AIONS Consensus Conference on Definitions of Artificial Intelligence Surgery, Surgomics and Robotics

Abstract

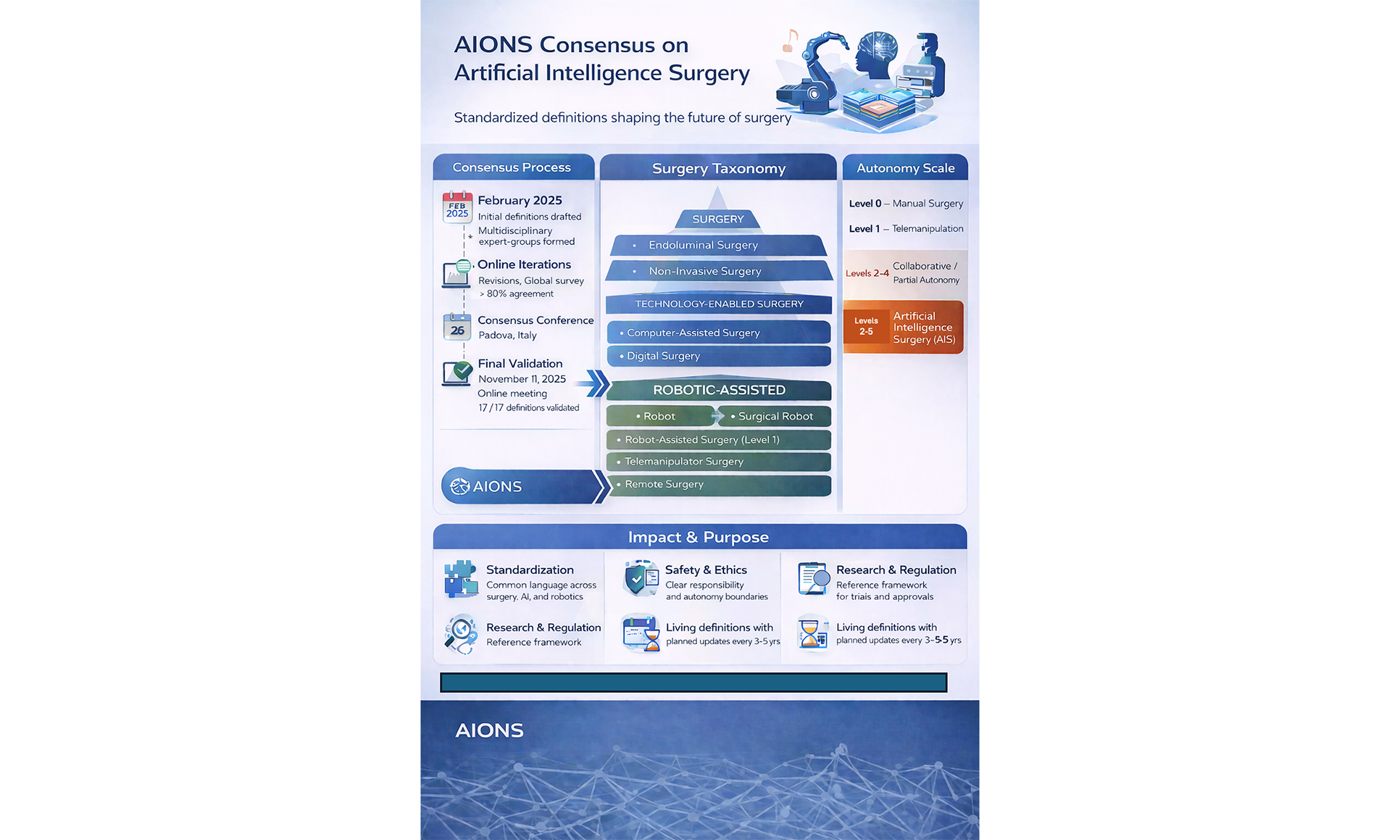

This Consensus Statement was jointly developed by the Editorial Board Members of Artificial Intelligence Surgery and the Artificial Intelligence Organization for the Next Generation of Surgeons (AIONS). The initiative began in February 2025 and proceeded through iterative drafting of definitions, online meetings, expert subgroup revisions, an online validation survey, an in-person Consensus Conference, and a final online meeting to confirm revisions and review the conference manuscript. Votes greater than or equal to 80 percent were considered validating. Definitions were sought for: (1) Surgery, (2) Endoluminal Surgery, (3) Percutaneous Surgery, (4) Robot, (5) Surgical Robot, (6) Robot-Assisted Surgery, (7) Telemanipulator Surgery, (8) Remote Surgery, (9) Collaborative Robotic (Cobotic) Surgery, (10) Robotic Surgery, (11) Artificial Intelligence Surgery, (12) Surgomics, (13) Surgical Multiomics, (14) Non-Invasive Surgery, (15) Digital Surgery, (16) Computer-Assisted Surgery, and (17) Cybersurgery. All candidate definitions achieved at least 80 percent approval in an online vote prior to the Consensus Conference. The in-person meeting occurred on 26 September 2025 at the Orto Botanico, University of Padova, Italy, where 11 definitions were ratified. The definition of Surgery was deemed premature and invalidated. Surgomics and Surgical Multiomics were determined to be distinct entities and were therefore revoted online after the meeting. Collaborative Robotics was clarified as requiring co-local presence of the surgeon and robot. Definitions for Percutaneous Surgery and Robot were amended and validated during a follow-up online vote on 11 November. Ultimately, all 17 definitions were validated. This Consensus provides terminology, rationale, and strategic direction for the surgical field as artificial intelligence, robotics, and data science reshape surgical practice. Future Consensus Conferences are planned to update definitions as the field evolves.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In the evolving landscape of surgical innovation, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and advanced data analytics is redefining the field. To maintain clarity and standardization in this rapidly changing environment, a unified set of definitions is essential. The Editorial Board Members of Artificial Intelligence Surgery (AIS) and Members of Artificial Intelligence Organization for the Next Generation of Surgeons (AIONS) have collaborated to produce consensus terminology for emerging surgical concepts[1,2].

