Health risk assessment of glyphosate exposure among rubber farmers in Northeast Thailand

Abstract

Rubber farmers exposed to herbicides containing glyphosate face significant health risks from occupational exposure. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of health symptoms and their association with glyphosate exposure among rubber farmers in northeast Thailand. A cross-sectional study was conducted to examine the prevalence of health symptoms using a self-report questionnaire. Of 400 participants, 72.8% reported chemical exposure during spraying and 39.3% reported adverse health effects. The most frequent symptom was nasal irritation (18.5%), followed by coughing or shortness of breath and fatigue (3.75%). After adjustment, reporting any adverse health effect was associated with age > 40 years [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 2.02; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.09-3.74; P = 0.025], male sex (aOR = 1.83; 95%CI: 1.19-2.82; P = 0.006), > 10 years’ experience (aOR = 1.53; 95%CI: 1.01-2.31; P = 0.043), and underlying disease (aOR = 1.75; 95%CI: 1.10-2.79; P = 0.019). Unsafe practices and equipment problems were strongly associated with higher odds: self‑application (aOR = 1.97; 95%CI: 1.24-3.13; P = 0.004), leaking equipment (aOR = 2.50; 95%CI: 1.62-3.86; P < 0.001), wet clothing while spraying (aOR = 2.79; 95%CI: 1.78-4.36; P < 0.001), eating during work (aOR = 2.07; 95%CI: 1.30-3.29; P = 0.002), and morning spraying (aOR = 2.88; 95%CI: 1.38-6.03; P < 0.005). The study revealed a high prevalence of health effects among rubber farmers, with the greatest risk magnitude linked to unsafe practices and equipment. Providing personal protective equipment and guiding occupational health and training on chemical handling practices are crucial for effectively reducing these risks.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The rubber tree represents a crucial economic crop in Thailand, with production driven by expanding cultivation areas and favorable climatic conditions. Thailand’s position as one of the world’s largest natural rubber exporters has been strengthened by increasing global demand, particularly from the automotive industry for tire manufacturing. Recent geopolitical factors, including rising crude oil prices, have further enhanced the preference for natural rubber over synthetic alternatives, contributing to sustained growth in Thailand’s rubber sector and reinforcing its significant role in the international market[1].

Thailand dominates global natural rubber production, with smallholder farmers representing approximately 90%-95% of producers and contributing over one-third of world production through an estimated 1.5-2 million farming households[2]. Beyond rubber tapping, cultivation involves various activities including weeding, re-entry operations following pesticide application, and plantation maintenance, all of which increase the likelihood of chemical exposure. Farmers regularly utilize various agrochemicals, including herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, fertilizers, and plant hormones, which are accessible, economical, and employed to improve crop yields. Among these chemicals, glyphosate is imported in substantial quantities and has been linked to potential health risks, with residues detected in urine samples from farmers and their families shortly after application[3]. Approximately 600,000-750,000 tons of glyphosate are consumed each year globally, with usage projected to increase to 740,000-920,000 tons by 2025[4]. However, exposure extends beyond glyphosate alone, as farmers frequently encounter multiple pesticide types. Therefore, this study emphasizes and aims to investigate the specific symptoms primarily caused by glyphosate exposure.

Alarmingly, there have been numerous reports of health issues and fatalities linked to herbicide and fungicide exposure, with 1,886 cases of health complications and 442 deaths recorded between October 2021 and July 2022[5-7]. Glyphosate exposure has been associated with both acute and chronic health effects[8]. Glyphosate exposure has been associated with both acute and chronic health effects. Acute symptoms include eye irritation, skin burns, throat irritation, breathing difficulties, coughing, chest tightness, stomach pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting[3]. Chronic toxicity has more severe implications, affecting the reproductive system (e.g., infertility, sexual dysfunction), the nervous system (e.g., paralysis, Parkinson’s disease), and increasing the risk of certain cancers[9]. For instance, glyphosate exposure is associated with a 5- to 13-fold increased risk of breast cancer and a 41% higher risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma[10]. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified glyphosate as probably carcinogenic to humans, emphasizing its link to non-Hodgkin lymphoma[11]. Glyphosate has also been shown to damage genetic material, elevate oxidative stress, and impair kidney function[3]. Despite extensive global evidence on glyphosate toxicity, limited research has examined rubber farmers in Thailand, particularly regarding how personal, occupational, and behavioral factors interact to influence health risks. We hypothesize that occupational glyphosate exposure and unsafe handling practices among rubber farmers in northeast Thailand are associated with a higher prevalence of specific acute and chronic health symptoms. Addressing these issues is critical for mitigating occupational health risks associated with prolonged chemical exposure in agricultural settings and reducing environmental degradation.

