Particle deposition in the human lung as a function of microplastics’ shape, size, orientation, and type

Abstract

The widespread use and poor management of single-use plastics have created a global pollution issue with emerging human health concerns. Environmental degradation of plastics produces micro- and nanometer-sized particles that may become airborne and inhaled. While some are removed by lung defenses, others persist and trigger inflammation or toxic effects, including reproductive harm, carcinogenicity, and mutagenicity. Because airborne microplastics are often fibrous, this study focuses on how size, shape, and orientation influence their deposition. Deposition fractions of microplastic fibers in different regions of the human lung were estimated using the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) deposition model, with adjustments for fiber geometry, density, and orientation through aerodynamic and volume-equivalent diameters. Fiber lengths of

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Plastics, first developed in the early 20th century and widely adopted after the 1950s, have become indispensable in packaging, storage, and daily life. Their durability, while advantageous for utility, poses major challenges for waste management, as global production and disposal trends raise critical sustainability concerns[1-4]. During degradation, plastics fragment into microplastics - particles smaller than 5 mm - classified as primary (intentionally produced) or secondary (formed through environmental breakdown)[5]. Microplastics originate from mismanaged waste, tire wear, and textile fibers and are now pervasive in terrestrial and atmospheric environments[6-8]. Growing attention has focused on their potential health impacts, particularly from inhaled airborne microplastics, which are abundant indoors and predominantly fibrous[9-16].

Health effects from inhaled microparticles depend strongly on particle size, typically characterized by the aerodynamic equivalent diameter (da) - the diameter of a unit-density sphere (1 g/cm3) that settles at the same velocity as the particle. Aerodynamic rather than geometric size governs inhalation potential[17,18]. Particles larger than 10 µm are deposited mainly in the upper airways, PM10 (≤ 10 µm) can reach the bronchioles, and finer fractions such as PM2.5 (≤ 2.5 µm) or ultrafine particles (≤ 0.1 µm) can penetrate the alveolar region[9,19]. Owing to their high surface-to-volume ratio, smaller particles interact more readily with biological surfaces, eliciting stronger cellular and tissue-level responses[20].

Beyond particle size, morphology critically influences microplastic toxicity by affecting interactions with biological structures. Microfibers behave differently from microspheres, fragments, or films[21], suggesting shape-specific toxicological effects. Elongated particles such as fibers or thin plates pose greater concern because their geometry enhances interception as a deposition mechanism, especially when oriented perpendicular to airflow. Although most inhalation studies have focused on spherical particles, several highlight the importance of particle shape and orientation in deposition dynamics[22].

The surface charge of microplastics further modulates toxicity. The ζ-potential, representing surface charge[23], serves as a proxy for particle-cell interactions[24]. Strongly charged particles exhibit greater adhesion to cellular membranes, increasing bioavailability and potentially amplifying toxic responses. Although current data on ζ-potential effects are limited, they underscore the need to incorporate surface charge into mechanistic models of particle–cell interactions.

Despite increasing recognition of airborne microplastics as an emerging health concern, understanding of their deposition and fate in the respiratory tract remains limited. Most studies emphasize spherical morphologies, even though environmental airborne microplastics are primarily fibrous. The effects of particle orientation and polymer density on deposition remain poorly characterized. Moreover, available data are largely derived from theoretical models that fail to capture the variability in microplastic size, shape, and surface chemistry observed under real-world conditions. Empirical evidence, while growing, remains insufficient to validate model predictions or clarify how physicochemical parameters such as size, density, orientation, and surface charge influence deposition, persistence, and toxicity.

Key physicochemical attributes including size, shape, surface charge, bio-persistence, and adsorbed contaminants or pathogens likely determine the toxicological potential of airborne microplastics[9,25]. Yet, the contribution of each factor to adverse health outcomes remains poorly defined, as only a few studies have examined these interactions systematically[26]. Addressing these gaps requires integrative approaches that account for the combined influence of geometry, material properties, and aerodynamic behavior on particle transport and lung deposition. Collectively, the composition, size, orientation, and morphology of plastic fibers shape their aerodynamic properties and ultimately govern their inhalation, retention, and potential for toxicity in the human respiratory tract.

Accordingly, the present study was designed to address these knowledge gaps by:

1. Modeling lung deposition patterns of microplastic fibers across different regions of the respiratory tract (nasopharyngeal, tracheobronchial, and alveolar) using the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) framework.

2. Assessing the influence of fiber dimensions (length and diameter) on deposition efficiency, with emphasis on respirable fractions relevant to human exposure.

3. Evaluating the impact of fiber orientation (parallel, perpendicular, and random) on deposition outcomes to quantify orientation-dependent variability.

4. Comparing deposition profiles among various polymer types - polystyrene (PS), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) - to determine the effect of density and physicochemical characteristics.

5. Identifying implications of deposition patterns for clearance and toxicity, particularly concerning frustrated phagocytosis, inflammatory potential, and persistence in the alveolar region.

Given the theoretical nature of the modeling approach, uncertainty arises from assumptions regarding particle geometry, density, and orientation, all of which exhibit high variability in environmental samples. Sensitivity analysis indicates that deposition outcomes are particularly influenced by fiber diameter and aerodynamic diameter, with small variations in these parameters producing significant changes in predicted regional deposition. Additional uncertainty results from the assumption of random orientation and the use of literature-derived size distributions, which may not reflect the full heterogeneity of real-world airborne microplastics.

These limitations underscore the need for experimental validation and refinement of model parameters. Controlled inhalation studies and advanced imaging of fiber deposition are essential to bridge the gap between theoretical predictions and actual exposure scenarios. A systematic understanding of how microplastic fibers interact with respiratory structures will provide critical insights into their potential health impacts and inform future risk assessment frameworks for airborne microplastics.

EXPERIMENTAL

Aerosol particle diameter can be defined in several ways, depending on particle shape, density, and the external forces acting upon the particle[27]. Commonly used measures include geometric, aerodynamic, volume-equivalent, mobility, optical, and Stokes diameters; however, for the present analysis, emphasis is placed on the aerodynamic diameter and the volume-equivalent diameter. The aerodynamic diameter is defined as the diameter of a unit-density sphere that settles through air at the same velocity as the particle under consideration, whereas the volume-equivalent diameter refers to the diameter of a sphere possessing the same volume as the particle. Deposition fraction - defined as the proportion of inhaled aerosol particles that deposit within a specific region of the respiratory tract at a given particle diameter (dp, µm) - is estimated using simplified equations for average exercise levels fitted to the ICRP model. The inhalable fraction (IF) is calculated using[27]

where dp is the particle diameter in microns.

The expressions for deposition fraction (DF) across different regions of the respiratory tract, corresponding to the head airways (HA), tracheobronchial region (TB), alveolar region (AL), as well as the total deposition, are respectively given as[27]

Equations (1-4) were originally derived for spherical particles of unit density but can be extended to other particle types by applying the aerodynamic diameter for particles larger than 0.5 µm, and the physical or volume-equivalent diameter for particles smaller than 0.5 µm.

The equivalent aerodynamic diameter of fibers can be calculated based on[28]

Here, da denotes the aerodynamic diameter, de the volume-equivalent diameter, ρ0 the unit density of a reference particle (1 g/cm3), ρp the density of the microplastic particle, and χ the dynamic shape factor. The value of χ depends not only on particle size and geometry but also on orientation within the airflow. For example, fibers aligned parallel to the flow exhibit the largest effective da, whereas those oriented perpendicular to the flow yield the smallest equivalent diameter.

