Basal metabolic rate and cardiovascular diseases in women: mechanistic insights and clinical implications

Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) pose a significant threat to global public health and are the leading cause of death in women. Basal metabolic rate (BMR), which reflects the minimum energy expenditure required to maintain essential physiological functions at rest, has emerged as a crucial indicator of energy metabolism and a potential predictor of disease risk and health status. This review comprehensively examines the role of BMR in women’s CVDs, exploring its associations with body composition, thyroid function, mitochondrial efficiency, and the autonomic nervous system. It also delves into how BMR influences CVD risk across different physiological stages in women, including the reproductive years, pregnancy, and menopausal transition. Furthermore, this review proposes a diagnostic and therapeutic framework centered on BMR, encompassing precise assessment, pharmacological interventions, lifestyle modifications, and the application of emerging technologies. The aim is to enhance women’s cardiovascular health and reduce premature mortality.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

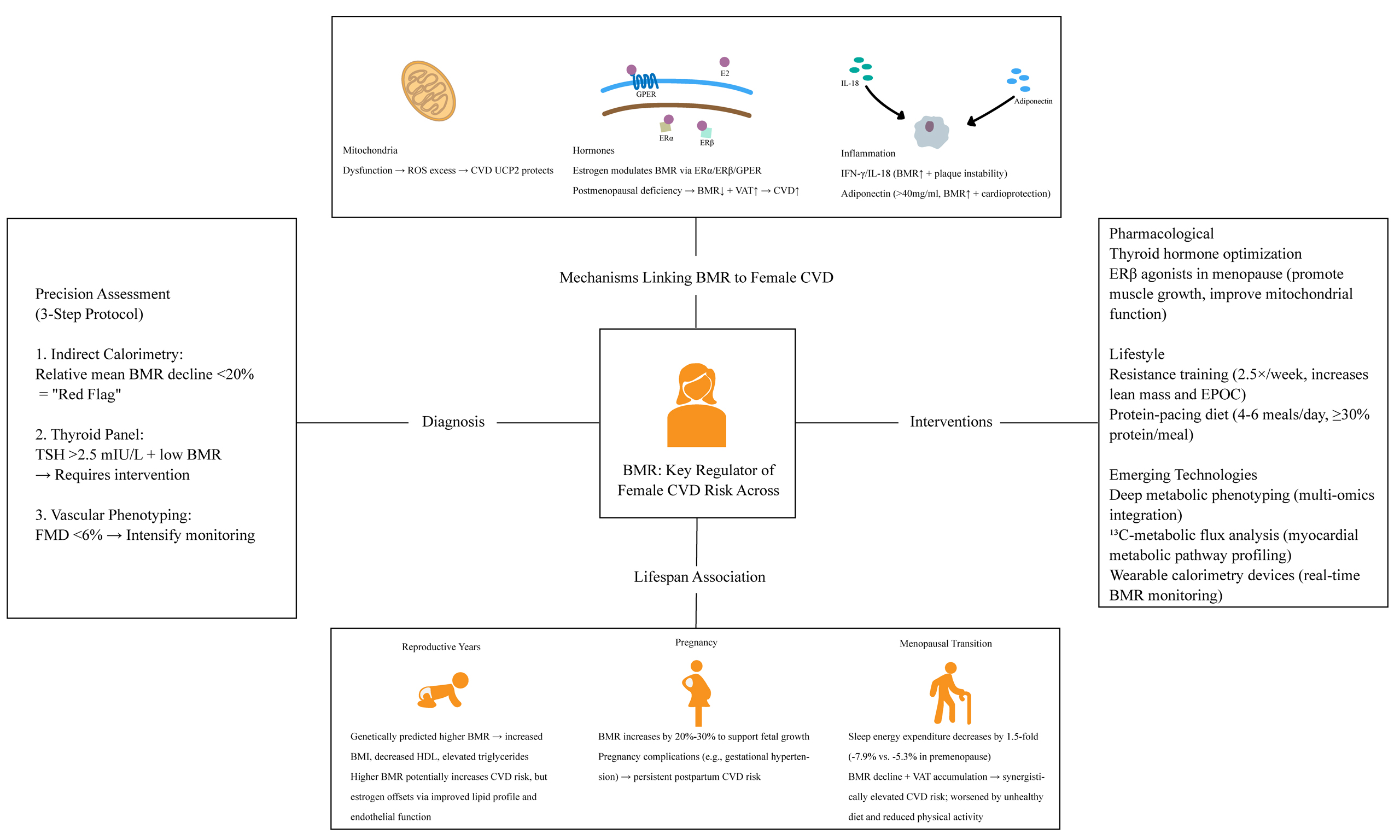

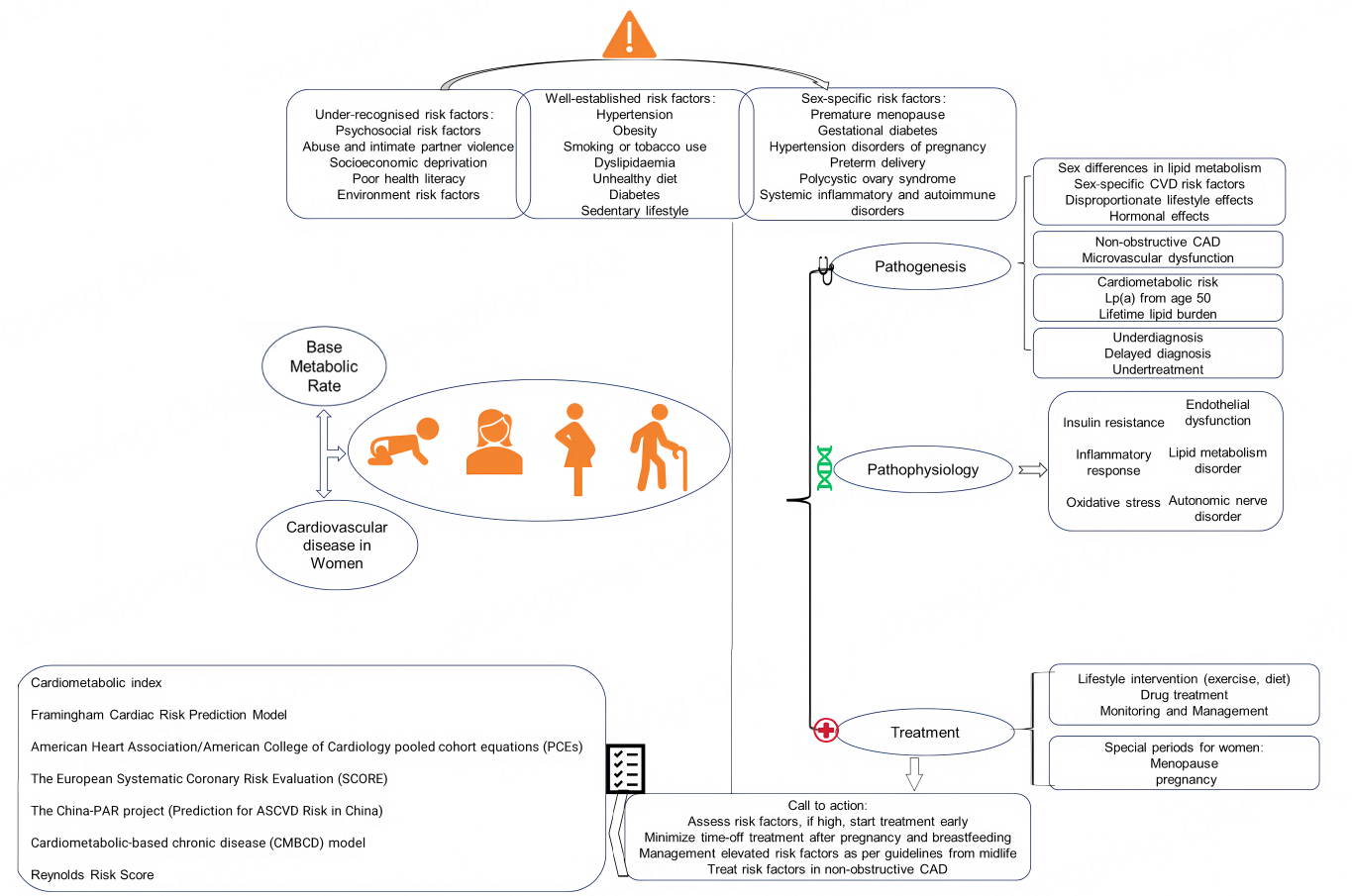

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a global public health issue that threatens humanity, accounting for approximately one-third of all disease-related deaths and posing an increasing economic burden[1,2]. It is also the leading cause of death in women, responsible for 35% of all female fatalities in 2019[3]. While ischemic heart disease and stroke are the most common causes of cardiovascular mortality in women[3], the INTERHEART study - a case-control study of 27,098 participants from 52 countries - revealed that men experience their first acute myocardial infarction nearly a decade earlier than women[4]. Women are relatively protected from CVD before menopause but lose this advantage afterward. Despite progress in medical research and public health, CVD mortality has declined more slowly in women than in men, underscoring a persistent sex gap in cardiovascular outcomes. Early identification and aggressive management of cardiovascular risk factors are therefore essential to improve women’s cardiovascular health and reduce premature death. We have summarized some risks, evolutions and treatments of CVDs in women, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Multidimensional Analysis and Management of Cardiovascular Disease in Women[5-11]. This chart presents: (1) the multifactorial influences on cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in females, including under-recognized risk factors, established risk factors and gender-specific factors; (2) the pathogenesis of CVD outlined from pathophysiological and pathological perspectives; (3) various risk prediction models applicable to females; (4) management strategies for CVD, including the management strategies for women during special periods (menopause, pregnancy). Lp(a): Lipoprotein(a); CAD: coronary artery disease; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease.

BASAL METABOLIC RATE AS A METABOLIC INTEGRATOR

Basal metabolic rate (BMR) is defined as the minimum daily energy expenditure that an individual needs to maintain the essential physiological functions of the body, such as respiration, circulation, and cellular activity. It is measured under both awake and steady‐state conditions which, as far as possible, avoid the influence of food, physical activity, or external temperature extremes[12]. In individuals, BMR accounts for approximately 60% to 70% of daily energy expenditure and is highly predicted by lean body mass[13,14]. Recent studies reveal that BMR is not only a core parameter of energy metabolism but also an independent biomarker for predicting disease risk and assessing health status. Lower BMR has been associated with obesity and insulin resistance[15,16], while elevated BMR paradoxically predicts cardiovascular mortality and multimorbidity in the elderly[17-19].

In this article, “BMR” refers to energy expenditure measured under strictly controlled conditions (after overnight sleep and fasting, in a thermoneutral environment, in the supine position, and without recent physical or emotional stress). “Resting energy expenditure (REE)” refers to energy expenditure measured under similar but less stringent conditions and is typically slightly higher than BMR. Because many clinical and epidemiological studies use these terms interchangeably, we retain the original terminology of the cited studies. In general descriptive sections, unless otherwise specified, BMR/REE refers to basal or resting metabolic rate.

Body composition and energy homeostasis

BMR is strongly influenced by lean body mass. Metabolically active tissues, such as muscle, account for approximately 70% of daily energy expenditure[12]. Age-related declines in lean body mass accelerate BMR reduction. This predisposes individuals to obesity and type 2 diabetes[15-17]. Notably, women have 5%-10% lower BMR than men. The main reasons are their reduced muscle mass and higher adiposity[20]. Resistance training can mitigate this BMR decline. It increases lean body mass, which elevates BMR by 5%-7%. This effect has been observed in postmenopausal women with reduced adipokine levels (e.g., adiponectin)[21]. Zampino et al.[19] revealed a key finding: comorbidities such as heart failure (HF) further exacerbate BMR decline in older adults. This creates a bidirectional link between metabolic efficiency and disease progression.

Thyroid axis regulation

