Current innovations in blood flow assessment: the role of 4D-flow MRI and computational fluid dynamics in hepatobiliopancreatic surgery: a systematic review

Abstract

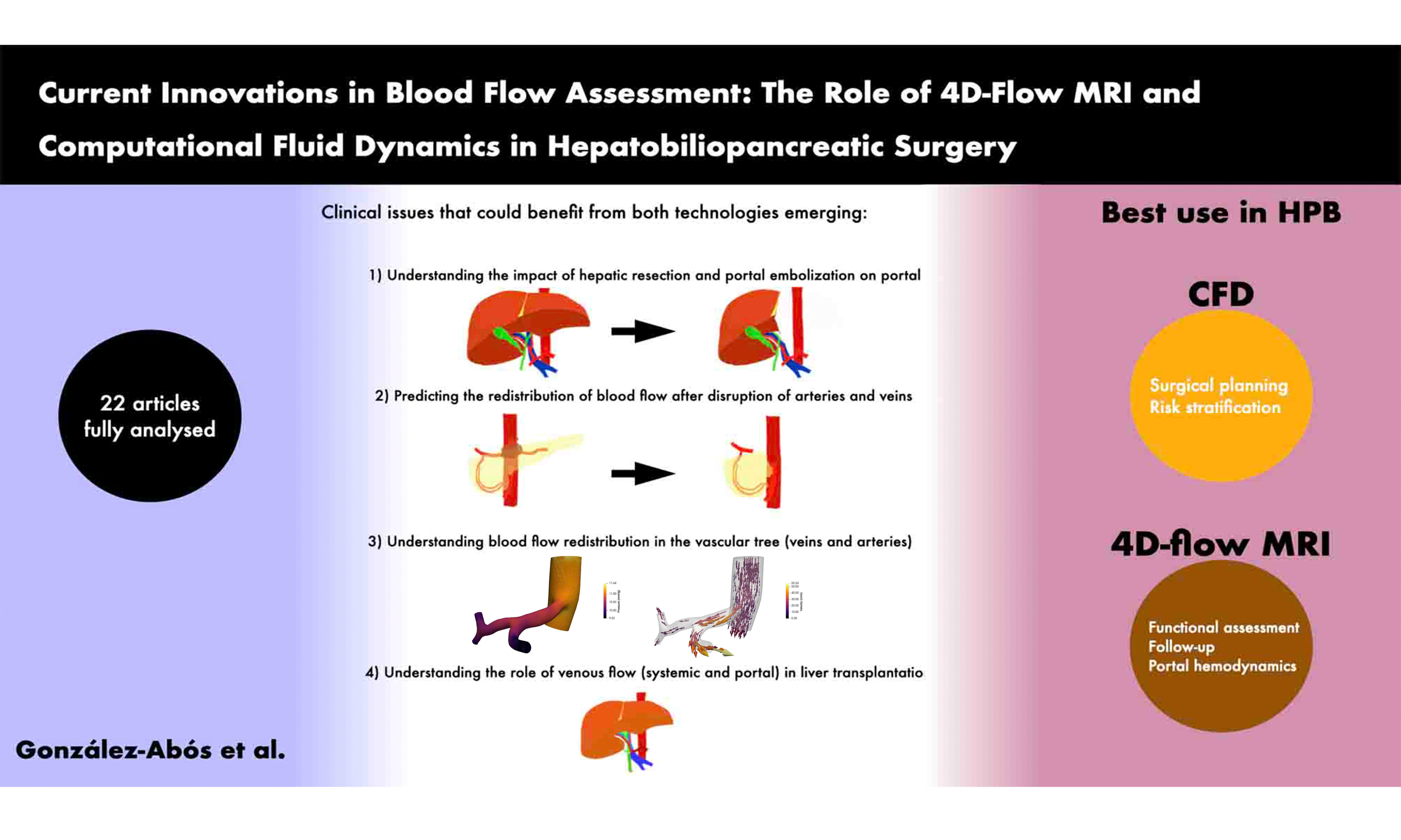

Aim: Insufficient assessment of post-surgical organ perfusion in hepatobiliopancreatic surgery can lead to serious complications. Consequently, various technological solutions have been developed to achieve non-invasive and accurate blood flow assessment. This article aims to evaluate the current state of four-dimensional flow magnetic resonance imaging (4D-flow MRI) and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) technologies in assessing vascular blood flow within this surgical field.

Methods: A comprehensive literature search using ClinicalTrials.gov and PubMed/MEDLINE was performed; articles published between 2015 and 2025 were included. Broad search terms, including “blood flow measurement”, “4D-flow MRI”, or “computational fluid dynamics” and “abdomen” or “liver”, were utilized.

Results: Twenty-two studies were analyzed in detail. Nineteen focused on vascular conditions surrounding the liver, with 15 assessing venous flow and five evaluating the hepatic artery. Additional hemodynamic features analyzed included blood velocity, pressure, and particle distribution. The clinical applications investigated were: portal vein embolization (1), venous anastomosis (3), liver resection (2), portal hypertension (2), transarterial radioembolization (2), transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (4), and liver fibrosis (1). Notably, only CFD facilitated the simulation of prospective hemodynamic conditions (2).

Conclusion: Both 4D-flow MRI and CFD technologies facilitate the accurate study of blood flow dynamics within the supramesocolic compartment. Furthermore, CFD enables the simulation of prospective vascular conditions, establishing its potential as a preoperative planning tool. However, further research is required to fully validate the clinical utility of CFD in this surgical context.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, surgery remains the most effective curative treatment for many malignant liver and pancreatic diseases. However, these procedures are often extensive and associated with a high risk of postoperative complications[1-3]. In addition, the aging population and rising life expectancy, combined with advancements in surgery, anesthesia, and minimally invasive techniques, have led to an increase in the number of major surgeries performed on patients with multiple comorbidities[4]. Moreover, the growing prevalence of obesity and arteriosclerosis in the population increases the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage during abdominal surgeries. In such cases, a thorough preoperative vascular assessment is essential to evaluate potential alterations in vascular flow during the procedure.

Insufficient assessment of post-surgical organ perfusion can lead to serious complications. Studies have reported that anatomical vascular variations occur in up to 20% of patients[5] and preoperative stenosis of relevant arteries is also common[6]. These conditions can significantly disrupt vascular flow to adjacent organs, potentially resulting in life-threatening complications[6,7].

Currently, percutaneous angiography is the only well-established method for safely assessing vascular abnormalities, particularly in the evaluation of arterial diseases. This procedure involves catheterizing a peripheral artery, such as the femoral or radial, to access the arterial vascular system. However, it carries a significant bleeding risk of up to 2.5% and a notable mortality rate up to 2%[8,9].

On the other hand, various technological solutions have been developed for assessing intraoperative blood flow. To achieve non-invasive and accurate blood flow assessment, four-dimensional flow magnetic resonance imaging (4D-flow MRI) and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) have emerged as advanced technologies. These methods are increasingly accessible to clinicians for detailed blood flow analysis[10]. On the one hand, 4D-flow MRI utilizes time-resolved three-dimensional phase-contrast MRI with three-directional flow velocity encoding. This technique enables comprehensive, in vivo measurement of three-dimensional blood flow dynamics within the heart and large vessels[11]. On the other hand, CFD is a branch of fluid mechanics that employs numerical methods and algorithms to analyze and simulate fluid behavior[12]. CFD enables the simulation and visualization of fluid movement and its interactions with surrounding surfaces[13]. The development of computers has enabled multiscale simulations for studying hemodynamics in small and medium-sized vessels. These simulations allow for the analysis of fluid characteristics such as pressure, velocity, and flow[10]. Both technologies have been widely used in the study of cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease, large vessel disease, and cerebral aneurysms[10]. However, their application in other medical fields has been limited.

