AI as a catalyst for transforming scientific research: a perspective

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing how we conduct, scale, and reimagine scientific research. Unlike prior technologies that amplified human capability within existing paradigms, AI is redefining the very steps of scientific inquiry - from scientific hypothesis generation to experimental validation - and breaking down barriers that have long stymied progress across disciplines. AI has emerged as a transformative tool in scientific research, widely recognized for its contributions to groundbreaking achievements in highly complex domain-specific tasks. Nevertheless, beneath these remarkable successes, systemic vulnerabilities exist that threaten the authenticity of AI-enabled scientific research. Several interconnected challenges are particularly prominent: Large Language Models, now extensively employed for mining data from millions of research papers, face difficulties in extracting reliable information; AI models that learn patterns from training data may generate “hallucinations” that appear valid but are actually false or physically impossible; and both issues are amplified by a persistent lack of high-quality experimental data. Addressing these challenges is not merely a technical necessity, but also a safeguard for the integrity of scientific research.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

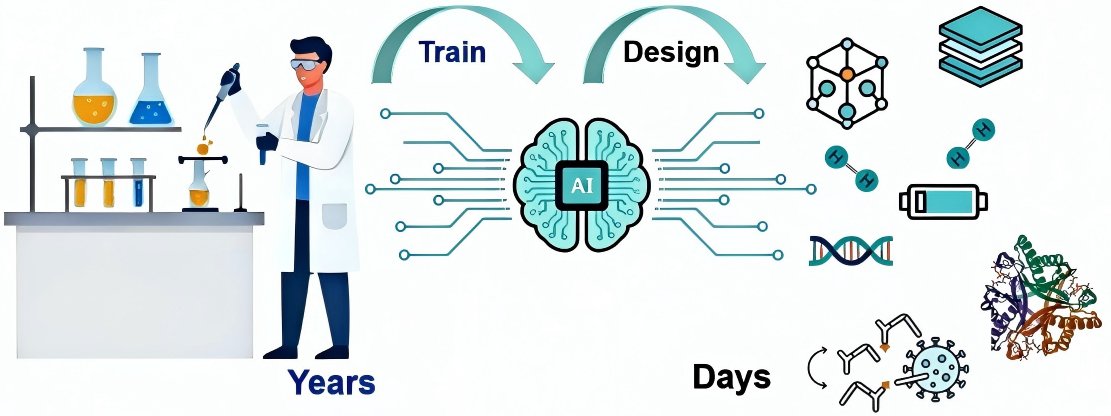

Artificial intelligence (AI) is fundamentally transforming traditional paradigms of scientific research, evolving from a mere “auxiliary tool” to a “scientific research partner” capable of generating hypotheses, designing experiments, and even discovering new knowledge. It is widely acknowledged in the academic community for its contributions to groundbreaking breakthroughs such as DeepMind’s AlphaFold[1] and AI driven climate models[2]. AI not only greatly enhances research efficiency but also reshapes research paradigms across multiple dimensions: it assists researchers in overcoming cognitive limitations to formulate more valuable research questions; it optimizes, or even autonomously constructs, research tools; it enables researchers to examine subjects more comprehensively and may uncover correlations that would otherwise be overlooked [Figure 1]. This transformation vastly expands the boundaries of human cognition, allowing us to perceive patterns and laws of the world that were previously invisible.

Figure 1. AI greatly enhances research efficiency and reshapes research paradigms across multiple dimensions. AI: Artificial intelligence.

