Molecular Insights into the estrogenic effects and human health risks of bisphenol AF and bisphenol fluorene

Abstract

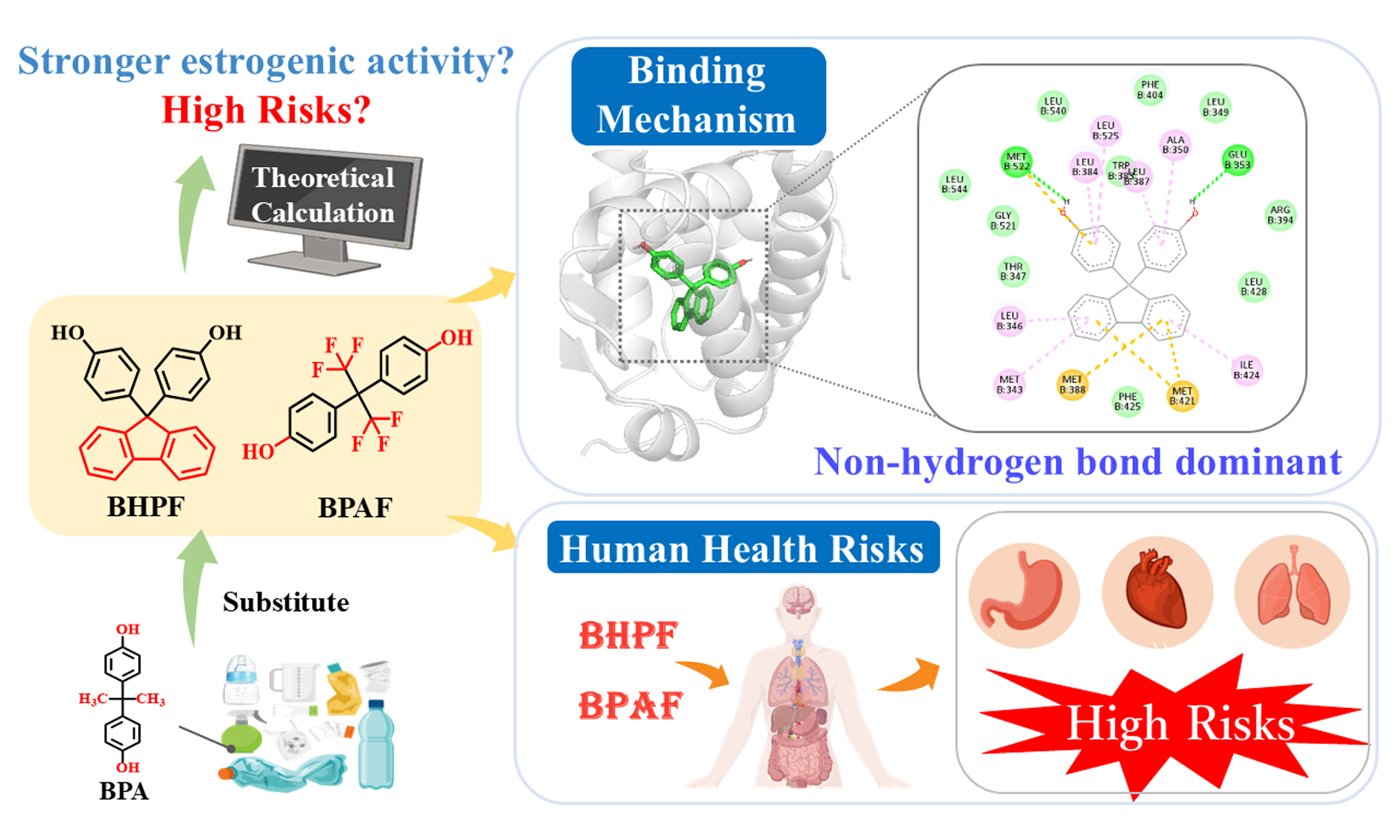

Bisphenol A (BPA) has been strictly regulated worldwide due to its well-documented adverse health effects, prompting the widespread use of structural analogs such as bisphenol AF (BPAF) and bisphenol fluorene (BHPF). Emerging evidence shows that these substitutes also exhibit estrogenic activity, challenging their presumed safety. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying their modulation of estrogen receptors (ERs) remain largely unknown. Addressing this gap is critical for accurate risk assessment and the development of safer alternatives. Herein, we employed computational toxicology approaches to elucidate the interaction mechanisms of BPAF and BHPF with ER alpha (ERα), a central regulator of endocrine function and breast cancer progression. Our results showed that BHPF displays the greatest estrogenic potency among the tested compounds. Molecular interaction analyses revealed that hydrophobic interactions, especially the van der Waals force, rather than hydrogen bonding, predominantly govern the binding of the two bisphenol derivatives (BPs) to ERα. Notably, the rigid fluorenyl ring structure of BHPF markedly enhances van der Waals interactions, resulting in more stable ER binding and suggesting potential for high biological retention and cumulative risk. Consistently, toxicological assessments indicated that BHPF poses elevated health risks to the lungs and gastrointestinal system. By contrast, BPAF, with its flexible scaffold, exhibited more diverse binding interactions. It exhibits stronger organ-specific toxicity, notably affecting the cardiovascular system and kidneys. This study provides molecular-level insight into the binding mechanisms of BPs with ERα, offering theoretical support for understanding their potential endocrine-disrupting effects and informing environmental health risk assessments.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Bisphenol A (BPA) is one of the most widely produced industrial chemicals globally, primarily used in the manufacture of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins[1,2]. Its widespread use and large-scale production[2,3] have led to frequent migration from consumer products into the environment[4], resulting in continuous global emissions and pervasive environmental contamination. Consequently, human populations are subject to pervasive exposure to BPA, raising significant public health concerns[5,6]. Extensive studies have identified BPA as an endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC), strongly linked to numerous reproductive and developmental disorders, including precocious puberty, breast cancer, and prostate cancer[5,7]. More recently, BPA has also been implicated as a potential metabolic disruptor, associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular diseases[8,9]. Given its health risks, regulatory agencies worldwide, including the European Union, have imposed restrictions on BPA migration from food-contact materials[10]. As a result, structurally similar bisphenol derivatives (BPs), such as bisphenol AF [4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphenol, BPAF] and bisphenol fluorene [9,9-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)fluorene, BHPF], have been developed and widely adopted in industrial applications[11,12].