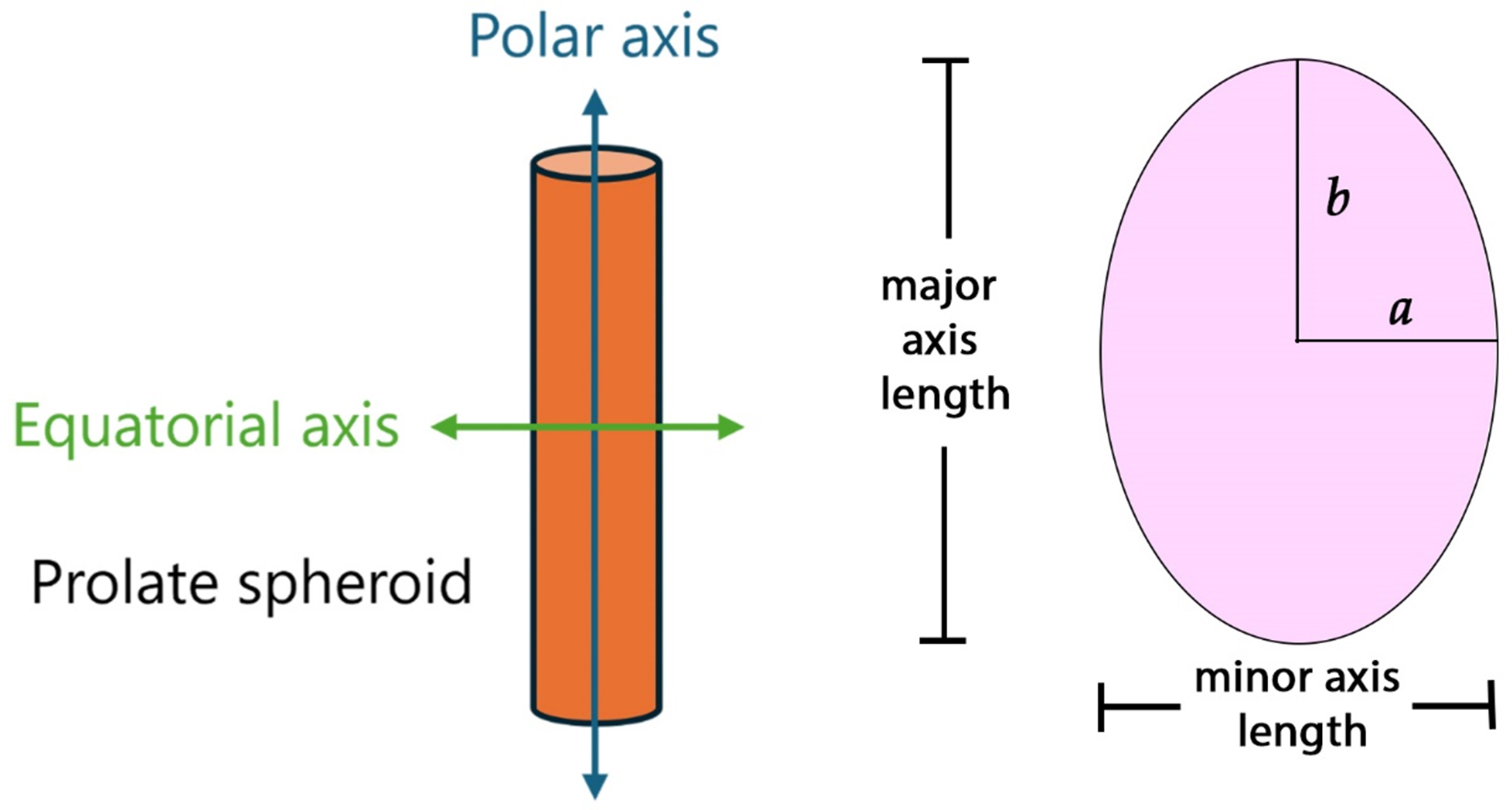

The theory of ellipsoids in creeping motion[29] offers important insight into how particle shape and orientation influence the drag of nonspherical aerosol particles, as the ellipsoidal form can vary continuously from disk-like through spherical to rod-like geometries. In particular, ellipsoids with two equal equatorial axes allow for analytical expressions of the shape factor in the two principal orientations of motion relative to the surrounding fluid[30,31]: κ⊥ (normal) and κ// (parallel) to the polar axis. The corresponding equations for spheroids can be expressed as functions of the axis ratio (q)[32], as illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows the parallel and perpendicular orientation of the particle as it relates to modeling the deposition in the human lung.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of rods or fibers as prolate spheroids. The illustration shows both the polar axis and equatorial axis which are used in Equations (6-8).

For rods (q > 1), the shape factors are defined as:

The two branches, κ⊥ and κ//, correspond to the orientations of maximum and minimum drag, respectively, and exhibit a reciprocal relationship for needle-like and disk-like particles with respect to the orientation of their long axis. As is expected, the orientation of the particle, parallel or perpendicular, cannot be determined as it moves through the airways. For a prolate spheroid with random orientation in air, the dynamic shape factor is denoted as κr, which can be expressed as[30]:

By combining microplastic density, particle shape, random orientation, and particle length and diameter, the influence of these parameters on regional and total lung deposition was determined. The model parameters used in this analysis were based on particle length and diameter ranges relevant to microplastics sampled in ambient air. The available literature was reviewed to identify studies that had sampled and characterized microplastics in ambient air, providing key information on their composition, size, and shape. Table 1 summarizes the microplastics detected and measured in ambient air, focusing on those that are fibrous in nature. It provides insight into the distinct types of polymers identified in aerosolized microplastics, along with their lengths, widths (when available), and shapes. The data summarized in Table 1 served as the basis for defining the range of lengths and diameters used in the model. Commonly reported polymer types include acrylates (ACR), acrylic (AC), butadiene rubber (BR), chlorinated polyethylene (CPE), ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA), PET, PMMA, PVC, polyester (PES), PS, PE, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), polyurethane (PUR), polyamide (PA), PP, and silicone (SIL). Although large upper bounds are detected for both length and width [Table 1], the lower limits of these ranges were selected for the model. This is because it is expected that smaller fibers present a greater inhalation and toxicity hazard than larger fibers.

Summary of aerosol microplastics with composition, length and width

| Polymer type of the particle | Shape of the assessed particle(s) | Measured length of the particle (µm) | Measured width of the particle (µm) | Ref. |

| PP, PET | Fibers, fragments, films | 12-2,475 | 4-88 | [33] |

| PP, PET, PS, PVC, PTFE, CPE, PE, ACR, EVA, BR, PUR, SIL | Fibers | Not reported | 20-100 | [34] |

| PE, PET, AC, phenoxy resin, rayon | Fibers (> 20 μm) | Up to 1,750 | Up to 34.29 | [35] |

| Composition not reported | Fibers | 200-400 and 400-600 | 7-15 | [36] |

| PS, PP, PET, PUR, PVC | Fibers | 400-500 | 17 ± 2 | [25] |

| PE, PET, PES, PA, PVC | Fibers | > 50 μm | 17 ± 4 | [37] |

| PE, PAN, PET, PMMA, PA | Fibers | Not reported | 11-20 | [38] |

In addition to the data presented in Table 1, previous studies have reported microplastic fibers ranging in length from less than 20 µm to as much as 5 mm[14,16,39], with most falling within a range of 100-700 µm[14,40]. However, these reported size distributions are strongly influenced by the sampling techniques and analytical detection limits employed, which often complicates accurate quantification of atmospheric contamination by microscopic particles[41]. To account for the unpredictable and enormous size range of microplastic particles, fibers with lengths of 10-50 µm and diameters of 0.75-5 µm were selected for the model. These dimensions were selected based on reported ranges of airborne microplastics, with particular emphasis on the smaller fractions most likely to be inhaled and deposited in the deeper regions of the lung. Smaller fibers within this range are toxicologically significant because they are more readily respirable, more likely to evade upper-airway clearance mechanisms, and more prone to induce frustrated phagocytosis upon interaction with alveolar macrophages. By focusing on this subset of fiber dimensions, the model captures the size ranges most relevant to human exposure and health risk, while maintaining consistency with existing detection limits and published measurements of ambient microplastic fibers.

Theoretical deposition data predicted by the ICRP model were compared across six distinct types of microplastics: PS, PP, PE, PET, PVC, and PMMA. These polymers contribute to environmental and human health risks due to their widespread use and persistence[1,3,4], their propensity to fragment into respirable micro- and nanoplastics[2,9,10,41], and their potential to induce inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and chemical toxicity[2,10,34,35]. Differences in polymer density and surface properties further influence deposition, clearance, and persistence within the respiratory system[19,21,23,24], underscoring their importance in inhalation exposure and toxicological studies[9,10,33,34].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

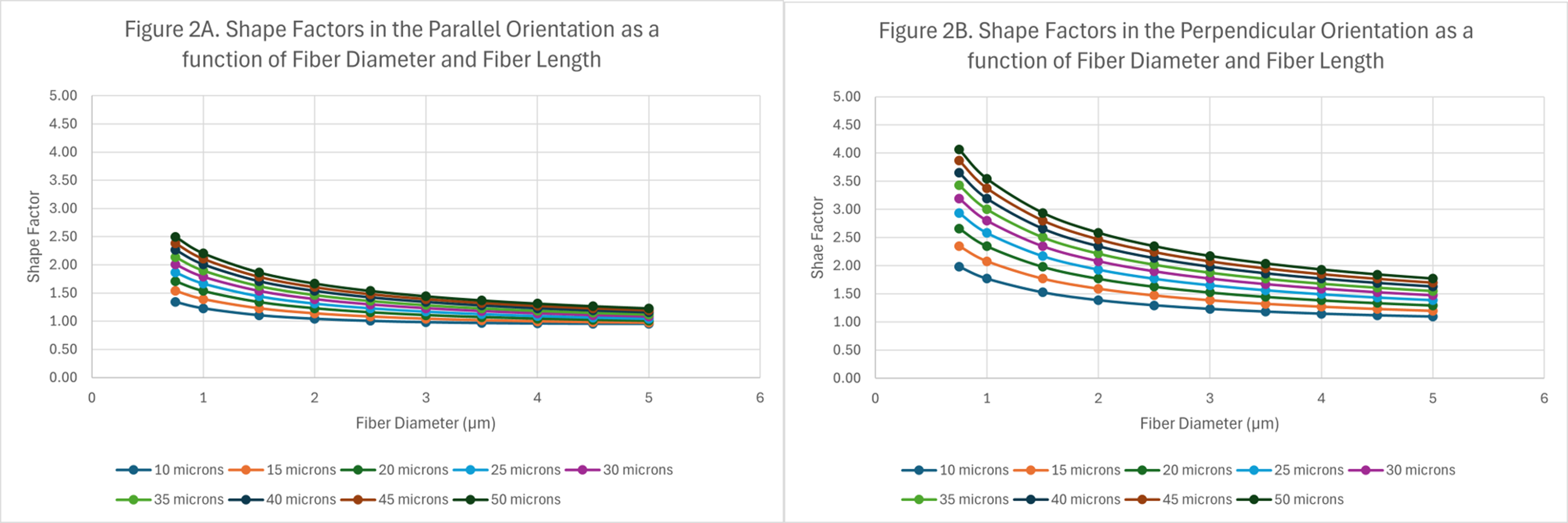

Data from the modeling has been plotted and illustrated in Figures 2-6. Figure 2 shows the shape factors as a function of fiber length and diameter.