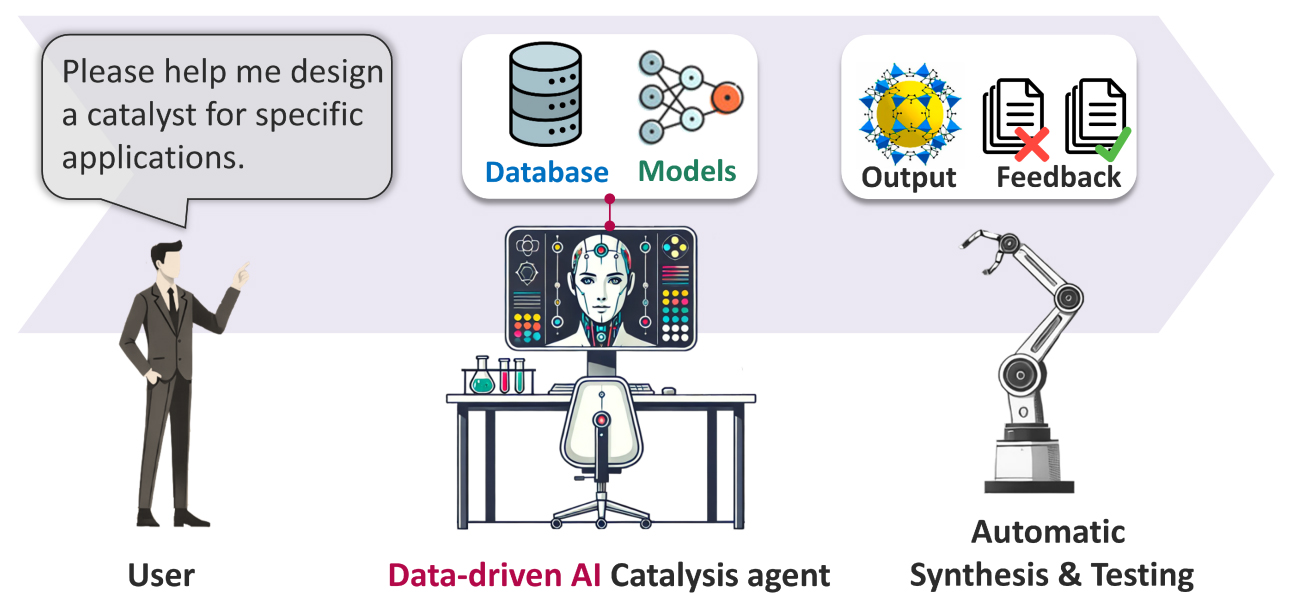

The value of AI in scientific research is first manifested in greatly improving research efficiency. In materials science, AI learns from massive material data to directly deduce new formulations, greatly compressing the material discovery process from years to weeks or even days. Pioneering research conducted by Professor Hao Li’s team from Tohoku University, integrating big data and AI tailored for materials including catalytic materials[3-6], solid-state electrolytes [Figure 2][7-9], and hydrogen storage materials[10-11], greatly accelerates the efficiency of discovering new materials with better performance. Traditionally, developing a new drug requires a decade and billions of dollars in investment, involving the testing of millions of molecular combinations. Now, AI is fundamentally changing this paradigm. Stanford University’s Virtual Lab, led by a Principal Investigator (PI) agent that autonomously directs a team of Specialist agents, designed novel nanobodies targeting Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in just a few days, significantly shortening the Research and Development (R&D) cycle[12].

Figure 2. Data-driven AI catalysis agent for catalyst discovery developed by Li et al. Reproduced with permission[3]. AI: Artificial intelligence.

Secondly, AI is driving systematic revolution in research paradigms. From the perspective of the development of science and technology, the “edifice” of science has become increasingly sophisticated, where disciplines have evolved into isolated “small houses”. As a result, making major scientific breakthroughs and solving significant technological problems has become more difficult than ever. Through its platform-based and universal characteristics, AI breaks down barriers between disciplines, facilitating interdisciplinary knowledge integration and discovery. The Shanghai AI Laboratory has released a scientific multimodal model, Intern-S1, which integrates scientific data such as protein sequences, genomes, chemical molecular formulas, and electroencephalography (EEG) signals. Optimized for scientific reasoning, it possesses rigorous logical reasoning capabilities and scientific multimodal abilities. This concept of Specialized Generalist Artificial Intelligence (SGI) is considered as a crucial milestone towards Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)[13].

Furthermore, AI significantly lowers the barrier for scientific research. Experiments that previously could only be conducted by large institutions with abundant resources can now be carried out by smaller and medium-sized teams with the assistance of AI tools. Research published in Nature Computational Science by Cui et al. from Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, demonstrated that a “digital laboratory” built using large language models (LLMs; GPT-4, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, and DeepSeek V3) successfully replicated 156 classic psychology experiments, achieving replication rates of 73%-81%[14]. This work provides a new approach for rapid validation in social science research. This means scientific innovation is no longer confined to a few elite institutions but is opening to a broader scientific community, which potentially accelerates global progress in science and technology development.

THE AI REVOLUTION IN LIFE SCIENCES

Drug research and discovery

The application of AI in drug research has achieved breakthrough progress [Table 1], which completely transforms the traditional drug discovery paradigm. The Generative AI models have become the core driving force in new drug discovery, significantly reducing the time and cost of drug development. For instance, researchers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) used generative AI models[CReM (chemically reasonable mutations) and F-VAE (fragment-based variational autoencoder)] to design two new types of antibiotics[15]:

AI applications in drug research

| Application Area | Model | Institute | Major Breakthrough |

| Antibiotic development | CReM & F-VAE | MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA | Designed two new antibiotics |

| Lead Molecule generation | ED2Mol | Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China | Generate lead molecules from scratch |

| Molecular Optimization | GAMES | SwRI, San Antonio, Texas, USA | Represent molecule using text, reduces hardware demands |

| Nanobody Design | The Virtual Lab | Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA | Designed novel COVID-19 nanobodies |

(1) NG1 (the first Neisseria Gonorrhoeae candidate), which targets drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and achieves a novel mechanism of action by disrupting bacterial membrane synthesis proteins;

(2) DN1 (the first De Novo candidate), which efficiently eliminates MRSA (Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) skin infections. It works by damaging cell membranes, thus avoiding cross-resistance with traditional antibiotics.

These models can generate over 36 million candidates, improving screening efficiency by a hundredfold compared to traditional methods.

The ED2Mol (transforming Electron Density To bioactive Molecules) technology[16], developed by Zhang et al.[16] from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, relies on AI to generate lead molecules “from scratch”, considering both orthosteric and allosteric sites. It provides a unified framework for innovative drug research and development. This technology is no longer limited to the modification of known molecular structures, but enables genuine de novo molecular design, opening up a brand-new drug discovery world. The Generative Approaches for Molecular Encodings (GAMES) model developed by Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), San Antonio, Texas, United States, specializes in understanding and generating valid molecular structures represented using Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES). By combining LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)/QLoRA (Quantized Low-Rank Adaptation) fine-tuning technologies, it greatly reduces hardware and energy needed to run Rhodium models.

