Ion-shuttling memristor: towards ionic computing and neuromorphic sensing

Abstract

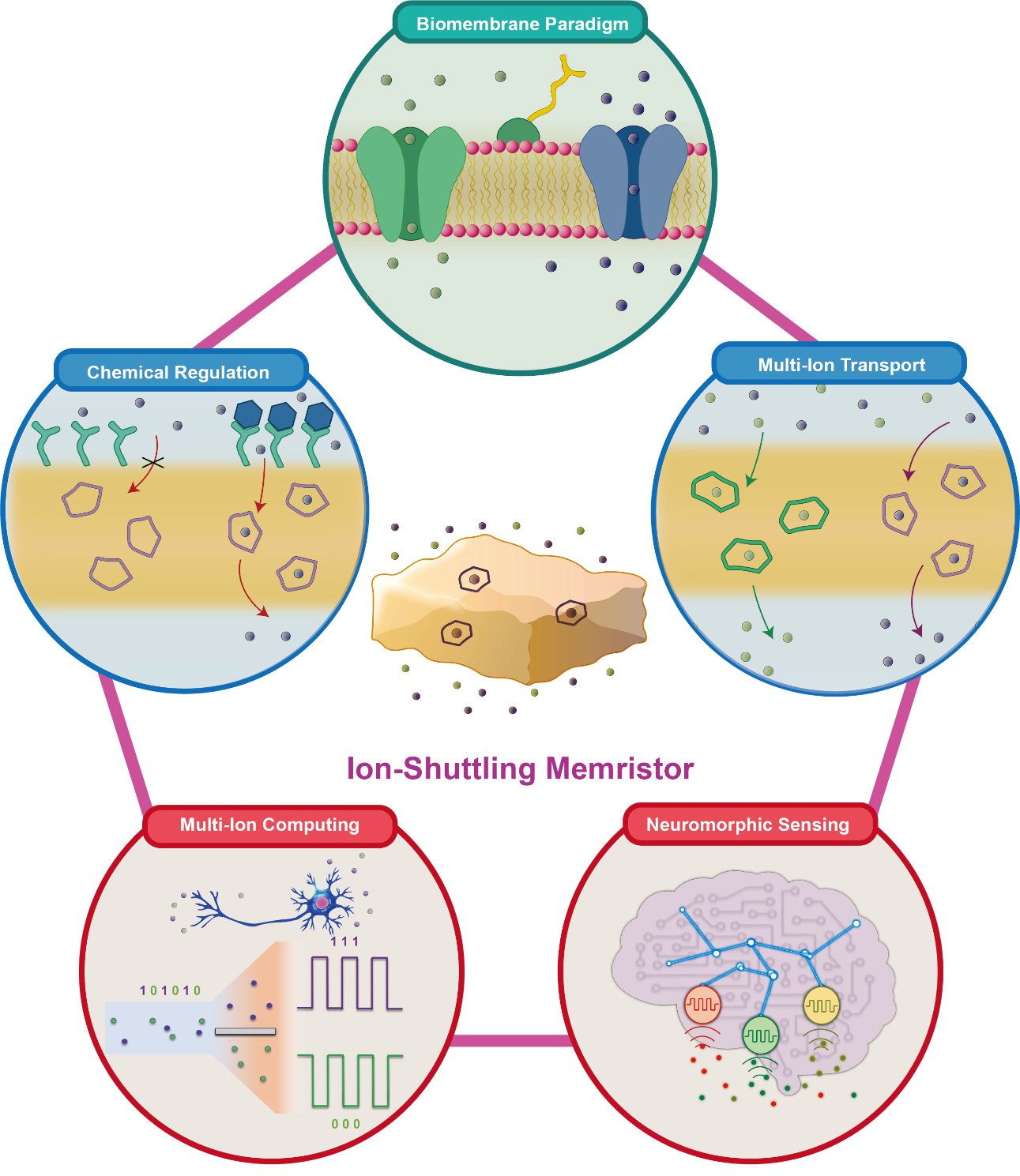

The iontronic memristor has attracted growing attention as a promising candidate for neuromorphic computing and sensing. Recently, a novel iontronic memristor, termed the ion-shuttling memristor (ISM), has been proposed. Benefiting from its bio-mimicking structure, ISM can emulate ion-selective neuron functions alongside basic functions. ISM has several potential advantages, including interfacial receptors and the incorporation of multiple ionophores. On this basis, ISM may pave the way for future applications, such as sophisticated multi-carrier neuromorphic computing and neuromorphic sensing.

