Engineered stem cells and exosomes: novel atherosclerosis therapy

Abstract

Atherosclerosis remains a major global health challenge with limited therapeutic options for plaque regression. Stem cell therapy and stem cell-derived exosomes represent promising novel strategies for treating this disease. Different types of stem cells demonstrate therapeutic effects by modulating lipid metabolism, reducing inflammation, and improving endothelial function. However, challenges such as poor targeting, low maintenance times, and immunogenicity limit their clinical application. Recent advances focus on engineering these cells and their exosomes to overcome these barriers. Strategies include genetic modification, surface functionalization for targeted delivery, and hybrid nanoparticle design. Engineered exosomes also serve as efficient drug carriers for precise therapy. While clinical trials show potential, further validation of long-term efficacy and safety is needed. Integrating bioengineering with regenerative technology offers a new approach for atherosclerosis treatment.

Keywords

INTRODUCION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) have emerged as a leading global contributor to mortality and disability, with atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) demonstrating a particularly escalating disease burden in developing nations such as China and India. Notably, China has experienced a substantial increase in ASCVD-related mortality, accounting for 25% of total deaths nationally[1-3]. In etiological perspectives, atherosclerosis (AS) is a chronic disease characterized initially by endothelial dysfunction, followed by lipid deposition within the arterial walls. This process triggers a cascade involving macrophage-derived foam cell formation, proliferation of fibrous tissue, and abnormal proliferation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs), ultimately leading to the development of atherosclerotic plaques, vascular narrowing, and impaired blood flow[4]. AS is characterized not only by lipid deposition but also by a concurrent vascular inflammatory response[5,6].

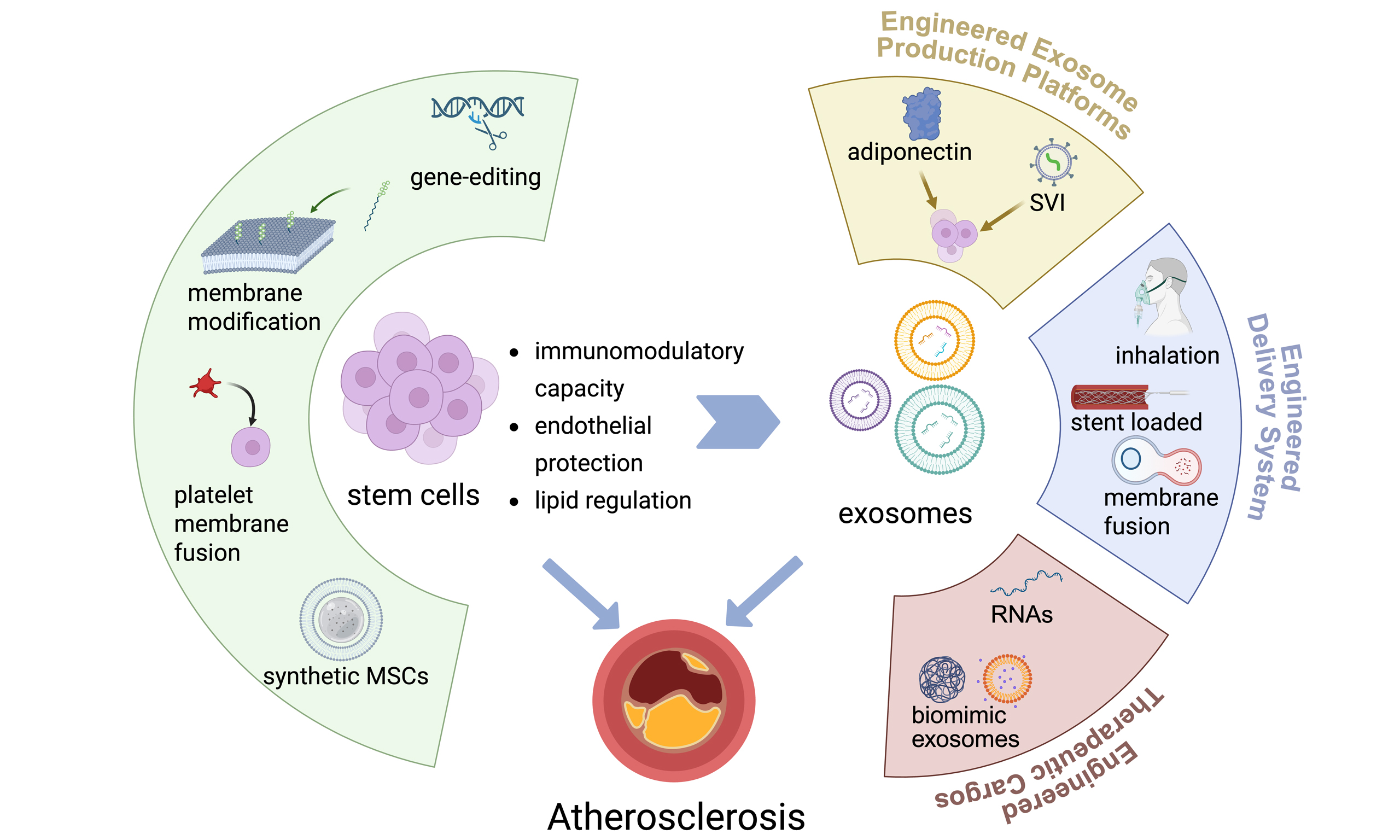

AS, a chronic, progressive vascular disease, represents a huge therapeutic challenge due to its complex, multifactorial origins. Current therapeutic strategies, primarily focused on lipid management (e.g., statins) and inflammation modulation, effectively slow progression and stabilize plaques in many cases. However, they often fall short of achieving significant plaque regression or fully reversing established disease[6-9]. Critically, the downstream consequences of advanced or unstable AS plaques are devastating: plaque rupture or erosion can trigger acute thrombotic events, leading directly to myocardial infarction (MI), ischemic stroke, or critical limb ischemia (CLI). Despite advances in surgical and interventional techniques (such as stenting and bypass grafting) that address vital obstructions, these interventions are inherently reactive, treating the end-stage complications rather than the underlying disease process or preventing the progression of AS to such catastrophic outcomes[10]. This persistent gap in achieving true disease modification and preventing life-altering thrombotic complications underscores the compelling need for novel therapeutic approaches. Stem cell-based therapies, for instance, offer distinct advantages in modulating the microenvironment and enabling effective disease prevention, fundamentally altering the atherosclerotic disease course [Figure 1]. Stem cells are defined by two principal characteristics: their unique ability to self-renew and their potential to differentiate into one or more specialized cell types[11]. Stem cells exist both in embryos and in adult organisms. For example, embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are typical representatives of pluripotent stem cells, while adult stem cells (ASCs) include hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), neural stem cells (NSCs), and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), among others[12,13]. These stem cells, including first-generation types represented by MSCs and HSCs, as well as second-generation types such as ESCs and iPSCs, serve as germline cells employed in cell-based therapies[14].

Figure 1. Mechanisms of atherosclerosis and putative therapeutic targets of stem cells and exosomes. Schematic illustration of the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, highlighting key stages from endothelial dysfunction to advanced plaque formation, and the potential therapeutic mechanisms of stem cells and exosomes including promoting endothelial repair, modulating inflammation, and hindering foam cell formation. Created in BioRender. Yang Z (2025) https://BioRender.com/jun6d4h. LDL: low-density lipoprotein; NETs: neutrophil extracellular traps; oxLDL: oxidized low-density lipoprotein; SR-A1: scavenger receptor class A type 1; Treg: regulatory T cell;

Stem cell therapy, spanning from the pioneering era of HSC transplantation to contemporary approaches of utilizing directed differentiation of stem cells into cardiomyocytes, has garnered sustained research interest as an emerging therapeutic modality in CVD management[15,16]. Accumulating evidence from ongoing research suggests that the therapeutic benefits of stem cells may be partially attributed to exosome-mediated paracrine mechanisms, rather than the long-term engraftment of transplanted cells[17,18].

