Exploring the molecular pathology and tumor microenvironment in gastric cancer liver metastasis

Abstract

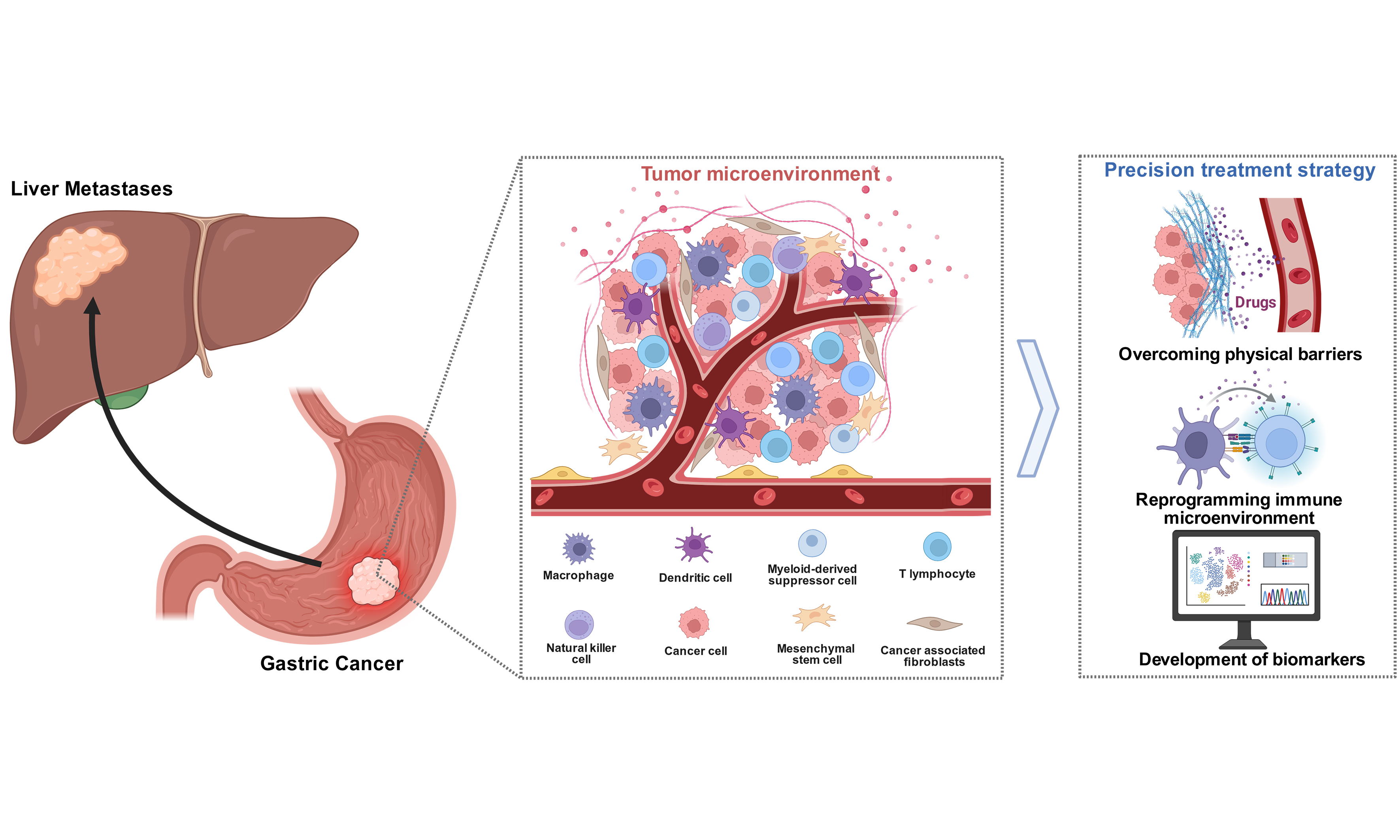

The liver is the most common metastatic site of gastric cancer, and liver metastasis is one of the leading causes of death in patients with gastric cancer, characterized by a complex and unique tumor microenvironment (TME). The molecular classification and pathological characteristics of gastric cancer provide a basis for its research and treatment. The dynamic remodeling mechanisms of the TME involve multiple aspects, including stromal cell reprogramming, immune microenvironment characteristics, and regulation of the extracellular matrix and mechanical forces. The clinical challenges of gastric cancer liver metastasis (GC-LM) are severe, and effective intervention strategies need to be proposed, including overcoming physical barriers, precision therapies targeting the microenvironment, and biomarker development. In the future, integrating multi-omics and spatial dynamic analyses and establishing a molecular pathology-clinical translation feedback loop will be essential directions and challenges in this field. This review summarizes the research progress on the TME of GC-LM from clinical molecular pathology to precision medicine, aiming to provide a theoretical basis and new insights for the precision therapy of GC-LM.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer, a common global malignancy with high incidence and mortality, often presents with liver metastasis in advanced stages, a key factor in poor prognosis. The diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer liver metastasis (GC-LM) face many clinical challenges, as traditional treatments such as surgery and chemotherapy have limited efficacy. It is urgent to explore the underlying molecular mechanisms to find more effective therapeutic strategies. The liver, the main target organ for hematogenous metastasis of gastric cancer, provides a “soil” for tumor cell colonization and proliferation with its unique microenvironment. The classic “seed and soil” theory shows that metastasis formation depends on the complex dynamic interactions among disseminated tumor cells, the pre-metastatic niche (PMN), and the metastatic tumor microenvironment (TME)[1,2].

In recent years, the development of molecular pathology has gradually revealed the molecular classification and pathological characteristics of gastric cancer, laying the foundation for precision medicine. As a key player in tumor development, the TME plays a crucial role in GC-LM. It is a complex and dynamic system composed of stromal cells, immune cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), and other components. Their interactions together shape the tumor growth and metastasis environment[3]. Stromal cells play an essential role in TME reprogramming by secreting various cytokines and growth factors to promote tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis[4]. The immune microenvironment also has great significance in GC-LM. The functional state and distribution of immune cells are closely related to tumor progression and prognosis. The regulation of the ECM and mechanical forces affects the physical and chemical interactions between tumor cells and the microenvironment, thereby influencing tumor growth and metastasis[5].

In-depth research on microenvironment-mediated tumor metastasis mechanisms can help develop more effective precision therapeutic strategies targeting the microenvironment, improving treatment response and survival rates[6]. Additionally, biomarker development is a current research hotspot. Identifying biomarkers that reflect TME characteristics and treatment responses can facilitate individualized treatment plans and provide more precise options for patients[7]. This review will systematically elaborate on the dynamic reconstruction mechanisms of the TME in GC-LM from the perspective of molecular pathology and precision medicine, and explore intervention strategies and new target development based on TME biomarkers, offering new ideas for the precision treatment of gastric cancer patients.

GC-LM POSES SIGNIFICANT CLINICAL CHALLENGES

The liver is the most common site of distant metastasis for gastric cancer (GC) and is widely reported as the primary target for hematogenous metastasis globally[8,9]. Studies indicate that approximately 4%-14% of GC patients present with liver metastasis at initial diagnosis[10], and the incidence of metachronous liver metastasis after radical gastrectomy can reach up to 37%[11]. In East Asia, where GC incidence is among the highest worldwide, liver metastasis is particularly prevalent in these patients, significantly increasing disease aggressiveness and mortality[12,13].

The current clinical management of GC-LM faces numerous challenges. Firstly, patients with GCLM have an inferior prognosis, with a significant reduction in survival rates after liver metastasis, and the 5-year overall survival rate is less than 27%[14]. It is mainly due to the TME promoting rapid tumor progression and drug resistance[15]. Secondly, there are limitations in systemic therapy for GC. Currently, chemotherapy remains the main treatment plan, but it has limited efficacy[16]. Although molecular studies have revealed potential targets - such as Cyclin E1 (CCNE1) amplification, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway activation, and the C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)/C-X-C chemokine receptor type 7 (CXCR7) axis - targeted therapy remains in the exploratory stage, with bottlenecks in clinical translation[17-19]. Moreover, a universally applicable predictive model for liver metastasis is lacking. While some studies have proposed predictive models based on clinical parameters [such as serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels] or radiomics models, large-scale clinical cohorts are needed for validation[20,21].

MOLECULAR TYPING AND PATHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF GASTRIC CANCER

GC is a highly heterogeneous disease, and its diverse biological behaviors, prognoses, and treatment responses necessitate a sophisticated classification system. To move beyond traditional histopathology, molecular typing based on genomic and transcriptomic features has become essential for understanding the underlying drivers of the disease and guiding precision medicine. The molecular classification of GC is primarily defined by two major systems: The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG) [Table 1].

The molecular classification of gastric cancer defined by TCGA and ACRG

| Classification system | Subtype | Key molecular features | Pathological characteristics | Clinical behavior | Treatment strategies |

| TCGA[22-32] | EBV-positive | EBV genome integration, extensive DNA hypermethylation, PIK3CA mutations, overexpression of JAK2, PD-L1, and PD-L2; lymphoid stroma background | Mixed or diffuse type (Lauren); presence of lymphoid stroma; no specific histologic subtype emphasized beyond stromal feature | Low tendency for peritoneal metastasis; relatively better prognosis | Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-L1/PD-L2; potential PI3K inhibitors for PIK3CA mutations |

| MSI-H | Defective MMR system, MLH1 promoter methylation, high mutational burden | Intestinal type (Lauren); relatively well-differentiated; tubular structures; associated with Helicobacter pylori infection, AG, and IM | Low propensity for hematogenous (e.g., liver) metastasis; favorable prognosis | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (first-line option due to high mutational burden and PD-L1 expression) | |

| GS | Frequent CDH1 mutations (leading to loss of cell adhesion); no widespread aneuploidy or high mutational burden | Diffuse type (Lauren); typically signet-ring cell carcinoma; highly invasive; poorly differentiated | High tendency for peritoneal metastasis; poor prognosis | Chemotherapy (e.g., taxanes, platinum-based regimens); no specific targeted therapies highlighted | |

| CIN | Widespread aneuploidy, TP53 mutations, amplification of receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., HER2, EGFR) | Intestinal type (Lauren); relatively well-differentiated; tubular structures; associated with H. pylori infection, AG, and IM | High propensity for hematogenous dissemination (especially liver metastasis); poor prognosis | HER2-targeted therapy (if HER2-amplified); chemotherapy (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin); potential anti-EGFR agents | |

