Molecular structure design of polymers of intrinsic microporosity for membrane separation

Abstract

Polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs) combining microporosity and solution-processibility have witnessed their prosperous development in membrane separation. The rational molecular structure design of PIMs is of significant importance for tuning the pore structure of the membrane for precise separation. As an important branch of PIMs, polar groups-functionalized PIMs (PFPIMs) are endowed with high affinity to guest molecules, improved hydrophilicity, and enhanced interchain interaction, achieving more selective, specific, and stable separation. However, the development of PFPIMs has not yet been systematically summarized and critical details of chemical modification design for PFPIMs are lacking in previous reviews of PIMs. In this review, we summarize the research progress of PFPIMs, especially focusing on the various polarity functionalization modifications for preparing PFPIMs. In the meantime, we showcase the applications of PFPIM membranes including gas separation, liquid phase separation, and ion exchange or conducting in the battery. In the end, the existing challenges of PFPIM membranes are pointed out and their future development directions are outlooked.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

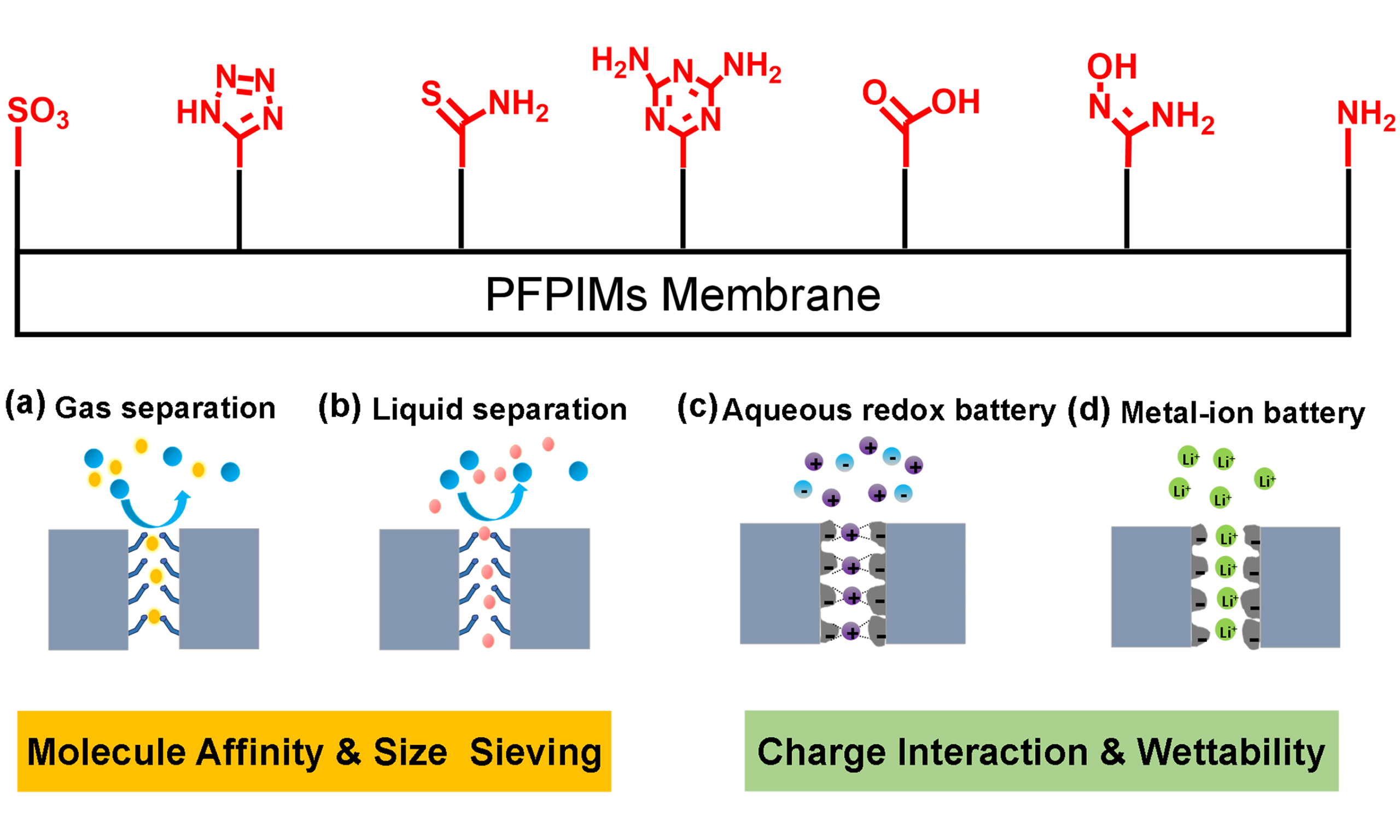

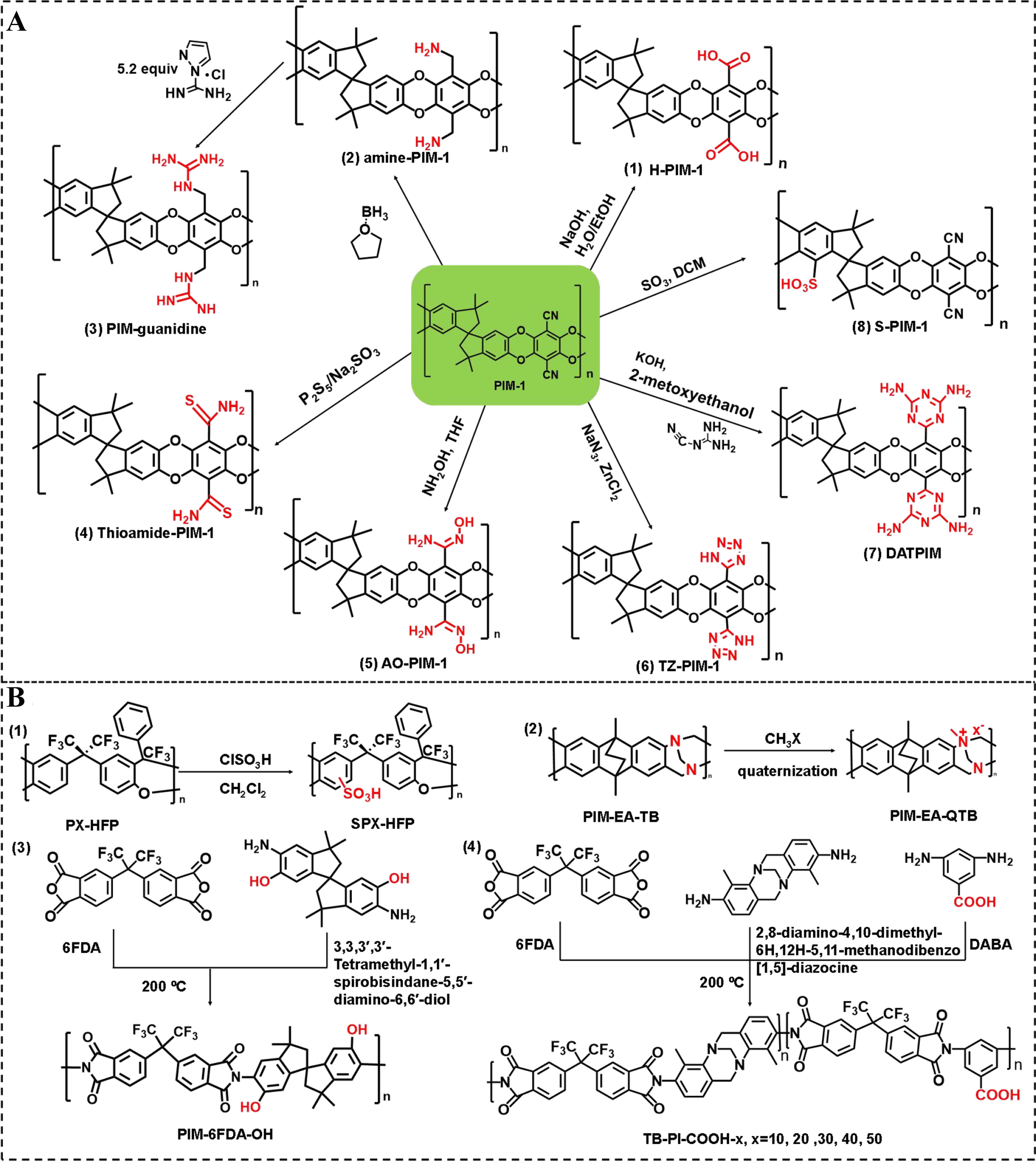

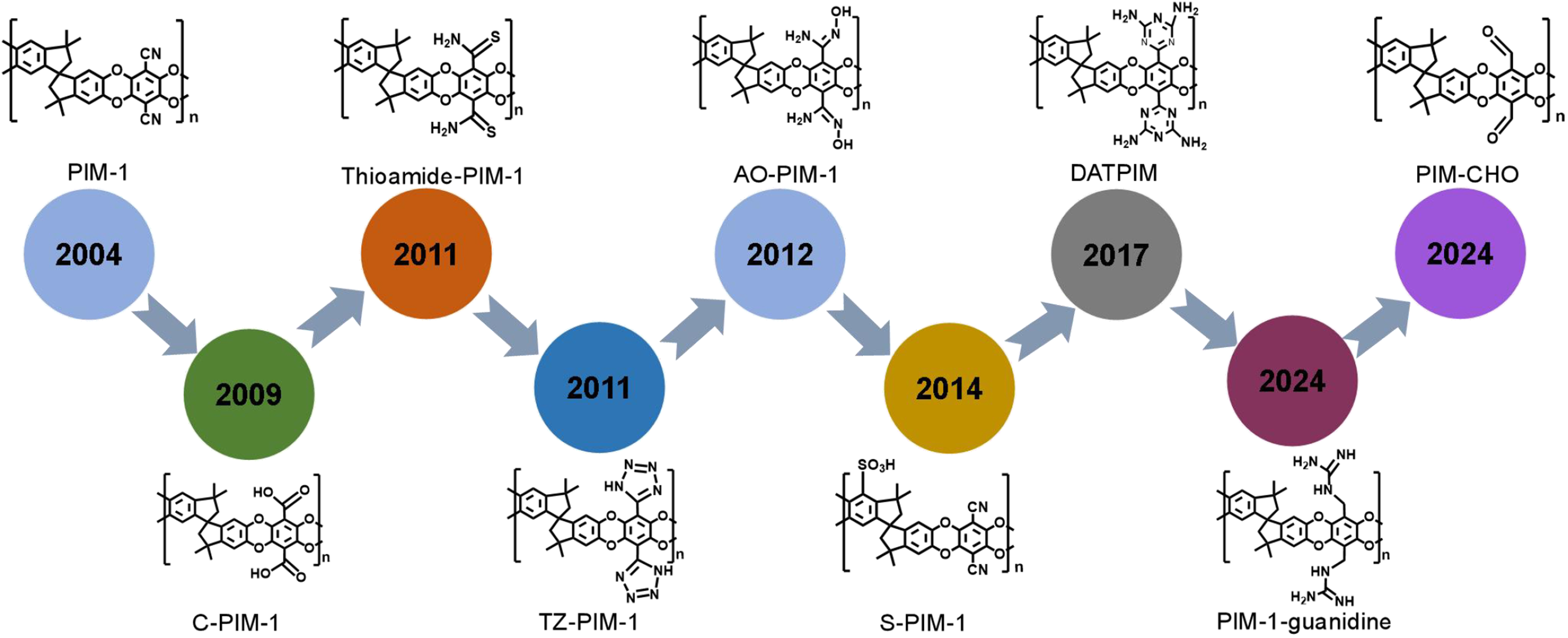

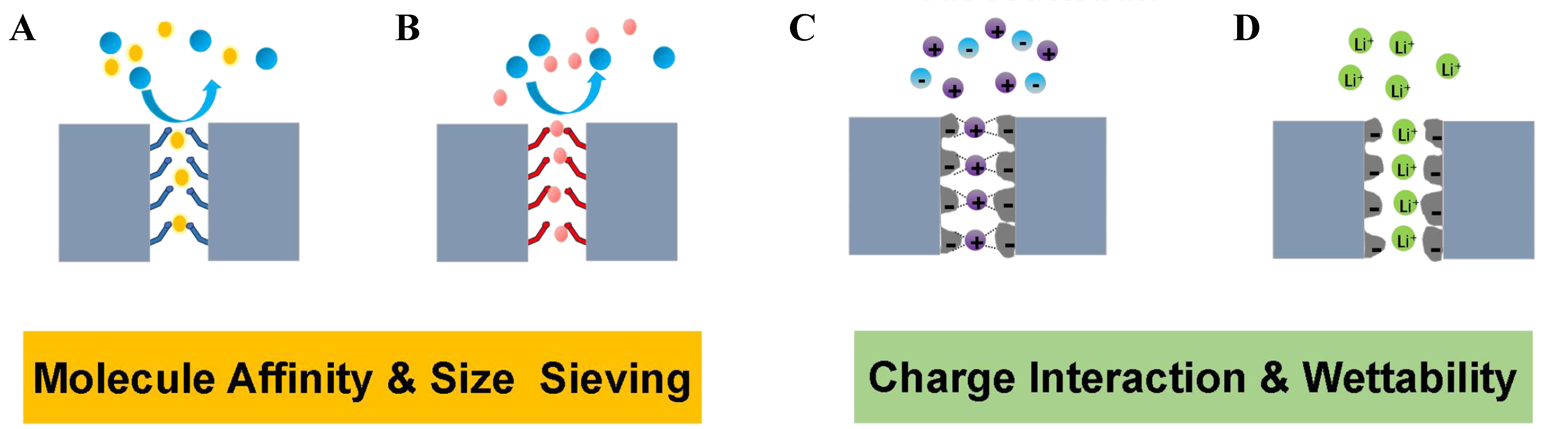

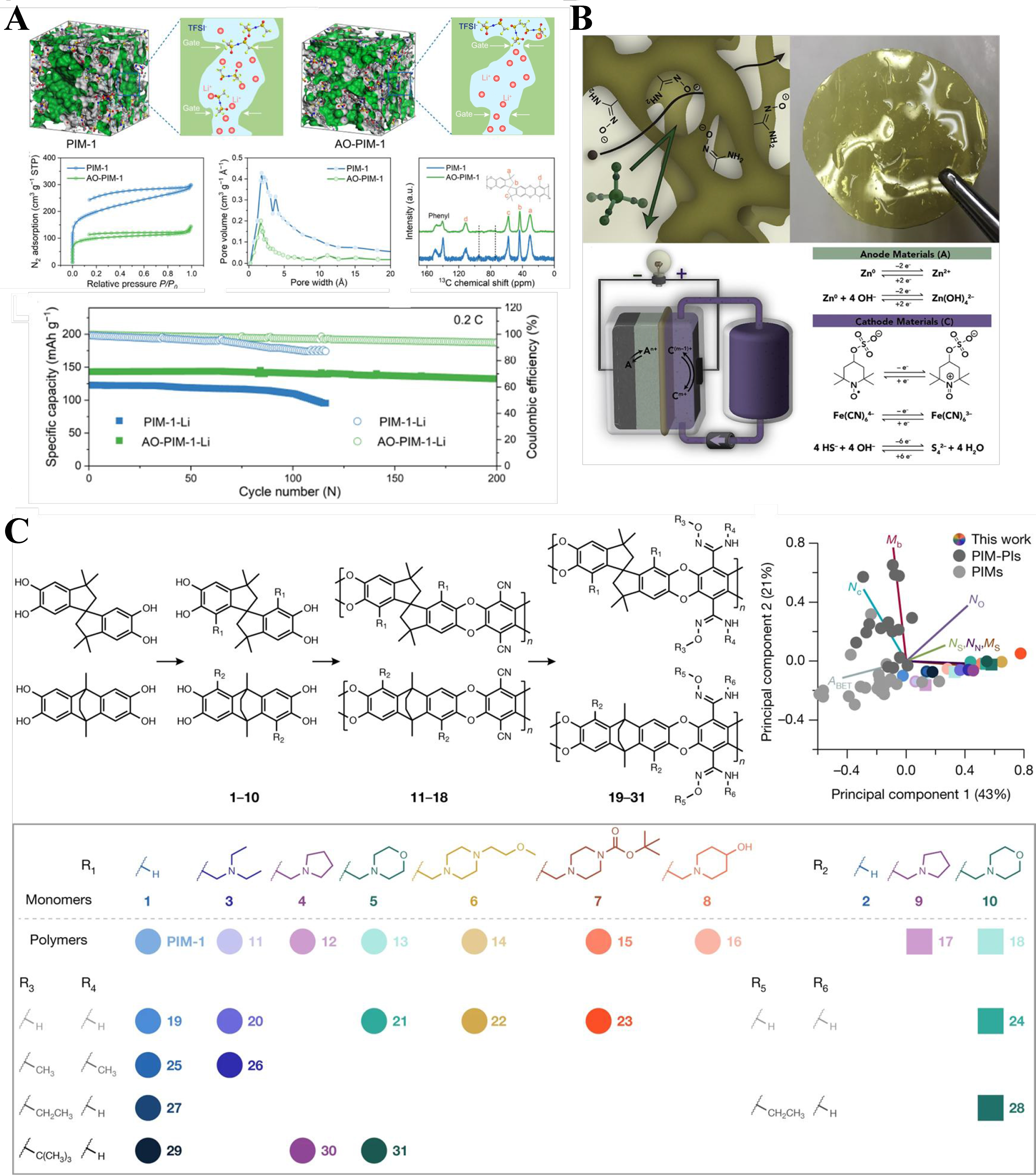

Polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs) were invented over 20 years ago by McKeown and Budd[1]. These polymers, with high Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area of up to 1,000 m2·g-1, are constructed with rigid and contorted backbone structures that induce loose chain packing, resulting in interconnected micropores [i.e., pores width < 2 nm, as defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC)][2]. Unlike framework-based microporous materials, PIMs with liner chain structure are always solution processable[3-8]. Since they came out, PIMs have been widely applied in the membrane-related separation[9-15]. Owing to the intrinsic microporosity, their membranes demonstrate ultrahigh gas permeability with moderate gas selectivity, contributing to the redefinition of Robeson’s upper bound which is recognized as an empirical upper bound for gas separation membranes, initially published in 1991 and revisited in 2008 by Robeson[16-19]. Various types of polymers have been synthesized and added to the PIM family for gas separation, including benzodioxane-based PIMs[20-23], Tröger’s-based PIMs (TB-PIMs)[24-27], polyimide-based PIMs (PI-PIMs)[28-34], benzocyclobutene-based PIMs[35,36], and so on. However, PIM membranes have shortcomings in gas separation such as relatively low gas selectivity, serious aging phenomena, and poor plasticization resistance[37]. These issues are closely related to the loose chain packing state and weak intermolecular interaction. Therefore, many efforts have been made to crosslink the polymer chains of PIMs, including thermal treatment, ultraviolet (UV) treatment, and ozone treatment, enhance gas selectivity and membrane stability[11,38-43]. However, the crosslinking treatment brought in seriously reduced the free volume and cavity sizes and thus declined the gas permeability. The researchers also adopted a post-polymerization modification strategy to anchor polar groups onto the main chain of PIMs to increase