A baseline-lymphocyte-subset nomogram for predicting severe immune-related adverse events in hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving TACE plus immunotherapy

Abstract

Aim: This study aimed to construct and validate a nomogram model to predict the occurrence of severe immune-related adverse events (sirAEs) (≥ 3 grade) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients receiving transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus immunotherapy.

Methods: Data regarding lymphocyte subpopulations and clinical characteristics of 130 HCC patients treated from January 2020 to June 2024 were retrospectively analyzed, including 46 patients with sirAEs and 84 patients without sirAEs. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to summarize the factors that might affect the occurrence of sirAEs in patients, and then these factors were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. These influencing factors were then included in the construction of the nomogram prediction model. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and calibration curves were used to verify the nomogram prediction model.

Results: Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that liver cirrhosis, lower value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Regulatory T cell, and higher value of lymphocytes and creatinine were significantly associated with sirAEs (P < 0.05). Based on these factors, a nomogram prediction model for predicting sirAEs after TACE plus immunotherapy in HCC patients was constructed. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for the prediction model was 0.885 (95% confidence interval: 0.820-0.951), with a cut-off value of 137.786. The model demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.812 and a specificity of 0.889.

Conclusion: The nomogram model developed in this study shows promising predictive performance for sirAEs in HCC patients receiving TACE plus immunotherapy; however, further validation in larger, multi-center prospective cohorts is needed to confirm its generalizability and clinical utility.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents approximately 75%-85% of primary liver cancer cases and is the sixth most common malignancy globally[1]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have become important treatments for advanced HCC. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC, 2022) guideline recommends first-line immune-targeted therapy with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab or dual immunotherapy with durvalumab plus tremelimumab for patients with stage B (diffuse, invasive, bilobar extensive metastases) and C HCC. Guidelines also recommend ramucirumab in HCC patients with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) ≥ 400 mg/mL after failure of first-line therapy[2]. In the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) guideline, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab, durvalumab or pembrolizumab are recommended as first-line treatments for patients with Child-Pugh Class A[3].

Locoregional therapy combined with systemic treatment has become an established strategy in advanced HCC and has delivered substantial clinical benefit[4]. Among these approaches, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) stands out as the cornerstone of locoregional therapy for intermediate-stage HCC and is strongly endorsed by multiple international guidelines[2,3]. For advanced HCC, the Chinese and Japanese guidelines also recommend the individualized use of TACE as a locoregional palliative therapy[5,6].

ICIs enhance the cytotoxicity of immune cells, thereby promoting the elimination of cancer cells. However, they may also excessively enhance the normal immune response of patients, which may lead to disorders of the immune system, and then lead to the occurrence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs)[7]. Beyond this, TACE reshapes the immune microenvironment of HCC, thereby modulating both the efficacy of subsequent immunotherapy and the incidence of associated irAEs. The mortality rate of severe irAEs (sirAEs) (≥ 3 grade) has reached 2%[8]. sirAEs seriously increase the economic and physical burden of patients. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to predict these patients who are prone to developing sirAEs before therapy. In this study, a nomogram prediction model was constructed based on pre-therapeutic lymphocyte subpopulation data and clinical characteristics of HCC patients to predict the occurrence of sirAEs following TACE combined with immunotherapy.

METHODS

Study design and patients

Data regarding lymphocyte subpopulations and clinical characteristics of 156 HCC patients treated from January 2020 to June 2024 were retrospectively analyzed. After applying predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 46 HCC patients who developed sirAEs were assigned to the sirAEs group, while 84 HCC patients without sirAEs served as the control group. Blood was obtained from the patient's fasting venous blood within 1 week before immunotherapy. Multicolor flow cytometry was employed to perform quantitative analysis of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets. All operations were completed in the Laboratory Department of Jiangsu Provincial Cancer Hospital. TACE was repeated only when imaging unequivocally demonstrated residual or recurrent viable tumor. Inclusion criteria: (1) patients with clinically or pathologically confirmed HCC according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines; (2) patients received more than one cycle of ICIs; (3) patients received TACE on demand. (4) HCC at stage BCLC stage B (patients with diffuse, infiltrative, extensive HCC liver involvement) or C; (5) informed consent has been obtained; (6) life expectancy ≥ 6 months; (7) patients had complete clinical data. Exclusion criteria: (1) serious medical diseases (severe hypertension and diabetes, heart failure, thyroid dysfunction, etc.) before immunotherapy; (2) unable to cooperate with the investigators; (3) medical records could not be collected completely; (4) combined with two or more primary malignant tumors.

Treatment procedure

Enrolled patients received one of five intravenous ICIs: tislelizumab, pembrolizumab, camrelizumab, sintilimab, or toripalimab. Tislelizumab, pembrolizumab, camrelizumab, and sintilimab were administered at a fixed dose of 200 mg every 21 days, whereas toripalimab was given at a fixed dose of 240 mg on the same schedule. TACE was repeated strictly on demand, prompted by radiologic evidence of viable tumor. Laboratory profiles were monitored monthly, and contrast-enhanced MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or CT (computed tomography) was obtained every 1-3 months in all patients.