Figure 2. Shape factors as a function of fiber length and diameter: (A) fibers in a parallel orientation, and (B) fibers in a perpendicular orientation.

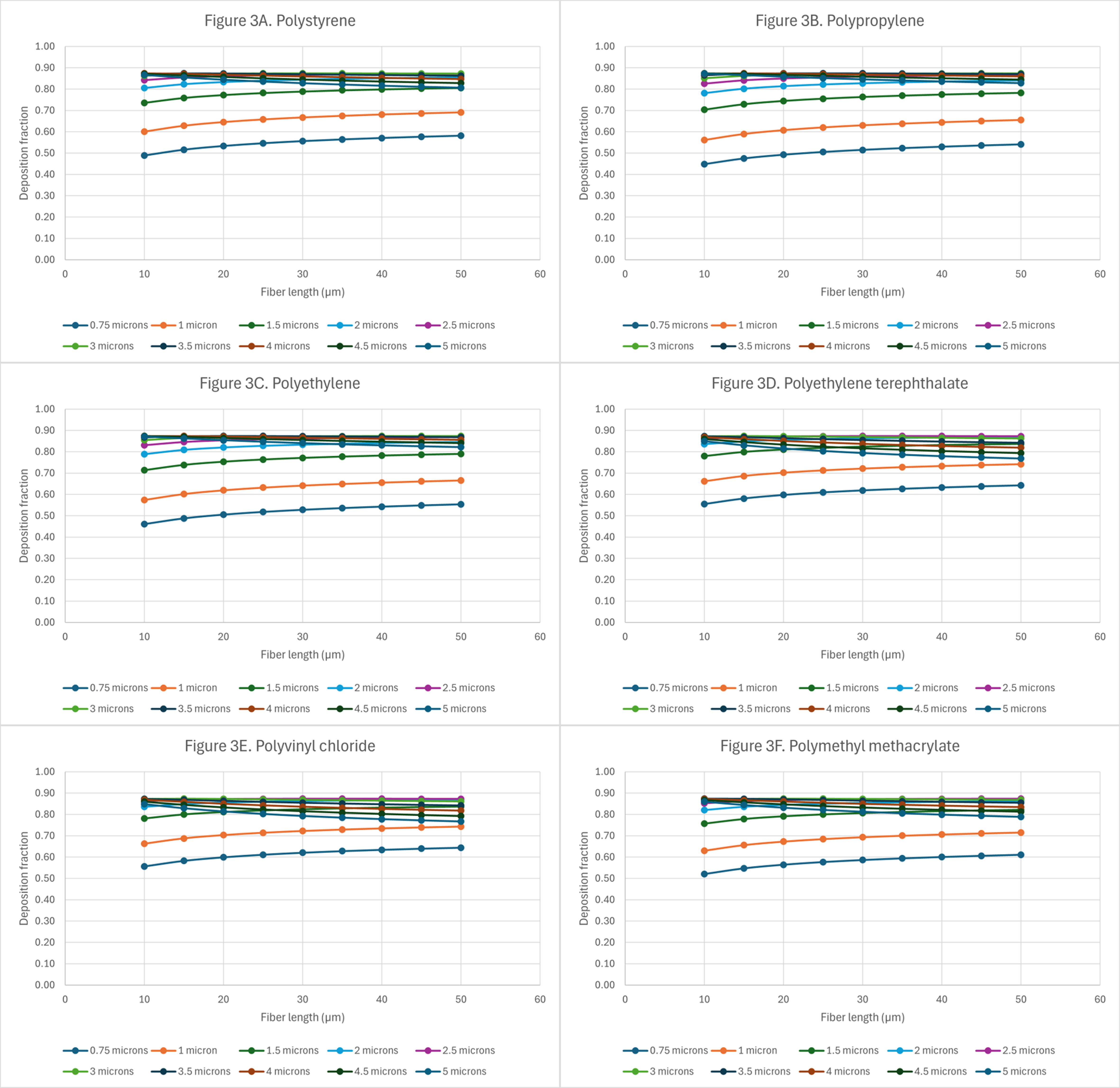

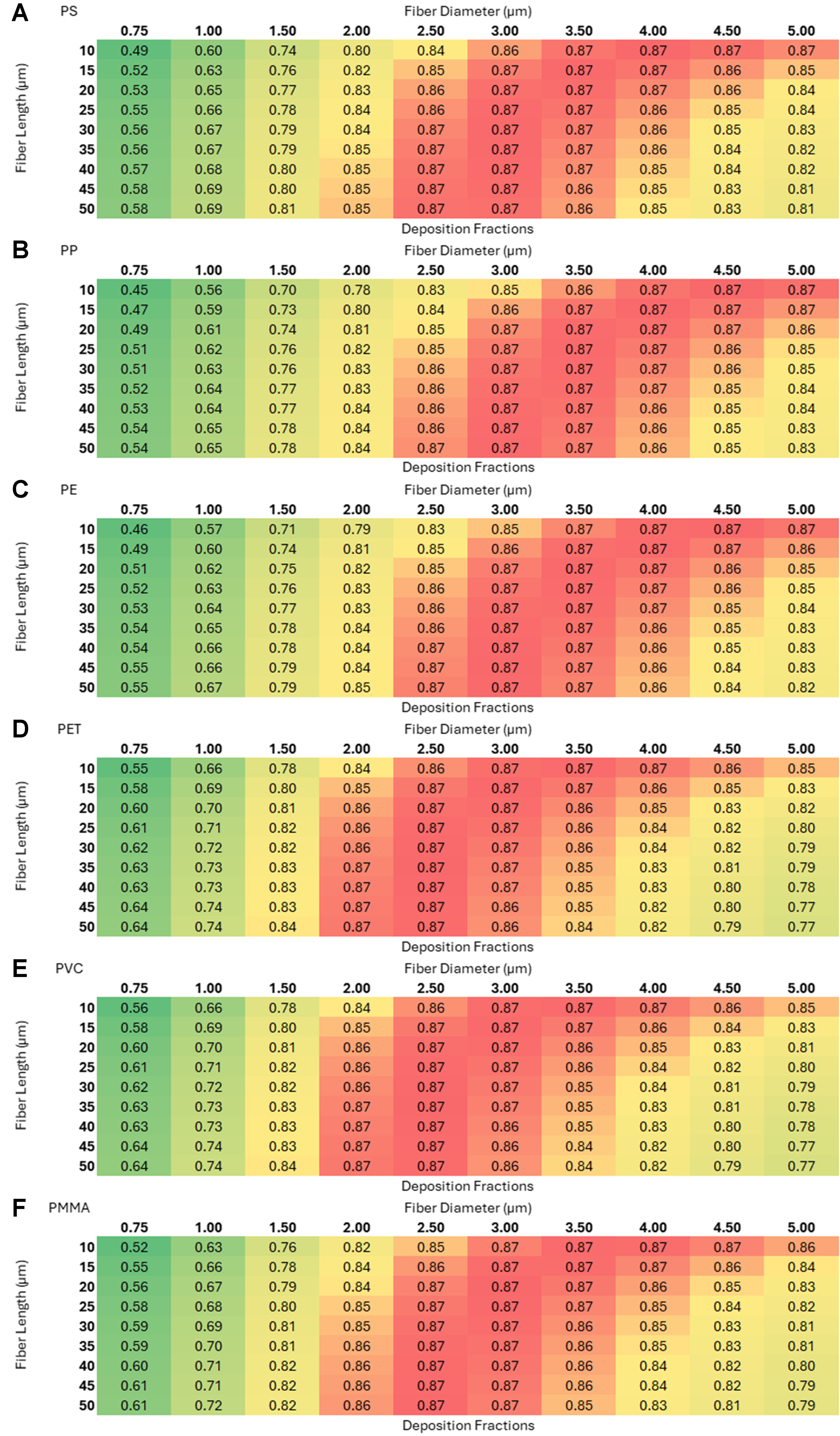

Figure 3. Deposition of microplastics with random orientation in the nasopharyngeal region: (A) polystyrene (PS); (B) polypropylene (PP); (C) polyethylene (PE); (D) polyethylene terephthalate (PET); (E) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and (F) polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

