Effects of photoaging on biofilm development and microbial community in polypropylene and polylactic acid microplastics in freshwater

Abstract

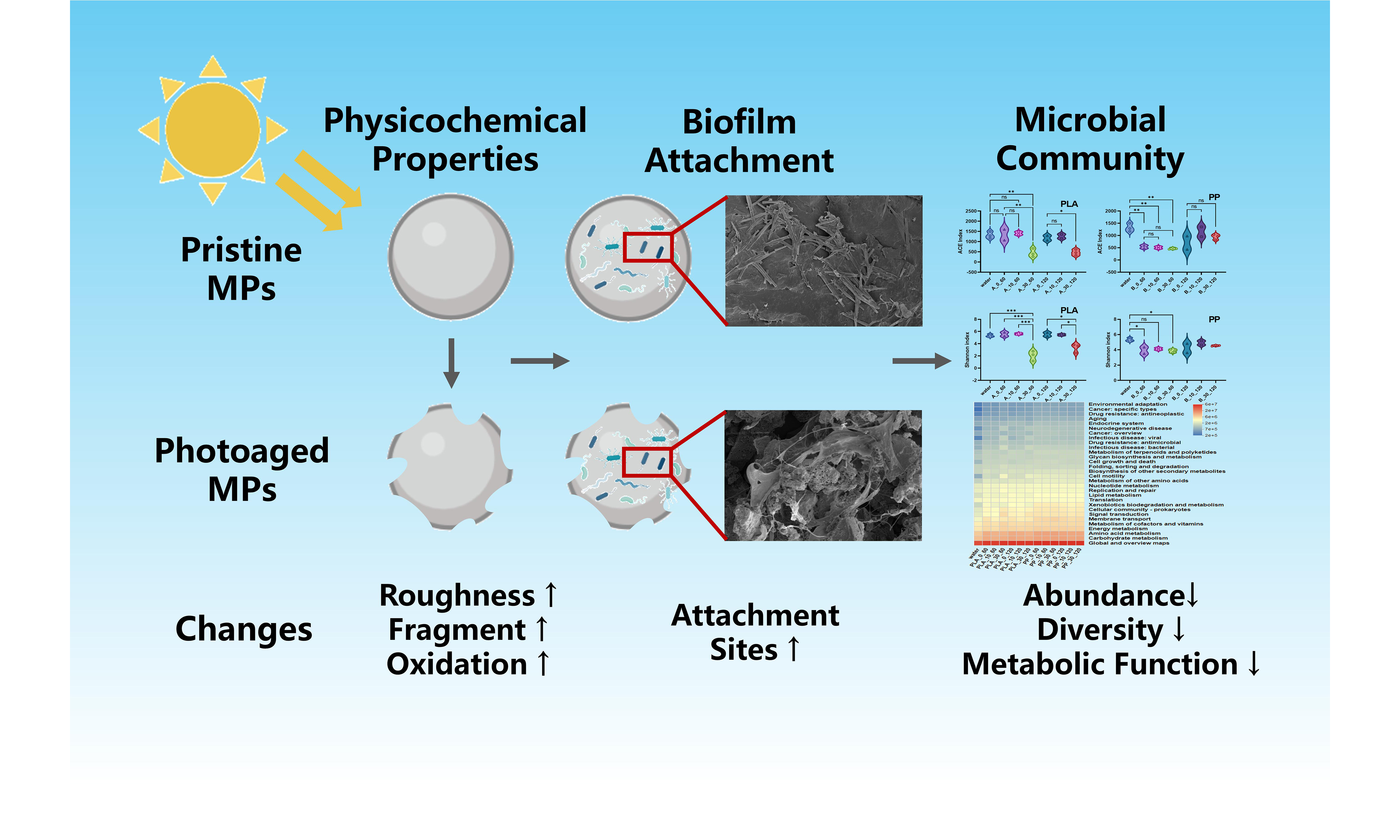

Microplastics (MPs) in surface waters undergo both photoaging and biofilm colonization, yet their interactive effects remain poorly understood. This study systematically examined the effects of varying degrees of photoaging on the physicochemical properties, biofilm formation, and bacterial community structure and function of polypropylene (PP) and polylactic acid (PLA) MPs. Results showed that prolonged photoaging caused extensive fragmentation and oxidation in PLA, leading to substantially increased organic leaching, whereas PP primarily exhibited increased surface roughness and specific surface area. Microcosm biofilm incubation results indicated that photoaging reduced the biofilm formation in PLA. Also, bacterial abundance and diversity in biofilms decreased in highly photoaged PLA relative to pristine ones, suggesting that excessive photodegradation exerted inhibitory effects on microbial colonization in PLA MPs. In contrast, photoaging displayed few effects on biofilm formation on PP, where bacterial community structures gradually reorganized and stabilized during incubation. Microbial functional prediction results indicated that microbial metabolic activity in PLA decreased with increasing photoaging degrees, while PP showed minor changes in metabolic functions. This study revealed the distinct regulatory mechanisms of photoaging on the ecological behavior of different MP types, providing a deep understanding of their environmental fate and behavior in natural water.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several decades, global plastic production has increased dramatically, and the widespread use of plastics has led to their accumulation in the environment. It is estimated that the total amount of global plastic waste will reach 12 billion tons by 2050[1], with more than 55% eventually entering aqueous environments[2]. Conventional plastics [polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), etc.] are persistent in the environment and raise several pollutions[3-5]. To address this global crisis, biodegradable plastics have been increasingly promoted as eco-friendly alternatives[6]. Their global production capacity is projected to increase from 2.2 million tons in 2022 to 6.3 million tons by 2027, among which polylactic acid (PLA) accounts for approximately 20%[7]. Although PLA can undergo slow hydrolytic degradation in the environment[8], it normally achieves a high degree of degradation under industrial composting conditions (high-temperature and high-humidity environments)[9]. This can result in the long-term accumulation of PLA in the environment[10].

Once plastics enter the natural environment, they undergo a series of aging processes that gradually fragment them into smaller particles, among which microplastics (MPs) with diameters less than 5 mm are the most abundant[11]. MPs are also subject to biotic and abiotic processes[12]. In aquatic environments, MPs are rapidly colonized by microorganisms, leading to the formation of biofilms[13]. Biofilms typically comprise microorganisms (including bacteria, fungi, and algae) and their secreted extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)[14]. The formation of biofilms transforms the MP surface into a complex, bioactive platform[15]. The attached microorganisms can cleave the high-molecular-weight polymers into oligomers, dimers, or monomers. Subsequently, these low-molecular-weight products are taken up by microorganisms and used as carbon sources in cellular metabolism[16]. The formation of biofilms not only alters the physicochemical properties of MPs but also establishes a distinct microecosystem from the surrounding water, which influences the environmental fate, migration capacity, and ecological effects of MPs[17].