| ACRG[33-37] | MSI-H | Similar to TCGA MSI-H: defective MMR, MLH1 promoter methylation; likely overlapping molecular features | Intestinal type (Lauren); consistent with TCGA MSI-H pathological traits (well-differentiated, tubular structures) | Favorable prognosis; low metastatic risk | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (aligned with TCGA MSI-H treatment logic) |

| MSS/TP53+ | Preserved TP53 function; may overlap with EBV-associated features (implied by TCGA-ACRG complementarity); no high mutational burden | Mixed histological features (not strictly tied to single Lauren type); no specific precancerous lesions emphasized | Intermediate prognosis; no prominent metastatic pattern highlighted | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (if EBV-associated, analogous to TCGA EBV-positive); chemotherapy as baseline | |

| MSS/TP53- | TP53 mutations (loss of function), potential amplification of MDM2, MYC, or ERBB2; microsatellite stable status | Overlaps with TCGA CIN subtype: intestinal type (Lauren); well-differentiated tubular structures | High propensity for liver metastasis (consistent with CIN overlap); poor prognosis | HER2-targeted therapy (if ERBB2-amplified); chemotherapy (e.g., platinum-based, 5-fluorouracil) | |

| MSS/EMT | Features of EMT, loss of CDH1 (similar to TCGA GS), low mutational burden | Overlaps with TCGA GS subtype: diffuse type (Lauren); signet-ring cell carcinoma; highly invasive | High tendency for peritoneal metastasis; strong invasiveness, high recurrence rates; worst prognosis among ACRG subtypes | Chemotherapy (e.g., taxanes for aggressive phenotypes); potential targeted therapy against EMT pathways (e.g., TGF-β inhibitors) |

The TCGA framework divides GC into four main molecular subtypes. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive type is characterized by viral genome integration and extensive DNA hypermethylation, and often presents with PIK3CA (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha) mutations, as well as overexpression of Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and programmed death-ligand 2 (PD-L2), in a background of lymphoid stroma[22]. The microsatellite instability (MSI)-high (MSI-H) subtype is defined by a defective mismatch repair system, leading to a high mutational burden and MutL homolog (MLH1) promoter methylation[23]. In contrast, the genomically stable (GS) type is frequently associated with E-cadherin gene (CDH1) mutations, while the chromosomally unstable (CIN) type is characterized by widespread aneuploidy, tumor protein p53 (TP53) mutations, and amplification of receptor tyrosine kinases[24,25].

These molecular subtypes often correlate with the traditional Lauren classification, which remains pathologically significant. The MSI-H and CIN subtypes are commonly seen in intestinal-type GCs, which present with tubular structures, are relatively well-differentiated, and are often associated with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, atrophic gastritis (AG), and intestinal metaplasia (IM) as precancerous conditions[23,26-28]. Conversely, the GS subtype is often associated with the diffuse type, which is typically signet-ring cell carcinoma, is highly invasive, and is linked to CDH1 gene mutations that cause a loss of cell adhesion[29-31]. Some studies have further reported that overexpression of DNA polymerase β (POLB) is closely associated with the intestinal subtype and the MSI molecular subtype, suggesting that abnormalities in DNA repair may drive this pathological heterogeneity[32].

Complementing the TCGA system, the ACRG classification introduced the microsatellite stability (MSS)/EMT subtype, which is characterized by features of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, strong invasiveness, high recurrence rates, and a strong association with peritoneal metastasis[33,34]. Recent studies have further expanded on molecular-based classification. For example, Zeng et al. proposed an Epigenetic Modification-Associated Molecular Classification (EMMC) system that classifies GC into three subtypes - nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF)1, NMF2, and NMF3 - based on epigenetic gene expression, with the NMF2 subtype showing significantly better overall survival[38]. Separately, Wang et al. developed an immune phenotype score (IPS) system based on five key immune-related molecules - tryptophanyl-transfer RNA synthetase (WARS), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2L6 (UBE2L6), granzyme B (GZMB), basic leucine zipper ATF-like transcription factor 2 (BATF2), and lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3) - categorizing patients into immune-activated (IA) IPSLow and immune-silenced IPSHigh groups, which helps predict prognosis and immunotherapy response[39].

These molecular and pathological classifications have profound implications for understanding the distinct biological behaviors of GC, including metastatic patterns and treatment response, as different subtypes exhibit clear preferences for metastatic routes explained by distinct molecular and cellular mechanisms. For instance, the stroma of intestinal-type GC is rich in stromal degradation factors such as urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1/9), suggesting that it is more prone to hematogenous dissemination to the liver[40]. This propensity for liver metastasis is further linked to specific cell adhesion molecules and proteolytic enzymes; studies suggest that the expression of cell adhesion molecules and their ligands in the liver - as well as the activity of enzymes such as MMPs and the uPAR system - plays significant roles in facilitating the attachment and invasion of tumor cells to hepatic tissue[41,42]. The focal adhesion kinase/protein kinase B (FAK/AKT) signaling pathway has also been implicated in promoting adhesion and metastasis of GC to the liver via MMP-2/9 pathways[43]. This aligns with the observation that the CIN subtype, which is often intestinal-type, is linked to liver metastasis. In contrast, diffuse-type GC more commonly metastasizes via the peritoneal route, a tendency associated with significantly reduced levels of these stromal factors[40]. This distinct metastatic pathway is often associated with the loss or downregulation of cell-cell adhesion molecules such as E-cadherin, which allows tumor cells to detach from the primary tumor and disseminate into the peritoneal cavity. Once in the peritoneum, these cells must survive, proliferate, and adhere to peritoneal surfaces, with molecules such as α3β1 integrin and epithelial cellular adhesion molecule (EpCAM) being important mediators of GC cell adhesion to the peritoneum. Meanwhile, the uPAR system has also been implicated in facilitating tumor cell adhesion and migration within the peritoneal cavity[44]. This metastatic preference is reflected in molecular classifications, as the GS subtype (often diffuse type) and the ACRG MSS/EMT subtype are associated with peritoneal dissemination.

Certain subtypes possess specific pathological characteristics strongly linked to a high potential for liver metastasis. As a special subtype, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive GC, characterized by HER2 protein overexpression, exhibits rapid tumor proliferation and is more likely to present with recurrence and liver metastasis compared to HER2-negative cases[45]. Rare epithelial-derived subtypes also show a high propensity for liver metastasis. Papillary adenocarcinoma, which constitutes 2.7%-9.9% of cases, typically presents as an exophytic mass and has a high propensity for liver metastasis and a poor prognosis; a portion of these are the AFP-positive type with enteroblastic differentiation[46,47]. Similarly, hepatoid adenocarcinoma, which resembles hepatocellular carcinoma with elevated AFP levels, also carries a high risk of liver metastasis and a poor prognosis but can be distinguished using Cytokeratin (CK)19/20 markers[48]. Furthermore, patients with signet ring cell carcinoma have a higher rate of liver metastasis, which is often accompanied by PD-L1 expression and mutations in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway and TP53, increasing the likelihood of developing treatment resistance[49].

Molecular classification is crucial for guiding precision therapy. Research has shown that the MSI and EBV subtypes are particularly responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). The MSI subtype has the highest number of mutation events and tumor mutation burden, along with strong PD-L1 expression, while the EBV subtype exhibits recurrent mutations in AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A) and PIK3CA with fewer TP53 mutations, making both ideal candidates for immunotherapy[50]. This is further supported by immune-based classifications, such as the IPS system, where the IA IPSLow group is associated with a better response to anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) immunotherapy[36]. Conversely, understanding molecular features can also predict treatment failure; for instance, high expression of the key gene PIP4P2 (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase 2) from the EMMC classification has been identified as an independent predictor of poor prognosis and inadequate response to immunotherapy[35].

In summary, the integration of molecular and pathological classifications provides a comprehensive framework for understanding GC. These systems not only define the biological characteristics of tumors but also predict clinical behaviors, such as metastatic potential and therapeutic response. Accurate identification of pathological, molecular (e.g., EBV, MSI-H), and clinical characteristics, including those of rare subtypes, is paramount for formulating personalized treatment strategies. Moving forward, clinical tools such as the prediction model developed by Huang et al., which incorporates variables including Lauren classification and histological type, will help clinicians perform individualized risk assessments for outcomes such as liver metastasis, enabling timely adjustments to treatment strategies and improved patient prognosis[8].

DYNAMIC REMODELING MECHANISMS OF THE TME

Reprogramming of stromal cells

In GC, the reprogramming of stromal cells is central to the dynamic remodeling of the TME, involving multiple cell types and complex pathway changes. The TME composition constantly evolves, with stromal cells such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) reprogramming through interactions with tumor cells to take on a pro-tumor phenotype. Research has found that the interactions between malignant endothelial cells (ECs) and CAF subtypes are carried out through specific ligand-receptor pairs, such as midkine (MDK)-nucleolin (NCL), MDK-syndecan-2 (SDC2), serine protease 3 (PRSS3)-coagulation factor II receptor (F2R), and MDK-low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1). In contrast, normal ECs tend to communicate with CAF subtypes through macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF)-atypical chemokine receptor 3 (ACKR3)[51]. As the leading stromal cell group, CAFs can promote tumor metastasis, stemness, and chemoresistance by secreting factors while inhibiting anti-tumor immune responses, showing significant heterogeneity[52].

Subsets of CAFs with high expression of podoplanin (PDPN) promote GC metastasis by secreting periostin (POSTN). POSTN activates the FAK/AKT signaling pathway to regulate cancer stem cells and also induces GC cells to secrete interleukin (IL)-6 via the FAK/Yes-associated protein (YAP) signaling pathway. In turn, IL-6 activates the PI3K/AKT pathway in PDPN (+) CAFs, forming a positive feedback loop that enhances metastatic capacity[53]. In the TME, POU6F2 (POU class 6 homeobox 2) promotes hepatic metastasis of GC through dual mechanisms: transcriptional upregulation of Snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1) and induction of the transformation of hepatic stellate cells (HStCs) into CAFs via the insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2)/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway[54]. CAFs can enhance the Warburg effect in GC cells by secreting lysyl oxidase (LOX), maintain a transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1)-LOX positive feedback loop with tumor cells, promote the growth of hepatic metastatic lesions, and indicate poor prognosis[55]. The SERPINE2 (Serpin Family E Member 2) protein, secreted by CAFs, is involved in promoting immunosuppression and resistance to immunotherapy in the TME[56]. CAFs not only promote tumor progression and immune suppression through cytokine secretion [such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), fibroblast growth factor-7 (FGF-7), etc.] and direct interaction with T cells but can also form a complex cell interaction network with tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3-positive (LAMP3+) dendritic cells (DCs)[57].

