Multi-functional platelets: translating biological functions into therapeutic applications

Abstract

Platelets, produced by megakaryocytes, extend far beyond their traditional roles in hemostasis and thrombosis. Emerging studies indicate that they actively participate in multiple physiological and pathological processes through diverse activities, such as modulating immune responses, facilitating tissue regeneration, and contributing to the remodeling of disease-associated microenvironments. This review systematically summarizes the biological basis of platelets (including generation, activation, release and aging) and analyzes their interaction with hemostasis, inflammation, and injured tissues, providing the foundation for advanced therapy. Building on this foundation, we focus on two dimensions and summarize the advanced progress: (1) Platelet targeting therapeutic strategies, including precise intervention in anti-tumor therapy (inhibiting metastasis and immune evasion), cardiovascular diseases (modulating thrombosis and vascular stenosis), and emergency hemostasis (enhancing coagulation efficiency); (2) Engineering construction and targeted delivery using platelet and the derivatives (e.g., platelet-rich plasma, extracellular vesicles, membranes, and platelet-mimicking materials), which leverage their intrinsic bioactivity and multi-targeting capabilities. By bridging platelet biology to therapeutic innovation, this review serves as a framework for understanding disease mechanisms and developing next-generation targeted therapies.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Platelets are non-nucleated cell fragments continuously produced by megakaryocytes (MKs) in the bone marrow and are one of the smallest cellular structures (2~5 µm) in the human body[1]. Despite this, their structure is extremely complex, rich in various cytokines, functional proteins and organelles (mitochondria, lysosomes, α-granules and dense granules), thus enabling them to perform multiple biological functions[2]. Beyond their classical roles in hemostasis, platelets are now recognized as multifunctional regulators, actively participating in immune modulation, tissue regeneration, and pathological microenvironments remodeling[3,4]. The multiple functions establish platelets as dynamic mediators at the crossroads of physiology and disease, providing a theoretical basis for therapeutic innovation.

Platelet-related treatments have also been successfully applied in clinical practice. Platelet transfusion is widely used to restore or enhance the coagulation function of patients[5,6]. Moreover, in the treatment of certain diseases, platelets have become a key therapeutic target. Antiplatelet therapy is an important strategy for the prevention and management of various vascular diseases, mainly by inhibiting platelet aggregation and thereby reducing the risk of thrombosis[7]. As the most classic antiplatelet drug, aspirin irreversibly inhibits platelet cyclooxygenase (COX), reducing the production of thromboxane A2 (TXA2)[8]. The active metabolites of clopidogrel and ticagrelor, respectively, bind to the P2Y12 receptor on platelets in an irreversible and reversible manner, thereby inhibiting platelet activation and aggregation[9]. In recent years, with the deepening understanding of platelet function, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been successfully applied in the repair and treatment of bone tissue and chronic wounds, among other conditions[10-12]. These applications demonstrate the multifunctional characteristics of platelets: on the one hand, their role is not limited to hemostasis but also involves immune regulation and tissue repair; on the other hand, platelets can serve as both therapeutic targets and biological agents directly involved in the treatment process.

The overarching objective of this review is to broaden the understanding of platelet functions and promote the development of platelet-related applications. We begin with an overview of platelet biology, detailing their structure and composition, and highlighting their critical roles in hemostasis/thrombosis, inflammatory responses, and tissue repair, including cellular interactions and underlying signaling mechanisms. Subsequently, we link these biological functions to therapeutic applications. Platelet-based therapeutic strategies are summarized, including interventions targeting platelet activity for diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and emergency hemostasis, as well as studies exploring platelets and their derivatives as biotherapeutic agents, providing novel insights for researchers [Figure 1].

Figure 1. The platelet biology and platelet-based therapeutic innovation. Created in BioRender. Zhang W (2025) https://BioRender.com/hes7667.

PLATELETS’ PHYSIOLOGY

Platelet production and clearance

The structure of the platelet

Platelets are disc-shaped, nucleated blood cells with an average diameter of 2-5 µm and a thickness

Platelet zones and their general features

| Zone | Components | Features | Reference |

| Peripheral zone | Glycocalyx | Covering the outermost layer of the peripheral zone Mainly composed of the sugar chain in glycoproteins Related to platelet adhesion | [13] |

| Platelet plasma membrane | The surface appears wrinkled | [14] | |

| Sol-gel zone | Microtubules | Non-membrane tubular structures 8-24 layers, each with a diameter of about 25 nm Arranged in a ring around the periphery of platelets | [18,19] |

| Microfilaments | Fine filamentous structures Approximately 5 nm in diameter | [20] | |

| Organelle zone | Platelet granules, electron-dense bodies, peroxisomes, lysosomes, mitochondria, clumps, and glycogen granules | Facilitate metabolic processes and store enzymes, non-metabolic adenine nucleotides, serotonin, various protein components, and calcium ions used for secretion | [15-17,21] |

| Membrane system | Open canalicular system (OCS) | Pipeline network with a spongy structure Provide entry points for material exchange | [14] |

| Dense tubular system (DTS) | A remnant of the rough endoplasmic reticulum of megakaryocytes TXA2 synthesis and Ca2+ sequestration | [22,23] |

The glycocalyx covers the outermost layer of the peripheral zone and is rich in various glycoproteins (GPs) and glycolipids[13]. It is associated with platelet adhesion and is the site of many platelet receptors, such as integrin αIIbβ3, integrin α2β1, adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptors, adrenaline receptors, collagen receptors, and thrombin receptors. The middle layer of the peripheral zone is the cell membrane, which is wrinkled and features a randomly arranged open canalicular system (OCS)[14-17].

The sol-gel zone serves as the matrix of platelet cytoplasm, rich in various microtubules and microfilaments. These structures maintain the disc-shaped morphology of platelets and regulate platelet shape changes, pseudopod extension, and granule secretion. Microtubules are non-membranous tubular structures arranged in a ring around the periphery of platelets, running parallel to their outer surface[18,19]. Microfilaments are fine filamentous structures that are generally not visible in platelets at rest. When platelets are activated, large numbers of microfilaments appear in the cell matrix[20].

The organelle zone contains platelet granules, electron-dense bodies, peroxisomes, lysosomes, mitochondria, and clumps, as well as scattered glycogen granules randomly dispersed in the cytoplasm[21]. The function of the organelle region is to facilitate metabolic processes and store enzymes, non-metabolic adenine nucleotides, serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT), various protein components, and calcium ions used for secretion.

In addition to the outer membrane, the membrane system of human platelets also includes the Golgi complex, the OCS, the dense tubular system (DTS), and the rough endoplasmic reticulum. The DTS is a remnant of the rough endoplasmic reticulum of MKs[22]. It has been shown to be the site of calcium ion (Ca2+) sequestration, which is crucial for triggering contraction events[22,23]. In addition, the dense tubule system is also the site of enzymes required for prostaglandin (PG) synthesis, including phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase, and thromboxane synthase, which support the synthesis of arachidonic acid (AA) to produce TXA2[22].

The production of platelet

MKs originate from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)[24], which are primarily found in the bone marrow[25]. Early developmental stages of HSCs can also be observed in environments such as the yolk sac, fetal liver, and spleen[26]. To assemble and release platelets, MKs undergo internal mitosis to form polyploid cells, significantly increasing in size, accumulating platelet-specific granules in the cytoplasm, and exhibiting increased levels of cytoskeletal proteins. Ultimately, they form a highly folded invaginated membrane system (IMS), which is continuous with the plasma membrane and serves as a storage reservoir for platelet formation[27].

Polyploid MKs migrate to vascular niches, where they form numerous long-branched cytoplasmic projections called proplatelets. Microtubule sliding is the main driving force of proplatelet elongation. The formation of prothrombocytes is not a continuous process, but rather involves repeated stages of elongation, pause, and retraction[28]. Proplatelets released from MKs were mostly dumbbell-shaped structures with enlarged ends or bead-like structures without nuclei. The multiple enlarged protrusions of the proplatelet are connected by a finer microtubule skeleton structure. Under the physiological shear stress of blood flow, this microtubule skeleton can twist and break around its center, thereby splitting into multiple disc-shaped mature platelets[29].

Platelet production is a complex process regulated by multiple factors and mechanisms. Thrombopoietin (TPO) is an important cytokine in the hematopoietic process of MKs, playing a key role in promoting the maturation and differentiation of MKs[30], while also supporting the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of MKs in the bone marrow. During the proplatelet formation stage, β1-tubulin, as the primary tubulin subunit in microtubules of MKs, plays a crucial role in proplatelet formation, with its reorganization being essential for this process. Cytoplasmic dynein uses β1-tubulin to provide the necessary power for proplatelet elongation[28,29]. Subsequently, during platelet release and terminal formation, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and its receptor (S1PR1) serve as key mediators for the directed elongation of proplatelets and the terminal release of new platelets. The S1P gradient guides proplatelets to extend into the bone marrow sinus, and activation of the S1PR1 signaling pathway directly stimulates the release of new platelets[31].