In theory, the implementation of CFD could be extremely useful for preoperative studies of hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) procedures because they involve arteries and veins that are essential for life and can be resected and reconstructed[14]. Furthermore, in the splanchnic territory, two not completely understood mechanisms protect the liver from flow insufficiency: (1) Connection between the celiac trunk (CT) and superior mesenteric artery (SMA), where these arteries compensate blood flow in case of insufficiency of one of the systems[5]; (2) Hepatic arterial buffer response (HABR), which regulates hepatic inflow between the common hepatic artery (CHA) and portal vein, to ensure enough blood flow[15].

Recent advances in computational modeling have opened up new possibilities for preoperative planning in complex abdominal surgeries. On the one hand, CFD has been used to study different vascular behaviors in the hepatobiliary territory, particularly the impact of hepatic or venous resections on portal vein flow[16-18].

On the other hand, a recent pilot study by González-Abós et al. demonstrated the feasibility and accuracy of using CFD to predict hepatic arterial flow redistribution during pancreaticoduodenectomy[19]. In their work, patient-specific models based on preoperative computed tomography scans and intraoperative flow data were used to simulate different surgical scenarios, including gastroduodenal artery (GDA) and CHA clamping. The model showed excellent predictive performance, with 100% accuracy after GDA clamping and 80% after CHA clamping. It also successfully adapted to cases with anatomical variations and CT stenosis, without requiring prior model retraining. These findings suggest that CFD may serve as a non-invasive tool to anticipate vascular complications and support personalized surgical planning in HPB procedures. For now, there are no published studies regarding the usefulness of CFD for assessing HABR.

This article aims to evaluate the current state of 4D-flow MRI and CFD technologies in assessing abdominal vascular blood flow, particularly in the context of major hepatobiliopancreatic (HPB) surgery, and to explore potential future directions for these techniques.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Our aim was to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the current literature concerning the use of 4D-flow MRI and CFD for the assessment of vascular blood flow in the context of major HPB surgery. The methods used to identify, select, and extract data from relevant studies were predefined and followed a structured, transparent, and reproducible process.

Eligibility criteria

We included original studies that assessed blood flow in the abdominal vasculature using either 4D-flow MRI or CFD, specifically within clinical or translational research relevant to HPB surgery. Eligible studies had to meet the following criteria:

• Study type: Clinical trials, observational studies (prospective or retrospective), cohort studies, feasibility studies, or conference abstracts with sufficient methodological detail.

• Population: Human participants (adult or pediatric) undergoing assessment of vascular structures in the abdomen, particularly liver, pancreas, or portal circulation, regardless of surgical status (preoperative, postoperative, or intraoperative).

• Intervention: Use of 4D-flow MRI and/or CFD as a primary or secondary technique to evaluate blood flow and/or hemodynamics.

• Language: Only studies published in English were considered.

• Publication date: Studies published from January 1, 2015, to May 1, 2025.

• Availability: Full-text access was required for inclusion, although detailed conference abstracts were considered if they provided sufficient information regarding methodology and outcomes.

Studies were excluded if they:

• Focused on non-human subjects or were conducted in veterinary contexts.

• Did not employ 4D-flow MRI or CFD as a method of vascular flow assessment.

• Were review articles, opinion pieces, editorials, or commentaries without original data.

• Belonged to fields outside biomedical sciences (e.g., purely engineering or physics simulations without clinical correlation).

Information sources

We systematically searched the following databases:

1. PubMed/MEDLINE - chosen for its comprehensive indexing of biomedical literature.

2. ClinicalTrials.gov - included to identify ongoing or completed clinical studies that might not yet be published.

These databases were selected due to their accessibility, relevance to the medical field, and alignment with the scope of the review.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with an experienced medical librarian to ensure appropriate sensitivity and specificity. We used a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords to capture the broadest range of relevant literature. The core search terms included:

• “Blood flow measurement” OR “blood flow monitoring”

• AND “4D MRI” OR “4D-flow MRI” OR “four-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging”

• OR “computational fluid dynamics”

• AND “abdomen” OR “liver” OR “portal vein” OR “hepatic artery”

Boolean operators and truncation were applied to refine the search results. Search filters were applied to include only studies published in English from 2015 onward.

The final search was conducted on May 1, 2025. In addition, we manually reviewed the reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles to identify any additional eligible publications not captured by the electronic search.

Study selection

All search results were imported into a web-based tool for managing systematic reviews. Duplicate records were identified and removed automatically, followed by a manual check for accuracy.

Three independent reviewers (CGA, SA and RM) screened all titles and abstracts for relevance based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies deemed potentially eligible underwent full-text review. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion, and a fourth reviewer (FA) was consulted in cases of persistent disagreement.

