From cycling to climate benefit: a perspective on redefining CO2 utilization for reduction and storage

Abstract

Carbon capture and utilization (CCU) mitigates climate change by converting CO2 into fuels, chemicals, and construction materials. From a life-cycle perspective, CCU benefits arise from preventing point-source emissions, substituting for carbon-intensive products, and coupling with renewable energy to lower upstream impacts. However, high energy needs, feedstock costs, and capture requirements continue to limit large-scale deployment. This perspective reframes CCU beyond conventional cycling by outlining three strategic pathways: replacing high-emission fossil products such as urea to maximize substitution benefits even when CO2 is later re-emitted; sourcing CO2 from biogenic streams to create near-neutral cycles; and using CO2 as a hydrogen carrier that transports energy and enables subsequent permanent storage through concrete mineralization. Combined with falling renewable electricity costs, industrial co-location, and targeted policy support, CCU can progress from niche demonstrations to a scalable contributor to industrial decarbonization and climate-neutral production.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Reaching net-zero emissions requires more than simply eliminating fossil fuels; it demands new approaches to reimagine carbon. Carbon capture and utilization (CCU) has emerged as a promising pathway, converting carbon dioxide (CO2) from waste into feedstock for fuels, chemicals, and construction materials. Unlike conventional carbon capture and storage (CCS), which focuses on geological disposal, CCU generates economic value while addressing emissions. Yet its role remains contested: it is praised as a catalyst for circular carbon economies but criticized for high energy demand, limited storage capacity, and uncertain scalability[1]. At the same time, a paradox lies at the heart of our climate challenge. The world urgently seeks to eliminate CO2 emissions, yet billions are still spent extracting fossil carbon to produce the same chemicals and materials that could instead be synthesized from captured CO2. Methanol, urea, concrete, and plastics all contain carbon atoms that are chemically identical regardless of their origin. This reality positions CCU not as a peripheral technology, but at the convergence of necessity and opportunity - where the demand for climate action meets humanity’s reliance on carbon-based products[2]. CCU’s significance extends beyond carbon mitigation. In many industries, where decarbonization often forces a trade-off between competitiveness and environmental responsibility, CCU offers a rare alternative. When powered by renewable energy and integrated into existing infrastructure, it can reduce emissions, generate valuable products, and create new revenue streams. This alignment of environmental and economic objectives presents a unique opportunity to reshape industrial systems without compromising growth. The timing is critical: plummeting renewable electricity prices and the rapid growth of green hydrogen (H2) are making CO2 conversion increasingly feasible[2,3]. Technologies once considered too energy-intensive are now being deployed, and the debate is no longer about technical possibility but about speed, scale, and which sectors to prioritize[4]. Previous studies have shown that the climate benefit of CCU depends not only on the amount of CO2 captured but also on the duration for which it is stored. Hepburn et al. (2019)[5] distinguished short-lived “cycling” pathways - where CO2 quickly re-enters the atmosphere - from “closed” pathways such as geological storage that ensure near-permanent removal. Gabrielli et al. (2020)[1] further highlighted that renewable energy integration and consistent system boundary definitions are crucial for determining whether CCU can rival CCS in industrial decarbonization. More recently, Nyqvist et al. (2025)[6] emphasized the role of storage duration, noting that many life-cycle assessments overlook re-emission timing, even though most fuels and chemicals release CO2 within weeks or months. For example, Win et al. (2023)[7] and Ravikumar et al. (2021)[8] demonstrated potential climate benefits for methanol and other CO2-derived products but without fully accounting for re-emission, leading to an overestimation of avoidance potential. Although these frameworks have established the importance of permanence and renewable energy, the overall understanding of CCU remains fragmented. While previous studies have emphasized temporal permanence and energy decarbonization as key determinants of CCU’s performance, there are broader ways to view CCU that reveal greater and more durable climate benefits beyond short-term carbon cycling. One such approach involves using carbon-neutral or biogenic CO2 sources, which allows even short-lived CCU products - such as fuels or fertilizers - to operate within a closed carbon loop, preventing new fossil emissions and achieving effective climate neutrality. Another promising direction lies in dual or extended uses of CO2, where the same captured carbon serves multiple functions - for instance, first as a feedstock for hydrogen-carrier fuels such as methanol or formic acid, and later as an input for cement curing or mineralization. This sequential or cascading use not only maximizes the value of captured CO2 but also pushes the boundary of CCU from temporary utilization toward longer-term carbon retention. In this way, the study presents CCU as a continuum of opportunities - where utilization and storage coexist - to enhance both economic and climate benefits within integrated carbon management systems.

CCU MECHANISMS AND FRAMEWORKS

Defining the enhanced CCU framework

CCU encompasses both utilization processes that capture CO2 from industrial emissions or the atmosphere and convert it into products such as fuels, chemicals, or construction materials. Traditionally, CCU has been synonymous with "cycling" pathways - applications in which CO2 returns to the atmosphere within weeks to months after product use. These conventional approaches provide climate benefits primarily through fossil feedstock substitution: producing methanol, urea, or synthetic fuels from captured CO2 reduces the need to extract virgin fossil carbon, and when powered by renewable energy, significantly lowers upstream emissions. However, the temporary nature of storage has led critics to question whether such pathways can meaningfully contribute to long-term climate goals. The broader concept of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) recognizes that both carbon utilization and permanent sequestration play complementary roles in achieving net-zero emissions. CCUS frameworks acknowledge that neither pathway alone is sufficient for deep decarbonization: permanent storage is essential for sectors with hard-to-abate emissions, while utilization can offset carbon-intensive production in the chemical and materials industries. Consequently, most policy discussions and capacity targets now adopt a CCUS perspective rather than treating CCS and CCU as competing alternatives.

This perspective advances what we term an enhanced CCU framework that moves beyond the conventional cycling paradigm. Rather than viewing CCU solely as temporary carbon recycling, we propose three distinct pathways that expand its climate potential. The first pathway retains the cycling concept but emphasizes the integration of renewable hydrogen to maximize fossil substitution benefits. The second pathway - biogenic-integrated CCU - achieves climate neutrality by coupling biogenic CO2 sources (such as emissions from bioethanol production) with renewable hydrogen, effectively closing the carbon cycle through biomass regrowth while preventing new fossil extraction. The third pathway pursues durable storage through two mechanisms: mineralization in concrete that locks CO2 for centuries, and CO2-derived hydrogen carriers that enable separation and permanent storage at the point of use. This latter mechanism is particularly significant because it allows products traditionally classified as "cycling" to become pathways for permanent removal when integrated with appropriate infrastructure. What distinguishes this enhanced framework from existing classifications is the explicit coupling of carbon source with end-of-life fate. Previous frameworks effectively categorized pathways by storage duration and energy requirements, establishing that "cycling" and "closed" applications deliver fundamentally different climate outcomes. Our framework builds on these insights but introduces an additional strategic dimension: recognizing that the origin of CO2 - whether fossil or biogenic - determines whether short-duration storage represents temporary avoidance or climate-neutral cycling. Similarly, we emphasize that end-of-life, particularly for hydrogen carriers, can transform the classification of a product from cycling to durable storage. This source-fate coupling reveals that CCU's climate contribution is not predetermined by product type alone, but rather by strategic choices in feedstock selection and system design. Table 1 summarizes the key distinctions between these pathways.

Comparison of conventional and enhanced CCU frameworks

| Aspect | Conventional CCU | Enhanced CCU |

| Concept | Short-term CO2 cycling via fuels and chemicals | Integrates utilization with storage and carbon neutrality |

| End-of-life fate | CO2 re-emitted | CO2 locked via curing, mineralization, or recapture |

| Hydrogen role | Supplementary reactant | Core link between utilization and storage |

| Storage duration | Weeks-months (temporary) | Years-centuries (durable) |

| Climate mechanism | Avoided fossil use | Combined fossil substitution and durable storage |

| Examples | Urea, methanol, synthetic fuels | Methanol/formic acid (H2 carriers), urea, CO2-cured concrete |