Thyroid hormones [THs; Triiodothyronine (T3) and Thyroxine (T4)] are central regulators of BMR. Hypothyroidism reduces BMR by 15%-40%, contributing to weight gain, while hyperthyroidism elevates BMR by 20%-100%[12]. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction may subtly alter BMR and increase CVD risk[22]. For instance, mitochondrial dysfunction in HF patients correlates with reduced BMR and cardiomyocyte energy deprivation[22].

Mitochondrial efficiency

Mitochondrial health is critical for BMR maintenance. Impaired adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) reduce metabolic efficiency. In chronic HF, mitochondrial decay accelerates BMR decline[22], whereas hyperthyroidism-associated mitochondrial hyperactivity elevates BMR but exacerbates oxidative stress, increasing atrial fibrillation (AF) risk[23].

Sympathetic nervous system modulation

Chronic Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) activation (e.g., in hypertension) elevates BMR via

Sex-specific determinants of BMR

Women experience unique BMR fluctuations due to hormonal changes. In the luteal phase, progesterone-driven thermogenesis increases BMR by 5%-10%[19], alongside elevated energy intake (159-529 kcal/day)[2]. In menopause, reduced lean body mass and BMR accelerate metabolic decline, with higher BMR linked to a 1.5-fold increased risk of multimorbidity[18]. Moreover, Pregnancy increases BMR by 20%-30% to support fetal growth[19], a metabolic adaptation critical for maternal and fetal health.

BMR and cardiovascular disease

BMR, a reflection of the energy expenditure necessary to maintain essential physiological functions at rest, has been increasingly studied as a potential determinant of cardiovascular health[25]. Although traditionally considered a background metabolic parameter, recent evidence from genetic and epidemiological studies suggests a more complex and potentially causal relationship between BMR and CVD, with notable differences observed between sexes.

Multiple Mendelian randomization (MR) studies have examined the causal role of genetically predicted BMR in the development of cardiovascular conditions. Zhao et al. (2024) found robust evidence supporting a causal relationship between elevated BMR and an increased risk of HF, AF and flutter. However, the study reported no causal association between BMR and coronary artery disease or ischemic stroke, and reverse MR analysis showed no evidence that CVDs causally influence BMR, suggesting a unidirectional effect[25].

Complementing these findings, Chen et al. identified potential causal links between increased BMR and cardiomyopathy, HF, and valvular disease, while similarly observing no significant associations with coronary heart disease or AF[26]. This indicates that BMR may influence structural and functional aspects of the heart more than atherosclerotic conditions. Li et al. provided a nuanced view through univariable and multivariable MR approaches. After adjusting for conventional cardiovascular risk factors [e.g., body mass index (BMI), blood pressure], BMR remained positively associated with an increased risk of aortic aneurysm and AF/flutter, while paradoxically demonstrating a protective association with myocardial infarction. The causal link with HF, however, appeared attenuated in multivariable models, underscoring the potential for confounding in earlier associations[27].

Beyond genetic causality, sex-specific differences in the metabolic and cardiovascular implications of BMR have also been observed. Alcantara et al. showed that men exhibit higher intra-assessment variability in BMR and respiratory exchange variables such as oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2). This variability may itself serve as a metabolic stress marker. Importantly, the coefficient of variation (CV) for the respiratory exchange ratio was associated with increased cardiometabolic risk, particularly in males aged 21-25 years[28]. In a follow-up study, Alcantara et al. revealed

Current evidence suggests that BMR is not merely a background metabolic parameter but may actively shape cardiovascular risk, especially for diseases involving myocardial structure and rhythm disturbances. Sex differences in BMR variability and its association with cardiometabolic traits imply that women may benefit from more stable metabolic profiles, while men exhibit greater susceptibility to adverse outcomes with increased metabolic variability. These findings warrant further investigation and support the inclusion of BMR in sex-specific cardiovascular risk assessment frameworks.

MECHANISMS OF BMR IN CVD

Mitochondrial pathways

As a core indicator of energy metabolism, BMR is intimately linked to cardiovascular impairment. Recent studies reveal that this association is particularly pronounced in women[31,32]. The post-menopausal decline in estrogen levels can modulate mitochondrial biogenesis through epigenetic mechanisms, leading to concurrent disruptions in BMR and elevated cardiovascular risk[33]. When mitochondrial integrity is compromised, not only is ATP synthesis markedly reduced, but metabolic reprogramming also ensues, triggering system-wide energy imbalance[34]. The accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria initiates a vicious cycle: electron transport chain overload results in excessive ROS production[3], which in turn exacerbates electron leakage by suppressing complex I activity - culminating in a rapidly amplifying oxidative stress storm[35]. A study revealed sex-specific differences in pyruvate kinase 2 (Pkm2) expression in mouse models of cardiac pressure overload, suggesting a link between mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) dysfunction and BMR abnormalities[36].