Environmental and biomonitoring studies show that these substitutes, including BPAF and BHPF, are ubiquitously present in aquatic environments, indoor dust, and human biological samples such as urine, with concentrations often comparable to or exceeding those of BPA[13,14]. These findings suggest that human exposure to BPA analogs may be just as extensive as BPA itself. Importantly, recent toxicological investigations have challenged the assumption that these analogs are necessarily safer[15]. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that BPAF and BHPF exert significant toxic effects, largely mediated via estrogen receptor (ER) pathways. For example, BPAF has been shown to activate ER signaling pathways and upregulate estrogen-responsive genes in zebrafish embryos, indicating a potent estrogenic effect[16]. In contrast, BHPF exhibits anti-estrogenic activity by suppressing ER-regulated gene expression in various model organisms, indicating a distinct yet equally worrisome mechanism of action[17]. Additionally, BPAF could promote the proliferation of breast cancer cells MCF-7 with stronger transcriptional activation than BPA[18], underscoring its potential for endocrine disruption. At the molecular level, both BPAF and BHPF have been shown to regulate ER-mediated signaling and alter the expression of estrogen-responsive genes, indicating that their toxicities may be closely related to ER pathways[17,18]. Collectively, these findings highlight ER binding and subsequent transcriptional regulation as key contributors to the toxic effects of BPs. Importantly, converging evidence supports that ER binding represents the most well-established molecular initiating event (MIE) for bisphenol-induced endocrine disruption, serving as the primary trigger of downstream toxicological pathways[19]. Despite growing experimental evidence on the toxicity of BPs, the specific molecular interactions between these compounds and ER alpha (ERα) are not yet fully understood.

Existing research on BPs has primarily relied on in vitro experiments and animal models. While these approaches provide valuable insights, they remain limited in capturing the dynamic interactions and mechanistic intricacies between BPs and ERα, owing to constraints in experimental resolution, timescale, and environmental relevance. This limitation underscores the urgent need for complementary methodologies capable of elucidating the molecular basis of their toxicological effects. To address this challenge, computational approaches, particularly molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, have emerged as powerful tools for analyzing the interaction mechanisms between compounds and receptors[20,21]. These methods enable detailed characterization of ligand–receptor interactions, providing quantitative information on binding affinities and conformational dynamics within the ERα ligand-binding domain (LBD), and facilitating comparative analyses of agonistic and antagonistic binding mechanisms[22]. For instance, studies using AutoDock and Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) have shown that hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions are the principal forces contributing to the stability of bisphenol-F-human estrogen-related receptor γ (BPF-hERRγ) complexes[23]. Similarly, BPAF exhibited higher binding affinity for nuclear receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) and retinoid X receptors (RXR) compared to BPA[24], supporting the predictive power of structure-based computational techniques.

In this context, we systematically investigated the interactions of BPAF and BHPF with ERα using computational toxicology approaches, including molecular docking and MD simulations. By characterizing their binding modes and binding free energy profiles, this study provides mechanistic insights into their endocrine-disrupting potential and offers theoretical support for improved environmental health risk assessment.

EXPERIMENTAL

Molecular docking

The target compounds in this study were bisphenol analogs BPAF and BHPF. All ligand structures were obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and preoptimized prior to docking. Geometry optimization was conducted using Gaussian 09 D.01[25], employing the hybrid density functional method M06-2X with the 6-31G (d, p) basis set[26]. To account for solvation effects, the solvation model based on density (SMD) implicit solvent model was used to simulate aqueous conditions[27].

To explore the potential interactions between these ligands and the ERα LBD, ligand–protein docking simulations were performed using AutoDock 4.2.6[28]. The crystal structure of human ERα (PDB ID: 3UUD) was retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3UUD). The co-crystallized ligands and water molecules were removed, retaining only chain A. Missing hydrogen atoms were added using AutoDockTools, and the processed structure was saved in PDBQT [Protein Data Bank, Partial Charge (Q), & Atom Type (T)] format. Ligands were docked into the ERα binding pocket based on the coordinates of the positive control ligand, 17β-estradiol (E2). The docking grid was set to dimensions of 56 Å × 56 Å ×

MD simulation

MD simulations offer high-resolution insights into the structural and temporal behavior of biomolecular systems. They are particularly valuable for elucidating receptor-ligand interaction mechanisms by capturing conformational dynamics at the atomic level. Based on molecular docking results, the lowest-energy complex of ERα bound to each target compound was selected as the initial structure for MD simulation. To ensure comparability, all reference estrogens [estrone (E1), E2, diethylstilbestrol (DES)] and BPs were modeled in parallel under identical docking and MD simulation parameters. Although these molecules differ structurally, applying a uniform simulation protocol allows for the relative evaluation of their binding affinities[20]. All simulations were conducted using GROMACS[29,30] with the AMBER14SB force field for proteins[22]. Ligand parameters were generated using the General Amber Force Field (GAFF) via Sobtop version 1.0 (dev 3.1). The protein-ligand complex was solvated in a cubic box filled with transferable intermolecular potential with 3 points (TIP3P) water molecules[31], ensuring a minimum distance of 1.0 nm between any protein atom and the box boundary. To neutralize the system, five sodium ions were added. Energy minimization was carried out using the steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms. The system was then gradually heated from 0 to 310.15 K under constant number of particles, volume, and temperature (NVT) conditions, followed by 2 ns of equilibration at constant temperature. Integration time step for equilibration was 1 fs, while a 2 fs time step was used for the 100 ns production run. Long-range electrostatic and van der Waals interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method[32]. Simulation trajectories were saved every 2 ps for subsequent analysis. The binding free energy between ERα and each ligand was estimated using the MM/PBSA method[33], implemented through the gmx _MMPBSA tool[34,35].

Human health risk assessment

To further assess the potential health risks associated with BPs, the ACD/Percepta platform (www.acdlabs.com) was employed to obtain their ERα binding affinity and organ-specific toxicity. The Human Health module generates probabilistic estimates of adverse effects across major human physiological systems based on chemical structure and existing datasets, offering a complementary perspective on systemic toxicity.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Assessment of estrogenic disruption effects