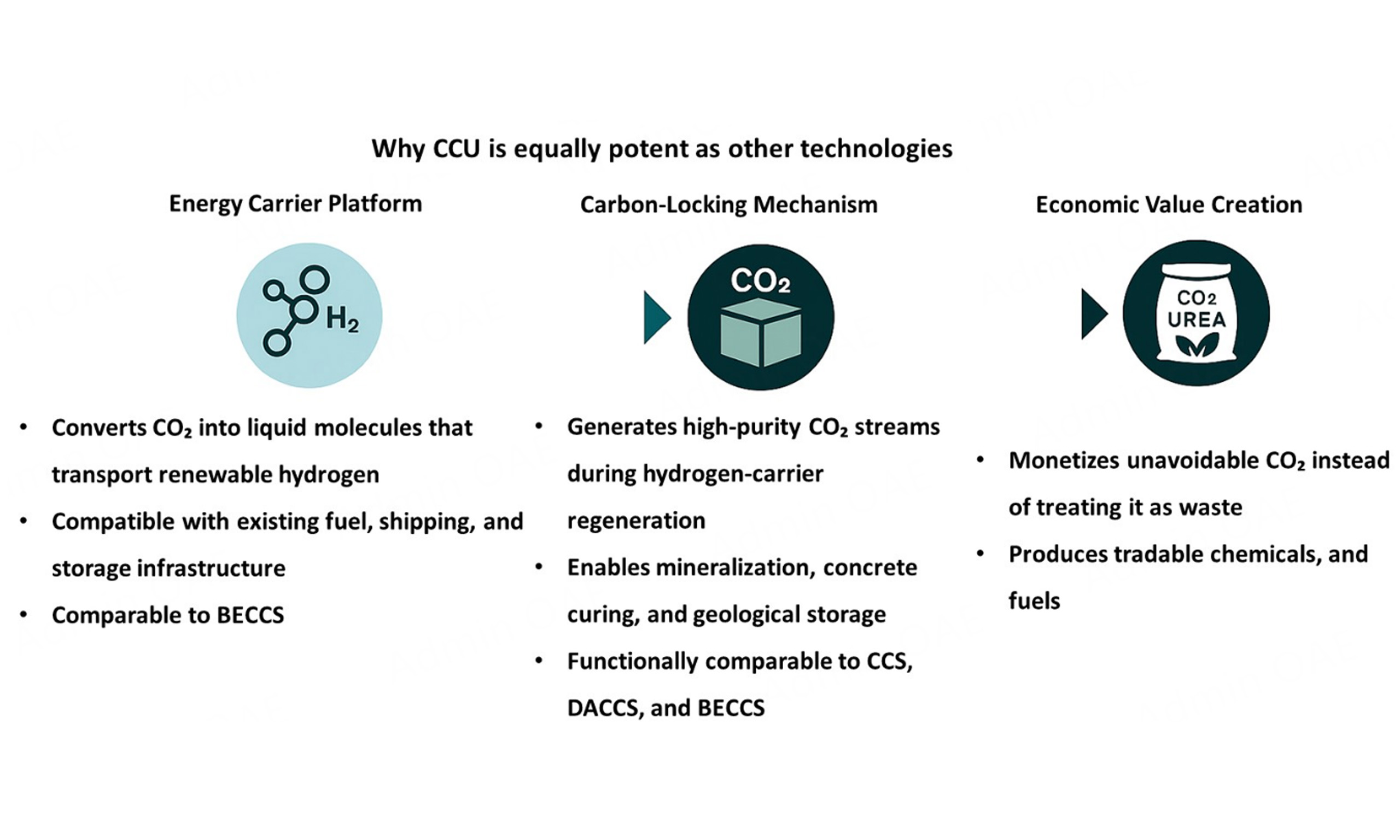

Enhanced CCU occupies a distinct niche within carbon management strategies, neither fully competing with nor replacing CCS, direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS), or bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), but offering complementary pathways suited to specific contexts. Unlike geological CCS, which provides permanent storage but requires dedicated infrastructure and lacks revenue generation, CCU can offset costs through product sales while enabling incremental deployment at smaller scales. However, this economic advantage comes with the trade-off of reduced storage permanence in cycling pathways. DACCS offers the unique advantage of location-independent deployment and direct atmospheric CO2 removal, making it essential for addressing residual emissions and achieving net-negative targets. Despite its potential, DACCS deployment remains constrained by significant technical and economic barriers. Commercial-scale implementation has been achieved by only a single technology, with most approaches still at laboratory or early pilot stages (Technology Readiness Level (TRL) ≤ 6). Current systems demand substantial energy inputs - approximately 1,500 kWh/tCO2 for thermal energy and 500 kWh/tCO2 for electricity - resulting in capture costs between 600-1,000 US dollars per metric ton (USD/tCO2). Achieving climate-relevant scale necessitates major advances in both energy efficiency and cost reduction[9-12]. Enhanced CCU, particularly when paired with biogenic CO2 sources or durable storage pathways, can achieve comparable climate outcomes at lower energy intensity for near-term industrial decarbonization.

BECCS similarly provides net-negative emissions through biogenic CO2 capture and geological storage, but faces constraints from sustainable biomass availability, land-use competition, and water requirements[13,14]. Biogenic-integrated CCU pathways offer a less land-intensive alternative by utilizing existing biogenic CO2 streams (ethanol fermentation, biogas upgrading) without requiring additional biomass cultivation, though at the cost of temporary rather than permanent storage. The strategic value of enhanced CCU lies in three distinct roles: (1) as a transitional bridge enabling immediate emission reductions while permanent storage infrastructure scales, (2) as a hybrid platform where CO2 can be flexibly allocated between utilization and geological storage based on market conditions, and (3) as a value-creation pathway that makes carbon management economically viable for sectors where pure CCS faces financial barriers. Rather than viewing these technologies as competing alternatives, integrated deployment strategies can leverage their complementary strengths. For instance, regional hydrogen-CCU hubs could combine CO2-derived carriers for short-term cycling with geological storage for surplus CO2. At the same time, biogenic CCU could provide carbon-neutral feedstocks for industries where CCS is technically or economically constrained. The key is matching technology choice to permanence requirements, cost constraints, and infrastructure readiness - recognizing that no single approach will achieve net-zero targets alone.

Overview of CO2 management strategies

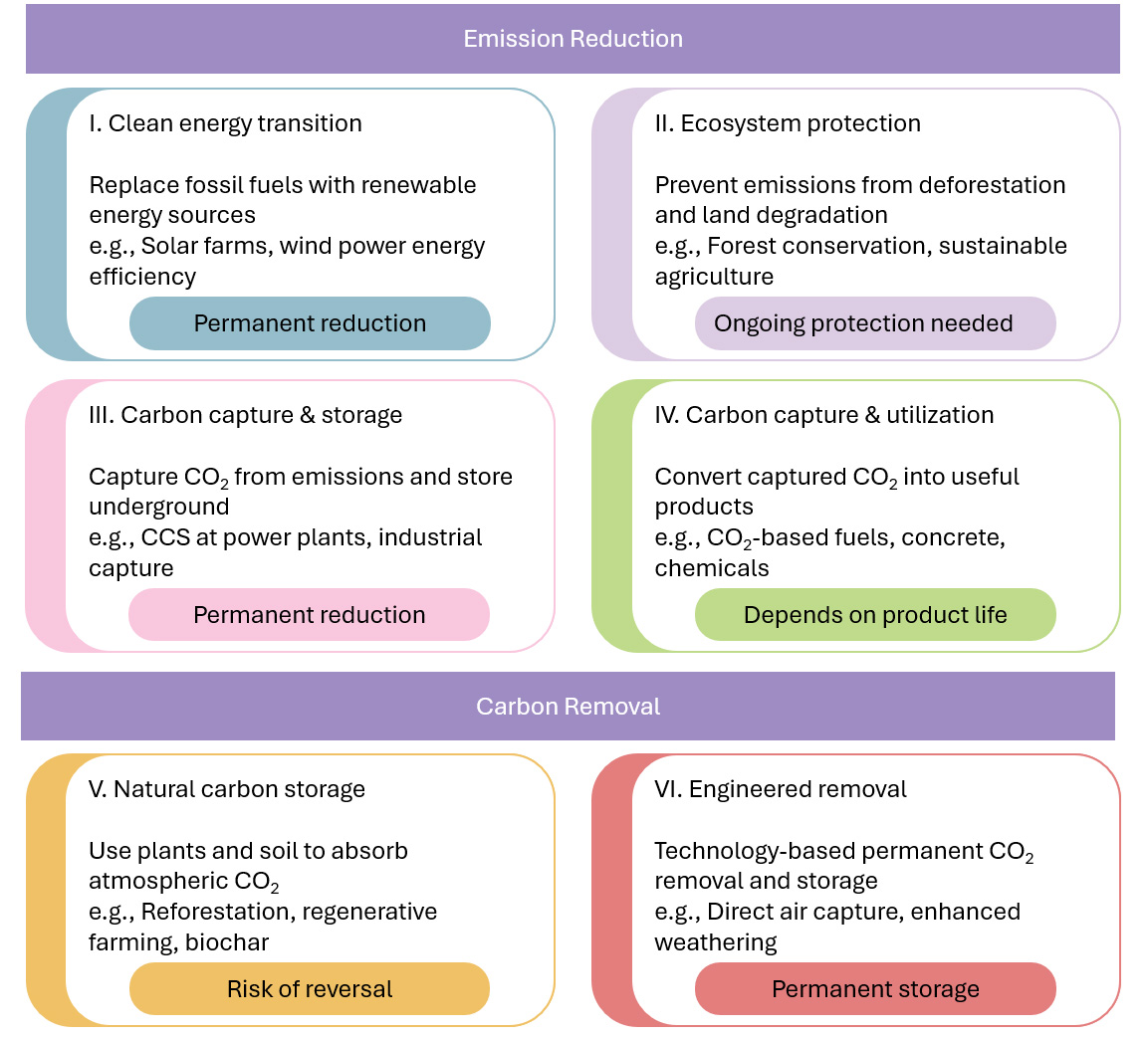

The foundation of effective CO2 mitigation rests on preventing emissions at their point of origin through four interconnected mechanisms. Figure 1 outlines six distinct methods for CO2 reduction and removal, organized into two primary operational domains that target different phases of the carbon mitigation continuum[15].

Figure 1. Approaches to address CO2 emissions through reduction, capture, utilization, and long-term storage, modified from

(1) Clean energy transition systematically replaces fossil fuel infrastructure with renewable energy systems, including solar installations, wind generation, and efficiency optimization protocols. This delivers permanent emission reductions across electricity generation and energy consumption sectors. (2) Ecosystem protection safeguards against emissions from deforestation and terrestrial degradation through forest conservation initiatives and sustainable agricultural practices. (3) CCS intercepts CO2 emissions directly from point sources such as power plants and industrial operations. It sequesters captured carbon in geological formations for millennial timescales while enabling transitional use of existing fossil fuel infrastructure. (4) CCU transforms CO2 into commercially viable products, including synthetic fuels, construction materials, and chemical feedstocks. Storage duration depends on product lifecycle characteristics and ultimate disposal pathways. (5) Natural carbon storage harnesses biological and soil systems to sequester atmospheric CO2 through reforestation programs, regenerative agricultural practices, and biochar deployment. However, inherent reversal risks remain due to environmental disturbances such as wildfires, droughts, or land-use changes. (6) Engineered removal deploys technological solutions for permanent atmospheric CO2 extraction and sequestration, incorporating direct air capture systems and enhanced mineral weathering processes that provide robust storage mechanisms with minimal reversal probability. These six pathways function synergistically within a hierarchical framework, where emission reduction takes precedence over offsetting strategies. Residual emissions require counterbalancing through permanent CO2 removal technologies to achieve authentic net-zero status and establish long-term atmospheric stability. The following sections will examine the potential pathways for CCU development and analyze the global implementation potential, considering technological feasibility, economic viability, and policy frameworks necessary for widespread deployment.