Protein design and gene editing

AI demonstrates great potential in protein design, which resolves the inefficiency of traditional methods. The BindCraft technology published in Nature by researchers from EPFL (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) in Switzerland and MIT in the United States, enabled “one-shot design” of functional protein binders with an average success rate up to 46.3%[17]. In contrast, traditional methods yield a success rate of only 0.1%, representing a roughly 400-fold improvement in efficiency. By retrofitting AlphaFold2, BindCraft transforms it from a prediction tool into a design engine capable of directly generating molecules that bind to target proteins with high affinity. It has been successfully applied in multiple scenarios, including allergen blocking, gene editing regulation, and neutralization of bacterial toxins.

AI application in gene editing has also made significant progress. Profluent used LLMs to design a novel clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) protein (OpenCRISPR-1, an artificial-intelligence-generated gene editor) that can edit regions of the human genome inaccessible to traditional tools, with lower off-target rates[18]. This breakthrough shows that AI can not only optimize existing gene editing methods but also create entirely new editing tools, expanding the application scope of gene editing.

AI INNOVATION IN PHYSICAL SCIENCES

Materials science innovation

The application of AI in materials science is accelerating the process of discovering and optimizing new materials[3-11]. The A-Lab (Automated Materials Laboratory) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, California, USA) represents cutting-edge progress in this field. It applies AI algorithms to independently propose new compound formulations, while robotic systems handle the preparation and testing of these materials, forming a complete “design-synthesis-testing” closed loop. This tight integration of machine intelligence and automation significantly shortens the time required to validate new materials for use in technologies such as batteries and electronics, compressing the traditional material discovery timeline from years or even decades to just weeks or months[19].

Autoregressive LLMs show great potential in crystal structure generation. The CrystaLLM developed by Antunes et al. at the University of Reading (England, UK) treats crystal structure generation as an autoregressive text generation task and has successfully synthesized a variety of stable materials not present in the training dataset[20]. This method represents complex crystal structures as text sequences, utilizing the generative capabilities of LLMs to explore material spaces that are difficult to access with traditional methods, opening new avenues for new material discovery.

The integration of high-throughput computing and experimentation has also become a key trend in materials science. The Autobot robotic system at the Molecular Foundry of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory explores new materials for applications ranging from energy to quantum computing, making laboratory work faster and more flexible. These systems not only accelerate the materials discovery process but also provide training resources for AI models by generating high-quality, standardized experimental data, further optimizing the materials design workflow.

Progress in chemistry research

The application of AI in chemical research is expanding from molecular simulation to reaction optimization and retrosynthesis. The Token-Mol 1.0 technology[21] connects molecular 3D conformation generation with property prediction, using tokens to uniformly encode structures and properties, and comprehensively outperforms diffusion models in terms of speed and performance. This method unifies molecular representation and learning within a single framework, enabling the collaborative optimization of molecular generation and property prediction, and providing a more powerful tool for drug molecular design.

AI also demonstrates great potential in fields characterized by data scarcity. TrinityLLM achieves accurate prediction of polymer properties, where data is scarce, by leveraging physically synthesized data. This is particularly important for materials science, which traditionally relies on large amounts of experimental data, as many special materials are difficult to obtain in large quantities of samples. By using physical principles to generate synthetic data, AI models can achieve high-performance prediction and generation capabilities, though fine-tuning with experimental data is necessary[22].

The SciToolAgent[23], developed by Zhejiang University (Hangzhou, China), is an LLM-powered agent that automatically orchestrates hundreds of scientific tools across chemistry, biology, and materials science based on knowledge graphs, reshaping the interaction paradigm of multi-tool scientific workflows. The system incorporates a comprehensive knowledge base (SciToolKG) of scientific tools, ranging from general utilities to those specialized for biology, chemistry, and materials science. Each tool's profile details its input/output formats, functions, and security. When a user submits a query, an LLM-based Planner uses Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) on this knowledge base to create a tailored toolchain. This plan is then executed sequentially by an LLM-based Executor, significantly boosting the efficiency and quality of scientific workflows.