In addition to biofilm formation, sunlight irradiation can occur on MPs to induce photoaging. In the presence of oxygen, ultraviolet (UV) energy can abstract hydrogen atoms from side chains or terminal groups in a polymer, initiating oxidation reactions that generate oxygen-containing functional groups such as carbonyl (C=O) and hydroxyl (-OH)[18]. Under prolonged exposure, MPs undergo a series of physicochemical property changes, such as color darkening (yellowing, blackening), surface cracking, and even fragmentation[19,20]. Also, photoaging induces rearrangements in crystalline and chemical structures[21]. These surface modifications may affect the microbial colonization and biofilm formation in MPs, considering that the biofilm formation is dependent on the physicochemical properties of MPs[22]. However, the correlation between the physicochemical properties of MPs mediated by photoaging and biofilm formation remains unclear currently.

As for the knowledge gap, this study investigated the effects of varying degrees of photoaging on the physicochemical properties of MPs and on their biofilm formation and microbial community succession, using conventional PP and biodegradable PLA as representative MPs. Specifically, the purpose of this study is to: (1) investigate differences about the effects of photoaging on the physical and chemical properties of MPs; (2) clarify the regulatory role of these property changes in biofilm formation, bacterial community composition and function; (3) evaluate the colonization characteristics and functional responses of bacterial communities on the surface of different photoaged MPs. This study will elucidate the dynamic process from photoaging to biofilm establishment of MPs in natural water, providing evidence for understanding their environmental fate and biological transformation.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

PP and PLA (particle size: approximately 0.34 mm) were purchased from Fengtai Polymer Materials Co., Ltd. (Dongguan, China). Before testing, the MPs were washed three times with ethanol and deionized water to remove surface impurities, dried at 45 °C and stored in dark-sealed glass containers to prevent exposure to external light and humidity.

Surface water samples were collected in October 2022 from urban water bodies in Xianyang, China (100° 6′ E, 58° 14′ N). Micro-Raman analysis indicated that the background concentration of MPs in the water samples was 275 particles/L, which was lower than the added concentration of 1.25 g/L (92,000 particles/L) in the microcosm incubation experiment, suggesting minimal interference from background MPs. The water quality parameters of surface water samples were measured as follows: pH 8.74, dissolved oxygen (DO) 10.59 mg/L, total organic carbon (TOC) 46.13 mg/L, total nitrogen (TN) 3.03 mg/L, and total phosphorus (TP) 0.08 mg/L. After filtering through a 2 mm stainless steel sieve to remove impurities, the collected water samples were promptly used for experiments.

Preparation of MPs with different photoaging degrees

Two types of MPs were spread out on tin foil trays and subjected to photoaging in a UV chamber equipped with three 40 W UV lamps (light intensity: 20.53 ± 2.61 W/m2) at 30 °C. The MPs were stirred once daily to ensure all particles received adequate irradiation. The samples were irradiated for 0, 10, 20, and 30 days, respectively[23]. The MPs with different photoaging times were collected and stored in dark-sealed glass containers.

Microcosm incubation experiment

The microcosm incubation experiment was conducted in 25 L containers at approximately 30 °C for 120 days. A total of 12.50 g of MPs with different photoaging degrees were added to 10 L of surface water to achieve a concentration of 1.25 g/L[24,25], with three replicates for each treatment. Water samples and MPs were collected on days 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 for subsequent analysis. All collected MPs were rinsed with phosphate buffer solution, freeze-dried, then sealed and stored at -20 °C.

Characterization of MPs

The dispersion of MPs with different photoaging times in water was compared visually and documented photographically. Specifically, MPs were added to deionized water (1.25 g/L), thoroughly mixed and then photographed. Morphological alterations of MPs were characterized using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Nano SEM 450, FEI, USA), operating at an accelerating voltage of 5.00 kV. Before analysis, the samples were dispersed through an electroconductive paste using a tweezer coated with platinum. Particle size was analyzed on the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images using Nano Measurer software (version 1.2, Fudan University). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Vertex70, Bruker, Germany) was used to determine the chemical composition of MPs. Spectra were collected over a wavenumber range of 400-4,000 cm-1. Each sample was scanned 16 times, and the spectra were subjected to atmospheric correction. To quantify the oxidation degree, the carbonyl index (CI) was calculated based on the maximum intensity of the C=O peak (I1714 for PP, I1760 for PLA) relative to the methylene peak (I977 for PP, I1452 for PLA) in the FTIR spectra[26,27]. The specific surface area of the MPs was characterized using a fully automated physical adsorption analyzer [Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET), ASAP 2460, Micromeritics, USA].

Analysis of leachate samples

The concentration of TOC leached from MPs with different degrees of photoaging was measured using a TOC analyzer (TOC-L, Shimadzu, Japan). The excitation-emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectra were measured by a fluorescence spectrophotometer (RF-6000, Shimadzu, Japan). The scanning program was as follows: Excitation wavelength was increased from 250 to 600 nm in 5 nm increments, and the emission wavelength was increased from 200 to 600 nm in 5 nm increments. Ultrapure water was used as a blank to eliminate the effects of Raman scattering.

Characterization of biofilms

Microbial colonization on MP surfaces was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Nano SEM 450, FEI, USA). The distribution of live and dead bacteria on MPs was examined by a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, FV3000, Olympus, Japan). Specifically, MPs with attached biofilms were stained with 3.34 μmol/L SYTO® 9 green fluorescent nucleic acid stain and 20 μmol/L propidium iodide (PI) for 30 min. After rinsing off residual stain, the MPs were placed on slides for imaging. Live and dead cells were stained green and red, with excitation wavelengths of 488 and 561 nm, respectively.

The crystal violet (CV) staining method is widely used for biofilm biomass quantification due to its operational simplicity[28]. Specifically, 10 mg of MPs were added to 0.5 mL of 0.1% CV staining solution and stained for 45 min. After rinsing with deionized water to remove excess stain and air-drying at room temperature, the MPs were transferred to centrifuge tubes containing 3.0 mL of 95% ethanol for decolorization for 10 min. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 595 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (GENESYS 50, Thermo Scientific, USA).

For EPS content measurement, 100 mg of MPs were placed in 5 mL of ultrapure water and then centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 15 min. The resulting supernatant was collected for analysis. Using bovine serum albumin as a standard, protein content was determined by the modified Lowry method[29]. Specifically, 0.5 mL of

16S rRNA sequencing

To analyze the bacterial community in MPs biofilms, the V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene was amplified for high-throughput sequencing. Total genomic DNA was extracted from the samples using the TGuide S96 Magnetic Soil/Stool DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA integrity was verified by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, and concentration and purity were quantified with a UV-visible spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Scientific, USA). The V3-V4 region was amplified using universal primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Amplicon libraries were prepared using the Omega DNA Purification Kit (Omega Inc.) for paired-end sequencing (2 × 250 bp) and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Biomarker Technologies, China). Raw reads were processed using DADA2 to generate high-resolution amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), and low-abundance ASVs (≤ 2 reads across all samples) were filtered to minimize noise. Taxonomic classification was performed in QIIME2 using the SILVA 138.1 database with the Naive Bayes classifier at a 70% confidence threshold. Alpha diversity was calculated and visualized using QIIME2 and R software, respectively. Beta diversity was determined through QIIME software to assess the similarity of bacterial communities across different samples.