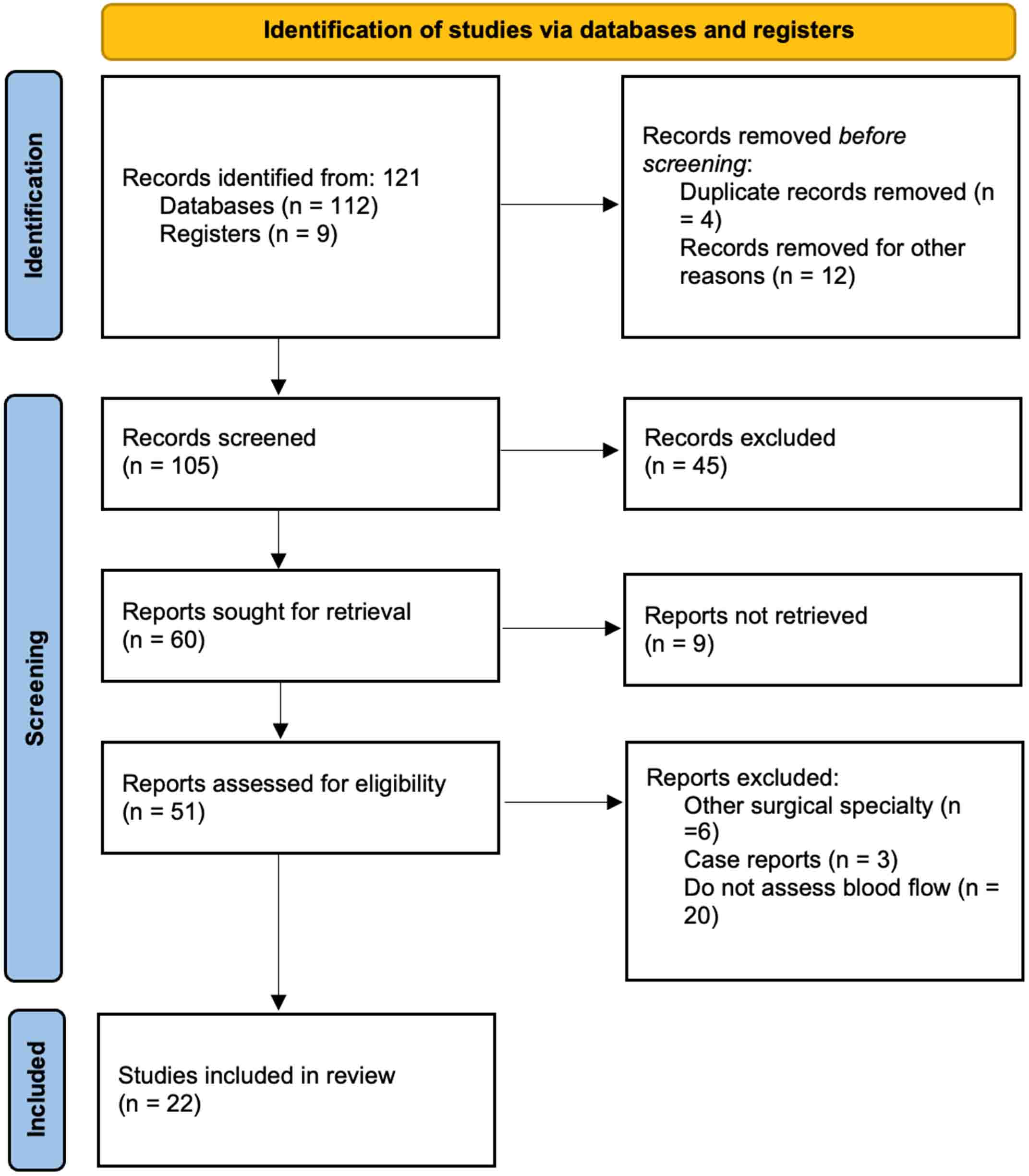

Figure 1[20] has been included to illustrate the process of study selection, including the number of studies screened, excluded, and ultimately included in the final analysis.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the analyzed studies, built following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations by Page et al. (BMJ 2021)[20].

Data extraction

Data from the included studies were extracted independently by the same three reviewers using a standardized data extraction form created in Microsoft Excel. The form was pilot-tested on five randomly selected studies and revised accordingly to ensure consistency across reviewers.

The following variables were extracted from each included study:

• Bibliographic information: First author, year of publication, country.

• Study design: Type (e.g., prospective, retrospective, case-control), setting, and duration.

• Population characteristics: Sample size, age range, gender distribution, clinical condition (e.g., cirrhosis, tumor resection).

• Technologies used: Details of 4D-flow MRI (magnet strength, velocity encoding parameters, software) or CFD (modeling technique, boundary conditions, assumptions, validation procedures).

• Objectives and outcomes: Primary purpose of using 4D-flow MRI or CFD, measured outcomes (e.g., flow velocity, pressure gradients, wall shear stress), and main findings.

• Sponsorship and funding: Any reported funding sources or declared conflicts of interest.

Data discrepancies were resolved by cross-verification among the reviewers. When key data were missing, attempts were made to contact the corresponding authors via email.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Given the heterogeneity of study designs and the exploratory nature of much of the literature in this field, a conventional single risk-of-bias tool was not applicable. Therefore, a domain-based quantitative risk of bias assessment was performed using an adapted framework inspired by the ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions), QUADAS-2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2) and PROBAST (Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool) tools, which are established for observational, diagnostic and predictive modeling studies.

Each study was assessed for the following domains:

• Clarity of research question and objectives (D1)

• Appropriateness of the data collection and analysis methods (D2)

• Transparency in describing imaging protocols and CFD modeling (D3)

• Validation strategy and reference standards (D4)

• Statistical analysis and sample size adequacy (D5)

• Clinical relevance and translational potential (D6)

Domain-level judgements were converted into numerical scores (low, moderate, or high risk of bias) in order to derive a cumulative and normalized risk-of-bias index for each study. Studies were not excluded based on quality score alone, but the risk of bias was considered when interpreting findings.

Data synthesis

Given the diversity of technologies, populations, and endpoints, a meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, a narrative synthesis approach was used. Studies were grouped according to:

1. Modality used (4D-flow MRI vs. CFD)

2. Anatomical region assessed (e.g., liver, portal vein, pancreas)

3. Clinical context (e.g., preoperative planning, surgical simulation, diagnosis of portal hypertension)

We identified thematic patterns regarding the role of these technologies in understanding abdominal hemodynamics, their advantages and limitations, and their clinical relevance in HPB surgery.

RESULTS

A total of 105 potentially relevant clinical trials and articles were identified through electronic searches in the specified databases; of them, 45 were excluded during initial screening and another 9 were not retrieved. Of the remaining 51 studies, 29 were excluded after full-text evaluation: 3 were case reports[15-17], 6 were related to other surgical specialties, and 20 did not assess blood flow. Ultimately, 22 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included for further analysis. The review flow diagram illustrating the literature search and study selection process is shown in Figure 1[20].

All included studies are described in Table 1[10,16-19,21-37]. Out of the 22 analyzed studies, only nine directly investigate blood flow in various vascular structures[16,19,22,26,27,29,35-37]. Among these, 19 studies focused on studying vascular conditions around liver vasculatures, including venous blood flow (15) or arterial blood flow (5), while Sugiyama et al. analyzed SMA blood flow characteristics[30]. Kamada et al. investigated blood flow patterns across various settings[10].

Summary of the analyzed studies (2015-2025), including their primary objectives and key conclusions

| Study | Year of publication | Short description |

| Stankovic et al.[26] | 2015 | This study utilized K-t GRAPPA accelerated non-contrast 4D-flow MRI to analyze liver vasculature, including both arteries and veins. It demonstrates that MRI is a feasible method for evaluating liver vasculature after TIPS stent placement and that it effectively detects TIPS stenoses by assessing shunt flow. |

| Bannas et al.[27] | 2016 | This study evaluates liver venous blood flow before and after TIPS placement using 4D-flow MRI. It shows that 4D-flow MRI effectively monitors changes in blood flow following TIPS insertion |

| Owen et al.[28] | 2018 | This study aims to investigate the feasibility of 4D-flow MRI for detecting patency, stenosis, and occlusion of TIPS stents. While venograms were used to confirm stenosis, the study included only two patients, and none of them exhibited signs of clinical dysfunction. |

| Cox et al.[29] | 2019 | This study uses MRI to analyze alterations in liver blood flow. It demonstrates that dynamic changes in liver perfusion and blood flow can be effectively measured with MRI. |

| Sugiyama et al.[30] | 2020 | This study compares the use of 4D-flow MRI and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) for analyzing the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and concludes which method is more effective for measuring blood flow. It identifies the optimal approach for assessing the SMA while minimizing turbulence in the arterial section. |

| Tabei et al.[31] | 2020 | This study examines the application of CFD for assessing hepatic artery blood flow and the distribution of intra-arterial particles. It demonstrates that resistance in the downstream vasculature significantly influences hepatic artery hemodynamics, affecting key parameters such as velocity fields, pressure fields, and blood flow streamline trajectories. |

| Du et al.[32] | 2021 | This study employs CFD to analyze hepatic hemodynamics in patients with early biliary atresia compared to a normal population. It reveals that hepatic artery hemodynamics are disrupted in patients with liver fibrosis. |

| Kamada et al.[10] | 2022 | The application of 4D MRI and CFD in analyzing blood flow in vascular diseases offers distinct benefits and limitations for each technology. This comparison includes their use in evaluating conditions affecting the abdominal aorta. |

| Aramburu et al.[33] | 2022 | This study provides an overview of CFD modeling from a clinical perspective, specifically applied to liver radioembolization. It also emphasizes the use of transcatheter therapies in this context. |

| Bane et al.[34] | 2022 | This study compares various measurement techniques used with 4D-flow MRI to investigate blood flow behavior in abdominal vessels. |