Outcomes and assessments

sirAEs were defined as severe immune dysregulation adverse events (grade ≥ 3) such as thyroid dysfunction, immune-related pneumonitis, rash, and myocarditis that occurred during or after immunotherapy. irAEs were evaluated by investigators without prior knowledge of the relevant information using the “Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 5.0” of the National Cancer Institute to obtain data on the type and grade of irAEs.

Statistical analysis

SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 26.0 and R software were used to analyze all statistical data. Analysis of variance, chi-square test and t-test were used to analyze the clinical data. A binary logistic regression model was used to analyze the correlation between clinical risk factors and the occurrence of sirAEs in HCC patients. According to the influencing factors obtained by multivariate logistic regression

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 46 HCC patients who developed sirAEs between January 2020 and June 2024 were included in the sirAEs group, and 84 HCC patients who did not develop sirAEs were included in the control group. There were 22 patients with Child-Pugh = 5 in the sirAEs group and 57 patients with Child-Pugh = 5 in the control group. The number of patients with Child-Pugh > 5 in the sirAEs group was significantly more than that in the control group (P < 0.05). There were 13 patients with cirrhosis in the sirAEs group and 57 patients with cirrhosis in the control group. The incidence of liver cirrhosis was significantly higher in the sirAEs group than that in the control group (P < 0.01). Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) in the sirAEs group was 1.79 ± 1.16, and NLR in the control group was 3.42 ± 1.58. NLR was significantly elevated in the control group relative to the sirAEs group (P < 0.05). The number of Regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the sirAEs group and the control group was 6.07 ± 4.97 and 9.79 ± 5.24, respectively. The number of Tregs in the control group was significantly higher than that in the sirAEs group (P < 0.05). The number of lymphocytes in the sirAEs group and control group was 37.43 ± 16.39 and 25.50 ± 11.72, respectively. The number of lymphocytes in sirAEs group was significantly higher than that in the control group (P < 0.05). The level of creatinine in the sirAEs group was 58.23 ± 25.86, which was significantly higher than that in the control group (44.18 ± 31.87, P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed between the two groups with regard to the remaining clinical indicators (P ≥ 0.05) [Table 1].

Baseline characteristics and clinical features (n = 130)

| sirAE group, n (%) N = 46 | Control group, n (%) N = 84 | P | |

| Age, years | 0.661 | ||

| < 60 | 21 (45.65) | 35 (41.67) | |

| ≥ 60 | 25(54.35) | 49 (58.33) | |

| Gender | 0.830 | ||

| Female | 7 (15.22) | 14 (16.67) | |

| Male | 39 (84.78) | 70 (83.33) | |

| BCLC stage | 0.098 | ||

| B | 16 (34.78) | 18 (21.43) | |

| C | 30 (65.22) | 66 (78.57) | |

| HBV | 0.200 | ||

| No | 10 (21.74) | 11 (13.10) | |

| Yes | 36 (78.26) | 73 (86.90) | |

| ECOG PS | 0.476 | ||

| 0 | 40 (86.96) | 69 (82.14) | |

| > 0 | 6 (13.04) | 15 (17.86) | |

| Child-Pugh | 0.025 | ||

| 5 | 22 (47.83) | 57 (67.86) | |

| > 5 | 24 (52.17) | 27 (32.14) | |

| Cirrhosis | 0.000 | ||

| No | 13 (28.26) | 52 (61.90) | |

| Yes | 33 (71.74) | 32 (38.10) | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0.434 | ||

| < 400 | 23 (50.00) | 36 (42.86) | |

| ≥ 400 | 23 (50.00) | 48 (57.14) | |

| CD4/CD8 | 2.65 ± 2.63 | 2.09 ± 1.15 | 0.094 |

| NK | 20.19 ± 9.43 | 21.37 ± 8.96 | 0.483 |

| B | 8.27 ± 5.61 | 9.35 ± 4.39 | 0.227 |

| NLR | 1.79 ± 1.16 | 3.42 ± 1.58 | 0.000 |

| NKT | 3.60 ± 3.77 | 3.89 ± 3.48 | 0.661 |

| Treg | 6.07 ± 4.97 | 9.79 ± 5.24 | 0.000 |

| Lymphocytes | 37.43 ± 16.39 | 25.50 ± 11.72 | 0.000 |

| CD3 | 69.26 ± 14.08 | 67.56 ± 12.61 | 0.481 |

| CD4 | 35.78 ± 8.38 | 37.80 ± 9.16 | 0.218 |

| CD8 | 31.23 ± 11.26 | 29.75 ± 9.05 | 0.415 |

| TBIL | 12.93 ± 8.57 | 13.06 ± 8.93 | 0.938 |

| DBIL | 6.95 ± 5.20 | 7.87 ± 4.90 | 0.317 |

| ALT | 19.34 ± 8.83 | 19.54 ± 7.56 | 0.890 |

| AST | 23.46 ± 10.45 | 22.95 ± 10.72 | 0.794 |

| Cr | 58.23 ± 25.86 | 44.18 ± 31.87 | 0.012 |

| ALB | 41.55 ± 7.29 | 42.18 ± 7.54 | 0.647 |

In the sirAEs group, patients were treated with tislelizumab (n = 14), pembrolizumab (n = 10), camrelizumab (n = 10), sintilimab (n = 6), and toripalimab (n = 6). In the control group, treatments included tislelizumab (n = 25), pembrolizumab (n = 20), camrelizumab (n = 13), sintilimab (n = 12), and toripalimab (n = 14).