Furthermore, GC-associated MSCs (e.g., bone marrow-derived MSCs) are reprogrammed into a pro-tumorigenic state in the TME and can promote metastasis through multiple pathways: for example, after being activated by macrophages, they acquire a pro-inflammatory phenotype to enhance the carcinogenesis of gastric epithelial cells; they secrete IL-8 and platelet-derived growth factor-DD (PDGF-DD), and promote GC metastasis via pathways such as nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and AKT, as well as exosomal microRNAs (miRNAs)[58]. GC cells promote the stability and expression of colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF2) messenger RNA (mRNA) in MSCs by modulating IGF2 mRNA-binding protein 2 (IGF2BP2)-mediated N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification, which in turn induces the transformation of MSCs into a pro-tumor phenotype. This process promotes GC cell proliferation, migration, and drug resistance through the secretion of various pro-inflammatory factors[59]. Studies by Chen et al. have shown that co-culturing with MSCs can increase the expression of natriuretic peptide receptor-A (NPRA) in GC cells. It, in turn, protects mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) from degradation and promotes its mitochondrial localization, enhancing mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) activity. As a result, more energy and biosynthetic intermediates are provided for GC cells, thereby promoting their self-renewal ability and resistance to the toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs[60]. Circ_0024107, derived from mesenchymal stem cells, can also promote lymphatic metastasis of GC cells through miR-5572/6855-5p/carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A)-mediated FAO metabolic reprogramming[61]. The reprogramming of these tumor stromal cells ultimately leads to immune suppression and heterogeneity in the TME, affecting treatment responses and disease progression.

Characteristics of the immune microenvironment

The characteristics of the immune microenvironment in the dynamic remodeling mechanism of the GC TME involve complex interactions of multiple cellular components and molecular signals. The tumor immune microenvironment of GC includes immune cells such as macrophages, T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and B cells, which mutually regulate each other in space and time to form an immunosuppressive state[62,63].

Among them, the polarization of macrophages (switching from pro-inflammatory M1 type to immunosuppressive M2 type) is a core feature that reshapes the microenvironment by secreting cytokines, promoting immunosuppression and drug resistance[64]. Legumain secreted by GC cells (sLGMN) can interact with Integrin αvβ3 on the surface of M2-type macrophages. This binding event triggers activation of the PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) signaling pathway, in turn driving the polarization of macrophages from the M1 to the M2 phenotype. This polarization process is coupled with metabolic reprogramming, which enhances the immunosuppressive activity of TAMs, reshapes the immune microenvironment of GC, and ultimately results in the cancer’s resistance to PD-1 monoclonal antibody therapy[65]. Studies by Jiang et al. have shown that extracellular vesicles (EVs) secreted by macrophages carry nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which, after being taken up by CAFs, induces deacetylation of Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) via sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), leading to decreased stability and nuclear expression of NICD protein, thereby inhibiting the transcriptional activation of nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT). This mechanism weakens CAF-induced T-cell dysfunction and restores the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells[66]. In addition, the interaction between CC chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2+) fibroblasts and STAT3-activated macrophages in the GC microenvironment can promote tumor progression and immunosuppression[67].

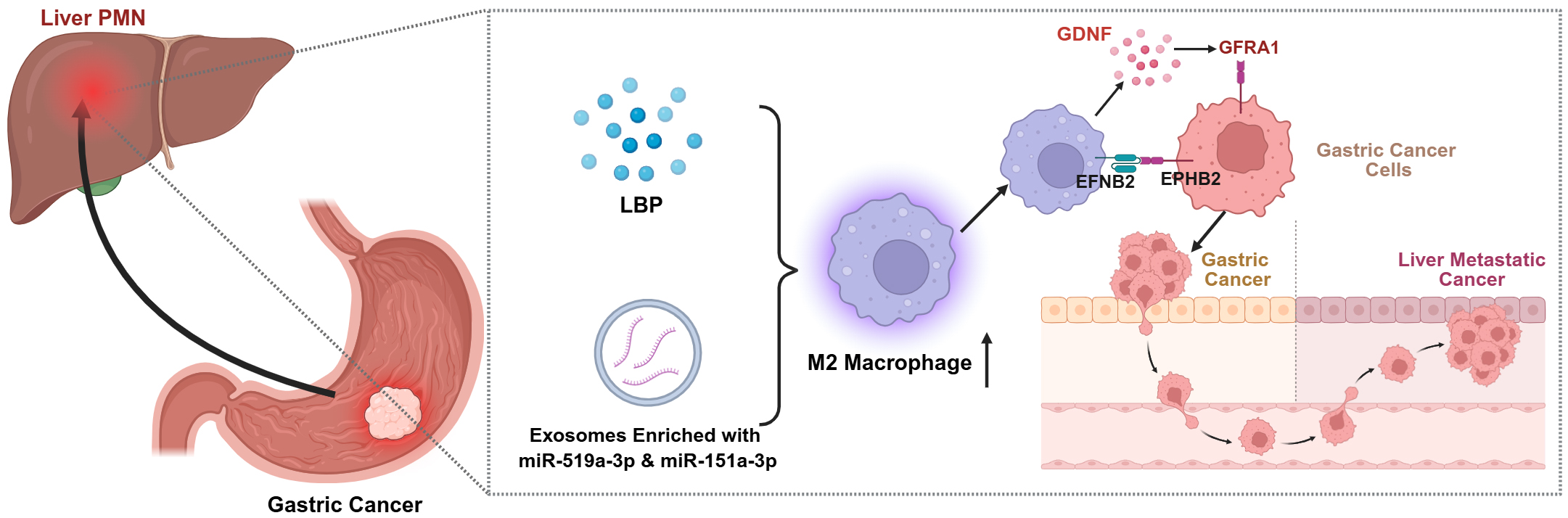

TAMs also play a critical role in GC metastasis. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 (MAPK4) silencing in GC drives liver metastasis through a positive feedback loop between cancer cells and macrophages[68]. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP) originating from GC cells enables crosstalk between primary GC cells and the hepatic microenvironment. It achieves this by stimulating hepatic macrophages to secrete TGF-β1, which in turn triggers the development of PMNs in the liver. Ultimately, this process promotes the hepatic metastasis of GC[69]. GC-derived exosomal miR-519a-3p and miR-151a-3p promote the formation of hepatic PMNs and GC-LM by inducing M2-like macrophages in the liver[70,71]. Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) is secreted by TAMs, and it specifically binds to GDNF receptor alpha 1 (GFRA1) receptors expressed on GC cell membranes. Through a non-classical, rearranged during transfection (RET)-independent pathway, this molecular interaction adjusts the function of lysosomes and the flow of autophagy. Such adjustments not only support GC cell survival when the cells are subjected to metabolic stress but also drive the progression of liver metastasis[72]. Studies by Li et al. have demonstrated that TAMs express ephrinB2 (EFNB2), which binds to ephrin type-B receptor 2 (EphB2) on GC cells, activating axis signaling and leading to circadian rhythm disruption. This results in simultaneously activating the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway to enhance the Warburg effect, thereby promoting tumor cell proliferation and the growth of hepatic metastatic lesions[73] [Figure 1].

Figure 1. The role of macrophages in inducing the pre-metastatic niche in the liver. Created in BioRender. Zhuang, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/m8wg8ed. GDNF: Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; GFRA1: GDNF family receptor alpha 1; EFNB2: ephrin-B2; EPHB2: ephrin type-B receptor 2; LBP: lipopolysaccharide-binding protein; PMN: polymorphonuclear neutrophils.

T-cell dysfunction and heterogeneity also play an important role in the immunosuppressive microenvironment of GC. Ma et al. integrated multi-omics data, including single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics (SRT), and discovered a stromal immunosuppressive barrier in GC. This barrier is composed of Macro_SPP1/C1QC macrophages (SPP1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; C1QC, complement C1q C chain) and CD8_Tex_C1 exhausted T cells, which are distributed in the stromal region, express PD-1, and partially retain cytotoxicity. Additionally, among CD8_Tex cells, there is a CD8_Tex_C2 subpopulation that distributes toward the tumor core, is in a terminally exhausted state, and expresses cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4). These two cell types mediate T cell dysfunction through macrophage-derived signaling axes such as MIF-CD74/CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4)/CD44, thereby forming an immune escape mechanism and leading to resistance to immunotherapy[74]. Using single-cell RNA sequencing, SRT, and other techniques, Wang et al. further discovered that the TME of Lauren intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma contains exhausted CD8+ T cells (e.g., HAVCR2+ VCAM1+ Texs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs, e.g., LAYN+ TNFRSF4+ Tregs). These cells promote tumor immune escape and progression by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines and intercellular interactions[75].

Tregs play a crucial role in promoting immune evasion in GC by suppressing anti-tumor immune responses. These specialized immune cells accumulate in the TME and exert their suppressive functions through various mechanisms, including the production of inhibitory cytokines such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and IL-10, direct cell-to-cell contact, and modulation of antigen-presenting cells[76,77]. By suppressing the proliferation and activity of effector T cells such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes, Tregs impair the immune system’s ability to eradicate malignant cells. Consequently, an increased abundance of Tregs within GC tissues and peripheral blood frequently correlates with more advanced disease stages and a poorer prognosis, highlighting their crucial role in fostering immune tolerance and driving tumor advancement[78].

Different subtypes of GC exhibit distinct T-cell heterogeneity. For example, GC with MSI-H shows significantly higher proportions of effector memory T cells (Tem), exhausted T cells (Tex), and proliferative exhausted T cells (pTex). Although Tex/pTex cells highly express the exhaustion marker LAG3, they still retain the interferon-gamma (IFN-γ, IFNG) signaling pathway and effector function markers such as IFNG and GZMB. Additionally, the IFN-γ signal crosstalk between these cells and malignant cells is significantly enhanced. In contrast, GC with MSS has higher proportions of mucosa-associated invariant T cells and NK T cells, while the effector functions of Tex/pTex cells are weak[79].