| Xie et al.[35] | 2023 | This study uses CFD to analyze blood flow rates in the portal veins and demonstrates that the pressure drop in the main portal vein increases linearly with the blood velocity in the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). It suggests that blood from the SMV likely flows to the right liver lobe, while blood from the splenic vein tends to flow to the left lobe. |

| Song et al.[18] | 2023 | This study demonstrates the use of CFD analysis for assessing postoperative risk in liver donor patients. CFD enables the prediction of future blood flow patterns, blood pressure, and overall blood behavior following hepatectomy. |

| Hyodo et al.[36] | 2023 | The study evaluates the use of 4D-flow MRI for assessing portal blood flow and segmental blood flow changes following portal embolization. It concludes that MRI effectively detects increases in blood flow after portal vein embolization. |

| Moon et al.[37] | 2023 | This study uses 4D-flow MRI to evaluate variations in portal vein blood flow with age. It demonstrates that both volume and velocity in the portal vein peak around the age of 43. |

| Ito et al.[22] | 2023 | This study analyzes the capacity of CFD to predict hepatic venous outflow obstruction following a living donor liver transplant, prior to the onset of clinical symptoms. |

| Sakamoto et al.[17] | 2023 | This study analyzes the impact of different technical solutions for 1 to 2 veins anastomosis, using CFD to define the best approach to the problem. |

| Sakamoto et al.[21] | 2024 | This study demonstrated the physical explanation for an increase in intraoperative bleeding secondary to the increase of pressure in the middle hepatic vein during hemi-hepatectomy, due to its morphology. |

| Karam et al.[25] | 2024 | This study analyzes portal blood flow distribution in patients with portal hypertension to detect its distribution to gastroesophageal varices and assess its bleeding risk. |

| Riedel et al.[23] | 2024 | This study creates CFD simulations from 4D-flow MRI that enabled not only noninvasive portosystemic pressure gradient estimation but also localization of the underlying stenoses in the portal system of participants with TIPS. |

| Zheng et al.[24] | 2024 | 4D-flow MRI allowed for the detection of splenorenal and gastrorenal shunts, classifying their importance. These findings can be useful to formulate specific therapeutic strategies for portal hypertension. |

| Sakamoto et al.[16] | 2025 | This study uses CFD to assess the impact of SMV-PV anastomosis shape on portal blood flow and its impact on patient nutritional status. |

| González-Abós et al.[19] | 2025 | This study develops a CFD model that aims to predict common hepatic artery blood flow after gastroduodenal artery section in pancreaticoduodenectomy. |

Blood velocity was assessed in two ways: in vivo measurements using 4D-flow MRI and simulations using CFD in silico models. Out of the studies reviewed, seven used 4D-flow MRI to analyze blood velocity across various vascular structures. Meanwhile, seven CFD studies evaluated blood velocity in different vascular structures, including hepatic artery (3)[19,31,33], portal vein (4)[16-18,35] and SMA (1)[30].

The results of these studies were grouped according to clinical scenarios. See Supplementary Table 1:

• Portal vein embolization: One manuscript investigates the impact of portal venous embolization (PVE) on portal blood flow and future liver remnant using 4D-flow MRI[36]. In all cases, MRI demonstrated a decrease in blood flow velocity in the portal vein following PVE, consistent with the anticipated outcomes.

• Liver resection: One article evaluates portal vein blood flow before and after major hepatectomy in living liver donors[18]. The study compared preoperative and postoperative portal vein pressures and found that an increased postoperative pressure difference is associated with poorer outcomes and a deterioration in the donor’s postoperative recovery[18].

• Portal hypertension: Two articles analyzed the behavior of venous blood flow in patients with portal hypertension, detecting relevant portosystemic shunts and their clinical impact. The 4D-flow MRI was able to detect the risk of bleeding from gastroesophageal varices by analyzing porto-mesenteric blood flow[25].

• Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: Four articles analyze the hemodynamics of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement in cirrhotic patients: Bannas et al. studied seven patients with portal hypertension and refractory ascites[27]. They analyzed superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and portal vein pressures before and after TIPS placement and found that 4D-flow MRI effectively detected TIPS patency[27]. Stankovic et al. evaluated arterial and venous hemodynamics in 11 patients before and after TIPS placement, demonstrating an increase in blood flow following the procedure[26]. Owen et al. examined 23 patients following TIPS placement; their findings demonstrated that altered flow velocity and turbulence detected via 4D-flow MRI could serve as indicators of TIPS stenosis[28]. At least, Riedel et al developed CFD simulations based on 4D-flow MRI images, enabling noninvasive pressure estimation and localization of the underlying stenoses in the portal system of participants with TIPS[23].

• Transarterial radioembolization: Two studies examined the applicability of CFD for analyzing liver transarterial radioembolization[31,33]. This procedure involves injecting microspheres loaded with chemotherapeutic agents or radioactive yttrium-90 (90Y) through a catheter into the hepatic artery to target liver tumors[32]. Taebi et al. developed a computational model of the liver’s arterial vascularization, including 46 outlets and sub-segmental arterial branches, to recreate realistic physiological conditions[31].

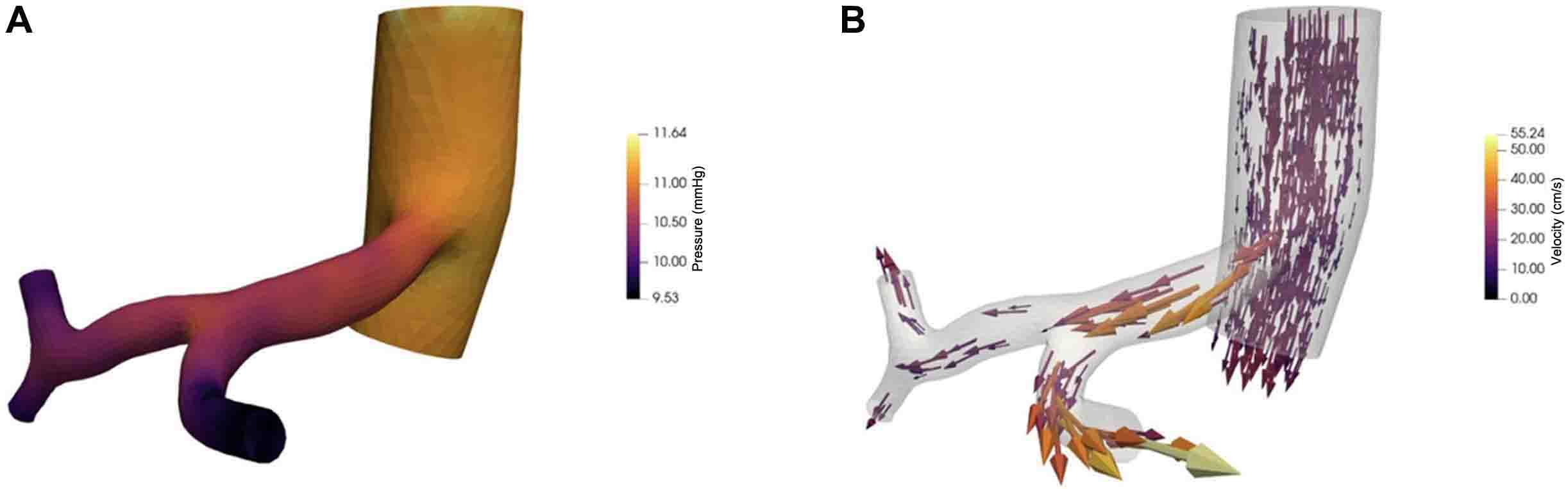

• Simulation of future conditions: Only CFD-related publications demonstrated the capability to simulate future conditions. Song et al. simulated a major hepatectomy for a living donor by modeling the resection of the portal branch associated with the removed lobe[18]. This simulation predicted postoperative scenarios, including pressure changes in the remaining portal vein and blood flow distribution based on the angle of sectioning the resected portal branch[18]. González-Abós et al. predicted blood flow modification in proper hepatic artery after GDA or CHA clamping, showing a high accuracy of their software[19]. Figure 2 shows an example of CFD use for studying blood flow in the CT (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. CFD model of the celiac trunk arising from the aorta, including the splenic artery and the common hepatic artery, as well as its bifurcation into the proper hepatic artery and the gastroduodenal artery. (A) Blood pressure distribution; (B) Blood flow velocity and its vector distribution. Model created with Ayla computing code[38]. CFD: Computational fluid dynamics.