Despite emerging research on stem cells and stem cell-derived exosomes in ASCVD, both therapeutic modalities face common limitations such as poor targeting efficiency and immunogenic clearance, as well as distinct technical challenges[18-23]. Current reviews primarily focus on the diverse sources of stem cells and exosomes in regenerative therapies for AS, their involvement in AS pathogenesis or their use as therapeutic agents, and the therapeutic mechanisms underlying their functions. However, few reviews provide detailed descriptions of engineering approaches to modify stem cells and exosomes based on the pathological features of AS, aiming to enhance their biological efficacy in preclinical settings. Therefore, this review details stem cell sources (including MSCs, progenitor cells, etc.) used for ASCVD treatment and explores other cell types that are proven effective in other diseases and have therapeutic potential for ASCVD. Furthermore, it introduces the therapeutic effects and underlying mechanisms of exosomes derived from various stem cell sources in ASCVD. Additionally, special focus is placed on engineering strategies to modify stem cells and exosomes, endowing them with superior therapeutic properties compared to their native counterparts. Through this comprehensive discussion, this review aims to assist readers in exploring and designing more advanced, translatable novel therapies based on existing stem cell technologies.

STEM CELL THERAPY IN ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Stem cells, as new therapeutic agents, demonstrate broad therapeutic potential across various diseases, including neurological disorders[24], autoimmune diseases[25], fibrosis[26,27], while also exhibiting unique value in CVDs. MSCs, as a type of stem cell widely distributed in tissues such as bone marrow, perinatal tissues, adipose tissue, and other sources, have been extensively utilized in regenerative medicine research over the past few decades[28]. Research reveals that MSCs exert therapeutic effects through multiple mechanisms: possessing not only differentiation potential towards vascular endothelial cells (ECs) (based on their developmental homology)[29], but also mediating immune regulation through secretion of cytokines, chemokines, and other bioactive molecules. These characteristics offer a theoretical basis for treating vascular diseases such as AS [Table 1]. Consistently, multiple preclinical studies have demonstrated that stem cell administration significantly alleviates atherosclerotic lesions in animal models, supporting their potential therapeutic value in vivo [Table 2].

Therapeutic stem cell candidates for atherosclerosis

| Types of stem cell | Cell sources | Functional effects | Authors |

| MSC | Umbilical cord (Wharton’s jelly) | Lipid metabolism | Li et al.[30] |

| Adipose | Lipid metabolism; anti-inflammation | Li et al.[31] Rehman et al.[32] | |

| iPSC | Inflammatory modulation | Shi et al.[33] | |

| Bone marrow | Inflammatory modulation | Lin et al.[34] | |

| EPC | Bone marrow | Reverse endothelial oxidative damage | Li et al.[35] |

Summary of preclinical studies involving stem cell-based therapies

| Types of stem cell | Cell sources | Experimental model | Dosage | Reduction of atherosclerotic plaque area | Reference |

| MSC | adipose | Rabbit, HFD | 6 × 106, i.v., every 2 weeks for 3 months | ~20% | [31] |

| iPSCs | Mouse, ApoE-/-, HFD | 2 × 106, i.v., every 7-10 days for 12 weeks | ~75% | [33] | |

| Bone marrow | Mouse, ApoE-/-, HFD | 2 × 105, i.v., single injection | ~10% | [36] | |

| EPC | Bone marrow | Rat, HFD | 2 × 106, i.v., single injection | - | [35] |

Animal studies have demonstrated that cessation of high-fat, high-cholesterol dietary regimens significantly attenuates the progression of atherosclerotic lesions[37]. The pathological cascade initiates with the pathological accumulation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) molecules in the subendothelial space, triggering intimal thickening that progresses to foam cell formation and the development of lipid-rich cores encapsulated by fibrous plaques[38,39]. Current clinical evidence confirms that lipid-targeted therapeutic interventions can effectively mitigate AS progression. Studies demonstrate that human umbilical

Multiple cardiovascular risk factors trigger molecular signaling pathways in endothelial cells, leading to upregulated expression of chemokines, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and adhesion molecules. This molecular activation initiates a pathological cascade of endothelial dysfunction, ultimately driving atherosclerotic progression[40-42]. Emerging experimental evidence demonstrates that MSCs exert endothelial protective effects through paracrine secretion of bioactive factors and modulation of inflammatory microenvironments. Initial studies showed that dermal-derived MSCs activate endothelial functions via paracrine mechanisms[43]. MSCs can secrete Wingless/Int (Wnt) proteins to activate the β-catenin-mediated Wnt signaling pathway to reduce EC apoptosis[36]. Other investigations revealed that huc-MSCs can specifically rectify aberrant phosphorylation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway and downregulate overexpression of critical regulators, including MAP kinase-interacting

The therapeutic effectiveness of MSCs primarily stems from their immunomodulatory capacity, though molecular pathways underlying inflammatory regulation exhibit marked heterogeneity across MSC populations from distinct tissue origins. Research reveals that bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs) modulate atherosclerotic progression through dynamic secretome alterations under pathological conditions. Exogenous BMSC administration elevates the regulatory T cell (Treg)/CD4 positive (CD4+) T cell ratio and drives macrophage polarization toward the M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype, thereby suppressing monocyte infiltration and vascular inflammation[34]. Notably, AD-MSCs exert anti-atherogenic effects predominantly through alternatively activated macrophage (M2 macrophage) polarization, with transcriptomic analyses demonstrating their superior capability in inducing anti-inflammatory cytokine production compared to other MSC subtypes[46]. Huc-MSC-derived exosomal miR-100-5p alleviates AS progression by inhibiting cellular processes and inflammation in eosinophils via the Frizzled 5 (FZD5)/Wnt/β-catenin pathway[47]. Cutting-edge advancements utilize human iPSC-derived MSCs (iPSC-MSCs), which exhibit extended in vivo persistence, enhanced proliferative potential, and improved genetic stability[33]. These cells demonstrate significant plaque-stabilizing effects in multimodal imaging assessments via targeted modulation of NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3) inflammasome activity and interleukin (IL)-1β signaling pathways.

Extensive preclinical studies have investigated the potential of MSCs as a therapeutic strategy for AS. In light of this, other cell types that share similar developmental origins with MSCs or demonstrate comparable biological functions have also been explored for AS treatment. Taking EPCs as an example, these circulating precursor cells have been shown to enhance post-ischemic tissue angiogenesis and vascular repair[48,49]. Notably, the mobilization of endogenous EPCs has been recognized as one of the mechanisms through which lipid-lowering medications such as statins, ezetimibe, and fibrates exert their therapeutic effects[50]. While in vitro expansion and large-scale culture of autologous EPCs may represent a promising research direction, this approach potentially carries the risk of increased atherosclerotic plaque instability associated with EPC activity. Human amniotic epithelial stem cells (hAESCs) have emerged as a research focus in regenerative medicine due to their multifaceted biological advantages, including minimal tumorigenic risk, robust paracrine activity, potent immunomodulatory properties, and absence of ethical constraints[51-53]. Preclinical studies demonstrate their therapeutic efficacy in fibrosis resolution[54], immune dysregulation correction[55,56], and tissue regeneration. Notably, their demonstrated potential in MI treatment through angiogenesis modulation and inflammation suppression highlights their translational value, suggesting that hAESCs could be used for AS treatment.