The journal AIS was launched in 2021 and is the first peer-reviewed journal dedicated exclusively to AI and surgery, serving as the official publication of AIONS. As surgery is increasingly becoming less invasive, the term surgery is used to include any interventional procedure in healthcare, such as interventional endoscopy and radiology.

AIONS was founded in 2025 as a non-profit society focused on advancing AI-related efforts in surgery. The name is derived from the Greek word for eternity, symbolizing the enduring influence of technology on surgical practice. AIONS was inspired by the Editorial Board of AIS, but with the further aim of connecting surgeons, medical doctors, computer scientists, engineers, ethicists, and other stakeholders in collaborative innovation.

Strategic priorities include: (1) establishing governance and operational structures; (2) hosting annual global conferences; (3) publishing consensus guidelines; and (4) building collaborative research and educational initiatives among medical and non-medical entities. AIONS also aims to address the closed nature of some AI research environments by creating open opportunities for participation in surveys, research projects, webinars, and collaborative publications.

This effort began in February 2024 when members of the AIONS/AIS Task Force on Definitions of Artificial Intelligence Surgery devised preliminary definitions to act as a starting point. This was followed by an online meeting, where team leaders and members were designated, and topic-specific working groups independently modified the preliminary definitions. These were refined through a series of independent online discussions and then consolidated as a group. A global online survey was conducted to gather expert input from surgeons, engineers, computer scientists, and other stakeholders and to assess consensus agreement. The process culminated in the September 2025 consensus meeting in Padova, where definitions were ratified if they were unedited and had obtained the appropriate threshold during the pre-congress voting phase (survey). If problems with the definitions were identified, these issues were resolved and then validated at a final post-conference validation meeting.

The consensus work aligns with the mission of AIONS to democratize AI research in surgery and ensure globally relevant, ethically grounded innovation.

METHODS

Initially, definitions were sought for (1) Surgery, (2) Endoluminal Surgery, (3) Percutaneous Surgery, (4) Robot, (5) Surgical Robot, (6) Robot-Assisted Surgery, (7) Telemanipulator Surgery, (8) Remote Surgery, (9) Collaborative Robotic (Cobotic) Surgery, (10) Robotic Surgery, (11) Artificial Intelligence Surgery, (12) Surgical Multiomics/Surgomics, (13) Non-Invasive Surgery, (14) Digital Surgery, (15) Computer-assisted Surgery and (16) Cybersurgery. Preliminary definitions were formulated by the first two authors and were created to stimulate discussion and act as a springboard for further refinement.

The consensus process followed a structured, multi-stage Delphi-style methodology designed to promote refinements through iterative feedback. The process consisted of: (1) drafting of initial definitions based on literature, clinical expertise, and previous consensus publications; (2) formation of multidisciplinary working groups, each led by designated term leaders responsible for coordinating revisions and incorporating external feedback (in instances of non-responsiveness, duties were assumed by the first author to avoid delays); (3) iterative revisions during multiple online meetings, both plenary and subgroup, conducted between February 2024 and July 2025; (4) dissemination of a structured online survey to evaluate updated definitions; (5) quantitative (percentage agreement) and qualitative (written comments) review of survey results; (6) an in-person Consensus Conference held on September 26, 2025 at the Orto Botanico of the University of Padova (Padova, Italy) to discuss discrepancies, finalize language, and vote on ratification; and (7) a final online meeting to review and ratify modifications introduced during the in-person conference.

A consensus threshold of ≥ 80% agreement was required for ratification. During the in-person conference, definitions could be withheld from ratification despite ≥ 80% agreement if concerns arose during discussion. All rationales for modifications were documented for transparency and future reference. Definitions that did not achieve ratification proceeded to a second online survey, followed by an online validation meeting to finalize the vote.

RESULTS: FINAL CONSENSUS DEFINITIONS

All sixteen definitions received an online approval rate of 80% or higher before the consensus meeting [Table 1]. The final in-person session took place on September 26, 2025, at the Orto Botanico, University of Padova, Italy, where eleven consensus definitions were formally ratified. The proposed definition of Surgery was considered too forward-looking and was invalidated pending further discussion. It was also agreed that Surgical Multiomics and Surgomics represent two distinct concepts; therefore, voting for them simultaneously invalidated the initial result[3]. During the meeting, it was clarified that Collaborative Robotics refers to situations where the surgeon and robot work together locally, rather than remotely, and does not necessarily imply autonomous action by either party. The definitions for Percutaneous Surgery and Robot were slightly revised during the Padova discussions. Consequently, an additional online validation meeting was held on November 11. In total, sixteen of seventeen definitions were validated, with only the new definition of Surgery failing to reach consensus [Table 1].

Summary of consensus outcomes for definitions related to surgical, robotic, and digital surgery terminology

| Definitions | Votes: agree | Votes: disagree or unsure | Final survey score % (disagree, unsure/agree) | Ratified during in-person consensus (Y/N) | Reason | Post conference vote % agreement (disagree, unsure/agree) | Validated during the final online meeting |

| Surgery | 24 | 6 | 80 (6/24) | No | Definition too forward-thinking | 91.1 (4/45) | Yes |

| Endoluminal surgery | 25 | 5 | 83 (5/25) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Percutaneous surgery | 24 | 6 | 80 (6/24) | No | Emphasize access via a skin puncture | 95.6 (2/45) | Yes |

| Robot | 28 | 2 | 93 (2/28) | No | A degree of autonomy needed | 95.6 (2/45) | Yes |

| Surgical robot | 28 | 2 | 93(2/28) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Robot-assisted surgery | 28 | 2 | 93 (2/28) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Telemanipulator surgery | 30 | 0 | 100 (0/30) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Remote surgery | 29 | 1 | 97 (1/29) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Collaborative robotic (robotic) surgery | 28 | 2 | 93 (2/28) | No | Fundamental flaw with final definition | 91.1 (4/45) | Yes |

