Fiber-reinforced CNT-integrated quartz fabrics as multifunctional electrodes for structural lithium-ion batteries

Abstract

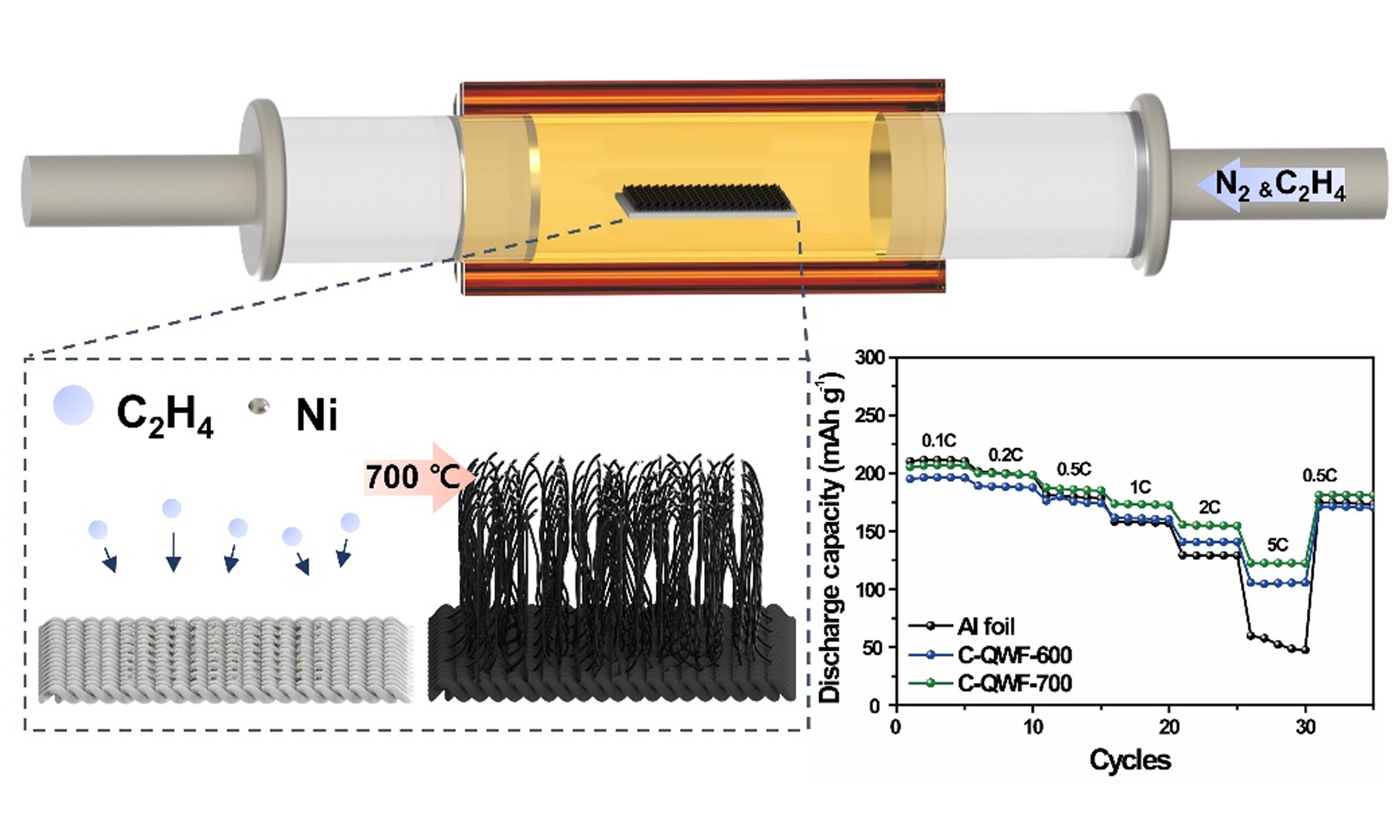

The long-term stability of lithium-ion batteries is a critical factor limiting their broader adoption in multifunctional and structural energy storage systems. However, conventional metallic current collectors tend to be heavier and less mechanically adaptable than fiber-based materials such as quartz woven fabrics (QWFs), particularly when structural integration is required. Quartz fabrics, composed primarily of silica, offer high thermal stability, mechanical robustness, and low areal weight, making them attractive candidates for multifunctional electrode platforms. In this study, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) were directly grown on QWFs via chemical vapor deposition, using Ni nanoparticles as catalysts and C2H4 as the carbon source. The growth process was optimized by varying temperature over a 2-h duration to form uniform, conductive CNT networks. The resulting CNT-coated QWFs functioned dually as current collectors and active electrode supports, delivering an initial discharge capacity of 201.54 mAh g-1 at a 0.1 C-rate. The electrodes retained 89.8% of their initial capacity after 50 cycles at a

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Structural batteries, which combine mechanical load-bearing capabilities with energy storage functions, represent a transformative approach to lightweight system design, particularly in applications such as electric vehicles (EVs), unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and aerospace systems[1-3]. In conventional energy storage architectures, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are merely passive components, contributing a significant portion of the total system weight without bearing any structural loads. As the demand for higher energy densities, safety, and material efficiency grows, the development of multifunctional materials that can simultaneously store energy and reinforce structural integrity is becoming increasingly crucial[4,5]. A key challenge in the realization of structural batteries is the identification of electrode materials that exhibit both excellent electrochemical properties and mechanical robustness. Fiber-reinforced composites have emerged as promising candidates due to their tunable mechanical properties, formability, and ability to host active materials. Among the various fibers explored, carbon fibers offer high electrical conductivity but relatively lower chemical and thermal stability, whereas silica-based fibers, such as quartz woven fabrics (QWFs), provide superior thermal resistance, chemical inertness, and dimensional stability[5-8]. These properties make QWFs especially attractive for multifunctional energy storage in extreme or thermally demanding environments.

Despite their mechanical and thermal advantages, silica-based fibers exhibit inherently poor electrical conductivity, limiting their role as current collectors or active electrode components in LIBs[9]. To address this issue, several strategies have been explored, including the deposition of metal nanoparticles (e.g., Ni, Cu) or conductive carbon layers onto the fiber surfaces[10]. These modifications aim to bridge the gap between mechanical integrity and electrochemical performance, enabling the development of structurally integrated electrodes. Among conductive additives, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been widely investigated due to their outstanding electrical conductivity, high aspect ratio, mechanical resilience, and ability to form percolated electron transport networks[11]. CNTs not only enhance charge transport across the electrode but also improve the interfacial contact between active materials and current collectors. In addition, surface modification of cathode materials such as NCM811 via carbon coating has been actively explored to enhance their structural and interfacial stability[12-15]. Moreover, the one-dimensional nanostructure of CNTs enables mechanical interlocking and reinforcement within the electrode matrix, which is particularly valuable in structural battery designs where mechanical integrity must be maintained during battery operation. Recent advancements have demonstrated the feasibility of growing CNTs directly on fiber surfaces using chemical vapor deposition (CVD) techniques, which enable uniform, vertically aligned CNT arrays anchored via metal catalysts such as nickel[16-19]. This method ensures strong bonding between the CNTs and the underlying fabric, eliminating the need for additional binders or conductive agents. It also allows for precise control over CNT growth density and morphology by tuning reaction parameters such as temperature, gas composition, and catalyst distribution[20-23].