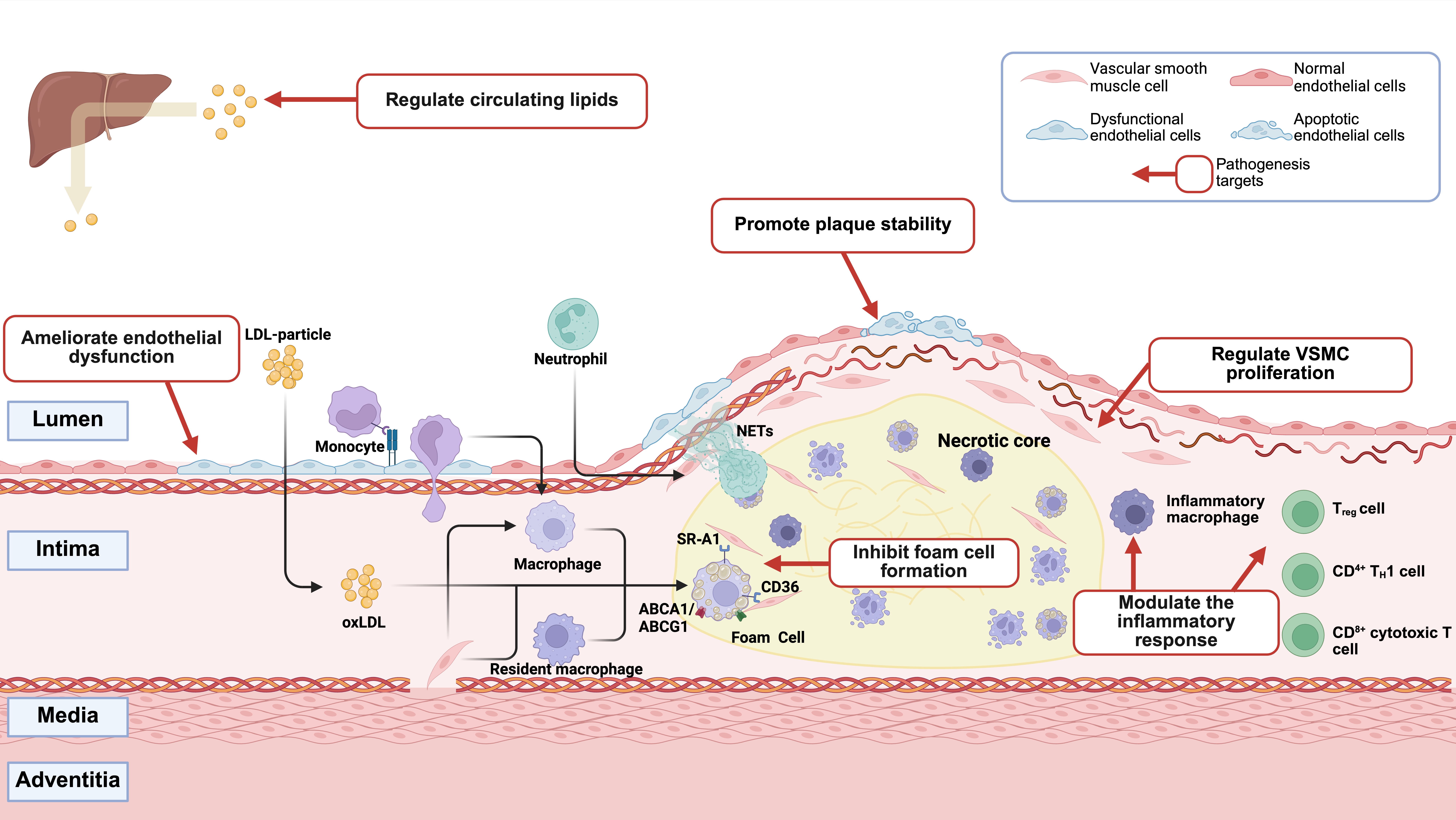

ENGINEERED STEM CELLS

Although stem cells, symbolized by MSCs and their derivative cell therapies, have demonstrated significant potential in the treatment of AS - particularly the unique vascular homing capacity exhibited by BMSCs[57] - their clinical application remains constrained by inherent technical limitations of stem cell therapies. These challenges include heterogeneity in therapeutic efficacy, potential risks of tumorigenicity, short-term survival of transplanted cells in vivo, and technical obstacles in cell product transportation and long-term preservation[58]. Consequently, current research focuses on engineering stem cells to develop therapeutics or treatment protocols that address these limitations [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Overcoming stem cell limitations: engineering strategies for enhanced therapeutic efficacy. Stem cell-based therapies for atherosclerosis face intrinsic limitations, including heterogeneity, tumorigenic potential, short in vivo retention, and difficulties in long-term storage. Targeted engineering strategies are correspondingly proposed to overcome these barriers, such as enhancing immunomodulatory functions via PD-L1 overexpression, promoting cholesterol efflux through membrane engineering, and improving stability and targeting precision by employing an artificial nanocarrier. This conceptual framework provides a visualized correlation between key limitations and rational engineering solutions, offering guidance for the development of next-generation stem cell therapeutics in atherosclerosis. Created in BioRender. Yang Z (2025) https://BioRender.com/whkit3r. MSC: Mesenchymal stem cell; PLGA: poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid); Treg: regulatory T cell; PD-L1: programmed death ligand 1; IL-10: interleukin-10; Akt (PKB): protein kinase B.

Gene-editing therapeutics have demonstrated transformative potential in managing metabolic and cardiovascular disorders. For example, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-mediated targeting of hepatic proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) has been clinically validated to reduce circulating LDL-C levels in familial hypercholesterolemia patients, thereby modulating atherosclerotic progression through lipid metabolic regulation[59,60]. This concept extends to MSC engineering, where genetic modification enhances their paracrine activity, immunomodulatory capacity, and lipid metabolism-related signaling[61,62]. Notably, recent evidence highlights that CVD-oriented MSC engineering strategies can further potentiate anti-atherosclerotic efficacy, providing a promising framework for precision MSC therapy in AS[63].

Beyond conventional approaches, several engineered cell strategies show enhanced therapeutic potential for AS. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified macrophages have been engineered to specifically target and engulf CD47-expressing phagocytosis-resistant apoptotic cells[64]. These CAR macrophages are further surface-functionalized with reactive oxygen species (ROS)-responsive therapeutic nanoparticles targeting the liver X receptor pathway, thereby improving their effector activity. The synergistic integration of CAR technology and nanoparticle engineering activates lipid efflux pumps, enhances cellular debris clearance, and reduces inflammatory responses, demonstrating augmented anti-atherosclerotic efficacy. Another innovative chimeric antigen receptor-macrophage (CAR-M) construct strategy involves dual overexpression of C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) and

Recent studies have developed exosome-mimetic nanovesicles derived from mechanically extruded MSCs, and further engineered platelet membrane-coated exosome-mimetic nanovesicles (P-ENVs) that synergistically enhance atherosclerotic plaque targeting through biomimetic delivery while attenuating lipid accumulation via ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABC) A1/ABCG1-mediated cholesterol efflux, demonstrating dual therapeutic efficacy and biosafety for clinical translation in AS management[67]. Synthetic MSCs have been utilized in treating acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in mice. By encapsulating MSC-derived secretory factors within poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres and coating their surface with MSC membranes, these engineered constructs effectively promote angiogenesis. Compared to natural MSCs, synthetic MSCs demonstrate enhanced therapeutic efficacy while offering the advantage of improved storage stability[68].

