Is robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) a valid alternative to open pancreaticoduodenectomy?

Abstract

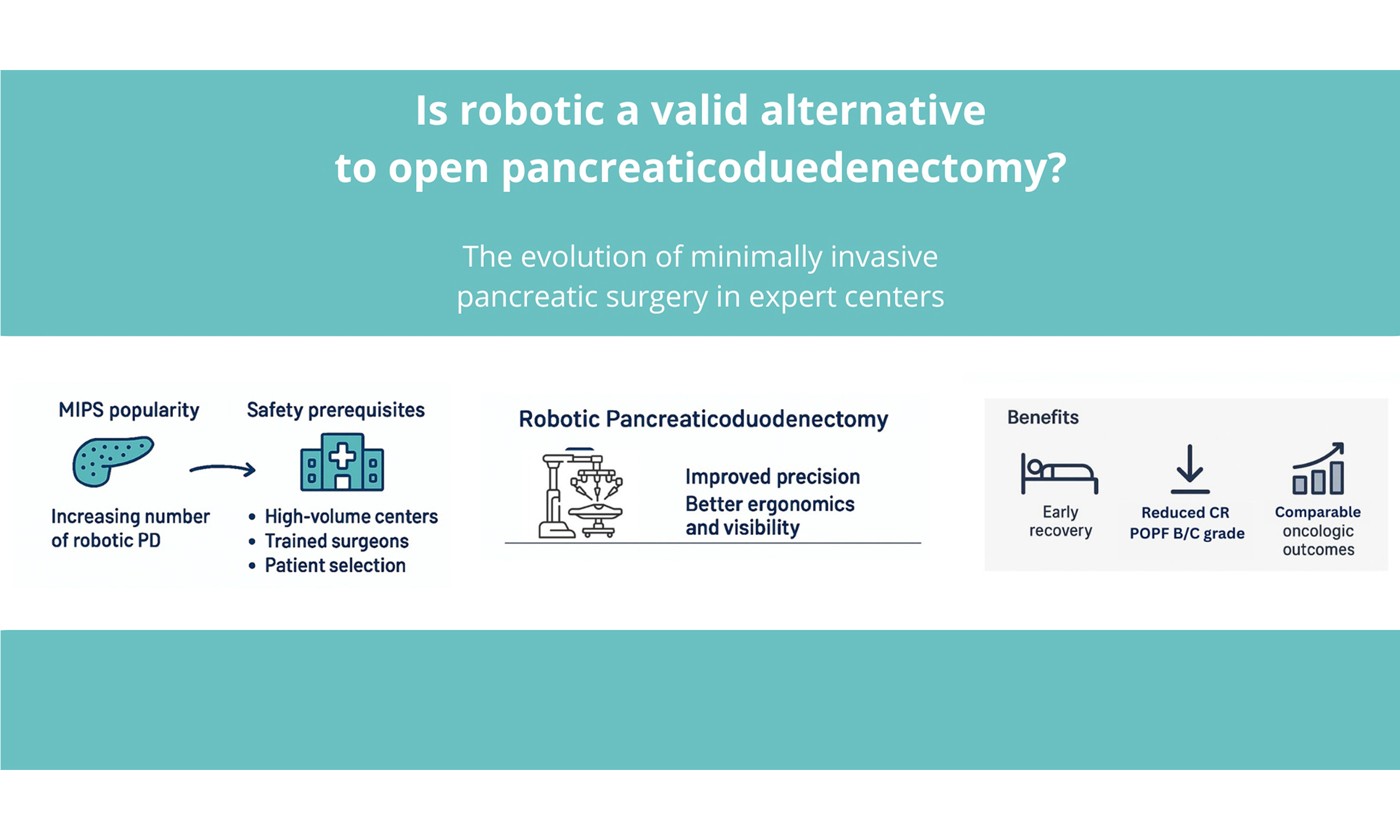

In recent years, minimally invasive pancreatic surgery (MIPS) has become increasingly popular and is now considered an important part of pancreatic surgery practice. Nevertheless, MIPS is feasible and safe only in high-volume centres, with good training of surgeons and good patient selection. This commentary aims to focus on the role of MIPS, in particular robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy, highlighting the advantages of the robotic approach in terms of early postoperative recovery, reduced postoperative complications, and comparable oncological outcomes.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the role of minimally invasive pancreatic surgery (MIPS) has become increasingly popular, now representing an important part of pancreatic surgery practice. While the role of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has been demonstrated and standardised for distal pancreatectomy[1], the role of minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is nowadays still debated, and this approach is reserved only for selected patients in highly specialised centres.

DISCUSSION

The first laparoscopic PD (LAP-PD) was performed in 1994 by Gagner et al.[2]. However, despite the increasing adoption of minimally invasive approaches in pancreatic surgery, LAP-PD still represents only a minority of pancreatic procedures. As a result, open pancreatoduodenectomy (OPD) remains the gold standard and the preferred technique in most centres, particularly for vascular and multivisceral resections. One of the main reasons for this reluctance compared to LAP-PD was the difficulty associated with this technique, characterised by a steep learning curve and requiring advanced skills in laparoscopic dissection and reconstruction. Lately, with the advent of robotic techniques, the number of PD procedures performed using a minimally invasive approach has increased. The robotic technique offers several advantages over laparoscopy, including improved precision through three-dimensional visualisation, seven degrees of motion, and elimination of hand tremors. On the other hand, the robotic approach involves high service and maintenance costs. Over the years, various randomised studies[3-5] have compared the outcomes of OPD and LAP-PD, with contrasting results. Some studies reported shorter hospital stays but longer operative times in the laparoscopic group, while others revealed higher complication rates with the laparoscopic approach [Table 1].

