Graphdiyne: research advances in synthesis strategy

Abstract

Over the past 15 years, the new carbon allotrope graphdiyne (GDY) has been artificially synthesized and has rapidly garnered attention in fields such as energy, catalysis, electronics, and healthcare. Despite its promising potential, the synthetic methods for GDY and its derivatives have been constrained by limitations in application scenarios. This mini-review provides an overview of the synthetic methods for GDY developed in the past 15 years, including the synthesis of pristine GDY on Cu foil, interface-limited synthesis (liquid-liquid, gas-liquid, and solid-liquid interfaces), explosion techniques, chemical vapor deposition, and the preparation of GDY derivatives. The advancement of these methods has significantly broadened the range of applications for GDY-based nanomaterials across various scientific fields. This review not only summarizes GDY synthesis techniques but also discusses key factors influencing the quality of GDY synthesis, offering a novel perspective for the design of GDY-based nanomaterials.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The preparation of novel carbon allotropes with one-, two- or three dimensions has been a research frontier in the past two to three decades[1-3]. Carbon has three hybrid states: sp3, sp2, and sp, and each hybrid state can form different carbon allotropes. For example, sp3-hybridized carbon can form diamond and amorphous carbon; sp2-hybridized carbon can form fullerenes, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene[4-6]. Scientists have successively discovered some new carbon allotropes: the fullerene (C60), CNTs, and graphene[7,8], which have become the forefront and hotspot of international academic research[9]. The enthusiasm and interest in the research of new carbon allotropes have never diminished, especially for carbon materials formed by sp-hybridized carbon. This is because the C≡C triple bonds formed by sp-hybridized carbon are highly conjugated structures and have excellent physicochemical properties[10,11].

The idea that the graphdiyne (GDY) structure formed by sp2 and sp-hybridized carbon can exist stably was first proposed by theoretical chemist Baughman[12], which has sparked numerous attempts by researchers. Until 2010, Li et al. proposed the synthesis of GDY on the copper foil via chemical methods and successfully obtained large-area (3.61 cm2) GDY thin films for the first time[13]. GDY has quickly gained widespread attention in fields such as electronics, energy, catalysis, and medicine[14-20]. This groundbreaking work has propelled the development of materials into a new stage. With the limitations of application scenarios and the continuous advancement of synthesis technology, simple synthesis methods have been continuously developed, expanding the wide application of GDY in various fields[21-23].

In the past 15 years, some reviews have summarized the preparation of GDY-based composite nanomaterials and many applications in catalysis, environmental remediation, energy engineering, and other fields[24-27] It is very urgent to timely summarize and continuously update the synthesis technology of GDY. In this review, we summarized the synthetic strategies of GDY, containing pristine GDY synthesis on Cu foil, interface limited synthesis (liquid-liquid, gas-liquid, and solid-liquid interface), explosion, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and the preparation of GDY derivatives etc. We not only summarized the synthesis technology of GDY, but also discussed factors such as the synthesis quality of GDY, providing a new perspective for the design of GDY nanomaterials. We believe that summarizing the synthesis methods of GDY will further stimulate new synthesis methods, promote continuous innovation of GDY-based nanomaterials, and be applied in more fields to make greater contributions to human society.

MOLECULAR STRUCTURE AND PHYSICOCHEMICAL PROPERTIES

In 1987, Baughman et al. predicted the molecular model of graphyne for the first time through theoretical calculations, with crystallization energy (12.4 kcal/mol carbon)[28]. Haley et al. put forward a structural model of the GDY, with an enthalpy of formation of 18.3 kcal/mol carbon in 1997[29]. Graphynes, including the graphynes and the GDYs, are composed of linear alkynes connected by C=C, =C=C= or benzene rings as connecting units [Figure 1A]. In terms of hybridization forms, graphynes usually include C atoms with the sp and sp2 hybridized forms. In 2010, Li et al. firstly synthesized GDY thin films with an area of ~3.6 cm2 on the Cu foil through C-C cross-coupling reactions utilizing hexaethylbenzene (HEB)[13]. From the first theoretical prediction of graphyne (1987) to the large-scale synthesis of GDY (2010), a total of 17 related articles were published during this period. After the first large-scale synthesis of GDY, there has been an explosive growth in articles related to graphynes and GDYs [Figure 1B]. In 2023 alone, 382 articles on GDYs and 285 on graphynes were published, totaling 667. This phenomenon indicates the vigorous development and broad prospects of the research field of graphynes. In fact, graphynes also have various allotropes, including α-, β-, γ-, 6,6,12-graphyne, β- and γ-graphdiyne [Figure 1C-H]. The following text will abbreviate

Figure 1. (A) The structural units of graphynes. (B) Trends in articles related to graphyne and graphdiyne, which was obtained from the Web of Science. Molecular structure of (C) α-graphyne, (D) β-graphyne, (E) γ-graphyne, (F) 6,6,12-graphyne, (G) β-graphdiyne, (H) γ-graphdiyne.

Among various graphynes, researches on GDY (including theoretical calculations and experiments) are the most extensive. Similar to graphene, the structure of single-layer GDY remains stable through undulating ripple structures [Figure 2A]. Due to the presence of various conjugation effects, the C–C bond length in GDY is slightly different from that in acetylene. As shown in Figure 2B, after structure optimization, the alkyne bond length in GDY is 1.23 Å. Most of synthesized GDY are multi-layered structures. There are three potential stacking modes, and corresponding selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of these stacking modes are shown in Figure 2C-E[30]. They synthesized GDY nanosheets (thickness: 24 nm) and observed its structure through TEM [Figure 2F]. The SAED showed a hexagonal pattern, which was consistent with ABC stacking mode [Figure 2G]. Li et al. synthesized 6-layer GDY (2.19 nm) and studied its interlayer stacking mode[31]. They directly observed the molecular-level images of 6-layer GDY nanosheets utilizing a low-voltage transmission electron microscopy (TEM) device. More importantly, by comparing experimental SAED with simulated SAED, they also confirmed that GDY nanosheets have an ABC interlayer stacking mode. In fact, multi-layer GDY is in the ABC stacking mode, and this staggered structure is more conducive to the stability of the structure.