STEM CELL-DERIVED EXOSOMES

Given the limitations associated with direct stem cell administration and the recognition that a significant portion of the therapeutic efficacy of stem cells is attributed mainly to their secretome, among which exosomes serve as principal bioactive mediators, research focus has shifted toward extracellular vesicles. It should be emphasized that exosomes and ectosomes, characterized by distinct biogenesis pathways, both function as evolutionarily conserved signaling platforms that coordinate intercellular communication through targeted delivery of proteins, nucleic acids, and other bioactive cargoes[69,70]. Despite ongoing debate regarding the classification and definition of extracellular vesicles in recent years, this study operationally defines exosomes as 50-150 nm vesicles secreted by cells, maintaining this standardized designation throughout the manuscript. As a cell-free therapeutic modality, exosomes have been utilized to treat diverse pathologies and ameliorate aging-related adverse physiological conditions. CVDs such as AS exhibit intrinsically linked pathogenic mechanisms with aging. Stem cell-derived exosomes exert multimodal therapeutic effects against AS through coordinated regulation of lipid metabolism, inflammatory responses, and endothelial homeostasis[70-76].

To date, exosomes derived from multiple cellular sources - including ESCs, iPSCs, multipotent and unipotent ASC lineages such as MSCs, cardiac stem cells (CSCs) including cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) and cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs), as well as EPCs - have been investigated for cardiovascular protection[77-79]. miR-199a-3p within EPC-derived exosomes is believed to bind the specificity protein 1 (SP1), thereby reducing endothelial cell ferroptosis[80]. MSC-derived exosomes containing miR-146a and miR-342-5p exert therapeutic effects on vascular endothelial dysfunction through distinct molecular mechanisms: miR-146a mediates anti-senescence and pro-angiogenic effects by suppressing proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src (Src) kinase phosphorylation[81]. At the same time, miR-342-5p ameliorates endothelial injury through modulation of the protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 12b (PPP1R12b) signaling pathway[82]. Furthermore, MSC-derived exosomes can restore mitochondrial function in endothelial cells and improve angiogenesis by inhibiting neutrophil extracellular trap (NET)-induced endothelial ferroptosis[83]. These protective effects are demonstrated in AS.

Stem cell-derived exosomes also alleviate AS by modulating inflammation and improving lipid metabolism. Specifically, miR-21a-5p and miR-let-7 within MSC-derived exosomes promote M2 macrophage polarization and reduce macrophage infiltration, thereby mitigating AS[84,85]. CDCs can transfer miR-181b to macrophages, altering their polarization state and enhancing cardioprotective effects[86] [Table 3]. Furthermore, human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes regulate lipid metabolism via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-mediated signaling pathways in hepatocytes, specifically, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα)/carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT-1A) pathway (promoting fatty acid oxidation) and the sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c)/fatty acid synthase (FASN) pathway (reducing fatty acid synthesis)[87].

Key microRNAs carried by stem cell-derived exosomes and their regulatory roles in atherosclerosis

| Source | miRNA | Target gene | Signaling pathway | Biological effect | Reference |

| MSC | miR-146a | Src | Src/VE-Cad Caveolin-1 | Reduce endothelial oxidative stress-induced senescence | [81] |

| MSC | miR-let7 | HMGA2 | HMGA2/NF-κB | M2 macrophage polarization | [84] |

| MSC | miR-21a-5p | KLF6/ERK2 | - | Macrophage polarization and infiltration | [85] |