Types of sirAEs

In the sirAEs group, complications included hand-foot skin rash (n = 7), hypertension (n = 5), proteinuria (n = 3), diarrhea (n = 7), hypothyroidism (n = 8), and gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 4). Furthermore, five patients showed increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 5 showed increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and 8 showed increased total bilirubin. Among these, five patients demonstrated elevated AST and ALT levels simultaneously, one of whom also presented with concomitant hyperbilirubinemia.

Predictors of sirAEs

Univariate binary logistic regression analysis showed that Child-Pugh score, liver cirrhosis, NLR, Tregs, lymphocytes, and creatinine were significantly correlated with sirAEs (P < 0.05) [Table 2]. These six significant factors were subsequently included in a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. The results identified liver cirrhosis, NLR, Tregs, lymphocytes, and creatinine as independent influencing factors for sirAEs (P < 0.05) [Table 3].

Univariate analysis of factors associated with immune-related adverse events in HCC patients

| β | s | Waldχ2 | EXP(B) | 95%CI | P | |

| Age, years < 60/≥ 60 | -0.162 | 0.370 | 0.192 | 0.850 | 0.412-1.755 | 0.850 |

| Gender Female/Male | 0.108 | 0.504 | 0.046 | 1.114 | 0.415-2.993 | 0.830 |

| BCLC B/C | -0.671 | 0.408 | 2.701 | 0.511 | 0.230-1.138 | 0.100 |

| HBV No/Yes | -0.612 | 0.482 | 1.610 | 0.542 | 0.211-1.395 | 0.205 |

| ECOG PS 0/> 0 | -0.371 | 0.522 | 0.505 | 0.690 | 0.248-1.921 | 0.477 |

| Child-Pugh 5/> 5 | 0.843 | 0.376 | 4.911 | 2.303 | 1.101-4.816 | 0.027 |

| Cirrhosis No/Yes | 1.417 | 0.397 | 12.733 | 2.757 | 1.894-8.984 | < 0.001 |

| AFP (ng/mL) < 400/≥ 400 | -0.288 | 0.368 | 0.610 | 0.750 | 0.364-1.543 | 0.750 |

| CD4/CD8 | -0.187 | 0.127 | 2.152 | 0.830 | 0.646-1.065 | 0.142 |

| NK | 0.014 | 0.021 | 0.499 | 1.015 | 0.975-1.056 | 0.480 |

| B | 0.050 | 0.042 | 1.444 | 1.052 | 0.969-1.142 | 0.230 |

| NLR | 0.819 | 0.167 | 24.126 | 2.268 | 1.636-3.145 | < 0.001 |

| NKT | 0.023 | 0.053 | 0.196 | 0.658 | 0.923-1.135 | 0.658 |

| Treg | 0.159 | 0.045 | 12.629 | 1.172 | 1.074-1.279 | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes | -0.061 | 0.015 | 17.203 | 0.941 | 0.914-0.968 | < 0.001 |

| CD3 | -0.010 | 0.014 | 0.503 | 0.990 | 0.963-1.018 | 0.478 |

| CD4 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 1.526 | 1.026 | 0.985-1.070 | 0.217 |

| CD8 | -0.015 | 0.019 | 0.671 | 0.985 | 0.950-1.021 | 0.413 |

| TBIL | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.006 | 1.002 | 0.961-1.044 | 0.937 |

| DBIL | 0.038 | 0.038 | 1.009 | 1.039 | 0.964-1.120 | 0.315 |

| ALT | 0.003 | 0.023 | 0.020 | 1.003 | 0.959-1.050 | 0.889 |

| AST | -0.005 | 0.017 | 0.070 | 0.995 | 0.962-1.030 | 0.792 |

| Cr | -0.015 | 0.006 | 6.055 | 0.985 | 0.973-0.997 | 0.014 |

| ALB | 0.012 | 0.025 | 0.213 | 1.012 | 0.963-1.062 | 0.644 |

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with immune-related adverse events in HCC patients