Figure 2. (A) Molecular model of two-dimensional GDY; (B) C–C bond length in GDY; (C-E) Left: three models of interlayer molecular stacking of GDY. Right: SAED; (F) TEM image of GDY nanosheets; (G) SAED pattern of GDY from experiments, and numerical values denote Miller indices. This figure is used with permission from Matsuoka et al.[30]. GDY: Graphdiyne; SAED: selected-area electron diffraction patterns.

The alkyne bonds of GDY endows itself with unique electronic, mechanical, optical, and magnetic properties. As depicted in Figure 3A, the single-layer GDY exhibits a planar structure with high symmetry[32]. The calculation results indicate that GDY has a direct bandgap of ~0.46 eV at the Г point [Figure 3B]. The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and LUMO+1 wave functions of GDY are shown in Figure 3C. LUMO+1 is the higher-order orbital above LUMO. In addition, Zheng et al. also proposed that the light absorption of double-layer and three-layer GDY can be adjusted via applying introducing an electric field[32]. Yue et al. studied the mechanical and electronic structure of GDY under applied strain via first-principles calculations [Figure 3D], and the results showed that the bandgap of GDY and their family could be changed via applying strain through various methods[33]. Specifically, uniform tensile strain leads to an increase in the bandgap of GDY, while uniform compressive strain, uniaxial tensile and compressive strain within the applied range all lead to a decrease in the band gap [Figure 3E and F]. Luo et al. measured the absorbance of GDY thin films in the near-infrared to ultraviolet energy range

Figure 3. (A) Unit cell and reciprocal space structure of monolayer GDY; (B) Band structure of GDY obtained from DFT; (C) LUMO and LUMO+1 wavefunctions of GDY. This figure is used with permission from Zheng et al.[32]; (D) Molecular models of graphynes (yellow area represents single-cell structure); The variation curve of bandgap with strain value obtained from (E) GGA-PBE and (F) HSE06 calculations. This figure is used with permission from Yue et al.[33]; (G) Experimental absorption and fitting curve of GDY; (H) Experimental absorption of GDY and curves calculated by two methods; (I) Magnetic moment of transition metal/graphyne and transition metal/GDY composite systems. This figure is used with permission from Luo et al.[34]. GDY: Graphdiyne; DFT: density functional theory; LUMO: lowest unoccupied molecular orbital.

The intrinsic properties of two-dimensional materials can be effectively explored through the density functional theory (DFT) calculations, and this approach can also be applied to GDY materials[35]. The DFT can be used to study the mechanical properties, thermal conductivity, energy band structure, etc. of GDY, which can be more targeted to the appropriate fields. For example, light absorption properties can be used for photocatalytic decomposition of water. In addition, the combination of advanced artificial intelligence techniques such as machine learning is used to examine the piezoelectric properties of complex structures in GDY materials, further expanding the application of GDY in fields such as nano-electronics and optoelectronics. And the selection of different methods (e.g., partial differential equations) for mathematical modeling based on different scientific and engineering problems is a key step in this technology[36].

SYNTHESIS METHOD OF GDY

GDY is a carbon material synthesized through artificial chemistry. The initial synthesis strategy is to use copper foil as templates and undergo cross-coupling reactions on their surfaces. The Cu sheet not only serves as templates for hexaethynylbenzene reaction, but also as a source of copper ion catalysts. With the continuous development of synthesis technology, more and more simple synthesis methods have emerged after this groundbreaking work was reported[13], expanding the application scope of GDY such as energy, electronic devices, biomedicine, and environmental remediation etc. In the next chapter, we will concentrate on the synthetic strategy of GDY and inspire new idea for the perparetion of GDY-based nanomaterials.

Synthesis method of pristine GDY

The acetylene bond formed by sp-hybridization possess many merits: linear π-π conjugation structure, absence of cis/trans isomers, and has received widespread attention. Li et al. began exploring the synthesis chemistry of planar carbon in the mid-1990s[13]. However, when synthesizing up to a dozen carbon atoms, the synthesis process was difficult to control due to the high surface tension. Subsequently, they continued to explore methods such as high-temperature solid-phase synthesis, interfacial growth of two-phase and multiphase, and found that these methods were difficult to avoid the problem of complex and difficult to separate products. After six years of arduous exploration, a new carbon allotrope with a two-dimensional structure was successfully synthesized and named “Graphdiyne” in China for the first time[13].

The synthetic route of GDY as can be seen from in Figure 4A. In short, the monomer of hexaethynylbenzene can be prepared by addition of tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) to tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution of hexakis[(trimethylsilyl)ethynyl]benzene (HEB). The GDY grown on Cu sheet by a C-C cross-coupling reaction. This synthesis strategy can obtain large-area GDY thin films of

Figure 4. (A) Reaction equation for synthesizing GDY; (B) The photograph of GDY films (3.61 cm2); (C) The SEM images of GDY at different magnifications; (D) Raman spectra of GDY films. This figure is used with permission from Li et al.[13]. GDY: Graphdiyne; SEM: scanning electron microscopy.