| EPC | miR-199a-3p | SP1 | - | Ferroptosis of endothelial cells | [80] |

| CDC | miR-181b | PKCδ | - | Macrophage polarization | [86] |

ENGINEERING OF STEM CELL-DERIVED EXOSOMES

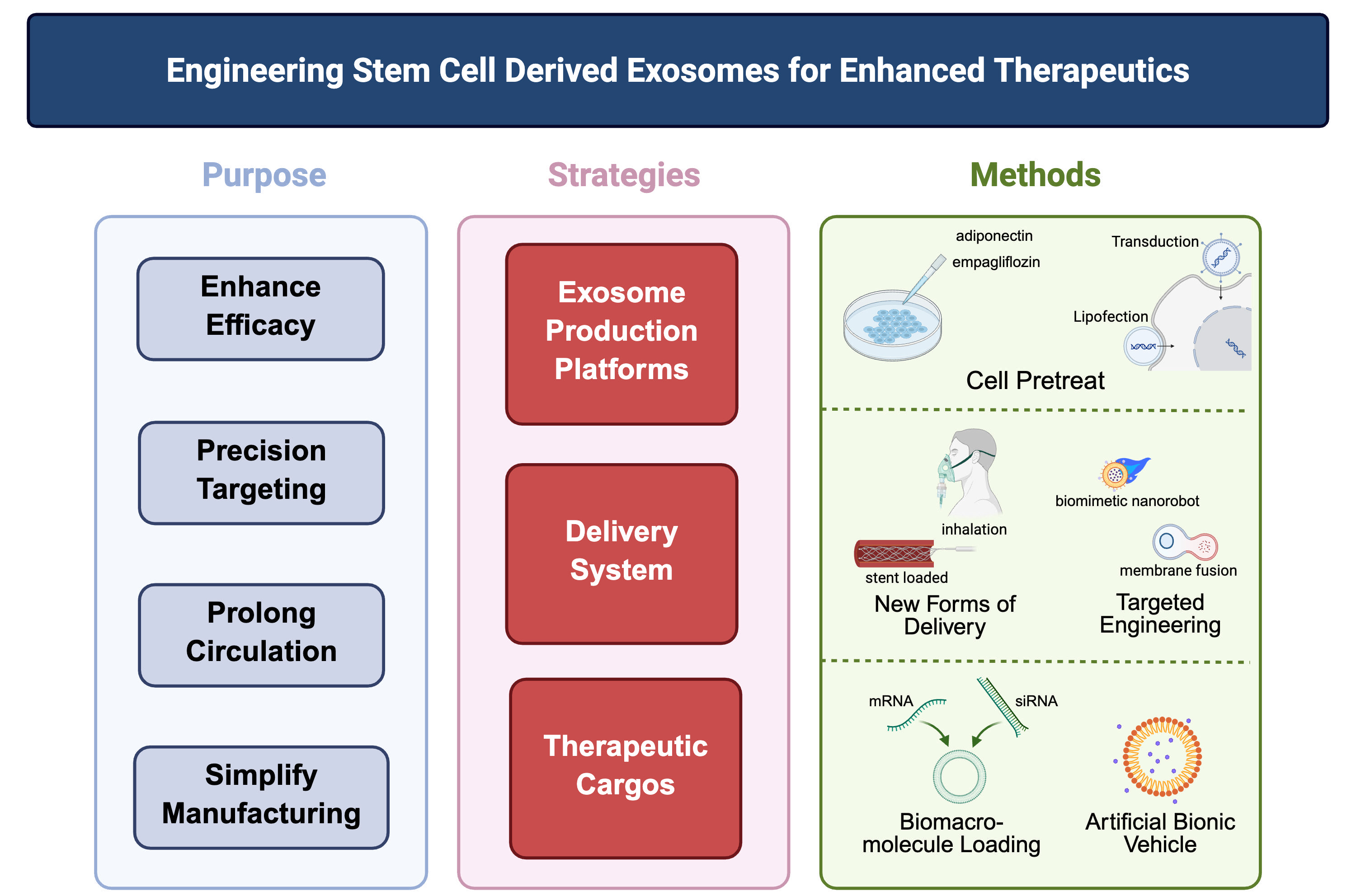

While natural exosomes exhibit inherent therapeutic potential for AS as discussed above, their clinical translation faces significant challenges, including limited targeting specificity, variable cargo loading efficiency, and insufficient yield for therapeutic applications. To overcome these limitations, engineered exosomes have emerged as a transformative strategy. Through deliberate modifications of their production platforms, delivery systems, and therapeutic cargos, exosomes can be functionally enhanced to achieve precise targeting, controlled release, and optimized therapeutic efficacy for AS pathogenesis[88-90] [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Engineering exosomes, from therapeutic goals to design strategies and technical approaches. Following the rationale of “therapeutic purpose/strategic design/technical approach,” the schematic outlines the central engineering paradigms for stem cell-derived exosomes in the treatment of atherosclerosis. The strategies span three interconnected domains: optimization of production platforms (e.g., empagliflozin preconditioning), refinement of delivery modalities (e.g., inhalable preparations, stent-anchored sustained-release systems, and biomimetic nanorobots achieved through membrane fusion), and efficient loading of therapeutic cargos (e.g., mRNA, siRNA, and small-molecule agents). These integrated engineering approaches address the intrinsic shortcomings of native exosomes, including limited targeting accuracy, low production efficiency, and suboptimal cargo encapsulation, thereby establishing a conceptual basis for precision exosome therapeutics in atherosclerosis. Created in BioRender. Yang Z (2025) https://BioRender.com/vt6f36k.

Engineered exosome production platforms

Engineering strategies for exosome modification often focus on reprogramming the parent stem cells. By manipulating these cells to alter their physiological states, researchers can induce them to secrete exosomes with modified properties. For example, adiponectin binds to T-cadherin on MSCs, stimulating the synthesis and secretion of MSC-derived exosomes. Genetically enhancing plasma adiponectin secretion consequently amplifies the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs[91]. Pretreating MSCs with empagliflozin also enhances the angiogenic capacity of their secreted exosomes via the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)/protein kinase B (Akt)/vascular endothelial growth factor(VEGF) signaling pathway[92].

Another common engineering approach involves genetic modification of stem cells using viral vectors or plasmids to express therapeutic biomolecules. For instance, MSCs transfected to overexpress Akt secrete exosomes that promote angiogenesis in vitro and improve cardiac function[93].

Engineered delivery system

Strategically selected routes of administration can enhance the therapeutic efficacy of exosomes. Exosome biodistribution and therapeutic outcomes are highly dependent on delivery methods[94]. Beyond intravenous injection, which is the most common approach, inhaled stem cell exosomes have been shown to promote post-myocardial infarction repair by downregulating CD36 expression to modulate compensatory glucose utilization in the heart[95]. Additionally, an ROS-responsive exosome-eluting vascular stent was developed to release MSC-derived exosomes post-implantation, conditioning macrophage polarization and reducing vascular/local inflammation[96].

Engineering exosomes for enhanced targeting represents another key strategy. Surface functionalization with targeting molecules improves specificity, as demonstrated in applications such as peptide-modified huc-MSC exosomes for enhanced liver fibrosis targeting[97]. Membrane fusion techniques also enable targeted exosome construction. For instance, the engineered biomimetic nanorobot integrates dual mechanisms: macrophage-derived EVs (IL-4-stimulated) reprogram macrophages toward M2 efferocytic phenotypes, while Src Homology 2 Domain-Containing Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase-1 (SHP1) small interfering RNA (siRNA)-loaded liposomes block CD47-signal-regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) “don’t eat me” signals. Driven by urease motors, this system significantly enhances targeted delivery, reactivates efferocytosis in atherosclerotic plaques, and reduces carotid/coronary plaque burden[98].

Platelet-based delivery systems leverage natural macrophage interactions and immune evasion properties, showing promise for AS therapy[99-101]. Notably, co-extruded exosome-platelet membrane hybrids demonstrate significant efficacy in AS animal models by modulating lipid metabolism[102,103].

Engineered therapeutic cargos

Stem cell-derived exosomes serve as novel drug delivery systems, offering innovative strategies for AS therapeutics. Beyond their inherent therapeutic potential, their value as highly biocompatible carriers lies in accommodating diverse cargoes - including drugs, RNAs, and proteins - while exhibiting lower cytotoxicity than conventional delivery vectors[104,105]. For instance, engineered exosomes pre-loaded with functional

However, drug loading processes often compromise exosomal structural integrity. Regardless of engineering strategies, the impact of manipulations on vesicle integrity must be evaluated. To address this, current research is pivoting toward artificial exosome-mimetics (e.g., liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles), which retain native exosome functions through biomimetic design while circumventing structural fragility, thereby enabling efficient drug loading[108].

CLINICAL TRANSLATION OF STEM CELL-BASED THERAPEUTICS IN AS

Significant progress has been made in the clinical application of stem cells and their exosomes for treating AS. According to ClinicalTrials.gov registry data, 80 clinical trials investigating stem cell or exosome therapies for AS and peripheral artery disease have been currently registered. Stem cell therapies have demonstrated clinical advancements in treating vascular diseases such as arteriosclerosis[109] and renovascular disease[110]. However, a substantial portion of these trials focus on vascular repair applications such as CLI, while clinical data specifically targeting AS with various stem cell types remain scarce [Table 4]. Despite these encouraging developments, stem cell therapy for AS still faces several challenges. Although numerous studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of stem cell-based therapies in AS, a substantial gap remains between preclinical findings and clinical outcomes. Among the reported clinical trials, only four (NCT01663376, NCT02685098, NCT01595776, and NCT00883870) have reported clear therapeutic benefits, with improvements in pathological parameters and evidence supporting the safety of stem cell administration. Nevertheless, one trial was prematurely terminated due to a high incidence of karyotypic abnormalities in MSCs (NCT03455335). These observations highlight the necessity for cautious and comprehensive evaluation of stem cell applications in AS, as the clinical results have yet to fully reproduce the promising effects observed in preclinical studies.

Clinical filing for stem cell-based treatment of atherosclerosis-related diseases

| Registration number | Treatment | Conditions | Phases | Result | Country | |

| NCT01257776 | MSCs | AMSC | CLI | 1|2 | Completed | Spain |

| NCT01663376 | AMSC | CLI | N/A | Completed | South Korea | |

| NCT01745744 | AMSC | CLI | 2 | Completed | Spain | |

| NCT00643981 | BMSC | AS | 1 | Completed | Netherlands | |

| NCT02685098 | BMSC | AS | 1 | Completed | United States | |

| NCT00790764 | BMSC | AS | 2 | Suspended | United States | |

| NCT00987363 | BMSC | CLI | 1|2 | Completed | Spain | |

| NCT01351610 | BMSC | CLI | 1|2 | Completed | Germany | |

| NCT01484574 | BMSC | CLI | 2 | Completed | India | |

| NCT01867190 | BMSC | CLI | 2 | Completed | United States | |

| NCT02336646 | BMSC | CLI | 1 | Completed | Taiwan, China | |

| NCT03455335 | BMSC | CLI | 1 | Completed | Ireland | |

| NCT00548613 | Progenitor cells | BMPC | AS | 1 | Completed | Netherlands |

| NCT01595776 | EPC | CLI | 1|2 | Completed | Italy | |

| NCT02454231 | EPC | CLI | 2|3 | Completed | Italy | |

| NCT01436123 | Other stem cells | AS | 1 | Terminated | Russia | |

| NCT00883870 | CLI | 1|2 | Completed | India | ||

Key issues include the source and safety of stem cells, as cells derived from different tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord blood) possess distinct properties that require further validation. Additionally, precise cell delivery and homing to the lesion site, along with ensuring long-term survival and functional integration of the cells in vivo, represent significant research hurdles[111]. Furthermore, the

Identifying and selecting optimal cell sources represents the primary challenge for translating stem cell and derived exosome therapies into clinical applications for AS and related diseases, with no consensus yet established. Furthermore, systematic research on optimal dosing regimens and source-specific efficacy assessments of stem cells remains notably insufficient. Consequently, resolving cell source selection, optimizing dosing protocols, and establishing precise efficacy evaluation frameworks constitute critical bottlenecks and urgent priorities for advancing reliable clinical translation in this field.