| Robotic surgery | 25 | 5 | 83 (5/25) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Artificial intelligence surgery | 29 | 1 | 97 (1/97) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Surgical multiomics/surgomics | 25 | 5 | 83 (5/25) | No | Definition divided into 2 separate definitions | Surgical Multiomics 95.6 (2/45), Surgomics 88.9 (5/45) | Yes |

| Non-invasive surgery | 27 | 3 | 90 (3/27) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Digital surgery | 29 | 1 | 97 (1/29) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Computer-assisted surgery | 27 | 3 | 90 (3/27) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

| Cybersurgery | 27 | 4 | 87 (4/27) | Yes | Initial ≥ 80%, no changes | NA | NA |

Surgery

1A - Surgery is a medical procedure done with the hands involving the intentional and consented therapeutic manipulation of organs, tissues, cells with the aim of restoring, improving, or preserving the physiological function of the organism.

1B -It employs various forms of energy-mechanical, thermal, electrical, optical, or biological-delivered through different modalities and instruments.

1C - Surgical interventions are guided by imaging and navigation systems, and increasingly supported or powered by advanced cognitive technologies, including AI and mechatronic systems, to enhance precision, safety, and patient outcomes.

Although the initial vote at the Padova conference was 80%, the definition was refined after further discussion and obtained over 90% approval at the online Validation meeting [Table 1].

Endoluminal surgery

Endoluminal surgery refers to surgical procedures performed entirely from within the lumen of a hollow organ, typically accessed through natural orifices without external incisions. The term encompasses a spectrum of minimally invasive interventions, including interventional endoscopy techniques - such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), endoscopic gastrojejunostomy, and endoscopic bilio-enteric stenting - as well as Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES). These approaches emphasize the surgical nature of endoluminal access while offering significant benefits, including reduced tissue trauma, faster recovery, and minimized postoperative discomfort, thereby positioning endoluminal surgery as a key component of modern minimally invasive surgical practice[4-6].

The definition obtained 83% initial agreement and underwent no revisions at the Consensus Conference so it was ratified.

Percutaneous surgery

Percutaneous surgery is a surgical approach in which instruments, catheters, or guidewires are introduced into the body through a small skin puncture, without creating large incisions. These procedures are often guided by imaging modalities such as fluoroscopy, ultrasound, or CT, enabling precise navigation to the target site. Percutaneous techniques encompass a range of interventions - from vascular access and angioplasty to minimally invasive treatments of internal organs[7].

The consensus group reached over 95% agreement on this updated definition during the online validation meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

Robot

A robot is a complex, actuated mechanism - integrating mechanical, electronic, and computational components - programmable along one or more controlled axes and capable of exhibiting a degree of autonomy, such as perceiving its environment, processing information, and performing purposeful actions in the physical world. This adaptation maintains consistency with the spirit of International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 8373:2012 while reflecting the unique design constraints and functional autonomy found in contemporary medical robotic systems.

The consensus group reached over 95% agreement on this updated definition during the online validation meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus.

Surgical robot

A surgical robot is an advanced mechatronic–informatics (cyber-physical) system consisting of robotic arms, surgical end-effectors, a sensor array, and a control system that includes both software components and physical elements, such as a surgeon’s console with an operator interface (in the case of teleoperation). It can operate under local or remote control at various levels of autonomy - ranging from a telemanipulator fully controlled by the operator to partially or fully autonomous modes - utilizing AI, real-time image analysis, and preoperative planning to enhance precision, safety, and the overall standard of surgical procedures. Beyond replicating human actions, it can extend surgical capabilities beyond human physical or cognitive limits.

The definition obtained 93% initial agreement and underwent no revisions at the Padova meeting, so it was ratified.

Robot-assisted surgery

Robot-assisted surgery (RAS) refers to surgical procedures performed using a robotic system in which the surgeon maintains direct control over the execution of tasks - either locally or remotely - typically corresponding to Level 1 surgical autonomy (telemanipulation)[8]. The term “robot-assisted” has been historically and widely used to describe systems that, at this level, function primarily as advanced mechatronic tools. In practice, RAS is sometimes applied to systems with partial autonomy (Levels 2-4), where collaborative or “cobotic” modes of operation allow the robot to perform certain functions independently under the surgeon’s supervision. RAS should not be used to describe fully autonomous systems (Level 5), where the robot operates without direct human control.

The consensus group reached 93% agreement on this definition during the Padova meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

Telemanipulator surgery

Telemanipulator surgery is a type of procedure in which the surgeon operates on a patient using robotic instruments controlled from a separate console. Instead of directly handling the tools, the surgeon sits at a workstation, viewing the surgical field through high-definition 3D cameras. Their hand and finger movements are translated into precise, scaled motions of articulated instruments inside the patient’s body. This technique allows for enhanced precision, dexterity, and visualization, particularly in complex minimally invasive procedures. It conforms to level 1 surgical autonomy (e.g., telemanipulation), where all actions are performed directly under the surgeon’s control.

The consensus group reached 100% agreement on this definition during the Padova meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

Remote surgery

Remote surgery (Telesurgery) is a form of telemanipulator surgery (Level 1 surgical autonomy) in which the operating surgeon is physically located far from the patient. The term “tele-” derives from the Greek tēle (τῆλε), meaning “far” or “distant”. The procedure is performed through a surgical robot, which includes a console for the surgeon and an operative unit at the patient’s location. The surgeon controls the robot via the console, receiving real-time high-definition visual feedback and, in some systems, tactile sensations, enabling precise manipulation of surgical instruments inside the patient’s body. The system relies on very high-speed, low-latency, stable, and secure communication networks to ensure safe operation. This approach enables expert surgeons to perform complex procedures or mentor local teams in distant locations, thereby extending access to specialized surgical care across geographical boundaries.