The clearance of platelet

Platelet clearance is a complex process involving multiple mechanisms that interact to maintain platelet number balance. The first pathway is governed by the balance between pro-apoptotic proteins B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) associated X-BCL2 antagonist/killer (BAX-BAK) and anti-apoptotic proteins such as BCL-2 in the cytoplasm[32]. BCL-2 homology 3 (BH3)-only proteins, mitochondrial permeability changes, and phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure also participate in apoptosis-induced platelet clearance. Platelets expose PS on their surface through two pathways: one dependent on intracellular Ca2+ and a

Additionally, there is a mechanism involving the important receptor GP Ibα on the platelet surface[42]. When GP Ibα is cleaved on the platelet membrane[43], new epitopes are exposed, activating downstream signaling pathways that lead to platelet desialylation and PS exposure[40]. De-sialylated platelets are subsequently recognized and cleared by hepatocytes and macrophages[44].

Platelet activation

Exogenous pathway

Collagen is the primary component of blood vessel walls. When the vascular endothelium is damaged, collagen fibers are exposed to the bloodstream, serving as a key trigger for platelet activation by binding to the platelet surface receptor GP VI. GP VI activates phospholipase C (PLC), triggering the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway. GP VI forms a non-covalent complex with the Fc receptor gamma chain (FcRγ), and this complex is essential for the high-affinity binding of GP VI to collagen[45,46]. Furthermore,

In addition, upon vascular injury, subendothelial matrix proteins, including collagen-bound von Willebrand Factor (vWF), are exposed to the bloodstream. Platelet surface GP Ib, exclusively expressed on platelets, binds transiently to vWF, tethering platelets to the injured site. This interaction exhibits a rapid on-off rate, facilitating subsequent binding of the collagen receptor GP VI to fibrillar collagen for sustained activation[52]. Under high shear conditions, the GP Ib-vWF interaction is essential for platelet recruitment and triggers intracellular signaling cascades involving tyrosine phosphorylation of SYK, SFKs (Lyn and Fyn), and PLCγ2, leading to integrin αIIbβ3 activation and firm adhesion[53]. Recent studies identified novel regulators of GP Ib signaling, such as reelin and phospholipase D1 (PLD1)[54]. Reelin, expressed in platelet and endothelial cells, modulates GP Ib-dependent thrombus formation by interacting with the amyloid precursor protein (APP) receptor, enhancing integrin activation and extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK)/protein kinase B (Akt) phosphorylation[55]. PLD1, through phosphatidic acid production, influences αIIbβ3 activation and

Integrin receptors play a central role in the subsequent stages of platelet activation. The platelet surface primarily expresses two types of integrins: β1 and β3. Among these, the β3-type αIIbβ3 (GP IIb/IIIa) is one of the most critical receptors[56]. Under the influence of GP Ib-vWF signaling and other agonists (such as collagen and ADP), αIIbβ3 undergoes a conformational change via the “inside-out” signaling pathway, transitioning to a high-affinity state that enables binding to ligands such as fibrinogen and vWF[57]. By

Endogenous pathway

For the ADP activation pathway, ADP acts as an agonist on two purinergic G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) on platelets[59], namely the P2Y1 receptor coupled to Guanine Nucleotide-Binding Protein Subunit

P2Y1 receptor: After activating Gαq-coupled GPCR, Gαq dissociates from the receptor, binds to, and activates the PLCβ isoenzyme, catalyzing the hydrolysis of PIP2 to form the second messengers IP3 and DAG. Platelets with Gαq gene knockout exhibit defects in IP3 release and are unable to mobilize calcium ions in response to GPCR agonist stimulation. Gαq is critical for platelet aggregation induced by most platelet GPCR agonists (such as ADP) and is indirectly important for platelet responses induced by adhesion proteins such as collagen, as these responses require amplified signals induced by TXA2, ADP, etc., to achieve optimal platelet activation. However, activation of the P2Y1 receptor alone only produces small and reversible platelet aggregation; the P2Y12 receptor: The P2Y12 ADP receptor is a typical Gαi-coupled receptor. Gαi binds to adenylate cyclase and inhibits its function, thereby reducing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) synthesis. cAMP maintains platelet quiescence by stimulating cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), so Gαi inhibition of cAMP synthesis is critical for platelet activation. Additionally, upon activation of Gαi, the dissociated Gβγ interacts with PI3Kγ and potentially PI3Kβ subtypes, activating them - a process that is important in Gαi signaling. Concurrently, the Gαi pathway also plays a role in the activation of small guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-binding RAS-associated protein 1b (Rap1b) and its regulatory factor RASA3, as well as the activation of SFKs. Stimulation of the P2Y12 receptor amplifies and stabilizes platelet aggregation responses. There are complex interactions between the P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors, and their co-activation is essential for complete platelet aggregation[61].

For the TXA2 activation pathway, when platelets are activated, intracellular Ca2+ concentrations increase, activating cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2). cPLA2 hydrolyzes membrane phospholipids, releasing AA[62]. AA is then converted into PG under the action of COX, including TXA2. As a potent platelet agonist, it binds to its GPCR on the platelet membrane - the thromboxane receptor (TP). TP is coupled to Gq and G12/13 proteins[63]. TXA2 induces a conformational change in the α subunit (Gαq) of the Gq protein, causing the bound guanosine diphosphate (GDP) to be replaced by GTP. Subsequently,

Platelet secretion

The secretion of platelets is closely related to the internal compartments α-granules, dense granules and lysosomes within them [Table 2]. Vesicle-associated membrane proteins mediate fusion between platelet granules, between granules and the open tubular system, and between granules and the plasma membrane[68-70]. During platelet secretion, granules fuse with the target plasma membrane or surface-connected tubular system (SCCS) membrane, releasing their contents into the extracellular space. There are two competing views on the mechanism of granule fusion: one proposes that granules fuse independently with the SCCS membrane, while the other suggests that platelet secretion involves composite fusion between granules, followed by fusion with the plasma membrane[71,72].

The content and functions of granules in platelets

| Platelet granules | Amount | Content | Function | Reference |

| α-granules | 50-80 | growth factors, coagulation proteins, adhesion molecules, cytokines, cell activators, and angiogenesis factors | Cell adhesion Coagulation Inflammation Cell growth Host defense | [69,73,77-79] |

| Dense granules | 3-8 | adenine nucleotides (such as ADP and ATP), uracil and guanine nucleotides, calcium, potassium, polyphosphates, and bioactive amines (such as serotonin and histamine) | Release ADP as a potent platelet agonist, participating in hemostasis and thrombus formation Secrete serotonin to support platelet aggregation and regulate vascular tone Secrete polyphosphate, initiates bradykinin production, supports vascular permeability and edema in the body | [15,17,82,83] |

| Lysosomes | Small amount | Lysosomal membrane proteins LAMP-1, LAMP-2, and CD63 (LAMP-3), as well as various acid hydrolases (at least 13 types), cathepsin D, and cathepsin E | During platelet aggregation in the body, lysosomes are likely to digest vascular wall matrix components and may also digest autophagic fragments | [84] |

α-granules

α-granules are round or oval in shape, with a diameter of 200~500 nm. On average, each platelet contains 50-80 α-granules, making them the most abundant secretory granules in platelets[73]. α-granules begin to form in MKs, and their maturation process continues into circulating platelets. Their proteins are supplied through both synthesis and endocytosis, with membrane transport mediated by coat proteins and vesicle transport proteins. The resulting vesicles are transferred to the multivesicular body for sorting[68,74-76].

α-granules contain growth factors, coagulation proteins, adhesion molecules, cytokines, cell activators, and angiogenesis factors, among others, and are involved in processes such as cell adhesion, coagulation, inflammation, cell growth, and host defense[69]. Upon activation, membrane-bound proteins are expressed on the platelet surface, and soluble proteins are released into the extracellular space[77]. During hemostasis and thrombus formation, α-granules release fibrinogen and vWF, promoting platelet-platelet and platelet-endothelial cell interactions; components expressing fibrinogen receptor GP IIb-IIIa, collagen receptor GP VI, and vWF receptor complex GP Ib-IX-V support platelet adhesion[78]; release of coagulation factors participates in secondary hemostasis, and can also secrete proteins that limit coagulation to maintain hemostatic balance. In the formation of inflammation, α-granules provide platelet surface receptors, promoting interactions with leukocytes and endothelial cells, leading to mutual activation, cell recruitment, and the spread of inflammatory phenotypes[79]; they release various pro-inflammatory and immunomodulatory factors, promoting inflammatory cell recruitment and activation, chemokine secretion, and cell differentiation, with their pro-inflammatory effects associated with atherosclerosis (AS).