In this study, we propose and demonstrate a multifunctional electrode architecture based on

EXPERIMENTAL

Carbon nanotube growth mechanism

The CNT growth mechanism of SiOx follows the vapor-liquid-solid growth mechanism. To grow CNTs on a QWF, Ni metal catalyst particles with a thickness of 10 nm were deposited on the QWF using a

Material characterizations

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were determined using the X-ray diffractometer (MiniFlex 600, BD71000481-01) in the wavelength range of 1.5405 Å, angle range of 10° ≤ 2θ ≤ 70°, and step width of 0.01°. The microstructure and morphology of the sample were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; EM 30, GSEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM; TF30ST, FEI, NEOARM,

Coin cell fabrication

Al foil electrode supports were used to prepare the electrode supports for C-QWF-600 and C-QWF-700 and were also used as a comparison group for CNT growth. The electrode slurry was mixed with cathode active materials (NCM811), conductive material (super P), and polymer binder (polyvinylidene fluoride) in the weight ratio of 80:10:10 using a mixer; then, slurry casting was performed using a doctor blade at a thickness of 250 μm on C-QWF-600 and C-QWF-700 and a thickness of 200 μm on Al foil. Then, the electrode was dried in a vacuum oven at 50 and 80 oC overnight. The electrodes were punched into 12 mm circular disks. For evaluating the electrochemical performance, a lithium coin cell was fabricated as a CR2032 coin cell in an Ar-filled glove box. For the half-cell tests, lithium metal was used as the counter electrode, and the fabricated C-QWF-600, C-QWF-700, and Al foil electrodes were used as the working electrodes. Glass microfiber filter (Grade GF/D, Whatman) was used as the separator and 1.15 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/diethyl carbonate (1:1 vol%) was used as the electrolyte. The lithium metal was punched into circular disks with diameters of 14 mm.

Electrochemical test

Electrochemical tests were performed with 2032 coin-type half-cell with Li metal as the counter. The cell was assembled in a glove box filled with argon gas containing 0.1 ppm less than H2O and O2. The electrolyte was prepared by dissolving 1.15 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/diethyl carbonate (1:1 vol%). The glass fiber membranes (GF/D, Whatman) were used for the separators with a thickness of 1.55 mm. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed using WonATech (WBCS3000 L) in a cut-off voltage range of 3.0 V to 4.3 V (vs. Li/Li+) at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s-1. The galvanostatic measurements were carried out in a cut-off voltage range from 3.0 V to 4.3 V (vs. Li/Li+) using an automatic battery cycler (MIHW-200-160CH-B, Neware). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed in the frequency range of 100 mHz to 1MHz with a signal peak to peak amplitude of 5 Mv at the open circuit potential of the cell. For impedance spectroscopy, the ESR (Equivalent Series Resistance) was measured as the real part of the impedance (Zreal) at a frequency of 1 kHz using a multi-channel battery tester (BioLogic VMP3, France).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