The consensus group reached over 97% agreement on this definition during the Padova meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

Collaborative (cobotic) surgery

1A - Collaborative (cobotic) surgery refers to surgical procedures performed through active local collaboration between a surgeon and a robotic system operating with partial autonomy, typically corresponding to Levels 2-4 on the surgical autonomy scale.

1B - Unlike telemanipulator and remote surgery, cobotic surgery implies that the surgeon and robot are working together locally at the operating room table in contact with the patient.

1C - In cobotic surgery, decision-making and task execution are shared: the robot, equipped with perceptual, cognitive, and motor capabilities-often supported by AI and real-time data analysis-assists, guides, or performs specific elements of the procedure within autonomy limits defined by the surgeon. This approach combines the precision and consistency of robotic systems with the adaptability and expertise of human decision-making.

During the Padova meeting, the consensus group reached 93% agreement on the definition; however, concerns were raised, and it was subsequently modified and voted on during the online Validation meeting, where it obtained over 91% agreement.

Robotic surgery

Robotic surgery refers to surgical procedures in which the robotic system operates with some degree of autonomy beyond direct, moment-to-moment control by the surgeon. This definition typically corresponds to Levels 2-5 on the surgical autonomy scale, encompassing partial autonomy, collaborative modes, and full autonomy.

The consensus group reached 83% agreement on this definition during the Padova meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

Artificial intelligence surgery

Artificial intelligence surgery (AIS) refers to the integration of AI-driven technologies - such as computer vision, advanced robotics, agent-based systems, and generative models - into surgical workflows to enable Levels 2-5 surgical autonomy. AIS applies data-driven, autonomous, and semiautonomous methods across the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases to enhance precision, improve patient outcomes, and increase procedural efficiency. By augmenting the surgeon’s perceptual, cognitive, and decision-making capabilities, AIS extends human expertise while maintaining strict ethical, regulatory, and patient safety standards.

The consensus group reached 97% agreement on this definition during the Padova meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

Surgomics

Leverages a mode of comprehensive intraoperative data to generate disease- or treatment-specific predictions. This encompasses the integrated AI analysis of diverse data modalities, including visual (e.g., surgical video, imaging), audio (e.g., vocal cues, instrument sounds), physiological vital signs, textual information (e.g., surgical notes, real-time annotations), and others.

Although agreement exceeded 80%, the definitions of Surgomics and Surgical Multiomics were voted on together. Consequently, a formal vote was held during the online Validation meeting, where over 95% agreement was obtained for Surgical Multiomics and over 88% for Surgomics, leading to the ratification of both statements.

Surgical multiomics

Surgical multiomics: The integrated analysis of surgomics with a broad range of high-dimensional biological and clinical data from pre-, intra-, and post-operative phases to generate personalized predictions for surgical management and patient care.

See above.

Non-invasive surgery

Non-invasive surgery (also known as Transcutaneous Surgery) refers to a therapeutic technique in which high-energy beams - such as focused ultrasound, high-intensity light, or ionizing radiation - are delivered externally to precisely target tumors or other pathological lesions located deep within the body, without making skin incisions or inserting any instruments through the body wall[9,10]. Unlike percutaneous or laparoscopic interventions, non-invasive surgery involves no physical penetration of the skin or introduction of tools such as needles or catheters. While surrounding healthy tissues may still be exposed to collateral energy effects (e.g., thermal injury, burns), this approach is distinguished by the absence of any direct mechanical access to the target area. Conventional radiotherapy, even with focused beams, is generally not classified as non-invasive surgery, as it often results in broader exposure of superficial tissues to ionizing radiation and its associated complications.

During the Padova meeting, the definition was ratified after achieving 90% consensus.

Digital surgery

Digital surgery is a multidisciplinary field centered on the acquisition, processing, integration, and application of digital data throughout the entire surgical pathway. It combines advanced technologies - such as AI, computer vision, augmented and virtual reality, robotics, connected surgical devices, and interoperable data platforms - to transform surgical care into a fully data-driven process. The core objectives are to enhance evidence-based clinical decision-making, streamline perioperative workflows, personalize patient care, ensure end-to-end procedural traceability, and enable continuous performance auditing. By leveraging real-time digital information and predictive analytics, digital surgery improves precision, safety, and efficiency while fostering continuous learning and quality improvement.

The consensus group reached 97% agreement on this definition during the Padova meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

Computer-assisted surgery

Computer-assisted surgery (CAS) refers to the use of computerized systems and digital technologies to support the entire surgical process, including preoperative planning, intraoperative navigation, and postoperative assessment. CAS systems integrate advanced diagnostic imaging, patient- specific anatomical modeling, and computational analysis to generate precise surgical plans. These plans are then executed with the assistance of intraoperative guidance systems-often incorporating real-time imaging, tracking sensors, and robotic interfaces-to enhance surgical accuracy, minimize invasiveness, and improve patient outcomes.

The consensus group reached 90% agreement on this update during the Padova meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

Cybersurgery

Cybersurgery refers to surgical practices that employ telecommunications, remote robotic systems, advanced simulation, and immersive digital platforms to perform procedures at a distance, enable real-time telementoring, and broaden global access to specialized surgical expertise. The prefix “cyber”, derived from the Greek kybernētēs (κυβερνήτης), meaning “helmsman” or “steersman”, underscores the role of the operator - or intelligent control system - in directing and managing the surgical process across physical and geographical boundaries.

The consensus group reached 90% agreement on this update during the Padova meeting, confirming its acceptance for inclusion in this consensus statement.