Dense granules

Dense granules are smaller than α-granules, with each normal platelet containing 3-8 of them. They exhibit diverse morphologies and have electron-opaque spherical structures[15]. Originating from the endosomal system, the biogenesis of dense granules involves the lysosome-associated organelle complex (BLOCs) and AP-3, which play crucial roles in their formation. Early sorting occurs within the multivesicular body, and upon maturation, their contents become denser[80,81].

Dense granules contain high concentrations of adenine nucleotides [such as ADP and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)], uracil and guanine nucleotides, calcium, potassium, polyphosphates, and bioactive amines (such as 5-HT and histamine), with an internal pH of approximately 5.4[17,82]. Dense granules are the primary source of ADP, which acts as a potent platelet agonist involved in hemostasis and thrombus formation; 5-HT secretion supports platelet aggregation and regulates vascular tone; released Ca2+ and polyphosphates aid in clot formation, and partially released diadenosine polyphosphate can limit platelet activation[83]. Similar to α-granules, dense granules also participate in inflammation formation, secreting polyphosphates, initiating bradykinin production, and supporting vascular permeability and edema in the body.

Lysosomes

Platelets contain primary and secondary lysosomes, with a diameter typically ranging from 175 nm to

Methods for platelet function

Platelet function testing encompasses a diverse array of methodologies tailored to evaluate distinct aspects of platelet biology and clinical relevance. Traditional approaches include bleeding time (BT), which historically served as the primary in vivo assessment of hemostatic plug formation but is now largely obsolete due to poor standardization and limited predictive value[86]. Light transmission aggregometry (LTA), utilizing PRP, remains the gold standard for diagnosing platelet dysfunction by measuring agonist-induced changes in light transmittance[87]. This method provides detailed insights into multiple activation pathways through the use of varied agonists (e.g., ADP, AA, collagen) but requires skilled personnel and careful sample handling.

Whole blood aggregometry techniques, such as impedance aggregometry, offer a more physiological milieu by eliminating the need for PRP preparation[59]. Multiple electrode aggregometry (MEA), a modern iteration, measures electrical impedance changes as platelets adhere to electrodes, enabling rapid assessment in clinical settings[88]. Lumiaggregometry combines aggregometry with luminescence detection to simultaneously evaluate platelet aggregation and ATP release, aiding in the diagnosis of storage pool defects[89].

Point-of-care testing (POCT) has revolutionized platelet function assessment with user-friendly devices such as the VerifyNow system, which employs fibrinogen-coated beads and turbidimetric detection to monitor antiplatelet therapy response[90]. The Platelet Function Analyzer (PFA-100/200) simulates

Flow cytometry provides advanced insights into platelet activation by quantifying surface markers (e.g.,

Each methodology presents unique advantages and limitations, with selection dictated by clinical context, sample availability, and required precision. While traditional assays such as LTA remain diagnostic standards, POCT and flow cytometry are increasingly favored for their speed and applicability in critical care and antiplatelet monitoring.

PLATELETS’ BIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS

Hemostasis and thrombosis

Physiological hemostasis is the primary mechanism through which the body naturally halts bleeding following vascular injury. Simultaneously, unnecessary blood clotting can also result in pathological clots (thrombi) within blood vessels, which is considered one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in developed countries[95]. This process comprises two interdependent, partially overlapping phases: primary hemostasis (vascular constriction and platelet aggregation) and secondary hemostasis (coagulation cascade and fibrin formation)[96,97]. This highly coordinated physiological response depends on intricate interactions and signal amplification cascades among various cell types (e.g., platelets) and factors. As central mediators, platelets actively participate in and regulate every stage of the hemostatic process [Figure 2].

Figure 2. The biological function of platelet in the hemostasis process. Created in BioRender. Zhang W (2025) https://BioRender.com/c5i6qcj. GP: Glycoprotein; vWF: von Willebrand factor.

Upon vascular injury, immediate vasoconstriction of the damaged vessel reduces local hemodynamic forces, initiating the hemostatic cascade. Subsequent rapid platelet adhesion to exposed subendothelial matrices predominantly composed of collagens I, III, and IV, which occurs through shear stress-dependent mechanisms: (1) Under high-shear stress (e.g., arterial circulation), vWF serves as the critical molecular bridge. The exposed A1 domain in vWF engages platelet surface GP Ib-IX-V complexes, mediating initial tethering and rolling, culminating in firm adhesion[2,98]; (2) Under low-shear stress (e.g., venules, capillaries), direct ligand-receptor interactions dominate: Platelet surface receptors GP Ia-IIa and GP VI bind collagen with high affinity[99,100]. This interaction not only anchors platelets but also triggers intracellular activation cascades, priming cells for aggregation. Adherent platelets undergo signal-dependent activation, leading to the release of dense and α-granule contents, including 5-HT and TXA2, which potentiate vasoconstriction. ADP engages purinergic receptors (e.g., P2Y12), activating PLC-driven signaling. This amplifies calcium influx and de novo TXA2 synthesis, establishing an autocrine feed-forward loop that recruits additional platelets. Meanwhile, a conformational shift in GP IIb-IIIa, the most abundant platelet surface receptor, exposes high-affinity binding sites for fibrinogen and vWF. Soluble fibrinogen bridges adjacent activated platelets via ligation of GP IIb-IIIa, driving irreversible aggregate formation. The release of α-granule constituents (e.g., fibrinogen, Factor V) primes the coagulation microenvironment for ensuing thrombin generation. The adhesion, activation, release, and aggregation of platelets facilitate a primary hemostatic plug to mechanically seal the wound, achieving initial hemostasis.

Secondary hemostasis is centered on the coagulation cascade, a tightly regulated amplification mechanism that results in a burst of thrombin generation. Thrombin subsequently cleaves soluble fibrinogen, converting it into insoluble fibrin monomers[101]. The platelet critically supports this process through three synergistic mechanisms: (1) Providing phospholipid surfaces. Activated platelets expose PS on their membranes, thereby forming critical platforms for the assembly of coagulation complexes. For instance, the prothrombinase complex (Factor Xa-Va-Ca2+) is assembled on PS-rich platelet surfaces, significantly enhancing thrombin generation; (2) Procoagulant components release. α-granule secretion introduces critical coagulation components, including fibrinogen, Factor V, and Factor XIII, into the injury microenvironment, thereby locally amplifying the coagulation cascade; (3) Enabling fibrin stabilization. Platelet-derived Factor XIIIa crosslinks fibrin monomers, forming mechanically stable polymeric networks. Meanwhile, platelets also enhance the stability of the blood clot through the retraction of the clot by the actomyosin.

In summary, platelets are the first responders to vascular injury and play a central role throughout the coagulation cascade - from the initial stages of hemostasis, involving adhesion and aggregation, to the amplification of the coagulation cascade, and ultimately to the stabilization and contraction of the formed blood clot. The precise regulation of platelet function is critical for maintaining hemostatic balance; dysregulation leading to either overactivity or deficiency can significantly elevate the risk of thrombosis or bleeding, respectively[102]. This dual role of platelets in physiological hemostasis and pathological thrombosis provides fundamental design principles and key inspirations for the development of safe and effective hemostatic materials, antithrombotic coatings, drug delivery systems, and other biomedical materials[103,104].

Inflammation

Platelets function as critical regulators of immune and inflammatory responses by releasing inflammatory factors and interacting with immune cells [Table 3]. They recognize pathogens by expressing Toll-like receptors (TLRs)[105]. Upon activation, they release cytokines and chemokines stored in α-granules, activating endothelial cells and immune cells to promote inflammation. The most abundant chemokines expressed by platelets are platelet factor 4 (PF-4, CXCL4) and RANTES [C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5)][106]. PF-4 drives monocyte differentiation and neutrophil adhesion[107]. Furthermore, PF-4 and CCL5 form heteromers with stronger chemotactic activity than either chemokine alone, synergistically recruiting monocytes. Activated platelets also produce soluble CD40L (sCD40L). Platelet-derived sCD40L triggers endothelial activation and inflammation by increasing the expression of inflammatory adhesion receptors [Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and Intercellular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1)], inducing the production of chemokines [C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), interleukin (IL)-6], and stimulating the production of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9). Serotonin (5-HT), released from platelet dense granules, enhances the ability of monocytes to stimulate T cells and is essential for platelet-mediated neutrophil recruitment[106]. IL-1β, a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine secreted by activated platelets, upregulates the expression of adhesion receptors on endothelial cells and their secretion of IL-6, IL-β, and CCL2. It also increases nitric oxide-induced vascular permeability to promote leukocyte extravasation, thereby exacerbating local inflammation[108,109]. Additionally, platelet-derived lipid mediators (such as resolvins) can promote inflammation resolution. However, resolvins’ adhesion to endothelial cells may exacerbate vascular pathology, establishing a thrombo-inflammatory vicious cycle[110].