Data analysis

Data analysis and visualization were performed using Origin 2025b and GraphPad Prism 9.5.0. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 to assess the differences in bacterial communities of MP biofilms across different incubation periods. The symbols *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Physicochemical properties of MPs under different photoaging degrees

Changes in physical properties

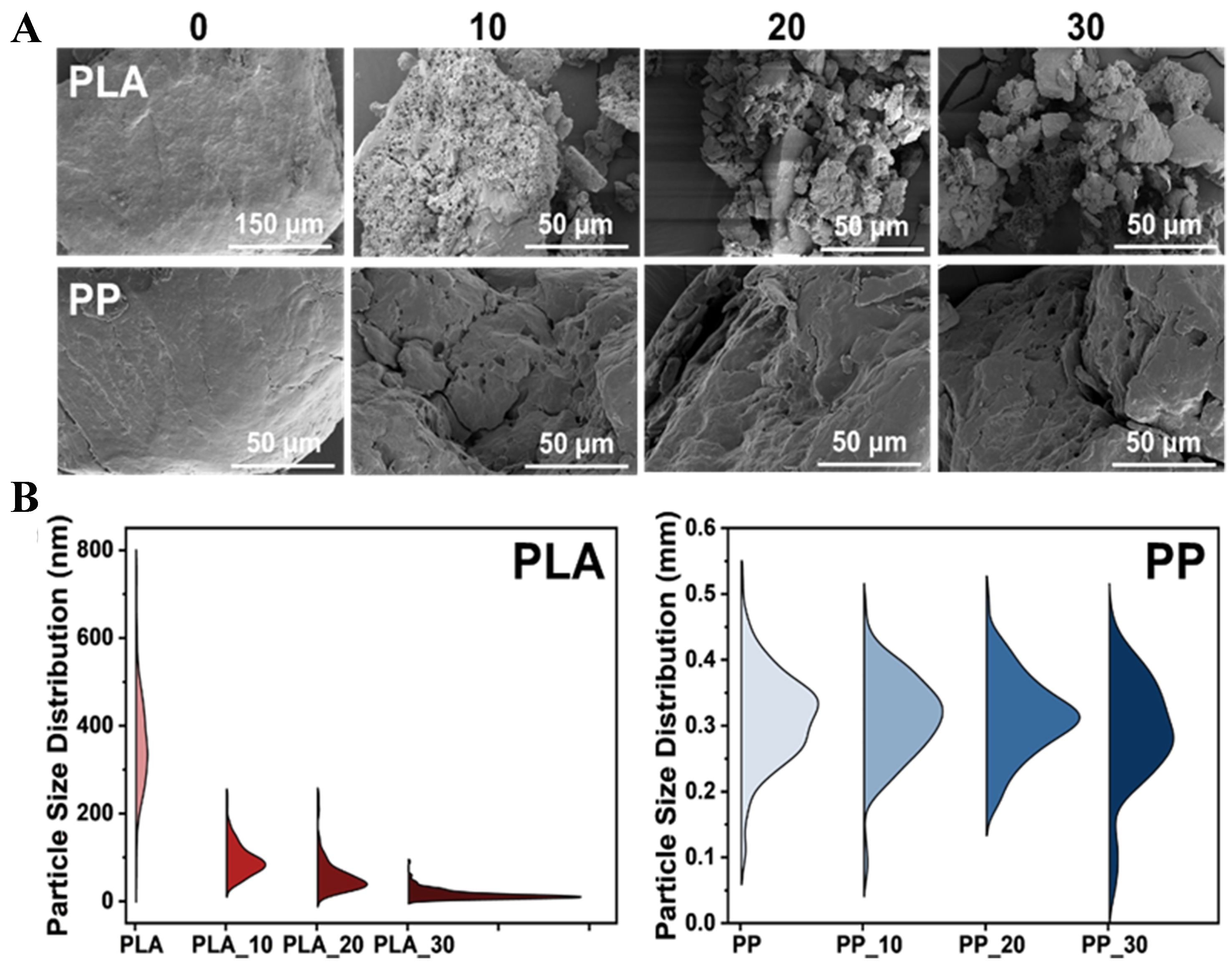

SEM images revealed that PLA exhibited severe fragmentation after different photoaging durations, with the degree of fragmentation increasing under prolonged exposure time. Similarly, PP exhibited increased surface roughness but maintained a relatively intact structure [Figure 1A]. The average particle size of pristine PLA was 0.36 mm. After 10 days of photoaging, PLA rapidly fragmented to 0.09 mm, further decreasing to 0.06 and 0.02 mm after 20 and 30 days, respectively. In contrast, PP exhibited minimal changes in particle size, with the average size decreasing slightly from 0.31 to 0.29 mm after 30 days of photoaging [Figure 1B and Table 1]. These results indicated that PLA underwent greater fragmentation under photoaging, while PP demonstrated high stability.

Figure 1. (A) Surface morphology and (B) particle size distribution of PLA and PP after 0, 10, 20 and 30 days of photoaging. PLA: Polylactic acid; PP: polypropylene.

The particle sizes of PLA and PP after 0, 10, 20 and 30 days of photoaging

| MPs | Average (mm) | Maximum (mm) | Minimum (mm) |

| PLA_0 | 0.36 | 0.76 | 0.05 |

| PLA_10 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.03 |

| PLA_20 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.01 |

| PLA_30 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| PP_0 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.01 |

