Advancing CO2 conversion: integrated use of dual active catalytic sites in flexible, porous polymeric porphyrin and ionic liquid composite networks

Abstract

The development of highly efficient, multifunctional catalysts featuring cooperative active sites is a complex yet vital endeavor. This study introduces an innovative approach through in situ polymerization, where flexible, cross-linked ionic polymers are synthesized within the channels of flexible, porous polymeric porphyrins. This process yields a series of interwoven frameworks endowed with dual catalytic active sites. The uniqueness of these catalysts lies in the synergistic interaction between metalated porphyrins and ionic components, greatly boosting their catalytic efficiency in the cycloaddition of CO2 and epoxides. The bifunctional catalysts not only surpass the individual constituents in performance but also demonstrate a significant superiority over their physical mixture. The structural flexibility and high density of active sites in these catalysts enable synergistic effects, leading to exceptional catalytic performance. This research marks a substantial leap in catalyst design, introducing a novel method for crafting bifunctional catalysts with dual-activation capabilities.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The escalating levels of CO2 in the atmosphere present significant global environmental challenges[1-4]. Tackling the increasing accumulation of CO2 is a critical issue, particularly focusing on its capture and conversion into useful substances[5-15]. Interestingly, CO2 offers several advantages as a resource: it is abundant, non-toxic, inexpensive, and renewable, making it an ideal C1 source for creating valuable organic compounds[16-19]. Hence, converting CO2 into value-added products is not only crucial for industrial processes but also a significant area of academic research, aiding in carbon recycling efforts.

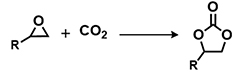

One effective method for utilizing CO2 is through its cycloaddition with epoxides to produce cyclic carbonates, which are extensively used in various industries[20-35]. Numerous catalytic systems have been investigated for this transformation, with the dual catalytic system combining Lewis acid and organic ionic molecular catalysts emerging as a particularly effective approach, allowing the reaction to occur under atmospheric conditions[36-43]. In the quest for complete recyclability of catalytic components, attention has shifted to heterogeneous bifunctional catalytic systems. These systems seek to address the spatial separation issue observed in traditional supported catalysts, a factor that frequently impedes efficient catalysis. The proposed strategy involves integrating halogen anion-containing flexible linear polymers with rigid frameworks such as covalent organic frameworks (COFs) or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), which have Lewis acid centers[44-46]. This combination is designed to foster a synergistic interaction between the two types of catalytic centers. However, a notable challenge in this approach is the potential loss of the linear polymers from the framework materials during extended reactions, due to the absence of specific interactions between these components. Addressing this issue is crucial for the long-term stability and efficiency of the catalytic system.

Recent studies have highlighted that polymers created through vinyl free-radical polymerization exhibit remarkable flexibility in solvent environments, enabling synergistic interactions between the functional species on the polymer chains[47-56]. Building on this insight, we investigated the use of polymers derived from vinyl polymerization that incorporate Lewis acid functionalities. These polymers were paired with cross-linked polyionic liquids to develop bifunctional synergistic catalysts. This innovative pairing of two flexible frameworks not only facilitates interactions between different active sites but also significantly improves the overall stability of the catalyst. For this approach, we utilized a porous organic polymer (POP), synthesized from a Mg metalated, vinyl-functionalized tetraphenylporphyrin monomer (v-TPPMg), as the primary host material [polymeric v-TPPMg (POP-TPPMg)]. Into this framework, we introduced the monomer 3,3’-(ethane-1,2-diyl)bis(1-vinyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium) bromide (v-BIL), infusing it into the pore channels of POP-TPPMg. This was followed by an in-situ polymerization process, resulting in a distinctive interwoven framework structure (POP-TPPMg-BIL-x, where x represents the mole ratio of the v-BIL to

