Toward low-carbon energy transitions: integrated optimization of solar panel output and safety using tracking and thermal management

Abstract

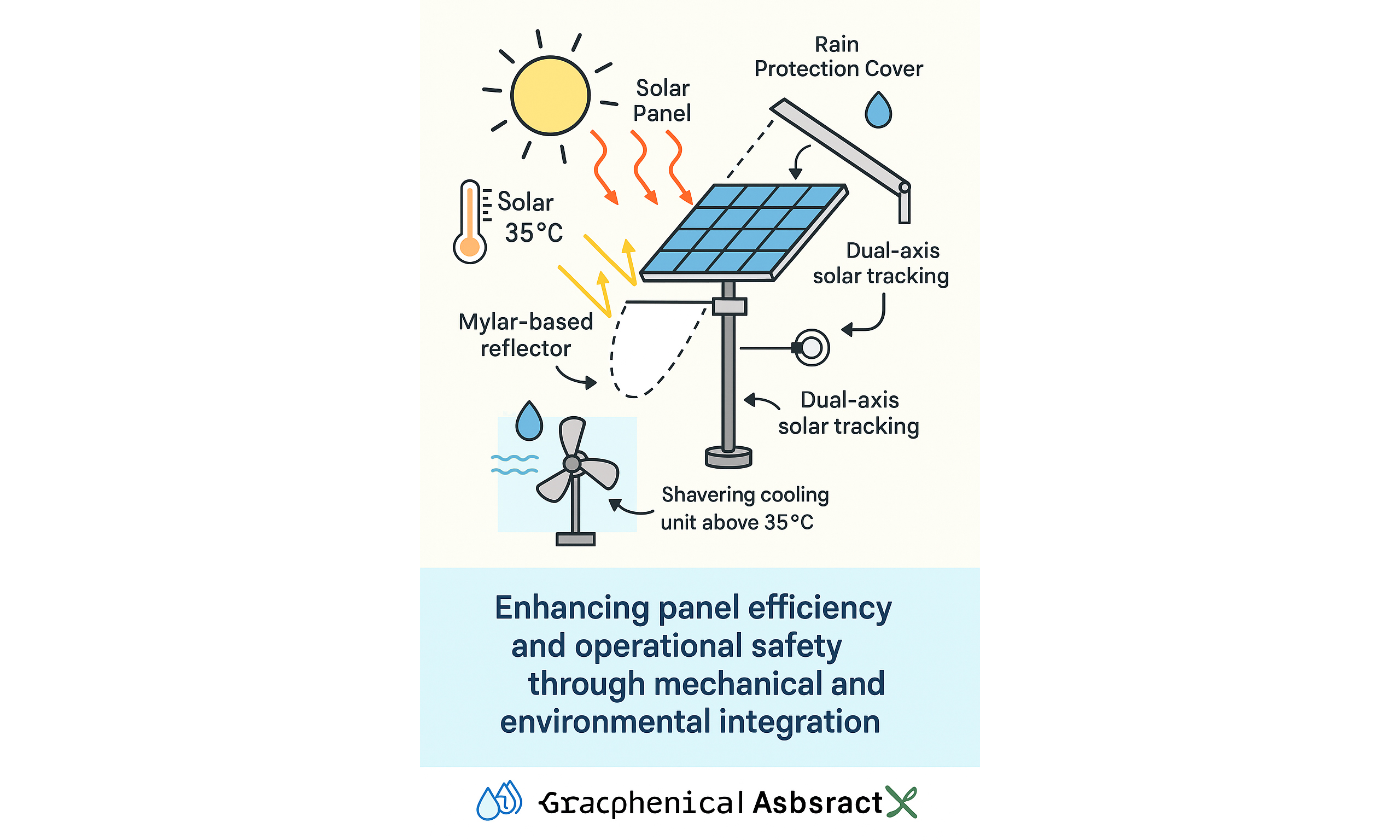

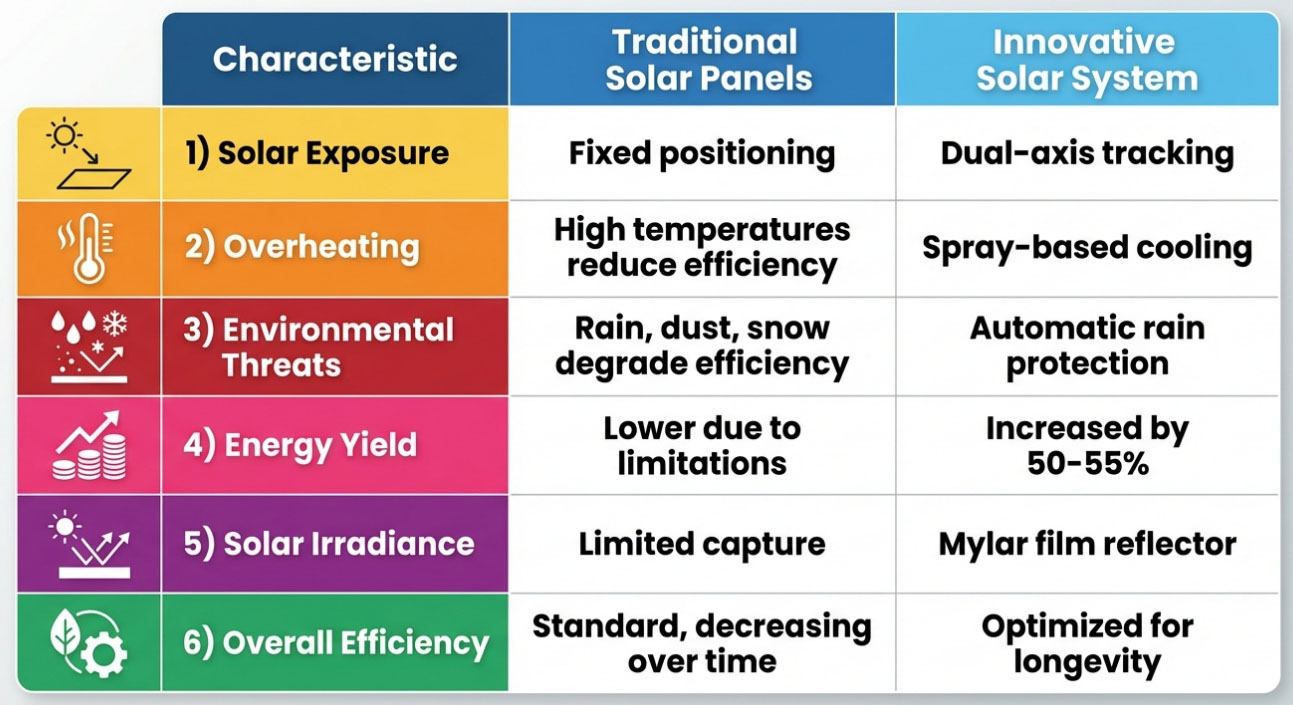

Solar photovoltaic (PV) systems face significant challenges, including low energy conversion efficiency, performance degradation due to overheating, and operational risks from environmental factors such as rainfall and dust. To address these issues, this study presents an innovative solar energy solution aimed at enhancing panel efficiency and operational reliability through mechanical and environmental integration. The system incorporates a Mylar-based reflector to boost solar irradiance, an automated rain protection cover activated by sensors, a dual-axis solar tracking system for continuous sun alignment, and a temperature-controlled cooling system that activates above 35 °C. Implemented on a 20W Mono PERC (Passivated Emitter Rear Cell) panel, the system was tested under real-world conditions. Results showed a cumulative efficiency improvement compared to a conventional fixed panel. The reflector and tracking system contributed most to output gains, while the rain cover and cooling system improved durability and thermal performance. Overall, the integrated system achieved 50%-55% higher energy production than the conventional fixed panel. These findings highlight a cost-effective approach to advance low-carbon energy transitions and promote renewable adoption in semi-arid urban areas.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