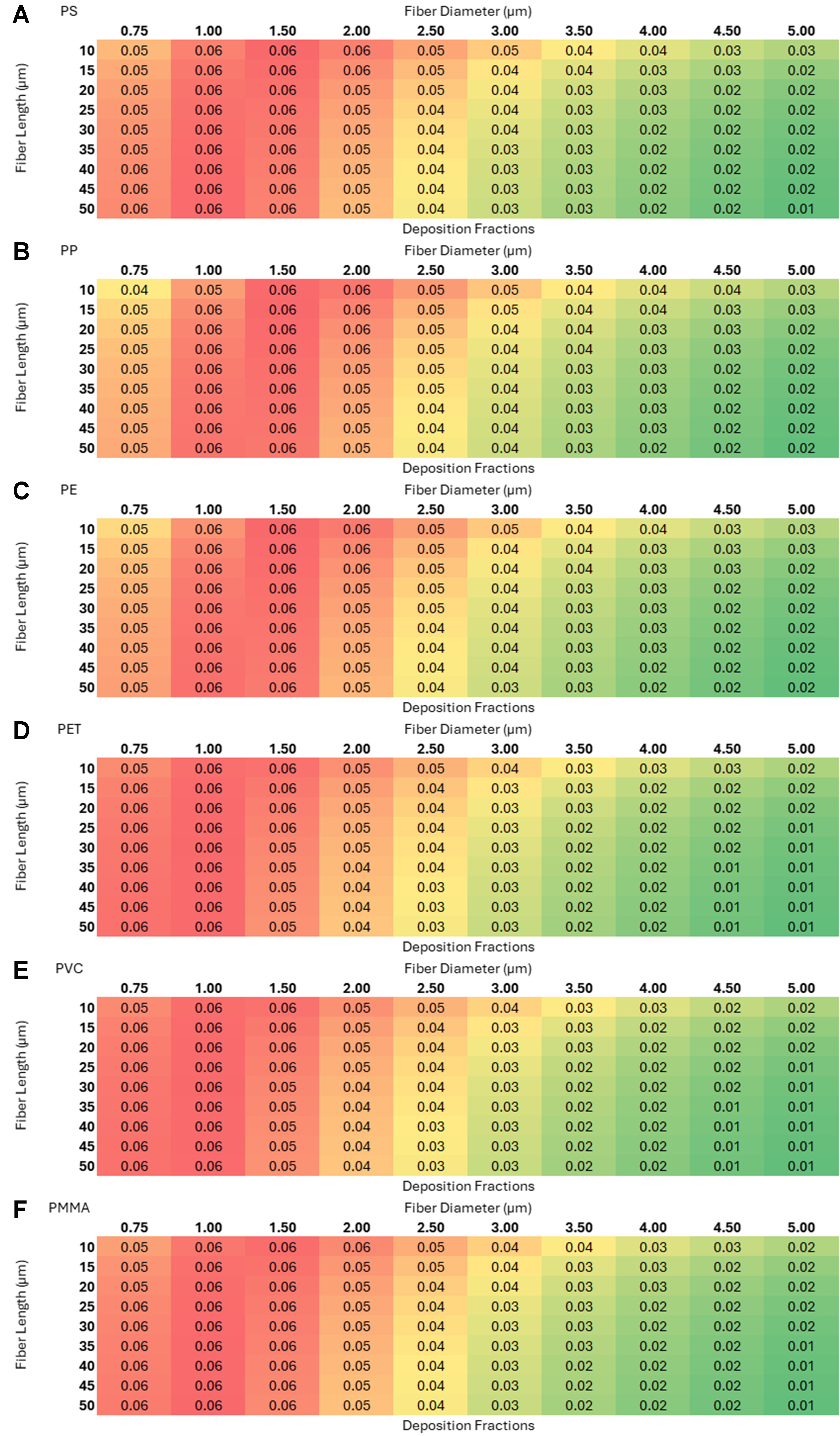

Figure 4. Deposition of microplastics with random orientation in the tracheobronchial region: (A) polystyrene (PS); (B) polypropylene (PP); (C) polyethylene (PE); (D) polyethylene terephthalate (PET); (E) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and (F) polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

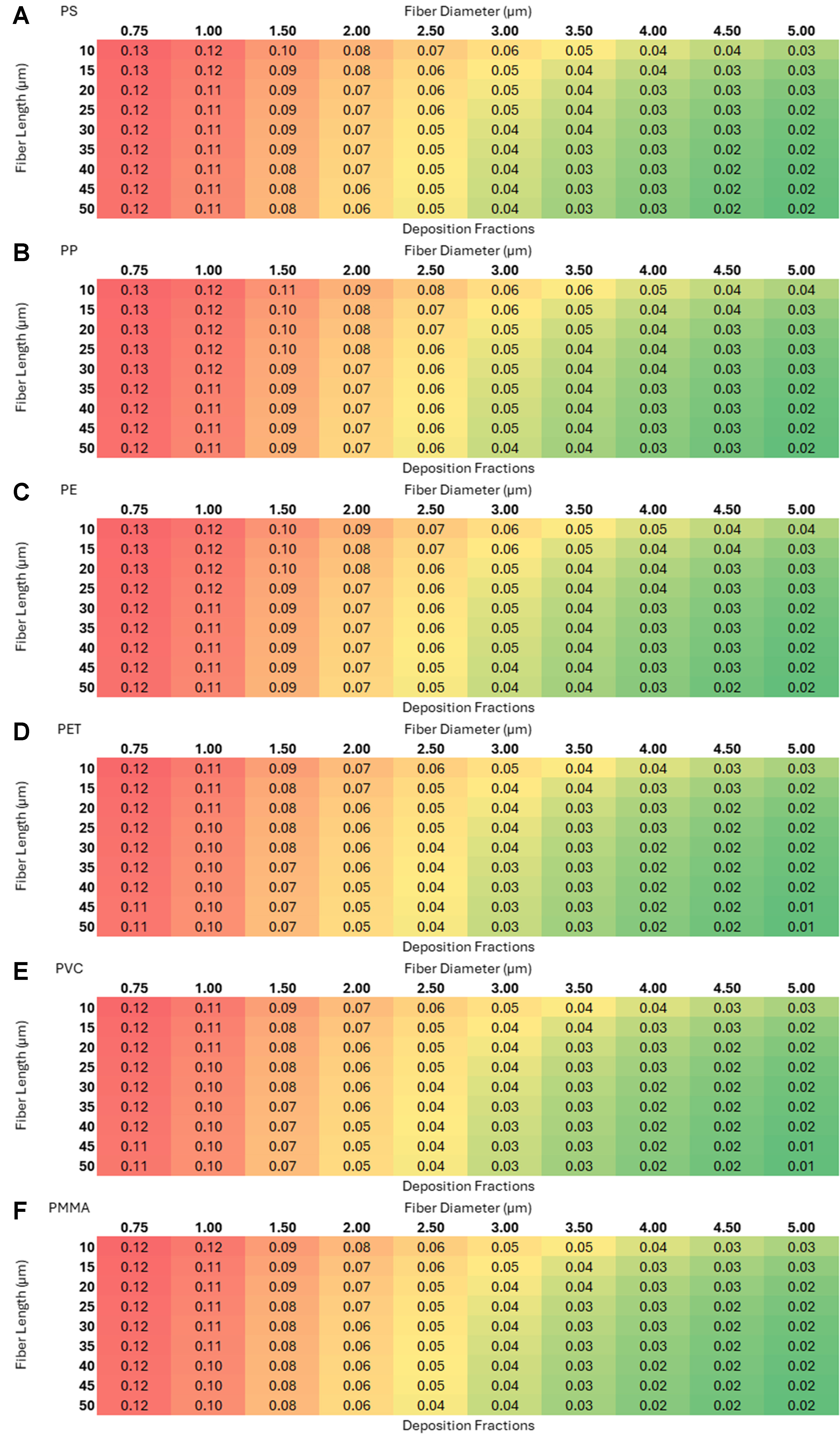

Figure 5. Deposition of microplastics with random orientation in the alveolar region: (A) polystyrene (PS); (B) polypropylene (PP); (C) polyethylene (PE); (D) polyethylene terephthalate (PET); (E) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and (F) polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

Figure 6. Deposition curves of microplastics in three regions of the lung as a function of their volume-equivalent diameter and orientation: (A) polystyrene (PS); (B) polypropylene (PP); (C) polyethylene (PE); (D) polyethylene terephthalate (PET); (E) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and (F) polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

Deposition fraction as a function of aerodynamic diameters

It is important to determine whether the fiber’s intrinsic properties can play a role in lung deposition. To standardize comparisons, random orientation plots for each of the microplastics were analyzed. Figure 3 shows the deposition patterns in the nasopharyngeal region for the different microplastics at varying lengths and diameters.

The larger deposition fractions in this region of the lung are for those fibers with aerodynamic diameters

Figure 4 shows deposition patterns in the tracheobronchial airways for microplastics of varying lengths and diameters.