| PP_10 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.08 |

| PP_20 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.18 |

| PP_30 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.04 |

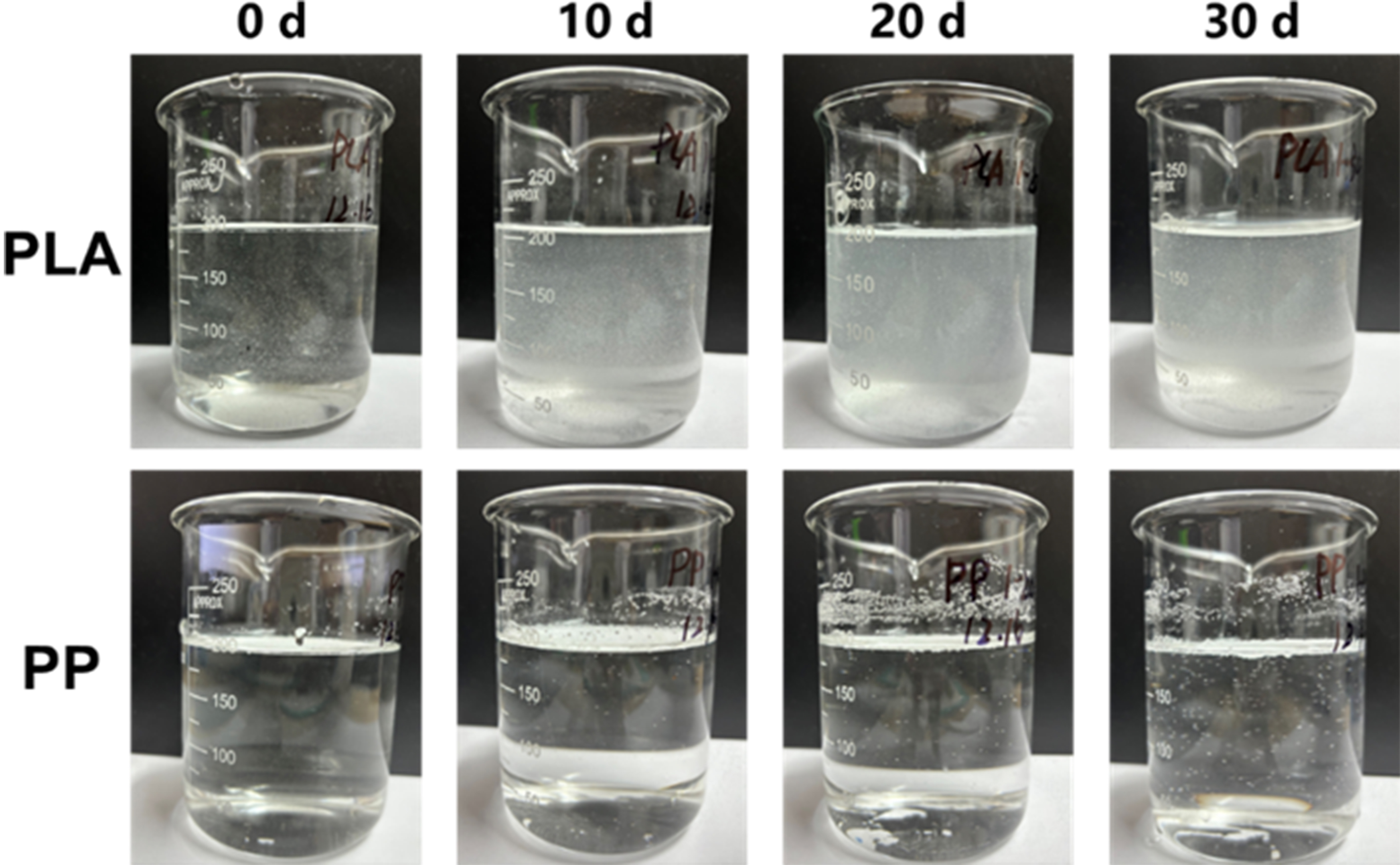

As the particle structure fragmented, the specific surface area of MPs also changed. As shown in Table 2, the specific surface area of PLA gradually decreased with prolonged photoaging duration. This may be attributed to the agglomeration tendency of small particles generated by fragmentation[31]. Under heavily photoaged conditions, this phenomenon became pronounced. This might be due to extremely low N2 adsorption signals and poor adsorption fitting quality, resulting from severe aggregation and collapse of the pore structures of PLA after intensive photoaging[32,33]. After 30 days of photoaging, PP exhibited a 2.83-fold increase in specific surface area relative to its original value, likely due to surface cracking and increased roughness. To investigate the dispersion properties of MPs with varying degrees of photoaging in water, MPs (1.25 g/L) were added to deionized water during microcosm incubation. As shown in Figure 2, photoaged PLA exhibited more uniform distribution in water with reduced sedimentation rates, closely related to its enhanced suspension properties after severe fragmentation[34]. For PP, the migration tendencies toward water were only observed in 30-day photoaged samples. Although photoaging at 10 and 20 days also promoted PP migration into water, their impacts on dispersion performance were not significant.

Figure 2. Dispersion degree of PLA and PP in water after 0, 10, 20 and 30 days of photoaging. PLA: Polylactic acid; PP: polypropylene.

The specific surface area of PLA and PP after 0, 10, 20 and 30 days of photoaging

| MPs | BET specific surface area (m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) | BJH adsorption average pore size (nm) | BJH desorption average pore size (nm) |

| PLA_0 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 13.50 | - |

| PLA_10 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 21.98 | 24.90 |

| PLA_20 | - | - | - | - |

| PLA_30 | - | - | - | - |

| PP_0 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 10.22 | 13.39 |

| PP_10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | - |

| PP_20 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 22.70 | 14.54 |

| PP_30 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 6.60 | 4.69 |

Changes in chemical properties

In addition to physical changes, photoaging also induced alterations in the chemical properties of PLA and PP. FTIR spectra revealed that as photoaging duration increased, the C=O and -OH absorption peaks in PLA became enhanced, indicating surface oxidation[35]. Although C=O absorption peaks also appeared in photoaged PP, the magnitude of change was lower than that in PLA [Figure 3A]. The degree of oxidation was quantified by calculating the CI values. As shown in Figure 3B, the CI values of photoaged PLA increased significantly to varying degrees. After 10, 20, and 30 days of photoaging, the CI values increased from the initial value of 1.63 to 2.36, 2.68, and 3.88, respectively. However, PP only showed a significant increase in CI values from 0.11 to 0.39 after 30 days of photoaging (P < 0.05). This demonstrated that PLA was more sensitive to UV-induced reactions and exhibited higher oxidation levels than PP.

Figure 3. (A) FTIR spectra, (B) CI values of PLA and PP after 0, 10, 20 and 30 days of photoaging; (C) The concentration of TOC leached from PLA and PP with different photoaging degrees; (D) EEM spectra of water samples collected at 30, 60, and 90 days of microcosm incubation experiments of PLA and PP with different photoaging degrees. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001. NS indicates no significant difference. FTIR: Fourier transform infrared; CI: carbonyl index; PLA: polylactic acid; PP: polypropylene; TOC: total organic carbon; EEM: excitation-emission matrix.

Organic matter leaching and fluorescence characteristics

Additionally, MPs with different degrees of photoaging were added to ultrapure water at a concentration of 1.25 g/L and incubated for three days to evaluate differences in organic matter release. As shown in Figure 3C, the TOC concentrations in PLA leachates under photoaging for 10, 20, and 30 days were 10.13, 13.21, and 17.53 times higher than that of pristine PLA, respectively, indicating an increase in organic matter release from PLA with prolonged photoaging duration[21]. Under identical conditions, PP also exhibited increasing TOC trends, reaching 1.02, 1.19, and 1.39 times higher than the original value.

EEM spectroscopy was applied to evaluate fluorescent organic matter released by MPs during incubation. As shown in Figure 3D, during the first 90 days of incubation, the concentration of fluorescent substances in the water samples of PLA treatments with different degrees of photoaging increased continuously and rapidly, and the longer the photoaging duration, the greater the amount of organic matter released. However, from 90 to 120 days, the fluorescent substance content gradually stabilized, suggesting that PLA leached a large amount of organic matter initially, followed by a saturated state. In contrast, the EEM spectra of PP samples across all treatments showed no obvious differences during the 120-day incubation period, indicating minimal variation in leaching behavior of PP with different photoaging degrees. Overall, PLA exhibited more pronounced changes than PP throughout the photoaging process, whether in physical fragmentation, chemical oxidation, or organic matter release.