EXPERIMENTAL

Study design and participants

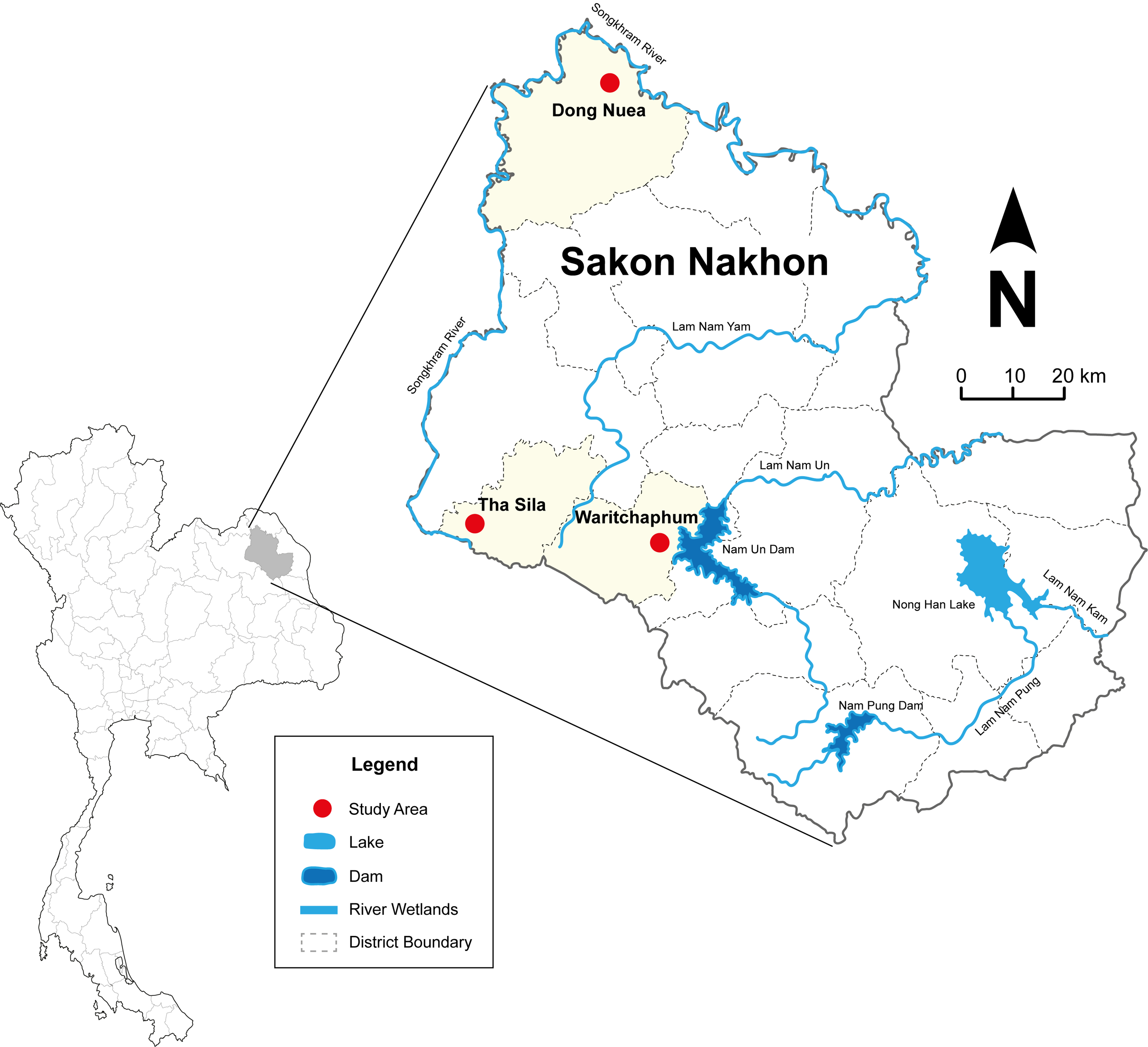

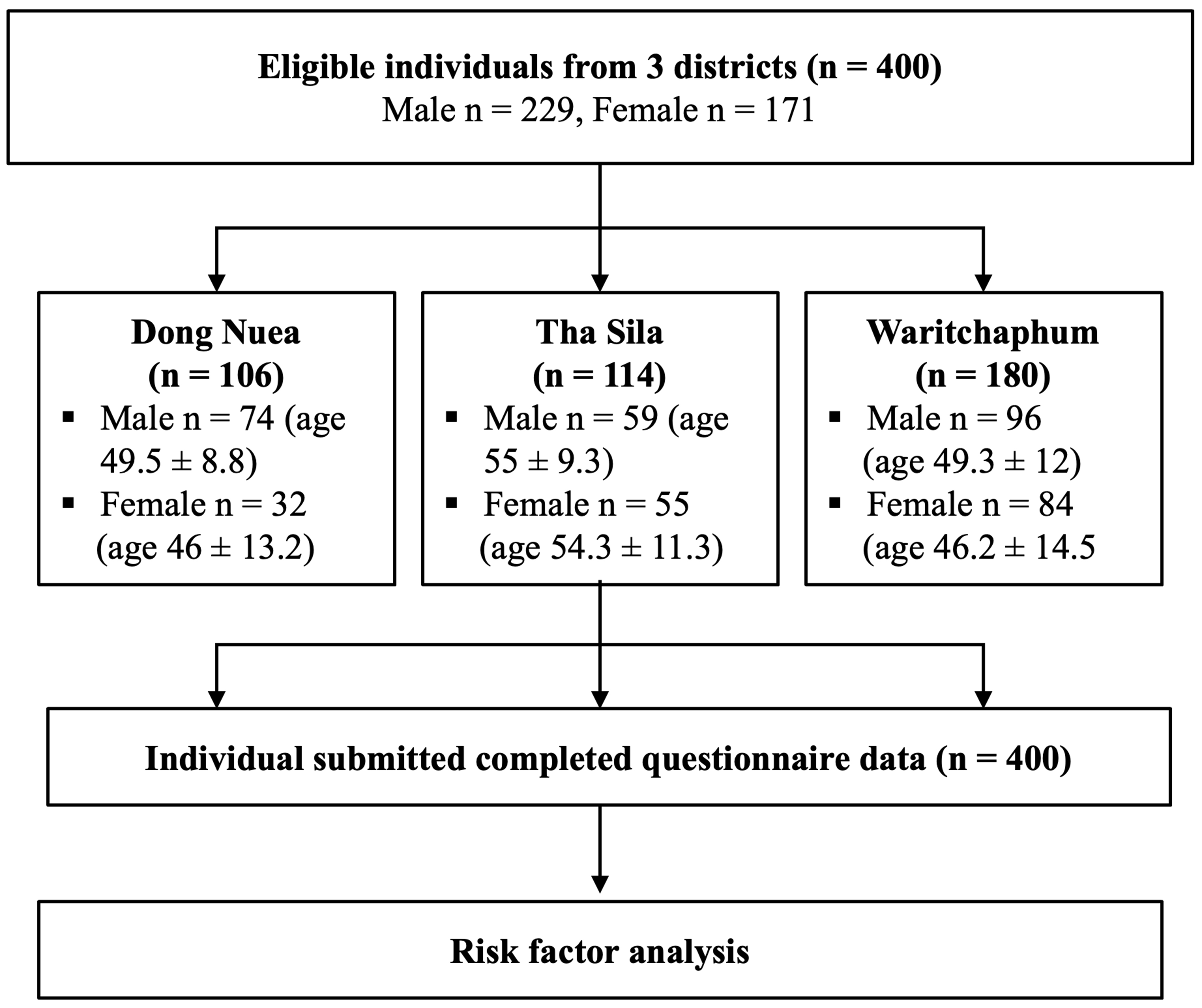

This analytic cross-sectional study was conducted between June and September 2023 in northeast Thailand. Three districts in Sakon Nakhon Province, where rubber trees are extensively cultivated, were selected as the study area, as shown in Figure 1. The sample size was calculated using the formula for population proportion, assuming a moderate risk level of 0.7[12], a 95% confidence interval (CI), and a precision level of 20%. Additional participants were included to account for potential data loss or incomplete responses. A purposive random sampling method was used to recruit 400 rubber farmers from the selected districts. Eligible participants were rubber farmers aged 18 years or older, registered as rubber cultivation households for more than a year, and willing to participate in the study. The selection process is illustrated in Figure 2. If multiple farmers resided in the same household, the farmer who most recently used herbicides was selected. All health volunteers who conducted the interviews received standardized training and followed a structured questionnaire protocol. Participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity, and interviews were conducted individually in a private setting. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Kasetsart University’s accredited Human Ethics Committee (KUREC-CSC66/012). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who voluntarily agreed to participate in the research.

Questionnaire

Demographic information was collected using structured interviews with self-reports to assess health-related issues. Data collection was conducted using a structured questionnaire designed to evaluate pesticide exposure and related health complaints, consistent with approaches applied in recent international studies[13]. The questionnaire was divided into four sections. The first section collected demographic information, including sex, age, education level, work characteristics, experience in rubber planting, cultivation area, underlying diseases, and the use of pain relievers or muscle relaxants after a long workday. The second section focused on information related to glyphosate use, including recent contact with glyphosate, average days of use per month, time spent spraying glyphosate per application, involvement in glyphosate use, personal protective equipment (PPE) usage, equipment leakage during spraying, alcohol consumption, contact with chemicals during spraying, time spent in sprayed areas, wetness of clothing during spraying, and consumption of food or water at the workplace during spraying. The third section gathered information on illnesses or health symptoms occurring after the use or contact with herbicides. The fourth section summarized the preliminary occupational health risk assessment[14].

Risk assessment

The structured approach to assessing glyphosate exposure risks and associated health impacts relied on interview data to evaluate the likelihood of chemical exposure and symptom severity. The probability of exposure was defined by the frequency and duration of glyphosate contact during rubber farming activities, assessed through self-reported application patterns, protective equipment use, and direct contact scenarios (Questions 16-30 in “RESULTS AND DISCUSSION”Section ). Positive responses, indicating reduced exposure risk, were scored as follows: Never/Rarely = 3, Occasionally = 2, and Regularly/Always = 1. Conversely, negative responses, indicating increased exposure risk, are categorized as follows: Never/Rarely = 1, Occasionally = 2, and Regularly/Always = 3. Cumulative scores were classified into three categories: low (15-24 points), medium (25-30 points), and high (31-45 points)[15,16].