CCU for net-zero emissions

The urgency of deploying CCUS becomes clearer when considering the current state of atmospheric CO2. Global CO2 concentrations reached more than 430 ppm in 2024 - approximately 50% higher than pre-industrial levels - driving record global average temperatures[16]. Total fossil-fuel-related CO2 emissions were approximately 37 gigatonnes (Gt) CO2 in 2023, and when including land-use change, the figure rises to around 41 Gt CO2. Total greenhouse gas emissions reached 57 Gt of CO2 equivalent (CO2-eq) in 2023, representing the highest level on record. Without rapid reductions, these levels are incompatible with limiting warming to 1.5 °C[17,18]. Against this backdrop, the geological storage potential for CCS is immense, estimated to be well over 5,000 Gt of CO2 worldwide, far greater than the cumulative emissions expected this century[19]. Yet, current deployment remains minimal, with global CCS capacity storing just over

Traditional carbon storage methodologies face substantial operational barriers. These include excessive implementation costs, technical limitations, and risks of subsurface CO2 migration from geological repositories. In contrast, CCU technologies offer compelling benefits by transforming captured carbon dioxide into marketable commodities and chemical feedstocks, thereby generating revenue streams that help offset the initial investment in capture. Different conversion technologies exist at various development stages. Some remain in laboratory research phases, while others approach commercial viability according to TRL evaluations[2]. Sustained investment in research and technological advancement remains crucial for thoroughly evaluating the practical implementation potential of novel CO2 transformation processes, establishing their economic sustainability, and scaling successful approaches to industrial magnitudes that can support global decarbonization targets.

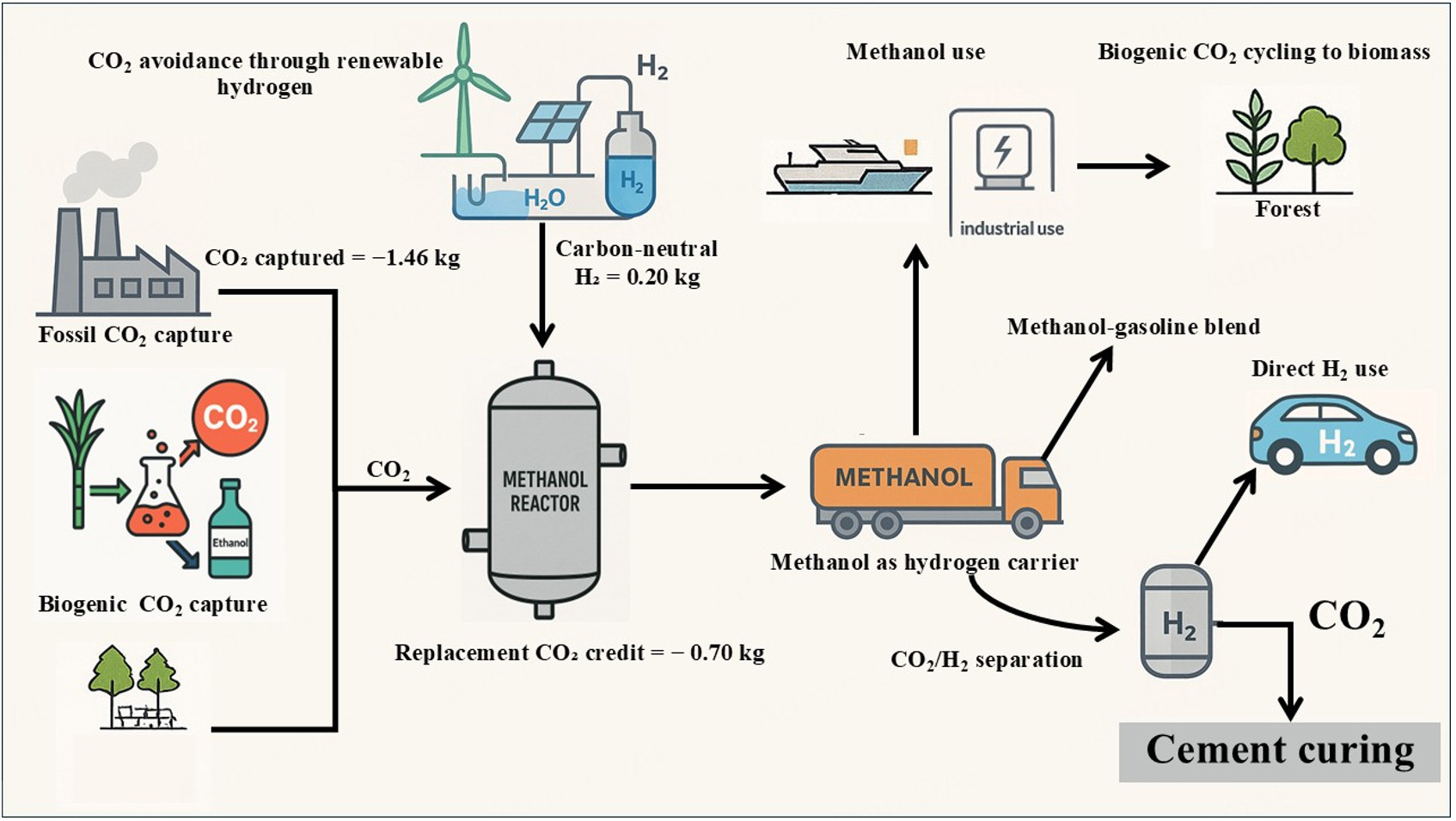

CCU works by intercepting CO2 from large point sources, such as cement kilns, steel mills, or chemical plants, or directly from the atmosphere, and then utilizing it as a feedstock for industrial processes. CO2 can be combined with hydrogen (preferably from renewable electrolysis) to produce fuels, chemicals, and materials. Alternatively, it can react with minerals to form carbonates for use in construction applications. From a life-cycle assessment perspective, CCU can avoid emissions through three mechanisms. First, by diverting CO2 that would otherwise be emitted into the atmosphere, the process reduces point-source emissions. Second, CCU products provide substitution credits when they replace conventional products with higher cradle-to-gate emissions. Third, when CCU processes are powered by renewable energy or utilize low-carbon hydrogen, significant additional emission reductions are achieved by avoiding energy-related emissions. Recent methodological updates stress the importance of accounting for CO2 storage duration and timing. Many earlier assessments did not adequately consider permanence. Urea production exemplifies these benefits. Both conventional and CCU-based or green urea production consume CO2 as feedstock - about 0.73 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of urea. However, conventional urea relies on fossil-derived ammonia and often fossil-derived CO2, making it highly emission-intensive. "Green" urea produced using renewable hydrogen for ammonia and captured CO2 can prevent roughly 2.6 tonnes of CO2 emissions per tonne compared to conventional methods. Since the embedded CO2 returns to the atmosphere during fertilizer application, the net climate benefit is about 1.9 tonnes of CO2 avoided per tonne of urea, primarily from substituting fossil ammonia and preventing direct emissions of captured CO2[2]. As illustrated in Figure 2, CCU can approach true carbon neutrality when paired with biogenic CO2 and renewable hydrogen. Shifting from fossil-derived to biogenic CO2 is particularly important for products with high utilization volumes, such as methanol, since it converts temporary avoidance into genuinely sustainable and climate-neutral pathways.

Figure 2. Conceptual pathways of CO2 utilization from different sources to methanol production and end-use applications. CO2 is captured from fossil-based industrial processes, biogenic emissions from ethanol production, and bioenergy facilities. The captured CO2 is combined with renewable hydrogen to produce methanol, which serves as a chemical feedstock, hydrogen carrier, or input for cement curing, highlighting CCU's role across chemicals, energy, and building materials sectors (Created using Microsoft PowerPoint 365).

Beyond chemical production, CCU products such as methanol or formic acid can also serve as hydrogen carriers, enabling the efficient storage and transportation of renewable hydrogen[23]. In such systems, the CO2 released during hydrogen regeneration does not need to return to the atmosphere; instead, it can be diverted into cement curing and mineralization processes, where it is locked permanently. This integrated approach - utilizing biogenic CO2 for carbon-neutral fuels and chemicals, while capturing and embedding separated CO2 in building materials - offers a pathway to overcome the cycling nature of CCU and achieve lasting climate benefits. Moreover, CCU chemicals can serve as energy carriers. For example, formic acid or methanol functions as an effective hydrogen carrier, replacing fossil-based alternatives while delivering both economic advantages and significant CO2 emission reductions[2,24]. Methanol is produced by hydrogenating CO2, consuming about 1.4 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of methanol. With fossil CO2, the process can avoid approximately 1.95 tonnes of emissions during production; however, when methanol is burned or used, that carbon is fully re-emitted, resulting in a minimal long-term reduction. By contrast, if biogenic CO2 is used, the re-release at use returns carbon that was recently absorbed from the atmosphere. Combined with renewable hydrogen, this enables methanol to function as a nearly carbon-neutral fuel or chemical, offering it greater long-term climate potential than urea[25]. Among the most impactful CCU applications, microalgae-based biodiesel has demonstrated high potential for reducing emissions compared to fossil diesel. Martín and Grossmann (2017)[26] proposed a conceptual design that integrates renewable energy into microalgae cultivation and processing, capable of capturing approximately 4 kg of CO2 for every kilogram of biodiesel produced. Given that cement production contributes approximately 7%-8% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, implementing carbon mineralization and carbonation curing technologies could facilitate the permanent sequestration of 0.39 Gt CO2-eq annually, representing nearly 15% of sectoral emissions[27].