intermolecular interaction and enhance the stability of chain packing[44,45]. Polar groups can also increase the affinity of polymers to gas molecules and improve the gas separation performance of membranes[46-48]. Therefore, polar groups-functionalized PIMs (PFPIMs), as an important branch of PIMs, have aroused widespread interest among researchers, and considerable efforts have been made in this area. Up to now, numerous PFPIMs have been developed by post-modification methods and direct polycondensation reactions [Figure 1]. Among them, the Nitrile chemistry of PIM-1 is the most well-known and widely studied post-modification reaction. Various polar groups including carboxylic acid[49,50], amine[51], thioamide[52], tetrazole[53], amidoxime[54], triazine[55], and guanidine groups[56] are introduced as pendants of PIM-1’s main chain, which are listed in a timeline form in Figure 2. The sulfonation of PIMs is commonly accomplished via chlorosulfonic acid treatment[57]. For polyimide base PIMs, carboxylic acid and hydroxyl groups are often introduced via direct polycondensation reactions with functionalized monomers[58]. For TB-PIMs, quaternization of the amines offers a straightforward approach to generating a polymer chain with a positive charge[59,60]. The appearance of PFPIMs has largely put forward the development of PIMs in the membrane field. Due to the enhanced inter-molecular interaction, more selective and stable membranes for gas and liquid phase separation are achieved. The preparation of PFPIM membranes for various separation fields has been extensively investigated using diverse methods. The polar groups-functionalized PIM-1 membrane with a thickness of 60-200 µm was usually prepared using the solution-casting method[49-56,61]. Wang et al. prepared the amidoxime-functionalized PIM (AOPIM)-1 membrane with incorporated secondary pores by phase transformation method[62]. Jin et al. prepared AOPIM-1 thin film composite membrane of about 100 nm by spinning coating method[63]. Thompson et al. employed the roll-to-roll method to fabricate a spirobifluorene aryl diamine (SBAD) membrane for the purpose of crude oil separation[64]. Jue et al. successfully used a wet spinning method to fabricate pure PIM-1 hollow fibers[65]. Lasseuguette et al. utilized electrospinning method to produce AOPIM-1 fiber membranes specifically designed for dye removal from water[66]. Most of the PFPIMs are soluble in polar aprotic solvents including N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), and N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc), largely increasing their solution processability. This is beneficial for forming thin film or asymmetric membranes and promoting their application in liquid-related separations[67-69]. In addition, the polar groups enhance the hydrophilicity of PFPIMs and ion exchange capacity, enabling their application in aqueous batteries. For example, ion exchange membranes for aqueous redox flow batteries (RFBs) have been developed using AOPIM-1 and TB-PIMs[70,71]. The research development of PIMs has been summarized and discussed in several review papers. McKeown summarized the development history and the structure-property relationships of PIMs in a recent review[7]. A dedicated review by Low et al. discussed the gas separation performance of PIM membranes and also pointed out the existing issues hindering PIMs towards industrial-scale production[23]. Wang et al. also present perspectives on the status of PIMs, especially for PIM-based polyimide, in developing gas separation