Symptom severity was categorized into four groups. Group 1 (no symptoms) included participants who reported no symptoms, injuries, or need for medical care. Group 2 (mild symptoms) included issues such as coughing, nasal irritation, sore or dry throat, difficulty breathing, dizziness, headache, poor sleep quality, itchy or dry skin, cracked skin, skin rash or blisters, burning pain, red or irritated eyes, fatigue, numbness, palpitations, sweating, tearing, excessive salivation, or runny nose. Group 3 (moderate symptoms) encompassed eyelid twitching, blurred vision, chest pain or tightness, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, diarrhea, muscle weakness, cramps, tremors, and unsteady gait. Group 4 (severe symptoms) included seizures, unconsciousness, and coma[15].

The interpretation of health risk levels was determined by multiplying the probability of exposure by the severity level of the symptoms. Risk levels were classified as low, moderate, relatively high, high, or very high. In cases where different risk levels were identified, the higher value was selected to represent the final risk level.

Data analysis

Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used for data analysis. General participant characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, including frequency distributions, percentages, means, standard deviations (SD), and minimum and maximum values. Health symptoms related to pesticide exposure were categorized into four groups for the risk assessment. The relationship between personal characteristics, pesticide exposure factors, and health symptoms was analyzed using multiple logistic regression. The confounders were chosen a priori based on published literature and theoretical framework guidance; variables for the final model were selected through univariate screening (P < 0.05) followed by stepwise regression to address multicollinearity and confounding. The logistic regression model demonstrated adequate fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow test and overall significance with Cox & Snell), indicating satisfactory explanatory power while maintaining model parsimony. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95%CIs were reported to evaluate the strength of the associations. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic information

The analysis of personal factors among the 400 rubber farmers revealed the following: the majority were male (57.2%), with an average age of 49.96 years (SD = 12.09). Most participants had completed at least lower secondary education (59.0%) and were self-employed in farming (77.5%), with 52.0% having 10 years or less of experience. The average cultivation area was 14.39 rai (~5.7 acres), with most farmers cultivating between 6 and 10 rai (~2.4-4.0 acres) (26.5%). A majority of farmers reported no chronic diseases (74.0%) and use of muscle relaxants (74.0%). Regarding chemical use, 82.8% of farmers reported using chemicals in their farming, with 59.0% reporting their last use was over 14 days prior to the survey. Most farmers sprayed chemicals fewer than seven times per month (70.8%), and for 40.5% of participants, each spraying session lasted more than two hours. Spraying primarily occurred in the morning before noon (87.8%). Many farmers were involved in multiple chemical-related activities, such as mixing and spraying or present during spraying (44.8%). While 61.5% reported no use of PPE, 62.3% stated that their spraying equipment did not leak during use. However, 72.8% came into contact with chemicals during spraying, although most did not wear wet clothing (52.2%) or consume food or drinks in the work area (68.8%) [Table 1].