DISCUSSION

Surgery

Although the initial vote yielded 80% agreement, the definition was deemed too forward-thinking BY SOME and not reflective of surgery as it is currently practiced. It was determined that surgery should be clarified as an intentional, planned, and consented therapeutic act performed under clinical accountability, and that it must be distinguished from accidental injury management and non-interventional therapies. Furthermore, genes are not part of today’s core scope and should be regarded as a future horizon. Current surgical practice manipulates organs and tissues; gene editing is not routinely performed within surgery today. As a result, the agreed-upon definition OF SURGERY should PROBABLY be reserved for the future of surgery rather than current practice.

Additionally, there was discussion of the need to anchor the definition in the etymology of the word surgery, specifically, “work with the hands”. Reference should be maintained to the Greek roots (cheir = hand, ergon = work) to emphasize the operative, manual origin of surgery[11]. Just as surgeons hold instruments in their hands, surgeons holding robotic devices locally or remotely are still performing interventions with their hands.

The working group reviewed the initial definition of Surgery considering technological advances, evolving clinical practices, and the integration of AI and digital systems into surgery. The updated definition was crafted to increase precision, incorporate contemporary terminology, and reflect interdisciplinary consensus. Key drivers included feedback from the global survey, which highlighted ambiguities in the initial phrasing, and a desire to ensure that the definition remains relevant across different surgical specialties and international contexts.

From a clinical perspective, the final definition better defines the “Future of Surgery”, and captures the shift toward data-driven decision-making, robotic assistance, and minimally invasive techniques, as well as acknowledging imaging and computational guidance systems. Ethically, the definition seeks to balance innovation with patient safety, ensuring that terminology promotes transparency and informed consent. The changes also align with published literature in AIS and related journals, supporting standardized nomenclature for regulatory and educational use.

Endoluminal surgery

The working group reviewed the initial definition of Endoluminal Surgery considering technological advances, evolving clinical practices, and the integration of AI and digital systems into surgery[4-6]. The updated definition was crafted to increase precision, incorporate contemporary terminology, and reflect interdisciplinary consensus. Key drivers included feedback from the global survey, which highlighted ambiguities in the initial phrasing, and a desire to ensure that the definition remains relevant across different surgical specialties and international contexts.

Percutaneous surgery

During the Padova meeting, the phrase, “-and combine the benefits of reduced tissue trauma, shorter recovery times, and lower complication rates compared to traditional open surgery”, at the end of the definition was removed, as it was considered to describe the benefits rather than the definition itself[7].

Robot

Several key distinctions must be highlighted when defining a robot. Robots possess at least some level of autonomy, allowing them to sense, process, and act without continuous, moment-to-moment human control. Mechatronic systems (e.g., remote-controlled devices) integrate mechanics, electronics, and control software, but operate entirely based on direct human commands or preset algorithms without adaptive interaction with their environment[12].

The minimum criteria for a device to qualify as a robot (without direct and continuous human control) include: perception, processing and action. Perception is the ability to sense its environment (e.g., via cameras, proximity sensors, gyroscopes). Processing is the ability to analyze input and make decisions (e.g., control algorithms, AI logic). Action means the ability to execute physical tasks independently (e.g., navigate, manipulate objects, adjust to changing conditions).

During the Padova meeting, the phrase “…which describes a robot as an actuated mechanism programmable in two or more axes with a degree of autonomy, moving within its environment, to perform intended tasks”, at the end of the definition was noted to have several limitations in medical robotics. The requirement of “two or more programmable axes” specified in ISO 8373:2012, Robots and Robotic Devices: Terms and Definitions, is a technical criterion originally developed for industrial robotics, where systems typically operate in multi-degree-of-freedom environments. In contrast, medical robots frequently function on a different physical scale and within distinct architectures of motion, making this criterion less universally applicable.

According to ISO 8373:2012, a robot is defined as: “an actuated mechanism programmable in two or more axes with a degree of autonomy…”. This definition was intended to distinguish industrial robots from simpler automated manipulators, such as single-direction handling devices or automatic feeders, which lack programmable multi-axis motion and do not exhibit autonomous behavior. In medicine, however, several robotic systems are single-axis or quasi-single-axis by design. This includes devices used in endovascular, cardiac, neurosurgical, and ophthalmic applications[12].

These systems are capable of highly precise translational or rotational motion, controlled by computer algorithms and frequently equipped with feedback sensors. Some even incorporate elements of autonomy, such as position control guided by real-time imaging or predefined safety constraints[13]. Representative examples include: (1) robot-assisted catheter navigation systems [e.g., CorPath GRX robotic system (Corindus/Siemens Healthineers), Sensei X]; (2) robotic platforms for microsurgery in ophthalmology or neurosurgery; (3) certain advanced endoscopic robot systems[5,11,14,15]. Although such systems may formally possess only 1 programmable axis, they meet most of the functional and structural criteria associated with robotic systems[1]. Given these characteristics, the rigid “two-axis” requirement of ISO 8373:2012 should be interpreted functionally rather than literally in the medical domain. Hence, our definition for “robot” is more inclusive and context-appropriate.

Surgical robot

A surgical robot is a system that encompasses a spectrum of technologies, ranging from remote- or locally controlled robotic arms operating entirely under human supervision to semiautonomous and fully autonomous platforms capable of performing surgical procedures with varying degrees of independence. By definition, this includes surgical autonomy levels 1-5[8,15].

Robot-assisted surgery

Currently, RAS should refer to robotic systems that use telemanipulation/remote control. However, with the advent of increasing surgical autonomy, RAS may eventually be used to refer to robots that provide surgical autonomy levels 2-4[8]. Regardless, if a system obtains full surgical autonomy, it should be referred to as Robotic Surgery. Because of this, it is paramount that researchers and clinicians stop using the term robotic surgery, when they are, in fact, performing or referring to RAS[16].

Telemanipulator surgery

This term should be applied to any surgery in which the surgeon is not in direct contact with the patient and is, by definition, DISTANT from the patient - that is, not local to or nearby the patient[17].

Remote surgery

Remote surgery is a form of telemanipulator surgery where the surgeon cannot be considered able to aid the patient aside from via remote control of robotic arms. This is distinguished from telemanipulator surgery, where the operating surgeon can and is expected to be able to convert to laparoscopy or an open approach in a matter of seconds to minutes[17,18].