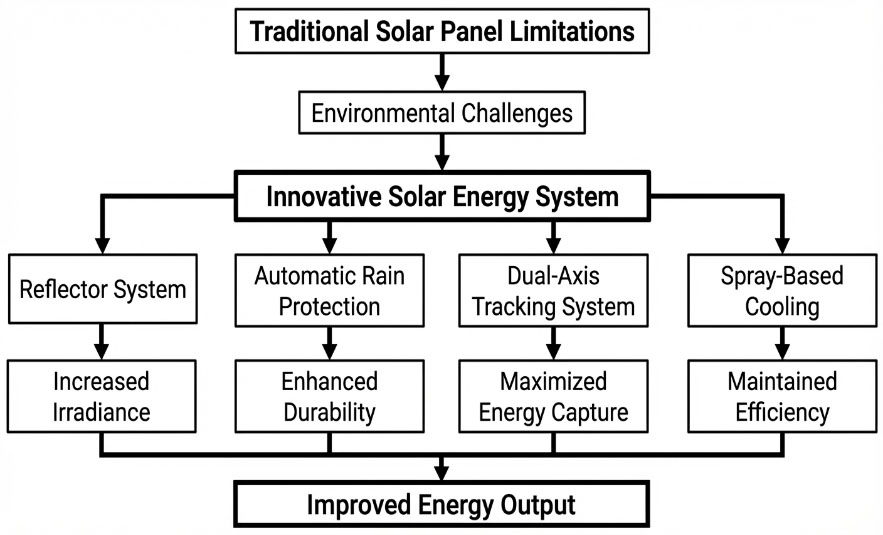

The performance of photovoltaic (PV) systems is strongly influenced by thermal effects, solar irradiance, and environmental conditions, which collectively limit electrical efficiency and long-term durability. Experimental studies have shown that excessive operating temperatures significantly reduce PV efficiency, motivating the integration of passive and active cooling strategies to mitigate thermal losses. For example, water-based cooling, ethylene glycol, and hybrid coolant combinations effectively reduce module temperature while improving energy output and environmental performance. Similarly, air-based cooling enhanced with aluminum fins and forced convection can improve electrical efficiency, although its effectiveness depends on ambient conditions and system configuration[1-3]. Beyond cooling, optical enhancement techniques such as reflectors and concentrators have attracted attention for increasing incident solar irradiance without enlarging panel area. Experiments indicate that the simultaneous application of reflectors and phase change materials (PCMs) can significantly enhance PV power output by improving irradiance capture while stabilizing module temperature[4,5]. Studies on concentrating solar systems further confirm that receiver geometry and thermal management are critical for maximizing energy conversion efficiency under high solar flux. Recent research also emphasizes the importance of intelligent system-level decision-making and optimization for renewable energy deployment. Multi-criteria decision-making frameworks combined with geographic information systems (GIS) and machine learning techniques have been widely used to optimize site selection and system performance for solar and wind projects. Additionally, fuzzy hybrid and data-driven approaches are promising tools for handling uncertainty and improving decision accuracy in PV systems[6,7]. Collectively, these studies highlight the necessity of integrated PV system designs that combine thermal regulation, optical enhancement, and intelligent decision-making to achieve higher efficiency, reliability, and sustainability[8,9]. Renewable energy adoption worldwide positions solar energy as a leading source for heating water and generating electricity[10]. The output power of PV systems depends on the amount of sunlight captured and the surrounding air temperature[11].

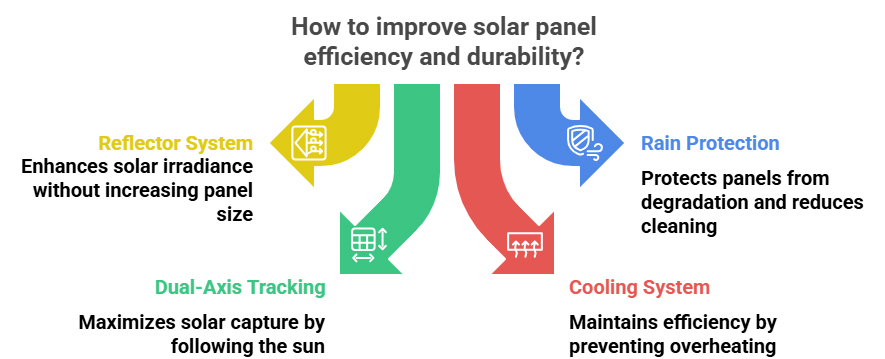

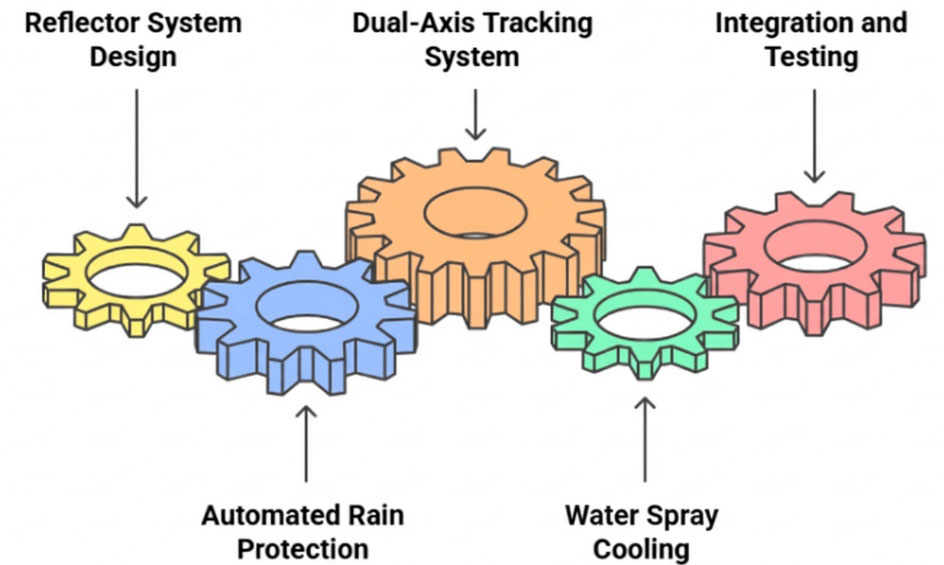

With varying climates in Pakistan, these challenges are more pronounced. Pakistan spans latitudes 24°-37° N and longitudes 61°-76° E, offering substantial potential for solar energy applications[12]. Given the high energy demand, renewable systems must be deployed to utilize these solar resources effectively. Currently, electricity does not reach more than 40,000 villages and remote areas across the country[12]. To address these issues, this article presents an innovative solar energy system integrating four key technologies designed to improve both energy yield and operational safety, as shown in Figure 1. Here, operational safety refers to aspects critical to the long-term, efficient functioning of the system, which we categorize into electrical, structural, fire, and maintenance-related concerns.

Since fixed solar panels are mounted at a single angle, they cannot fully utilize the sun’s energy throughout the day. Smart solar trackers - single-axis and dual-axis systems - allow panels to follow the sun and capture more energy. Before using trackers, panels are initially positioned to achieve optimal output. The single-axis system was first developed to track the sun’s daily movement. Later, the dual-axis system was introduced to follow both the daily sunrise and sunset as well as the sun’s seasonal movement across the sky. This enables the solar panel to operate at maximum capacity. Dual-axis trackers move the panel vertically and horizontally, ensuring it continuously faces the sun and maximizes daily energy capture.

By adding reflectors to a solar system, PV panels can operate more efficiently, resulting in higher energy yield[13]. Studies show that panels equipped with reflectors generally perform better and generate more electricity[14,15]. Mylar reflective material is placed around the panel’s edges to increase the light incident on the cells. Passive optical designs enhance photon capture, enabling additional power generation without increasing PV material or module size. Booster reflectors significantly increase the amount of sunlight reaching the PV surface. Snow or rain can cause dirt accumulation or water ingress, reducing panel performance. Smart features such as rain sensors and microcontrollers activate motorized covers or barriers to protect the panels during rainfall.

Using a solar tracker in a PV system allows the solar panel to follow the sun’s movement, helping maintain high power generation efficiency throughout the year[16]. Advanced dual-axis trackers and reflector systems can increase the temperature of solar panels. When PV panel temperatures exceed 35 °C, efficiency decreases due to higher internal resistance. To address this, active cooling, such as water spraying, is employed to remove heat. Temperature sensors monitor the panel, and water sprinklers activate only when the temperature exceeds a set threshold. This approach keeps the panels cooler, maintaining optimal efficiency during peak sunlight. The choice of reflector material depends on the location, as some materials perform better under low temperatures than high ones[17,18]. Since PV module output is highly sensitive to temperature, monitoring and managing panel surface temperature is essential.