| β | s | Waldχ2 | EXP(B) | 95%CI | P | |

| Child-Pugh | 0.595 | 0.546 | 1.189 | 1.813 | 0.622-5.288 | 0.276 |

| Cirrhosis | 1.171 | 0.555 | 4.447 | 3.226 | 1.086-9.578 | 0.035 |

| NLR | 0.776 | 0.191 | 16.414 | 2.172 | 1.492-3.160 | < 0.001 |

| Treg | 0.111 | 0.056 | 4.007 | 1.118 | 1.002-1.247 | 0.045 |

| Lymphocytes | -0.036 | 0.018 | 4.235 | 0.964 | 0.932-0.998 | 0.040 |

| Cr | -0.023 | 0.009 | 6.970 | 0.978 | 0.962-0.994 | 0.008 |

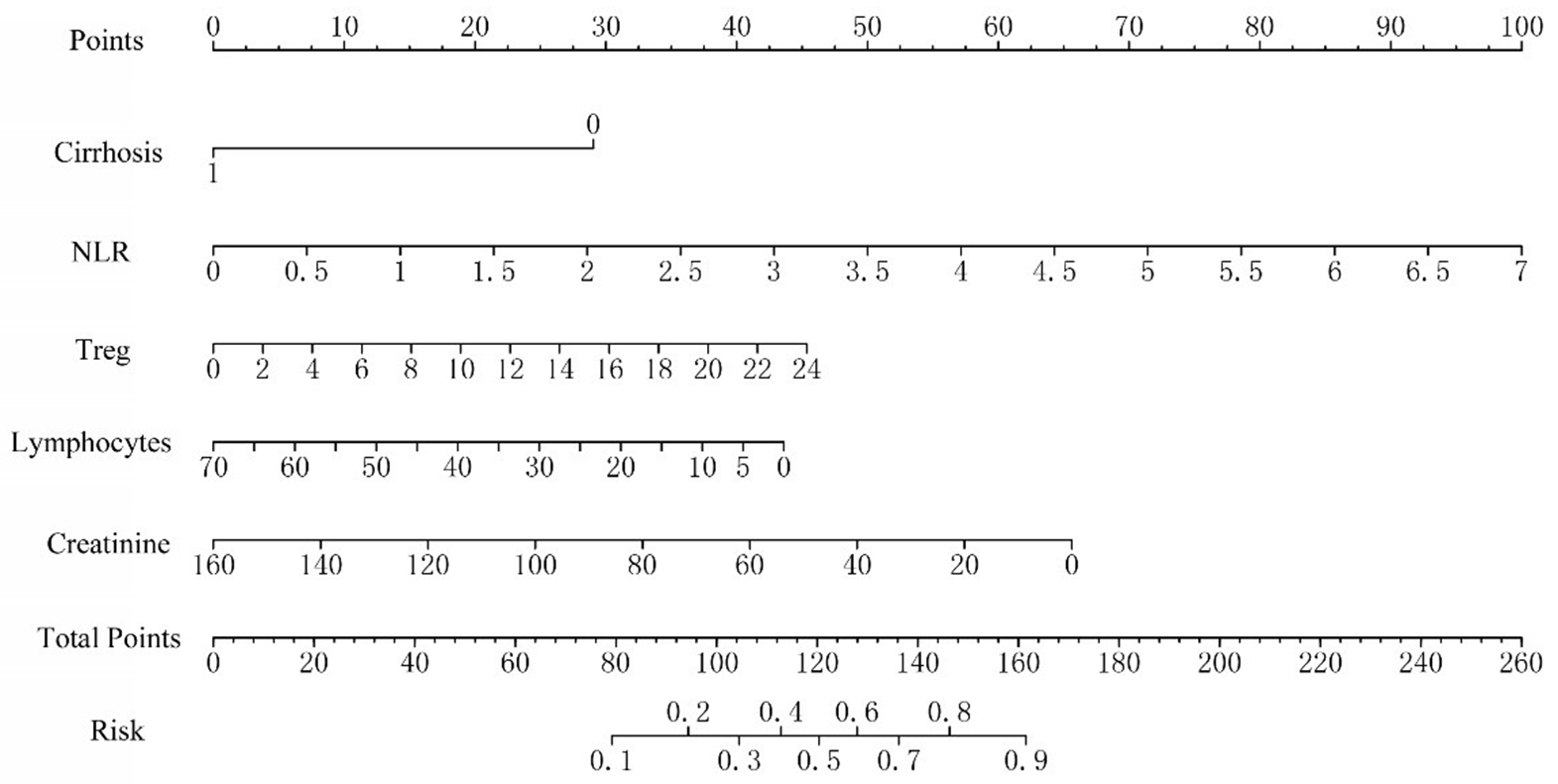

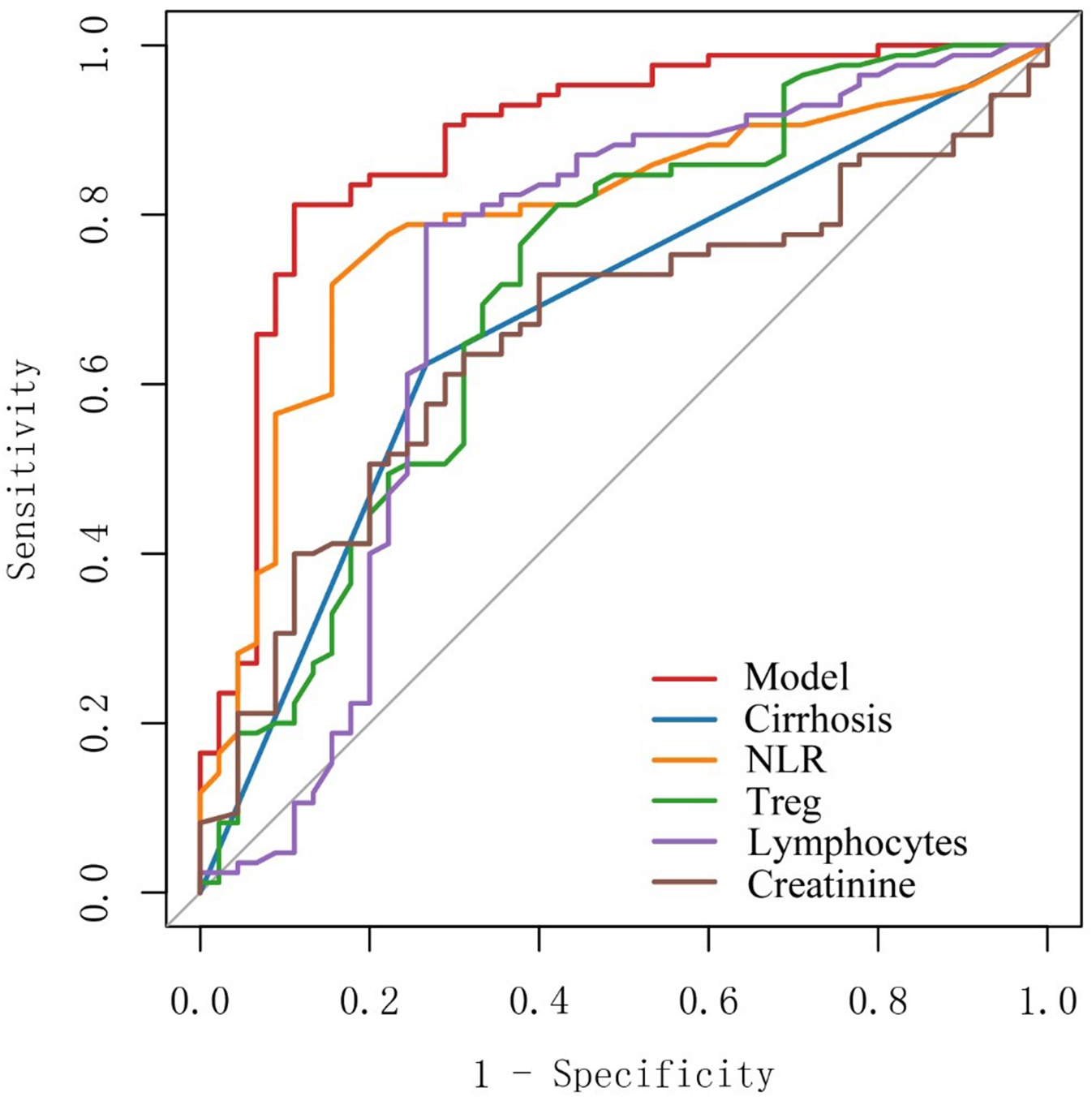

Construction and verification of nomogram prediction model

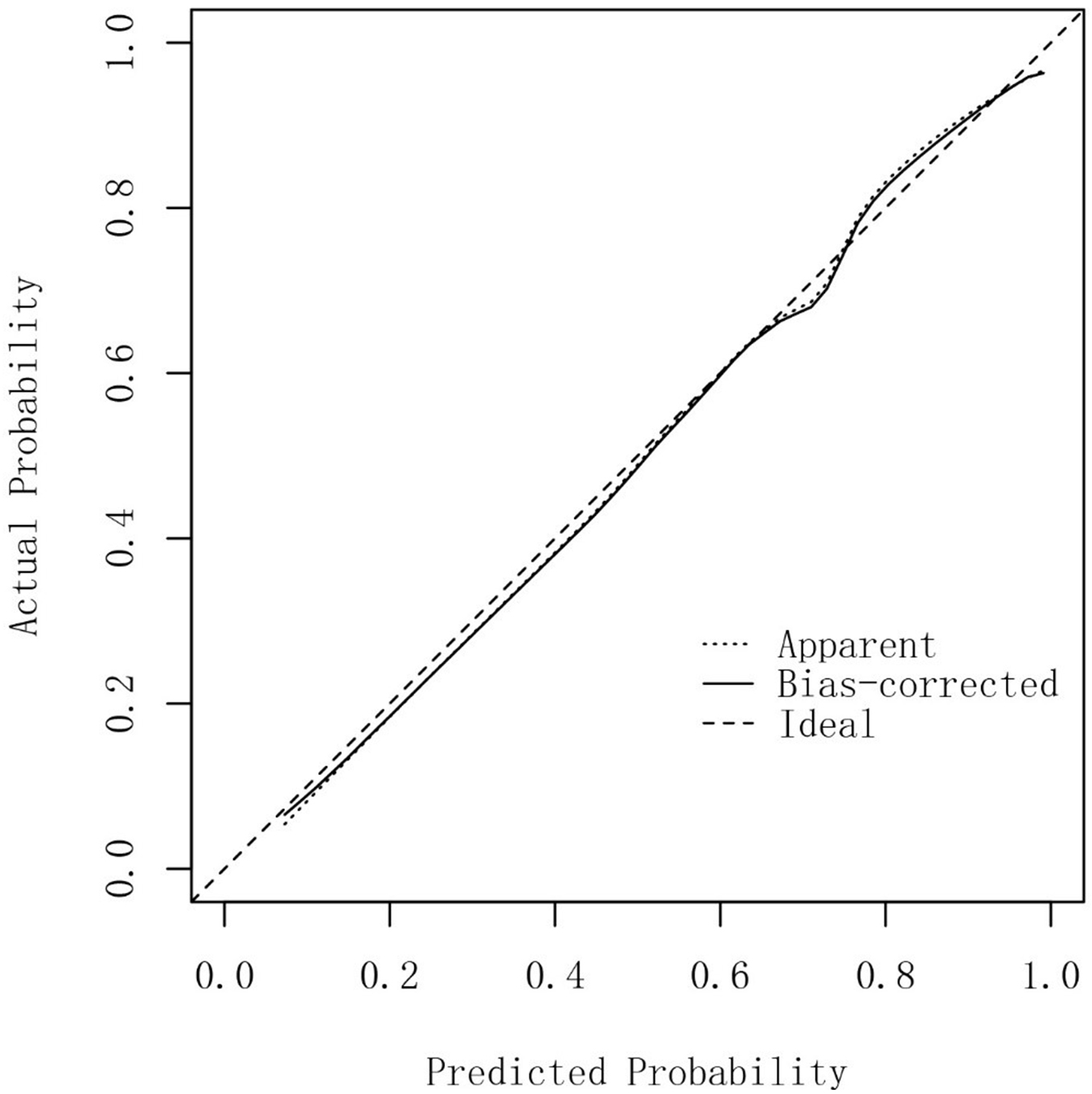

A nomogram prediction model was constructed based on the five independent influencing factors obtained from the multivariate binary logistic regression analysis including liver cirrhosis, NLR, Treg, lymphocytes, and creatinine [Figure 1]. Figure 2 showed that the area under the ROC curve (AUC) values of the prediction model were significantly higher than those of the other five independent predictors. The AUC of the model was 0.885 (95% confidence interval: 0.820-0.951). The model’s sensitivity and specificity were 81.2% and 88.9%, respectively. The cut-off