Notably, H. pylori infection is a significant factor that exacerbates the remodeling of the TME, profoundly influencing the interplay between inflammation and immunity to promote an immunosuppressive state conducive to GC progression[80-82]. The chronic inflammation induced by H. pylori leads to the recruitment and activation of various immune cells, many of which adopt immunosuppressive phenotypes. Specifically, the infection promotes the accumulation of Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the gastric mucosa, which actively suppress anti-tumor immune responses[83]. Furthermore, the bacteria induce the expression of immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-L1 on both gastric epithelial and immune cells, which further inhibits effector T cell activity and promotes immune evasion[84,85]. Ultimately, this sustained, H. pylori-driven immunosuppression creates a fertile ground for GC development by allowing transformed cells to escape immune surveillance and proliferate unchecked.

In conclusion, the GC immune microenvironment is a complex and dynamic network composed of various cells and pathways. Targeting immunosuppression-related cells and H. pylori is crucial for improving resistance to immunotherapy.

ECM and mechanical force regulation

Signal transduction generated by mechanical forces acting on the ECM is crucial for cellular functions[86]. Jeong et al. demonstrated that when cells are in a high-mechanical-force environment, such as growing on a stiffer ECM, the formation of F-actin in the cytoskeleton increases, enhancing the interaction between retinoic acid induced protein 14 (RAI14) and neurofibromatosis type 2 protein (NF2) on F-actin. It inhibits NF2 from activating the Hippo signaling pathway, keeping large tumor suppressor 1/2 (LATS1/2) inactive, dephosphorylating YAP/TAZ (transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif), and allowing their nuclear translocation to activate target gene expression, thereby promoting cell proliferation and cancer progression[87]. Additionally, increased ECM stiffness can awaken dormant tumor cells by upregulating Troponin T1 (TNNT1) protein expression, thus facilitating hepatic metastasis of GC[88].

The ECM of GC exhibits significant structural heterogeneity and biophysical property changes, characterized by abnormal deposition of collagen fibers, matrix stiffening, and complex spatial reorganization (such as the structural transformation of collagen I)[89,90]. This stiffening originates from the activation of CAFs, which promote ECM crosslinking and rigidification by secreting fibrogenic substances (e.g., collagen, fibronectin) and mediating enzymatic crosslinking reactions of the LOX family[91,92]. The stiffened ECM forms a physical barrier and directly activates mechanical force transduction pathways, driving tumor malignant progression[93]. Studies have demonstrated that collagen type V alpha 2 (COL5A2) can promote liver metastasis of GC, and its high expression is associated with poor prognosis in GC patients[94]. The ECM protein FRAS1 (Fraser syndrome protein) has also been implicated as a key driver of GC metastasis. Mechanistically, FRAS1 activates the EGFR and PI3K signaling pathways, which in turn modulates the expression of downstream target genes such as Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1) and microtubule-associated Protein 1B (MAP1B). This signaling cascade confers multiple pro-tumorigenic advantages to GC cells, including enhanced proliferation, invasion, and cancer stem cell properties. Concurrently, it promotes cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis and mitigating oxidative stress damage. These cellular alterations collectively facilitate the establishment of hepatic metastatic lesions. Underscoring its clinical importance, high FRAS1 expression is significantly associated with an increased rate of hepatic recurrence in GC patients, positioning it as a promising predictive biomarker and a potential therapeutic target[15].

Matrix stiffening is closely associated with therapeutic resistance in GC. High expression of calponin 1 (CNN1) in GC tissues interacts with PDZ and LIM domain 7 (PDLIM7) to prevent its degradation by the E3 ubiquitin ligase neural precursor cell expressed developmentally downregulated 4-1 (NEDD4-1). This interaction activates the Rho-associated kinase 1 (ROCK1)/myosin light chains (MLC) pathway and enhances CAF contractility, thereby increasing matrix stiffness. This increased matrix stiffness promotes 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) resistance in GC cells by activating YAP[95]. He et al. showed that after oxaliplatin (OXA) treatment, GC cells increase ECM accumulation, alter the mechanical properties of the TME, and activate the Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA)/Rho-associated coiled-coil containing kinase 1 (ROCK1) signaling pathway in MSCs, promoting mitochondrial transfer from MSCs to GC cells via microvesicles (MVs). The transferred mitochondria fuse with those in GC cells, reducing mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) levels and enhancing the resistance of GC cells to OXA-induced killing[96].

PMN of liver metastasis

The liver’s unique microenvironment creates a permissive “soil” for the hematogenous metastasis of GC, a process preceded by the formation of a PMN. Recent studies have indicated that the PMN formed by changes in the hepatic microenvironment lays the foundation for the progression of “seeding” in hepatic metastatic carcinoma. Tumor-derived exosomes enriched with circ-0034880 reach the liver via the bloodstream and are internalized by macrophages. The released circ-0034880 acts as a sponge for miR-200a-3p and miR-141-3p, protecting SPP1 from degradation, and activates SPP1high CD206+ pro-tumor macrophages to remodel the hepatic microenvironment, thereby promoting the formation of the PMN[97]. In addition, Hepatocytes can actively shape an immunosuppressive PMN when cell cycle-related kinase (CCRK) becomes aberrantly activated. This hyperactivation engages the NF-κB signaling cascade to drive C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) secretion. Consequently, this leads to the hepatic accumulation of polymorphonuclear MDSCs (PMN-MDSCs), which effectively neutralize local immune surveillance by inhibiting NK T cell activity and their production of IFN-γ[98]. The CCL2-CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) signaling axis has been identified as a key mediator of hepatic PMN formation driven by GC. According to Cui et al., this process begins when high Ephrin-A1 (EFNA1) expression in tumor cells activates YAP, leading to elevated CCL2 secretion. In the liver microenvironment, this CCL2 binds to CCR2 on HStCs, initiating a WNT (wingless-type MMTV integration site family)/β-catenin-dependent activation program. This program enhances the migratory and fibrotic properties of HStCs, as evidenced by increased Alpha-smooth muscle actin, Fibroblast (α-SMA) and Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) expression, ultimately conditioning the liver for metastasis. Crucially, pharmacologic inhibition of CCL2 was sufficient to reverse HStC activation and significantly reduce metastatic outgrowth[99]. The aforementioned studies suggest a positive potential of the PMN in predicting and treating hepatic metastasis of GC.

PRECISION THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES TARGETING THE MICROENVIRONMENT

Overcoming physical barriers

Drugs can be released explicitly in the acidic TME by designing nanoparticles to target tumor-associated fibroblasts, penetrate physical barriers, and reduce off-target toxicity[100,101]. Yuan et al. constructed a lipid-polymer hybrid drug delivery system (PI/JGC/L-A), transforming the tumor-associated fibroblast barrier into an anti-tumor drug reservoir. This strategy bypasses the CAF barrier and enables precise delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs and immunostimulatory factors[102]. Li et al. used tin sulfide nanoparticles (SnSNPs) as nano-sensitizers to enhance the efficacy of sonodynamic therapy and activate anti-tumor immune responses. SnSNPs can efficiently generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) under ultrasonic activation and produce mild photothermal effects under near-infrared (NIR) irradiation, denaturing tumor collagen and enhancing tumor permeability of nanoparticles[103]. The FPC@S constructed by Qiu et al., a photodynamic immunomodulatory nanosystem self-assembled from Fmoc-K(PpIX)-CREKA (FPC), a chimeric ECM-targeting peptide incorporating the photosensitizer protoporphyrin IX, and SIS3, an anti-fibrotic agent, can anchor to the ECM. It achieves ECM remodeling and tumor cell killing through the in situ generation of ROS. Meanwhile, FPC@S can release SIS3 in the acidic TME, reprogram CAFs to reduce their activity, thereby inhibiting fibrosis and preventing tumor metastasis[104]. The biomimetic nanosystem CM@GNRs-BO constructed by Liu et al., a tumor cell membrane-camouflaged gold nanorod (GNR)-based nanoplatform co-loaded with 2-bromopalmitic acid (2-BP) and OXA, achieves on-demand drug release via homologous targeting of tumor cell membranes combined with NIR photothermal therapy. It exerts photothermal/chemotherapeutic synergistic therapeutic effects to inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of GC[105].

Reprogramming the immune microenvironment

The development of a pro-tumoral stromal-myeloid niche is a primary driver of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) in GC. Research by Li et al. identified this niche as being established by Thrombospondin 2 (THBS2+) matrix CAFs (mCAFs), which utilize the complement C3-Complement Component 3a Receptor 1 (C3AR1) axis to recruit and polarize macrophages into an immunosuppressive SPP1+ phenotype. This finding presents a clear therapeutic vulnerability; blocking the C3-C3AR1 pathway effectively dismantles this stromal-myeloid crosstalk, leading to a significant enhancement of ICB efficacy[106]. Utilizing single-cell RNA sequencing to analyze GC tissues and adjacent mucosal samples, Li and colleagues uncovered the heterogeneity of CAFs within the GC TME. Four primary CAF subpopulations were identified: myofibroblasts, pericytes, inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), and ECM-associated CAFs (eCAFs). Among these subtypes, iCAFs and eCAFs were found to engage in active crosstalk with neighboring immune cell subsets: specifically, iCAFs mediate interactions with T cells through the secretion of IL-6 and CXCL12. In contrast, eCAFs exhibit a close association with M2-polarized macrophages and contribute to GC cell invasion by driving the expression of functional genes such as POSTN. Mechanistically, inhibiting the activation of these functionally distinct CAF subpopulations not only suppresses the “seed” potential of GC cells but also ameliorates the unfavorable “soil” properties of the TME, ultimately achieving an inhibitory effect on GC metastasis[107].

