Artificial intelligence and EEG during anesthesia: ideal match or fleeting bond?

Abstract

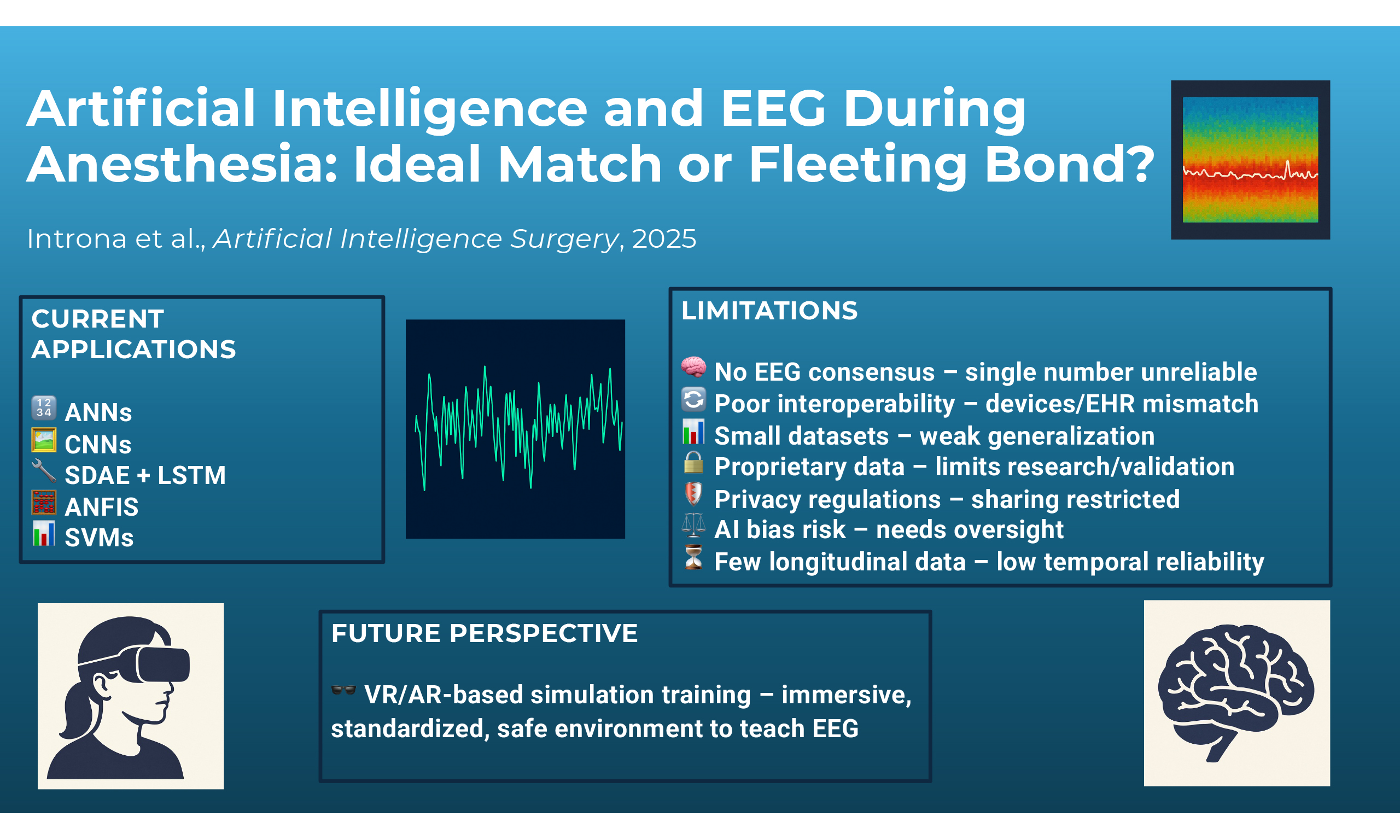

Artificial intelligence (AI) has shown considerable potential in perioperative monitoring, particularly in its application to electroencephalogram (EEG) analysis for assessing the depth of anesthesia. AI methods may enable the dynamic recognition of complex time-frequency EEG patterns and the adaptation of monitoring strategies to patient-specific brain responses. Convolutional neural networks, artificial neural networks, and hybrid deep learning models have reported encouraging results in detecting anesthetic states, estimating bispectral index values, and identifying relevant EEG features - such as alpha-delta shifts or burst suppression - without relying on manual feature engineering. Parallel efforts using virtual and augmented reality platforms suggest possible benefits for anesthesiologist training in EEG interpretation and pharmacologic titration. Despite these advances, important limitations constrain clinical translation. A major challenge is the absence of standardized EEG pattern definitions across anesthetic agents and patient groups, limiting model generalizability. Restricted interoperability between EEG monitors and electronic health records, coupled with proprietary data formats, reduces access to raw EEG signals and hampers large-scale development. Privacy and governance requirements add further barriers to data integration. Methodologically, many studies are affected by insufficient internal validation, suboptimal reporting, and testing in experimental rather than real-world conditions, reducing their translational value. While AI could eventually improve anesthetic precision and safety through EEG-guided approaches, realizing this potential will require transparent algorithms, multicenter and heterogeneous datasets, and robust interoperability and data-sharing standards. Only through such coordinated efforts can these tools evolve from promising research applications into reliable components of routine anesthetic care.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Traditional methods of monitoring the depth of anesthesia (DoA) rely on subjective clinical assessments and basic physiological measures [blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), drug dosage and concentrations]. These approaches can be inconsistent due to patient variability and the differing effects of anesthetic drugs, sometimes leading to inaccurate evaluations[1]. With technological advancements, it has become possible to bring into the operating room and other complex settings a way to transduce electroencephalogram (EEG) signals, providing clinicians with user-friendly interfaces for real-time monitoring.

Processed electroencephalogram (pEEG) monitors acquire, filter, and analyze raw EEG signals as waveform voltage potentials from the cerebral cortex, for applications in anesthesia, intensive care unit (ICU) sedation, brain-computer interfaces, and other forms of neuromonitoring[2]. The EEG waveform potentials can be further analyzed by transforming from the time domain to the frequency domain, using Fourier Transform, and into digital data using discrete Fourier transform (DFT)[3]. Fourier transform of EEG data can be graphically displayed by plotting signal power versus frequency. The epoch-based signal analysis and transformation, such as the Welch periodogram, also yield the power spectral density (PSD) for each frequency band. The power and frequency spectrum can, in addition, be extended over the time domain and color-coded to depict the intensity of signal power in frequency bands of clinical interest, termed the density spectral array (DSA) or spectrogram[4].

The transformation of unprocessed EEG signal data can be categorized using mathematical techniques as higher-order derivatives of the raw EEG signals[3,5]. The mean and variance of the EEG signal amplitude represent first-order statistics, while the power spectrum and bispectrum of the EEG signal represent second- and third-order statistics, respectively[6].

EEG signal processing may reveal distinct, discrete changes or drug signatures based on the level of sedation or general anesthesia and the type of drug used for the induction and maintenance of anesthesia. Color-coded DSA facilitates visual recognition of increased PSD in characteristic frequency bands of interest[7]. For example, during the maintenance phase of anesthesia, propofol produces the ‘alpha-delta’ pattern - high-power red-color bands in a slow alpha (8-12 Hz)-delta (0-4 Hz) pattern. Volatile anesthetics, such as Sevoflurane, generate a ‘theta-fill’ pattern - with additional theta (4-8 Hz) band saturation. Ketamine is associated with a high ‘beta-gamma’ (25-30 Hz) pattern with irregular slow oscillations. Dexmedetomidine is associated with ‘loss of alpha’ band power and the natural sleep-like slow ‘delta-spindle’ oscillations[4].