Summary of RCTs comparing laparoscopic vs. open partial pancreatoduodenectomy

| Studies | Type RCT | N | Hospital stay | POPF B/C | Mortality | Year published |

| PLOT | Monocentric | 64 | 7 vs. 13 days (P: 0.001) | 6% vs. 12% (P: 0.311) | 1 vs. 1 (P: -) | 2017 |

| PADULAP | Monocentric | 66 | 13.5 vs. 17 days (P: 0.024) | 12.5% vs. 27.6% (P: 0.14) | 0% vs. 6.9% (P: 0.29) | 2018 |

| LEOPARD-2 | Multicentric | 105 | 12 vs. 11 days (P: 0.86) | 28% vs. 24% (P: 0.69) | 10% vs. 2% (P: 0.20) | 2019 |

Following the publication of the laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2) trial results[4], which showed that LAP-PD was associated with a higher rate of complication-related mortality compared to OPD, with no significant difference in time to functional recovery between the two groups, interest in LAP-PD slowed. Conversely, the interest in robotic PD (RPD) increased, leading to the publication of several trials.

The minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic and peri-ampullary neoplasm (DIPLOMA-2) trial[6], an international randomised controlled study, was conducted in 14 high-volume pancreatic centres in Europe with a minimum annual volume of 30 minimally invasive pancreatico duodenectomy (MIPD) and 30 OPD. A total of 288 patients with an indication for elective PD for pre-malignant and malignant disease, eligible for both open and minimally invasive approaches, were randomly allocated for MIPD or OPD in a 2:1 ratio. Contrary to the LEOPARD-2, the DIPLOMA-2 trial demonstrated the non-inferiority of MIPD vs. OPD for overall complications and the superiority of MIPD regarding time to functional recovery[7]. This trial underlined the tight relationship between the outcomes of the patients and the high-volume centres. Moreover, the participating surgeons were required to have a minimum of 60 MIPDs and 60 OPDs of experience to participate in the trial.

At the same time, at the University Hospital Heidelberg in Germany, the robotic versus open partial pancreatoduodenectomy (EUROPA) trial was conducted[8].