With the demand of application scenarios and innovation in synthesis technology, GDY can be synthesized on various substrates and even on any substrate as reported. For example, super-thin GDY films were synthesized on Cu nanowires to effectively enhance the surface affinity with lithium [Figure 5A][37]. GDY nanofilms can completely encapsulate Cu nanowires, resulting in a wider diameter than that of the pristine Cu nanowires. Pan et al. successfully synthesized GDY nanowalls by wrapping carbon cloth with copper foil [Figure 5B][38]. The GDY fabricated by this approach grew evenly on nanofibers and presents a three-dimensional structure (thickness: approximately 20 nm). Hui et al. improved the synthetic method based on the original synthesis and synthesized layered GDY on Ni foam [Figure 5C][39]. The intensity ratio of D and G-bands synthesized by this synthesis strategy is 0.88, significantly improving the synthesis quality of GDY. The methods for constructing GDY on Mxene [Figure 5D][40] and 3D melamine sponge [Figure 5E][41] are similar. The former uses CuCl as a catalyst, while the latter uses Cu ions released by copper foil under heating conditions containing pyridine solution as a catalyst. However, the GDY synthesized by the latter has high crystallinity and a thin thickness of only 10 nm. The preparation of low-dimensional GDY nanomaterials is of great significance in the field of electronic devices. Li et al. synthesized GDY/Aluminum oxide composite materials for the first time and obtained GDY nanotubes through etching by NaOH

Figure 5. (A) Synthetic route of preparation of GDY/Cu nanowires. This figure is used with permission from Shang et al.[37]; (B) The synthetic process of GDY/carbon cloth. This figure is used with permission from Pan et al.[38]; (C) Optical photographs of pure Ni foam and GDY/Ni foam. This figure is used with permission from Hui et al.[39]; (D) The preparation process of Ti3C2Tx@GDY heterojunction nanocomposites. This figure is used with permission from zhou et al.[40]; (E) Synthetic route of the preparation of GDY/MS. This figure is used with permission from Fu et al.[41]; (F) Abridged general view of preparation of GDY/Aluminum oxide arrays. This figure is used with permission from Li et al.[42]; (G) Diagrammatic sketch of growth of GDY on ZnO nanorod arrays. This figure is used with permission from Qian et al.[43]. GDY: Graphdiyne; MS: melamine sponge.

The above synthesis strategy requires a small amount of GDY monomer and a relatively low degree of GDY defects. In short, the synthesis of GDY from copper foil to any substrate greatly expands the application range of GDY nanomaterials in various fields.

Interface limited synthesis of GDY

GDY is usually synthesized by C-C coupling of HEB monomers under Cu catalytic conditions. Interface limited synthesis of GDY involves separating HEB monomer and Cu catalyst, and only reacting at interfaces (including gas-liquid, liquid-liquid, solid-liquid interfaces, and solid crystal planes). Through this method, the synthesized GDY usually has a thin thickness (sub nanometer to tens of nanometers) and good quality.

In 2017, Matsuoka et al. first put forward a strategy to synthesize GDY using gas-liquid or liquid-liquid interfaces[30]. As shown in Figure 6A and B, they first performed liquid-liquid interface synthesis: Cu catalyst was dissolved in water, while HEB was dissolved in organic phase (CH2Cl2), and a water layer was introduced in the middle to grow up a concentration gradient. The thickness of GDY synthesized by this method is 24 nm, and GDY has ABC stacking mode. Subsequently, they further improved the method by adding a very small amount of HEB monomer solution dropwise to the aqueous solution of Cu2+, and successfully synthesized GDY with a thickness of only 3 nm on the gas-liquid surface. Li et al. achieved the synthesis of large-area uniform GDY thin films through gas-liquid interface method and used them for rewritable memory resistors[45]. GDY thin film (~7 nm) exhibits stable non-volatile resistance switching performance, exceptional data retention (4,103 s), and eminent on/off ratio (~103)[45]. Inspired by the liquid-liquid/gas-liquid interface method, Zhang et al. added surfactants (hexadecyl trimethylammonium bromide, CTAB) into the above system to form microemulsion and successfully synthesized GDY hollow nanospheres, as shown in Figure 6C[46].

In 2008, Gao et al. prepared single-crystal GDY thin sheets on single-layer graphene via a solution strategy

Figure 6. (A) Diagrammatic sketch and (B) corresponding liquid-liquid interface synthesis experiment. This figure is used with permission from Matsuoka et al.[30]; (C) SEM pictures of growth mechanism and schematic diagram of the formation mechanism of GDY hollow spheres. This figure is used with permission from Zhang et al.[46]; (D) Schematic illustration of solution vans der Waals epitaxy strategy. This figure is used with permission from Gao et al.[47]; (E) Abridged general view of synthesis steps of GDY grown on graphene. This figure is used with permission from Zhou et al.[48]. GDY: Graphdiyne; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; HEB: hexaethylbenzene.

In 2024, Li et al. proposed a solid lattice confined GDY growth strategy: single-layer GDY was prepared in the sub-nanometer space between two-dimensional MXene layers[50]. This measurement can effectively prevent the accumulation and coupling of HEB monomers in the vertical direction. GDY grew between the lattices of the Mxene. The conductivity of the single-layer GDY measured at room temperature is 5.1 ×

On-surface synthesis in CVD/STM system

In 2017, Liu et al. first used HEB monomer to grow GDY thin films on Si substrates by CVD method under low temperature of 150 degrees and Ag coating conditions[51]. During the growth process, under thermal activation and substrate catalysis, HEB monomers diffused and adsorbed onto the substrate. Subsequently, the Csp–H bonds were cleaved to form H2, while the covalent C-C linkage of alkyl groups underwent coupling reactions.