Analysis of Figure 4A-F demonstrates that, for a given fiber length, an increase in fiber diameter is associated with a reduction in deposition fraction within the tracheobronchial region. The highest deposition fraction, approximately 0.06, occurs for fibers with aerodynamic diameters in the range of

Figure 5A-F presents corresponding results for the alveolar region of the lung, illustrating deposition fractions under similar conditions.

In the alveolar region [Figure 5A-F], the deposition fractions reach markedly higher values compared to those in the tracheobronchial region. The maximum deposition fraction observed is approximately 0.13, corresponding to fibers with a diameter of 0.75 µm and lengths of up to 35 µm. Even at the largest fiber dimensions (length = 50 µm and diameter = 5 µm), deposition fractions up to 0.02 are predicted for PS, PP, and PE [Figure 5A-C]. Figure 5A-F indicates that as the aerodynamic diameters increase, deposition in the alveolar region decreases. This effect is more pronounced for particles with diameters ≥ 1.5 µm. Large predicted deposition fractions in the alveolar region are concerning because macrophage clearance may be impaired due to frustrated phagocytosis.

Analysis of the alveolar deposition data indicates that particle deposition within the lung is primarily governed by aerodynamic diameter, with particle size determining their retention, distribution, and transport behavior. Fiber length, however, appears to play a more critical role in persistence and potential toxicity. In this study, deposition efficiency was assessed as a function of both fiber length and diameter, as these parameters influence not only uptake by alveolar macrophages but also clearance via the mucociliary escalator. It is well established that long, thin fibers are often incompletely phagocytosed and exhibit greater biological activity than shorter fibers[42]. Such persistent fibers may translocate across epithelial barriers[43], contributing to acute and chronic inflammatory responses. Notably, pleural mesotheliomas have been linked to the inhalation and deposition of fibers exceeding 8 µm in length with diameters below 0.25 µm[42]. Studies have shown that carbon nanotubes (CNTs) can induce granulomas, fibrosis and inflammation in lungs and such effects are stronger when CNTs are longer and more rigid making it more challenging for macrophages to phagocytose them resulting in frustrated phagocytosis[44]. Fibers that deposit within the terminal bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveoli may trigger chronic inflammatory responses, granuloma formation, or fibrosis[45,46]. According to Greim et al., the interaction of fibers or particles with pulmonary cells can elicit inflammatory processes that subsequently stimulate cell proliferation and secondary genotoxicity through the persistent generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[46]. Excessive ROS production is a well-documented driver of oxidative stress, ultimately contributing to chronic inflammation and the development of pulmonary disease. Given that particle deposition in the lung is primarily dictated by aerodynamic diameter, it is essential to consider not only the deposition fraction but also the clearance mechanisms that determine the persistence and biological impact of inhaled fibers.

Airborne microplastics are found in many different shapes, including elongated fibers, irregularly shaped fragments, and spherical particles. This consideration is particularly important, as the interactions of microplastic particles with cells and tissues are also strongly influenced by particle shape. Fiber-shaped particles which are the primary shape of airborne microplastics can induce toxicity via frustrated phagocytosis and this is particularly important as the data shown in Figure 5A-F indicate that large deposition fractions are possible in the alveolar region. In frustrated phagocytosis, resident alveolar macrophages make unsuccessful attempts to phagocytose thin and long fibers; however, because the fibers exceed the size of the macrophages, internalization and uptake cannot occur. When microplastic particles deposit in the alveolar space, their clearance is governed by relatively slow processes such as uptake by alveolar macrophages and subsequent transport into the interstitium. This phenomenon, often referred to as frustrated phagocytosis, has been extensively characterized for glass and titanium dioxide fibers once a critical fiber length of approximately 12-15 μm is exceeded[47,48]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that fiber-shaped titanium dioxide particles exhibit greater toxic potential than spherical particles of identical chemical composition[49]. Since frustrated phagocytosis is driven by particle geometry, this may be an important toxicological mechanism for microplastic-cell interactions. To date, most in vitro research on microplastic toxicity has focused on spherical particles, even though most airborne microplastics are elongated fibers[50]. The induced toxicity of microplastic fibers remains a critical research gap, with limited data available.

Differences in deposition fractions between regions of deposition

As shown in Figures 3-5, the primary deposition site for these microplastics is the nasopharyngeal region, followed by the alveolar region. Irrespective of particle orientation or polymer type, but dependent on both length and diameter, the fraction of inhaled microplastics deposited in the nasopharyngeal region can reach values as high as 0.87 of the inhaled mass [Figure 3]. These elevated deposition fractions correspond to aerodynamic diameters in the range of approximately 5-7 µm, as illustrated in Figure 3A-F. Deposition in the head airways constitutes a substantial fraction of total lung deposition, which is important because entrapment and clearance of particles serve as a key respiratory defense mechanism protecting the more vulnerable deeper regions of the lung. In the tracheobronchial airways, deposition fractions reach values up to 0.06, corresponding to an aerodynamic diameter range of approximately 2-4 µm, as illustrated in Figure 4A-F. In the alveolar region, the maximum deposition fraction observed is 0.13 [Figure 5A-F], which is associated with an aerodynamic fiber diameter of ~1.6 ± 0.1 µm. These patterns of regional deposition between the three regions (head airways, tracheobronchial, and alveolar) were echoed irrespective of particle density, shape, or orientation.

The inhalation, deposition and toxicity of particles depend upon several factors such as size, shape, orientation, and surface charge. Once microplastics are inhaled, a substantial fraction of the inhaled mass is expected to be filtered in the nasal passages due to anatomical constraints and complex airflow patterns[51]. In addition to the influence of breathing patterns on particle deposition, four principal mechanisms govern particle deposition within the lung: Brownian diffusion, inertial impaction, gravitational settling, and interception[52]. These factors, while influencing inhalation and deposition potential, can affect the retention or clearance and toxicity of these particles. Once inhaled, particles with aerodynamic diameters less than

Differences in deposition fractions arising from parallel vs. perpendicular orientation

Comparisons between the parallel and perpendicular orientation of fibers [Figure 6A-F] were conducted to determine if a particular orientation resulted in greater deposition in a specific region of the lung. Such comparisons could not be made based on aerodynamic diameter, as its determination depends on the shape factor, which in turn varies with particle orientation (parallel or perpendicular). Accordingly, the data for regional deposition fractions was plotted using the volume-equivalent diameter for the fibers.

Examination of Figure 6A-F indicates that particle orientation produces only minimal differences in deposition within the tracheobronchial and alveolar regions. By contrast, the most pronounced orientation-dependent variations in deposition fraction are observed in the nasopharyngeal region. At the lowest volume-equivalent diameter, the difference in deposition can range between 18%-23%, depending on the reference orientation. The difference in deposition fraction for the nasopharyngeal region continues to narrow until the volume-equivalent diameter reaches ~6 µm. Beyond the volume-equivalent diameter of

Experimental studies often distinguish between parallel and perpendicular fiber orientations when modeling deposition, as orientation directly influences aerodynamic diameter and, consequently, regional deposition efficiency in the respiratory tract. Fibers aligned parallel to the airstream generally present a smaller aerodynamic profile and are more likely to penetrate deeper into the alveolar spaces, whereas perpendicular orientations increase the effective aerodynamic diameter, promoting deposition in the upper airways.

In real-world exposure scenarios, however, inhaled fibers undergo constant turbulence, random rotation, and reorientation within the dynamic airflow of the respiratory tract. As a result, the consistent maintenance of a purely parallel or perpendicular orientation is unlikely. Instead, an averaging effect across multiple orientations is expected, diminishing the predictive value of strict orientation-based models for population-level exposure. Nevertheless, fiber orientation retains biological significance. For instance, fibers that deposit parallel to epithelial surfaces may be less readily phagocytosed, potentially enhancing persistence, whereas perpendicular orientations may increase the probability of interception with airway walls. Thus, while orientation is a critical variable for understanding deposition mechanisms under controlled conditions, its practical application to real-world exposures is limited. Instead, orientation-dependent data should be interpreted as bounding scenarios that help frame the range of possible deposition outcomes rather than as absolute predictors of health risk.

The influence of types of plastic on deposition fraction

A comparison was conducted to determine whether different plastic densities representative of diverse types of plastics would yield variability in deposition patterns. Comparing Figure 3A-F, the deposition fractions in the nasopharyngeal regions are larger for microplastics with greater densities. Figure 3B and E illustrates the deposition fractions for PP (ρ = 0.88 g/cm3) and PVC (ρ = 1.4 g/cm3) respectively in the nasopharyngeal region. The deposition fractions for a fiber with length = 10 µm and diameter = 1 µm are 0.56 (PP) and 0.66 (PVC), respectively, which is a 10% difference in the quantity of particles deposited in the nasopharyngeal region.