ADVANCES IN AI RESEARCH INFRASTRUCTURE AND TOOLS

Scientific Large Language Models

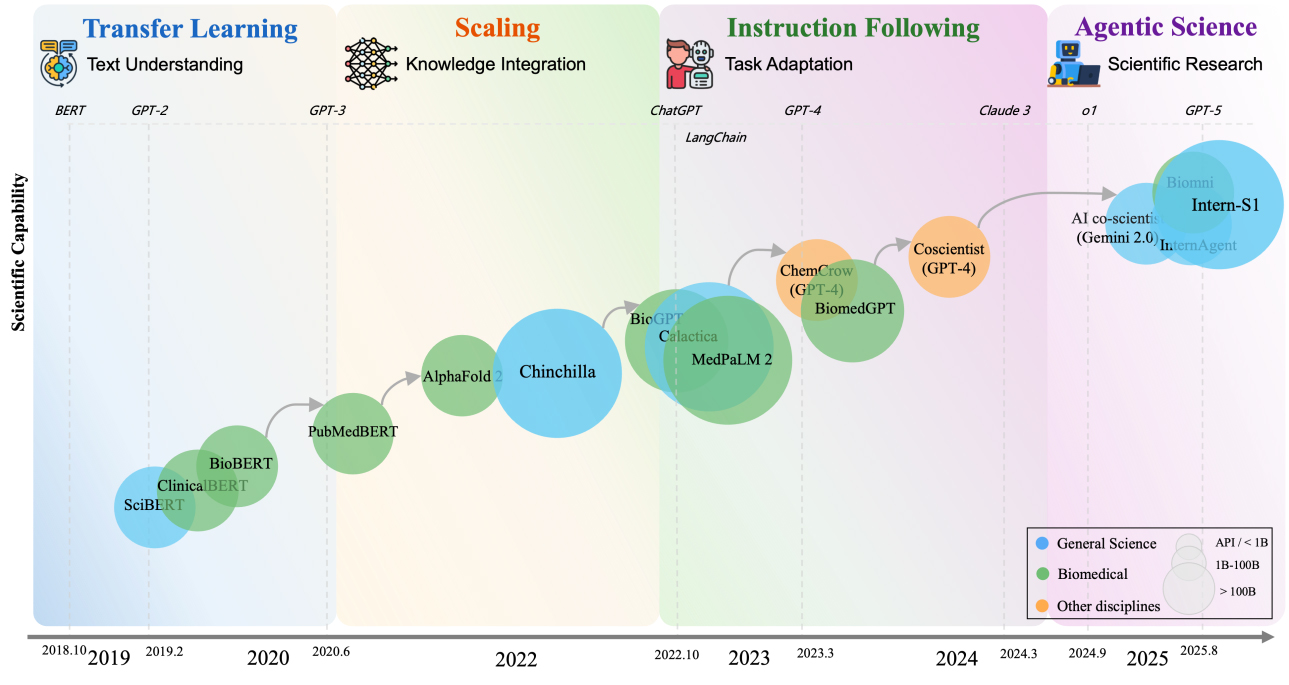

The development of Scientific Large Language Models (Sci-LLMs) has undergone four major paradigm shifts[24], gradually evolving from tools into research collaborators [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Evolution of Sci-LLMs reveals four paradigm shifts from 2018 to 2025. This figure is quoted from Hu et al.[24]. Sci-LLM: Scientific Large Language Model; SciBERT: a pretrained language model for scientific text based on BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representation from Transformers); BioBERT: a biomedical-domain language model pre-trained on domain corpora; PubMedBERT: a biomedical language model whose train set covers broader vocabulary; AlphaFold: a groundbreaking AI tool developed by Google DeepMind that predicts the 3D structures of proteins with high accuracy; Chinchilla: a family of large language models developed by the research team at Google DeepMind; MedPaLM-2: Medical Pathways Language Model 2, a medical domain fine-tuned LLM; BiomedGPT: Biomedical GenerativePre-trained Transformer, an open-source and lightweight vision–language foundation model, designed as a generalist capable of performing various biomedical tasks; Intern-S1: The Shanghai AI Laboratory has released a scientific multimodal model which integrates scientific data such as protein sequences, genomes, chemical molecular formulas, and electroencephalography (EEG) signals.

(1) The period from 2018 to 2020 marked the transfer-learning phase. Representative models included SciBERT [a pretrained language model for scientific text based on BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representation from Transformers)], BioBERT (a biomedical-domain language model pre-trained on domain corpora), and PubMedBERT (a biomedical language model whose train set covers broader vocabulary). By continuing pre-training on domain-specific scientific corpora, these models enhanced their ability to understand specialized knowledge.

(2) From 2020 to 2022, the field entered the scaling phase. Models such as GPT-3, Galactica, and MedPaLM-2 (Medical Pathways Language Model 2, a medical domain fine-tuned LLM)- powered by dramatically larger parameter scales and training datasets - demonstrated improved interdisciplinary knowledge integration and professional reasoning capabilities.

(3) From 2022 to 2024, the field entered the instruction-alignment phase. Through fine-tuning on carefully designed instruction data, representative models such as ChatGPT (a general-purpose instruction-tuned LLM), Meditron (a suite of open-source medical LLMs fine-tuned on clinical and biomedical instructions), and NatureLM (Nature Language Model, a foundational language model for the natural sciences) became capable of performing complex scientific tasks with greater precision.

(4) Since 2023, Sci-LLMs have advanced into the scientific-agent phase. Systems built around models such as Coscientist (an autonomous chemistry research agent), Biomni (a biomedical multi-agent system), and InternAgent (a general scientific agent framework) have begun to take shape. In this stage, AI no longer merely understands the concepts of science - it can autonomously design experiments, generate research papers, and iterate on research workflows.

The Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (Shanghai, China), in collaboration with over 20 top universities and research institutions worldwide, conducted a comprehensive survey of more than 1,000 academic papers, systematically organized over 600 important datasets and state-of-the-art (SOTA) models, and released a thorough review of Sci-LLMs[24]. The study revealed that approximately three-quarters of current Sci-LLMs are text-only, while multimodal LLMs account for just one-quarter. This reflects two key realities: first, the primary carriers of scientific knowledge - such as academic papers and textbooks - remain text-based; second, it highlights the scarcity of high-quality, fine-grained multimodal supervision data.

Autonomous experimentation and automated research platforms

Autonomous experimental systems are transforming traditional research methodologies, ranging from hypothesis generation to experimental validation. The A-Lab (Automated Materials Laboratory) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory applies AI algorithms to propose new compound formulations, while robotic systems handle the preparation and testing of these materials[19]. This type of autonomous scientific agent can operate continuously, significantly accelerating both the speed and scale of materials discovery.