membranes[72]. Feng et al. introduced the recent advances of PIM membranes in gas separation and molecular separation liquid[73]. However, PFPIMs have not been systematically summarized and critical details of the chemical modifications design for PFPIMs are described in brief in these reviews. In this review, the recent progress made in the PFPIMs is summarized and various polarity functionalization modification methods for PFPIMs are described. In the meantime, we showcase the various applications of PFPIM membranes including gas separation [Figure 3A], liquid phase separation [Figure 3B], aqueous RFBs [Figure 3C], and metal-ion batteries [Figure 3D]. Finally, the challenges currently faced by PFPIM membranes were pointed out and their future directions were envisioned.

Figure 1. The preparation of representative PFPIMs. (A) The post-synthetic modifications of PIM-1; (B) Synthesis route of PFPIMs through direct sulfonation; quaternization of TB polymers; hydroxyl and carboxylic acid group functionalization on PIM-based polyimide. PFPIMs: Polar groups-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity; PIM: polymers of intrinsic microporosity; TB: Tröger’s-based.

Figure 2. The development history of PIM-1 derived PFPIMs. PIM: Polymers of intrinsic microporosity; PFPIMs: polar groups-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity.

POLAR GROUP FUNCTIONALIZATION OF PIMS

PIM-1 is the most classic material of PIMs and the post-modification of PIM-1 has attracted significant attention. Reactions involving nitrile groups and aromatic rings are often the focus of post-synthetic modifications of PIM-1. Carboxylated PIM-1 (C-PIM-1) has been reported as a product of the catalyzed hydrolysis of the PIM-1 [Figure 1A (1)]. In 2009, the synthesis of C-PIM-1 was initially reported as a result of the conversion process from nitrile to carboxylic acid, achieved through a rapid five-hour base hydrolysis procedure[50]. The hydrolyzed products with varying degrees of carboxylation were obtained by immersing PIM-1 in NaOH solution for durations ranging from one to five hours. Since then, this basic catalyzed hydrolysis method has become a general for preparing C-PIM-1. Strong hydrogen bonds generated via carboxylic acid groups enhance the interchain interactions and promote densification and compaction within the polymer matrix. The fractional free volume (FFV) elements are reduced, as evidenced by a decrease in the apparent BET surface area from 771 m2·g-1 of PIM-1 to 527 m2·g-1 of C-PIM-1. This carboxylation also offers additional avenues for subsequent treatment and modification[74]. It reveals that basic catalyzed hydrolysis predominantly yields carboxylated groups in PIM-1 in the early related reports. However, further investigations have shown the complex chemical structure in these basic catalyzed hydrolysis products. Satilmis et al. demonstrated that the hydrolysis product comprises a mixture of amide, carboxylic acid, ammonium carboxylate, and sodium carboxylate groups[75]. The base-hydrolysis method exhibited limited reactivity towards high molecular weight polymers, thereby diminishing the reaction kinetics of the already suboptimal amine leaving group. Additionally, it was suggested that acid hydrolysis might offer enhanced efficiency. Weng et al. propose to obtain PIM-COOH by carboxylation under environmental conditions of sulfuric acid[76]. Later, Mizrahi et al. optimized the acid hydrolysis process of PIM-1[49]. The carboxylic acid-functionalized PIM-COOH achieved a conversion rate of 89% within 48 h.