Demographic information of rubber farmers in northeast Thailand (n = 400)

| n (%) | |

| Personal characteristics | |

| Sex n (%) Male Female Age (years), mean ± SD > 40 ≤ 40 Main occupation/work characteristics Own farming Farming (hired) Spraying job Experience in planting rubber (years), n (%) < 10 ≥ 10 Area of cultivation (Rai: 5 Rai ~ 2 Acres), n (%) ≤ 5 6-10 11-20 > 20 Underlying disease, n (%) No chronic diseases Diabetes Hypertension Kidney disease Liver disease Diabetes and hypertension Others (gout, asthma, coronary artery disease, hemorrhoids) Used pain relievers or muscle relaxants after a long day at work, n (%) Yes No | 229 (57.2) 171 (42.8) 49.96 (± 12.09) 337 (84.2) 63 (15.8) 310 (77.5) 39 (9.7) 51 (12.8) 208 (52.0) 192 (48.0) 99 (24.8) 106 (26.5) 134 (3.5) 61 (15.2) 296 (74.0) 41 (10.2) 17 (4.3) 11 (2.8) 2 (0.5) 13 (3.2) 20 (5.0) 296 (74.0) 104 (26.0) |

| Information related to the use of glyphosate | |

| Time spent spraying glyphosate per application < 1 h 1-2 h > 2 h Time of day for glyphosate spraying Morning (before noon) Afternoon (before 6:00 PM) Involvement with glyphosate use Mix chemicals Present during spraying Sprayer More than 1 role PPE usage Yes No Leakage during spraying Yes No Alcohol consumption status, n (%) Yes No Contact with chemicals during spraying Yes No Stay in the area where chemicals are sprayed Yes No Clothing wetness during spraying Yes No Consumption of food/water at workplace (during spraying) Yes No | 124 (31.0) 114 (28.5) 162 (40.5) 351 (87.8) 49 (12.2) 22 (5.5) 162 (40.5) 37 (9.2) 179 (44.8) 154 (38.5) 246 (61.5) 151 (37.8) 249 (62.2) 23 (16.3) 118 (83.7) 291 (72.8) 109 (27.2) 92 (65.24) 49 (34.75) 191 (47.8) 209 (52.2) 125 (31.2) 275 (68.8) |

Health symptoms of rubber farmers

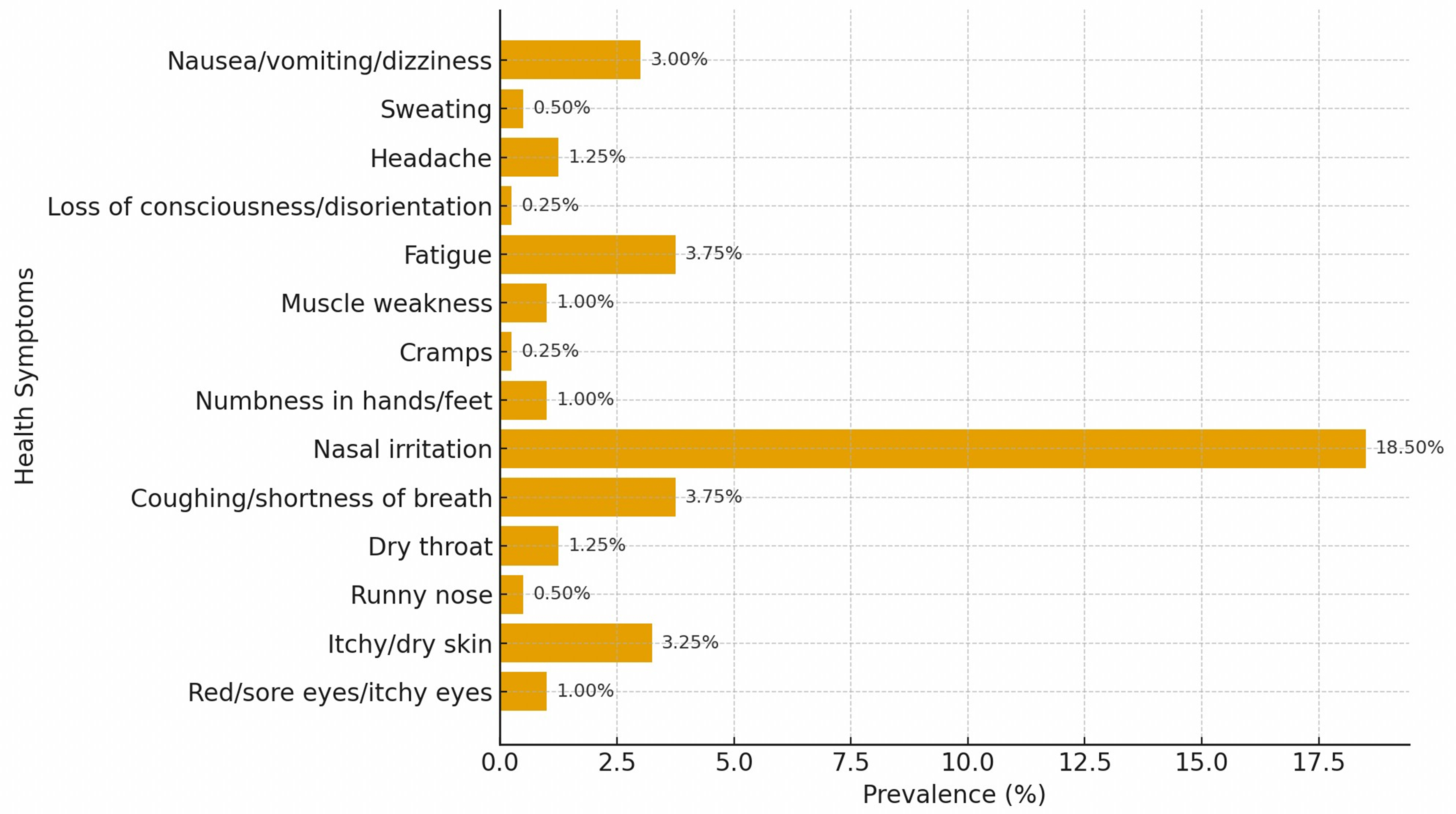

Among the farmers surveyed, 72.8% reported exposure to glyphosate, with 39.3% experiencing adverse health symptoms. The most commonly reported symptoms were nasal irritation (18.5%), coughing or shortness of breath and fatigue (3.75%), itchy or dry skin (3.25%), and nausea, vomiting, or dizziness (3.0%). Less frequently reported symptoms included headache and dry throat (1.25%), muscle weakness, numbness in the hands or feet, and red or itchy eyes (1.0% each), as well as sweating, runny nose (0.5% each), and loss of consciousness, disorientation, and cramps (0.25% each). Symptoms were categorized by body systems. A substantial proportion of farmers reported glyphosate exposure, with nearly 40% experiencing adverse health symptoms primarily affecting the respiratory, dermatological, and general systems, as illustrated in Figure 3. Indicating notable occupational health risks associated with glyphosate use.