Biofilm formation capacity among MPs with varying photoaging degrees

Microbial attachment

As shown in Figure 4A, SEM images revealed microbial attachment on PLA surfaces with varying photoaging degrees after 120 days of incubation. Although microbial colonization on PP surfaces proceeded at a slower rate, the presence of microorganisms and their EPS was observable across all treatments after 120 days of incubation. CLSM analysis on the staining of live and dead bacteria revealed that although severe fragmentation of PLA after photoaging provided more attachment sites for microorganisms, the total fluorescence signal intensity of attached cells decreased with prolonged photoaging duration [Figure 4B]. This indicated that higher photoaging was associated with a lower abundance of live and dead bacteria in PLA. This phenomenon may result from the release of large amounts of PLA degradation products, which exerted an inhibitory effect on microbial growth[36] [Figure 3C and D].

Biofilm biomass and EPS contents

Quantification of biofilm biomass revealed that for PLA, the photoaged treatments exhibited higher biofilm biomass than the pristine, where the 30-day photoaged treatment showed the highest level, which was inconsistent with the CLSM observations. The opposite result may result from fragmentation of PLA due to photoaging, which led to reduced particle size and enhanced adsorption capacity for CV dyes, EPS and polymer fragments[37], while CLSM reflected only the living or structurally intact biofilm. As for PP, no marked differences were observed among the different treatments [Figure 5A]. We further analyzed the protein and polysaccharide contents within the biofilms. As shown in Figure 5B and C, both protein and polysaccharide contents on the 30-day photoaged PLA surface were higher than in other treatments, similar to the biofilm biomass results. This phenomenon may result from fragmented PLA particles remaining in the suspension, further interfering with the determination of polysaccharide and protein contents. No obvious differences in polysaccharide and protein contents were observed among PP samples with varying photoaging degrees, indicating low effects of photoaging on microbial colonization and biofilm formation.