HER2-overexpressing GC often presents an immunologically “cold” microenvironment, characterized by high tumor purity, sparse immune cell infiltration, and low expression of checkpoint molecules (e.g., PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4)[107]. This profile suggests a basis for the limited efficacy of single-agent ICIs and provides a strong rationale for combining HER2-targeted therapies with these agents to reinvigorate the anti-tumor immune response. Clinically, HER2-positive status is also a biomarker for aggressive disease, as its prevalence is significantly higher in patients with hepatic metastases than in those without (31% vs. 11%)[108,109]. Yang et al. found that high PD-L1 expression [combined positive score (CPS) ≥ 1] correlates with a favorable infiltration of CD4+, CD8+, and NK cells, suggesting better responses to ICIs. In contrast, low PD-L1 expression (CPS < 1) is associated with a poor prognosis driven by an abundance of CXCR4+ M2-type macrophages. This suggests that anti-HER2 therapies may also function by regulating this M2 macrophage population[110]. A phase 2 clinical trial conducted by Bie et al. showed that Benmelstobart combined with anlotinib is a potential first-line option for HER2-negative advanced GC patients regardless of PD-L1 expression[111].

EBV-associated GC exhibits a more active immune microenvironment, with richer immune cell infiltration and immune-related gene expression, leading to a higher response rate to PD-1 immunotherapy[112]. In contrast, non-EBV GC features a more immunosuppressive immune microenvironment, particularly the overexpression of the Cyclooxygenase-2/Prostaglandin E2 (COX-2/PGE2) pathway, which may inhibit anti-tumor immune responses[113]. Studies have shown that IL-15Rα expression is downregulated due to promoter hypermethylation in EBV-positive GC, and this epigenetic regulatory mechanism is closely associated with immune cell infiltration in the TME[114]. Additionally, EBV promotes CD47 expression by activating the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) signaling pathway, enabling tumor cells to evade immune surveillance and inhibiting macrophage phagocytosis. Blocking CD47 therapy can enhance macrophage phagocytosis and anti-tumor immune responses[115].

With the advancement of bioinformatics, an increasing number of targets in the GC immune microenvironment have been identified and validated. Research by Chen et al. has elucidated a N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10)-driven metastatic pathway. Elevated NAT10 in tumor cells stabilizes CXCL2 mRNA via N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) modification. Secreted CXCL2 recruits and polarizes M2-like macrophages, which then produce oncostatin M (OSM). OSM-mediated activation of STAT3 transcriptionally upregulates NAT10, creating a positive feedback loop. This circuit enhances the pro-metastatic phenotype of macrophages and promotes the liver metastatic potential of GC cells[116]. High expression of phospholysine phosphohistidine inorganic pyrophosphate phosphatase (LHPP) in GC is linked to both direct tumor-suppressive effects and an improved anti-tumor immune profile. LHPP attenuates the stemness, chemoresistance, and invasive potential of cancer cells by modulating GSK-3β phosphorylation, while also correlating with greater infiltration of CD8+ T cells[117]. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) can activate COX-2 via Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), thereby promoting hepatic metastasis of GC[118]. Monocarboxylate transporter-4 (MCT4) not only promotes the proliferation and migration of GC cells but also affects immune cell infiltration and function in the TME by regulating lactic acid metabolism, particularly being associated with the infiltration and activation status of T cells, neutrophils, and macrophages. Knockdown of MCT4 significantly alters the immune microenvironment and enhances anti-tumor immune responses[119].

Biomarker development

Detection of relevant biomarkers serves as an important tool for evaluating patient prognosis and predicting treatment sensitivity. PD-L1 expression level is one of the commonly used biomarkers for predicting the efficacy of ICIs. However, multiple factors influence its expression, and inconsistent detection methods and standards limit its accuracy[120,121]. Studies have shown that tumors with high tumor mutational burden (TMB) may be more sensitive to immunotherapy. Nevertheless, TMB detection is costly, and the threshold for different tumor types has not been unified[122,123].

Gamma-glutamyltransferase light chain 2 (GGTLC2) has emerged as a potential biomarker for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatic metastasis in GC. Research from Yan et al. demonstrates that its high expression in tumors enhances cell proliferation, invasion, and migration by inhibiting ferroptosis and influencing the local immune and inflammatory response[124]. In fact, the emergence of public databases such as TCGA and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) has greatly facilitated the exploration of novel biomarkers for hepatic metastasis of GC. Genes such as Prolyl 4-hydroxylase subunit alpha 3 (P4HA3)[125], Cysteine desulfurase (NFS1)[126], Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1)[127], Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1)[128], A receptor type-1 (ACVR1)[129], CXCR4[130], Serine/Threonine Kinase 40 (Stk40)[131], and RNA-binding protein with multiple splicing 2 (RBPMS2)[132] have been reported to be closely associated with metastasis, prognosis, and immunotherapy sensitivity in GC patients. However, further animal and clinical trials are required for validation.

Exosomal RNAs represent a significant improvement over conventional GC markers, which lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity. Unlike traditional markers, these RNAs are released directly from cancer cells into the bloodstream via exosomes and provide a more accurate snapshot of tumor progression, making them highly promising for early diagnosis[133,134]. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play important roles in the progression and hepatic metastasis of GC. In GC tissues, lncRNA TENM3 antisense RNA 1 (TENM3-AS1), activated by the transcription factor Early growth response 1 (EGR1), interacts with Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNPK) and enhances its deubiquitination, thereby stabilizing Fatty acid synthase (FASN) mRNA to reprogram fatty acid metabolism and ultimately promoting hepatic metastasis of GC[135]. LncRNA GMAN binds to antisense GMAN RNA (GMAN-AS) and promotes the translation of adrenergic A1 mRNA into protein, thereby facilitating the proliferation and hepatic metastasis of GC[136].

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a class of non-coding RNA characterized by a covalently closed circular structure. Mounting evidence shows they perform critical biological functions, establishing them as promising new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for disease management[137,138]. Hsa_circ_0136666 exerts a dual effect to advance GC: it promotes tumor growth via the miR-375/Protein kinase, DNA-activated, catalytic subunit (PRKDC) axis while simultaneously facilitating immune escape through the phosphorylation of PD-L1[139]. Circular RNA Cullin 2 (circCUL2) may govern cisplatin sensitivity in GC via autophagy activation, a process mediated by the miR-142-3p/Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 2 (ROCK2) signaling axis[140]. Moreover, Circular RNA sperm antigen with calponin homology and coiled-coil domains 1, Autophagy related 4B cysteine peptidase (circSPECC1 binds to ATG4B), enhancing the anoikis of GC cells by promoting the ubiquitination and degradation of ATG4B. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug lopinavir can block the interaction between Embryonic Lethal, Abnormal Vision, Like 1 (ELAVL1) and circSPECC1, enhance circSPECC1 expression, reduce ATG4B levels, and thereby inhibit autophagy and invasion of GC cells[141,142]. This section summarizes the miRNAs [Table 2] and circRNAs [Table 3] with potential diagnostic value in GC-LM, along with their main functions.

Summary of miRNAs with potential diagnostic value in GC-LM

| Name | Type | Effect on gastric cancer | Major function | Ref. |

| miR-605-3p | miRNA | Inhibitory | Inhibits angiogenesis by reducing the release of exosomal NOS3 in gastric cancer, thereby preventing the formation of pre-metastatic niches in the liver | [143] |

| miR-145 | miRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses the malignant progression of gastric cancer by affecting proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis | [144] |

| miR-200a | miRNA | Inhibitory | Exhibits inhibitory effect on EMT-mediated GC metastasis | [145] |

| miR-488 | miRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses proliferation, migration, and invasiveness of gastric cancer cells and reduces tumorigenesis and liver metastasis in vivo | [146] |

| miR-193a-5p | miRNA | Inhibitory | Inhibits the migration ability of human KATO III gastric cancer cells by suppressing vimentin and MMP-9 | [147] |

| miR-143 | miRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses the growth and migration of the MKN-45 gastric cancer cell line | [148] |

| miR-4510 | miRNA | Inhibitory | Regulates the tumor microenvironment by targeting GPC3 to inhibit gastric cancer metastasis | [149] |

| miR-337-3p | miRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses gastric tumor metastasis by targeting ARHGAP10 | [150] |

| miR-33a | miRNA | Inhibitory | Inhibits gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis by blocking the Snail/Slug-mediated EMT | [151] |

| miR-7 | miRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses metastasis by inhibiting p65-mediated NF-κB activation, thereby reducing the expression of its downstream target genes responsible for cell adhesion, matrix degradation, and angiogenesis (e.g., VCAM-1, MMP-9, VEGF) | [152] |

| miR-647 | miRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses a pro-metastatic gene signature, notably downregulating the master EMT regulator SNAIL1 and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2, MMP12) essential for invasion | [153] |

| miR-27b | miRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses gastric cancer metastasis by targeting NR2F2 | [154] |

| miR-582 | miRNA | Promotive | Facilitates hepatic and pulmonary metastasis of gastric cancer cells through the FOXO3-mediated PI3K/AKT/Snail pathway | [155] |

| miR-196a-1 | miRNA | Promotive | Promotes the invasive capacity and metastatic potential of gastric cancer cells via targeting SFRP1 | [156] |

| miR-10b | miRNA | Promotive | Promotes invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer by inhibiting CSMD1 expression | [157] |

| miR-1915-3p | miRNA | Promotive | Promotes the occurrence and development of gastric cancer by inhibiting anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 | [158] |

