Mid- and long-term outcomes of hypoabsorptive metabolic and bariatric procedures

Abstract

Metabolic and bariatric surgery remains one of the most effective interventions in the management of obesity and its associated medical conditions. The field has continuously grown to now encompass newer procedures that include one-anastomosis gastric bypass, single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy, sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition, and single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass. These procedures were developed with an aim to tackle current weight loss challenges and safety concerns that tend to present with the more common procedures. Taken together, they have been shown to induce excess weight loss ranging from 64% to 93% over 5 to 10 years, contribute to near-complete resolution of obesity-associated medical conditions, and simultaneously achieve lower rates of complications. However, as most of the current literature reports short-term outcomes, this review aims to identify and discuss their long-term efficacy and safety profiles, emphasizing the need for standardized guidelines that would encourage wider adoption and optimize patient outcomes.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Obesity has emerged as one of the most pressing global health challenges of the 21st century, affecting over 650 million adults worldwide - a condition closely associated with increased morbidity and mortality from type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain malignancies[1,2]. Long-term projections suggest a continued upward trend, with nearly half of the adult population in some countries expected to meet the criteria for obesity within the next two decades[3]. These alarming statistics underscore the urgent need for durable, effective treatment strategies beyond lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions. Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) is widely recognized as the most effective treatment for severe obesity, resulting in sustained weight loss, improvement of obesity-related medical conditions, and reductions in all-cause mortality. Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) have emerged as the most commonly performed procedures due to their proven efficacy and acceptable risk profiles[4-6]. However, a subset of patients experiences suboptimal weight loss, recurrent weight gain, or inadequate improvement in comorbid conditions following these operations, potentially due to their restrictive nature, particularly after SG[7-9]. Higher baseline body mass index (BMI), advanced age, and complex metabolic or psychiatric comorbidities may also reduce the effectiveness of these standard approaches[10,11]. As a result, there is growing interest in identifying procedures that can address these challenges and broaden the therapeutic reach of MBS. One-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with SG (SADI-S), SG with transit bipartition (SG-TB), and single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass (SASI) have been developed with an aim to enhance metabolic outcomes while maintaining acceptable safety profiles and technical feasibility[12,13]. What characterizes those newer procedures is their hypoabsorptive nature aimed at decreasing the absorption of nutrients rather than just restricting food intake, which is the hallmark of restrictive procedures such as SG. In particular, OAGB and SADI-S were developed with a simplified surgical technique designed to enhance metabolic and weight-related outcomes and reduce complications. SG-TB and SASI, similarly, have also been developed with an aim to produce more effective outcomes while modifying nutrient pathways and hormonal mechanisms[14]. It is also important to distinguish “hypoabsorption” and “malabsorption”; while they have long been used interchangeably, the word “mal” means abnormality and tends to have a more negative connotation, rendering “malabsorption” as a term reflecting a diseased state or intestinal injury. Hypoabsorption, however, simply refers to a decreased absorption resulting from an altered, rather than impaired, surgical anatomy[15]. Nevertheless, widespread adoption has been tempered by safety and technical concerns and a relative lack of long-term outcome data[16-19]. This review aims to focus on the long-term outcomes, i.e., beyond five years, of emerging surgical innovations to first identify gaps in the current literature, highlight the necessity of developing standardized guidelines that would encourage wider adoption and optimize patient outcomes, and address limitations in current practice.

METHODS

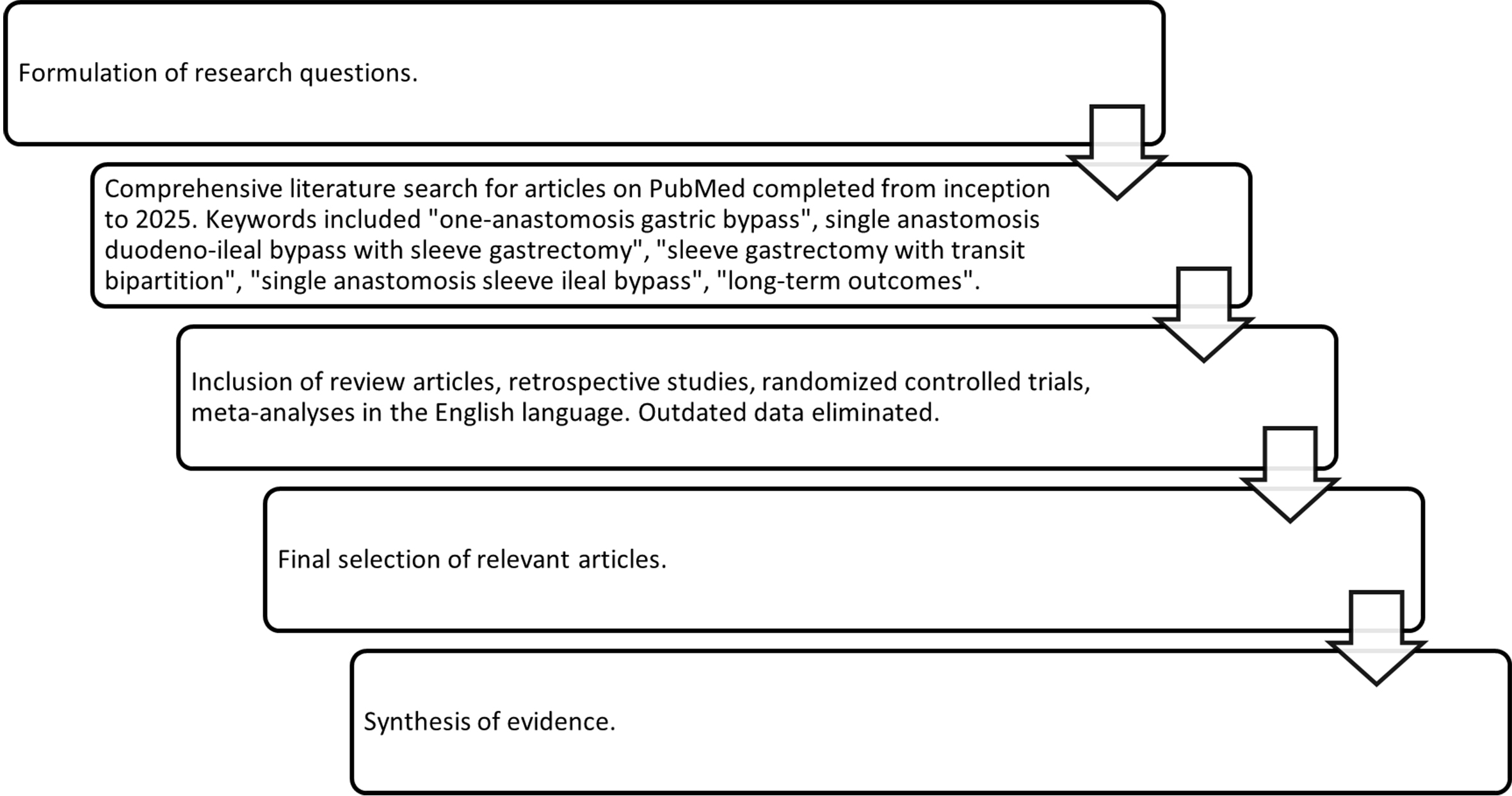

The authors conducted a structured narrative literature review to identify recent advancements, evaluate their clinical impact, and highlight ongoing debates and areas requiring further investigation. The review process was carried out as follows: (1) formulation of guiding research questions and identification of relevant emerging surgical techniques; (2) literature search and article selection; and (3) synthesis of evidence with attention to clinical relevance, gaps in practice, and implications for individualized patient care. The selection of relevant studies and articles was based on a PubMed search conducted between March 2025 and April 2025. The search included keywords such as “bariatric surgery”, “minimally invasive”, “hypoabsorptive” and “long-term”. After clearly identifying the outline and subsections of the manuscript, articles were selected based on their discussion of these newer hypoabsorptive procedures and their long-term outcomes. All authors participated in the development of the review protocol, screening of articles, and critical appraisal of selected studies. The corresponding author supervised the final selection process of relevant articles and contributed an expert interpretation of the findings [Figure 1]. Following the final selection of studies, a comprehensive summary of the evidence synthesized was generated and can be found in Table 1.

Long-term outcomes of hypoabsorptive metabolic and bariatric procedures

| Procedure | Weight loss | Obesity-related medical conditions | Complications and safety | Nutritional outcomes |

| OAGB | %TWL: 33.4% (10 years), 32.1% (15 years) %EWL: 81.8% (5 years), 64.1% (10 years), 62.9% (15 years) | Remission rates: T2DM: 94% HTN: 94% HLD: 96% OSA: 90% | Overall rate: 4.5%-10.3% Marginal ulcers: 1%-6% Hernias: lower rates than other procedures Stenosis: not reported Gallstones: not reported | Possible deficiencies in calcium, folate, vitamin D, vitamin B12, iron, zinc and magnesium Secondary hyperparathyroidism: 73.6% |

| SADI-S | %TWL: 22.5%-38% (5 years), 34.4% (10 years) %EWL: 58.6%-80.7% (5 years), 80.4% (10 years) | Remission rates: T2DM: 90% HTN: 54%-85.1% HLD: 51.4%-73.3% OSA: 42.9%-96% | Overall rate: 11% Marginal ulcers: not reported Hernias: 0%-0.57% Stenosis: 0.3% Gallstones: 7.7% | Possible deficiencies in vitamins A, E, zinc and folic acid Iron deficiency anemia: 3.03% |

| SG-TB | %TWL: 21% (4 years) %EBMIL: 74%-79.4% (4-5 years) | Remission rates: T2DM: 86% HTN: 72% HLD: 70% OSA: 91% | Overall rate: 10.2% (4 years) Marginal ulcers: 0.7% Hernias: 3.1% Stenosis: 2.3% Gallstones: 21.9% | Possible deficiencies in vitamin B12 and iron (3 years) |

| SASI | %TWL: 41.2% (4 years) %EWL: 93.3% (4 years) | Remission rates: T2DM: 93% (4 years) HTN: 73% (4 years) HLD: 83% (4 years) OSA: 79% (4 years) | Overall rate: 4.6% Marginal ulcers: 0.3% Hernias: 0% Stenosis: 1.1% Gallstones: 2.4% | Severe protein-energy malnutrition: 7.4% (3 years) Hypoalbuminemia: 1.3% (1 year) Hypocalcemia: 0.2% (1 year) Preservation of vitamin D, vitamin B12, iron and ferritin within normal ranges (3 years) |