Major platelet-derived factors associated with inflammation and their immune function

| Classification | Molecule | Immune function | Reference |

| Chemokines | PF-4 (CXCL4) | Drives monocyte activation and differentiation Promotes neutrophil adhesion and monocyte recruitment to endothelium Forms heteromers with CCL5, necessary for platelet-induced NETosis Prevents neutrophil apoptosis | [107,110,188] |

| RANTES (CCL5) | Synergizes with PF-4 to recruit neutrophils | [106,162,189] | |

| NAP-2 (CXCL7) | Stimulates transendothelial migration of neutrophils | [188] | |

| Cytokines | sCD40L | Activates the endothelial cell Promotes B cell differentiation Enhances CD8+ T cell response Impairs dendritic cell maturation and promotes inflammatory cytokine secretion | [106] |

| IL-1β | Induces endothelial secretion of chemokines (CCL2, IL-6, IL-8) Upregulates expression of endothelial adhesion receptors Increases nitric oxide (NO)-induced vascular permeability Synergistically promotes leukocyte migration | [108,112] | |

| TGF-β | Promotes fibroblast chemotaxis and proliferation, and contributes to tissue fibrosis Inhibits T cell proliferation | [190-192] | |

| Others | 5-HT | Recruits neutrophils Enhances the ability of monocytes to stimulate T cells | [106,193] |

Platelets interact with immune cells via released inflammatory factors. P-selectin (CD62p), stored within platelet α-granules, is a crucial adhesion molecule for immune cells expressing P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1)[106]. P-selectin mediates the formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates (PLAs) with neutrophils, enhancing phagocytic activity and inducing NETosis to trap pathogens. However, excessive Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) release can cause tissue damage[110,111]. Platelets also drive plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) production of Interferon-α (IFNα) via CD40L-CD40 signaling (platelet CD40L binding to CD40 on dendritic cells). This promotes dendritic cell maturation, enhances T cell responses, and can activate B cells to produce autoantibodies, forming a pro-inflammatory positive feedback loop[111,112].

Platelets-injured tissues interaction

The platelet is the first responder to tissue injury, functioning far beyond its traditional role in hemostasis. Via adhesion receptors (e.g., P-selectin, GP Ib and GP VI), platelets rapidly aggregate at the injury site, forming a temporary clot to seal the damaged endothelium and maintain tissue integrity[113,114]. Crucially, platelets dynamically regulate the regenerative microenvironment through the paracrine secretion of numerous active factors (e.g., growth factors, chemokines, cytokines), coordinating angiogenesis and the recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation of regenerative cells[107,113,114] [Table 4].

Platelet-associated mediators and their function in tissue healing and regeneration

| Classification | Molecule | Function | Reference |

| Growth factor | PDGF | Promotes the migration and proliferation of fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells Enhances protein synthesis in granulation tissue, ECM synthesis, and angiogenesis | [107,114,116,117] |

| VEGF | Acts as a potent angiogenic factor Induces endothelial cell proliferation and migration, accelerating neovascularization Stimulates hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration | [114,116,117,120] | |

| TGF-β | Stimulates fibroblast proliferation and the production of collagen types I and III Induces osteoclast apoptosis Overexpression contributes to scar formation | [108,114,116] | |

| FGF | Facilitates cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation; promotes angiogenesis Functions as an angiogenesis initiator | [114,116] | |

| HGF | Enhances cell migration and proliferation Stimulates hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration | [116,120] | |

| EGF | Promotes cell proliferation and recruitment Serves as an angiogenesis initiator | [114,116] | |

| ANG-1 | Stimulates angiogenesis and improves blood supply | [114,116] | |

| Chemokines | SDF-1 | Acts as a potent chemoattractant for stem cells and progenitor cells, crucial for their homing Supports the migration of progenitor cells from bone marrow to peripheral circulation During liver regeneration, it activates LSEC CXCR7 to promote hepatocyte proliferation | [107,114,115] |

| Cytokines | CXCL7 | Recruits neutrophils to the injury site to facilitate regeneration | [194] |

| CXCL5 | Recruits neutrophils to the injury site to facilitate regeneration | [194] | |

| IL-6 | Serves as an important pro-regenerative factor During liver regeneration, it is secreted by platelet-activated LSEC and promotes hepatocyte proliferation | [118-120] |

Platelet-derived active factors play a central role in tissue repair. For instance, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), a key initiator of angiogenesis, directly stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and migration[114]. During liver regeneration, VEGF-R1 activation on myeloid cells amplifies regenerative signals[115]. VEGF also contributes to tumor growth and spread by recruiting bone marrow-derived cells to the tumor microenvironment and promoting their differentiation into mature endothelial cells, thereby inducing tumor vascular network formation[116]. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) induces fibroblast migration and proliferation to wounds, promotes protein synthesis in granulation tissue, and stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and migration to accelerate angiogenesis[117]. PDGF also induces dedifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) to speed wound healing[8]. Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) stimulates fibroblast proliferation and their production of collagen types I and III. Additionally, TGF-β stimulates osteoblast progenitor cells, bone collagen synthesis, and induces osteoclast apoptosis[114].

Signals conveyed by platelet active factors activate repair cells and initiate tissue repair. Neutrophils, recruited by CXCL7, clear debris and secrete VEGF/MMP9 to enhance angiogenesis; Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells, guided by Stromal Cell-Derived Factor 1 (SDF-1) [C-X-C motif Ligand 12 (CXCL12)], migrate to the injury site and differentiate into endothelial cells for vascular reconstruction[107,114]; Macrophages release TGF-β, VEGF, and arginase, suppressing

Notably, platelets stimulate tissue regeneration via specific signaling axes. For example, in liver injury, platelets adhere to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), promoting hepatocyte proliferation through CXCR7 activation and secretion of pro-regenerative factors [IL-6/Wnt2 (Wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2)][118]. Platelets also stimulate hepatocyte proliferation by activating Akt and Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinase (ERK) 1/2 signaling pathways[119]. Furthermore, Platelets release factors [5-HT, Insulin-Like Growth Factor (IGF), Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF)] that directly stimulate hepatocyte regeneration. Direct platelet-endothelial cell interactions also promote the release of IL-6 and VEGF, further enhancing liver regeneration[120].

PLATELET-INSPIRED THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS

Targeting platelet strategy

The platelet is not only the key executor of physiological hemostasis, but its abnormal activation or dysfunction also drives the development of diseases such as AS, thrombosis, tumor metastasis and dissemination, and fatal hemorrhage. This section systematically reviews the platelet-targeting disease intervention strategies, highlighting the huge potential of targeting platelets in the treatment of major diseases.

Anti-thrombotic and cardiovascular diseases

AS is the main pathological basis for the high incidence and mortality of cardiovascular diseases worldwide, accounting for ~1/3 of the global disease burden[121]. As a potential risk, atherosclerotic plaques can rupture, exposing collagen, activating platelets, triggering the coagulation cascade to form blood clots, and blocking arterial blood flow. Platelet and AS are closely related, and the intrinsic mechanism is being explored.

Studies have shown that the success of implantable tissue-engineered vascular grafts (TEVGs) depends on the coordination of the inflammatory and wound healing processes, which simultaneously degrade the scaffold and guide the formation of new blood vessels. Once this coordination is disrupted, it may lead to abnormal remodeling phenomena such as stenosis, thereby affecting the long-term outcome and function of TEVGs. Lysosomal trafficking regulator (Lyst)-mediated platelet immune signal transduction is a key driver of stenosis. Lyst mutations significantly impair the exocytosis of platelet dense granules, but preserve the secretion of α-granules and adhesion to biomaterials. Uncontrolled platelet aggregation, caused by enhanced dense granule signaling, can lead to the formation of intramural thrombi, which are subsequently remodeled into obstructive neo-tissues[122]. Furthermore, the research also revealed the mechanism by which platelet-derived CXCL12 activates platelets through Btk and promotes collagen-dependent arterial thrombosis. In mice with platelet-specific CXCL12 deficiency, arterial thrombosis was effectively inhibited without prolonging tail BT, and neointimal lesions after carotid artery injury were significantly alleviated[123].