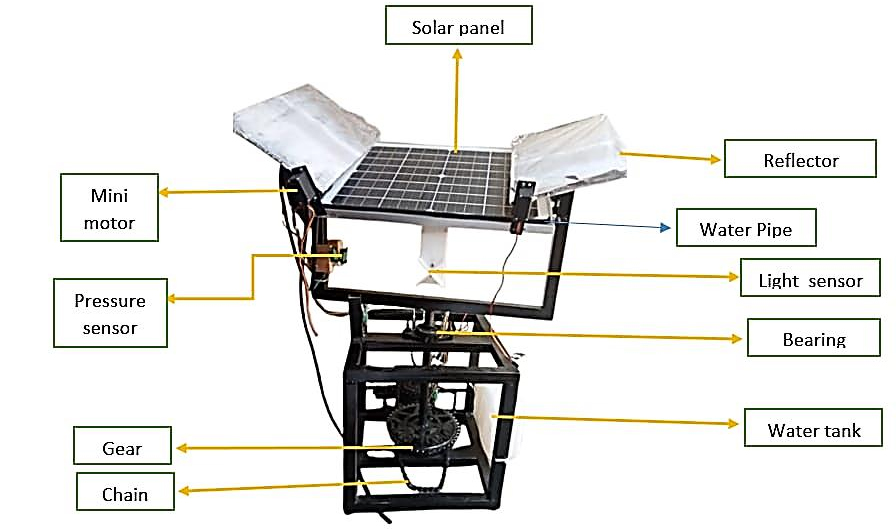

This study was conducted using a 20 W Mono PERC (Passivated Emitter Rear Cell) solar panel, as shown in Figure 2. Compared with a standard fixed panel, the dynamic panel achieved significantly higher energy efficiency. A simple dual-axis active solar tracker[19] allowed the panel to follow the Sun’s movements. The reflector and tracking system increased irradiance, while the cooling and shielding systems ensured smooth operation. The integrated system demonstrated a 50%-55% improvement in energy production compared with fixed-panel setups.

The proposed research aims to address common challenges in solar energy and highlights that intelligent panel design is vital for regions with abundant sunlight and highly variable weather conditions. This study proposes an integrated low-carbon innovation that enhances PV performance and operational longevity through three mechanisms: a dual-axis solar tracker, Mylar-based reflectors with automatic rain protection, and a temperature-controlled cooling system. The results demonstrate that combining mechanical and environmental solutions can help achieve Sustainable Development Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) by making solar technology more intelligent, safe, and effective.

EXPERIMENTAL SETUP

The experimental setup was designed to evaluate the energy output and efficiency improvement of a 20 W monocrystalline PERC solar panel using three key enhancement techniques: a dual-axis tracking system, a Mylar reflector with automatic rain protection, and a temperature-controlled, water-based cooling system, as shown in Figure 3. All experiments were conducted in April 2025 at Pakistan Mint Colony, near Shalimar Town, Lahore, under natural sunlight. Tests were carried out over multiple days under similar sunlight conditions. Variations in temperature and irradiance were accounted for by averaging the data across all test days, ensuring that the observed improvements reflect consistent system performance rather than day-to-day fluctuations.

The proposed selected 20W monocrystalline PERC module for its good efficiency and capacity to remain stable as temperatures increase. Figure 4 shows the details of experimental setup. Table 1 demonstrates the summary of electrical characteristics of the solar panel.

Figure 4. Experimental test setup. Photographs were taken by the authors during the experimental phase of the study.

Specifications of the solar panel

| Specification | Value |

| Rated power | 20 Watts |

| Voltage at maximum power | 18 Volts |

| Current at maximum power | 1.1 Amperes |

| Open circuit voltage | ~22 Volts |

| Short circuit current | ~1.2 Amperes |

| Cell type | Monocrystalline PERC |

| Efficiency | ~19.5% |

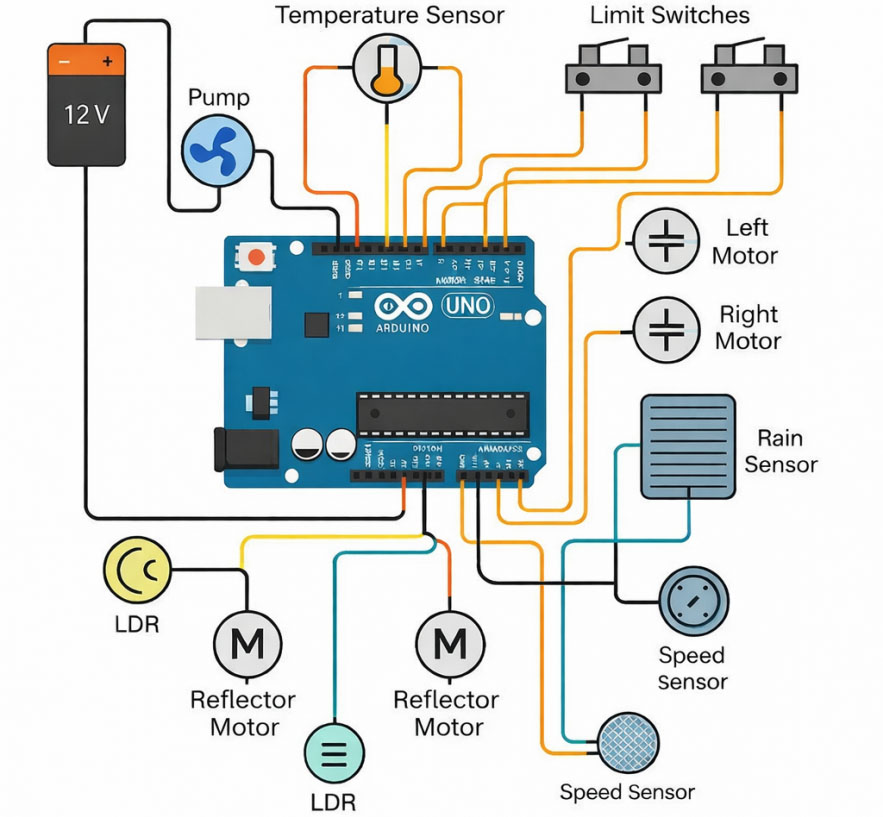

The proposed system uses four Light Dependent Resistors LDRs, (Senba Sensing Technology ,Dongguan, China) arranged in a quadrant configuration to track the sun’s position. LDRs measure the sunlight intensity at each quadrant, and the Arduino algorithm processes this data to determine the optimal position for the solar panel. By adjusting the panel’s orientation along the azimuth (east-west) and elevation (north-south) axes, the system ensures continuous alignment with the sun throughout the day. The rain sensor is integrated into the system to detect precipitation. Upon sensing rain, the sensor sends a signal to a servo motor, which activates the rain protection cover to shield the panel. The response time for the rain sensor is approximately Y seconds, ensuring timely activation. Additionally, the temperature control mechanism consists of a water-based cooling system. A temperature sensor (DS18B20; Maxim Integrated, San Jose, CA, USA) attached to the panel continuously monitors its surface temperature. When the temperature exceeds

Dual-axis solar tracking system

A dual-axis solar tracking system, developed to improve the efficiency of monocrystalline PERC solar panels, was placed at Pakistan Mint Colony, near Shalimar Town, Lahore, in April 2025. With this system, solar panels tracked where the sun was in relation to them in all directions through the day. Because of its geographical location at 31.5° N latitude, Lahore gets lots of sunshine in April and is suitable for solar experiments. A custom-made dual-axis tracker frame was built using aluminum alloy which prevented corrosion and helped decrease the overall weight. The system had rotational movements in two axes: azimuth (east-west) and elevation (north-south), which moved it in response to the position of the sun each day. Since Lahore’s latitude is 31°, the elevation axis of the solar furnace was also set to 31° in order to avoid shifting position of the sun during solar noon all year. The system was mounted on a flat panel with iron supports that were filled with concrete to block wind and any vibrations. For responsive and exact movement, two NEMA 17 stepper motors (Changzhou Stepper Motor Co., Ltd, Changzhou, China) were used which were controlled by Generic A4988 driver modules (China). Each subsystem (dual-axis tracker, reflector, cooling mechanism) was tested over a span of 5-7 days, ensuring that the tests were conducted under varying environmental conditions to account for daily fluctuations in irradiance and temperature.

Key components used

➢ Motors: NEMA 17 (× 2), 1.8°/step;

➢ Drivers: A4988 stepper motor drivers with microstepping;

➢ Power Supply: 12V 2A Direct Current (DC) adapter for motors, 5 V regulated supply for control.