OAGB

Definition and trends

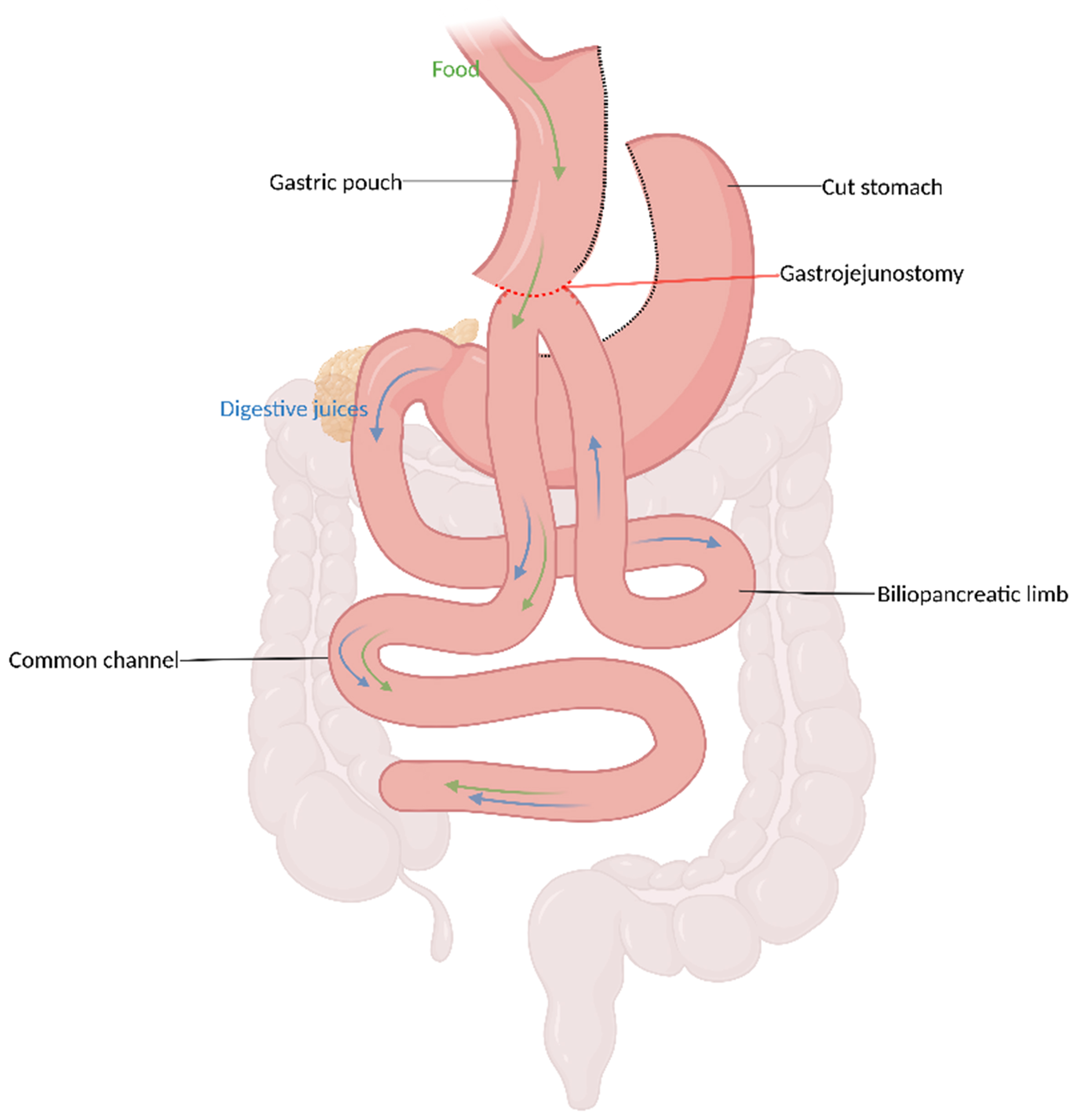

OAGB is a metabolic and bariatric procedure that combines hypoabsorptive and hormonal methods. Since 2011, it has been gaining traction worldwide and currently accounts for 1.5% of all procedures, owing to its technical simplicity, effectiveness, and positive outcomes[14,20]. Its novelty and appeal potentially stem from its modification of the well-known RYGB, creating a single rather than double anastomosis, which simplifies both the technique and the anatomy. The procedure also forms a smaller gastric pouch, promoting earlier satiety. The jejunum is then bypassed to create a 150-200 cm biliopancreatic limb (BP) and an end-to-side gastrojejunostomy [Figure 2][14,21]. OAGB has thus been shown to produce significant and sustained weight loss outcomes that have been found to be associated with the resolution of obesity-related medical conditions, such as type 2 diabetes[21]. It was endorsed by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) in 2022[22] and is currently included in the procedures outlined in the “International Federation for Surgery and Other Therapies for Obesity (IFSO) Consensus on Definitions and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity Management” and the 2025 ASMBS fact sheet[23].

Figure 2. OAGB. Created in BioRender. El Ghazal, N. (2026) https://BioRender.com/0e3jzh1. OAGB: One-anastomosis gastric bypass.

Indications and patient selection

OAGB is indicated in patients with BMIs ≥ 40 kg/m2 or ≥ 35 kg/m2 and concurrent obesity-related medical conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HLD), or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Higher BMIs are also encountered preoperatively owing to OAGB’s hypoabsorptive features when compared to RYGB[14]. OAGB can also be considered as a revisional procedure in those who have regained weight or had a poor metabolic response after previous procedures such as SG or adjustable gastric banding (AGB)[24-26]. Contraindications do exist for this procedure; as OAGB is derived from the loop gastric bypass, it might increase the risk of biliary reflux and anastomotic ulcers[24], making it less suitable for patients with severe reflux or Barrett’s esophagus[14,24]. Surgeons have also expressed concerns over the risk of gastric and esophageal cancer[24]. Other contraindications include primary or secondary short-gut syndrome and Crohn’s disease[26].

Long-term outcomes

Weight loss

Long-term outcomes of OAGB have shown promising results in patients with severe obesity. Neuberg et al. evaluated the procedure’s long-term safety, efficacy and impact on quality of life. At 5, 6, 7, and 8 years of follow-up, respective mean BMI reductions were 12.6, 11.8, 10.7, and 8.8 kg/m2, respectively. The corresponding mean percentage excess weight loss (%EWL) was 81.8%, 75.9%, 69.1%, and 62.3%. After a median follow-up of 92 months, 86% of patients reported an improved or significantly better quality of life. The study also demonstrated improvement and/or complete remission in all obesity-related medical conditions[27]. Another long-term study with a mean follow-up of 149 months assessed patients who underwent OAGB as a primary (52%) or revisional (48%) procedure after AGB or SG. The authors demonstrated a mean %TWL of 33.4% and a mean %EWL of 64.1% at ten years, with similar results at 15 years (32.1%TWL, 62.9%EWL). Of note, no significant differences were found in weight loss outcomes between the primary and revisional OAGB cohorts (P = 0.47) and between patients with preoperative BMIs below and above 50 kg/m2 (P = 0.61). They also recorded that a %EWL of more than 75% was achieved by 43% and 49% of patients at 10 and 15 years of follow-up, respectively[28]. When compared to RYGB, the YOMEGA trial (NCT02139813) showed non-inferiority of OAGB at 2 years, with a mean percentage excess BMI loss (%EBMIL) of 87.9%, as compared to 85.5% in the RYGB group[24].

Obesity-related medical conditions

OAGB has also been shown to positively influence a patient’s metabolic profile in the long term. Carbajo et al. evaluated 1,200 patients who had laparoscopic OAGB and followed them for 6-12 years; they demonstrated significant improvements or remission of obesity-related medical conditions. Remission and improvement rates in T2DM, HTN, HLD and OSA were as follows: 94% and 6% (T2DM), 94% and 6% (HTN), 96% and 4% (HLD), 90% and 10% (OSA). No esophagitis cases were reported during follow-up endoscopy[29]. Almuhanna et al. similarly followed 2,223 patients who underwent OAGB over a period of 20 years. They showed a rise in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol from 44.3 to 52.5 mg/dL, a significant decrease in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol from 130.7 to 90.3 mg/dL, and a greater than 60% drop in triglycerides by year five. Complete T2DM remission [hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) < 6.0%] rates were 67.2% at 5 years, rose to 73.8% at 10 years and marginally declined to 66.7% at 15 years. Ten percent showed significant improvement (HbA1c < 7.0%), while 3.9% had partial remission (HbA1c < 6.5%) after 5 years[30].

Complications and safety

Despite the long-term effectiveness of OAGB, several early and late complications can occur following the procedure. In the early postoperative period, leaks have been recorded at a rate between 0.1% and 1.9%, while bleeding represented less than 3% of all complications. Dumping syndrome, internal hernias and small bowel obstructions have also been reported in the early postoperative period[29]. Carandina et al. reported a 9.8% incidence of biliary reflux, 4.9% of ulcers, 2.7% of severe anemia, and 2.3% of significant malnutrition - defined as %EWL > 50% combined with hypoalbuminemia (< 30 g/L) - requiring rehospitalization, highlighting the importance of adequate follow-up and adherence to postoperative protocols[28]. Another study showed a 14% rate of recurring acid reflux and a 3% rate of reoperation 90 days following initial OAGB[31].

More importantly, late complications that tend to present after OAGB are bile reflux, marginal ulcers and stomal stenosis. The current literature reports an overall rate of late complications between 4.5% and 10.3% at 5 years[32]. Rates of bile reflux have ranged between 5% and 10%, where some patients necessitated surgical intervention[28]. Marginal ulcers can also present in 1%-6% of patients, and the risk seems to increase in those who smoke or use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and in cases where ischemic tissues are present near the anastomosis[33]. Severe bile reflux and marginal ulcers refractory to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and sucralfate can be managed effectively with revisional procedures. Some dietary changes and medications such as acarbose and somatostatin (octreotide) can be used to address dumping syndrome. Stomal stenosis is another late complication that may require reoperation[33]. The rates of internal hernias, however, have been reported to be lower than those after other procedures[34].

