Hydrovoltaic energy and intelligence: where ions meet electrons

Abstract

Hydrovoltaic technology, which harvests electricity from water interactions with solid materials through ion-electron coupling, is approaching a transformative phase. While most studies focus on power output, the underlying ion dynamics inherently respond to environmental stimuli. This built-in sensing capability, though recognized, has rarely been developed into complex functional systems. Concurrently, neuromorphic engineering increasingly adopts ionic-electronic systems to create artificial synapses and neurons with inherent sensory and processing functions. This Perspective illustrates the natural convergence of these two fields, forming the basis of an emerging paradigm of hydrovoltaic intelligence. We show how the interfacial ion-electron coupling acts as a shared physical basis that links energy conversion, sensory perception, and neuromorphic processing, and ultimately opens a pathway toward brain-inspired hydrovoltaic intelligent media.

Keywords

MAIN TEXT

Hydrovoltaic technology

Hydrovoltaic technology refers to a broad family of interfacial energy conversion processes in which water in either liquid or vapor form interacts with solid surfaces to induce charge separation and transport, which can subsequently be converted into electrical energy. Since the early discoveries that moving water can sustain electronic currents in carbon-based materials, this field has expanded rapidly and now encompasses evaporation-, humidity- and droplet-driven electricity generation, together with a growing set of newly identified electrokinetic phenomena at solid-liquid interfaces.

Recent advances in device architectures, material engineering and interfacial chemistry have enabled substantial improvements in electrical output across these platforms. For instance, humidity-driven generators now achieve power densities of approximately 6 W/m2 by incorporating redox couples[1] and evaporation-driven MXene modules approach 1 W/m2[2]. Droplet-based devices can produce kilovolt-level transient voltages and instantaneous power densities on the order of 105 W/m2 by exploiting collective droplet dynamics[3] and Kelvin-type architectures[4]. Although individual humidity- or evaporation-driven devices typically operate at volt-level output, arrayed configurations can reach kilovolt voltages[5,6]. These achievements demonstrate that hydrovoltaic systems can be engineered to harvest low-grade environmental energy and power distributed or wearable electronics.

These performance advances arise from an improved understanding that diverse hydrovoltaic effects are fundamentally governed by how dynamic water-solid interactions reorganize interfacial ions and molecules, thereby driving electronic responses in the underlying solids. In droplet-based systems, the spreading and retraction of a droplet dynamically modulate the interfacial capacitance and charge within the electric double layer (EDL), inducing a capacitive electrical response in the underlying conductors. In architectures with dielectric-coated electrodes, additional ion-electron exchange and electrostatic induction at the water-dielectric interface can further enhance the generated signal.

In evaporation-driven systems, capillary flow through nanoscale pores or ultrathin surface films establishes a streaming potential, where the liquid flow entrains mobile counterions along charged nanochannels. In some cases, the escape of molecules during evaporation from a thinning interfacial liquid layer appears to directly perturb electronic carriers inside the solid, providing an additional evaporating potential[7]. In humidity-driven systems, moisture adsorption within a hygroscopic material facilitates ion dissociation and mobilization. An intrinsic chemical or structural asymmetry then establishes a gradient in electrochemical potential, driving directional ion diffusion and resulting in a macroscopic electrical potential. Beyond these classical mechanisms, hydroelectronic drag provides a purely electronic pathway for coupling liquid motion to solid-state currents. Charge-density fluctuations in the liquid generate evanescent electromagnetic fields that penetrate into the solid. The liquid flows along the surface, slightly biasing these fields, transferring net momentum, and exerting a friction-like force on conduction electrons, thereby producing an electronic current even in the absence of mobile ions[8].