The reduction of nitrile groups to primary amine groups in PIM-1 can be achieved using appropriate reducing agents, such as borane complexes [Figure 1A (2)][51]. Owing to the strong acid-base interaction, the affinity to CO2 of the resultant amine-PIM-1 is highly enhanced. However, the too-strong affinity inhibits the transportation of CO2 molecules across the membrane, and thus, the CO2 permeability of the amine-PIM-1 membrane is seriously decreased compared to the pristine PIM-1 membrane. The amine-PIM-1 membrane exhibits a H2 selective separation performance due to the enhanced chain stiffness induced by hydrogen bonding among the amine groups while the pristine PIM-1 membrane demonstrates a CO2 selective separation performance. In addition, amine-PIM-1 can further react with guanidine to form amine-rich PIM-guanidine in a recent report by Roy et al. [Figure 1A (3)][56]. Guanidine has previously been studied for CO2 capture as both a sole sorbent and in combination with other Lewis bases, as it is a far better proton acceptor (Bronsted base) than simple amines. PIM-guanidine exhibited higher CO2 uptakes in humid natural gas combined cycle flue conditions than amin-PIM-1, indicating that the guanidine group has a higher CO2 affinity than the primary amine, possibly ascribed to the greater basicity. The reported CO2 uptake value is among the highest reported for all-polymer sorbents. The nitrile groups can also be converted to thioamide groups by a thionating agent [Figure 1A (4)][77]. The thioamide functionalization of PIM-1 exhibits micro-porosity albeit with diminished microporosity, thus performing high selectivity of CO2/N2 and low CO2 permeability[52]. In tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution, hydroxylamine can react with the cyanide group in PIM-1 to form AOPIM-1 [Figure 1A (5)][54]. The presence of bulkier amidoxime groups leads to an increase in the proportion of micropores compared to nitrile groups, which enhances the effect of molecular sieve. Importantly, the incorporation of amidoxime groups significantly enhances the affinity of the resulting membrane towards CO2, thereby establishing it as a highly promising candidate for efficient CO2 capture. In addition, the material is also suitable for efficient separation of H2S[78]. A click-chemistry-guided cycloaddition of nitrile with azide promotes the formation of tetrazole in PIM-1. This reaction was initially utilized by Du et al. to synthesize tetrazole-functionalized PIM (TZPIM)-1. The TZPIM membranes demonstrated promising potential as a membrane material for CO2 sorption [Figure 1A (6)][53]. In 2017, Wang et al. reported a Lewis-base-rich polymer named 2,4-diamino-1,3,5-triazine (DAT)-functionalized PIM (DATPIM) [Figure 1A (7)][55]. The Lewis-based sites in DAT significantly enhance CO2 affinity, resulting in a remarkable adsorption separation of CO2/CH4. Additionally, sulfonated PIM-1 has demonstrated enhanced effectiveness and improved gas separation performance compared to unmodified PIM-1 [Figure 1A (8)][79]. However, side reaction is prone to occur when strong agents such as concentrated sulfuric acid and chlorosulfonic acid are used for the sulfonation of PIMs[57]. Besides the polar group functionalization in the PIM-1 series, researchers have also developed polarity functionalization in other kinds of PIMs. Zuo et al. synthesized a PX-HFP through superacid-catalyzed polymerization between a, a-trifluoro acetophenone and bisphenol monomers[80,81]. The PX-HFP underwent smooth on-polymer sulfonation upon the addition of chlorosulfonic acid to yield the precipitated sulfonated polymer (SPX-HFP) [Figure 1B (1)]. Carta et al. developed a series of TB-based microporous polymers via acid-catalyzed TB formation reaction[60]. The TB polymer could be positively charged by quaternization reaction between tertiary amine groups with methyl iodide[59]. The quaternization degree could be well controlled with adjusting reaction conditions, and the resultant positively charged membranes demonstrate enhanced ion conductivity [Figure 1B (2)]. The polar group functionalization on PIM-based polyimide is also a common strategy for improving membrane separation performance. Ma et al. synthesized a novel contorted diamine monomer with hydroxyl functional groups[33], which was utilized to prepare a hydroxyl-functionalized microporous polyimide for membrane-based gas separation applications [Figure 1B (3)]. The results demonstrate the exceptional performance of the membrane in CO2/CH4 separation. Wang et al. designed and synthesized a series of TB structure-based microporous polyimides for gas separation and then reported the carboxylic acid groups (0%-50%) functionalization of TB polyimide for enhanced gas plasticization resistance [Figure 1B (4)][58]. The enhanced gas separation performance could be attributed to the strong acid-base interaction between -COOH and tertiary amine groups. Recently, Lee et al. report a facile approach to fine-tune the microstructure of PIM-1 by converting the nitrile groups of PIM-1 into aldehyde groups at room temperature. The result shows that the excellent H2/CH4 and H2/N2 separation performance of the PIM-CHO membrane approaching the most recent 2015 upper bound[82]. The rapid development of PFPIMs has significantly enhanced the utilization prospects in membrane-based molecular separation.

PFPIMS FOR MEMBRANE APPLICATIONS

Gas separation

PIM membranes have gained increasing attention in gas separation owing to their exceptional gas permeability, but they demonstrate relatively low selectivity and serious aging phenomena, especially at a decreased membrane thickness. In general, regulating the main chain structure of PIMs via introducing various building units with contorted and rigid structures can alleviate this issue, but these designs still have limitations. PFPIM membranes have witnessed considerable development in enhancing gas selectivity and membrane stability in recent years. Du et al. reported TZPIM by azide-based “click-chemistry” as shown in Figure 4A, which demonstrated significant improvement of CO2/N2 separation over PIM-1 (CO2/N2 selectivity of 14.4 and CO2 permeability of 5,135 Barrer), with CO2/N2 selectivity of 41 and CO2 permeability of ~3,000 Barrer in mixed-gas experiments [Figure 4B][53]. The existence of tetrazole groups enhances the CO2 adsorption capacity and thus increases the membrane’s affinity to CO2 molecules as demonstrated in Figure 4C. However, the introduced tetrazole groups enhance the interchain interaction, which decreases its solubility in most solvents. AOPIM-1 with enhanced CO2 affinity demonstrated much better solution processibility[54]. Swaidan et al. investigate the effect of the highly basic and polar amidoxime moiety on the microstructure and gas separation properties of PIM-1[83]. AOPIM-1 membranes demonstrated a high CO2/CH4 ideal selectivity of 34 with CO2 permeability of 1,153 Barrer, surpassing the 2008 upper bound. In particular, the AOPIM-1 membrane showed less selectivity loss than the original PIM-1 membrane under a CO2:CH4 mixed-gas feed.

Figure 4. PFPIM membrane for gas separations. (A) Schematic representing the structure of TZPIMs; (B) The position of TZPIMs and other membranes at the upper bound of CO2/N2 separation; (C) The CO2 adsorption isotherms of PIM-1 and TZPIMs[53]; (D) Scheme of the in-situ generated polymer molecular sieves within a PFPIMs based blending membrane; (E and F) The gas permeability and ideal gas selectivity of the blending membrane[84]; (G) Scheme of the hydrogen bond interface design in PFPIMs based mixed matrix membrane; (H) The wavenumber shifts of O-H stretching vibration with temperature; (I) The CO2/CH4 performance of PFPIMs-based mixed matrix membrane in comparison with Robeson upper bound[92]. PFPIM: Polar groups-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity; TZPIMs: tetrazole-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity; PIM: polymers of intrinsic microporosity.

Polymer blends have been recognized as an easy and effective route to combine the advantages of various materials for fabricating high-performance membranes. The miscibility and homogeneity of the different blend components is a major limitation for developing a blending membrane. The polar group functionalization can improve the miscibility of blending components by enhancing intermolecular interactions. Huang et al. demonstrated the fabrication of a blending membrane of partial AOPIM-1 and carboxylic acid-functionalized polyimide [Figure 4D][84]. Owing to the strong hydrogen bond in the interchain, the two polymers demonstrated good miscibility in the resulting blending membrane. After heat treatment, partial amidoxime-funtionalized PIM-1 (PAOPIM-1) is in-situ transformed into a network structure inside the polymer matrix as polymer molecular sieve fillers. High loading and homogeneous dispersion of filler are simultaneously achieved in the hybrid membrane. The overall separation performance of the corresponding hybrid membrane for various gas pairs, especially for hydrogen-related separation, much higher than pure AOPIM-1 and PIM-1, far exceeds the 2008 Robeson upper bound

The polar group functionalization also gives benefits for enhancing interfacial compatibility of fillers and polymer matrix in mixed matrix membrane[85-91]. Our group fabricated a series of PAOPIM-1-based mixed matrix membranes using an amine-functionalized metal-organic framework (NH2-UiO-66) as filler material [Figure 4G][92]. In the resulting PAOPIM-1/NH2-UiO-66 mixed matrix membranes, amidoxime in PAOPIM-1 and amine groups on the filler surface tend to form hydrogen bonds [Figure 4H], which highly increases the interfacial interaction, resulting in a nearly defect-free interface. The CO2 permeability of the optimized mixed matrix membrane is up to 8,425 Barrer and the CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 ideal selectivities are 27.5 and 23.0, respectively [Figure 4I]. The results demonstrated that the incorporation of NH2-UiO-66 significantly enhanced the CO2 permeability of the AOPIM-1 membrane, exhibiting a remarkable increase of 680% compared to the pure AOPIM-1 membrane and even over the PIM-1 (CO2 permeability of 5,135 Barrer)[92]. As we all know, the major drawback of PIMs for gas separation lies in the poor anti-aging properties of its membranes due to their non-equilibrium nature and significant free volume within the structure. The PAO-PIM-1/NH2-UiO-66 membrane exhibited more stable performance than PIM-1. The CO2 permeability of PAO-PIM-1/ NH2-UiO-66 membrane only decreased from 8,425 to 5,800 Barrer within 31 days, showing a 31% loss rate, which is less than the permeability loss rate of PIM-1/ NH2-UiO-66 membrane (49.2% loss rate after 28 days) and PIM-1 membrane (72% loss rate after 14 days). The result shows that the incorporation of polar groups into PIM-1 can enhance the interaction in the interchain structure and the interface between filler and matrix, consequently resulting in superior anti-aging performance. The aforementioned works substantiate the remarkable achievements of PFPIM membranes in gas separation. Compared to conventional PIMs, PFPIMs contain a significant number of large polar functional groups. This enhances the interchain interaction and restricts chain rotation, thereby impeding chain segment collapse. On the other hand, the presence of these polar groups enhances interactions with gas molecules, thereby significantly enhancing their solubility and resulting in excellent gas permeability and selectivity. The gas separation membrane of PFPIMs offers an additional advantage due to the presence of interconnected voids within its internal ultrafine pores, thereby significantly enhancing their molecule sieving properties[92].