Jointly developed by Peking University and Baidu, Inc. (Beijing, China), the ‘one-stop’ digital and intelligent life science research platform, AI4S LAB (Artificial Intelligence for Science Laboratory), deeply integrates four core elements: computing power, data, models, and experiments. It has developed a multi-agent collaborative system, providing researchers with a cloud-based research experience characterized by “AI-driven, dry-wet closed-loop, and full-chain digital intelligence”. The platform is equipped with a scalable high-performance computing cluster, more than 15 professional datasets, and over 22 sets of integrated, advanced, high-throughput, automated, and self-iterative intelligent experimental equipment, all managed by the independently developed AI4S native multi-agent system, BIOMA. BIOMA consists of a series of functionally collaborative agents: the Theoretical Scientist Agent (PredAgent), Experimental Planner Agent (ProAgent), Laboratory Commander Agent (OperAgent), and Data Analyst Agent (ComAgent). This system delivers efficient and collaborative cloud-based research capabilities, covering all stages from theoretical prediction, experimental design, and automated execution to data analysis and iteration, helping researchers break through the spatiotemporal limitations of traditional research.

CHALLENGES & OPPORTUNITIES

Limited ability to extract high-quality data from research papers

Scientific research papers form the cornerstone of the scientific knowledge system, embodying decades of accumulated experimental results, research methods, and scientific conclusions. Currently, LLMs such as GPT-4 and Claude 3 are increasingly used for mining data from research papers, integrating data required for meta-analyses, identifying research gaps, or populating scientific databases. However, the design characteristics of LLMs and the inherent traits of academic literature result in poor performance when extracting high-quality, reliable data using these models[25].

The root cause of this limitation lies in two levels of mismatch: a mismatch between the capabilities of LLMs and the diversity of scientific research papers, and a mismatch between the training methods of LLMs and the rigor required by scientific research.

First, scientific research papers themselves lack uniform standards. Formatting varies significantly across journals (e.g., the Methods section may be placed in the main text or an appendix); authors often use discipline-specific terminology or ambiguous expressions (for instance, the term “significant” may refer to statistical significance or clinical significance); and key data is frequently embedded in non-text formats such as heatmaps, flowcharts, or supplementary tables - content that LLMs struggle to parse. Empirical evidence confirms these limitations. A 2024 study in ecological research tested LLMs against human reviewers to extract data from 100 disease reports. While LLMs operated 50 times faster and achieved > 90% accuracy for discrete categorical data, they failed catastrophically with quantitative data - misidentifying geographic coordinates or inventing plausibly “precise” locations not supported by the text[26].

Second, the optimization goal of LLMs is textual coherence, not scientific accuracy. They can mimic the style of scientific writing but lack the ability to judge whether the data from a paper is internally consistent (e.g., whether the sample size in the Methods section matches that in the Results section) or externally verifiable[27,28].

In short, LLMs treat scientific research papers as “text to be summarized”, not “data to be verified”. In fields such as evidence-based medicine or materials science - where meta-analyses guide policy and innovation - these limitations make LLMs more likely to be a burden than an asset.

AI hallucinations and illusions: when plausibility masks falsity

AI “Hallucination” is used primarily to describe the model’s intrinsic generation of factually incorrect or nonsensical content (e.g., a non-existent protein structure, fabricated data points). In contrast, AI “Illusion” is generally used to describe the human cognitive error of overestimating their understanding or the model's capabilities when interacting with AI outputs that appear plausible. For clarity, we adopt this terminology consistently in the following sections.