Health risk assessment indicating glyphosate exposure among farmers

The health risk assessment classified farmers into four risk levels based on symptom severity and the probability of glyphosate exposure. A majority of farmers (49.5%) were in the low-risk category, showing no symptoms and low exposure scores. Moderate risk was observed in 31.82% of farmers, mainly those reporting mild symptoms with moderate exposure scores. Approximately 13.38% of farmers fell into the moderately high risk category, and 1.26% were classified as high risk, predominantly those with severe symptoms and high exposure scores. The health risk assessment indicates that while the majority of farmers fall into low-to-moderate risk categories, a small proportion experience moderately high to high risk of adverse health effects, reflecting variability in symptom severity and glyphosate exposure among the population [Table 2].

Health risk assessment matrix (n = 400)

| Symptoms (health severity) n (%) | Total score for questions 9-23 (probability of glyphosate exposure) | |||

| Low n (%) | Moderate n (%) | High n (%) | Total n (%) | |

| No symptoms | low 198 (49.50) | Moderate 44 (11.00) | Quite high 1 (0.25) | 243 (60.80) |

| Symptoms G.1 | Moderate 47 (11.75) | Quite high 35 (8.75) | High 4 (1.00) | 86 (21.50) |

| Symptoms G.2 | Quite high 52 (13.00) | High 18 (4.50) | High - | 70 (17.50) |

| Symptoms G.3 | High - | High 1 (0.25) | Very high - | 1 (0.30) |

| Total | 297 (74.30) | 98 (24.50) | 5 (1.25) | 400 (100.00) |

Relationship between personal factors and health symptoms

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, several personal and occupational factors were significantly associated with abnormal health symptoms. Male farmers had higher odds of experiencing symptoms compared to females (aOR = 1.83; 95%CI: 1.19-2.82; P = 0.006). Farmers over 40 years of age were more likely to report symptoms than younger farmers (aOR = 2.02; 95% CI: 1.09-3.74; P = 0.025). Work experience exceeding 10 years (aOR = 1.53; 95%CI: 1.01-2.31; P = 0.043) and cultivating more than 10 rai of land (aOR = 1.54; 95%CI: 1.02-2.34; P = 0.040) were also associated with increased risk. Farmers with pre-existing health conditions had higher odds of symptoms compared to those without (aOR = 1.75; 95%CI: 1.10-2.79; P = 0.019).

Regarding chemical exposure, herbicide use was strongly associated with health symptoms (aOR = 8.51; 95%CI: 3.51-20.63; P < 0.001). Spraying chemicals before noon increased the risk (aOR = 2.88; 95%CI: 1.39-6.03; P = 0.005), as did mixing or spraying chemicals themselves (aOR = 1.97; 95%CI: 1.24-3.13; P = 0.004). Equipment leakage (aOR = 2.50; 95%CI: 1.62-3.85; P < 0.001), wearing wet clothing during spraying (aOR = 2.79; 95%CI: 1.78-4.36; P < 0.001), and consuming food or drink in the work area (aOR = 2.07; 95%CI: 1.30-3.29; P = 0.002) were additional risk factors. In contrast, consistent use of PPE was protective, reducing the odds of symptoms (aOR = 0.64; 95%CI 0.42-0.99; P = 0.043). These multivariable results show that older age, male sex, longer work experience, larger cultivated area, and pre-existing health conditions independently increase the likelihood of reporting adverse health symptoms, identifying vulnerable subgroups for targeted monitoring and prevention [Table 3].

Relationship between personal factors and health symptoms in farmers exposed to glyphosate in rubber farmers in Sakon Nakhon Province, Thailand (n = 400)

| Factors | No. of examined | Health symptoms, n (%) | cOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Yes | No | ||||

| Sexb | |||||

| Male | 229 | 104 (45.4) | 125 (54.6) | 1.85 (1.22, 2.81) | 1.83** (1.19, 2.82) |

| Female | 171 | 53 (31.0) | 118 (69.0) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Age (years)b | |||||

| > 40 | 337 | 140 (41.5) | 197 (58.5) | 1.92 (1.06, 3.49) | 2.02* (1.09, 3.74) |

| ≤ 40 | 63 | 17 (27.0) | 46 (73.0) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Work experience (in years)b | |||||

| > 10 | 164 | 74 (45.1) | 90 (54.9) | 1.52 (1.01, 2.28) | 1.53* (1.01, 2.31) |

| ≤ 10 | 236 | 83 (35.2) | 153 (64.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Area of cultivation (Rai: 5 Rai ~ 2 Acres), n (%)c | |||||

| > 10 | 195 | 87 (44.6) | 108 (55.4) | 1.55 (1.04, 2.23) | 1.54* (1.02, 2.34) |

| ≤ 10 | 205 | 70 (34.1) | 135 (65.9) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Underlying disease, n (%)a | |||||

| Yes | 104 | 50 (48.1) | 54 (51.9) | 1.64 (1.04, 2.57) | 1.75* (1.10, 2.79) |

| No | 296 | 107 (36.1) | 189 (63.9) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Chemical herbicide usagea | |||||

| Yes | 331 | 151 (45.6) | 180 (54.4) | 8.81 (3.71, 20.92) | 8.51*** (3.51, 20.63) |

| No | 69 | 6 (8.7) | 63 (91.3) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Time spent spraying herbicides per application (hours)a | |||||

| > 2 | 157 | 72 (44.4) | 85 (35.7) | 1.44 (0.96, 2.17) | 1.39 (0.90, 2.13) |

| ≤ 2 | 243 | 153 (64.3) | 90 (55.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Time of day for herbicide sprayinga | |||||

| Morning before noon | 351 | 146 (41.6) | 205 (58.4) | 2.46 (1.22, 4.97) | 2.88** (1.38, 6.03) |

| Afternoon before 6:00 PM | 49 | 11 (22.4) | 38 (77.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Involvement with herbicide usea | |||||

| Sprayer or mix chemicals | 238 | 111 (46.6) | 127 (53.4) | 2.20 (1.44, 3.38) | 1.97** (1.24, 3.13) |