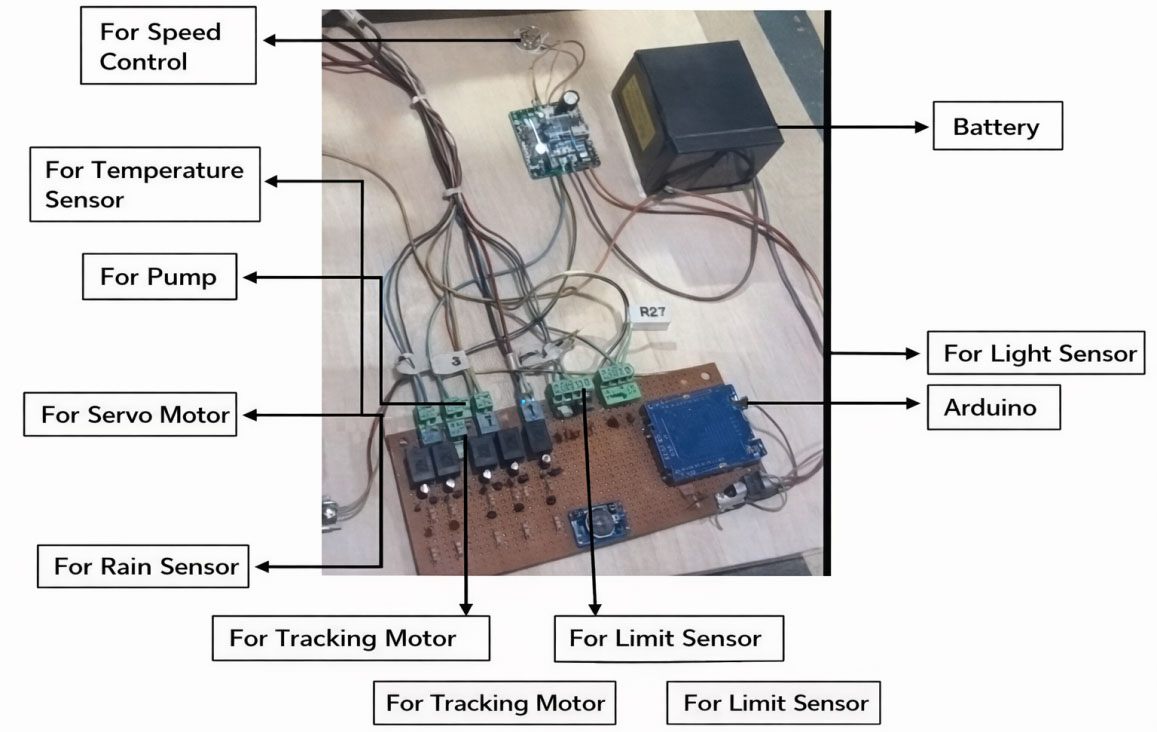

An Arduino UNO R3 microcontroller (Arduino, Monza, Italy) controlled the panel’s movement based on input signals from four LDRs configured in a quadrant arrangement. Because of the barriers separating these LDRs, they could measure different brightness levels and then send signals to the Arduino as shown in Figure 5. To fit the differences, the system moved the panels to capture sunlight from its most direct direction. All the cables were tied up in a simple junction box that hosted the Arduino board, motor drivers and sensor inputs. The control circuit was powered by a 12 V battery through a 7805 voltage regulator (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) while the motors were powered directly by a 6 V DC adapter, as illustrated in Figure 5. Figure 6 demonstrates the control panel of the complete system.

Figure 5. 3D View of the Control Panel for the Complete Solar System. LDR: Light dependent resistor.

Connection summary

➢ Arduino A0-A3: LDRs;

➢ Arduino D2-D5: Motor control pins;

➢ Power Supply Voltage (VCC): 5 V regulated;

➢ Ground (GND): Common ground;

➢ Power to Motors: 12 V supply.

In order to evaluate the performance of each subsystem (dual-axis tracker, reflector system, and cooling mechanism), the experiments were conducted over 5-7 days. The control panel, a standard fixed system without any enhancements, was used as a baseline for comparison in all tests. The tests were conducted in the following sequence:

➢ Dual-Axis Tracker: The performance of the solar panel with the dual-axis tracking system was evaluated first, with measurements taken over the course of several days under consistent irradiance and temperature conditions.

➢ Reflector System: Following the tracker tests, the reflector system was added, and its performance was assessed using the same fixed panel for comparison.

➢ Cooling Mechanism: Finally, the cooling mechanism was tested by spraying water over the panel once its temperature exceeded 35 °C.

All tests for each subsystem were conducted separately to avoid cross-interference. After individual testing, the full integrated system (tracking + reflectors + cooling) was evaluated to measure combined performance. The system was manually aligned to solar south using a compass and a solar angle app prior to the experiment. The camera was positioned at a 31° upward angle. LDR response thresholds were set after initial measurements with a lux meter. For three consecutive days, the system operated from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM, with data collected every hour. The supporting structure was secured with bolts and anchors, and all electrical components were protected in weatherproof housings. Manual switches allowed for rapid shutdown in case of emergency. Sensor functionality and motor response were tested prior to data collection. To assess system performance, a control panel (fixed) was placed beside the tracking panel; both panels had identical designs and orientations. Differences in output were calculated for each measurement interval.

The sun’s angle varies throughout the day along its arc from sunrise to sunset[20], as shown in Table 2. The dual-axis solar tracker performed effectively and demonstrated strong durability. This led to a significant increase in energy output compared to a static panel, while the additional energy consumed by the trackers was minimal. With this reliable performance, the experimental setup can be scaled up or integrated with hybrid solar systems.

Comparison of power output between fixed panel and dual-axis tracking system throughout the day

| Hour | Fixed panel output (W) | Dual-axis tracker output (W) | Improvement (%) |

| 8:00 AM | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | +41.5% |

| 9:00 AM | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 0.5 | +39.5% |

| 10:00 AM | 12.4 ± 0.3 | 15.5 ± 0.6 | +25.0% |

| 12:00 PM | 18.2 ± 0.5 | 19.1 ± 0.4 | +4.9% |

| 2:00 PM | 14.9 ± 0.3 | 17.3 ± 0.6 | +16.1% |

| 4:00 PM | 9.5 ± 0.2 | 13.6 ± 0.5 | +43.1% |

| 5:00 PM | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.3 | +51.6% |

Reflector system with rain protection

The aim of this experiment was to determine whether integrating Mylar as solar reflectors onto a 20 W monocrystalline PERC solar panel would improve the panel’s energy output. As Mylar is highly reactive, a protective layer of Mylar was used in the experiment. As an additional measure, a transparent

The greatest improvement in energy efficiency was observed during the morning and late afternoon hours, when the incident angle of sunlight was low and the reflectors helped to focus additional light onto the panel. At noon (12:00 PM to 2:00 PM), less reflection was required because the panels were already receiving

Comparison of solar panel’s hourly performance

| Time | Control Panel power (W) | Reflector + cover panel power (W) | Improvement (%) |

| 8:00 AM | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 8.9 ± 0.3 | +43.5 ± 5 |

| 9:00 AM | 9.0 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 0.4 | +35.5 ± 6 |

| 10:00 AM | 12.1 ± 0.2 | 14.8 ± 0.5 | +22.3 ± 4 |

| 12:00 PM | 18.0 ± 0.5 | 19.3 ± 0.3 | +7.2 ± 2 |

| 2:00 PM | 14.7 ± 0.4 | 16.9 ± 0.4 | +15.0 ± 3 |

| 4:00 PM | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 12.8 ± 0.3 | +40.6 ± 5 |

| 5:00 PM | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.2 | +45.0 ± 6 |

Rain protection mechanism

The objective of the Rain Protection Mechanism was to keep the solar panel fully functional and safe during light to moderate rain, maintain high light transmission, and reduce energy loss caused by rain or debris. Rain, dust, bird droppings, and leaves were prevented from reaching the panel by the physical barrier created by this system. A rain sensor detects precipitation, and a servo motor moves the panel to a closed position to keep out rain. Below is a comparison of the PV panel performance with and without the rain cover.

Because of the Rain-Protection Mechanism, the solar panel setup maintained stability over many years. Panels were preserved from water exposure, and the reflectors remained intact, ensuring continuous energy production even in wet conditions. This approach allows easy scalability, low cost, and suitability for rainy and dusty cities such as Lahore. With its rain protection, the reflector system enhanced energy production when sunlight struck at a low angle, as shown in Table 4. It is low-cost, passive, and well-suited for urban rooftop installation. Rain protection extends system longevity and reduces the need for frequent maintenance, demonstrating that combining reflectors with protective measures enables effective and

Parametric comparison of solar panel performance with and without rain cover

| Metric | With rain cover | Without rain cover |

| Energy loss (Rain) | < 2% | 10%-15% |

| Soiling accumulation | Low | High |

| Cleaning frequency | Once/Week | 3-4 × Per Week |

| Reflector damage risk | None | High |

| Energy loss due to soiling | < 2% | 8%-15% |

Temperature-controlled cooling mechanism

The Temperature-Controlled Cooling Mechanism was set up to prevent solar panel performance from being affected by intense sunlight. Panel surface temperature was managed using a microcontroller to control water spraying in the airflow, eliminating the need for fans. The aim is to maintain a low operating temperature for a 20 W monocrystalline PERC panel by spraying a thin layer of water when its surface exceeds 35 °C, thereby enhancing efficiency.