The coupling of energy metabolism and oxidative stress is particularly prominent in CVD development[37], with metabolic profiles and clinical outcomes often differing between genders[38]. In ischemic-reperfusion mouse models, estrogen protects the heart by reducing mitochondrial injury - an effect lost in ovariectomized females[39]. This underscores a mechanism by which BMR abnormalities influence CVD: energy metabolism dysregulation triggers multi-level damage via the mitochondrial respiratory axis[40].

Sex-related myocardial metabolic shifts may causally influence cardiac dysfunction risk in women, characterized by increased myocardial oxygen consumption (MVO2) and fatty acid metabolism, alongside decreased efficiency[41]. Taking vascular endothelial cells (ECs) as an example, although they primarily generate ATP via glycolysis[42], mitochondrial ATP is crucial for maintaining endothelial function - it supplies reducing equivalents for endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) to support nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation[43]. New evidence shows that enhanced mitochondrial respiration significantly increases phosphorylated eNOS levels in the cerebral arteries of female rats. This mechanism contributes to the greater adaptability of the female cerebral vasculature after injury[44].

Uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are a family of mitochondrial proteins present in the inner mitochondrial membrane. This protein converts mitochondrial membrane potential into heat through a proton leakage mechanism, which is an important bridge connecting BMR and cardiovascular protection: (1) In vascular smooth muscle cells, UCP2 reduces mitochondrial membrane potential to inhibit ROS, blocking nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)-mediated inflammation and delaying atherosclerotic plaque formation[10]; (2) In myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury models, UCP2 knockout disrupts calcium homeostasis, promoting mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening and amplifying cytochrome C release and apoptosis[45,46]; (3) UCP2 promotes macrophage transition from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype via mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming, offering new therapeutic insights for

Hormonal regulation

As the principal sex hormone in females, estrogen extends its biological significance far beyond reproductive regulation, emerging as a critical modulator of systemic energy metabolism and cardiovascular pathophysiology. This steroid hormone orchestrates a sophisticated crosstalk with BMR through multifaceted mechanisms involving metabolic programming, energy partitioning, and inflammatory modulation, with its dysregulation being intrinsically linked to CVD progression[40].

The cardiovascular actions of estrogen are primarily mediated through three distinct receptor systems: nuclear estrogen receptor α (ERα), estrogen receptor β (ERβ), and the membrane-associated G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER/GPR30)[48]. These receptors execute both genomic and non-genomic signaling cascades to maintain cardiovascular homeostasis. Emerging evidence reveals that each receptor subtype demonstrates unique tissue-specific expression patterns and functional specialization in cardiovascular physiology[48]. For instance, ERβ activation has been shown to stabilize the β1 subunit of

Animal studies have demonstrated that ERα deficiency induces contractile and/or metabolic dysregulation in cardiac tissue, skeletal muscle, and white adipose tissue. This pathological alteration functionally compromises cellular glycolytic capacity and reserve mechanisms, thereby redirecting energy towards storage rather than expenditure[50]. Consequently, this metabolic reprogramming promotes adipose tissue accumulation and ultimately leads to obesity development. GPER demonstrates distinct metabolic regulatory properties through its predominant expression in adipose tissue. Activation of this receptor subtype enhances brown adipose tissue thermogenesis by upregulating uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1) expression, thereby increasing energy expenditure[51]. Concurrently, GPER signaling suppresses

Estrogen has been established as a critical regulator of energy homeostasis and metabolic health[52]. Experimental and clinical evidence demonstrates that estrogen deficiency significantly reduces BMR, subsequently leading to progressive weight gain and manifesting a spectrum of metabolic syndrome characteristics. Intriguingly, the subsequent decline in BMR appears to suppress estrogen sulfotransferase (EST) activity, creating localized estrogen excess through impaired hormone catabolism[53]. This paradoxical hyperestrogenism may exacerbate cardiovascular risks by promoting endothelial dysfunction, enhancing platelet aggregation, and inducing insulin resistance.

Perimenopausal women frequently employ hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to alleviate estrogen deficiency-induced symptoms including vasomotor manifestations (e.g., hot flashes, sleep disturbances, and mood alterations). However, emerging evidence reveals an intricate interaction between estrogen signaling and BMR regulation, with particular concern regarding menopausal hormone therapy’s potential association with elevated cardiovascular risks[54]. The current therapeutic challenge lies in reconciling HRT’s dual cardiometabolic effects, its cardioprotective properties versus prothrombotic propensity. Promising strategies include developing cardiovascular-tropic tissue-selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) with enhanced endothelial specificity, along with pharmacological modulation of estrogen metabolic enzymes (e.g., CYP19 aromatase and EST). The integration of multi-omics platforms, particularly lipidomics and fluxomics, enables precise mapping of estrogen’s metabolic circuitry, facilitating the development of personalized cardiovascular risk algorithms. Next-generation solutions may incorporate nanoparticle-mediated targeted delivery systems conjugated with estrogen receptor (ER)-specific ligands[52], potentially achieving localized cardiovascular benefits while minimizing systemic exposure risks.

As a pivotal metabolic regulator, estrogen orchestrates the integration of peripheral energy metabolism and cardiovascular homeostasis through sophisticated receptor-mediated mechanisms. The development of precision-targeted interventions modulating estrogen signaling networks, synergized with advanced metabolic profiling technologies, holds transformative potential for preventing and managing cardiometabolic disorders of endocrine origin.

Inflammatory mediators

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are independent risk factors for CVDs. Studies have shown that these populations often exhibit impaired metabolic states[55], which may be caused by increased secretion of

Adiponectin is also a kind of adipokine, which was initially proven to be able to regulate lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Coronary artery disease (CAD) patients are often characterized by decreased adiponectin, elevated levels of inflammatory factors such as IL-6, and increased infiltration of macrophages in epicardial adipose tissue[59]. Adiponectin is positively correlated with BMR (r = 0.52, P = 0.02)[60], and adiponectin levels above 40 mg/mL are associated with a better BMR[61]. Although some scholars have proposed that when the critical value is 40 mg/mL, higher adiponectin levels may be an adaptive response to various pathological processes (such as age-related homeostatic imbalance)[62], experimental studies elucidate its direct cardioprotective mechanisms: adiponectin inhibits foam cell formation by suppressing lipid droplet accumulation and cholesterol esterification in macrophages through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)-liver X receptor α (LXRα) pathway activation[63,64], while concurrently attenuating vascular inflammation via adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-dependent suppression of Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor-containing pyrin-3 protein (NLRP3) inflammasome activity[65].

The intricate interplay between inflammatory mediators and metabolic regulators underscores the complexity of CVD pathogenesis. IFN-γ and IL-18 exemplify the dual nature of immune molecules that concurrently influence vascular biology and systemic energy metabolism, while adiponectin represents a convergence point for metabolic regulation and anti-inflammatory protection. These findings collectively highlight that BMR abnormalities - whether driven by proinflammatory cytokine excess or adipokine deficiency - may serve as critical nodes linking metabolic dysfunction to cardiovascular pathology. Future research should focus on elucidating tissue-specific cytokine effects, regulation of adipokine secretion, and the therapeutic potential of targeting these pathways to simultaneously ameliorate metabolic and cardiovascular risk profiles in high-risk populations. Given the established mechanisms linking impaired metabolic state to CVDs, the next section will focus on the clinical evidence that supports these pathways in animal models and human populations.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE BY LIFE STAGE

The preceding sections have detailed the biological foundation through which BMR, functioning as a metabolic integrator, influences the cardiovascular system via mechanisms involving mitochondrial function, hormonal axes, and inflammatory networks. However, the actions of these mechanisms are not static; they are profoundly modulated by the dramatic endocrine and physiological shifts that occur across a woman’s lifespan[66]. Consequently, a meaningful assessment of the impact of BMR on CVD risk in women must be contextualized within specific life stages. This section will focus on distinct physiological windows in women - the reproductive years, pregnancy, and the menopausal transition - to systematically review the clinical evidence linking dynamic changes in BMR to CVD risk.

In the female population, the association between BMR and the risk of CVD shows significant differences at different physiological stages. This variability stems from the complex interactions among hormonal changes, metabolic adaptation and vascular remodeling processes. To enhance comparability among different life stages, this study structured and integrated BMR-related metabolic alterations and estrogen-dependent vascular and cardiac mechanisms, as presented in Table 1.