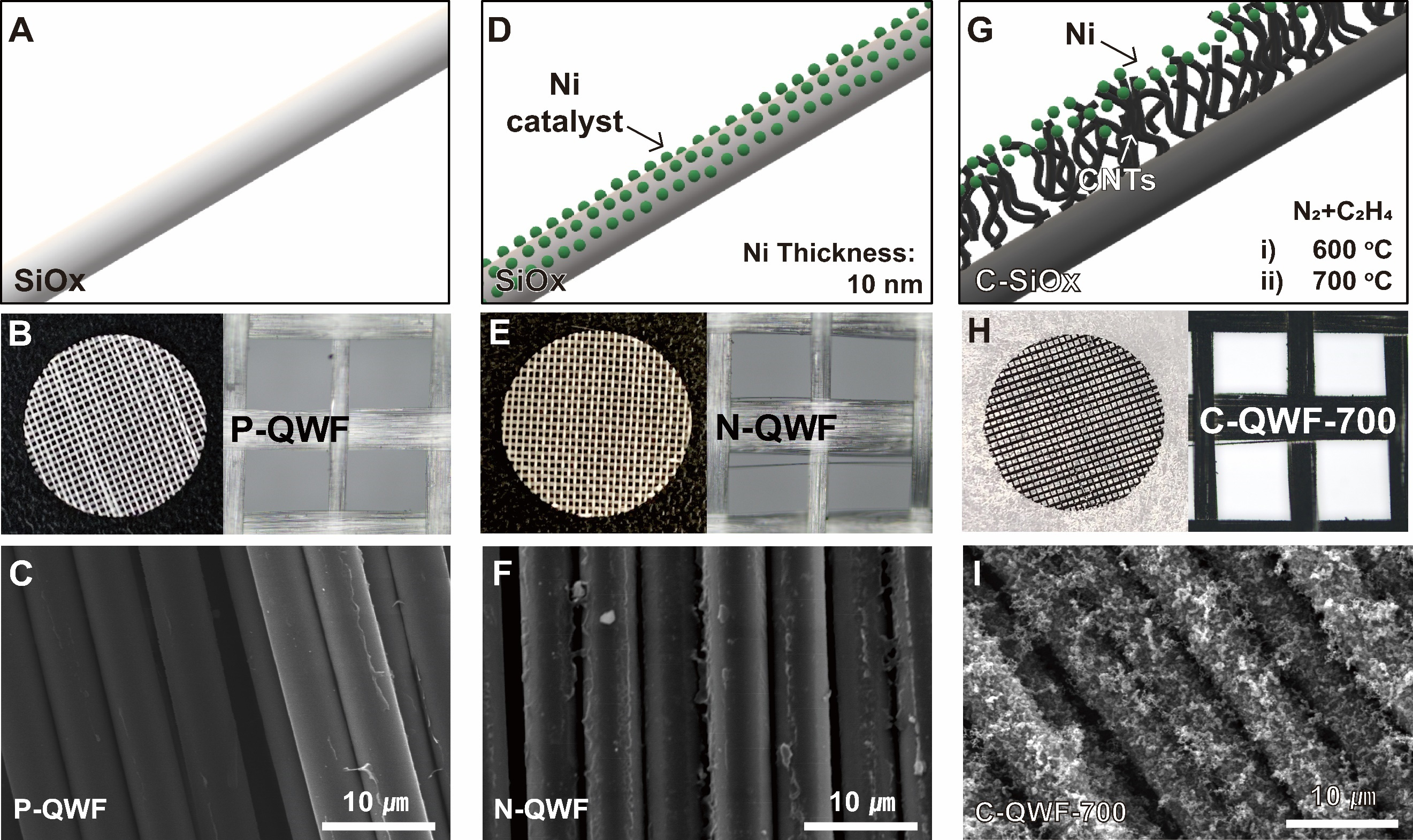

SiO2 fabrics for structural batteries were prepared as electrode supports through Ni sputtering followed by CVD. Since SiO2 fabric has inherently low electronic conductivity, Ni nanoparticles were first deposited onto the surface of QWF to enhance its conductivity. Subsequently, the CVD process was conducted at 600 and 700 °C for 2 h to determine the optimal temperature for CNT growth. The morphology and CNT growth were confirmed using SEM imaging. A simplified schematic of the experimental process is presented in Figure 1. Figure 1A-C illustrates the SiO2 fabric (QWF) along with SEM images at low and high magnifications. Figure 1C confirms that the silica fiber structure of pristine QWF (P-QWF) remains intact, which correlates with its highest tensile strength [Supplementary Figure 1]. After Ni sputtering, the

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of (A) pristine quartz woven fabric (P-QWF) electrode, (D) Ni-sputtered quartz woven fabric (N-QWF) electrode, and (G) quartz woven fabric (QWF) electrode. Low- and high-magnification optical images of the top view of (B) P-QWF, (E) N-QWF, and (H) C-QWF-700. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the top view of the (C) P-QWF, (F) N-QWF, and

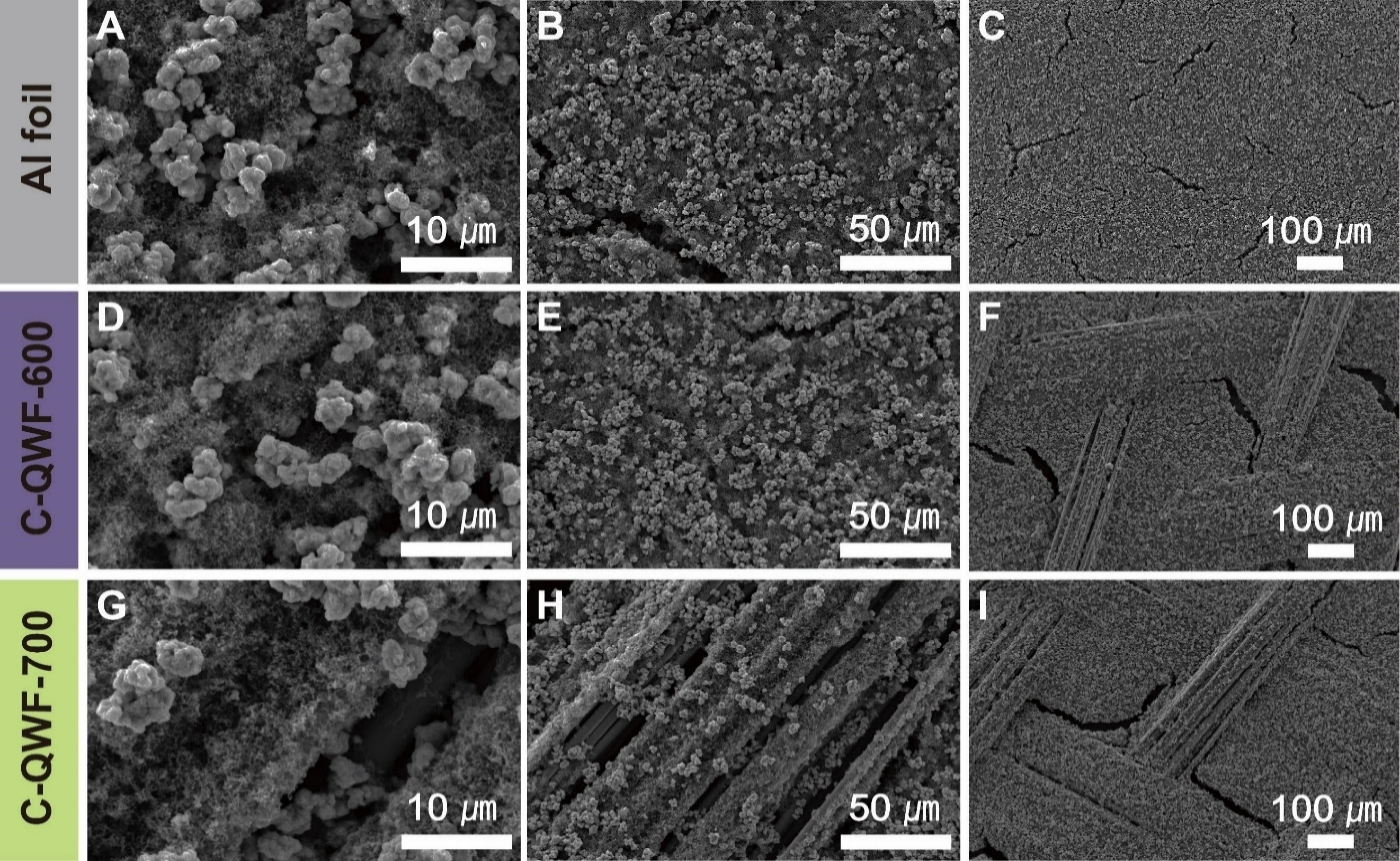

Figure 2 shows the SEM image of the electrode surface from the top view, including Al foil Figure 2A-C,

Figure 2. SEM image of electrodes (A-C) Al foil, (D-F) C-QWF-600, and (G-I) C-QWF-700. SEM: Scanning electron microscopy; QWF: quartz woven fabric.