| Present during spraying | 162 | 46 (28.4) | 116 (71.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| PPE usagea | |||||

| Yes | 154 | 82 (53.2) | 72 (46.8) | 0.60 (0.40, 0.91) | 0.64* (0.42, 0.99) |

| No | 246 | 161 (65.4) | 85 (34.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| While spraying, use a leaking chemical containera | |||||

| Yes | 151 | 80 (53.0) | 71 (47.0) | 2.52 (1.66, 3.82) | 2.50*** (1.62, 3.86) |

| No | 249 | 77 (30.9) | 172 (69.1) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Pesticide exposure while workinga | |||||

| Yes | 291 | 127 (43.6) | 164 (56.4) | 2.04 (1.26, 3.30) | 2.03** (1.22, 3.39) |

| No | 109 | 30 (27.5) | 79 (72.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Clothes soaked with pesticidesa | |||||

| Yes | 191 | 100 (52.4) | 91 (47.6) | 2.93 (1.93, 4.44) | 2.79*** (1.78, 4.36) |

| No | 209 | 57 (27.3) | 152 (72.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Consume food and drinks in the workplacea | |||||

| Yes | 125 | 65 (52.0) | 60 (48.0) | 2.16 (1.40, 3.32) | 2.07** (1.30, 3.29) |

| No | 275 | 92 (33.5) | 183 (66.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

Discussion

The present study identified significant health risks associated with glyphosate exposure among rubber farmers. A key finding was the prevalence of self-reported health symptoms, with 39.3% of farmers reporting adverse effects. The present study identified significant health risks associated with glyphosate exposure among rubber farmers. A key finding was the prevalence of self-reported health symptoms, with 39.3% of farmers reporting adverse effects. The most common symptoms included nasal irritation (18.5%), coughing or shortness of breath and fatigue (3.75%), itchy or dry skin (3.25%), nausea, vomiting, or dizziness (3.0%), and less frequent symptoms such as headache and dry throat (1.25%), and muscle weakness (1.0%). Acute glyphosate exposure has been shown to cause skin and eye irritation (e.g., burning sensations), respiratory distress (e.g., coughing, chest tightness), gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), and kidney dysfunction. These findings show notable differences compared to previous research conducted in Nakhon Sawan, Thailand, which reported substantially higher symptom rates among glyphosate sprayers, including sweating (98.0%), dizziness (92.1%), fatigue (79.4%), and skin rashes (56.9%)[3]. The considerably lower symptom prevalence in our study may be attributed to differences in exposure intensity, application methods, protective equipment usage, or study populations. While the Nakhon Sawan study focused specifically on pesticide sprayers who likely experienced direct and concentrated exposure, our study included a broader population of rubber farmers with varying levels of glyphosate contact. Additionally, the specific symptoms most frequently reported differed between studies, with nasal irritation being predominant in our population vs. systemic symptoms such as sweating and dizziness in the Nakhon Sawan study, suggesting potentially different exposure patterns or individual susceptibility factors. Additionally, evidence from other studies highlights glyphosate's impacts on the gut-brain axis, immune-neurological systems, and multiple organ toxicity[17].

The IARC classifies glyphosate as a Group 2A substance, probably carcinogenic to humans, due to its potential to damage genetic material and its links to non-Hodgkin lymphoma[18]. The findings of this study also align with earlier research on hazardous agricultural chemicals, such as glyphosate, which have been associated with adverse effects on the central nervous system, including disrupted neural transmission and significant short- and long-term health impacts[19].

The risk assessment identified 1.26% of farmers as high risk, 13.38% as moderately high risk, 31.82% as moderate risk, and 49.5% as low risk. These findings are consistent with a study on glyphosate exposure among knapsack sprayers, where most participants were at low risk (69.1%)[20]. Similarly, research on paraquat exposure indicated that a substantial proportion of sprayers were at high risk, with 23.3% experiencing health impacts[21].

The current study found that the use of PPE significantly reduced the likelihood of abnormal health symptoms by 0.64 times (aOR = 0.64; 95%CI: 0.42-0.99; P = 0.043). These results align with global research from Malaysia, Uganda, and the United Kingdom, which demonstrated that PPE reduces exposure to chemicals such as pyrethroids and glyphosate[21]. However, factors such as heat and insufficient training often hinder consistent PPE usage. Wearing clean, long-sleeved protective clothing and gloves during chemical handling has been shown to lower skin exposure to chemicals including chlorpyrifos and glyphosate[16-18,21-23], as well as to reduce urinary glyphosate concentrations in farmers[15-17].

Farmers who mixed and applied chemicals themselves had nearly double the odds of experiencing abnormal symptoms compared to those who only entered treated areas (aOR = 1.97; 95%CI: 1.24-3.13; P = 0.004). These findings are consistent with studies linking inadequate PPE use during pesticide mixing and spraying to acute pesticide poisoning (APP)[18-20]. Poor safety practices, such as handling chemicals directly without sufficient protection, further exacerbate the risk of health symptoms, including headaches, dizziness, and nausea, which have been widely reported among farmworkers in Thailand and other regions.

The study identified seven key factors independently associated with health symptoms, even after adjusting for confounders. These included age, gender, work experience, pre-existing health conditions, cultivation area, chemical pesticide use, equipment leakage during spraying, pesticide exposure while working, wearing pesticide-soaked clothing, and consuming food or drinks in the workplace.

Male farmers had 1.83 times higher odds of experiencing abnormal symptoms compared to females (aOR = 1.83; 95%CI: 1.19-2.82; P = 0.006), which is consistent with reports[9,21] highlighting the higher risks faced by men in agricultural work due to their involvement in high-contact activities, such as pesticide spraying and equipment handling[23]. Farmers aged over 40 were 2.02 times more likely to report health symptoms than younger farmers (aOR = 2.02; 95%CI: 1.09-3.74; P = 0.025). This may be due to prolonged cumulative exposure to glyphosate, which can be absorbed through ingestion, inhalation, and skin contact. Although absorption through intact skin is low (< 3%), it increases significantly with compromised skin, rising to up to five times higher[24]. Farmers with pre-existing health conditions also demonstrated a higher risk of abnormal symptoms, with 1.75 times greater odds compared to those without such conditions (aOR = 1.75; 95%CI: 1.10-2.79; P = 0.019). These findings are supported by studies among sugarcane farmers in Thailand, which showed a significant association between chronic diseases and health impacts from pesticide use[25]. Glyphosate’s systemic effects may exacerbate chronic symptoms when combined with other health vulnerabilities, emphasizing the need for targeted protective measures and regular health monitoring[8].