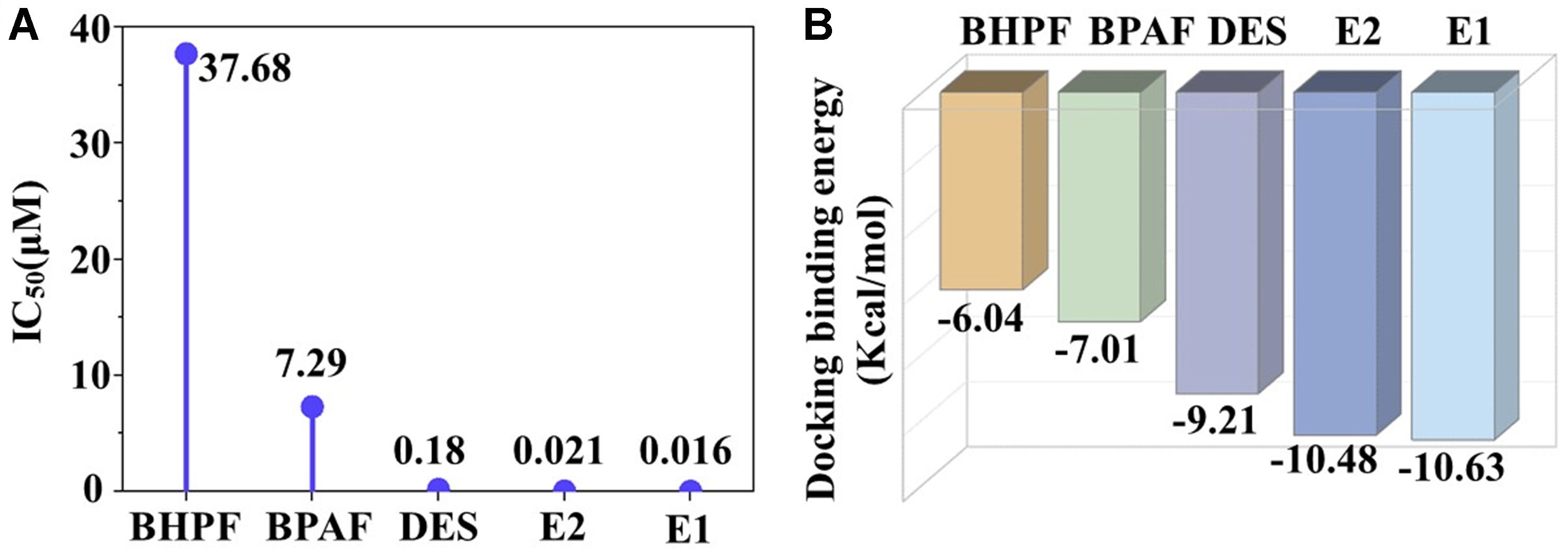

In endocrine disruption studies, natural estrogens such as E2 (and sometimes E1) are widely used as positive controls for benchmarking the activity of environmental chemicals. Therefore, in our study, we used E2 and E1 as docking and MD comparators to ensure reliable interpretation based on their well-characterized ERα-binding modes. To validate the accuracy of the docking model, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for E2 was predicted to be 0.021 μM, which closely matches the experimentally reported value of 0.014 μM[36]. This strong agreement affirms the reliability and predictive capability of the established docking protocol. Using this validated approach, the IC50 values for BPAF and BHPF were calculated to be 7.29 and 37.68 μM, respectively. Both values were markedly higher than those of natural estrogens E2 and E1 (0.021 and 0.016 μM, respectively; Figure 1A), indicating weaker estrogenic activity of the two bisphenols compared with endogenous estrogens. These computational findings align with previous experimental observations[37], which consistently reported lower estrogenic potency for BPA analogs relative to natural estrogens. Nevertheless, some in vivo studies have suggested that BPAF may exert greater overall toxicity than BPA, highlighting the complexity and potential unpredictability of endocrine-disrupting effects associated with structural analogs. This discrepancy underscores the importance of complementing experimental evidence with detailed, molecular-level mechanistic insights.

Figure 1. (A) Predicted IC50 values (μM) and (B) Molecular docking binding energies (kcal/mol) for the interactions between BPAF, BHPF, and ERα-LBD. IC50: Half maximal inhibitory concentration; BPAF: bisphenol AF; BHPF: bisphenol fluorene; ERα: estrogen receptor alpha; LBD: ligand-binding domain; DES: diethylstilbestrol.

Binding interactions of BPs with ERα

From the perspective of binding affinity, molecular docking results [Figure 1B] showed that the binding energies of BPAF (-7.01 kcal/mol) and BHPF (-6.04 kcal/mol) were significantly higher than those of E2