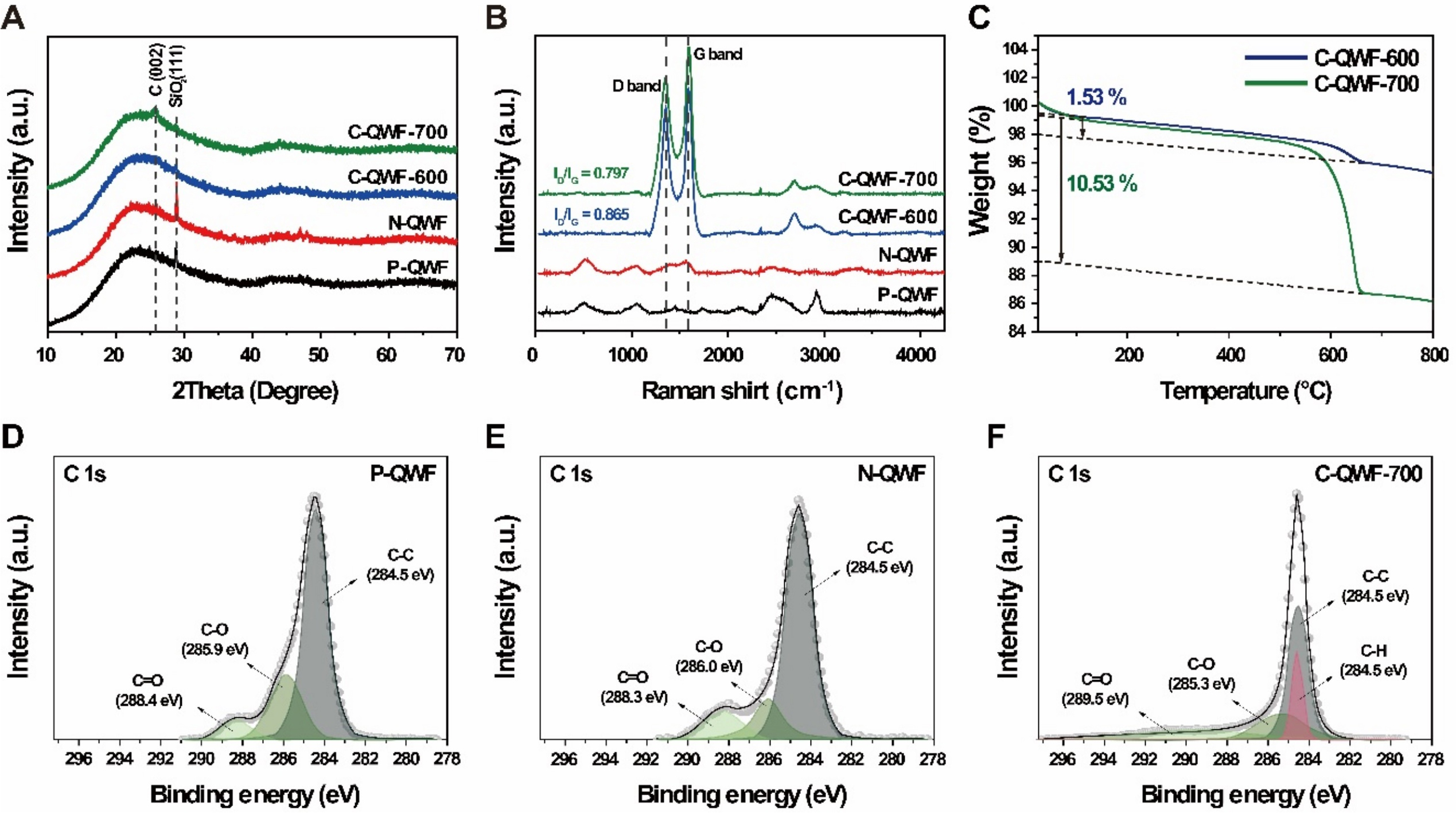

Figure 3 shows the carbon properties of the grown CNTs and changes in the crystal structure of the support corresponding to the changes in heat treatment time during the CVD process. Figure 3A shows the XRD patterns of the QWF electrode supports (P-QWF, N-QWF, C-QWF-600, and C-QWF-700). The XRD results indicate that the broad peak in the range of approximately 2θ = 15°-30° in P-QWF is related to amorphous silica, which is maintained without significant change even after the Ni deposition process. The intensity of the amorphous silica peak decreases in the C-QWF-600 and C-QWF-700 electrode supports owing to the growth of CNTs on the Ni catalyst, with a greater reduction in the C-QWF-700 electrode support than in the C-QWF-600 support. Moreover, the peak at 2θ = 27.64° corresponds to the (002) plane of the graphite lattice. This confirmed the graphitization at 700 °C. This result is consistent with the SEM images. Figure 3B shows the Raman spectra of the QWF electrode supports (P-QWF, N-QWF,

Figure 3. (A) X-ray diffraction patterns of the QWF electrodes support (10°-70°), (B) Raman spectroscopy of QWF electrodes support, (C) TGA curves of CNT quantity of C-QWF-600, C-QWF-700; C 1s XPS spectra of (D) P-QWF, (E) N-QWF, and (F) C-QWF-700. QWF: Quartz woven fabric; TGA: thermogravimetric analysis; CNT: carbon nanotube; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; P-QWF: pristine QWF; N-QWF: Ni-coated QWF; C-QWF: CNT-coated QWF.

