Sutureless off-clamp robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: a single-surgeon case series with insights into technique and complications

Abstract

Aim: Previous literature has evaluated the feasibility and safety of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) performed entirely sutureless and off-clamp. The aim of the present study was to report a series of consecutive, unselected patients with renal masses of intermediate complexity who underwent sutureless off-clamp robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (sl-oc RAPN) by a single surgeon, focusing on surgical strategies, technique, and safety.

Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted on 29 patients between January 2022 and September 2024. Preoperative clinical characteristics, intraoperative data, and postoperative outcomes were examined, with particular attention to adverse events classified according to the Clavien-Dindo system. Additionally, hemoglobin, serum creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were analyzed at discharge and at three months postoperatively.

Results: The median patient age was 60 years. All tumors were classified as T1a or T1b according to the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) system. The median tumor diameter was 30 mm (range: 28-45), and the median PADUA score was 8 (range: 7-8). The median operative time (OT) was 135 min (range: 110/160), and the median estimated blood loss (EBL) was 100 mL (range: 50-100). Serum creatinine and eGFR at discharge and three months postoperatively showed no statistically significant changes (P > 0.05). Three patients (10%) experienced Clavien-Dindo ≥ 3 complications: two developed urine leakage requiring ureteral stent placement, and one experienced postoperative bleeding requiring blood transfusions.

Conclusion: Although limited by a small sample size and the absence of a control group, and with urinary fistula as a potential limitation of the technique, sl-oc RAPN appears effective for treating intermediate-complexity renal tumors. It maintains oncological outcomes, minimizes complications, and preserves renal function.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Partial nephrectomy (PN) is the gold standard treatment for patients with localized T1 renal cell carcinoma (RCC), providing effective oncological control while ensuring perioperative safety and preservation of renal function[1,2].

Although the optimal surgical approach remains debated, the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines suggest that robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) may offer certain advantages over open and laparoscopic techniques[3-5].

Beyond the choice of approach, two key considerations in RAPN are particularly important: management of the renal hilum prior to tumor enucleation (arterial clamping versus off-clamp) and reconstruction of the renal parenchyma after tumor removal (renorrhaphy versus sutureless technique).

Renal ischemia during surgery is generally regarded as the main determinant of postoperative renal function. Numerous studies have compared the safety and efficacy of sutureless off-clamp RAPN (sl-oc RAPN) with conventional on-clamp RAPN with renorrhaphy, but the optimal approach remains controversial[6-8].

The aim of this study was to report a series of consecutive, unselected patients with renal masses of intermediate complexity, as defined by the RENAL[9] and PADUA scoring systems[10], who underwent sl-oc RAPN performed by a single surgeon, with a focus on surgical strategies, technique, and safety.

METHODS

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 29 patients who underwent sl-oc RAPN between January 2022 and September 2024. All procedures were performed by a single expert surgeon at San Carlo di Nancy Hospital in Rome, who had previously performed approximately 100 on-clamp and 100 off-clamp robot-assisted partial nephrectomies. The study was conducted following ethical standards and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The local ethics committee (Comitato Etico Lazio 1) did not consider the application on the present clinical evaluation of aggregate/anonymous data from the institutional, routinely gathered record.

Preoperative clinical characteristics and tumor features were collected, including age, sex, body mass index, Charlson Comorbidity Index, tumor size, and renal tumor complexity (assessed using RENAL and PADUA scores based on contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scans). All patients had preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) > 30 mL/min (stage I-III chronic kidney disease).

Intraoperative data were analyzed, including operative time (OT), resection technique, estimated blood loss (EBL), use of hemostatic agents, and intraoperative adverse events (e.g., urinary collecting system violation).

Postoperative outcomes were then evaluated, with particular attention to adverse events classified according to the Clavien-Dindo system[11]. Additional parameters included length of hospitalization, day of first mobilization from bed, and time to return of bowel function (feces and gas). Histology and surgical margins were assessed. Hemoglobin, Serum Creatinine, and eGFR were recorded at discharge and three months postoperatively.