In addition, the early interaction between coagulation and inflammation and the late in-stent restenosis have undermined the efficacy of vascular stents after implantation. To address the interaction between inflammation, coagulation, and smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation, researchers have proposed a microenvironment-responsive coating aimed at regulating tissue responses and vascular regeneration throughout the remodeling process. Anticoagulant tirofiban was incorporated into the coating to inhibit coagulation. The MMP9-responsive nanoparticles embedded in the coating release salvianolic acid A to regulate inflammatory cell behavior and inhibit SMC dysfunction. By effectively interfering with coagulation and inflammation, the coating inhibits platelet-fibrin interaction and the formation of platelet-monocyte aggregates, thereby reducing the adverse effects on re-endothelialization[124]. The platelet’s functions offer numerous promising opportunities for the development of targeted antithrombotic treatment strategies. Antiplatelet drugs are the preferred therapy for prevention, but the potential risk of bleeding must be carefully weighed.

Tumor treatment

Platelets contribute to multiple stages of tumor progression, including development, growth, survival, and metastasis. Direct contact between platelets and tumor cells can induce platelet activation and lead to the formation of microaggregates on the tumor cell surface, thereby shielding tumor cells from immune recognition[125]. Additionally, platelets release a variety of pro-survival, pro-angiogenic, and immunomodulatory factors in an indirect manner, which help establish and sustain both the primary and metastatic tumor microenvironments. These findings highlight the potential of platelets as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, as well as therapeutic targets. Antiplatelet therapy is considered a promising strategy in cancer treatment[126].

Studies have shown that aspirin can neutralize VEGF released by platelets, which promotes angiogenesis, and inhibit tumor cell proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and migration, thereby suppressing tumor growth and metastasis[127,128]. Platelet-stored TGF-β is recognized as the primary source of circulating TGF-β in peripheral blood. Therefore, targeting platelet-derived TGF-β is expected to inhibit the metastasis of circulating tumor cells. At clinically relevant doses, platelet P2Y12 receptor antagonists have been shown to inhibit lung and liver metastases in mouse models of breast cancer and melanoma[129]. Furthermore, antibodies against GP IIb-IIIa have been shown to prevent the formation of platelet aggregates around circulating tumor cells, thereby reducing lung metastasis in melanoma mice[130]. In relevant models of ovarian cancer, rivaroxaban (a platelet GP VI competitor) has been proven to be capable of inhibiting tumor cell metastasis and enhancing the response to chemotherapy[131].

However, the risk of bleeding remains a major clinical challenge associated with all current antiplatelet therapies, necessitating the development of novel strategies to deplete or inactivate platelets within tumors or tumor-associated platelets specifically. Luo et al. developed unfolded human serum albumin (HSA)-coated perfluorotributylamine (PFTBA) nanoparticles (PFTBA@HSA), which exhibited superior platelet targeting capability and antiplatelet activity in vitro and in plasma, thereby effectively downregulating platelet-derived TGF-β. Compared with the clinically used antiplatelet drug ticagrelor, PFTBA@HSA not only reduces platelet-derived TGF-β levels but also lowers the risk of bleeding, thereby offering enhanced therapeutic efficacy[132]. To overcome the limited perfusion and nanoparticle retention within tumors, Hou et al. engineered an intelligent nanodrug that selectively depletes tumor-associated platelets to potentiate intratumoral drug penetration. It can respond to the MMP-2 with enzymatic activity on the surface of tumor vascular endothelium, achieving the targeted transport of anti-platelet antibody (R300) to tumor tissues. Furthermore, by specifically eliminating tumor-associated platelets, this carrier causes an increase in the porosity of tumor blood vessels, strengthening the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, and thereby promoting the infiltration and accumulation of the loaded drug (doxorubicin) in the tumor, effectively inhibiting the proliferation of mouse breast and lung cancer cells[133].

Furthermore, platelets and their derivatives, along with platelet-inspired nanoparticles, demonstrate superior tumor-targeting capabilities compared to traditional chemically synthesized nanocarriers. This advantage stems from the intrinsic ability of platelets to adhere to and aggregate at tumor sites. Related advancements will be discussed in detail in the following section.

Emergency treatments

Uncontrolled bleeding during major surgeries, accidents, and wars can quickly result in severe complications, such as hemorrhagic shock, organ dysfunction, and potentially fatal outcomes[104,134]. In civilian settings, hemorrhage is the leading cause of one-third of pre-hospital deaths[135]. Therefore, hemostasis is the primary concern in the prevention and treatment of acute injuries. The role of platelets in the physiological coagulation process is beyond doubt. Clinically, platelet transfusion is an important hemostatic treatment method, mainly used to replenish the reduction or functional abnormalities of platelets caused by diseases, trauma, etc., thereby restoring and maintaining the body’s hemostatic function. Moreover, PRP exosomes [PRP-extracellular vesicles (EVs)] have demonstrated significantly superior hemostatic efficacy compared to platelets, offering a new strategy for acute hemostatic intervention[12]. The surface procoagulant activity of PRP-EVs is approximately 50 to 100 times greater than that of activated platelets, attributed to their higher content of coagulation-related components, such as Factor X and prothrombin, as well as the enhanced surface PS exposure[136].

The specific receptor-ligand interactions of platelets provide a molecular foundation for the development of hemostatic materials. Following extensive research, numerous agents have been identified as capable of activating platelets. Collagen initiates platelet activation during primary hemostasis and promotes the activation of coagulation factors during secondary hemostasis. The hydrolysis of collagen into gelatin helps mitigate potential biological safety concerns associated with collagen. Currently, several types of hemostatic gelatin sponges have been introduced into clinical practice. These materials exert their hemostatic effects through concentration-dependent mechanisms - by increasing the local concentration of platelets and coagulation factors - and through intrinsic procoagulant activity[137]. Furthermore, extracellular matrix-based materials with excellent bioactivity and biocompatibility, containing collagen as the sole essential component, have demonstrated hemostatic potential and are capable of achieving simultaneous hemostasis and tissue repair[138]. In addition, the small molecule short peptide Thrombin Receptor Activator for Peptide 6 (TRAP6) can act as a potent platelet activator independently and stimulate platelet aggregation through the protease-activated receptors (PAR)-1 signaling pathway. TRAP6 immobilized on a Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) scaffold binds to the PAR-1 receptor on the platelet surface, triggering Ca2+ influx and α-granule release, and activating platelets (CD62p expression upregulated by 8 times)[139].

Chemical functional groups can also influence pro-coagulant properties. Studies have shown that hydrophobic alkyl chains can form strong hydrophobic interactions with platelet membranes. Such interactions also exist between alkyl chains and red blood cell membranes as well as bacterial membranes, which can enhance their hemostatic and anti-infective capabilities[140]. Meanwhile, electrostatic interactions with positively charged groups (-NH3 groups) can increase the adhesion of negatively charged platelets and also promote the rapid adhesion and aggregation of red blood cells at the injury site, facilitating thrombus formation. This is also one of the important mechanisms of chitosan's pro-coagulant activity[4].

However, it should be pointed out that the design targeting platelets is not the only approach in the development of hemostatic materials. Under pathological conditions such as thrombocytopathy and coagulation disorders, such designs are difficult to effectively activate the physiological coagulation process. Moreover, in scenarios of massive hemorrhage (such as arterial or cardiac injury), relying solely on physiological coagulation is insufficient to effectively control bleeding. At such times, physically sealing the wound through hemostatic materials is usually a key measure[141].

Platelet and its derivatives

Through innovative engineering strategies, platelets and their derivatives [such as PRP, platelet-derived EVs (pEVs), platelet membranes and platelet-mimicking materials] have been transformed into multifunctional biomaterials and delivery carriers. These strategies not only fully leverage the natural biological characteristics of platelets but also significantly enhance the application efficacy in various diseases, including hemostasis, anti-infection, tissue repair, anti-tumor, anti-inflammation, and targeted therapy, by integrating nanotechnology, materials science, and bioengineering approaches. This has demonstrated great potential for clinical translation.

Platelet and PRP

Platelets contain numerous growth factors and play a crucial role in tissue regeneration and repair. Researchers have prepared a platelet hydrogel by covalently amide cross-linking natural platelets with sodium alginate through a covalent amide cross-linking reaction. By repeated freeze-thawing and ultrasonic treatment, the amino groups on the platelet membrane were exposed, allowing them to undergo cross-linking reactions with the carboxyl groups of sodium alginate. By mimicking the physiological functions of platelets, platelet hydrogel has demonstrated significant advantages in hemostasis, antibacterial activity, and promoting tissue regeneration, and is expected to become an ideal wound dressing material[142].