Liquid phase separation

Liquid phase separation plays a pivotal role in numerous daily human activities and various industrial, medical, and environmental processes[93,94]. As PFPIMs have a large number of micropores and improved swelling resistance, they are regarded as the candidate material for liquid phase separation. Desalination is of great significance for water reuse and resource recycling. Reverse osmosis (RO) is regarded as the most widely accepted membrane-based desalination technology. The present RO membrane is confined to interfacially polymerized polyamide nanofilm, which has the disadvantage of natively low permeability. Our group prepared an AOPIM-1 membrane and finely tuned its structure by thermal treatment for RO desalination[95]. The amidoxime group enhanced the hydrophilicity property for the corresponding membrane. The thermal-treated AOPIM-1 with rigid and contorted backbone structure possesses highly innerconnected micropores, providing fast water transport channels while regulating the permeation behavior of ions. A water permeability of 1.92 × 10-7 m·kg·m-2·h·bar-1 with NaCl rejection as high as 98.5% was achieved, which is at the level between the two commercial membranes (the water permeabilities of BW30 and SW30 are 3.46 × 10-7 m·kg·m-2·h·bar-1and 1.68 × 10-7 m·kg·m-2·h·bar-1, respectively).

The trade-off between permeability and selectivity is an inherent drawback of pressure-driven membrane-based molecular separations. Molecule adsorption could achieve fast but discontinuous separation. Membrane adsorption process combines both the advantages of membranes and adsorption to create a more efficient membrane adsorption process. The polar group-functionalized, hydrophilic, and microporous AOPIM-1 was designed as a membrane adsorption material in our group. The AOPIM-1 adsorptive membrane can achieve fast separation of organic molecules from water with ultrahigh adsorption capacity [Figure 5A][62]. The separation of the model molecules by the AOPIM-1 membrane is primarily attributed to electrostatic interactions between the charged amidoxime groups and dye molecules with opposite charges. The water flux of the AOPIM-1 adsorptive membrane is two orders of magnitude over traditional separation membranes, simultaneously achieving > 99.9% removal rate. The adsorption capacity of the AOPIM-1 adsorptive membrane reaches 26.114 g·m-2 for adsorbing model molecules, 10-1,000 times higher than other adsorptive membranes. The pore size distribution reveals a noticeable reduction in the porosity of AOPIM-1 after adsorption, while the porosity of AOPIM-1 returns to its original state after desorption. In contrast to similarly sized traditional negatively charged polyether sulfone ultrafiltration membranes, almost all dye molecules permeate through the membrane without significant retention. Due to the high processing capacity, the AOPIM-1 adsorptive membrane could effectively purify the active pharmaceutical ingredients from a complex system. PFPIMs also found their application in lithium separation in an aqueous solution. Dong et al. reported a Li+ selective membrane based on PFPIMs, PIM-DB18C6-TB. TB units with contorted structure generated large free volume for ion transport, and dibenzo-18-crown-6 is incorporated as Li+ selective site [Figure 5B][96]. The resulting PIM-DB18C6-TB membrane exhibits excellent performance for Li+/Mg2+ separation, demonstrating a Li+/Mg2+ selectivity of 35.80 and 24.35, respectively. When compared with previous reports, the Li+/Mg2+ selectivity of the PIM-DB18C6-TB membrane surpasses the many reported membranes.

Figure 5. PFPIM membranes for molecular separation. (A) AOPIM-1 membrane for adsorptive separation of organic molecules[62]; (B) Fabrication of Crown functionalized TB polymer membrane for Li+ separation[96]. PFPIM: Polar groups-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity; AOPIM-1: amidoxime-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity-1; TB: Tröger’s-based.

The emerging technology of organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN) involves the utilization of a solvent-resistant nanofiltration membrane to separate and purify organic solvents[97]. PFPIMs also attracted significant attention for OSN membranes, because of their excellent anti-swelling, high polarity, and high porosity. An AOPIM-1 thin film was fabricated by spin coating following solvent activation[69]. The enhanced interchain interaction in AOPIM-1 contributed to the excellent anti-swelling of the obtained membrane in an organic solvent. The activation approach has the potential to significantly enhance the solvent permeance of the membrane. The optimized membrane demonstrated a high ethanol permeance of 15.5 L·m-2·h-1·bar-1 with high rejection rate for Rose Bengal. Moreover, this membrane exhibited comparable or better permeance than recently reported OSN membranes [such as p-CMP/PAN, (PIM/PEI)/PAN, TPIM/P84, etc.]. Although OSN membranes have achieved considerable developments in separating solutes from organic solvents, they could not fulfill the pore size and anti-solvent requirement for liquid hydrocarbon separation. Recently, Thompson et al. have made a breakthrough in designing PFPIMs linked with N-aryl or triazole bonds for crude oil fractionation[64]. The contorted molecular structure provides interchain-free volumes to promote solvent permeation. In addition, the strong intermolecular interactions provided by the polar groups contribute to non-interconnected microporosity and solvent resistance. N-aryl-linked spiro-polymers are synthesized by a polycondensation reaction between a spirodifluorene dibromo compound and aromatic amines [Figure 6A]. The incorporation of highly rigid spirobifluorene units and the promotion of interchain molecular interactions effectively mitigate membrane swelling during organic compound separation. The SBAD-1 membrane, characterized by a narrow pore size distribution, was employed for light crude oil separation. The membrane exhibited remarkable retention capabilities towards hydrocarbons with carbon numbers exceeding 12 in crude oil, achieving an overall retention rate exceeding 60%. The regulated pore structure enables the efficient separation of complex hydrocarbon mixtures, thereby offering potential in the fractionation of actual crude oil. In addition, Bruno et al. synthesized a series of spirocyclic polytriazoles with diverse monomeric structures as shown in Figure 6B, demonstrating their suitability for membrane-based separations[98]. The resulting polymers were synthesized via copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition, having high molecular weights and excellent solubility in common organic solvents and non-interconnected microporosity. These polymer membranes were utilized for fractionation of whole Arabian light crude oil and atmospheric tower bottom feeds. Membrane-based crude oil separation technology is still in the early stages of material exploration. The selection of membrane materials suitable for fractionation is limited, and the membrane flux is generally low. The separation accuracy relative to thermal distillation technology needs to be improved. However, the emergence of membrane-based crude oil fractionation technology provides a new energy-saving and environmentally friendly solution for fractionation. With the continuous innovation of materials and the continuous optimization of separation performance, it is expected to play an important role in the future petrochemical industry.

Figure 6. PFPIM membranes for crude oil separation. (A) Family of the SBAD materials (SBAD-1 to SBAD-4) and computational modeling of pore surfaces for the SBAD family and PIM-1, where teal represents accessible (interconnected) pores, and magenta represents nonaccessible pores[64]; (B) Preparation and hydrocarbon separation performance of solution-processable spirocyclic polytriazoles[98]. PFPIM: Polar groups-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity; SBAD: spirobifluorene aryl diamine; PIM: polymers of intrinsic microporosity.

The PFPIMs exhibit promising application prospects in the fields of ion separation and organic mixture separation. The rigid and twisted backbone structure of the membrane generates a significant proportion of micropores, thereby enhancing the permeation rate of the separation target. Within the nano-cavities, polar groups facilitate interactions with separated molecules and influence their migration rate. The pore size distribution of PFPIMs is relatively narrow compared to conventional PIMs lacking polar groups, thereby enhancing the membrane’s size-sieving performance. The future research should focus not only on enhancing the separation efficiency of various types of molecules, but more importantly, on improving their resistance to swelling to approach the operational standards of industrial applications.