In the tracheobronchial region, the difference in deposition fractions between the smallest and largest aerodynamic diameters, for a given fiber length, increases with microplastic density. For PS, PP, and PE fibers, deposition fractions are initially low but increase as fiber length increases. In contrast, fibers of the same size composed of PET, PVC, or PMMA show constant deposition fractions of 0.06, regardless of length. For all other particle types, deposition fractions in the tracheobronchial region are highest at shorter fiber lengths and progressively decline as fiber length increases. In the alveolar region, the deposition curves [Figure 5A-F] were examined to assess potential differences in deposition as a function of plastic density. Comparing the deposition curves for plastic densities greater than ~1 g/cm3 (PET, PVC, and PMMA) against those with densities less than ~1 g/cm3 (PS, PP, and PE), one can see that deposition for the denser plastics is lower than for lighter plastics. Although differences in alveolar deposition are not readily distinguishable from the graphs, for fibers within the micron size range such differences may correspond to substantial numbers of deposited fibers, depending on the type of plastic. In the alveolar region, the highest deposition fractions for plastics with a density < 1 g/cm3 occur at aerodynamic diameters of approximately 1.6 ±

However, an important physicochemical property driving microplastic toxicity may be the particles’ ζ-potential - an indicator of the particle’s surface charge based upon surface functional groups. Interaction of particles such as hydrophobic interactions and electrostatic forces with cells and tissues can be influenced by this indicator[65,66]. Recently, it has been shown that chemically identical model microplastic particles may have varying ζ-potentials[67] and environmental conditions such as weathering may introduce negatively charged groups on the surfaces of microplastics altering the particle’s ζ-potential. Experimental evidence shows that weathering altered the particle’s ζ-potential via introduction of carboxylic groups, from ultraviolet exposure, on the surfaces of PET, PE, PP, and acrylate polymers[68-70]. The ζ-potential of microplastic particles can be readily quantified and serves as an indicator of their interactions with cells and tissues, which may play a critical role in determining microplastic toxicity within the respiratory tract.

Following deposition in the lung, these particles are immediately subject to innate defense mechanisms, including a rapid clearance pathway mediated by the mucociliary escalator, as well as several slower clearance processes[71,72]. The mucus layer in the respiratory tract is an effective mechanism for the clearance of foreign particles and understanding the biophysical interactions between microplastic particles and the mucociliary escalator is of prime importance. When larger microplastic particles deposit on the mucus layer of the bronchial airways, their complete clearance may take several days. In contrast, smaller particles can diffuse into the periciliary spaces beneath the mucus layer, where they are cleared more slowly via mechanisms such as uptake by airway macrophages or epithelial transcytosis[71]. Under these conditions, complete clearance may take several weeks to months. In addition, the adsorption of environmental contaminants onto the surfaces of microplastic particles is expected to change the surface chemistry and bioactivity and thus there needs to be an emphasis on toxicity studies assessing the influence of environmentally weathered microplastics.

It is expected that fibers with sizes larger than the mucus mesh network may be trapped by steric obstruction whereas smaller particles may be able to diffuse through the mucus pores[73]. Surface chemistry of fibers will play a vital role in the entrapment by mucins as negatively charged mucins can trap particles with positive domains[74]. Similarly, the high density of glycans in the mucins may result in hydrogen bonding with carboxyl or hydroxyl groups on the fiber surface[75]. Further, the non-glycosylated regions in the mucins create a hydrophobic domain that may result in hydrophobic interactions with the fibers[76]. The zeta potential, an indicator of surface chemistry, for the type of plastics investigated in this study (i.e., PS, PP, PE, PET, PVC, and PMMA) is strongly negative, suggesting that fibers may be able to evade interactions with mucin fibers. Plastics such as untreated PE, PS, PP, PVC, and PMMA do not have either carboxyl or hydroxyl groups on their surfaces and are thus not expected to be trapped due to hydrogen bonding. In the case of PET, carboxyl and hydroxyl groups are present on the plastic’s surface, enabling hydrogen bonding for this type of polymer. The mucus mesh also provides protection through hydrophobic interactions, which are expected to be the primary mechanism of plastic fiber entrapment since plastics are inherently hydrophobic[76].

Finally, to translate the findings from this research into methods applicable to exposure sciences and industrial hygiene, data was aggregated by the type of plastic and plotted as a function of aerodynamic diameter. These plots and their corresponding mathematical models are shown in Figure 7A-F.

Figure 7. Theoretical deposition of fiber shaped microplastics in 3 regions of the lung as a function of aerodynamic diameter: (A) polystyrene (PS); (B) polypropylene (PP); (C) polyethylene (PE); (D) polyethylene terephthalate (PET); (E) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and (F) polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

The purpose of these plots is to assist exposure scientists, toxicologists, risk managers, and industrial hygienists by providing equations that estimate deposition of microplastics from aerodynamic diameters. If the aerodynamic diameter of a particle of known plastic type is available, its deposition within the nasopharyngeal, tracheobronchial, and alveolar regions can be predicted using the deposition curves and their corresponding equations. The predicted deposition fractions are summarized into heat maps

Figure 8. Deposition fractions as a function of length and diameter for six microplastics with random orientation in the nasopharyngeal region: (A) polystyrene (PS); (B) polypropylene (PP); (C) polyethylene (PE); (D) polyethylene terephthalate (PET); (E) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and (F) polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

Figure 9. Deposition fractions as a function of length and diameter for six microplastics with random orientation in the tracheobronchial region: (A) polystyrene (PS); (B) polypropylene (PP); (C) polyethylene (PE); (D) polyethylene terephthalate (PET); (E) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and (F) polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

Figure 10. Deposition fractions as a function of length and diameter for six microplastics with random orientation in the alveolar region: (A) polystyrene (PS); (B) polypropylene (PP); (C) polyethylene (PE); (D) polyethylene terephthalate (PET); (E) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and (F) polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

The three 2 × 3 heat-map grids [Figures 8-10] - representing the nasopharyngeal, tracheobronchial, and alveolar regions (each panel shows PS, PP, PE, PET, PVC, PMMA; axes: fiber length 10-50 µm vs. diameter 0.75-5 µm) - reveal a clear region-specific shift in size selectivity. In the nasopharyngeal grid (warm palette), deposition is maximal (~0.87) for intermediate diameters ~2.5-4 µm across most lengths, with lower values for very thin (≤ 1 µm) and thick (~5 µm) fibers. In the tracheobronchial grid (cool palette), peaks are lower and tightly constrained - ~0.06 at 0.75-1.5 µm - and decline monotonically with increasing diameter; length has minimal influence. In the alveolar grid, small diameters (0.75-1 µm) and shorter lengths yield the highest fractions (~0.12-0.13), with steady decreases as diameter or length increases. Patterns are qualitatively consistent across polymers, indicating that geometry dominates over polymer type for regional deposition within the modeled ranges. Using such theoretical models provides several advantages amongst which a few key ones are listed:

1. These models use data predicted by equations that have been extensively used in lung deposition modeling. Application of such models to estimate potential inhalation exposure to microplastic fibers reduces reliance upon resources which can be quite burdensome.

2. Conducting multiple experiments with variable ranges of conditions can also be resource-intensive compared with models that allow for repeatability and scalability of simulations with minimal additional expenditures.

3. Experiments can be designed and conducted over prolonged periods of time whereas, in contrast, models can quickly provide predictions or estimates efficiently and quickly.

4. Theoretical models also reduce the need for animal or human testing providing ethical alternatives to standard historical approaches.

The modeling results presented here provide valuable insights into regional lung deposition of fibrous microplastics; however, several sources of uncertainty must be acknowledged. Deposition fractions are highly sensitive to small changes in fiber diameter, length, and aerodynamic properties, meaning that variability in environmental samples may lead to deviations from predicted values. In addition, while orientation was modeled under parallel, perpendicular, and random conditions, real-world airflow induces continuous reorientation, making strict orientation comparisons less representative. Despite these uncertainties, the consistency of predicted trends across multiple polymer types and fiber dimensions strengthens confidence in the overall deposition patterns, particularly the identification of the nasopharyngeal and alveolar regions as the principal sites of concern.

The deposition insights presented provide a critical foundation for integrating microplastic inhalation into quantitative risk assessment frameworks. By generating deposition curves and equations across fiber sizes, shapes, densities, and orientations, the study offers tools that can be directly incorporated into existing respiratory tract models such as those developed by the ICRP. These predictions allow regulators and exposure scientists to estimate regional lung burdens based on measured or modeled airborne concentrations of microplastics. Furthermore, linking deposition outcomes with clearance mechanisms and toxicological endpoints will support the development of dose–response relationships necessary for regulatory decision-making. Ultimately, the incorporation of fiber-specific deposition data into exposure and risk assessment tools will enable more accurate evaluations of population-level health risks and inform evidence-based policy for managing airborne microplastic pollution.