value of the model was 137.786 [Table 4]. The total score of the nomogram ranges from 80 to 160 points, corresponding to a predicted probability of 0.1 to 0.9. When the total score is ≥ 137.786, the model demonstrates a sensitivity of 81.2% and a specificity of 88.9% in the training set, with a corresponding predicted probability of approximately 0.52. This indicates that the patient's risk of developing sirAEs is significantly elevated. The calibration curve in Figure 3 shows that there is no significant difference between the fitted curve of the nomogram model and the ideal curve, and the agreement is high, suggesting the good predictive effect of the model.

Figure 1. Nomogram for predicting severe immune-related adverse events following TACE plus immunotherapy in HCC patients. TACE: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; Treg: regulatory T cell.

Figure 2. Area under the ROC curve (AUC) for the nomogram predictive model. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; Treg: regulatory T cell.

Figure 3. Calibration curve of the nomogram prediction model for severe immunotherapy-related adverse events in HCC patients. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

ROC values of clinical indicators and the predictive model

| Variable | AUC | 95%CI | Sensitivity | Specificity | Cut-off |

| Model | 0.885 | 0.820-0.951 | 0.812 | 0.889 | 137.786 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.678 | 0.595-0.762 | 0.624 | 0.733 | 0.5 |

| NLR | 0.793 | 0.711-0.874 | 0.718 | 0.844 | 2.55 |

| Treg | 0.713 | 0.615-0.811 | 0.812 | 0.578 | 5.1 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.717 | 0.610-0.824 | 0.788 | 0.733 | 31.75 |

| Cr | 0.661 | 0.566-0.757 | 0.729 | 0.600 | 56.4 |

DISCUSSION

Immunotherapy has become an important treatment modality for HCC. However, while it enhances antitumor immune activity, it may also excessively amplify normal immune responses, leading to immune dysregulation and the subsequent development of sirAEs[9]. As a pivotal locoregional therapy, TACE markedly improves survival in HCC when combined with immunotherapy. Yet it simultaneously remodels the tumor immune microenvironment into a more intricate landscape, making the onset of sirAEs increasingly unpredictable for clinicians. Hence, an effective and readily applicable predictive model for sirAEs is urgently required.