Although hydrovoltaic research initially focused on power generation, the interfacial ion-electron processes inherently endow these systems with potent sensing capabilities. Environmental stimuli fundamentally reshape the kinetics and thermodynamics for ions at water-solid interfaces. Temperature primarily affects how fast ions move and react by modulating diffusion and interfacial kinetics. Humidity controls the amount of adsorbed water, thereby setting the thickness and continuity of the ion-conducting water layer. Chemical composition, including salts, pH and specific molecules, regulates ion activity and surface binding. These stimuli alter the EDL properties and the charge transfer dynamics at the interface, resulting in corresponding changes in electrical outputs such as open-circuit voltage, short-circuit current, capacitance and impedance. This mechanism forms the basis for various sensing applications. Respiratory monitoring can be realized by integrating hydrovoltaic fibers into textiles, where breath-induced changes in humidity and airflow are converted into electrical signals for real-time tracking[9]. For pressure and tactile sensing, devices transduce subtle variations in local moisture distribution caused by mechanical loading into electrical readouts[10]. In biochemical sensing, electrolytes and metabolites in biofluids reshape ion distributions and interfacial reactions, altering ionic strength, binding affinity, or redox activity at sensor interfaces, thereby generating detectable electrical signals for wearable sweat monitoring, even though practical sweat-based sensors must still address fluctuating sweat rates and salt accumulation that can induce signal drift and limit device lifetime[11,12].

These advances show that hydrovoltaic systems already use water-solid interfaces for energy harvesting and passive sensing. Yet, current hydrovoltaic platforms remain largely non-intelligent compared with the brain, where ions also meet electrons in a water-rich medium.