The thermodynamically favorable carbonation reactions not only provide durable carbon storage but also simultaneously enhance the mechanical properties of cementitious matrices, creating a synergistic mechanism that enhances performance. However, large-scale deployment is constrained by energy penalties in capture processes, heterogeneity of carbonatable residues, and supply-demand mismatches for mineralized products. Thus, accelerating research into low-clinker binders, accelerated carbonation curing, and integration of industrial waste streams remains essential to position cement as one of the most scalable and durable CCU pathways.

Beyond cement, broader CCU applications present fundamentally different utilization characteristics and temporal scales. Recently, Ravikumar et al. (2021)[8] assessed 20 CCU pathways and found that only four achieved net climate benefits: two concrete applications involving CO2 mixing and two chemical routes - formic acid via CO2 hydrogenation and carbon monoxide via methane dry reforming. Enhanced oil recovery, while offering immediate economic returns and proven CO2 storage mechanisms, raises questions about net climate benefits when coupled with continued hydrocarbon extraction. Chemical synthesis pathways for platform chemicals and synthetic fuels offer opportunities to displace fossil-derived feedstocks; however, their climate impact depends heavily on the energy source used for CO2 conversion processes. High-value applications in pharmaceuticals and advanced materials, despite limited volume capacity, offer economic incentives that could drive technology development and infrastructure investment. Current research gaps span all sectors but center on fundamental challenges in energy efficiency and process economics. Most CCU pathways currently exhibit unfavorable energy balances, requiring more energy input than they provide in climate benefits. Investigating existing methods from a sustainability perspective remains crucial; yet the question persists: which pathways should be selected for priority development to maximize both climate impact and economic viability. Future research may address sector-specific bottlenecks while maintaining a systems-level perspective. For example, energy and chemical applications require breakthrough catalysts that operate at lower temperatures and pressures. Building materials need accelerated carbonation techniques and waste stream integration strategies. Only through targeted research addressing these specific challenges can CCU transition from a promising concept to a climate-scale deployment. Urea (1.9 kg net benefit) is a strong near-term option, combining high climate benefit even after re-emissions with highly favorable breakeven costs (-982 to 74 USD/tCO2). Biodiesel (2.17 kg) also shows high benefit, but only under high financial support (230-920 USD/tCO2). Bio-methanol varies from low (0.35 kg) under conservative accounting to high (1.9 kg) if biogenic CO2 re-emissions are treated as neutral[25,26,28,29]. Fossil-based methanol (0.35 kg) and tri-reforming methanol (~0) provide limited cycling benefits. In contrast, cement curing and mineralization ensure durable storage, each avoiding ≥ 1.0 kg CO2 per kg used with competitive breakeven costs (-30 to 70 USD/tCO2). CCS achieves permanent storage of ~1.0 kg CO2 per kg injected, with costs of 30-140 USD/tCO2. This places CCS as cost-competitive with the most durable CCU options (curing and mineralization), while shorter-lived CCU products generally require higher support to match this benchmark[2,5]. Table 2 compares CCU pathways with CCS in terms of CO2 avoidance and breakeven costs.

Comparative assessment of CCU and CCS pathways by CO2 use, avoided emissions, net benefit after re-emission, and breakeven cost (USD/tCO2)

| Product | Source of CO2 | Technology | Technology readiness level (TRL) | CO2 use (kg CO2 per kg product) | CO2 avoided (kg CO2 per kg product) | Nature of the benefit after re-emission (avoided − used) | Breakeven cost (USD/tCO2) | References |

| Biodiesel | Fossil gas | Trans-esterification | TRL 5-7 | 1.83 | 4.00 (vs. fossil diesel) | 2.17 → high | 230 to 920 | [26] |

| Urea | Fossil gas | Haber-Bosch | TRL 5-7 | 0.73 | 2.6 | 1.87 ≈ 1.9 → high | −982 to 74 | [2] |

| Bio-methanol | Biogenic CO2 | Hydrogenation | TRL 5-7 | 1.45 | 1.9 | Conservative: 0.35 low (cycling) Short-cycle: ≈1.90 (high) | −327 to 104 | [25,28] |

| Methanol | Fossil gas | Hydrogenation | TRL 5-7 | 1.45 | 1.9 | 0.35 → low (cycling) | −95 to 216 | [7,25,30,31] |

| Methanol | Fossil gas | Tri-reforming | TRL 1-2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | ≈ 0.0 → low (cycling) | 56 to 129 | [25,32,33] |

| CCS | Fossil gas | Compression, transport, injection | TRL 9 | N/A | ≈ 1.00 | High (permanent) | 30 to 140 | [2] |

| Cement curing | Fossil gas | Accelerated CO2 curing | TRL 5-7 | 0.01-0.30 (per kg cement) | ≥ 0.4 (permanently fixed) | High (permanent) | −30 to 70 | [27,33,34] |

| Mineralization | Fossil gas | Direct mineralization/carbonation | TRL 5-7 | 0.10-0.70 (per kg depending on mineral type and processing method | ≥ 1.00 (permanently fixed) | High (permanent) | −30 to 70 | [27,35,36] |

Renewable energy integration necessitates electrochemical energy storage systems to address intermittency and ensure continuous CCU operation. Lithium-ion batteries provide high energy density (150-250 Wh/kg) and efficiency (> 90%), enabling long-duration storage (4-8 h) that buffers daily solar-wind fluctuations and maintains steady-state operation of energy-intensive conversion processes[37,38]. Supercapacitors offer complementary advantages - ultra-fast charge-discharge rates (seconds to minutes) and exceptional cycle life (> 1 million cycles) - making them ideal for managing transient power demands during process startup, load changes, and grid stabilization[39,40]. As CCU scales beyond demonstration plants to industrial deployment

PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT OF CCU PATHWAYS

Carbon neutrality and reduction pathways

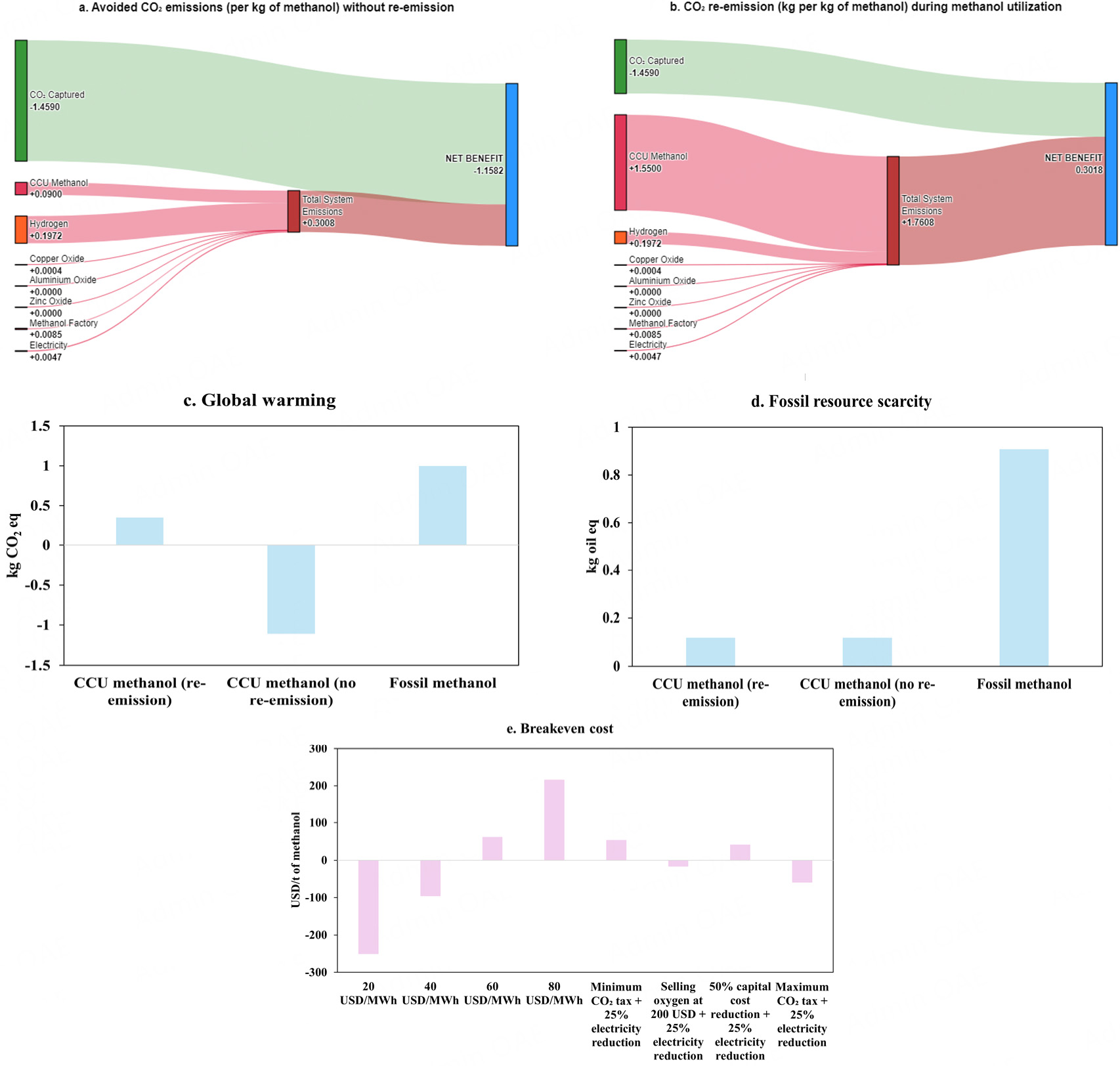

CCU methanol can serve as a carbon-neutral fuel when combusted, as demonstrated by the re-emission scenario (0.35 kg CO2-eq) - substantially lower than fossil methanol (1.00 kg CO2-eq) [Figure 3]. However, the avoided emissions benefit drops significantly when CO2 is released back to the atmosphere compared to production stage avoided emissions (-1.11 kg CO2-eq). Across both impact categories, CCU methanol demonstrates clear environmental advantages. Global warming is reduced by 65%-210% depending on the stage (production vs. use), while fossil resource scarcity decreases by 87% (0.12 vs. 0.91 kg oil-eq). The emission profile shows that CO2 capture (-1.46 kg) dominates the carbon benefit, with hydrogen production (0.20 kg) being the primary emission source. These results confirm that CCU methanol outperforms fossil-based methanol across all utilization pathways, with optimal performance achieved through permanent carbon sequestration applications, such as the reutilization of pure CO2 for cement curing. The breakeven analysis reveals that input cost reduction - particularly electricity prices - is the primary economic driver rather than carbon taxation. At favorable electricity rates (20 USD/MWh), the process achieves profitability (-250 USD breakeven), while at 80 USD/MWh it becomes economically unfeasible (216 USD breakeven). Strategies combining 25% electricity reduction with capital cost optimization or oxygen revenue generation demonstrate greater cost competitiveness than the carbon tax. This indicates that renewable energy costs and electrolyzer efficiency have a greater impact on commercial viability than policy interventions targeting fossil-based product emissions. Consequently, policy mechanisms that directly address feedstock costs - such as Japan's hydrogen contract-for-difference scheme, which subsidizes the price gap between clean and fossil hydrogen - are more effective for CCU deployment than emissions-based instruments such as the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (EU CBAM), which primarily penalize carbon intensity without directly reducing the dominant cost drivers of hydrogen and electricity. These instruments are discussed in Section "Bridging the CCU cost gap", bridging the CCU Cost Gap. In addition, a detailed explanation of the calculation methodology, system boundaries and Supplementary Tables 1-4.

Figure 3. CCU methanol: CO2 avoidance, LCA impacts, and breakeven cost. (A) Avoided CO2 emissions without re-emission consideration; (B) Avoided CO2 emissions with re-emission consideration; (C) Global warming impact; (D) Fossil resource scarcity; (E) Breakeven cost under different incentive scenarios. [(A and B) created using Python 3.12 with matplotlib; (C-E) created using Microsoft Excel 365].

This analysis proposes a methodology for evaluating net life-cycle CO2 emissions in CCU systems by comparing conventional fossil-based production with alternative processes that utilize captured CO2 as feedstock[25]. A key premise is that captured CO2 should not be treated uniformly as a climate benefit; its impact depends on the duration of carbon retention in its final application. The net climate benefit (Net Benefit) is defined as the difference between emissions from conventional (Econv) and alternative (Ealt) production pathways:

where total emissions from conventional production are given by:

and total emissions from alternative CCU production are calculated as:

Here, Econv and Ealt denote the total greenhouse gas emissions from conventional and CCU-based production, respectively (kg CO2-eq). Eprod represents emissions from product manufacturing (fossil-based for conventional systems and renewable-based for CCU systems), Einput refers to emissions associated with material and energy inputs, and Ecaptured represents the effect of captured CO₂, with its sign depending on whether the application results in temporary use or long-term carbon retention.

Proposed Treatment of Captured CO2:

Future studies should carefully consider the sign of Ecaptured based on utilization pathway:

• Negative value (Ecaptured < 0): Long-term sequestration applications (cement curing, mineralization, polymers: 100+ years) where CO2 remains permanently bound

• Positive value (Ecaptured > 0): Short-term release applications (fuels, solvents: days to months) where CO2 returns to atmosphere

For short-term applications, captured CO2 should not be credited as a climate benefit, as the carbon is quickly re-emitted. The primary climate advantage in these cases stems from using renewable energy in production (Eprod), which displaces fossil-based processes. Only in permanent sequestration scenarios - such as cement curing or mineralization - should captured CO2 be treated as a negative emission, representing genuine carbon removal from the atmosphere.

Factors affecting CCU’s environmental performance

The energy intensity of CO2 capture processes strongly influences the performance of CCU systems. Conventional post-combustion amine scrubbing is widely used for retrofitting power plants. It typically requires 380 kWh per tonne of CO2 captured, due to the high heat demand for solvent regeneration and CO2 compression. Direct air capture is attractive for decentralized deployment but far more energy-intensive. This is due to the diluted concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. It requires substantial energy for air handling and sorbent regeneration (about 2,000-3,000 kWh per tonne of carbon dioxide), but improvements in sorbent materials, system efficiency, and renewable energy integration can significantly reduce its environmental and economic burdens. In some cases, CO2 can be used directly from flue gas, such as in microalgae cultivation, avoiding the need for costly purification and thereby reducing upstream energy use. Algae thrive under CO2-enriched conditions, and flue gas injection has been proposed as a low-cost source of carbon. However, impurities such as SOx, NOx, and heavy metals often suppress algal growth and reduce biomass yield, with studies reporting productivity losses of 10%-30% when untreated flue gas is supplied. This trade-off illustrates the balance between reducing energy demand through direct CO2 use and managing potential negative impacts on process performance[41,42]. The selection of conversion technology has a profound influence on the choice of chemical production from CO2. Hydrogenation can achieve commercially viable methanol concentrations at moderate energy demands, whereas electrochemical reduction offers process integration benefits but suffers from prohibitively low yields and extremely high energy consumption. This technological divide determines whether CO2-to-methanol systems evolve into profitable industrial processes or costly environmental burdens, as hydrogenation already delivers product purities suitable for market deployment. At the same time, electrochemical reduction remains commercially unviable due to fundamental efficiency limitations. Hydrogen supply is another decisive factor for CCU performance, particularly in pathways such as methanol and formic acid synthesis. For instance, methanol production requires three moles of H2 per mole of CO2, meaning the environmental footprint of these processes is dominated by the hydrogen source. Conventional “grey” hydrogen from steam methane reforming carries an emissions burden of 9 kg CO2 per kg H2, which can offset the carbon reduction potential of CCU products. In contrast, "green" hydrogen from electrolysis powered by renewables requires approximately 50-55 kWh of electricity per kilogram of H2. When sourced from wind energy, this translates to less than 1 kg CO2 per kg H2, thereby enabling near-carbon-neutral pathways[43]. This difference demonstrates that the climate benefit of CCU is determined mainly by the technology and energy source used for hydrogen production[25,44].

Electricity demand more broadly also plays a pivotal role in CCU feasibility. Beyond hydrogen production, significant amounts of electricity are consumed in CO2 capture, compression, and downstream conversion steps. Life-cycle assessments indicate that when powered by fossil-dominated grids, CCU-based products such as methanol or algal biofuels may have higher greenhouse gas footprints than their conventional fossil counterparts. Conversely, when powered by high shares of renewable electricity, the impacts of global warming can be reduced by up to 80%. This highlights the importance of aligning CCU deployment with the decarbonization of the electricity system. Additional systemic factors also influence CCU performance. For example, heat integration using industrial waste heat can reduce capture energy requirements by 20%-25%, thereby improving overall efficiency[26,31]. While our life-cycle assessment shows that materials and infrastructure contribute only marginally to direct emissions[25], Sahu et al. (2025)[45] emphasize that large-scale Power-to-X deployment will depend heavily on critical minerals such as iridium, nickel, copper, and rare earth elements. These material demands introduce supply chain vulnerabilities, economic constraints, and social risks. Thus, although catalytic materials and infrastructure do not significantly increase the carbon footprint, their availability and ethical sourcing remain decisive for the long-term scalability and sustainability of CCU systems.

Mineral and concrete CO2 utilization is shaped by a combination of technical and environmental factors that influence both the amount of CO2 absorbed and the overall climate benefit. In concrete, the main drivers are the type and amount of binder materials used - such as ordinary portland cement and supplementary cementitious materials - the method of CO2 curing or mixing, and, most importantly, the resulting compressive strength compared to conventional concrete. Because concrete performance is measured by compressive strength, any strength gains from CO2 utilization reduce the binder needed to achieve the same structural performance, thereby enhancing the climate benefit. At the same time, the energy needed for CO2 curing plays a big role - if energy use is too high, it can cancel out the benefits of carbon fixation. For mineralization, the outcome depends on carefully managing process conditions such as CO2 concentration in the source gas (flue gas versus purified CO2), liquid-to-solid ratios, temperature, pressure, reaction time, and gas flow. These parameters control how much CO2 can be locked into the mineral structure and at what rate. The properties of the resulting mineral, including whether it matches or falls short of the strength and functionality of conventional materials, are crucial since lower performance may require additional material use. Ultimately, the climate impact of both pathways goes beyond the amount of CO2 stored. It also reflects the energy demands, material inputs, and functional performance of the end product. Achieving real carbon savings, therefore, depends on optimizing binder mixes, curing methods, and mineralization conditions, while also keeping energy use in check and ensuring the materials perform well for their intended purpose[8].

ECONOMIC BARRIERS AND POLICY SOLUTIONS

Barriers to CCU deployment and widespread adoption

CCU continues to face significant barriers that limit its progression from pilot demonstrations to widespread commercial deployment. Many conversion processes remain energy-intensive, with CO2-to-methanol typically requiring 25-30 gigajoules (GJ) per tonne of CO2 (~90% for H2 electrolysis)[7] and other fuel pathways demanding even higher energy inputs[46]. Their climate benefit therefore depends on access to abundant, low-cost renewable electricity, which remains scarce in most regions and must also support broader decarbonization priorities such as direct electrification and green hydrogen. Technical limitations persist, including catalyst selectivity below 70% and energy-intensive post-reaction separations, while CO2 sources pose additional constraints: most industrial flue gases contain only 5%-25% CO2, and upgrading these dilute streams adds roughly 40-80 USD per tonne to capture costs[47-49]. CCU-derived products remain substantially more expensive than their fossil-based counterparts, with CO2-based methanol costing 800-1,200 USD per tonne compared to 300-500 USD per tonne for conventional methanol, implying a need for carbon prices of roughly 150-300 USD per tonne or targeted subsidy schemes to close the gap. These economic and governance gaps intersect with low public awareness and concerns about “greenwashing,” which weaken the social acceptance needed for siting new facilities[50,51]. Together, these technical, infrastructural, policy, and societal constraints underscore why CCU remains promising yet challenging to scale without coordinated investment, dedicated policy support, and improvements in conversion efficiency and renewable energy availability.