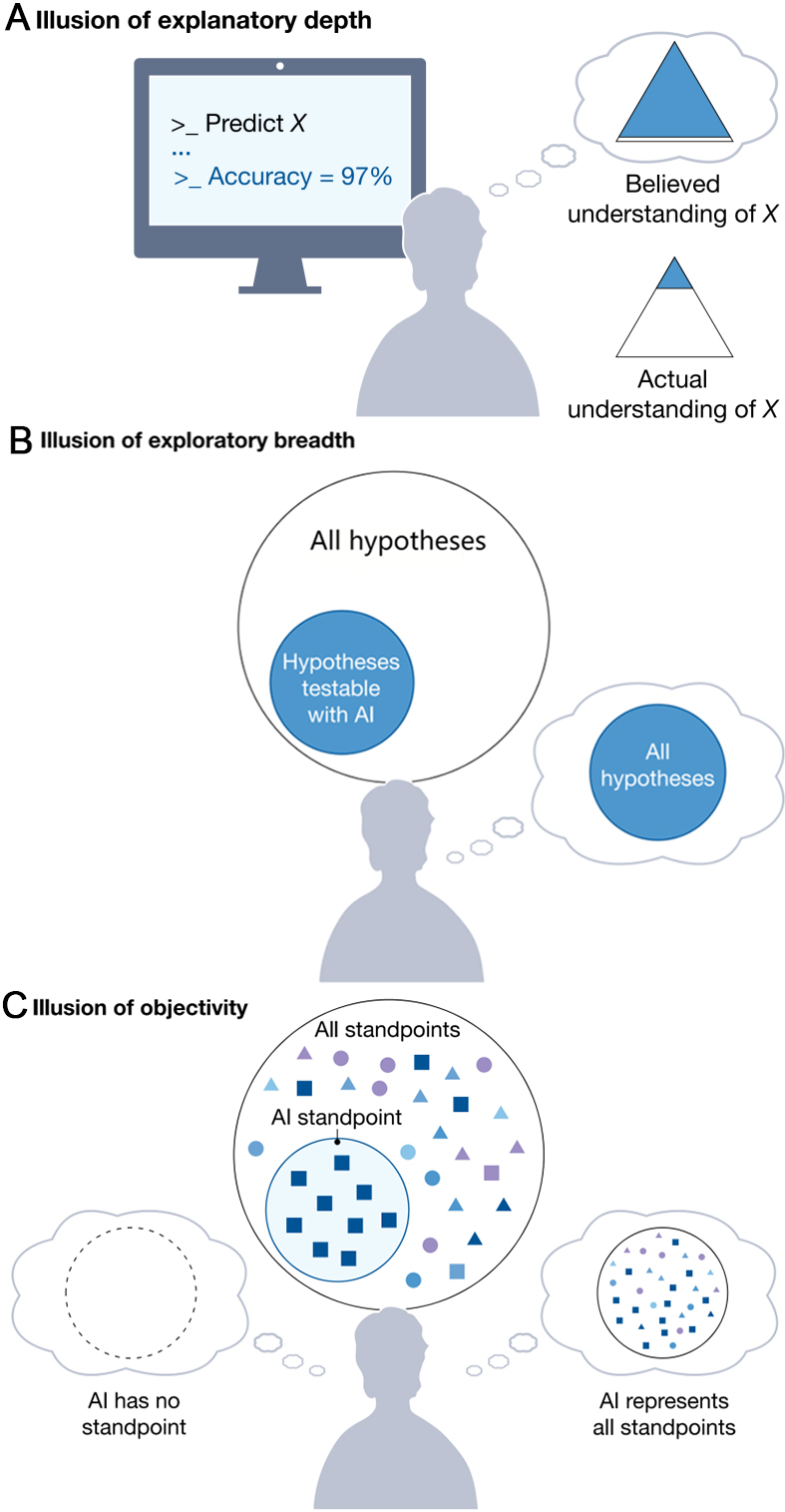

Scientific futures integrated with AI have been proposed, featuring the prevalence of ‘self-driving’ laboratories, generative AI replacing human participants, and ‘AI scientists’ authoring research papers[29]. While such proposals may seem akin to science fiction, they have been published in renowned scientific journals and are actively advanced with the backing of influential institutions. These proposed AI solutions can also exploit our cognitive limitations. Specifically, treating AI tools as scientific collaborators makes scientists vulnerable to illusions of understanding, a class of metacognitive errors that arise from holding incorrect beliefs about the nature of one’s understanding, as shown in Figure 4[29].

Figure 4. Illusions of understanding in AI-driven scientific research: (A) Scientists using AI (e.g., AI Quant) to model a phenomenon (X) may suffer from an illusion of explanatory depth, overestimating their actual understanding of X; (B) In a monoculture of knowing, scientists face an illusion of exploratory breadth: they falsely think they explore all testable hypotheses, but only cover a narrow subset testable via AI; (C) In a monoculture of knowers, an illusion of objectivity arises: scientists incorrectly assume AI has no standpoint or covers all standpoints, whereas AI tools embed the standpoints of their training data and their developers. This figure is quoted from Lisa Messeri & M. J. Crockett[29]. AI: Artificial intelligence.

Even cutting-edge generative models fall prey to this flaw. While AI-driven de novo protein design has yielded Nobel-prize-winning breakthroughs, the “hallucinated” molecular structures often violate basic chemical constraints unless grounded in experimental data. Worse, these illusions are not random: they align with dominant scientific narratives, risking confirmation bias by reinforcing existing hypotheses rather than challenging them. As Wang et al. noted in a 2023 Nature review, AI’s tendency to prioritize pattern consistency over empirical truth creates a “credibility gap” that undermines its utility[30].

A more insidious threat is AI “Hallucination” - the generation of outputs that appear scientifically credible but are factually incorrect, which involves AI fabricating or distorting data to fit a desired pattern. As is commonly known, all kinds of generative AI, including the LLMs behind AI chatbots, make things up. The particular problem of false scientific references is rife. A 2024 study found that a range of chatbot models exhibited error rates of approximately 30% to 90% in reference citations, misreporting at least two key elements: the paper’s title, first author, or year of publication[31]. AI lacks ‘scientific skepticism’. A human researcher would question a catalyst that defies thermodynamics or a cell pattern that appears unusually perfect. AI, by contrast, only verifies whether its output aligns with training data. Without external validation - typically through physical experiments - AI hallucinations can easily be mistaken for genuine scientific findings, potentially leading to serious consequences.

To mitigate these risks, several technical strategies are being developed. Uncertainty quantification techniques can help flag model predictions with low confidence, prompting further scrutiny. Adversarial validation methods, where models are tested against deliberately misleading or out-of-distribution data, can help identify blind spots and improve robustness. Hybrid symbolic-AI approaches, which integrate logical reasoning and physical constraints (e.g., laws of thermodynamics) into data-driven models, can ground AI outputs in established scientific principles, reducing hallucinated responses with physically impossible characteristics. Additionally, strategies such as disagreement-based triage and out-of-distribution detection can trigger human review. These approaches are complementary and should be selected based on task risk and the availability of validation data.