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA software. Categorical variables were summarized as absolute and relative frequencies, while numerical variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Two-sided t-tests were applied for general comparisons, and paired t-tests were used for comparisons of preoperative and postoperative values in the same patients. When the assumption of equal variances was violated, Welch’s correction was applied. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for all main comparisons, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Regarding perioperative preparation and surgical technique, patients received a single intravenous dose of cefazolin (2-3 g, weight-adjusted) prior to surgery. Existing anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications were discontinued, except for cardioaspirin, which was continued, and replaced with low-molecular-weight heparin. Bowel preparation was not routinely performed.

Patients were positioned contralateral to the lesion, and transperitoneal access was obtained using four robotic ports and one or two assistant laparoscopic ports, depending on tumor complexity. Robotic ports were aligned along the midclavicular line, while the assistant ports (12 mm, AirSeal® iFS, Conmed, Largo, FL, USA, and when needed, 5 mm) were placed on the pararectal line approximately 5 cm above the umbilicus. Procedures were performed using the da Vinci Xi surgical system with the ERBE VIO dV generator, employing Hot Shears monopolar curved scissors, fenestrated bipolar forceps, and ProGrasp forceps (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Intra-abdominal pressure was maintained at 12 mmHg during tumor excision. The Toldt’s fascia was incised to expose the Gerota’s fascia. Extensive kidney mobilization was performed in most cases, with the renal hilum identified and prepared in advance.

Tumor excision began with circumferential delineation of tumor margins using monopolar curved scissors in coagulation mode (Swift Coag, effect 3). The tumor was then progressively separated from the renal parenchyma using gentle traction with fenestrated bipolar forceps (Autostop ON, effect 3), which also provided preventive hemostasis of afferent and efferent vessels. Monopolar and bipolar energy were applied as needed prior to vessel incision to maintain visibility and minimize bleeding.

Bleeding control at the tumor bed was generally achieved using monopolar and bipolar energy, supplemented with hemostatic agents. Before applying the hemostatic agent, intra-abdominal pressure was slightly reduced (~ 10 mmHg) to identify active bleeding. Capillary bleeding was controlled using the back of the monopolar scissors, while larger vessel bleeding was managed with fenestrated bipolar forceps. No vascular suturing was performed. The hemostatic agent used was a resorbable oxidized regenerated cellulose sheet (Oxitamp, Assut Europe SpA, Rome, Italy).

The excised tumor was removed using a retrieval bag. The Gerota’s fascia was closed with a running barbed suture (Filbloc 3/0, Assut Europe, Magliano dei Marsi, L’Aquila, Italy). A drain was left in the renal fossa for 24 h in only three cases.

RESULTS

A total of 29 patients who underwent sl-oc RAPN were enrolled in the study. The median age of the patients was 60 years. Patient baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1, and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Of the 29 cases, 26 (90%) presented with a solitary lesion. Tumors were located on the left kidney in 16 cases (55%) and on the right kidney in 13 cases (45 %). All tumors were classified as T1 according to the TNM system, with 23 cases (79%) being T1a and 6 cases (21%) T1b. The median tumor diameter was 30 mm (range: 28-45). The median PADUA score was 8 (range: 7-8), indicating moderate-risk lesions. Three tumors involved the renal hilum, and four caused compression of the urinary collecting system.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Value |

| Age, years | 60 (47-69) |

| Male, n (%) | 21 (72) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25 (24-26) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1 (0-2) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.8 (14,2-15,8) |

| Serum Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.86 (0,76-1) |

| eGFR, mL/min | 85 (72-97) |

Tumor characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

| Diameter, mm | 30 (28-45) |

| Single lesion, n (%) | 26 (90) |

| Left Kidney, n (%) | 16 (55) |

| Right Kidney, n (%) | 13 (45) |

| T1a, n (%) | 23 (79) |

| T1b, n (%) | 6 (21) |

| RENAL score | 7 (6-8) |

| PADUA score | 8 (7-8) |

| Contact surface area, cm2 | 26.9 (19,6-51,8) |

| Cystic lesion, n (%) | 7 (24) |

| Hilar lesion, n (%) | 3 (10) |

| Lesion involving urinary collecting system, n (%) | 4 (14) |

Intraoperative outcomes [Table 3] showed a median OT of 135 min (range: 110/160) and a median EBL of 100 mL (range: 50-100). A drain was placed in the renal fossa in three cases. Surgical procedures included enucleation in 17 cases (59%) and enucleoresection in 12 cases (41%). Hemostatic agents were used in 24 cases (83%). In two cases, when calyceal openings occurred intraoperatively, they were sutured using a 3/0 absorbable monofilament running suture. In one patient with a false urethral pathway following recent transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), catheter placement required a rigid cystoscope and guide-wire assistance.