Limitations

While this study advances understanding of how microplastic particle size, shape, and orientation influence deposition patterns in the human respiratory tract, several important limitations must be acknowledged. This analysis relied primarily on theoretical modeling based on the ICRP framework with shape factor adjustments. While informative, this approach cannot fully represent the complexity of human respiratory physiology, including variations in airway geometry, breathing patterns, and pre-existing conditions. Diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pulmonary fibrosis likely alter microplastic deposition and clearance compared with healthy lungs. Airway narrowing and increased turbulence may shift deposition toward central airways, whereas impaired mucociliary clearance or macrophage dysfunction can prolong residence times. In fibrotic lungs, reduced alveolar surface area may limit deep-lung deposition but increase fiber persistence, suggesting heightened vulnerability among individuals with chronic respiratory disease. The physicochemical diversity of environmental microplastics also exceeds the subset modeled here. Real-world particles often exhibit irregular morphologies, mixed polymer compositions, and surfaces modified by weathering or contaminant adsorption, all of which influence aerodynamic behavior, surface charge, and biological reactivity. The effects of environmental aging - through photo-oxidation, abrasion, and microbial activity - were similarly excluded, even though such processes generate smaller, more reactive particles that may enhance inhalation exposure and toxicity[3,68,69]. Simplifying assumptions regarding fiber orientation and static ζ-potential values may further misrepresent airflow dynamics and temporal variability. Moreover, this modeling effort did not address post-depositional biological processes, including mucociliary clearance, macrophage uptake, or translocation across epithelial barriers, which strongly influence persistence and toxicity. Consequently, the reported deposition fractions indicate potential sites of concern rather than direct predictors of health outcomes. Finally, variability in environmental monitoring limits the representativeness of the input data; reported size distributions, fiber geometries, and polymer identities differ among studies due to sampling and analytical inconsistencies. The limited resolution of many detection methods likely underestimates exposure to submicron fibers capable of deep-lung penetration.

Accounting for the tremendous variability in types of microplastics generated and released into the environment and various exposure scenarios, future studies should focus on the following:

1. There is a critical need to investigate airborne microplastic particles with aerodynamic diameters < 10 µm, as smaller particles may not only have a higher potential for inhalability but, due to their large surface area, may also exhibit greater bioactivity upon deposition in the lung.

2. Particle shape may influence how these microplastic particles navigate through the respiratory tract and interact with cells and tissues. Elongated particles, particularly those that are bio-persistent, have the potential to induce frustrated phagocytosis eventually leading to chronic inflammation. Evidence suggests that ambient aerosolized microplastics bear no defined shape, but most exhibit a fiber-like morphology. Thus, future toxicity studies should focus on particles that resemble fibers.

3. As fiber is inhaled, there are no definitive means by which the orientation of the fiber, as it migrates through the respiratory tract, can be determined. Thus, while fiber orientation is an important factor for understanding deposition differences between parallel and perpendicular alignment, its practical applicability remains limited. It is important to understand and accept that random orientation of the fiber provides a balanced and logical solution to the unknown orientation of the fiber once inside the respiratory path. Thus, future exposure and toxicity studies should report particle orientation (parallel, perpendicular, or random) to enable researchers to better understand differences in lung deposition.

This study elucidates the key physicochemical determinants influencing microplastic fiber deposition in the respiratory tract, highlighting how particle size, shape, and orientation govern lung deposition across diverse microplastic types. However, the predictive precision of the modeling remains limited by underlying assumptions, environmental variability, and the absence of biological validation. Identifying these determinants is a critical step toward advancing our understanding of the potential health impacts of inhaled microplastics.

CONCLUSIONS

This study advances the understanding of inhalation exposure to microplastics by systematically modeling the influence of fiber size, shape, density, and orientation on regional lung deposition. Unlike previous work predominantly focused on spherical particles, the analysis highlights fibrous microplastics as the dominant airborne form and introduces novel deposition curves and equations that directly inform exposure assessment and risk evaluation.

The results demonstrate that physicochemical attributes - particularly fiber diameter, length, and surface properties - are key determinants of persistence, clearance potential, and toxicity. Orientation modeling under parallel, perpendicular, and random conditions defines realistic boundary scenarios, with random orientation emerging as the most representative of environmental exposure conditions.

By establishing clear relationships between fiber physicochemical properties and modeled deposition behavior, this study provides a robust framework for more accurate evaluation of human health risks associated with inhaled microplastics. The integration of morphological and aerodynamic parameters enhances predictive capability and offers a quantitative basis for assessing microplastic behavior within the respiratory system.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the RHP (RHP Risk Management, Inc.) staff, who contributed to manuscript review, editing, and preparation.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, data collection, analysis, methodology, manuscript writing: Jachak, A. C.

Data verification, manuscript editing and proofreading: Pagone, F.

Availability of data and materials

The analysis and all pertinent supporting information can be found here: https://rhprisk.box.com/s/0tlbdgnscs2pjyed2l1w0p4drrpwn2e3.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors are affiliated with RHP Risk Management, Inc.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Napper, I. E.; Thompson, R. C. Plastic debris in the marine environment: history and future challenges. Glob. Chall. 2020, 4, 1900081.

2. Yee, M. S.; Hii, L. W.; Looi, C. K.; et al. Impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on human health. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 496.

3. Andrady, A. L. Persistence of plastic litter in the oceans. In: Bergmann M, Gutow L, Klages M, editors. Marine anthropogenic litter. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 57-72.

4. Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J. R.; Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782.

5. Kane, I. A.; Clare, M. A. Dispersion, accumulation, and the ultimate fate of microplastics in deep-marine environments: a review and future directions. Front. Earth. Sci. 2019, 7, 80.

6. Mbachu, O.; Jenkins, G.; Pratt, C.; Kaparaju, P. A new contaminant superhighway? A review of sources, measurement techniques and fate of atmospheric microplastics. Water. Air. Soil. Pollut. 2020, 231, 4459.

7. Brahney, J.; Mahowald, N.; Prank, M.; et al. Constraining the atmospheric limb of the plastic cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118, e2020719118.

8. Zhang, Y.; Lykaki, M.; Alrajoula, M. T.; et al. Microplastics from textile origin - emission and reduction measures. Green. Chem. 2021, 23, 5247-71.

9. Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, C.; et al. Airborne microplastics: occurrence, sources, fate, risks and mitigation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 858, 159943.

10. Amato-Lourenço, L. F.; Dos Santos Galvão, L.; de Weger, L. A.; Hiemstra, P. S.; Vijver, M. G.; Mauad, T. An emerging class of air pollutants: potential effects of microplastics to respiratory human health? Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 749, 141676.

11. Huang, Y.; Qing, X.; Wang, W.; Han, G.; Wang, J. Mini-review on current studies of airborne microplastics: analytical methods, occurrence, sources, fate and potential risk to human beings. TrAC. Trend. Anal. Chem. 2020, 125, 115821.

12. Chen, G.; Feng, Q.; Wang, J. Mini-review of microplastics in the atmosphere and their risks to humans. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 703, 135504.

13. Acharya, S.; Rumi, S. S.; Hu, Y.; Abidi, N. Microfibers from synthetic textiles as a major source of microplastics in the environment: a review. Text. Res. J. 2021, 91, 2136-56.

14. Tang, K. H. D.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, D. Health risk of human exposure to microplastics: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1155-83.

15. Liu, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Widespread distribution of PET and PC microplastics in dust in urban China and their estimated human exposure. Environ. Int. 2019, 128, 116-24.

16. Szewc, K.; Graca, B.; Dołęga, A. Atmospheric deposition of microplastics in the coastal zone: characteristics and relationship with meteorological factors. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 761, 143272.

17. Chen, W.; Fryrear, D. W. Aerodynamic and geometric diameters of airborne particles. J. Sediment. Res. 2001, 71, 365-71.

18. Reponen, T.; Grinshpun, S. A.; Conwell, K. L.; Wiest, J.; Anderson, M. Aerodynamic versus physical size of spores: measurement and implication for respiratory deposition. Grana 2001, 40, 119-25.

19. Li, T.; Yu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Duan, J. A comprehensive understanding of ambient particulate matter and its components on the adverse health effects based from epidemiological and laboratory evidence. Part. Fibre. Toxicol. 2022, 19, 67.

20. Abbasi, R.; Shineh, G.; Mobaraki, M.; Doughty, S.; Tayebi, L. Structural parameters of nanoparticles affecting their toxicity for biomedical applications: a review. J. Nanopart. Res. 2023, 25, 43.

21. Borgatta, M.; Breider, F. Inhalation of microplastics - a toxicological complexity. Toxics 2024, 12, 358.

23. Yuan, T.; Gao, L.; Zhan, W.; Dini, D. Effect of particle size and surface charge on nanoparticles diffusion in the brain white matter. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 767-81.

24. Saavedra, J.; Stoll, S.; Slaveykova, V. I. Influence of nanoplastic surface charge on eco-corona formation, aggregation and toxicity to freshwater zooplankton. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 715-22.

25. Wright, S. L.; Ulke, J.; Font, A.; Chan, K. L. A.; Kelly, F. J. Atmospheric microplastic deposition in an urban environment and an evaluation of transport. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105411.

26. Enyoh, C. E.; Verla, A. W.; Verla, E. N.; Ibe, F. C.; Amaobi, C. E. Airborne microplastics: a review study on method for analysis, occurrence, movement and risks. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 668.

27. Hinds, W. C. Aerosol technology: properties, behavior, and measurement of airborne particles. 2nd edition. New York: Wiley. 2012. https://books.google.com/books/about/Aerosol_Technology.html?id=qIkyjPXfWK4C. (accessed 13 Nov 2025).