Keywords

MAIN TEXT

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, power consumption has also skyrocketed due to the limitations of the von Neumann architecture, urging the need for a new computing paradigm. Inspired by the efficiency and parallel-processing ability of the brain, neuromorphic computing could be a promising solution, which requires device-level imitation of neurons. Hence, neuromorphic devices that can emulate the structure, characteristics, and functions of neurons at the hardware level have been fabricated. The memristor, a two-terminal neuromorphic device[1], has been engineered to imitate the complex plasticity and functions of neurons, enabling the hardware implementation of artificial neural networks[2].

In recent years, the iontronic memristor has been experiencing a surge[3]. Unlike traditional solid-state memristors, where electrons and holes serve as charge carriers, iontronic memristors utilize ions to transmit information. Although iontronic devices may be limited by slow carrier transport and fabrication challenges, their potential for sophisticated functions offers an unparalleled opportunity for efficient computing. While traditional solid-state neuromorphic devices suffer from structural discrepancies compared to their biological counterparts, iontronic devices operate in fluidic environments, better mimicking neurons. Iontronics can leverage fluidic matrices to simulate advanced functions, such as chemical-electric transduction[4]. Numerous iontronic architectures have been proposed, employing mechanisms such as structural deformation[5], concentration polarization[6], and gating[7]. These devices not only achieve neuromorphic functions comparable to solid-state systems but also benefit from unique properties, including chemical regulation capabilities[4].

Recently, a novel type of iontronic memristor, termed the ion-shuttling memristor (ISM), has been introduced[8] [Figure 1]. ISM mimics the structure of membrane-embedded biological potassium channels, comprising organic layers and ion-shuttling ionophores. The organic layer separates the inner and outer aqueous environments, mimicking the lipid membrane that blocks ion flux. Potassium-selective ionophores are incorporated within the organic layer to facilitate selective potassium ion transport, emulating the potassium channels. Hysteretic ion concentration changes induce memristive behavior, enabling the ISM to perform neuromorphic functions such as short-term plasticity and learning-forgetting cycles. Furthermore, exploiting ion-specific ionophores allows the ISM to perform ion-selective neuromorphic functions and replicate the ion selectivity observed in resting-state neurons, emulating the neuronal resting potential. Compared to previous fluidic memristors, in which ion transport occurs solely in the aqueous phase, the organic layer of ISM introduces an interfacial ion transfer process. The interface acts as a barrier to exclude interfering ions. Hence, this interfacial process allows ISM to discriminate ion species via ionophores, a task that is challenging for previous memristors operating in a pure aqueous phase, especially for similar ions such as sodium and potassium. This unique mechanism enables the realization of unprecedented ion-selective neuromorphic functions in ISM.

The ISM presents several potential advantages. First, the fluidic nature of the organic membrane and its facile fabrication process allow straightforward customization of ion selectivity and memristive characteristics. With a large library of ion-binding molecules identified in previous research, ionophores with desired properties such as selectivity, charge, and lipophilicity are available for fabricating ISM-like iontronic memristors. The incorporation of various functional ionophores through simple solvation procedures enables rapid development of devices with targeted ion specificity and memristive behavior.

Second, the structure of ISM can better imitate the neuronal membrane, providing an opportunity to emulate advanced neuronal functions. For example, receptors located on the neuronal membrane are essential for chemical regulation of neuronal activity. Similarly, by introducing recognitive receptors such as aptamers or antibodies, the interface of ISM may be engineered to respond to various chemical messengers. As the region near the organic-aqueous interface governs current, recognition processes at the interface can drastically alter the transport and memristive properties of ISM, making it more sensitive and tunable to chemical stimulation. The interface between the organic membrane and aqueous environment in ISM could mimic the lipid-water interface in neurons, providing a platform for receptor-like molecules that modulate memristive function through chemical messengers, further emulating biological regulatory mechanisms. In addition, in the neuronal membrane, diverse receptors and ion channels coexist and cooperate to achieve multifarious functions. Similarly, the fluidic nature of ISM allows integration of multiple ionophores and receptors through simple procedures, and the coexisting functional molecules could provide an opportunity to emulate the complex interactions of ion channels and receptors.