Intraoperative outcomes

| Outcome | Value |

| Operative time, min | 135 (110-160) |

| Enucleation, n (%) | 17 (59) |

| Enucleo-resection, n (%) | 12 (41) |

| Resection, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| of Clamping on demand, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Sutureless, n (%) | 29 (100) |

| Drain, n (%) | 3 (10) |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 100 (50-100) |

| Use of hemostatic agents | 24 (83) |

| Intraoperative adverse events, n (%) | 3 (10) |

| Urinary collecting system violation, n (%) | 2 (7) |

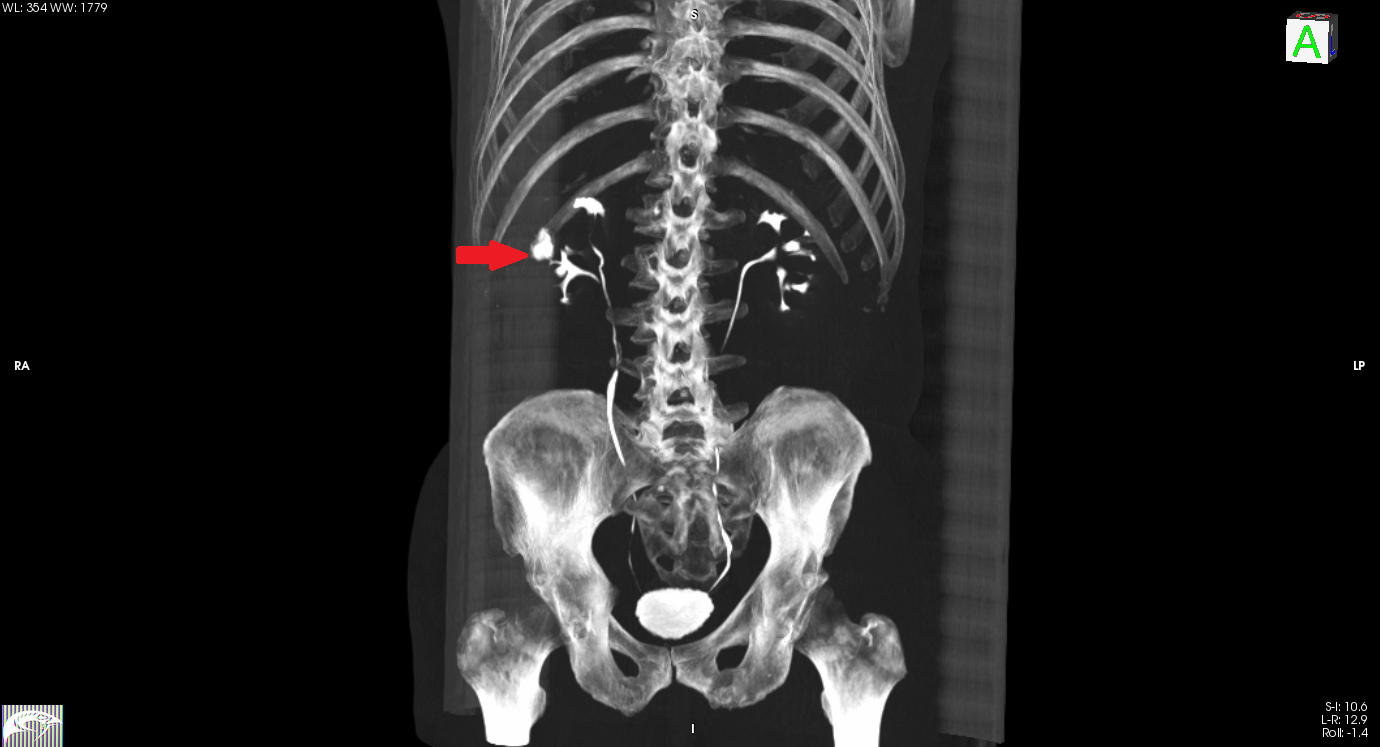

Postoperative outcomes [Table 4] indicated that three patients (10%) experienced Clavien-Dindo ≥ 3 complications: two cases involved urine leakage (different from the cases with intraoperative calyceal suturing) requiring ureteral stent placement [Figure 1], and one case involved postoperative bleeding requiring transfusion. Minor complications included fever > 38 °C in two patients on postoperative day 2 without respiratory symptoms. Urine and blood cultures, as well as chest X-rays, were performed; findings suggested bronchial thickening consistent with bronchitis, later confirmed by CT. Pulmonology consultation led to antibiotic therapy and follow-up imaging at discharge.

Figure 1. 3D Tc scan reconstruction of a patient with an incomplete right renal duplex collecting system who developed urinary leakage (red arrow).

Postoperative outcomes

| Outcome | Value |

| Postoperative adverse events, n (%) | 5 (17) |

| Clavien I-II, n (%) | 2 (7) |