Bacterial community in MPs with varying photoaging degrees

Bacterial abundance and diversity

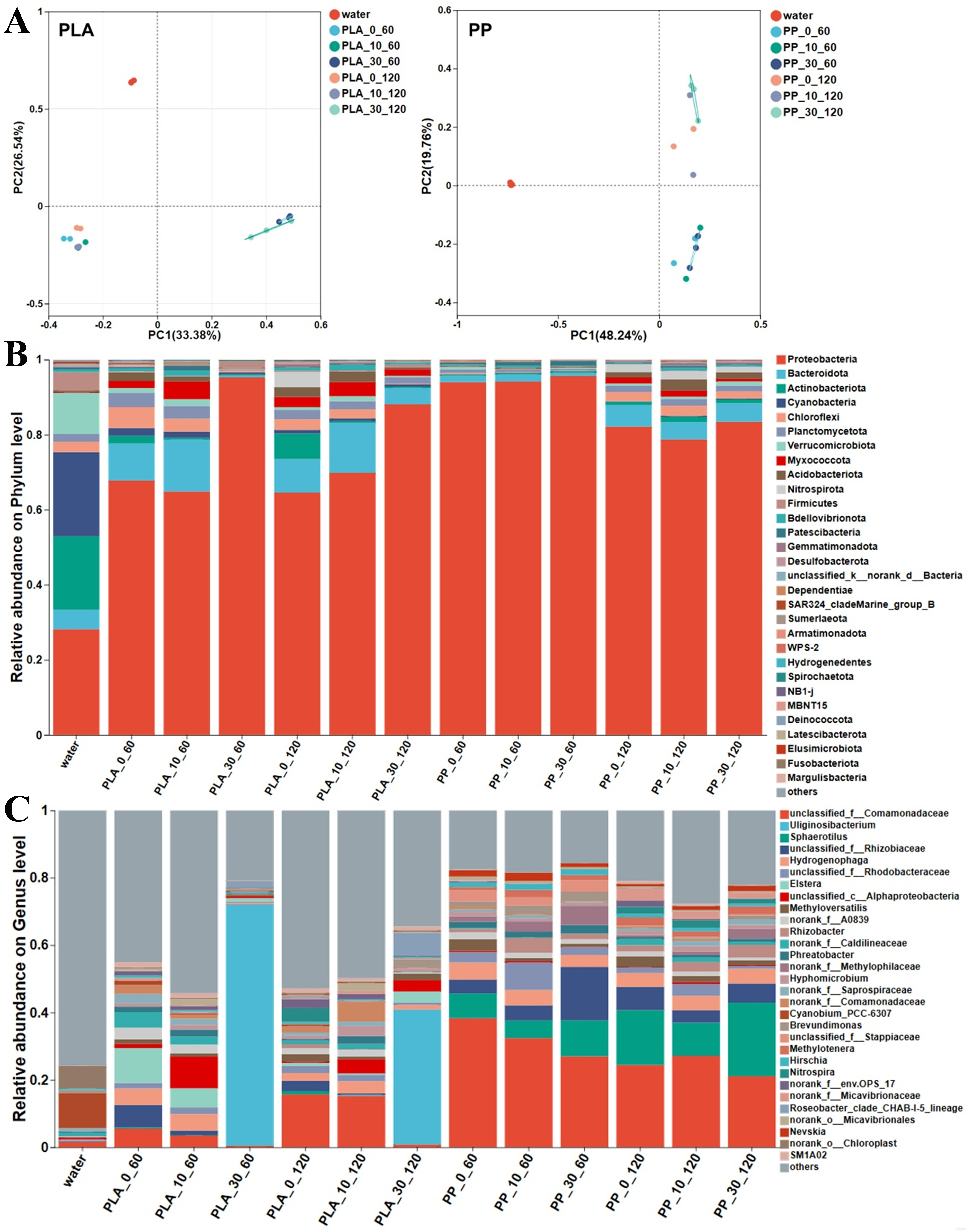

We systematically analyzed the evolution characteristics of bacterial communities in biofilms of PLA and PP with varying degrees of photoaging through α-diversity [Abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE) and Shannon indices], principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA), phylum- and genus-level bacterial community and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) functional prediction. α-diversity results indicated differences in bacterial abundance and diversity across biofilms on MP surfaces with varying degrees of photoaging. Specifically, the ACE index of PLA showed no significant difference between 0- and 10-day photoaged treatments after 60 and 120 days of microcosm incubation, indicating that moderate photoaging did not significantly affect the bacterial abundance on the MP surface. However, the ACE index of 30-day photoaged PLA was significantly lower than other treatments (P < 0.01), suggesting that excessive photoaging may inhibit microbial colonization during the incubation. There was no significant difference in bacterial abundance among PP samples with different degrees of photoaging, but all were lower than in the water samples. However, the bacterial abundance recovered in all treatments after 120 days of incubation. This suggested that microbial colonization on PP surfaces was strongly influenced by environmental selection. In contrast, microorganisms gradually established a micro-ecology suitable for growth in MPs as the incubation time increased [Figure 6A]. As for the Shannon index, both 0- and 10-day photoaged PLA exhibited no significant difference in bacterial diversity compared to water samples after 120 days of incubation, but were significantly higher than the 30-day photoaged treatment [Figure 6B]. This indicated that highly photoaged PLA exhibited greater screening capacity for the bacterial community, resulting in a more uniform community. As for PP, both 0- and 30-day photoaged treatments exhibited significantly lower diversity than the water samples after 60 days of incubation. This suggested that selective processes led to a community structure predominated by only a few taxa[38]. As recalcitrant polymers, MPs are poorly bioavailable to most heterotrophic microorganisms[39]. During biofilm development, taxa that cannot efficiently exploit plastic-derived carbon are gradually filtered out, whereas plastic-degrading bacteria become selectively enriched[40,41]. This environmental filtering leads to biofilm communities dominated by a few taxa, characterized by reduced richness and diversity. Meanwhile, photoaging promoted the leaching of additives and low-molecular-weight organics from MPs [Figure 3C and D], some of which exerted chemical stress on sensitive microorganisms, thereby strengthening the selection pressure[42]. Also, highly photoaging developed marked changes in MP surface properties [Figure 1A, Figure 3A and B], which may enhance interactions with bacterial cell membranes, cause membrane structural disruption[43], and trigger excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in bacterial cells, leading to oxidative stress responses such as lipid peroxidation and reduced ATPase activity[44].

Figure 6. (A) ACE and (B) Shannon index of biofilms on the photoaged PLA and PP MPs under microcosm incubation in surface water. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. NS indicates no significant difference. ACE: Abundance-based eoverage estimator; PLA: polylactic acid; PP: polypropylene; MPs: microplastics.

Bacterial community structure

PCoA analysis revealed that bacterial communities on PLA and PP surfaces with different photoaging degrees exhibited differences from those in water [Figure 7A], indicating that the surface microenvironment in MPs influenced microbial colonization and community assembly. For PLA, differences in community structure were observed between 30-day photoaged treatment and both 0- and 10-day photoaged treatments, indicating that the surface environment of highly photoaged PLA underwent drastic changes that drove bacterial community restructuration. In contrast, PP samples across different photoaging treatments showed no marked difference through incubation periods. However, after 120 days of incubation, the community structure of PP exhibited marked changes compared to 60 days of incubation, reflecting dynamic succession of bacterial communities under prolonged incubation. Phylum-level analysis revealed that, compared to the relatively low abundance of Proteobacteria in water (28.16%), the abundance in the biofilms on PLA and PP with different photoaging degrees increased, reaching 64.56%-95.25% and 78.71%-95.63%, respectively. Additionally, the abundance of Bacteroidetes increased from 5.19% in water to 9.84% in 0-day photoaged PLA treatment and 13.84% in 10-day photoaged treatment after 60 days of incubation. However, the Bacteroidetes first decreased to 0.47% in 30-day photoaged treatment and then increased to 4.37% at 120 days. This suggested that MPs with higher photoaging levels may initially inhibit certain microbial communities, followed by adaptive adjustments to adverse environmental conditions. For PP, similar changes were observed across different photoaging treatments. After 60 days of incubation, the abundances of the top seven bacterial phyla in water decreased, but rebounded after 120 days of incubation [Figure 7B]. Analysis at the genus level revealed the increased abundances of Hydrogenophaga and Elstera in 0- and 10-day photoaged PLA treatments. Notably, in 30-day photoaged PLA treatment, Uliginosibacterium constituted 71.61% of total bacteria after 60 days of incubation, but declined to 40.05% after 120 days. Uliginosibacterium is a pioneer bacterium that plays a role in early biofilm formation and organic matter degradation. As the cultivation period extended, their positions were gradually replaced by other functional bacteria, such as Elstera and Hydrogenophaga, which have been reported to possess the capability to degrade organic matter[45]. Regarding PP treatments, the abundances of Sphaerotilus, norank_f_Caldilineaceae, norank_f_Saprospiraceae, and Nitrospira gradually increased with extended incubation time [Figure 7C]. These taxa are typically linked to mature biofilm and specific function. Sphaerotilus is often associated with biofouling and mature attached communities. Others such as norank_f_Caldilineaceae and norank_f_Saprospiraceae are both later-stage community members associated with weathering[46,47]. Notably, Nitrospira, as the dominant ammonium-oxidizing bacterium, indicates a mature, multi-trophic microbial ecosystem ready to advance degradation, which holds positive implications for nitrogen cycling and bacterial metabolic functions[48,49].