• Analyzing blood flow disturbances due to morphologic vessels modification: Sakamoto et al. published several studies evaluating blood flow associated with different technical approaches to venous anastomosis and examining how anastomotic morphology influences subsequent blood flow[16,17,21,22].

At least, the quantitative risk-of-bias assessment revealed predominantly low-to-moderate methodological risk across the included studies (see Table 2). Normalized risk-of-bias scores ranged from 0.00 to 0.58, with higher scores primarily observed in early feasibility studies, small pilot cohorts and computational analyses that lacked external clinical validation. The most frequent sources of potential bias across domains were related to patient selection, limited sample size, simplified haemodynamic modeling assumptions and the absence of robust reference standards. In contrast, studies based on 4D-flow MRI with prospective designs and clearly defined imaging protocols demonstrated a consistently low risk of bias across all domains. No study was excluded based on its risk-of-bias score. Instead, these quantitative results were used to contextualize the strength and maturity of the available evidence.

Quantitative risk of bias assessment of included studies

| Study | Year | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | Score | RoB norm |

| Stankovic et al.[26] | 2015 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0.33 |

| Bannas et al.[27] | 2016 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0.33 |

| Owen et al.[28] | 2018 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 0.58 |

| Cox et al.[29] | 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0.25 |

| Sugiyama et al.[30] | 2020 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.08 |

| Taebi et al.[31] | 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0.25 |

| Du et al.[32] | 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0.50 |

| Aramburu et al.[33] | 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 0.58 |

| Bane et al.[34] | 2022 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0.25 |

| Kamada et al.[10] | 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 0.58 |

| Xie et al.[35] | 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0.50 |

| Song et al.[18] | 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0.50 |

| Hyodo et al.[36] | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Moon et al.[37] | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Ito et al.[22] | 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0.50 |

| Sakamoto et al.[17] | 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0.50 |

| Sakamoto et al.[21] | 2024 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0.50 |

| Karam et al.[25] | 2024 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.33 |

| Riedel et al.[23] | 2024 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0.17 |

| Zheng et al.[24] | 2024 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.33 |

| Sakamoto et al.[16] | 2025 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0.50 |

| González-Abós et al.[19] | 2025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.08 |

DISCUSSION

In this review, we highlight how non-invasive blood flow assessment has the potential to revolutionize the evaluation of blood flow dynamics in hepatobiliary and pancreatic (HPB) diseases[10,18,19,29]. Our research suggests that CFD and 4D-flow MRI are highly complementary and compatible methods for studying blood flow dynamics[10]. The 4D-flow MRI allows accurate assessment of blood flow and evaluation of organ anatomy, while CFD provides simulation capabilities that are not currently used in daily clinical practice.

Accurate blood flow assessment helps to understand and manage different cardiovascular conditions, and non-invasive techniques have gained significant attention in recent years. These methods - such as Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and CFD - enable a comprehensive study of the vascular system without invasive procedures[39,40]. This shift towards non-invasive techniques is driven by the growing prevalence of cardiovascular disease globally, which contributes to a substantial burden of morbidity and mortality. Non-invasive blood flow assessment offers several benefits: reduced patient risk, shorter recovery times, and lower costs[41]. Consequently, these methods have become crucial for diagnosing and managing conditions such as atherosclerosis, heart failure, and peripheral arterial disease[41].

However, the application of these techniques to the abdominal vasculature remains significantly underdeveloped. While non-invasive blood flow assessment has become a well-established practice in cardiovascular disease, its application to the abdomen has lagged behind[41]. This discrepancy arises from several challenges, including the abdominal movement secondary to respiratory motion, complex anatomy and diverse blood flow patterns within the abdominal cavity, which involve multiple vessels supplying various organs and considerable inter-individual variability[7,34,42]. Respiratory motion remains a significant technical challenge in abdominal 4D-flow MRI. It can cause blurring, phase inconsistencies and errors in flow quantification, particularly in small vessels and regions with low velocity[34]. Several strategies, including respiratory gating, navigator-based acquisitions, self-gated sequences and retrospective motion correction approaches, have been proposed to address this issue[34]; however, it usually results in longer acquisition times and reduced scan efficiency. More recent developments that combine accelerated imaging, free-breathing acquisitions and motion-resolved or motion-corrected reconstructions show promise in balancing image quality and clinical feasibility[42]. Despite all these challenges, there is growing recognition within the medical community of the need to extend the benefits of non-invasive blood flow assessment to the abdominal region. This is also due to increased awareness that functional and dynamic vascular assessment is of utmost importance, especially in HPB surgery.

Advances in imaging technology, particularly the development of 4D-flow MRI and the emergence of CFD, are providing new, non-invasive methods for assessing abdominal blood flow. According to the reviewed literature, both techniques effectively measure blood flow in major abdominal vessels, including the hepatic artery and portal vein. MRI enables in vivo measurement of blood flow within these structures, and has been utilized to evaluate structural changes, blood flow alterations, and perfusion patterns within the liver[43]. CFD allows for the creation of detailed in-silico models to further analyze blood flow behavior, and has emerged as a powerful tool capable of significantly enhancing non-invasive abdominal blood flow assessment[16-19,30,35]. By integrating imaging data with sophisticated algorithms, CFD enables the simulation of blood flow dynamics within abdominal vessels and predicts how different pathologies might affect organ perfusion[33]. In fact, there is no well-established technology capable of simulating postoperative blood flow conditions in real clinical practice. According to the reviewed papers analyzing CFD, this technology seems to be an interesting tool for studying supramesocolic compartment blood flow in a silico model. However, some issues have to be considered: (1) the non-Newtonian behavior of blood can alter both primary and secondary flow patterns[31]; and (2) it is not possible to fully capture how boundary conditions influence detailed flow characteristics such as velocity fields, flow lines, and particle trajectories[31].

In clinical practice, several issues arise that require addressing with these new technologies: (1) Understanding the impact of hepatic resection on postoperative portal flow; (2) Predicting the redistribution of blood flow after disruption of arteries and veins; (3) Understanding particle redistribution in cases of intravascular treatment; (4) Understanding the role of venous flow (systemic and portal) in liver transplantation. Now, we will discuss how these two technologies can help to solve these problems in hepatobiliary surgery.

Understanding the impact of hepatic resection and portal embolization on portal flow

On the one hand, 4D-flow MRI provides accurate assessments of portal branch blood flow, enabling detailed study of portal blood flow alterations following segmental portal embolization, TIPS placement, or according to different patient parameters, such as age or weight. On the other hand, CFD can also assess portal blood flow features, but it requires preprocessing after image acquisition. It is able to analyze the reasons for certain blood flow behaviors and to predict modifications by simulating the future anatomy before the surgical procedure. It also appears capable of predicting postoperative complications after liver resection in living liver donors, relating differences in portal pressure to liver recovery, based on total bilirubin levels.