The irreplaceable role of high-quality experimental data

AI is transforming scientific discovery, but its impact hinges on high-quality experimental data. Rich, accurate, and well-annotated measurements provide ground truth to train and calibrate models, constrain hypotheses to physically plausible regimes, and reveal failure modes that purely computational pipelines miss. In closed-loop systems, experimental feedback enables active learning to focus effort where uncertainty is highest, accelerating convergence while preventing spurious conclusions[3,19]. Quality here means reproducible protocols, instrument calibration, rigorous analysis, uncertainty quantification, and metadata that captures conditions and context.

Recent work shows that experimental data is not merely supportive - it is determinative. In autonomous materials discovery, experiments validate computational targets, diagnose misses, and guide recipe optimization[19]. In protein design, high-throughput characterization and crystallography separate feasible designs from hallucinations, informing model improvements and priors[32,33]. AlphaFold’s[1] breakthrough in protein structure prediction, for instance, was not merely a triumph of algorithm design but of data integration. The model leveraged decades of experimentally resolved protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database and multi-sequence alignments derived from genetic databases, fusing this data with physical constraints (e.g., stereochemical rules) to ensure biological plausibility. In autonomous characterization, machine learning steers instruments in real time, but only reliable measurements allow algorithms to make confident decisions regarding phases and intermediates[34]. Across domains, robust experimental datasets enable benchmarking, uncover distribution shift, and provide the constraints that keep AI models aligned with the real world.

Practically, this entails coupling AI with (1) precise characterization [e.g., X-ray diffraction (XRD), electron microscopy (EM), crystallography]; (2) standardized data pipelines with automated analysis; and (3) uncertainty-aware decision-making. When implemented, AI and experimentation form a virtuous cycle: models propose, experiments test and refine, and updated data improve subsequent proposals. Without this integration, AI risks optimizing proxies and drifting from reality. The lesson is clear: scientific AI requires the discipline and fidelity of the laboratory to be trustworthy, generalizable, and impactful. In many clinical and research settings, the scarcity of high-quality medical imaging datasets has hampered the potential of AI clinical applications[35]. As noted by the Shanghai AI Laboratory in its 2025 Sci-LLM review, the scarcity of high-quality, multimodal experimental data remains the single greatest barrier to AI4S advancement[24].

CONCLUSION: TOWARDS A “DATA-DRIVEN” AI FOR SCIENCE

AI has the potential to accelerate scientific discovery[36] - but only if we address its vulnerabilities. The limitations of LLMs in extracting paper data, the risk of AI illusions and hallucinations, and the primacy of high-quality experimental data all point to a need for a “data-first” approach to AI in science: one where data quality is prioritized over algorithmic flash, and where AI is treated as a tool for validating science, not a replacement for it. Because AI applications often involve large-scale and unstructured data, automated or technology-assisted human-in-the-loop methods are needed to systematically address the data challenges[37]. Researchers provide critical oversight by curating high-value training datasets, designing reward functions that encapsulate scientific rigor, interpreting AI-generated hypotheses and results with skepticism, and ultimately validating findings through physical experimentation. Careful design and maintenance of data can make AI solutions more valuable across academia and industry[38].

To achieve this, three steps are critical. First, the scientific community must adopt universal standards for data reporting - such as mandatory Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) compliance for journal publications - to make research papers more LLM-friendly and less error-prone. Second, AI developers must integrate physical constraint checks into models; for example, quantum chemistry AI solutions should be programmed to respect thermodynamics, and climate AIs to account for geographic limits. Third, funding agencies should commit sustained investment in systematic data curation and research replication, positioning data quality as a research priority rather than a peripheral consideration. Ultimately, science is about understanding the real world - and the real world cannot be reduced to patterns in text or code. AI can help sift through vast amounts of information, generate hypotheses, and design experiments, but it is high-quality experimental data that connects those ideas to reality. The future of AI for science lies not only in building smarter algorithms, but also in constructing smarter, more rigorous data ecosystems. Only then can AI be regarded as a trusted partner in scientific advancement..

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Suzhou MatSource Technology Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China).

Authors’ contributions

Literature investigation: Ma, P.; Li, L.

The original preparation of the manuscript: Ma, P.; Li, L.

Validation: Xu, K.; Su, R.; Gu, H.

Review and editing of the manuscript: Xu, K.; Su, R.; Gu, H.

All authors participated in the conceptualization and design of the research topic and have approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was funded by the Gusu Laboratory of Materials (Suzhou, China), grant number Y2501.

Conflicts of interest

Ma, P. is an Editorial Board Member of the journal AI Agent and was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. Li, L.; Xu, K.; Su, R.; Gu, H.; Ma, P. are affiliated with Suzhou MatSource Technology Co., Ltd. and have declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583-9.

2. Camps-Valls, G.; Fernández-Torres, M. Á.; Cohrs, K. H.; et al. Artificial intelligence for modeling and understanding extreme weather and climate events. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1919.

3. Zhang, D.; Li, H. Digital catalysis platform (DigCat): a gateway to big data and AI-powered innovations in catalysis. ChemXiv 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-9lpb9 (accessed 10 December 2025).

4. Jia, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, F.; et al. Closed-loop framework for discovering stable and low-cost bifunctional metal oxide catalysts for efficient electrocatalytic water splitting in acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 22642-54.

5. Zhang, D.; Li, H. The hidden engine of AI in electrocatalysis: databases and knowledge graphs at work. Molecular. Chemistry. &. Engineering. 2025, 1, 100003.

6. Zhang, D.; She, F.; Chen, J.; Wei, L.; Li, H. Why do weak-binding M-N-C single-atom catalysts possess anomalously high oxygen reduction activity? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 6076-86.