Collaborative robotic (robotic) surgery

Initial definitions did not emphasize the fundamental point that cobotic surgical systems require the cobot and surgeon to remain in contact with the patient, as opposed to being remote from the patient. Concerns were also raised regarding potential medico-legal implications of the initial definition concerning the collaborative nature of both the surgeon and robot. Additional discussion addressed whether the term “supervisory control” should be retained while omitting “ultimate responsibility”. The group ultimately agreed to emphasize shared control, partial autonomy, and integrated safety mechanisms, while deliberately avoiding legal or liability-related attributions. Similar to telemanipulator surgery, cobotic surgery can have autonomy levels 2-4; however, because it does not involve remote control, it cannot, by definition, be considered level 1 surgical autonomy[19].

Future studies will evaluate the concept of cobotic-assisted surgery, where the surgeon operates locally at the bedside, but controls the robot via tele-manipulation (e.g., foot pedal or voice control).

Robotic surgery

The term “robot” originates from the Czech word robota, meaning “servant” or more precisely “slave”. Without including the word “assisted”, the phrase “robotic surgery” suggests that the robot performs the entire operation autonomously[1]. Considerable confusion has arisen in the literature because many authors use the terms “robot-assisted surgery” and “robotic surgery” interchangeably[20-22]. As AI and surgical autonomy continue to advance, it is increasingly important for clinicians and researchers to specify the exact nature of each procedure.

Artificial intelligence surgery

AIS integrates features from surgical autonomy levels 2 through 5 with elements of CAS and digital surgery[1,23]. It is a broad, evolving concept that encompasses collaborative, robotic-assisted, and fully robotic surgery[24]. AIS also incorporates advanced imaging technologies such as augmented reality (AR), hyperspectral imaging, mixed reality, real-time decision support, and surgomics[25].

Surgomics

During the consensus process, it was recognized that the concepts of Surgical Multiomics and Surgomics, while closely related, represent distinct areas of study[26-28]. In the initial vote, these two terms had been evaluated together, creating ambiguity in their interpretation. Because the definitions had been considered jointly in the earlier vote, the panel determined that a formal re-vote was necessary. During the validation meeting, both definitions were reviewed independently, and the participants agreed to ratify them as two separate but complementary concepts.

Surgical multiomics

The group agreed that Surgical multiomics should remain focused on the integration of biological and clinical data across the pre-, intra-, and post-operative phases[27,28]. Upon further discussion, it was decided that Surgomics should be limited to intraoperative data analysis and prediction.

Non-invasive surgery

Although there was discussion during the Padova meeting regarding renaming the construct to avoid the terms “non-invasive” and “transcutaneous”, it was noted that both can be misleading, as energy delivery through skin and tissue remains biologically invasive due to thermal, mechanical, or radiation effects, even without a physical breach[9,10]. Some participants preferred terminology emphasizing incisionless access - procedures performed without any skin or mucosal breach - and the use of image-guided, extracorporeal energy delivery, such as in “Incisionless Image-Guided Therapy”. Because > 80% consensus was achieved, the definition was ratified during the Padova meeting; however, it was decided to include this discussion in the manuscript for clarity and transparency.

Digital surgery

Digital surgery emphasizes data-centric transformation. It focuses on the acquisition, processing, and integration of digital information throughout the entire surgical pathway - from preoperative planning to postoperative analysis[29,30]. Its goal is to make surgery more data-driven by improving decision-making, efficiency, and traceability. Technologies such as AI, augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR), and robotics support this mission by collecting and applying data for workflow optimization and continuous quality improvement[11,27,31].

AIS, on the other hand, emphasizes autonomy and intelligent execution. It integrates higher levels of surgical automation (2-5) with computer-assisted and robotic systems. AIS uses advanced imaging, analytics, and real-time decision support to enable adaptive automation and enhance intraoperative performance. While digital surgery provides the data foundation, AIS represents the intelligent operative application of that data - bridging the gap between human control and surgical autonomy[15].

In short, digital surgery is the data foundation, while AIS represents the intelligent operative application of that data.

CAS

CAS is the foundation of modern surgical technology. It focuses on computerized guidance-using imaging, navigation, and modeling systems to enhance precision during surgery[23,26,32]. CAS supports surgeons through tools such as preoperative 3D planning and intraoperative tracking but leaves all decision-making and execution to the human operator[24,25,33-38].

Digital surgery expands beyond CAS by emphasizing data integration and analytics across the entire surgical pathway-preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative[39]. It creates a connected ecosystem where digital data are continuously collected, analyzed, and used to improve workflows, outcomes, and surgical training.

AIS builds on both CAS and digital surgery by adding intelligent automation and adaptive decision-making. It integrates AI, robotics, and real-time analytics to assist - or even partially perform - surgical tasks autonomously.

Cybersurgery

While CAS enhances precision through imaging and navigation, digital surgery integrates data and analytics across the surgical continuum, and AIS introduces intelligent autonomy, Cybersurgery emphasizes connectivity and distance. It employs telecommunications, remote robotic systems, and immersive digital platforms to perform or guide surgical procedures across physical and geographical boundaries[11,40].

The term “cyber” highlights the role of the surgeon - or an intelligent control system - in directing and managing the procedure remotely. Unlike AIS, which focuses on intelligent automation, Cybersurgery is defined by telepresence, real-time collaboration, and global access to expertise, enabling surgery to transcend location-based limitations[40].

In short, CAS assists, digital surgery informs, AIS performs and Cybersurgery connects. Future studies will include the development of a classification tree diagram based on this consensus to facilitate teaching, clinical guideline development, and citation in regulatory documents.