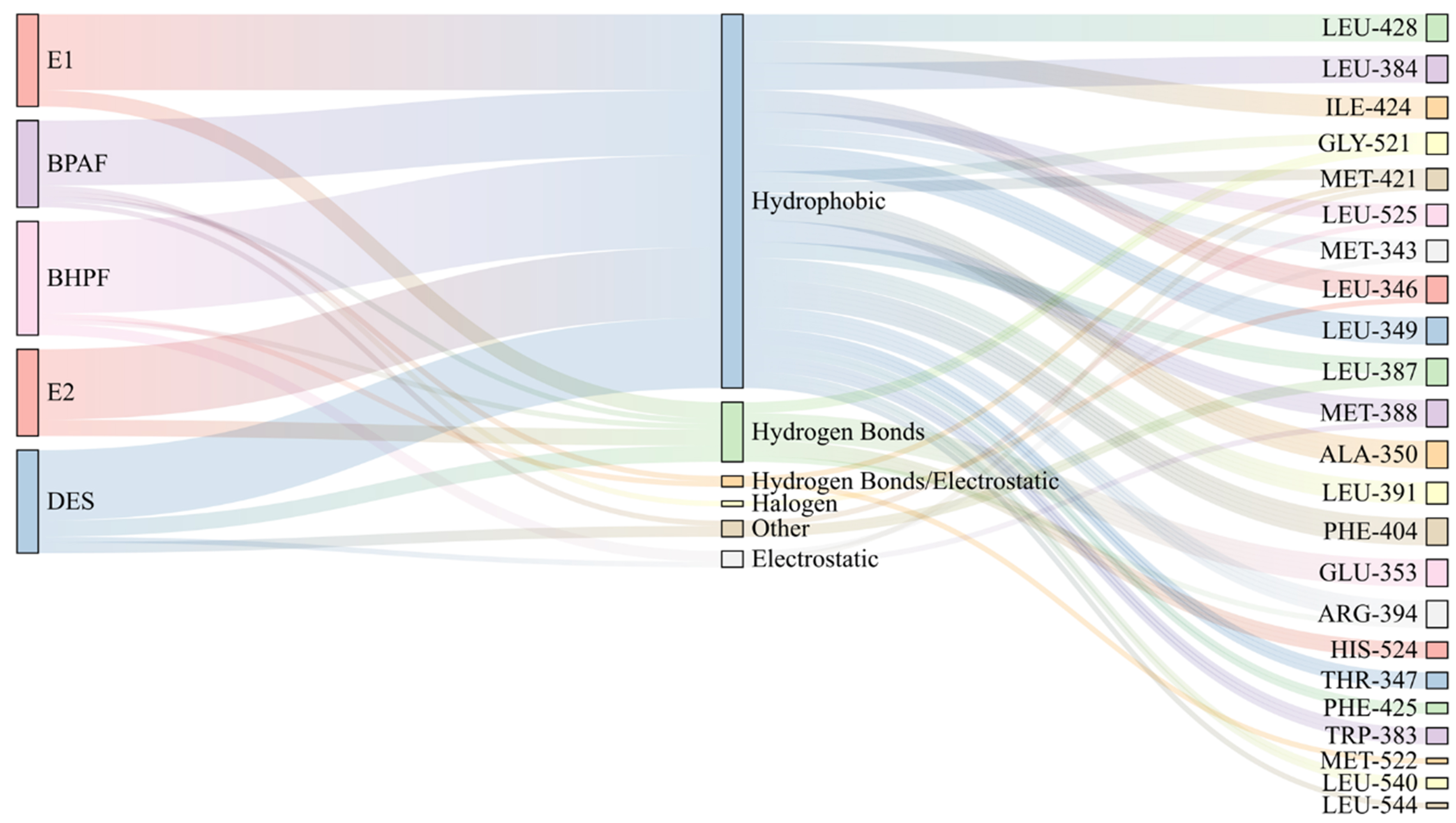

To explore the binding mechanisms in greater detail, visualization of the docking poses revealed distinct differences in interaction patterns between natural/synthetic estrogens and BPA analogs, as shown in Supplementary Figures 1-4. Generally, when natural or synthetic estrogens bind to ERα-LBD, a stable hydrogen bond network is formed between the hydroxyl groups on their aromatic rings and key polar residues Glu 353, Arg 394, and His 524 [Supplementary Figure 1], establishing a classic polar anchoring framework that stabilizes the ligand–receptor complex. By contrast, BHPF formed only one single hydrogen bond and BPAF two with ERα-LBD [Supplementary Figure 2], suggesting that the hydrogen bonding is not their main interaction mechanism for the two BPs and that other types of interactions may contribute to their binding. Further comprehensive visualization analyses show a dominant role for hydrophobic contacts in stabilizing these complexes [Figure 2], with BHPF exhibiting especially strong hydrophobic engagement. As shown in Supplementary Figure 4, BHPF primarily interacts via van der Waals force, Alkyl/Pi-Alkyl contacts, and Pi-Sulfur interaction with methionine (Met), forming a robust hydrophobic interface. In addition to these interactions, BPAF engages in a diverse array of weaker contacts, including halogen and Pi-Sigma interactions, contributing to its binding profile. This interaction diversity suggests that BPAF may adopt multiple binding conformations within ERα-LBD, in contrast to the relatively stable and concentrated hydrophobic binding mode of BHPF.

Figure 2. Ligand–protein interaction diagrams illustrating key residues and interaction types involved in BPAF and BHPF binding to ERα-LBD. BPAF: Bisphenol AF; BHPF: bisphenol fluorene; ERα: estrogen receptor alpha; LBD: ligand-binding domain; DES: diethylstilbestrol.

These differences in interaction patterns are largely attributable to the structural features of the two molecules. BHPF contains a rigid fluorene ring [Supplementary Scheme 1], which aligns well with the hydrophobic pocket of ERα-LBD. However, this complementarity requires conformational adjustment of the receptor, resulting in initial RMSD fluctuations [Supplementary Figure 5]. Once accommodated, the fluorene core establishes a compact van der Waals network with residues such as Ile, Leu, and Met, enhancing binding affinity. In contrast, BPAF exhibits a more flexible backbone, and its polar modifications, introduced by fluorine atoms and hydroxyl groups (–CF3, –OH), enable it to participate in diverse interactions including halogen bonding and weak hydrogen bonding. This structural flexibility enables BPAF to adopt multiple binding conformations within ERα-LBD, reflecting a more dynamic and complex binding mode.

Notably, the weaker binding affinity of BPAF and BHPF can be attributed to the docking-based predictions that derived solely from hydrogen bond analyses, thereby neglecting critical factors influencing ligand–receptor stability. To achieve a more accurate assessment of their binding behavior, MD simulations are warranted to incorporate hydrophobic contributions, induced-fit effects, solvent interactions, and entropy changes.