Convergence with brain intelligence

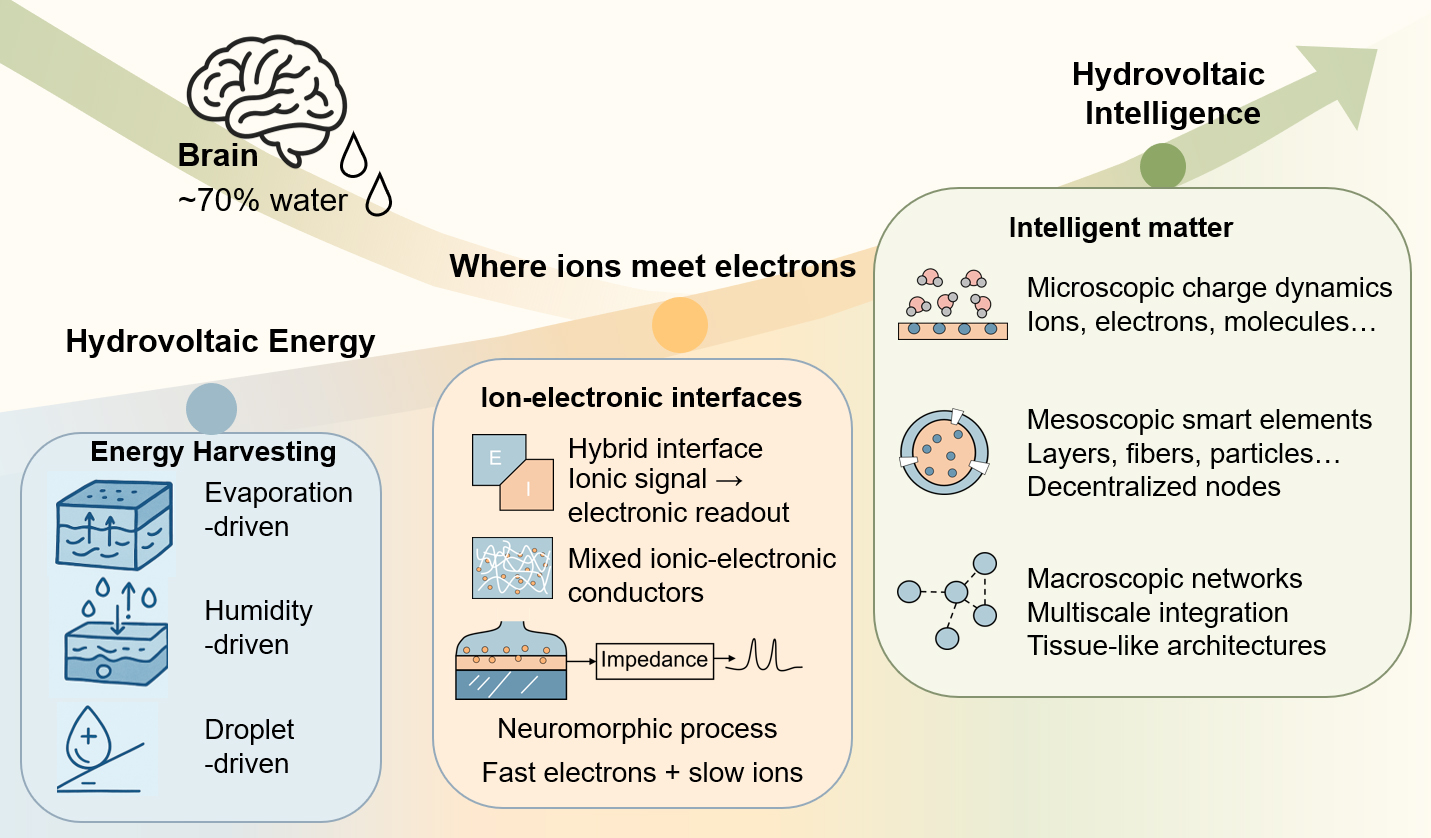

The human brain serves as a compelling biological model of how water, ions and energy can be integrated to form complex, intelligent systems. Composed of about 70% water, the brain consumes approximately 20 W while supporting billions of neurons and trillions of synaptic connections that collectively enable high-level cognitive functions. It relies on transmembrane ionic flux and synaptic neurotransmission to generate, propagate, and integrate electrochemical signals[13]. This remarkable integration of aqueous ionic dynamics with extreme energy efficiency illustrates that intelligent behavior can arise from a highly organized, water-rich medium. While current hydrovoltaic systems remain far simpler than neural tissue, this biological precedent supports a conceptual shift from treating hydrovoltaic systems merely as energy harvesters and sensors toward recognizing their potential as a platform for hydrovoltaic intelligence [Figure 1]. In this context, hydrovoltaic intelligence refers to a class of bioinspired artificial systems in which water-solid interfacial ion-electron coupling governs the dynamics of sensing, memory and simple learning-like and adaptive responses.

Figure 1. Convergence of hydrovoltaic energy and brain intelligence, inspiring the path toward hydrovoltaic intelligence powered by ion-electron coupling.

A fundamental distinction between biological systems and conventional electronics lies in the nature of their charge carriers. Ionic transport is influenced by solvation, electrochemical reactions and steric constraints, leading to mobilities that are several orders of magnitude lower than those of electrons and holes in semiconductors. At the same time, ions carry chemical identity, hydration shells and species-specific redox behavior, so their dynamics are rich and distinguished from charge transport in electronic systems. Although ionic signals are slower, they offer intrinsic advantages in chemical specificity and environmental compatibility, enabling direct encoding of chemical information at solid-liquid interfaces and operation in regimes inaccessible to conventional electronics.

Building on these properties, ionic circuit elements based on ion-selective nanochannels, asymmetric porous structures, polyelectrolytes and ion-exchange membranes have been used to realize ionic analogs of diodes and transistors. Nanofluidic memristors, such as sub-nanometer slits[14] or polymer-brush nanopipettes[15], leverage ion rearrangement in highly confined and charged channels to create history-dependent conductance and enable synaptic-like dynamics. These devices provide a fluidic platform for emulating memory and computation in biological synapses. Despite these advances, the structural sophistication, functional density and long-term stability of ionic circuits remain far inferior to biological systems.

To bridge this gap, a promising path is to combine electronic technologies with ionic functionalities through ion-electron coupling. One straightforward route is to directly interface ionic conductors with electronic electrodes. For example, ionic conductors interfaced with electronic electrodes can form highly sensitive pressure sensors utilizing EDL capacitance[16]. In our recent work, an artificial neuron was realized by coupling a single nonlinear electrochemical element with a solid-state memristor for neuromorphic sensing. This minimal architecture integrates fast electronic switching with slow, nonlinear ionic dynamics, generating spiking activity across five orders of magnitude in frequency, which is potentially useful for neuromorphic sensors and computing systems that must handle signals ranging from slow environmental changes to fast transient events[17].