BMR and CVD risk in female populations: evidence from the reviewed article

| Life stage | Major metabolic/endocrine features | Vascular/cardiac implications | Supporting evidence |

| Reproductive years | Estrogen exerts cardioprotective effects Regulates lipid profiles and endothelial nitric oxide (NO) signaling | Estrogen activates the PI3K/Akt pathway to promote eNOS activation and NO production → enhances vasodilation and reduces vascular injury risk | 1. Nakamura et al. (2004) eNOS/NO mechanism[53] 2. Mahboobifard et al. (2013) WHI interpretation[52] |

| Pregnancy | Placental hormones regulate energy homeostasis BMR markedly increases | Pregnancy itself serves as a metabolic - vascular stress test; pregnancy-related metabolic alterations and complications may substantially increase future ASCVD risk | 1. Johansson et al. (2020) placental metabolic regulation[54] 2. Ceperuelo-Mallafré et al. (2025) pregnancy complications linked with long-term atherosclerotic risk[55] |

| Menopause transition | Decline in estrogen leads to reduced BMR and accelerated VAT accumulation | Loss of estrogen protection results in increased oxidative stress, vascular aging, and accelerated arterial stiffening → markedly higher CVD risk | 1. Osuna-Prieto et al. (2021) estrogen reduces oxidative vascular injury[56] 2. de Metz et al. (2008) decreased EE and increased VAT[57] |

| Across-life course | BMR is causally related to adverse lipid profiles (↑BMI, ↓HDL, ↑TG) | Higher BMR increases baseline metabolic load and elevates foundational cardiovascular risk across stages | 1. Feng et al. (2024) MR evidence demonstrating causal links between BMR and metabolic risk factors[51] |

Reproductive years

Women’s reproductive period is marked by profound physiological alterations, which may exert substantial impacts on BMR and CVD risk. Throughout this phase, fluctuations in hormonal levels - primarily estrogen and progesterone - play a pivotal role in regulating metabolic function and cardiovascular homeostasis[67]. Estrogen, for instance, exerts well-documented cardioprotective effects through mechanisms including lipid profile improvement, endothelial function enhancement, and anti-inflammatory actions. Nevertheless, the intricate relationship between BMR and these protective mechanisms remains incompletely elucidated.

Regarding BMR, accumulated evidence indicates that elevated BMR is significantly associated with increased BMI and dyslipidemia, characterized specifically by reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and elevated triglyceride levels. A large-scale MR study comprising over 1 million participants conclusively demonstrated that genetically predicted higher BMR showed significant associations with: increased BMI (β = 0.7538, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.6418-0.8659, P < 0.001), decreased HDL-C (β =

Pregnancy

Pregnancy constitutes a distinct physiological condition marked by profound remodeling of metabolic processes, the cardiovascular system, and endocrine homeostasis. While these adaptive changes are crucial for ensuring normal fetal growth and development, they may exert long-term consequences on maternal health. Throughout gestation, BMR demonstrates a significant elevation to accommodate the increased energy requirements associated with fetal development and maternal physiological adaptations[71]. The marked elevation in BMR is frequently accompanied by a constellation of physiological alterations, including dyslipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance, and blood pressure fluctuations, all of which may contribute to elevated cardiovascular risk. To date, the precise mechanistic relationships between BMR and pregnancy-associated complications remain incompletely understood. Nevertheless, emerging evidence suggests that gestational metabolic adaptations, particularly BMR modulation, may potentially influence the pathogenesis and progression of these conditions through multiple pathways, with consequent implications for long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

The postpartum period represents a physiological transition toward the pre-pregnancy state; however, this recovery process may be accompanied by persistent metabolic and cardiovascular adaptations. Notably, women with pregnancy complications often demonstrate sustained metabolic alterations and elevated cardiovascular risk profiles during the extended post-delivery period[66]. Consequently, elucidating the regulatory role of BMR during gestation and its protracted cardiovascular consequences is essential for formulating precision-based preventive strategies.

Furthermore, while the postpartum period is generally marked by a restoration of pre-pregnancy physiological homeostasis, this transitional phase may concurrently involve persistent metabolic and cardiovascular adaptations. Notably, women with antecedent pregnancy complications are prone to demonstrate sustained metabolic dysregulation and elevated cardiovascular risk profiles during extended postpartum follow-up periods[72]. Therefore, understanding the role of BMR in the context of pregnancy and its long-term implications for cardiovascular health is crucial for developing targeted interventions to mitigate these risks.

Menopause transition

The menopausal transition represents a profound alteration in a woman’s endocrine and metabolic milieu. This phase is characterized by a progressive decline in estrogen levels, which precipitates a cascade of physiological adaptations with potential implications for cardiovascular homeostasis. Notably, the attenuation of estrogen-mediated cardioprotection is postulated to underlie the elevated susceptibility to cardiovascular disorders among postmenopausal women[73]. This risk is further exacerbated by changes in body composition, lipid metabolism, and glucose tolerance that occur during the menopause transition.

A marked decline in BMR has been observed among menopausal women. Notably, when compared to the premenopausal control group, postmenopausal women exhibited a more pronounced reduction in sleep-related energy expenditure (sleeping EE), demonstrating a 1.5-fold greater decrease (-7.9% vs. -5.3%, respectively)[74]. The observed reduction in BMR appears to be associated with declining estrogen levels in menopausal women. Mechanistically, estrogen regulates energy expenditure through its modulatory effects on adipose tissue metabolism, particularly by influencing lipoprotein lipase activity and lipid mobilization. Abdominal adiposity - encompassing both visceral (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue - has been established as an independent risk factor for CVD. Studies indicate that VAT accumulation initiates during the premenopausal period and stabilizes post-menopause. This metabolic shift suggests that BMR decline may contribute to reduced energy expenditure, thereby promoting adipose tissue accumulation (particularly VAT) and potentially elevating CVD risk.

Furthermore, menopausal women exhibit unfavorable dietary modifications characterized by increased consumption of saturated fats and cholesterol, coupled with decreased protein and fiber intake. These nutritional alterations likely synergize with diminished BMR to exacerbate cardiovascular risk profiles[54]. Compounding these effects, physical activity-related energy expenditure (activity EE) demonstrates significant attenuation during the perimenopausal transition. The concurrent decline in both basal and activity-related energy expenditure may create a metabolic milieu conducive to CVD development.

Importantly, vascular and cardiac injury trajectories appear to differ across female life stages. Premenopausal women demonstrate a higher prevalence of ischemia and angina despite non-obstructive epicardial coronary disease, largely attributed to coronary microvascular dysfunction and endothelial impairment[75]. Postmenopausal women experience more pronounced endothelial NO pathway disruption, accelerated arterial stiffening, and higher progression of vascular calcification -biological changes that directly connect menopausal hormonal decline with worsening vascular aging[76,77]. In advanced age, women more frequently manifest HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), representing a late-stage phenotype characterized by ventricular - arterial coupling abnormalities and central arterial stiffening[78,79]. Together, these findings highlight that beyond metabolic derangement, stage-specific vascular mechanisms should be explicitly considered in female cardiovascular risk evaluation across the menopausal continuum.

DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC FRAMEWORK

In current medical research, accurate measurement of BMR is important for assessing CVD risk and developing personalized treatment plans[25]. Studies have shown that higher BMR is causally associated with cardiovascular metabolic risk factors such as BMI, triglyceride levels, waist circumference, and Glycosylated Hemoglobin, Type A1C (HbA1c), which play a key role in the pathogenesis of CVD[68].

Assessment protocol

High BMR is an independent predictor of mortality[17], and recent studies have begun exploring the association between BMR and CVD, providing a new avenue for integrating metabolic assessment into disease diagnosis and treatment planning. The construction of a joint metabolic-cardiovascular assessment system centered on BMR is expected to promote the application of precision medicine in CVD management[80]. Because of the complexity of the relationship between BMR and CVD, we propose three BMR-related assessment indicators - indirect calorimetry, thyroid function assessment, and vascular phenotyping - to help guide the timing of assessment and intervention in the management and treatment of CVD [Table 2][81].

Clinical algorithm for BMR-related assessment and management in cardiovascular disease

| Step | Action | Thresholds |

| 1 | Indirect calorimetry | Relative mean decline < 20% = Red flag |

| 2 | Thyroid panel | TSH > 2.5 mI U/L + low BMR → Treat |

| 3 | Vascular phenotyping | FMD < 6% → Intensify monitoring |

Step 1 Indirect calorimetry

Measurement of BMR by indirect calorimetry can provide clinicians with an accurate tool for assessing energy needs and thus optimizing nutritional support for patients[82,83]. Indirect calorimetry is a practical clinical method to accurately measure REE and thus derive BMR[82,84-87], which not only helps to identify patients who may be at high risk of CVD due to BMR abnormalities, but also provides a scientific basis for the timing of treatment. By monitoring changes in BMR, physicians can make timely adjustments to treatment regimens according to patients’ metabolic needs[88], preventing disease progression and reducing the risk of complications. When the BMR is greater than 20% below the average value of the corresponding conditions, it is necessary to be alert to the presence of hypothyroidism[89], Addison’s disease, nephrotic syndrome, pathological hunger, pituitary obesity and other diseases.