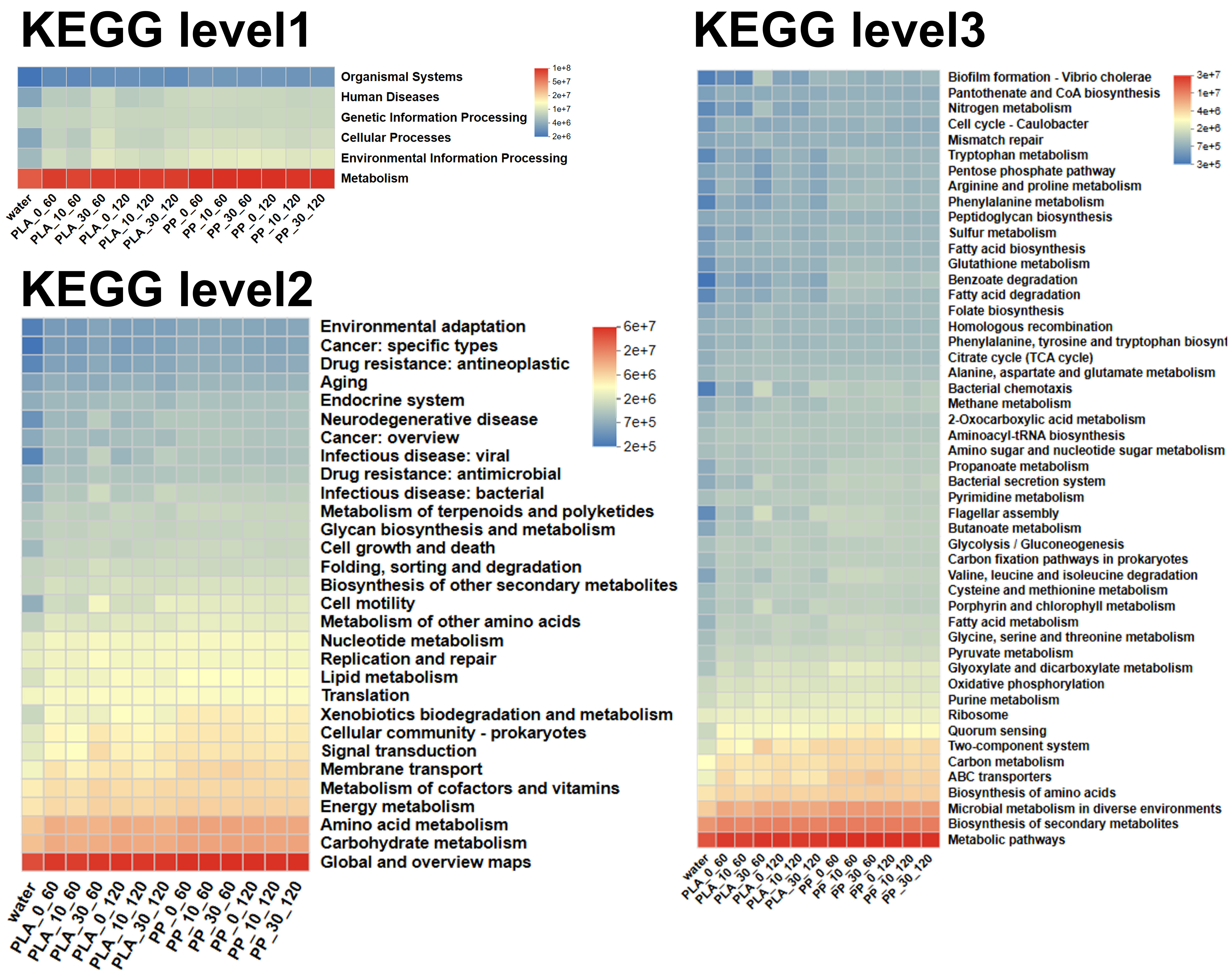

Bacterial community functions

KEGG functional prediction further reflected changes in bacterial community functions. As shown in Figure 8, KEGG Level 1 analysis indicated that metabolic functions in PLA and PP biofilms were higher than in water. Level 2 analysis revealed that amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, and heterotrophic biodegradation and metabolism functions were less abundant in the PLA treatments after 10 and 30 days of photoaging compared to pristine PLA. Moreover, the abundance of these functions decreased with longer photoaging duration. This may result from photoaging-inducing organic substances released from PLA [Figure 3C and D], which exerted toxicity on bacteria, thereby inhibiting their activity in nutrient conversion and degradation. Although PP treatments with different photoaging degrees exhibited similar trends, the changes were not obvious, indicating relatively stable metabolic functions in PP biofilms. Further analysis at Level 3 revealed that the two-component regulatory system was higher in the 30-day photoaged PLA treatment compared to 0- and 10-day photoaged treatments. This indicated that highly photoaged PLA provided a more challenging survival environment for microorganisms, necessitating enhanced signal transduction mechanisms to cope with external stress[50]. Concurrently, the functions related to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport and quorum sensing progressively weakened in PLA biofilms with increasing photoaging degrees, potentially indicating suppression or functional adaptation in nutrient uptake and intercellular communication[51]. For PP samples, although different photoaging treatments did not markedly affect bacterial functions, ABC transport and quorum sensing functions showed a gradual decline trend with extended incubation time. Overall, these results indicated that varying degrees of photoaging influenced bacterial community composition and functional responses in PLA biofilms. Higher photoaging degrees exerted inhibitory effects on microorganisms in PLA, leading to reduced bacterial abundance and diversity. In contrast, PP exhibited great stability, with bacterial community structures gradually reorganizing during prolonged incubation before ultimately stabilizing. These findings further demonstrated that the photoaging degrees of MPs played a crucial regulatory role in microbial colonization and community succession.

CONCLUSIONS

This study systematically investigated the effects of photoaging on biofilm formation, microbial community composition and functions of PLA and PP in microcosm incubation. Results indicated that PLA and PP exhibited fragmentation and surface oxidation, alongside increased organic leaching under photoaging. As for PLA, severe photoaging caused environmental, metabolic and oxidative stress on microorganisms, thereby suppressing microbial growth and simplifying the bacterial community. The biofilm formation on PP underwent strong environmental selection in the initial stage, resulting in lower community abundance, while the abundance and diversity of bacterial communities gradually increased with extended incubation time. In addition, PP biofilm exhibited stable metabolic functions, while highly photoaged PLA exhibited reduced energy and carbohydrate metabolism functions. These findings provided a robust theoretical foundation for assessing the environmental fate and risks of PLA and PP in natural water. It should be noted that this study was conducted using surface water from a single freshwater source under controlled microcosm conditions, which cannot fully capture the natural variability in sunlight, temperature, hydrodynamics, and indigenous microbial communities across different aquatic environments. Therefore, future multisite studies under more realistic environmental fluctuations are needed to validate the ecological representativeness of these findings and elucidate how microenvironmental changes regulate microbial community and biofilm stability.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study: Liu, P.; Zhang, H.

Performed data acquisition, analysis and interpretation: Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.

Provided administrative, financial, technical, and material support: Liu, P., Jia, H.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Key R&D projects in Shaanxi Province (2025SF-YBXM-523), Dryland Agriculture Shaanxi Laboratory Foundation (2024ZY-JCYJ-02-25), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42477394), National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFC3713900), and the Key R&D projects in Henan Province (241111320200).

Conflicts of interest

Liu, P. and Jia, H. served as Guest Editors for the Special Issue “Interfacial Biodegradation of Plasticizers in (Micro)plastics” of the journal Emerging Contaminants and Environmental Health, but they were not involved in any part of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or final decision-making. The other authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J. R.; Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782.

3. Hofmann, T.; Ghoshal, S.; Tufenkji, N.; et al. Plastics can be used more sustainably in agriculture. Commun. Earth. Environ. 2023, 4, 982.

4. Ji, M.; Xiao, L.; Usman, M.; et al. Different microplastics in anaerobic paddy soils: altering methane emissions by influencing organic matter composition and microbial metabolic pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 144003.

5. Iftikhar, A.; Qaiser, Z.; Sarfraz, W.; et al. Understanding the leaching of plastic additives and subsequent risks to ecosystems. Water. Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics. 2024, 3, 5.

6. Mohanty, A. K.; Vivekanandhan, S.; Pin, J. M.; Misra, M. Composites from renewable and sustainable resources: challenges and innovations. Science 2018, 362, 536-42.

7. European Bioplastics. Bioplastics market development update 2022. https://docs.european-bioplastics.org/publications/market_data/2022/Report_Bioplastics_Market_Data_2022_short_version.pdf. (accessed 25 Dec 2025).

8. Gorrasi, G.; Pantani, R. Hydrolysis and biodegradation of poly(lactic acid). In Synthesis, structure and properties of poly(lactic acid). Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018; pp. 119-51.

9. Mistry, A. N.; Kachenchart, B.; Pinyakong, O.; et al. Bioaugmentation with a defined bacterial consortium: a key to degrade high molecular weight polylactic acid during traditional composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 367, 128237.

10. Ainali, N. M.; Kalaronis, D.; Evgenidou, E.; et al. Do poly(lactic acid) microplastics instigate a threat? A perception for their dynamic towards environmental pollution and toxicity. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 832, 155014.

11. Thompson, R. C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R. P.; et al. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838.

12. Luo, H.; Liu, C.; He, D.; et al. Environmental behaviors of microplastics in aquatic systems: a systematic review on degradation, adsorption, toxicity and biofilm under aging conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126915.