These visual signatures also have underlying mathematical signatures that can be used for automated analyses. The time-discrete derivatives of raw EEG signals, such as differential PSD (diffPSD), may show increased alpha-delta ratios compared to standard PSD analysis[5]. These derivatives may enable better visual and automated recognition of changes in the alpha band. Relative loss of alpha band power during maintenance of anesthesia, compared to the baseline EEG, may be associated with postoperative delirium and cognitive decline[8,9]. It may aid in the identification of the ‘vulnerable brain’ prone to post-anesthesia neurocognitive decline[10].

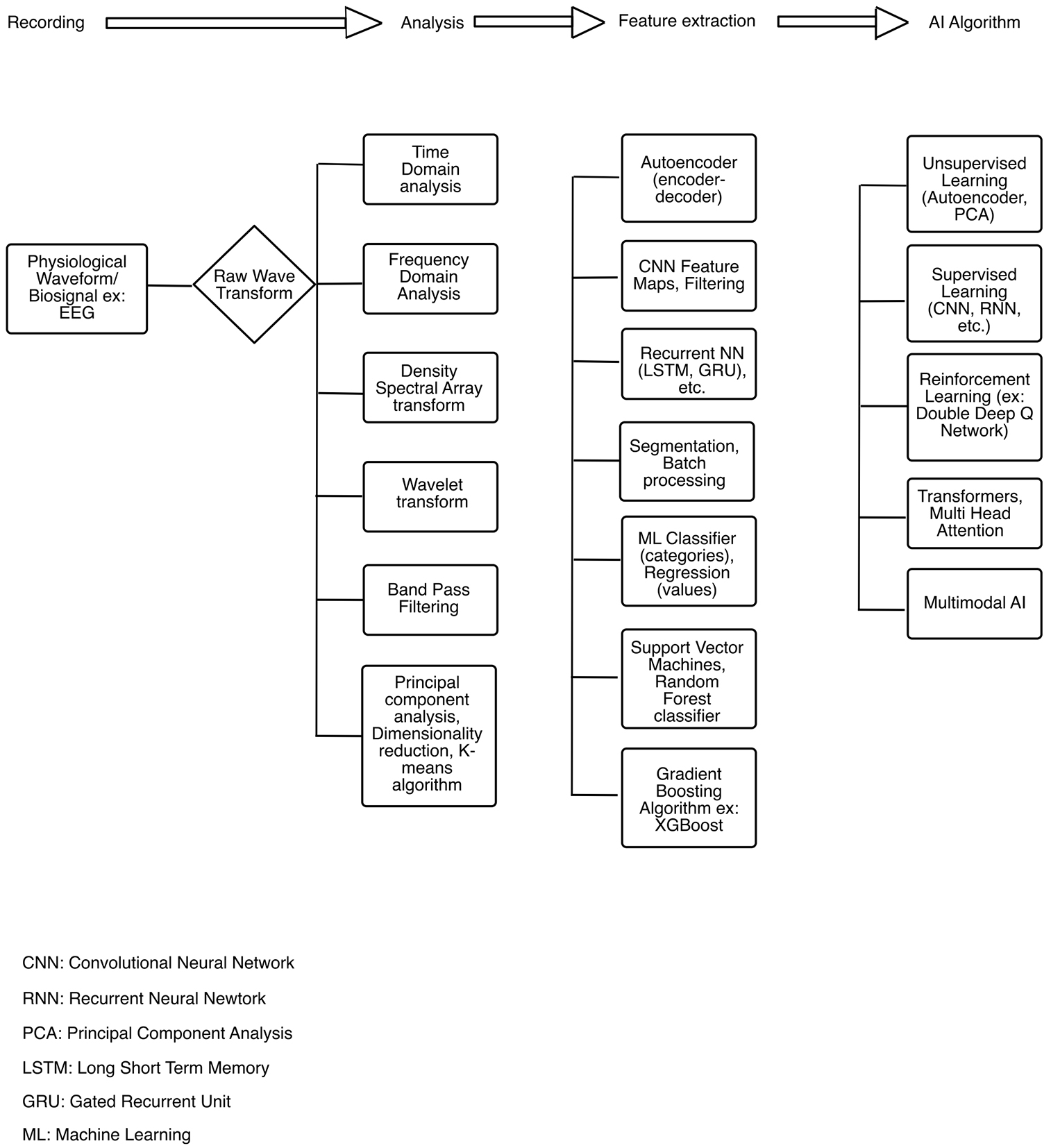

Raw EEG signal waveforms can be transformed and analyzed with various conventional signal processing techniques, such as time domain and frequency domain transformation and DSA (color-coded spectrograms). In addition, principal component analyses, feature extraction with machine learning (ML) algorithms, and further processing using supervised or unsupervised learning techniques may be used [Figure 1][11-13]. Data-driven decomposition of EEG in the field of ML, deep learning (DL), and artificial intelligence (AI) is based on the mathematical principles of transforming scalar data into vectors and tensors. Scalar data represent magnitude-only data, while vectors or a first-order tensor in ML (unlike its physics counterpart) denotes multiple scalars of the same type of data[14]. Tensors, which form the basis of modern ML and AI applications, represent an n-dimensional array of numbers. The dimensions in vectors and tensors represent the individual features of the data and not the features of physical space[15]. The complex EEG signal has multiple features in amplitude, power, phase, time, frequency, entropy, and other higher-order derivatives that may be amenable to ML data representation techniques such as tensors and vector embeddings[16-18].

Figure 1. EEG signal analyses, transformation and processing with machine learning algorithms. EEG: Electroencephalogram.

A technique used in ML and DL for identifying features in visual data is the convolutional neural network (CNN)[15,19,20]. DL using CNNs has been applied in cutting-edge areas such as self-driving cars and facial recognition. The application of DL and visual pattern recognition techniques such as CNNs to EEG-derived color DSA image data could also be a possible area of future AI research. The integration of AI with EEG data during anesthesia holds significant potential for enhancing patient care by providing more accurate and responsive monitoring systems. Moreover, AI’s applications extend beyond patient care to include the education and training of anesthesiologists, offering novel ways to improve their skills and knowledge. This narrative review aims to provide an updated description of the applications of AI- and ML-based technologies applied to EEG in the field of anesthesiology.

APPLICATIONS OF AI FOR pEEG-BASED DEPTH OF ANESTHESIA MONITORING

Recent advances in AI have led to the development of increasingly sophisticated models for interpreting perioperative EEG signals, analyzing a vast amount of data, and detecting complex patterns that correspond to different levels of consciousness/awareness. Among these applications, one of the most active areas of research is the estimation of DoA, where ML algorithms are trained to extract clinically meaningful information from raw or processed EEG data.

The most recent and comprehensive synthesis of this topic is the systematic review by Lopes et al., published in Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing, which provides an in-depth evaluation of AI-based DoA prediction models, their input features, performance metrics, and validation strategies[21]. Within this body of literature, artificial neural networks (ANNs) represent the most employed modeling framework, though CNNs and other methods are also described.

Artificial neural networks

ANNs are computational models inspired by the structure of biological neural networks, composed of interconnected layers of artificial neurons. These systems process input through weighted connections and nonlinear activation functions, enabling them to capture complex, nonlinear relationships[22]. They consist of layers of interconnected units called neurons, which process and transmit information by applying mathematical transformations. Through training on large datasets, ANNs can learn complex patterns and relationships within the data.