Step 2 thyroid panel

THs are key factors in regulating BMR[14]. If the BMR is high or severely low, it is important to be aware of thyroid disease[89]. T3 and T4 regulate the BMR by binding to thyroid receptors and affecting the metabolic activity of cells[89,90]. Elevated levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) are usually indicative of hypothyroidism, in which case the BMR is reduced. Conversely, lower TSH levels may indicate hyperthyroidism, with an elevated BMR. Elevated BMR is usually associated with increased energy expenditure, which may lead to increased oxidative stress, which in turn may impair the cardiovascular system. Low BMR may reflect hypothyroidism and is associated with dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and obesity, all of which are risk factors for CVD. Using TSH as a biomarker for CVD risk assessment, the level of TSH can be used as an indicator of CVD risk[90]. Elevated TSH may indicate an increased risk of the presence or development of CVD[91]. Regular monitoring of TSH levels can help in the early identification of high-risk individuals, leading to timely intervention.

Step 3 vascular phenotyping

BMR reflects the body’s energy metabolism level in the resting state, and changes in it may affect vascular function through a variety of mechanisms[92]. For example, a hypermetabolic state may increase oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, leading to endothelial dysfunction. Vascular phenotypic assay technologies [e.g., reactive hyperemia peripheral arterial tonometry (RH-PAT), flow-mediated dilation (FMD), and Endothelial Peripheral Arterial Tonometry (EndoPAT)] capture the vascular response to metabolic changes[92,93]. These technologies indirectly reflect the impact of BMR changes on the vascular endothelium by assessing indicators of vasodilatory function, flow-mediated reactive congestion, and so on. Non-invasive techniques such as

As an illustrative example, a hypothetical case is considered: a postmenopausal woman presents with typical symptoms of hypothyroidism (e.g., fatigue, cold intolerance, weight gain). Her BMR is 25% lower than the average for individuals of the same age and body composition, and her TSH level is elevated (4.2 mIU/L). If managed through the proposed diagnostic and therapeutic framework, the following diagnosis and treatment plan can be designed for the patient:

In terms of diagnosis, this result directly guides the prioritization of thyroid function tests to quickly diagnose hypothyroidism. Meanwhile, a 25% reduction in BMR also supports earlier and more CVD screening (e.g., lipid profile) compared to patients with mild BMR decline. Second, if the result of vascular phenotyping (FMD) is 4.8%, further subsequent examinations can be initiated: The patient’s low BMR, as a marker of impaired metabolic activity, suggests that endothelial dysfunction may be related to underlying metabolic disorders. Therefore, additional CVD-related examinations (e.g., carotid ultrasound) can be scheduled within 1 week to screen for subclinical vascular damage, instead of the conventional 2-4-week interval for outpatient follow-up.

In terms of treatment, BMR assessment continuously guides personalized plans: A 25% reduction in BMR indicates more severe metabolic suppression, prompting consideration of faster dose escalation after the initial levothyroxine dose to reach the drug titration concentration (e.g., 50 mcg per day instead of the standard 25 mcg per day). In addition, BMR can be rechecked every four weeks to adjust the dose (e.g., if BMR only increases by 5% after 4 weeks, increase by 12.5 mcg per day). Meanwhile, twice-weekly resistance training is prescribed with a focus on compound movements (e.g., squats, rows) to maximize lean body mass gain. BMR is remeasured after 8 weeks to adjust training volume (e.g., if BMR increase is < 8%, increase to 4 sets per movement). If BMR remains persistently low after initial intervention, ERβ agonists may be considered to promote adipocyte browning and muscle metabolism, further increasing BMR and reducing CVD risk.

This framework also has several potential challenges, including (1) limited accessibility of indirect calorimetry in primary medical institutions, which may delay BMR assessment in resource-poor areas and affect timely diagnosis; (2) the risk of over-reliance on BMR-CVD associations, as endothelial dysfunction in postmenopausal women may primarily result from estrogen deficiency rather than low BMR, potentially leading to misjudgment of intervention priorities; (3) individual variability in BMR response to treatment (e.g., genetic differences in metabolic regulation or concurrent subclinical nephropathy limiting BMR increases), which may create clinical uncertainty or prompt excessive dose adjustments; and (4) the logistical and economic burden of frequent BMR monitoring for patients with mobility limitations or restricted access to medical care, thereby reducing long-term adherence.

Precision interventions

Individual BMR and metabolic profiles vary according to body composition and hormone levels[95], even in populations with the same age, height, weight, and gender[21]. Therefore, precise intervention for the population based on BMR is one of the future research directions. There is evidence that pharmacologic interventions and lifestyle interventions may help women improve BMR and thereby reduce the risk of CVD.

Pharmacologic

Many drugs can affect BMR, including those used in both acute and chronic therapy. Examples include the central nervous system drug sibutramine, commonly used in weight-loss medications; the antidepressant fluoxetine; the antiepileptic carbamazepine; cardiovascular drugs such as beta-blockers; and antineoplastic agents[96,97]. Endocrine and metabolic drugs are a class of drugs that directly correlate with BMR, and there is a large body of data demonstrating that thyroxine and growth hormone can significantly influence metabolism[97]. Therefore, there is a potential benefit of intervening in BMR through hormonal drugs to improve low BMR.

Thyroid hormone optimization (FT3 > 3.5 pg/mL ideal)

TH (levothyroxine) significantly increases polycystic ovary syndrome (RMR) (up to 17%)[96], especially when correcting hypothyroidism. In hypothyroid patients, the levothyroxine sodium dose is adjusted according to TSH levels to maintain euthyroid status, thereby reducing the risk of CVD associated with abnormal thyroid function. In patients with hyperthyroidism, TH levels are controlled with drugs such as methimazole or propylthiouracil. TSH and TH levels are monitored regularly, and drug doses are adjusted to prevent adverse effects of fluctuations in thyroid function on the cardiovascular system[89,90]. In addition, when thyroid function abnormalities lead to dyslipidemia, combined use of lipid-regulating drugs (such as statins) to lower cholesterol levels and prevent atherosclerotic plaque formation, thereby reducing the risk of CVD[89].

ERβ agonists in menopause

Estrogen’s effects on metabolism are multifaceted, and it can influence adipose tissue, and thus overall metabolic status, by regulating adipogenesis, lipolysis, and adipocyte differentiation[98]. The role of ERβ in adipose tissue and metabolic regulation makes it a potential target for controlling the BMR to combat CVD[99]. Zahr et al.[100] note that ERβ activation promotes adipocyte browning, improves mitochondrial function and energy expenditure, reduces body weight and fat mass (FM), and improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, all of which have the potential to positively affect BMR[101]. Based on the potential regulatory effects of ERβ agonists on BMR, their use in the prevention and treatment of CVDs is feasible[100]. Meanwhile, ERβ agonists can stimulate skeletal muscle growth and regeneration, increase muscle strength and mass, and regulate metabolic processes in muscle, including promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and upregulating the glucose transporter protein Glut4 (glucose transporter type 4), thereby improving the efficiency of muscle energy utilization[98,101,102]. Muscle is one of the major sites of energy expenditure in the human body, and an increase in muscle mass improves energy expenditure in the basal state, thus positively affecting BMR[88,95,102].

Lifestyle interventions

Lifestyle interventions can effectively adjust BMR through a combination of rational diet, regular exercise, and adequate sleep, which is important for obesity prevention and control, the development of CVD, and has high feasibility as a means of preventing and managing CVD[103]. Sabounchi et al. (2013) systematically integrated 248 studies and proposed that the prevention and management of CVD for different population-specific BMR prediction equations, emphasizing the effects of age, gender, race, and body composition on BMR, and developed an online tool to support precision interventions[88].