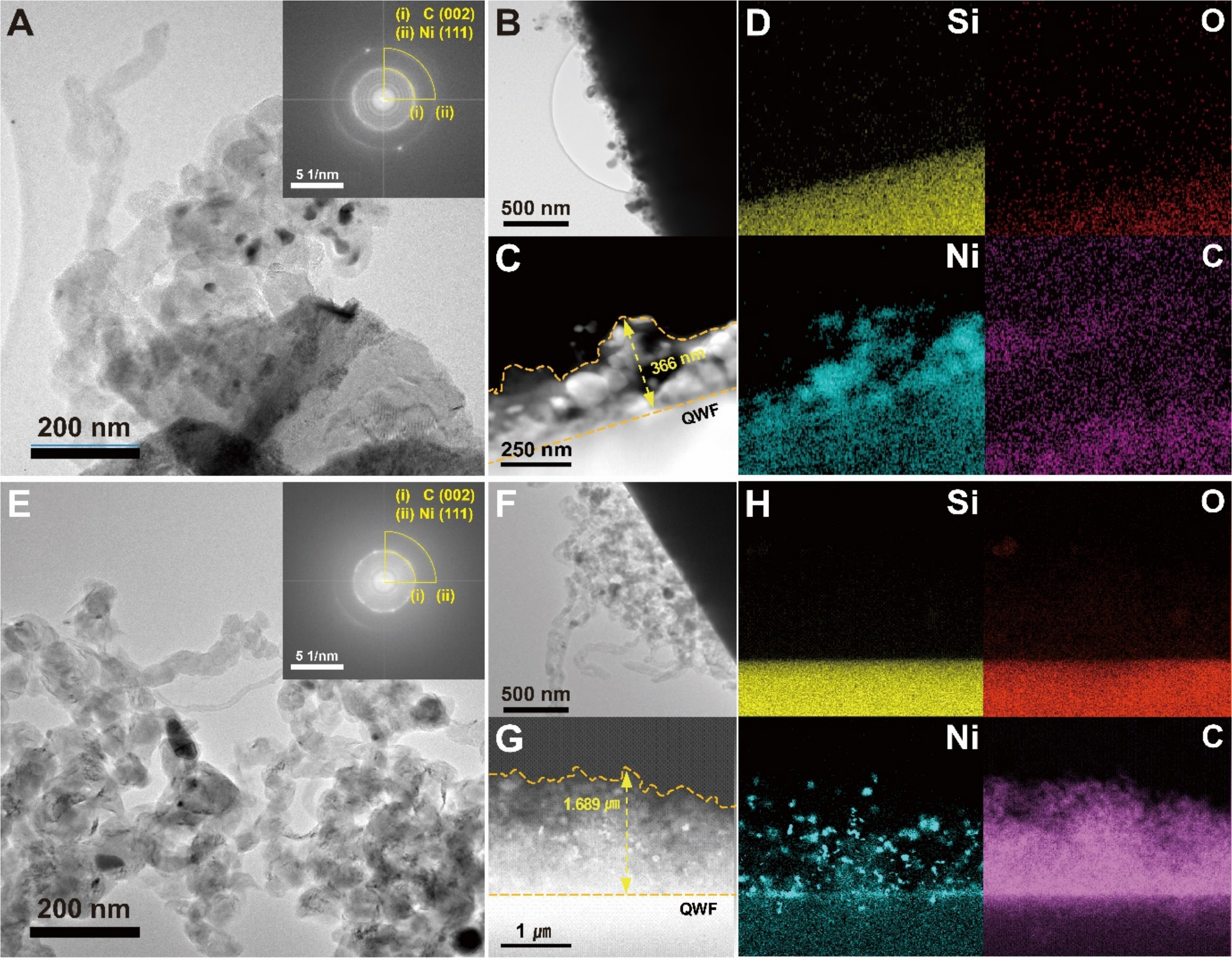

Figure 4 presents the results of the TEM analysis, conducted to examine the surface morphology of the particles and the distribution of Ni and CNTs. As shown in Supplementary Figure 6, TEM images were utilized to evaluate the uniformity and consistency of the deposited Ni layer. The results confirmed that the Ni layer closely adhered to the intended thickness of 10 nm, ensuring the reliability of the deposition process. Figure 4A-C and Figure 4E-G illustrates the distribution of CNTs on the C-QWF-600 and

Figure 4. (A and B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of C-QWF-600 electrode support, (C and D) Energy dispersive