| Clavien III- IV, n (%) | 3 (10) |

| Fever, n (%) | 2 (7) |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 1 (3) |

| Urine leakage, n (%) | 2 (7) |

| Mobilization from bed, days | 2 (2-3) |

| Intestinal canalization, days | 2 (1-3) |

| Length of Hospitalization, days | 3 (2-5) |

| Hemoglobin at discharge, g/dL | 12.9 (11.8-14.3) |

| Serum Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.7-1.05) |

| eGFR at discharge, mL/min | 86 (68-95) |

Patients were mobilized on postoperative day 2 and could ambulate independently on day 3. Bowel function recovery occurred between postoperative days 1 and 3, with discharge only after passing gas. The median Length of Hospitalization was 3 days.

Pathological outcomes [Table 5] showed that four patients (14%) with benign lesions had positive surgical margins in the final histology.

Pathological outcomes

| Outcome | Value |

| Benign Lesion, n (%) | 11 (38) |

| Malignant Lesion, n (%) | 18 (62) |

| Grading I-II, n (%) | 10 (55) |

| Grading III-IV, n (%) | 8 (45) |

| Positive Margins, n (%) | 4 (14) |

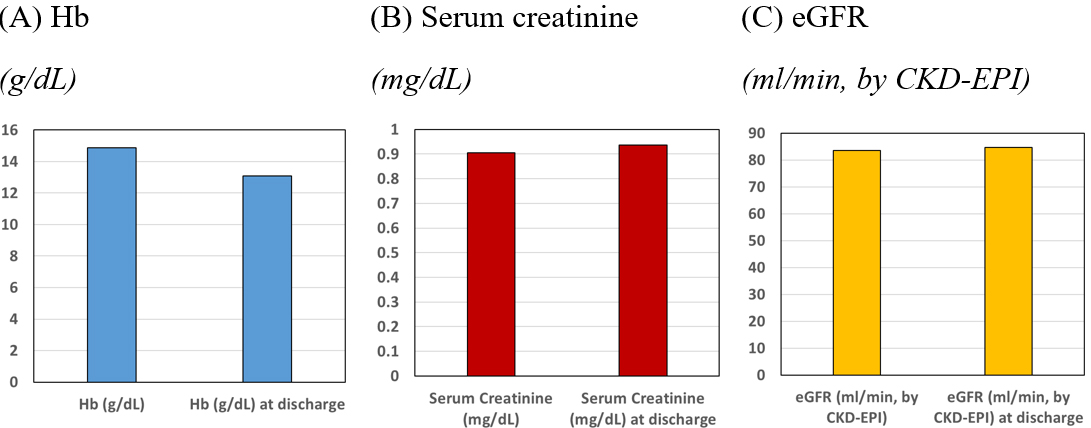

Hemoglobin and renal function are summarized in Table 6 and Figure 2. The mean preoperative hemoglobin was 14.9 g/dL, decreasing to 13.1 g/dL at discharge, representing a statistically significant reduction (P = 0.005). Mean preoperative creatinine and eGFR were 0.91 mg/dL and 84 mL/min, respectively. No statistically significant changes were observed in creatinine or eGFR at discharge or at 3 months postoperatively (P > 0.05).