Immediate actions following this consensus conference include the dissemination of definitions through peer-reviewed publications, integration into surgical education and training programs, and presentation at international conferences. These efforts will be supported by validation through larger surgical societies. Additional initiatives involve the development of multilingual versions (e.g., Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, and Japanese) to ensure global accessibility, and the creation of online resources and glossaries hosted by AIONS.

CONCLUSION

The consensus definitions developed through this process provide a foundational vocabulary for the integration of AI, robotics, and data science into surgical care. Clear definitions help avoid ambiguity, promote interdisciplinary collaboration, and support the development of regulatory and educational frameworks.

Participants recognized that, as technology evolves, periodic review will be necessary. AIONS will also develop a monitoring process to identify when technological advancements require revisiting these definitions. AIONS intends to host follow-up consensus processes every three to five years to ensure continued relevance.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Pr. Brice Gayet for his work regarding the definition of collaborative robotics. AIONS/AIS Task Force on Definitions of Artificial Intelligence Surgery: Mohammad Abu Hilal, Fabio Ausania, Elisa Bannone, Elena Bignami, Elie Chouillard, Maria Conticchio, Roland Croner, Ibrahim Dagher, Francesca Dal Mas, Belinda De Simone, Michele Diana, Marcello Di Martino, Mathieu D’Hondt, Gianfranco Donatelli, Ahmed EL Minawi, Michael Friebe, Isabella Frigerio, Michel Gagner, Vonetta George, Suzanne Gisbertz, Francesco Giovinazzo, Luca Gordini, Mustansar Ghanzafar, Vincent Grasso, Andrew Gumbs, Takeaki Ishizawa, Konrad Karcz, Stephen Kavic, Zain Khalpey, Michael Kreisel, Luca Milone, Nouredin Messaoudi, Leila Mureebe, Zbigniew Nawrat, Derek O’Reilly, Mahir Ozmen, Peter Passias, Silvana Perretta, Niki Rashidian, Gianluca Rompianesi, Sharona Ross, Thomas Schnelldorfer, Vivian Strong, Gaya Spolverato, Amir Szold, Martin Teraa, Gratia Tsai, Jordi Vidal-Jove, Karol Rawicz-Prusyński, Brandon Valencia Coronel, Teodoros Veronesi, Taiga Wakabayashi, Heather Yeo.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and developed initial definitions, coordinated expert working groups, and led iterative consensus discussions: Gumbs A, Michele D, Grasso V, Dagher I, Croner R, Spolverato G, Frigerio I, Ishizawa T, Abu Hilal M

Performed data acquisition, as well as provided administrative, technical, and material support: Gumbs A, Bannone E, Dal Mas F, Freibe M, Giovinazzo F, Khalpey Z, Messaoudi N, Ozmen MM, Passias P, Szold A, Rashidian N, Ross S, Schnelldorfer T, Nawrat Z, Croner R, de Simone B, Ishizawa T, Milone L, Özmen MM, Spolverato G

Contributed to validation, review & editing: Gumbs A, Abu Hilal M, Bannone E, Dagher I, Grasso V, Spolverato G, Frigerio I, Croner R, Ishizawa T, Diana M

Availability of data and materials

All materials used in this consensus, including survey instruments and meeting notes, are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. No new empirical data were generated for this work.

AI and AI-assisted tools statement

The graphical abstract was created using ChatGPT (latest version).

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Gumbs A is CMO of ACCREA Medical Robotics and CEO of TAO Surgical. Milone L is CMO of TAO Surgical. Gumbs A is Editor-in-Chief of the journal Artificial Intelligence Surgery. Ishizawa T is Honorary Regional Editor of the journal. Spolverato G, Abu Hilal M, Frigerio I, Croner R, and Passias P are Associate Editors. Diana M, De Simone B, Friebe M, Grasso SV, Karcz K, Khalpey Z, Milone L, Ozmen MM, Ross S, Schnelldorfer T, Szold A, and Nawrat Z are Editorial Board Members. Rawicz-Prusyński K, Bannone E, Dal Mas F, and Messaoudi N are Junior Editorial Board Members. Gumbs A, Ishizawa T, Spolverato G, Abu Hilal M, Frigerio I, Croner R, Passias P, Diana M, De Simone B, Friebe M, Grasso SV, Karcz K, Khalpey Z, Milone L, Ozmen MM, Ross S, Schnelldorfer T, Szold A, Nawrat Z, Rawicz-Prusyński K, Bannone E, Dal Mas F, and Messaoudi N were not involved in any steps of editorial processing, including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, and decision making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Gumbs AA, Perretta S, d’Allemagne B, Chouillard E. What is artificial intelligence surgery? Art Int Surg. 2021;1:1-10.

2. Gumbs AA, Grasso SV, Chouillard E, et al. Announcement of Consensus Conference on Definitions of Artificial Intelligence for the Next Generation of Surgeons. Art Int Surg. 2025;5:65-72.

3. Gumbs AA, Croner R, Abu-Hilal M, et al. Surgomics and the Artificial intelligence, Radiomics, Genomics, Oncopathomics and Surgomics (AiRGOS) Project. Art Int Surg. 2023;3:180-5.

4. Halvax P, Diana M, Lègner A, et al. Endoluminal full-thickness suture repair of gastrotomy: a survival study. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3404-8.

5. Légner A, Diana M, Halvax P, et al. Endoluminal surgical triangulation 2.0: a new flexible surgical robot. Preliminary pre-clinical results with colonic submucosal dissection. Int J Med Robot. 2017;13:e1819.

6. Okamoto N, Al-Taher M, Mascagni P, et al. Robotic endoscopic cooperative surgery for colorectal tumors: a feasibility study (with video). Surg Endosc. 2022;36:826-32.

7. Diana M, Halvax P, Mertz D, et al. Improving echo-guided procedures using an ultrasound-CT image fusion system. Surg Innov. 2015;22:217-22.

8. Gumbs AA, Gayet B. Why artificial intelligence surgery (AIS) is better than current robotic-assisted surgery (RAS). Art Int Surg. 2022;2:207-13.