A total of 46 HCC patients with sirAEs and 84 HCC patients without sirAEs were enrolled in this study. The lymphocyte subpopulation and clinical characteristics of these patients were analyzed, and a nomogram prediction model was established based on these data. The AUC value of the prediction model established in this study was 0.885 and the sensitivity was 0.812, which was significantly better than that of a single factor. This study showed that the proportion of cirrhosis was significantly higher in the sirAEs group, and cirrhosis was an independent influencing factor for sirAEs. Patients with cirrhosis were more likely to develop sirAEs. In liver cirrhosis, the immune function of the liver itself is often abnormal, and it is more likely to cause systemic immune dysfunction during immunotherapy[10]. Mild systemic inflammatory phenotypes in cirrhosis-related immune dysfunction can lead to excessive inflammatory response, which may be one of the causes of sirAEs[11]. In addition, pro-inflammatory mediators and vascular osmotic mediators may be produced in liver cirrhosis, which may induce the accumulation of neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils and monocytes in the liver, leading to immune disorders and the occurrence of sirAEs[12,13]. However, this study showed that the reliability of cirrhosis in predicting sirAEs after immunotherapy in HCC patients was not high, because its AUC value was 0.678 and its sensitivity was 0.733, so the prediction strength of cirrhosis alone was not high. In this study, the number of lymphocytes in the sirAEs group was significantly higher than that in the control group, and a lymphocyte count > 31.75 was an independent influencing factor for sirAEs, which may be related to the higher prevalence of liver cirrhosis in the sirAEs group. The observed association between elevated lymphocyte counts and increased incidence of irAEs in patients receiving combined TACE and immunotherapy may be attributed to their potential synergistic effect on immune activation. One possible mechanism is a speculated synergistic effect. In this model, TACE could function to prime the immune response by releasing tumor antigens and creating a pro-inflammatory microenvironment. Subsequently administered checkpoint inhibitors might then augment this primed response by removing inhibitory signals, potentially leading to an amplified and systemic T-cell activation. Studies have also found that high levels of lymphocytes at baseline are associated with ≥ grade 2 sirAEs[14], and Egami also found that high levels of lymphocytes at two weeks after immunotherapy may predict the development of sirAEs[15]. Treg cells are a small but important subset of CD4+ T cells, which are one of the main components of the immune microenvironment. Treg cells can regulate the strength of the body's immune response by inhibiting the activity and function of effector T cells, so as to maintain the body's immune balance[16]. In the setting of TACE combined with immunotherapy - where antigen release and inflammatory signals from TACE coincide with immune checkpoint inhibition - a relatively low level of Treg cells may fail to adequately constrain the ensuing T-cell activation. This could plausibly lead to an amplified and less controlled immune response, potentially contributing to a higher incidence of irAEs. Treg cells in the sirAEs group were significantly less than those in the control group (6.07 ± 4.97 vs. 9.79b ± 5.24, P < 0.05), and a low level of Treg cells was an independent risk factor for sirAEs. Patients with Treg < 5.1 had a significantly increased risk of sirAEs. Research shows that depleting Treg cells triggers systemic effects and leads to sirAEs[17]. At the same time, some studies have shown that in melanoma patients receiving immunotherapy, Treg cells in the blood of patients with sirAEs are significantly reduced[18]. After transient depletion of Treg cells in mice, mice are more susceptible to sirAEs[19]. These results are consistent with the conclusions of our study.

Creatinine is a metabolic byproduct produced by skeletal muscle during energy metabolism; it is primarily filtered from the blood and excreted by the kidneys. Elevated baseline serum creatinine levels, indicating impaired renal function, may slow the clearance of pro-inflammatory cytokines produced during TACE in HCC patients. This delayed clearance could potentially prolong and amplify systemic immune activation and inflammatory status, thereby increasing the risk and severity of irAEs. In this study, creatinine in the sirAEs group was 58.23 ± 25.86, which was significantly higher than that in the control group (44.18 ± 31.87). This may suggest that patients with poor renal function reserve are more likely to develop sirAEs after immunotherapy. Previous studies have also shown that high levels of creatinine are more likely to lead to acute kidney injury after immunotherapy[20]. NLR reflects the balance between tumor inflammatory response and antitumor immunity. This study showed that NLR in the sirAEs group was 1.79 ± 1.16, which was significantly lower than 3.42 ± 1.58 in the control group. NLR was an independent risk factor for sirAEs, and its AUC was 0.793. Studies have shown that a high level of NLR is closely associated with a reduction in the incidence of irAEs (≥ 2 grade) after immunotherapy for HCC[21], which is consistent with the conclusion observed in a variety of other malignant tumors[21-26]. Some studies have reported that a high NLR is associated with increased toxicity, which contrasts with our findings. This discrepancy may stem from the distinct treatment context of our study, which involved HCC patients receiving combined TACE and immunotherapy. In this specific setting, a low baseline NLR may reflect an immune system that is not overly suppressed or exhausted by chronic inflammation. As a result, when primed by the potent antigen release and inflammatory cascade induced by TACE, such an immune system may mount a more vigorous and effective lymphocytic proliferation and activation in response to subsequent immune checkpoint inhibition. This “overly effective” immune activation, while enhancing antitumor response, could also more readily break self-tolerance, thereby predisposing patients to sirAEs.