In addition, due to the platelets’ tumor-targeting ability, vascular endothelial cell adhesiveness, and deep penetration, they are regarded as an ideal platform for constructing targeted drug delivery systems[143,144]. Liu et al. have designed a novel microneedle patch based on engineered platelets, combined with microwave-responsive magnetic bio-metal-organic framework nanomedicines (Fe3O4@MOF). It can be activated in the tumor microenvironment, triggering the release of platelet-derived microparticles (PMPs) and nanomedicines. Combined with microwave hyperthermia, it can effectively enhance cellular uptake and promote the deep penetration of drugs into tumors[145]. Similarly, the platelets’ targeting ability and engineering technology can be utilized to suppress tumors. Targeted protein degradation (TPD) technology degrades disease-related proteins directly, holding the potential to address complex diseases at their root. Chen et al. have developed a platelet-based TPD method. This method covalently links the specific ligand of the target degradation protein to heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) in the platelet. Based on the selective accumulation of protein degradation platelets (DePLTs) at the bleeding site, the labeled HSP90 can enter target cells through PMPs, thereby initiating the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and lysosomal pathways to degrade intracellular and extracellular proteins, respectively[146]. Wang et al. attached immune checkpoint inhibitory antibodies to the surface of platelets. The platelets aggregated and activated at the tumor resection site, releasing small particles carrying Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PDL1) antibodies, which acted on the primary residual tumor and circulating tumor cells in the body[147].

PRP is a platelet concentrate separated from fresh autologous whole blood through multiple centrifugation processes, containing a large amount of growth factors. Due to its ability to promote tissue repair, low immunogenicity, no risk of infectious disease transmission, and ease of preparation, PRP has been widely used in clinical practice in recent years. This will be summarized in detail in the following text. However, it faces numerous challenges: (1) PRP requires activation with thrombin and calcium chloride, which is transient and leads to factor burst release; (2) Once activated, PRP forms a gel that cannot be injected and cannot fully cover irregular wounds; (3) Limited mechanical properties result in easy collapse and degradation[148]. Therefore, ensuring the stability and injectability of PRP and guaranteeing the sustained release of growth factors are crucial for achieving clinical efficacy. The latest advancements in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine have promoted the application of PRP in treating various diseases by combining it with other biomaterials, including orthopedic regeneration therapy, skin wound repair, and hair regeneration. Qi et al. developed an injectable double-network hydrogel system (PRP@GEL) for endometrial repair. PRP can be locally activated by chelated Ca2+ in the hydrogel, and the growth factors released upon PRP activation can be encapsulated in the 3D hydrogel to further ensure the sustained release of growth factors[149].

Platelet-derived extracellular vesicles

EVs have shown great potential for the development of new therapies in the biomedical field. pEVs retain the characteristics of platelets, with multiple platelet membrane surface antigens (CD31, CD41, CD42, CD61, CD62, CD63) and PS on their membranes. At the same time, various functional substances are loaded, such as growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, nucleic acids {messenger RNA [mRNA] and microRNA [miRNA]}[150-152]. All these mediate the potential therapeutic applications of pEVs in hemostasis, tissue regeneration, and immune regulation, as well as their use as drug delivery carriers. Recently, allogeneic pEVs were used in the first human clinical trial as an experimental treatment for wound healing. They demonstrated activity in a series of in vitro wound healing assays and were safely applied in a phase I trial to assess safety in healthy volunteers[153].

These vesicles possess lipid bilayer membranes and nanoscale structures, which can be readily endocytosed by cells, enhancing bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. They also serve as platforms for drug loading and delivery and contain various nutritional factors that further boost their effectiveness. In eye drop formulations, they have been used to deliver the anti-angiogenic agent kaempferol (KM) to inhibit abnormal corneal vascular formation[154]. For tendon repair, loading YAP1 protein into these exosomes via electroporation promoted the stemness and differentiation potential of endogenous tendon stem/progenitor cells[155].

pEVs have the ability to target inflammation and, compared with platelets, can reach organs and tissues that platelets cannot access. Based on this property, researchers have developed treatments for various diseases. Platelet microparticles (PMs) loaded with anti-IL-1β antibodies were prepared for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction to neutralize the IL-1β surge. The results showed that PMs targeted the infarcted area and accumulated in the injured heart, thereby increasing the local concentration of anti-IL-1β antibodies. Anti-IL-1β platelet PMs (IL1-PMs) protected cardiomyocytes from apoptosis by neutralizing IL-1β and reducing IL-1β-driven caspase-3 activity. This study addressed the risk of severe side effects associated with conventional intravenous IL-1β blockers[156]. The anti-inflammatory drug TPCA-1 [a nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) inhibitor] was carried by pEVs. In a mouse model of acute lung injury (ALI), pEVs could selectively and efficiently target the pneumonia tissue, effectively inhibiting the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lungs and calming the local cytokine storm. Moreover, pEVs have been confirmed to serve as a universal drug delivery platform, selectively targeting various inflammatory sites, such as chronic atherosclerotic plaques, rheumatoid arthritis, and skin-related wounds[157]. Furthermore, research has found that compared with untreated tumors, pEVs can effectively target tumors treated with anti-PD-L1 therapy. They can serve as a drug delivery system for targeting myeloid cells in the tumor microenvironment after anti-PD-L1 treatment, thereby reversing acquired immune resistance to anti-PD-L1 therapy[158].

Activated platelet membrane vesicles exert antibacterial effects through multiple mechanisms in a coordinated manner including toxin neutralization, pathogen trapping, enhanced phagocytosis and induction of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). Bacteria can interact with platelets either by directly binding to platelet surface receptors such as GP Ibα, TLRs, GP IIbIIIa, and FcγRIIA, or indirectly through host plasma proteins such as vWF, fibronectin, and fibrinogen. After activation, the adhesion of activated platelets to pathogens and white blood cells is promoted through upregulated surface receptors such as

Platelet membrane

The platelet membrane is rich in numerous proteins that retain the adhesive properties of platelets. Membrane proteins can also promote the recruitment and differentiation of CD34+ cells (hematopoietic stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells) through direct and indirect mechanisms, including enhancing the adhesion of CD34+ cells to damaged tissues and increasing the level of SDF-1 in the kidneys with ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI)[160]. The multifunctional targeting ability of platelet membranes has become an attractive drug carrier in targeted delivery applications[161,162]. Li et al. targeted the “thrombosis-inflammation” vicious cycle that triggers acute ischemic stroke (AIS) onset, and selected autologous platelet membranes with natural vascular injury targeting and immunomodulatory properties, as well as the clinically approved immunomodulatory drug FTY720 (an S1P receptor modulator that can regulate microglial cell phenotypes) to construct a nano-system. This system can achieve lesion targeting, enhance blood-brain barrier penetration and enhance the uptake by inflammatory microglial cells, significantly improving drug delivery efficiency and ultimately reducing brain tissue damage[163]. An oral hydrogel microsphere modified with platelet membrane was prepared for targeted binding to exposed collagen

The platelet membrane has a classic phospholipid bilayer, which provides a basis for its fusion with other types of cell membranes[167]. The poor membrane stability of platelets leads to a short retention time in the body, which affects their therapeutic effect. Researchers have developed a liposome-platelet nano-platform (LP) for rapid hemostasis by taking advantage of the wound-targeting and hemostatic performance of platelet membranes and the superior stability of synthetic liposomes. The in vivo hemostatic effect of LP is better than that of platelet membranes or liposomes alone, which is attributed to the long circulation time provided by liposomes and the hemostatic activity conferred by platelet membranes[168]. In addition, researchers used a mixed biomimetic membrane composed of red blood cell membranes and platelet membranes to encapsulate nanoparticles to obtain lung-targeted antibacterial particles. On the one hand, red blood cell membranes can help the particles evade phagocytosis by macrophages; on the other hand, platelet membranes can target them to inflammatory sites and further specifically bind to drug-resistant bacteria, enhancing their targeting ability[169] [Figure 3A]. By hybridizing platelet and neutrophil membranes, researchers have designed a drug delivery system that can utilize the characteristics of cell membranes to achieve functions such as inflammation targeting, toxin/bacteria clearance, and immune regulation[170].

Figure 3. (A) mFe-CA nanoparticle-mediated antibacterial activity and therapeutic effect of acute pneumonia. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[169]. Copyright @ 2023, American Chemical Society; (B) Preparation of platelet decoys, with SEM (top) and TEM (bottom) images showing platelet morphology and ultrastructure. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[171]. Copyright @ 2019, American Association for the Advancement of Science. PRP: Platelet-rich plasma; PPP: platelet-poor plasma; SEM: scanning electron microscope; TEM: transmission electron microscope.

The procoagulant activity inherent in platelet membranes is a concern for causing dangerous thrombosis. Recently, Papa et al. removed the lipid outer membrane and internal contents of normal platelets, while retaining most of the surface adhesion proteins, describing the development of detergent-extracted human modified platelets (platelet decoys) that retain the adhesion function of platelets while eliminating their activation and aggregation capabilities. It is noteworthy that this effect is markedly distinct from the procoagulant activity of p-EVs, as it demonstrates anticoagulant properties. Due to the fact that the number and size of platelets in rabbit blood closely resemble those in human blood, rabbits serve as a suitable animal model for thrombosis studies. After platelet decoys were administered intravenously into rabbits at a defined ratio, they significantly inhibited thrombus formation upon induction of arterial injury[171] [Figure 3B].