Electrochemical applications

Ion exchange membranes for redox flow battery

In recent years, PFPIM membranes with high porosity and polarity functionalization have been investigated for electrochemical applications, especially as ion exchange membranes in energy storage batteries. The utilization of aqueous organic electrolytes in RFBs presents a promising avenue for the implementation of safe and cost-effective large-scale electrical energy storage. The ion exchange membranes play a pivotal role in RFBs by facilitating the rapid conduction of charge-carrier ions while effectively minimizing the cross-over of redox-active species. Later, Tan et al. present the performance evaluation of amidoxime-functionalized PIM membranes; the hydrophilic functionality combined with microporosity facilitates rapid ion transport and exhibits high molecular selectivity [Figure 7A and B][99]. The nitrile groups of PIM-1 were reacted with hydroxylamine to achieve controlled amidoxime conversions of 32%, 56%, 63%, 83%, and 100%. The AO modification brought a decrease in specific surface area, with values dropping from

Figure 7. PFPIM membranes in redox flow battery. (A) Schematic diagram of ion exchange in aqueous organic redox flow batteries; (B) Chemical structure of AOPIM-1; (C) Pore size distribution of AOPIM-1; (D) The position of PIMs with other ion-change membranes at the upper bound of K+/Mg2+ separation; (E) long-term stability of the cells assembled with AOPIM-1 membrane at a current density of

Metal ions conducting membrane for metal-ion battery

Metal ion batteries play an increasingly important role in people’s daily lives and social production due to their high energy storage capacity. Separator membranes are the most important part of metal ion battery components, which directly determines the capacity and long-term stability of the battery. In 2015, Li et al. utilized PIM-1 as a membrane platform for achieving high-throughput, ion-selective transport in non-aqueous electrolytes, thereby initially validating the applicability of PIM membranes in metal-ion batteries[100]. PFPIMs with a large number of polar groups and intrinsic pores show great promise in ion-conducting separator membranes owning to their size-sieving properties. Wang et al. present a comprehensive approach to enhancing the performance of solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) by employing PIM membranes as ion-conducting membranes in Figure 8A[101]. In this PFPIMs-based solid-state Li+ conductor, interconnected cavities for ion transport were formed through ionizable groups, thereby enhancing the conductivity of ions. Consequently, the Li+-exchanged PIMs (AOPIM-1-Li) membranes exhibit notable Li+ conductivities of 1.06 × 10-3 S·cm-1 at ambient temperature, respectively. The results demonstrate that the solid-state Li-O2 battery incorporating AOPIM-1-Li achieves a capacity of 600 at 200 mA·h·g-1 and exhibits stable operation for up to 247 cycles, which is significantly higher than that of PIM-Li (100 cycles) under identical conditions[101]. In addition to solid-state batteries, water-based electrolytes are frequently used in batteries; they are always alkaline. This will degrade the polymer membrane in the battery, causing permanent changes in the internal pore structure and seriously affecting the battery life. Baran et al. reported an aqueous-compatible PIM, AquaPIMs, to avoid undesirable pore shrinkage at high pH values

Figure 8. (A) PIM-1 and AOPIM-1 as solid ion conductors for solid-state lithium batteries[101]; (B) Ionizable amidoxime functionalities PIMs[102]; (C) Diversity-oriented synthesis of polymer membranes with ion solvation cages[103]. PIM: Polymers of intrinsic microporosity; AOPIM-1: amidoxime-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity-1.

Baran et al. proposed a diversity-oriented synthetic strategy for constructing PFPIMs with solvation cages for Li+[103]. Various bis(catechol) monomers were incorporated by Mannich reactions to introduce Li+-coordinating functionality within micropores [Figure 8C]. The PFPIMs with explicit Li+ coordinating sites displayed both higher ionic conductivities and higher Li+ transference numbers than PIMs without such functionality. These PFPIMs with the advantage of solid solvation cages for Li+ enable homogeneous plating and stripping of lithium metal when they were used as anode-electrolyte separators in high-voltage lithium metal batteries. The superior electrochemical performance provided by these PFPIM membranes suggests that a narrow pore size distribution and the presence of hydrophilic polar groups facilitate the rapid transport of target molecules and ions, and enhance their selectivity by size sieving and charge repulsion, thereby achieving high battery performance.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

As previously mentioned, PFPIMs possess a liner structure comprising stiff and twisted repeating units with incorporated polar groups. The presence of these polar groups within the chain segments enhances intermolecular forces and facilitates interactions with separation targets, thereby significantly enhancing separation performance. Consequently, various types of polar groups are designed based on specific separation requirements. This paper provides a comprehensive summary and discussion of feasible modification methods. However, only a limited number of approaches have demonstrated efficacy in achieving high-strength membrane applications enriched with polar groups.

Although PFPIMs have achieved rapid development in the field of membrane separations, some fundamental scientific issues and application challenges remain to be resolved. The microporosity of PFPIMs needs to be increased to enhance their molecular separation throughput. With polar group functionalization, the majority of PFPIMs have a decrease in surface area of around one to several hundred square meters per gram. Achieving ultrahigh surface areas in PFPIMs remains a significant challenge. Perhaps, the rational design of the polar group and construction of more rigid backbone structure would maintain high microporosity in PFPIMs. At the same time, the regulation of pore size distribution is highly required. The random and poorly controlled packing of line polymer chains leads to a rather broad range of pore sizes in PFPIMs. This broad pore size distribution poses challenges in targeting specific polymers for selective applications. Therefore, achieving precise control of pore size and the distribution is crucial for the development of PFPIMs in membrane separation. This objective may be accomplished by harnessing the inherent cavities within specific structures instead of relying solely on restricted polymer chain packing. Due to the confined mainchain structure of current PIMs, the types of polar groups modified onto PFPIMs are still very limited. It is an important direction to develop new types of PFPIMs with various polar functional groups to fully utilize both porosity and polar group functionality and expand the corresponding applications in membrane separation. The chem-physical instability of PFPIMs, such as low thermal resistance, poor mechanical strength, and low resistance to strong acids and alkalis, is also a notable aspect in membrane separation. To meet industrial demands, large-scale synthesis becomes imperative. Conversely, most PFPIMs are synthesized at a laboratory scale, necessitating consideration of scaling-up effects and potential crosslinking issues.

The appearance of PFPIMs greatly widens the application of PIMs-related material in membrane separation. The gas selectivity and separation stability of PFPIM membranes are highly enhanced compared to original PIM membranes. PFPIMs also achieved improved OSN performance and even accomplished nonthermal membrane fractionation of light crude oil. Adsorption membranes with ultrahigh processing capacity are constructed by AOPIM-1 for high flux nanosized organic molecule separation. PFPIMs also play an important role as separators in sustainable energy batteries. The abundant microporous structure in PFPIMs is tuned by the polar functional group, which gives benefits in controlling the transport of gas molecules, ions, and organic compounds. It could be expected that more interesting and attractive results would be discovered in PFPIMs.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Prepared the manuscript: Guo, L.

Performed manuscript correcting: Jin, J.; Wang, Z.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22378282, 218102), the Key Development Project of Jiangsu Province (BE2022056), Gusu Innovation and Entrepreneurship Leading Talent Plan (ZXL2023189), and the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (23KJB150029).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Budd, P. M.; Ghanem, B. S.; Makhseed, S.; McKeown, N. B.; Msayib, K. J.; Tattershall, C. E. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs): robust, solution-processable, organic nanoporous materials. Chem. Commun. 2004, 21, 230-1.

2. Mackintosh, H. J.; Budd, P. M.; Mckeown, N. B. Catalysis by microporous phthalocyanine and porphyrin network polymers. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 573-8.

3. Yuan, S.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, G.; Van, P. P.; Van, B. B. Covalent organic frameworks for membrane separation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2665-81.

4. Dou, H.; Xu, M.; Wang, B.; et al. Microporous framework membranes for precise molecule/ion separations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 986-1029.

5. Qian, Q.; Asinger, P. A.; Lee, M. J.; et al. MOF-based membranes for gas separations. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8161-266.

6. Lu, J.; Hu, X.; Ung, K. M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Metal–organic frameworks as a subnanometer platform for ion–ion selectivity. Acc. Mater. Res. 2022, 3, 735-47.

7. Mckeown, N. B. The structure-property relationships of Polymers of Intrinsic Microporosity (PIMs). Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2022, 36, 100785.

8. Comesaña-Gándara, B.; Chen, J.; Bezzu, C. G.; et al. Redefining the Robeson upper bounds for CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 separations using a series of ultrapermeable benzotriptycene-based polymers of intrinsic microporosity. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 2733-40.

9. McKeown, N. B.; Budd, P. M. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs): organic materials for membrane separations, heterogeneous catalysis and hydrogen storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 675-83.

11. Song, Q.; Cao, S.; Pritchard, R. H.; et al. Controlled thermal oxidative crosslinking of polymers of intrinsic microporosity towards tunable molecular sieve membranes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4813.