In 2013, Zhang et al. achieved the activation and homo-coupling process of Csp–H bonds at the end alkyne on the Ag (111) surface through direct visualization operations in real space[52]. They selected two types of terminal alkyne organic molecules (TEB and Ext-TEB). Under ultra-high vacuum conditions and without traditional transition metal catalysts, both molecules underwent coupling reactions. Gao et al. studied the role of metal Au, Ag, Cu substrate in the coupling reaction of 1,4-diethynylbenenzene and the mechanism of this process[53]. Compared to Au (111), Ag (111) provides a lower proportion of side reactions, making them the most suitable for surface laser coupling of alkynyl aromatic hydrocarbons. Cirera et al. studied reactions of linear alkyne along the step edge of Ag (877) adjacent surface under ultra-high vacuum conditions using a scanning tunneling microscope (STM)[54]. And they successfully controlled the synthesis of extended GDY wires with a length of up to 30 nm. Sun et al. introduced a dehalogenation homo-coupling reaction on the surface of a molecular precursor with terminal alkynyl bromide[55]. The dimer structure, one-dimensional molecular lines [Figure 7A and B], and two-dimensional molecular network [Figure 7C and D] were successfully formed on the Au (111). In addition, the C-Au-C organic metal structures were detected.

Figure 7. (A) STM diagram of molecular structure connected by acetylene bond and (B) STM magnification image; (C) Large-scale and (D) magnification STM images of molecular network constructed by acetylene bonds. This figure is used with permission from Sun et al.[55]. STM: Scanning tunneling microscope.