Predicting the redistribution of blood flow after disruption of arteries and veins

CFD enables the study of various conditions that may not be present in the current images by modifying the geometry of the model. This flexibility allows the simulation and analysis of hypothetical scenarios and the impact of different pathological changes on blood flow dynamics[10]. These models can be employed for surgical planning or for simulating future scenarios.

The splanchnic compartment has its own unique arterial and venous systems. The liver acts as an interconnecting node between the portal and systemic venous systems. There is also an interconnection between CT and SMA, ensuring a sufficient blood supply if either system is insufficient. Several studies have demonstrated the potential of CFD to predict future blood flow behavior in this anatomic region:

1. CFD models have shown strong adaptability in simulating portal veins, being able to predict portal blood flow behavior following hepatectomy in living liver donors, with postoperative virtual differential pressure showing good correlation with clinical indicators[18].

2. CFD models showed their capability to detect morphological alterations, such as stenosis, in portal vein-SMV anastomoses after pancreatic surgery, which modify blood flow and influence postoperative patient outcomes[16].

3. CFD models predict blood flow redistribution in CHA after GDA clamping in pancreaticoduodenectomy, detecting insufficient liver arterial inflow[19].

4. Preliminary studies hypothesize that CFD can help describe the operation of the HABR system and its impact on pancreatic and hepatic surgery[19].

However, none have yet used these predictions to directly modify patient clinical management. Prediction of insufficient blood flow after pancreatic surgery or of imbalanced blood flow in liver transplantation would be a revolutionary tool that would facilitate the use of mitigation strategies to avoid severe vascular complications after these major procedures[44-47].

Understanding particle redistribution in cases of intravascular treatment

On the one hand, 4D-flow MRI has been demonstrated to be useful and accurate in studying current blood flow distribution in patients with portal venous hypertension by detecting the presence and severity of portosystemic shunts, and also in predicting the bleeding risk of gastroesophageal varices[23-25].

On the other hand, CFD allows the study of the distribution of liquid or gas particles in the vascular system. It can be used to design strategies to improve the results of intra-arterial treatment[27,31]. Intravascular treatments allow hepatic lesions to be treated selectively, avoiding toxicity to other body cells and reducing the impact of future liver remnant treatment, for example, in the treatment of liver colorectal metastasis.

Using CFD to study particle distribution in the portal venous confluence also appears to provide insight into blood distribution in the portal bifurcation. This information could help us to understand how diseases are distributed between liver lobes in the future[35].

The study of portal flow with CFD can also allow understanding of the reasons for critical vascular problems due to anomalous vein position or vascular stenosis. CFD allows planning of different technical solutions to solve these vascular problems related to anatomical morphology[17].

Understanding the role of venous flow (systemic and portal) in liver transplantation

Venous inflow and outflow are strongly correlated in liver transplantation, and a problem in either can influence graft function or survival. The study of blood flow behavior in these venous systems can help detect future clinical problems[22]. CFD seems a good tool for assessing the interaction between these two systems, allowing prediction of future complications before their onset, solely by analyzing blood flow behavior after liver transplantation, probably including all three vascular anastomoses.

In summary, 4D-flow MRI and CFD address different yet complementary clinical needs in HPB surgery. While 4D-flow MRI provides direct, patient-specific, in vivo flow measurements, making it particularly well suited for functional assessment and postoperative follow-up, CFD enables pressure estimation and virtual surgical planning, which cannot be achieved with MRI alone (see Table 3). Therefore, the choice of technique should be driven by the clinical question rather than by methodological superiority.

Summary of the dimensions of 4D-flow MRI and CFD and their clinical impact

| Dimension | 4D-flow MRI | Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) | Evidence from included HPB studies | Clinical interpretation |

| Nature of measurement | Direct in vivo velocity and flow measurement | Physics-based simulation from imaging-derived geometry | 4D-flow: Stankovic 2015; Bannas 2016; Hyodo 2023; Karam 2024. CFD: Sakamoto 2023-2025; Ito 2023; González-Abós 2025 | MRI reflects actual physiology; CFD explores what-if scenarios |

| Primary outputs | Velocity fields, volumetric flow, flow distribution | Velocity, pressure gradients, and wall shear stress | CFD pressure indices: Song 2023; Riedel 2024 | CFD uniquely provides pressure-related metrics |

| Accuracy (validation) | Good agreement with Doppler/PC-MRI (errors ~5%-15%) | Highly dependent on boundary conditions and assumptions | Kamada 2022 directly compares both approaches | MRI accuracy is limited by spatial/temporal resolution |

| Reproducibility | Moderate-high; affected by sequence and segmentation | High once the model is fixed | Bane 2022; Kamada 2022 | CFD is deterministic; MRI is subject to physiological variability |

| Sensitivity to hemodynamic changes | High (postprandial, TIPS, PVE) | Indirect (via BC changes) | Cox 2019; Stankovic 2015; Hyodo 2023 | MRI is ideal for functional assessment |

| Pressure estimation | Not directly measurable | Directly computed | Song 2023; Riedel 2024 | Key advantage of CFD in surgical planning |

| Cost - acquisition | High (MRI scanner + long sequences) | Low-moderate (CT/MRI already available) | Not explicitly reported in studies | MRI ≈ €400-800/exam; CFD uses routine imaging |

| Cost - post-processing | Moderate (specialized software, trained operator) | High (segmentation + simulation time) | Kamada 2022; González-Abós 2025 | CFD requires engineering expertise |

| Time to results | Same day (30-60 min acquisition + processing) | Hours to days | González-Abós 2025 | MRI is faster for clinical workflow |

| Operator dependency | Moderate | High (model setup, BC selection) | Taebi 2020; Kamada 2022 | CFD results vary with modeling choices |

| Integration into clinical workflow | Limited but improving | Currently limited | Bannas 2016; González-Abós 2025 | Neither is yet routine in HPB surgery |

| Preoperative planning | Limited predictive power | Strong (virtual surgery, morphology testing) | Sakamoto 2023-2025; Ito 2023 | CFD is superior for surgical decision-making |

| Postoperative assessment | Excellent | Moderate | Hyodo 2023; Owen 2018 | MRI is better for follow-up |

| Main limitations | Long acquisition, low spatial resolution, and cost | Modeling assumptions, lack of standardization | Kamada 2022; Aramburu 2022 | Complementary, not competing tools |

| Best use case in HPB | Functional assessment, follow-up, portal hemodynamics | Surgical planning, risk stratification | Consensus across included studies | Combined use is increasingly proposed |

At present, there is not much evidence regarding the costs associated with these two technologies in the supramesocolic compartment. Nevertheless, a preliminary cost analysis suggests that 4D-flow MRI and CFD have substantially different economic and operational profiles when applied to HPB surgery (see Table 4). When added to an MRI examination that has already been indicated as part of the preoperative workup, the incremental cost of 4D-flow MRI is relatively low, mainly due to additional scanner time, post-processing, and software licensing costs. In contrast, CFD is a more resource-intensive intervention that requires specialized personnel and modeling expertise, as well as longer turnaround times, especially when multiple surgical scenarios are simulated.