This makes them particularly suitable for analyzing EEG signals, which are inherently complex, nonlinear, and often noisy. EEG data reflect dynamic brain activity and can vary significantly between individuals and conditions. Traditional methods often struggle to capture such variability, but ANNs can automatically learn relevant features directly from the data without the need for manual extraction[23]. By doing so, they can effectively classify brain states, detect abnormalities, and support real-time applications such as monitoring the DoA.

ANNs are suitable for EEG analysis when working with preprocessed, structured features - for example, mean power in specific frequency bands (alpha, beta, delta), entropy measures, or statistical values extracted from EEG segments. In this case, the input is a list of numbers representing specific characteristics of the EEG signal, and the ANN learns to associate these numbers with clinical outcomes such as DoA or seizure detection. However, ANNs do not consider the spatial or temporal organization of the EEG signal itself, which may limit their ability to capture complex patterns that vary over time or across channels[24].

Gu et al. combined multiple EEG-based features with ANN to assess the DoA in 16 patients, leading to a solid accuracy of detecting four states of anesthesia (86.4% for awake, 73.6% for light anesthesia, 84.4% for general anesthesia, and 14% for deep anesthesia) and a correlation coefficient between bispectral index (BIS) and the index of this method of 0.892 (P < 0.001)[25].

In one study, ANN models were trained using the expert assessment of consciousness level (EACL) as the reference standard. The EACL scores, determined by experienced anesthesiologists based on intraoperative observations, served as a clinically grounded alternative to conventional depth indices. The ANN model demonstrated a mean correlation of 0.73 ± 0.17 with the EACL ratings, compared to a lower correlation of 0.62 ± 0.19 for the BIS index on the same dataset[26]. The resulting ANN-based index demonstrated a strong temporal correlation with changes in consciousness and was more closely aligned with expert ratings than the BIS, suggesting improved clinical relevance. This study highlights the potential of combining entropy-based features with data-driven models to generate DoA metrics that better reflect anesthesiologist judgment in real-world settings.

Lee et al. (2018) evaluated a DL model for predicting the BIS during target-controlled infusion (TCI) of propofol and remifentanil[27,28]. Their model employed a deep ANN architecture combining long short-term memory (LSTM) and dense (feedforward) layers. The model uses an LSTM network, a type of ANN designed to handle time-based data such as drug infusion over time. This LSTM output is then combined with patient information - such as age, sex, weight, and height - and fed into another neural network that predicts the BIS value. This hybrid design aimed to predict real-time BIS values more accurately than conventional response surface models. Trained on data from 131 cases and tested on 100 independent cases, the model achieved a concordance correlation coefficient of 0.561 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.560-0.562], significantly outperforming the traditional model (0.265; 95%CI: 0.263-0.266; P < 0.001). The authors conclude that DL techniques can substantially improve the accuracy of BIS predictions during TCI, offering a promising approach for enhanced anesthetic pharmacodynamic monitoring[28].

Recently, an EEG-based deep neural multiple network [one for signal quality index (SQI), and the other analyzing EEG signals and estimating], or “neural multiple network”, called SQI-DOANet, was proposed with promising results [mean Pearson correlation coefficient with BIS of 0.82, with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 5.66][29].

These models are highly adaptable and benefit from normalization and segmentation procedures, which improve inter-subject consistency and temporal resolution. While ANNs offer considerable flexibility and performance in structured-data settings, their lack of interpretability and dependence on manually engineered input features may limit their application in raw EEG processing and in contexts where clinical transparency is essential.

Convolutional neural networks

CNNs, in contrast, are particularly effective when EEG signals are transformed into visual-like formats such as spectrograms or 2D images of frequency-time representations. CNNs can learn spatial and temporal patterns directly from these images, automatically identifying features such as rhythmic activity, burst suppression, and alpha oscillations without manual feature extraction. For example, they can distinguish between different anesthesia states based on spectral patterns in EEG images, making them especially valuable for real-time DoA monitoring. The ability of CNNs to detect local and hierarchical features enables them to interpret EEG in a more flexible and data-driven way than traditional ANNs.

Afhsar et al. developed a CNN that automatically classifies a patient’s level of anesthesia - awake, light, moderate, or deep - by analyzing spectrograms derived from EEG recordings. These spectrograms are created using a short-time Fourier transform (STFT), which transforms raw EEG data into visual representations of frequency changes over time[30]. The model was trained on data from 17 patients and achieved an accuracy of 88.7%, outperforming traditional ML methods. Overall, the study demonstrates that CNNs can offer a robust, automated solution for real-time anesthesia monitoring, reducing the need for manual signal interpretation[31].

Another application of CNNs was developed to address the risk of anesthetic overdose, a factor in nearly half of surgical complication-related deaths. In this study, EEG signals were transformed into spectral images using empirical mode decomposition (EMD) and its improved variant, ensemble EMD (EEMD), which reduces the problem of mode mixing - where frequency components overlap and hinder interpretability[32]. EEMD adds white noise and averages multiple decompositions to achieve better frequency separation. These enhanced spectral images were then used to train CNN classifiers to predict DoA based on BIS and SQI, without relying on handcrafted features. The best model achieved an accuracy of 83.2%, supporting the potential of DL to extract clinically relevant information from complex EEG signals[33].

Other approaches

A major challenge in EEG interpretation lies in the presence of interference, such as electromyographic (EMG) activity, eye movements, and other non-neural artifacts. While conventional DoA monitors include built-in filters to mitigate such interference, AI-driven approaches offer enhanced capabilities through advanced denoising techniques. An illustrative example is a recent study that proposed a single-channel EEG-based model for DoA monitoring using hierarchical dispersion entropy (HDE). A key component of this methodology was a hybrid denoising strategy that combined the wavelet transform with an improved non-local means (NLM) filter. This approach effectively removed EEG artifacts (e.g., EMG, ECG, and device-related noise) while preserving the integrity of the underlying neural signals. The model achieved a Pearson correlation of 0.96 with BIS values and performed reliably even under low signal quality conditions, accurately predicting DoA when BIS failed. Among various entropy-based features, HDE demonstrated the highest accuracy and robustness[34,35].

In another study, researchers tackled the problem of EEG signal contamination by applying an AI-based denoising strategy. Rather than relying on conventional rule-based filters, they implemented a sparse denoising autoencoder (SDAE), a DL model trained to reconstruct clean EEG signals from inputs corrupted by various types of noise, such as EMG artifacts or environmental interference. By learning the underlying structure of clean EEG data during training, the SDAE was able to selectively suppress noise while preserving physiologically relevant features. This data-driven denoising approach enhanced the quality of the EEG inputs used for anesthesia depth estimation.

The denoised features were subsequently fed into an LSTM network, which is well-suited for modeling time-dependent physiological signals due to its ability to retain long-range temporal dependencies. The combination of SDAE and LSTM (SDAE-LSTM) enabled the system to both clean and interpret EEG signals in a sequential context. The proposed model outperformed traditional entropy-based indices and single-feature approaches. Specifically, it achieved a prediction probability (Pk) of 0.8556, significantly higher than methods based on permutation entropy (Pk = 0.8373) and standalone LSTM networks (Pk = 0.8479)[36]. These results suggest that AI-based denoising via SDAE might substantially improve the reliability of EEG-based DoA monitoring.