Synthesis of GDY by explosion method

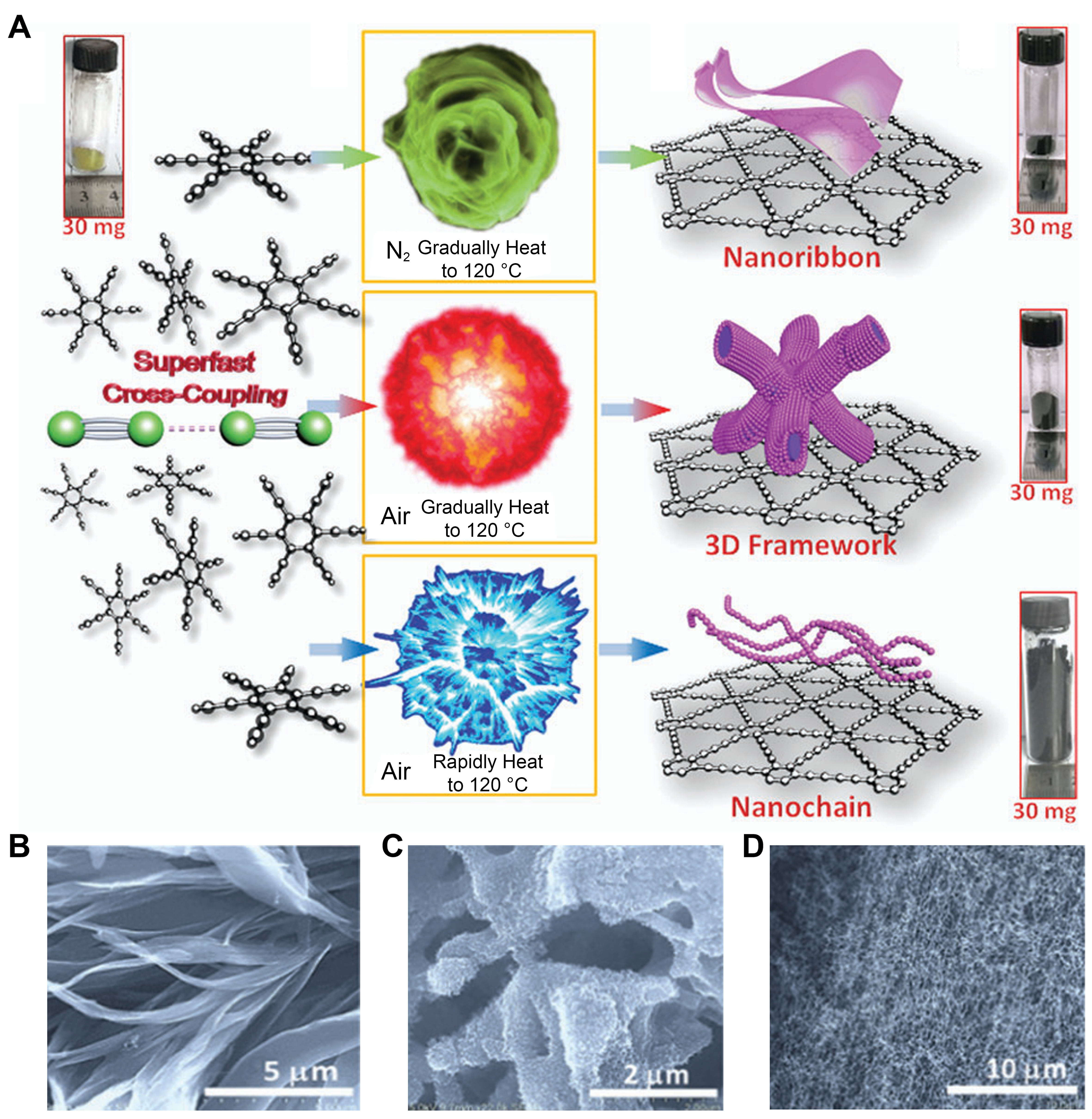

The large-scale and low-cost preparation of GDY is a gap that limits its practical application. For the reason that achieving brief macroscopic synthesis of GDY, Zuo et al. put forward a novel method to prepare GDY[56], as shown in Figure 8A. Under a given nitrogen or air atmosphere, HEB is simply heated and a C-C coupling can occur to prepare GDY, which do not need catalysts. The prepared GDY shows vital merits in conductivity (20 S·m-1), surface area (1,150 m2·g-1), etc. It is worth noting that it does not require the addition of any catalyst, effectively reducing the synthesis expenditure. Meanwhile, controllable preparation can be readily achieved by regulating parameters such as temperature during the heat treatment process. For example, the GDY nanoribbons [Figure 8B] prepared were aggregated into flower shaped secondary structures in N2 gas. The length of the nano-belt is ~20 mm and the thickness is ~100 nm. When air is used instead of N2, GDY nanowires can grow uniformly on 3D networks [Figure 8C], providing a particular three-dimensional transfer passageway structure for electrons. When precursors were added to the preheated reactor, an intense explosion produces oriented growth of nano chains [Figure 8D]. These nanochains have excellent 3D continuity, approximately 20 nm. But, compared to GDY synthesized via interface limited and on-surface synthesis in CVD/STM system strategy, the GDY prepared though this strategy has inferior crystallinity.

Figure 8. (A) Illustrations of the preparation processes. SEM pictures of (B) GDY nanoribbons, (C) 3D frameworks and (D) nano-chain. This figure is used with permission from Zuo et al.[56]. SEM: Scanning electron microscopy; GDY: graphdiyne.

Synthesis of GDY derivatives

The structure of GDY is easy to control, making it have good structural adjustability, which facilitates the introduction of various heteroatoms to form derivatives. In recent years, a series of GDY derivatives have been designed and developed. The following mainly summarizes the synthesis of GDY derivatives by doping heteroatoms (N, Cl, F, B, P, S, etc.), including monomer molecule design and introducing other heteroatom sources and hydrogen-substituted GDY (HsGDY).

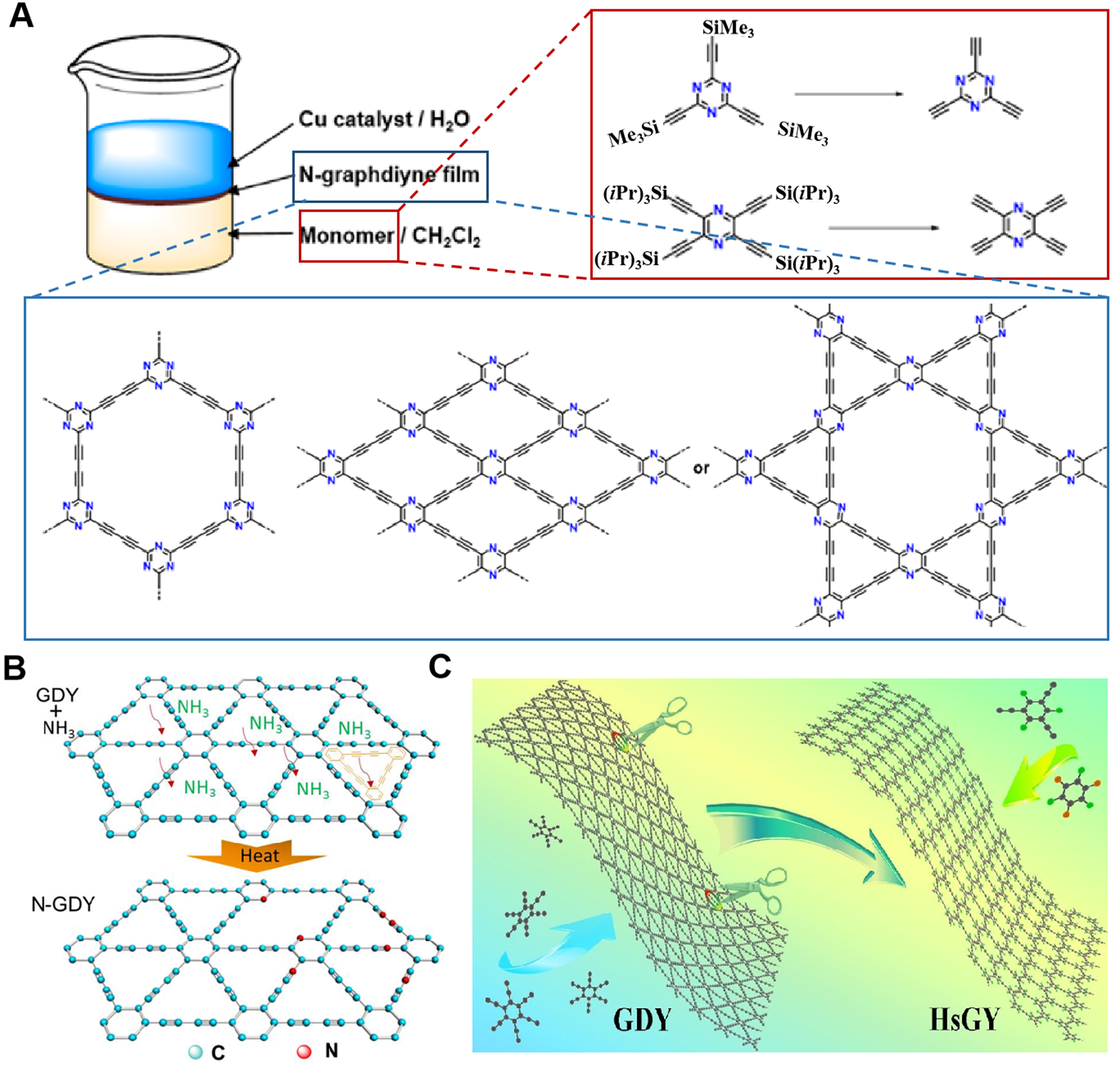

Kan et al. utilized triazine-or pyrazine-based precursors consisting of ethynyl group to obtain conjugated 2D N-GDY at interfaces[57]. As shown in Figure 9A, nitrogen-containing GDY with three different molecular and pore structures was prepared. The advantage of this method is that the constructed GDY is of high quality and has a large-area sheet-like structure with a thickness of about 20 nm. In addition, the N doping sites in the nitrogen-containing GDY constructed by this synthesis strategy are precise. Zhang et al. also reported a synthesis method of incorporating nitrogen elements into GDY [Figure 9B][58]. Firstly, GDY thin films are obtained on copper foil, and then nitrogen-doped GDY can be obtained by calcination at