Nutritional outcomes

OAGB’s hypoabsorptive component can lead to nutritional deficiencies in calcium, folate, vitamin D, vitamin B12, iron, and zinc, and in a few cases, severe malnutrition necessitating revisional surgery[35]. Syn et al., however, demonstrated at 5 years of follow-up greater folate levels in OAGB and RYGB when compared to SG [mean difference (MD) = 2.376 ng/mL, P < 0.001] but lower levels of magnesium (MD = -0.25 mg/dL, P < 0.001) and zinc (MD = -7.58 μg/dL, P < 0.001) that might lead to neuromuscular and immune dysfunction. There were no reported differences in levels of parathyroid hormone, vitamin D, iron or ferritin between SG and the combined OAGB and RYGB group[36]. However, Wei et al. have reported higher prevalences of secondary hyperparathyroidism 5 years after OAGB (73.6%), followed by RYGB (56.6%) and SG (41.7%)[37].

Patient care and follow-up

Effective preoperative preparations, such as dietary limitations, medication management and psychological assessments, are essential to optimize patient outcomes. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or upper gastrointestinal (GI) series may be helpful in evaluating a patient’s anatomy to rule out anomalies that might present challenges during surgery[21]. Postoperatively, recommended follow-up times are every three months for the first year and then annually thereafter, where patients are advised accordingly regarding their diets, nutritional supplementation if needed and physical activity. Regular laboratory tests are performed to monitor bone density, liver function tests, vitamins D and B12, folate, and calcium, while ensuring adherence to supplementation to prevent complications and deficiencies[29,38]. The 2020 IFSO position statement also recommends EGD surveillance to be undertaken at 1 year following OAGB, and then after every 2-3 years, with the aim of detecting marginal ulcers, Barrett’s esophagus or any upper GI malignancy early on[39,40].

Early detection and prevention of complications

Careful preoperative and perioperative planning, as well as adherence to regular follow-up appointments and nutritional recommendations, is essential in preventing and detecting challenges that may arise in the postoperative period. This necessitates frequent imaging, laboratory testing, and clinical assessments as indicated, and educating patients about potential signs or symptoms that require increased medical attention, such as fever, chest pain, neurological changes, abnormal bleeding, persistent heartburn, nausea, and epigastric pain[33]. Individuals already on nutritional supplementation would require regulation of those supplements to ensure consistent nourishment over a long-term period[41]. Avoiding high-fat or high-volume meals, as well as consumption of probiotic-rich foods, can help prevent bile reflux[33]. PPIs can also be given preoperatively to reduce the risk of ulcers after OAGB in select patients[41]. Nevertheless, several studies have suggested that altering the length of the BP limb based on past surgical procedures and BMI may increase benefits and reduce potential complications. For instance, a longer BP limb has been associated with greater weight loss following OAGB but might come at the expense of nutritional deficiencies or malabsorption. A shorter BP limb, while associated with fewer deficiencies, might increase the risk of bile reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Other authors have also advised adopting a 400 cm common channel (CC) length to counter the decreased absorptive area that comes with BP limb lengthening and potentially reduce postoperative micronutrient deficiencies[42].

SADI-S

Definition and trends

The SADI-S, a 2020 ASMBS-endorsed procedure[19] included in the IFSO consensus and the ASMBS 2025 fact sheet[23], is a relatively recent advancement in MBS, designed to simplify the traditional biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) while preserving its metabolic benefits. It has been gaining traction both in the United States (US) and internationally, currently accounting for 1%-2% of all procedures in the US - a small but steadily increasing share[5].

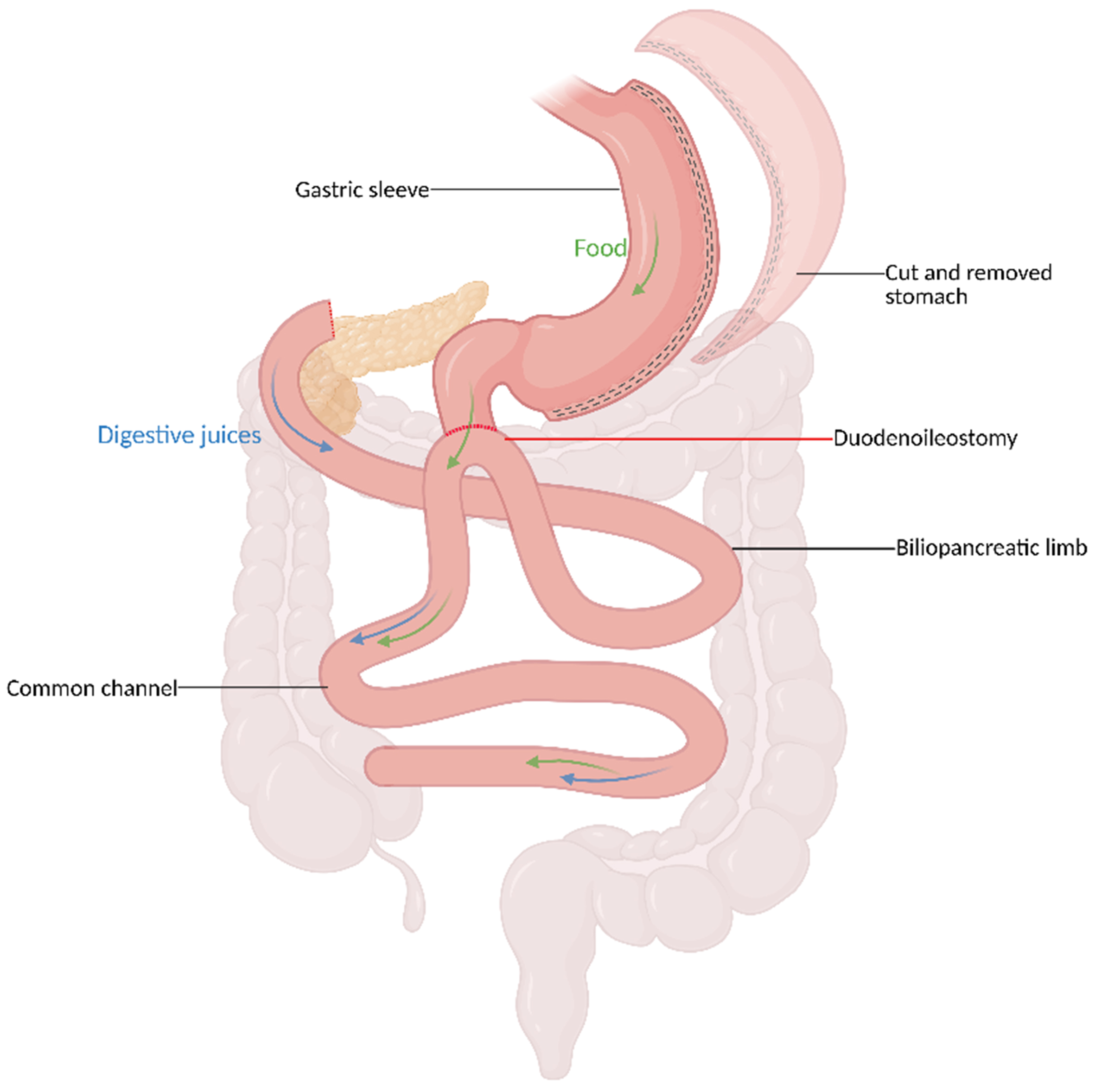

The hallmark of SADI-S is the presence of a single anastomosis at the duodenal cuff. This key difference reduces procedural complexity and may lower the risk of complications compared to BPD/DS, which involves two anastomoses - one at the duodenum and another at the ileum[43-45]. It begins with a SG followed by dissection of the duodenum distal to the pylorus. A single duodeno-ileostomy is created 250-300 cm from the ileocecal valve to form a loop serving as the CC through which nutrients are absorbed [Figure 3][43]. The preservation of the pylorus helps slow gastric emptying, reduces the risk of dumping syndrome, and maintains more physiologic satiety signaling - all of which enhance the procedure’s safety and efficacy[46,47]. Initially, shorter CC lengths in SADI-S mirrored the nutrient malabsorption issues seen in BPD/DS, such as protein-calorie malnutrition and anemia. Most surgeons now create longer CCs to strike a balance between effective weight loss and reduced nutritional deficiencies, which makes it an appealing alternative for patients requiring significant metabolic improvement while avoiding hypoabsorptive-related complications[48-50].

Figure 3. SADI-S. Created in BioRender. El Ghazal, N. (2026) https://BioRender.com/1yjre1p. SADI-S: Single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy.

Indications and patient selection

Indications include severe obesity (BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2), multiple metabolic comorbidities, or failure of other weight loss interventions[51]. SADI-S may be favored over RYGB or SG in patients who require more potent metabolic intervention, particularly when diabetes resolution is a high priority[18,51,52]. Individuals with significant GI disease or concerns about long-term nutritional compliance may be better suited to alternative procedures, as SADI-S can present with nutritional risks that necessitate consistent monitoring and follow-up. SADI-S is also increasingly used in the revisional surgery setting[52]; by building on an existing sleeve anatomy and avoiding gastric pouch revision, it can serve as a second-stage procedure in cases of suboptimal weight loss outcomes after SG. The duodeno-ileal bypass component also provides additional glycemic control by enhancing hormonal and metabolic changes through the bypassed foregut[51-53], making it effective in cases of unresolved or recurrent T2DM. With appropriate patient selection and follow-up, SADI-S seems to offer substantial benefits with a reduced risk profile compared to more complex diversionary procedures.

Long-term outcomes

Weight loss

SADI-S has demonstrated significant efficacy in promoting weight loss in both the short and medium term. Shoar et al. reported progressive improvements in %EWL: 30% at 3 months, 55% at 6 months, 70% at 12 months, and 85% at 24 months. Similar findings were reported in a study demonstrating an average %EWL of 78.7% and %TWL of 36.8% at 12 months[54-56].