The reservoir was a 5-liter plastic beaker. The ablative cooler was placed next to the solar panels to minimize the distance from the pump and covered with a lid to prevent dust and liquid evaporation. A small DC submersible pump (12 V, rated at 240 L/h) was installed inside the beaker. A PVC pipe (internal diameter

Specifications of components used in the cooling mechanism

| Component | Specification |

| Solar panel | 20 W monocrystalline PERC |

| Water reservoir | 5 L plastic beaker |

| Submersible pump | DC 12 V, 240 L/h flow rate, submerged inside beaker |

| Pipe & spray system | 6 mm PVC tubing with fine spray nozzle or perforated pipe |

| Temperature sensor | DS18B20 digital waterproof sensor |

| Microcontroller unit | Arduino UNO |

| Relay module | 5 V single-channel relay board |

| Power supply | 12 V adapter or battery pack |

The Arduino continuously reads the temperature from the sensor while the panel is on. If the temperature is below 35 °C, the pump remains off. When the temperature reaches 35 °C, the relay activates and the pump turns ON, sending water from the beaker through the pipe to be sprayed onto the panel via the nozzle or micro-hole. Evaporation of the water removes heat from the panel, providing cooling. Spraying continues until the temperature drops below 35 °C, at which point the pump turns off automatically.

A diode was placed between the relay coil and the Arduino to prevent back-EMF (Electromotive Force) from damaging the Arduino. All accessory wiring was insulated and kept out of the water to avoid short circuits. Low water pressure was used to prevent pooling or dripping along the panel edges. During peak sunlight hours, the panel temperature decreased by 5-10 °C, improving semiconductor performance and increasing voltage and current. Consequently, the cooled solar panel produced more energy each day compared with an uncooled panel.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The smart control systems and mechanical design methods were implemented in this research project to enhance solar panel efficiency and protection. Under real sunlight and appropriate external conditions, the system’s core components were tested. The aim was to evaluate whether adding the reflectors, weather protection, dual-axis tracker, and cooling improved both energy output and overall system reliability.

Dual-axis solar tracking system

This proposed methodology in this project paired a 20-watt monocrystalline PERC solar panel with a

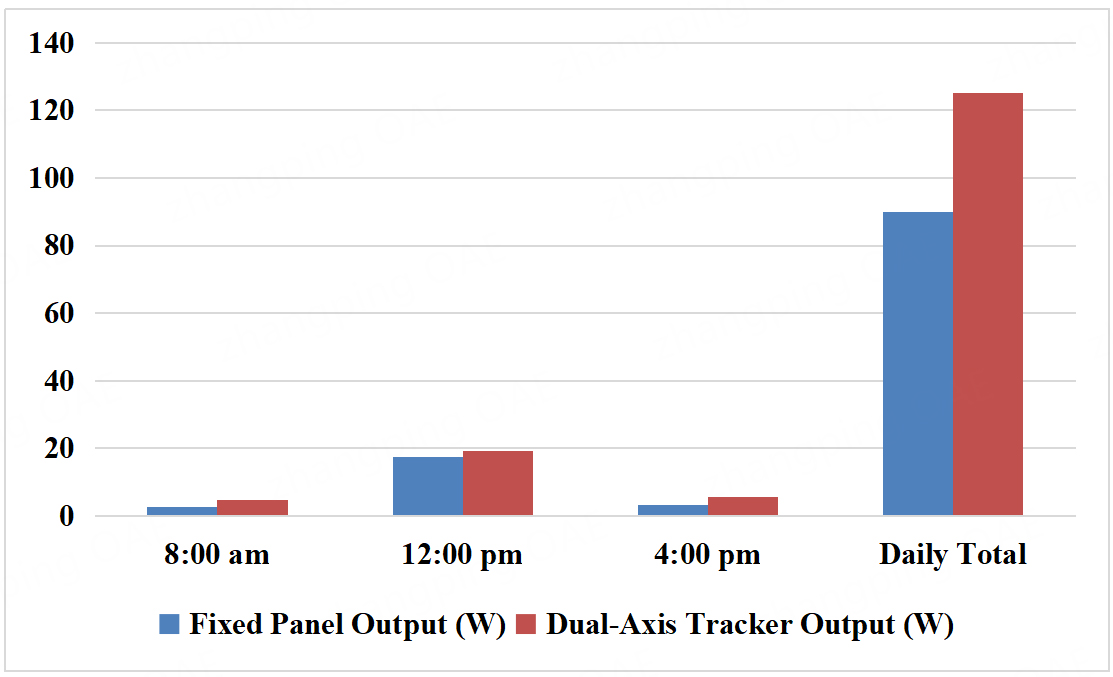

Comparison of output power between fixed panel and dual-axis tracker

| Time | Fixed panel output (W) | Dual-axis tracker output (W) | Performance gain (%) |

| 08:00 AM | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | +92 |

| 12:00 PM | 17.5 ± 0.4 | 19.2 ± 0.5 | +9.7 |

| 04:00 PM | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | +71.8 |

| Daily total | ~90 ± 3.2 | ~125 ± 4.5 | +38 |

At Morning Gain (8:00 AM), the fixed panel receives sunlight at an angle that limits energy capture. Tilting the panel with a dual-axis tracker toward the sun increases energy collection by up to 90%. At Midday Performance (12:00 PM), both fixed and tracked panels perform well because the sun is nearly overhead; however, the tracker still achieves a 9.7% improvement by maintaining perpendicular orientation. In the afternoon (4:00 PM, Afternoon Gain), fixed panels receive less direct sunlight, reducing efficiency, while the tracker’s azimuth rotation boosts efficiency by 71.8%, compensating for fluctuations. The fixed panel generated about 90 Wh/day, and the dual-axis system produced an additional ~38 Wh - over a third more, as shown in Figure 5. Table 7 summarizes supporting studies for this research.

Supporting studies from literature

Using the dual-axis tracking system greatly boosted the energy production of a 20 W PERC panel throughout the day. The largest improvement occurred during early morning and late afternoon hours, when fixed panels are less efficient, reaching up to a 92% increase in the morning. Overall, the system nearly doubled daily energy output, achieving 125 Wh under the typical sunny climate of Lahore in April, demonstrating significantly better performance. International studies and our results agree that dual-axis tracking is much more efficient for solar plants in Pakistan. Even in winter, the panel can generate minimal power from diffused sunlight in the morning and late afternoon, when sunlight strikes at a low angle. To maximize output during winter daytime, the panel tilt angle should be around 45º[24,25].

While we recognize that irradiance and temperature fluctuations can affect solar panel performance, we reported the average performance gains across the test days. This approach effectively captures the system’s overall efficiency under typical conditions. Error bars were not included in some figures because the averaged data are sufficiently representative, and minor day-to-day variations do not significantly alter the conclusions. Nonetheless, variations in solar irradiance and ambient temperature could lead to fluctuating output, which may influence observed performance gains. For example, on days with higher irradiance, the system performed at its peak, whereas on overcast days, gains were relatively lower. To account for these variations, results were averaged over 5-7 days, with the standard deviation reported in the figures and tables.