12. Lee, W. H.; Seong, J. G.; Hu, X.; Lee, Y. M. Recent progress in microporous polymers from thermally rearranged polymers and polymers of intrinsic microporosity for membrane gas separation: pushing performance limits and revisiting trade-off lines. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 58, 2450-66.

13. Ma, C.; Urban, J. J. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs) gas separation membranes: a mini review. Proc. Nat. Res. Soc. 2018, 2, 02002.

14. Topuz, F.; Abdellah, M. H.; Budd, P. M.; Abdulhamid, M. A. Advances in polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs)-based materials for membrane, environmental, catalysis, sensing and energy applications. Polym. Rev. 2024, 64, 251-305.

15. Kim, S.; Lee, Y. M. Rigid and microporous polymers for gas separation membranes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 43, 1-32.

17. Robeson, L. M.; Liu, Q.; Freeman, B. D.; Paul, D. R. Comparison of transport properties of rubbery and glassy polymers and the relevance to the upper bound relationship. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 476, 421-31.

18. Chen, L.; Su, P.; Liu, J.; et al. Post-synthesis amination of polymer of intrinsic microporosity membranes for CO2 separation. AIChE. J. 2023, 69, e18050.

19. Qiu, B.; Yu, M.; Luque-Alled, J. M.; et al. High gas permeability in aged superglassy membranes with nanosized UiO-66-NH2/cPIM-1 network fillers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 136, e202316356.

20. Du, N.; Robertson, G. P.; Song, J.; Pinnau, I.; Thomas, S.; Guiver, M. D. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity containing trifluoromethyl and phenylsulfone groups as materials for membrane gas separation. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 9656-62.

21. Tamaddondar, M.; Foster, A. B.; Luque-Alled, J. M.; et al. Intrinsically microporous polymer nanosheets for high-performance gas separation membranes. Macromol. Rapid. Commun. 2020, 41, e1900572.

22. Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; et al. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity having bulky substitutes and cross-linking for gas separation membranes. ACS. Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 987-95.

23. Low, Z. X.; Budd, P. M.; McKeown, N. B.; Patterson, D. A. Gas permeation properties, physical aging, and its mitigation in high free volume glassy polymers. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 5871-911.

24. Ishiwari, F.; Takeuchi, N.; Sato, T.; et al. Rigid-to-flexible conformational transformation: an efficient route to ring-opening of a Tröger’s base-containing ladder polymer. ACS. Macro. Lett. 2017, 6, 775-80.

25. Inoue, K.; Selyanchyn, R.; Fujikawa, S.; Ishiwari, F.; Fukushima, T. Thermal and gas adsorption properties of Tröger’s base/diaza-cyclooctane hybrid ladder polymers. ChemNanoMat 2021, 7, 824-30.

26. Ishiwari, F.; Miyake, S.; Inoue, K.; Hirose, K.; Fukushima, T.; Saeki, A. Two-step conformational control of a dibenzo diazacyclooctane derivative by stepwise protonation. Asian. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1377-81.

27. Ma, X.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, W.; et al. Unprecedented gas separation performance of a difluoro-functionalized triptycene-based ladder PIM membrane at low temperature. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 5404-14.

28. Park, H. B.; Jung, C. H.; Lee, Y. M.; et al. Polymers with cavities tuned for fast selective transport of small molecules and ions. Science 2007, 318, 254-8.

29. Han, S. H.; Misdan, N.; Kim, S.; Doherty, C. M.; Hill, A. J.; Lee, Y. M. Thermally rearranged (TR) polybenzoxazole: effects of diverse imidization routes on physical properties and gas transport behaviors. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 7657-67.

30. Guo, R.; Sanders, D. F.; Smith, Z. P.; Freeman, B. D.; Paul, D. R.; Mcgrath, J. E. Synthesis and characterization of thermally rearranged (TR) polymers: effect of glass transition temperature of aromatic poly(hydroxyimide) precursors on TR process and gas permeation properties. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013, 1, 6063.

31. Ghanem, B. S.; Mckeown, N. B.; Budd, P. M.; et al. Synthesis, characterization, and gas permeation properties of a novel group of polymers with intrinsic microporosity: PIM-polyimides. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 7881-8.

32. Ghanem, B. S.; McKeown, N. B.; Budd, P. M.; Selbie, J. D.; Fritsch, D. High-performance membranes from polyimides with intrinsic microporosity. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 2766-71.

33. Ma, X.; Swaidan, R.; Belmabkhout, Y.; et al. Synthesis and gas transport properties of hydroxyl-functionalized polyimides with intrinsic microporosity. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 3841-9.

34. Rogan, Y.; Starannikova, L.; Ryzhikh, V.; et al. Synthesis and gas permeation properties of novel spirobisindane-based polyimides of intrinsic microporosity. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 3813.

35. Lai, H. W. H.; Liu, S.; Xia, Y. Norbornyl benzocyclobutene ladder polymers: conformation and microporosity. J. Polym. Sci. Part. A. Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 3075-81.

36. Lai, H. W. H.; Benedetti, F. M.; Ahn, J. M.; et al. Hydrocarbon ladder polymers with ultrahigh permselectivity for membrane gas separations. Science 2022, 375, 1390-2.

37. Sanders, D. F.; Smith, Z. P.; Guo, R.; et al. Energy-efficient polymeric gas separation membranes for a sustainable future: a review. Polymer 2013, 54, 4729-61.

38. Song, Q.; Cao, S.; Zavala-Rivera, P.; et al. Photo-oxidative enhancement of polymeric molecular sieve membranes. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1918.

39. Li, F. Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ong, Y. K.; Chung, T. UV-rearranged PIM-1 polymeric membranes for advanced hydrogen purification and production. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2012, 2, 1456-66.

40. Li, F. Y.; Xiao, Y.; Chung, T.; Kawi, S. High-performance thermally self-cross-linked polymer of intrinsic microporosity (PIM-1) membranes for energy development. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 1427-37.

41. Ma, X.; Li, K.; Zhu, Z.; et al. High-performance polymer molecular sieve membranes prepared by direct fluorination for efficient helium enrichment. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 18313-22.

42. Ji, W.; Geng, H.; Chen, Z.; et al. Facile tailoring molecular sieving effect of PIM-1 by in-situ O3 treatment for high performance hydrogen separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 662, 120971.

43. Chen, X.; Fan, Y.; Wu, L.; et al. Ultra-selective molecular-sieving gas separation membranes enabled by multi-covalent-crosslinking of microporous polymer blends. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6140.

44. Satilmis, B.; Alnajrani, M. N.; Budd, P. M. Correction to hydroxyalkylaminoalkylamide PIMs: selective adsorption by ethanolamine- and diethanolamine-modified PIM-1. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 9071.

45. Jeon, J. W.; Kim, D.; Sohn, E.; et al. Highly carboxylate-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity for CO2-selective polymer membranes. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 8019-27.

46. Yanaranop, P.; Santoso, B.; Etzion, R.; Jin, J. Facile conversion of nitrile to amide on polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIM-1). Polymer 2016, 98, 244-51.

47. Satilmis, B.; Lanč, M.; Fuoco, A.; et al. Temperature and pressure dependence of gas permeation in amine-modified PIM-1. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 555, 483-96.

48. Satilmis, B.; Alnajrani, M. N.; Budd, P. M. Hydroxyalkylaminoalkylamide PIMs: selective adsorption by ethanolamine- and diethanolamine-modified PIM-1. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 5663-9.

49. Mizrahi, R. K.; Wu, A. X.; Qian, Q.; et al. Facile and time-efficient carboxylic acid functionalization of PIM-1: effect on molecular packing and gas separation performance. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 6220-34.

50. Du, N.; Robertson, G. P.; Song, J.; Pinnau, I.; Guiver, M. D. High-performance carboxylated polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs) with tunable gas transport properties. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 6038-43.

51. Mason, C. R.; Maynard-Atem, L.; Heard, K. W.; et al. Enhancement of CO2 affinity in a polymer of intrinsic microporosity by amine modification. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 1021-9.

52. Mason, C. R.; Maynard-Atem, L.; Al-Harbi, N. M.; et al. Polymer of intrinsic microporosity incorporating thioamide functionality: preparation and gas transport properties. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 6471-9.

53. Du, N.; Park, H. B.; Robertson, G. P.; et al. Polymer nanosieve membranes for CO2-capture applications. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 372-5.

54. Patel, H. A.; Yavuz, C. T. Noninvasive functionalization of polymers of intrinsic microporosity for enhanced CO2 capture. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9989-91.

55. Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; et al. Soluble polymers with intrinsic porosity for flue gas purification and natural gas upgrading. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605826.

56. Roy, A.; Holmes, H. E.; Baugh, L. S.; et al. Guanidine-functionalized PIM-1 as a high-capacity polymeric sorbent for CO2 capture. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 4393-402.