A recent study proposed an automated system for assessing the depth of hypnosis during sevoflurane anesthesia, using a hierarchical classification approach based on support vector machines (SVMs), a type of ML algorithm. EEG signals were collected from 17 surgical patients and, based on the anesthesiologist’s clinical judgment, were labeled into four anesthetic states: awake, light anesthesia, general anesthesia, and deep anesthesia. To analyze these signals, the authors extracted several mathematical features that describe the complexity and variability of brain activity, including Shannon permutation entropy (SPE), detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA), sample entropy (SampEn), and EEG power in specific frequency bands (Beta index). Rather than applying a single classifier to all data, a step-by-step (hierarchical) structure was used: the system first identified the awake state, then distinguished deep anesthesia, and finally separated light from general anesthesia. Each step used the most relevant features to improve accuracy. The model achieved an overall classification accuracy of 94.11%, outperforming both traditional ML models and a commercial monitoring system (Response Entropy Index). This work illustrates how EEG signal characteristics, when combined with tailored AI models and expert clinical labeling, can provide a reliable tool for real-time DoA monitoring[37].

Another application of AI in DoA monitoring is exemplified by the quantium nociception index (qNOX) algorithm, introduced by Gambus et al.[38]. The qNOX index was developed using an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), a hybrid model that combines fuzzy logic with neural network learning. While traditional ANNs and CNNs are highly effective at capturing complex, nonlinear relationships in EEG data, they are often referred to as “black-box” models due to their limited interpretability. In contrast, ANFIS incorporates rule-based reasoning through fuzzy logic, allowing for transparent IF-THEN rules that can be guided by expert-defined clinical scales such as the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (OAA/S) or the Ramsay scale[39]. In the case of qNOX, these scales were used to label training data and define reference states of responsiveness. EEG-derived features such as spectral ratios were mapped to these clinical states using membership functions, which express partial degrees of truth (e.g., intermediate sedation levels). During training, the neural component of ANFIS adjusts the parameters of both the rules and the output weights to align with the observed data[40]. While ANFIS offers potential benefits in terms of interpretability and computational efficiency - particularly in structured or clinically annotated datasets - ANN and CNN models may be more suitable when dealing with high-dimensional raw EEG inputs. The selection of the most appropriate approach ultimately depends on the specific clinical setting, data characteristics, and the balance between performance and explainability.

The future may lie in introducing AI-driven medical devices into operating rooms, designed to assess DoA by integrating a broader spectrum of clinical data, such as auditory evoked potentials and HR variability[41,42].

At present, however, no medical devices approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are available for estimating the DoA in the operating room[43]. A summary of current AI applications in DoA monitoring is presented in Table 1.

Current applications of artificial intelligence in DoA monitoring

| Approach | Model types | Input data | Strengths | Limitations |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)[25-29] | Supervised learning | Structured features (e.g., band power, entropy) | Handles nonlinear data, suitable for structured inputs | Requires manual feature extraction; limited temporal modeling |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)[30-33] | Deep learning | Raw EEG Spectrograms, time–frequency images | Learns spatial & temporal patterns; automatic feature extraction | Black-box nature; requires large datasets; computationally intensive |

| Hybrid models (e.g., SDAE + LSTM)[36] | Deep learning | Raw or denoised EEG | Combines denoising and sequential modeling; good for noisy signals | Increased model complexity; less interpretability |

| ANFIS (Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems)[38-40] | Hybrid AI (fuzzy + neural) | Preprocessed spectral features + clinical labels | Interpretable rule-based logic; integrates expert clinical knowledge | Less flexible than deep learning; depends on expert-defined rules |

| Hierarchical Support Vector Machines (SVMs)[37] | Supervised learning | Engineered EEG features (e.g., entropy, DFA, power) | Tailored classification for overlapping states; interpretable decision logic | Relies on manual feature engineering; limited adaptability to raw signals |

Recent developments in AI-based DoA monitors have the potential to enable clinically relevant applications beyond experimental settings. DL models have been used to improve BIS prediction during propofol-remifentanil TCI, potentially enhancing intraoperative drug titration and surpassing current population-based prediction models[28]. In parallel, systems such as SQI-DOANet incorporate signal quality estimation, enabling robust DoA monitoring even under poor EEG conditions. CNN-based models trained on spectral representations have shown high classification accuracy without relying on handcrafted features or specific drugs, making them adaptable across anesthetic regimens. Lightweight classifiers using hierarchical SVMs with entropy and frequency-domain features also offer promise for portable DoA monitoring in resource-limited settings. Lastly, hybrid models such as ANFIS - as used in the development of the qNOX index - integrate fuzzy logic with clinical sedation scales (e.g., OAA/S or Ramsay), offering improved alignment with expert judgment. However, the limited availability of prospective data and the lack of validation in randomized study settings warrant caution regarding the potential applications of these methods, which will require broader integration into clinical research before they can be considered for established clinical use.

VIRTUAL AND AUGMENTED REALITY IN SIMULATION-BASED TRAINING FOR ANESTHESIA: pEEG APPLICATIONS

Simulation-based training (SBT) is an educational methodology that employs virtual environments and the creation of realistic scenarios to train professionals across a variety of fields, including medicine, aviation, engineering, and emergency management[44].

Through simulation, it is possible to gain practical experience in complex scenarios and confront operational challenges in a controlled and safe environment, with the aim of developing technical, decision-making, and teamwork skills[45,46].

The integration of AI into SBT, through its ability to analyze and adapt scenarios in real time, optimizes the potential of this methodology. AI not only replicates realistic situations but also uses advanced algorithms to predict user reactions and affective states during the learning trajectory, identify weaknesses, dynamically modify the simulated environment, and manage assessments and feedback[47,48]. ML, a branch of AI, through both supervised and unsupervised algorithms, uses vital sign data monitored during anesthesia to create simulation scenarios where participants’ actions physiologically or pathologically affect clinical outcomes[49].

When integrated with virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and customizable three-dimensional (3D) virtual patient models, this approach offers immersive and dynamic environments designed to enhance the precision, engagement, and efficacy of educational and training experiences[50]. Both VR and AR feature interactivity, the use of 3D images, and immersion in a virtual environment. However, in VR, the simulated environment is entirely computer-generated by AI with no interaction with the real world; in contrast, AR enriches the real environment with digital elements. In the medical field, these technologies are widely applied in surgical training, with specific training sessions aimed at enhancing operators’ experience without the need for real-life surgeries[51].

Such applications can be found in general surgery, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and ophthalmology[52-54]. VR and AR are extensively utilized in regional anesthesia, where they improve ultrasound-based anatomical recognition and needle guidance to the desired site while reducing the learning curve[55,56]. They allow the acquisition of technical skills such as performing bronchoscopy and the placement of vascular access and non-technical skills such as decision making and communication[57-59].

The use of SBT to optimize the interpretation of EEG has been proposed in the teaching of clinical neurophysiology and could be applied for the acquisition of skills related to pharmacological management of anesthesia depth based on EEG data, although there is currently limited evidence supporting its use[60,61]. It is recognized that the intraoperative interpretation of EEG waveforms corresponding to various hypnotic depths, along with the identification of discrepancies with the processed pEEG index (pEEG), can be improved through structured training[62,63]. To this end, the use of interactive, screen-based online simulators that provide self-directed instruction and assess participants’ EEG knowledge in the context of a self-paced EEG interpretation training program has been shown to be effective in optimizing interpretation skills and competence of trainees in intensive care medicine with an educational background in anesthesiology[64]. Another study, conducted on 13 participants, demonstrated a statistically significant improvement (P = 0.012) in the interpretation of the 25-item EEG score compared to baseline following the educational experience with the web-based simulator (mean change = 3.9, 95%CI: 1.1 to 6.7). The authors also reported that participants perceived an improvement in their confidence and decision-making abilities for therapeutic purposes, attributed to the knowledge acquired through this type of training[65].