Resistance training (2.5 × week-1)

Resistance training, as an effective lifestyle intervention, has a significant positive effect on improving BMR[104-106]. Resistance training is an effective way to increase muscle mass by counteracting resistance to create muscle tone and stimulate muscle fiber growth and repair, thereby increasing lean body mass[95]. Mitchell et al. have shown that Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption (EPOC) is evident after resistance training, and that the body’s energy expenditure remains higher than that of the quiet state, even hours after exercise has ended[104]. This means that with resistance training, we can expend more energy even during periods of inactivity, thus further increasing the level of energy expenditure throughout the day and creating favorable conditions for improving BMR[88]. Especially for middle-aged and elderly people[17], regular resistance training can help maintain muscle mass and prevent the decline of BMR due to muscle loss, thus maintaining the body’s energy expenditure level and reducing the risk of obesity and related metabolic CVDs.

Protein pacing

The protein-pacing caloric-restriction (P-CR) eating pattern is a diet that combines high-frequency protein intake (4-6 meals per day with at least 30% protein at each meal) with caloric restriction (25% reduction in energy intake per day)[107]. The core of the model is to optimize the body’s metabolic response by adjusting the structure of the diet and the frequency of eating. At the same time, a high-protein diet provides sufficient raw materials for muscle growth and promotes muscle synthesis[95,102]. For example, a daily protein intake of ≥ 1.3 g/kg for women in the study by Bi et al. helps to meet the needs of muscle growth and maintenance[102]. When muscle mass increases, the body’s BMR also increases accordingly, because muscle tissues also consume energy to maintain their normal physiological functions in the resting state.

Therefore, a well-designed resistance training program combined with a moderate high-protein diet can help women increase muscle mass and enhance BMR[20]. BMR and lean body mass are important predictors of daily energy intake, and significant gender differences exist. Lean body mass was positively associated with protein and fat intake in women, while FM was not associated with macronutrient intake[102]. This suggests that increasing lean body mass (e.g., by increasing muscle mass) may promote metabolic activity by elevating energy demand, especially more significantly in women. Syngle et al. also showed that Fat-Free Mass (FFM) is one of the major determinants of BMR, contributing about 60% of BMR, and that increasing FFM is expected to elevate BMR[108].

Emerging technologies

With the continuous progress and innovation of technology, many high-tech means are gradually penetrating into the field of BMR measurement.

Deep metabolic phenotyping

Deep metabolic phenotyping is an emerging, cutting-edge field. It employs a variety of advanced tools, including high-resolution mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, sophisticated bioinformatics, and deep learning algorithms, to provide comprehensive, multidimensional analyses of an organism’s metabolic state, aiming to reveal the complexity, dynamics, and interactions of metabolic networks with other biological processes[94,109]. Specifically, deep metabolic phenotyping integrates multi-omics data, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, to more accurately characterize the metabolic profile of an individual under different physiological states or disease conditions, and thus provide key information and insights for early diagnosis, mechanism research, personalized treatment, and drug discovery and development[94].

<sup>13</sup>C-metabolic flux analysis

The 13C-metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) is a technique to accurately quantify intracellular reaction rates by analyzing the distribution of isotopically labeled isomers of protein amino acids or intracellular metabolites via 13C labeling experiments[110-112]. It utilizes metabolic models and 13C isotope patterns of key metabolites to estimate reaction rates, thereby characterizing the metabolic state of microorganisms. Theoretically, 13C-MFA can be used to study metabolic pathways associated with BMR, and by accurately measuring and analyzing metabolic fluxes in these pathways, insights can be gained into how altered energy metabolism affects the function and health of the cardiovascular system. For example, studying the changes in metabolic fluxes in cardiomyocytes under different metabolic states can help to identify potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets of CVDs, and provide new ideas and methods for early diagnosis and intervention of CVDs[111]. However, the direct application of 13C-MFA to the study of the human cardiovascular system and its combination with BMR measurements for the prevention and treatment of CVDs still faces many challenges, and requires a lot of experimental studies and technology optimization.

Wearable calorimetry devices

Modern wearable calorimetry devices incorporate mature technologies, including high-precision sensors, advanced signal processing, and data transmission capabilities. Smart wearable devices monitor an individual’s movement and physiological state in real time by integrating multiple sensors (e.g., accelerometers, heart rate sensors, and skin temperature sensors) and converting the data into estimates of energy consumption[113,114]. These technologies can accurately collect and analyze physiological signals, enabling precise measurement of BMR, which, as a key component of human energy expenditure, is closely associated with CVD risk. Continuous monitoring of BMR through wearable calorimetry devices can detect abnormal energy metabolism in time and identify people at risk of CVDs in advance.

CONCLUSION

BMR is not only a core parameter of energy metabolism but also a crucial factor influencing cardiovascular health. It is closely associated with various factors such as body composition, thyroid function, mitochondrial efficiency, and the autonomic nervous system. BMR also affects CVD risk across different physiological stages in women, including the reproductive years, pregnancy, and menopausal transition.

Based on current research, a diagnostic and therapeutic framework centered on BMR offers new strategies for improving women’s cardiovascular health and reducing premature mortality. This framework includes precise BMR assessment, pharmacological interventions, lifestyle modifications, and the application of emerging technologies.

Aligned with the physiological characteristics of women across different life cycles, personalized intervention strategies based on this BMR-centered framework should be tailored to specific stages: (1) During the reproductive years, women can leverage the inherent cardiovascular protective effects of estrogen. They can maintain stable BMR by increasing lean body mass through regular resistance training (e.g., 2.5 sessions of compound movement training per week) and adopting a protein-pacing diet (4-6 meals daily, with at least 30% protein per meal), thereby balancing the metabolic risks potentially associated with elevated BMR; (2) During pregnancy, close monitoring of BMR elevation (which normally should reach 20%-30% to meet fetal energy needs) is essential. For women with pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension, personalized nutrition and blood pressure management plans should be developed based on BMR changes to reduce residual CVD risk in the postpartum period; (3) For menopausal women, after clarifying the mechanisms of BMR decline through thyroid function testing (e.g., timely intervention when TSH > 2.5 mIU/L) and vascular phenotyping assessment (e.g., enhanced monitoring when FMD < 6%), hormone-related interventions such as ERβ agonists can be rationally used. Meanwhile, consistent resistance training and a high-protein diet should be maintained to delay BMR decline and VAT accumulation. Drug development can focus on targets such as TH optimization (e.g., maintaining FT3 > 3.5 pg/mL), ERβ activation, and mitochondrial function improvement (e.g., UCPs). Lifestyle interventions should be implemented across all life cycles and combined with precision medical approaches to form a management model of “BMR monitoring - stage-specific intervention - long-term follow-up”.

Nevertheless, the theory and practice regarding the association between BMR and CVD still require further refinement. Future research should prioritize addressing two key issues: First, multi-center, large-sample prospective clinical trials need to be conducted to systematically verify the clinical effectiveness and safety of the BMR-centered diagnostic and therapeutic framework in women at different physiological stages, and to clarify its specific role in improving CVD prognosis. Second, an in-depth exploration of the cost-effectiveness of emerging technologies such as deep metabolic phenotyping and 13C-MFA is necessary, along with an assessment of their feasibility for popularization in primary medical institutions, to provide a basis for technological translation. Through such research, the theoretical system linking BMR to women’s CVD can be further improved, the implementation of precision prevention and control strategies can be promoted, and the gender gap in cardiovascular health can be narrowed.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conducted the literature search and collation, refined the manuscript language, and collectively completed the manuscript: Huang X, Li J, Huang Z, Wang Y

Jointly guided the research direction, proposed core questions, and reviewed literature screening and conclusions: He XY, Yu DQ

Responsible for editorial communication and coordination of responses to reviewer comments: He XY

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the following grants: the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong, China (2024A1515011451); the Chinese Cardiovascular Association-2023 TCM Fund (2023-CCA-TCM-033); and the Beijing Changjiang Pharmaceutical Development Foundation Wohua Research Fund (BYPDF2411213).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al.; GBD-NHLBI-JACC Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases Writing Group. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2982-3021.

2. Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1-25.

3. Vogel B, Acevedo M, Appelman Y, et al. The Lancet women and cardiovascular disease Commission: reducing the global burden by 2030. Lancet. 2021;397:2385-438.

4. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al.; INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937-52.

5. Ko SH, Kim HS. Menopause-associated lipid metabolic disorders and foods beneficial for postmenopausal women. Nutrients. 2020;12:202.

6. Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Deswal A, et al.; American Heart Association Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Hypertension; and Council on Quality and Outcomes Research. Contributory risk and management of comorbidities of hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic syndrome in chronic heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e535-78.

7. Mulder CL, Lassi ZS, Grieger JA, et al. Cardio-metabolic risk factors among young infertile women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2020;127:930-9.