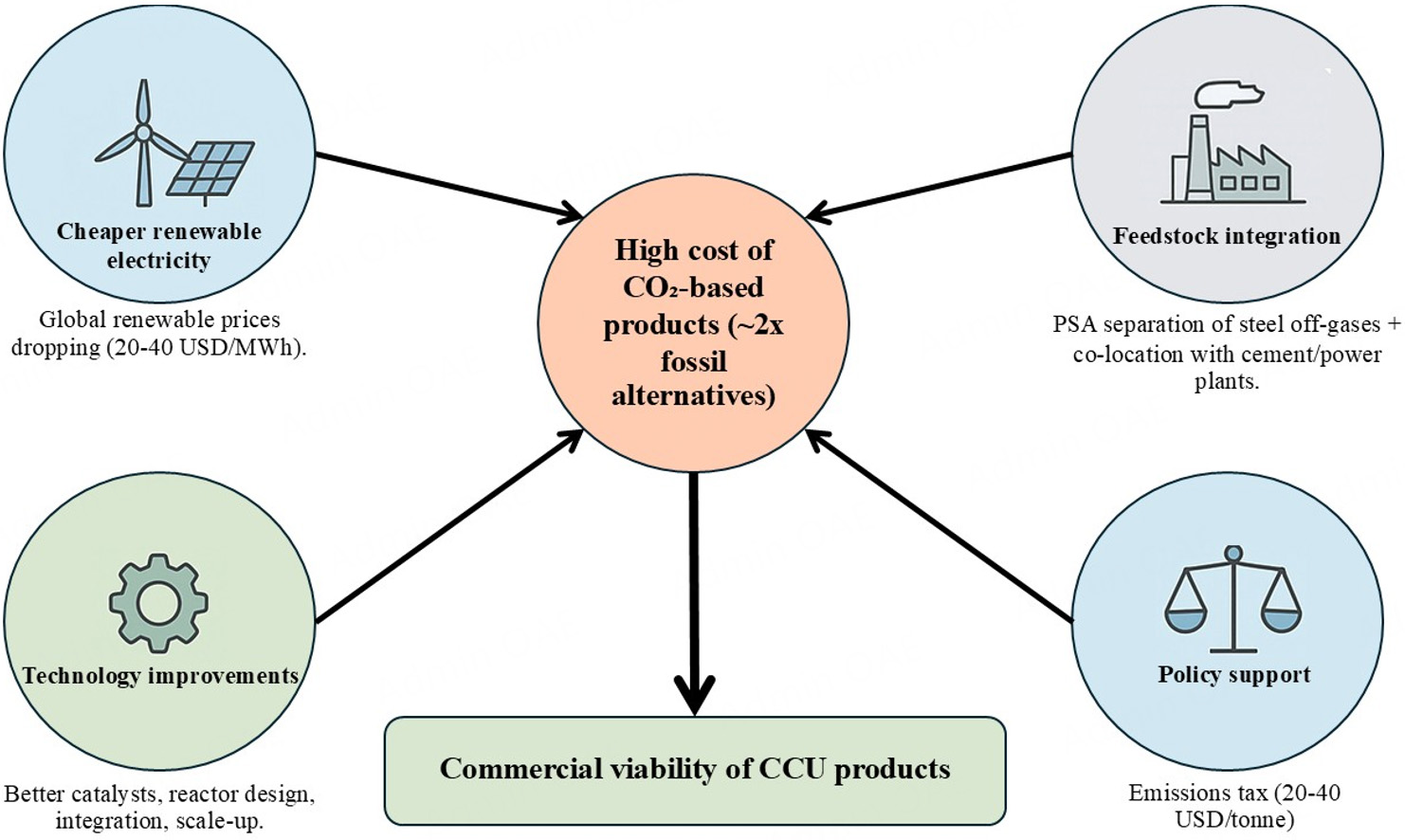

Bridging the CCU cost gap

The cost of CO2-based products is generally higher than that of conventional fossil-based alternatives, often close to double. This price gap is driven by two dominant factors: electricity costs based on local grid mix prices used for hydrogen production and the expense of CO2 capture. Addressing these requires both technological innovation and carefully designed policy support. A central factor in the economics of CCU is electricity, and encouragingly, global renewable electricity prices have already dropped significantly in recent years. If these declining costs are fully leveraged, electricity can be supplied at around half of its current average price. Such a reduction could, on its own, bring CO2-based products much closer to the cost of their conventional counterparts, since electricity accounts for roughly half of the total production costs in many CCU pathways[52,53].

Feedstock integration is especially promising. Steel plants generate off-gases containing CO2, H2, and methane (CH4), which can be efficiently separated through pressure swing adsorption (PSA). Compared to conventional amine scrubbing applied in cement or power plants, PSA requires less energy and simpler infrastructure, making it a far cheaper capture technology. The separated gases not only provide a stream of CO2 for utilization but also yield valuable co-products, such as hydrogen and carbon monoxide, that can be used internally or sold, thereby reducing the net cost of CCU operations[54,55]. Co-locating steel plants with cement or power plants strengthens these synergies. CO2 captured cheaply via PSA can be combined with larger flue-gas streams from adjacent facilities, reducing feedstock costs and eliminating long-distance transport needs. In parallel, advances in catalysts, reactor design, and system integration continue to reduce both energy intensity and capital costs [Figure 4]. As plants scale up, fixed expenditures can be spread across higher production volumes, further lowering the unit cost of CO2-based products. Another way to obtain low-cost CO2 is to produce ethanol via the fermentation of sugar[20]. This process not only provides a low-carbon fuel but also generates a significant stream of high-purity biogenic CO2. Since this CO2 originates from atmospheric carbon fixed by crops, its release is considered climate-neutral. Capturing and utilizing this fermentation-derived CO2 presents an additional opportunity to reduce the already small carbon footprint of sugarcane and corn ethanol, particularly in regions such as Brazil, where best practices and renewable energy inputs are widely adopted. Further assessment of the techno-economic and environmental benefits of this pathway is necessary to fully realize its potential[56].

Figure 4. Pathways to reduce the high cost of CO2-based products and improve CCU competitiveness. (Created using Microsoft PowerPoint 365).

An emission-based carbon tax directly penalizes products in proportion to their carbon intensity. For example, methanol production emits approximately 0.45 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of product. At 300 USD per tonne of CO2, this adds 135 USD to the conventional methanol cost of approximately 400 USD, bringing the total to about 535 USD, which remains below the 750-1,000 USD range for CCU-based methanol. However, urea production emits 2.5 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of product, generating a 750 USD tax burden that creates an excessive cost gap when the initial price difference between green and conventional urea is only 70 USD[2]. This approach yields uneven impacts: high-emission products, such as urea, bear disproportionate penalties, while lower-emission products, such as methanol, experience limited competitive benefits. This unevenness can create sectoral distortions and often requires politically difficult carbon prices to meaningfully shift market competitiveness. An alternative applies a uniform levy directly to fossil-based products based on quantity rather than emissions intensity. This eliminates significant discrepancies between high- and low-emission products, resulting in more straightforward, predictable adjustments. The levy could be set based on the specific cost difference between conventional and CCU alternatives, ensuring cleaner products can compete on a level playing field without extreme price signals[24].

The EU CBAM and the United States Section 45Q tax credit are emissions-linked mechanisms. The EU CBAM ties import costs directly to the embedded emissions at prices set by the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), currently in the range of €50-80 per tonne. The Section 45Q policy in the United States provides tax credits of USD 85 per tonne for geological storage and USD 180 per tonne for direct air capture and storage. Both approaches penalize or reward actions in proportion to carbon intensity. In contrast, Japan’s Green Transformation (GX) hydrogen contract-for-difference scheme does not focus on emissions intensity. Instead, the government pays the direct price gap between fossil-based hydrogen and clean hydrogen, typically in the range of USD 1-5 per kilogram. This ensures predictable cost adjustments without the disproportionate penalties that emissions-based instruments can impose on highly carbon-intensive products such as urea. A different category is represented by Puro.earth, which operates as a third-party certification and marketplace for durable carbon removals. It verifies and issues credits for methods that store carbon for more than 100 years, such as biochar. Puro.earth has been active since 2019 and was central to Microsoft’s landmark deal with Exomad Green to purchase 1.24 million tonnes of certified carbon removal, of which more than 120,000 tonnes have already been delivered. Together, these instruments illustrate two distinct policy logics: one based on emission-intensity pricing signals, which can lead to uneven sectoral impacts, and another based on direct cost equalization, which directly addresses the price gap between conventional and low-carbon products. Overall, for CCU to achieve large-scale deployment, combining these approaches with falling renewable energy costs, feedstock integration, and technology improvements will be essential to close the current cost-price gap[20]. These different policy instruments are vital in enabling CCU to transition from costly pilot systems to viable industrial solutions. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the U.S. Section 45Q tax credit strengthen CCU competitiveness by linking financial incentives directly to CO2 reductions, while Japan’s GX hydrogen contract-for-difference scheme narrows the price gap between fossil and clean hydrogen, accelerating hydrogen-based CCU pathways such as methanol and formic acid. Meanwhile, certification markets such as Puro.earth promote long-term carbon storage and reward durability. Together, these complementary policies - carbon pricing, cost-gap subsidies, and certification mechanisms - create the financial foundation for scaling CCU deployment and integrating it into national and global decarbonization strategies [Table 3].