When examining longer-term outcomes, data remain more limited but are also encouraging. IFSO reported that only 11 SADI-S studies evaluated long-term weight loss results (beyond 5 years), with a reported %EWL ranging from 58.6 to 80.7% and %TWL from 22.5 to 38%[57]. Of these studies, only one demonstrated data at or beyond 10 years, showing a %EWL of 80.4% and %TWL of 34.4%[57]. Other long-term studies showed sustained outcomes at 5 and 10 years, with %EWL of 87% and 80%, respectively[58]. SADI-S also appears effective across a range of BMI categories, though outcomes may vary based on preoperative weight. Enochs et al. found that patients with a baseline BMI below 45 kg/m2 achieved 95%EWL at 12 and 24 months. In contrast, those with significantly higher baseline BMIs experienced lower but substantial weight loss[18]. Despite this expected inverse relationship, such results support the use of SADI-S for patients with higher BMI.

When compared to RYGB, SADI-S showed better weight loss outcomes over a five-year period. However, BPD/DS had a slight edge in both %EWL and %TWL, highlighting SADI-S as a slightly less hypoabsorptive but more balanced alternative[48]. In the long term, weight regain was infrequent (1/139 patients required revision surgery for inadequate weight loss)[58]. Overall, SADI-S offers an effective, versatile option for primary and revisional bariatric surgery.

Obesity-related medical conditions

Short-term studies have consistently shown that most patients experience either significant improvement or complete remission of diabetes (normalized glucose levels without the need for medication)[59]. Remission rates were reported between 60% and 85%[53,56], can increase to 90% after 2-4 years postoperatively[53,59], and are further maintained beyond 5 years[53]. These outcomes highlight SADI-S as a reliable and powerful option for long-lasting improvement in glycemic control, likely due to its roots in the metabolically intensive BPD/DS procedure.

Resolution rates of HTN have been reported in up to 96% of patients in early follow-up, with sustained improvements in 63% to 80% of patients at longer-term checkpoints[53,55]. Medium- and long-term (5-6 years of follow-up) remission rates have also ranged between 64.4%-75% and 54%-85.1%, respectively. Data at 10 years, although rare, have shown remission rates of 75%[57]. Dyslipidemia remission has been shown to range between 68.2%-100% and 31.2%-55.6% after primary and revisional SADI-S, respectively, in the short- term. Those rates were further maintained at medium (64.4% to 76.9%) and long-term (51.4% to 73.3%) follow-up. OSA remission rates have ranged between 42.9% to 96%[53,57,60]. These findings support the broader metabolic benefits of SADI-S, not just in weight loss but in meaningful and lasting improvements in overall health, comorbidity burden, and life expectancy[61].

Complications and safety

While SADI-S is generally safe, it can present with short- and long-term complications[62]. The current literature reports a 30-day complication rate between 2.6%-11%[62,63], with many studies reporting no 30-day mortality[62]. Some short-term complications reported after primary and revisional SADI-S in a systematic review included GI bleeding (1.1%), wound infections (1.0%), anastomotic leaks (0.9%), intra-abdominal abscesses (0.6%), small bowel perforations (0.4%), sleeve leaks (0.4%), and duodenal stump leaks (0.3%)[63].

Long-term complications are also relatively lower for SADI-S, with rates around 11%, with less than 6% requiring any type of re-intervention[49]. A recent comparative study by Salame et al. reported no marginal ulcers among patients who underwent SADI-S, compared to a 1.03% rate among those who had BPD/DS[46]. Although marginal ulcer formation remains a theoretical risk, particularly in patients with known risk factors such as smoking or NSAID use, the preservation of the pylorus in SADI-S reduces exposure of the anastomosis to highly acidic gastric contents[64]. Bile flow near the anastomotic site helps neutralize stomach acid, offering additional protection. Preservation of the pylorus also allows the stomach to empty into the small bowel in a controlled manner, reducing the likelihood of dumping syndrome, with reported rates below 0.8%[46]. Since SADI-S involves only one anastomosis, the risk of anastomotic stricture or stenosis remains low[58,62,65,66], with a reported incidence of stenosis of 0.3%[49]. SADI-S also carries a reduced risk of internal hernias compared to RYGB and BPD/DS, largely due to its simplified anatomy without a Roux limb, with rates ranging between 0% and 0.57%[49,62]. Although some surgeons choose to close mesenteric defects during SADI-S to further minimize this risk, others consider it unnecessary given the low reported rates[67]. Rates of gallstone disease necessitating cholecystectomy have been reported at 7.7%[58].

SADI-S, however, is associated with a slightly higher long-term risk of reflux compared to RYGB and BPD/DS due to the preserved sleeved stomach, which increases intragastric pressure, and disruption of sling fibers near the gastroesophageal junction[17]. A recent meta-analysis showed occurrences of both acid and bile reflux, but rarer rates of biliary reflux reported at 1.23% vs. 7.6% for acid reflux[68]. Nerve injury from extensive pyloric dissection can also lead to biliary sphincter dysfunction, increasing reflux susceptibility[69]. In cases of persistent GERD, conversion to RYGB is preferred due to its more favorable impact on reflux[17,68]. In the revisional setting, however, SADI-S is associated with a lower incidence of upper GI complications when compared to OAGB, making it a safer choice in this context[70].

Nutritional outcomes

Despite superior weight loss outcomes when compared to RYGB, patients undergoing SADI-S experienced similar nutritional outcomes[48]. Iron deficiency anemia incidence was low at 3.03%, particularly when compared to up to 40% rates after BPD/DS[49]. Micronutrient deficiencies, such as vitamin A, E, zinc, and folic acid deficiencies, tend to occur infrequently[50]. Some patients developed steatorrhea within the first year postoperatively, but symptoms responded to dietary modifications and agents such as Loperamide or Cholestyramine[49]. The low incidence of nutritional complications is largely attributed to the 300 cm common limb length adopted for SADI-S[71], but consistent postoperative vitamin and mineral supplementation remains essential.

Patient care and follow-up

As with all MBS procedures, preoperative evaluation is conducted by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) to determine suitability, provide nutritional counseling and psychological evaluations. Postoperative management involves appropriate diet advancements and regular monitoring of nutritional status, including vitamin and mineral levels, to prevent deficiencies[72,73]. Adherence to prescribed supplementation regimens and scheduled follow-up appointments is essential in monitoring weight loss progress and comorbidity resolution.

Early detection and prevention of complications

Due to the higher long-term risk of reflux following SADI-S, regular follow-up and symptomatic evaluations are warranted to prevent or detect reflux development early on and treat appropriately. First-line interventions include acid-suppressing medications. Diagnostic assessments such as pH impedance studies can distinguish acid from bile reflux. If a hiatal hernia is present, surgical repair may improve symptoms. In cases of isolated bile reflux, conversion to BPD/DS with a 60 cm Roux limb may be considered. Severe, refractory acid or bile reflux may require conversion to RYGB[17]. As mentioned above, malnutrition can be effectively prevented by avoiding short common limb lengths; a retrospective cohort study demonstrated more deficiencies in iron, vitamin D and folic acid in patients subject to a ≤ 250 cm CC length when compared to a > 250 cm one, and only the ≤ 250 cm group presented with severe protein energy malnutrition[74]. This necessitates consideration of CC length of at least 250-300 cm[71,74], but to date, the optimal CC length remains subject to debate.

SG-TB AND SASI

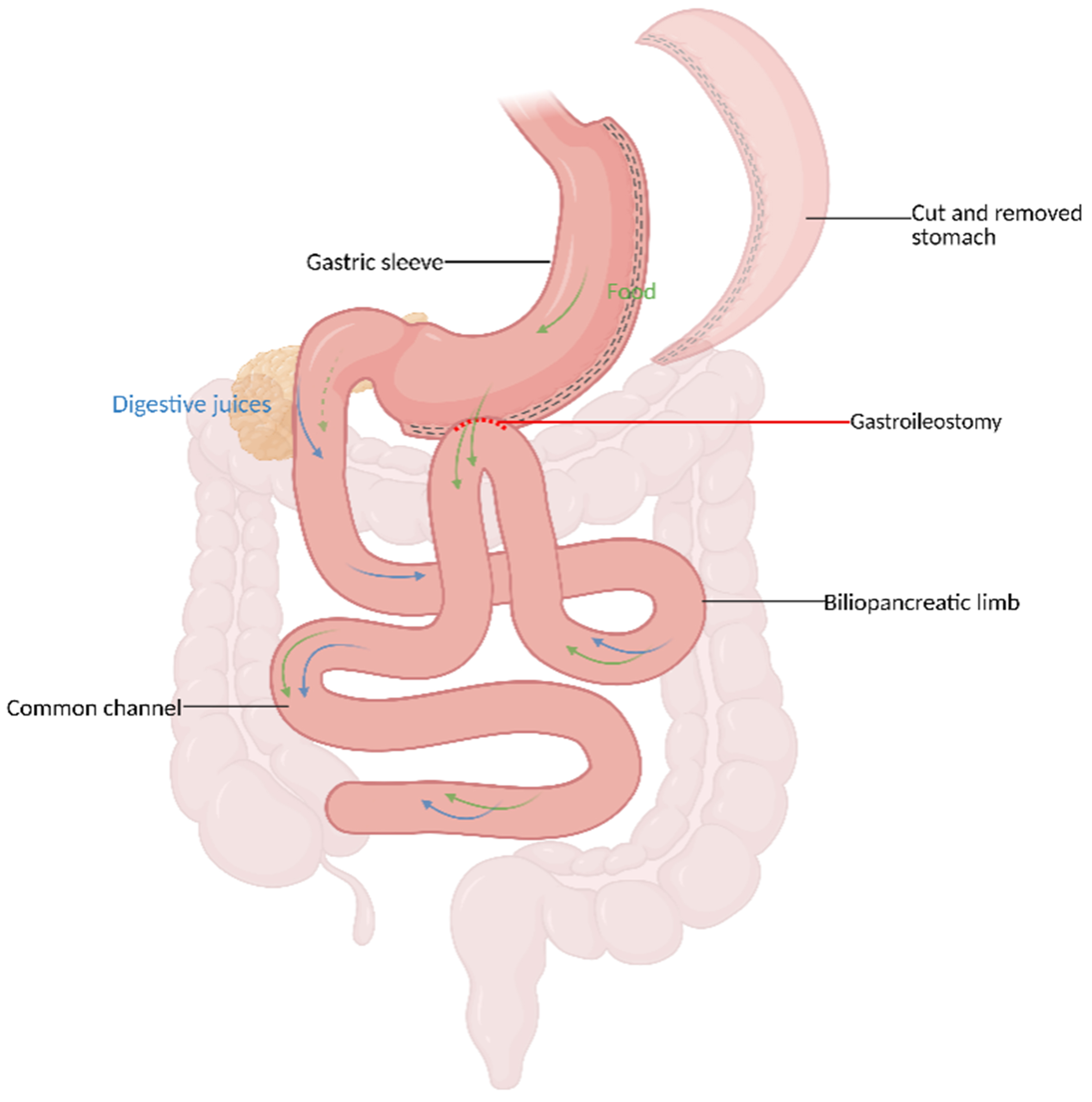

SG-TB, or simply referred to as gastric bipartition (GB), is a relatively new procedure that was first offered by Haddad et al. in 2006. SASI was later developed as a modification of SG-TB to eliminate the second anastomosis. Despite their anatomical differences, their aim was to improve weight loss and obesity-related medical conditions by achieving early diversion of food and altering gut hormones[75].