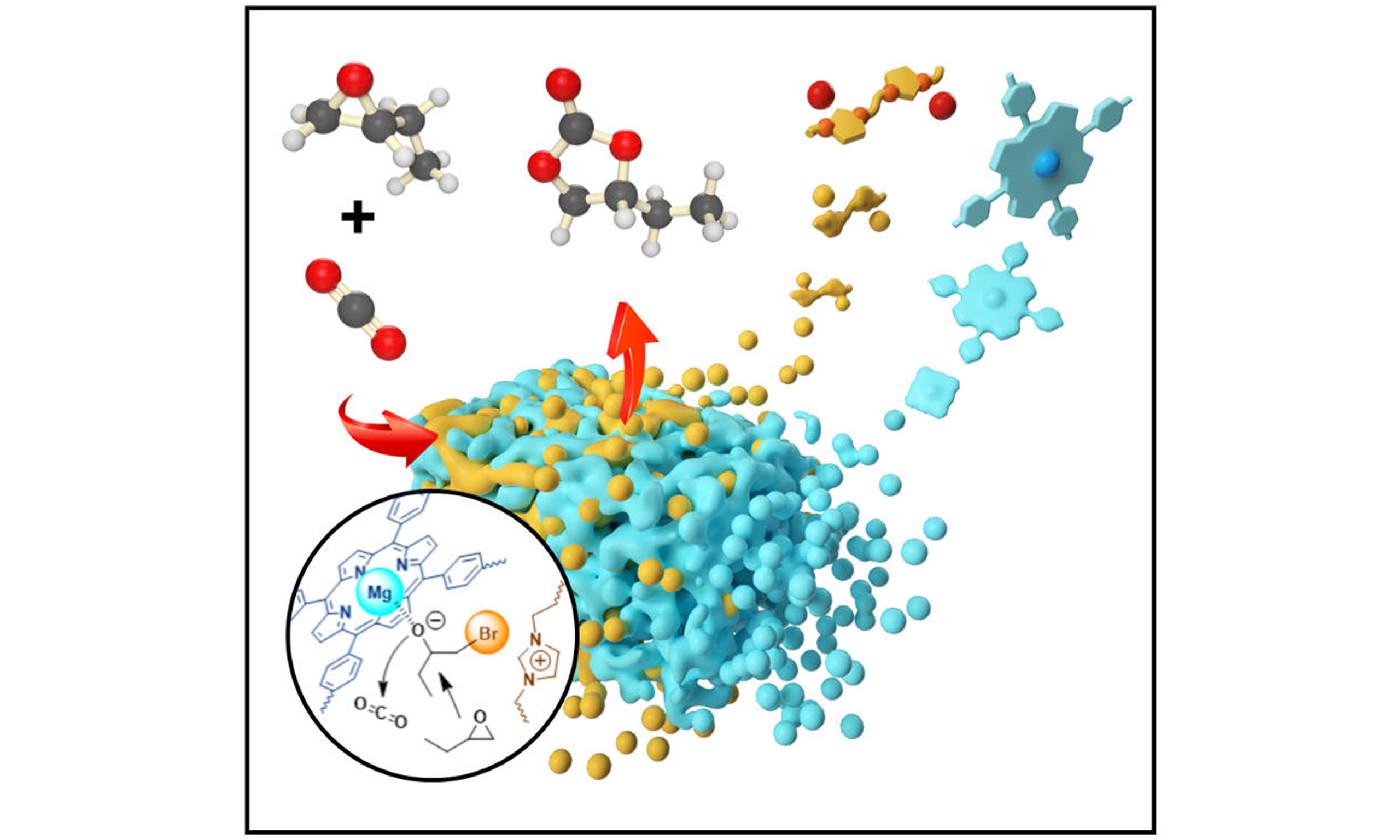

Figure 1. Conceptual schematic illustrating the creation of interwoven frameworks featuring dual catalytic active sites. The process involves the polymerization of a vinyl-functionalized Mg metalated tetraphenylporphyrin monomer acting as a Lewis acid, resulting in a porous framework. This is followed by the infiltration of a bivinyl-functionalized imidazolium salt and subsequent in situ polymerization to generate Lewis acid sites and Br- ions within the structure.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

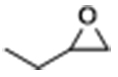

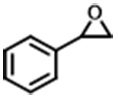

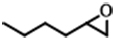

Pyrrole was obtained from Aladdin, while 4-bromostyrene was procured from Meryer Chemical Technology (Shanghai). Prior to use, both substances underwent distillation. Solvents such as tetrahydrofuran (THF) were distilled over LiAlH4; N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) underwent distillation over CaH2, and dichloromethane and triethylamine were similarly distilled. Various commercially available reagents including azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), MgBr2·Et2O, 1,2-epoxybutane, 1,2-epoxyhexane, styrene oxide, allyl glycidyl ether, butyl glycidyl ether, phenyl glycidyl ether, 2-ethylhexyl glycidyl ether and cyclohexene oxide, 1-vinylimidazole, 1,2-dibromoethane, and methanol were purchased at high purity levels and utilized without further purification. These reagents are all obtained from the Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of v-BIL

The synthesis of v-BIL was carried out under a N2 atmosphere. In a 25 mL Schlenk tube, 5 mL of methanol,

Synthesis of 4-vinylbenzaldehyde

The synthesis of 4-vinylbenzaldehyde commenced with the addition of 4-bromostyrene (18.2 g, 100 mmol) dropwise to a THF solution containing activated magnesium at 0 °C under a N2 atmosphere to form (4-vinylphenyl)magnesium bromide. Subsequently, an excess of DMF was added dropwise to the solution. The resulting mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature and then quenched with 50 mL of saturated NH4Cl solution. Following extraction with ethyl acetate, washing with brine, and drying with anhydrous MgSO4, the solution was filtered and further purified through flash column chromatography on silica gel, yielding 4-vinylbenzaldehyde (12.1 g) with a 91.7% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 9.99 (s, 1H), 7.84 (m, 2H), 7.55 (m, 2H), 6.77 (dd, 1H), 5.91 (d, 1H), 5.44 (d, 1H) ppm.

Synthesis of vinyl-functionalized porphyrin monomers

The synthesis of vinyl-functionalized porphyrin monomers (v-TPP) was carried out in a typical “one-pot” reaction, following a previously reported literature procedure[36]. In a flask, pyrrole (3.45 g, 10 mmol) and 4-vinylbenzaldehyde (6.80 g, 51.5 mmol) were combined with propionic acid (250 mL) pre-heated to 140 °C. After 1 h of reaction, the solution was cooled to room temperature. Subsequent to filtration, washing with methanol and ethyl acetate, and drying of the title compound, a purple crystalline porphyrin monomer was obtained (2.05 g) with a yield of 22.1%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.88 (s, 8H), 8.18 (d, 8H), 7.80 (d, 8H), 7.06 (dd, 4H), 6.07 (d, 4H), 5.50 (d, 4H), -2.73 (s, 2H) ppm.

Synthesis of v-TPPMg

The synthesis of v-TPPMg involved adding v-TPP (1.0 g, 1.4 mmol) to a three-neck round-bottom flask containing 150 mL of CH2Cl2. Subsequently, 22.6 mL of triethylamine and MgBr2·Et2O (7.16 g, 27.7 mmol) were introduced. After being stirred at room temperature for 15 min, the mixture was washed with water, the solvent was removed under vacuum, and the product was dried, yielding 0.95 g (92.0% yield). 1H NMR

Synthesis of POP-TPPMg

The POP-TPPMg was synthesized through a solvothermal polymerization process using the v-TPPMg monomer. In this procedure, 1 g of v-TPPMg (equivalent to 1.3 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL of DMF. Simultaneously, 100 mg of AIBN was added. The resulting mixture was placed in an autoclave and subjected to solvothermal conditions at 100 °C for 24 h. Following the polymerization reaction, the obtained polymer was subjected to purification steps. First, it was washed with DMF, and subsequently, a Soxhlet extractor was employed using dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) as the solvent for a duration of 72 h. The final product, the POP-TPPMg, was isolated with a yield of 96.0%.