Summary of circRNA with potential diagnostic value in GC-LM

| Name | Type | Effect on gastric cancer | Main function | Ref. |

| Hsa_circ_0006837 | circRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses gastric cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by regulating miR-424-5p | [159] |

| circZNF131 | circRNA | Inhibitory | Encodes a novel DNA-binding protein ZNF131-354aa, which suppresses gastric cancer growth by inhibiting CTBP2 transcription | [160] |

| circATM | circRNA | Inhibitory | Binds to PARP1 to suppress Wnt/β-catenin signaling and induce cell cycle arrest in gastric cancer cells | [161] |

| circRNA_0005927 | circRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses gastric cancer metastasis by downregulating the miR-570-3p/FOXO3 axis | [162] |

| circ_0008126 | circRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses the progression and metastasis of gastric cancer by regulating the APC/β-catenin pathway | [163] |

| circPFKP | circRNA | Inhibitory | Suppresses gastric cancer progression by targeting the miR-346/CAMD3 axis | [164] |

| circR-127aa | circRNA | Inhibitory | Acts as a tumor suppressor by promoting ubiquitination of Vimentin | [165] |

| circSCAF8 | circRNA | Inhibitory | Promotes tumor growth and metastasis of gastric cancer via miR-1293/TIMP1 signaling | [166] |

| Hsa_circ_0000479 | circRNA | Promotive | Promotes gastric cancer progression by inhibiting BTRC-mediated G3BP1 ubiquitination | [167] |

| CircRNA0007766 | circRNA | Promotive | Accelerates the progression of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (AEG) via the miR-34c-5p/cyclin D1 axis | [168] |

| circCOL6A3_030 | circRNA | Promotive | Promotes hepatic metastasis of gastric cancer cells by encoding a short peptide called circCOL6A3_030_198aa | [169] |

| circHECTD1 | circRNA | Promotive | Promotes glutaminolysis to facilitate gastric cancer progression by targeting miR-1256 and activating β-catenin/c-Myc signaling | [170] |

| circDLST | circRNA | Promotive | Promotes the tumorigenesis and metastasis of GC cells by sponging miR-502-5p to activate the NRAS/MEK1/ERK1/2 signaling | [171] |

| circTFRC | circRNA | Promotive | Directly binds to SCD1 mRNA, alleviates ferroptosis, and promotes oncogenic lipid metabolic reprogramming in gastric cancer cells | [172] |

| Hsa_circ_0001756 | circRNA | Promotive | Drives glycolysis in gastric cancer by increasing the expression and stability of PGK1 mRNA | [173] |

| circMAN1A2 | circRNA | Promotive | Promotes cancer progression and suppresses T cell anti-tumor immunity by inhibiting FBXW11-mediated SFPQ degradation | [174] |

| Hsa_Circ_0007376 | circRNA | Promotive | Promotes gastric cancer progression by regulating the miR-556-5p/CREB5 axis | [175] |

| circ_0006988 | circRNA | Promotive | Promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of gastric cancer cells via the miRNA-92a-2-5p/TFAP4 axis | [176] |

| Hsa_Circ_0008035 | circRNA | Promotive | Drives immune escape of gastric cancer by promoting EXT1-mediated nuclear translocation of PKM2 | [177] |

Additionally, clinical assessment models based on biomarkers hold great potential. Mak et al. developed a CAF-based biomarker model, CAFS-score, which classifies GC patients into subtypes with distinct prognoses by analyzing CAF-related gene expression and correlates with patient prognosis, immune infiltration, and treatment sensitivity[178]. A pyroptosis-related risk score (PRS), constructed from key gene expression, has emerged as a reliable biomarker for predicting outcomes in GC. This score’s effectiveness is rooted in the influence of pyroptosis on the TME, where it regulates immune cell infiltration and function. Specifically, a low PRS indicates heightened pyroptotic activity, which fosters an anti-tumor response by increasing the presence of beneficial immune cells. Consequently, patients with a low PRS tend to have a better prognosis and a more favorable response to immunotherapy[179]. Song et al. identified a subpopulation of antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs) with high major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) expression in GC. The infiltration level of apCAFs in tumor tissues of GC patients is closely associated with favorable prognosis, and the baseline infiltration level of apCAFs is significantly higher in immunotherapy responders across multiple cancer types, indicating that apCAFs hold promise as biomarkers for predicting immunotherapy response[180]. Liu et al. developed a PANoptosis-related risk score (PANS) based on the characteristics of PANoptosis (an inflammatory form of programmed cell death) in GC to predict patient prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy. By classifying GC patients into PAN subtypes, the study found that the PANcluster A/low PANS group had superior clinical outcomes. Their tumors were immunologically “hot”, featuring abundant anti-tumor lymphocytes, high TMB, and MSI-high status. This immunogenic profile, combined with low tumor purity, correlated strongly with a positive response to immunotherapy[181].

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CHALLENGES

Multi-omics integration and spatial dynamic profiling

Integrating SRT, spatial proteomics, and spatial metabolomics technologies to systematically dissect the TME heterogeneity between GC-LM and primary tumors[182] - especially the cell interaction networks in tumor marginal regions (e.g., the positional relationships among tumor cells, stromal cells, and immune cells) - helps identify key molecular events promoting metastasis[183,184].

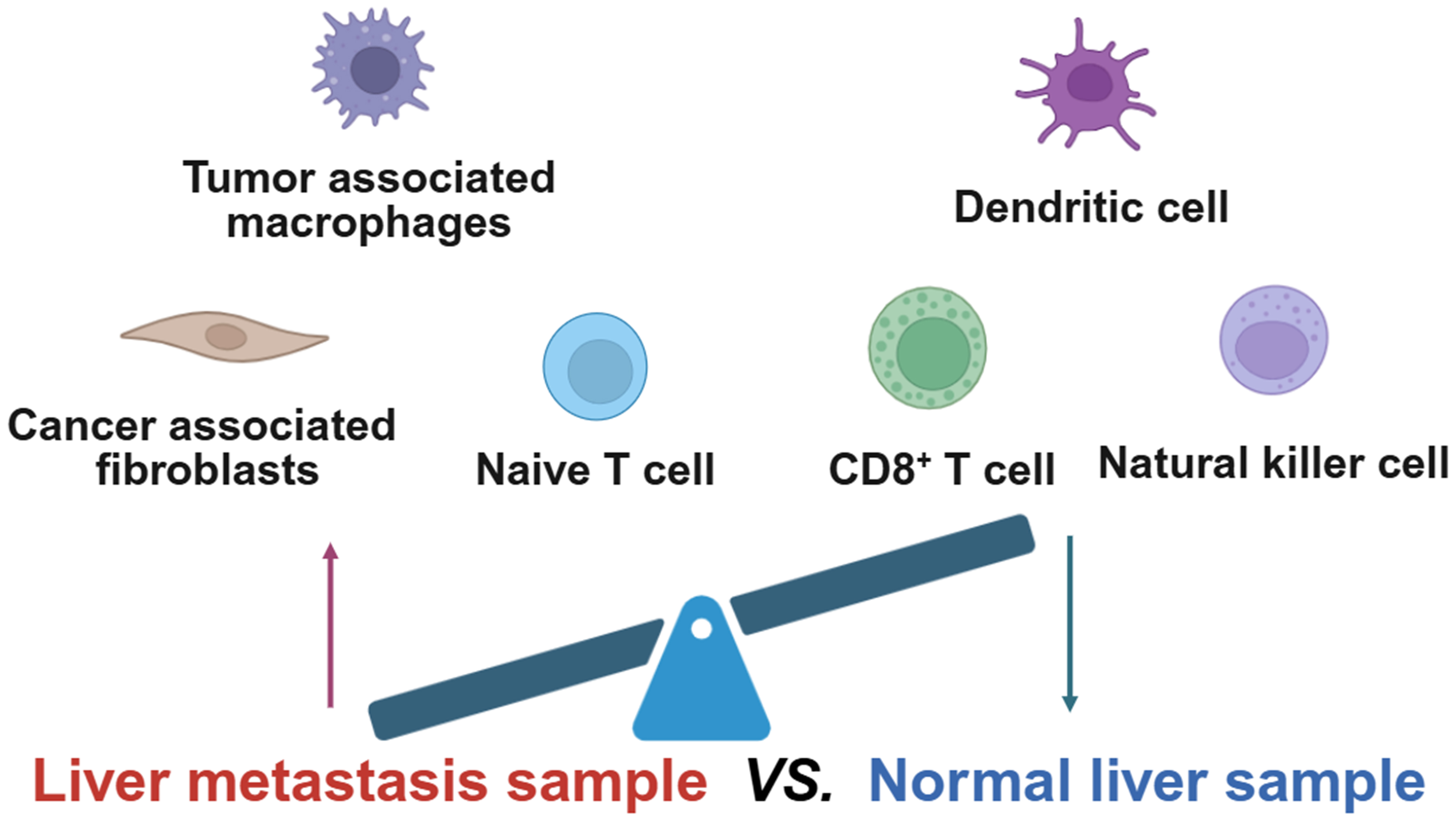

As shown in Figure 2, by employing single-cell RNA sequencing, Tang et al. demonstrated that GC liver metastases exhibit an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Compared to healthy tissue, these metastases were enriched with CAFs, TAMs, and naive T cells, while crucial anti-tumor responders such as conventional DCs and effector CD8+ T cells were diminished. Notably, NK cells were also significantly reduced, a dysfunction linked to the presence of TGF-β. The findings suggest that TGF-β-mediated suppression of NK cells is a key mechanism facilitating immune evasion and metastatic progression[185].

Figure 2. Cellular differences between liver metastatic cancer samples and normal liver samples. Created in BioRender. Zhuang, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/276chgt.

In predictive modeling, Ding et al. developed the ANLiM score - a blood biomarker-based model incorporating AFP (alpha fetoprotein) and NLR (neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio) in liver metastasis of AFP-producing GC (AFPGC) - to guide immunotherapy decisions for patients with AFPGC liver metastasis. The biomarkers for the model were identified through comprehensive multi-omic analyses that revealed the distinct biological features of these tumors. Specifically, the liver metastasis group exhibited a highly immunosuppressive microenvironment [e.g., increased Neutrophil 2-tumor-associated neutrophils (N2-TANs), reduced tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS), suppressed STING/Interferon gamma (IFNG) signaling] and significant genomic instability. Clinically validating the model, the study found that high ANLiM scores were strongly associated with poor responses to immunotherapy. These results indicate that this score could serve as a valuable biomarker for patient stratification and therapeutic optimization[188].

Molecular pathology-clinical translation closed loop

Although liver metastasis is the primary cause of death in GC patients, the key molecular mechanisms driving metastasis remain incompletely elucidated. The hepatic PMN promotes communication between primary tumors and the liver[189]. However, the molecular details of its formation have not been systematically clarified, leading to barriers in molecular pathology-clinical translation. Although numerous genes mediating GC-LM have been mined from public disease databases, the functional networks of these genes remain unclear, and these mechanistic blind spots hinder the development of effective strategies for preventing and treating liver metastasis[17].