Key policies and market instruments addressing carbon capture, utilization, and removal through emissions pricing, cost-gap subsidies, and certification schemes

| Policy | Core mechanism | Financial scale | Timeline | Coverage/targets | References |

| EU CBAM | Importers buy certificates equal to embedded CO2, priced at EU ETS rates | CO2 based on EU ETS prices (~€50-80 €/tonne) | 2021-2025 (transitional), 2026 (full implementation) | 6 sectors initially, expanding to all EU ETS sectors by 2030 | [57] |

| U.S. 45Q | Tax credit per tonne CO2 stored/used | USD 85/tonne (storage/used), USD 180/tonne (direct air capture) | Active since 2008; Enhanced 2018 & 2022; Construction deadline 2032; Credits available for 12 years post-commissioning | 45Q has no cap; net-zero needs ~1.8 Gt CO2/year, 1,000+ facilities | [58,59] |

| Japan GX H2 CfD | Government pays cost gap between clean and fossil hydrogen | ~USD 1-5/kg-H2 subsidy to fill cost gap | Japan targets clean hydrogen at ~USD 2.2/kg by 2030 and ~USD 1.5/kg by 2050 | 20 million tonnes H2/year by 2050 | [60] |

| Puro.earth Standard | Third-party certification & issuance of durable CO2 removal credits (100+ years) | Microsoft-Exomad Green: 1.24 million tonnes deal; >120,000 t already delivered | Operational since 2019; scaling to 1 million tonne/year by 2027 | Certified removals; Exomad Green ~27% durable CDR market share | [61] |

On the other hand, cement curing with CO2 is one of the most economically promising and climate-beneficial CCU pathways. It is already close to cost-competitive and has large-scale CO2 storage potential. The main challenges are technical (strength consistency), regulatory adoption, and the emissions from cement calcination. If coupled with low-carbon energy, CO2 curing could be a cornerstone CCU solution[8,27].

The prospects for CCU are becoming increasingly robust as renewable electricity, green hydrogen, and CO2-derived methanol move toward cost-competitiveness and large-scale deployment. Between 2010 and 2023, the global weighted average levelized cost of electricity for utility-scale solar photovoltaic (PV) declined by about 90% to 0.044 USD/kWh, while that of onshore wind decreased by approximately 70% to

While CCU represents a smaller fraction of total CCUS capacity, its strategic value extends beyond volume metrics through its ability to create permanent carbon locks and prevent future emissions. CCU applications offer multiple pathways for durable carbon management: converting CO2 into essential chemicals such as urea and methanol displaces fossil-based production, utilizing CO2 as a hydrogen carrier enables clean energy transport and storage, and embedding CO2 in cement and building materials creates permanent sequestration within infrastructure. These diverse applications collectively establish robust carbon utilization networks that not only avoid emissions from conventional production but also lock carbon away from the atmosphere for extended periods. Rather than viewing CCU as a marginal complement to storage, this perspective positions it as a strategic multiplier that transforms CO2 from waste into valuable resources while simultaneously achieving permanent emission reductions across multiple industrial sectors [Table 4].

Renewables and CCU prospects in net-zero pathway

| Year | Renewable electricity | Green H2 (electrolysis) | Methanol cost | Global methanol capacity | References |

| 2030 | Wind + solar ≈ 30% of global electricity | < 2 USD/kg in best-resource regions; 5-8 €/kg in Central Europe (regional variance) | 700-800 USD/t | 41 million tonne/year (announced projects) | [62,65-68] |

| 2050 | Renewables ≈ 90% of global electricity, with solar + wind ≈ 70% | 1-2 USD/kg achievable in resource-rich regions (with CAPEX ~130-307 USD/kW) | 370-400 USD/t | 385 million tonne/year | [62,69,70] |

CONCLUSIONS

This perspective redefines CCU by introducing an enhanced framework that distinguishes cycling, biogenic-integrated, and durable-storage pathways. To support consistent evaluation, we propose a net climate-benefit assessment approach in which captured emissions are treated according to storage duration - negative for permanent sequestration and positive for short-cycle applications. When integrated with hydrogen carriers and cement-based storage under unified life-cycle assessment, CCU can evolve from a transitional technology into a strategic bridge linking emission reduction with long-term carbon removal.

Actionable pathways

• Integrated infrastructure: Deploy regional hydrogen-CCU hubs that co-locate electrolysis, conversion, and regeneration to improve efficiency and enable cascading utilization pathways.

• Standardized assessment: Develop temporal LCA frameworks that quantify storage duration and enable consistent benchmarking of CCU against CCS, DACCS, and BECCS in terms of permanence, cost, and scalability.

• Industrial symbiosis: Co-locate CCU with high-purity biogenic CO2 sources and create hybrid CCU-CCS systems allowing flexible allocation between utilization and geological storage.

• Policy innovation: Prioritize feedstock-based subsidies over emissions-only pricing and implement tiered incentives rewarding both utilization and verified permanent storage.

• Technology development: Focus on low-energy catalysts, improved reactor designs, and integrated models identifying least-cost regional solutions with transparent certification frameworks.

The next decade will determine whether CCU remains peripheral or becomes central to industrial decarbonization. Success depends on connecting hydrogen infrastructure, implementing standardized temporal assessment, and deploying effective policy mechanisms that transform CO2 from an environmental liability into a managed resource within a circular carbon economy.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT), the Joint Graduate School of Energy and Environment (JGSEE), and the Center of Excellence on Energy Technology and Environment for their support.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing - review & editing: Rafiq, A.; Gheewala, S. H.

Data acquisition, writing - original draft: Rafiq, A.

Supervision: Gheewala, S. H.

Availability of data and materials

Data and Supplementary Materials are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Gabrielli, P.; Gazzani, M.; Mazzotti, M. The role of carbon capture and utilization, carbon capture and storage, and biomass to enable a net-zero-CO2 emissions chemical industry. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 7033-45.

2. Rafiq, A.; Ren, J.; Laosiripojana, N.; Silalertruksa, T.; Gheewala, S. H. Life cycle environmental and economic viability analysis of CO2 utilization for chemical production in the cement sector. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2025, 58, 364-84.

3. Do, T. N.; Kim, J. Green C2-C4 hydrocarbon production through direct CO2 hydrogenation with renewable hydrogen: Process development and techno-economic analysis. Energy. Convers. Manag. 2020, 214, 112866.

4. International Energy Agency. CCUS projects around the world are reaching new milestones, 2025. Available from: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/ccus-projects-around-the-world-are-reaching-new-milestones [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

5. Hepburn, C.; Adlen, E.; Beddington, J.; et al. The technological and economic prospects for CO2 utilization and removal. Nature 2019, 575, 87-97.

6. Nyqvist, E.; Baumann, H.; Shavalieva, G.; Janssen, M. Methodological review of life cycle assessments of carbon capture and utilisation - Does modelling reflect purposes? Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 18, 100291.

7. Win, S. Y.; Opaprakasit, P.; Papong, S. Environmental and economic assessment of carbon capture and utilization at coal-fired power plant in Thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137595.

8. Ravikumar, D.; Keoleian, G. A.; Miller, S. A.; Sick, V. Assessing the relative climate impact of carbon utilization for concrete, chemical, and mineral production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 12019-31.

9. Deutz, S.; Bardow, A. Life-cycle assessment of an industrial direct air capture process based on temperature-vacuum swing adsorption. Nat. Energy. 2021, 6, 203-13.

10. Bui, M.; Adjiman, C. S.; Bardow, A.; et al. Carbon capture and storage (CCS): the way forward. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1062-176.

11. International Energy Agency. Direct air capture - a key technology for net zero. Available from: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/78633715-15c0-44e1-81df-41123c556d57/DirectAirCapture_Akeytechnologyfornetzero.pdf [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

12. International Energy Agency. Direct air capture 2022: a key technology for net zero, 2022. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/direct-air-capture-2022 [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

13. Braun, J.; Werner, C.; Gerten, D.; Stenzel, F.; Schaphoff, S.; Lucht, W. Multiple planetary boundaries preclude biomass crops for carbon capture and storage outside of agricultural areas. Commun. Earth. Environ. 2025, 6, 2033.

14. Stenzel, F.; Greve, P.; Lucht, W.; Tramberend, S.; Wada, Y.; Gerten, D. Irrigation of biomass plantations may globally increase water stress more than climate change. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1512.

15. Johnstone, I.; Allen, M.; Axelsson, K.; et al. The revised oxford principles for net zero aligned carbon offsetting. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 091005.

16. NASA. Carbon dioxide - earth indicator, 2025. Available from: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide/?intent=121 [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

17. Lei, T.; Wang, D.; Yu, X.; et al. Global iron and steel plant CO2 emissions and carbon-neutrality pathways. Nature 2023, 622, 514-20.

18. Global Carbon Project. Fossil CO2 emissions at record high in 2023. Available from: https://globalcarbonbudget.org/fossil-co2-emissions-at-record-high-in-2023/ [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

19. Zhang, Y.; Jackson, C.; Krevor, S. The feasibility of reaching gigatonne scale CO2 storage by mid-century. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6913.

20. International Energy Agency. Putting CO2 to use, 2019. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/putting-co2-to-use?utm [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

21. International Energy Agency. CO2 transport and storage, 2025. Available from: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/carbon-capture-utilisation-and-storage/co2-transport-and-storage [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

22. World Resources Institute. 7 things to know about carbon capture, utilization and sequestration. Washington, DC: WRI, 2025. Available from: https://www.wri.org/insights/carbon-capture-technology [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

23. Kim, C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.; Lee, U.; Kim, K. Economic and environmental potential of green hydrogen carriers (GHCs) produced via reduction of amine-captured CO2. Energy. Convers. Manag. 2023, 291, 117302.