Figure 2. Preoperative and postoperative (discharge) assessment of hemoglobin, serum creatinine, and eGFR. CKD: Chronic kidney disease; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Hemoglobin and renal function

| Parameter | Preop (a) | Postop at discharge (b) | Postop difference (b -a) | Postop at 3 months (c) | Postop difference (c -a) | Cohen’s d |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.94 | 13.14 | -1.80*** | 1.13 | ||

| (-2.10, -1.30) | ||||||

| Serum Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.14 | -0.10 |

| (-0.03, 0.10) | (-0.05, 0.12) | |||||

| eGFR, mL/min | 85 | 84 | -1.00 | 75 | -10 | -0.04 |

| (-7.05, 9.05) | (-22.04, 2.09) |

DISCUSSION

PN is considered the gold-standard treatment for T1 renal tumors, as it demonstrates non-inferiority in terms of cancer-specific survival (CSS) compared with radical nephrectomy (RN)[12]. Moreover, PN more effectively preserves kidney function over time, thereby reducing the risk of cardiovascular complications and the development of end-stage renal disease (ESRD)[1].

Although the optimal surgical approach remains debated, the EAU guidelines indicate that RAPN may offer advantages in perioperative and functional outcomes compared with open and laparoscopic techniques. Comparative studies show that RAPN is associated with less blood loss, fewer major complications, and shorter hospital stays than open surgery[3-5]. Compared with laparoscopy, RAPN provides shorter operative times, improved dissection planes that allow for more precise enucleation, and reduced removal of healthy parenchyma. Moreover, RAPN has been linked to lower conversion rates to both open surgery and radical nephrectomy than the laparoscopic approach[13].

Beyond the choice of approach, two aspects of RAPN are of particular importance: (1) management of the renal hilum before enucleation (clamping vs. not clamping the renal artery) and (2) reconstruction of the renal parenchyma following tumor enucleation (renorrhaphy vs. sutureless techniques).

With respect to hilar management, the traditional technique involves clamping the renal artery, which subjects the renal parenchyma to ischemia followed by reperfusion injury, potentially impairing renal function[14]. In recent years, however, off-clamp and selective-clamp techniques have been increasingly adopted in PN, aiming to minimize or eliminate warm ischemia time and improve functional outcomes. In 2019, Antonelli et al. conducted the first review and meta-analysis and reported no statistically significant differences in functional outcomes between off-clamp and on-clamp approaches[6]. More recently, Fong et al., in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), found that off-clamp RAPN may provide better preservation of renal function and lower rates of positive margins in selected small renal masses[8]. Both analyses included large cohorts, but a key limitation was that functional outcomes were typically reported as overall eGFR rather than split renal function. Anceschi et al. compared off-clamp and on-clamp RAPN in patients with solitary kidneys, with a median follow-up of 13 months Off-clamp RAPN was associated with significantly smaller declines in eGFR compared with on-clamp[15], although this was a small retrospective study. Nonetheless, it provides valuable insights into functional outcomes and the risks of chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression. In addition, a systematic review by Bertolo et al. reported that clampless approaches were more frequently chosen for enucleation and were associated with lower rates of both overall and major complications compared with planned enucleation[16]. However, superselective clamping did not demonstrate superiority in terms of renal function preservation.

Another factor to consider when comparing off-clamp versus on-clamp techniques is the risk of bleeding. It has been suggested that off-clamp surgery may lead to greater blood loss, which can obscure the tumor bed and increase the risk of positive surgical margins. In a matched-pair analysis of the multicentric Vattikuti Collective Quality Initiative (VCQI) database, Sharma et al. found that the rates of blood transfusion and conversion to radical nephrectomy due to bleeding were significantly higher in the off-clamp group[17]. In contrast, Antonelli et al., analyzing data from the largest prospective randomized trial (CLOCK trial; NCT02287987)[18], reported that EBL and postoperative anemia were comparable between the two approaches.