Despite these advantages, the use of VR and AR specifically for training in intraoperative EEG interpretation, which has become a crucial tool in managing anesthesia depth and personalization, remains underexplored. Nevertheless, the potential benefits could be considerable. VR, by creating an immersive environment such as a virtual operating room, would offer a setting in which anesthesiologists could simulate the use of EEG in realistic clinical contexts, without interacting with real patients, while monitoring real-time brain signal variations and adapting anesthesia management accordingly[66].

AR, on the other hand, by overlaying digital information onto the real environment during surgery using devices such as AR glasses or headsets, would allow anesthesiologists to receive immediate feedback on EEG tracings, including the identification of abnormal waves or anesthesia depth levels, as already implemented during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) era to enhance intubation skills and hemodynamic management[67].

This would enhance the ability to interpret EEG signals in real time, thus improving both theoretical understanding and practical management skills in critical situations.

Nevertheless, the implementation of SBT through AI entails certain inherent limitations.

First of all, it is associated with variable, often high, costs related to software, hardware, or platforms dedicated to the healthcare field (tablets, computers, projection-based displays, headsets, dedicated programs), making them not always easily accessible or installable[68]. In addition, the costs of the human resources required for their management and maintenance, as well as for training healthcare personnel to use these technologies, must also be considered[69]. A second relevant aspect is represented by the psychological and physical impact that AR and VR may have on the health of those who use them: a tendency toward depersonalization and derealization, motion sickness, headache, cybersickness, visual problems, and nausea have been observed in association with prolonged use of such systems[70,71].

Furthermore, the quality of images and the fidelity of scenarios and user interactions represent an additional challenge in the context of technological advancement. Indeed, within SBT, these aspects appear to influence the educational experience, which tends to be more effective when the environment and the tools used are perceived as highly reliable and realistic[72,73].

Finally, the ethical and legal implications of AI use, including privacy protection, data security breaches, and misuse in the event of potential information leakage, must be mentioned. This requires particular attention to privacy management in accordance with existing regulations, and the definition of specific strategies aimed at reducing and preventing these events. Other critical issues include the reliability, transparency, and potential bias of AI systems, as well as their interaction with human users - factors that are key to ensuring user acceptance and trust in their application[74].

Table 2 provides an overview of the essential components required to design a VR/AR scenario for SBT, specifically aimed at improving anesthetic management through interpretation and decision making guided by pEEG monitoring.

Conceptual illustration of a hypothetical VR/AR-based SBT framework for pEEG-guided anesthetic management

| Component | Description |

| Virtual reality (VR) | Fully simulated operating room; EEG waveform displays; adjustable depth of anesthesia in real time |

| Augmented reality (AR) | EEG overlays on real patients or manikins; guidance tools for real-time waveform interpretation |

| AI/ML algorithms | Simulate patient-specific EEG responses to anesthetics; predict physiological consequences of trainee actions |

| 3D virtual patients | Customizable avatars that generate dynamic EEG signals in response to anesthetic administration |

| pEEG simulators | Virtual BIS monitors with variable correlation to raw EEG for interpretive challenge |

LIMITATIONS ON AI APPLICATIONS IN THE PERIOPERATIVE SETTING

The primary limitation in implementing AI-based systems using EEG to assess the DoA arises from intrinsic challenges in translating the complex brain states induced by anesthesia into a single numerical value. Several authors have recently demonstrated that a significant percentage of cases exhibit substantial discrepancies between monitors from different manufacturers, even when the anesthesia state is identical[75]. Consequently, various editorials have suggested moving away from relying on single indices to evaluate cerebral progression during anesthesia[76,77]. In this context, there is a need for standardization in recognizing EEG patterns during general anesthesia, although a globally recognized consensus on the topic is currently lacking. Any device employing AI to assess the depth of general anesthesia based on EEG recognition of different patterns would therefore face a substantial risk of bias. As discussed in the section on current AI applications for DoA monitors, existing models show promising accuracy within specific patient populations and anesthetic techniques. However, most have been developed using limited datasets and lack external validation across diverse patient groups and anesthetic regimens. To improve clinical relevance, future research should focus on building more robust and generalizable models by including heterogeneous patient data and a wider range of anesthetic agents.

A second limitation is the lack of interoperability among monitoring devices, which persists in healthcare in 2024. Integrating data from various sources is vital for developing newer ML and AI algorithms. It remains a major challenge in the successful implementation of ML for both diagnostics and precision medicine. One of the main obstacles is the inconsistency and lack of a standardized data structure within electronic health records (EHRs). Different healthcare providers and databases store patient data in diverse formats and types, making it difficult for systems to seamlessly interpret and integrate these records. This can result in fragmented patient histories where varying information on diagnoses and treatment plans complicates comprehensive analysis. On the other hand, it is not possible to grant unrestricted access to databases containing sensitive information. Ensuring the privacy and security of patient information is paramount. EHR systems must comply with regulations such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union, which mandate strict protection of personal health information (PHI)[78]. A single data breach can lead to significant financial penalties and reputational harm for healthcare organizations.

Integrating new EHR products with existing infrastructure poses further challenges as not all systems are designed to work together, leading to potential vulnerabilities. Moreover, the lack of unified communication standards across EHRs exacerbates these issues. Providers often use different standards that may or may not align with those of neighboring or associated organizations, creating further obstacles to achieving a coherent, interoperable healthcare system. Recently, this discussion has led to the implementation of the proposed Bill C-72, currently under debate in Canada, which aims to establish secure digital access to health data for patients and providers, while enforcing common interoperability standards to ensure seamless data exchange across healthcare platforms. An essential aspect of Bill C-72 is its emphasis on data interoperability. Health information technology manufacturers are mandated to ensure that their systems achieve full interoperability, facilitating the secure and seamless access, utilization, and exchange of electronic health information across diverse platforms[79].

One significant challenge in modern healthcare research, particularly in the era of AI, is the restricted access to medical device communication protocols. Manufacturers frequently limit or outright block access to these protocols, creating substantial barriers to effective data utilization.

This lack of standardization results in data silos, as most medical devices in operating rooms, ICUs, and hospital wards fail to output data in open, standards-compliant formats. Contrary to common assumptions, the use of communication standards such as the Health Level 7 (HL7) protocol is far from widespread in the medical device industry. Instead, proprietary, binary-format data may be used, which requires transformation through manufacturer-specific gateways[80].

Even when manufacturers of medical monitors claim compatibility with HL7 version 2.x, the naming conventions used for export of physiological variables remain vendor-specific. For example, non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) might be labeled differently - such as NIBP, Non-invasive BP, or NBP - depending on the manufacturer. The adoption of standardized naming conventions or coding systems is uncommon. Examples include ISO 11073:10101 (international standards for medical device nomenclature and communication), SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine - Clinical Terms, a comprehensive multilingual clinical healthcare terminology), and LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes, a universal standard for identifying laboratory tests and clinical measurements). This highlights the urgent need for implementing standardized, interoperable data export protocols across the healthcare ecosystem. The implementation of legislation such as the proposed European Commission Data Act, the European Health Data Space, and commitments to open interfacing is needed globally[81-83].