Synthesis of POP-TPPMg-BIL-x

As a typical sample, POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 (1.57 representing the molar ratio of v-BIL to v-TPPMg) involved the dispersion of 0.2 g of POP-TPPMg in 10 mL of methanol within a 50 mL Schlenk tube. After stirring for 10 min, a mixture containing v-BIL at a quantity of 0.5 g (equivalent to 1.3 mmol) and 50 mg of AIBN was added to the solution. The resulting mixture underwent further stirring at room temperature for a duration of 24 h, following which the stirring was halted. Subsequently, the reaction system was heated to 100 °C and maintained at this temperature for an additional 24 h. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was subjected to filtration, and the obtained product was washed and dried. For other composites, the procedures are similar, except that the quantity of v-BIL varies.

Synthesis of POP-Bpy

In a typical run, 5,5’-divinyl-2,2’-bipyridine (1 g) was dissolved in DMF (10 mL), to which AIBN (25 mg) was then added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h before being transferred to an autoclave and heated at 100 °C for 24 h. Following the reaction, DMF was extracted with ethanol, and the resulting material was dried under vacuum to yield a light yellow solid, obtained in nearly quantitative yield.

Synthesis of POP-Bpy-BIL-x (where x represents the mole ratio of Bpy to imidazole moieties)

As a typical run, 0.2 g of POP-Bpy was dispersed in 10 mL of methanol and stirred for 10 min. A solution containing 0.57 g (1.6 mmol) of v-BIL and 50 mg of AIBN was then added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, followed by heating at 100 °C for an additional 24 h. After the reaction was complete, the mixture was filtered, and the resulting product was washed with methanol and dried. The final product was designated as POP-Bpy-BIL-0.86, indicating the mole ratio of Bpy to imidazole moieties. The synthesis of POP-Bpy-BIL-0.14 followed the same procedure as for POP-Bpy-BIL-0.86, but started with 0.2 g of POP-Bpy and 0.13 g of v-BIL.

Synthesis of POP-BpyCu-BIL-x

To synthesize POP-BpyCu-BIL-x, 250 mg of either POP-Bpy-BIL-0.86 or POP-Bpy-BIL-0.14 was swollen in 10 mL of DMF. Subsequently, 16.5 mg of Cu(OAc)2·H2O was added to the solution. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After stirring, the product was collected by filtration, sequentially washed with excess DMF, ethanol, and acetone, and then dried at 60 °C under vacuum. The synthesized products were designated as POP-BpyCu-BIL-0.86 and POP-BpyCu-BIL-0.14, with their copper contents determined to be 2.38 wt% and 2.69 wt%, respectively, as measured by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES).

Synthesis of polymeric v-BIL

Polymeric v-BIL (PBIL) was synthesized through the free radical polymerization of the v-BIL monomer. In a typical procedure, 1 g of v-BIL and 50 mg of AIBN were dissolved in 10 mL of MeOH and transferred to an autoclave for 24 h at 100 °C. Following the polymerization, the resulting polymer was washed with

Characterization

1H NMR spectra were acquired using a Bruker Avance-400 (400 MHz) spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). Chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) at δ = 0 ppm. Solid-state cross-polarization magic angle spinning 13C (MAS) NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian infinity plus

Catalytic cycloaddition of epoxides with CO2

The catalytic cycloaddition reactions were conducted in a 25 mL Schlenk tube containing a specific quantity of epoxides and diverse catalysts. The system underwent three vacuum purges, followed by the introduction of CO2 via a balloon. The transformation of epoxide was tracked using 1H NMR spectroscopy. In recycling trials, the catalyst was isolated through centrifugation, washed with CH2Cl2 three times, and dried under vacuum before its application in successive runs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Catalyst characterization