SG-TB

Definition and trends

Initially described as “Digestive Adaptation with Intestinal Reserve” (DAIR) in 2004, the primary objective of SG-TB was to minimize nutrient exclusion and malabsorption - challenges associated with more “popular” techniques such as RYGB or BPD/DS - and to enhance the neuroendocrine GI response to food ingestion, thereby contributing to weight loss and improvement in diabetes[76]. The authors also aimed to avoid blind endoscopic areas that would make gastroscopy and gastric cancer screening impossible[77]. This approach resulted in the creation of an SG with preservation of the pylorus, an omentectomy, and a partial enterectomy, leaving part of the jejunum and an open duodenum still in transit, hence the name “transit bipartition” [Figure 4]. They further hypothesized that preservation of these digestive segments could potentially decrease the risk of liver impairment that would otherwise be exacerbated by nutrient exclusion and bacterial translocation to portal blood[76]. Adoption of this newer anatomical approach to achieve these aims has somewhat increased the procedure’s attractiveness. However, to date, there are no reported trends or sufficient literature regarding this newer procedure, which has not been fully endorsed by the ASMBS[5] and therefore does not meet the standards set by IFSO[23]; consequently, the available evidence from current studies largely serves as investigational data rather than guidance for clinical practice.

Figure 4. SG-TB. Created in BioRender. El Ghazal, N. (2026) https://BioRender.com/oz5hb0b. SG-TB: Sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition.

Indications and patient selection

The procedure’s simpler technique, preservation of nutrient absorption, and favorable outcomes make it an attractive alternative for a wide selection of patients. Indications include patients aged 18 to 65 years belonging to any BMI category[78], as well as those with a BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2, with or without concomitant obesity-related medical conditions. When SG is not advised - particularly due to concerns regarding worsening GERD, weight regain, and poorly controlled diabetes - SG-TB can be an effective alternative[14]. Additional indications include patients at risk of developing gastric cancer or precancerous lesions, as the anatomy of this procedure preserves the distal stomach and parts of the small bowel, allowing successful endoscopy, in contrast to RYGB[77].

Long-term outcomes

Weight loss

As SG-TB has yet to become a standardized procedure with widespread adoption, most of the literature focuses on short-term outcomes with a 2- to 3-year follow-up[79,80]. However, it still demonstrates favorable weight loss and metabolic outcomes, even when compared with standard medical therapy[81]. Long-term results, however, have been studied in animal models, where SG-TB has been shown to be superior to SG[82] and RYGB[83] in terms of weight loss and diabetes control.

Santoro et al. were among the first to report the long-term outcomes of SG-TB on weight, obesity-related medical conditions, nutritional status and safety in a series of 1,020 patients between 2004 and 2011. They demonstrated a mean %EBMIL of 72.2% at 6 months, peaking at 2 years to reach 94.1% to steadily decreasing back to 74% at 5 years of follow-up[84]. Although there exists a paucity of studies looking at outcomes beyond 5 years, short- and mid-term results have shown promising effects; Calisir et al. reported a 77.9%EWL and a 33.84%TWL at 3 years postoperatively[77,85]. Of note, Topart et al. showed that at 2 years, despite BPD/DS achieving superior weight loss outcomes when compared to SG-TB, more complications were reported after BPD/DS[77,86]. In another study, they showed SG-TB’s significant superiority over RYGB in terms of weight loss (TWL 44.8% vs. 38.4%, P < 0.0001)[77,87]. Outcomes at 4 years in Taskin and Al’s study revealed a 79.4%EBMIL and a 21.0%TWL[78].

Obesity-related medical conditions

Achieving adequate glycemic control, especially in the setting of poorly remitted diabetes after any other MBS procedure, remains a crucial goal due to the long-term adverse effects of insulin resistance on metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular outcomes, morbidity and mortality. As such, by minimizing mechanical restriction and hypoabsorption and inducing metabolic changes, SG-TB has shown promising and effective results in the control of diabetes. Santoro et al. demonstrated an 86% complete remission rate and a 14% partial remission rate of T2DM, where patients still required or restarted oral diabetic agents postoperatively[84]. They also showed a 91%, 85% and 70% resolution rate of OSA, hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia, respectively. Additionally, 72% of patients with a preoperative diagnosis of HTN no longer required medications after surgery[84]. Similarly, complete T2DM remission was seen in 86.4% of patients at 4 years of follow-up[78]. Significant decreases in fasting blood glucose, insulin and HbA1c were also reported by Calisir et al. at 3 years of follow-up[85]. A 2-year comparison between SG-TB and RYGB showed higher remission rates of all obesity-related medical conditions after SG-TB, but significant findings were only achieved in OSA[87].

Complications and safety

Santoro et al. demonstrated a 6% early 30-day complication rate that mostly consisted of fistulas, bleeding that needed transfusion and intestinal obstruction. There was also a 1.9% reoperation and 0.2% mortality rate. More importantly, the late complications reported were cholelithiasis (21.9%), incisional hernias (3.1%), intestinal obstruction related to adhesions (2.4%) that did not manifest with severe presentations, stenosis (2.3%) and ulcers (0.07%). GI symptoms, such as flatulence, diarrhea or changes in bowel movements, were not a major concern, although most patients reported soft stools and an increase in frequency of bowel movements[84]. Zhao et al. highlight that diarrhea seems to be a common complication after SG-TB[77]. Three cases of stenoses requiring endoscopic dilation were reported[84]. A 10.2% late complication rate was observed by Taskin and Al, with no deaths reported[78]. No major late complications were observed in the 3-year study by Calisir et al.[85].

Nutritional outcomes

Santoro et al. generally reported good nutritional outcomes, with no occurrences of protein malnutrition, hypoalbuminemia, or chronic anemia with hemoglobin levels below 10 g/dL. Although patients were started on supplementation preoperatively, no additional vitamins or minerals were given beyond calcium, cholecalciferol, and thiamine[84]. Key findings from the study by Taskin and AI included significant increases in the number of patients within normal nutritional reference ranges at 4 years postoperatively[78]. Calisir

Patient care and follow-up

Patient care in the pre- and postoperative periods follows what has been discussed above. MDT evaluations, education about long-term follow-up and post-procedure expectations, nutritional counseling, and symptomatic assessments for the prevention and detection of complications are all essential to optimize outcomes[88]. As no current recommendations exist for SG-TB specifically, actions taken by Santoro et al. can be used as foundations for future guidelines. In their long-term study, they advised their patients to avoid refined sugars postoperatively and to enroll in a physical activity program to further aid in weight loss. They also provided them all with multivitamins and PPIs for the first 2 months or longer if needed. Follow-up visits were later conducted at 10 days, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and then annually thereafter, with respective blood tests and abdominal imaging[84].

Early detection and prevention of complications

Adequate and annual follow-up ensures timely prevention and detection of cholelithiasis or diarrhea, which are the most commonly reported complications after SG-TB. Nutritional status seems to follow favorable outcomes, with few deficiencies occurring in the long-term postoperatively[78,84,85], but monitoring vitamin and mineral levels and providing supplementation would still be necessary. Although there remains limited literature surrounding the optimal or adequate CC length needed to minimize postoperative complications, few studies have evaluated postoperative outcomes across different CC lengths. Short- and mid-term studies have shown higher incidences of diarrhea with a 250 cm CC when compared to 300 cm, while others demonstrated no differences between the groups. Micronutrient levels were also found to be similar. Greater weight loss was achieved with the shorter length, and this could be explained by the reduced nutrient absorption following this shortening[89,90]. Nevertheless, Santoro et al. recently reported comparative outcomes of their long-term study evaluating patients with different CC lengths (80-100, 120-150, 200-

SASI

Definition and trends

The SASI is a novel MBS procedure introduced in 2016 by Professor Tarek Mahdy. Rooted within the principles of gastric bypass and Santoro’s operation, the SASI protocol involves a SG followed by a side-to-side gastro-ileal anastomosis[92]. Mahdy et al. aimed to modify Santoro’s SG-TB method to perform a single-loop anastomosis instead of the Roux-en-Y transit bipartition [Figure 5]. This newer and modified anatomical approach has encouraged Mahdy et al. to evaluate the efficacy of SASI on neuroendocrine management of patients with obesity and T2DM[92].

Figure 5. SASI. Created in BioRender. El Ghazal, N. (2026) https://BioRender.com/orh2his. SASI: Single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass.

Since SASI was introduced less than a decade ago, and as of 2022 has yet to be formally recognized by the ASMBS[5] and to eventually meet the current IFSO standards[23], most of the existing literature has concentrated on short-term outcomes, with 3-36 months of follow-up, as seen in a recent meta-analysis of 1,700 patients[93]. Although not negligible, this number of SASI cases pales compared to the thousands of SG and RYGB procedures conducted annually[5]. Its endorsement worldwide, especially within the US, has been gradual yet continually growing, with countries adopting it as a primary procedure[93,94] while others implementing it within investigational capacity due to the limited long-term data[94,95]. As a result, there remains a significant gap in research regarding the long-term effects of SASI, particularly beyond 5 years.

Indications and patient selection

An extensive review (n = 1,463 patients) has discovered that patients undergoing SASI had BMIs ranging from 35.05 to 58.3 kg/m2, with 53.23%, 75%, 91.77%, and 44.78% having T2DM, HLD, GERD, and HTN, respectively[96]. SASI was shown to be a suitable option for patients who experience severe obesity in conjunction with T2DM and GERD, owing to the procedure’s design around a gastro-ileal bypass to mediate hormonal changes that disrupt glycemic control[96]. SASI can be indicated as a primary procedure in select patients with the willingness to adhere to postoperative follow-up for hypoalbuminemia screening following excessive weight loss[97], and for long-term EGD visits[98]. It can also be considered as a revisional procedure after suboptimal weight loss outcomes following SG[99]. Nonetheless, all patients must consent that they understand that SASI is a novel procedure with limited long-term data available[94].