Tentative cost analysis for the implementation of 4D-flow MRI and CFD in the hepatobiliopancreatic setting

| Dimension | 4D-flow MRI (incremental) | CFD - single scenario | CFD - multi-scenario |

| Baseline imaging assumed | MRI + CT already indicated | Contrast-enhanced CT already indicated | Contrast-enhanced CT already indicated |

| Additional acquisition cost (€) | 80-200 | 0 | 0 |

| Post-processing & analysis (€) | 60-170 | 300-700 | 600-1,200 |

| Software & infrastructure (€) | 20-150 | 50-200 | 100-300 |

| Reporting & interpretation (€) | 20-50 | 150-300 | 200-400 |

| Total incremental cost (€/patient) | ~200-500 | ~800-1,500 | ~1,500-3,500+ |

| Time to results | Same day | 1-2 days | 2-5 days |

| Pressure/gradient estimation | No | Yes | Yes |

| Virtual surgical planning | No | Limited | Yes |

| Scalability in public systems | Moderate-high | Moderate | Low-moderate |

| Best clinical indication | Functional assessment, follow-up | Hemodynamic risk assessment | Complex surgical planning |

However, these higher upfront costs must be considered alongside the unique capabilities of CFD, such as non-invasive pressure estimation and virtual surgical planning, which cannot be achieved with MRI alone. CFD may be selectively justified in complex cases where optimizing the surgical strategy could reduce the risk of severe postoperative complications. Additionally, it should be noted that the computational cost of CFD simulations decreases substantially with scale[48,49]. When simulations are run on shared high-performance computing infrastructures, multiple patient-specific models can be executed in parallel, reducing the marginal cost of each simulation. In such settings, solver-related costs become a relatively minor component of the total cost per patient.

Nevertheless, the overall cost of CFD is still largely driven by labor-intensive steps, including image segmentation, model setup, defining boundary conditions, and clinical interpretation[19]. Consequently, although computational scalability improves the economic feasibility of CFD at institutional or health system levels, significant cost reductions are primarily achievable through workflow automation rather than increased computational throughput alone.

However, the absence of standardized cost-effectiveness analyses and the heterogeneity of current workflows prevent definitive economic conclusions from being drawn, emphasising the need for prospective studies to evaluate clinical impact, resource utilization, and downstream cost savings.

The future perspectives of these two technologies may be directed toward their complementary use not only for the study of blood flow dynamics, but also to obtain a detailed preoperative assessment of the patient’s future condition after surgery. The high-quality images and knowledge of the initial blood flow provided by 4D-flow MRI could allow the generation of a precise and individualized in silico CFD model for each patient, on which future vascular conditions could be simulated and the distribution and characteristics of postoperative flow analyzed.

The use of CFD from high-quality images could reduce post-operative complications in HPB:

• Avoid cases of “small for flow” in liver resection: An excessive portal inflow relative to the liver remnant functional capacity produces a hemodynamic mismatch that leads to sinusoidal injury, endotelial dysfunction, and impaired liver regeneration, leading to a postoperative liver failure[19,50]. The use of CFD could predict postoperative excessive portal inflow and design technical strategies, such as splenic artery ligation, to decrease portal inflow or optimize the future liver remnant prior to surgery.

• Predict “splenic artery steal syndrome” after liver transplantation: The disappearance of portal hypertension after liver transplant implies a temporal increase in portal inflow. Due to the HABR effect, arterial inflow decreases due to excessive portal inflow; this insufficient arterial inflow can lead to graft dysfunction, biliary ischemia, and impaired graft regeneration[15]. Preoperative prediction could help intraoperative decisions, such as whether to ligate the splenic artery or implement other mitigation strategies.

• Avoid liver arterial insufficiency after pancreatic surgery: Up to 10% of patients undergoing PD show a CT stenosis, and in these patients, GDA ligation can lead to increased major complications, including biliary and liver ischaemia[5-7]. The use of CFD could predict this postoperative complication, allowing the use of preoperative or intraoperative mitigation strategies, such as celiac trunk stenting or arcuate ligament section. It could also help avoid performing surgery in high-risk cases[19].

The use of these technologies could also help to understand why postoperative complications arise from undiagnosed altered blood flow behavior, such as portal hypertension due to altered suprahepatic drainage, or venous thrombosis due to kinking of the anastomosis. In addition, knowing the distribution of vascular flow will allow improvement in the application of intravascular treatments.

Moreover, these patient-specific simulations could be integrated into surgical planning systems, allowing surgeons to anticipate critical hemodynamic changes based on different surgical scenarios. Such predictive modeling may serve as a valuable decision-making aid, for example, in determining the optimal extent of liver resection or in evaluating the need for vascular reconstruction. Furthermore, as real-time imaging and computational power continue to evolve, the convergence of 4D-flow MRI and CFD could also support intraoperative guidance systems, offering dynamic feedback based on updated anatomical and flow data. In the long term, incorporating machine learning algorithms into this pipeline could enable semi-automated adaptation of CFD simulations to clinical imaging inputs, further facilitating personalized vascular management strategies in HPB surgery. To allow this technology to grow and be validated, multicentric studies including large amounts of data and patients are recommended.

The primary limitation of this manuscript is inherent to the methodology of narrative reviews, which do not provide evidence-based syntheses of specific research questions or definitive guideline statements. The interpretations offered are subjective and may vary depending on the reader’s perspective or the context of the review. Additionally, several other limitations should be acknowledged. Neither 4D-flow MRI nor CFD is currently part of routine clinical practice in HPB surgery. Most of the available evidence derives from pilot studies or research-oriented workflows. Therefore, many of the comparative analyses presented remain largely theoretical. Furthermore, heterogeneity in imaging protocols, modeling assumptions, and outcome metrics limits direct comparison and highlights the need for prospective, standardized clinical validation.

In conclusion, both 4D-flow MRI and CFD are promising technological tools likely to enhance patient evaluation and preoperative planning in the HPB field. However, further research is needed to fully assess the utility of CFD and its associated costs.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, literature search and screening, writing - review and editing, supervision: Ausania F

Methodology, literature search and screening, data extraction, writing - original draft: González-Abós C

Methodology, resources: Molina R, Almirante S

Methodology, data synthesis, validation: Vázquez M

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this systematic review are included in this published article. Additional data (e.g., full extraction tables or search strategies) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Ausania F is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Artificial Intelligence Surgery. Ausania F was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

2. Mogal H, Vermilion SA, Dodson R, et al. Modified frailty index predicts morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1714-21.

3. Mueller M, Breuer E, Mizuno T, et al. Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma - novel benchmark values for surgical and oncological outcomes from 24 expert centers. Ann Surg. 2021;274:780-8.

4. Shaib WL, Zakka K, Hoodbhoy FN, et al. In-hospital 30-day mortality for older patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11:660-7.

5. Coco D, Leanza S. Celiac trunk and hepatic artery variants in pancreatic and liver resection anatomy and implications in surgical practice. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:2563-8.

6. Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, Peros G. Celiac artery stenosis: an underappreciated and unpleasant surprise in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:349-56.

7. Dembinski J, Robert B, Sevestre MA, et al. Celiac axis stenosis and digestive disease: diagnosis, consequences and management. J Visc Surg. 2021;158:133-44.

8. Berry C, Kelly J, Cobbe SM, Eteiba H. Comparison of femoral bleeding complications after coronary angiography versus percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:361-3.

9. Gargiulo G, Giacoppo D, Jolly SS, et al.; Radial Trialists’ Collaboration. Effects on mortality and major bleeding of radial versus femoral artery access for coronary angiography or percutaneous coronary intervention: meta-analysis of individual patient data from 7 multicenter randomized clinical trials. Circulation. 2022;146:1329-43.