Binding mechanism of BPs with ERα

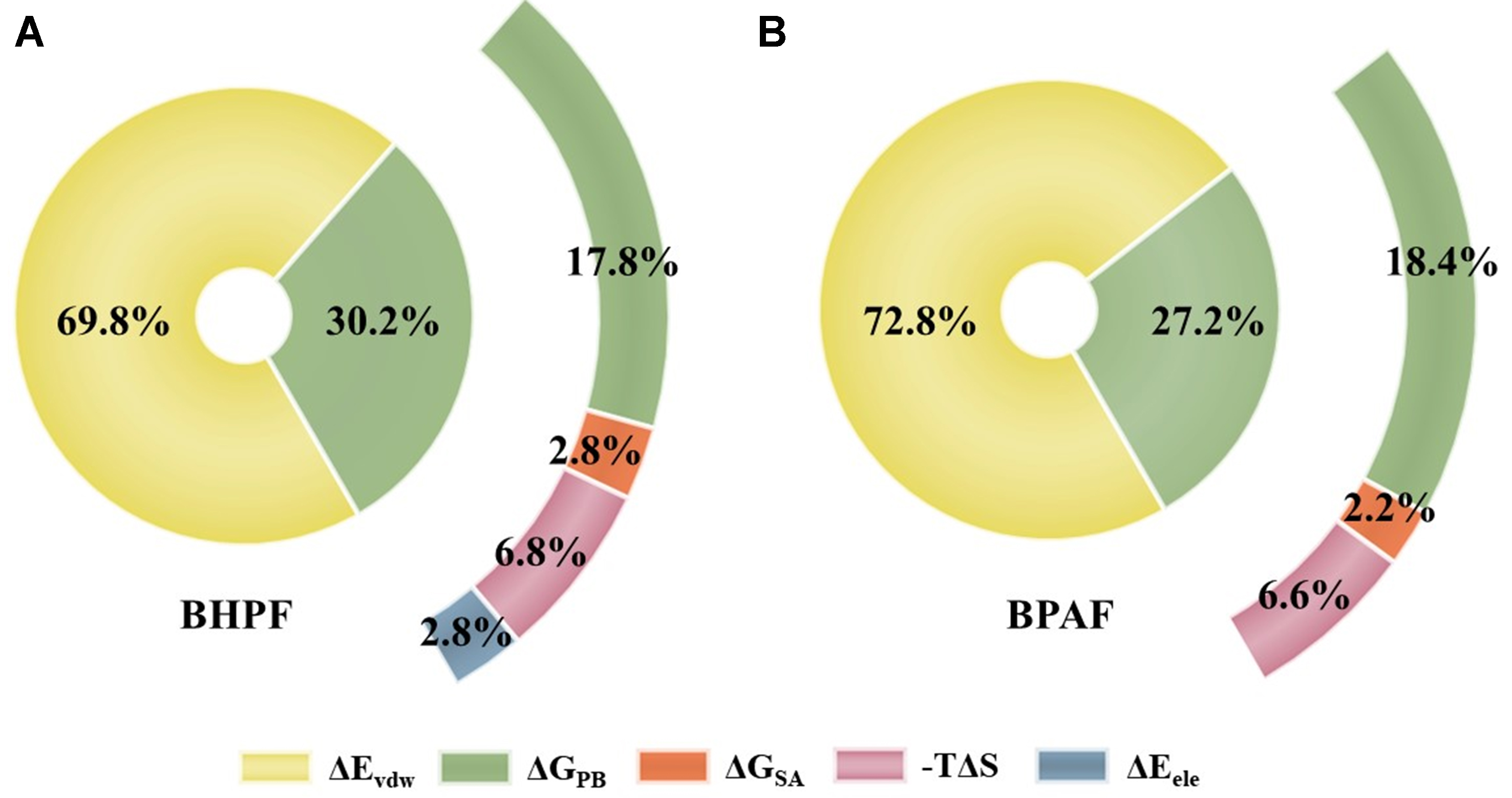

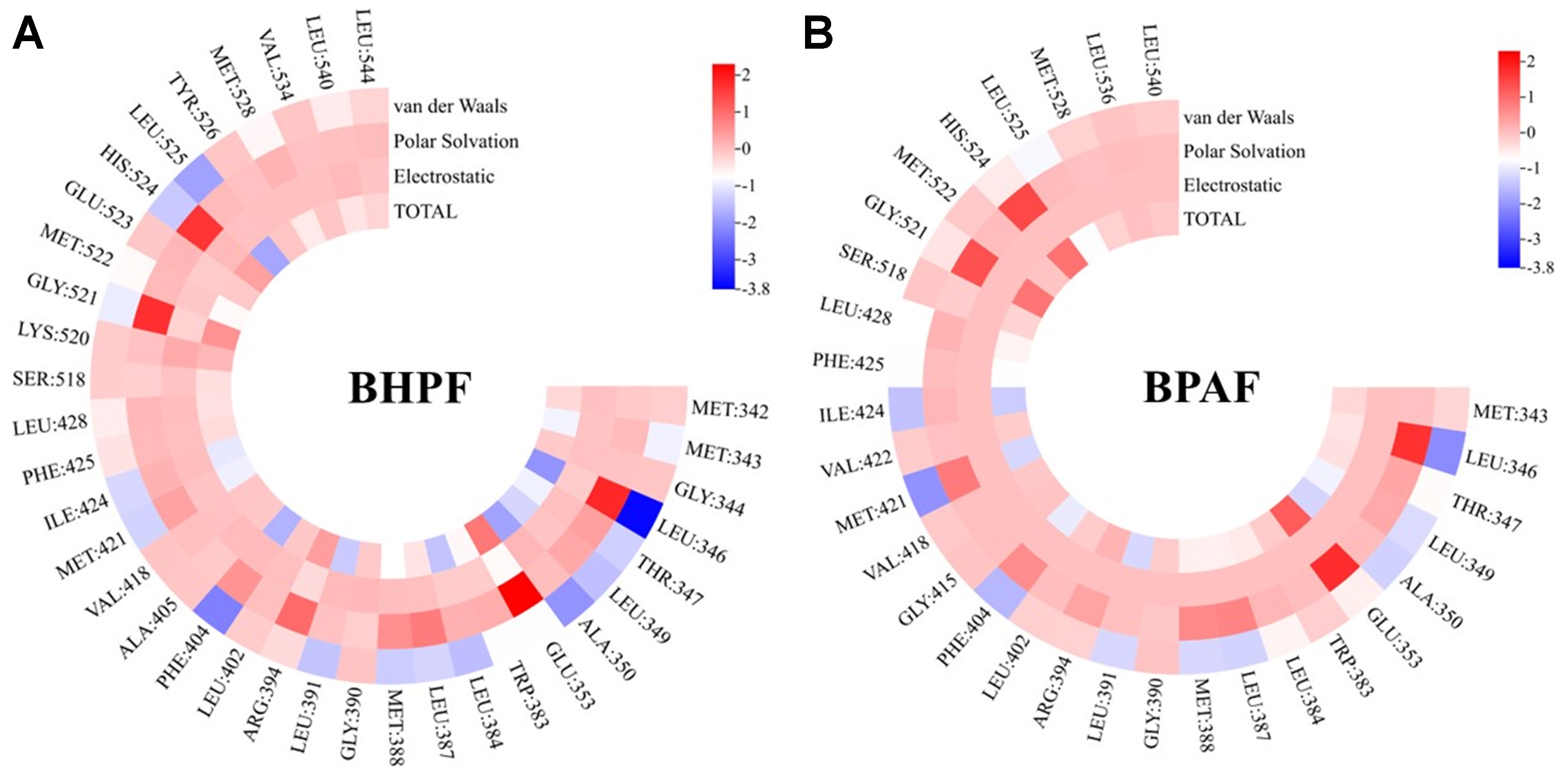

To more accurately quantify the binding affinity between BPs and ERα and to elucidate the key driving forces governing these interactions, MD simulations were conducted for each ligand–receptor complex. The obtained binding free energies and their contributing components are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 3. BHPF exhibited a markedly lower ΔGbind (-48.34 kcal/mol) compared with BPAF (-25.25 kcal/mol), and even natural and synthetic estrogens, such as E1 (-28.84 kcal/mol), E2 (-27.56 kcal/mol), and DES

Figure 3. Energy component contributions to the MM/PBSA-calculated binding free energy of BPAF and BHPF with ERα. MM/PBSA: Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area; BPAF: bisphenol AF; BHPF: bisphenol fluorene; ERα: estrogen receptor alpha.