Long-term outcomes

Weight loss

Direct long-term data on the SASI procedure are scarce, with most of the literature focusing on the short-term, yet positive, outcomes[92]. For this reason, comparisons can be drawn between SASI and the single anastomosis sleeve jejunal (SASJ) bypass, a modification of SASI featuring a shorter BP limb, and the SG-TB procedure, the direct predecessor of the SASI, given the similarities between all three procedures[77,100].

The SASI has demonstrated robust short and mid-term weight loss outcomes, with patients reaching nearly 90%EWL at 1 year[92,94], 110.5% at 2 years and 93.3% at 4 years of follow-up[94]. %TWL started at 39.3% after 1 year, with slight but consistent improvements to reach 41.2%TWL at 4 years[94]. Although preliminary results suggest that the SASI will likely be durable at and beyond the five-year follow-up, there are no directly published outcomes that show evidence for this claim. However, similar procedures such as SASJ and SG-TB have shown great promise. A retrospective cohort review of the SASJ bypass showed that most patients have lost significant weight, with only 0.15% of the cohort experiencing suboptimal weight loss at 5 years[101]. BMI was also shown to decrease from 44.3 preoperatively to 28.3 kg/m2 after 5 years[101]. SG-TB has shown similar promising results, with a 74%EBMIL[14,90]. %EWL tends to peak at the 2-year mark but typically plateaus off at the 4- or 5-year mark, and significant weight regain has not been an issue with any of these procedures. The available weight loss data regarding SASI and its adjacent procedures indicate that it is a sustainable procedure, showing positive results at multiple follow-up timepoints.

Obesity-related medical conditions

One of the hallmark benefits of SASI is its contribution in resolving various obesity-related medical conditions such as T2DM. A retrospective cohort study demonstrated that 100% of patients achieved normal blood glucose levels within 1 year[92]. SASI has also shown superior outcomes in the management of T2DM, with 97.7% of patients experiencing improvement, compared to 86.7% following OAGB and 71.4% following SG[102]. Furthermore, long-term SASJ data suggest sustained remission of T2DM, with rates reaching 98.5% after 6 years[90]. A 4-year follow-up of SASI reported remission rates of 93% for T2DM, 73% for HTN, 83% for HLD and 79% for OSA[94], which has been strongly associated with concomitant weight loss. Corroborating these findings may suggest that the resolution of cardiometabolic comorbidities tends to strengthen over time, with longer follow-up periods pointing towards more pronounced improvements. SASI has been shown to be effective in reducing the prevalence of GERD in the short- and long-term, with a 25% rate of complete remission, 29% rate of significant improvement, and 46% rate of no change at 4 years of follow-up[14,94].

Complications and safety

A few intraoperative and postoperative complications have been described after SASI. Three studies have collectively reported three intraoperative complications (leak, enterotomy, splenic bleeding) in total[103,104], while another retrospective cohort study showed a 0% rate[94]. This highlights its procedural safety when performed with proper surgical technique and its viability as a lower-risk intervention when compared to other alternatives. A large systematic review reported a mean operative time of 111.3 min, which was similar to other procedures. It found an overall early and late complication rate of 12.3%, which mostly consisted of bilious vomiting (n = 31), diarrhea (n = 19), hypoalbuminemia (n = 12), marginal ulcer (n = 8), and bleeding (n = 7)[105].

Short-term complications tend to be more common, with an overall 2.5% reported incidence that can include pulmonary embolisms, trocar site herniation, intrabdominal bleeding, and leak at the gastroileal anastomosis complicated by sepsis[94]. Abdominal and intraluminal bleeding at the site of the procedure can also present in the short term[96,103,104]. Less commonly, biliary gastritis, hematemesis, dysphagia, diarrhea, short bowel and vomiting were reported in 3 studies[95,103,104]. Long-term complications have been reported at a 4.6% rate, with occurrences of gastroileal anastomotic stenosis, stomal ulcers, gallstones (2.5%-43.3%), significant changes in bowel movement (diarrhea or constipation) and excess weight loss needing reversal to SG. The most significant safety concern with SASI in the mid- to long-term period, however, is the potential for malnutrition if the bypass is too aggressive[94,105,106].

Nutritional outcomes

One of the key advantages of SASI is the inclusion of the duodenal route, which maintains nutritional absorption, unlike RYGB and BPD/DS[92]. A mid-term SASI outcomes study showed that substantial nutritional improvements were preserved at 3 years of follow-up, including significant reductions in fasting glucose (99.8 to 84.8 mg/dL), HbA1c (5.6% to 5.1%), and insulin levels (24.5 to 7.9 mIU/L), and improved lipid profiles[94]. Most vitamin and nutritional markers remained within normal ranges, with improvements in vitamin D (23.2 to 34.7 ng/mL) and B12 status (451.2 to 853.1 pg/mL) and mild decreases in hemoglobin (14.1 to 13.2 g/dL) and ferritin (132.6 to 87.8 ng/mL)[94].

A 6-year follow-up study of the SASJ protocol can offer insights into the sustained efficacy and metabolic impact of SASI. Patients who underwent SASJ demonstrated maintenance of hematological and nutritional markers within normal ranges over the follow-up period. Hemoglobin levels showed slight fluctuation but recovered to a mean of 12.5 ± 1 g/dL at 5 years, with only 3.2% of patients showing mild anemia. Vitamin D deficiency was common preoperatively but improved significantly with supplementation throughout follow-up. Calcium and albumin levels stayed stable[101].

However, nutritional complications may occur if the bypass is too aggressive. A large-scale meta-analysis of 941 patients reported a 1.3% rate of hypoalbuminemia and a 0.2% rate of severe hypocalcemia[105]. Despite the seemingly low rates, Kamal et al. present unpredictable malnutrition outcomes after the SASI due to gastric limb lengths ranging on the shorter side of 250 cm. Sixty-three percent of patients faced severe malnutrition, with 15 needing revisional surgeries for immediate remediation[106]. Severe protein-energy malnutrition has also been reported in another study in up to 7.4% of patients, but it was effectively resolved in most cases through surgical reversal of the bypass[107]. In anticipation of nutritional complications, opting for SASJ seems reasonable; its modification of the SASI procedure with a shorter biliary limb could minimize nutritional deficiencies, at least when compared to SASI in the short term. A recently published randomized controlled trial has demonstrated lower rates of protein energy malnutrition and anemia, as well as fewer late complications needing revisional surgeries, following SASJ when compared to SASI after 1 year of follow-up[108].

Patient care and follow-up

A successful SASI largely depends on a patient’s adherence to a postoperative care plan and follow-up routine to ensure that if complications arise, they are caught as early as possible and managed accordingly[94,95,104]. During early post-operative evaluations, a gastrografin swallow test and an upper endoscopy may be conducted to check for two-way passages, anastomotic strictures, and biliary gastritis[94]. Those tests are reserved if the patient presents with epigastric pain or reflux or has risk factors for ulcers[94]. Postoperative diet recommendations include clear liquids for the first two weeks, with a transition to a high-protein, low-fat, soft diet for the following two weeks and concurrent vitamin supplementation[94,104]. Given the extreme weight loss associated with the SASI, lifelong nutritional counseling and dietary monitoring are important to support sustained outcomes and prevent nutritional deficiencies. Several studies have shown that a comprehensive multivitamin and mineral regimen, including vitamins B12 and D3, is commonly prescribed after SASI to support nutritional health and prevent deficiencies[94,98,104]. Other studies, however, indicate that nearly 93% of patients tend to taper off or completely stop their supplements after 6 months[98]. Medications for obesity-related conditions must be adequately monitored and tapered off as needed. Patients with diabetes must be closely monitored during the immediate postoperative period, as many can discontinue insulin or oral hypoglycemics within a few days after surgery[92].

Early detection and prevention of complications

Prevention and monitoring strategies for complications following the SASI procedure are inconsistently reported across the literature and often vary in their recommendations, reflecting a lack of standardized postoperative protocols. Prophylactic anticoagulation is recommended for 2 weeks following surgery[94,104]. Post-operative PPIs for 3 to 4 months can be given to prevent marginal ulcers and GERD-related complications[94,103]. Nutrient supplementation, dietary monitoring, regular medical follow-ups, and continued medication adherence are consistent suggestions provided across various studies. Comorbidity monitoring via laboratory testing, imaging studies to test for potential complications, and weight monitoring are all important preventative and proactive measures to track a patient’s progress following SASI. When long-term complications do arise and are refractory to conservative management, revisional procedures might be necessary. Aghajani et al. reported the need for anastomotic revisions in cases of stenosis and stomal ulcers and for bypass reversal in cases of severe protein-energy malnutrition[94,107]. As outcomes have also been closely tied to surgical technique, especially bypass length, an MBS consensus meeting has recommended constructing the GI anastomosis at a fixed distance (approximately 300 cm) from the ileocecal valve to help prevent further complications[109].

PROCEDURE CHOICE

Selection of the optimal procedure requires consideration of multiple patient-, procedure-, and outcome-related factors, as part of the shared decision-making process and multidisciplinary assessment. Patient characteristics such as BMI, obesity-related medical conditions and preferences should be taken into account, as each procedure produces different weight loss outcomes and comorbidity remission rates. Among the four procedures discussed above, the literature has shown that, on average, SASI seems to produce the most excess weight loss at 4-5 years of follow-up, as shown in Table 1. While it shows some advantages in that regard, the highest remission rates of obesity-related medical conditions can be seen after OAGB, with rates above 90% for all conditions. Of note, OAGB could result in diabetes remission rates of up to 94%, which is followed by 93% in SASI, 90% in SADI-S and 86% in SG-TB. Patient preferences, as well as provider input, thus come into play to decide if either outcome holds priority or whether an adequate balance between both is desired. Nevertheless, surgical factors such as technique, anticipated intra- and post-operative complications are also crucial in determining which procedure would result in the most benefits while minimizing risks. While SASI has been shown to result in lower rates of overall complications, including but not limited to marginal ulcers, hernias, stenosis and gallstones, as well as superior weight loss outcomes, it does come at the expense of severe protein-energy malnutrition, necessitating consistent follow-up and compliance with postoperative regimens. Other procedures, such as OAGB, SADI-S and SG-TB, have so far shown deficiencies in micronutrients that can be adequately managed with tailored supplementation.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Owing to the hypoabsorptive nature of the above-mentioned procedures, nutritional deficiencies, severe protein-energy malnutrition and malabsorption are not uncommon postoperative complications. As such, it remains important to consider how such outcomes could be best avoided. For instance, Hess et al., the surgeons who developed the BPD/DS, encouraged the adoption of a CC measuring 10% and an alimentary limb (AL) measuring 40% of the total small bowel length. Such measurements could be used in determining the location of the anastomosis in BPD/DS rather than relying on fixed lengths[44,45]. A ratio of CC or AL to total small bowel length rather than a fixed measurement could similarly be adopted in the above procedures; this could allow adequate but slight variations suitable for each patient, depending on their anatomical and bowel configurations, and tailored to their nutritional needs. However, more research is needed in that area.