As a third limitation, the algorithms used by commercial devices involved in processing EEG signals are often proprietary and difficult to analyze[84]. Researchers have attempted to reproduce these automated algorithms with varying degrees of success[85]. Although commercial EEG monitors may show live data, real-time numeric and EEG waveform data export needed for AI applications and clinical decision support systems may not be available. Some monitors, such as the BIS monitor (Medtronic), SedLine (Masimo), and Entropy (GE Healthcare), as well as monitors from manufacturers such as Conox and Narcotrend, may offer data archiving via the RS232 serial port, Bluetooth, or the USB port of pEEG devices. The capture of high-fidelity raw EEG data could enable researchers to compare the performance of these monitors by ‘replaying’ EEG data[86]. Software applications such as VSCapture and VitalRecorder have been developed that allow real-time binary data acquisition of raw EEG waveforms via the RS232 port on some of these devices[87-89]. The capture of multimodal data including vital signs, infusion data, and raw EEG data could provide multiple feature extraction and vector embeddings for AI applications. The VSCapture project offers open-source code to capture data from multiple commercial devices. The captured data include numeric power spectral data and raw EEG waveforms, exported as comma-separated value (CSV) files[90-92]. These CSV files can also be converted into the European data format (EDF) and imported into other EEG analytical software, such as EDFBrowser, for power spectral analysis and color DSA generation[93]. EEG features extracted from numeric data have been used to develop AI algorithms[25]. Access to high-fidelity raw EEG data is desirable, which could enable the creation of large multicenter datasets of EEG under anesthesia. This may aid the development of novel DL algorithms, indices, and decision support tools[94-98].

Recent challenges stemming from concerns about potential bias in a ML-based index for predicting hypotensive events in the operating room have intensified the discussion surrounding the need for greater methodological rigor in AI research within healthcare[99-101].

Some authors have suggested implementing algorithmic stewardship for AI and ML-based technologies in healthcare, advocating for a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach to safeguard against biases and ensure equitable patient care[102]. It should not be overlooked that AI techniques must be evaluated with the same rigor as traditional scientific and statistical methods and, where applicable, should undergo stringent validation processes. Systematic reviews reveal that only a limited number of ML diagnostic studies have been evaluated using external cohorts or directly compared with healthcare professionals. Many of these studies suffer from inadequate internal validation, insufficient descriptions of their AI model architectures, hyperparameter tuning processes, and data preprocessing steps, substandard reporting practices, and testing under conditions that do not accurately represent real-world scenarios. This opacity makes it challenging for other researchers to reproduce the reported results or build upon the existing work. For example, the specific features extracted from EEG, the rationale for their selection, and the exact configuration of neural networks are often not fully disclosed, impeding scientific progress and independent verification. For example, assessing ML diagnostic algorithms against human judgment without accounting for patient context does not accurately capture real-world clinical workflows[103].

Another major limitation is the scarcity of longitudinal studies linking pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) data with reliable EEG-derived measures of sedation over prolonged periods. Most available investigations focus on short intraoperative epochs or isolated ICU snapshots, without assessing the stability of EEG-drug concentration relationships during long-term sedation[104]. This gap hinders our ability to understand tolerance development, time-dependent pharmacodynamic changes, and the need for model recalibration over extended infusions.

Similarly, real-time performance metrics - such as computational latency and responsiveness - are seldom reported, despite being essential for continuous bedside application. Future research should address these gaps through prospective, longitudinal studies that combine continuous EEG monitoring, PK/PD modeling, and clinical outcomes to validate the robustness and temporal stability of AI systems for guiding anesthesia and sedation.

Finally, our review highlights a key limitation in current research - the reliance on small, single-center, and homogeneous datasets, which limits the generalizability of AI models for DoA assessment. Because anesthetic agents, patient demographics, and surgical procedures strongly influence EEG patterns, models trained on narrow datasets may underperform in diverse clinical contexts.

Closely related to this issue is the inadequate internal validation and the lack of rigorous external validation. Many studies demonstrate high performance on their training or internal validation datasets but fail to replicate these results when tested on unseen data from different institutions or patient populations. This discrepancy often arises from overfitting to dataset-specific characteristics or biases. To ensure clinical utility and reliability, AI models must undergo robust external validation, ideally on prospectively collected, independent datasets that accurately reflect the diversity and complexity of real-world practice. Without such validation, reported performance metrics may be overly optimistic and hinder both reproducibility and clinical adoption.

Future research should therefore focus on multicenter studies, heterogeneous patient populations, and systematic external validation protocols to develop more robust and broadly applicable AI solutions for intraoperative pEEG applications[105].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, AI and ML have greatly advanced DoA monitoring by improving accuracy and addressing limitations in traditional methods. These tools hold the promise of enhancing patient safety and outcomes by allowing anesthesiologists to better maintain the appropriate DoA throughout surgical procedures. There is growing interest in the use of such technologies to potentially support the enhancement of DoA monitoring systems and to serve as novel platforms for training anesthesiologists, particularly in improving their ability to interpret complex neurophysiological signals. Despite the undeniable advantages and high expectations in the scientific community surrounding the use of these tools for intraoperative pEEG applications in measuring anesthesia depth, their practical applications remain quite limited to date. A significant methodological and technological effort will be required to overcome some of the limitations that risk hindering the development of these techniques in clinical practice.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Contributed to the design of the review and to the writing of the main chapters: Introna M, Karippacheril JG, Carozzi C, Trimarchi D, Pilla S, Gemma M, Martino D

All authors have read and revised the manuscript and approved it in its entirety.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work received no external funding.

Conflicts of interest

The research group of Introna M has received (over the last 3 years) research grants from Becton Dickinson (Eysins, Switzerland) and consultancy fees from Aspen Healthcare FZ LLC (Dubai, UAE). Karippacheril JG is the chief author and designer of the software project VSCapture, which enables automated data capture from medical devices in the operating rooms and the ICU.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Kim MC, Fricchione GL, Brown EN, Akeju O. Role of electroencephalogram oscillations and the spectrogram in monitoring anaesthesia. BJA Educ. 2020;20:166-72.

2. Lobo FA, Saraiva AP, Nardiello I, Brandão J, Osborn IP. Electroencephalogram monitoring in anesthesia practice. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2021;11:169-80.

4. Purdon PL, Sampson A, Pavone KJ, Brown EN. Clinical electroencephalography for anesthesiologists: part I: background and basic signatures. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:937-60.

5. Obert DP, Hight D, Sleigh J, et al. The first derivative of the electroencephalogram facilitates tracking of electroencephalographic alpha band activity during general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2022;134:1062-71.

6. Fahy BG, Chau DF. The technology of processed electroencephalogram monitoring devices for assessment of depth of anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:111-7.

7. Mashour GA, Alkire MT. Consciousness, anesthesia, and the thalamocortical system. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:13-5.

8. Pollak M, Leroy S, Röhr V, Brown EN, Spies C, Koch S. Electroencephalogram biomarkers from anesthesia induction to identify vulnerable patients at risk for postoperative delirium. Anesthesiology. 2024;140:979-89.

9. Bruzzone MJ, Chapin B, Walker J, et al. Electroencephalographic measures of delirium in the perioperative setting: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2025;140:1127-39.

10. Koch S, Feinkohl I, Chakravarty S, et al.; BioCog Study Group. Cognitive impairment is associated with absolute intraoperative frontal α-band power but not with baseline α-band power: a pilot study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2019;48:83-92.

11. Alfonso JCF, Salvador TRJ, Antonio AFM, Saul TA. Comparison of bioelectric signals and their applications in artificial intelligence: a review. Computers. 2025;14:145.

12. Yoon D, Jang JH, Choi BJ, Kim TY, Han CH. Discovering hidden information in biosignals from patients using artificial intelligence. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2020;73:275-84.

13. Lee YJ, Park C, Kim H, Cho SJ, Yeo W. Artificial intelligence on biomedical signals: technologies, applications, and future directions. Med-X. 2024;2:43.