Although BHPF had the highest polar solvation energy (ΔGPB = 16.63 kcal/mol), which would be expected to hinder binding, this unfavorable factor was fully offset by its strong van der Waals attraction. By contrast, BPAF showed lower polar solvation energy and entropy loss, generally favorable for binding. However, its van der Waals energy (-36.77 kcal/mol) was approximately half of that observed for BHPF, resulting in a significantly reduced overall binding affinity. This difference can be attributed to the structural features of the two molecules. The biphenyl core of BPAF has a smaller hydrophobic surface area compared to the rigid fluorene ring of BHPF, which limits its ability to form extensive hydrophobic contacts. Although BPAF exhibited energetic advantages in solvation and entropy, these were insufficient to compensate for its reduced van der Waals stabilization. These results confirm that van der Waals interactions, closely associated with hydrophobic contacts, are the dominant forces stabilizing BPs–ERα complexes. This finding highlights a binding mode for BPs that is not dominated by hydrogen bonding and emphasizes the key role of hydrophobic interactions in their toxicological mechanisms.

To further elucidate the binding mechanism, we systematically analyzed the amino acid residues involved in BPs-ERα binding [Figure 4]. BHPF and BPAF were found to interact with 35 and 30 residues, respectively, both exceeding the 21-29 residues involved in natural estrogen binding. Over 60% of these contacts were hydrophobic, including residues such as Leu, Ile, Met, and Ala, supporting the predominance of hydrophobic interactions in BPs-induced estrogenic disruption. All key residues, defined as those contributing ≤ -1 kcal·mol-1 to the total binding free energy[38], were hydrophobic. Leu 391, Ala 350, and Ile 421 consistently contributed across all BPs–ERα complexes, underscoring their important role in ligand binding.

Health risk assessment

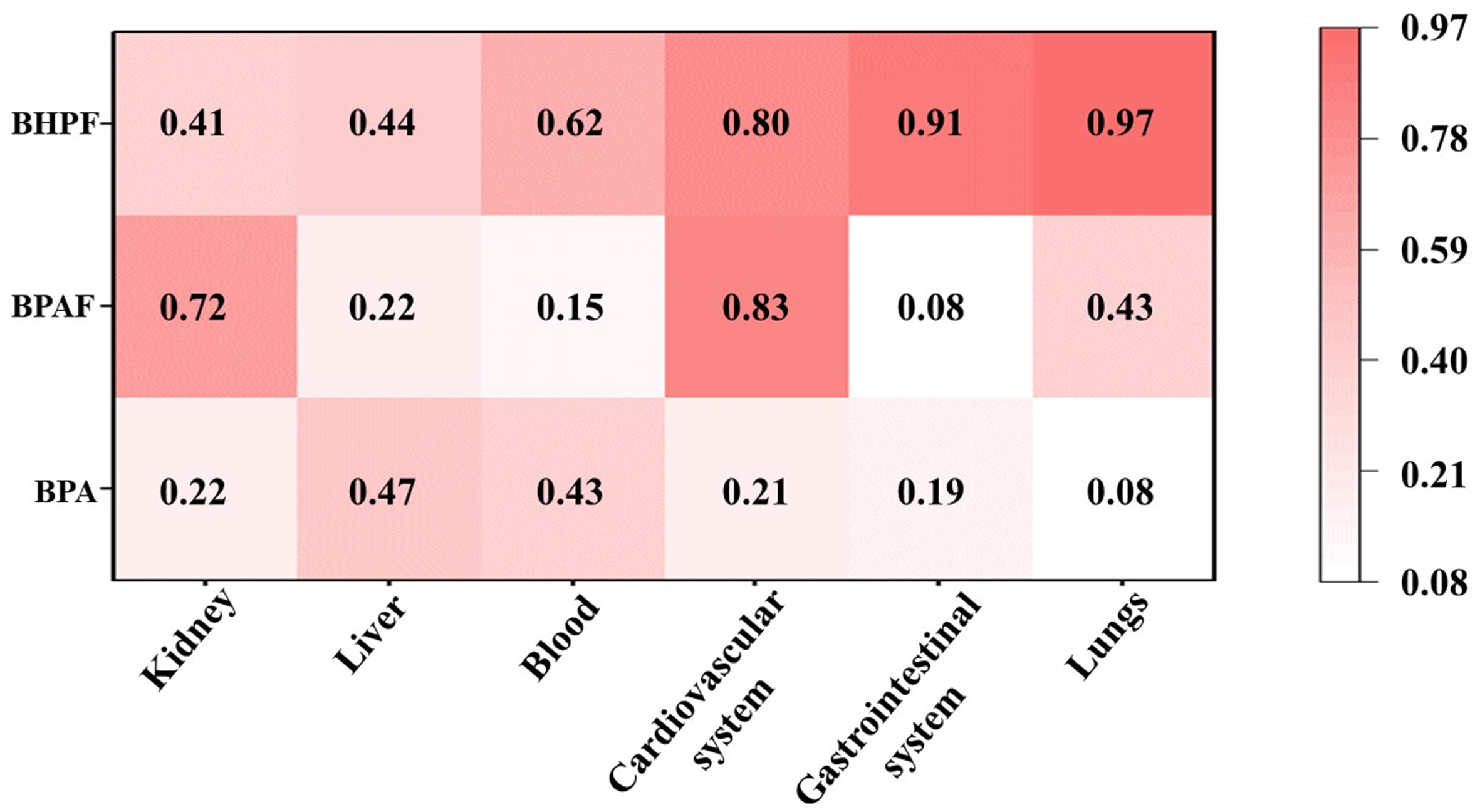

To provide a more integrated assessment of the health risks posed by BPA alternatives, we predicted their ERα binding affinity and organ-specific toxicity using the ACD/Percepta platform [Supplementary Table 2 and Figure 5]. The logarithm of the relative binding affinity (RBA) to E2, LogRBA, was used to quantify ERα binding potential. LogRBA > 0 indicates affinity equal to or exceeding E2, whereas -3 < LogRBA ≤ 0 denotes weaker but detectable binding. Compounds with a predicted probability of LogRBA > 0 exceeding 0.5 were classified as “Strong Binders”, and others as “Weak Binders”. According to this criterion[39,40], BHPF was classified as a strong binder (LogRBA > 0, probability = 0.65), while both BPA and BPAF were predicted to be weak binders (-3 < LogRBA) [Supplementary Table 2]. These results suggest that BHPF exhibits higher estrogenic activity and potentially greater health risks.

Figure 5. Predicted toxicity probability values (p) of BPA, BPAF, and BHPF across human organ systems (The probability values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater potential toxicity risk). BPA: Bisphenol A; BPAF: bisphenol AF; BHPF: bisphenol fluorene.