CONCLUSION

MBS has grown over the years to encompass newer techniques in the management of obesity and its associated medical conditions. OAGB, SADI-S, SG-TB and SASI prove to be effective and safe alternatives; they have been designed with an aim to offer advantageous weight loss outcomes, tackle nutrient hypoabsorption issues, and serve as successful revisional surgeries when indicated. Consideration of CC lengths, in relation to total AL length, also seems to show promise or suggestions in standardizing those newer procedures and ensuring optimal patient outcomes. Although the existing evidence supports these findings, long-term data remain limited for some procedures, such as SG-TB and SASI, which have yet to be fully endorsed by the ASMBS. Larger and longer-term studies are thus needed to evaluate definitive outcomes, standardize procedural approaches, and develop GRADE-based pre- and postoperative guidelines that would optimize patient outcomes.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to data research, drafted the work, reviewed it critically, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work: El Ghazal N, Marrero K

Made substantial contributions to data research, drafted the work, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work: Gajjar A, Puvvadi S

Reviewed the work critically before submission, provided final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work: Kermansaravi M

Made substantial contributions to the conception of the manuscript, reviewed the work critically before submission, provided final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work: Ghanem OM, Robertson AG

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. [Last accessed on 6 Jan 2026].

2. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766-81.

3. Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. State-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2440-50.

4. Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1822-32.

5. Clapp B, Ponce J, Corbett J, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery 2022 estimate of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2024;20:425-31.

6. Monteiro Delgado L, Fabretina de Souza V, Fontel Pompeu B, et al. Long-term outcomes in sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes Surg. 2025;35:3246-57.

7. Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, et al.; Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013;310:2416-25.

8. Clapp B, Wynn M, Martyn C, Foster C, O’Dell M, Tyroch A. Long term (7 or more years) outcomes of the sleeve gastrectomy: a meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:741-7.

9. Lessing Y, Pencovich N, Lahat G, Klausner JM, Abu-Abeid S, Meron Eldar S. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for diabetics - 5-year outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1658-63.

10. Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutrition, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of Patients Undergoing Bariatric Procedures - 2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, the Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists - executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2019;25:1346-59.

11. Aizpuru M, Glasgow AE, Salame M, et al. Bariatric surgery outcomes in patients with bipolar or schizoaffective disorders. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2023;19:1085-92.

12. Sánchez-Pernaute A, Herrera MAR, Pérez-Aguirre ME, et al. Single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S). One to three-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1720-6.

13. De Luca M, Tie T, Ooi G, et al. Mini gastric bypass-one anastomosis gastric bypass (MGB-OAGB)-IFSO Position Statement. Obes Surg. 2018;28:1188-206.

14. Perrotta G, Bocchinfuso S, Jawhar N, et al. Novel surgical interventions for the treatment of obesity. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5279.

15. Gagner M. Hypoabsorption not malabsorption, hypoabsorptive surgery and not malabsorptive surgery. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2783-4.

16. Poghosyan T, Krivan S, Baratte C. Bile or acid reflux post one-anastomosis gastric bypass: what must we do? Still an unsolved enigma. J Clin Med. 2022;11:3346.

17. Andalib A, Bouchard P, Alamri H, Bougie A, Demyttenaere S, Court O. Single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S): short-term outcomes from a prospective cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17:414-24.

18. Enochs P, Bull J, Surve A, et al. Comparative analysis of the single-anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) to established bariatric procedures: an assessment of 2-year postoperative data illustrating weight loss, type 2 diabetes, and nutritional status in a single US center. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16:24-33.

19. Kallies K, Rogers AM; American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clinical Issues Committee. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery updated statement on single-anastomosis duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16:825-30.

21. Arakkakunnel J, Grover K. One anastomosis gastric bypass and mini gastric bypass. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK608008/. [Last accessed on 6 Jan 2026].

22. Ghiassi S, Nimeri A, Aleassa EM, Grover BT, Eisenberg D, Carter J; American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clinical Issues Committee. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery position statement on one-anastomosis gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2024;20:319-35.

23. Salminen P, Kow L, Aminian A, et al.; IFSO Experts Panel. IFSO consensus on definitions and clinical practice guidelines for obesity management - an International Delphi study. Obes Surg. 2024;34:30-42.

24. Robert M, Espalieu P, Pelascini E, et al. Efficacy and safety of one anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for obesity (YOMEGA): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1299-309.

25. Lazzati A, Poghosyan T, Touati M, Collet D, Gronnier C. Risk of esophageal and gastric cancer after bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:264-71.

26. Gallucci P, Marincola G, Pennestrì F, et al. One-anastomosis gastric bypass (OABG) vs. single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass (SADI) as revisional procedure following sleeve gastrectomy: results of a multicenter study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:128.

27. Neuberg M, Blanchet MC, Gignoux B, Frering V. Long-term outcomes after one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2020;30:1379-84.

28. Carandina S, Soprani A, Zulian V, Cady J. Long-term results of one anastomosis gastric bypass: a single center experience with a minimum follow-up of 10 years. Obes Surg. 2021;31:3468-75.

29. Carbajo MA, Luque-de-León E, Jiménez JM, Ortiz-de-Solórzano J, Pérez-Miranda M, Castro-Alija MJ. Laparoscopic one-anastomosis gastric bypass: technique, results, and long-term follow-up in 1200 patients. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1153-67.

30. Almuhanna M, Soong TC, Lee WJ, Chen JC, Wu CC, Lee YC. Twenty years’ experience of laparoscopic 1-anastomosis gastric bypass: surgical risk and long-term results. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17:968-75.

31. Tarhini A, Rives-Lange C, Jannot AS, et al. One-anastomosis gastric bypass revision for gastroesophageal reflux disease: long versus short biliopancreatic limb Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2022;32:970-8.

32. Parikh M, Eisenberg D, Johnson J, El-Chaar M; American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clinical Issues Committee. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery review of the literature on one-anastomosis gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:1088-92.

33. Solouki A, Kermansaravi M, Davarpanah Jazi AH, Kabir A, Farsani TM, Pazouki A. One-anastomosis gastric bypass as an alternative procedure of choice in morbidly obese patients. J Res Med Sci. 2018;23:84.

34. Magouliotis DE, Tasiopoulou VS, Tzovaras G. One anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: an updated meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;29:2721-30.

35. Ganipisetti VM, Naha S. Bariatric surgery malnutrition complications. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK592383/. [Last accessed on 6 Jan 2026].

36. Syn NL, Lee PC, Kovalik JP, et al. Associations of bariatric interventions with micronutrient and endocrine disturbances. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e205123.

37. Wei JH, Lee WJ, Chong K, et al. High incidence of secondary hyperparathyroidism in bariatric patients: comparing different procedures. Obes Surg. 2018;28:798-804.

38. Benalcazar DA, Cascella M. Obesity surgery preoperative assessment and preparation. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594256/.[Last accessed on 6 Jan 2026].

39. Baksi A, Kamtam DNH, Aggarwal S, Ahuja V, Kashyap L, Shende DR. Should surveillance endoscopy be routine after one anastomosis gastric bypass to detect marginal ulcers: initial outcomes in a tertiary referral centre. Obes Surg. 2020;30:4974-80.

40. Brown WA, Johari Halim Shah Y, Balalis G, et al. IFSO Position Statement on the role of esophago-gastro-duodenal endoscopy prior to and after bariatric and metabolic surgery procedures. Obes Surg. 2020;30:3135-53.

41. Heidelbaugh JJ. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of vitamin and mineral deficiency: evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013;4:125-33.

42. Mostafapour E, Shahsavan M, Shahmiri SS, Jawhar N, Ghanem OM, Kermansaravi M. Prevention of malnutrition after one anastomosis gastric bypass: value of the common channel limb length. BMC Surg. 2024;24:156.

43. Cottam D, Cottam S, Surve A. Single-anastomosis duodenal ileostomy with sleeve gastrectomy “continued innovation of the duodenal switch”. Surg Clin North Am. 2021;101:189-98.

44. Hess DS, Hess DW, Oakley RS. The biliopancreatic diversion with the duodenal switch: results beyond 10 years. Obes Surg. 2005;15:408-16.

46. Salame M, Teixeira AF, Lind R, et al. Marginal ulcer and dumping syndrome in patients after duodenal switch: a multi-centered study. J Clin Med. 2023;12:5600.

47. Tomey D, Hage K, Jawhar N, et al. The rise of the duodenal switch: a narrative review. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg. 2024;9:37.

48. Yashkov Y, Bordan N, Torres A, Malykhina A, Bekuzarov D. SADI-S 250 vs Roux-en-Y duodenal switch (RY-DS): results of 5-year observational study. Obes Surg. 2021;31:570-9.

49. Surve A, Cottam D, Medlin W, et al. Long-term outcomes of primary single-anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S). Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16:1638-46.

50. Hu L, Wang L, Li S, et al. Evaluation study of single-anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy in the treatment of Chinese obese patients based on efficacy and nutrition. Sci Rep. 2024;14:6522.

51. Verhoeff K, Mocanu V, Jogiat U, et al. Patient selection and 30-day outcomes of SADI-S compared to RYGB: a retrospective cohort study of 47,375 patients. Obes Surg. 2022;32:1-8.