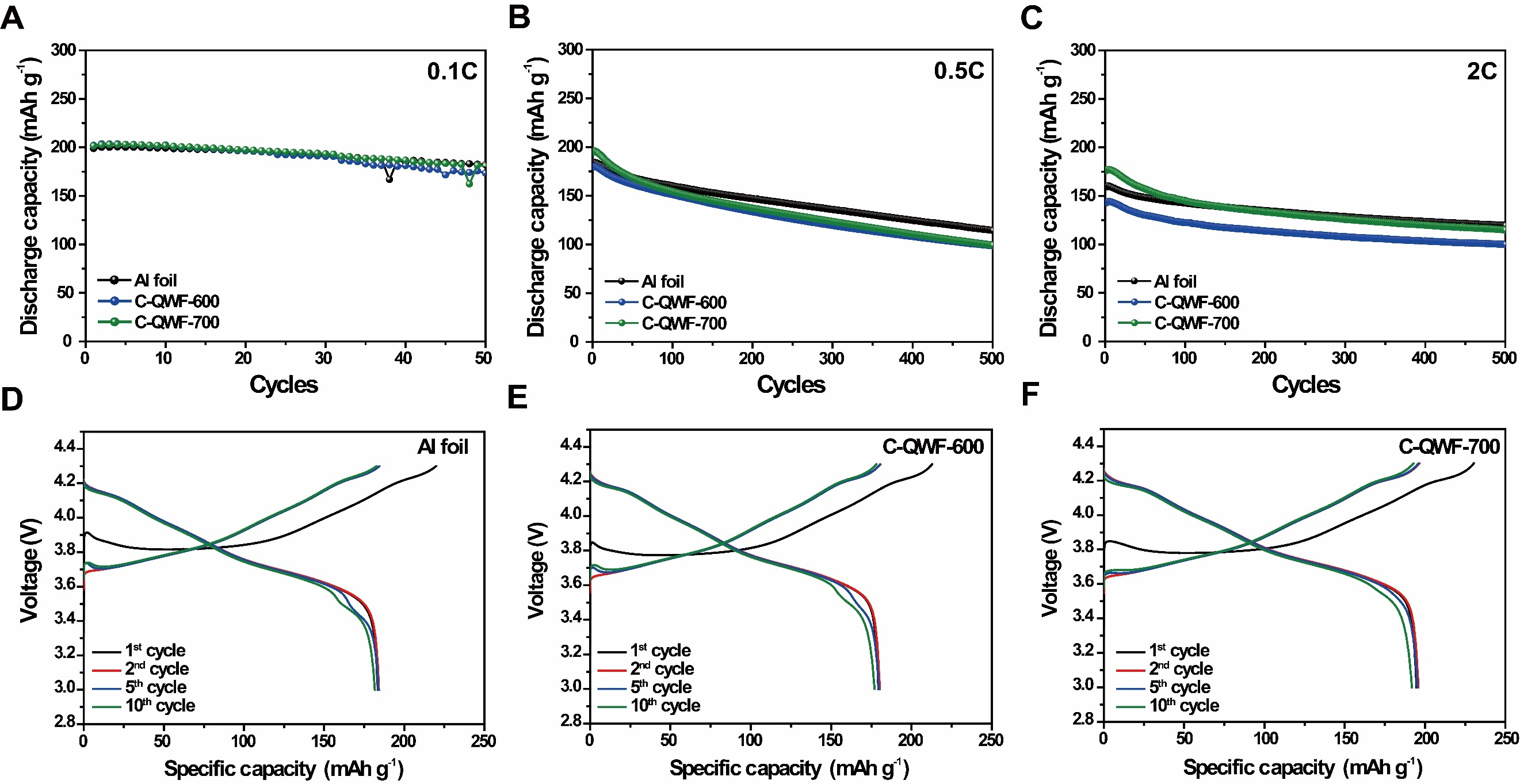

In order to investigate the effect of Ni as a catalyst on the electrolyte, CV tests were conducted within the voltage range of 3.0-4.3 V (vs. Li/Li+). Supplementary Figure 7 presents a comparative analysis of N-QWF and P-QWF, demonstrating that no significant additional redox peaks or side reactions were observed. This indicates that Ni does not induce noticeable side reactions with the electrolyte under the operating voltage conditions, confirming the absence of irreversible reactions between the Ni catalyst and the electrolyte. Figure 5 presents the electrochemical characteristics of the QWF electrode supports during charge and discharge, based on cycle performance tests conducted at various charge and discharge rates. These tests were performed using NCM811 as the cathode material (theoretical capacity: 275 mAh g-1) to optimize the structural cell for high energy density. Figure 5A displays the discharge capacity of NCM811 applied to Al foil and QWF electrode supports (C-QWF-600 and C-QWF-700) over 50 cycles at a 0.1 C-rate. Additionally, to analyze the charge-discharge mechanisms of the electrodes, CV analysis was conducted to compare the electrochemical behavior of Al foil, C-QWF-600, and C-QWF-700, as shown in Supplementary Figure 8. It shows that two distinct redox couples are observed within a specific voltage range for all three electrodes. The oxidation/reduction peaks for Al foil, C-QWF-600, and C-QWF-700 were observed at approximately 3.76V/3.66V, 3.74V/3.70V, and 3.76V/3.68V, respectively, corresponding to the Ni2+/Ni4+ redox process. Additionally, oxidation/reduction peaks were observed at approximately 4.23V/4.13V, 4.22V/4.14V, and 4.24V/4.10V, respectively, which are attributed to the Co3+/Co4+ redox process. The Al foil and QWF electrode supports exhibited superior discharge capacity up to 200 mAh g-1, and the C-QWF-700 electrode support retained 89.8% of the initial discharge capacity after 50 cycles. The charge and discharge tests at 0.5 and 2 C-rates illustrated in Figure 5B and C show that, in the initial cycle, C-QWF-700 shows discharge capacities of 194.6 and 175.8 mAh g-1 at 0.5 and 2 C, respectively. This is higher than those of the cell with Al foil electrode support, which exhibit discharge capacities of 183.4 and 159.3 mAh g-1 in the initial cycle, respectively. After 500 cycles, C-QWF-700 exhibits a discharge capacity similar to that of a cell with an Al foil collector. Moreover, the C-QWF-700 electrode support showed capacity retention rates of 51.0% and 65.3% of the initial discharge at 0.5 and 2 C-rates, respectively, in a 500-cycle life test, indicating stable performance in continuous cycling. In general, carbon-based electrode collectors have lower conductivity than Al foil and show a rapid decrease in high-rate performance. However, the high CNT content and stable cathode material composite of the C-QWF-700 electrode support resulted in stable electrochemical performance in high-charge-and-discharge tests. The electrochemical reaction zones of the QWF electrode supports are shown in Figure 5D-F, which show the formation of a stable solid electrolyte interphase layer on the cathode surface during the initial cycle. Furthermore, the discharge curves for the second, fifth, and tenth consecutive cycles overlap, indicating reversible charge and discharge processes throughout the cycling. As shown in Figure 5E and F, at 0.5 C, the initial discharge capacities of the Al foil and QWF electrode supports (C-QWF-600 and C-QWF-700) are 178.8, 179.3, and 194.6 mAh g-1, respectively. After 10 cycles, these values decreased to 176.1, 176.9, and 191.8 mAh g-1, respectively. The capacity retention rates of the Al foil and QWF electrode support were similar; however, C-QWF-700 exhibited the highest discharge capacity. Supplementary Table 1 compares the competitive electrochemical performance of CNT-coated QWF-based electrodes with previously reported Ni, Co and Mn-based (NCM-based) cathodes using non-metallic or composite current collectors. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, the C-QWF-700 electrode exhibited superior rate performance and cycle stability compared to similar systems. Notably, it maintained a high capacity of 175.9 mAh g-1 at 2 C and achieved a capacity retention rate of 82.6% after 100 cycles, superior to many reported NCM811-based electrodes using carbon fibers,

Figure 5. Cycle performance of QWF electrodes at (A) 0.1 C-rate (1 C = 275 mAh g-1), (B) 0.5 C-rate, and (C) 2 C-rate; Galvanostatic discharge/charge voltage profiles of 3.0 and 4.3 V at 0.5 C-rate for (D) Aluminum foil electrode support, (E) C-QWF-600 electrode support, and (F) C-QWF-700 electrode support. QWF: Quartz woven fabric; C-QWF: CNT-coated QWF; CNT: carbon nanotube.