HsGDY was successfully synthesized by tailoring the butadiyne linkers[64]. In short, tribromobenzene is employed to synthesize triethylbenzene, which serves as a monomer for the coupling reaction to construct HsGDY [Figure 9C]. The as-prepared HsGDY exhibits larger micropore density, well crystallinity and a large number of C-H bonds. Besides, it exhibits a porous and continuous morphology. The thickness of HsGDY films is about 3.6 µm. The spacing between the two-dimensional carbon layers is 0.419 nm. The HsGDY (16.3 Å) has a larger pore structure than GDY (5 Å), which will exhibit physical and chemical properties different from GDY[65]. The doping of elements can not only enhance the surface chemical activity of nano GDY, but also regulate its electronic structure, significantly improving the photoelectric properties, energy storage and conversion efficiency, and catalytic performance of GDY[66-68]. The doping of elements can not only enhance the surface chemical activity of nano GDY, but also regulate its electronic structure, significantly improving the photoelectric properties, energy storage and conversion efficiency, and catalytic performance of GDY.

Figure 9. (A) Abridged general view of N-GDY synthesis processes. This figure is used with permission from Kan et al.[57]; (B) Diagrammatic sketch of N doping process of GDY. This figure is used with permission from Zhang et al.[58]; (C) Molecular model of adjusting alkyne bonds of GDY to prepare HsGDY. This figure is used with permission from Ren et al.[64]. GDY: Graphdiyne; HsGDY: hydrogen-substituted graphdiyne.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

Since the first large-scale synthesis of GDY materials in 2010, the synthesis methods and research enthusiasm have shown an exponential explosive growth trend. Researchers synthesized single-layer and few-layer GDY single crystals, and systematically studied the stacking mode, electronic structure, optical absorption, magnetism, and other properties of GDY combined with theoretical calculations. From the perspective of synthesis methods, traditional liquid-phase synthesis can achieve large-area synthesis of GDY on any substrate, but there are also shortcomings such as harsh conditions and long reaction times; GDY synthesized by interface confinement method usually has a thin thickness (several to tens of nanometers), but there are still problems with large-area synthesis; The synthesis time of explosion method is relatively short, but the quality of GDY is not as good as other methods; the surface synthesis method can accurately control coupling frequency of HEB and atomic scale microstructure, making it more suitable for studying the mechanism of C-C coupling.

GDY possesses unique properties, including light absorption, electrical conductivity, magnetism, and semiconductivity, which have made it widely used in optical devices, electrocatalysis, thermal catalysis, environmental engineering, and other fields. However, several factors still limit its practical application:

(1) High-cost synthesis: Palladium, a commonly used catalyst for GDY synthesis, is expensive, increasing production costs and hindering large-scale preparation. Additionally, catalyst recovery and reuse face technical challenges, further raising costs. Developing alternative non-precious metal catalysts is urgently needed.

(2) Challenges in synthesis control: The GDY synthesis process involves complex chemical reactions and crystal growth mechanisms that are difficult to precisely regulate, leading to inconsistencies in product quality during large-scale production. Key issues include:

· Single-bond free rotation: The single bond between the benzene ring and alkyne bond in GDY monomers can rotate freely, affecting the structural orderliness of the final product.

· Lattice matching: Specific lattice matching between the substrate surface and GDY is required; otherwise, the orderliness and quality of the GDY film are compromised.

· Monomer aggregation and nucleation: Uncontrolled aggregation and nucleation of monomers on the substrate surface can reduce the orderliness of GDY films.

(3) Structural defects: During synthesis, defects such as vacancies, dislocations, and oxidation may occur, adversely affecting GDY’s physical and chemical properties.

Despite these challenges, GDY offers significant advantages: Its excellent carrier mobility enhances device operating speed and reduces energy consumption, while its unique 2D structure enables miniaturization and improved chip performance. Additionally, GDY’s optical and mechanical properties make it suitable for high-performance sensors, advancing AI devices toward high performance and miniaturization.

Addressing the aforementioned limitations is critical to achieving the large-scale industrial application of GDY.

The preparation and application of GDY are complementary. With the increasing application of GDY in more fields, higher requirements have been put forward for the synthesis methods of GDY. Advanced GDY synthesis methods should have the following characteristics: short reaction time, mild reaction conditions, easy large-scale preparation, no substrate limitations, and high GDY quality. The continuous innovation of GDY synthesis methods will undoubtedly lead to the application of GDY in more research areas and make further contributions to human society.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Manuscript preparation: Pan, C.; Yao, Y.

Manuscript revision: Pan, C.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, B.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

Pan, C. acknowledges the High-level Talent Research Launch Fund of Henan University of Technology (2024BS061) and the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (252300421710).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Malko, D.; Neiss, C.; Viñes, F.; Görling, A. Competition for graphene: graphynes with direction-dependent Dirac cones. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 086804.

2. Ocsoy, I.; Paret, M. L.; Ocsoy, M. A.; et al. Nanotechnology in plant disease management: DNA-directed silver nanoparticles on graphene oxide as an antibacterial against Xanthomonas perforans. ACS. Nano. 2013, 7, 8972-80.