EMERGING FRONTIERS AND TRANSLATIONAL CHALLENGES

With the continuous advancement of regenerative medicine technologies, stem cell therapy for AS is poised to achieve further breakthroughs. Future development trends may encompass the diversification and optimization of stem cell sources to enhance safety and efficacy, the implementation of combination strategies integrating stem cells with other treatments such as pharmacotherapy or gene therapy to improve overall effectiveness, and deeper research into exosome-based therapies leveraging their critical roles in AS pathogenesis for more precise interventions.

To advance the precision of stem cell-based therapies for AS, refined optimization strategies are imperative: omics-guided stem cell stratification (e.g., single-cell RNA sequencing) enables identification of therapeutically potent subpopulations for enhanced efficacy[113], and organ-on-a-chip platforms mitigate clinical translation uncertainties through preemptive tumorigenicity profiling[114]. Notably, while

Similarly, exosomes are encountering challenges in clinical translation. For instance, establishing universally applicable industry standards that accommodate diverse cellular sources to achieve standardized production remains an unresolved issue. Although substantial progress has been made in large-scale exosome production in recent years, the heterogeneity of cell sources necessitates targeted optimization of culture medium formulations, customized production systems, and manufacturing protocols[117,118].

In addition, several practical and regulatory barriers must be addressed before engineered stem cells and exosomes can be safely and effectively applied in clinical settings. Among these, good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compliant manufacturing, product consistency, evolving regulatory frameworks, and immune compatibility represent key determinants of successful translation. Establishing scalable and standardized production pipelines that preserve the biological activity and molecular composition of engineered products is essential for ensuring reproducibility and patient safety. Meanwhile, global regulatory agencies are continuously updating guidelines for advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), underscoring the importance of transparent documentation, traceability, and comprehensive risk/benefit assessment during product development and testing. In June 2025, mainland China formally began to include cell therapy, gene therapy, and exosome-based products under the regulatory umbrella of ATMPs via a draft framework issued by the Center for Drug Evaluation under National Medical Products Administration (NMPA), marking a significant step toward unified supervision of biotherapeutics. Furthermore, immunological compatibility, particularly in the context of allogeneic or genetically modified sources, warrants careful preclinical evaluation and adaptive clinical trial designs to mitigate immune-related adverse events. Tackling these multifaceted challenges will require close interdisciplinary collaboration among cell biologists, bioengineers, clinicians, and regulatory experts to ensure the safe and reproducible translation of engineered stem cell and exosome therapies to the clinic.

Moreover, novel therapeutic targets and mechanisms uncovered through stem cell and exosome research have not only deepened our understanding of disease pathology but also provided pivotal insights toward developing innovative therapeutics (e.g., nucleic acid drugs) and advanced delivery systems. Building on these advances, the development of personalized treatment regimens tailored to individual patient profiles is poised to enhance therapeutic specificity and efficacy. To ensure the safe implementation of such strategies, establishing standardized technical protocols and robust regulatory frameworks will be imperative. Ultimately, the integration of synthetic biology and engineering methodologies into stem cell/exosome therapies will be critical for advancing effective AS management.

CONCLUSION

In summary, stem cells and their exosomes represent innovative therapeutic tools that offer new promise for the clinical management of AS. Recent advances have successfully applied novel engineering technologies to overcome inherent biological limitations of natural stem cells and exosomes, such as suboptimal targeting precision, rapid immune clearance, safety and ethical concerns, and formulation and storage challenges. Nevertheless, the application of these therapies in AS treatment remains constrained by insufficient clinical data. Therefore, integrating advanced bioengineering strategies with expanded clinical trials constitutes a critical direction for advancing stem cell-based interventions against AS.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The schematic figures in this publication were created with https://BioRender.com, and publication rights were obtained accordingly.

Authors’ contributions

Wrote and edited the manuscript: Yang Z

Conceived and reviewed the manuscript: Yu L, Li J

All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LMS26H010002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82370450, 82300296), and the China Manned Space Flight Technology Project Chinese Space Station (KJZ-YY-NSM0617, YYWT-0901-EXP-06).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Song P, Fang Z, Wang H, et al. Global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e721-9.

3. Zhao D, Liu J, Wang M, Zhang X, Zhou M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: current features and implications. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:203-12.

4. Jebari-Benslaiman S, Galicia-García U, Larrea-Sebal A, et al. Pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3346.

5. Hansson GK, Libby P, Tabas I. Inflammation and plaque vulnerability. J Intern Med. 2015;278:483-93.

6. Kong P, Cui ZY, Huang XF, Zhang DD, Guo RJ, Han M. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:131.

7. Mandaglio-Collados D, Marín F, Rivera-Caravaca JM. Peripheral artery disease: update on etiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin (Barc). 2023;161:344-50.

8. Papafaklis MI, Koros R, Tsigkas G, Karanasos A, Moulias A, Davlouros P. Reversal of atherosclerotic plaque growth and vulnerability: effects of lipid-modifying and anti-inflammatory therapeutic agents. Biomedicines. 2024;12:2435.

9. Liu Y, Lu K, Zhang R, et al. Advancements in the treatment of atherosclerosis: from conventional therapies to cutting-edge innovations. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2024;7:3804-26.

10. Badimon L, Vilahur G. Thrombosis formation on atherosclerotic lesions and plaque rupture. J Intern Med. 2014;276:618-32.

11. Saba JA, Liakath-Ali K, Green R, Watt FM. Translational control of stem cell function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:671-90.

12. Abou-Saleh H, Zouein FA, El-Yazbi A, et al. The march of pluripotent stem cells in cardiovascular regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:201.

13. Tan F, Li X, Wang Z, Li J, Shahzad K, Zheng J. Clinical applications of stem cell-derived exosomes. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:17.

14. Kimbrel EA, Lanza R. Next-generation stem cells - ushering in a new era of cell-based therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:463-79.

15. Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425:968-73.

16. Zhang K, Cheng K. Stem cell-derived exosome versus stem cell therapy. Nat Rev Bioeng. 2023;:1-2.

17. Dinh PC, Paudel D, Brochu H, et al. Inhalation of lung spheroid cell secretome and exosomes promotes lung repair in pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1064.

18. Pan Y, Wu W, Jiang X, Liu Y. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases: from mechanisms to therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;163:114817.

19. Zhang N, Xie X, Chen H, Chen H, Yu H, Wang JA. Stem cell-based therapies for atherosclerosis: perspectives and ongoing controversies. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:1731-40.

20. Dou Y, Chen Y, Zhang X, et al. Non-proinflammatory and responsive nanoplatforms for targeted treatment of atherosclerosis. Biomaterials. 2017;143:93-108.

21. Ling H, Guo Z, Tan L, Cao Q, Song C. Stem cell-derived exosomes: role in the pathogenesis and treatment of atherosclerosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2021;130:105884.

23. Li H, Zhang J, Tan M, et al. Exosomes based strategies for cardiovascular diseases: opportunities and challenges. Biomaterials. 2024;308:122544.

24. Andrzejewska A, Dabrowska S, Lukomska B, Janowski M. Mesenchymal stem cells for neurological disorders. Adv Sci. 2021;8:2002944.