Farmers with extensive work experience may become complacent about safety measures, reducing protective behaviors and increasing their risk of exposure to harmful chemicals[26]. These findings align with international studies emphasizing the cumulative effects of chemical exposure in long-term agricultural work. For instance, occupational health studies have documented increased risks of respiratory, dermatological, and neurological symptoms in farmers with prolonged exposure to pesticides and other chemicals[27]. However, this contrasts with another study[28], which found that farmers with over 10 years of spraying experience reported fewer symptoms, potentially due to improved safety practices developed over time.

Farmers managing larger cultivation areas (> 4 acres) had 1.54 times higher odds of experiencing abnormal symptoms compared to those with smaller plots. Larger farms often require more extensive chemical inputs and labor, increasing exposure risks. Studies have shown that extended pesticide use and workload, frequently associated with larger farms, are significant risk factors for health issues, including abnormal symptoms and stress[28,29]. These findings suggest that managing larger farms not only amplifies exposure to hazardous substances but also exacerbates physical and mental health risks due to the increased workload.

Farmers using herbicides were found to have 8.51 times higher odds of experiencing symptoms compared to those who did not use chemicals. While this finding demonstrates a strong association between herbicide use and health symptoms, it should be noted that our study did not capture detailed dose-response relationships or exposure intensity variables such as application frequency, duration of exposure, or cumulative lifetime exposure. This represents an important limitation, as research has demonstrated that people exposed for a prolonged or high-intensity time period, particularly agricultural workers, are more likely to experience long-term health effects[29]. Furthermore, dose-response relationships may sometimes deviate from a linear increase in the frequency and severity of impacts expected as dose levels rise[30]. Improper herbicide handling, prolonged exposure, and insufficient PPE usage significantly increase the risk of acute symptoms (e.g., headaches, nausea, and respiratory irritation) and long-term effects such as cancer and neurological disorders[31]. Research has also documented adverse effects of herbicide exposure, ranging from skin irritation to systemic toxicity[32]. Additionally, a phenomenological study involving 20 agricultural workers in rural Thai communities highlighted the health risks associated with prolonged agrochemical exposure, revealing the direct relationship between unsafe practices and increased health risks[33].

Several limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the study relied on self-reported data collected during interviews, which may introduce recall bias and affect the validity of the findings. Self-reported symptoms may be influenced by social desirability bias, despite interview privacy measures. Secondly, the study did not include measurements of glyphosate levels in the blood or urine of participants due to limited laboratory resources in Thailand. Future studies should incorporate biomarker testing to provide more direct evidence of glyphosate exposure and its health effects. This could complement questionnaire-based data and improve predictions of health impairments associated with glyphosate exposure. Third, this study focused on glyphosate exposure, but farmers may have been exposed to other pesticides or environmental factors (e.g., soil contamination, water quality) that could confound the observed associations with health symptoms. Although the logistic regression model adjusted for key personal and occupational factors, residual confounding from unmeasured exposures cannot be ruled out. Finally, as a cross-sectional study, this research can only identify associations between glyphosate exposure and health symptoms but cannot establish causal relationships. Longitudinal studies are recommended to assess the long-term effects of glyphosate exposure and to confirm causality in health outcomes.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the significant occupational health risks faced by rubber farmers due to glyphosate exposure, with nearly 40% of participants reporting adverse health symptoms. These findings underscore the urgent need for preventive measures, such as consistent use of PPE, training on safe pesticide handling, integrated weed management, and regular health monitoring for agricultural workers. The findings support the need for stricter regulations and national guidelines on pesticide use and safe handling. Implementing these measures will help protect farmers’ health, lower healthcare burdens, and promote sustainable agriculture.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

This research on glyphosate exposure among rubber farmers in Sakon Nakhon Province, Thailand, was supported by many individuals and institutions. We are grateful to my advisors for their guidance, the professors who reviewed the research tools, and the community leaders and health volunteers who assisted with data collection. I also thank the Faculty of Public Health and Kasetsart University for their support and resources.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: Kammoolkon, R.; Chaiyasarn, P.; Kopolrat, K. Y.

Performed data acquisition and provided administrative, technical, and material support: Srichaijaroonpong, S.; Yasaka, P.; Hardthakwong, B.; Suwannaboon, P.; Krueakaew, C.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Human Resource Development Grant (Code No. 2023/3-3, 3 August 2023) from Kasetsart University, Thailand, designated for publication in a national academic journal.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Ethics Committee of Kasetsart University (KUREC-CSC66/012, Bangkok, Thailand). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who voluntarily agreed to participate in the research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Sowcharoensuk, C. Industry outlook 2022-2024: natural rubber. 2022. https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/industry/industry-outlook/agriculture/rubber/io/rubber-2022. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

2. Nicod, T.; Bathfield, B.; Bosc, P. M.; Promkhambut, A.; Duangta, K.; Chambon, B. Households’ livelihood strategies facing market uncertainties: how did Thai farmers adapt to a rubber price drop? Agric. Syst. 2020, 182, 102846.

3. Khangkhun, P.; Kongtip, P.; Nankongnab, N.; Sujirarat, D.; Pengpumkiat, S. Urinary glyphosate concentration of sprayers in Nakhon Sawan Province, Thailand. Dis. Control. 2020, 46, 516-27.

4. Costas-Ferreira, C.; Durán, R.; Faro, L. R. F. Toxic effects of glyphosate on the nervous system: a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4605.

5. Narksoon, S.; Junwin, B. Factors related to cholinesterase levels in the blood of farmers Ban Ai Khu Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital District Phrom Khiri District Nakhon Si Thammarat Province. Health. Sci. J. Thai. 2025, 7, 25-33.