13. Zettler, E. R.; Mincer, T. J.; Amaral-Zettler, L. A. Life in the “plastisphere”: microbial communities on plastic marine debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7137-46.

14. Wen, B.; Liu, J. H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. R.; Gao, J. Z.; Chen, Z. Z. Community structure and functional diversity of the plastisphere in aquaculture waters: does plastic color matter? Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 740, 140082.

15. Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Xue, J. Biofilm-developed microplastics as vectors of pollutants in aquatic environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021,. 55, 12780-90.

16. Mohanan, N.; Montazer, Z.; Sharma, P. K.; Levin, D. B. Microbial and enzymatic degradation of synthetic plastics. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580709.

17. Nauendorf, A.; Krause, S.; Bigalke, N. K.; et al. Microbial colonization and degradation of polyethylene and biodegradable plastic bags in temperate fine-grained organic-rich marine sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 103, 168-78.

18. Singh, B.; Sharma, N. Mechanistic implications of plastic degradation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008, 93, 561-84.

19. Song, Y. K.; Hong, S. H.; Jang, M.; Han, G. M.; Jung, S. W.; Shim, W. J. Combined effects of UV exposure duration and mechanical abrasion on microplastic fragmentation by polymer type. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 4368-76.

20. Luo, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiang, Y.; He, D.; Pan, X. Aging of microplastics affects their surface properties, thermal decomposition, additives leaching and interactions in simulated fluids. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 714, 136862.

21. Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; et al. The aging behavior of degradable plastic polylactic acid under the interaction of environmental factors. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2024, 46, 163.

22. Sooriyakumar, P.; Bolan, N.; Kumar, M.; et al. Biofilm formation and its implications on the properties and fate of microplastics in aquatic environments: a review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 6, 100077.

23. Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Liang, S.; Guo, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Accelerated aging of polyvinyl chloride microplastics by UV irradiation: aging characteristics, filtrate analysis, and adsorption behavior. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103405.

24. Lim, J. H.; Kang, J. W. Assessing biofilm formation and resistance of vibrio parahaemolyticus on UV-aged microplastics in aquatic environments. Water. Res. 2024, 254, 121379.

25. He, S.; Tong, J.; Xiong, W.; et al. Microplastics influence the fate of antibiotics in freshwater environments: biofilm formation and its effect on adsorption behavior. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 442, 130078.

26. Wang, Z.; Ding, J.; Song, X.; et al. Aging of poly (lactic acid)/poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blends under different conditions: environmental concerns on biodegradable plastic. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 855, 158921.

27. Rajakumar, K.; Sarasvathy, V.; Thamarai Chelvan, A.; Chitra, R.; Vijayakumar, C. T. Natural weathering studies of polypropylene. J. Polym. Environ. 2009, 17, 191-202.

28. Christensen, G. D.; Simpson, W. A.; Younger, J. J.; et al. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: a quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1985, 22, 996-1006.

29. Lowry, O. H.; Rosebrough, N. J.; Farr, A. L.; Randall, R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265-75.

30. Dubois, M.; Gilles, K. A.; Hamilton, J. K.; Rebers, P. A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350-6.

31. Süssmann, J.; Walz, E.; Hetzer, B.; et al. Pressure-assisted isolation of micro- and nanoplastics from food of animal origin with special emphasis on seafood. J. Consum. Prot. Food. Saf. 2025, 20, 141-54.

32. Skic, K.; Adamczuk, A.; Gryta, A.; Boguta, P.; Tóth, T.; Jozefaciuk, G. Surface areas and adsorption energies of biochars estimated from nitrogen and water vapour adsorption isotherms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30362.

33. Sun, Z.; Dai, L.; Lai, P.; Shen, F.; Shen, F.; Zhu, W. Air oxidation in surface engineering of biochar-based materials: a critical review. Carbon. Res. 2022, 1, 32.

34. Xu, Y.; Ou, Q.; van der Hoek, J. P.; Liu, G.; Lompe, K. M. Photo-oxidation of micro- and nanoplastics: physical, chemical, and biological effects in environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 991-1009.

35. Zhang, J.; Xia, X.; Huang, W.; et al. Photoaging of biodegradable nanoplastics regulates their toxicity to aquatic insects (Chironomus kiinensis) by impairing gut and disrupting intestinal microbiota. Environ. Int. 2024, 185, 108483.

36. Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. A review on the release and environmental effects of biodegradable plastic degradation products. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 1140.

37. Du, C.; Sang, W.; Abbas, M.; et al. The interaction mechanisms of algal organic matter (AOM) and various types and aging degrees of microplastics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135273.

38. Rummel, C. D.; Lechtenfeld, O. J.; Kallies, R.; et al. Conditioning film and early biofilm succession on plastic surfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 11006-18.

39. Jacquin, J.; Cheng, J.; Odobel, C.; et al. Microbial ecotoxicology of marine plastic debris: a review on colonization and biodegradation by the “Plastisphere”. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 865.

40. Zhai, X.; Zhang, X. H.; Yu, M. Microbial colonization and degradation of marine microplastics in the plastisphere: a review. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1127308.

41. Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Grossart, H. P.; Gadd, G. M. Microplastics provide new microbial niches in aquatic environments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 6501-11.

42. Luo, H.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; et al. Leaching behavior and toxic effect of plastic additives as influenced by aging process of microplastics. J. Hazard. Mater. Plast. 2025, 1, 100007.

43. Zhao, C.; Xu, T.; He, M.; et al. Exploring the toxicity of the aged styrene-butadiene rubber microplastics to petroleum hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria under compound pollution system. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 227, 112903.

44. Jiang, A.; Pei, W.; Zhang, R.; Shah, K. J.; You, Z. Toxic effects of aging mask microplastics on E. coli and dynamic changes in extracellular polymeric matter. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 899, 165607.

45. Zheng, Y.; Qi, L.; Dai, L.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, C. Nitrogen form-driven shifts in microbial community and nitrogen cycling of microplastic surface biofilms. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 200, 107436.

46. Bocci, V.; Galafassi, S.; Levantesi, C.; et al. Freshwater plastisphere: a review on biodiversity, risks, and biodegradation potential with implications for the aquatic ecosystem health. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1395401.

47. Pinto, M.; Langer, T. M.; Hüffer, T.; Hofmann, T.; Herndl, G. J. The composition of bacterial communities associated with plastic biofilms differs between different polymers and stages of biofilm succession. PLoS. One. 2019, 14, e0217165.

48. Yang, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Feng, S. W.; et al. Temporal enrichment of comammox Nitrospira and Ca. Nitrosocosmicus in a coastal plastisphere. ISME. J. 2024, 18, wrae186.

49. Daims, H.; Lebedeva, E. V.; Pjevac, P.; et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 2015, 528, 504-9.

50. Zhu, Y.; Dou, Q.; Du, L.; Wang, Y. QseB/QseC: a two-component system globally regulating bacterial behaviors. Trends. Microbiol. 2023, 31, 749-62.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].