25. Harrell CR, Jovicic N, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes and other extracellular vesicles as new remedies in the therapy of inflammatory diseases. Cells. 2019;8:1605.

26. Eom YW, Shim KY, Baik SK. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver fibrosis. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:580-9.

27. Cheng W, Zeng Y, Wang D. Stem cell-based therapy for pulmonary fibrosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:492.

28. Samsonraj RM, Raghunath M, Nurcombe V, Hui JH, van Wijnen AJ, Cool SM. Concise review: multifaceted characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells for use in regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:2173-85.

29. Slukvin II, Kumar A. The mesenchymoangioblast, mesodermal precursor for mesenchymal and endothelial cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75:3507-20.

30. Li B, Cheng Y, Yu S, et al. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese type 2 diabetic mice. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:8628027.

31. Li Y, Shi G, Liang W, et al. Allogeneic Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation alleviates atherosclerotic plaque by inhibiting Ox-LDL uptake, inflammatory reaction and endothelial damage in rabbits. Cells. 2023;12:1936.

32. Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, et al. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation. 2004;109:1292-8.

33. Shi H, Liang M, Chen W, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cellderived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate atherosclerosis by modulating inflammatory responses. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:1461-8.

34. Lin Y, Zhu W, Chen X. The involving progress of MSCs based therapy in atherosclerosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:216.

35. Li X, Deng Y, Zhao S, Zhang D, Chen Q. Injection of hTERT-transduced endothelial progenitor cells promotes beneficial aortic changes in a high-fat dietary model of early atherosclerosis. Cardiology. 2017;136:230-40.

36. Lin YL, Yet SF, Hsu YT, Wang GJ, Hung SC. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate atherosclerotic lesions via restoring endothelial function. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:44-55.

38. Chistiakov DA, Melnichenko AA, Myasoedova VA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN. Mechanisms of foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. J Mol Med. 2017;95:1153-65.

39. Sarraju A, Nissen SE. Atherosclerotic plaque stabilization and regression: a review of clinical evidence. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21:487-97.

40. Bloom SI, Islam MT, Lesniewski LA, Donato AJ. Mechanisms and consequences of endothelial cell senescence. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:38-51.

41. Xu S, Ilyas I, Little PJ, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and beyond: from mechanism to pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73:924-67.

42. Grego A, Fernandes C, Fonseca I, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: mechanisms and in vitro models. Mol Cell Biochem. 2025;480:4671-95.

43. Salvolini E, Orciani M, Vignini A, Mattioli-Belmonte M, Mazzanti L, Di Primio R. Skin-derived mesenchymal stem cells (S-MSCs) induce endothelial cell activation by paracrine mechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:848-50.

44. Liu Y, Chen J, Liang H, et al. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells not only ameliorate blood glucose but also protect vascular endothelium from diabetic damage through a paracrine mechanism mediated by MAPK/ERK signaling. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:258.

45. Wang J, Meng S, Chen Y, et al. MSC-mediated mitochondrial transfer promotes metabolic reprograming in endothelial cells and vascular regeneration in ARDS. Redox Rep. 2025;30:2474897.

46. Dabravolski SA, Popov MA, Utkina AS, et al. Preclinical and mechanistic perspectives on adipose-derived stem cells for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease treatment. Mol Cell Biochem. 2025;480:4647-70.

47. Gao H, Yu Z, Li Y, Wang X. miR-100-5p in human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes mediates eosinophilic inflammation to alleviate atherosclerosis via the FZD5/Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2021;53:1166-76.

48. Werner N, Nickenig G. Clinical and therapeutical implications of EPC biology in atherosclerosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:318-32.

49. Liu Z, Ding X, Fang F, et al. Higher numbers of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in stroke patients with intracranial arterial stenosis. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:161.

50. Altabas V, Biloš LSK. The role of endothelial progenitor cells in atherosclerosis and impact of anti-lipemic treatments on endothelial repair. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2663.

51. Yang J, Lu Y, Zhao J, et al. Reinvesting the cellular properties of human amniotic epithelial cells and their therapeutic innovations. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1466529.

52. Miki T. Stem cell characteristics and the therapeutic potential of amniotic epithelial cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018;80:e13003.

53. Qiu C, Ge Z, Cui W, Yu L, Li J. Human amniotic epithelial stem cells: a promising seed cell for clinical applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7730.

54. Miki T. A rational strategy for the use of amniotic epithelial stem cell therapy for liver diseases. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5:405-9.

55. Tan B, Yuan W, Li J, et al. Therapeutic effect of human amniotic epithelial cells in murine models of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Cytotherapy. 2018;20:1247-58.

56. Yang PJ, Zhao XY, Kou YH, et al. Human amniotic epithelial stem cell is a cell therapy candidate for preventing acute graft-versus-host disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2024;45:2339-53.

57. Fang SM, Du DY, Li YT, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for stabilizing and repairing of atherosclerotic ruptured plaque. Thromb Res. 2013;131:e253-7.

58. Taraballi F, Pastò A, Bauza G, Varner C, Amadori A, Tasciotti E. Immunomodulatory potential of mesenchymal stem cell role in diseases and therapies: a bioengineering prospective. J Immunol Regen Med. 2019;4:100017.

59. Siew WS, Tang YQ, Kong CK, et al. Harnessing the potential of CRISPR/Cas in atherosclerosis: disease modeling and therapeutic applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8422.

60. Oostveen RF, Khera AV, Kathiresan S, et al. New approaches for targeting PCSK9: small-interfering ribonucleic acid and genome editing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2023;43:1081-92.

61. Bagno LL, Carvalho D, Mesquita F, et al. Sustained IGF-1 secretion by adipose-derived stem cells improves infarcted heart function. Cell Transplant. 2016;25:1609-22.

62. Choi JS, Jeong IS, Han JH, Cheon SH, Kim SW. IL-10-secreting human MSCs generated by TALEN gene editing ameliorate liver fibrosis through enhanced anti-fibrotic activity. Biomater Sci. 2019;7:1078-87.

63. Lin YK, Hsiao LC, Wu MY, et al. PD-L1 and AKT overexpressing adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells enhance myocardial protection by upregulating CD25+ T cells in acute myocardial infarction rat model. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;25:134.

64. Chuang ST, Stein JB, Nevins S, et al. Enhancing CAR macrophage efferocytosis via surface engineered lipid nanoparticles targeting LXR signaling. Adv Mater. 2024;36:2308377.

65. Tan H, Li W, Pang Z, et al. Genetically engineered macrophages Co-loaded with CD47 inhibitors synergistically reconstruct efferocytosis and improve cardiac remodeling post myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13:2303267.

66. Liu H, Wu S, Lee H, et al. Polymer-functionalized mitochondrial transplantation to plaque macrophages as a therapeutic strategy targeting atherosclerosis. Adv Ther. 2022;5:2100232.

67. Jiang Y, Yu M, Song ZF, Wei ZY, Huang J, Qian HY. Targeted delivery of mesenchymal stem cell-derived bioinspired exosome-mimetic nanovesicles with platelet membrane fusion for atherosclerotic treatment. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024;19:2553-71.

68. Luo L, Tang J, Nishi K, et al. Fabrication of synthetic mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in mice. Circ Res. 2017;120:1768-75.

69. Gupta D, Zickler AM, El Andaloussi S. Dosing extracellular vesicles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;178:113961.

70. Dixson AC, Dawson TR, Di Vizio D, Weaver AM. Context-specific regulation of extracellular vesicle biogenesis and cargo selection. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:454-76.

