Wei, H.; Guo, H.; et al. LncRNA MALAT1, an lncRNA acting via the miR-204/ZEB1 pathway, mediates the EMT induced by organic extract of PM2.5 in lung bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2019, 317, L87-98.

73. Xu, J.; Xu, H.; Ma, K.; et al. lncRNA Gm16410 mediates PM2.5-induced macrophage activation via PI3K/AKT pathway. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 618045.

74. Ma, H.; Lu, L.; Xia, H.; et al. Circ0061052 regulation of FoxC1/Snail pathway via miR-515-5p is involved in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of epithelial cells during cigarette smoke-induced airway remodeling. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 746, 141181.

75. Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; et al. Peripheral blood circular RNA hsa_circ_0058493 as a potential novel biomarker for silicosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 236, 113451.

76. Sesé, L.; Harari, S. Now we know: chronic exposure to air pollutants is a risk factor for the development of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2202113.

77. Yan, W.; Wu, Q.; Yao, W.; et al. MiR-503 modulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis by targeting PI3K p85 and is sponged by lncRNA MALAT1. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11313.

78. Lian, X.; Chen, X.; Sun, J.; et al. MicroRNA-29b inhibits supernatants from silica-treated macrophages from inducing extracellular matrix synthesis in lung fibroblasts. Toxicol. Res. 2017, 6, 878-88.

79. Pang, X.; Shi, H.; Chen, X.; et al. miRNA-34c-5p targets Fra-1 to inhibit pulmonary fibrosis induced by silica through p53 and PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 2019-32.

80. Wang, D.; Hao, C.; Zhang, L.; et al. Exosomal miR-125a-5p derived from silica-exposed macrophages induces fibroblast transdifferentiation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 192, 110253.

81. Han, B.; Chu, C.; Su, X.; et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent primary microRNA-126 processing activated PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway drove the development of pulmonary fibrosis induced by nanoscale carbon black particles in rats. Nanotoxicology 2020, 14, 1-20.

82. Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Pan, H.; et al. LncRNA-PVT1 activates lung fibroblasts via miR-497-5p and is facilitated by FOXM1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 213, 112030.

83. Wu, Q.; Jiao, B.; Gui, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, F.; Han, L. Long non-coding RNA SNHG1 promotes fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition during the development of pulmonary fibrosis induced by silica particles exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 112938.

84. Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.; et al. ATF3-activated accelerating effect of LINC00941/lncIAPF on fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation by blocking autophagy depending on ELAVL1/HuR in pulmonary fibrosis. Autophagy 2022, 18, 2636-55.

85. Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Talifu, D.; et al. Distribution and sources of PM2.5-bound free silica in the atmosphere of hyper-arid regions in Hotan, North-West China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 810, 152368.

86. Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Mao, Z.; Gao, C. ROS-responsive nanoparticles for suppressing the cytotoxicity and immunogenicity caused by PM2.5 particulates. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1777-88.

87. Zhou, T.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. PM2.5 downregulates miR-194-3p and accelerates apoptosis in cigarette-inflamed bronchial epithelium by targeting death-associated protein kinase 1. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2018, 13, 2339-49.

88. Song, L.; Li, D.; Gu, Y.; Li, X.; Peng, L. Let-7a modulates particulate matter (≤ 2.5 μm)-induced oxidative stress and injury in human airway epithelial cells by targeting arginase 2. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2016, 36, 1302-10.

89. Li, X.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, C.; et al. MicroRNA-1228* inhibit apoptosis in A549 cells exposed to fine particulate matter. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 10103-13.

90. Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Gao, N.; et al. MicroRNA-802/Rnd3 pathway imposes on carcinogenesis and metastasis of fine particulate matter exposure. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 35026-43.

91. Lei, Z.; Guo, H.; Zou, S.; Jiang, J.; Kui, Y.; Song, J. Long non-coding RNA maternally expressed gene regulates cigarette smoke extract induced lung inflammation and human bronchial epithelial apoptosis via miR-149-3p. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 60.

92. Yang, J.; Huo, T.; Zhang, X.; et al. Oxidative stress and cell cycle arrest induced by short-term exposure to dustfall PM2.5 in A549 cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 22408-19.

93. Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Peng, X.; et al. LncRNA LINC00341 mediates PM2.5-induced cell cycle arrest in human bronchial epithelial cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 276, 1-10.

94. Ling, X. X.; Zhang, H. Q.; Liu, J. X.; et al. LncRNA LUCAT1 activation mediated by the down-regulation of DNMT1 is involved in cell apoptosis induced by PM2.5. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2018, 31, 608-12.

95. Jin, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, M. circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction. Open. Med. 2021, 16, 854-63.