To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the toxic effects, we further evaluated the potential organ-specific toxicity of each compound, despite the lack of a direct mechanistic link between ERα binding and organ-specific toxicity. The probability (p) ranged from 0 to 1 for each predicted adverse effect, with higher values indicating greater toxicological risk. P-values ≥ 0.7 were defined as a threshold for high-risk toxicity. The P-values of BPA ranged from 0.08 to 0.47, indicating toxic effects on multiple organ systems, with particularly pronounced hepatotoxicity. These findings are consistent with evidence reported in previous in vivo and in vitro studies[41,42]. For instance, these findings reveal that BPA and arsenic (As) promote hepatotoxicity in zebrafish[43]. In contrast, BHPF exhibited markedly higher toxic potential than BPA, with notably elevated risks in the lungs (0.97) and gastrointestinal system (0.91), whereas BPAF displayed a more organ-specific toxicity profile, particularly toward the cardiovascular system (0.83) and kidney (0.72). These computational predictions align with experimental observations. Acute BHPF exposure (0.05-0.5 mg/L) caused significant pericardial edema and bradycardia in zebrafish embryos[44], and oral administration in mice aggravated intestinal inflammation via gut-associated pathways[45]. In agreement, BPAF exposure (1-4 μM) significantly decreased heart rate and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in zebrafish embryos[46]. Moreover, BPA exposure has also been shown to markedly suppress cardiac activity in zebrafish embryos, reducing heart rate from 167 bpm in controls to 98 bpm at 25 μM, and nearly abolishing it at 50 μM[47]. Under comparable exposure conditions, both BPAF and BHPF induced more severe developmental and cardiac toxicity than BPA, including bradycardia, pericardial edema, and increased mortality. This integrated evidence, combining receptor binding, organ-level toxicity predictions, and experimental validation, demonstrates that BHPF poses a greater health risk compared with BPA, while BPAF also presents notable organ-specific hazards.

Overall, the health risk assessment revealed that BPA substitutes may not represent safer alternatives to BPA. Specifically, BHPF exhibited the strongest ERα binding affinity together with broad-spectrum organ toxicity, suggesting a higher likelihood of systemic effects and in vivo accumulation. In contrast, BPAF, although generally weaker in binding, exhibited pronounced organ-selective toxicity, particularly in the cardiovascular system. Collectively, these findings indicate that BPA substitutes cannot be regarded as safer alternatives.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, our analysis primarily focused on ERα binding as a MIE to compare the potential endocrine-disrupting activities of BPAF and BHPF. While ERα binding is a well-established pathway mediating the endocrine effects of BPs, it is not the sole determinant of their overall toxicity. BPs may also exert effects through other mechanisms, such as rapid estrogen signaling via G protein–coupled receptors, modulation of endogenous hormone synthesis, and differential transcriptional regulation depending on receptor–DNA interactions. Therefore, ERα binding affinity alone cannot fully explain their systemic toxicities, and future studies integrating additional molecular and cellular pathways are warranted. Second, while molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations provide valuable molecular-level insights into ligand–receptor interactions, these approaches still involve inherent methodological limitations. Docking relies on relatively static receptor conformations and may not fully capture protein flexibility, whereas the 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations, although sufficient to describe major conformational changes, may not encompass all long-timescale motions. In addition, MM/PBSA-based binding free energy calculations depend on force field and solvation model assumptions and are most reliable for comparative rather than absolute affinity estimation. Finally, the ACD/Percepta platform was originally developed to support early safety evaluation of drug candidates at therapeutic dose levels, and its predictions are based on chemical structure and pharmaceutical datasets. It provides probabilistic predictions of target-organ toxicities and does not explicitly model ERα-related mechanisms. As such, its predictions for environmental chemicals such as BPAF and BHPF may not fully capture their complex biological effects. In this study, the ACD/Percepta results were used only as complementary, qualitative indicators for comparative assessment rather than as definitive evidence of toxicity. Accordingly, these predictions should be interpreted cautiously and ideally validated with further experimental studies.

CONCLUSION

This study provides molecular-level insights into the interaction mechanisms of BPA analogs, BPAF and BHPF, with ERα. The results demonstrated that BPAF and BHPF exhibit endocrine-disrupting potential, warranting careful consideration. Their binding is predominantly governed by hydrophobic interactions, particularly van der Waals forces, rather than hydrogen bonding. Notably, the rigid fluorenyl ring of BHPF enhances van der Waals interactions and confers greater binding stability, which may promote in vivo retention and bioaccumulation, thereby increasing the risk of systemic adverse health effects, especially to the lungs and gastrointestinal system. In contrast, the more flexible scaffold of BPAF, together with its polar substituents, enables diverse binding interactions, leading to organ-specific toxicity particularly affecting the cardiovascular system and kidneys. Collectively, these findings highlight that BPA substitutes, far from being inherently safer, may pose distinct and even greater health risks, underscoring the imperative for comprehensive toxicological evaluation and rational design of next-generation endocrine-safe materials.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Investigation, software, validation, visualization, data analysis, and draft preparation: Bi, Y.

Methodology and data analysis: Chen, G.

Data validation and visualization: Chen, Y.

Investigation and data analysis: Cai, W.

Conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, software, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing - review and editing: Gao, Y.

Data curation: Ji, Y.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Materials. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42322704, 42277222), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023B1515020078), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3105600).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Ma, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; et al. The adverse health effects of bisphenol A and related toxicity mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108575.

2. Vilarinho, F.; Sendón, R.; van der Kellen, A.; Vaz, M.; Silva, A. S. Bisphenol A in food as a result of its migration from food packaging. Trends. Food. Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 33-65.

3. Hahladakis, J. N.; Iacovidou, E.; Gerassimidou, S. An overview of the occurrence, fate, and human risks of the bisphenol-A present in plastic materials, components, and products. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2023, 19, 45-62.

4. Krivohlavek, A.; Mikulec, N.; Budeč, M.; et al. Migration of BPA from food packaging and household products on the Croatian market. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2023, 20, 2877.

5. Khan, N. G.; Correia, J.; Adiga, D.; et al. A comprehensive review on the carcinogenic potential of bisphenol A: clues and evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 19643-63.

6. Abraham, A.; Chakraborty, P. A review on sources and health impacts of bisphenol A. Rev. Environ. Health. 2020, 35, 201-10.

7. Tan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, L.; Widelka, M.; Chen, D. Neonatal exposure to bisphenol analogues disrupts genital development in male mice. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 330, 121783.

8. Lv, Y.; Li, L.; Fang, Y.; et al. In utero exposure to bisphenol A disrupts fetal testis development in rats. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 217-24.