9. Wah TM, Pech M, Thormann M, et al. A multi-centre, single arm, non-randomized, prospective european trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the HistoSonics system in the treatment of primary and metastatic liver cancers (#HOPE4LIVER). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2023;46:259-67.

10. Mendiratta-Lala M, Wiggermann P, Pech M, et al. The #HOPE4LIVER single-arm pivotal trial for histotripsy of primary and metastatic liver tumors. Radiology. 2024;312:e233051.

13. Boini A, Acciuffi S, Croner R, et al. Scoping review: autonomous endoscopic navigation. Art Int Surg. 2023;3:233-48.

14. Halvax P, Diana M, Nagao Y, Marescaux J, Swanström L. Experimental evaluation of the optimal suture pattern with a flexible endoscopic suturing system. Surg Innov. 2017;24:201-4.

15. Gumbs AA, Alexander F, Karcz K, et al. White paper: definitions of artificial intelligence and autonomous actions in clinical surgery. Art Int Surg. 2022;2:93-100.

16. Sijberden JP, Hoogteijling TJ, Aghayan D, et al.; International consortium on Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery (I-MILS). Robotic versus laparoscopic liver resection in various settings: an international multicenter propensity score matched study of 10.075 patients. Ann Surg. 2024;280:108-17.

17. Collins JW, Ghazi A, Stoyanov D, et al. Utilising an accelerated Delphi process to develop guidance and protocols for telepresence applications in remote robotic surgery training. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2020;22:23-33.

18. Picozzi P, Nocco U, Puleo G, Labate C, Cimolin V. Telemedicine and robotic surgery: a narrative review to analyze advantages, limitations and future developments. Electronics. 2024;13:124.

19. Gumbs AA, Abu-Hilal M, Tsai T, Starker L, Chouillard E, Croner R. Keeping surgeons in the loop: are handheld robotics the best path towards more autonomous actions? (A comparison of complete vs. handheld robotic hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases). Art Int Surg. ;1:38-51.

20. Guadagni S, Furbetta N, Di Franco G, et al. Robotic-assisted surgery for colorectal liver metastasis: a single-centre experience. J Minim Access Surg. 2020;16:160-5.

21. de’Angelis N, Khan J, Marchegiani F, et al. Robotic surgery in emergency setting: 2021 WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg. 2022;17:4.

22. Liu R, Abu Hilal M, Wakabayashi G, et al. International Experts Consensus Guidelines on Robotic Liver Resection in 2023. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:4815-30.

23. Giménez M, Gallix B, Costamagna G, et al. Definitions of computer-assisted surgery and intervention, image-guided surgery and intervention, hybrid operating room, and guidance systems: Strasbourg International Consensus Study. Ann Surg Open. 2020;1:e021.

24. D’Urso A, Agnus V, Barberio M, et al. Computer-assisted quantification and visualization of bowel perfusion using fluorescence-based enhanced reality in left-sided colonic resections. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:4321-31.

25. Bannone E, Collins T, Esposito A, et al. Surgical optomics: hyperspectral imaging and deep learning towards precision intraoperative automatic tissue recognition-results from the EX-MACHYNA trial. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:3758-72.

26. Seeliger B, Agnus V, Mascagni P, et al. Simultaneous computer-assisted assessment of mucosal and serosal perfusion in a model of segmental colonic ischemia. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4818-27.

27. Loftus TJ, Altieri MS, Balch JA, et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled decision support in surgery: state-of-the-art and future directions. Ann Surg. 2023;278:51-8.

28. Schnelldorfer T, Gumbs AA, Tolkoff J, et al. White paper: requirements for routine data recording in the operating room. Art Int Surg. 2024;4:7-22.

29. Altaf A, Endo Y, Munir MM, et al. Impact of an artificial intelligence based model to predict non-transplantable recurrence among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB. 2024;26:1040-50.

30. Celotto F, Bao QR, Capelli G, Spolverato G, Gumbs AA. Machine learning and deep learning to improve prevention of anastomotic leak after rectal cancer surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2025;17:101772.

31. Marescaux J, Diana M. Next step in minimally invasive surgery: hybrid image-guided surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:30-6.

32. Okamoto N, Rodríguez-Luna MR, Bencteux V, et al. Computer-assisted differentiation between colon-mesocolon and retroperitoneum using hyperspectral imaging (HSI) technology. Diagnostics. 2022;12:2225.

33. Wang Y, Cao D, Chen SL, Li YM, Zheng YW, Ohkohchi N. Current trends in three-dimensional visualization and real-time navigation as well as robot-assisted technologies in hepatobiliary surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;13:904-22.

34. Kitaguchi D, Watanabe Y, Madani A, et al.; Computer Vision in Surgery International Collaborative. Artificial intelligence for computer vision in surgery: a call for developing reporting guidelines. Ann Surg. 2022;275:e609-11.

35. Knospe L, Gockel I, Jansen-Winkeln B, et al. New intraoperative imaging tools and image-guided surgery in gastric cancer surgery. Diagnostics. 2022;12:507.

36. Ruzzenente A, Alaimo L, Conci S, et al. Hyper accuracy three-dimensional (HA3D™) technology for planning complex liver resections: a preliminary single center experience. Updates Surg. 2023;75:105-14.

37. Salavracos M, de Hemptinne A, De Poortere T, Coubeau L. Contribution of 3D virtual modeling in locating hepatic metastases, particularly “vanishing tumors”: a pilot study. Art Int Surg. 2024;4:331-47.

38. Yang Z, Liu J, Wu L, et al. Application of three-dimensional visualization technology in early surgical repair of bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BMC Surg. 2024;24:271.

39. Huber T, Tripke V, Baumgart J, et al. Computer-assisted intraoperative 3D-navigation for liver surgery: a prospective randomized-controlled pilot study. Ann Transl Med. 2023;11:346.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].