14. Bergmann D, Stryker C. What is vector embedding? Available from: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/vector-embedding#:~:text=Vector%20embeddings%20are%20numerical%20representations,(ML)%20models%20can%20process [accessed 11 December 2025].

16. Gomez-Quintana S, O’Shea A, Factor A, Popovici E, Temko A. A method for AI assisted human interpretation of neonatal EEG. Sci Rep. 2022;12:10932.

17. Cao Z. A review of artificial intelligence for EEG‐based brain-computer interfaces and applications. Brain Sci Adv. 2020;6:162-70.

18. Craik A, He Y, Contreras-Vidal JL. Deep learning for electroencephalogram (EEG) classification tasks: a review. J Neural Eng. 2019;16:031001.

19. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. 2017;60:84-90.

20. Castellano G, Vessio G. Deep learning approaches to pattern extraction and recognition in paintings and drawings: an overview. Neural Comput Appl. 2021;33:12263-82.

21. Lopes S, Rocha G, Guimarães-Pereira L. Artificial intelligence and its clinical application in anesthesiology: a systematic review. J Clin Monit Comput. 2024;38:247-59.

22. Ram M, Afrash MR, Moulaei K, et al. Application of artificial intelligence in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) disease prediction and management: a scoping review. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:1026.

23. Praveena D, Angelin Sarah D, Thomas George S. Deep learning techniques for EEG signal applications - a review. IETE J Res. 2022;68:3030-7.

24. Boonyakitanont P, Lek-uthai A, Chomtho K, Songsiri J. A comparison of deep neural networks for seizure detection in EEG signals. BioRxiv. ;2019:702654.

25. Gu Y, Liang Z, Hagihira S. Use of multiple EEG features and artificial neural network to monitor the depth of anesthesia. Sensors. 2019;19:2499.

26. Jiang GJA, Fan SZ, Abbod MF, et al. Sample entropy analysis of EEG signals via artificial neural networks to model patients’ consciousness level based on anesthesiologists experience. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:343478.

27. Lee HC, Ryu HG, Chung EJ, Jung CW. Prediction of bispectral index during target-controlled infusion of propofol and remifentanil: a deep learning approach. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:492-501.

29. Yu R, Zhou Z, Xu M, et al. SQI-DOANet: electroencephalogram-based deep neural network for estimating signal quality index and depth of anaesthesia. J Neural Eng. 2024;21:046031.

30. Afshar S, Boostani R, Sanei S. A combinatorial deep learning structure for precise depth of anesthesia estimation from EEG signals. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2021;25:3408-15.

31. Haghighi SJ, Komeili M, Hatzinakos D, Beheiry HE. 40-Hz ASSR for measuring depth of anaesthesia during induction phase. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2018;22:1871-82.

32. Yu H, Baek S, Lee J, Sohn I, Hwang B, Park C. Deep neural network-based empirical mode decomposition for motor imagery EEG classification. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2024;32:3647-56.

33. Madanu R, Rahman F, Abbod MF, Fan SZ, Shieh JS. Depth of anesthesia prediction via EEG signals using convolutional neural network and ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Math Biosci Eng. 2021;18:5047-68.

34. Alsafy I, Diykh M. Developing a robust model to predict depth of anesthesia from single channel EEG signal. Phys Eng Sci Med. 2022;45:793-808.

35. Diykh M, Li Y, Wen P, Li T. Complex networks approach for depth of anesthesia assessment. Measurement. 2018;119:178-89.

36. Li R, Wu Q, Liu J, Wu Q, Li C, Zhao Q. Monitoring depth of anesthesia based on hybrid features and recurrent neural network. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:26.

37. Shalbaf A, Shalbaf R, Saffar M, Sleigh J. Monitoring the level of hypnosis using a hierarchical SVM system. J Clin Monit Comput. 2020;34:331-8.

38. Gambús PL, Jensen EW, Jospin M, et al. Modeling the effect of propofol and remifentanil combinations for sedation-analgesia in endoscopic procedures using an Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS). Anesth Analg. 2011;112:331-9.

39. Jensen EW, Valencia JF, López A, et al. Monitoring hypnotic effect and nociception with two EEG-derived indices, qCON and qNOX, during general anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58:933-41.

40. Vellinga R, Introna M, van Amsterdam K, et al. Implementation of a Bayesian based advisory tool for target-controlled infusion of propofol using qCON as control variable. J Clin Monit Comput. 2024;38:519-29.

41. Tacke M, Kochs EF, Mueller M, Kramer S, Jordan D, Schneider G. Machine learning for a combined electroencephalographic anesthesia index to detect awareness under anesthesia. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0238249.

42. Zhan J, Wu ZX, Duan ZX, et al. Heart rate variability-derived features based on deep neural network for distinguishing different anaesthesia states. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21:66.

43. U. S. Food & Drug Administration. Artificial intelligence and machine learning (ai/ml)-enabled medical devices. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-aiml-enabled-medical-devices [accessed 11 December 2025].

44. Fan W, Chen P, Shi D, Guo X, Kou L. Multi-agent modeling and simulation in the AI age. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2021;26:608-24.

45. Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Okatta AU, et al. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: a review. Medicine. 2024;103:e38813.

47. Dai CP, Ke F. Educational applications of artificial intelligence in simulation-based learning: a systematic mapping review. Comput Educ Artif Intell. 2022;3:100087.

48. Wang Z, Jiang J, Zhan Y, et al. Hypnos: a domain-specific large language model for anesthesiology. Neurocomputing. 2025;624:129389.

49. Kundra P, Senthilnathan M. Amalgamation of artificial intelligence and simulation in anaesthesia training: much-needed future endeavour. Indian J Anaesth. 2024;68:8-10.

50. Javvaji CK, Reddy H, Vagha JD, Taksande A, Kommareddy A, Reddy NS. Immersive innovations: exploring the diverse applications of virtual reality (VR) in healthcare. Cureus. 2024;16:e56137.

51. Lungu AJ, Swinkels W, Claesen L, Tu P, Egger J, Chen X. A review on the applications of virtual reality, augmented reality and mixed reality in surgical simulation: an extension to different kinds of surgery. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2021;18:47-62.

52. McKnight RR, Pean CA, Buck JS, Hwang JS, Hsu JR, Pierrie SN. Virtual reality and augmented reality-translating surgical training into surgical technique. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020;13:663-74.

53. Paro MR, Hersh DS, Bulsara KR. History of virtual reality and augmented reality in neurosurgical training. World Neurosurg. 2022;167:37-43.

54. Heinrich F, Huettl F, Schmidt G, et al. HoloPointer: a virtual augmented reality pointer for laparoscopic surgery training. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2021;16:161-8.

55. Moo-Young J, Weber TM, Kapralos B, Quevedo A, Alam F. Development of unity simulator for epidural insertion training for replacing current lumbar puncture simulators. Cureus. 2021;13:e13409.

56. Savage M, Spence A, Turbitt L. The educational impact of technology-enhanced learning in regional anaesthesia: a scoping review. Br J Anaesth. 2024;133:400-15.

57. Bejani M, Taghizadieh A, Samad-Soltani T, Asadzadeh A, Rezaei-Hachesu P. The effects of virtual reality-based bronchoscopy simulator on learning outcomes of medical trainees: a systematic review. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:e1398.

58. Bracq MS, Michinov E, Jannin P. Virtual reality simulation in nontechnical skills training for healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Simul Healthc. 2019;14:188-94.

59. Evans LV, Dodge KL, Shah TD, et al. Simulation training in central venous catheter insertion: improved performance in clinical practice. Acad Med. 2010;85:1462-9.