6. National Health Security Office (NHSO). The NHSO opposes delaying the ban on three agricultural chemicals, revealing over 15,000 cases of chemical poisoning in the past five years. 2018. https://www.nationthailand.com/in-focus/30354068. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

7. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH Pocket Guide to chemical hazards. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2005-149, 2007. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2005-149/pdfs/2005-149.pdf. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

8. Galli, F. S.; Mollari, M.; Tassinari, V.; et al. Overview of human health effects related to glyphosate exposure. Front. Toxicol. 2024, 6, 1474792.

9. Klátyik, S.; Simon, G.; Takács, E.; et al. Toxicological concerns regarding glyphosate, its formulations, and co‑formulants as environmental pollutants: a review of published studies from 2010 to 2025. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 3169-203.

10. Zhang, L.; Rana, I.; Shaffer, R. M.; Taioli, E.; Sheppard, L. Exposure to glyphosate-based herbicides and risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis and supporting evidence. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2019, 781, 186-206.

11. Marino, M.; Mele, E.; Viggiano, A.; et al. Pleiotropic outcomes of glyphosate exposure: from organ damage to effects on inflammation, cancer, reproduction and development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12606.

12. Onmoy, P.; Aungudornpukdee, P. Health impact assessment and self-prevention behavior from pesticide use among shallot farmers in Chai Chumphon Sub-district, Laplae District, Uttaradit Province. Community. Dev. Qual. Life. J. 2016, 4, 417-28. https://search.asean-cites.org/article.html?b3BlbkFydGljbGUmaWQ9MTc3NzE3. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

13. Venugopal, D.; Beerappa, R.; Chauhan, D.; et al. Occupational health complaints and demographic features of farmers exposed to agrochemicals during agricultural activity. BMC. Public. Health. 2025, 25, 2416.

14. Pengpan, R.; Kopolrat, K. Y.; Srichaijaroonpong, S.; Taneepanichskul, N.; Yasaka, P.; Kammoolkon, R. Relationship between pesticide exposure factors and health symptoms among chili farmers in Northeast Thailand. J. Prev. Med. Public. Health. 2024, 57, 73-82.

15. Division of occupational and environmental diseases. Farmer’s work risk assessment form from pesticide exposure. J. Sci. Technol. 2014. https://ayo.moph.go.th/sanitation/file_upload/subblocks/2557/58_%E0%B9%81%E0%B8%9A%E0%B8%9A%E0%B8%9B%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B0%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%84%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A1%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%AA%E0%B8%B5%E0%B9%88%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%87%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%A9%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%A3_%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%9A%E0%B8%81_1_56.pdf. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

16. Boonkhao, L.; Baukeaw, W.; Saenrueang, T.; Rattanachaikunsopon, P. Factors influencing the level of health risks from pesticide exposure among vegetable farmers. Sci. Eng. Health. Stud. 2023, 17, 23050006.

17. Mazuryk, J.; Klepacka, K.; Kutner, W.; Sharma, P. S. Glyphosate: impact on the microbiota-gut-brain axis and the immune-nervous system, and clinical cases of multiorgan toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environm. Saf. 2024, 271, 115965.

18. World Health Organization. Evaluation of five organophosphate insecticides and herbicides. IARC Monographs, 2015. https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/MonographVolume112-1.pdf. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

19. Department of Occupational and Environmental Diseases. Ministry of Public Health. Study on the impact of hazardous chemicals used in agriculture (glyphosate) and the costs of health rehabilitation for at-risk groups and patients affected by agricultural chemicals. 2022. (in Thai) https://ddc.moph.go.th/uploads/publish/1388720230220111053.pdf. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

20. Chaiklieng, S.; Uengchuen, K. Human exposure to glyphosate and methods of detection: a review. Walailak. J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17.

21. Andrade-Rivas, F.; Rother, H. A. Chemical exposure reduction: factors impacting on South African herbicide sprayers’ personal protective equipment compliance and high risk work practices. Environ. Res. 2015, 142, 34-45.

22. Callahan, B. J.; McMurdie, P. J.; Holmes, S. P. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. ISME. J. 2017, 11, 2639-43.

23. Hyland, C.; Meierotto, L.; Castellano, R. S.; Curl, C.; Ruiz, I. Pesticide exposure and risk perceptions among men and women Latinx farmworkers in Idaho. 2022. https://www.boisestate.edu/agriculturalhealth/pesticide-exposure-and-risk-perceptions-among-male-and-female-latinx-farmworkers/summary-report/. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

24. Sutthiloh, S.; Sapbamroe, R. Effects of glyphosate on oxidative stress in experimental animals and humans. J. Med. Health. Sci. 2018, 25, 97-114. https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jmhs/article/view/142946. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

25. Suwunnakhot, M. Prevalence and factors associated with blood cholinesterase enzyme safety levels among farmers under the implementation on development quality of life levels at Khong Chai district, Kalasin province. J. Med. Public. Health. Ubon. Ratchathani. Univ. 2024, 7, 25-35.

26. Remoundou, K.; Brennan, M.; Hart, A.; Frewer, L. J. Pesticide risk perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes of operators, workers, and residents: a review of the literature. Hum. Ecol. Risk. Assess. 2014, 20, 1113-38.

27. Sakorsormuang, P.; Kaewboonchoo, O.; Ross, R.; Boonyamalik, P. Working hazards and health problems among rubber farmers in Thailand. Walailak. J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 222-36.

28. Uengchuen, K.; Chaiklieng, S. Health risk assessment and factors correlated with adverse symptom of glyphosate sprayer in Khon Kaen Province. J. Safe. Health. 2020, 13, 61-70. (in Thai) https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JSH/article/download/223242/165229/849085. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

29. Adeyinka, A.; Muco, E.; Regina, A. C.; Pierre, L. Organophosphates(Archived). In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499860/. (accessed 19 Jan 2026).

30. Peillex, C.; Pelletier, M. The impact and toxicity of glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides on health and immunity. J. Immunotoxicol. 2020, 17, 163-74.

31. Sun, H.; Hurley, T.; Frisvold, G. B.; et al. How does herbicide resistance change farmer’s weed management decisions? Evidence from the roundup ready experiment. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2720.

32. Andert, S.; Ziesemer, A. Analysing farmers’ herbicide use pattern to estimate the magnitude and field-economic value of crop diversification. Agriculture 2022, 12, 677.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].