With regard to the reconstruction of renal parenchyma, although renorrhaphy plays a pivotal role in determining the functional outcomes of partial nephrectomy, current urological guidelines provide no recommendations on the optimal renorrhaphy technique. In conventional practice, following tumor excision, the surgeon performs either a single- or double-layer suture of the healthy renal parenchyma. However, recent studies suggest that suturing the renal parenchyma may contribute to renal ischemia and, consequently, parenchymal loss, leading to a subsequent decline in global renal function[19]. Moreover, renorrhaphy may cause ischemic necrosis of the sutured tissue, thereby increasing the risk of pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas[20].

In response, renorrhaphy techniques have evolved toward the concept of “nephron-sparing renal reconstruction”, where single-layer renorrhaphy provides functional advantages without increasing postoperative complications[21].

The introduction of sutureless techniques has further advanced this field. A recent meta-analysis of five retrospective studies including 634 patients demonstrated that sutureless methods reduce both operative time and warm ischemia time, while maintaining renal function and without increasing postoperative complications[22].

Franco et al. recently demonstrated the feasibility and safety of sl-oc RAPN in terms of both functional outcomes and bleeding control for renal masses with a PADUA score ≤ 6 (median score 4)[23]. In this study, postoperative scintigraphy enabled separate evaluation of renal function in both kidneys, revealing reduced function in the operated kidney. The main limitation of this study is the absence of a control group, as it represents an early experience in the management of non-complex renal tumors.

Within this context, the present study aimed to describe the surgical technique and outcomes of an unselected series of sl-oc RAPN performed for renal masses of intermediate complexity (median PADUA score 8) by a surgeon with extensive experience in robotic PN at a tertiary referral center. This study represents a preliminary experience with an equally effective surgical technique for T1 renal cell carcinoma. Our findings align with results reported in the existing literature as well as with other series of on-clamp and double-layer renorrhaphy RAPNs conducted at our institution (data not shown).

The off-clamp approach allowed individual bleeding sources to be precisely identified. The assistant surgeon played a critical role in exposing the resection bed, which enabled targeted hemostasis. Bleeding vessels were selectively coagulated in a pinpoint fashion using monopolar or bipolar energy, resulting in an EBL of only ~ 100 mL per procedure.

Regarding the use of hemostatic agents, these were initially applied in all cases due to limited early experience with the sutureless technique, even when bleeding did not necessitate their use and they were employed only as a precaution. With increasing familiarity, the surgeon adopted a more selective approach, and in the most recent cases of the study, no hemostatic agents were used.

It is noteworthy that two patients developed urinary leakage from the collecting system, requiring ureteral stent placement. In both cases, the tumor base was located close to the urinary tract, but no intraoperative violation was observed. Bleeding was well controlled and did not obscure the surgical field, allowing us to reasonably exclude an intraoperative injury to the collecting system. Instead, we believe the leakage likely developed in the immediate postoperative period. This suggests that a potential weakness of the technique is the risk of urinary fistula formation. Our rationale is that the use of sealant sutures might have prevented leakage by reinforcing the renal parenchyma and supporting the urinary tract, thereby limiting urine extravasation from a compromised collecting system.

With few exceptions, and given the relatively high complexity of the tumors in this series (mean PADUA score 8), extensive kidney mobilization was performed in most cases. The ureter and renal hilum were identified and isolated with a vessel loop before tumor resection. It is plausible that ureteral manipulation may have disrupted peristalsis or caused wall edema, leading to narrowing of the ureteral lumen. This, in turn, could have transiently increased intrapelvic pressure, ultimately resulting in rupture of the urinary tract at its most vulnerable point.

Regarding the histological findings, positive margins were identified in four renal lesions, all corresponding to angiomyolipomas. These lesions had been evaluated preoperatively by renal ultrasonography and CT scan, which already indicated benign features. Surgery was performed due to their size (average 4.2 cm) and associated risk of bleeding. The positive margins were attributable to traction artifacts and the presence of a very thin pseudocapsule typical of these lesions, which is prone to rupture.