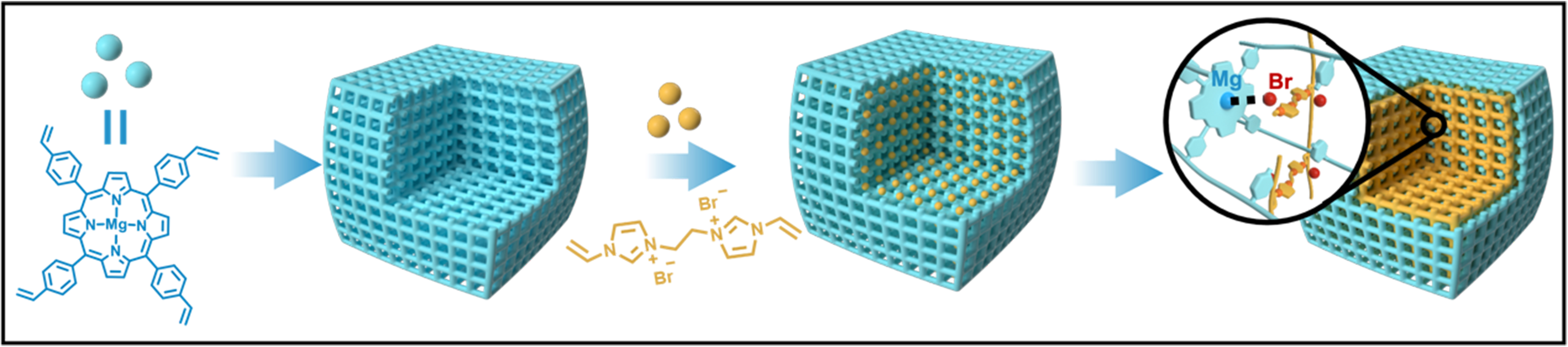

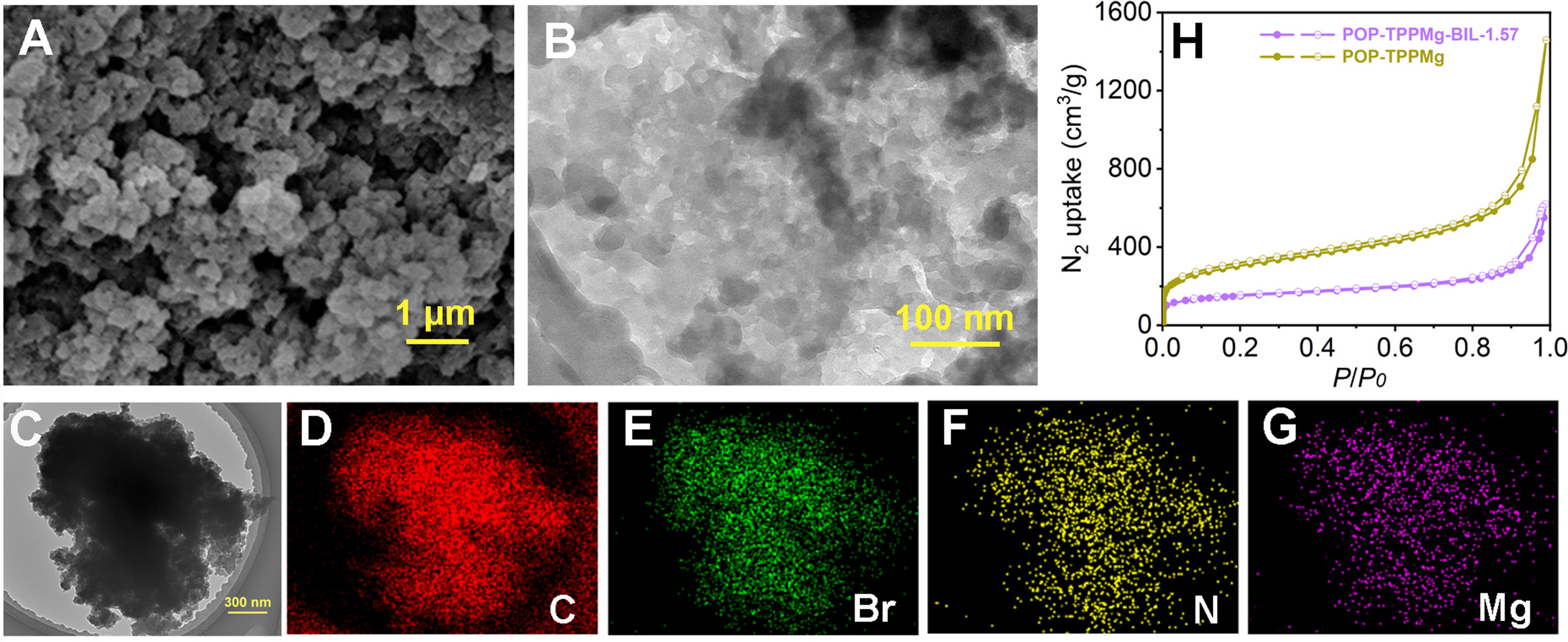

The formation of the interwoven framework structures in this study was achieved by integrating v-BIL monomers into the pore channels of the POP-TPPMg. This polymer was initially synthesized through the free radical-induced polymerization of vinyl groups, followed by the in-situ polymerization of the v-BIL monomers [Supplementary Figures 1 and 2]. The resulting composite materials were designated as POP-TPPMg-BIL-x. Experimental evaluations revealed that these composites are insoluble in common solvents such as DMF and CHCl3. Thermal gravity (TG) analysis further indicated the thermal stability of the composites, maintaining integrity up to 300 °C [Supplementary Figure 3]. For a comprehensive analysis, we chose POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 as a representative sample. To examine the morphological characteristics of these materials both before and after integration with the polymeric cross-linked ionic liquid, we utilized techniques such as SEM and TEM [Figure 2A and B, Supplementary Figure 4]. The corresponding images revealed maintained pore structures after integration with the polymeric ionic liquid, with no observable phase separation. TEM elemental mapping showcased a homogeneous dispersion of elements, including N, Br, and Mg, throughout the composite structure [Figure 2C-G]. The XPS spectrum of POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 before and after Ar+ etching shows comparable Br species content (4.15% vs. 2.83%), indicating a relatively homogeneous distribution of the linear polymeric ionic liquids throughout the catalyst. The observed particle sizes were hundreds of nanometers, displaying surfaces that appeared rough and constituted aggregates of much finer particles, approximately ten nanometers in size. N2 sorption isotherms conducted at -196 °C confirmed the high porosity of POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57, revealing a BET surface area of 534 m2/g and a pore volume of 0.96 cm3/g, which is smaller compared to the pristine POP-TPPMg. The latter exhibited a BET surface area and pore volume of 1,033 m2/g and 2.26 cm3/g, respectively [Figure 2H].

Figure 2. (A) SEM, (B) high-resolution TEM images, (C-G) large-scale TEM images, along with the corresponding elemental mapping of POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57, and (H) N2 sorption isotherms collected. SEM: Scanning electron microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; POP-TPPMg: polymeric Mg metalated, vinyl-functionalized tetraphenylporphyrin monomer.