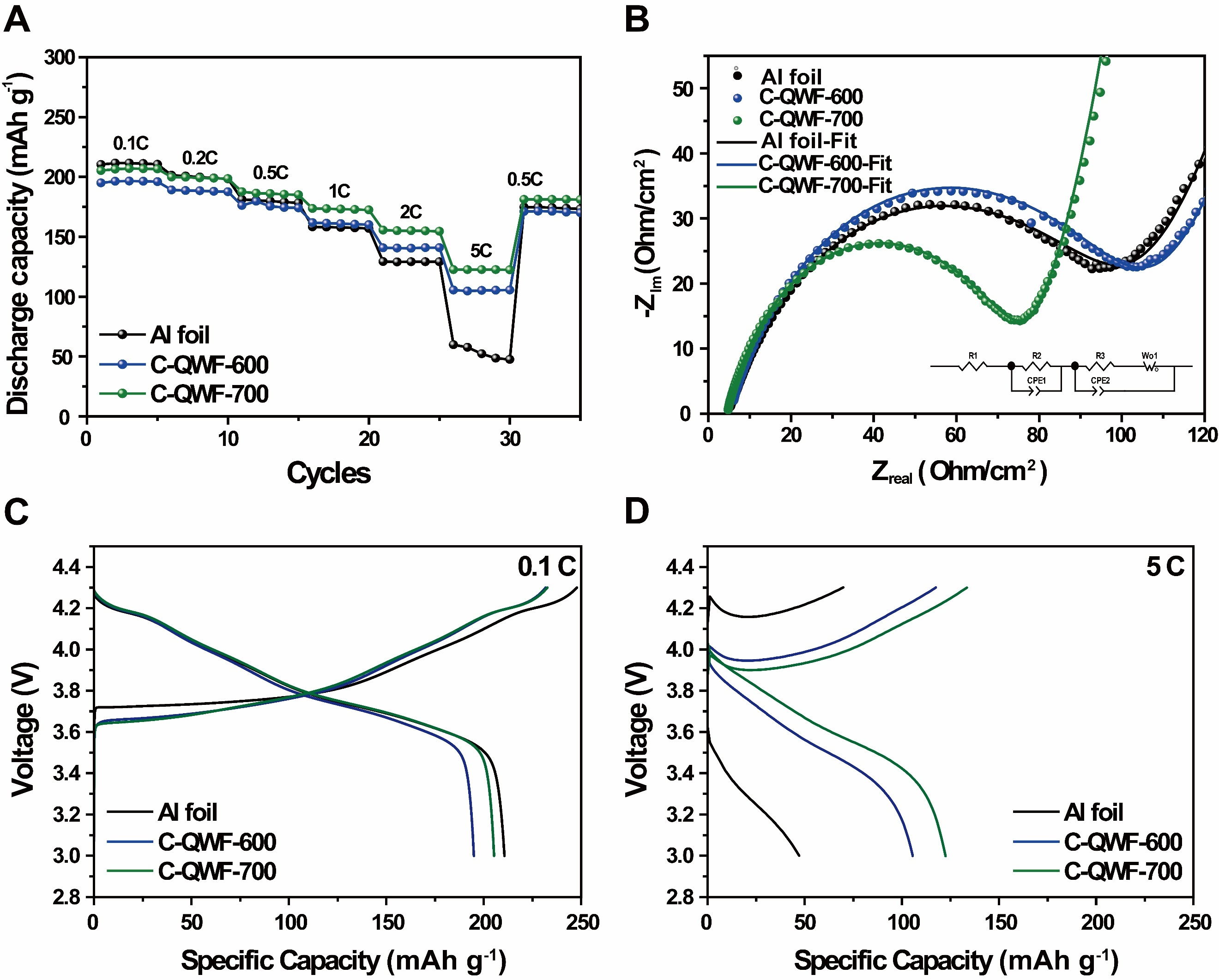

Figure 6A shows the charge/discharge rate performance of the QWF electrode supports with increasing charge/discharge rates of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 C. The rate performance of the QWF electrode supports (C-QWF-600 and C-QWF-700) was also evaluated. The discharge capacities of C-QWF-700 at the aforementioned charge/discharge rates are 205.3, 199.9, 187.6, 173.6, 155.5, and 122.4 mAh g-1, respectively; moreover, C-QWF-700 exhibits higher discharge capacity and rate capability at 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 C. Additionally, Supplementary Figure 9 presents the cycling performance of cells at 5 C, 10 C, and 20 C for Al foil, C-QWF-600, and C-QWF-700 electrodes. Supplementary Figure 9A illustrates the cyclability test conducted at a 5 C rate over 100 cycles, demonstrating stable cycling performance with discharge capacities of 84.91, 141.40, and 166.85 mAh g-1 for Al foil, C-QWF-600, and C-QWF-700, respectively. Furthermore, as shown in Supplementary Figure 9B and C, only C-QWF-700 sustained 100 cycles at 10 C and 200 cycles at 20 C. Based on the first cycle, the discharge capacities at 10 and 20 C were measured as 117.87 and

Figure 6. (A) Rate performance of Al foil and QWF electrode supports at 0.1 to 5 C-rate, (B) electrochemical impedance spectra for Al foil and QWF electrode supports. First cycle of galvanostatic discharge/charge voltage profile between 3.0 and 4.3 V at (C) 0.1 C-rate, (D) 5 C-rate. QWF: Quartz woven fabric.

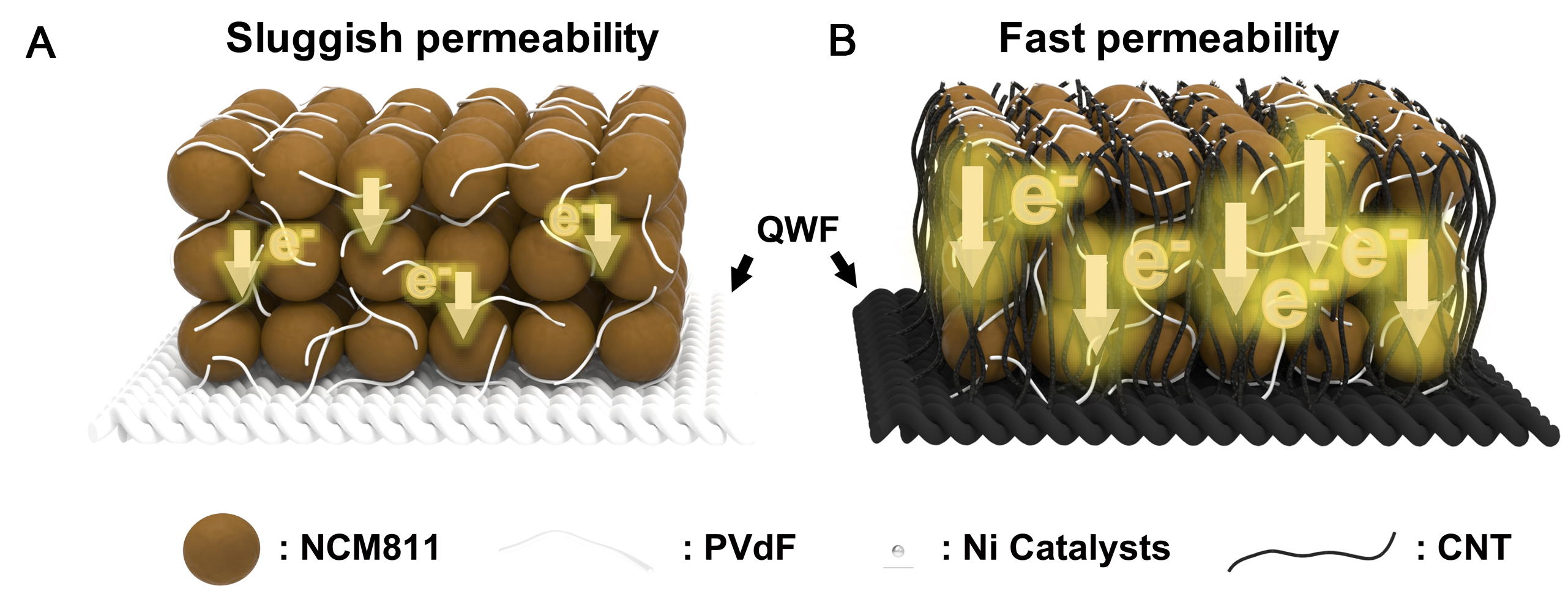

Considering the electrochemical performance, a reaction schematic of the superior electrochemical performance of the C-QWF-700 electrode support in comparison with that of the P-QWF electrode support is shown in Figure 7. The P-QWF is a silica substrate electrode that results in slow electron transfer owing to the low electrical conductivity of silicon [Figure 7A]. In contrast, C-QWF-700 is a silica substrate electrode with a carbon coating on the silica surface and simultaneous CNT growth, which forms a carbon network that facilitates electron transfer [Figure 7B]. This CNT network enables high electron transfer while efficiently fixing the electrode material, which is believed to be favorable for high-rate charging and discharging[32-35]. In conventional structural battery electrodes, CNTs, which exhibit high mechanical strength but can only play a relatively minor role as energy assistants, will expand the possibilities in terms of energy density through the application of multifunctional electrode supports for structural batteries.

CONCLUSION

In this study, to analyze the electrochemical performance of CNT growth for robust battery electrodes, optimized QWF electrode supports for LIBs were prepared by sequential sputtering and CVD processes, and C-QWF electrode supports with uniform and abundant CNT growth on the QWF were successfully fabricated. Compared to C-QWF-600, the optimized C-QWF-700 showed a discharge capacity of

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the research and supervised the work: Park, M. Y.; Kim, J. H.

Wrote the manuscript: Hwang, H.

Homogenized the final version and played a major role in the corrections: Choi, H. J.; Baek, D.; Lee, D.; Kwon, D. J.; Jeong, S. H.

All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Some results of supporting the study are presented in the Supplementary Materials. Other raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Glocal University 30 Project Fund of Gyeongsang National University in 2024. This work was supported by the Glocal University 30 Project Fund of Gyeongsang National University in 2025.