A complementary route utilizes mixed ionic-electronic conductors (MIECs), where ionic and electronic transport coexist within a single material. In representative organic MIECs such as poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) and related conjugated polymers, electronic charge moves along the π-conjugated backbones, while mobile ions reversibly penetrate the bulk for charge compensation and conductivity modulation. This volumetric coupling underlies the operational basis of organic electrochemical transistors. The softness and solution processability of these polymers facilitate fabrication on flexible substrates and direct interfacing with ionic environments. Recent advances with organic electrochemical transistors have demonstrated artificial neurons capable of generating spikes, emulating synaptic plasticity and encoding sensory signals for neuromorphic sensing[18]. Moreover, this concept has been extended into three-dimensional, tissue-like structures through the demonstration of hydrogel-based transistors[19].

Collectively, these advances in brain-inspired iontronic architectures and water-driven hydrovoltaic interfaces converge toward a common direction. In this emerging picture, interfacial ion-electron coupling acts as a shared physical basis that links energy conversion, sensory perception, and neuromorphic processin. This motivates the next step of our Perspective: how insights from brain intelligence may inspire the evolution from hydrovoltaic energy toward hydrovoltaic intelligence by fully exploiting the underlying mechanism of ion-electron coupling.

Toward hydrovoltaic intelligence

Biological intelligence provides a useful template for how water, ions and soft matter can be hierarchically organized across multiple scales. From hydrated molecular assemblies to membranes and organelles and finally to interconnected neural circuits, this organization ensures that local interactions at nanoscale interfaces define selectivity and transduction, mesoscopic structures such as ion channels and synapses implement sensing and memory and large-scale networks give rise to emergent functions. This multilevel dynamic therefore suggests an analogous strategy for designing hydrovoltaic intelligent media.

Conceptually, the development of hydrovoltaic intelligence can be divided into three hierarchical stages. At the microscopic level, the focus is on water and ion dynamics at solid-liquid interfaces, which define the fundamental mechanisms of charge generation, signal transduction and coupling to electronic carriers. At the mesoscopic level, these mechanisms are embodied in ionic-electronic building blocks that locally convert water-driven ionic motion into electrical signals, store history in internal states, or perform simple preprocessing of inputs. At the macroscopic level, large numbers of such mesoscale elements are embedded in wearables, biointerfaced modules or distributed within soft or porous media and interconnected into networks. Interactions among many nodes then give rise to collective behavior such as decentralized sensing, adaptive response and, ultimately, system-level intelligent functions that are absent in any individual component.

Realizing this vision requires addressing several fundamental scientific and engineering challenges. From a materials design perspective, the objective is to create multiscale architectures that support hydrovoltaic intelligence functionalities. At the molecular and nanoscale, the material composition, morphology, functional groups, and surface charge should be optimized to improve interfacial processes such as charge separation, selective ion transport, and electron transfer, thereby enhancing energy conversion or signal transduction efficiency. At larger scales, the geometry of pores, interlayer spacing and surface structures needs to be adjusted to regulate charge and mass transport pathways in a controlled manner. At the same time, these materials should retain mechanical robustness and chemical stability under fluctuating aqueous conditions, with resistance to degradation and contamination during long-term operation.

Extending such multiscale materials design into three-dimensional hydrovoltaic intelligent media requires advanced integration strategies. One aspect concerns device-level integration, where the goal is to organize numerous microunits into coordinated networks with controlled connectivity and signal pathways. Here, interfaces linking ionic, electronic and structural components must provide stable, low impedance routes for water transport, charge conversion and signal propagation. A second aspect concerns material-level integration, which aims to construct tissue-like three-dimensional bodies in which porous solid frameworks, soft ionic conductors and electronic pathways coexist within the same volume and jointly support transport and mechanical robustness. Together, these demands motivate hybrid integration routes that combine adapted microfabrication, multi-material printing and self-assembly to build hydrated, hierarchically organized architectures, whose engineered connectivity and environment-responsive interactions support brain-inspired, network-level adaptive behaviour.