52. Palmieri L, Pennestrì F, Raffaelli M. SADI-S, state of the art. Indications and results in 2024: a systematic review of literature. Updates Surg. 2025;77:2037-50.

53. Verhoeff K, Mocanu V, Zalasky A, et al. Evaluation of metabolic outcomes following SADI-S: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2022;32:1049-63.

54. Sánchez-Pernaute A, Rubio MÁ, Pérez Aguirre E, Barabash A, Cabrerizo L, Torres A. Single-anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy: metabolic improvement and weight loss in first 100 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:731-5.

55. Shoar S, Poliakin L, Rubenstein R, Saber AA. Single anastomosis duodeno-ileal switch (SADIS): a systematic review of efficacy and safety. Obes Surg. 2018;28:104-13.

56. Topart P, Becouarn G. The single anastomosis duodenal switch modifications: a review of the current literature on outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1306-12.

57. Ponce de Leon-Ballesteros G, Romero-Velez G, Higa K, et al. Single anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy with sleeve gastrectomy/single anastomosis duodenal switch (SADI-S/SADS) IFSO Position Statement-update 2023. Obes Surg. 2024;34:3639-85.

58. Sánchez-Pernaute A, Herrera MÁR, Ferré NP, et al. Long-term results of single-anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S). Obes Surg. 2022;32:682-9.

59. Cottam A, Cottam D, Roslin M, et al. A matched cohort analysis of sleeve gastrectomy with and without 300 cm loop duodenal switch with 18-month follow-up. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2363-9.

60. Surve A, Cottam D, Belnap L, Richards C, Medlin W. Long-term (> 6 years) outcomes of duodenal switch (DS) versus single-anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S): a matched cohort study. Obes Surg. 2021;31:5117-26.

61. Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, et al.; Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741-52.

62. Pennestrì F, Sessa L, Prioli F, et al. Single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S): experience from a high-bariatric volume center. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:1851-62.

63. Spinos D, Skarentzos K, Esagian SM, Seymour KA, Economopoulos KP. The effectiveness of single-anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy/one anastomosis duodenal switch (SADI-S/OADS): an updated systematic review. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1790-800.

64. Gross A, Gentle C, Wehrle CJ, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) prescribing after gastrojejunostomy: a preventable cause of morbidity. Surgery. 2025;179:108806.

65. Surve A, Cottam D, Sanchez-Pernaute A, et al. The incidence of complications associated with loop duodeno-ileostomy after single-anastomosis duodenal switch procedures among 1328 patients: a multicenter experience. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:594-601.

66. Cirera A, Vilallonga R, Ruiz de Gordejuela AG, et al. Complications after single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) a retrospective review of cases in a high-volume European center. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:e1-2.

67. Martinino A, Bhandari M, Abouelazayem M, Abdellatif A, Koshy RM, Mahawar K. Perforated marginal ulcer after gastric bypass for obesity: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18:1168-75.

68. Portela R, Marrerro K, Vahibe A, et al. Bile reflux after single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve (SADI-S): a meta-analysis of 2,029 patients. Obes Surg. 2022;32:1516-22.

69. Gebellí JP, Lazzara C, de Gordejuela AGR, et al. Duodenal switch vs. single-anastomosis duodenal switch (SADI-S) for the treatment of grade IV obesity: 5-year outcomes of a multicenter prospective cohort comparative study. Obes Surg. 2022;32:3839-46.

70. Bashah M, Aleter A, Baazaoui J, El-Menyar A, Torres A, Salama A. Single anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy (SADI-S) versus one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB-MGB) as revisional procedures for patients with weight recidivism after sleeve gastrectomy: a comparative analysis of efficacy and outcomes. Obes Surg. 2020;30:4715-23.

71. Esparham A, Roohi S, Ahmadyar S, et al. The efficacy and safety of laparoscopic single-anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) in mid- and long-term follow-up: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2023;33:4070-9.

72. Thorell A, MacCormick AD, Awad S, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in bariatric surgery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations. World J Surg. 2016;40:2065-83.

73. Gan TJ, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, et al.; Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia. Consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:85-113.

74. Harker MJR, Heusschen L, Monpellier VM, et al. Five year outcomes of primary and secondary single-anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S). Obes Surg. 2025;35:2160-73.

75. Haddad A, Kow L, Herrera MF, et al. Innovative bariatric procedures and ethics in bariatric surgery: the IFSO Position Statement. Obes Surg. 2022;32:3217-30.

76. Santoro S, Malzoni CE, Velhote MC, et al. Digestive adaptation with intestinal reserve: a neuroendocrine-based operation for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1371-9.

77. Zhao S, Li R, Zhou J, Sun Q, Wang W, Wang D. Sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition: a review of the literature. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;17:451-9.

78. Taskin HE, Al M. Longitudinal outcomes through 4 years after sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition. Bariatr Surg Pract Patient Care. 2022;17:225-36.

79. Karaca FC. Effects of sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition on glycemic variables, lipid profile, liver enzymes, and nutritional status in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Obes Surg. 2020;30:1437-45.

80. Al M, Taskin HE. Sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition in a series of 883 patients with mild obesity: early effectiveness and safety outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:2631-42.

81. Azevedo FR, Santoro S, Correa-Giannella ML, et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial of the metabolic effects of sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition. Obes Surg. 2018;28:3012-9.

82. Liu P, Widjaja J, Dolo PR, et al. Comparing the anti-diabetic effect of sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition against sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass using a diabetic rodent model. Obes Surg. 2021;31:2203-10.

83. Baratte C, Willemetz A, Ribeiro-Parenti L, et al. Analysis of the efficacy and the long-term metabolic and nutritional status of sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition compared to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in obese rats. Obes Surg. 2023;33:1121-32.

84. Santoro S, Castro LC, Velhote MC, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition: a potent intervention for metabolic syndrome and obesity. Ann Surg. 2012;256:104-10.

85. Calisir A, Ece I, Yilmaz H, et al. The mid-term effects of transit bipartition with sleeve gastrectomy on glycemic control, weight loss, and nutritional status in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective analysis of a 3-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2021;31:4724-33.

86. Topart P, Becouarn G, Finel JB. Is transit bipartition a better alternative to biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch for superobesity? Comparison of the early results of both procedures. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16:497-502.

87. Topart P, Becouarn G, Finel JB. Comparison of 2-year results of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and transit bipartition with sleeve gastrectomy for superobesity. Obes Surg. 2020;30:3402-7.

88. Clyde DR, Adib R, Baig S, et al. An international Delphi consensus on patient preparation for metabolic and bariatric surgery. Clin Obes. 2025;15:e12722.

89. Reiser M, Christogianni V, Nehls F, Dukovska R, de la Cruz M, Büsing M. Short-term results of transit bipartition to promote weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg Open. 2021;2:e102.

90. Ribeiro R, Viveiros O, Taranu V, Rossoni C. One anastomosis transit bipartition (OATB): rational and mid-term outcomes. Obes Surg. 2024;34:371-81.

91. Santoro S, Mota FC, de Aquino CGG, de Godoy EP. Common channel length and implications to the weight loss. Updates Surg. 2025;77:2145-50.

92. Mahdy T, Al Wahedi A, Schou C. Efficacy of single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass for type-2 diabetic morbid obese patients: gastric bipartition, a novel metabolic surgery procedure: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2016;34:28-34.

93. Oliveira CR, Santos-Sousa H, Costa MP, et al. Efficiency and safety of single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in the treatment of obesity and associated comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:221.

94. Aghajani E, Schou C, Gislason H, Nergaard BJ. Mid-term outcomes after single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in treatment of morbid obesity. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:6220-7.

95. Tarnowski W, Barski K, Jaworski P, et al. Single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass (SASI): a single-center initial report. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2022;17:365-71.

96. Attia N, Ben Hadj Khlifa M, Ben Fadhel N. The single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass: a review of the current literature on outcomes and statistical results. Obes Med. 2021;27:100370.

97. Khalaf M, Hamed H. Single-anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass: hopes and concerns after a two-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2021;31:667-74.

98. Salama TMS, Sabry K, Ghamrini YE. Single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass: new step in the evolution of bariatric surgeries. J Invest Surg. 2017;30:291-6.

99. Dowgiałło-Gornowicz N, Waczyński K, Waczyńska K, Lech P. Single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass as a primary and revisional procedure: a single-centre experience. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2023;18:510-5.

100. Hosseini SV, Moeinvaziri N, Medhati P, et al. Optimal length of biliopancreatic limb in single anastomosis sleeve gastrointestinal bypass for treatment of severe obesity: efficacy and concerns. Obes Surg. 2022;32:2582-90.

101. Sewefy AM, Atyia AM, Mohammed MM, Kayed TH, Hamza HM. Single anastomosis sleeve jejunal (SAS-J) bypass as a treatment for morbid obesity, technique and review of 1986 cases and 6 years follow-up. Retrospective cohort. Int J Surg. 2022;102:106662.

102. Mahdy T, Gado W, Alwahidi A, Schou C, Emile SH. Sleeve gastrectomy, one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), and single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in treatment of morbid obesity: a retrospective cohort study. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1579-89.

103. El-mahdy HM, Abd El-monem AA, Saied AEFM, El-dahshan TA. The metabolic outcome of single anastomosis sleeve ileal operation. Al-Azhar Med J. 2020;49:1629-38.

104. Kandel MM, Hassan M, Ali RF. One year follow-up of laparoscopic single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass in super-morbidly obese patients. Med Update. 2023;14:37-62.

105. Emile SH, Mahdy T, Schou C, Kramer M, Shikora S. Systematic review of the outcome of single-anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in treatment of morbid obesity with proportion meta-analysis of improvement in diabetes mellitus. Int J Surg. 2021;92:106024.

106. Kamal A, El Azawy M, Hassan TAA. Unpredictable malnutrition and short-term outcomes after single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in obese patients. J Obes. 2023;2023:5582940.

107. Kavlakoglu B, Senol M. IBC-Oxford University2023_BJSPoster_14. Short-term outcomes of single-anastomosis sleeve-ileal bypass (SASI). Br J Surg. 2023;110:znad382.041.

108. Sewefy AM, Abdelzaher MA, Sabry K, et al. Single anastomosis sleeve jejunal (SAS-J) bypass vs single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass, prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Surg. 2025;111:5268-79.

Cite This Article