7. Yang, F.; Campos Dos Santos, E.; Jia, X.; et al. A dynamic database of solid-state electrolyte (DDSE) picturing all-solid-state batteries. Nano. Mater. Sci. 2024, 6, 256-62.

8. Yang, F.; Sato, R.; Cheng, E. J.; et al. Data-driven viewpoint for developing next-generation mg-ion solid-state electrolytes. J. Electrochem. 2024, 30, 2415001.

9. Wang, Q.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; et al. Unraveling the complexity of divalent hydride electrolytes in solid-state batteries via a data-driven framework with large language model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202506573.

10. Zhang, D.; Jia, X.; Hung, T. B.; et al. “DIVE” into hydrogen storage materials discovery with AI agents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.13251. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.13251 (accessed 10 December 2025).

11. Li, C.; Yang, W.; Liu, H.; et al. Picturing the Gap Between the Performance and US-DOE’s Hydrogen Storage Target: A Data-Driven Model for MgH2 Dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202320151.

12. Swanson, K.; Wu, W.; Bulaong, N. L.; Pak, J. E.; Zou, J. The virtual lab of AI agents designs new SARS-CoV-2 nanobodies. Nature 2025, 646, 716-23.

13. Zhang, K.; Qi, B.; Zhou, B. Towards building specialized generalist AI with system 1 and system 2 fusion. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.08642. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.08642 (accessed 10 December 2025).

14. Cui, Z.; Li, N.; Zhou, H. A large-scale replication of scenario-based experiments in psychology and management using large language models. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2025, 5, 627-34.

15. Krishnan, A.; Anahtar, M. N.; Valeri, J. A.; et al. A generative deep learning approach to de novo antibiotic design. Cell 2025, 188, 5962-5979.e22.

16. Li, M.; Song, K.; He, J.; et al. Electron-density-informed effective and reliable de novo molecular design and optimization with ED2Mol. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 1355-68.

17. Pacesa, M.; Nickel, L.; Schellhaas, C.; et al. One-shot design of functional protein binders with BindCraft. Nature 2025, 646, 483-92.

18. Ruffolo, J. A.; Nayfach, S.; Gallagher, J.; et al. Design of highly functional genome editors by modeling the universe of CRISPR-Cas sequences. Nature 2025, 645, 518-25.

19. Szymanski, N. J.; Rendy, B.; Fei, Y.; et al. An autonomous laboratory for the accelerated synthesis of novel materials. Nature 2023, 624, 86-91.

20. Antunes, L. M.; Butler, K. T.; Grau-Crespo, R. Crystal structure generation with autoregressive large language modeling. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10570.

21. Wang, J.; Qin, R.; Wang, M.; et al. Token-Mol 1.0: tokenized drug design with large language models. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4416.

22. Liu, N.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Lattimer, B. Y.; Ni, S.; Lua, J.; Yu, Y. Harnessing large language models for data-scarce learning of polymer properties. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2025, 5, 245-54.

23. Ding, K.; Yu, J.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H. SciToolAgent: a knowledge-graph-driven scientific agent for multitool integration. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2025, 5, 962-72.

24. Hu, M.; Ma, C.; Li, W.; et al. A survey of scientific large language models: from data foundations to agent frontiers. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.21148. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.21148 (accessed 10 December 2025).

25. Ghosh, S.; Brodnik, N.; Frey, C.; et al. Toward reliable ad-hoc scientific information extraction: a case study on two materials dataset. In 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11-16, 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, USA, 2024; pp 15109-23.

26. Daraqel, B.; Owayda, A.; Khan, H.; Koletsi, D.; Mheissen, S. Artificial intelligence as a tool for data extraction is not fully reliable compared to manual data extraction. J. Dent. 2025, 160, 105846.

27. Whang, S. E.; Roh, Y.; Song, H.; Lee, J. Data collection and quality challenges in deep learning: a data-centric AI perspective. The. VLDB. Journal. 2023, 32, 791-813.

28. Wang, F. Y.; Miao, Q. H. Novel paradigm for AI-driven scientific research: from AI4S to intelligent science. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2023, 38, 536-40.

29. Messeri, L.; Crockett, M. J. Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research. Nature 2024, 627, 49-58.

30. Wang, H.; Fu, T.; Du, Y.; et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 2023, 620, 47-60.

31. Jones, N. AI hallucinations can't be stopped - but these techniques can limit their damage. Nature 2025, 637, 778-80.

32. Watson, J. L.; Juergens, D.; Bennett, N. R.; et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 2023, 620, 1089-100.

33. Ingraham, J. B.; Baranov, M.; Costello, Z.; et al. Illuminating protein space with a programmable generative model. Nature 2023, 623, 1070-8.

34. Szymanski, N. J.; Bartel, C. J.; Zeng, Y.; Diallo, M.; Kim, H.; Ceder, G. Adaptively driven X-ray diffraction guided by machine learning for autonomous phase identification. NPJ. Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 31.

35. Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, Y.; et al. Self-improving generative foundation model for synthetic medical image generation and clinical applications. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 609-17.

36. Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, X.; et al. Artificial intelligence: a powerful paradigm for scientific research. Innovation. (Camb). 2021, 2, 100179.

37. Liang, W.; Tadesse, G. A.; Ho, D.; et al. Advances, challenges and opportunities in creating data for trustworthy AI. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 669-77.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].