Platelet-mimicking materials

Platelet transfusion and related materials have always been constrained by donor scarcity, difficulties in storage and transportation, risks of bacterial contamination, and a short shelf life. To break through these bottlenecks, a promising research direction focuses on developing micro/nanoparticle-based platelet-mimicking materials, aiming to simulate the multiple hemostatic mechanisms of platelets[172,173]. In recent years, the construction of artificial platelets by loading functional peptides onto carriers has emerged as a new hotspot in the field of hemostatic materials. This biomimetic strategy has demonstrated significant advantages such as ease of synthesis, controllable side effects, and potential for industrial production.

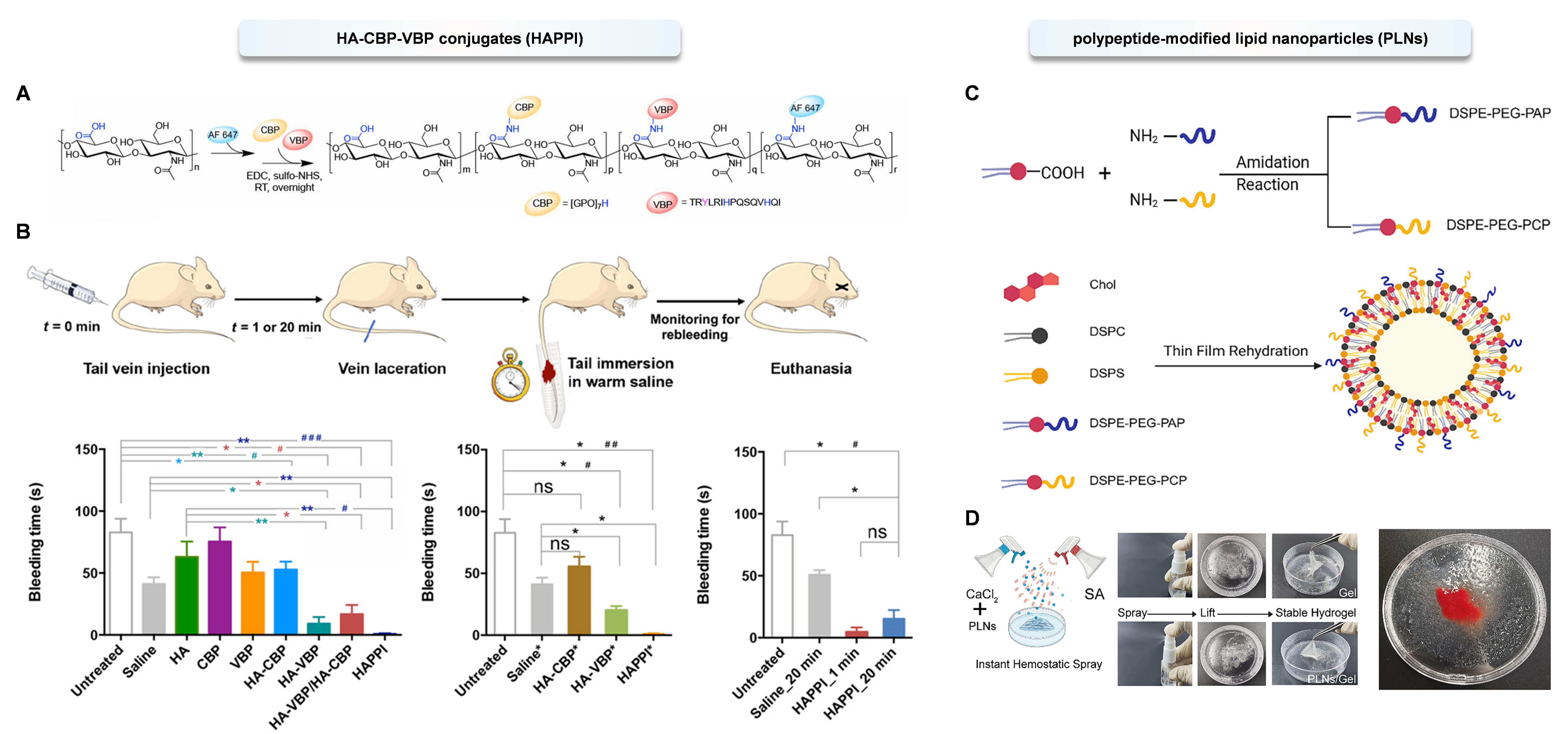

Inspired by the platelet coagulation mechanism, various active peptides have been successfully applied in the field of hemostasis. They promote blood coagulation and the hemostatic process by binding to specific molecules at the site of vascular injury[174]. An injectable hemostatic agent (HAPPI) has been reported, which is a conjugate of hyaluronic acid (HA) with collagen-binding peptide (CBP) and vWF-binding peptide (VBP), capable of achieving efficient hemostasis. This material can selectively bind to the exposed protein molecules vWF and collagen on damaged blood vessels and activated platelets, and enhance its accumulation at the bleeding site. In vivo studies in a mouse tail vein laceration model have shown that both BT and blood loss were reduced by more than 97%[175] [Figure 4A and B]. Platelet adhesion peptide (PAP, sequence: GFOGER) can be recognized and bound to the platelet surface by integrin GP Ia-IIa, mediating platelet adhesion and activation. Platelet cross-linking peptide (PCP, sequence: GGQQLK) binds to fibrin. When platelets bind and pull fibrin, Factor XIIIa catalyzes covalent cross-linking within fibrin, promoting thrombus retraction and the formation of stable blood clots. To enhance stability, PCP/PAP was modified on the surface of lipid nanoparticles and incorporated into hydrogels to simulate and enhance blood coagulation. The biocompatibility, degradability, and efficacy of this hydrogel were verified in a rodent model of non-compressible liver injury[176] [Figure 4C and D]. In addition, Nellenbach et al. constructed artificial platelet-mimicking materials (PLP) using super-soft and highly deformable nanogels conjugated with fibrin-specific antibody fragments. Even in cases of dilutional coagulopathy, these PLP can reduce blood loss, improve healing one week after injury, and are eventually cleared through the kidneys. These findings support the future translational research of such PLP in hemostatic therapy in trauma settings[177].

Figure 4. (A) Synthesis and characterization of AF 647-labeled HA-CBP-VBP conjugates (HAPPI). Reproduced with permission from Ref.[175]. Copyright © 2020, American Association for the Advancement of Science; (B) Hemostatic action of HA-peptide conjugates in mouse tail laceration model. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[175]. Copyright © 2020, American Association for the Advancement of Science; (C) Synthesis of the two lipopeptide conjugates containing PAP and PCP, and the construction of peptide-modified lipid nanoparticles (PLNs) via thin film rehydration. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[176]. Copyright © 2025, Wiley-VCH GmbH; (D) The PLNs are incorporated into a CaCl2-sodium alginate sprayable hydrogel crosslinked via ionic bonds. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[176]. Copyright © 2025, Wiley-VCH GmbH. Statistics by two-tailed, nonparametric Mann-Whitney test (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01) and Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (#P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.01). ns: Not significant. HA: Hyaluronic acid; CBP: collagen-binding peptide; VBP: von Willebrand factor (vWF)-binding peptide; RT: room temperature;

The morphology of nanomaterials also affects their hemostatic performance. Cubic artificial platelets (GS5-MOF) were constructed using biocompatible γ-cyclodextrin (CD) and the oligopeptide GRGDS (mimicking fibrinogen). The cubic GS5-MOF has a unique cubic shape, which breaks through the limitation of the spherical shape of previous carriers, effectively evades phagocytosis and clearance by macrophages, and improves targeting and hemostatic efficiency. In vivo studies have shown that cubic GS5-MOF is more effective than spherical CD nano-sponges of the same dose, indicating that the cubic shape of the GS5-MOF nanocarrier plays a crucial role in its efficient hemostasis[178].

Some researchers have pointed out that the natural platelet can only be programmed to bind to specific types of rare cells or proteins, which greatly reduces the speed of blood coagulation[179]. Based on this, researchers have developed a supramolecular polysaccharide nanoparticle that can imitate the structure of a platelet and exceed its coagulation function. It can simultaneously adhere to the main components of blood (red blood cells and albumin) and rapidly build a barrier in an ultrafast manner. It has achieved rapid hemostasis within 45 seconds in the liver and femoral artery bleeding of anticoagulant pigs, and can be immediately removed after hemostasis without causing secondary bleeding or postoperative adhesion at the wound site[180].