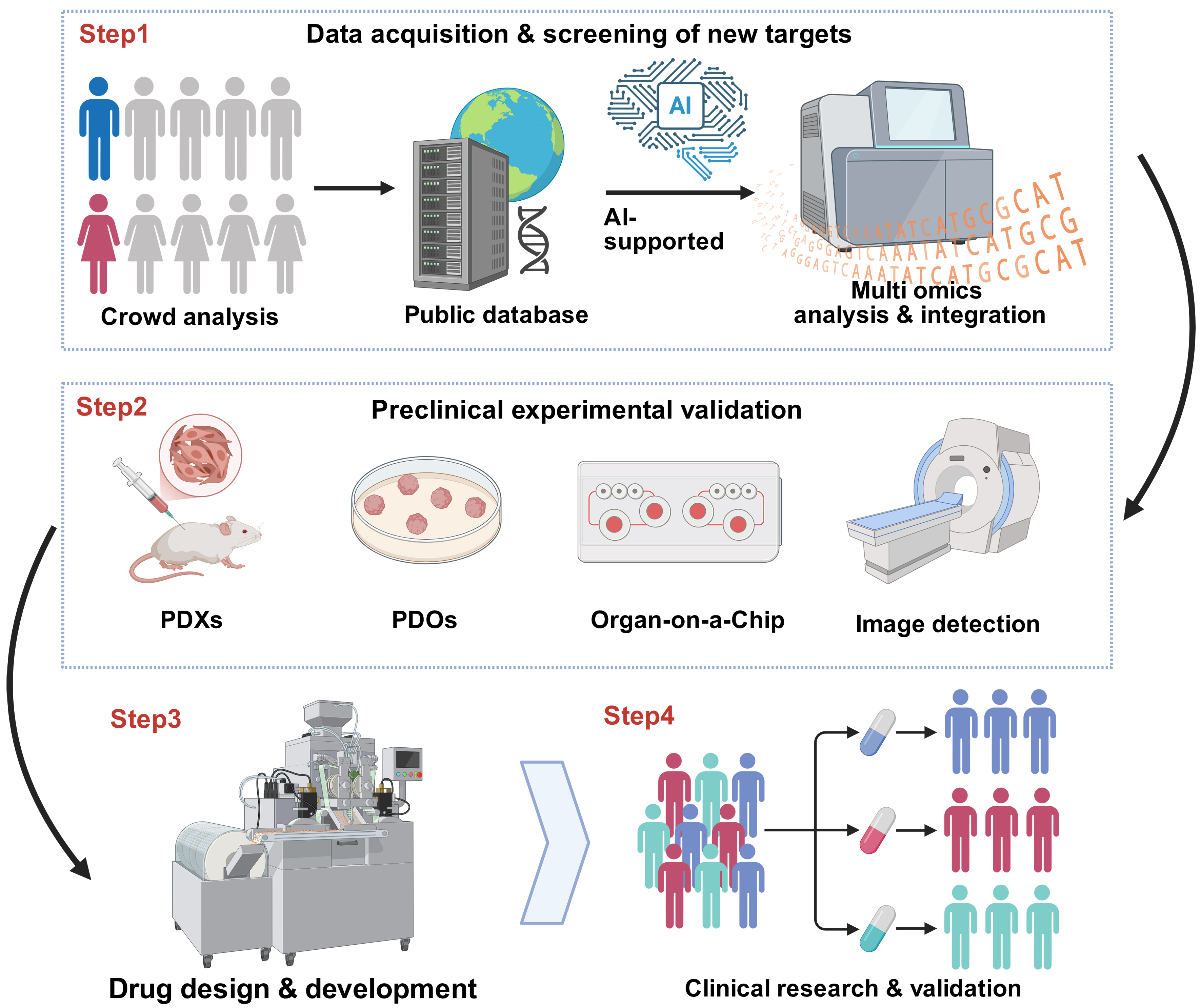

As shown in Figure 3, utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to achieve high-throughput screening of target genes, combined with validation using in vitro models such as patient-derived tumor xenografts (PDX), organoids, and organ-on-a-chip systems, can effectively improve screening efficiency and validation effectiveness, thereby enhancing the success rate of clinical translation[190]. Jiang et al. developed an AI tool named GC-SVM classifier using a support vector machine (SVM), which predicts overall survival and disease-free survival by analyzing clinicopathological features of GC patients and 15 immunohistochemical markers including CD3, CD8, CD45RO, CD45RA, and CD57. This classifier can effectively distinguish patient groups with different prognoses, demonstrating higher prediction accuracy than the traditional tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system. It can identify GC patients who may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy[191]. Zeng et al. constructed a machine learning-based tool, TMEclassifier, which classifies the TME of cancer patients into three subtypes: immune-excluded (IE), immune-suppressed (IS), and IA. The study found that patients with the IA subtype responded better to immunotherapy, while IE and IS subtypes exhibited poor prognosis and immunotherapy resistance. The upregulation of the IL-1/IL-1R1 signaling pathway in the IS subtype may be associated with TME immunosuppression and immunotherapy resistance. In vivo, experiments validated that treatment targeting IL-1/IL-1R1 can reverse the immunosuppressive state of IS subtype tumors and significantly enhance their sensitivity to PD-1 blockade[192].

Figure 3. The main steps of molecular pathology-clinical translation closed-loop research. Created in BioRender. Zhuang, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/rhqn56d. PDXS: Patient-derived xenografts; PDOs: patient-derived organoids; AI: artificial intelligence.

Meanwhile, developing novel imaging technologies to achieve real-time, dynamic monitoring of the TME will provide more accurate and timely information for clinical treatment decisions. Lee et al. trained an AI model using conventional white-light endoscopy images and videos to predict early GC pathological outcomes comprehensively. The model achieved accuracies of 89.7%, 88.0%, 87.9%, and 92.7% in predicting undifferentiated histology, submucosal invasion, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), and lymph node metastasis (LNM), respectively, outperforming expert predictions[193]. This study demonstrates that AI has the potential to assist physicians in predicting the differentiation status and invasion depth of early GC based on routine endoscopic images and videos, thereby guiding optimal treatment selection for patients. Ling et al. constructed an AI model by extracting high-dimensional features from computerized tomography (CT) images (such as gray-level matrices and shape characteristics) and integrating clinical indicators [such as tumor stage, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), etc.], using ensemble learning strategies such as the Stacking Classifier. The model showed excellent performance in the validation set and has been developed into an online risk prediction tool to inform individualized treatment decisions for GC patients[194]. In addition, deep learning-based semi-automatic segmentation software has improved the recognition efficiency for the reproducibility of radiomic features in hepatic metastasis[195]. To improve clinical decision-making for GC with liver metastasis, Wang et al. established and validated a predictive nomogram. The nomogram was built upon ten readily available clinical variables, including patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and treatment history. The authors reported that the tool exhibited high C-index and was well-calibrated, confirming its reliability for stratifying patient risk and informing therapeutic planning[196]. These studies further highlight the potential of AI technologies in integrating multimodal medical data to enhance tumor diagnosis and prognostic capabilities[197].

CONCLUSION

Liver metastasis of GC presents a formidable challenge in clinical practice, characterized by a dismal prognosis. An in-depth understanding of the TME is pivotal for overcoming this challenge. This review summarizes recent advances in research on the TME of GC-LM. Clinically, the high incidence and low survival rate of GC-LM highlight its severity. The lack of obvious early symptoms and specific biomarkers leads to most patients being diagnosed at advanced stages, missing the optimal treatment window. Although current treatment methods are diverse, their efficacy remains unsatisfactory, urgently calling for novel therapeutic strategies[198].

Molecular pathological studies have shown that molecular typing of GC provides a basis for precision therapy, with distinct clinicopathological features and prognoses among different molecular subtypes. Dynamic remodeling of the TME plays a critical role in GC-LM through several mechanisms. Reprogramming of stromal cells alters their phenotype and function to support tumor progression. Concurrently, the infiltration of suppressive immune cells and the secretion of inhibitory cytokines establish an immunosuppressive landscape that facilitates tumor immune escape. Furthermore, alterations in the ECM and its associated mechanical forces directly enhance tumor cell adhesion, migration, and invasion while also regulating intracellular signaling. These multifaceted changes highlight the TME as a critical therapeutic target and ECM-encapsulated organoid drug screening[199]. Consequently, precision therapies aimed at modulating the immune microenvironment to enhance immunotherapy or inhibiting stromal and ECM-related molecules offer new hope for overcoming treatment resistance and preventing metastatic progression. Meanwhile, developing biomarkers is crucial for precision therapy, aiding in screening patients suitable for specific treatment regimens to improve therapeutic efficacy and safety[200].

Future research directions should focus on multi-omics integration and spatial dynamic profiling, comprehensively utilizing multi-omics technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to dissect the complexity and dynamic changes of the TME in GC-LM and to identify key molecular regulatory networks and potential therapeutic targets[201]. Additionally, constructing good GC mouse models and a closed loop of molecular pathology-clinical translation is essential[202], strengthening the integration of basic research and clinical application to rapidly translate molecular pathological findings into clinical practice, providing more precise diagnostic and treatment strategies for patients, and ultimately improving the prognosis, quality of life, and survival rate of patients with GC-LM.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The Graphical Abstract was created in BioRender. Zhuang, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/6i3akno.

Authors’ contributions

Drafted the initial manuscript: Zhuang J

Supported the manuscript preparation and analysis: Hu C

Designed the tables and provided comments: Lei L, Sang Y

Conducted the final revisions: Xia H, Sun Q

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2023ZD0501500; No. 2025ZD0551500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Anhui Province Key Laboratory of Non-coding RNA Basic and Clinical Transformation (Wuhu, China), the China Hepatitis Prevention and Treatment Foundation Wang Baoen Liver Fibrosis Research Fund (No. 2025055), the Beijing Xisike Clinical Oncology Research Foundation, and the Start-up Fund of Southeast University.

Conflicts of interest

Xia H is an Associate Chief Editor of the journal Hepatoma Research. Xia H was not involved in any part of the editorial process for this manuscript, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Wang Z, Dong Z, Zhao G, Ni B, Zhang ZZ. Prognostic role of myeloid-derived tumor-associated macrophages at the tumor invasive margin in gastric cancer with liver metastasis (GCLM): a single-center retrospective study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13:1340-50.

2. Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:28.

3. He X, Guan XY, Li Y. Clinical significance of the tumor microenvironment on immune tolerance in gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1532605.

4. Jandu D, Latar N, Bajrami A, et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of papillary cancer mesenchymal stem/stromal cells reveals a transcriptional profile that supports a role for these cells in cancer progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:4957.