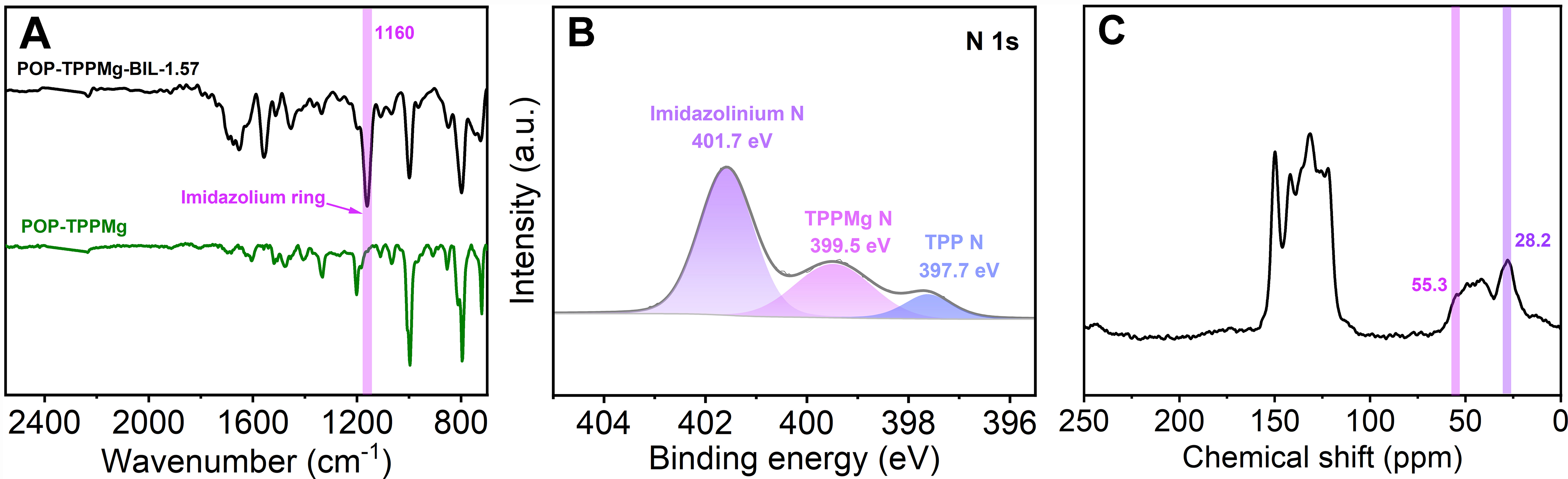

The local chemical structure of the composite was analyzed using various spectroscopic techniques, including Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), XPS, and solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy. In the FT-IR spectrum of POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57, the appearance of the characteristic bands of the imidazolium ring at 1,160 cm-1 confirmed the successful integration of ionic liquid species [Figure 3A]. This integration was further supported by the detection of a Br signal in the XPS survey of POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57. The N 1s XPS spectrum of the composite displayed three distinct peaks at binding energies of 397.7, 399.5, and

Figure 3. (A) FT-IR spectra, (B) N 1s XPS spectrum, and (C) solid-state 13C NMR spectrum of POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57. FT-IR: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; POP-TPPMg: polymeric Mg metalated, vinyl-functionalized tetraphenylporphyrin monomer.

Catalytic evaluation

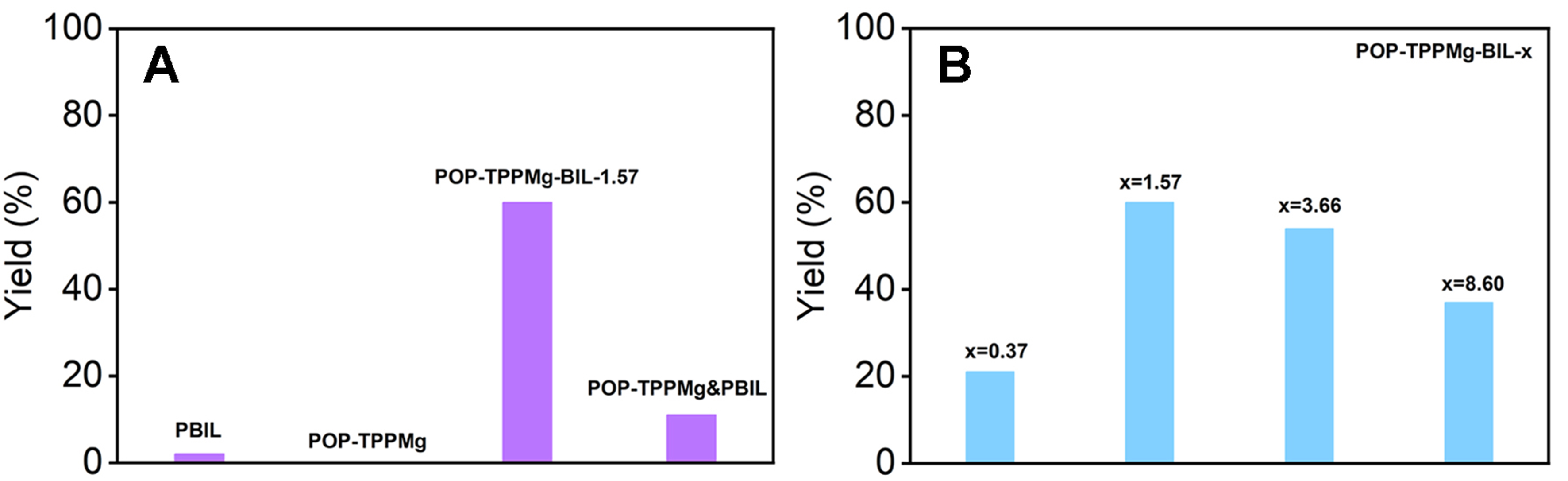

Figure 4 showcases the catalytic efficiency of various systems in the cycloaddition of 1,2-epoxybutane and CO2. This data highlights the successful synergy achieved by combining dual catalytic centers in the specially designed, flexible, porous polymeric porphyrin and ionic liquid composite networks. To amplify potential differences in catalytic efficiency, we performed the reactions in the presence of a relatively low catalyst dosage (0.167 mol% and 0.262 mol% based on the amount of Mg and Br species, respectively). Notably, POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 exhibited an impressive catalytic conversion of 60% for 1,2-epoxybutane after 48 h at 50 °C under atmospheric CO2 pressure, with selectivity for cyclic carbonate exceeding 99% [Figure 4]. To explore the synergistic effect of the two types of catalytic centers, we evaluated the performance of PBIL, POP-TPPMg, and their physical mixture POP-TPPMg&PBIL, under identical conditions. The results showed that the conversion for 1,2-epoxybutane was only 2%, 0%, and 11%, respectively, significantly lower than the 60% achieved by POP-BIL-TPPMg-1.57 [Figure 4A]. Moreover, a catalytic conversion of 93.0% and a selectivity of 99.0% can be achieved by increasing the catalyst loading of POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 to

Figure 4. (A) Comparison of catalytic performance in the cycloaddition of 1,2-epoxybutane with CO2 across diverse catalytic systems; (B) Exploration of the influence of the mole ratio of the v-BIL to the TPPMg species in POP-TPPMg. Note: The details of the standard reaction conditions are provided in the Experimental section. v-BIL: 3,3’-(ethane-1,2-diyl)bis(1-vinyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium); POP-TPPMg: polymeric Mg metalated, vinyl-functionalized tetraphenylporphyrin monomer.