With respect to bleeding risk, we observed a mean hemoglobin drop of 1.8 g/dL [Table 6], corresponding to an EBL of approximately 300 mL. In contrast, our median intraoperative EBL was only about 100 mL. This discrepancy likely reflects the underestimation of intraoperative blood loss, since blood absorbed by gauze placed inside the abdomen is not accounted for. Another factor is the different statistical measures used: the t-test compared mean hemoglobin levels at admission and discharge, whereas EBL is reported as a median, which is more robust to outliers, including one patient who experienced significant bleeding requiring hemotransfusion.

Regarding kidney function, the overall reduction in eGFR at 3 months was 10 mL/min, which was not statistically significant. On average, this decline did not result in a change in CKD stage compared with preoperative levels, which remained at stage II (eGFR 60-89 mL/min).

Specifically, among the 29 patients enrolled, 12 had normal renal function, 15 had mild impairment (stage II CKD, eGFR 60-89 mL/min), and 2 had stage IIIb CKD. Patients were stratified into three groups based on eGFR, and values before surgery were compared with those at 3 months. No significant differences were found within groups, and all patients maintained the same CKD stage postoperatively.

With respect to the surgeon's learning curve across the 29 procedures, operative time showed a modest reduction - from an average of 153 min in the first 20 surgeries to 126 min in the last 9. These times are somewhat longer than those reported in the literature[22], but it should be noted that the current study involved lesions of intermediate complexity (PADUA score 8) and considered total operative time rather than only “console time”. EBL remained stable across the learning curve. Importantly, in the last 5 cases, no hemostatic agents were used, yet the median EBL remained 100 mL. Complications of Clavien-Dindo grade > 3 still occurred within the first 20 cases.

This study has several limitations. The sample size is relatively small, although it reflects the introduction of the sutureless technique by a surgeon already experienced in both clamped and unclamped robot-assisted partial nephrectomies with renorrhaphy. While the study was sufficiently powered to detect large differences in hemoglobin (Cohen’s d = 1.13; power > 99%), it was underpowered to detect small changes in serum creatinine or eGFR. The effect sizes for these variables were negligible (d < 0.1), suggesting either minimal clinical impact or high variability. This limitation should be considered when interpreting non-significant results. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these results. This pilot study reports the first 29 cases performed with this new technique; further investigations with larger or multicenter cohorts are required to more effectively compare surgical alternatives. Another limitation is the lack of a control group, which restricts the generalization of our results. Randomized controlled trials will therefore be necessary.

A multivariate analysis was not conducted due to the limited sample size, which would have carried a high risk of overfitting and unreliable parameter estimates. Regression modeling with multiple covariates requires substantially larger samples to ensure statistical validity. Future studies with expanded cohorts are needed to identify independent predictors of postoperative outcomes.

A distinctive feature of this study, compared with existing literature, is that the renal masses treated were of intermediate complexity. Despite this, blood loss was minimal and renal function was preserved without significant decline.

Therefore, although the study is limited by its small sample size, lack of a control group, and the occurrence of urinary fistula in 2 of 29 cases, our findings suggest that the sl-oc RAPN is effective for the management of intermediate-complexity renal tumors in maintaining oncological outcomes, limiting complications, and preserving renal function.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Vittori M,

Methodology: Vittori M, Palermo G

Investigation: Filippi B, Petta F

Original draft preparation: Filippi B,

Data curation: Carilli V, Antonucci M

Validation: Petta F, Maiorino F, Signoretti M, Catuzzi R, Guidotti A, Said N, Di Stasi SM, Di Stasi SM

Reviewing and editing: Maiorino F, Signoretti M, Catuzzi R, Guidotti A, Said N, Iacovelli V, Di Stasi SM

Software: Forte V, Iacovelli V

Supervision: Di Stasi SM

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data are securely stored in a dedicated repository at San Carlo di Nancy Hospital in Rome. They are available from the corresponding author (

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted following ethical standards and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The local ethics committee (Comitato Etico Lazio 1) did not consider the application on the present clinical evaluation of aggregate/anonymous data from the institutional, routinely gathered record. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and archived at San Carlo di Nancy Hospital in Rome.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. EAU Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma Cancer 2024; EAU Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2024. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilations-of-all-guidelines/ (accessed on 2025-8-25).