3. Gong, K.; Du, F.; Xia, Z.; Durstock, M.; Dai, L. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube arrays with high electrocatalytic activity for oxygen reduction. Science 2009, 323, 760-4.

4. Allen, M. J.; Tung, V. C.; Kaner, R. B. Honeycomb carbon: a review of graphene. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 132-45.

5. Cao, N.; Zhang, N.; Wang, K.; Yan, K.; Xie, P. High-throughput screening of B/N-doped graphene supported single-atom catalysts for nitrogen reduction reaction. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 23.

6. Yi, C.; Liu, Z. Co single atoms/nanoparticles over carbon nanotubes for synergistic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. Chem. Synth. 2024, 4, 67.

7. Wassei, J. K.; Kaner, R. B. Oh, the places you’ll go with graphene. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2244-53.

9. Choi, W.; Lahiri, I.; Seelaboyina, R.; Kang, Y. S. Synthesis of graphene and its applications: a review. Crit. Rev. Solid. State. Mater. Sci. 2010, 35, 52-71.

10. Fang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Graphdiyne interface engineering: highly active and selective ammonia synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 13021-7.

11. Wang, F.; Zuo, Z.; Li, L.; et al. Large-area aminated-graphdiyne thin films for direct methanol fuel cells. Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 15152-7.

12. Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, H.; Li, Y. Graphdiyne and graphyne: from theoretical predictions to practical construction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 2572-86.

13. Li, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, D. Architecture of graphdiyne nanoscale films. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3256-8.

14. Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, J. Metal-free graphdiyne doped with sp-hybridized boron and nitrogen atoms at acetylenic sites for high-efficiency electroreduction of CO2 to CH4 and C2H4. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 4026-35.

15. Li, J.; Zhong, L.; Tong, L.; et al. Atomic Pd on graphdiyne/graphene heterostructure as efficient catalyst for aromatic nitroreduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1905423.

16. Xue, Y.; Huang, B.; Yi, Y.; et al. Anchoring zero valence single atoms of nickel and iron on graphdiyne for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1460.

17. Hui, L.; Xue, Y.; Yu, H.; et al. Highly efficient and selective generation of ammonia and hydrogen on a graphdiyne-based catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10677-83.

18. Gao, Y.; Cai, Z.; Wu, X.; Lv, Z.; Wu, P.; Cai, C. Graphdiyne-supported single-atom-sized Fe catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction: DFT predictions and experimental validations. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 10364-74.

19. He, J.; Ma, S. Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, C. X.; He, C.; Sun, L. Z. Magnetic properties of single transition-metal atom absorbed graphdiyne and graphyne sheet from DFT+U calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012, 116, 26313-21.

20. Pan, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; et al. Neighboring sp-hybridized carbon participated molecular oxygen activation on the interface of sub-nanocluster CuO/graphdiyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 4942-51.

21. Dong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Graphdiyne-hybridized N-doped TiO2 nanosheets for enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 8921-32.

22. Zuo, Z.; Li, Y. Emerging electrochemical energy applications of graphdiyne. Joule 2019, 3, 899-903.

23. Yang, Z.; Shen, X.; Wang, N.; et al. Graphdiyne containing atomically precise N atoms for efficient anchoring of lithium ion. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 2608-17.

24. Pan, C.; He, Q.; Li, C. Promising graphdiyne-based nanomaterials for environmental pollutant control. Sci. China. Mater. 2024, 67, 3456-67.

25. Xue, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y. 2D graphdiyne materials: challenges and opportunities in energy field. Sci. China. Chem. 2018, 61, 765-86.

26. Gao, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J. Graphdiyne: synthesis, properties, and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 908-36.

27. Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; et al. Progress in research into 2D graphdiyne-based materials. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 7744-803.

28. Baughman, R. H.; Eckhardt, H.; Kertesz, M. Structure-property predictions for new planar forms of carbon: layered phases containing sp 2 and sp atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 87, 6687-99.

29. Haley, M. M.; Brand, S. C.; Pak, J. J. Carbon networks based on dehydrobenzoannulenes: synthesis of graphdiyne substructures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 836-8.

30. Matsuoka, R.; Sakamoto, R.; Hoshiko, K.; et al. Crystalline graphdiyne nanosheets produced at a gas/liquid or liquid/liquid interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3145-52.

31. Li, C.; Lu, X.; Han, Y.; et al. Direct imaging and determination of the crystal structure of six-layered graphdiyne. Nano. Res. 2018, 11, 1714-21.

32. Zheng, Q.; Luo, G.; Liu, Q.; et al. Structural and electronic properties of bilayer and trilayer graphdiyne. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 3990-6.

33. Yue, Q.; Chang, S.; Kang, J.; Qin, S.; Li, J. Mechanical and electronic properties of graphyne and its family under elastic strain: theoretical predictions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013, 117, 14804-11.

34. Luo, G.; Qian, X.; Liu, H.; et al. Quasiparticle energies and excitonic effects of the two-dimensional carbon allotrope graphdiyne: theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. B. 2011, 84, 075439.

35. Samaniego, E.; Anitescu, C.; Goswami, S.; et al. An energy approach to the solution of partial differential equations in computational mechanics via machine learning: concepts, implementation and applications. Comput. Methods. Appl. Mech. Eng. 2020, 362, 112790.

36. Mortazavi, B.; Javvaji, B.; Shojaei, F.; Rabczuk, T.; Shapeev, A. V.; Zhuang, X. Exceptional piezoelectricity, high thermal conductivity and stiffness and promising photocatalysis in two-dimensional MoSi2N4 family confirmed by first-principles. Nano. Energy. 2021, 82, 105716.