Based on our experimental results and density functional theory (DFT) studies [Supplementary Figures 9 and 10], we propose a tentative reaction mechanism to explain the cooperative interaction between the metalloporphyrin and ionic components in our catalytic system. Initially, the metalloporphyrin serves as a Lewis acid center, activating the epoxide, while the ionic liquid acts as a Lewis base, supplying halide anions to promote the ring-opening of the epoxide. The calculated energy barrier for this step is 36.94 kcal/mol, significantly lower than the reported barrier of 59.0 kcal/mol for the uncatalyzed cycloaddition reaction between CO2 and epoxides. This finding highlights the synergy between the two catalytically active sites in POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57, which effectively reduces the energy barrier and accelerates the reaction. Subsequently, CO2 rapidly inserts between the Lewis acid center and the oxygen anion, followed by ring closure and the release of halide ions, ultimately leading to the formation of the cycloaddition product [Supplementary Figure 11][57,58].

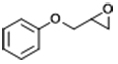

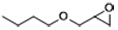

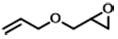

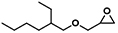

To assess the adaptability of the heterogeneous catalyst POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 with diverse substrates, its efficacy in CO2 cycloaddition was evaluated using seven different epoxide substrates. The data in Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 12, entries 1-6, indicate that POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 successfully converted all examined substrates into their corresponding products, achieving high yields, albeit some requiring slightly higher temperatures for optimal efficiency. Furthermore, the durability of POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 was explored, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 13. Over six recycling iterations, the catalyst consistently exhibited a high selectivity of 99%, with only a slight decline in activity [Table 1, entry 1]. XPS analysis was conducted to assess the composition and chemical state of the recycled POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 catalyst, revealing similar characteristics to the as-synthesized catalyst in terms of relative integrated areas and binding energies of Mg and Br species [Supplementary Figure 14]. Furthermore, N2 sorption isotherm and TEM images of the reused catalyst confirmed the preservation of its pore structure [Supplementary Figures 15 and 16]. Additionally, ICP analysis of Mg species in the POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 catalyst before and after catalysis shows that the content of Mg species remains consistent (0.87 mmol/g vs. 0.85 mmol/g), indicating the stability of the catalyst. Therefore, we attribute the reduced productivity of the POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 catalyst to catalyst degradation during recycling. To validate this, a larger-scale experiment was conducted with a substrate to catalyst ratio of 1,000. In this setup, POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 efficiently catalyzed the reaction of allyl glycidyl ether and CO2 into the target cyclic carbonates with an approximate yield of 88% [Table 1, entry 9]. Significantly, no traces of Mg or imidazolium species were detected in the filtrate, and the reaction was completely quenched after the catalyst was hot-filtered, confirming the heterogeneous nature of the catalyst [Supplementary Figure 17].

Cycloaddition of CO2 with various substrates over distinct catalystsa

| |||||

| Entry | Substrate | T (°C) | Time (h) | Yield (%)b | |

| 1 |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 50 | 48 | 93 (88) |

| POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57c | 50 | 48 | 72 | ||

| 2 |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 100 | 48 | 89 (84) |

| PBIL | 100 | 48 | 7.2 | ||

| POP-TPPMg | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg&PBIL | 100 | 48 | 13.3 | ||

| 3 |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 100 | 48 | 88 (82) |

| PBIL | 100 | 48 | 6.3 | ||

| POP-TPPMg | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg&PBIL | 100 | 48 | 17.9 | ||

| 4 |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 100 | 48 | 76 |

| PBIL | 100 | 48 | 23 | ||

| POP-TPPMg | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg&PBIL | 100 | 48 | 47.2 | ||

| 5 |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 100 | 48 | 99 (92) |

| PBIL | 100 | 48 | 21.6 | ||

| POP-TPPMg | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg&PBIL | 100 | 48 | 42.4 | ||

| 6 |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 100 | 48 | 83 |

| PBIL | 100 | 48 | 32.3 | ||

| POP-TPPMg | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg&PBIL | 100 | 48 | 63.3 | ||

| 7 |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 100 | 48 | 65.4 |

| PBIL | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg&PBIL | 100 | 48 | 2 | ||

| 8 |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 100 | 48 | 3 |

| PBIL | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg&PBIL | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| 9d |  | POP-TPPMg-BIL-1.57 | 100 | 108 | 88 (82) |

| PBIL | 100 | 48 | 31.8 | ||

| POP-TPPMg | 100 | 48 | < 1.0 | ||

| POP-TPPMg&PBIL | 100 | 48 | 58.5 | ||

To validate the universality of this approach, we successfully extended it to a bipyridine porous polymer derived from the radical polymerization of 5,5’-divinyl-2,2’-bipyridine, which was in situ integrated with a cross-linked ionic polymer (PBIL), and subsequently complexed with Cu2+ ions to create a Lewis acid and ionic liquid bifunctional polymer, POP-BpyCu-BIL-x [Supplementary Figures 18 and 19]. The cycloaddition reaction of CO2 with 1,2-epoxybutane demonstrated that under conditions of 50 °C and one atmosphere, POP-BpyCu-BIL-0.86 exhibited excellent catalytic performance, achieving a catalytic conversion of 70.4% over 48 h [Supplementary Table 3, entry 1]. Although this activity is lower than that of the corresponding homogeneous catalytic system [Supplementary Table 3, entries 2 and 3], it significantly surpasses the physically mixed binary catalytic system POP-BpyCu&PBIL, which achieved a yield of only 44.8% [Supplementary Table 3, entry 4]. This indicates effective cooperation between the two distinct catalytic centers in POP-BpyCu-BIL-0.86. This conclusion is further supported by POP-BpyCu-BIL-0.14, which, having a lower ionic liquid content and similar copper content as POP-BpyCu-BIL-0.86, exhibited lower catalytic activity with a yield of 43.5% under the same conditions [Supplementary Table 3, entry 5].