60. Björn M. Development of an effective pedagogical EEG simulator: design-based research project among biomedical laboratory science students. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland, 2022. Available from: https://erepo.uef.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/575e4b96-e61e-48f4-a44f-7585be1cd91a/content [accessed 11 December 2025].

61. Yun WJ, Shin M, Jung S, Ko J, Lee HC, Kim J. Deep reinforcement learning-based propofol infusion control for anesthesia: a feasibility study with a 3000-subject dataset. Comput Biol Med. 2023;156:106739.

62. Bombardieri AM, Wildes TS, Stevens T, et al. Practical training of anesthesia clinicians in electroencephalogram-based determination of hypnotic depth of general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:777-86.

63. Barnard JP, Bennett C, Voss LJ, Sleigh JW. Can anaesthetists be taught to interpret the effects of general anaesthesia on the electroencephalogram? Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:532-7.

64. Fahy BG, Cibula JE, Johnson WT, et al. An online, interactive, screen-based simulator for learning basic EEG interpretation. Neurol Sci. 2021;42:1017-22.

65. Fahy BG, Lampotang S, Cibula JE, et al. Impact of simulation on critical care fellows’ electroencephalography learning. Cureus. 2022;14:e24439.

66. Singh PM, Kaur M, Trikha A. Virtual reality in anesthesia “simulation”. Anesth Essays Res. 2012;6:134-9.

68. Venkatesan M, Mohan H, Ryan JR, et al. Virtual and augmented reality for biomedical applications. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2:100348.

69. Farrell K, MacDougall D. An overview of clinical applications of virtual and augmented reality. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2023. Report No.: EH0011. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK596298/ [accessed 11 December 2025].

70. Stanney KM, Kennedy RS, Drexler JM. Cybersickness is not simulator sickness. Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meet. 1997;41:1138-42.

71. Spiegel JS. The ethics of virtual reality technology: social hazards and public policy recommendations. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018;24:1537-50.

72. Lowell VL, Tagare D. Authentic learning and fidelity in virtual reality learning experiences for self-efficacy and transfer. Comput Educ X Real. 2023;2:100017.

73. Arthur T, Loveland-perkins T, Williams C, et al. Examining the validity and fidelity of a virtual reality simulator for basic life support training. BMC Digit Health. 2023;1:16.

74. Corrêa NK, Galvão C, Santos JW, et al. Worldwide AI ethics: a review of 200 guidelines and recommendations for AI governance. Patterns. 2023;4:100857.

75. Hight D, Kreuzer M, Ugen G, et al. Five commercial ‘depth of anaesthesia’ monitors provide discordant clinical recommendations in response to identical emergence-like EEG signals. Br J Anaesth. 2023;130:536-45.

76. McCulloch TJ, Sanders RD. Depth of anaesthesia monitoring: time to reject the index? Br J Anaesth. 2023;131:196-9.

77. Introna M, Gemma M, Carozzi C. Improving the benefit of processed EEG monitors: it’s not about the car but the driver. J Clin Monit Comput. 2023;37:723-5.

78. U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/php/resources/health-insurance-portability-and-accountability-act-of-1996-hipaa.html [accessed 11 December 2025].

79. House of Commons of Canada. Bill-C72. Available from: https://www.parl.ca/documentviewer/en/44-1/bill/C-72/first-reading [accessed 11 December 2025].

80. Torab-Miandoab A, Samad-Soltani T, Jodati A, Rezaei-Hachesu P. Interoperability of heterogeneous health information systems: a systematic literature review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23:18.

81. Jendle J, Adolfsson P, Choudhary P, et al. A narrative commentary about interoperability in medical devices and data used in diabetes therapy from an academic EU/UK/US perspective. Diabetologia. 2024;67:236-45.

82. European Commission. European Health Data Space Regulation (EHDS). Available from: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space_en#more-information [accessed 11 December 2025].

83. European Commission. Data Act: Proposal for a Regulation on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data. Available from: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/data-act-proposal-regulation-harmonised-rules-fair-access-and-use-data [accessed 11 December 2025].

85. Connor CW. OpenBSR: an open algorithm for burst suppression rate concordant with the BIS monitor. Anesth Analg. 2025;140:220-3.

86. Lipp M, Schneider G, Kreuzer M, Pilge S. Substance-dependent EEG during recovery from anesthesia and optimization of monitoring. J Clin Monit Comput. 2024;38:603-12.

87. Karippacheril JG, Ho TY. Data acquisition from S/5 GE Datex anesthesia monitor using VSCapture. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:423-4.

88. Vistisen ST, Pollard TJ, Enevoldsen J, Scheeren TWL. VitalDB: fostering collaboration in anaesthesia research. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:184-7.

89. Lee HC, Park Y, Yoon SB, Yang SM, Park D, Jung CW. VitalDB, a high-fidelity multi-parameter vital signs database in surgical patients. Sci Data. 2022;9:279.

90. GitHub. Karippacheril JG. VSCaptureBISV. Available from: https://github.com/xeonfusion/VSCaptureBISV [accessed 11 December 2025].

91. SourceForge. Karippacheril JG. VitalSignsCapture. Available from: https://sourceforge.net/projects/vscapture/ [accessed 11 December 2025].

92. Lichtenfeld F, Kratzer S, Hinzmann D, García PS, Schneider G, Kreuzer M. The influence of electromyographic on electroencephalogram-based monitoring: putting the forearm on the forehead. Anesth Analg. 2024;138:1285-94.

93. Van Beleen T. EDFbrowser. Available from: https://www.teuniz.net/edfbrowser/ [accessed 11 December 2025].

94. Schmierer T, Li T, Li Y. Harnessing machine learning for EEG signal analysis: Innovations in depth of anaesthesia assessment. Artif Intell Med. 2024;151:102869.

95. Zeng S, Qing Q, Xu W, et al. Personalized anesthesia and precision medicine: a comprehensive review of genetic factors, artificial intelligence, and patient-specific factors. Front Med. 2024;11:1365524.

96. Pose F, Videla C, Campanini G, Ciarrocchi N, Redelico FO. Using EEG total energy as a noninvasively tracking of intracranial (and cerebral perfussion) pressure in an animal model: a pilot study. Heliyon. 2024;10:e28544.

97. Li W, Varatharajah Y, Dicks E, et al. Data-driven retrieval of population-level EEG features and their role in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Commun. 2024;6:fcae227.

98. Laferrière-Langlois P, Morisson L, Jeffries S, Duclos C, Espitalier F, Richebé P. Depth of anesthesia and nociception monitoring: current state and vision for 2050. Anesth Analg. 2024;138:295-307.

99. Eaneff S, Obermeyer Z, Butte AJ. The case for algorithmic stewardship for artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies. JAMA. 2020;324:1397-8.

100. Enevoldsen J, Vistisen ST. Performance of the hypotension prediction index may be overestimated due to selection bias. Anesthesiology. 2022;137:283-9.

101. Davies SJ, Vistisen ST, Jian Z, Hatib F, Scheeren TWL. Ability of an arterial waveform analysis-derived hypotension prediction index to predict future hypotensive events in surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:352-9.

102. Montomoli J, Bitondo MM, Cascella M, et al. Algor-ethics: charting the ethical path for AI in critical care. J Clin Monit Comput. 2024;38:931-9.

103. Wilkinson J, Arnold KF, Murray EJ, et al. Time to reality check the promises of machine learning-powered precision medicine. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:e677-80.

104. Introna M, Carozzi C, Gentile A, et al. Target controlled infusion in the intensive care unit: a scoping review. J Clin Monit Comput. 2025.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].