8. Handelsman Y, Anderson JE, Bakris GL, et al. DCRM 2.0: multispecialty practice recommendations for the management of diabetes, cardiorenal, and metabolic diseases. Metabolism. 2024;159:155931.

9. Gerdts E, Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex differences in cardiometabolic disorders. Nat Med. 2019;25:1657-66.

10. Xu Y, Qiao J. Association of insulin resistance and elevated androgen levels with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS): a review of literature. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:9240569.

11. Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Vasic D, Kerkhof PLM. Cardiovascular implications of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, thyroid disease, and cardio-oncology in women. In: Kerkhof PLM, Miller VM, editors. Sex-specific analysis of cardiovascular function. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. pp. 471-88.

12. Henry CJ. Basal metabolic rate studies in humans: measurement and development of new equations. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:1133-52.

15. Maciak S, Sawicka D, Sadowska A, et al. Low basal metabolic rate as a risk factor for development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8:e001381.

16. Piaggi P, Thearle MS, Bogardus C, Krakoff J. Lower energy expenditure predicts long-term increases in weight and fat mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E703-7.

17. Ruggiero C, Metter EJ, Melenovsky V, et al. High basal metabolic rate is a risk factor for mortality: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:698-706.

18. Fabbri E, An Y, Schrack JA, et al. Energy metabolism and the burden of multimorbidity in older adults: results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:1297-303.

19. Zampino M, AlGhatrif M, Kuo PL, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. Longitudinal changes in resting metabolic rates with aging are accelerated by diseases. Nutrients. 2020;12:3061.

20. Ventura-Clapier R, Piquereau J, Garnier A, Mericskay M, Lemaire C, Crozatier B. Gender issues in cardiovascular diseases. Focus on energy metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866:165722.

21. Ward LJ, Nilsson S, Hammar M, et al. Resistance training decreases plasma levels of adipokines in postmenopausal women. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19837.

22. Chistiakov DA, Shkurat TP, Melnichenko AA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease: a brief review. Ann Med. 2018;50:121-7.

23. Riley M, Elborn JS, McKane WR, Bell N, Stanford CF, Nicholls DP. Resting energy expenditure in chronic cardiac failure. Clin Sci. 1991;80:633-9.

24. Poehlman ET, Scheffers J, Gottlieb SS, Fisher ML, Vaitekevicius P. Increased resting metabolic rate in patients with congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:860-2.

25. Zhao P, Han F, Liang X, et al. Causal effects of basal metabolic rate on cardiovascular disease: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13:e031447.

26. Chen K, Zhang Y, Zhou S, Jin C, Xiang M, Ma H. The association between the basal metabolic rate and cardiovascular disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2024;54:e14153.

27. Li Y, Zhai H, Kang L, Chu Q, Zhao X, Li R. Causal association between basal metabolic rate and risk of cardiovascular diseases: a univariable and multivariable Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2023;13:12487.

28. Alcantara JMA, Osuna-Prieto FJ, Plaza-Florido A. Associations between intra-assessment resting metabolic rate variability and health-related factors. Metabolites. 2022;12:1218.

29. Alcantara JMA, Osuna-Prieto FJ, Castillo MJ, Plaza-Florido A, Amaro-Gahete FJ. Intra-assessment resting metabolic rate variability is associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in middle-aged adults. J Clin Med. 2023;12:7321.

30. Ali N, Mahmood S, Manirujjaman M, et al. Hypertension prevalence and influence of basal metabolic rate on blood pressure among adult students in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2017;18:58.

31. Kim GH, Ryan JJ, Archer SL. The role of redox signaling in epigenetics and cardiovascular disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1920-36.

32. Miller VM, Duckles SP. Vascular actions of estrogens: functional implications. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:210-41.

33. Qiu Y, Chang S, Zeng Y, Wang X. Advances in mitochondrial dysfunction and its role in cardiovascular diseases. Cells. 2025;14:1621.

35. Li J, Li X, Song S, et al. Mitochondria spatially and temporally modulate VSMC phenotypes via interacting with cytoskeleton in cardiovascular diseases. Redox Biol. 2023;64:102778.

36. Kararigas G, Fliegner D, Forler S, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis reveals sex and estrogen receptor β effects in the pressure overloaded heart. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:5829-36.

37. Mason FE, Pronto JRD, Alhussini K, Maack C, Voigt N. Cellular and mitochondrial mechanisms of atrial fibrillation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2020;115:72.

38. Kang KW, Lee SK. Mechanistic insights into heart failure induction in ovariectomized rats: the role of mitochondrial dysfunction. Medicine. 2025;104:e43709.

39. Pavón N, Martínez-Abundis E, Hernández L, et al. Sexual hormones: effects on cardiac and mitochondrial activity after ischemia-reperfusion in adult rats. Gender difference. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;132:135-46.

40. Uribe-Alvarez C, Lira-Silva E, Morales-García L, et al. Estrogen degradation metabolites: some effects on heart mitochondria. J Xenobiot. 2025;15:170.

41. Peterson LR, Soto PF, Herrero P, et al. Impact of gender on the myocardial metabolic response to obesity. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:424-33.

42. Goveia J, Stapor P, Carmeliet P. Principles of targeting endothelial cell metabolism to treat angiogenesis and endothelial cell dysfunction in disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:1105-20.

43. Wilson C, Lee MD, Buckley C, Zhang X, McCarron JG. Mitochondrial ATP production is required for endothelial cell control of vascular tone. Function. 2023;4:zqac063.

44. Rutkai I, Dutta S, Katakam PV, Busija DW. Dynamics of enhanced mitochondrial respiration in female compared with male rat cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1490-500.

45. Li XT, Li XY, Tian T, et al. The UCP2/PINK1/LC3b-mediated mitophagy is involved in the protection of NRG1 against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Redox Biol. 2025;80:103511.

46. Wu H, Ye M, Liu D, et al. UCP2 protect the heart from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via induction of mitochondrial autophagy. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:15455-66.

47. Zheng Z, Lu H, Wang X, et al. Integrative analysis of genes provides insights into the molecular and immune characteristics of mitochondria-related genes in atherosclerosis. Genomics. 2025;117:111013.

48. Eyster KM. The estrogen receptors: an overview from different perspectives. In: Eyster KM, editor. Estrogen receptors. New York: Springer; 2016. pp. 1-10.

49. Li Y, Yang J, Li S, et al. N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2, a novel estrogen-targeted gene, is involved in the regulation of Na+/K+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32289-99.

50. Tham YK, Bernardo BC, Claridge B, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha deficiency in cardiomyocytes reprograms the heart-derived extracellular vesicle proteome and induces obesity in female mice. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2023;2:268-89.

51. Feng X, Wang C, Wu J. The role of estrogen and its membrane receptor G protein-coupled estrogen pathway in regulating glucose and lipid metabolism and imbalance of inflammatory response: the latest research progress. Chin J Geriatr. 2021;40:393-6.

52. Mahboobifard F, Pourgholami MH, Jorjani M, et al. Estrogen as a key regulator of energy homeostasis and metabolic health. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156:113808.

53. Nakamura Y, Miki Y, Suzuki T, et al. Steroid sulfatase and estrogen sulfotransferase in the atherosclerotic human aorta. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1329-39.

54. Johansson T, Karlsson T, Bliuc D, et al. Contemporary menopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease: swedish nationwide register based emulated target trial. BMJ. 2024;387:e078784.

55. Ceperuelo-Mallafré V, Llauradó G, Keiran N, et al. Preoperative circulating succinate levels as a biomarker for diabetes remission after bariatric surgery. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1956-65.

56. Osuna-Prieto FJ, Martinez-Tellez B, Ortiz-Alvarez L, et al. Elevated plasma succinate levels are linked to higher cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:151.

57. de Metz J, Sprangers F, Endert E, et al. Interferon-γ has immunomodulatory effects with minor endocrine and metabolic effects in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1999;86:517-22.

58. Zorrilla EP, Conti B. Interleukin-18 null mutation increases weight and food intake and reduces energy expenditure and lipid substrate utilization in high-fat diet fed mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;37:45-53.

59. Zhou Y, Wei Y, Wang L, et al. Decreased adiponectin and increased inflammation expression in epicardial adipose tissue in coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:2.

60. O'Brien LC, Graham ZA, Chen Q, Lesnefsky EJ, Cardozo C, Gorgey AS. Plasma adiponectin levels are correlated with body composition, metabolic profiles, and mitochondrial markers in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:863-72.