5. Xia Y, Jia J, Ma H, et al. Impact of PSMD2 on gastric cancer tissue stiffness investigated via motor-piezoceramic coupled atomic force microscopy. Nano Lett. 2025;25:3931-8.

6. Yu K, Cao Y, Zhang Z, et al. Blockade of CLEVER-1 restrains immune evasion and enhances anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in gastric cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13:e011080.

7. Lopes C, Pereira C. Advances towards gastric cancer screening: novel devices and biomarkers. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2025;75:102009.

8. Huang F, Fang M. Prediction model of liver metastasis risk in patients with gastric cancer: a population-based study. Medicine. 2023;102:e34702.

9. Wang C, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Li B. A bibliometric analysis of gastric cancer liver metastases: advances in mechanisms of occurrence and treatment options. Int J Surg. 2024;110:2288-99.

10. Luo Z, Rong Z, Huang C. Surgery strategies for gastric cancer with liver metastasis. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1353.

11. Li SC, Lee CH, Hung CL, Wu JC, Chen JH. Surgical resection of metachronous hepatic metastases from gastric cancer improves long-term survival: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182255.

12. Li HQ, Wang Q, Zhang LY, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy and trastuzumab in gastric cancer with liver metastases: a case report. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1283274.

13. Zhou J, Gou YK, Guo D, Wang MY, Liu P. Roles of gastric cancer-derived exosomes in the occurrence of metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2025;196:1-7.

14. Shi W, Wang J, Zhang W, Shou T. Long-term survival with stable disease after multidisciplinary treatment for synchronous liver metastases from gastric cancer: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;65:317-21.

15. Umeda S, Kanda M, Miwa T, et al. Fraser extracellular matrix complex subunit 1 promotes liver metastasis of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:2865-76.

16. Sakaue M, Sugimura K, Masuzawa T, et al. Long-term survival of HER2 positive gastric cancer patient with multiple liver metastases who obtained pathological complete response after systemic chemotherapy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107097.

17. Wang Y, Ding G, Chu C, Cheng XD, Qin JJ. Genomic biology and therapeutic strategies of liver metastasis from gastric cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024;202:104470.

18. Li D, Gao Z, Zhang Z, et al. Suprabasin promotes gastric cancer liver metastasis via hepatic stellate cells-mediated EGF/CCL2/JAK2 intercellular signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2025;44:1975-89.

19. Kim B, Shin HC, Heo YJ, et al. CCNE1 amplification is associated with liver metastasis in gastric carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215:152434.

20. Takayama-Isagawa Y, Kanetaka K, Kobayashi S, Yoneda A, Ito S, Eguchi S. High serum alpha-fetoprotein and positive immunohistochemistry of alpha-fetoprotein are related to poor prognosis of gastric cancer with liver metastasis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:3695.

21. She Y, Liu X, Liu H, et al. Combination of clinical and spectral-CT iodine concentration for predicting liver metastasis in gastric cancer: a preliminary study. Abdom Radiol. 2024;49:3438-49.

22. Yang J, Liu Z, Zeng B, Hu G, Gan R. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric cancer: a distinct subtype. Cancer Lett. 2020;495:191-9.

23. Furukawa K, Hatakeyama K, Terashima M, et al. Molecular features and prognostic factors of locally advanced microsatellite instability-high gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2024;27:760-71.

25. Nemtsova MV, Kuznetsova EB, Bure IV. Chromosomal instability in gastric cancer: role in tumor development, progression, and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:16961.

26. Zhang R, Liu Z, Chang X, et al. Clinical significance of chromosomal integrity in gastric cancers. Int J Biol Markers. 2022;37:296-305.

27. Díaz Del Arco C, Ortega Medina L, Estrada Muñoz L, García Gómez de Las Heras S, Fernández Aceñero MJ. Is there still a place for conventional histopathology in the age of molecular medicine? Laurén classification, inflammatory infiltration and other current topics in gastric cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Histol Histopathol. 2021;36:587-613.

28. Yu C, Wang J. Quantification of the landscape for revealing the underlying mechanism of intestinal-type gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:853768.

29. Gregory SN, Davis JL. CDH1 and hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: a narrative review. Chin Clin Oncol. 2023;12:25.

30. Ryan CE, Fasaye GA, Gallanis AF, et al. Germline CDH1 variants and lifetime cancer risk. JAMA. 2024;332:722-9.

31. Gamble LA, Heller T, Davis JL. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome and the role of CDH1: a review. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:387-92.

32. Shahi A, Kidane D. Aberrant DNA polymerase beta expression is associated with dysregulated tumor immune microenvironment and its prognostic value in gastric cancer. Clin Exp Med. 2024;24:239.

33. Sadeghi M, Karimi MR, Karimi AH, Ghorbanpour Farshbaf N, Barzegar A, Schmitz U. Network-based and machine-learning approaches identify diagnostic and prognostic models for EMT-type gastric tumors. Genes. 2023;14:750.

34. Liu P, Ding P, Guo H, et al. Clinical calculator based on CT and clinicopathologic characteristics predicts short-term prognosis following resection of microsatellite-stabilized diffuse gastric cancer. Abdom Radiol. 2024;49:2165-76.

35. Pretzsch E, Bösch F, Todorova R, et al. Molecular subtyping of gastric cancer according to ACRG using immunohistochemistry - correlation with clinical parameters. Pathol Res Pract. 2022;231:153797.

36. Wang Q, Xie Q, Liu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic significance of TCGA and ACRG classification in gastric cancer among the Chinese population. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22:828-40.

37. Zeng D, Wu J, Luo H, et al. Tumor microenvironment evaluation promotes precise checkpoint immunotherapy of advanced gastric cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e002467.

38. Zeng W, Zhu J, Zeng D, et al. Epigenetic modification-associated molecular classification of gastric cancer. Lab Invest. 2023;103:100170.

39. Wang JB, Qiu QZ, Zheng QL, et al. Tumor immunophenotyping-derived signature identifies prognosis and neoadjuvant immunotherapeutic responsiveness in gastric cancer. Adv Sci. 2023;10:e2207417.

40. Migita T, Sato E, Saito K, et al. Differing expression of MMPs-1 and -9 and urokinase receptor between diffuse- and intestinal-type gastric carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:74-9.

41. Ding Y, Zhang H, Lu A, et al. Effect of urokinase-type plasminogen activator system in gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:4208-16.

42. Ding Y, Zhang H, Zhong M, et al. Clinical significance of the uPA system in gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Eur J Med Res. 2013;18:28.

43. Huang HW, Chang CC, Wang CS, Lin KH. Association between inflammation and function of cell adhesion molecules influence on gastrointestinal cancer development. Cells. 2021;10:67.

44. Sun F, Feng M, Guan W. Mechanisms of peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:6991-8.

45. Dang HZ, Yu Y, Jiao SC. Prognosis of HER2 over-expressing gastric cancer patients with liver metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2402-7.

46. Petrillo A, Ottaviano M, Pompella L, et al. Rare epithelial gastric cancers: a review of the current treatment knowledge. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2025;17:17588359241255628.

47. Arai T, Komatsu A, Kanazawa N, Nonaka K, Ishiwata T. Clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of gastric papillary adenocarcinoma. Pathol Int. 2023;73:358-66.

48. Li M, Mei YX, Wen JH, et al. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma-clinicopathological features and molecular characteristics. Cancer Lett. 2023;559:216104.

49. Huang KH, Chen MH, Fang WL, et al. The clinicopathological characteristics and genetic alterations of signet-ring cell carcinoma in gastric cancer. Cancers. 2020;12:2318.

50. Guo P, Yang Y, Wang L, et al. Development of a streamlined NGS-based TCGA classification scheme for gastric cancer and its implications for personalized therapy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024;15:2053-66.

51. Zhang X, Ren B, Liu B, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics reveal the heterogeneity and intercellular communication of cancer-associated fibroblasts in gastric cancer. J Transl Med. 2025;23:344.

52. Sun H, Wang X, Wang X, Xu M, Sheng W. The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumorigenesis of gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:874.

53. Zhao Z, Zhang Y, Guo E, Zhang Y, Wang Y. Periostin secreted from podoplanin-positive cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes metastasis of gastric cancer by regulating cancer stem cells via AKT and YAP signaling pathway. Mol Carcinog. 2023;62:685-99.

54. Yang C, Gao Z, Tang R, et al. POU6F2 promotes liver metastasis of gastric adenocarcinoma by dual mechanism of transcriptional upregulation of SNAI1 and IGF2/PI3K/AKT signaling-induced conversion of hepatic stellate cells into cancer-associated fibroblasts. Br J Cancer. 2025;133:14-26.

55. Li Q, Zhu CC, Ni B, et al. Lysyl oxidase promotes liver metastasis of gastric cancer via facilitating the reciprocal interactions between tumor cells and cancer associated fibroblasts. EBioMedicine. 2019;49:157-71.

56. Zhang D, Sun R, Di C, et al. Microdissection of cancer-associated fibroblast infiltration subtypes unveils the secreted SERPINE2 contributing to immunosuppressive microenvironment and immuotherapeutic resistance in gastric cancer: a large-scale study integrating bulk and single-cell transcriptome profiling. Comput Biol Med. 2023;166:107406.

57. Sun K, Xu R, Ma F, et al. scRNA-seq of gastric tumor shows complex intercellular interaction with an alternative T cell exhaustion trajectory. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4943.

58. Xiang Z, Hua M, Hao Z, et al. The roles of mesenchymal stem cells in gastrointestinal cancers. Front Immunol. 2022;13:844001.

59. Ji R, Wu C, Yao J, et al. IGF2BP2-meidated m6A modification of CSF2 reprograms MSC to promote gastric cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14:693.

60. Chen Z, Xu P, Wang X, et al. MSC-NPRA loop drives fatty acid oxidation to promote stemness and chemoresistance of gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2023;565:216235.

61. Wang L, Wu C, Xu J, et al. GC‑MSC‑derived circ_0024107 promotes gastric cancer cell lymphatic metastasis via fatty acid oxidation metabolic reprogramming mediated by the miR‑5572/6855‑5p/CPT1A axis. Oncol Rep. 2023;50:138.

62. Zhang Y, Yang K, Bai J, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals the multidimensional dynamic heterogeneity from primary to metastatic gastric cancer. iScience. 2025;28:111843.