Clinical applications of platelets

Based on the previous review, platelets possess versatile bio-functions and may play an important role in disease treatment and tissue repair. Besides the transfusion of platelets for hemostasis, over the past few decades, PRP has attracted attention in many different medical fields worldwide. In particular, autologous PRP has a wide range of sources, poses no risk of immune reactions or donor microbial infections, and is highly conducive to its clinical application. It has been applied in many departments such as dentistry, maxillofacial surgery, orthopedics, sports medicine, dermatology, gynecology, ophthalmology, and neurology[181]. Here, the clinical effect of PRP mainly benefits from the various growth factors it is rich in. For instance, in clinical trials of dental implants, PRP has been used to stimulate bone formation or regenerate peripheral nerves. Clinical research results have shown that local application of PRP preparations during routine surgeries may accelerate the healing of soft and hard tissues at the implant site[182,183]. The growth factors in PRP are crucial for tissue repair by creating a microenvironment that promotes cell and tissue growth. A clinical trial applying a combination of platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) to patients with bilateral bone defects demonstrated a significant increase in bone filling in those who received a higher dose (150 μg/mL each of them) of the drug combination[184]. The application of PRP in the treatment of chronic diabetic ulcers has also been studied. A study on diabetic patients with chronic diabetic foot ulcers showed that after using local PRP gel for four weeks, the average ulcer area was significantly reduced to 51.9% of the baseline value[185]. For the treatment of dry eye syndrome, after one month of treatment, compared with the artificial tear group, the PRP group showed significant improvement in vision, with reduced conjunctival and corneal congestion and discoloration, demonstrating better efficacy[186].

At the same time, it is important to recognize that PRP is not universally effective for all medical conditions. Its therapeutic efficacy in osteoarthritis (OA) remains inconclusive. In a clinical trial involving 80 patients with hip OA, participants who received PRP injections experienced significant pain relief at both 6- and 12-month follow-ups; however, the observed improvements did not differ significantly from those achieved with HA treatment[187]. Therefore, although the effects of PRP are encouraging, its clinical application scope still needs to be confirmed through rigorous clinical trials. It should also be pointed out that the existing PRP therapy also has drawbacks. The composition of PRP has not been standardized. Its cellular components and growth factor content may vary due to different preparation techniques, which, to some extent, leads to the instability of clinical effects. Moreover, the current clinical application of platelets is mainly limited to PRP-related preparations. The application of platelet membranes, EVs, and related derivatives still requires further development.

Outlook

We provide an initial perspective on the future directions of platelet research: (1) Mechanism analysis driven by multi-omics technologies: Although the biological mechanisms of platelets in physiological and pathological processes have been extensively investigated, the complexity and systemic nature of these processes make it challenging for single-gene studies to comprehensively elucidate the molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying platelet physiology. In recent years, the integration of multi-omics technologies, such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, has provided novel insights and robust tools for systematically deciphering the diverse functions of platelets within the disease microenvironment; (2) Platelet-based disease prediction and targeted therapy: Through in-depth analysis of platelets, key therapeutic targets can be identified. Platelet-related molecules can be developed as biomarkers for the early diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of diseases. On the other hand, elucidating the key molecular mechanisms by which platelets participate in pathological processes provides precise targets for innovative therapies, such as platelet-mediated gene delivery systems; (3) Promoting the clinical application of platelet-related strategies: Currently, only a few strategies (such as PRP) have been translated into clinical practice, whereas a large number of innovative technologies remain at the preclinical stage. To accelerate the transition of these advanced technologies into clinical applications, it is essential to systematically characterize their pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profiles, optimize administration routes and storage conditions, and particularly address safety concerns, such as the risk of adverse thrombosis and potential interference with the autologous coagulation system.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this review summarizes research on the biological basis of platelets and their engineered applications, highlighting their multifunctional nature. Starting from basic theory, we have outlined platelet biology and their significant roles in a wide range of physiological and pathological processes. Furthermore, therapeutic strategies inspired by platelets have been systematically reviewed: on the one hand, treatments targeting platelets for cancer, cardiovascular disease, and hemostasis; on the other hand, applications leveraging the biological activity and characteristics of platelets, including various derivatives and artificial platelets. This review aims to draw more attention to the multifunctionality of platelets, opening new avenues for disease treatment and promoting medical progress.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

Some elements in the figures are created through BioRender.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, original draft writing, and review and editing: Zou CY, Deng YT, Lin XR, Xie HQ

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (324B2047), the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024NSFSC0002), and the “1.3.5” Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYGD23037).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Richman TR, Ermer JA, Baker J, et al. Mitochondrial gene expression is required for platelet function and blood clotting. Cell Rep. 2023;42:113312.

2. Bergmeier W, Hynes RO. Extracellular matrix proteins in hemostasis and thrombosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a005132.

3. Scherlinger M, Richez C, Tsokos GC, Boilard E, Blanco P. The role of platelets in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23:495-510.

4. Zou CY, Li QJ, Hu JJ, et al. Design of biopolymer-based hemostatic material: starting from molecular structures and forms. Mater Today Bio. 2022;17:100468.

5. Leung J, Strong C, Badior KE, et al. Genetically engineered transfusable platelets using mRNA lipid nanoparticles. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eadi0508.

6. Caudrillier A, Kessenbrock K, Gilliss BM, et al. Platelets induce neutrophil extracellular traps in transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2661-71.

8. Li X, Fries S, Li R, et al. Differential impairment of aspirin-dependent platelet cyclooxygenase acetylation by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16830-5.

9. Tyagi T, Jain K, Gu SX, et al. A guide to molecular and functional investigations of platelets to bridge basic and clinical sciences. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2022;1:223-37.

10. Fang J, Wang X, Jiang W, et al. Platelet-rich plasma therapy in the treatment of diseases associated with orthopedic injuries. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2020;26:571-85.

11. Wang T, Yi W, Zhang Y, et al. Sodium alginate hydrogel containing platelet-rich plasma for wound healing. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2023;222:113096.

12. Wu J, Piao Y, Liu Q, Yang X. Platelet-rich plasma-derived extracellular vesicles: a superior alternative in regenerative medicine? Cell Prolif. 2021;54:13123.

13. White JG, Krumwiede MD, Cocking-Johnson DJ, Escolar G. Dynamic redistribution of glycoprotein Ib/IX on surface-activated platelets. A second look. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1057-67.

14. White JG, Escolar G. Current concepts of platelet membrane response to surface activation. Platelets. 1993;4:175-89.

15. Sixma JJ, Slot JW, Geuze HJ. [26]Immunocytochemical localization of platelet granule proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1989;169:301-11.

17. Ruiz FA, Lea CR, Oldfield E, Docampo R. Human platelet dense granules contain polyphosphate and are similar to acidocalcisomes of bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44250-7.

19. White JG, Krivit W. An ultrastructural basis for the shape changes induced in platelets by chilling. Blood. 1967;30:625-35.

20. Escolar G, Krumwiede M, White JG. Organization of the actin cytoskeleton of resting and activated platelets in suspension. Am J Pathol. 1986;123:86-94.

22. Gerrard JM, White JG, Peterson DA. The platelet dense tubular system: its relationship to prostaglandin synthesis and calcium flux. Thromb Haemost. 1978;40:224-31.

24. Noetzli LJ, French SL, Machlus KR. New insights into the differentiation of megakaryocytes from hematopoietic progenitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:1288-300.

26. Long MW, Williams N, Ebbe S. Immature megakaryocytes in the mouse: physical characteristics, cell cycle status, and in vitro responsiveness to thrombopoietic stimulatory factor. Blood. 1982;59:569-75.

27. Machlus KR, Italiano JE Jr. The incredible journey: from megakaryocyte development to platelet formation. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:785-96.

28. Bender M, Thon JN, Ehrlicher AJ, et al. Microtubule sliding drives proplatelet elongation and is dependent on cytoplasmic dynein. Blood. 2015;125:860-8.

29. Thon JN, Montalvo A, Patel-Hett S, et al. Cytoskeletal mechanics of proplatelet maturation and platelet release. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:861-74.

30. Kaushansky K, Lok S, Holly RD, et al. Promotion of megakaryocyte progenitor expansion and differentiation by the c-Mpl ligand thrombopoietin. Nature. 1994;369:568-71.

31. Zhang L, Orban M, Lorenz M, et al. A novel role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor S1pr1 in mouse thrombopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2165-81.

32. Zhang H, Nimmer PM, Tahir SK, et al. Bcl-2 family proteins are essential for platelet survival. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:943-51.

33. Fujii T, Sakata A, Nishimura S, Eto K, Nagata S. TMEM16F is required for phosphatidylserine exposure and microparticle release in activated mouse platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:12800-5.

34. Suzuki J, Umeda M, Sims PJ, Nagata S. Calcium-dependent phospholipid scrambling by TMEM16F. Nature. 2010;468:834-8.