The EUROPA trial confirmed that RPD was as safe as open surgery [90-day comprehensive complication index (CCI) of 34 vs. 36, respectively, P = 0.713]. However, this study did not demonstrate the usual benefits of minimally invasive approaches, such as reduced blood loss and shorter hospital stays.

In the same year (2024), Liu et al. published a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted at three high-volume hospitals in China, showing that the postoperative length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in the RPD vs. the OPD group (11 vs. 13.5 days; median difference of 2 days; P = 0.029), as were times to functional recovery in robotic group (e.g., removal of nasogastric tube and off-bed activities: 2 vs. 3 days; P < 0.001)[9].

These results were confirmed in the PORTAL trial[10], which showed a shorter time to functional recovery (11.3 vs. 15.4, P: 0.029), less blood loss (P: 0.053), and lower rates of postoperative pancreatic failure (POPF) grade B/C (8.9% vs. 20.2%, P: 0.014) in the robotic group.

Therefore, almost all trials reported in the literature have affirmed the non-inferiority of RPD compared to OPD, supporting the use of MIS also for PD [Table 2].

Summary of RCTs: robotic vs. open partial pancreatoduodenectomy

| Studies | Type RCT | N Total | Hospital stay | POPF B/C | Mortality | Year published |

| EUROPA | Monocentre | 81 | 17 vs. 13 days (P: 0.177) | 38% vs. 21% (P: 0.148) | 0% vs. 9.1% (NS) | 2024 |

| Liu | Multicentre | 164 | 11 vs. 14 days (P: 0.029) | 14% vs. 13% (P: 0.84) | 1% vs. 1% (P: 1) | 2024 |

| DIPLOMA-2 | Multicentre | 288 | 7 vs. 8 days (P: 0.02) | 23% vs. 36% (P: 0.03) | 4,6% vs. 2% (P: 0.26) | 2023 |

| PORTAL | Multicentre | 237 | 11 vs. 15 days (P: 0.029) | 9% vs. 20% (P: 0.014) | NA | 2021 |

Almost all the selected studies consider surgeries performed by trained surgeons, emphasising that the learning curve is essential for performing RPD. As reported by Jones et al., RPD was feasible after 30-45 procedures, with proficiency achieved after 90 procedures. Moreover, the number of procedures performed was inversely correlated with major morbidity[11].

Furthermore, the phase 3 studies mentioned above demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of clinically relevant (grade B/C) postoperative pancreatic fistula (CR-POPF)[7,10]. This finding was corroborated by subsequent studies, which also indicated that RPD is associated with a lower incidence of CR-POPF[11-13].

Specifically, Fuji et al., in their retrospective study involving 204 patients, demonstrated that RPD was significantly linked to a lower incidence of CR-POPF in high-risk anastomoses[14].

The reason for the reduced incidence of CR-POPF in RPD still has to be assessed. However, it may be related to the technical advantages of the robotic platform. The robotic system provides enhanced magnified three-dimensional visualisation of small pancreatic ducts and wristed instruments can offer superior dexterity and manoeuvrability in a stable operating field with tremor filtration. These features facilitate more precise suturing during pancreatic anastomosis, potentially improving the quality of reconstruction, reducing the pancreatic tissue manipulation and thereby reducing the risk of CR-POPF.

Moreover, RPD has recently been demonstrated to be a suitable approach even for patients with locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma following neoadjuvant treatment (NAT) as shown in the retrospective analysis by Kim et al., which also reported comparable survival outcomes to OPD, along with shorter postoperative hospital stays and a lower incidence of postoperative complications[15,16].

On the other hand, one of the main factors currently limiting the adoption of robotic techniques is the high cost associated with this technology. Indeed, as reported in the EUROPA trial[8], RPD was more expensive than OPD in terms of both procedure-related and total hospital costs up to postoperative day 90. However, this finding has not been confirmed by other studies. In fact, as reported in the DIPLOMA 2 trial[7], the reduction of postoperative complications and hospital stay can offset the costs associated with the robotic platform, making the robotic approach a viable and affordable alternative to OPD in high-volume centres. This finding was also confirmed by Wakabayashi et al., who supported the feasibility and potential advantages of adopting RPD for the management of periampullary neoplasms in clinical practice[12].