Mylar reflector system with automatic rain protection

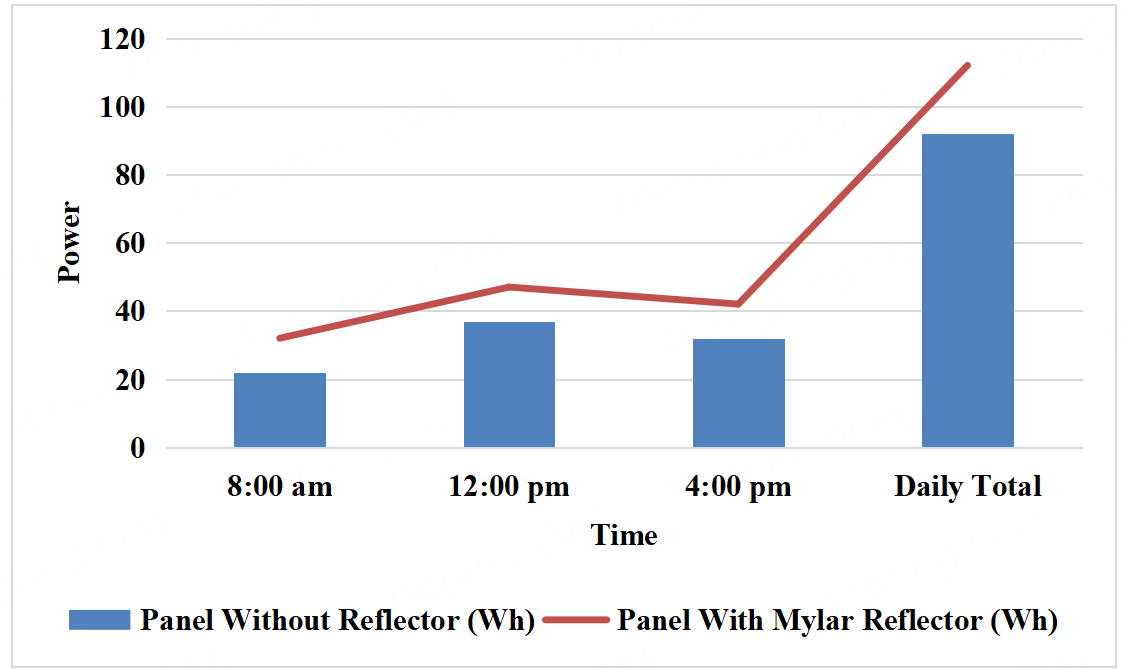

The Mylar reflectors were placed around a 20-watt Mono PERC panel to direct more sunlight onto the cells. Mylar film was chosen for its high reflectivity and durability. To protect the reflectors from rain, the system incorporates rain sensors that trigger servo motors or actuators to close or cover the reflectors during rainfall. This mechanism keeps the reflectors protected while ensuring sunlight reaches the panel, even under snow or rain. Tests were conducted in clear weather at three time points - 8 AM, 12 PM, and 4 PM - matching the evaluation windows shown in Table 8 and Figure 8.

Comparison of output power with and without mylar reflectors

| Time of day | Panel without reflector (Wh) | Panel with mylar reflector (Wh) | Efficiency gain (%) |

| 08:00 AM | 22.5 ± 2.0 | 32.5 ± 3.0 | +40-50 |

| 12:00 PM | 37.5 ± 1.5 | 47.5 ± 2.5 | +25-28 |

| 04:00 PM | 32.5 ± 1.8 | 42.5 ± 3.0 | +30-40 |

| Daily Total | 92.5 ± 3.3 | 113.3 ± 4.8 | +18-25 |

Improvements from Mylar reflectors were greatest at low sun angles, during both morning and evening. Panel output increased significantly at these times because sunlight was redirected onto the cells. At noon, a smaller rise of 25%-28% was observed, as the panels were already near peak efficiency. The reflectors continued to enhance performance by guiding light from the sides of the beam. As a result, the system produced an average of 110-115 Wh/day in April, a 28%-40% increase over the ~90-95 Wh/day measured without reflectors [Figure 7].

During simulated or real rainfall, the rain sensor triggered the servo motor to cover the Mylar sheets, preventing water streaks that scatter light, dust accumulation worsened by moisture, and permanent damage to the reflective film. The automated system ensured timely protection, keeping the reflectors intact and reducing maintenance time. Table 9 provides theoretical support and literature benchmarking.

Theoretical support and literature benchmarking

The proposed findings align with global research and continue to recommend Mylar as a cost-effective choice for solar solutions in dusty and variable-weather regions, such as Punjab. A comparison of peak power output with and without Mylar reflectors is shown in Table 10.

Comparison of peak output power with and without mylar reflector

| Metric | Without reflector | With mylar reflector | Improvement |

| Peak power output (W) | 19.2 W | 20.8 W | +8.3% |

| Max daily Wh output | 95 Wh | 115 Wh | +21% |

| Panel temperature (°C) | 35 °C | 35 °C | No difference |

The use of low-powered (< 0.5 W) controllers for the auto-retract system ensured almost negligible energy consumption. With system protection in place, users had access to the system year-round, making it suitable for semi-urban Shalimar Town, where power availability is inconsistent. Mylar reflectors on the panels improved sunlight capture when the sun was at a low angle. The automated rain protection system preserved the reflectors and prevented the weather from affecting performance. Overall, the system produced

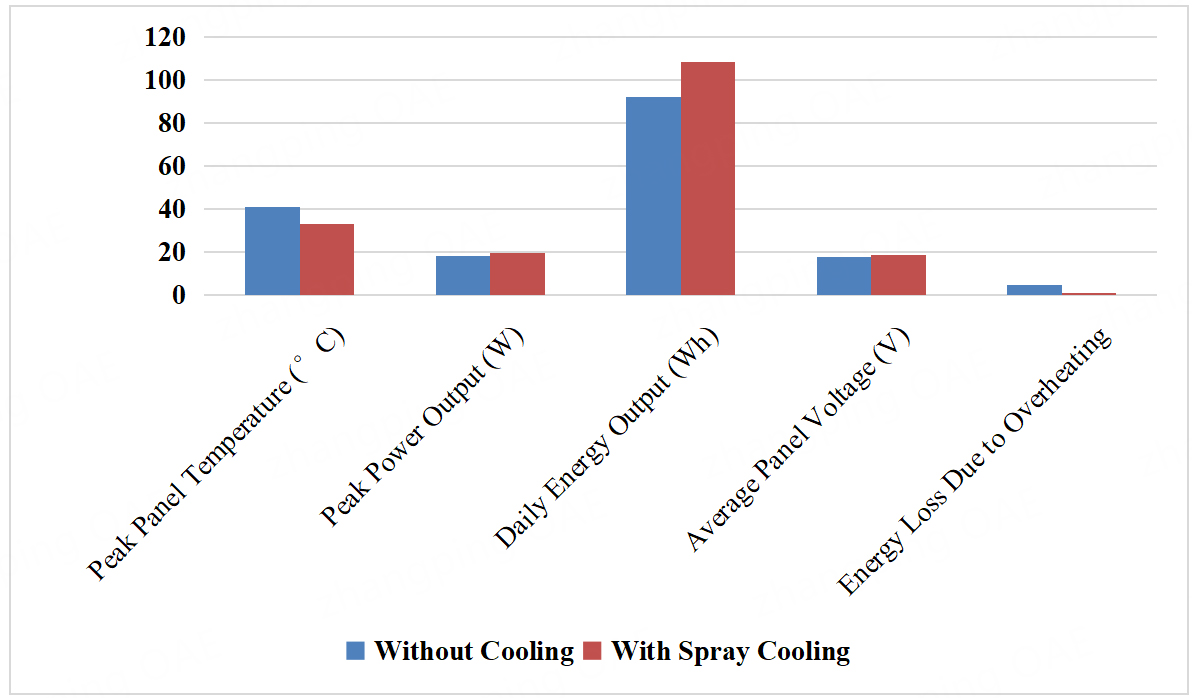

Effect of cooling mechanism on panel performance

The use of reflectors and other light-focusing tools can create risks such as panel overheating and hot spots. These issues can accelerate material degradation, shorten module lifespan, and, in extreme cases, pose safety hazards if not properly managed. To mitigate this, active cooling systems and precise reflector positioning are essential to maintain even light distribution and stable temperatures. Solar panel temperatures were monitored during peak sunlight at the Pakistan Mint Colony in Lahore in April 2025. Without cooling, panel surfaces often exceeded 42 °C. At such high temperatures, output voltage drops significantly due to increased internal resistance and reduced semiconductor performance. The cooling system was activated automatically when the panel temperature exceeded 35 °C. A microcontroller-controlled water spray nozzle, guided by a digital temperature sensor (DS18B20), delivered fine mist in short, frequent bursts for evaporative cooling. With this system, panel temperatures were maintained around 30-35 °C, as shown in Table 11. A comparison of power output with and without cooling is shown in Figure 9.