At the theoretical level, a major task is to model strongly coupled ion-electron-molecular interactions across huge orders of magnitude in time, length and energy scales. Existing quantum mechanics, molecular mechanics and continuum mechanics are often inadequate for such multi-phase, multi-field interfacial systems. It is therefore important to develop multiphase interfacial models and multiscale dynamic simulation methods that specifically account for interfacial charge transfer under realistic hydrovoltaic conditions.

In the pursuit of next-generation intelligent systems, hydrovoltaic intelligence invites us to view water not merely as a working fluid, but as an active medium that integrates energy harvesting and information processing at water-ion-solid interfaces. This approach enables systems to perceive, process and respond to their environment through unique ion-electron coupling. The promise of such systems lies not in faithfully replicating neural architectures, but in their capacity to leverage ion and electron dynamics to achieve truly embedded and adaptive intelligence.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conducted the literature analysis, interpretation, and manuscript writing: Li, J.

Conceived the perspective and participated in drafting and critically revising the manuscript: Yin, J.; Guo, W.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFA1409600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (T2293691, T2293694, 12372329), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20253057, BK20243065), the Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Mechanics and Control for Aerospace Structures (MCAS-I-0125Y01, MCAS-I-0525K01), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (NC2023001, NJ2023002, NJ2024001), and the Fund for the Prospective Layout of Scientific Research at NUAA (Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics).

Conflicts of interest

Jun Yin is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Iontronics. Jun Yin was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Li, P.; Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; He, T.; Cheng, H.; Qu, L. Interfacial ion-electron conversion enhanced moisture energy harvester. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6600.

2. Bae, J.; Kim, M. S.; Oh, T.; et al. Towards Watt-scale hydroelectric energy harvesting by Ti3C2Tx-based transpiration-driven electrokinetic power generators. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 123-35.

3. Deng, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, K.; et al. Collective electricity generation over the kilovolt level from water droplets. Nano. Lett. 2025, 25, 7457-64.

4. Li, Y.; Qin, X.; Feng, Y.; et al. A droplet-based electricity generator incorporating Kelvin water dropper with ultrahigh instantaneous power density. Droplet 2024, 3, e91.

5. Deng, W.; Feng, G.; Li, L.; et al. Capillary front broadening for water-evaporation-induced electricity of one kilovolt. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4442-52.

6. Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; He, T.; et al. Bilayer of polyelectrolyte films for spontaneous power generation in air up to an integrated 1,000 V output. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 811-9.

8. Coquinot, B.; Bocquet, L.; Kavokine, N. Hydroelectric energy conversion of waste flows through hydroelectronic drag. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2411613121.

9. Li, H.; Li, X.; Li, X.; et al. Multifunctional smart mask: Enabling self-dehumidification and self-powered wearables via transpiration-driven electrokinetic power generation from human breath. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 142083.

10. Hu, Q.; Hong, M.; Wang, Z.; et al. Microbial biofilm-based hydrovoltaic pressure sensor with ultrahigh sensitivity for self-powered flexible electronics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 275, 117220.

11. Ge, C.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Ion transport-triggered rapid flexible hydrovoltaic sensing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8110.

12. Zhang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Integrated wearable sensors based on sweat-driven hydrovoltaic chips for metabolite and electrolyte monitoring. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 13282-91.

13. Hodgkin, A. L.; Huxley, A. F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 1952, 117, 500-44.

14. Robin, P.; Emmerich, T.; Ismail, A.; et al. Long-term memory and synapse-like dynamics in two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Science 2023, 379, 161-7.

15. Xiong, T.; Li, C.; He, X.; et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 2023, 379, 156-61.

17. Li, J.; Zhao, W.; Fu, C.; et al. An ion-electronic hybrid artificial neuron with a widely tunable frequency. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7911.

18. Harikesh, P. C.; Tu, D.; Fabiano, S. Organic electrochemical neurons for neuromorphic perception. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 525-36.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].