2. AUA Guidelines on Renal Cancer 2024. Available from: https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/oncology-guidelines/renal-cancer (accessed on 2025-8-25).

3. Kowalewski KF. Neuberger M; Sidoti Abate MA; et al. Randomized controlled feasibility trial of robot-assisted versus conventional open partial nephrectomy: the ROBOCOP II study. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024;7:91-7.

4. Masson-Lecomte A, Yates DR, Hupertan V, et al. A prospective comparison of the pathologic and surgical outcomes obtained after elective treatment of renal cell carcinoma by open or robot-assisted partial nephrectomy. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:924.

5. Peyronnet B, Seisen T, Oger E, et al. Comparison of 1800 robotic and open partial nephrectomies for renal tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:4277.

6. Antonelli A, Veccia A, Francavilla S, et al. On-clamp versus off-clamp robotic partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urologia. 2019;86:52-62.

7. Antonelli A, Cindolo L, Sandri M, et al. Is off-clamp robot-assisted partial nephrectomy beneficial for renal function? BJU Int. 2022;129:217-24.

8. Fong KY, Gan VHL, Lim BJH, et al. Off-clamp vs on-clamp robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2024;133:375-86.

9. Ficarra V, Novara G, Secco S, et al. Preoperative aspects and dimensions used for an anatomical (PADUA) classification of renal tumours in patients who are candidates for nephron-sparing surgery. Eur Urol. 2009;56:786-93.

10. Kutikov A, Uzzo RG. The R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score: a comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location and depth. J Urol. 2009;182:844-53.

11. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-13.

12. Van Poppel H, Da Pozzo L, Albrecht W, et al. A prospective, randomised EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the oncologic outcome of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;59:543-52.

13. Choi JE, You JH, Kim DK, Rha KH, Lee SH. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2015;67:891-901.

14. Thompson RH, lane BR, Lohse CM, et al. Every minute counts when the renal hilum is clamped during partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2010;58:340-45.

15. Anceschi U, Brassetti A, Bertolo R, et al. On-clamp versus purely off-clamp robot-assisted partial nephrectomy in solitary kidneys: comparison of perioperative outcomes and chronic kidney disease progression at two high volume centers. Minerva Urol Nephrol. 2021;73:739-745.

16. Bertolo R, Pecoraro A, Carbonara U, et al. European Association of Urology Young Academic Urologists Renal Cancer Working Group. Resection techniques during robotic partial nephrectomy: a systematic review. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2023;52:7-21.

17. Sharma G, Shah M, Ahluwalia P et al. Off-clamp versus on-clamp robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: a propensity-matched analysis. Eur Urol Oncol. 2023;6:525-30.

18. Antonelli A, Cindolo L, Sandri M et al. Safety of on- vs off-clamp robotic partial nephrectomy: per-protocol analysis from the data of the CLOCK randomized trial. World J Urol. 2020;38:1101-8.

19. Bertolo R, Campi R, Mir MC, et al. Young Academic Urologists Kidney Cancer Working Group of the European Urological Association. Systematic review and pooled analysis of the impact of renorrhaphy techniques on renal functional outcome after partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol Oncol. 2019;2:572-5.

20. Brassetti A, Misuraca L, Anceschi U, et al. Sutureless purely off-clamp robotassisted partial nephrectomy: avoiding renorrhaphy does not jeopardize surgical and functional outcomes. Cancers. 2023;15:698.

21. Bertolo R, Cipriani C, Vittori M, et al. Robotic off-clamp simple enucleation single-layer renorrhaphy partial nephrectomy (ROSS): surgical insights after an initial experience. J Clin Med. 2022;12:198.

22. Liu P, Li Y, Shi B, Zhang Q, Guo H. The outcome of sutureless in partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:5260131.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].