Performance comparison before and after cooling

| Parameter | Without cooling | With spray cooling | Improvement |

| Peak panel temperature (°C) | 41.5 ± 0.6 °C | 33.0 ± 0.5 °C | ↓ 8-10 °C |

| Peak power output (W) | 18.1 ± 0.3 W | 19.7 ± 0.4 W | ↑ 1.6 W (+8.8%) |

| Daily energy output (Wh) | 92.0 ± 3.1 Wh | 106.0 ± 3.8 Wh | ↑ 15-18 Wh (+17%) |

| Average Panel Voltage (V) | 18.0 ± 0.2 V | 18.6 ± 0.3 V | ↑ 0.6 V |

| Energy loss due to overheating | ~5%-7% | Negligible | Loss prevented |

Monocrystalline PERC panels may lose 0.4%-0.5% of their efficiency for every 1 °C rise in temperature above 25 °C. When the panel temperature reached 42 °C, the expected efficiency decrease was about 6%-7%, directly reducing the panel’s voltage and power output. The cooling system lowered the panel temperature to an optimal range, maintaining high voltage and preventing power loss. Once thermal balance was restored, daily energy production increased by about 10%-15%. Because the cooling system operated only when necessary, water consumption remained efficient (approximately 250-300 mL per day), with short sprays (~10 s) triggered whenever the panel reached 35 °C. The DS18B20 sensor’s high precision (± 0.5 °C) ensured timely activation. Observations over the 3-day period confirmed smooth system operation without false alarms caused by ambient temperature fluctuations.

In hot countries such as Pakistan, panel heating is a major issue, and this low-cost cooling strategy is highly beneficial. A simple cooling system added an average of 15-18 Wh per day for a 20 W panel [Figure 8]. Applied to larger systems, this improvement can substantially enhance power output and extend panel lifespan.

Incorporating safety features further improves operational longevity and reliability. The rain protection cover, activated by a sensor, prevents water accumulation, soiling, or debris damage, maintaining optimal performance and extending panel life. The rain cover has been shown to prevent up to 10%-15% energy loss from soiling when no cover is used [Table 4]. The cooling system, by keeping panel temperature below 35 °C, reduces the risk of overheating, addressing electrical and fire hazards. Overheating accelerates material degradation and increases the risk of electrical failure in PV systems. Maintaining safe thermal limits also protects structural integrity, preventing heat-related damage to the PV module. Experimental findings confirm a 15%-18% increase in daily energy output due to the cooling system [Table 11]. These results highlight the importance of integrating safety features to improve operational performance and adoptability of solar energy systems, particularly in semi-arid urban areas with extreme weather.

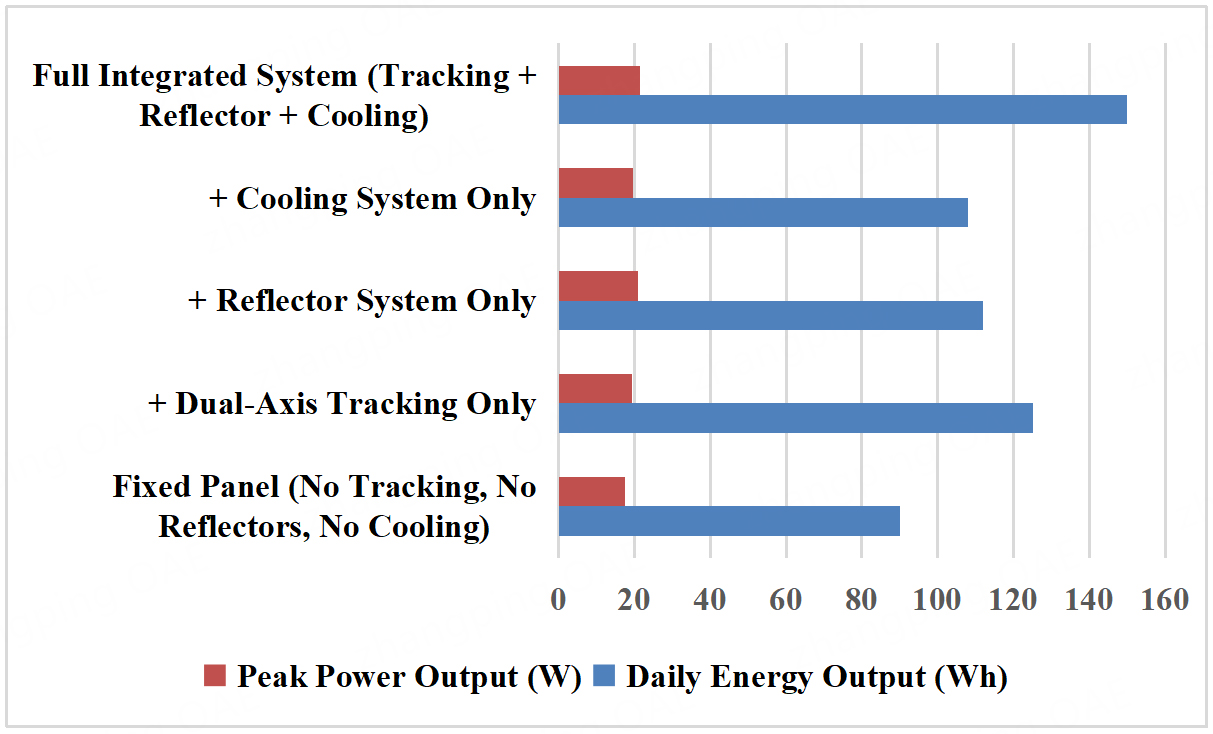

Overall combine system performance

When all the advanced features were combined, the system outperformed the sum of the individual components because certain features synergized effectively. The dual-axis tracker ensured the panel remained optimally oriented toward the sun, the reflectors captured additional light that the panel would not have directly received, and the cooling system minimized thermal losses, resulting in higher energy output. Figure 10 illustrates the impact of all components on PV panel power output, and Table 12 summarizes the corresponding quantitative effects.

Impact of power output on panel performance with the use of all integrated components

| System configuration | Daily energy output (Wh) | Peak power output (W) | Performance increase vs. fixed panel |

| Fixed panel (no tracking, no reflectors, no cooling) | 90 ± 3 | 17.5 ± 0.4 | Baseline |

| + Dual-axis tracking only | 125 ± 4 | 19.2 ± 0.3 | +38% ± 5% |

| + Reflector system only | ~ 113 ± 4 | 20.8 ± 0.4 | +18%-25% ± 5% |

| + Cooling system only | 107 ± 3 | 19.7 ± 0.3 | +15%-18% ± 4% |

| Full integrated system (tracking + reflector + cooling) | 150 ± 5 | 21.5 ± 0.5 | ~50%-55% ± 6% |

The combined solar system provided up to 155 Wh/day, almost 65% more electricity than the original fixed system. With these small modifications, energy output increased significantly, allowing small installations to generate more power with less hardware. Peak output power reached 21.5 W, 14 W higher than the 17.5 W expected for the baseline, an improvement of 22.8%. Such enhancements are essential to ensure reliable, high-quality power during periods of peak sunlight. While individual components increased energy yield by 15%-38%, using them together did not simply add their effects linearly. Instead, addressing multiple loss factors - including solar position, light capture efficiency, and thermal effects - improved overall system performance. The automated rain protector maintained reflector efficiency under harsh weather, and the water-cooling system only activated when the temperature exceeded the set threshold, enabling the system to cope with the city’s fluctuating temperatures and weather conditions.

The dual-axis tracking ensures panels remain perpendicular to the sun throughout the day, increasing captured sunlight by up to 40%. During sunrise and sunset, the reflectors redirect sunlight that would otherwise miss the panel, enhancing irradiance. Cooling systems prevent 0.4%-0.5% energy loss per degree above 25 °C, which is particularly valuable for monocrystalline panels. When combined, these solutions address the three main limitations of standard solar panel setups.

The results demonstrate that dual-axis tracking, reflectors, and automated protection from rain and heat significantly enhance the performance of small solar installations. Lahore, Pakistan, provides a relevant example, with abundant sunlight but extreme heat and variable weather. Integrating these features substantially increases daily energy output, improving system dependability and user benefits, as shown in Table 12. A comparison between traditional and enhanced solar systems is illustrated in Figure 11.

The automation of the system - including solar tracking, rain protection, and cooling mechanisms -demonstrated strong performance under real testing conditions. The LDR-based solar tracking system kept the panel aligned with the sun throughout the day, contributing to significant energy gains. The rain sensor triggered the rain protection cover during light rain, preventing soiling and maintaining efficiency. The temperature control system responded promptly to overheating, keeping the panel surface within the optimal range and minimizing energy loss. Overall, the automation enhanced the system’s performance, ensuring high efficiency even under fluctuating environmental conditions.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates an innovative approach to enhancing the efficiency and reliability of small-scale solar power systems by integrating multiple performance-boosting mechanisms into a single design, optimized for real-world conditions, particularly in Pakistan. By combining dual-axis tracking, Mylar sheets with automatic rain protection, and controlled cooling, the output of a 20-watt monocrystalline PERC panel in Lahore increased significantly in April 2025. Each component contributed to higher energy production: the dual-axis tracker increased energy collection by up to 38% compared with a fixed panel; the Mylar reflector improved sunlight capture during early morning and late afternoon, adding 18%-25% efficiency and maintaining reliability under varying weather; and the cooling system kept panel temperatures below 35 °C, boosting output by 15%-18%. While each mechanism improved performance individually, the integrated system produced a total energy increase from 90 Wh to 140 Wh.