In conclusion, in high-volume centres with experienced and well-trained surgeons, RPD can be considered a viable alternative to OPD, offering reduced intraoperative blood loss, fewer postoperative complications, shorter hospital stays, and a lower incidence of CR-POPF. Nevertheless, robust long-term oncological data are still lacking, and further studies with extended follow-up are required to confirm these results. Emerging evidence also indicates a potential benefit in terms of postoperative quality of life and earlier return to daily activities, although these areas remain under-investigated. Furthermore, the robotic platform may play a significant role in surgical training, offering improved ergonomics, simulation modules, and support for complex reconstructions. Looking forward, the integration of ongoing RCTs, international registries, and new technologies, including next-generation robotic systems and artificial intelligence-based intraoperative support, will be crucial to fully establish the role of RPD in standard surgical practice.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Data collection, review analysis, and manuscript writing: Belli A, Cutolo C

Study concept, design, and manuscript review: Belli A, Cutolo C, Izzo F, Valeriani M

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Izzo F

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials are available online, corresponding to the cited references.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Belli A is both an Editorial Board Member of the journal Mini-invasive Surgery and a Guest Editor for the Special Issue Pancreatic Surgery: From Minimally Invasive Techniques to Robotic Assistance. Belli A was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Korrel M, Jones LR, van Hilst J, et al.; European Consortium on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery (E-MIPS). Minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy for resectable pancreatic cancer (DIPLOMA): an international randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023;31:100673.

2. Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:408-10.

3. Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br J Surg. 2017;104:1443-50.

4. van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Bosscha K, et al.; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): a multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:199-207.

5. Poves I, Burdío F, Morató O, et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and open approach for pancreatoduodenectomy: the PADULAP randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268:731-9.

6. de Graaf N, Emmen AMLH, Ramera M, et al.; European Consortium on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery (E-MIPS). Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic and peri-ampullary neoplasm (DIPLOMA-2): study protocol for an international multicenter patient-blinded randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2023;24:665.

7. de Graaf N, Emmen A, Ramera M, et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for resectable neoplasm (diploma-2). HPB. 2025;27:S1-2.

8. Klotz R, Mihaljevic AL, Kulu Y, et al. Robotic versus open partial pancreatoduodenectomy (EUROPA): a randomised controlled stage 2b trial. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;39:100864.

9. Liu Q, Li M, Gao Y, et al. Effect of robotic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy on postoperative length of hospital stay and complications for pancreatic head or periampullary tumours: a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:428-37.

10. Jin J, Shi Y, Chen M, et al. Robotic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic and periampullary tumors (PORTAL): a study protocol for a multicenter phase III non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22:954.

11. Jones LR, Zwart MJW, de Graaf N, et al.; International Consortium on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery (I-MIPS). Learning curve stratified outcomes after robotic pancreatoduodenectomy: international multicenter experience. Surgery. 2024;176:1721-9.

12. Wakabayashi T, Gaudenzi F, Nie Y, et al. Reduced pancreatic fistula rates and comprehensive cost analysis of robotic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 2025;39:3921-9.

13. Li R, Zhang X, Chen W, et al. Robotic pancreatoduodenectomy reduces grade B pancreatic fistula in patients with a small main pancreatic duct: a propensity score-matched study compared to laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Med. 2025;57:2527357.

14. Fuji T, Takagi K, Umeda Y, et al. Impact of robotic surgery on postoperative pancreatic fistula for high-risk pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy. Dig Surg. 2025;42:49-58.

15. Kim HE, Jung HS, Han Y, et al. Evaluation of feasibility and clinical outcomes of robot-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy after neoadjuvant treatment for patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a retrospective propensity score-matched cohort study. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2025;109:61-70.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].