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our research has resulted in the development of composites featuring two distinct catalytically active species, each embedded within a flexible framework. These centers have demonstrated synergistic effects, significantly enhancing catalytic performance in the cycloaddition of CO2 and epoxides, showcasing notable improvements in both activity and selectivity. Subsequent examinations of these bifunctional heterogeneous catalysts revealed their facile separability and reusability, maintaining efficacy and stability across multiple cycles. Inspired by the diverse applications of polymers derived from vinyl polymerization, this methodology introduces a novel approach to designing catalytic systems with multiple, cooperatively functioning catalytic centers. This work represents a significant breakthrough in catalyst design, presenting an innovative strategy for the development of bifunctional catalysts endowed with dual activation capabilities.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of Fang Chen from Analytical Testing Center of the Department of Chemistry, Zhejiang University, in conducting SEM and TEM measurements.

Authors’ contributions

Designed the experiments, carried out characterization, analyzed data, interpreted results, and drew the pictures: Zheng, L.

Synthesized samples: Fang, C.; Han, J.

Conducted material characterization: Wang, Z.; Dai, T.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.

Directed and supervised the project, analyzed data, and wrote and revised the manuscript: Dai, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Sun, Q.

Availability of data and materials

The data substantiating the findings presented in this manuscript are available in the Supplementary Materials or can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21774101, 21902145, and 22072132), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY22B030006), and the Fundamental Research Funds of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (22062308-Y).

Conflicts of interest

Chen, Z. is affiliated with Kente catalysts Inc., Modern Industrial Cluster. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Gao, W.; Liang, S.; Wang, R.; et al. Industrial carbon dioxide capture and utilization: state of the art and future challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8584-686.

2. Breyer, C.; Fasihi, M.; Bajamundi, C.; Creutzig, F. Direct air capture of CO2: a key technology for ambitious climate change mitigation. Joule 2019, 3, 2053-7.

3. Alcalde, J.; Flude, S.; Wilkinson, M.; et al. Estimating geological CO2 storage security to deliver on climate mitigation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2201.

4. Davis, S. J.; Caldeira, K.; Matthews, H. D. Future CO2 emissions and climate change from existing energy infrastructure. Science 2010, 329, 1330-3.

5. Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Ma, X.; Gong, J. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3703-27.

6. Xu, X.; Wei, Q.; Xi, Z.; et al. Research progress of metal-organic frameworks-based materials for CO2 capture and CO2-to-alcohols conversion. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 495, 215393.

7. Song, K. S.; Fritz, P. W.; Coskun, A. Porous organic polymers for CO2 capture, separation and conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 9831-52.

8. Kumar, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Choudhury, J. Integrated CO2 capture and conversion to methanol leveraged by the transfer hydrogenation approach. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 927-33.

9. Siegel, R. E.; Pattanayak, S.; Berben, L. A. Reactive capture of CO2: opportunities and challenges. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 766-84.

10. Medinger, J.; Song, K. S.; Umubyeyi, P.; Coskun, A.; Lattuada, M. Magnetically guided synthesis of anisotropic porous carbons toward efficient CO2 capture and magnetic separation of oil. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 21394-402.

11. Wan, M.; Yang, Z.; Morgan, H.; et al. Enhanced CO2 reactive capture and conversion using aminothiolate ligand-metal interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 26038-51.

12. Zhang, B.; Shi, J.; Chu, Z.; et al. Lysine-modulated synthesis of enzyme-embedded hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks for efficient carbon dioxide fixation. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 5.

13. Dongare, S.; Coskun, O. K.; Cagli, E.; et al. A bifunctional ionic liquid for capture and electrochemical conversion of CO2 to CO over silver. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 7812-21.

14. Yin, Y.; Kang, X.; Han, B. Two-dimensional materials: synthesis and applications in the electro-reduction of carbon dioxide. Chem. Synth. 2022, 2, 19.

15. Kar, S.; Goeppert, A.; Galvan, V.; Chowdhury, R.; Olah, J.; Prakash, G. K. S. A carbon-neutral CO2 capture, conversion, and utilization cycle with low-temperature regeneration of sodium hydroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16873-6.

16. Di, J.; Hao, G.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Z. Defective materials for CO2 photoreduction: from C1 to C2+ products. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 482, 215057.

17. Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Kawi, S. Catalytic CO2 conversion to C1 chemicals over single-atom catalysts. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2301852.

18. Trogadas, P.; Xu, L.; Coppens, M. O. From biomimicking to bioinspired design of electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction to C1 products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202314446.

19. Yang, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, B.; et al. Topotactic synthesis of phosphabenzene-functionalized porous organic polymers: efficient ligands in CO2 conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 13763-7.

20. Luo, R.; Chen, Y.; He, Q.; et al. Metallosalen-based ionic porous polymers as bifunctional catalysts for the conversion of CO2 into valuable chemicals. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1526-33.

21. Zhong, H.; Su, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, R. Imidazolium- and triazine-based porous organic polymers for heterogeneous catalytic conversion of CO2 into cyclic carbonates. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 4855-63.

22. Luo, R.; Chen, M.; Zhou, F.; et al. Synthesis of metalloporphyrin-based porous organic polymers and their functionalization for conversion of CO2 into cyclic carbonates: recent advances, opportunities and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 25731-49.

23. Dai, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. Combination of binary active sites into heterogeneous porous polymer catalysts for efficient transformation of CO2 under mild conditions. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 618-26.

24. Wan, Y. L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Lei, Y. Z.; Wen, L. L. Poly(ionic liquid)-coated hydroxy-functionalized carbon nanotube nanoarchitectures with boosted catalytic performance for carbon dioxide cycloaddition. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2024, 653, 844-56.

25. Zhao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Liao, C.; et al. Cobalt-mediated switchable catalysis for the one-pot synthesis of cyclic polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 16974-9.

26. Liu, F.; Huang, K.; Wu, Q.; Dai, S. Solvent-free self-assembly to the synthesis of nitrogen-doped ordered mesoporous polymers for highly selective capture and conversion of CO2. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1700445.

27. Luo, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, K.; et al. Tailored covalent organic frameworks for simultaneously capturing and converting CO2 into cyclic carbonates. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 20941-56.