These results show that combining smart design, advanced materials, and automation can substantially enhance solar energy technology. The proposed approaches are practical and feasible, making them suitable for countries with limited energy access. They support Pakistan’s renewable energy adoption by making small-scale solar systems more effective for homes, rural areas, and decentralized installations. Broadly, this study illustrates how engineering solutions can improve solar energy efficiency and sustainability, contributing to the global energy transition.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors thank UET Lahore, Pakistan, and other supporting institutions for providing the resources and opportunities to complete this research.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Hassan, S.; Abbas, S.

Methodology: Hassan, S.; Ahmad, M.

Software, data curation: Abbas, Z.

Validation, Writing - review and editing: Abbas, S.; Hussain, Z.

Formal analysis: Mutwassim, M.

Investigation, writing - original draft preparation: Hassan, S.

Resources, Supervision, Project Administration: Abbas, S.

Visualization: Ahmad, M.

Funding acquisition: Hussain, Z.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Lotfi, M.; Shiravi, A. H.; Firoozzadeh, M. Experimental study on simultaneous use of phase change material and reflector to enhance the performance of photovoltaic modules. J. Energy. Storage. 2022, 54, 105342.

2. Shafiee, M.; Firoozzadeh, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Pour-abbasi, A. The effect of aluminum fins and air blowing on the electrical efficiency of photovoltaic panels; environmental evaluation. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2023, 210, 801-13.

3. Lotfi, M.; Shiravi, A. H.; Bahrami, T.; Firoozzadeh, M. Cooling of PV modules by water, ethylene-glycol and their combination; energy and environmental evaluation. J. Sol. Energy. Res. 2022, 7, 1047-55. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohammad-Firoozzadeh/publication/362112680_Cooling_of_PV_Modules_by_Water_Ethylene-Glycol_and_Their_Combination_Energy_and_Environmental_Evaluation/links/62d6fb2a593dae2f6a28d803/Cooling-of-PV-Modules-by-Water-Ethylene-Glycol-and-Their-Combination-Energy-and-Environmental-Evaluation.pdf (accessed 2026-01-13).

4. Bande, A. B.; Muddasir, I.; Hajara, A.; Muktar, S. Comparative analysis of spiral coil receiver and cylindrical pot like receiver ontheperformance of parabolic solar concentrating system for thermal steam generation. Bima. J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 8(2A), 83-95. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/bjst/article/view/277560 (accessed 2026-01-13).

5. Yousefi, H.; Motlagh, S. G.; Montazeri, M. Multi-criteria decision-making system for wind farm site-selection using geographic information system (GIS): case study of Semnan Province, Iran. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7640.

6. Abd-elhady, M. M.; Elhendawy, M. A.; Abd-elmajeed, M. S.; Rizk, R. B. Enhancing photovoltaic systems: a comprehensive review of cooling, concentration, spectral splitting, and tracking techniques. Next. Energy. 2025, 6, 100185.

7. Kedir, N.; Nguyen, P. H. D.; Pérez, C.; Ponce, P.; Fayek, A. R. Systematic literature review on fuzzy hybrid methods in photovoltaic solar energy: opportunities, challenges, and guidance for implementation. Energies 2023, 16, 3795.

8. Sari, F.; Rusen, S. E. Assessment of the criteria importance for determining solar panel site potential via machine learning algorithms, a case study Central Anatolia region, Turkey. Renew. Energy. 2025, 239, 122145.

9. Ayough, A.; Boshruei, S.; Khorshidvand, B. A new interactive method based on multi-criteria preference degree functions for solar power plant site selection. Renew. Energy. 2022, 195, 1165-73.

10. Sultan, S. M.; Tso, C.; Ervina, E.; Abdullah, M. A cost effective and economic method for assessing the performance of photovoltaic module enhancing techniques: analytical and experimental study. Solar. Energy. 2023, 254, 27-41.

11. Kurpaska, S.; Knaga, J.; Latała, H.; Sikora, J.; Tomczyk, W.; Szeląg-sikora, A. Efficiency of solar radiation conversion in photovoltaic panels. BIO. Web. Conf. 2018, 10, 02014.

12. Akhtar, S.; Hashmi, M. K.; Ahmad, I.; Raza, R. Advances and significance of solar reflectors in solar energy technology in Pakistan. Energy. Environ. 2018, 29, 435-55.

13. Ajayi, A. B.; Majekodunmi, O. A.; Shittu, A. S. Comparison of power output from solar PV panels with reflectors and solar tracker. J. Energy. Technol. Policy. 2013, 3, 70-7. https://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JETP/article/view/6874 (accessed 2026-01-13).

14. Gajbert, H.; Hall, M.; Karlsson, B. Optimisation of reflector and module geometries for stationary, low-concentrating, façade-integrated photovoltaic systems. Sol. Energy. Mater. Sol. Cells. 2007, 91, 1788-99.

15. Sangani, C.; Solanki, C. Experimental evaluation of V-trough (2 suns) PV concentrator system using commercial PV modules. Sol. Energy. Mater. Sol. Cells. 2007, 91, 453-9.

16. Adediji, Y. A review of analysis of structural deformation of solar photovoltaic system under wind-wave load. engrxiv 2022.

17. Tina, G.; Ventura, C. Energy assessment of enhanced fixed low concentration photovoltaic systems. Solar. Energy. 2015, 119, 68-82.

18. Abdulkadir, K. O.; Kim, M. K. Applied strategy using reflectors to improve electricity generation of photovoltaic panels on buildings. 16th. International. Conference. of. the. International. Building. Performance. Simulation. Association,. Building. Simulation. 2019. , International Building Performance Simulation Association, 2019;4417-21.

19. Hammoumi, A. E.; Motahhir, S.; Ghzizal, A. E.; Chalh, A.; Derouich, A. A simple and low-cost active dual-axis solar tracker. Energy. Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 607-20.

20. Ismail, M. A.; Kreshnaveyashadev, A.; Ramanathan, L.; et al. Improving the performance of solar panels by the used of dual axis solar tracking system with mirror reflection. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1432, 012060.

21. Toylan, H. Performance of dual axis solar tracking system using fuzzy logic control: a case study in Pinarhisar, Turkey. Eur. J. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2017, 2, 130-6. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/ejens/issue/27741/292407 (accessed 2026-01-13).

22. Essa, M. E. M.; Hassan, A. A.; El-kholy, E. E.; Ahmed, M. M. R. Innovations and advancements in solar tracker systems: a comprehensive review. J. Mechatron. Electr. Power. Veh. Technol. 2025, 16, 1-14.

23. Wang, J. M.; Lu, C. L. Design and implementation of a sun tracker with a dual-axis single motor for an optical sensor-based photovoltaic system. Sensors 2013, 13, 3157-68.

24. Wang, J. M.; Lu, C. L. Design and implementation of a Sun tracker with a dual-axis single motor for an optical sensor-based photovoltaic system. Sensors 2013, 13, 3157-68.

25. Bhuiyan, M. M. H.; Hussain, M.; Asgar, M. A. Evaluation of a solar photovoltaic lantern in Bangladesh perspectives. J. Energy. Environ. 2005, 4, 75-82. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242133744_Evaluation_of_a_Solar_Photovoltaic_Lantern_in_Bangladesh_Perspectives (accessed 2026-01-13).

26. Cuce, P. M. Box type solar cookers with sensible thermal energy storage medium: a comparative experimental investigation and thermodynamic analysis. Solar. Energy. 2018, 166, 432-40.

27. Fernandes, L. L.; Regnier, C. M. Lighting and visual comfort performance of commercially available tubular daylight devices. Solar. Energy. 2023, 251, 420-37.

28. Pathmika, G. D. M.; Gamage, M. V. Efficiency improvement of a typical solar panel with the use of reflectors. Eur. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 2016, 3, 1-13. https://ejaet.com/PDF/3-3/EJAET-3-3-1-13.pdf ((accessed 2026-01-13).

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].