57. Kim, B. G.; Henkensmeier, D.; Kim, H.; Jang, J. H.; Nam, S. W.; Lim, T. Sulfonation of PIM-1 - towards highly oxygen permeable binders for fuel cell application. Macromol. Res. 2014, 22, 92-8.

58. Wang, Z.; Isfahani, A. P.; Wakimoto, K.; et al. Tuning the gas selectivity of Tröger’s base polyimide membranes by using carboxylic acid and tertiary base interactions. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 2744-51.

59. Madrid, E.; Rong, Y.; Carta, M.; et al. Metastable ionic diodes derived from an amine-based polymer of intrinsic microporosity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 10751-4.

60. Carta, M.; Malpass-Evans, R.; Croad, M.; et al. An efficient polymer molecular sieve for membrane gas separations. Science 2013, 339, 303-7.

61. Huang, M.; Lu, K.; Wang, Z.; Bi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, J. Thermally cross-linked amidoxime-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity membranes for highly selective hydrogen separation. ACS. Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 9426-35.

62. Wang, Z.; Luo, X.; Song, Z.; et al. Microporous polymer adsorptive membranes with high processing capacity for molecular separation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4169.

63. Jin, Y.; Song, Q.; Xie, N.; et al. Amidoxime-functionalized polymer of intrinsic microporosity (AOPIM-1)-based thin film composite membranes with ultrahigh permeance for organic solvent nanofiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 632, 119375.

64. Thompson, K. A.; Mathias, R.; Kim, D.; et al. N-Aryl-linked spirocyclic polymers for membrane separations of complex hydrocarbon mixtures. Science 2020, 369, 310-5.

65. Jue, M. L.; Breedveld, V.; Lively, R. P. Defect-free PIM-1 hollow fiber membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 530, 33-41.

66. Lasseuguette, E.; Malpass-Evans, R.; Casalini, S.; Mckeown, N. B.; Ferrari, M. Optimization of the fabrication of amidoxime modified PIM-1 electrospun fibres for use as breathable and reactive materials. Polymer 2021, 213, 123205.

67. Zhang, Z.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Nanofluidics for osmotic energy conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 622-39.

68. Zhu, Z.; Wang, D.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, L. Ion/molecule transportation in nanopores and nanochannels: from critical principles to diverse functions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8658-69.

69. Ogieglo, W.; Knozowska, K.; Puspasari, T.; et al. Unlocking complex chemical and morphological transformations during thermal treatment of O-hydroxyl-substituted polyimide of intrinsic microporosity: Impact on ethanol/cyclohexane separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 684, 121881.

70. Wang, A.; Tan, R.; Liu, D.; et al. Ion-selective microporous polymer membranes with hydrogen-bond and salt-bridge networks for aqueous organic redox flow batteries. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2210098.

71. Ye, C.; Tan, R.; Wang, A.; et al. Long-life aqueous organic redox flow batteries enabled by amidoxime-functionalized ion-selective polymer membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 134, e202207580.

72. Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Ghanem, B.; Alghunaimi, F.; Pinnau, I.; Han, Y. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity for energy-intensive membrane-based gas separations. Mater. Today. Nano. 2018, 3, 69-95.

73. Feng, X.; Zhu, J.; Jin, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Van, B. B. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity for membrane-based precise separations. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 144, 101285.

74. Jeon, J. W.; Kim, H. J.; Jung, K. H.; et al. Carbonization of carboxylate-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity for water treatment. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2020, 221, 1900532.

75. Satilmis, B.; Budd, P. M. Base-catalysed hydrolysis of PIM-1: amide versus carboxylate formation. RSC. Adv. 2014, 4, 52189-98.

76. Weng, X.; Baez, J. E.; Khiterer, M.; Hoe, M. Y.; Bao, Z.; Shea, K. J. Chiral polymers of intrinsic microporosity: selective membrane permeation of enantiomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 11214-8.

77. Kaboudin, B.; Elhamifar, D. Phosphorus pentasulfide: a mild and versatile reagent for the preparation of thioamides from nitriles. Synthesis 2006, 37, 224-6.

78. Yi, S.; Ghanem, B.; Liu, Y.; Pinnau, I.; Koros, W. J. Ultraselective glassy polymer membranes with unprecedented performance for energy-efficient sour gas separation. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw5459.

79. Dong, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, K.; et al. Significantly improved gas separation properties of sulfonated PIM-1 by direct sulfonation using SO3 solution. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 635, 119440.

80. Zuo, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, A.; et al. Sulfonated microporous polymer membranes with fast and selective ion transport for electrochemical energy conversion and storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 9564-73.

81. Olvera, L. I.; Zolotukhin, M. G.; Hernández-Cruz, O.; et al. Linear, single-strand heteroaromatic polymers from superacid-catalyzed step-growth polymerization of ketones with bisphenols. ACS. Macro. Lett. 2015, 4, 492-4.

82. Lee, T. H.; Joo, T.; Jean-Baptiste, P.; Dean, P. A.; Yeo, J. Y.; Smith, Z. P. Fine-tuning ultramicroporosity in PIM-1 membranes by aldehyde functionalization for efficient hydrogen separation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 24519-29.

83. Swaidan, R.; Ghanem, B. S.; Litwiller, E.; Pinnau, I. Pure- and mixed-gas CO2/CH4 separation properties of PIM-1 and an amidoxime-functionalized PIM-1. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 457, 95-102.

84. Huang, M.; Wang, Z.; Lu, K.; et al. In-situ generation of polymer molecular sieves in polymer membranes for highly selective gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 630, 119302.

85. Jiao, H.; Shi, Y.; Shi, Y.; et al. In-situ etching MOF nanoparticles for constructing enhanced interface in hybrid membranes for gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 666, 121146.

86. Zhu, S.; Bi, X.; Shi, Y.; et al. Thin films based on polyimide/metal–organic framework nanoparticle composite membranes with substantially improved stability for CO2/CH4 separation. ACS. Appl. Nano. Mater. 2022, 5, 8997-9007.

87. Shi, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z.; et al. Mixed matrix membranes with highly dispersed MOF nanoparticles for improved gas separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 277, 119449.

88. Wang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Fang, W.; Shrestha, B. B.; Huang, M.; Jin, J. Constructing strong interfacial interactions under mild conditions in MOF-incorporated mixed matrix membranes for gas separation. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 3166-74.

89. Bi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Jin, J. MOF nanosheet-based mixed matrix membranes with metal-organic coordination interfacial interaction for gas separation. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020, 12, 49101-10.

90. Huang, M.; Wang, Z.; Jin, J. Two-dimensional microporous material-based mixed matrix membranes for gas separation. Chem. Asian. J. 2020, 15, 2303-15.

91. Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Hu, L.; Jin, J. Interfacial design of mixed matrix membranes for improved gas separation performance. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3399-405.

92. Wang, Z.; Ren, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, F.; Jin, J. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity/metal–organic framework hybrid membranes with improved interfacial interaction for high-performance CO2 separation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017, 5, 10968-77.

93. Sholl, D. S.; Lively, R. P. Seven chemical separations to change the world. Nature 2016, 532, 435-7.

94. Shannon, M. A.; Bohn, P. W.; Elimelech, M.; Georgiadis, J. G.; Mariñas, B. J.; Mayes, A. M. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 2008, 452, 301-10.

95. Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; et al. Thermal treated amidoxime modified polymer of intrinsic microporosity (AOPIM-1) membranes for high permselectivity reverse osmosis desalination. Desalination 2023, 551, 116413.

96. Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Crown ether-based Tröger’s base membranes for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 665, 121113.

97. Wang, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Fang, W.; Jin, J. Polymer membranes for organic solvent nanofiltration: recent progress, challenges and perspectives. Adv. Membr. 2023, 3, 100063.

98. Bruno, N. C.; Mathias, R.; Lee, Y. J.; et al. Solution-processable polytriazoles from spirocyclic monomers for membrane-based hydrocarbon separations. Nat. Mater. 2023, 22, 1540-7.

99. Tan, R.; Wang, A.; Malpass-Evans, R.; et al. Hydrophilic microporous membranes for selective ion separation and flow-battery energy storage. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 195-202.

100. Li, C.; Ward, A. L.; Doris, S. E.; Pascal, T. A.; Prendergast, D.; Helms, B. A. Polysulfide-blocking microporous polymer membrane tailored for hybrid Li-sulfur flow batteries. Nano. Lett. 2015, 15, 5724-9.

101. Wang, X. X.; Song, L. N.; Zheng, L. J.; et al. Polymers with intrinsic microporosity as solid ion conductors for solid-state lithium batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 135, e202308837.

102. Baran, M. J.; Braten, M. N.; Sahu, S.; et al. Design rules for membranes from polymers of intrinsic microporosity for crossover-free aqueous electrochemical devices. Joule 2019, 3, 2968-85.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].