37. Shang, H.; Zuo, Z.; Li, Y. Highly lithiophilic graphdiyne nanofilm on 3D free-standing Cu nanowires for high-energy-density electrodes. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 17678-85.

38. Pan, C.; Zhang, B.; Pan, T.; et al. Insights into efficient bacterial inactivation over nano Ag/graphdiyne: dual activation of molecular oxygen and water molecules. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2023, 10, 3072-83.

39. Hui, L.; Jia, D.; Yu, H.; Xue, Y.; Li, Y. Ultrathin graphdiyne-wrapped iron carbonate hydroxide nanosheets toward efficient water splitting. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 2618-25.

40. Zhou, Q.; Dong, H.; Liu, L.; et al. In-situ surface growth strategy to synthesize MXene@graphdiyne heterostructure for achieving high capacity and desirable stability in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2024, 603, 234404.

41. Fu, X.; He, F.; Gao, J.; et al. Directly growing graphdiyne nanoarray cathode to integrate an intelligent solid Mg-moisture battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 2759-64.

42. Li, G.; Li, Y.; Qian, X.; et al. Construction of tubular molecule aggregations of graphdiyne for highly efficient field emission. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011, 115, 2611-5.

43. Qian, X.; Liu, H.; Huang, C.; et al. Self-catalyzed growth of large-area nanofilms of two-dimensional carbon. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7756.

44. Gao, X.; Li, J.; Du, R.; et al. Direct synthesis of graphdiyne nanowalls on arbitrary substrates and its application for photoelectrochemical water splitting cell. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605308.

45. Li, W.; Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; et al. Synthesis of large-area ultrathin graphdiyne films at an air-water interface and their application in memristors. Mater. Chem. Front. 2020, 4, 1268-73.

46. Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Yi, W.; Wei, G.; Yin, M.; Xi, G. Synthesis of graphdiyne hollow spheres and multiwalled nanotubes and applications in water purification and Raman sensing. Nano. Lett. 2023, 23, 3023-9.

47. Gao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yi, D.; et al. Ultrathin graphdiyne film on graphene through solution-phase van der Waals epitaxy. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat6378.

48. Zhou, J.; Xie, Z.; Liu, R.; et al. Synthesis of ultrathin graphdiyne film using a surface template. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 2632-7.

49. Kong, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Rapid synthesis of graphdiyne films on hydrogel at the superspreading interface for antibacteria. ACS. Nano. 2022, 16, 11338-45.

50. Li, J.; Cao, H.; Wang, Q.; et al. Space-confined synthesis of monolayer graphdiyne in MXene interlayer. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2308429.

51. Liu, R.; Gao, X.; Zhou, J.; et al. Chemical vapor deposition growth of linked carbon monolayers with acetylenic scaffoldings on silver foil. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, e2308429.

52. Zhang, Y. Q.; Kepčija, N.; Kleinschrodt, M.; et al. Homo-coupling of terminal alkynes on a noble metal surface. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1286.

53. Gao, H.; Franke, J.; Wagner, H.; et al. Effect of metal surfaces in on-surface glaser coupling. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013, 117, 18595-602.

54. Cirera, B.; Zhang, Y. Q.; Björk, J.; et al. Synthesis of extended graphdiyne wires by vicinal surface templating. Nano. Lett. 2014, 14, 1891-7.

55. Sun, Q.; Cai, L.; Ma, H.; Yuan, C.; Xu, W. Dehalogenative homocoupling of terminal alkynyl bromides on Au(111): incorporation of acetylenic scaffolding into surface nanostructures. ACS. Nano. 2016, 10, 7023-30.

56. Zuo, Z.; Shang, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. A facile approach for graphdiyne preparation under atmosphere for an advanced battery anode. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 8074-7.

57. Kan, X.; Ban, Y.; Wu, C.; et al. Interfacial synthesis of conjugated two-dimensional N-graphdiyne. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018, 10, 53-8.

58. Zhang, S.; Du, H.; He, J.; et al. Nitrogen-doped graphdiyne applied for lithium-ion storage. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016, 8, 8467-73.

59. He, J.; Wang, N.; Yang, Z.; et al. Fluoride graphdiyne as a free-standing electrode displaying ultra-stable and extraordinary high Li storage performance. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 2893-903.

60. Wang, N.; Li, X.; Tu, Z.; et al. Synthesis and electronic structure of boron-graphdiyne with an sp-hybridized carbon skeleton and its application in sodium storage. Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 4032-7.

61. Wang, N.; He, J.; Tu, Z.; et al. Synthesis of chlorine-substituted graphdiyne and applications for lithium-ion storage. Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 10880-5.

62. Zhao, Y.; Yang, N.; Yao, H.; et al. Stereodefined codoping of sp-N and S atoms in few-layer graphdiyne for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7240-4.

63. Shen, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, F.; et al. Preparation and structure study of phosphorus-doped porous graphdiyne and its efficient lithium storage application. 2D. Mater. 2019, 6, 035020.

64. Ren, X.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; et al. Tailoring acetylenic bonds in graphdiyne for advanced lithium storage. ACS. Sustainable. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 2614-21.

65. He, J.; Wang, N.; Cui, Z.; et al. Hydrogen substituted graphdiyne as carbon-rich flexible electrode for lithium and sodium ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1172.

66. Qi, L.; Gao, Y.; Gao, Y.; et al. Controlled growth of metal atom arrays on graphdiyne for seawater oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 5669-77.

67. Zheng, X.; Wu, H.; Gao, Y.; Chen, S.; Xue, Y.; Li, Y. Controllable assembly of highly oxidized cobalt on graphdiyne surface for efficient conversion of nitrogen into nitric acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202316723.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].