71. Sanz-Ros J, Romero-García N, Mas-Bargues C, et al. Small extracellular vesicles from young adipose-derived stem cells prevent frailty, improve health span, and decrease epigenetic age in old mice. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabq2226.

72. Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367:eaau6977.

73. Yin Y, Chen H, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang X. Roles of extracellular vesicles in the aging microenvironment and age-related diseases. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021;10:e12154.

74. Chen YT, Yuan HX, Ou ZJ, Ou JS. Microparticles (Exosomes) and Atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020;22:23.

75. Boulanger CM, Loyer X, Rautou PE, Amabile N. Extracellular vesicles in coronary artery disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:259-72.

76. Li J, Wen T, Li X, et al. Harnessing extracellular vesicles to tame inflammation: a new strategy for atherosclerosis therapy. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1625958.

77. Adamiak M, Sahoo S. Exosomes in myocardial repair: advances and challenges in the development of next-generation therapeutics. Mol Ther. 2018;26:1635-43.

78. Yuan Y, Du W, Liu J, et al. Stem cell-derived exosome in cardiovascular diseases: macro roles of micro particles. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:547.

79. Wendt S, Goetzenich A, Goettsch C, et al. Evaluation of the cardioprotective potential of extracellular vesicles - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15702.

80. Li L, Wang H, Zhang J, Chen X, Zhang Z, Li Q. Effect of endothelial progenitor cell-derived extracellular vesicles on endothelial cell ferroptosis and atherosclerotic vascular endothelial injury. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:235.

81. Xiao X, Xu M, Yu H, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles mitigate oxidative stress-induced senescence in endothelial cells via regulation of miR-146a/Src. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:354.

82. Xing X, Li Z, Yang X, et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosome-mediated microRNA-342-5p protects endothelial cells against atherosclerosis. Aging. 2020;12:3880-98.

83. Lu W, Li X, Wang Z, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles accelerate diabetic wound healing by inhibiting NET-induced ferroptosis of endothelial cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20:3515-29.

84. Li J, Xue H, Li T, et al. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells attenuate the progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE-/- mice via miR-let7 mediated infiltration and polarization of M2 macrophage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;510:565-72.

85. Ma J, Chen L, Zhu X, Li Q, Hu L, Li H. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal miR-21a-5p promotes M2 macrophage polarization and reduces macrophage infiltration to attenuate atherosclerosis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2021;53:1227-36.

86. de Couto G, Gallet R, Cambier L, et al. Exosomal MicroRNA transfer into macrophages mediates cellular postconditioning. Circulation. 2017;136:200-14.

87. Yang F, Wu Y, Chen Y, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorate liver steatosis by promoting fatty acid oxidation and reducing fatty acid synthesis. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100746.

88. Liu C, Su C. Design strategies and application progress of therapeutic exosomes. Theranostics. 2019;9:1015-28.

89. Zhu Y, Liao ZF, Mo MH, Xiong XD. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles for vasculopathies and angiogenesis: therapeutic applications and optimization. Biomolecules. 2023;13:1109.

90. Ramaraju H, Miller SJ, Kohn DH. Dual-functioning peptides discovered by phage display increase the magnitude and specificity of BMSC attachment to mineralized biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2017;134:1-12.

91. Nakamura Y, Kita S, Tanaka Y, et al. Adiponectin stimulates exosome release to enhance mesenchymal stem-cell-driven therapy of heart failure in mice. Mol Ther. 2020;28:2203-19.

92. Wang H, Bai Z, Qiu Y, et al. Empagliflozin-pretreated MSC-derived exosomes enhance angiogenesis and wound healing via PTEN/AKT/VEGF pathway. Int J Nanomedicine. 2025;20:5119-36.

93. Fathi E, Farahzadi R, Sheikhzadeh N. Immunophenotypic characterization, multi-lineage differentiation and aging of zebrafish heart and liver tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a novel approach in stem cell-based therapy. Tissue Cell. 2019;57:15-21.

94. Wiklander OP, Nordin JZ, O’Loughlin A, et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:26316.

95. Li J, Sun S, Zhu D, et al. Inhalable stem cell exosomes promote heart repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2024;150:710-23.

96. Hu S, Li Z, Shen D, et al. Exosome-eluting stents for vascular healing after ischaemic injury. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5:1174-88.

97. Lin Y, Yan M, Bai Z, et al. Huc-MSC-derived exosomes modified with the targeting peptide of aHSCs for liver fibrosis therapy. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20:432.

98. Zheng J, Li Y, Ge X, et al. Devouring atherosclerotic plaques: the engineered nanorobot rousing macrophage efferocytosis by a two-pronged strategy. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;35:2415477.

99. Yin M, Lin J, Yang M, et al. Platelet membrane-cloaked selenium/ginsenoside Rb1 nanosystem as biomimetic reactor for atherosclerosis therapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022;214:112464.

100. Hu CM, Fang RH, Wang KC, et al. Nanoparticle biointerfacing by platelet membrane cloaking. Nature. 2015;526:118-21.

101. Modery-Pawlowski CL, Kuo HH, Baldwin WM, Sen Gupta A. A platelet-inspired paradigm for nanomedicine targeted to multiple diseases. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:1709-27.

102. Xie L, Chen J, Hu H, et al. Engineered M2 macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles with platelet membrane fusion for targeted therapy of atherosclerosis. Bioact Mater. 2024;35:447-60.

103. Hu S, Wang X, Li Z, et al. Platelet membrane and stem cell exosome hybrids enhance cellular uptake and targeting to heart injury. Nano Today. 2021;39:101210.

104. Wang L, Wang D, Ye Z, Xu J. Engineering extracellular vesicles as delivery systems in therapeutic applications. Adv Sci. 2023;10:2300552.

105. Malle MG, Song P, Löffler PMG, et al. Programmable RNA loading of extracellular vesicles with toehold-release purification. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146:12410-22.

106. Li Z, Zhao P, Zhang Y, et al. Exosome-based Ldlr gene therapy for familial hypercholesterolemia in a mouse model. Theranostics. 2021;11:2953-65.

107. Zou J, Cui W, Deng N, et al. Fate reversal: Exosome-driven macrophage rejuvenation and bacterial-responsive drug release for infection immunotherapy in diabetes. J Control Release. 2025;382:113730.

108. Du Y, Wang H, Yang Y, et al. Extracellular Vesicle mimetics: preparation from top-down approaches and biological functions. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022;11:2200142.

109. Ohta H, Liu X, Maeda M. Autologous adipose mesenchymal stem cell administration in arteriosclerosis and potential for anti-aging application: a retrospective cohort study. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:538.

110. Saad A, Dietz AB, Herrmann SMS, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells increase cortical perfusion in renovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2777-85.

111. Marei HE. Stem cell therapy: a revolutionary cure or a pandora’s box. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;16:255.

112. Zhu Y, Ge J, Huang C, Liu H, Jiang H. Application of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for aging frailty: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Theranostics. 2021;11:5675-85.

113. Zhou W, Lin J, Zhao K, et al. Single-cell profiles and clinically useful properties of human mesenchymal stem cells of adipose and bone marrow origin. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1722-33.

114. Sato Y, Bando H, Di Piazza M, et al. Tumorigenicity assessment of cell therapy products: the need for global consensus and points to consider. Cytotherapy. 2019;21:1095-111.

115. Emini Veseli B, Perrotta P, De Meyer GRA, et al. Animal models of atherosclerosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;816:3-13.

116. Wang JC, Bennett M. Aging and atherosclerosis: mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ Res. 2012;111:245-59.

117. Qu Q, Fu B, Long Y, Liu ZY, Tian XH. Current strategies for promoting the large-scale production of exosomes. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2023;21:1964-79.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].