10. Kamada H, Nakamura M, Ota H, Higuchi S, Takase K. Blood flow analysis with computational fluid dynamics and 4D-flow MRI for vascular diseases. J Cardiol. 2022;80:386-96.

12. Malinowski D, Fournier Y, Horbach A, et al. Computational fluid dynamics analysis of endoluminal aortic perfusion. Perfusion. 2023;38:1222-9.

13. Faizal WM, Ghazali NNN, Khor CY, et al. Computational fluid dynamics modelling of human upper airway: a review. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;196:105627.

14. Kauffmann EF, Napoli N, Menonna F, et al. Robotic pancreatoduodenectomy with vascular resection. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401:1111-22.

15. Aoki T, Imamura H, Kaneko J, et al. Intraoperative direct measurement of hepatic arterial buffer response in patients with or without cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:684-91.

16. Sakamoto K, Iwamoto Y, Ogawa K, et al. Impact of reconstructed portal vein morphology on postoperative nutritional status in pancreatoduodenectomy: a computational fluid dynamics study. Surg Today. 2025;55:445-51.

17. Sakamoto K, Iwamoto Y, Ogawa K, et al. Unification venoplasty during two versus one venous reconstruction: computational fluid dynamics study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023;30:e31-5.

18. Song H, Li X, Huang H, Xie C, Qu W. Postoperative virtual pressure difference as a new index for the risk assessment of liver resection from biomechanical analysis. Comput Biol Med. 2023;157:106725.

19. González-Abós C, Molina R, Almirante S, Vázquez M, Ausania F. Computational fluid dynamics for vascular assessment in hepatobiliopancreatic surgery: a pilot study and future perspectives. Surg Endosc. 2025;39:3127-36.

20. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

21. Sakamoto K, Iwamoto Y, Ogawa K, et al. Impact of the inferior vena cava morphology on fluid dynamics of the hepatic veins. Surg Today. 2024;54:205-9.

22. Ito T, Ogiso S, Nakamura M, et al. Fluid analysis unveils hepatic venous outflow obstruction and its negative impact on posttransplant graft regeneration. Liver Transpl. 2023;29:658-62.

23. Riedel C, Hoffmann M, Ismahil M, et al. Four-dimensional flow MRI-based computational fluid dynamics simulation for noninvasive portosystemic pressure gradient assessment in patients with cirrhosis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Radiology. 2024;313:e232989.

24. Zheng Y, Hu Q, Zhou J, et al. Evaluation of the presence and severity of spontaneous splenorenal or gastrorenal shunts via four-dimensional flow magnetic resonance imaging: a preliminary study. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2024;14:7625-39.

25. Karam R, Elged BA, Elmetwally O, El-Etreby S, Elmansy M, Elhawary M. Porto-mesenteric four-dimensional flow MRI: a novel non-invasive technique for assessment of gastro-oesophageal varices. Insights Imaging. 2024;15:231.

26. Stankovic Z, Rössle M, Euringer W, et al. Effect of TIPS placement on portal and splanchnic arterial blood flow in 4-dimensional flow MRI. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:2634-40.

27. Bannas P, Roldán-Alzate A, Johnson KM, et al. Longitudinal monitoring of hepatic blood flow before and after tips by using 4D-flow MR imaging. Radiology. 2016;281:574-82.

28. Owen JW, Saad NE, Foster G, Fowler KJ. The feasibility of using volumetric phase-contrast MR imaging (4D flow) to assess for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt dysfunction. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29:1717-24.

29. Cox EF, Palaniyappan N, Aithal GP, Guha IN, Francis ST. Using MRI to study the alterations in liver blood flow, perfusion, and oxygenation in response to physiological stress challenges: meal, hyperoxia, and hypercapnia. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:1577-86.

30. Sugiyama M, Takehara Y, Kawate M, et al. Optimal plane selection for measuring post-prandial blood flow increase within the superior mesenteric artery: analysis using 4D flow and computational fluid dynamics. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2020;19:366-74.

31. Taebi A, Pillai RM, Roudsari BS, Vu CT, Roncali E. Computational modeling of the liver arterial blood flow for microsphere therapy: effect of boundary conditions. Bioengineering. 2020;7:64.

32. Du J, Shi J, Liu J, Deng C, Shen J, Wang Q. Hemodynamic analysis of hepatic arteries for the early evaluation of hepatic fibrosis in biliary atresia. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2021;211:106400.

33. Aramburu J, Antón R, Rodríguez-Fraile M, Sangro B, Bilbao JI. Computational fluid dynamics modeling of liver radioembolization: a review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022;45:12-20.

34. Bane O, Stocker D, Kennedy P, et al. 4D flow MRI in abdominal vessels: prospective comparison of k-t accelerated free breathing acquisition to standard respiratory navigator gated acquisition. Sci Rep. 2022;12:19886.

35. Xie C, Sun S, Huang H, Li X, Qu W, Song H. A hemodynamic study of the relationship between the left and right liver volumes and the blood flow distribution in portal vein branches. Med Phys. 2024;51:6501-12.

36. Hyodo R, Takehara Y, Mizuno T, et al. Four-dimensional flow MRI assessment of portal hemodynamics and hepatic regeneration after portal vein embolization. Radiology. 2023;308:e230709.

37. Moon CM, Kim SK, Heo SH, Shin SS. Hemodynamic changes in the portal vein with age: evaluation using four-dimensional flow MRI. Sci Rep. 2023;13:7397.

38. Santiago A, Aguado-Sierra J, Zavala-Aké M, et al. Fully coupled fluid-electro-mechanical model of the human heart for supercomputers. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2018;34:e3140.

39. Aziz MU, Eisenbrey JR, Deganello A, et al. Microvascular flow imaging: a state-of-the-art review of clinical use and promise. Radiology. 2022;305:250-64.

40. Palaniyappan N, Cox E, Bradley C, et al. Non-invasive assessment of portal hypertension using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. J Hepatol. 2016;65:1131-9.

41. Morris PD, Narracott A, von Tengg-Kobligk H, et al. Computational fluid dynamics modelling in cardiovascular medicine. Heart. 2016;102:18-28.

42. Lee Y, Yoon S, Park SH, Nickel MD. Advanced abdominal MRI techniques and problem-solving strategies. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2024;85:345-62.

43. Hoad CL, Palaniyappan N, Kaye P, et al. A study of T1 relaxation time as a measure of liver fibrosis and the influence of confounding histological factors. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:706-14.

44. Lipska L, Visokai V, Levy M, Koznar B, Zaruba P. Celiac axis stenosis and lethal liver ischemia after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1203-6.

45. Masuda Y, Yoshizawa K, Ohno Y, Mita A, Shimizu A, Soejima Y. Small-for-size syndrome in liver transplantation: Definition, pathophysiology and management. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2020;19:334-41.

46. Mourad MM, Liossis C, Gunson BK, et al. Etiology and management of hepatic artery thrombosis after adult liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:713-23.

47. Stewart ZA, Locke JE, Segev DL, et al. Increased risk of graft loss from hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation with older donors. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1688-95.

48. Lange C, Barthelmäs P, Rosnitschek T, Tremmel S, Rieg F. Impact of HPC and automated CFD simulation processes on virtual product development - a case study. Appl Sci. 2021;11:6552.

49. Ouro P, Lopez-novoa U, Guest MF. On the performance of a highly-scalable Computational Fluid Dynamics code on AMD, ARM and Intel processor-based HPC systems. Comput Phys Commun. 2021;269:108105.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].