61. Adly NN, Abd-El-Gawad WM. Risk stratification among metabolically unhealthy obese in independent physically inactive aged women. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:1821-5.

62. Kizer JR, Benkeser D, Arnold AM, et al. Total and high-molecular-weight adiponectin and risk of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:255-63.

63. Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Circulation. 2001;103:1057-63.

64. Zhou Q, Xiang H, Li A, et al. Activating adiponectin signaling with exogenous AdipoRon reduces myelin lipid accumulation and suppresses macrophage recruitment after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:903-18.

65. Ehsan M, Singh KK, Lovren F, et al. Adiponectin limits monocytic microparticle-induced endothelial activation by modulation of the AMPK, Akt and NFκB signaling pathways. Atherosclerosis. 2016;245:1-11.

66. Okoth K, Chandan JS, Marshall T, et al. Association between the reproductive health of young women and cardiovascular disease in later life: umbrella review. BMJ. 2020;371:m3502.

67. Willemars MMA, Nabben M, Verdonschot JAJ, Hoes MF. Evaluation of the interaction of sex hormones and cardiovascular function and health. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2022;19:200-12.

68. Ning L, He C, Lu C, Huang W, Zeng T, Su Q. Association between basal metabolic rate and cardio-metabolic risk factors: evidence from a Mendelian randomization study. Heliyon. 2024;10:e28154.

69. Howard BV, Rossouw JE. Estrogens and cardiovascular disease risk revisited: the Women’s Health Initiative. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:493-9.

70. Florian M, Lu Y, Angle M, Magder S. Estrogen induced changes in Akt-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vasodilation. Steroids. 2004;69:637-45.

71. Armistead B, Johnson E, VanderKamp R, et al. Placental regulation of energy homeostasis during human pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2020;161:bqaa076.

72. Rabadia SV, Heimberger S, Cameron NA, Shahandeh N. Pregnancy complications and long-term atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2025;27:27.

73. Xiang D, Liu Y, Zhou S, Zhou E, Wang Y. Protective effects of estrogen on cardiovascular disease mediated by oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:5523516.

74. Lovejoy JC, Champagne CM, de Jonge L, Xie H, Smith SR. Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. Int J Obes. 2008;32:949-58.

75. El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, et al.; American Heart Association Prevention Science Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e506-32.

76. Reynolds HR, Bairey Merz CN, Berry C, et al. Coronary arterial function and disease in women with no obstructive coronary arteries. Circ Res. 2022;130:529-51.

77. Thurston RC, Chang Y, Barinas-Mitchell E, et al. Physiologically assessed hot flashes and endothelial function among midlife women. Menopause. 2018;25:1354-61.

78. Lam CSP, Voors AA, de Boer RA, Solomon SD, van Veldhuisen DJ. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: from mechanisms to therapies. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2780-92.

79. Samargandy S, Matthews KA, Brooks MM, et al. Arterial stiffness accelerates within 1 year of the final menstrual period: the SWAN heart study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:1001-8.

80. Fullmer S, Benson-Davies S, Earthman CP, et al. Evidence analysis library review of best practices for performing indirect calorimetry in healthy and non-critically ill individuals. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:1417-1446.e2.

81. Berger MM, De Waele E, Gramlich L, et al. How to interpret and apply the results of indirect calorimetry studies: a case-based tutorial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2024;63:856-69.

83. Bendavid I, Lobo DN, Barazzoni R, et al. The centenary of the Harris-Benedict equations: how to assess energy requirements best? Recommendations from the ESPEN expert group. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:690-701.

84. Brandi LS, Bertolini R, Calafà M. Indirect calorimetry in critically ill patients: clinical applications and practical advice. Nutrition. 1997;13:349-58.

85. Ukleja A, Skroński MK, Szczygieł B, Cebulski W, Słodkowski M. Indirect calorimetry, indications, interpretation, and clinical application. Postępy Żywienia Klinicznego. 2023;18:22-8.

86. Haugen HA, Chan LN, Li F. Indirect calorimetry: a practical guide for clinicians. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22:377-88.

87. Mtaweh H, Tuira L, Floh AA, Parshuram CS. Indirect calorimetry: history, technology, and application. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:257.

88. Sabounchi NS, Rahmandad H, Ammerman A. Best-fitting prediction equations for basal metabolic rate: informing obesity interventions in diverse populations. Int J Obes. 2013;37:1364-70.

89. Teixeira PFDS, Dos Santos PB, Pazos-Moura CC. The role of thyroid hormone in metabolism and metabolic syndrome. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2020;11:2042018820917869.

90. Mullur R, Liu YY, Brent GA. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:355-82.

91. Li ZZ, Yu BZ, Wang JL, Yang Q, Ming J, Tang YR. Reference intervals for thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroid hormones using the access TSH 3rd IS method in China. J Clin Lab Anal 2020;34:e23197.[PMID:31912542 DOI:10.1002/jcla.23197 PMCID:PMC7246370] Caution!.

92. Flammer AJ, Anderson T, Celermajer DS, et al. The assessment of endothelial function: from research into clinical practice. Circulation. 2012;126:753-67.

93. Bonetti PO, Pumper GM, Higano ST, Holmes DR Jr, Kuvin JT, Lerman A. Noninvasive identification of patients with early coronary atherosclerosis by assessment of digital reactive hyperemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2137-41.

94. Murthy VL, Reis JP, Pico AR, et al. Comprehensive metabolic phenotyping refines cardiovascular risk in young adults. Circulation. 2020;142:2110-27.

95. Riggs AJ, White BD, Gropper SS. Changes in energy expenditure associated with ingestion of high protein, high fat versus high protein, low fat meals among underweight, normal weight, and overweight females. Nutr J. 2007;6:40.

96. Dickerson RN, Roth-Yousey L. Medication effects on metabolic rate: a systematic review (part 1). J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:835-43.

97. Dickerson RN, Roth-Yousey L. Medication effects on metabolic rate: a systematic review (part 2). J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:1002-9.

98. Swedenborg E, Power KA, Cai W, Pongratz I, Rüegg J. Regulation of estrogen receptor beta activity and implications in health and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3873-94.

99. Barros RP, Gustafsson JÅ. Estrogen receptors and the metabolic network. Cell Metab. 2011;14:289-99.

100. Zahr T, Boda VK, Ge J, et al. Small molecule conjugates with selective estrogen receptor β agonism promote anti-aging benefits in metabolism and skin recovery. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14:2137-52.

101. Foryst-Ludwig A, Kintscher U. Metabolic impact of estrogen signalling through ERalpha and ERbeta. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;122:74-81.

102. Bi X, Forde CG, Goh AT, Henry CJ. Basal metabolic rate and body composition predict habitual food and macronutrient intakes: gender differences. Nutrients. 2019;11:2653.

103. Guasch-Ferré M, Wittenbecher C, Palmnäs M, et al. Precision nutrition for cardiometabolic diseases. Nat Med. 2025;31:1444-53.

104. Mitchell L, Wilson L, Duthie G, et al. Methods to assess energy expenditure of resistance exercise: a systematic scoping review. Sports Med. 2024;54:2357-72.

105. Wang X, Mao D, Xu Z, et al. Predictive equation for basal metabolic rate in normal-weight chinese adults. Nutrients. 2023;15:4185.

106. Wang Z, Bosy-Westphal A, Schautz B, Müller M. Mechanistic model of mass-specific basal metabolic rate: evaluation in healthy young adults. Int J Body Compos Res. 2011;9:147.

107. Arciero PJ, Edmonds R, He F, et al. Protein-pacing caloric-restriction enhances body composition similarly in obese men and women during weight loss and sustains efficacy during long-term weight maintenance. Nutrients. 2016;8:476.

108. Syngle V. Determinants of basal metabolic rate in Indian obese patients. Obesity Medicine. 2020;17:100175.

109. Huang HYR, Vitali C, Zhang D, et al. Deep metabolic phenotyping of humans with protein-altering variants in TM6SF2 using a genome-first approach. JHEP Rep. 2025;7:101243.

111. Long CP, Antoniewicz MR. High-resolution 13C metabolic flux analysis. Nat Protoc. 2019;14:2856-77.

112. Cheah YE, Young JD. Isotopically nonstationary metabolic flux analysis (INST-MFA): putting theory into practice. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018;54:80-7.

113. Magrini ML, Minto C, Lazzarini F, Martinato M, Gregori D. Wearable devices for caloric intake assessment: state of art and future developments. Open Nurs J. 2017;11:232-40.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].