Conflicts of interest

We confirm that the author “Park, M. Y.” is affiliated with SASUNG Power Co. and that her contribution to this work does not involve any conflicts of interest. We have verified that her participation complies with the company’s internal policies and does not present any issues regarding affiliation or potential conflict. While other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Zeng, X.; Li, M.; Abd El-hady, D.; et al. Commercialization of lithium battery technologies for electric vehicles. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2019, 9, 1900161.

2. Larcher, D.; Tarascon, J. M. Towards greener and more sustainable batteries for electrical energy storage. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 19-29.

3. Li, M.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z.; Amine, K. 30 years of lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1800561.

4. Galos, J.; Pattarakunnan, K.; Best, A. S.; Kyratzis, I. L.; Wang, C.; Mouritz, A. P. Energy storage structural composites with integrated lithium-ion batteries: a review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2001059.

5. Saeed, G.; Kang, T.; Byun, J. S.; et al. Two-dimensional (2D) materials for 3D printed micro-supercapacitors and micro-batteries. Energy. Mater. 2024, 4, 400017.

6. Li, W.; Liu, X.; Xie, Q.; You, Y.; Chi, M.; Manthiram, A. Long-term cyclability of NCM-811 at high voltages in lithium-ion batteries: an in-depth diagnostic study. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 7796-804.

7. Andre, D.; Kim, S.; Lamp, P.; et al. Future generations of cathode materials: an automotive industry perspective. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 6709-32.

8. Xu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. FeP@C nanotube arrays grown on carbon fabric as a low potential and freestanding anode for high-performance Li-ion batteries. Small 2018, 14, 1800793.

9. Liu, S.; Xiong, L.; He, C. Long cycle life lithium ion battery with lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide (NCM) cathode. J. Power. Sources. 2014, 261, 285-91.

10. Asp, L. E.; Johansson, M.; Lindbergh, G.; Xu, J.; Zenkert, D. Structural battery composites: a review. Funct. Compos. Struct. 2019, 1, 042001.

11. Park, M. Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, D. K.; Kim, C. G. Perspective on carbon fiber woven fabric electrodes for structural batteries. Fibers. Polym. 2018, 19, 599-606.

12. Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; et al. Two-step carbon coating onto nickel-rich LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 cathode reduces adverse phase transition and enhances electrochemical performance. Electrochim. Acta. 2023, 454, 142339.

13. She, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hong, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Y. Surface coating of NCM-811 cathode materials with g-C3N4 for enhanced electrochemical performance. ACS. Omega. 2022, 7, 24851-7.

14. Goh, M. S.; Moon, H.; Shin, H.; et al. Unlocking high-efficiency lithium-ion batteries: sucrose-derived carbon coating on nickel-rich single crystal Li[Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1]O2 cathodes. Surf. Interfaces. 2024, 51, 104721.

15. Zhuang, Y.; Shen, W.; Yan, J.; et al. Regulating the heat generation power of a LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 cathode by coating with reduced graphene oxide. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2022, 5, 4622-30.

16. Gakis, G. P.; Termine, S.; Trompeta, A. A.; Aviziotis, I. G.; Charitidis, C. A. Unraveling the mechanisms of carbon nanotube growth by chemical vapor deposition. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 445, 136807.

17. Welna, D. T.; Qu, L.; Taylor, B. E.; Dai, L.; Durstock, M. F. Vertically aligned carbon nanotube electrodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2011, 196, 1455-60.

18. Bitew, Z.; Tesemma, M.; Beyene, Y.; Amare, M. Nano-structured silicon and silicon based composites as anode materials for lithium ion batteries: recent progress and perspectives. Sustain. Energy. Fuels. 2022, 6, 1014-50.

19. Chen, J.; Minett, A.; Liu, Y.; et al. Direct growth of flexible carbon nanotube electrodes. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 566-70.

20. Liu, X.; Huang, Z. D.; Oh, S. W.; et al. Carbon nanotube (CNT)-based composites as electrode material for rechargeable Li-ion batteries: a review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2012, 72, 121-44.

21. Wang, X.; Waje, M.; Yan, Y. CNT-based electrodes with high efficiency for PEMFCs. Electrochem. Solid-State. Lett. 2005, 8, A42.

22. Hwang, T. H.; Lee, Y. M.; Kong, B. S.; Seo, J. S.; Choi, J. W. Electrospun core-shell fibers for robust silicon nanoparticle-based lithium ion battery anodes. Nano. Lett. 2012, 12, 802-7.

23. Peng, H.; Jain, M.; Peterson, D. E.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, Q. Composite carbon nanotube/silica fibers with improved mechanical strengths and electrical conductivities. Small 2008, 4, 1964-7.

24. Landi, B. J.; Ganter, M. J.; Cress, C. D.; Dileo, R. A.; Raffaelle, R. P. Carbon nanotubes for lithium ion batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 638-54.

25. Varzi, A.; Täubert, C.; Wohlfahrt-mehrens, M.; Kreis, M.; Schütz, W. Study of multi-walled carbon nanotubes for lithium-ion battery electrodes. J. Power. Sources. 2011, 196, 3303-9.

26. Pampal, E. S.; Stojanovska, E.; Simon, B.; Kilic, A. A review of nanofibrous structures in lithium ion batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2015, 300, 199-215.

27. Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, K.; Fan, S. Applications of carbon nanotubes in high performance lithium ion batteries. Front. Phys. 2014, 9, 351-69.

28. Qian, W.; Tian, T.; Guo, C.; et al. Enhanced activation and decomposition of CH4 by the addition of C2H4 or C2H2 for hydrogen and carbon nanotube production. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008, 112, 7588-93.

29. Wei, T.; Bao, L.; Hauke, F.; Hirsch, A. Recent advances in graphene patterning. Chempluschem 2020, 85, 1655-68.

30. Shabaker, J.; Simonetti, D.; Cortright, R.; Dumesic, J. Sn-modified Ni catalysts for aqueous-phase reforming: characterization and deactivation studies. J. Catal. 2005, 231, 67-76.

31. Ma, Z.; Jia, R.; Liu, C. Production of hydrogen peroxide from carbon monoxide, water and oxygen over alumina-supported Ni catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A. Chem. 2004, 210, 157-63.

32. Wang, G.; Ahn, J.; Yao, J.; Lindsay, M.; Liu, H.; Dou, S. Preparation and characterization of carbon nanotubes for energy storage. J. Power. Sources. 2003, 119-121, 16-23.

33. Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Chang, H.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of short carbon nanotubes and application as an electrode material in Li-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 3613-8.

34. Yang, S.; Huo, J.; Song, H.; Chen, X. A comparative study of electrochemical properties of two kinds of carbon nanotubes as anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 2008, 53, 2238-44.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].