9. Diamante, G.; Cely, I.; Zamora, Z.; et al. Systems toxicogenomics of prenatal low-dose BPA exposure on liver metabolic pathways, gut microbiota, and metabolic health in mice. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106260.

10. Frankowski, R.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Grześkowiak, T.; Sójka, K. The presence of bisphenol A in the thermal paper in the face of changing European regulations - a comparative global research. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 114879.

11. Frankowski, R.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Smułek, W.; Grześkowiak, T. Removal of bisphenol A and its potential substitutes by biodegradation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 191, 1100-10.

12. Wang, J.; Hong, X.; Liu, W.; et al. Comprehensive assessment of the safety of bisphenol A and its analogs based on multi-toxicity tests in vitro. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 486, 136983.

13. Pan, Y.; Xie, R.; Wei, X.; Li, A. J.; Zeng, L. Bisphenol and analogues in indoor dust from E-waste recycling sites, neighboring residential homes, and urban residential homes: implications for human exposure. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 907, 168012.

14. Bousoumah, R.; Leso, V.; Iavicoli, I.; et al. Biomonitoring of occupational exposure to bisphenol A, bisphenol S and bisphenol F: a systematic review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 783, 146905.

15. Pathak, R. K.; Jung, D. W.; Shin, S. H.; Ryu, B. Y.; Lee, H. S.; Kim, J. M. Deciphering the mechanisms and interactions of the endocrine disruptor bisphenol A and its analogs with the androgen receptor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133935.

16. Li, R.; Liu, S.; Qiu, W.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis of bisphenol AF on early growth and development of zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2020, 4, 100054.

17. Fan, X.; Guo, J.; Jia, X.; et al. Reproductive toxicity and teratogenicity of fluorene-9-bisphenol on Chinese medaka (Oryzias sinensis): a study from laboratory to field. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 561-9.

18. Lei, B.; Sun, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Bisphenol AF exerts estrogenic activity in MCF-7 cells through activation of Erk and PI3K/Akt signals via GPER signaling pathway. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 362-70.

19. Stanojević, M.; Sollner Dolenc, M. Mechanisms of bisphenol A and its analogs as endocrine disruptors via nuclear receptors and related signaling pathways. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 2397-417.

20. Salmaso, V.; Moro, S. Bridging molecular docking to molecular dynamics in exploring ligand-protein recognition process: an overview. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 923.

21. Sousa, S. F.; Ribeiro, A. J. M.; Coimbra, J. T. S.; et al. Protein-ligand docking in the new millennium - a retrospective of 10 years in the field. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 2296-314.

22. Maier, J. A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K. E.; Simmerling, C. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2015, 11, 3696-713.

23. Sun, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, B.; Wang, R. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation decoding molecular mechanism of EDCs binding to hERRγ. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30, 127.

24. Ikhlas, S.; Usman, A.; Ahmad, M. Comparative study of the interactions between bisphenol-A and its endocrine disrupting analogues with bovine serum albumin using multi-spectroscopic and molecular docking studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 37, 1427-37.

25. Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; et al. Gaussian 09 Rev. D.01. 2014. https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=839f33cc-9114-4a55-8f1a-3f1520324ef5. (accessed 17 Dec 2025).

26. Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06 functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Account. 2008, 119, 525.

27. Marenich, A. V.; Cramer, C. J.; Truhlar, D. G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009, 113, 6378-96.

28. Morris, G. M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785-91.

29. Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A. E.; Berendsen, H. J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701-18.

30. Abraham, M. J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1-2, 19-25.

31. Li, A.; Daggett, V. Characterization of the transition state of protein unfolding by use of molecular dynamics: chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91, 10430-4.

32. Essmann, U.; Perera, L.; Berkowitz, M. L.; Darden, T.; Lee, H.; Pedersen, L. G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 8577-93.

33. Kollman, P. A.; Massova, I.; Reyes, C.; et al. Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 889-97.

34. Miller, B. R. 3rd.; McGee, T. D. Jr.; Swails, J. M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A. E. MMPBSA.py: an efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2012, 8, 3314-21.

35. Valdés-Tresanco, M. S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M. E.; Valiente, P. A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: a new tool to perform end-state free energy calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2021, 17, 6281-91.

36. Benninghoff, A. D.; Bisson, W. H.; Koch, D. C.; Ehresman, D. J.; Kolluri, S. K.; Williams, D. E. Estrogen-like activity of perfluoroalkyl acids in vivo and interaction with human and rainbow trout estrogen receptors in vitro. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 120, 42-58.

37. Mu, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Developmental effects and estrogenicity of bisphenol A alternatives in a zebrafish embryo model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3222-31.

38. Ji, B.; Liu, S.; He, X.; Man, V. H.; Xie, X. Q.; Wang, J. Prediction of the binding affinities and selectivity for CB1 and CB2 ligands using homology modeling, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and MM-PBSA binding free energy calculations. ACS. Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 1139-58.

39. Mansouri, K.; Abdelaziz, A.; Rybacka, A.; et al. CERAPP: collaborative estrogen receptor activity prediction project. Environ. Health. Perspect. 2016, 124, 1023-33.

40. Blair, R. M.; Fang, H.; Branham, W. S.; et al. The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands. Toxicol. Sci. 2000, 54, 138-53.

41. Abdulhameed, A. A. R.; Lim, V.; Bahari, H.; et al. Adverse effects of bisphenol A on the liver and its underlying mechanisms: evidence from in vivo and in vitro studies. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8227314.

42. Das, S.; Mukherjee, U.; Biswas, S.; Banerjee, S.; Karmakar, S.; Maitra, S. Unravelling bisphenol A-induced hepatotoxicity: insights into oxidative stress, inflammation, and energy dysregulation. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 362, 124922.

43. Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Tang, Y.; et al. Co-exposure to bisphenol a and arsenic enhance hepatotoxicity in zebrafish by targeting the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and PPAR pathway. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 384, 127037.

44. Mi, P.; Tang, Y. Q.; Feng, X. Z. Acute fluorene-9-bisphenol exposure damages early development and induces cardiotoxicity in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 202, 110922.

45. Zhang, S.; Mi, P.; Luan, J.; Sun, M.; Zhao, X.; Feng, X. Fluorene-9-bisphenol acts on the gut-brain axis by regulating oxytocin signaling to disturb social behaviors in zebrafish. Environ. Res. 2024, 255, 119169.

46. Gu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; et al. Oxidative stress in bisphenol AF-induced cardiotoxicity in zebrafish and the protective role of N-acetyl N-cysteine. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 731, 139190.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].