28. Stöber, W. Dynamic shape factor of nonspherical aerosol particles. In Assessment of airborne particles: fundamentals, applications, and implications to inhalation toxicity. Charles C. Thomas, 1972; pp. 249-89. https://hero.epa.gov/reference/629615/. (accessed 13 Nov 2025).

29. Cheng, Y.; Yeh, H.; Allen, M. D. Dynamic shape factor of a plate-like particle. Aerosol. Sci. Technol. 1988, 8, 109-23.

30. Fuchs, N. A. The mechanics of aerosols. Dover Publications; 1964. https://books.google.com/books?id=5XbZAAAAMAAJ. (accessed 13 Nov 2025).

31. McNown, J. S.; Malaika, J. Effects of particle shape on settling velocity at low Reynolds numbers. Eos. Trans. AGU. 1950, 31, 74-82.

32. Mercer, T. T.; Morrow, P. E.; Stoeber, W. Assessment of airborne particles. fundamentals, applications, and implications to inhalation toxicity. In Proceedings Publication of the Third International Conference on Environmental Toxicity, Rochester, USA. 18-20 June, 1970. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED066326. (accessed 13 Nov 2025).

33. Jenner, L. C.; Rotchell, J. M.; Bennett, R. T.; Cowen, M.; Tentzeris, V.; Sadofsky, L. R. Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 831, 154907.

34. Wang, S.; Lu, W.; Cao, Q.; et al. Microplastics in the lung tissues associated with blood test index. Toxics 2023, 11, 759.

35. Chen, Q.; Gao, J.; Yu, H.; et al. An emerging role of microplastics in the etiology of lung ground glass nodules. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 605.

36. Napper, I. E.; Parker-Jurd, F. N. F.; Wright, S. L.; Thompson, R. C. Examining the release of synthetic microfibres to the environment via two major pathways: atmospheric deposition and treated wastewater effluent. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 857, 159317.

37. Soltani, N. S.; Taylor, M. P.; Wilson, S. P. Quantification and exposure assessment of microplastics in Australian indoor house dust. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 283, 117064.

38. Jenner, L. C.; Sadofsky, L. R.; Danopoulos, E.; Rotchell, J. M. Household indoor microplastics within the Humber region (United Kingdom): quantification and chemical characterisation of particles present. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 259, 118512.

39. Li, Y.; Shao, L.; Wang, W.; et al. Airborne fiber particles: types, size and concentration observed in Beijing. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 705, 135967.

40. Huang, Y.; He, T.; Yan, M.; et al. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a subtropical urban environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126168.

41. Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Gao, T.; Sillanpää, M. Atmospheric microplastics: a review on current status and perspectives. Earth. Sci. Rev. 2020, 203, 103118.

42. Donaldson, K.; Brown, R. C.; Brown, G. M. New perspectives on basic mechanisms in lung disease. 5. Respirable industrial fibres: mechanisms of pathogenicity. Thorax 1993, 48, 390-5.

43. Donaldson, K.; Murphy, F.; Schinwald, A.; Duffin, R.; Poland, C. A. Identifying the pulmonary hazard of high aspect ratio nanoparticles to enable their safety-by-design. Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 143-56.

44. Donaldson, K.; Aitken, R.; Tran, L.; et al. Carbon nanotubes: a review of their properties in relation to pulmonary toxicology and workplace safety. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 92, 5-22.

46. Greim, H.; Borm, P.; Schins, R.; et al. Toxicity of fibers and particles. Report of the workshop held in Munich, Germany, 26-27 October 2000. Inhal. Toxicol. 2001, 13, 737-54.

47. Hamilton, R. F.; Wu, N.; Porter, D.; Buford, M.; Wolfarth, M.; Holian, A. Particle length-dependent titanium dioxide nanomaterials toxicity and bioactivity. Part. Fibre. Toxicol. 2009, 6, 35.

48. Padmore, T.; Stark, C.; Turkevich, L. A.; Champion, J. A. Quantitative analysis of the role of fiber length on phagocytosis and inflammatory response by alveolar macrophages. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 58-67.

49. Allegri, M.; Bianchi, M. G.; Chiu, M.; et al. Shape-related toxicity of titanium dioxide nanofibres. PLoS. One. 2016, 11, e0151365.

51. Bailey, M. R. The new ICRP model for the respiratory tract. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 1994, 53, 107-14.

52. Koblinger, L.; Hofmann, W. Monte Carlo modeling of aerosol deposition in human lungs. Part I: Simulation of particle transport in a stochastic lung structure. J. Aerosol. Scie. 1990, 21, 661-74.

53. Foord, N.; Black, A.; Walsh, M. Regional deposition of 2.5-7.5 μm diameter inhaled particles in healthy male non-smokers. J. Aerosol. Sci. 1978, 9, 343-57.

54. Lippmann, M. Effects of fiber characteristics on lung deposition, retention, and disease. Environ. Health. Perspect. 1990, 88, 311-7.

55. Carvalho, T. C.; Peters, J. I.; Williams, R. O. 3rd. Influence of particle size on regional lung deposition - what evidence is there? Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 406, 1-10.

56. Pauly, J. L.; Stegmeier, S. J.; Allaart, H. A.; et al. Inhaled cellulosic and plastic fibers found in human lung tissue. Cancer. Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 1998, 7, 419-28.

57. Amato-Lourenço, L. F.; Carvalho-Oliveira, R.; Júnior, G. R.; Dos Santos Galvão, L.; Ando, R. A.; Mauad, T. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126124.

58. Porter, D. W.; Castranova, V.; Robinson, V. A.; et al. Acute inflammatory reaction in rats after intratracheal instillation of material collected from a nylon flocking plant. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. A. 1999, 57, 25-45.

59. Warheit, D. B.; Webb, T. R.; Reed, K. L.; Hansen, J. F.; Kennedy, G. L. Jr. Four-week inhalation toxicity study in rats with nylon respirable fibers: rapid lung clearance. Toxicology 2003, 192, 189-210.

60. Geiser, M.; Schurch, S.; Gehr, P. Influence of surface chemistry and topography of particles on their immersion into the lung’s surface-lining layer. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 94, 1793-801.

61. Geiser, M.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Kapp, N.; et al. Ultrafine particles cross cellular membranes by nonphagocytic mechanisms in lungs and in cultured cells. Environ. Health. Perspect. 2005, 113, 1555-60.

62. Liu, Y. Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; et al. Endocytosis, distribution, and exocytosis of polystyrene nanoparticles in human lung cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 13, 84.

63. Goodman, K. E.; Hare, J. T.; Khamis, Z. I.; Hua, T.; Sang, Q. A. Exposure of human lung cells to polystyrene microplastics significantly retards cell proliferation and triggers morphological changes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 1069-81.

64. Vattanasit, U.; Kongpran, J.; Ikeda, A. Airborne microplastics: a narrative review of potential effects on the human respiratory system. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 904, 166745.

65. Hwang, J.; Choi, D.; Han, S.; Jung, S. Y.; Choi, J.; Hong, J. Potential toxicity of polystyrene microplastic particles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7391.

66. Weiss, M.; Fan, J.; Claudel, M.; et al. Density of surface charge is a more predictive factor of the toxicity of cationic carbon nanoparticles than zeta potential. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2021, 19, 5.

67. Ramsperger, A. F. R. M.; Jasinski, J.; Völkl, M.; et al. Supposedly identical microplastic particles substantially differ in their material properties influencing particle-cell interactions and cellular responses. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127961.

68. Al Harraq, A.; Brahana, P. J.; Arcemont, O.; Zhang, D.; Valsaraj, K. T.; Bharti, B. Effects of weathering on microplastic dispersibility and pollutant uptake capacity. ACS. Environ. Au. 2022, 2, 549-55.

69. Fechine, G.; Rabello, M.; Souto Maior, R.; Catalani, L. Surface characterization of photodegraded poly(ethylene terephthalate). The effect of ultraviolet absorbers. Polymer 2004, 45, 2303-8.

70. Fernando, S. S.; Christensen, P. A.; Egerton, T. A.; White, J. R. Carbon dioxide evolution and carbonyl group development during photodegradation of polyethylene and polypropylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2007, 92, 2163-72.

71. Hofmann, W.; Sturm, R. Stochastic model of particle clearance in human bronchial airways. J. Aerosol. Med. 2004, 17, 73-89.

72. Sturm, R. Deposition and cellular interaction of cancer-inducing particles in the human respiratory tract: theoretical approaches and experimental data. Thorac. Cancer. 2010, 1, 141-52.

73. Huckaby, J. T.; Lai, S. K. PEGylation for enhancing nanoparticle diffusion in mucus. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2018, 124, 125-39.

74. Huck, B. C.; Murgia, X.; Frisch, S.; et al. Models using native tracheobronchial mucus in the context of pulmonary drug delivery research: composition, structure and barrier properties. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2022, 183, 114141.

75. Schiller, J. L.; Lai, S. K. Tuning barrier properties of biological hydrogels. ACS. Appl. Bio. Mater. 2020, 3, 2875-90.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].