Although our prediction model provides valuable prognostic information, it also has some limitations. First, our study sample came from a single medical center and lacked external validation in a large population or across regions, which may limit the external validity of the results. Second, because this study was retrospective and relied on available medical records, some of the test data were not comprehensive enough. Finally, some patients received immunotherapy and targeted therapy at the same time, so the occurrence of sirAEs in some patients cannot exclude the factor of targeted therapy. We look forward to designing and conducting multi-center prospective studies in the future for validation. Despite its limitations, this model can predict the occurrence of IRE using readily available clinical data, making it easier to implement in clinical practice.

In conclusion, by collecting data of lymphocyte subsets and clinical characteristics of HCC patients before immunotherapy, the nomogram prediction model for predicting the occurrence of sirAEs in HCC can effectively help clinicians to identify HCC patients who are likely to develop sirAEs.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Material preparation, data collection and analysis: Yu Z, Leng B, You R, Diao L

Writing the first draft of the manuscript: Yu Z

Contributing to the conception and design of the study: Yu Z, You R, Wang C, Leng B, Diao F, Xu Q, Yin G

Commenting on the previous versions of the manuscript: Yu Z, You R, Wang C, Leng B, Diao F, Xu Q, Yin G

Yin G is the corresponding author of this study. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All the data included in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Ethics Committee of Jiangsu Cancer Hospital has approved this research (2022-076). Informed consent has been obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Tu J, Wang B, Wang X, et al. Current status and new directions for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. Liver Res. 2024;8:218-36.

2. Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681-93.

3. Benson AB, D’Angelica MI, Abbott DE, et al. Hepatobiliary cancers, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:541-65.

4. Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, et al. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:151-72.

5. Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer (2022 edition). Liver Cancer. 2023;12:405-44.

6. Kudo M, Kawamura Y, Hasegawa K, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: JSH consensus statements and recommendations 2021 update. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:181-223.

7. Yin Q, Wu L, Han L, et al. Immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1167975.

8. Villadolid J, Amin A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-75.

9. Okiyama N, Tanaka R. Immune-related adverse events in various organs caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Allergol Int. 2022;71:169-78.

10. Chennamadhavuni A, Abushahin L, Jin N, Presley CJ, Manne A. Risk factors and biomarkers for immune-related adverse events: a practical guide to identifying high-risk patients and rechallenging immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol. 2022;13:779691.

11. Hartl L, Simbrunner B, Jachs M, et al. Lower free triiodothyronine (fT3) levels in cirrhosis are linked to systemic inflammation, higher risk of acute-on-chronic liver failure, and mortality. JHEP Rep. 2024;6:100954.

12. Hasa E, Hartmann P, Schnabl B. Liver cirrhosis and immune dysfunction. Int Immunol. 2022;34:455-66.

13. Irvine KM, Ratnasekera I, Powell EE, Hume DA. Causes and consequences of innate immune dysfunction in cirrhosis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:293.

14. Diehl A, Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee E, Grossman SA. Relationships between lymphocyte counts and treatment-related toxicities and clinical responses in patients with solid tumors treated with PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. Oncotarget. 2017;8:114268-80.

15. Egami S, Kawazoe H, Hashimoto H, et al. Absolute lymphocyte count predicts immune-related adverse events in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab monotherapy: a multicenter retrospective study. Front Oncol. 2021;11:618570.

16. Aso K, Kono M, Kanda M, et al. Itaconate ameliorates autoimmunity by modulating T cell imbalance via metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2023;14:984.

17. Eschweiler S, Ramírez-Suástegui C, Li Y, et al. Intermittent PI3Kδ inhibition sustains anti-tumour immunity and curbs irAEs. Nature. 2022;605:741-6.

18. Lepper A, Bitsch R, Özbay Kurt FG, et al. Melanoma patients with immune-related adverse events after immune checkpoint inhibitors are characterized by a distinct immunological phenotype of circulating T cells and M-MDSCs. Oncoimmunology. 2023;12:2247303.

19. Liu J, Blake SJ, Harjunpää H, et al. Assessing immune-related adverse events of efficacious combination immunotherapies in preclinical models of cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5288-301.

20. Isik B, Alexander MP, Manohar S, et al. Biomarkers, clinical features, and rechallenge for immune checkpoint inhibitor renal immune-related adverse events. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:1022-31.

21. Dharmapuri S, Özbek U, Jethra H, et al. Baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio appear predictive of immune treatment related toxicity in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;15:1900-12.

22. Pavan A, Calvetti L, Dal Maso A, et al. Peripheral blood markers identify risk of immune-related toxicity in advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Oncologist. 2019;24:1128-36.

23. Lee PY, Oen KQX, Lim GRS, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts development of immune-related adverse events and outcomes from immune checkpoint blockade: a case-control study. Cancers. 2021;13:1308.

24. Fujimoto A, Toyokawa G, Koutake Y, et al. Association between pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and immune-related adverse events due to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:2198-204.

25. Sue M, Takeuchi Y, Hirata S, Takaki A, Otsuka M. Impact of nutritional status on neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of efficacy and adverse events of immune check-point inhibitors. Cancers. 2024;16:1811.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].