24. Rafiq, A. Exploring the potential of CO2-derived bulk materials industries in Thailand: life cycle assessment and market feasibility. Ph.D. Dissertation, the Joint Graduate School of Energy and Environment, King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi, Thailand, 2025.

25. Rafiq, A.; Farooq, A.; Gheewala, S. H. Life cycle assessment of CO2-based and conventional methanol production pathways in Thailand. Processes 2024, 12, 1868.

26. Martín, M.; Grossmann, I. E. Optimal integration of a self sustained algae based facility with solar and/or wind energy. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 336-47.

27. Driver, J. G.; Bernard, E.; Patrizio, P.; Fennell, P. S.; Scrivener, K.; Myers, R. J. Global decarbonization potential of CO2 mineralization in concrete materials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2024, 121, e2313475121.

28. Tariq, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, M. Techno-economic and life cycle assessment of integrated bio- and e-methanol production from biomass with carbon capture and utilization. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163850.

29. Restrepo-valencia, S.; Capaz, R. S.; Ortiz, P. S. Waste biogenic carbon to alternative methanol production: A comprehensive analysis for ethanol distilleries. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 495, 145019.

30. Khojasteh-salkuyeh, Y.; Ashrafi, O.; Mostafavi, E.; Navarri, P. CO2 utilization for methanol production; Part I: process design and life cycle GHG assessment of different pathways. J. CO2. Util. 2021, 50, 101608.

31. Sarp, S.; Gonzalez, Hernandez. S.; Chen, C.; Sheehan, S. W. Alcohol production from carbon dioxide: methanol as a fuel and chemical feedstock. Joule 2021, 5, 59-76.

32. Shi, C.; Labbaf, B.; Mostafavi, E.; Mahinpey, N. Methanol production from water electrolysis and tri-reforming: Process design and technical-economic analysis. J. CO2. Util. 2020, 38, 241-51.

33. Suescum-Morales, D.; Fernández-Ledesma, E.; González-Caro, Á.; Merino-Lechuga, A. M.; Fernández-Rodríguez, J. M.; Jiménez, J. R. Carbon emission evaluation of CO2 curing in vibro-compacted precast concrete made with recycled aggregates. Materials 2023, 16, 2436.

34. Fu, X.; Guerini, A.; Zampini, D.; Rotta, Loria. A. F. Storing CO2 while strengthening concrete by carbonating its cement in suspension. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 546.

35. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Negative emissions technologies and reliable sequestration: a research agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019.

36. Sick, V.; Stokes, G.; Mason, F. C. CO2 utilization and market size projection for CO2-treated construction materials. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 878756.

37. Wang, Q.; He, Y.; Shen, J.; Hu, X.; Ma, Z. State of charge-dependent polynomial equivalent circuit modeling for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE. Trans. Power. Electron. 2018, 33, 8449-60.

38. Ravi, A.; Rajkumar, J. K.; Perumal, A. P. P. T.; et al. Energy storage systems - energizing the future: a review. E3S. Web. Conf. 2025, 611, 05004.

39. Catelani, M.; Ciani, L.; Corti, F.; et al. Experimental characterization of hybrid supercapacitor under different operating conditions using EIS measurements. IEEE. Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1-10.

40. Dong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. A survey of battery-supercapacitor hybrid energy storage systems: concept, topology, control and application. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1085.

41. Ozkan, M. Atmospheric alchemy: the energy and cost dynamics of direct air carbon capture. MRS. Energy. Sustain. 2025, 12, 46-61.

42. Rafiq, A.; Morris, C.; Schudel, A.; Gheewala, S. Life cycle assessment of microalgae-based products for carbon dioxide utilization in Thailand: biofertilizer, fish feed, and biodiesel. F1000Research 2025, 13, 1503.

43. Patel, G. H.; Havukainen, J.; Horttanainen, M.; Soukka, R.; Tuomaala, M. Climate change performance of hydrogen production based on life cycle assessment. Green. Chem. 2024, 26, 992-1006.

44. Consonni, S.; Mastropasqua, L.; Spinelli, M.; Barckholtz, T. A.; Campanari, S. Low-carbon hydrogen via integration of steam methane reforming with molten carbonate fuel cells at low fuel utilization. Adv. Appl. Energy. 2021, 2, 100010.

45. Sahu, A. K.; Rufford, T. E.; Ali, S. H.; et al. Material needs for power-to-X systems for CO2 utilization require a life cycle approach. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 5819-35.

46. Farajzadeh, R.; Khoshnevis, N.; Solomon, D.; Masalmeh, S.; Bruining, J. Life-cycle assessment of oil recovery using dimethyl ether produced from green hydrogen and captured CO2. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4027.

47. Agbejule, A.; Sempron-Namuag, P. A bibliometric analysis of carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS): identifying barriers and drivers. Appl. Energy. 2025, 400, 126604.

48. International Energy Agency. Developing a research agenda for carbon dioxide removal and reliable sequestration, 2023. Available from: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/is-carbon-capture-too-expensive [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

49. Hu, J.; Cai, Y.; Xie, J.; Hou, D.; Yu, L.; Deng, D. Selectivity control in CO2 hydrogenation to one-carbon products. Chem 2024, 10, 1084-117.

50. Faber, G.; Sick, V. Identifying and mitigating greenwashing of carbon utilization products; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2022. Available from: https://backend.production.deepblue-documents.lib.umich.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/3f1fa91a-a844-4dc4-84c6-9d77d398e157/content [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

51. Jones, C. R.; Olfe-Kräutlein, B.; Naims, H.; Armstrong, K. The social acceptance of carbon dioxide utilisation: a review and research agenda. Front. Energy. Res. 2017, 5, 11.

52. Wang, P.; Robinson, A. J.; Papadokonstantakis, S. Prospective techno-economic and life cycle assessment: a review across established and emerging carbon capture, storage and utilization (CCS/CCU) technologies. Front. Energy. Res. 2024, 12, 1412770.

53. Oil and Gas Climate Initiative; Boston Consulting Group. Carbon capture and utilization as a decarbonization lever. White Paper, 2024. Available from: https://www.ogci.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/CCU-Report-vf.pdf [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

54. Kleinekorte, J.; Leitl, M.; Zibunas, C.; Bardow, A. What shall we do with steel mill off-gas: polygeneration systems minimizing greenhouse gas emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 13294-304.

55. Porter, R. T.; Cobden, P. D.; Mahgerefteh, H. Novel process design and techno-economic simulation of methanol synthesis from blast furnace gas in an integrated steelworks CCUS system. J. CO2. Util. 2022, 66, 102278.

56. Silva, J. F. L.; Souza, G. M.; Filho, R. M.; Yang, Y.; Li, F. Case studies of CO2 utilization in the production of ethanol: overview of costs and greenhouse gas emissions; IEA Bioenergy: Task 39, 2024. Available from: https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Case-studies-of-CO2-utilization-in-the-production-of-ethanol.pdf [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

57. Climate Change Advisory Council Secretariat. EU's carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) fact sheet. Dublin, Ireland: Climate Change Advisory Council Secretariat, 2025. Available from: https://www.climatecouncil.ie/councilpublications/secretariatfactsheets/ [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

58. Carbon Capture Coalition. Primer: 45Q Tax Credit for Carbon Capture Projects, 2025. Available from: https://carboncapturecoalition.org/resource/45q-tax-credit-for-carbon-capture-projects [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

59. Moch, J. M.; Xue, W.; Holdren, J. P. Carbon capture, utilization, and storage: technologies and costs in the U.S. context. 2022. Available from: https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/carbon-capture-utilization-and-storage-technologies-and-costs-us-context [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

60. Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. Overview of basic hydrogen strategy, Government of Japan, 2023. Available from: https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/enecho/shoene_shinene/suiso_seisaku/pdf/20230606_4.pdf [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

61. Williment, C. Microsoft & exomad green: the world's largest carbon removal. Sustainability Magazine, 2025. Available from: https://sustainabilitymag.com/articles/microsoft-exomad-green-the-worlds-largest-carbon-removal?utm_source [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

62. Fasihi, M.; Breyer, C. Global production potential of green methanol based on variable renewable electricity. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 3503-22.

63. Pio, D.; Vilas-Boas, A.; Rodrigues, N.; Mendes, A. Carbon neutral methanol from pulp mills towards full energy decarbonization: an inside perspective and critical review. Green. Chem. 2022, 24, 5403-28.

64. Energy Transitions Commission. Carbon capture, utilisation and storage in the energy transition: vital but limited, 2022. Available from: https://www.energy-transitions.org/publications/carbon-capture-use-storage-vital-but-limited/ [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

65. International Energy Agency. Massive global growth of renewables to 2030 is set to match entire power capacity of major economies today, moving world closer to tripling goal, 2024. Available from: https://www.iea.org/news/massive-global-growth-of-renewables-to-2030-is-set-to-match-entire-power-capacity-of-major-economies-today-moving-world-closer-to-tripling-goal [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

66. Algburi, S.; Munther, H.; Al-Dulaimi, O.; et al. Green hydrogen role in sustainable energy transformations: a review. Results. Eng. 2025, 26, 105109.

67. Bioenergy International. New data shows growing renewable and low-carbon methanol project pipeline; 2025. Available from: https://bioenergyinternational.com/new-data-shows-growing-renewable-and-low-carbon-methanol-project-pipeline/ [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

68. Hazenberg, W. Green hydrogen: cost and reduction potential, 2024. Available from: https://greenskillsforhydrogen.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/2024-Juni-4-V03-Masterclass-WHB_-Greenskill4h2_Green-Hydrogen-Cost-and-reduction.pdf [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

69. International Energy Agency. Net zero by 2050: a roadmap for the global energy sector, 2021. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050 [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].