Utilizing ions, ISM and future iontronic devices could pave the way for sophisticated, parallel, brain-inspired computing. In neurons, neurotransmitters of different species can deliver signals in parallel, a process termed cotransmission. This underlies the high efficiency and versatility of neurons. Similarly, in iontronics, multiple ions can coexist and serve as carriers. This coexistence enables parallel information transmission via different ionic species and opens avenues for parallel computing. Enhancing the information-carrying capacity of carriers is also employed in other post-von Neumann computing strategies, such as photonic computing and spintronics. Similar to photonic computing, in which multiple wavelengths are used for parallel information processing[9], iontronics can utilize the total ion flux, consisting of different ion species, to achieve parallel computing. Input signals can be encoded and transmitted in parallel by these ion species. With ion-selective computing devices such as ISM, information carried by each species can be recognized and processed by corresponding devices. The computing results are then read out by ion-selective electrodes and converted into output signals. Moreover, the ion-selective neuromorphic functions provided by ISM make it possible to achieve carrier complexity along with brain-inspired computing, combining the advantages of unconventional computing strategies. As a result, ion-selective neuromorphic iontronics such as ISM may offer higher computing efficiency compared to conventional computing and brain-inspired electronics. In addition to parallel transmission, the rich chemical characteristics and readily accessible chemical interactions enable sophisticated regulation, which may further enhance the computing efficiency of ISM and future iontronic devices. Hence, ISM and ion-selective neuromorphic iontronics have great potential to improve computing efficiency.

Furthermore, ion-selective memristors are promising for neuromorphic ion-based sensing. Traditional ion sensors typically yield linear responses. However, biological sensory neurons exhibit history-dependent and non-linear behaviors, such as habituation and sensitization, enabling complex information processing at the sensor level. Sensory neurons extract key features from stimuli, thereby increasing computing efficiency. Ion-selective neuromorphic devices could emulate these biological sensing processes, offering a more sophisticated method of information transduction. Furthermore, neurons form circuits capable of identifying substances, learning from experience, and making decisions. Similarly, arrays of neuromorphic iontronic sensors with varied selectivity may achieve embodied intelligence, collaboratively recognizing, learning, and triggering appropriate responses in a closed-loop system, thereby breaking new ground for intelligent neuromorphic ion-sensing systems.

Despite these promising applications, ISM devices still face several challenges. First, optimizing selectivity to achieve high-performance sensing and avoid crosstalk in multi-ion computing remains an ongoing effort. This requires chemical modification of existing ionophores to obtain high binding affinity and specificity, and the introduction of reactive functional groups could offer additional opportunities for complex chemical modulation. Second, improving intrinsic device performance, such as enhancing long-term stability, is critical for practical applications. To prevent liquid displacement and evaporation, using more stable organic solvents with high viscosity and low vapor pressure could be beneficial. Another possible solution is transforming the organic liquid into organogels. Third, non-volatile memory is highly desirable for computing applications, and incorporating irreversible chemical reactions may provide a viable approach. Finally, integration into on-chip circuits is necessary for non-laboratory applications, and building microfluidic chips could be a feasible solution. Nonetheless, these challenges are surmountable, and ISM and future iontronic memristors could pave the way for advanced brain-inspired computing and sensing technologies.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conception and writing: Xie, B.; Yu, P.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

We acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22125406, 22550002, and T2596021 for Yu, P.), the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (F251009 and Z230022 for Yu, P.), and the National Basic Research Program of China (2022YFA1204500 and 2022YFA1204503 for Yu, P.).

Conflicts of interest

Yu, P. is an Associate Editor of Iontronics. Yu, P. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

2. Lin, P.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; et al. Three-dimensional memristor circuits as complex neural networks. Nat. Electron. 2020, 3, 225-32.

3. Xu, G.; Zhang, M.; Mei, T.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Xiao, K. Nanofluidic ionic memristors. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 19423-42.

4. Xiong, T.; Li, C.; He, X.; et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 2023, 379, 156-61.

5. Najem, J. S.; Taylor, G. J.; Weiss, R. J.; et al. Memristive ion channel-doped biomembranes as synaptic mimics. ACS. Nano. 2018, 12, 4702-11.

6. Wang, D.; Kvetny, M.; Liu, J.; Brown, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, G. Transmembrane potential across single conical nanopores and resulting memristive and memcapacitive ion transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3651-4.

7. Paulo, G.; Sun, K.; Di Muccio, G.; et al. Hydrophobically gated memristive nanopores for neuromorphic applications. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8390.

8. Xie, B.; Xiong, T.; Guo, G.; Pan, C.; Ma, W.; Yu, P. Bioinspired ion-shuttling memristor with both neuromorphic functions and ion selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2025, 122, e2417040122.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].