28. Huang, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F.; Dai, S. Synthesis of porous polymeric catalysts for the conversion of carbon dioxide. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 9079-102.

29. Liang, J.; Huang, Y.; Cao, R. Metal–organic frameworks and porous organic polymers for sustainable fixation of carbon dioxide into cyclic carbonates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 378, 32-65.

30. Han, W.; Ma, X.; Wang, J.; Leng, F.; Xie, C.; Jiang, H. L. Endowing porphyrinic metal-organic frameworks with high stability by a linker desymmetrization strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 9665-71.

31. Su, Y.; Yuan, G.; Hu, J.; et al. Recent progress in strategies for preparation of metal-organic frameworks and their hybrids with different dimensions. Chem. Synth. 2022, 3, 1.

32. Li, H.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Selenium confined in ZIF-8 derived porous carbon@MWCNTs 3D networks: tailoring reaction kinetics for high performance lithium-selenium batteries. Chem. Synth. 2022, 2, 8.

33. Liu, L.; Wang, S. M.; Han, Z. B.; Ding, M.; Yuan, D. Q.; Jiang, H. L. Exceptionally robust in-based metal-organic framework for highly efficient carbon dioxide capture and conversion. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 3558-65.

34. Feng, D.; Chung, W. C.; Wei, Z.; et al. Construction of ultrastable porphyrin Zr metal-organic frameworks through linker elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17105-10.

35. Song, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, S.; Wu, T.; Jiang, T.; Han, B. MOF-5/n-Bu4NBr: an efficient catalyst system for the synthesis of cyclic carbonates from epoxides and CO2 under mild conditions. Green. Chem. 2009, 11, 1031.

36. Dai, Z.; Sun, Q.; Liu, X.; et al. Metalated porous porphyrin polymers as efficient heterogeneous catalysts for cycloaddition of epoxides with CO2 under ambient conditions. J. Catal. 2016, 338, 202-9.

37. Xie, Y.; Wang, T. T.; Liu, X. H.; Zou, K.; Deng, W. Q. Capture and conversion of CO2 at ambient conditions by a conjugated microporous polymer. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1960.

38. Xie, Y.; Wang, T. T.; Yang, R. X.; Huang, N. Y.; Zou, K.; Deng, W. Q. Efficient fixation of CO2 by a zinc-coordinated conjugated microporous polymer. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 2110-4.

39. Gao, W. Y.; Chen, Y.; Niu, Y.; et al. Crystal engineering of an nbo topology metal-organic framework for chemical fixation of CO2 under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 2615-9.

40. Zhi, Y.; Shao, P.; Feng, X.; et al. Covalent organic frameworks: efficient, metal-free, heterogeneous organocatalysts for chemical fixation of CO2 under mild conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018, 6, 374-82.

41. Li, H.; Feng, X.; Shao, P.; et al. Synthesis of covalent organic frameworks via in situ salen skeleton formation for catalytic applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 5482-92.

42. Zhou, W.; Deng, Q. W.; Ren, G. Q.; et al. Enhanced carbon dioxide conversion at ambient conditions via a pore enrichment effect. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4481.

43. Sengupta, M.; Bag, A.; Ghosh, S.; Mondal, P.; Bordoloi, A.; Islam, S. M. CuxOy@COF: an efficient heterogeneous catalyst system for CO2 cycloadditions under ambient conditions. J. CO2. Util. 2019, 34, 533-42.

44. Sun, Q.; Aguila, B.; Perman, J.; Nguyen, N.; Ma, S. Flexibility matters: cooperative active sites in covalent organic framework and threaded ionic polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15790-6.

45. Aguila, B.; Sun, Q.; Wang, X.; et al. Lower activation energy for catalytic reactions through host-guest cooperation within metal-organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 10107-11.

46. Ding, M.; Jiang, H. Incorporation of imidazolium-based poly(ionic liquid)s into a metal–organic framework for CO2 capture and conversion. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 3194-201.

47. Sun, Q.; Ma, S.; Dai, Z.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F. A hierarchical porous ionic organic polymer as a new platform for heterogeneous phase transfer catalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 23871-5.

48. Sun, Q.; Aguila, B.; Verma, G.; et al. Superhydrophobicity: constructing homogeneous catalysts into superhydrophobic porous frameworks to protect them from hydrolytic degradation. Chem 2016, 1, 628-39.

49. Dai, Z.; Bao, Y.; Yuan, J.; Yao, J.; Xiong, Y. Different functional groups modified porous organic polymers used for low concentration CO2 fixation. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 9732-5.

50. Sun, Q.; Xiao, F. Porous polymeric catalysts constructed from vinylated functionalities. Acc. Mater. Res. 2022, 3, 772-81.

51. Wang, X.; Dong, Q.; Xu, Z.; et al. Hierarchically nanoporous copolymer with built-in carbene-CO2 adducts as halogen-free heterogeneous organocatalyst towards cycloaddition of carbon dioxide into carbonates. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 403, 126460.

52. Duval, A.; Avérous, L. Solvent- and halogen-free modification of biobased polyphenols to introduce vinyl groups: versatile aromatic building blocks for polymer synthesis. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1813-22.

53. Zhou, S.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Post-cationic modification of a porphyrin-based conjugated microporous polymer for enhanced removal performance of bisphenol A. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 14399-402.

54. Zhang, P.; Wang, S.; Ma, S.; Xiao, F. S.; Sun, Q. Exploration of advanced porous organic polymers as a platform for biomimetic catalysis and molecular recognition. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 10631-41.

55. Sun, Q.; Song, Y.; Aguila, B.; Ivanov, A. S.; Bryantsev, V. S.; Ma, S. Spatial engineering direct cooperativity between binding sites for uranium sequestration. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2001573.

56. Dai, Z.; Sun, Q.; Liu, X.; et al. A hierarchical bipyridine-constructed framework for highly efficient carbon dioxide capture and catalytic conversion. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1186-92.

57. Li, X.; Niu, X.; Fu, P.; et al. Macrocycle-on-COF photocatalyst constructed by in-situ linker exchange for efficient photocatalytic CO2 cycloaddition. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2024, 350, 123943.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].